![]()

TWO MONTHS BEFORE, EVERYTHING HAD BEEN SO DIFFERENT—SHE had been happy with Bill, and she missed him. She still loved him and thought of him often—the smiles, the laughter, the kisses. But it was over now. She was alone. At this vulnerable moment, Mel Ferrer reappeared. Audrey was happy to see him. Mel had news: he was now a free man. In the months since they had met, he had divorced his wife. His attentiveness and sense of romantic urgency was just the antidote to Bill that Audrey required.

Bill’s antidote to Audrey was about to enter his life. He undoubtedly hoped her appearance on the scene, and his subsequent involvement with her, would make Audrey jealous and sorry that she had abandoned him; then she would want to bring him back into her life. Holden did not give up easily. Actor Glenn Ford noted that his friend Bill was not a man who liked to lose, and he never accepted failure without a fight.

Mel convinced Audrey that he loved her and would dedicate himself to her as a woman and an artist, and although he had four children already, he was eager to have more with her. Now that she had a perspective on their relationship, she felt a sense of guilt on the effect her affair with Bill might have had on his children; she hoped they hadn’t been hurt the way she had been by her own mother’s love affairs and divorces.

Mel’s background spoke well of him. His father was a well-known Cuban American surgeon; his mother was socially prominent. His sisters and nephew worked for Newsweek magazine. Everything about him seemed first-rate. Of course, he had a past. So did she. Mel and Audrey had much in common on all levels, going back to their childhoods—Audrey had experienced malnutrition during her youth, Mel had had to contend with a bout of polio. They were both survivors.

Ferrer was no Bill Holden—he did not have that beguiling, devil-may-care attitude; he was not as devastatingly attractive or sensitive. The very lack of those qualities, perhaps, which had so overwhelmed Audrey, was a plus at this juncture. There was nothing boyishly playful about Mel. He outlined a wonderfully rosy future for Audrey and himself—working together, loving together—they could be the successors to Alfred Lunt and Lynn Fontanne, to Laurence Olivier and Vivien Leigh. He even had a play, Ondine, ready to go that the two of them could star in on Broadway. He had told her about it when they first met. And there was fresh news: Alfred Lunt said he would direct! Was she interested now? Yes!

There was no question in the public’s mind that Audrey could successfully fulfill the female half of a Lunt-Fontanne, Olivier-Leigh equation; with laserlike determination, Mel was intent on proving that he was Audrey’s worthy equal on the world stage. She liked the idea.

In the meantime, the Audrey-and-Bill saga had to be brought to an acceptable conclusion. Too many people knew about it. There could still be scandal and repercussions. A bizarre scenario was about to be played out, starring Audrey, Bill, Ardis, and Mel. The Holden home was the setting for an announcement. Present were the four principals—along with key Paramount and select other executives involved with Audrey’s and Bill’s careers.

“Bill and Mel were as ‘friendly’ that night as two lions ready to tear each other’s throats out,” recalled a top-level Paramount (later MCA) executive present on the occasion. “And a scalpel was necessary to cut through the tension between Audrey and Ardis. It was quite a night!” The studio wanted nothing to tarnish Audrey or Bill’s images, or the prospects for Sabrina, which had been previewed successfully, even minus final soundtrack and other effects, and was expected to be a big hit on its release later in the year.

The purpose of that night’s gathering was to announce Audrey’s engagement to Mel—a move intended to diffuse all the innuendo and gossip that had been building for months about Audrey and Bill. By having Audrey announce her betrothal at Bill’s house, with Bill’s wife present—how could anyone say there had been anything serious to all those nasty rumors? Cocktails were abundant, conversation was forced; a synthetic cordiality filled the room. Audrey’s eyes avoided Bill’s. His bloodshot eyes underscored his angst. He was clearly a man carrying a torch.

