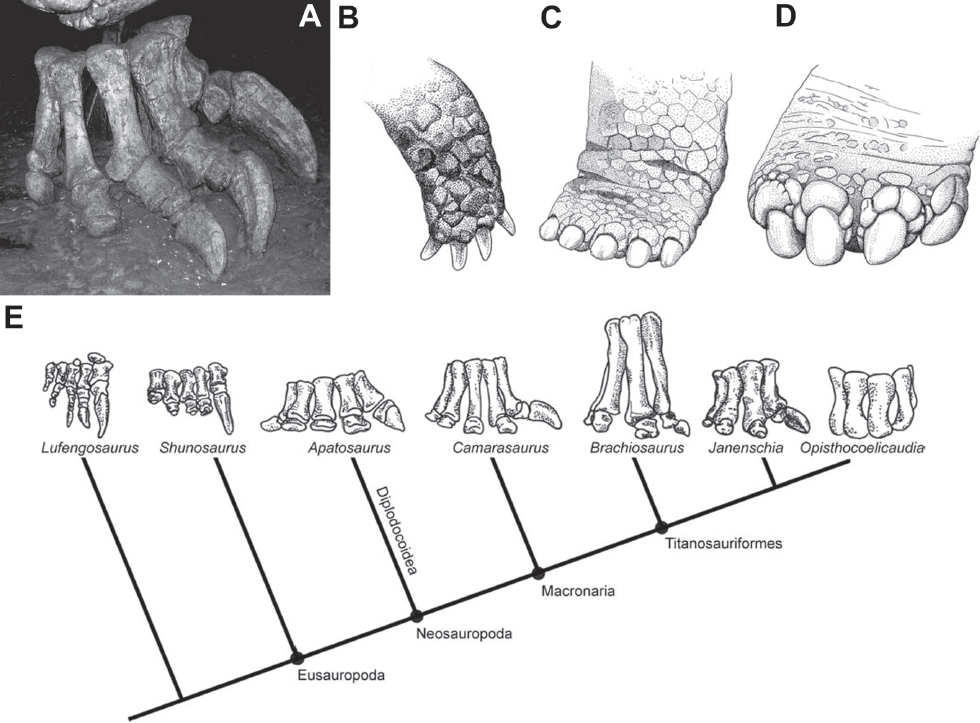

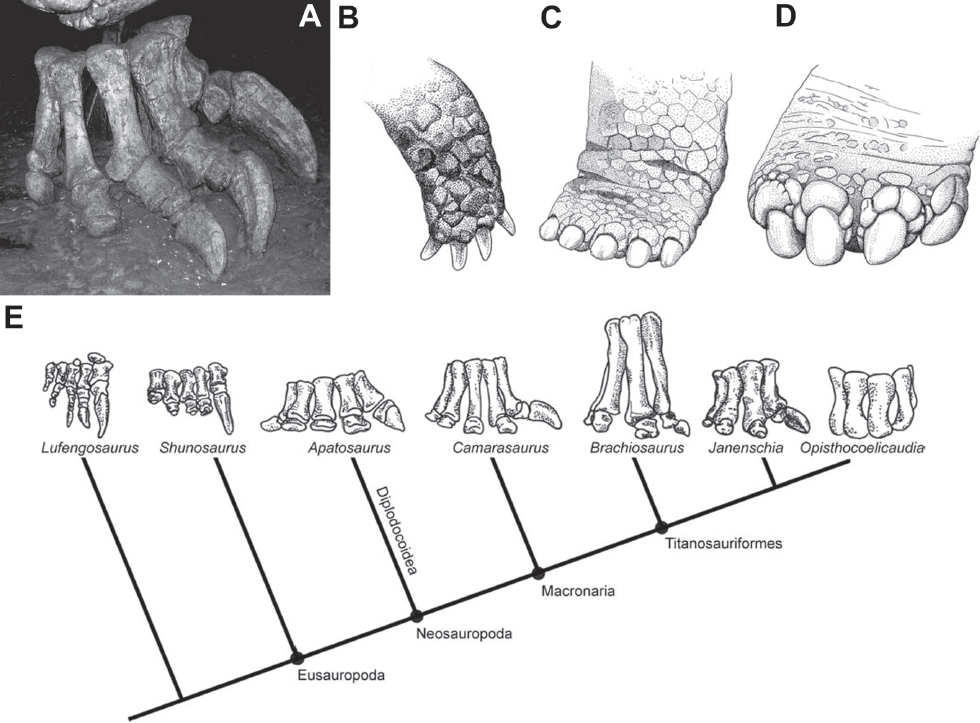

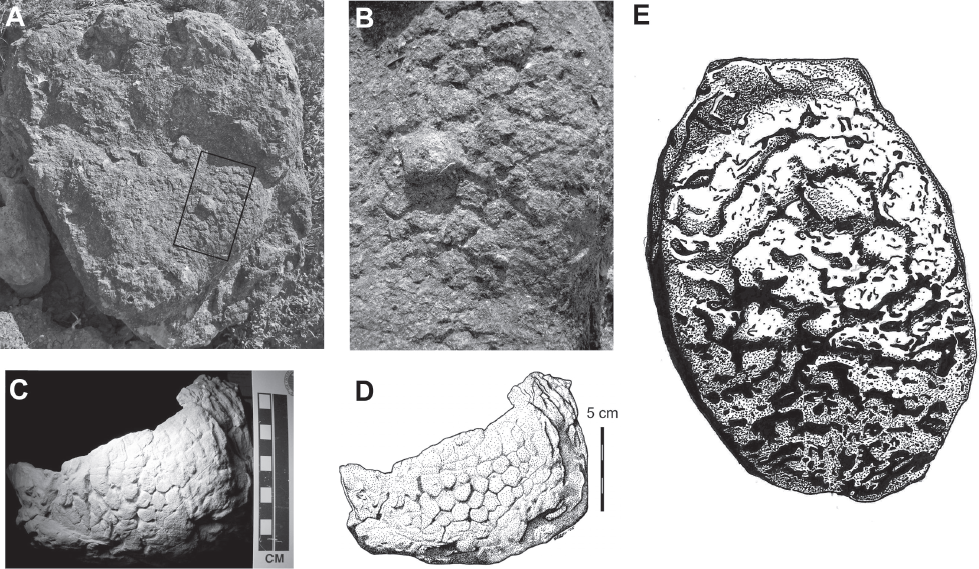

9.1. (A) Mounted diplodocid right pes. Note the deep, laterally compressed unguals and en-echelon arrangement. Morrison Formation, Late Jurassic. Currently on display at New Mexico Museum of Natural History and Science. (B–D) Feet of the specialized scratch-digging tortoise, Gopherus. Note the curvature of the flattened unguals and their similarly en-echelon arrangement. (B) Left manus of Gopherus canyonensis, from Bramble (1982); (C) left manus and (D) pes of Gopherus polyphemus, from Auffenberg (1976). (E) Phylogenetic distribution of sauropod manual morphology (right manus depicted). Manual phalanges exhibit a phylogenetic trend toward reduction and loss, retaining only digit I; derived titanosauriforms take this even further, losing all manual phalanges. Reproduced from Figure 3, Fowler and Hall (2011).

The Flexion of Sauropod Pedal Unguals and Testing the Substrate Grip Hypothesis Using the Trackway Fossil Record |

9 |

Lee E. Hall, Ashley E. Fragomeni, and Denver W. Fowler

SAUROPOD PEDES EXHIBIT A UNIQUE, HIGHLY DERIVED pedal ungual morphology and articulation. During plantar flexion of the pes, the spade-like, laterally compressed unguals are rotated ventrally and deflected laterally across the front of the pes so the claws overlap in an en-echelon fashion; this positions the dorsal margins ventrally and the medial sides face posteriorly, creating a hoe-like structure oriented perpendicular to the plane of limb movement. Several functional hypotheses have been erected in an attempt to explain this feature. One, the miring-avoidance via substrate grip hypothesis, suggests orientation of the unguals during plantar flexion was utilized to generate traction and prevent miring while sauropods traversed muddy substrates. In this study, we test this hypothesis by examining the sauropod fossil trackway record for evidence of plantar flexion utilized during interaction between sauropod pedes and muddy substrates. A review of published sauropod trackways, various unpublished data, and examination of natural track casts (track infillings), found no evidence of plantar flexion being employed during locomotion on muddy substrates. In contrast, trackway evidence unequivocally shows that sauropods utilized plantar extension when walking in soft mud, directing the unguals anteriorly and orienting them vertically. Plantar extension may have prevented torsion or lateral sliding of the limb (much like sports cleats) and could have aided in miring prevention by carving channels for air to circulate around the pes. Detailed skin impressions show sauropod feet were also covered in a rugose, coarsely textured surface of scales and warty tubercles, which could have functioned like off-road tire tread. We maintain that plantar flexion was a feature adapted for scratch-digging behaviors, as similarly described in tortoises, and was utilized for excavating nesting structures.

