Chapter 6

Downs and Down-Type Breeds

In addition to true Downs (Suffolk, Southdown, Oxford, Hampshire, Dorset Down, and Shropshire, for instance), I include in this chapter breeds with wool that looks and acts like that of the true Down breeds. All of the true Downs have colored faces and colored legs, and their wool is usually white. Some have a color gene, but they are the exception to the rule. The locks can be square and blocky or a bit tapered, but they usually are dense. Their fiber diameters run the gamut from the coarse end of Merino to the crisp feel you’d want for yarn intended for a tailored jacket and skirt.

The Down breeds originated in a part of southeast England sometimes called the Downs (meaning “hills”). For years, these breeds have more often than not been referred to as meat sheep, which means that many shepherds and even shearers believe their wool to be worthless. This wool is often sold to a wool pool, a market for fleeces of all breeds of sheep, which are graded, put into large bales, and then auctioned off. (When you buy a garment or a skein of yarn labeled as “wool” with no breed information, chances are there is some Down-type wool in there.) For some shepherds, just getting the wool to the market is a money-losing option, barely covering the shearer’s fee, and so instead of trying to sell it, they burn it, use it as mulch, or sometimes just store it. You may be able to find Down-type fleece if you go right to a farm that raises these sheep, but otherwise you may find it difficult to find as spinning fiber, because the unfortunate label “meat breed” has influenced the attitude of many handspinners and shepherds alike who think the wool is not good for yarn and fabric making. Nothing could be further from the truth. These are some of the bounciest and hardest-wearing wools, as well as fun to spin.

The crimp in these wools is remarkable. When you take a whole lock in your hand and look at it, you often can detect very little or no visible crimp structure. The fibers look a bit disorganized. But take out one single fiber and what do you see? Great crimp. Spiral in structure, around and around it goes. The fabulous thing is that crimp has exciting implications for what you can do with the yarns. Its bounciness and resiliency means no more sagging elbows in your sweater and no more stretched-out socks that slide around. In addition, many of these fleeces are very felt resistant. It’s true! These are the naturally superwash wools, no chemical processing necessary to avoid felting. Although it hasn’t been proven, I believe that this is another beneficial effect of the crimp structure. Because the spiral-shaped crimps constantly push away from one another, they remain independent of their neighbors, rather than lying close to them and moving against each other during washing. I like to think of it this way: Because of their crimp, fibers from other wools fit together like puzzle pieces, whereas the Downs’ fibers are puzzle pieces that don’t really quite fit. Their spiral crimp also provides great insulation. All of that air between the fibers keeps us warmer in our Southdown sweater than we might be in a sweater knit with yarn spun from one of the longwools.

The micron count places these wools firmly in the middle range of fiber diameters, adding to their strength and wearability and making them appropriate for a wide variety of projects. Though I knew this wool was desirable, it wasn’t until I began to prep and spin a wide variety of sample yarns that I realized how truly versatile and useful the Down-type wools could be. Because of the fibers’ springiness, durability, and resistance to felting, socks were always my first idea for what to do with them, but I’ve come to realize that their value goes well beyond socks. What a great sweater yarn the wool would make, with both resilience and also natural insulating properties!

Not only are these wools very useful, but they are a real pleasure to spin and work with. Some of these fleeces have a longer staple than others, so when you’re shopping for any of the Down-type breeds, look for fleeces that are a bit longer stapled. This, of course, will depend on the breed you choose, just as within the other wool categories. Southdown, for instance, ranges from 11⁄2 to 4 inches for a full year’s growth; Horned or Poll Dorset may have up to 5 inches growth in a year. Since the sheep are being raised for market, they are often shorn only once a year. Sheep breeds like Wensleydale that have more wool growth — up to 12 inches in a year — are often shorn twice a year, because a 5- or 6-inch staple is much easier for handspinners to manage. On the other hand, if they’re being used for show, the Downs may be sheared multiple times a year in order to reveal their body conformation. In this case, the sheep are rarely seen in full fleece, as is true for breeds being raised mainly for their wool.

A word of advice about spinning these fibers: spin the singles finer than you think is necessary for the yarn you want, because the yarns will expand and fluff up when you wash them.

Characteristics of the

Down Types

Black Welsh Mountain

Origin: Welsh Mountain

Fleece weight: 21⁄2–51⁄2 lbs.

Staple length: 2"–4"

Fiber diameter: 28–36 microns

Lock characteristics: Dense, blocky; may have some kemp

Color: Black

Clun Forest

Origin: Several British hill breeds

Fleece weight: 41⁄2–9 lbs.

Staple length: 21⁄2"–5"

Fiber diameter: 25–33 microns

Lock characteristics: Crimp varies from sheep to sheep; is not consistent over the lock

Color: White

Dorset Horn/Dorset Poll

Origin: Spanish Merinos/native Welsh Sheep

Fleece weight: 41⁄2–9 lbs.

Staple length: 21⁄2"–5"

Fiber diameter: 26–33 microns

Lock characteristics: Dense/blocky; irregular crimp

Color: Usually white

Hampshire

Origin: Native Hampshire/Southdown/Cotswold

Fleece weight: 41⁄2–10 lbs.

Staple length: 2"–4"

Fiber diameter: 24–33 microns

Lock characteristics: Blocky, dense

Color: Usually white

Montadale

Origin: Columbia/Cheviot

Fleece weight: 7–12 lbs.

Staple length: 3"–5"

Fiber diameter: 25–32 microns

Lock characteristics: Dense, uniform crimp

Color: Usually white, but some black

Oxford

Origin: Native sheep/Hampshire/Southdown/Cotswold

Fleece weight: 61⁄2–12 lbs.

Staple length: 3"–5"

Fiber diameter: 25–37 microns

Lock characteristics: Blocky, dense

Color: White

Shropshire

Origin: Native sheep/Southdown/Leicester/Cotswold

Fleece weight: 41⁄2–10 lbs.

Staple length: 21⁄2"–4"

Fiber diameter: 24–33 microns

Lock characteristics: Dense, blocky

Color: White (rarely there may be color)

Southdown

Origin: The first Down breed

Fleece weight: 5–8 lbs.

Staple length: 11⁄2"–4"

Fiber diameter: 23–31 microns

Lock characteristics: Dense, blocky

Color: Usually white, some colored

Suffolk

Origin: Southdown/Old-Style Norfolk Horn

Fleece weight: 4–8 lbs.

