Four

TRANSPORTATION GETTING THERE FROM HERE

Los Angeles’ city-builders never doubted that transportation was the key to success. Historian Virginia Cromer related an impression of a new resident in the neighborhood of Crown Hill west of downtown in the first decade of the 20th century: “There were not many cars at the time on the Hill; travel was by foot. Los Angeles Railway’s yellow carline or the big red cars for longer distances.” When the development of Silver Lake Reservoir made development on the Hill feasible, landowner Joseph Witmer hired San Francisco cable builder Andrew Hallidie to build a car line running from Second and Spring Street downtown to insure successful subdivision of his 600-acre parcel. Transportation was for fun as well, and Angelenos never tired of jaunts to the country to explore their beautiful new home. However, the lure of the auto was becoming increasingly hard to resist, and it demanded increasing investment in infrastructure for tunnels and roadways. An excellent shuttle, the motor car, and its cousin the truck, also offered reliable access to water and rail transportation.

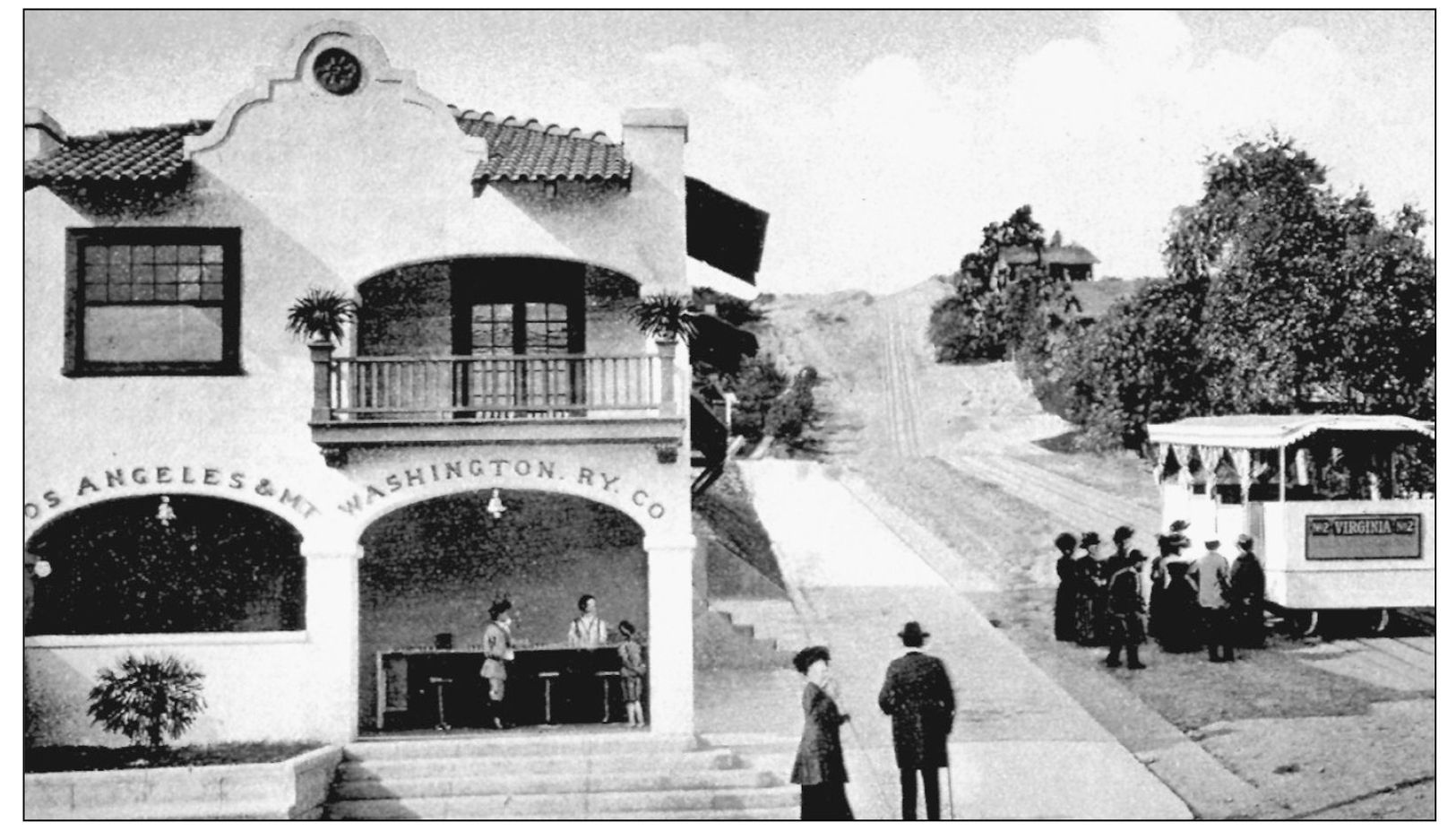

INCLINE STATION, LOS ANGELES AND MT. WASHINGTON RAILWAY. Los Angeles and Mount Washington Railway built an attractive Mission Revival building at the Incline Station complete with refreshment bar for waiting passengers. The line continued upward to the Mount Washington Hotel where visitors could stroll through the expansive gardens and enjoy a panoramic view of Los Angeles.