INTRODUCTION

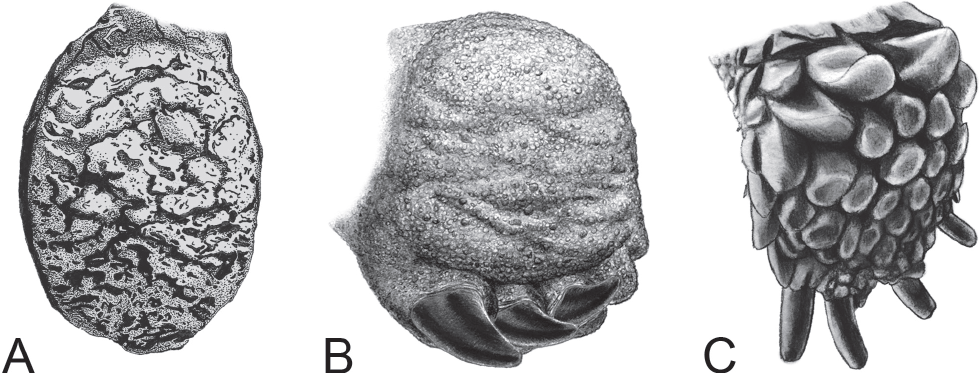

As in vivo records of substrate interaction, tracks have great potential to test paleobiological hypotheses of behavior. Published examples in the dinosaur literature include inferences of trophic relationships (Thulborn and Wade, 1984; Thomas and Farlow, 1997), sociality (Lockley, Young, and Carpenter, 1983; Lockley, Farlow, and Meyer, 1994; Matsukawa, Matsui, and Lockley, 2001), and locomotor behaviors (Lockley and Hunt, 1995; Gatesy et al., 1999; Wilson and Carrano, 1999; Wright, 2005; Milner, Christiansen, and Mateus, 2006, Milner et al., 2009). Sauropod dinosaurs were the largest land animals of all time and exhibited a number of unusual morphological features potentially reflecting the interplay of large body size with the unique biology and life history of dinosaurs (Sander et al., 2010; Varricchio, 2011). One such feature is sauropod pedal unguals, which are large, laterally compressed, deep, and are oriented in an overlapping en-echelon arrangement (Fig. 9.1A; Fowler and Hall, 2011). Gallup (1989) noted that the short robust phalanges, strengthening of interphalangeal articulation, and mobility of the unguals of sauropod dinosaurs are similar to scratch-digging mammals (Hildebrand, 1985), and he suggested that sauropod pedal unguals’ primary use was in scratch-digging (specifically for nest excavation). Later, Bonnan (2005) described the changes in ungual orientation that occurred during plantar flexion, where the asymmetric position of the flexor tubercle of the ungual causes lateral rotation of the claw. This brings the deep, flattened medial side of the unguals to face ventrally (down into the substrate; also noted in less detail by Langston, 1974; and Gallup, 1989) so that the claws would be at an angle to the flat base of the foot, thus forming a hoe-like shape (Fowler and Hall, 2011). However, Bonnan (2005) considered a scratch-digging function unlikely and instead preferred Gallup’s alternative hypothesis: that unguals were adapted for substrate grip, providing traction and perhaps preventing miring (although it should be noted that this functional suggestion was only a very minor conclusion). In a 2011 study, we revived the scratch-digging function by comparing sauropod pedal unguals with those of extant tortoises (Fowler and Hall, 2011), which have a similarly unusual shape and orientation (Fig. 9.1B), and which are thought to be adapted for scratch-digging (Bramble, 1982; Ruby and Niblick, 1994). We further suggested that substrate grip was not a selection pressure acting on sauropod ungual morphology based on the observation that sauropod forelimbs underwent a rapid and drastic reduction of unguals throughout their evolution (Fig. 9.1C). Furthermore, sauropod eggs were laid into an elongate, trough-like hollow excavated into the substrate (Fowler and Hall, 2011:fig. 9), which is consistent with the hypothesis that the hind limbs were used during nest excavation (e.g., Vila et al., 2010).

Approaching function purely from a morphological perspective can be problematic as a single anatomical structure may be utilized for several purposes, which may require the same morphological characteristics. In our example, it is difficult to separate any potential morphological characteristics of a substrate grip function from that of scratch-digging, as scratch-digging requires initial gripping of the sediment before subsequent removal. As such, neither suggested function has been adequately tested.

Here we address this apparent impasse by investigating direct evidence of behavior, rather than inferring behavior or function from morphology alone. Despite the possibly similar physical requirements of scratch-digging and substrate grip, these behaviors would be employed at different moments in the animal’s lifetime. This consequently permits formation of testable hypotheses dependent on the observation of specific behaviors being employed at the expected times. In our prior paper (Fowler and Hall, 2011), we reviewed evidence that clearly showed that the hind feet were used in nest excavation behavior; whether the pedal unguals were specifically adapted for nest digging remains an open question (we believe that they are), but it is incontrovertible that they were used to actually dig the nests: scratch-digging for nests passed from a hypothetical function (Gallup, 1989) into a factual function (Fowler and Hall, 2011).

In this study, we examine the fossil trackway record to assess sauropod pedal interaction with the substrate during walking, specifically to search for any evidence that may corroborate a hypothetical substrate grip function. Can this similarly be considered fact?

It is worth noting here the difference between function (or use) and adaptation, at least as used in this study. A function is any use for a structure, whereas an adaptation is a function that is being positively selected for through evolution (either to maintain a particular morphology or to further change morphology of the structure to be increasingly better suited to a particular function). The critical distinction is that it may not matter how many different functions a structure is used for if only one function is being selected for. Moreover, some functions may be being positively selected, whereas others (even common functions) may be negatively selected; a human example is that although we can use our arms and legs to climb trees, our ability to do so is markedly reduced from that of our ancestors. Human limb morphology has evolved (possibly adapted) away from arboreal functions, despite our ability to still use our limbs for this function. This may imply that a different function is being selected for (although care must be taken to avoid straw-man arguments in this context). Thus, establishing adaptation is difficult, as you must be able to show evolution of a given structure and function through phylogeny. In the case of sauropod pedal unguals, adaptation is implied by the evolutionary development of unusual ungual shape and ungual orientation during plantar flexion of the hind limb, especially when contrasted with the reduction and loss of unguals (and in some cases, even all phalanges) on the forelimb. We would tentatively suggest that adaptation is demonstrable in sauropods. Regardless, any inference of adaptation first requires that a hypothetical function is actually employed in that manner by the animal, and this is something that we can easily look for in evidence of behavior. In the case of substrate grip during walking, tracks are that evidence.

TESTING HYPOTHESES

Fossil sauropod tracks and natural track casts often preserve impressions of individual digits and unguals, presenting an opportunity to reexamine the substrate grip hypothesis. Tracks are typically preserved in originally wet sediments; these are the conditions in which there is risk of the animal becoming mired, and hypothesized substrate grip behavior (Bonnan, 2005) might have been utilized. Bonnan (2005:358) reviewed sauropod tracks with ungual impressions and suggested that claws were “deeply impressed,” but they did not note any tracks in which the pes digits were plantarflexed below the footpads into the substrate. This might be expected if the unusual ungual orientation that occurs during digital plantar flexion was an adaptation for substrate grip (Fig. 9.2). In contrast, Pittman and Gillette (1989; pers. comm., 2012) demonstrated that sauropod pedal digits were extended while walking in muddy substrates, and they suggested that they were “wrapped around the lateral margin of the foot” (331) on firmer substrates. A substrate grip function can therefore be broken down into two component functions: traction control (Gallup, 1989; Pittman, 1989; Bonnan, 2005) and miring-avoidance (Bonnan, 2005).