Staple length: 2"–31⁄2"

Fiber diameter: 25–33 microns

Lock characteristics: Dense, blocky

Color: Usually white, rarely gray

Skirting a Fleece

Often when a farm is raising sheep for meat rather than wool, as in the case of the Down-type breeds, little or no thought is put into the fleece. You may find that the fleeces haven’t been skirted (tags and belly wool removed, along with the wool that sees the most wear while it’s still on the sheep), and also that there will be some vegetable matter (VM) as well as plenty of dirt. This may look really bad, but usually you can remove the dirt with a few good soaks (see Scouring Down-Type Wools, below).

If a fleece you select hasn’t been skirted, this process is easy enough to do. Find a place where you can spread the fleece out. When I’ve helped during shearing at local farms, they usually do this on a skirting table. The table is a wooden frame covered in wide-mesh screening, so that when the fleece is shaken, the larger bits of VM fall to the ground. Most of us don’t skirt enough fleeces to make it necessary to obtain a table, so laying out a sheet or other covering is quite adequate for the purpose.

When you spread out the fleece, you’ll see that it does want to stay together, so it’s easy to spread it out into the shape it was on the sheep. Once you’ve laid it out, start skirting by just removing the edge bits. You can be brutal about this. Look at it with a critical eye. Are those extremely short fibers going to add beauty to your yarn? Do you really want to try removing that stuff that looks like thick mud, but may not be? That neck wool looks soft, but it will take a ton of time to pick out all of that VM. Take all that wool that you’ve removed and put it in your garden. The sheep residue will help to fertilize your plants, and it breaks down so slowly that it will help keep the weeds down. (See photo of an unrolled fleece.)

Scouring Down-Type Wools

The technique for washing the Down-type wools is the same as what is described for the longwools: a wool scour (I use Unicorn Power Scour) and plenty of water with two washes and two or three rinses (see An Introduction to Hand Scouring). Many of these breeds have a fairly low grease content, but as I’ve said, if raised for meat, the fleece may be much dirtier than a fleece from a sheep raised with the handspinner in mind. It therefore takes the same amount of washing and rinsing as does a greasy fleece, but take care not to overscour, as this wool tends to get a little crunchy feeling after being washed. Using a lower temperature in the second wash and all the rinses sometimes keeps the fiber from feeling dry; the hot water is necessary for cutting the grease, but the dirt will come away in cooler water. In previous washing sections, I said to avoid moving the fleece from a hot-temperature bath to a cooler bath. One of the great things about the Down types is that most of them are felting resistant, and so this temperature change won’t matter here. (You may want to experiment to confirm that there’s no tendency to felt before doing this with a whole fleece.) You can also use a smaller amount of detergent than you would for washing a greasier breed. I sometimes like to put a little Unicorn Fibre Rinse in the last rinse water to counteract the dryness problem. It makes the fibers feel a bit softer, and it also cuts down on static. Some spinners use hair conditioner or cream rinse instead of Fibre Rinse. I avoid conditioners made for human hair as they may contain additives that you may not want on your wool, such as plastics that are difficult to wash away with the gentle washing we use for our wool textiles.

To help judge whether to use a fiber rinse in the last rinse water, wash just a small amount of fiber (an ounce or so) the way you plan to wash the whole fleece. Make sure you let your sample dry completely before making any final decisions. When you hold the scoured sample in your hand, you will know whether to use additives. Once again, experimentation is definitely your friend.