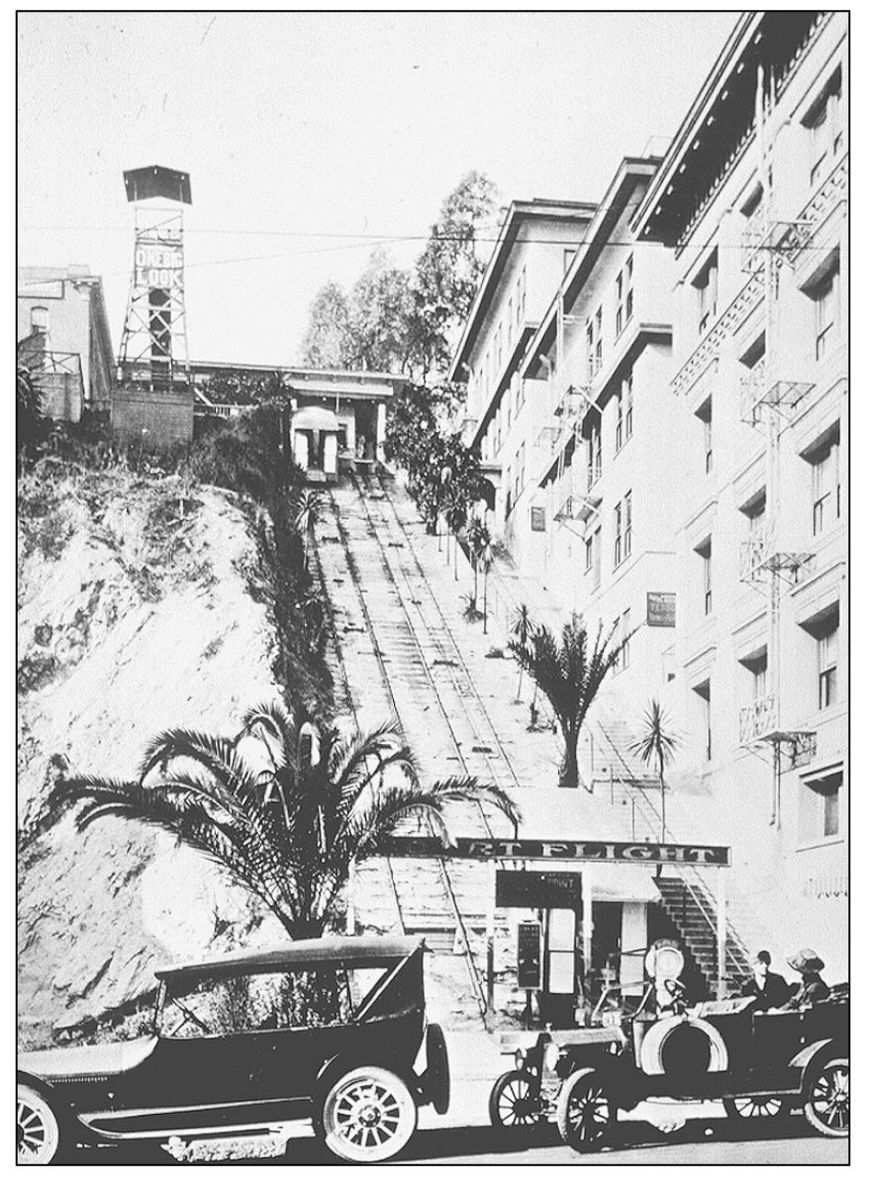

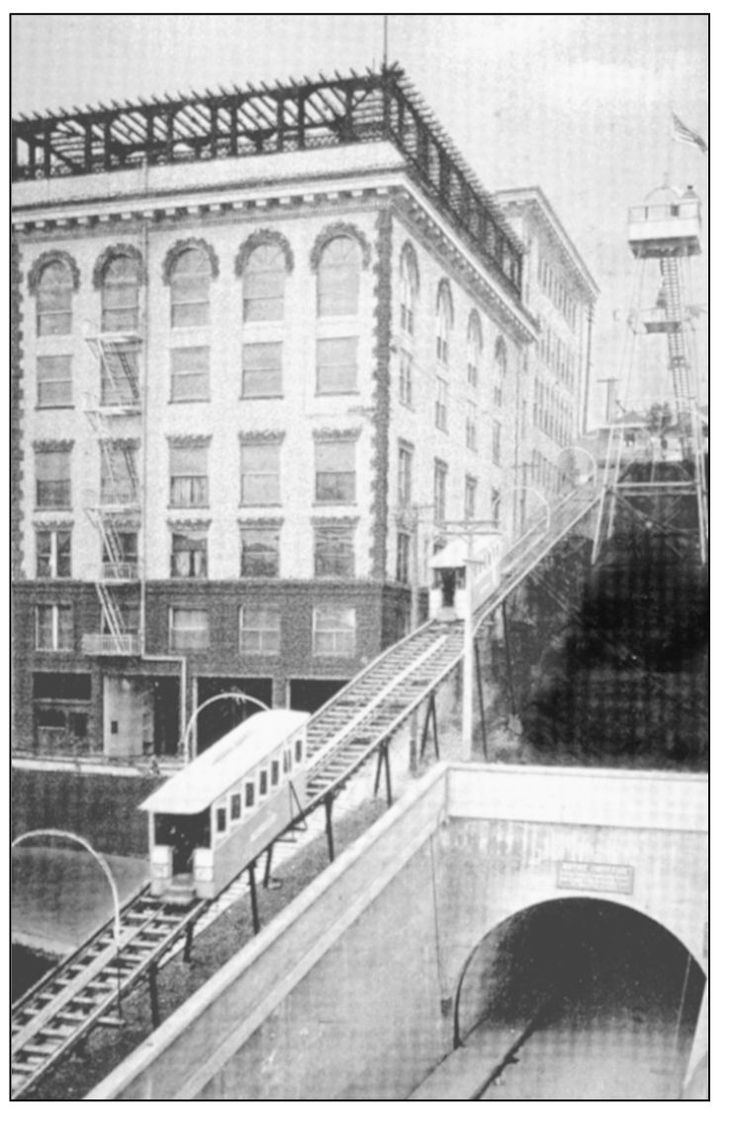

COURT FLIGHT 1905. Another less well-known Los Angeles funicular was Court Flight. Located on Broadway between First and Temple Streets, it raised passengers up the steep slope from Broadway to Court Street, just below the summit on Hill Street. Built in 1904, the facility burned in 1943.

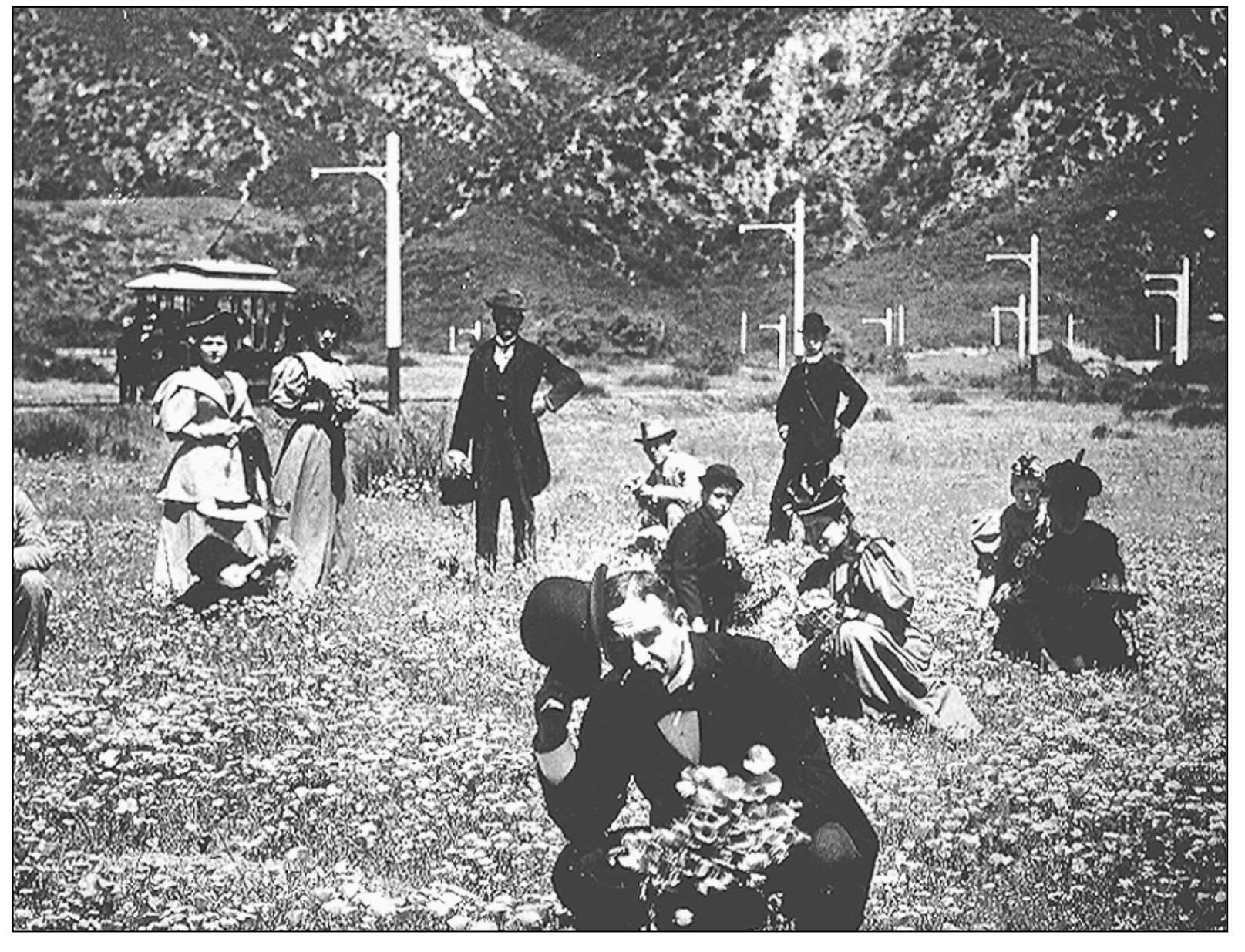

TROLLEY LINE AND POPPIES, 1904. This 1904 postcard celebrates the aromatic, bright orange state flower. These pleasure-seekers on the way to Mt. Lowe rumbled out to the bright fields in the pristine countryside of the San Gabriel foothills.

