![]()

RE-TEAM AUDREY, BILL, AND BILLY WILDER?

Jennings Lang was a big fan of Wilder’s. He had signed the director, now in his seventies, to a deal with Universal. The first film had been Wilder’s disappointing remake of The Front Page, and when Wilder came to New York to promote it, Audrey’s name came up. At a luncheon for the foreign press, he was asked by reporters whether he would be working with her again. “Everyone still wants to work with her, including me,” he replied. “She’s the one who doesn’t want to work. Being a mommy is her current career!”

Tom Tryon had written a best-selling novel about Hollywood, Crowned Heads, and one of its stories, “Fedora,” was slated to become Wilder’s next Universal film. It wasn’t, as columnists joked, the story of a hat. The title was the name of a mysterious, Garbo-like actress, and the plot had overtones of Sunset Boulevard and other films about Hollywood, with a bizarre mother-daughter twist.

Bill Holden would be playing the male lead. He was hot again, and when casting suggestions were tossed around for the title role, absurd as it may have seemed, Audrey’s name came up. Hepburn’s persona was not remotely Garbo-like, but then again, when the studio produced Gable and Lombard in 1976, their initial choice for the role of the shimmering, blonde, legendary Carole Lombard was the black-haired, absolutely nothing-like-Lombard, quintessential rock-and-roller Cher (Jill Clayburgh got the part).

The resurgence of interest in Bill Holden was not the result of any great drive on his part to recapture his former glory. He simply wanted to work, and he had scored several successes—on television, in the police drama The Blue Knight; on the big screen in The Towering Inferno, which he loathed. He’d had to take third billing and resented the attention, and the screen time, lavished on top-billed Paul Newman and Steve McQueen. Not to mention that Jennifer Jones, with whom Bill had scored a tremendous success two decades earlier in Love Is a Many Splendored Thing—was relegated to below-the-title status. Faye Dunaway had the female star part.

But Bill was happy to be in a blockbuster, and they’d met his price of $750,000. It had been a long time. He had scored a major critical triumph, along with Faye Dunaway, in the highly acclaimed Paddy Chayevsky–Sidney Lumet film Network. With nonalcoholic vigor, Holden memorably portrayed an angry, aging television executive, and the performance won him an Oscar nomination as Best Actor. Top-billed Dunaway won the Oscar for Best Actress, and Peter Finch, posthumously, for Best Actor. Holden and Finch, also a heavy drinker, had become good friends, as had Holden and Chayevsky.

Director Lumet had cast Holden because of “the look of sadness on his face.” Dunaway later said he had brought “a crusty elegance” to the role, “a perfect combination of street smarts and schooled intellect.”

Bill had built himself a beautiful home in Palm Springs, sitting on two-and-a-half acres, in the gated Southridge community. It was an 8,000-square-foot desert retreat with wonderful views, high ceilings, and floor-to-ceiling windows. The master bedroom suite boasted two fireplaces, a walk-in closet thirty-six feet long, a sunken terrazzo spa tub, and an indoor-outdoor shower. The house had four bedrooms, four-plus baths, a guest suite, a wood-paneled media room, and a gym. An infinity pool was cantilevered over boulders. The estate rivaled Sinatra’s Palm Springs compound, and Bill could never complain that he wasn’t living well.

His personal life seemed to have settled into something stable and satisfying. He’d been sober for three years. Pat Stauffer had remained an important presence in his life, and he would even deliver the eulogy at her father’s funeral. But All-American Bill seemed to conduct his private life in very European-like fashion, not unlike Mel Ferrer and Andrea Dotti. He met and fell in love with actress Stefanie Powers, née Stefanie Zofya Paul, a beautiful young brunette with an adventurous spirit. To experience again the first blush of true love was a feeling Bill was not about to deny himself. When they met, Powers was at a low ebb emotionally, having just divorced her husband, actor Gary Lockwood. Bill understood. He was an old-school gentleman, with his great charm intact, and she credited him with making her “feel like a human being again.”

For Bill, with Stefanie, there was a different dynamic in play. “Most of my life I’ve had to take care of people,” he said, “but when I’m with Stef, I haven’t had to do anything.” In fact, she protected him. She appreciated his self-deprecating humor and sense of fun; Bill still drove a motorcycle, and she was often a backseat passenger.