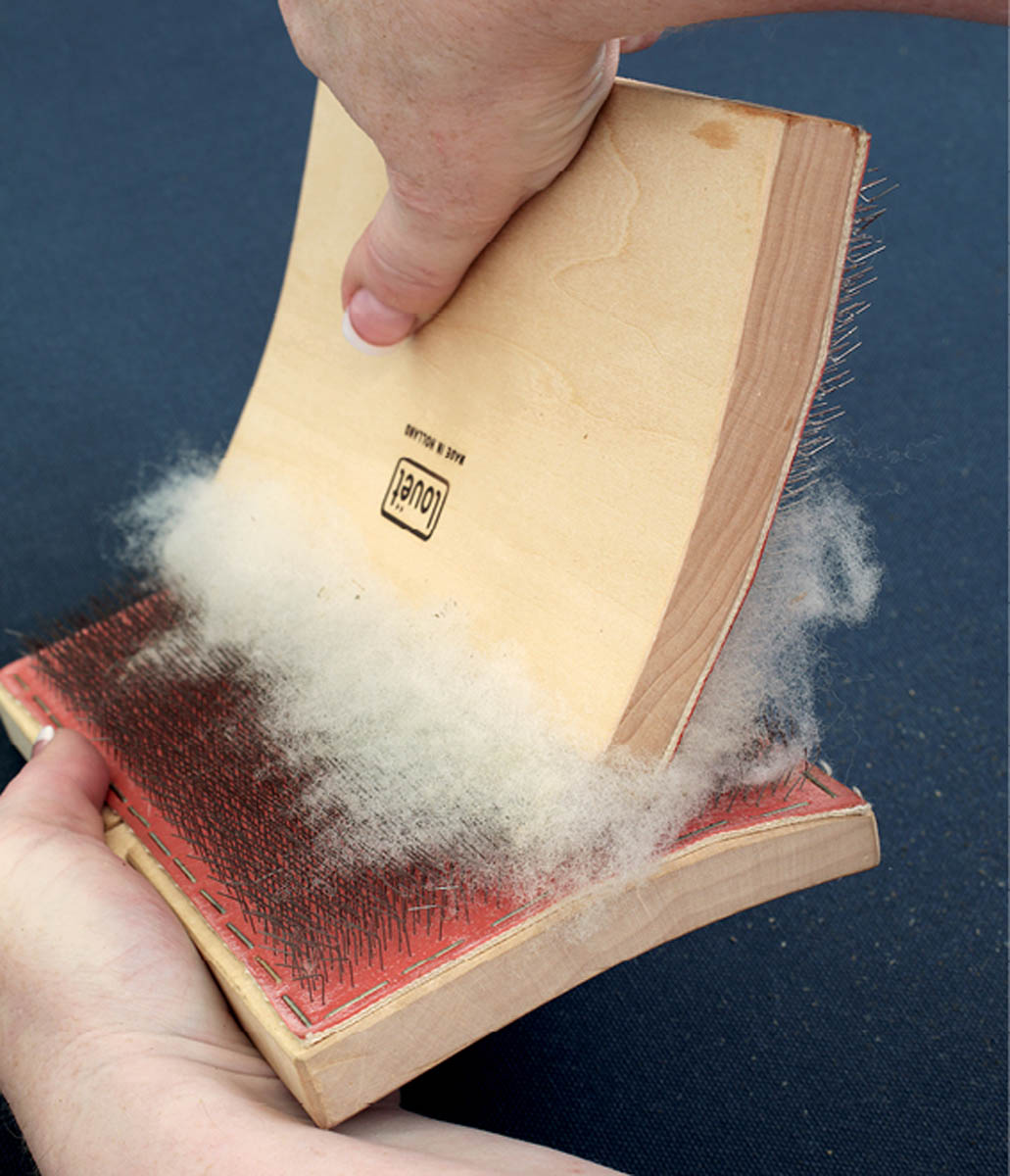

Handcarding Techniques

As I observed earlier, the crimp on most of the breeds in the Down-type category is somewhat spiral shaped. Each fiber likes to be independent and on its own. Instead of being all lined up like soldiers, these fibers want to act like it’s a party all the time, resulting in both a possible resistance to felting and that superior insulation that I’ve been praising. Carding, followed by woolen-type spinning, is fantastic for this kind of wool, as these techniques show off the Downs’ inherent strengths to the greatest advantage. The spiral crimp and elasticity of the fibers react beautifully when spun from a rolag (see How to Make a Traditional Rolag), which also encourages the fibers to push out against each other to make that warmest of yarns. I think of all of this as continuing the party.

Because the fiber party’s always going on, however, you may find that yarns spun from handcarded fiber are a bit uneven and inconsistent. If you comb wool, you can separate and remove short fibers. This is even true for one of the flicking methods, but it doesn’t happen when you card. One of the reasons I prefer carding the Down types rather than combing is the very fact that, because of the short staple length of the fibers, combing results in more waste than I like. Carding these wools results in a blend of fibers of different lengths and strengths, even though it also causes some unevenness and inconsistency in the spun yarn.

You can deal with the inconsistent singles that naturally occur when spinning carded, short-stapled fibers in at least two different ways. The first is to ply more than two singles together. For instance, 3- or 4-ply yarns disguise any number of flaws in the singles. The second is not to worry too much about it. Some of these inconsistencies will work themselves out with proper finishing of the skein, and once the yarn is used to make fabric, many of those issues won’t show.

There’s one final comment on the advantages of carding over combing or flicking the Down types. While it’s possible to use a flicker on some of the longer-stapled ones, it’s less advisable for fleeces from breeds like Southdown, which have a naturally short staple length (sometimes less than 3 inches). Getting a good grip on such a short fiber mass may make flicking an unpleasant operation. Your fingers can easily get in the way and be injured.

Picky, Picky

In contrast to combing or flicking, handcarding removes very little VM and none of the second cuts. It is therefore very important to pick out as many large bits of both by hand before you begin the carding process.

Spinners have developed many techniques in the use of handcards. I cover my favorite methods here, but they may not be comfortable for everyone. As you practice, you’re likely to find a style that is most comfortable for you. It may be a little challenging to learn to card by following static photos in a book. I encourage you to find someone who cards on a regular basis and ask them to show you, or take a lesson at a nearby fiber festival or shop that sells spinning equipment. Just five minutes with someone demonstrating in person can save you lots of time, struggle, and grief.

You can use flat- or curved-back-style handcards. Spinners usually choose one based on who taught them to card as well as what feels comfortable to them. (For a description of different kinds of handcards, see Handcards.) I prefer curved-back handcards because the method for using them is most comfortable for me.

In addition to curved and flat backs, you can select from a number of different carding cloths. The most widely available ones have 72-, 112-, or 212-pins (or teeth) per square inch (you may also see this specified as tpi, or teeth per inch). Cards with a larger number of pins per square inch are the best choice for fine fibers. This doesn’t mean that you can’t card fine fibers, such as Targhee, on a set of handcards with 72 pins per inch, but you usually need to make more passes to get the fibers completely opened up and ready to spin. More passes means more time spent in fiber prep, and it also means that there is more chance for adding neps to the carded fiber. Sometimes, each end of a fiber stays attached to each card as you transfer the wool from one card to the other. When this happens, the fiber gets stretched and then bounces back, forming a little knot, or nep. To avoid the neps, you need to take more care as you card, including making fewer passes.

No matter which kind of carder you use, don’t overload it. When you place your hand on top of the loaded card, you should easily be able to feel the pins through the fiber. Too much fiber makes carding more difficult and harder to manage, and results in more passes to get all the fiber carded. As has been repeated with advice for every preparation method, less is definitely more in fiber prep.

My Favorite Method with Curved-Back Handcards

Step 1. Take a small handful of fiber and place it about one-third the card’s width away from the handle side of the carding cloth. Continue loading small handfuls of fiber across the width of the carder.

Step 2. Hold the empty carder in your dominant hand and the loaded carder in your other hand, grasping the handle close to the bed of the carder. You can stabilize it with your first and middle fingers. Bring the empty card down to meet the tips of the fibers sticking out from the edge of the loaded card until the pins grab some of the fibers. Flip the empty card up at a 90-degree angle and pull slightly upward, transferring a portion of the fiber from the card you loaded to the working card.

Step 3. Bring the card to the fiber again, this time placing it slightly closer to the back edge of the loaded handcard, and repeat the motion of step 2.

Step 4. Continue to work the top card over the loaded card, moving gradually closer to the back edge and flipping to a 90-degree angle until you have moved all of the fiber from the bottom card to the top card.

Step 5. At this point, you can switch hands if you like, or you can repeat the same movement in reverse, using the bottom card to grab the fibers from the upper card.

Using Flat-Backed Cards

Step 1. When you use a flat-backed carder, your motion with the top card (the one you’re transferring the fiber to) should be more of a smooth drag, rather than a flip. Although you should avoid grinding the carding pins together, you will hear a bit of a scraping as you go through the transfer process. Only about half the fiber will be transferred with this method.

Step 2. When half the fibers are moved to the originally empty card, a process called stripping is used to move the remaining fibers.