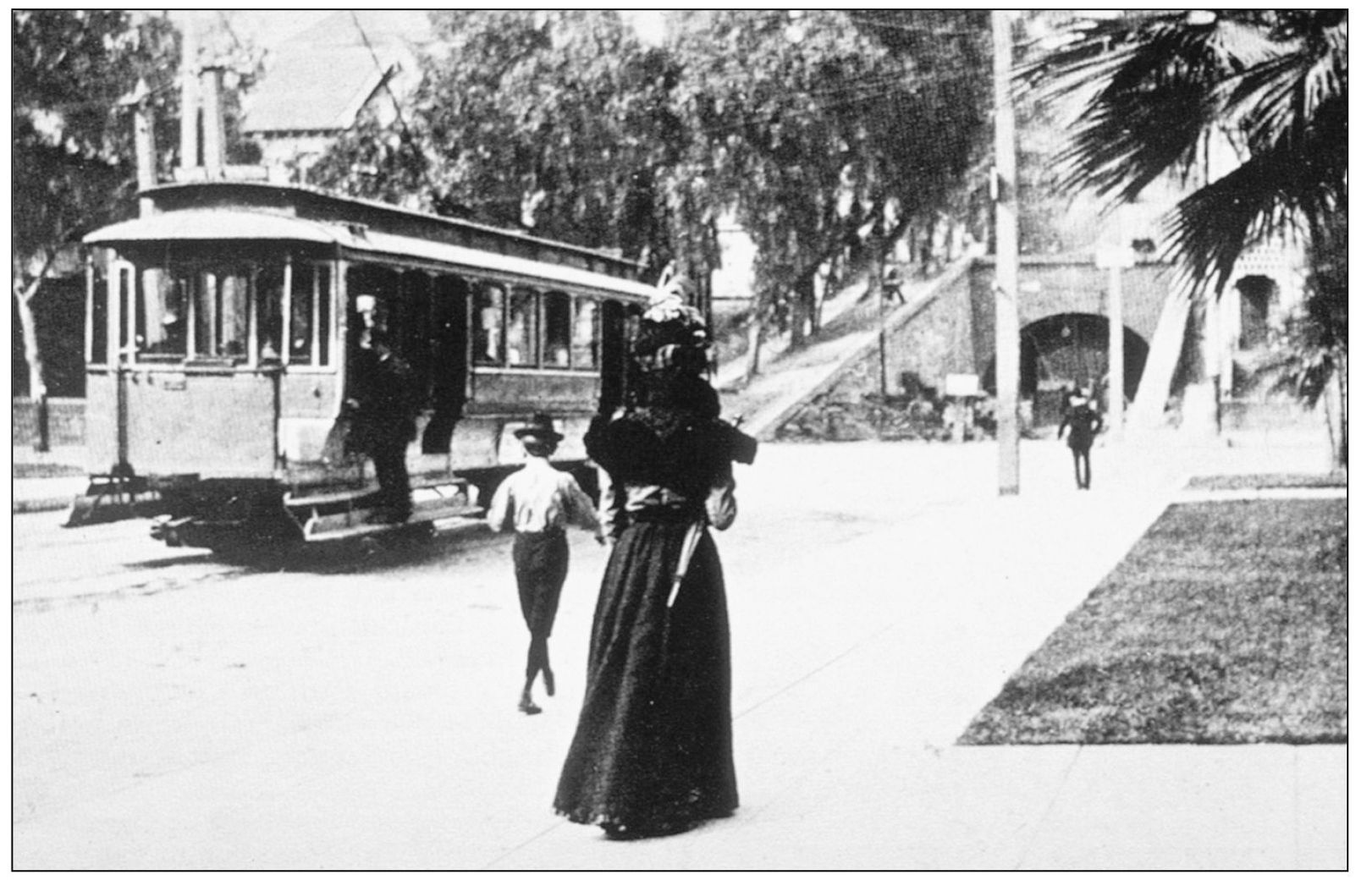

HILL STREET TUNNEL, BUNKER HILL. Downtown Los Angeles’ topography was as opportunistic as the aims of its citizens. Sloping upward from the west bank of the Los Angeles River, the terrain presented a set of arroyos and rolling hills moving west from downtown. One of the most formidable geographic barriers was Bunker Hill. Continued progress westward was necessary and by 1909 a tunnel had been bored through the Hill.

ANGEL’S FLIGHT. For easy access up Bunker Hill to the fashionable mansions on its sides, Angel’s Flight Railway was constructed. A short funicular, it traveled 335 feet with a 33% grade. The charge for a ride in 1910 was a penny. Bunker Hill was effectively leveled for redevelopment in 1970; Angel’s Flight was moved a block away and then restored for service in 1995.

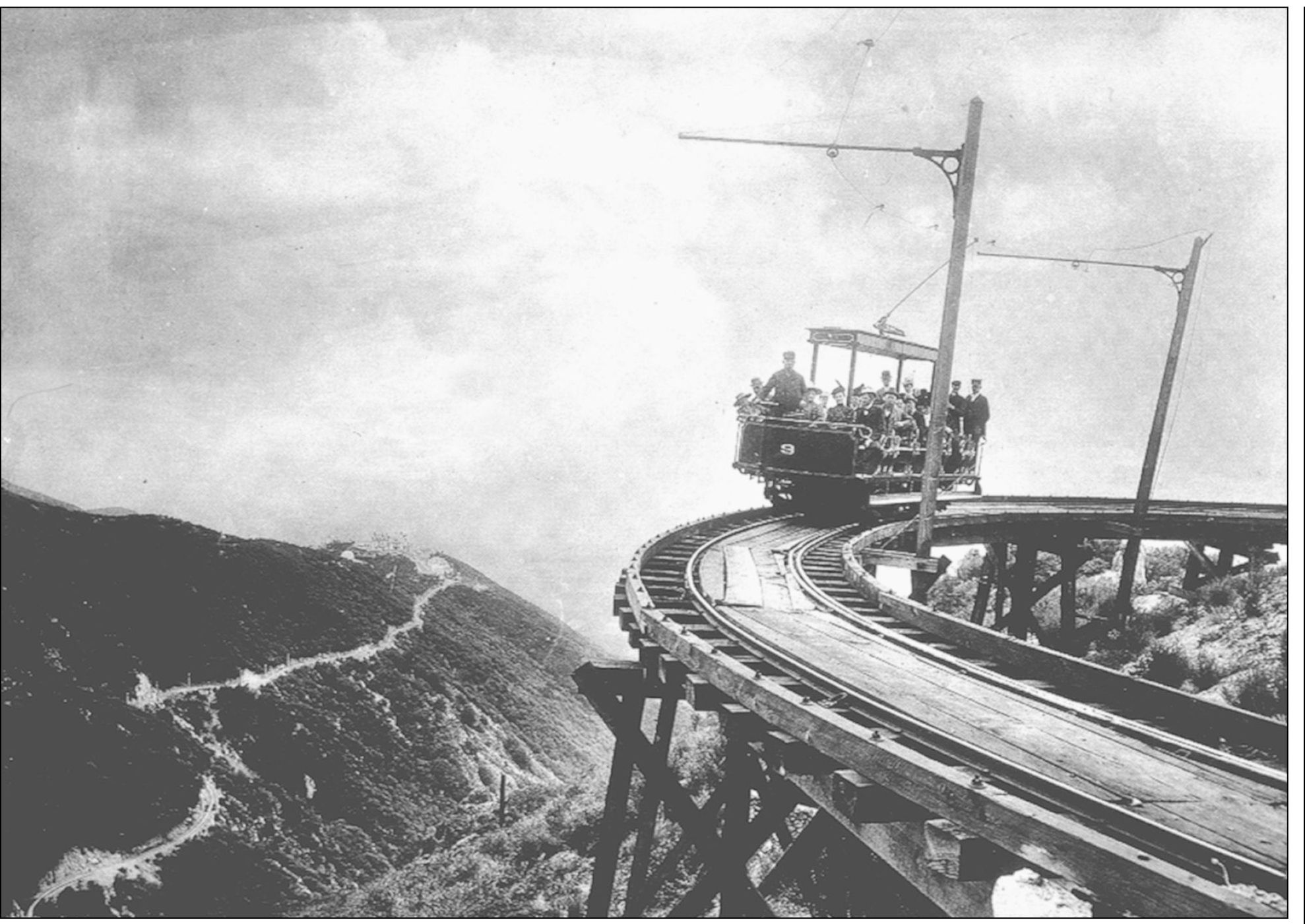

MOUNT LOWE RAILWAY CIRCULAR BRIDGE. Balloonist S.C. Lowe, whose profession precluded any fear of flight or heights, determined to share the thrill of aerial suspension with Angelenos. Hiring cable car builder Andrew Hallidie, Lowe put into operation in 1893 The Great Incline to scale the foothills of the San Gabriel Mountains. The inaugural ascent on the Fourth of July brought passengers 1,500 feet from a pavilion in Rubio Canyon 2,000 feet above sea level with a 60% grade to the summit of Echo Mountain. 127 curves and 18 trestles later, the invigorated passengers arrived at the 5,000-foot summit which offered a restaurant, hotel and cabins. The Circular Bridge, a tight curve of railway track, offered unparalleled views of Pasadena and Altadena, if the rider wasn’t afraid to look. The rail line ran until 1938 although the facilities were destroyed earlier in fires and floods on the mountain.