“We were soul mates,” she said. They came into each other’s lives at exactly the right moment. “I’ve never had a relationship so fulfilling,” he said. If Audrey heard about those comments, she was long past taking them personally; hadn’t he said similar things about her and Grace Kelly more than twenty-five years earlier? But Capucine and Pat Stauffer’s feelings must have been hurt on hearing Bill express those sentiments.

Powers, at thirty-two, was twenty-four years Holden’s junior. There was a physical resemblance to the younger Audrey, and like Audrey, Stefanie was devoted to her mother. She was an outdoors girl, and she loved to travel; the serenity and allure of exotic locales appealed to her. But on her travels with Bill, the couple didn’t spend time seeking out wonderful restaurants. They preferred to explore the territories they visited, and to understand their people and customs.

Bill introduced Stefanie to his great passion: Africa, and wildlife preservation. “Bill was an environmentalist before the word had been invented,” she noted, pointing out: “He was a very interesting man. There was much more to him than the fact that he was ‘a big movie star.’” Virtually no woman in Bill’s life ever complained that one of his shortcomings was being impressed with who he was. Perhaps he would have been better off if he had been impressed with who he was, and with what he had accomplished. Not appreciating the quality of his work was a trait he shared with Audrey—the irony was how hard they’d both worked to create their performances.

The young male stars of the 1970s were not strangers to Holden’s films. Jack Nicholson, visiting a friend one afternoon at Cedars of Lebanon Hospital in Hollywood, spotted a Mercedes in the parking lot. It was the exact model he was planning to buy. He walked over for a closer look—a man was trying to locate something in the back seat. Nicholson tapped on the window. The two men immediately recognized one another, exchanging a friendly, “Oh, hi!” It turned out that Holden was a longtime idol of Nicholson’s. He asked Bill how he liked the car, which the older actor recommended enthusiastically. “I’ve tried them all,” said Bill, “Rolls-Royce, Bentley, Jaguar.” Nicholson asked Holden why he was at Cedars. “Oh, I’m going in for a two-day drying out period,” he replied, locating at last the six-pack of beer he’d been searching for in the backseat. “Come up to my room and we’ll talk,” said Bill, and they did, for quite a long time. The men rarely encountered one another afterward, but when they did they felt like “old friends.”

John Belushi was a big Holden fan. They encountered each other at the well-known La Costa Resort, located just north of San Diego in Carlsbad, California. Bill and Belushi were there for the same purpose—to dry out.

Bill, almost thirty years Belushi’s senior, was the voice of experience when he warned the younger star, whose film, Animal House, was proving to be a big hit but whose problems with substance abuse had made headlines, to expect the press to keep him in their sights. “They’ll be good to you when you’re on top,” he told Belushi. “But if you start to slip a little, they’ll try to tear you down.”

![]()

Bill and Stefanie maintained separate homes, and he was not uncomfortable referring to Powers as the woman he lived with. “Marriage? Why spoil things?” he said. Stefanie was a positive influence on him, and he was grateful. Later, when he did propose marriage, she turned him down. He was drinking again, and the unpredictable, irrational behavior had returned. Rumor had it that he’d held a gun to his head for an hour and a half when she told him she wouldn’t marry him.

When reporter Bernard Drew bluntly asked Holden, “Why all the drinking?” Holden replied: “Let’s just say inner turmoil.” When drunk, Bill’s behavior was so erratic that when the Reagans occupied the White House, the first couple of the land thought it best not to invite their old friend to any official functions. It was anyone’s guess what he might do after he’d had one too many, and he knew it. For that reason, he turned down an invitation to Reagan’s inauguration.

At one point, Bill owned a pet snake, “Bertie,” that sometimes coiled itself around him; on one occasion, when Bertie couldn’t be found, Bill’s houseguests, Helen and Marty Rackin, said they’d have to leave if Bertie wasn’t located (he was). “Yes, Bill could be eccentric, but he was always a likable, persuasive, intelligent guy,” noted his pal, actor Cliff Robertson. “The lions and tigers couldn’t have had a better advocate.”