Traction control suggests that sauropod unguals functioned like the bladed-cleats mounted on the soles of many modern athletic shoes; being variably positioned along the long axis of the sole, bladed cleats present a broad surface that is oriented perpendicular to the direction of movement. This helps prevent lateral sliding, increases traction, and decreases torsion (helping avoid twisted ankles). The traction control hypothesis would be supported by observation of plantarflexed ungual impressions in sauropod trackways, especially so if they are oriented perpendicular to the direction of movement. Conversely, a lack of plantarflexed ungual impressions would fail to find support for the traction control hypothesis.

A miring-avoidance function is problematic because Bonnan (2005) did not explicitly explain the mechanics of how this works, and we could not find prior publications describing any man-made or animal morphological analogues. Some animals adapted for snow-covered areas (e.g., snowshoe hare) possess broad spreading feet to distribute weight over a larger area (preventing sinking), and some waterfowl (e.g., coots) possess lobed toes that increase surface area of the foot (aiding swimming) but no examples are known of animals possessing such feet to avoid miring in mud (Fowler and Hall, 2011; although see “post-holing” hypothesis in “Discussion”).

This study further analyzes the track record to see whether support is found for either the traction control or miring-avoidance hypotheses. It is important to note that we are essentially querying the potential adaptive function of the unusual plantar flexion digit rotation that was described by Bonnan (2005); in other words, that if the unusual rotation and orientation evolved for either of the substrate-grip hypotheses, then pes tracks should record digital and/or ungual plantar flexion. Therefore, we expect to make one of three observations where claw impressions are visible in tracks made into muddy substrates: (1) plantar flexion; (2) plantar extension; or (3) “null” where the digits will be in a neutral or intermediate position.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

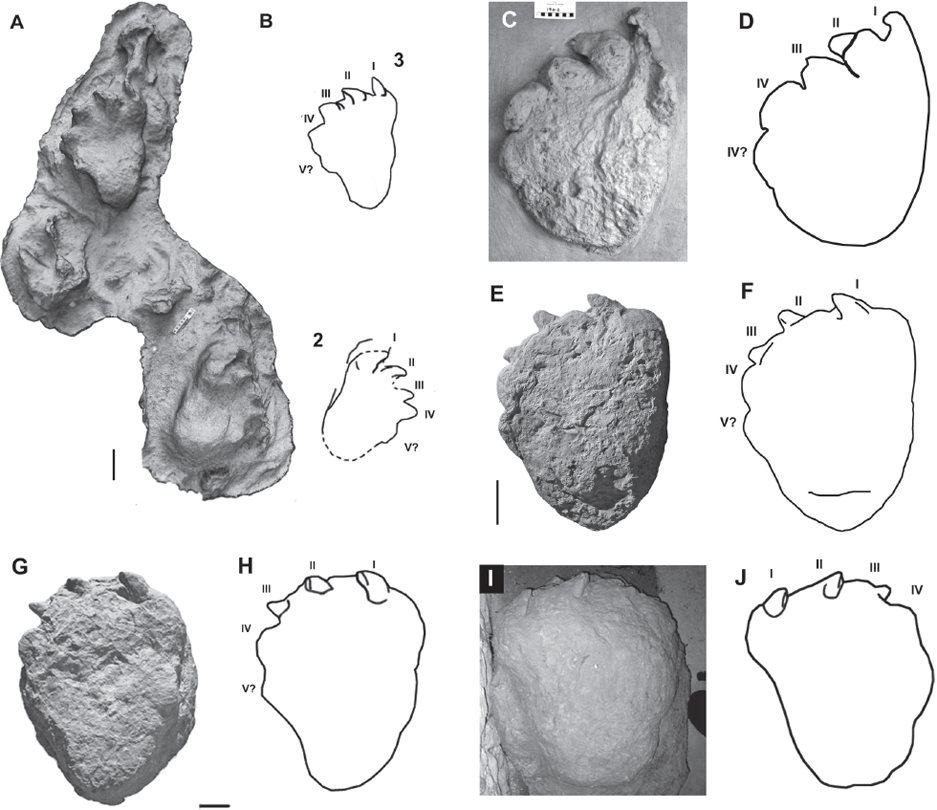

Track morphology was assessed by referencing photographs published in the literature and provided from researchers’ personal data sets, and it was corroborated by physical examination of cast specimens. Specimens were selected using the following standards: (1) morphological landmarks of the pes preserved included details of the unguals to allow examination and interpretation of their positions and actions during track making; (2) specimens exhibited morphology consistent with Neosauropoda (sensu Bonaparte, 1986), wherein the anterolaterally directed, laterally compressed, shovel-shaped unguals are ventrolaterally deflected (Bonnan, 2005). We recorded the presence or absence of external morphological features of the pes, namely impressions of separate digits, including the unguals and/or skin and scales. Preservation of these features indicated little to no secondary deformation. Undertracks, tracks made in especially waterlogged sediments (e.g., the Blue Hole Ballroom large sauropod trackway of Farlow et al., 2012), or generally poor preservation may obscure the features of the pes and thus lack necessary detail. Natural track casts were included in this analysis provided they satisfied the criteria set forth herein. Most trackways that we observed either consisted of undertracks (e.g., Moratalla et al., 1994; Bilbey et al., 2005) or were eroded or weathered such that recognition of morphological landmarks was not possible (e.g., Ferrusquía-Villafranca, Jiménez-Hidalgo, and Bravo-Cuevas, 1996; Ahmed, Lingham-Soliar, and T. Broderick, 2004; Moratalla, 2009). Out of the photos of tracks and trackways examined in the literature (including highresolution images provided by researchers), 34 sauropod track specimens were found that exhibited especially well-preserved ungual impressions (Table 9.1).

