CHAPTER 12

MAKING BRAIN-LINKS

How Not to Learn from a Comic Book

When I was a kid, I was a little sneaky.

My parents wanted me to play the piano, and I wasn’t that excited about it. But I did as they asked. Kind of.

Every week, my teacher gave me a new song to practice. I would also practice older songs that I’d already learned. It was a lot easier and more fun to practice the older songs!

My parents could hear the piano going in the background, but they never paid attention to what I was playing.

I’d spend five minutes practicing the new song. Then I would put a comic book on the music stand in front of me. I would play the older song over and over again for twenty-five minutes while I read the comic book. Altogether, this made a half hour of practice.

Was I improving my ability to play the piano? Or was I just kidding myself? And what did my parents do when they realized what I had done?

Becoming an Expert

Let’s step back and remind ourselves about brain-links.

A set of brain-links is a well-practiced thought-trail. (Remember, we can also think of them as wide, smooth mouse pathways in the forest.) Your attentional octopus can easily reach out and link to the right brain-links whenever it needs a little help with its thinking—that is, if you have taken the time to build them. Having lots of brain-links relating to a topic is key to becoming an expert.*1

See the puzzle on the top of the next page? Every time you create a solid set of brain-links, it’s like connecting some pieces of a puzzle. When you’ve created enough links, the puzzle starts filling in. You begin to see the big picture of the subject. Even if there are a few small link-pieces you haven’t filled in, you can still see what’s going on. You have become an expert!

But what if you don’t practice with your newly developing brain-links? You can see what happens then by looking at the faded puzzle at the bottom of the page. It’s like trying to put together a washed-out puzzle. It’s not easy.

Each time you create a set of brain-links, you are fitting together pieces of a puzzle. The more you work with your links, the more you see how they fit in with other links. This creates bigger sets of links.

When you’ve built and practiced with enough links, you see the big picture! You’ve become an expert.

If you don’t practice with your links, they start to fade. This makes it harder to see the pieces, which makes the puzzle harder to put together.

Two Key Ideas Behind Linking

This brings us to a critical question. How do you go about making a set of brain-links? Two key ideas will help get you started—one involves practice and the other, flexibility.

1. Deliberate Practice (Versus Lazy Learning)

When you practice enough, you can build solid brain-links. But the way you practice is important. When you’ve got an idea well linked, it’s easy to practice, and it feels good. But this can turn into “lazy learning.” Lazy learning doesn’t encourage new daytime “bumps” on your dendrites that can turn into solid new neural connections while you sleep. When you can read comic books while you’re practicing, it’s time to move on.

The best way to speed your learning is to avoid lazy learning. If you spend too much time on material you already know, you won’t have time to learn new material.

This idea of focusing on the harder stuff is called deliberate practice.2 Deliberate practice is how you become an expert more quickly in whatever you are studying.3

2. Interleaving (or How to Teach Interstellar Friends)

Developing flexibility in your learning is also important. Here’s a story to demonstrate this: Let’s say that you make a new friend, named “Leaf,” from an exotic planet where they use advanced technologies. Your new friend has never used hammers or screwdrivers before.

You want to teach Leaf how to use a hammer and a screwdriver. Because you know about cognitive load,* you’re careful not to teach Leaf too much at once.

You start by showing Leaf how to use a hammer. He learns to pound in lots of nails. After a couple of hours of practice (Leaf is a clumsy interstellar friend), he’s got the idea of how to nail, well, nailed.

Next, you give Leaf a screw. To your surprise, Leaf starts trying to hammer the screw into a board.

Why? Because when the only thing Leaf has used is a hammer, everything looks like a nail. Leaf is applying the wrong technique to solve the problem, because he hasn’t studied and practiced when he should use one of the two different techniques.

It’s important not just to practice a given technique or item. It’s also important to practice choosing between techniques or items. This is true when you’re learning all sorts of topics.

Practicing different aspects and techniques of the skill you are trying to learn is called interleaving.4 (Just remember your interstellar friend, Leaf. Interleave—get it?)