![]()

What became of the possibility of re-teaming Hepburn, Holden, and Wilder? Audrey would have been very expensive; and, remembering the fiasco of Paris When It Sizzles, it was highly unlikely she would have the remotest interest in working with Bill ever again, although Billy Wilder would have been welcome.

How about Elizabeth Taylor for the part? Neither Bill nor Billy had ever worked with Elizabeth. “Have you seen her lately?” was Jennings Lang’s reply (Taylor was forty-six; she’d put on weight, loved her martinis, and had become difficult to photograph—no close-ups until after lunch, when the puffiness in her face had subsided). Finally, a rising young foreign star, Marthe Keller, was cast. “Who?” asked Universal PR executive Paul Kamey, on learning of the choice; it was a reaction subsequently echoed by the American public, and a move Wilder deeply regretted. In the meantime, Universal withdrew from the project, and Wilder subsequently had a tough time securing financing and distribution. Holden had already slashed his salary so that Billy could get the picture made.

Back when Wilder had been in New York promoting Front Page, Audrey was on his mind. During lunch with a reporter at the Laurent Restaurant, he was asked if he planned on getting together with Gloria Swanson, who had an apartment in New York. Their classic Sunset Boulevard, with Bill Holden, was constantly shown on television, at film festivals, and in revival houses. It already had a huge cult following. Wilder said he’d try to see her, and noted, with a tinge of disbelief: “Do you realize that Audrey Hepburn today is close to the age Swanson was when she made Sunset Boulevard?”

Swanson had been forty-nine when she made the classic film. Audrey was soon to turn fifty.

![]()

He was urban, American, New York–gritty. And he was dark and sexy, very much Audrey’s type. The son of Italian immigrants (his parents were of Sicilian origin), Biagio Anthony Gazzarra—Ben Gazzara—said that discovering acting in his teen years growing up in the Kips Bay section of Manhattan rescued him from what might have been a life of crime. He attended City College of New York for two years, then dropped out to study acting, first with director Erwin Piscator at the New School, then the Actors Studio. Rex Reed later described him as “the Actors Studio crown prince” and made the point that in his characterizations, Gazzara “never hid behind mumbles and scratches,” as did many other Studio alumni.

Audrey was impressed that Ben had achieved success on the Broadway stage. He won wide acclaim for A Hatful of Rain, and he had created the role of Brick in Cat on a Hot Tin Roof. Later in life, Gazzara said he turned down many film offers in those early days. “I won’t tell you the pictures I turned down because you’ll say, ‘You are a fool,’ and I was a fool.” A sense of humor did reside in the seemingly ultraserious Gazzara. It surfaced during appearances he made on TV talk shows. And, like Mel, he had even appeared as a panelist on What’s My Line? A successful weekly TV drama series, Run for Your Life, brought him widespread recognition.

He was delighted to be Audrey’s leading man in Bloodline; he was not usually cast as a romantic lead. The film was based on Sidney Sheldon’s best-selling novel (in ads for the movie, the title would be explained: “The line between love and death is the Bloodline”). A crisis in Audrey’s personal life led her to accept the role.

By April 1978, her marriage to Dotti had run its course. The divorce became final three years later, and Dotti didn’t make it easy. The fact that he’d entertained his girlfriends in their apartment was the final straw. Incredibly, she blamed herself for the breakup of this marriage, a union she’d poured her heart and soul into. Her unconditional love hadn’t been enough. With this failure, she once again lost the concept of creating a family, which was the prime aim of her existence.

Now she had two children by two fathers, and two divorces. In that respect, she was no better than her mother, and she felt her sons were emotionally reliving her childhood. Audrey’s friends were deeply concerned about her emotional state in this time.

Bloodline was a lifeline. Escaping back into her career would, she hoped, enable her to survive this latest blow. The film she had really wanted to do a couple of years earlier was The Turning Point, a story of the ballet world, with a tour-de-force role as a legendary prima ballerina on the verge of forced retirement. She had asked for the part, but Anne Bancroft had already been cast. Hepburn would always refer to this film as “the one that got away”—and it also got away from Audrey’s former fellow Dream Girl, Princess Grace. Grace, on the board of directors of 20th Century-Fox, had been given a copy of the Arthur Laurents script. She loved it and sent it on to Prince Rainier for approval. A comeback at last! But permission was, once again, denied.