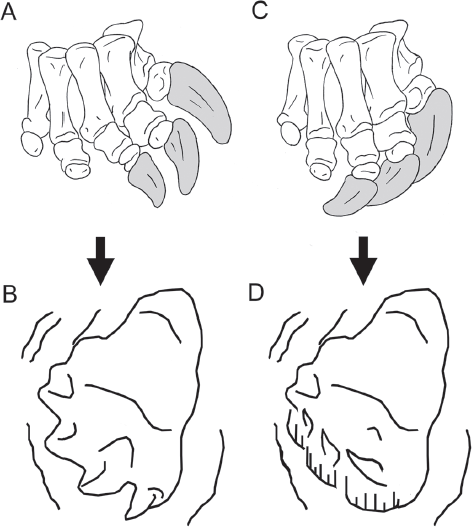

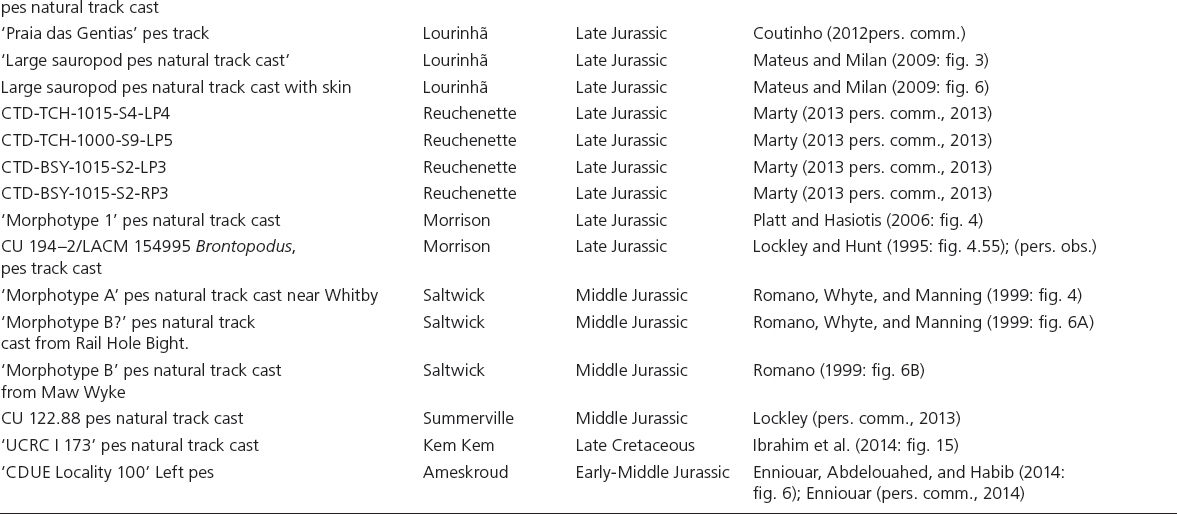

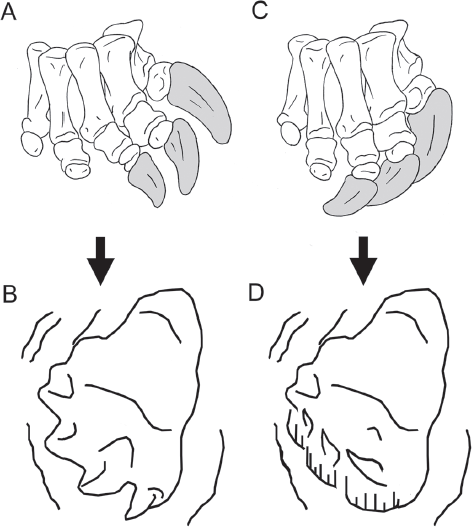

9.2. Extended and flexed sauropod unguals. (A) Foot skeleton and (B) track line drawing (from track 3 in the Blue Hole Ballroom “Small sauropod sequence”) of a right sauropod pes in digital extension. The ungual of digit I is extended anteriorly and oriented nearly vertically, whereas digit II is deflected anterolaterally and slightly medially canted, and digit III is oriented laterally and strongly medially canted. Early Cretaceous Glen Rose Formation. (C) Foot skeleton and (D) hypothetical track line drawing of a right sauropod pes in a flexed position. The unguals of digits I–III are anterolaterally to laterally directed and strongly medially canted such that the broad medial surfaces of the unguals face nearly ventrally and overlap to form a “hoe-like” surface perpendicular to forward motion along the substrate plane. A hypothetical track should exhibit lateral deflection of the unguals along with gouge marks indicative of the anterior portion of the pes receiving an increased amount of force during the imprinting and push-off phases of the step, which also results in the anterior margin of the pes being most deeply impressed. However, these landmarks of a flexed pes were not observed in this study.

Substrate type was noted for each specimen. Tracks tend to preserve in sediments such as wet mud, silt, or sand, which arguably may be considered a hindrance to locomotion. This satisfies the environmental conditions necessary for testing the original flexion-substrate-grip hypothesis as laid out by Bonnan (2005); as such, it was not required to preferentially select or omit tracks based on substrate type.