Here are some visuals to help you better understand the idea of interleaving. When you study a typical topic you are learning in class, say “Topic 7,” you are often assigned a batch of homework problems related to Topic 7.* Here’s an example (the problem numbers refer to problems that your teacher assigns from a textbook):

Plain Assignment

Topic 7 problem 4

Topic 7 problem 9

Topic 7 problem 15

Topic 7 problem 17

Topic 7 problem 22

But when you interleave, you start mixing in other types of problems, so you can see the difference. Notice below how the shaded boxes cover different topics that are mixed into the Topic 7 problems. In that way, you can become comfortable not only with Topic 7, but also with the differences between Topic 7 and Topics 4, 5, and 6.

Interleaved Assignment

Topic 7 problem 4

Topic 4 problem 8

Topic 7 problem 9

Topic 6 problem 26

Topic 7 problem 15

Topic 5 problem 18

Topic 7 problem 17

When you interleave with different topics, you can almost feel your brain go, Wait a minute, what’s this? I didn’t expect to go back to that other stuff! But then you’ll notice how you begin to see differences between the topics in ways you hadn’t previously imagined.

Making a Set of Brain-Links

Now we can finally explain some of the best ways to make sets of brain-links in different subjects.

Focus

The most important step is the first one: focus. Memory champion Nelson Dellis told us that focusing is important for memorizing. But focus is also important more generally, for any information you want to link. You’ve got to use all the arms of your attentional octopus. No TV. No phone. You’re going to be forming some new brain-links, so you need to concentrate. Maybe grab your Pomodoro timer. Tell yourself: This is important— I need to focus!

(Psst! Can you make new brain-links if you’re not paying close attention? Maybe. If it’s super-easy material. But it’ll take you a lot longer to make the links.)

Do It—Active Practice!

If the brain-links you’re creating involve a physical action, then focus and do it. For example, if you’re learning how to score a basket in basketball, you need to practice making a basket. And then you need to do it again, perhaps from a different angle. Again. And again. And again. You’ll be getting constant feedback, because if you’re doing it wrong, you won’t make a basket. Likewise, if you’re learning a language, you’ll need to listen and say the words over and over, and if possible, get feedback from a native speaker. If you’re learning to play a musical instrument, you’ll need to practice new tunes. Or if you’re learning to draw, you’ll need to try different techniques. Get feedback from teachers wherever you can to correct yourself.

The key is to actively practice or bring to life whatever you are learning yourself. Just watching other people, or looking at a solution, or reading a page, can allow you to get started. But it won’t do much to build your own neural structures of learning. Remember Julius Yego with the javelin. He wasn’t just passively watching YouTube. He was focusing on the techniques and then actively practicing them.5

Practice your new skill over a number of days, making sure you get some good sleep each night. This helps your new synaptic brain-links to form. You want to broaden the forest pathways—thicken the links—for your mental mouse.

You also need to “change up” what you are doing. In soccer, you need to learn to dribble the ball, cross, pass, or shoot it. And you need to be able to tackle and chip the ball, too. It’s not just about kicking the ball any old way! All these skills are separate, but related. To become a soccer expert, each skill needs to be practiced separately during training, then interleaved. You want your reactions to become automatic during the heat of a match.

Whether you are learning martial arts, dance, an additional language, knitting, welding, origami, gymnastics, or the guitar, it’s all the same. Deliberate practice with interleaving. Focus on the hard stuff and mix it up. That’s how you become an expert.

Special Advice for Math, Science, and Other Abstract Subjects

Let’s say you’re trying to make a set of brain-links in math or science. See if you can work a problem by yourself. Show your work and write your answer out with a pencil. Don’t just look at the solution and say, “Sure, I knew that . . .”

Did you have to peek at the solution to get a little help? If so, that’s okay, but you’ll need to focus on what you missed or didn’t understand.

Next, see if you can work the problem again, without looking at the solution. And again. Do this over several days.

Try not to peek at the solution!

At first, the problem may seem so difficult that you could never work it! But it will eventually seem so easy that you will wonder how you could have thought it was hard. Eventually, you won’t even have to write the solution out with a pencil. When you just look at the problem and think about it, the solution will flow swiftly through your mind, like a song. You’ve created a good set of brain-links.6

Notice something important here. You’ve used active recall to help you create your brain-links. As we mentioned earlier, active recall is one of the most powerful techniques there is to boost your learning.