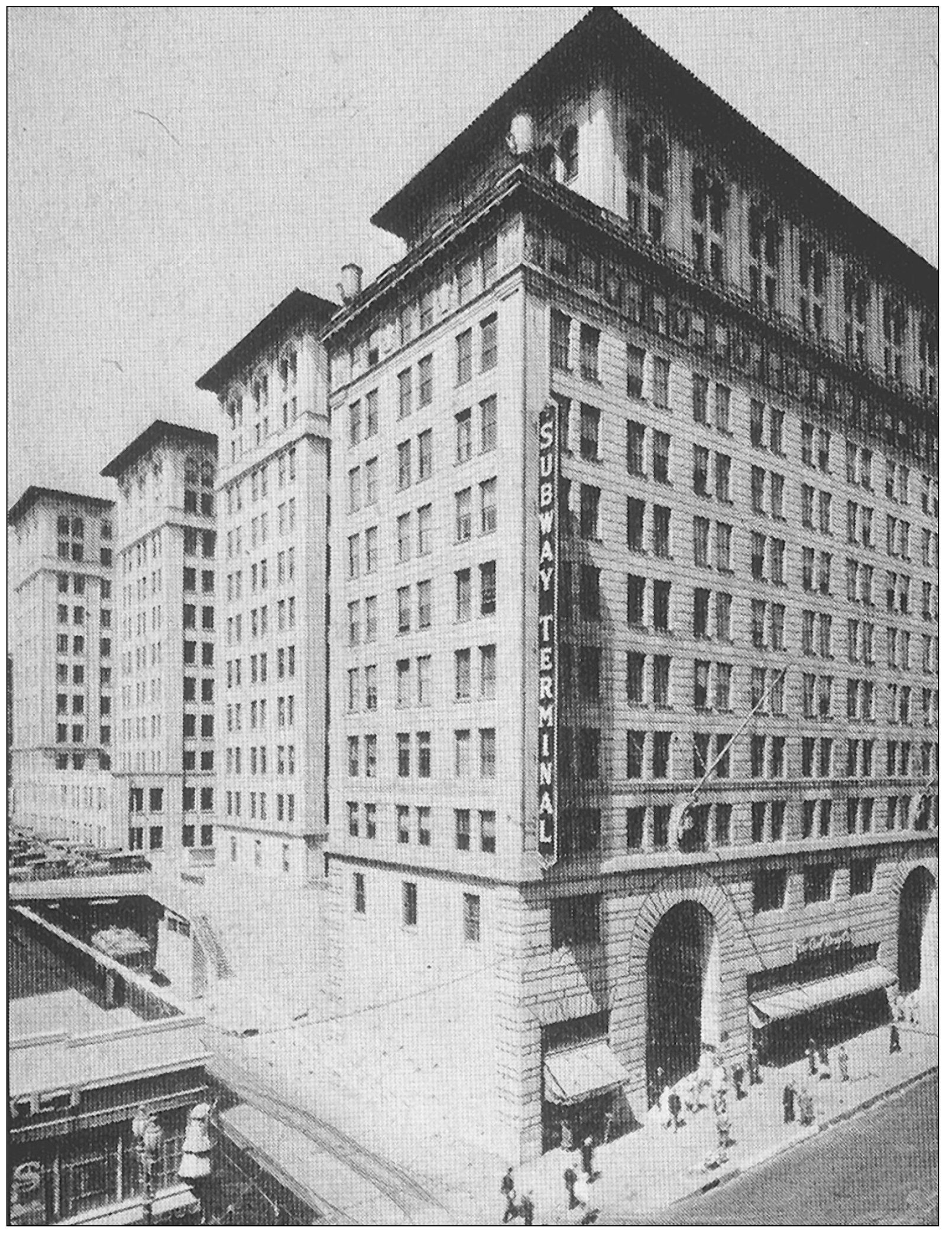

OPENING OF LOS ANGELES SUBWAY IN 1926. In 1926 the Pacific Electric Railway had an ambitious plan for a Los Angeles subway to provide rapid access to downtown from the west side and San Fernando Valley. A tunnel begun in 1924 ran from First Street and Glendale Boulevard to an underground station at Fourth and Hill Streets below the Subway Terminal Building.

SUBWAY TERMINAL BUILDING. The elegance and architectural distinction of the Beaux Arts Subway Terminal Building, designed by Los Angeles architects Schultz and Weaver in 1926, declared the importance of transportation to Los Angeles . The building was essentially a prestigious downtown office building whose lobby served as a street railway concourse.

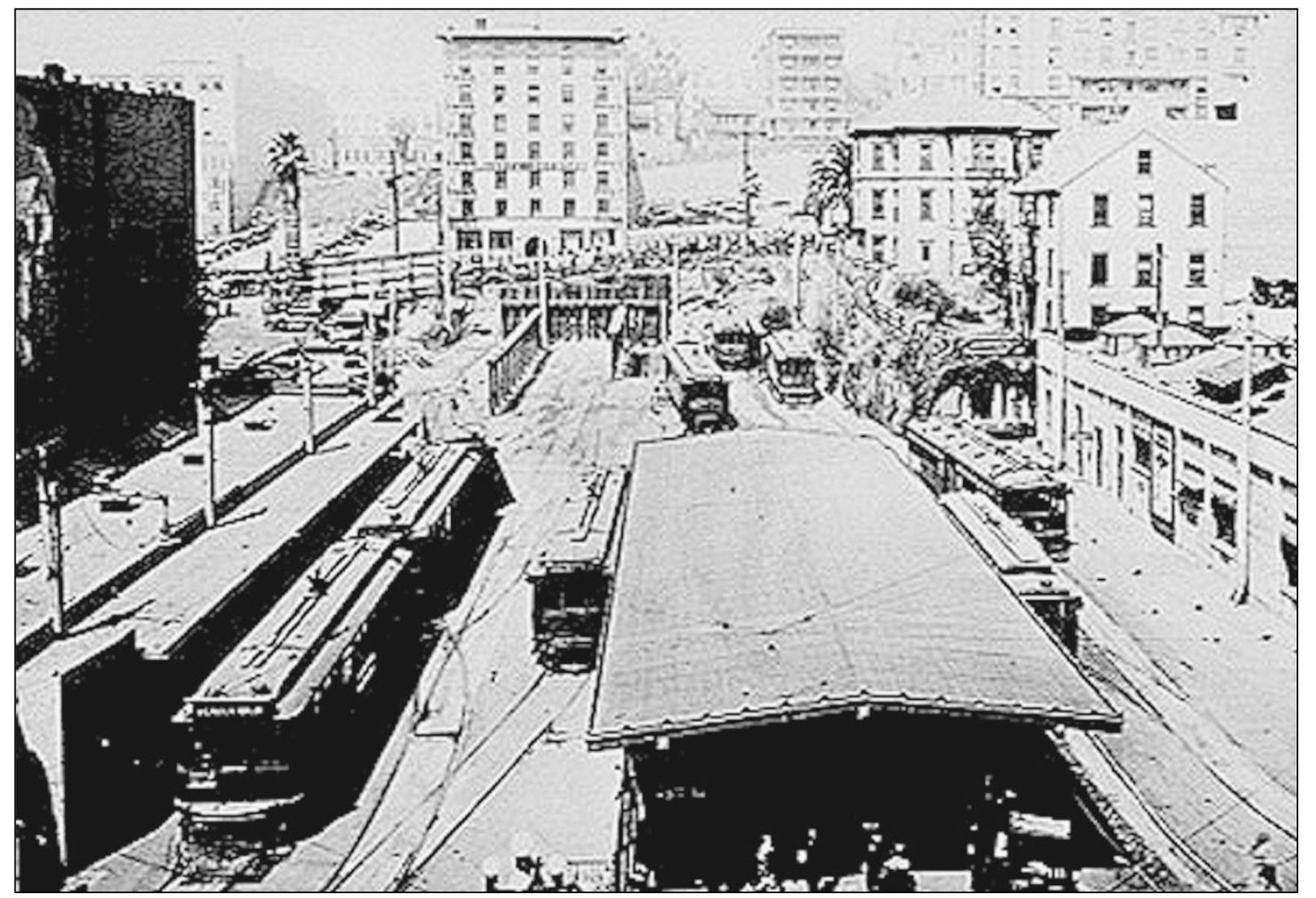

BUILDING THE SUBWAY TERMINAL BUILDING. This 1919 photo shows facilities operating on Hill Street during the planning of the Subway Terminal Building.