The Bloodline script was rambling. Sheldon’s novel was a fun read (he had a huge female readership), but it didn’t translate into a good script. Audrey would at least be comfortable with the director, her old pal Terence Young. A $1-million-plus salary closed the deal. She’d be playing the glamorous heiress to a pharmaceutical fortune (in the book, the character was in her early twenties). Gazzara would be the firm’s CEO, and they marry after her father, the owner of the firm, dies in a questionable accident.

There was—or was supposed to be—spellbinding intrigue, mystery, and danger. Filming would take place on international locations, with an all-star supporting cast, including James Mason, Irene Papas, Maurice Ronet, Romy Schneider, Beatrice Straight, Gert Fröbe, and Omar Sharif. None of them were happy with the script or their roles. Apparently, all had done it for the money.

Audrey arrived on location accompanied by a bodyguard. Personal security had become a prime concern. To some, it appeared she’d had a face-lift, and a new hairstyle gave her a different look. For the first time on-screen, she would be smoking a lot of cigarettes (always gracefully, of course). Offscreen, she still chain-smoked.

![]()

With Gazzara, Audrey was once again repeating the Holden scenario, with a major difference: this time she was calling the shots. She made the first move, and it was not subtle. Her gently aggressive character in Charade might have done exactly the same thing to capture the reluctant Cary Grant’s attention.

Gazzara, seated in his canvas chair one morning on the set, was waiting to be called. He was reading a book. Audrey walked over to him. He looked up from his book and told her he had begun it last night and couldn’t sleep. She replied that she had the same problem: “When it happens to you again, feel free to call me. We’ll keep each other company.” They soon discovered they had more in common than insomnia. They were nearly the same age (Gazzara was a year younger). Ben’s second marriage, to actress Janice Rule, was, like Audrey’s, on the rocks. As was the case with Audrey and Mel, it was Gazzara’s career, not Rule’s, that had skyrocketed. Janice Rule was beautiful and talented, but the camera didn’t love her. Kim Novak ended up landing the role in the movie version of Picnic, which Rule had created on the stage.

“Audrey was unhappy in her marriage and hurting; I was unhappy in my marriage and hurting, and we came together and we gave solace to each other and we fell in love,” recalled Gazzara. When they discussed their marital woes, she was candid about the Dotti mess; she even confided that at one point she’d considered suicide—certainly only a fleeting feeling, one she would never have contemplated seriously, not with her two boys to consider.

As with Bill, the chemistry was there from the start. After filming a love scene, Gazzara knew for certain that she wasn’t acting. After they got to know each other, he was shocked to discover how unsure she was of her talent. “We were having a drink in Munich . . . and she told me, ‘Do you know, Ben, I never thought I was a good actress.’” He found her “so self-effacing, and that’s why, on the screen, she was so genuine because what you saw on the screen you saw in life—that smile and the way she lit up a room She just had it.”

Still—a Tony for Ondine, an Oscar for Roman Holiday, five other Oscar nominations, including one for her inspired work in The Nun’s Story, the impact she’d had in Breakfast at Tiffany’s, eight Golden Globe nominations. After all she had accomplished, the stardom she had achieved and sustained, she still had doubts about her acting ability?

She considered herself strictly the product of great directors. Perhaps the success itself had come too easily—she’d certainly put in the hard work, and then some, to achieve the performances. She was still putting in the hard work, and Gazzara said he spent a great deal of their time together trying to convince Audrey that she was a great actress.

At the beginning of the affair, the couple agreed that their relationship would be an interlude that would last only as long as the making of Bloodline. Audrey, too much of a romantic at heart, soon felt herself wanting this to be more.

When filming on Bloodline wrapped early in 1979, so did their affair. Or so he thought. “Audrey had a life in Europe and Switzerland,” he said; his home bases were Los Angeles and New York. “It was impossible. Life got in the way of our romance.” But unlike her affairs with Bill and Albie, what transpired between Audrey and Ben would find its way into a script.