Step 3. To strip the fibers from one card to the other, place the front of the card to be stripped against the pins on the handle side of the card that is to receive the fibers (a). Next, move the card being stripped in a downward motion, placing the web of fibers onto the newly charged card (b).

Card the fibers again and then strip the opposite card. You can also use this method on curved-back cards, if desired.

How to Make a Traditional Rolag

After you’ve opened up the fibers with your handcards, you can remove the fiber for spinning. The most customary end product of handcarding is when the fibers are rolled from end to end to form what is known as a rolag. To get a true woolen yarn, prepare a traditional rolag in this way. The cylindrical shape of the rolag causes the fibers to remain in a somewhat circular pattern as the twist enters the fiber supply. The yarn you prepare and spin this way will have the best insulating qualities of yarns spun by any of the other methods described here.

Step 1. Position the carder with the handle toward your body. Starting with the ends that hang off the edge of the carder, roll the fibers toward the card and continue to roll them as you remove fibers from the pins little by little. You can do this with your fingers, the edge of your hand, or the edge of the other handcard.

Step 2. If you have curved-back cards, you can lay the newly formed rolag on the back of one of the cards and roll it between the two cards to compact the fibers and help them stick together. Lay the finished rolags in a basket or other container until you are ready to spin them.

The Fiber-Cigar Option

If you prefer to preserve fiber alignment, instead of the true woolen-yarn qualities that you get by spinning rolags, you can form what is known as a fiber cigar. With the cigar shape, you can spin a yarn that is a bit smoother than one spun from a rolag, because you are spinning from the tips and butts of the fibers, rather than from the cylindrical rolag.

To create the cigar, remove the small carded batt from the pins of the card and roll it starting at one side edge so that the fibers are lengthwise and parallel on the “cigar,” to create a very short is fattest in the middle. If you wish, you can draw it out somewhat to make it a consistent thickness that is easier to spin from.

How to Spin off the Card

If you are carding fibers that are a bit short for combs but you really want to preserve their alignment, spinning off the card may be the answer. This technique mimics the effect you get by flicking and then spinning from the lock. Because you are allowing short lengths to remain in the fiber bundle, along with any neps or noils contained in the wool, yarn spun using this method doesn’t resemble the organized, smooth yarn you get from combing, but it’s a good second choice.

Step 1. Hold the carded, still-loaded handcard with the front edge facing the orifice of your spinning wheel, and attach the fibers from one end of the card to a leader.

Step 2. Begin to spin, working your way along the front edge of the card until most of the fibers have been removed. Some fibers will remain in the bed of the card and may not have been spun. Don’t clean those fibers from the bed; just reload the card and handcard as usual for the next batch. These fibers will be carded in and join the next group to be spun.

How to Make Your Own Roving

This is a great way to blend different fibers and different colors, as well as make longer lengths of fiber to spin. I like the way it allows me to blend several colors together to achieve a sort of striation or long stripes of several colors together along the length of the roving. For a consistent roving, weigh the first set of batts, and then load the handcards with the same amount of fiber for each subsequent set of batts.

Step 1. Card your fibers as described for either curved-back or flat-back carders (see My Favorite Method with Curved-Back Handcards and Using Flat-Backed Cards). Remove the batt from the bed of the handcard, keeping it flat (don’t form a rolag or cigar). Lay it aside.

Step 2. Make five to seven of these batts, and stack them one on top of the other. (Five or six batts are comfortable for me to hold, but spinners with larger hands may be able to manage more.)

Step 3. Holding the rectangular stack in your hand, begin to draw out fiber from the side (perpendicular to the length of the fibers). Whether you are blending colors or fibers, try to balance the amount of each color or type of fleece as you draw the fibers out. To ensure that you’ll have plenty of air and control when you spin from your roving, take care to keep your roving a pretty consistent thickness, generally no thinner than 2 inches thick. Make a second pass, if necessary, to even out what you’ve made or if you want it to be thinner.

Step 4. Spin the roving as you complete it, or wind it into a loose “bird’s nest,” adding a little twist to the fiber as you wind to help keep the fibers in place, and put it aside to spin later.

Drumcarders

Although I didn’t make any of the samples in this book from fleece processed in a drumcarder, it is an excellent option for any spinner who likes spinning from carded fibers. It’s not necessarily a faster option. With practice, using handcards can be just as fast as using a drumcarder. Once you develop some drumcarding skills, however, there’s nothing much prettier than a beautifully smooth batt fresh off a drumcarder.

You can use the drumcarded fibers in much the same way you work with those from handcards. The drumcarder aligns the fibers as you feed them in, and then you can remove the drumcarded batt in several different ways to get different end results in your yarns: fine or bulky, cool or insulating, and thin or fat.

Less Is Better. A secret to properly done drumcarding is that more is not better. This secret also applies to every other wool- method: More on handcards, more on combs, more in the hand for flicking, or more on the drum does not result in faster processing. Please learn from my mistakes! I confess to still getting drawn into thinking I can get just one more layer on that drum. If I give in to this temptation, however, what always happens in the end is that I need to make additional passes no matter what tool I am using, and additional passes just slow me down.

Dos and Don’ts of Drumcarding

- Feed only small amounts of fiber at a time. Too much fiber will get caught between the licker-in and the main drum and make it difficult, if not impossible, to turn the handle. It also encourages the incoming fibers to wrap around the licker-in, resulting in more waste than necessary.

- Turn the handle slowly as you feed in the fibers. Turning the handle too fast, especially when you’re working with fine fibers, causes neps to form in the developing batt. This is because one end of the fiber is attached to the main drum while the other is attached to the licker-in. When you turn the handle fast, you cause the fiber to snap, and the spring in the crimp causes it to ball up.

- Do not hold back on the fibers as you feed them in. It’s okay to hold them lightly for a bit of control, but let them feed as they like. This helps limit the amount of fiber that wraps around the licker-in. It also helps avoid stretching the fibers, and thus cuts down on neps that can develop during the process.

- If you see fibers beginning to wrap onto the licker-in, use your fingers or a nail brush to sweep those fibers up and onto the main drum. This, too, cuts down on fiber waste.

Using a Drumcarder

Preparation is key to good results. By this I mean that you should never just take some washed fleece and throw it at the carder and expect a good output.