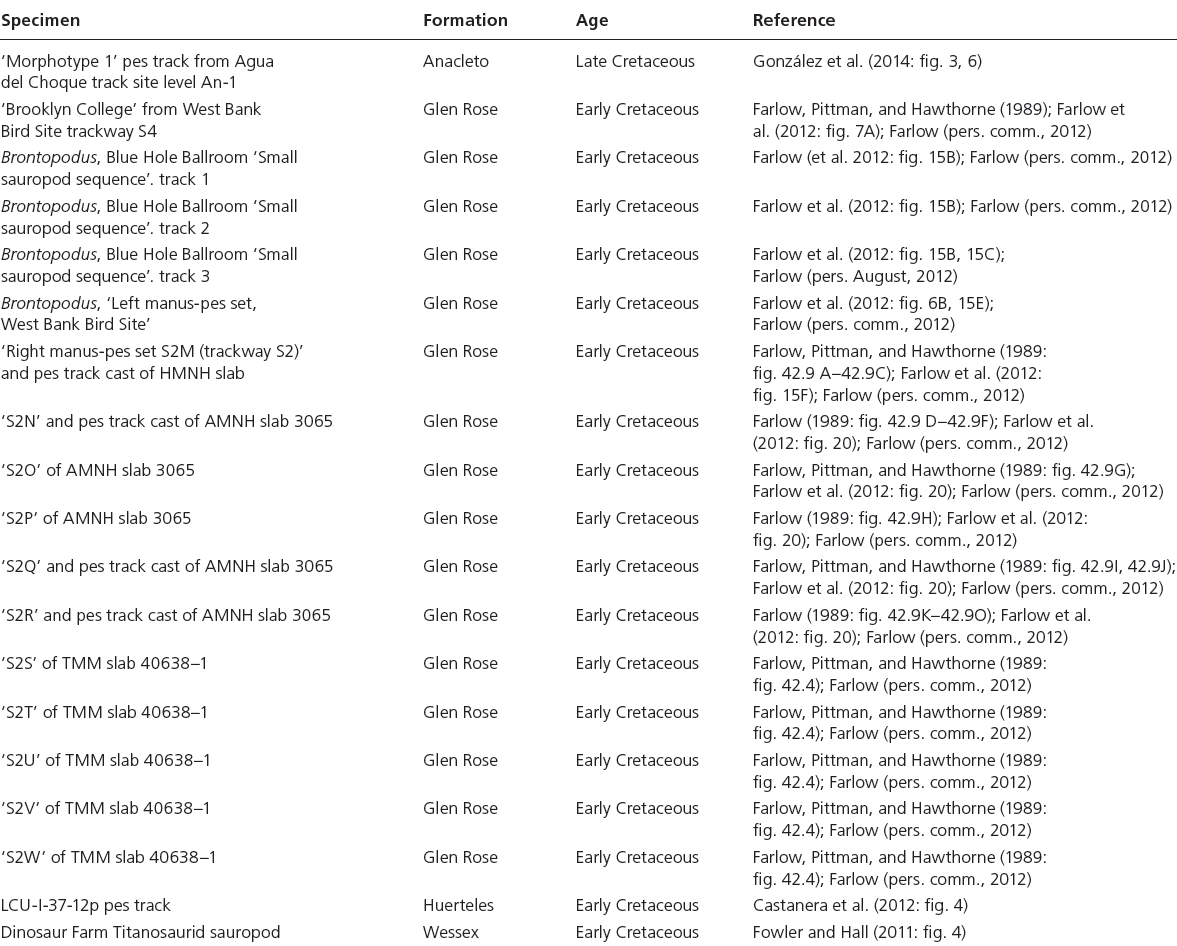

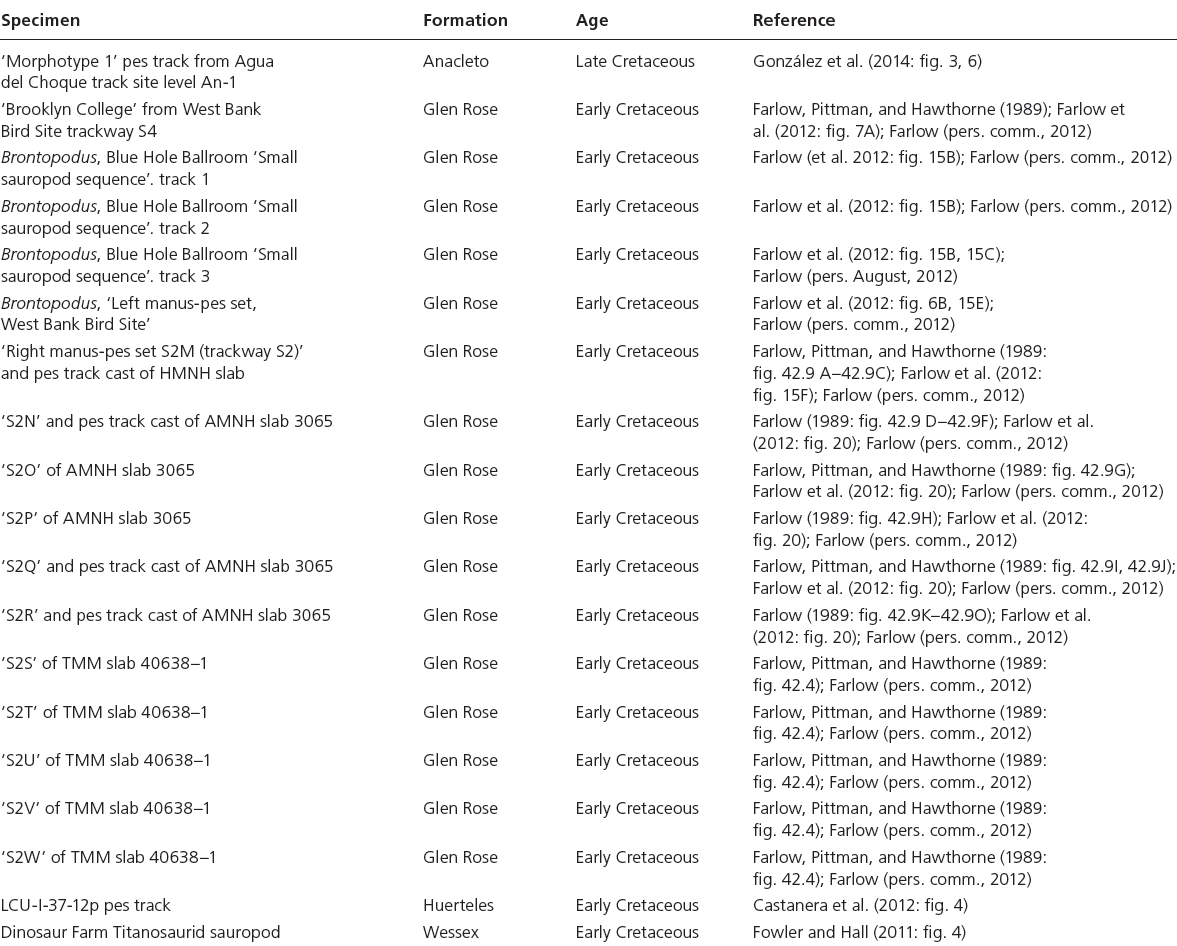

Table 9.1. Sauropod pes tracks and natural track casts

Note: AMNH, American Museum of Natural History; BSY, Bois de Sylleux; CDUE, l’Université Chouaib Doukkali; CTD, Courtedoux; CU, University of Colorado Denver, Dinosaur Tracks Museum; HMNH, Houston Museum of Natural History; LACM, Los Angeles County Museum of Natural History; LCU-I, Las Cuestas I; TCH, Tchâfouè; TMM, Texas Memorial Museum; UCRC, University of Chicago Research Collection.

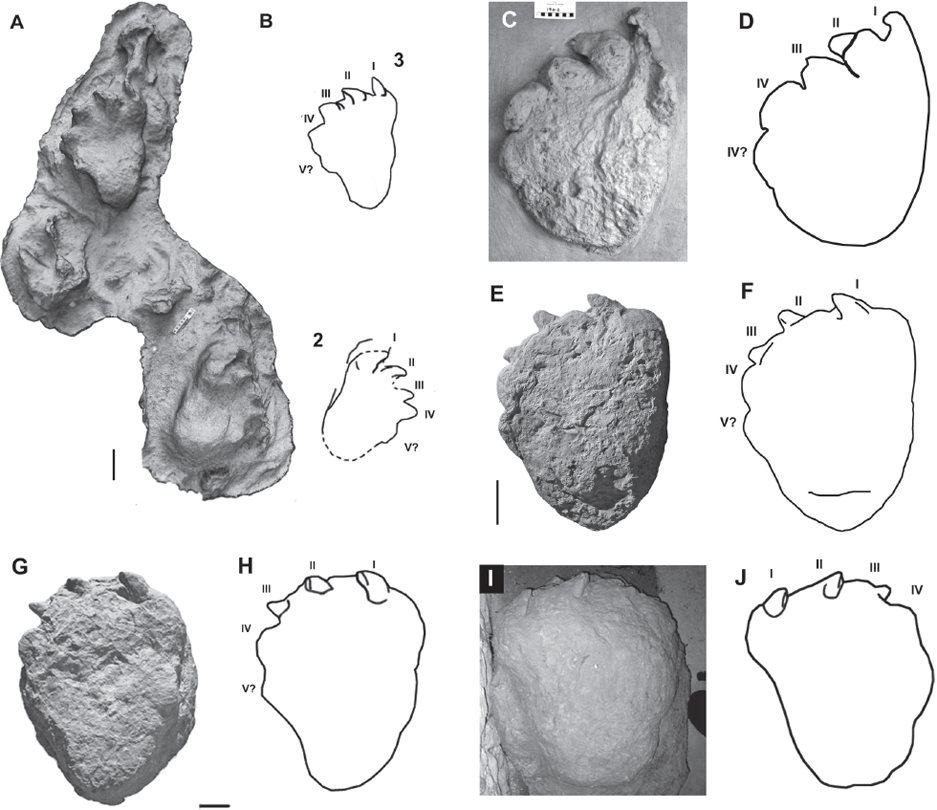

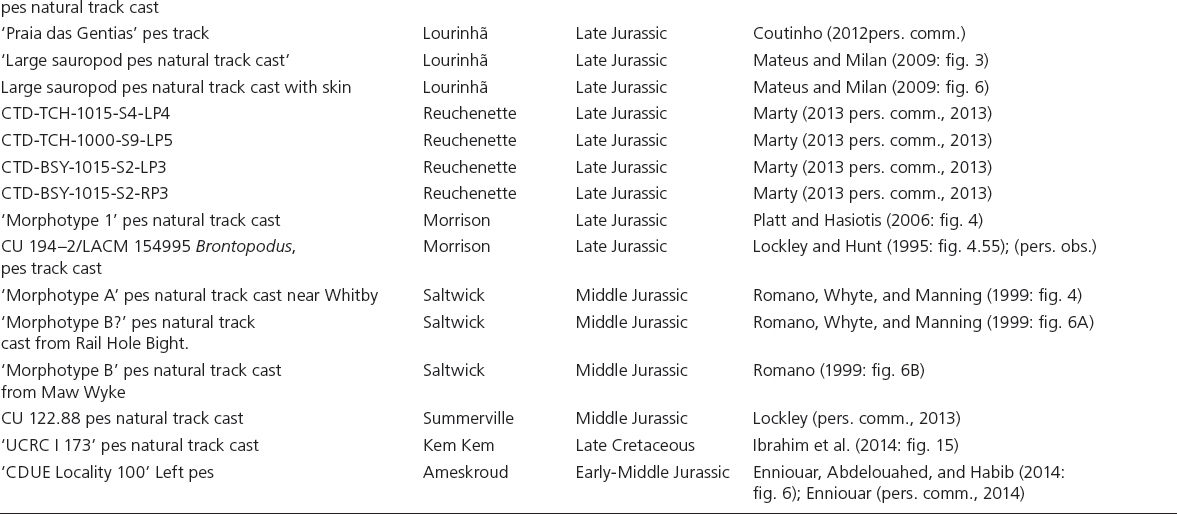

9.3. Well-preserved sauropod pes natural track casts. (A) Latex peel and (B) interpretive line drawing of the last two tracks in the Blue Hole Ballroom “Small sauropod sequence” of Farlow et al. (2012). The numbers 2 and 3 are labels used in this study as the terminal three tracks of the trackway were included in the data set. Note the anterior direction of the digit I ungual and its near-vertical orientation. Scale is 10 cm. Early Cretaceous. (C) Pes cast and (D) interpretive line drawing of Brontopodus specimen described in Lockley and Hunt (1995; CU cast 194-2 pictured). The shallow depth of the track and horizontal alignment of the digits indicate that this track was impressed into a relatively shallow substrate. The anterolateral orientation of digit I and the medial cant to the ungual suggests that this pes was in a neutral position when contacting the substrate as the digits neither extend nor overlap. Scale is 10 cm. Late Jurassic. (E) Pes cast and (F) interpretive line drawing of CU 122.88. Middle Jurassic. (G) Pes cast and (H) interpretive line drawing modified from Castanera et al. (2012), both exhibiting unflexed pedes of large sauropods that impressed fairly deeply into the substrate. Asymmetrical load distribution on the plantar surface is indicated by the staggered positions of the unguals. The anterolateral orientation of the unguals demonstrates that plantar flexion was not engaged. Scales are 10 cm. Early Cretaceous. (I) Pes cast and (J) interpretive line drawing of large Brontopodustype pes impressed moderately deep into the substrate. The anterolateral direction of the unguals, along with the weakly medially canted orientation of unguals I and II demonstrate that plantar flexion was not engaged during track making. Specimen length ~80 cm. Currently on display at the Dinosaur Farm Museum, Isle of Wight, United Kingdom. Early Cretaceous. Modified from Fowler and Hall (2011).