Meanwhile, Terence Young’s next film, to be made in Korea, was to star Gazzara, and Audrey was pleased that her son Sean would be a production assistant. Although both Rome and Tolochenaz, Switzerland, were far from Korea, she’d have a legitimate reason to drop in on the set.

However, Gazzara would soon be involved with the woman who would soon become the next Mrs. Gazzara. When the Gazzaras subsequently traveled to Rome, Audrey, according to Ben, contacted him at his hotel. She wanted to see him. He replied that that would not be possible, then called her back to explain. He recalled that when she answered the phone, he remained silent—neither of them said anything. She didn’t say his name, but finally, “She simply whispered, ‘Good-bye.’”

He later said, “I was flattered that someone like that would be in love with me. . . .” Gazzara also said that Audrey had told others that he’d broken her heart. “She was so kind and sweet,” he said. “And I hurt her.”

But it wasn’t good-bye; far from it.

In true Hollywood fashion, there was a project that would bring them back together. It was conceived by Gazzara’s buddy, director Peter Bogdanovich, one of the premier directors of the 1970s. His films had their roots firmly embedded in those of the great directors of the 1930s and 1940s. Recently, there had been expensive Bogdanovich bombs, including At Long Last Love and Nickelodeon. This new project, They All Laughed, was in part inspired, if that’s the word, by Gazzara’s romance with Audrey. The two men collaborated on the script, which was credited to Bogdanovich and Blaine Novak, with the hope that she would play the part.

Was there any chance that Hepburn would play a character in any way based on herself? Well, she very well might. She still had feelings for Gazzara. What better way to rekindle their relationship? They would live it all out on-screen, and magically all the hurt between them might disappear. The film would be shot entirely in New York, and Sean, now nineteen, was going to be hired as a production assistant (and would play a small role in the film).

Dotti was continuing to present problems, and the animosity between husband and soon-to-be ex-wife was affecting their relationship with their son Luca. For Audrey, escaping to New York, and the insulated world of filmmaking, was a welcome prospect.

Audrey’s signing on would enable Bogdanovich to secure financing (in addition to the millions of his own money he was investing in the production). The shooting schedule, like that for Robin and Marian, was only six weeks, and Audrey would be paid her usual $1 million. It’s a moot point whether she was aware that Bogdanovich was planning on They All Laughed to be the launching pad for his new star discovery, twenty-year-old Dorothy Stratten. At one point Bogdanovich considered casting himself in the role of the man who falls in love with Stratten, but the part eventually went to John Ritter.

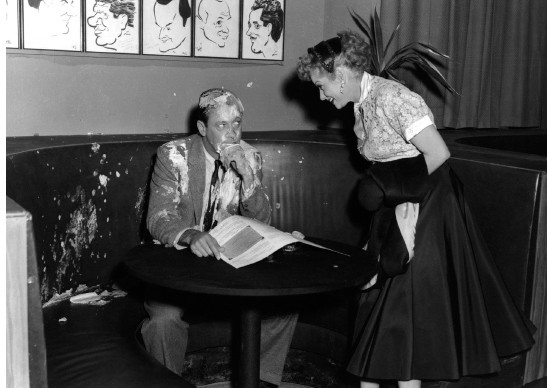

After winning for her performance in Roman Holiday, she was besieged by reporters. Earl Wilson is to her right.

Courtesy Photofest

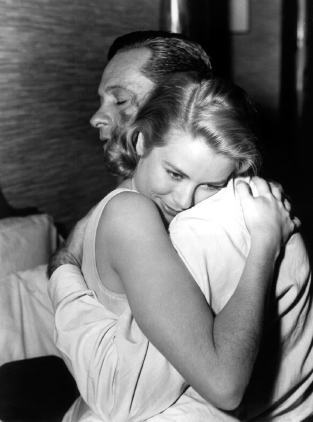

With Jennifer Jones in Love Is a Many Splendored Thing (1955). He’d wanted the studio to buy the property for him and Audrey.

Courtesy Photofest

His appearance on I Love Lucy, early in 1955, remains a classic.

Courtesy Photofest

Bill’s antidote to Audrey: Grace Kelly. They made two films together, The Bridges at Toko-Ri and The Country Girl, both released in 1954. She was up for an Oscar for the latter.