Audrey’s fans were delighted to learn that their idol was engaged. It seemed she had found true love at last, although Mel Ferrer was hardly the kind of romantic figure the fan magazines could get excited about. And to insiders there remained the question: Were Audrey and Bill really no longer a couple? All knew how mercurial and unpredictable actors were when it came to matters of the heart.

![]()

The Oscars were coming up—March 25, 1954, was the big night, and insiders eagerly anticipated the drama that might be in store: Audrey and Bill, face-to-face, sweating out the Oscar derby. Audrey, however, wouldn’t be there; she would not have to see or interact with Bill. She was in New York, starring on Broadway, opposite Mel Ferrer in Ondine, in which she portrayed the title character, a water sprite. Director Alfred Lunt had succumbed to the Hepburn magic: “While most people simply have nice manners, Audrey has authentic charm and class.” And the estimable Mr. Lunt had plenty of superstar friends to compare her with.

But she had not expected the play to be such an ordeal, and the theater community was abuzz over Mel’s supposed unwillingness to permit Audrey to take a solo curtain call. Mel was labeled a Svengali; Audrey his bewitched Trilby. “It was the talk of the town,” recalled wire service correspondent Doug Anderson. Others noted that it was ironic that although Ferrer was portraying a knight errant in the play, when it came to taking bows, obviously chivalry was dead.

Oscar fever was at a high pitch, even in New York, because the ceremonies would be televised from both coasts this year, with several major nominees in New York, including Audrey, Deborah Kerr, Geraldine Page, and Thelma Ritter. Hepburn, the girl who said she couldn’t deal with too many emotions at once, was beside herself when the evening arrived. Photographers surrounded her from the moment she left her show and got into a limousine, complete with police escort, sirens screaming, to race her to the Oscar ceremonies at New York’s NBC Century Theater.

En route, she removed her blonde stage wig and, once at the Century, went to a dressing room to remove her heavy stage makeup. A Life magazine photographer had been given permission to “follow” Audrey, but other photographers weren’t shy about doing their jobs, trying to coax her out of the dressing room: “Hey, Skinny, come on out!”

The baroness was waiting for her daughter inside the packed theater, which was crowded and noisy. “Smile, dear,” said her mother, as Audrey sat down. Gary Cooper, on film (he was in Mexico) was reading the list of nominees for Best Actress. Donald O’Connor, hosting the Academy Awards in Hollywood (Fredric March was the New York emcee) opened the envelope and shouted out Audrey’s name.

The applause was loud and sustained. One account related Audrey’s reaction: “A very confused young lady mounted the steps to the stage, turned suddenly, and began to wander off toward the wings. Fredric March guided the winner back to the podium. ‘This is too much,’ Audrey sighed.”

Holden, with a smiling, formally gowned Ardis by his side, was in Hollywood when Shirley Booth in New York (she was the previous year’s Best Actress winner, for Come Back, Little Sheba) announced the Best Actor winner: “William Holden!”

Afterward, when asked how she was going to celebrate, Audrey said: “At home, with Mother.” However, after an hour with Mother, Audrey and Mel joined Deborah Kerr, and her husband, Anthony Bartley, for post-awards cocktails at the Plaza Hotel’s elegant nightclub, the Persian Room. Many of New York’s leading columnists were already there, including Dorothy Kilgallen and her husband, producer Dick Kollmar, along with Leonard Lyons, Louis Sobol, and Earl Wilson. The public might have been kept unaware of Audrey’s romance with Bill Holden, but it was common knowledge to the showbiz press. Kilgallen’s eagle eye was alert to anything signaling trouble in paradise between Audrey and Mel, but there was no such news to report. The young star seemed content and affectionate with him.

Holden’s post-Oscar celebration took place at Romanoff’s, the restaurant frequented by the town’s leading stars and filmmakers, where Bill toasted Billy Wilder: “Of course, I knew it all the time.” But there would be no photographs that night of Hepburn and Holden together, clutching each other and their Oscars.