Tracks (and natural casts) were analyzed specifically for preservation of substrate interaction features left by the digits and unguals. This included examining and comparing relative impression depths of the unguals versus the rest of the pes, relative orientation of the unguals in relation to the pes, angle of entry of the unguals into the substrate and the orientation of the pes, amount of angulation or “spread” between unguals, and examination for any “subsurface” features (i.e., evidence of turning or twisting of an emplaced ungual). It was also necessary to form a hypothetical model depicting the track left by a plantarflexed pes in a muddy substrate (Fig. 9.2); to our knowledge, such a feature has not yet been identified from published sauropod trackways. Finally, mobility parameters for sauropod pedal joints were taken from Bonnan (2005) as discussed in our previous study (Fowler and Hall, 2011:4). Full descriptions of track and natural cast specimens are available in the supplementary information.

9.4. Sauropod pes tracks. (A) This Brontopodus specimen (Brooklyn College collection) from the West Bank Bird site, Glen Rose Formation displays morphology typical of the well-preserved pes tracks encountered in this study. Note that the impression of the digit I ungual is anterolaterally directed, oriented nearly vertically and medially removed from digit II. The condition of digit I suggests that the pes may have been partly extended at the time of impression into the substrate. A 1 m measurement tape is used for scale. Early Cretaceous. (B) Large sauropod pes track from the Lourinhã Formation of Portugal preserved in conditions similar to those of A. The nonoverlapping, anterolateral direction of the digits, and the nearly vertical orientations of the digits I and II unguals suggests that this track was not made by a plantar flexed pes. A 1-m measurement tape is used for scale. Late Jurassic. (C) Oblique and (D) planar views of a LiDAR topographic relief image of trackway S2M of the Glen Rose Formation. Lighter shades indicate higher relief whereas darker shades indicate lower relief. The plantar surface of the sauropod pes was asymmetrically loaded during the step. Pes length ~89 cm. Modified from Farlow et al. (2012).

RESULTS

None of the tracks or natural track casts in our data set preserve any indication of plantar flexion being utilized for substrate grip. Furthermore, plantar flexion has not been explicitly noted or described in the literature, or by other track researchers (Farlow, pers. comm., 2012; Faria Santos, pers. comm., 2012; Manning, pers. comm., 2013). Many of the specimens we observed did appear to exhibit some degree of plantar extension. Evidence from the trackway record indicates that extension of the pes orients the unguals so that digit I is directed anteriorly or weakly anterolaterally while the claw is held near vertically or with a slight medial cant, digit II is directed anterolaterally or weakly laterally while the claw is canted medially or strongly medially, and digit III is oriented strongly laterally while the claw is canted fully medially (Fig. 9.3). See Table 9.1 for track citations.

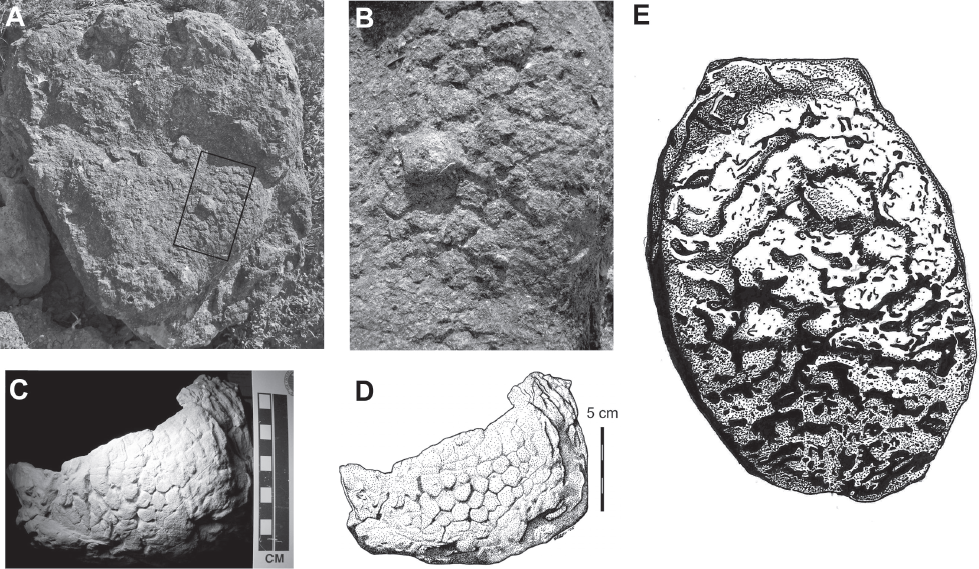

9.5. Sauropod natural track cast skin impressions. (A) Large sauropod pes cast from the Lourinhã Formation of Portugal exhibiting large (2–3 cm) tubercles. Box indicates position of details in B. (B) Close-up of plantar surface from A. Note the high relief between the large tubercle and the smaller “clusters” as well as the channels between them. (C) Natural cast and (D) shaded relief illustration of skin impressions on the plantar surface of a sauropod manus from the Morrison Formation. Modified from Platt and Hasiotis (2006). (E) Illustration of the plantar surface of a modern elephant pes; the rugose network of furrows, ridges, and pits enhance traction. Foot ~40 cm diameter.

DISCUSSION

Flexion-Traction-Control

The lack of any sauropod tracks that exhibit plantar flexion of claws into the substrate fails to provide support for the flexion-traction-control hypothesis. In tracks emplaced in quite wet sediments (described here and elsewhere in the literature), the digits are separated and extended anteriorly with the ungual of digit I oriented almost vertically, and digits II and III canted weakly to moderately medially (Figs. 9.4A, 9.4B). Furthermore, the most deeply emplaced portion of the pes is not the anterior end (where flexed unguals would be expected to have received force for flexion-traction-control), but the posteromedial margin, presumably where most of the force was actually focused during walking. This was observed consistently in nearly every track specimen examined for this study. There is no evidence to suggest that sauropods engaged plantar flexion in muddy sediment (as depicted in Figs. 9.4C, 9.4D); rather, the evidence shows they applied plantar extension, possibly to prevent lateral slipping, or torsion in the limb column. In some specimens, small ridges of sediment appear to be pushed up between the extended unguals, apparently due to minor amounts of outward pedal rotation during stepping (e.g., González Riga et al., 2014; Fig. 9.3A). This corroborates the extension-traction-control hypothesis (Gallup, 1989; Pittman, 1989; Pittman and Gillette, 1989; Bonnan, 2005), and when considered alongside the phylogenetic trend of pedal ungual hypertrophy and manual ungual loss, suggests that the unusual orientation of the unguals during plantar flexion may be an adaptation for a purpose other than locomotion in wet, muddy substrates. Phrased another way, why put off-road tires on the rear axle and bald tires on the forward axle of a four-wheel drive? Sauropod limbs are clearly adapted toward weight support. The columnar and relatively inflexible nature of the limbs probably limited the ability of sauropods to excavate nests, thus requiring another adaptation to aid the behavior.