Courtesy Photofest

An emotional Grace, holding her Oscar, presented to her by Bill (1955). Their affair was over.

Courtesy Photofest

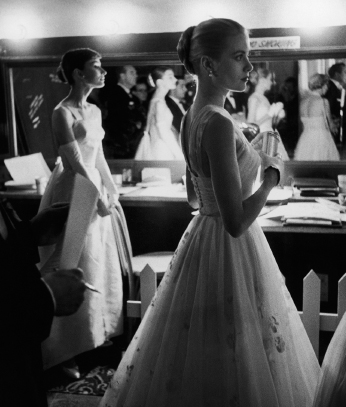

Audrey and Grace, backstage at the Oscars (March 1956). Twenty-seven years old, both had won Oscars, and both had expected to become the next Mrs. William Holden (he was away, filming on location).

Allan Grant/The LIFE Picture Collection/Getty Images

Audrey’s antidote to Bill: she married Mel Ferrer, on September 24, 1954. Here with Mel and her beloved Mr. Famous.

Courtesy Photofest

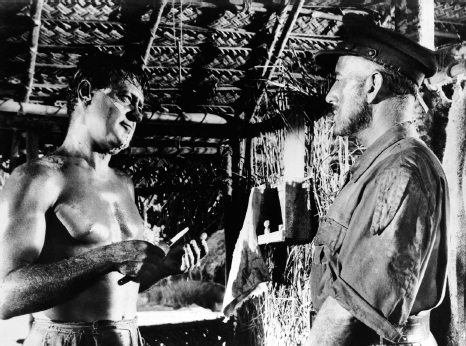

Bill struck gold, critically and commercially, with The Bridge on the River Kwai (1957). His profitable participation deal made him a wealthy man. Co-star Alec Guinness won the Oscar for Best Actor.

Courtesy Photofest

A bemused Bill poses with Tony Curtis, in full costume and makeup as “Geraldine” in 1958, on the set of Billy Wilder’s classic Some Like It Hot.

Courtesy Photofest

A costume test for The Nun’s Story (1959). She delivered a superb performance in the film and was again Oscar-nominated but did not win.

Courtesy Photofest

Audrey in a signature role: as Holly Golightly in Breakfast at Tiffany’s (1961), and yet another Oscar nomination.

Courtesy Photofest

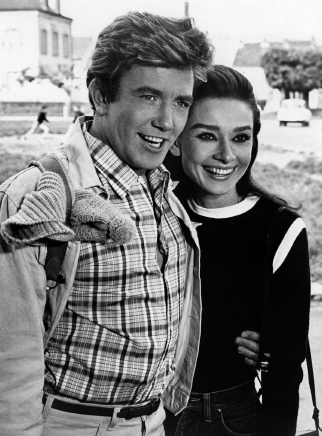

Reunited: Audrey and Bill, almost a decade after Sabrina, tackle Paris When It Sizzles (not released until 1964). She was playing his Givenchy-clad secretary, he was a Hollywood screenwriter.

Courtesy Photofest

Bill’s feelings for Audrey were strong as ever, and so was his drinking.

Courtesy Photofest

The kisses, as before, were real. Mel being around made Bill unhappy and uncomfortable.

Courtesy Photofest

Courtesy Photofest

Courtesy Everett Collection

Audrey’s great friend Capucine (in scarf), a star herself, visits the Paris set. She was now Bill’s lover and often his caretaker (Bill, at right, is in the cowboy hat).

© Bob Willoughby/mptvimages.com

Audrey starred with Cary Grant in Charade (1963), a romantic thriller in which the two stars never kissed (Grant, twenty-four years Audrey’s senior, was wary of seeming like a lecherous older man). Here, director Stanley Donen confers with his stars.

Courtesy Photofest

A new kind of ordeal: My Fair Lady (1964). Director George Cukor became one of Audrey’s closest friends.

Courtesy Photofest

Their on-screen chemistry was hardly in the Holden-Hepburn league, and Capucine was not presented properly. She and Bill made two films together, The Lion (1962) and The Seventh Dawn (1964).

Courtesy Photofest

Audrey and Albert Finney starred in Two for the Road (1967). Off-camera, it was Holden redux.