Step 1. Open up all the locks using a flick or a comb. You can also use a teasing tool, a device that is covered with carding cloth and comes with some drumcarders. To use it, clamp the tool to a table, and then draw the locks through the pins to open them up. No matter what tool you use, take care to completely open both tips and butts of the locks so they are no longer matted or stuck together. For more tips on getting good results with a drumcarder, see Dos and Don’ts of Drumcarding above.

Step 2. Put your fiber through the carder in small amounts at a time. You should be able to see the tray of the carder through the fiber you are putting on.

Step 3. Stop adding fiber just before the fiber fills the carding cloth teeth. Keep in mind that less is better and will result in smoother batts.

Step 4. Remove the batt from the carder. Separate the batt by running the batt pick (also called a doffer pin) under the fiber along the slot in the large drum. Gathering together the fiber coming from the back of the drum in your hand, pull the batt from the drum. The batt should come off following the direction the carding cloth pins bend.

Step 5. If necessary, separate the batt into several lengths and repeat steps 2 through 4 until the fibers are all open, or are as blended as you desire.

Preparing to Spin Drumcarded Fibers

Once you have your drumcarded batt, you have several options to prepare it for spinning. Each method affects the yarn you spin from it, so it’s important to sample to make sure you can get the yarn you want.

Option 1. For an effect similar to what you get from a handcarded rolag, just roll the drumcarded batt crosswise, and attenuate it into something similar to an extra-long rolag. The difference between a rolled drumcarded batt and a handcarded rolag is that the fibers are drawn out and thus are more parallel in the drumcarded batt, and the yarn will therefore have a bit less of a woolen look.

Option 2. Roll the batt so the fibers are lengthwise, and then attenuate it as you did for handcarded roving (see How to Make Your Own Roving).

Option 3. Split the batt lengthwise into several parallel, long strips.

Option 4. Strip the batt in a zigzag fashion to make one long strip of roving.

Option 5. Make a roving right off the drumcarder by using a diz. Here’s how: Instead of removing the finished batt in one piece, lift just a small width (an inch or less) from the drum, and thread it through a hole on your diz. Pull the fiber off the drum through the diz little by little, sliding the diz back in increments to keep the width consistent. With this technique, you remove the batt all in one piece and end up with a long strip of roving ready to spin.

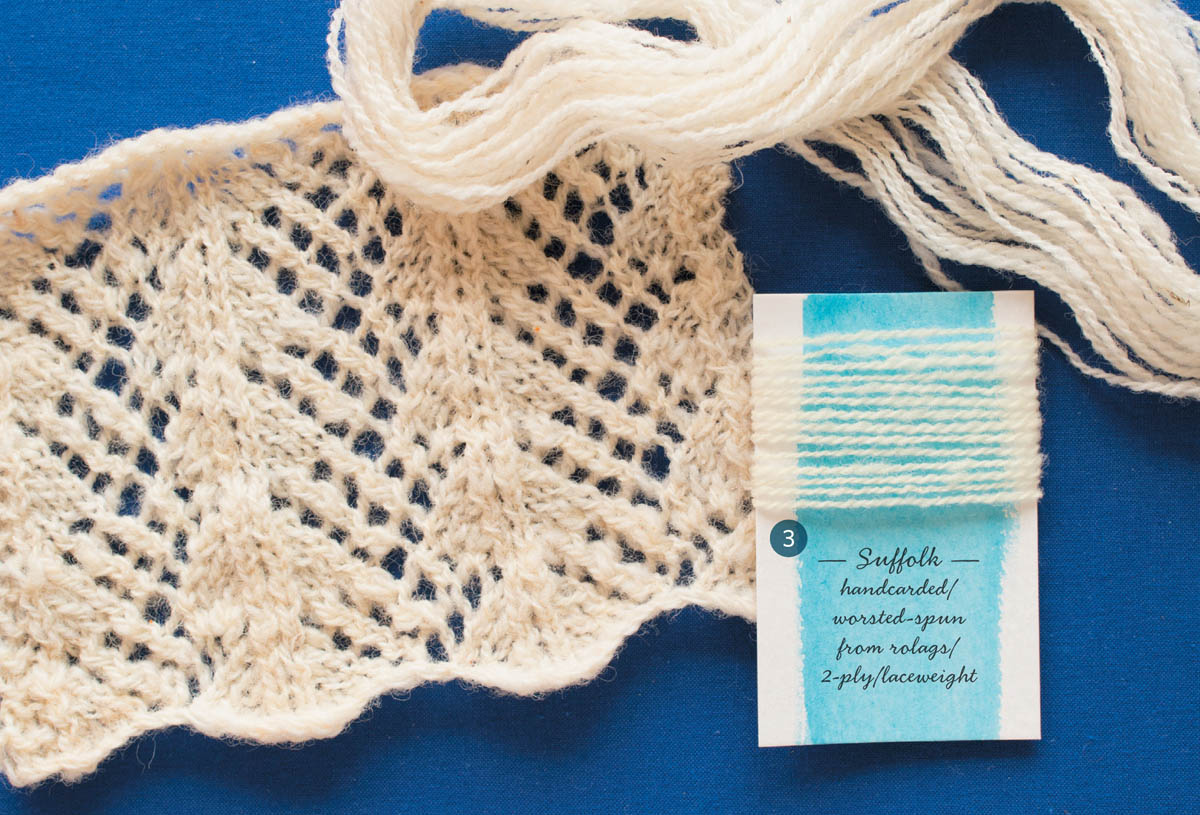

Suffolk

Suffolk sheep were developed in the 1700s and recognized as a breed by 1810. Their heritage is Southdown crossed with the Old-Style Norfolk Horn. The outcome of this long-ago crossing is a fast-growing sheep that is great for market lamb production. The Suffolk breed didn’t land in the eastern United States until 1888 and didn’t see the western side of the country until 1919. Today, however, it is the most common sheep breed in North America.

Like the fleece from most of the other Downs and Down-type sheep, Suffolk wool has been overlooked, and available fleeces are generally very dirty, with tons of VM. If you happen upon a shepherd who’s interested in wool production, grab one of these fleeces to cut down on your work, because the chances are good that there will be less VM in it than in the fleeces of sheep raised only for meat. If you want to try Suffolk no matter what, go ahead. The yarns from this breed are bouncy, airy, and lightweight, while maintaining warmth and durability.

Suffolks are not small sheep; they rival Lincolns in size and weight. Mature rams weigh anywhere from 250 to 350 pounds; ewe weights vary from 180 to 250 pounds. The fleece from a mature ewe weighs between 4 and 8 pounds, with a yield of 50 to 62 percent after skirting and scouring.