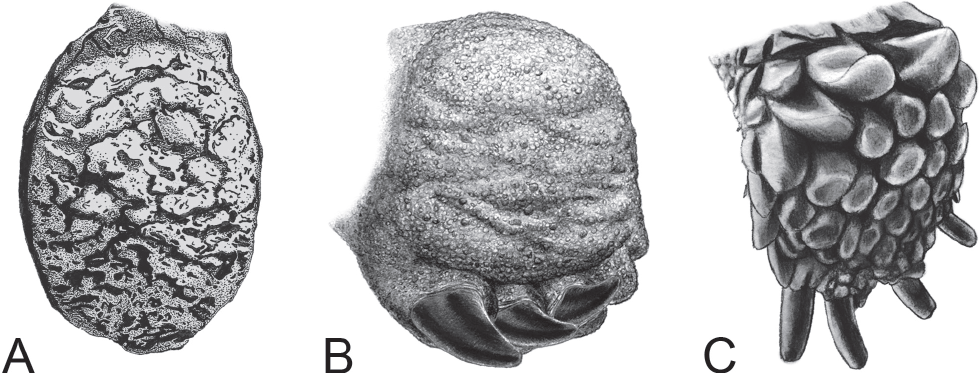

Substrate grip or traction in sauropods may have been enhanced by the rugose skin texture of both the palmar and plantar surfaces of the manus and pes (Figs. 9.5A–9.5D). Pedal and manual skin impressions have been reported as rugose, coarse, and composed of patterns of polygonal tubercles and scales from ~1 cm to 3 cm in diameter (Platt and Hasiotis, 2006; Mateus and Milàn, 2009; Marzola et al., 2014; Xing et al., 2015). Possible modern analogues occur on the plantar surfaces of elephant feet (Fig. 9.5E) whose thick keratinous pads are covered by a rugged network of furrows, pits, and ridges that aid in providing traction on an otherwise planar foot (Eltringham, 1982), as well as the feet of tortoises, which are covered and fringed with scales. However, we urge caution when drawing direct similarities between the feet of elephants and sauropods because they are only superficially similar (Fig. 9.6).

9.6. Comparison of pedal morphology in elephants, sauropods, and tortoises. (A) Ventral view of the plantar surface of a modern elephant pes from Figure 9.5E. (B) Ventral view life reconstruction of a sauropod right pes exhibiting plantar flexion; the laterally deflected, ventrally rotated unguals overlap, turning the broad lateral surfaces of the claws into a scraping blade; traction-enhancing scales and tubercles cover the plantar surface. Foot ~60 cm wide. (C) Oblique ventral view of the plantar surface of the right pes of the desert tortoise, Gopherus agassizii, in a neutral position. Under plantar flexion, the unguals would be drawn together to form a spade-like surface for removing sediment during nest excavation. Also note the rugged, tread-like texture created by the large, cylindrical scales on the plantar surface of the foot, separated by deep channels. Foot ~4 cm wide.

Miring-Avoidance

There is little evidence to suggest that sauropods’ unique pedal morphology and position during plantar flexion was functional in miring-avoidance. However, incidences of miring are quite commonly reported for sauropodomorphs (Dodson et al., 1980; Sander, 1992; Hungerbühler, 1998; Montgomery and Fiorillo, 2001; Fowler et al., 2003; Kirkland, pers. comm., 2012), and extended unguals may have helped prevent “postholing” entrapment of the pes by vacuum-like forces in muddy substrate. As extended claws gouged the sediment during the downward motion of the pes, these gouges could have provided channels for airflow, preventing suction entrapment by allowing air to freely circulate around the pes (Kirkland, pers. comm., 2012). This presents a plausible mechanism by which miring may be avoided via ungual extension in a way that is corroborated by track evidence and is potentially testable by the use of models. Plantar flexion during withdrawal of the foot may create a tapered profile, facilitating removal from sticky sediments in which miring is a potential hazard (Noto, pers. comm., 2014). However, the “tapering” scenario would likely require plantar flexion, thus leaving a distinct impression within a track, for which there is no evidence.

Flexion

The hypotheses presented so far do not provide a functional explanation for the unusual rotation and orientation of unguals during flexion (Bonnan, 2005). Pittman (1989; pers. comm., 2012) suggested that for tracks emplaced in “firmer substrates” the claws were “wrapped around the lateral margin of the foot” (especially so in firm, slippery substrates such as microbial mudflats [Marty, pers. comm., 2013]); this is closer to the null or neutral position, but it still does not involve plantar flexion. However, it is possible that plantar flexion was used for grip in conditions that did not preserve tracks, such as poorly indurated, coarse-grained substrates. This is indirectly testable by comparison to the similarly shaped unguals of extant tortoises (such as Gopherus; Fowler and Hall, 2011). Plantar flexion of the feet of tortoises positions the unguals to create a hoe-like shape, which is very similar to that hypothesized for sauropods (Bonnan, 2005). Thus, tortoises placed on a loose gravelly substrate could be observed to see whether flexion is used to grip the surface for locomotion. Although this potential behavior remains to be tested, tortoises have been observed using plantar-flexed hind (and fore-)limbs to excavate sediment for nests and burrows where flexion draws the claws together to aid in scraping up sediment (Bramble, 1982; Fowler and Hall, 2011). We maintain that the plantar-flexed pedal unguals of sauropods could have been utilized in a similar fashion, for scratch-digging nests as originally hypothesized by Gallup (1989). This is corroborated by fossil nest excavations attributed to titanosauriform sauropods (e.g., Chiappe et al., 2005; Vila et al., 2010) that clearly show elongated, trough-like margins that would have been excavated by the pedal unguals employing plantar flexion.

CONCLUSIONS

Evidence from trackways provides support for a suite of functions for sauropod unguals, similar to the original suggestion of Gallup (1989) and later Bonnan (2005). Although we failed to find support for the miring-avoidance hypothesis of Bonnan (2005), support is found for the extension-traction-control hypothesis of Pittman (1989; and others). Currently, there is no evidence of plantar flexion being employed during walking, so the suggestion that substrate grip was a potential function of the unusual unguals and plantar flexion posture remains unsupported. In contrast, plantar flexion of the digits is used by extant tortoises to make a hoe-shape of the foot for use in digging, and ichnological evidence suggests that at least titanosauriform sauropod feet were used to excavate nesting structures (e.g., Vila et al., 2010; Fowler and Hall, 2011). Therefore, we conclude that there is currently no evidence to support a traction control function, but there is evidence to support a scratch-digging nest-excavation function.

This study provides an example where the rich trackway fossil record can be used to test functional hypotheses. Although substrate features are part of this study, more detailed investigation into the specific traits of soft, muddy substrates (water content, thickness, sedimentology, and so on) and their relationship with the use of unguals during plantar extension (degree of “spread” between claws, consistency of cant angles, etc.) would be informative to better understanding sauropod locomotion behaviors. We encourage ichnologists to continue to record and publish in detail (especially clear, high-resolution photographs and photogrammetry or other three-dimensional data techniques) any evidence of ungual-substrate interaction as such information is indispensable and essential for conducting proper paleobiological analyses.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We are tremendously grateful to the following people for their time and sharing of data, without whose generous contributions this research would not have been possible: A. Richter and T. van der Lubbe (Niedersächsisches Landesmuseum Hannover); J. Farlow (Indiana University, Fort Wayne); O. Mateus (Universidade Nova de Lisboa, Portugal); J. Pittman; V. F. Dos Santos (Museu Nacional de Historia Natural e da Ciência, Portugal); C. Coutinho (Portugal); D. Marty (Office de la culture: Paleontology A16, Switzerland); B. Platt (University of Kansas, Lawrence); J. Phillips and B. Phillips (Dinosaur Farm Museum, Isle of Wight); M. Green and K. Simmonds (Isle of Wight); M. Lockley (University of Colorado, Denver); L. Chiappe (Natural History Museum of Los Angeles County); P. Manning (The University of Manchester, England); J. Milàn (Geomuseum Faxe, Denmark); P. Mannion (Imperial College London); D. Loope (University of Nebraska, Lincoln); T. Martin (Emory University, Atlanta); B. Breithaupt (Bureau of Land Management, Wyoming), A. Enniouar (Université Chouaib Doukkali, Morocco), and D. Varricchio (Montana State University, Bozeman), and A. Farke (Raymond Alf Museum of Paleontology, California). Thanks to J. Horner and the Museum of the Rockies for funding and support. Support for the Museum of the Rockies graduate student fund was provided by D. Waggoner and D. Sands. Thanks to T. Martin and R. Boessenecker for helpful discussion. Reviews by C. Noto, S. Lucas, and D. Marty are appreciated and improved this manuscript. Elephant foot figure by A. Fragomeni. Sauropod and Gopherus pes restoration by L. Hall. Finally, we wish to express our thanks to the editors of this volume for their patience, enthusiasm, and no doubt countless hours spent wrangling and assembling manuscripts from researchers across the globe.

REFERENCES

Ahmed, A. A. K., T. Lingham-Soliar, and T. Broderick. 2004. Giant sauropod tracks from the Middle-Late Jurassic of Zimbabwe in close association of theropod tracks. Lethaia 37(4): 467–470.