The morning after, Audrey met with the press in New York, wearing the perfect black suit—V-neck, long-sleeved fitted jacket, pencil skirt, black pumps, perfectly scaled hoop earrings, her hair short with bangs. She posed, as she was asked to, sitting pinup-girl style on the floor, Oscar alongside her; in each hand she held up batches of congratulatory telegrams. A huge smile lit up her face. She couldn’t wait until the photographers left, so she could light up a cigarette.

Several days later, another contest was decided: Audrey and her friend Deborah Kerr had been nominated for the Tony for Best Leading Actress in a Play; Audrey for Ondine and Kerr for Tea and Sympathy. The prize went to Audrey. New York Times critic Brooks Atkinson had described Hepburn’s performance as “tremulously lovely,” and theater historian Philip G. Hill wrote that the show was “a work of extraordinary beauty.” Alfred Lunt won the Tony for Best Director that year. Mel, alas, was Tony-less.

![]()

Bill was desperate to win Audrey back. When she returned to Hollywood, there was an awkward meeting between them when both posed, clutching their respective Oscars but not each other, in front of a giant poster for Sabrina.

Holden was soon off to the Far East to begin shooting his next picture, The Bridges at Toko-Ri, based on the James Michener novel. Bill had formulated a perverse plan to show Audrey how hurt he was; he hoped that after recognizing his torment, she would want to bring him back into her life. “So I set out around the world with the idea of screwing a woman in every country I visited. My plan succeeded, though sometimes with difficulty.” When he later encountered Audrey at Paramount, he told her what he had done. “You know what she said? ‘Oh, Bill!’ That’s all. ‘Oh, Bill!’ Just as though I were some naughty boy. What a waste!”

Baroness Ella van Heemstra Hepburn-Ruston holding her one-year-old daughter, Audrey (1930).

Courtesy Photofest

Mary Blanche Ball Beedle with her two-year-old son, William Jr. (1920).

Courtesy Photofest

Pre-Bill: Audrey, twenty-two, with fiancé James Hanson, thirty, a British millionaire (1951). She called off the marriage.

Courtesy Photofest

Pre-Audrey: Bill and wife, Ardis (Brenda Marshall), best man and matron of honor at the marriage of Nancy and Ronald Reagan (1952). The Holdens had been married for eleven rocky years.

Courtesy AP Images

The image was launched—Audrey in her first starring vehicle, Roman Holiday (1953). She was up for an Oscar as Best Actress.

Courtesy Photofest

Bill, Ardis, and their two young sons, Peter and Scott (1954). Seemingly, they were the ideal American family.

Courtesy mptvimages.com

Billy Wilder’s Sunset Boulevard (1950) had rescued Bill from cinema oblivion. In 1953, he was up for an Oscar as Best Actor for Stalag 17.

Courtesy Photofest

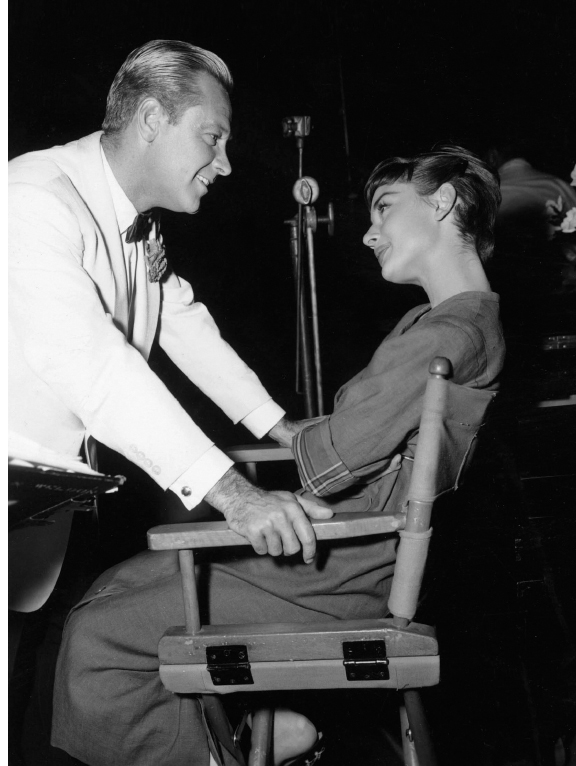

On the set of Sabrina (1954). The attraction between them was instantaneous.