A key idea here is that you are not blindly memorizing solutions. You are looking at problems and learning how to build your own brain-links. Once that solid, beautiful set of links is formed, it can easily be pulled up into working memory when you need to. With enough practice independently solving the problem (not looking at the solution!), each step in the solution will whisper the next step to you.*

A big reason for my bad math grades when I was a teenager was that I looked at the answers in the back of the book. I fooled myself that I already knew how to get those answers. Boy, was I wrong! Now, as an adult, I’m having to re-learn math. But at least now I know not to fool myself!

—Richard Seidel

Special Advice to Improve Your Writing

The techniques we described to improve your math and science skills are very similar to what you can do to improve your writing!

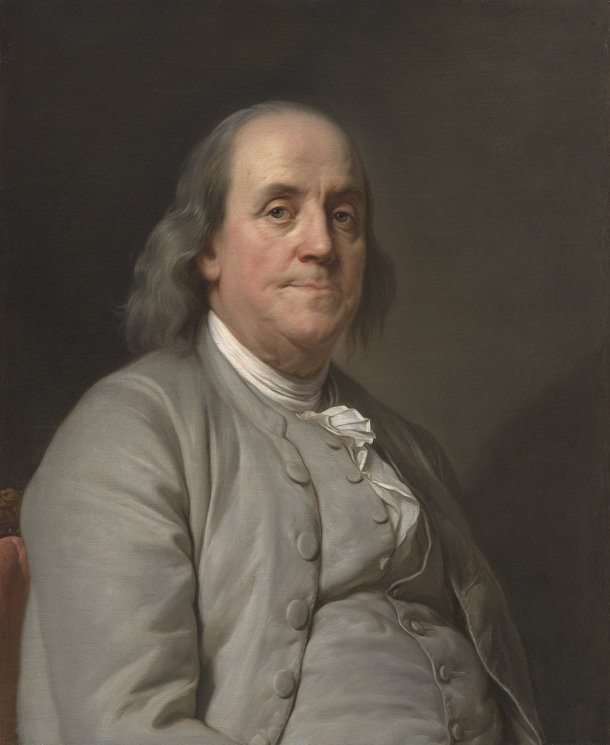

Famous statesman Benjamin Franklin was a terrible writer when he was a teenager. He decided to do something about his problem. He took pieces of excellent writing and jotted down a word or two of the key idea of some of the sentences. Then he tried to re-create the sentences from his head, just using the key ideas as hints. By checking his sentences against the originals, he could see how the originals were better—they had a richer vocabulary and used better prose. Benjamin would practice this technique again and again. He gradually began to find that he could improve on the originals!

Famous American statesman Benjamin Franklin was a lousy writer as a teenager. He decided to change himself by actively developing his writing links.

As Benjamin’s writing improved, he challenged himself to write poetry from the hints. Then he began scrambling the hints, to teach himself about how to develop a good order in his writing.

Notice—Benjamin wasn’t just sitting around memorizing other people’s good writing. He was actively building writing links, so he could more easily pull good writing from his mind.

Can you think of how you might do something similar if you want to improve your artistic ability?

Back to the Piano

So, was I learning the piano well when I was reading the comic book? Not at all! I broke just about every rule of good learning. I wasn’t deliberately focusing on the new and harder material. Instead, I was using lazy learning, mostly only playing songs I already knew well. Sure, I slept on my new learning, but with only five minutes of real study a day on new information, it was no wonder I didn’t make much progress. I wasn’t learning enough new material to be able to interleave anything. Gradually, because I wasn’t getting better quickly, I lost what little interest I had. My parents never realized the trick I played on them—and on myself. Today, sad to say, I can’t play the piano at all. This is a double shame because research is showing that learning a musical instrument is healthy for your brain in many ways. It can help you learn countless other skills more easily.

Lady Luck Favors the One Who Tries

You may say, “But, Barb, there’s so much to learn! How can I ever make brain-links out of it all when I’m trying to learn something new, abstract, and difficult?”

Lady Luck favors the one who tries.

The short answer is, you can’t learn it all. Your best approach is to pick some key concepts to turn into brain-links. Link them up well.

Remember what I like to call the Law of Serendipity: Lady Luck favors the one who tries.

Just focus on whatever section you are studying. Follow your intuition on the most important information to link. You’ll find that once you put the first problem or concept in your library of brain-links, whatever it is, then the second concept will go in a bit more easily. And the third more easily still. Not that all of this is a snap, but it does get easier.

Good fortune will smile upon you for your effort.