Courtesy Photofest

Dream girls Grace and Audrey, almost a decade after their affairs with Bill. L. to R.: Grace, Prince Rainier, Audrey, and Mel, at a 1965 charity benefit for elderly actors. Both women were thirty-six, Audrey still at a career peak. Grace longed to return to the screen.

Courtesy Photofest

Mel Ferrer visits his wife on the set of Wait Until Dark (1967). A divorce was finally on the horizon.

Courtesy Photofest

Audrey, a few months shy of forty, marries her second husband, Dr. Andrea Dotti, on January 1, 1969. He was nine years younger. She now had two titles: baroness, which she was born with, and countess.

Courtesy Photofest

Capucine visits Audrey, wheeling a baby carriage, in Gstaad, Switzerland. Hepburn had achieved her longed-for wish: she had given birth to a second child, Luca. Older son, Sean, now had a half brother.

Rex Features/Courtesy Everett Collection

Holden with mentor Barbara Stanwyck, over forty years after she’d helped him through their 1939 film, Golden Boy. Although she was fourteen years his senior, she’d outlive him by almost a decade.

Courtesy Photofest

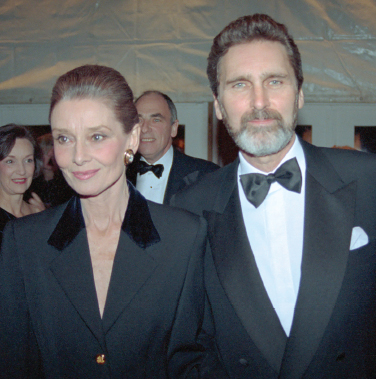

With Ben Gazzara during production of They All Laughed (1981). Her hopes of reigniting the passion they’d shared during production of Bloodline, a couple of years earlier, were in vain.

Courtesy Photofest

With Robert Wolders, the last great love of her life.

Holden with Stefanie Powers, the last great love of his life. He was twenty-four years older.

© ImageCollect.com/Globe-Photos

All the passion and perseverance that had gone into her career, and raising her children, now went into Audrey’s efforts to promote UNICEF.

UNICEF/ Hulton Archive/Getty Images

Similar to Audrey with UNICEF, wildlife preservation became Bill’s great charitable endeavor.

Courtesy Photofest

From a professional point of view, Audrey might have been concerned, if “presenting” Ms. Stratten, as Audrey had been presented in Roman Holiday, Sabrina, and so on, was the director’s intention and preoccupation. Where would that leave her? Stratten was a beautiful blonde, reminiscent of a very young Cybill Shepherd (another Bogdanovich discovery, ten years Stratten’s senior). Stratten had been a Playboy centerfold, and a Playmate of the Year. She had virtually no acting experience, but she did have a fiercely possessive, violent husband, who was jealous of her impending big break and Bogdanovich’s interest in her. Audrey had something in common with Ms. Stratten: both were of Dutch descent.

![]()

Bloodline opened in June 1979, to mostly poor reviews. In New York City, at the Tower East Theater on Manhattan’s East Side, there were lines around the block. Elsewhere, at theaters throughout the city, the country, and the world, there were lots of empty seats. Audrey and Ben did not look particularly good together on-screen. The couple’s chemistry offscreen didn’t ignite any sparks on-camera. Box-office rentals for the film fell considerably below its cost. Audrey had made a dud.

Romantic comedy à la They All Laughed, conceived partially as an update of the classic French film La Ronde, suited Gazzara about as well as it would have the late Edward G. Robinson. When, before production began, it became obvious that Gazzara was no longer interested in Audrey romantically, an icy calm took hold of her. She wasn’t beyond anger, and she responded in the way anyone in a similar position would, if they could: she decided to walk out on the film. If the financing that her name guaranteed took a walk, too, that would be Bogdanovich’s—and Ben’s—problem to work out. Her sensibilities had been abused and she had been hurt.

Just as it all began to feel overwhelming—this terrible mess of a life one could get into by the age of fifty—she made a telephone call to someone she had met a while ago on the West Coast. She had a warm feeling that something good might result. But she wasn’t placing any bets on it.