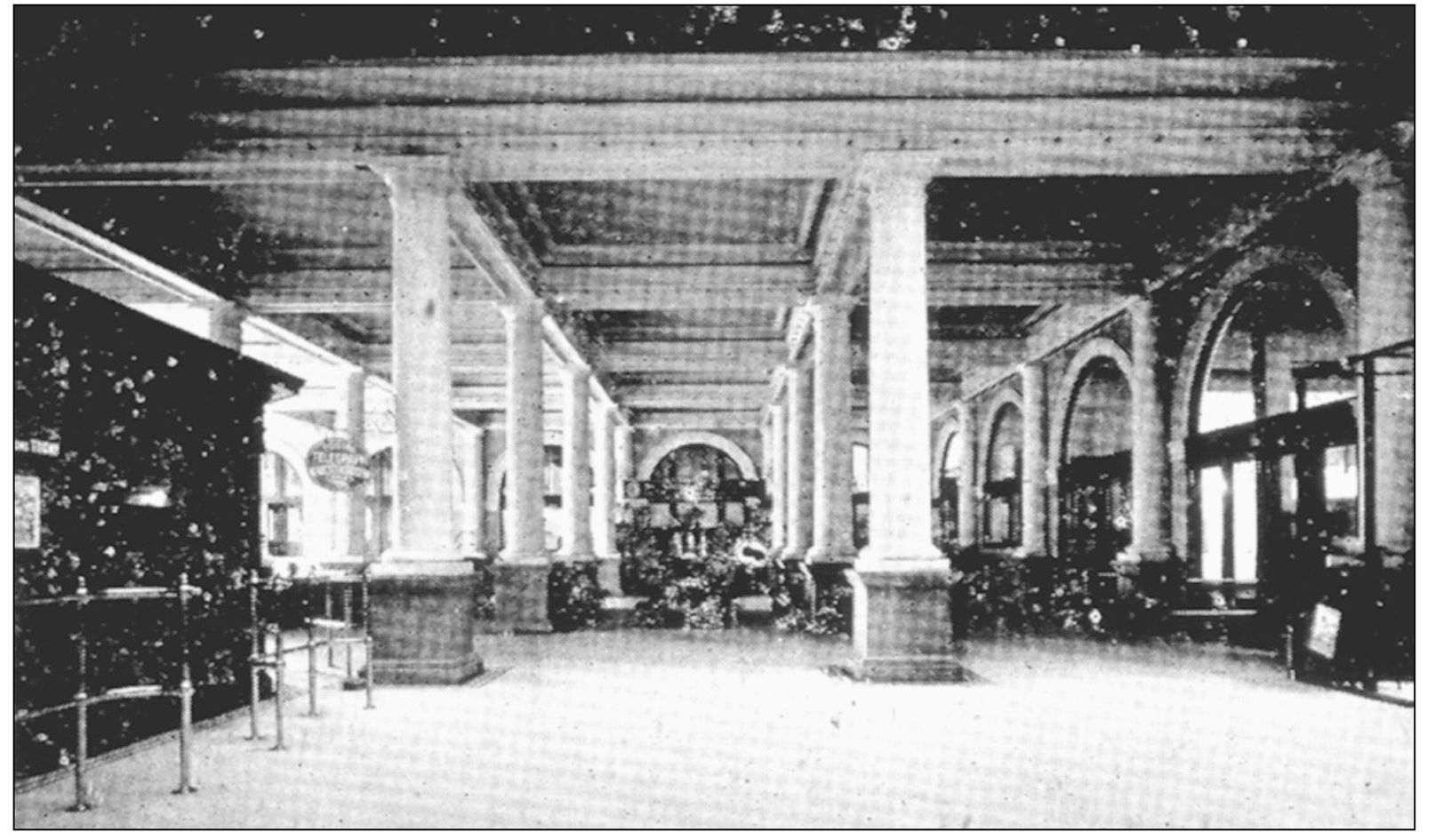

WAITING ROOM, PACIFIC ELECTRIC RAILWAY BUILDING. The Pacific Electric Railway Building at Sixth and Main Street had a service concourse open 24 hours a day. Its impressive waiting room with classical pillars and arched door opening received outdoor light from a wire glass ceiling. All cars left from this station except those going westward to beach cities and north to Glendale and Burbank, which originated at the Subway Terminal Building.

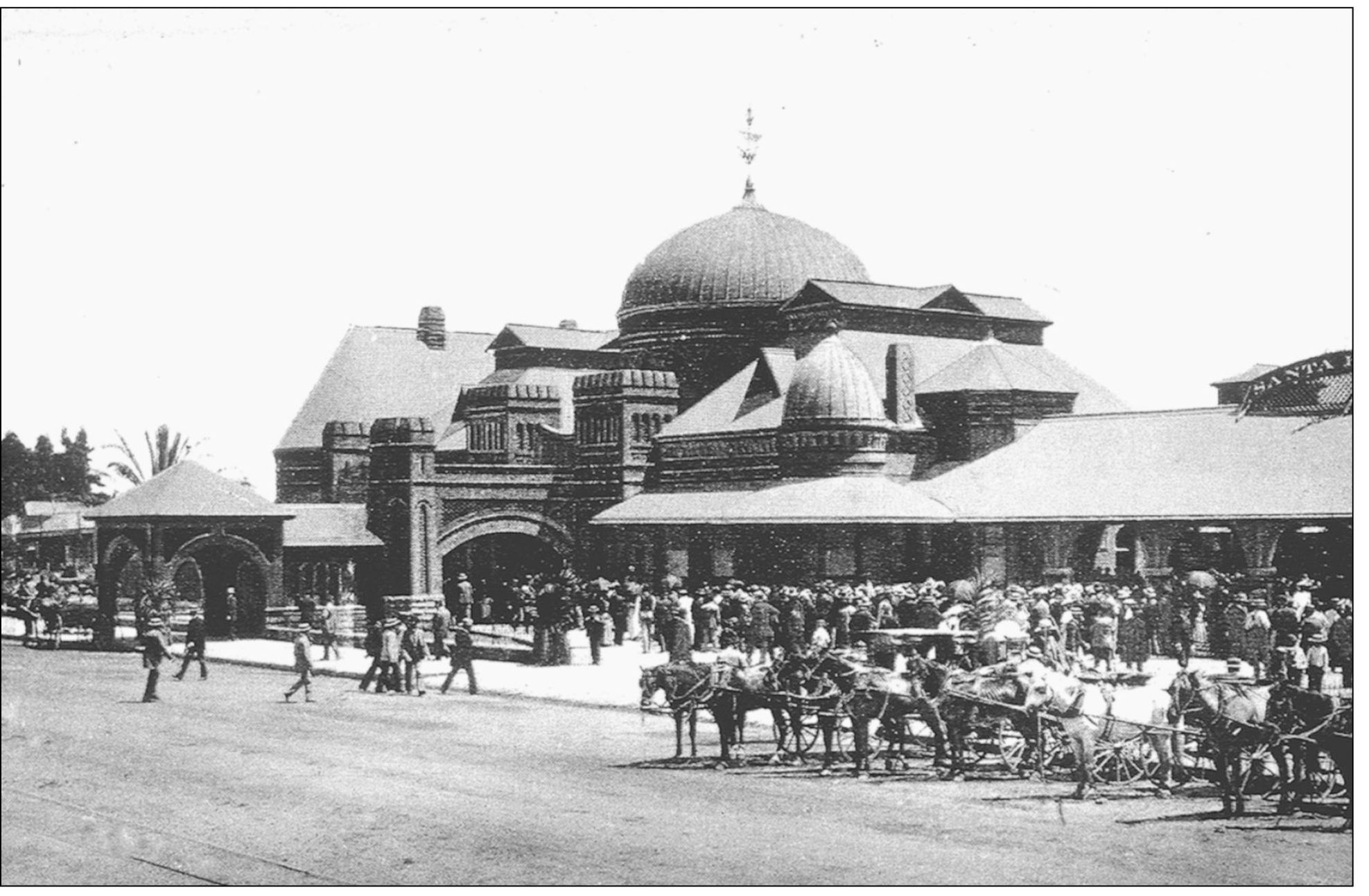

LA GRANDE STATION, SANTA FE RAILWAY. The Moorish Revival style La Grande Station of the Santa Fe Railway opened with great fanfare on July 29, 1893. More than 50 trains daily departed from the station, which stood on Santa Fe Avenue between First and Second Streets. The main depot, 350 feet in length, had a central domed rotunda, tile floors, and a stained glass window. An adjoining garden had a landscaped, kite-shaped walk and a miniature replica of the Santa Fe’s excursion route to San Bernadino, planted in palms.