The fiber diameter of a Suffolk is between 25 and 33 microns. The staple length ranges from 2 to 31⁄2 inches. These shorter-stapled fibers ask for a bit more twist to hold them together, in order to ensure less pilling and longer wear. The problem is that too much twist equals a harsh yarn. Sampling is your friend once again. Use different spinning techniques to make a few swatches to help you get where you want to go with a lot less wasted time and fiber.

Sampling Suffolk

Suffolk is a surprise to many spinners who expect a harsh hand in this wool, but then discover it is quite often the opposite. Though these yarns wouldn’t necessarily be thought of as soft, I wouldn’t hesitate to use these sturdy-feeling yarns for a jacket or cardigan that I’d wear next to my neck.

1. & 2. 2- and 3-ply woolen-spun. I spun both the 2-ply and the 3-ply woolen-spun yarns from rolags. These yarns are both stretchy and cushiony. The 3-ply (2) is definitely firmer than the other, and the yarn I used for the knit swatch would make a great cardigan that would last for years. The 2-ply yarn (1) for the other knit swatch is finer and would make a nice warm garment without adding much bulk. I used the same 2-ply yarn for the woven swatch, which has a good amount of body. Yardage made of this yarn would work for a very warm jacket with a collar that stays in place. While it might not make that scarf with great drape that you dream of, it has excellent insulating properties and would guard against the cold.

Worsted-spun. After spinning the purely woolen yarns, I was quite happy with the way they felt and looked. I then carded some more of the Suffolk fiber into rolags, which I spun using a worsted drafting method. Though this yarn is attractive, it feels quite a bit firmer and much less elastic, even though I was careful to avoid adding more twist than I put into the woolen-spun samples.

3. Laceweight. Lace is not the thing I think of when choosing Down-type wools for spinning. This lace sample is in some ways surprising, and in other ways it did exactly what I imagined. The surprise is that the lace is more open than I expected; because of the bounciness of the yarn, I thought the holes would want to collapse on themselves. The fabric has a lot of body, and so if you are looking for a lace fabric that maintains shape, rather than offering drape, when used in a garment, this might be the best fiber choice. The yarn is somewhat firm, but it is not scratchy.

My Suffolk samples show me exactly what I’d like to use these yarns for and where they will work best. For instance, a worsted-spun sample might do very well if it were spun from the end of the card, rather than from a rolag. I’d also like to experiment more with twist: Should I use less or more twist in a finer 3-ply yarn to achieve the perfect recipe for socks? I’m imagining how I would spin Suffolk yarn for a fine-woven fabric for an A-line skirt that would be extremely warm and comfortable for winter. Also, combing Suffolk makes a beautiful yarn. How might I use that? A study of Suffolk alone could take months and months before I would exhaust all of the prep, spinning, and fabric options. With all of these possibilities, if you are hesitant to try out Downs and Down-type breeds, Suffolk might be a great place to get your feet wet.

Why Not Suffolk Yarn for Lace?

Several characteristics of Down-type yarns argue against using them for lace: Thicker spots in these yarns seem to be amplified after washing, probably due to the fantastic, spiral-shaped crimp structure, which causes the fibers to push away from each other. If the twist isn’t consistent or the draft was longer or shorter in one spot, it will be obvious after you wash the yarn. In addition, drape is not the strong point of Suffolk yarns, and drape is something we generally look for in lace. Because you have so many options in other wools, I would avoid knitting lace with Down-type fleece for that reason alone.

On the other hand, it’s critical that the lace pattern be obvious in the knitted fabric. There is nothing more disappointing than spending a lot of time on a project only to discover that the structure and pattern you worked in, regardless of whether you are knitting, crocheting, or weaving or working some other fiber project, disappears because of the structure of the yarn you used. For a lace project that calls for more stability and structure, this wool might be a great choice.

Southdown

You could fill an entire book with all there is to say about the breed history and usefulness of Southdown sheep. Southdowns are the progenitors of all the other Down breeds. The original Southdowns were small bodied and raised for both wool and meat. Records from medieval times include descriptions of sheep that resemble these old-style Southdowns. These small sheep were crossed and selected to develop a larger, more marketable sheep, which is the standard Southdown sheep we see today. The smaller sheep that are much like the original Southdowns are called Babydoll Southdowns or Olde English Southdowns; an even smaller sheep, the Miniature Southdown, is less than 24 inches tall. Babydoll and Miniature Southdowns are currently raised as pets as well as for wool.

Records indicate that Southdown sheep were first brought to the United States from England in 1640 with the Puritan migration, and they were again imported in the early 1800s. Southdown fleeces can now be a bit difficult to find in the United States, however, as other, larger breeds have become more marketable and profitable than even standard Southdowns. The breed has been on the conservancy list of The Livestock Conservancy for some time but has been upgraded to a recovering breed as of 2012. This is great news because, if things continue in this direction, it won’t have to be on the list at all.

The wool of Southdown sheep is short, ranging from 11⁄2 to 4 inches, with most locks in the 2- to 3-inch range. Fiber diameter ranges from 23 to 31 microns. The fleeces are soft and bouncy with lots of crimp and loft. Because the fibers are so short, you may experience a lot of loss if you comb them, and the fibers may be difficult to flick. Carding is usually the best bet for these fibers.

When you look for a Southdown fleece, look for one low in VM and with few second cuts. Because you’ll be carding this wool, any second cuts and VM will get blended into the fleece when you card. I carded the wool for all of the samples below; although I attempted to remove the second cuts before carding, I was unsuccessful at removing all of them, and so the yarns spun from my carded rolags are extremely textured.

Sampling Southdown

I should point out that not all Southdown should be judged by the samples shown here. Several times while I was spinning my samples for this section, I was tempted to abandon them and search for a different fleece. The fleece I chose had an abundance of second cuts and a staple length of 2 inches or less over the entire fleece. Before washing, the lock length was about 21⁄2 inches, but the fineness of the fibers caused it to shrink a little when scoured. This wasn’t due to any felting; it was just that, as the grease and dirt fell away, the fibers were released to do as they wished.