Studio insiders marveled at how terrific they looked together.

Courtesy Photofest

Courtesy Photofest

With Humphrey Bogart, on Sabrina location, on Long Island, New York. She was shivering, he lent her his jacket.

Courtesy Photofest

Marlene Dietrich visits the Sabrina set. The common denominator for this unlikely trio: director Billy Wilder.

Courtesy Photofest

The public was never the wiser: Bogart actively disliked both his co-stars.

Courtesy Photofest

Holden and Bogart. They did not like each other.

Courtesy Photofest

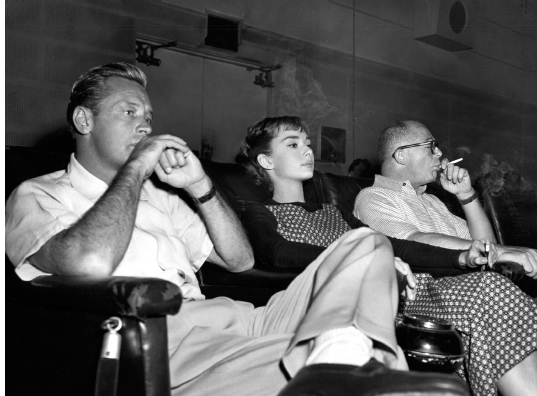

Bill, Audrey, and Billy Wilder watch Sabrina rushes in the screening room. Neither Bill nor Audrey was confident, then or later, about their work. Wilder said the most talented actors rarely thought they were any good.

Courtesy Photofest

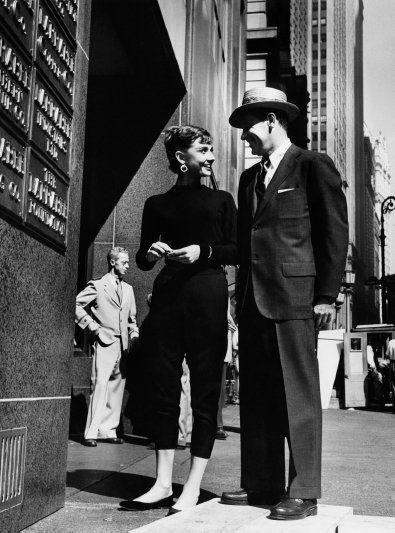

Filming, with Bill, on Sabrina location in New York City. It was a happy time for the couple.

Courtesy Everett Collection

Courtesy Everett Collection

Courtesy Photofest

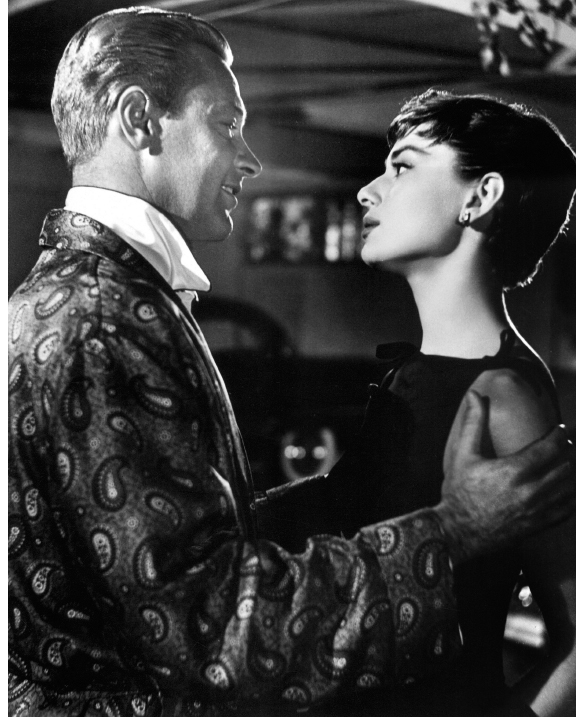

The emotions were real.