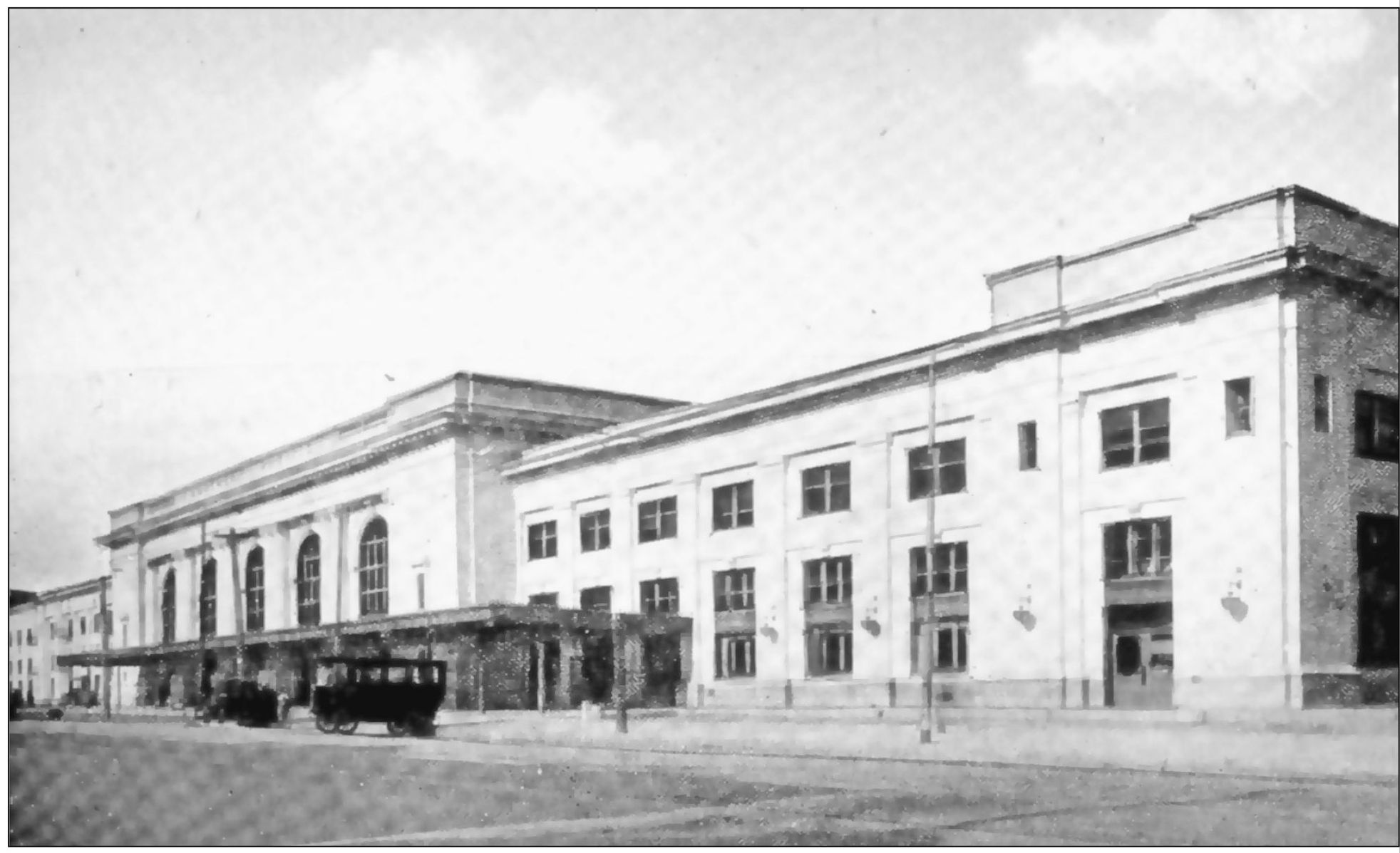

SOUTHERN PACIFIC DEPOT. In April 1881, Los Angeles’ centennial year, Southern Pacific Railroad, having driven south to Los Angeles, turned east to reach El Paso, Texas. In the following December it connected with the westbound Texas Pacific. At last Los Angeles was the western terminus of a transcontinental railroad. This stately Beaux Arts station replaced the first Southern Pacific “Arcade” Station.