I persevered, however, and decided to go ahead with my samples, because I wanted to show that even not-so-nice fleece can be used for wonderful, utilitarian clothing. I also wanted to include yarns that aren’t so great to demonstrate that sometimes, no matter what your skill level, the fiber dictates the final yarn, and no matter what you do, it will not become a smooth, consistent thread. If the project calls for smoothness and consistency, look for a different fleece, and dedicate the unruly one to a project that will work with that yarn. And don’t give up on one bad experience with a particular breed, because one fleece may not be a good representative of the entire breed. I’ve spun wonderful Southdown that is fabulous and has done everything I’ve wanted it to.

1. 3-ply woolen-spun from rolags. I spun the yarn from handcarded rolags, then plied it to 3-ply. It has a nice amount of elasticity, and the 3 plies help to even out the singles. Although the plied yarn contains some of the texture that was in the original singles, this gives the swatch a rustic look that can be attractive in some projects. Though medium to soft in feel, the hand of the fabric isn’t prickly, and it feels as if it would stand up to lots of use. Because of the short fiber lengths, some pills began to form with about a minute of abrasion.

2. 2-ply woolen-spun from rolags. Sample 2 is a 2-ply yarn, made from the same singles as sample 1. This yarn, too, has a nice amount of springiness, and the knitted swatch is a bit more supple than the one worked with sample 1. The fabric seems perfect for a sweater, as it feels a little less dense than the 3-ply swatch, though I know that this yarn will pill even more readily than the other, because 2-ply yarns lock in fewer of those ends that stick out and become the pills we see on our clothing.

3. 2-ply worsted-spun off the card. For the knitted lace swatch, I spun off the card with a worsted-style draft. Although the yarn is a bit smoother than the ones I spun from rolags, the second cuts and short fiber length still contributed to texture and lumps along the length of the yarn. But spinning off the card helped reduce the number of second cuts finding their way into my yarn, since most of them stayed in the pins of the card. I spun the singles somewhat finely, at about 20 wraps per inch, but after plying, the yarn plumped up and the crimp went back into place and the final yarn became much thicker. This is not a yarn I would generally choose for a lace project, since its inconsistencies are even more visible near the empty spaces in the lace, but I can see how this might be a good choice for a heavier shawl with a more unpolished look. It’s a matter of fitting the yarn to the right project.

Minimizing Neps

The problems caused by second cuts in these short Southdown fibers can be exacerbated by their fineness and springy crimp, which can result in a lot of neps in the rolag if the fibers are overcarded. With fibers this fine and springy, I try to keep my carding down to one or two passes.

Dorset Horn and Poll Dorset

Dorset Horn and Poll Dorset sheep are almost identical except for the horns part. All Dorset Horn sheep, both male and female, have horns, which curl or curve forward toward their faces; Poll Dorset sheep have no horns. The wool of these two breeds is pretty much indistinguishable. Some say Poll Dorsets aren’t as hardy or intelligent as Dorset Horns. In the background of both breeds is a cross between Spanish sheep and native English stock from the 1500s. In Australia, the Poll Dorset was developed by crossing Corriedale and Ryeland sheep and then crossing the lambs from this cross with a Dorset Horn sheep. The resulting Poll lambs were then crossed with Dorset Horn ewes. Those Poll lambs were crossed again with the Purebred Dorset Horn ewes so that a sheep with near 100% Dorset blood was accomplished with all of the Dorset Horn characteristics except for the horns. Meanwhile, in the United States at around the same time, the Poll version of this Dorset breed was being developed just by selecting for a horn-free mutation in a flock in North Carolina.

Dorset Horns were one of the very earliest sheep to have a breed registry; begun in 1892, the society was surely helped to grow by its first patroness, Queen Victoria. In 1890, Dorset Horns were imported to the United States’ West Coast. In the 1950s, the Poll Dorset emerged in Australia. The Poll Dorset now well outnumbers its Dorset Horn cousins in England, Australia, and the United States, and Dorset Horns are actually now on the endangered sheep lists in both Britain and the United States.

These sheep are very easy to raise in a wide variety of climates and elevations. They can be bred year-round and may have three births in a two-year time span, making them attractive to shepherds interested in meat production. (Most other sheep breeds have the ability to lamb only once a year, in the spring.)

Sampling Dorset Horns and Poll Dorsets

For these samples, I used wool from the horned version of Dorset, though this breed is on The Livestock Conservancy list as of 2013, and so the Poll Dorset may be more easily acquired for spinning. I used handcards for all of the samples shown here, but treated the carded wool differently in each case.

1. & 2. 2-ply spun with a short forward draw. By spinning these two samples with a short forward draw, I created a yarn that is somewhat worsted. I spun the one below right off the card, so the fibers are all aligned. This yarn is smooth and only slightly elastic. Because the yarn has a hard feeling, the knitted swatch I made with it is a fabric that would be great for outerwear or other hard-wearing items. I spent a little time rubbing the fabric, and no pills formed from the abrasion. This is a great fabric, but I wouldn’t want it next to my skin. I spun the other worsted-spun sample opposite from fiber cigars (see How to Make a Traditional Rolag), so in this yarn, too, the fibers are mostly aligned. The yarn feels very similar to the first. I wove a swatch with this yarn and can imagine a skirt or jacket made with this fabric.

Spinning these two 2-ply yarns with less twist in the singles would surely have made them softer, but because this would also have made them less hardy, they would have pilled more easily. My goal for worsted-spun Down yarns is strength and durability, which is reduced when you give the yarns less twist.

3. 2-ply spun with a supported long draw. This yarn is the most traditional: I handcarded the wool, then removed the batt from the carder as a rolag, which I spun from the end. This sample is the complete opposite of the worsted-spun samples. It is soft and has drape, though some body remains in the sample. The thick-and-thin spots in the singles are mostly hidden in the swatch knit with the 2-ply yarn, but I think a 3-ply would have been even better. The knitted swatch is very resilient, and would make a great fabric for a cardigan. Within a short time of rubbing, my abrasion test showed some fibers pulling out, which will form pills. Though this yarn has a similar amount of twist as the worsted-drafted samples, the difference in durability is very obvious.

4. Yarn spun from handmade roving. This yarn is sort of a middle ground between the true woolen sample that was spun with a woolen draft from a rolag and the samples that were spun as worsted from carded fibers. This sample stands up a bit better to the abrasion test, and the yarn is airy and lofty. Though I love the swatch spun from rolags with a supported long draw, this sample might be a good compromise. I stacked carded fibers, pulled them into a roving, and then spun them using a supported long draw. The yarn, even spun with the same whorl and twist, is not as soft as the version spun from rolags, possibly because the latter’s fibers spiral into the forming yarn, thus trapping more air than happens with the drawn-out, somewhat-aligned fibers of a roving.