Courtesy Photofest

Givenchy adjusts a scarf on Audrey during a fitting (1958). She was his muse.

Courtesy AP Images

Audrey in Sabrina black, timelessly stylish. “All women who have it [style] share one thing: originality,” noted Diana Vreeland. Audrey’s “look” emerged at exactly the right moment in her career.

Courtesy Photofest

Bill with wife, Ardis, at Romanoff’s restaurant, holding his Oscar for Stalag 17.

Courtesy Photofest

Arriving solo, on March 25, 1954, for the 1953 Oscar ceremonies in New York. Audrey was appearing on the Broadway stage in Ondine. Bill was on the west coast, attending the festivities with his wife.

Courtesy Photofest

Back on the west coast, Audrey poses with Bill and her Oscar, a giant poster for Sabrina behind them. She had ended their affair.

Courtesy Photofest

He still held out hope, in spite of what Audrey did next: she married Mel Ferrer. Bill never thought she would go through with it. But the ceremony took place on September 24, 1954, in Bürgenstock, Switzerland. Audrey looked spectacular in a white, tea-length, bouffant-sleeved, princesslike Givenchy masterpiece, a circle of flowers atop her beautifully coiffed head. The marriage was not merely movie star news; it was a fashion event, as her wedding dress reinforced a trend: the short bridal gown. Mel looked very serious, gazing intently at Audrey with a smile on his face.

Bill could not avoid the news, or the photographs, which appeared in major newspapers and magazines throughout the world. Even television news covered the event. “Accept it, live with it, get on with your life” was advice any close friend or therapist would have given Bill (indeed, may have given him). But that wasn’t how Bill lived his life. He never made strangers of his emotions. His heart was broken, the pain was real, and it was deep. And so he indulged himself in a world-class bender.

Bill’s new leading lady was certainly a distraction. She was an actress Audrey was well aware of, and was often compared to: ravishing, blonde Grace Kelly. Her star had risen almost as fast as Audrey’s. She was borrowed from MGM to portray Bill’s wife in The Bridges at Toko-Ri.

Paramount released Sabrina during this period and hit the jackpot—the year’s Best Actor and Best Actress Oscar winners, together with Oscar-winner Bogart, were all in the same picture. And it was directed by yet another Oscar winner, one of the few directors whose name the public knew. Billy Wilder’s final Paramount picture was a hit. Audrey proved Roman Holiday hadn’t been a fluke, and her star status was assured. Her image as the screen’s adult Cinderella would endure indefinitely, even though Sabrina was one of her last Cinderella roles. Both on-screen and in her private life after Holden, Cinderella was entering a new phase. Sabrina had catapulted her to top-rank leading lady. From here on, she was granted the ultimate perquisite for a film actor: script approval. Bill’s unconditional love and support had certainly been a vital element in enabling her to create a memorable characterization of Sabrina.

Arguably, it was Bogart who had scored a coup. Cary Grant would have been great, but considering the role, the results risked being predictable. Coming from Bogart, the performance was a delightful surprise, and critics sang his praises. The actor apologized to Wilder for his behavior, saying that personal issues away from the set were responsible. All was forgiven (“Success is the best deodorant,” as Elizabeth Taylor once observed). Wilder later said, after Bogart died, “[He] always wanted to play the hero. In the end, he was.”

Bill’s “effortless” performance maintained his status as a quintessential leading man. In the industry Holden became known as “Golden Holden,” with a string of smash-hit pictures on the horizon. His feelings for Audrey remained constant; his hopes for a future with her remained alive. They would work together again, and be together again.