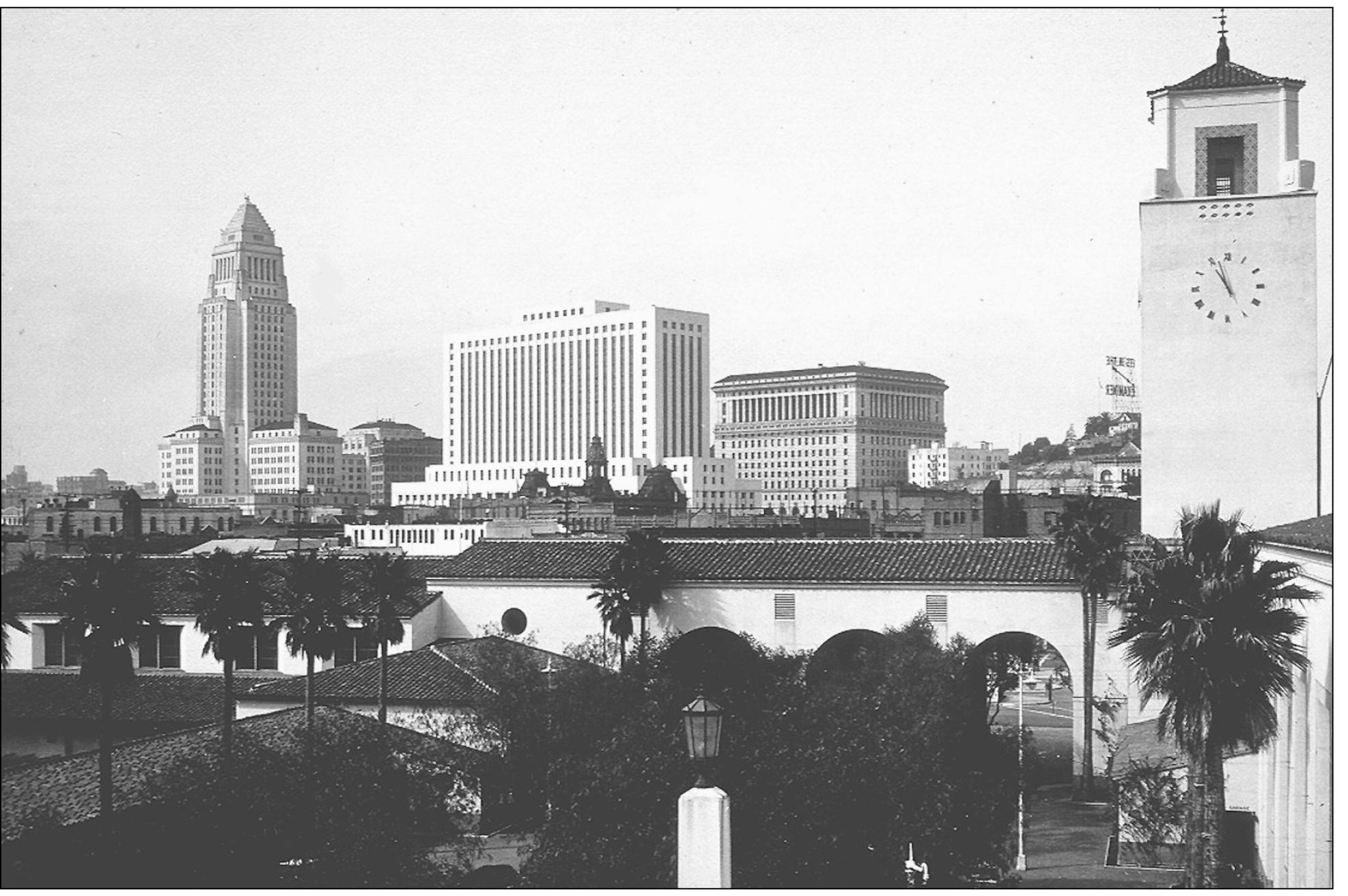

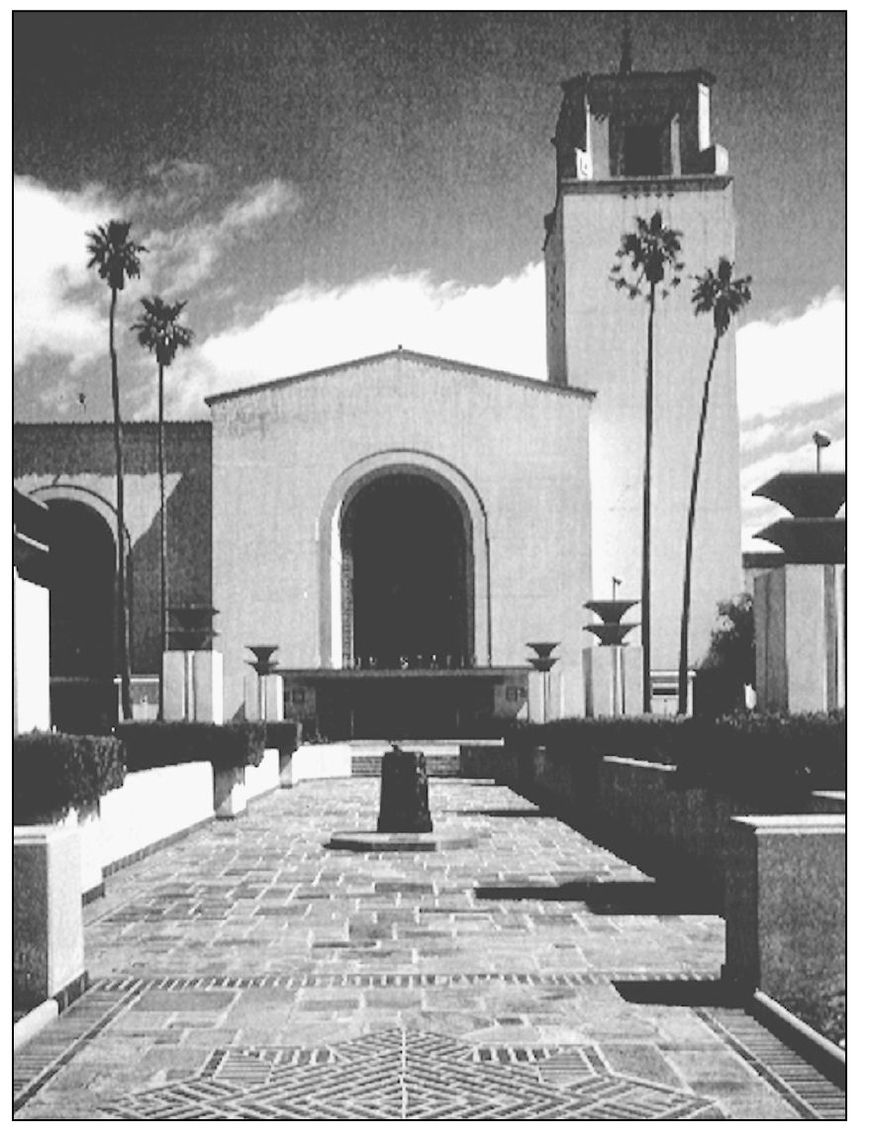

UNION STATION PASSENGER TERMINAL, ALAMEDA AND SUNSET BOULEVARDS, LOOKING WEST TOWARD CITY HALL. Historians Leonard and Dale Pitt describe Union Passenger Terminal as “the last of the great American railroad stations.” Designed by a consortium of the city’s architects headed by Donald B. Parkinson, the station comprises a group of one-story, stucco, tile-roofed buildings dominated by a 135-foot observation and clock tower. The structure is a highly artistic rendering of Spanish Colonial Revival architecture with a Moderne sensibility. The handsome interior has a 52-foot tall ceiling, marble floor, tall arched windows, and superb California tile ornamentation.

UNION STATION COURTYARD. Careful attention was given to space planning throughout the Union Station complex. Brick-patterned walks, light standards, and landscaping were carefully woven into a composition that integrated indoor and outdoor space through a Moderne interpretation of Mediterranean architectural elements.

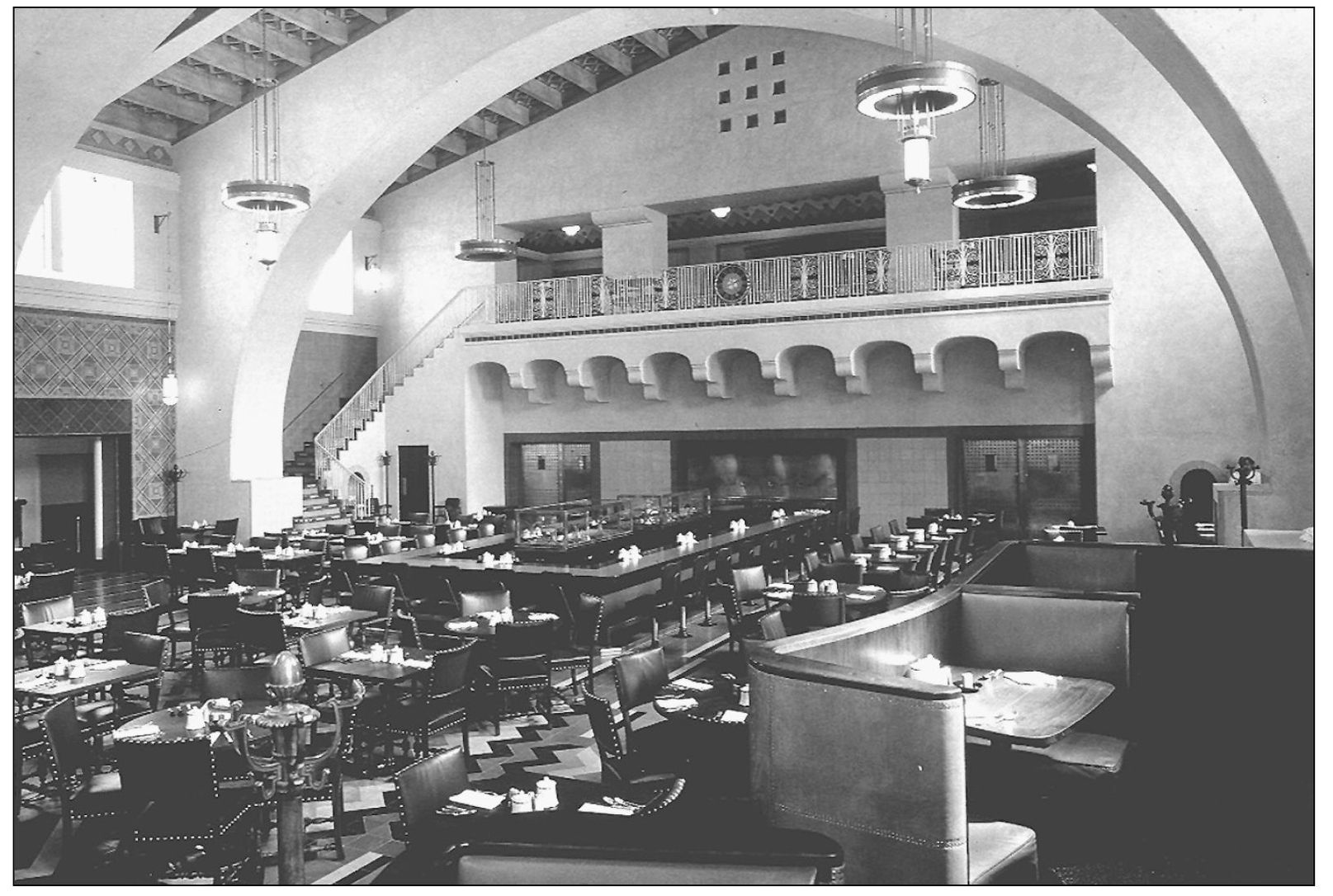

UNION STATION RESTAURANT. The decorative details in this interior space—patterned ceiling, extensive use of tile, and decorative metal grill work—work in harmony with decorative use of architectural structure revealed in piers and arches. This unity of detail and structure is a fundamental design principle apparent throughout the station complex.

PASADENA FREEWAY TUNNEL. The Figueroa Tunnel through Elysian Park is on the Arroyo Seco Parkway, a six-mile throughway from downtown Los Angeles to Pasadena. Both freeway and parkway in its conception, the scale and detailing of its bridges and tunnels, as well as it location in a park system, suggest a Sunday drive rather than a daily commute. With its sunburst design, Figueroa Tunnel was one of several concrete entrances through Elysian Park that were styled in the Streamline Moderne.