Black Welsh Mountain

Black Welsh Mountain is a dual-purpose breed with a true black fleece, which can be very difficult to find. Although the tips may get a bit bleached by the sun and turn to a slightly reddish color, the fleece is truly black, not dark brown. Breeds with only white wool are generally the most sought after in the wool industry, because white wool, which can be dyed any color, is more versatile in the garment and other industries that use wool. Black, on the other hand, is always black. Because of this, black lambs of many breeds are usually culled, so their black-wool genetics don’t contaminate future generations, and so their wool does not contaminate the entire clip during shearing. But Black Welsh Mountains are prized for their black fleece. The wool is great for blending with other natural colors to obtain shading, and as it is a true black, it doesn’t need to be dyed when you want black cloth.

The direct ancestors of Black Welsh Mountain sheep are the Welsh Mountain, or White Welsh Mountain, breed. Black Welsh Mountains were developed from this breed by selecting for color over time, until these black sheep were eventually recognized as their own breed. Although the breed description doesn’t specify height, most of them are small, about 30 inches tall at the shoulder.

The texture of the adult sheep’s wool is medium to coarse, but lamb fleeces can be quite soft, suitable for next-to-skin wear. Staple length is generally 2 to 4 inches, with fleeces weighing between 21⁄2 and 51⁄2 pounds. The fiber diameter ranges between 28 and 36 microns. The range is very similar to that of the Suffolks, though I found the carded Black Welsh to be crisper feeling than Suffolk wool.

As is typical of Down-type wools, the crimp is generally difficult to see in the locks, but the fleece has bounce and extreme loft, though my samples didn’t have as much elasticity as I found in other Down-type breeds. The wool is dense, with blocky locks that are hard to distinguish from one another, but it almost always has less kemp than what you find in its ancestors, the White Welsh Mountain. Because the fleece is fairly low in grease content, it’s very easy to scour. The staple length is on the shorter side, but if you find a fleece with longer locks, you can comb it, if you wish. It can be used for household goods, including carpets, but it is soft enough for clothing as well. In spite of its crispness in comparison with some others in this category, I found myself spinning a wide variety of samples with it.

Sampling Black Welsh Mountain

1. & 2. 3-ply spun from rolags. These are the samples that I would consider the most conventionally spun, or, in other words, spun taking the approach I would consider most likely to work best with this wool. Both of these 3-ply yarns were carded, made into rolags, and then spun using a supported long draw. The only difference between them is the thickness of the singles. Sample 1, knit with the finer singles, is a denser fabric. The yarn, though not harsh feeling, also feels denser. A rub test on the corner of the swatch indicates that this fabric will last a long time. Although it’s not a fabric I’d choose for a cuddly sweater, I could see it used for great boot socks or a nice, lighter-weight work sweater. Sample 2, made with the thicker singles, is much bouncier, and the knit swatch also has a lot more bounce than the other. I can see a basic pullover out of this yarn to be worn over another shirt for winter wear. This fabric did show a bit of wear when I rubbed the corner of it, but its warmth is unmistakable.

When I was spinning these yarns, I was not in love with the fiber, perhaps because I spun it immediately after working with one of the finer wools. When I knit the yarns into swatches, however, the yarns were transformed, and I could see why this wool was developed.

3. 2-ply spun from stacked handcarded batts. For these yarns, I handcarded the wool, which I removed from the cards without rolling and then stacked, so that I could pull the fleece out from the side to make roving (for more about this carding method, How to Make Your Own Roving). I rarely stack more than five or six batts when I use this technique.

When the batts were the thickness I wanted, I spun them in a worsted manner and made a 2-ply yarn with the singles. I find it a bit more difficult to get a consistent yarn using this method than when spinning supported long draw from rolags, but both the yarn and knitted fabric are somewhat softer. This yarn, as well as the two yarns just discussed, would make a good woven fabric for a warm winter coat.

4. 2-ply spun from fiber cigars. For this sample, I handcarded the fleece and then formed each batt into a fiber cigar by rolling it opposite to the way I’d make a rolag (see How to Make a Traditional Rolag). This approach keeps the fibers pretty well lined up. I spun the cigars with a short forward draw. The kemp in my sample was trapped and compacted with the rest of the fibers, resulting in a yarn that turned out to be a bit harsh; in fact, the swatch I wove with it feels like burlap. (I didn’t make a knitted swatch.) Although it’s not a yarn I’d want to use for clothing, it could make a great shopping bag or carpeting.

5. 2-ply spun from the end of a card. For sample 5, I again handcarded the wool, but this time I spun the fibers right off the end of the card and then made a 2-ply yarn. Lots of the kemp stayed in the pins of the card, and even more came off as I spun. Since I used a drafting method very close to short forward draw, I expected a yarn more similar to the one I spun from fiber cigars. Instead, the yarn is a bit softer and would be just fine for use in both woven and knit garments. Although, as I’ve said before, Down-type fibers wouldn’t be my first choice for a lace project, I’m very happy with the lace swatch below. The holes of the lace remain open, making the lace pattern easy to see. The fabric has plenty of body, and though it wouldn’t drape in the same way some lace patterns require, the yarn would make a great sweater with a lace design worked into it.

6. Combed Black Welsh Mountain yarn. I couldn’t resist trying combs on this fiber and sharing the results, even though combs aren’t the focus of this section. I spun the fiber right off the comb using a worsted draw, which removed almost all the kemp and made it much easier to spin a fine yarn. I wish you could all feel this sample. (You can, if you make one for yourself!) Both the yarn and the lace fabric I made with it feel almost silky. In the knitted swatch, you can see that the lace pattern is open and quite visible. It’s hard to believe that this yarn and swatch are from the same fleece as the swatch I made from the worsted-spun fiber cigar above. I am so excited about these samples that I have big plans to hunt down a fleece so that I can spin some yarn like this to make a sweater for myself.

The wide range of fiber diameters available from this breed means that it’s possible to find a natural black fleece for any project you might want. And as you can see from my experiments (which were not at all exhaustive), you should be easily able to find a prep and spinning method to suit the outcome you desire.