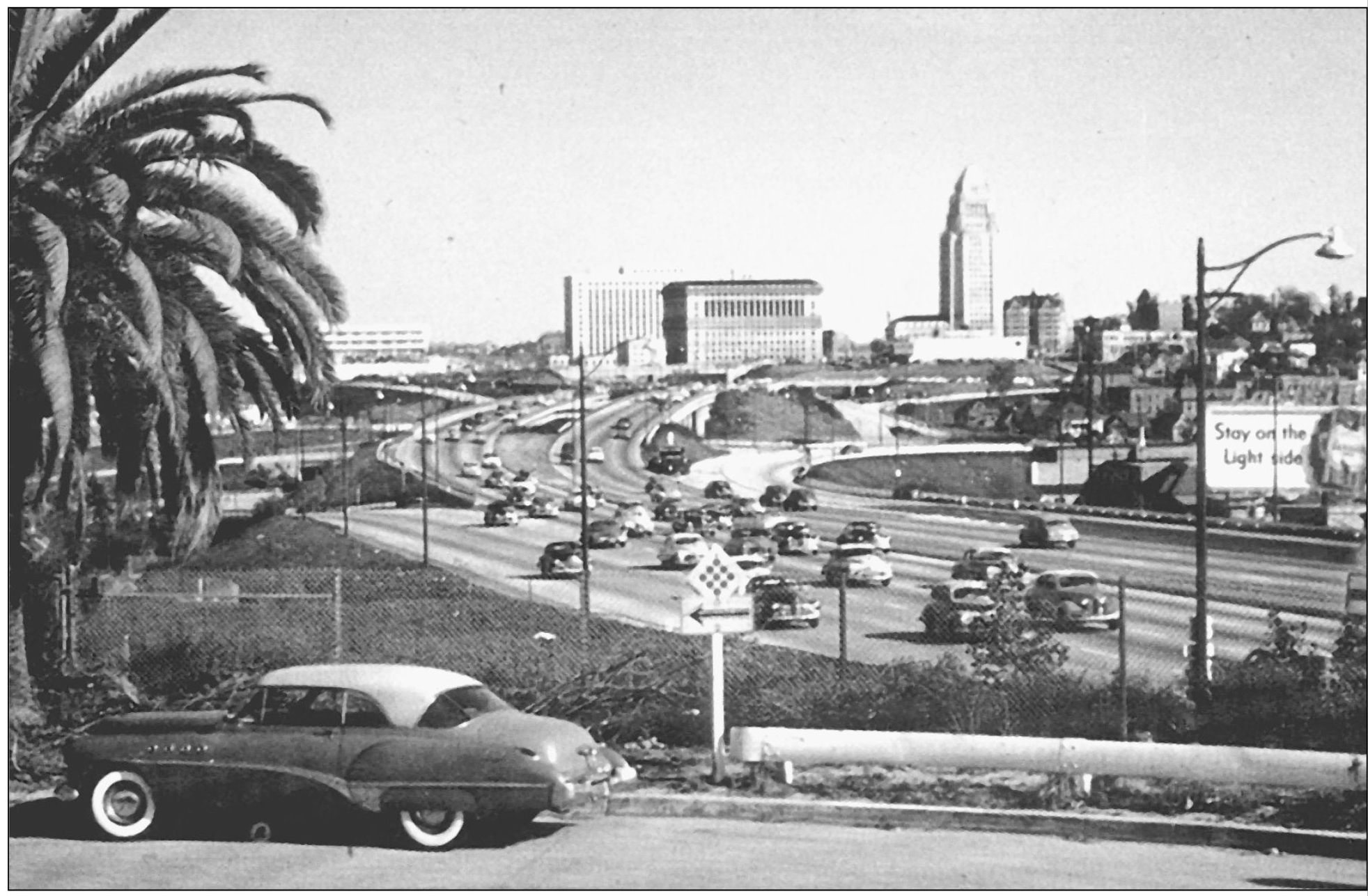

HOLLYWOOD FREEWAY. The Hollywood Freeway, completed in 1948, ran from downtown Los Angeles through Hollywood to the San Fernando Valley, which was then experiencing exponential post World War II population growth. The road was engineered with four lanes in each direction, functional and banked curves, paved shoulders, and extended access lanes. A true freeway, it had few landscaping or parkway features.

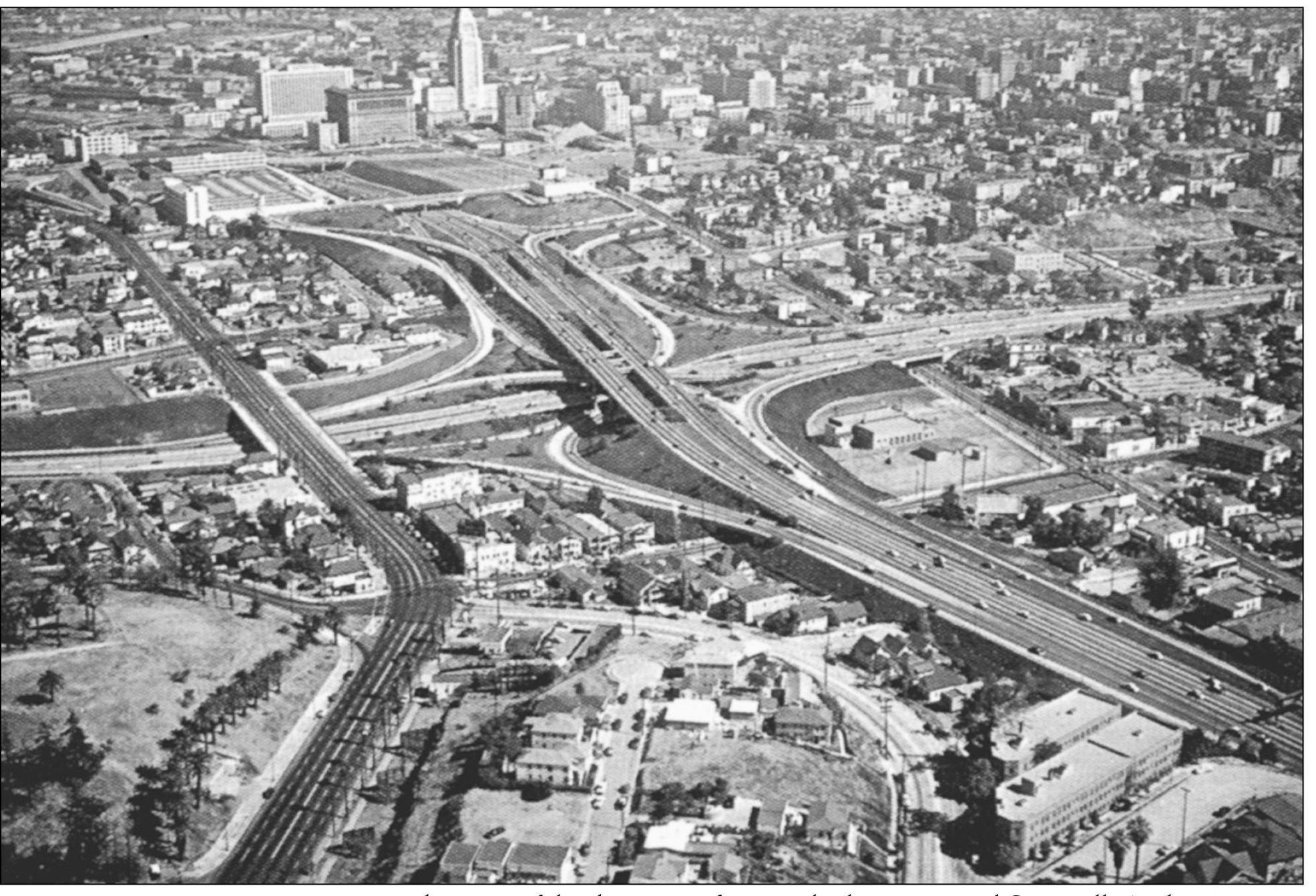

DOWNTOWN FREEWAYS. This view of the downtown freeways looks east toward City Hall. At the center is the “stack,” or four-level interchange connecting the harbor, Pasadena, and Hollywood Freeways.