Auffenberg, W. 1976. The genus Gopherus (Testudinidae): pt I. Osteology and relationships of extant species. Bulletin of the Florida State Museum Biological Sciences 20: 47–110.

Bilbey, S. A., D. L. Mickelson, J. E. Hall, K. Scott, C. Todd, and J. I. Kirkland. 2005. Vertebrate Ichnofossils from the Upper Jurassic Stump to Morrison Formational Transition-Flaming Gorge Reservoir, UT. Geological Society of America Abstracts with Programs 37(6): 12.

Bonaparte, J. F. 1986. The dinosaurs (Carnosaurs, Allosaurids, Sauropods, Cetiosaurids) of the middle Jurassic of Cerro Cóndor (Chubut, Argentina). Annales de Paléontologie (Vert.-Invert.) 72(4): 325–386.

Bonnan M. F. 2005. Pes anatomy in sauropod dinosaurs: implications for functional morphology, evolution, and phylogeny; pp. 346–380 in V. Tidwell and K. Carpenter (eds.), Thunder-Lizards: The Sauropodomorph Dinosaurs. Indiana University Press, Bloomington, Indiana.

Bramble, D. M. 1982. Scaptochelys: generic revision and evolution of gopher tortoises. Copeia 1982(4): 852–867.

Castanera, D., C. Pascual, J. I. Canudo, N. Hernandez, and J. L. Barco. 2012. Ethological variations in gauge in sauropod trackways from the Berriasian of Spain. Lethaia 45: 476–489.

Chiappe, L. M., F. Jackson, R. A. Coria, and L. Dingus. 2005. Nesting titanosaurs from Auca Mahuevo and adjacent sites; pp. 285–302 in K. C. Rogers and J. Wilson (eds.), The Sauropods: Evolution and Paleobiology. University of California Press, Berkeley, California.

Dodson, P., A. K. Behrensmeyer, R. T. Bakker, and J. S. Mcintosh. 1980. Taphonomy and paleoecology of the dinosaur beds of the Jurassic Morrison Formation. Paleobiology 6: 208–232.

Eltringham, S. K. 1982. Elephants. Blandford Press, London, U.K., 262 pp.

Enniouar, A., L. Abdelouahed, and A. Habib. 2014. A Middle Jurassic sauropod tracksite in the Argana Basin, Western High Atlas, Morocco: an example of paleoichnological heritage for sustainable geotourism. Proceedings of the Geologists’ Association 125: 114–119.

Farlow, J. O., J. G. Pittman, and J. M. Hawthorne. 1989. Brontopodus birdi, Lower Cretaceous sauropod footprints from the U.S. Gulf Coastal Plain; pp. 372–394 in D. D. Gillette and M. G. Lockley (eds.), Dinosaur Tracks and Traces. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, UK.

Farlow, J. O., M. O’Brien, G. J. Kuban, B. F. Dattilo, K. T. Bates, P. L. Falkingham, L. Pinuela, A. Rose, A. Freels, C. Kumagai, C. Libben, J. Smith, and J. Whitcraft. 2012. Dinosaur tracksites of the Paluxy River Valley (Glen Rose Formation, Lower Cretaceous), Dinosaur Valley State Park, Somervell County, Texas; pp. 41–69 in P. Huerta and F. Torcida (eds.), Actas de V Jornadas Internacionales sobre Paleontolgia de Dinosaurios y su Entorno, Salas de los Infantes, Burgos.

Ferrusquía-Villafranca, E., E. Jiménez-Hidalgo, and V. M. Bravo-Cuevas. 1996. Footprints of small sauropods from the Middle Jurassic of Oaxaca, southeastern Mexico. Continental Jurassic: Museum of Northern Arizona Bulletin 60: 119–126.

Fowler, D. W., and L. E. Hall. 2011. Scratch-digging sauropods, revisited. Historical Biology 23(1): 27–40.

Fowler, D. W., K. Simmonds, M. Green, and K. A. Stevens. 2003. The taphonomic setting of two mired sauropods (Wessex Fm, Isle of Wight, UK): palaeoecological implications and taxon preservation bias in a Lower Cretaceous wetland. Journal of Vertebrate Palaeontology 23(3, Abstracts volume): 51A.

Gallup M. R. 1989. Functional morphology of the hindfoot of the Texas sauropod Pleurocoelus sp. indet. in J. O. Farlow (ed.), Paleobiology of the Dinosaurs. Geological Society of America Special Paper 238: 71–74.

Gatesy, S. M., K. M. Middleton, F. A. Jenkins, and N. H. Shubin. 1999. Three-dimensional preservation of foot movements in Triassic theropod dinosaurs. Nature 399(6732): 141–143.

González Riga, B. J., D. Ortiz, L. D. Tomaselli, R. Candeiro, J. P. Coria, and M. Pramparo. 2014. Sauropod and theropod dinosaur tracks from the Upper Cretaceous of Mendoza (Argentina): trackmakers and anatomical evidences. Journal of South American Earth Sciences 61: 134–141. doi: 10.1016/j.jsames.2014.11.006.

Hildebrand M., 1985. Digging of quadrupeds; pp. 89–109 in M. Hildebrand, D. M. Bramble, K. F. Liem, and D. B. Wake (eds.), Functional Vertebrate Morphology. Harvard University Press, Cambridge, Massachusetts.

Hungerbühler, A. 1998. Taphonomy of the prosauropod dinosaur Sellosaurus, and its implications for carnivore faunas and feeding habits in the Late Triassic. Palaeogeography, Palaeoclimatology, Palaeoecology 143: 1–29.

Ibrahim, N., D. J. Varricchio, P. C. Sereno, J. A. Wilson, D. B. Dutheil, D. M. Martill, L. Baidder, and S. Zouhri. 2014. Dinosaur footprints and other ichnofauna from the Cretaceous Kem Kem beds of Morocco. PLoS One 9(3): e90751.

Langston Jr., W. 1974. Nonmammalian Comanchean tetrapods. Geoscience and Man (8): 77–102.

Lockley, M. G., and A. P. Hunt. 1995. Ceratopsid tracks and associated ichnofauna from the Laramie Formation (Upper Cretaceous: Maastrichtian) of Colorado. Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology 15(3): 592–614.

Lockley, M. G., J. O. Farlow, and C. A. Meyer. 1994. Brontopodus and Parabrontopodus ichnogen. nov. and the significance of wide-and narrow-gauge sauropod trackways. Gaia 10: 135–145.

Lockley, M. G., B. H. Young, and K. Carpenter. 1983. Hadrosaur locomotion and herding behavior: evidence from footprints in the Mesaverde Formation, Grand Mesa Coal Field, Colorado. Mountain Geologist 20: 5–14.

Marzola, M., O. Mateus, A. Schulp, L. Jacobs, M. Polcyn, and V. Pervov. 2014. Early Cretaceous tracks of a large mammaliamorph, a crocodylomorph, and dinosaurs from an Angolan diamond mine. Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology 36 (Abstracts volume): 181.

Mateus, O., and J. Milàn. 2009. A diverse Upper Jurassic dinosaur ichnofauna from central-west Portugal. Lethaia 43(2): 245–257.

Matsukawa, M., T. Matsui, and M. G. Lockley. 2001. Trackway evidence of herd structure among ornithopod dinosaurs from the Cretaceous Dakota Group of northeastern New Mexico, U.S.A. Ichnos 8(3–4): 197–206.

Milàn, J., P. Christiansen, and O. Mateus. 2005. A three-dimensionally preserved sauropod manus impression from the Upper Jurassic of Portugal: implications for sauropod manus shape and locomotor mechanics. Kaupia 14: 47–52.

Milner, A. R., J. D. Harris, M. G. Lockley, J. I. Kirkland, and N. A. Matthews. 2009. Bird-like anatomy, posture, and behavior revealed by an Early Jurassic theropod dinosaur resting trace. PloS One 4(3): e4591.

Montgomery, H., and A. Fiorillo. 2001. Depositional setting and paleoecological significance of a new sauropod bonebed in the Javelina Formation (Cretaceous) of Big Bend National Park, Texas. Geological Society of America, Abstracts with Programs 33: 196.

Moratalla, J. J. 2009. Sauropod tracks of the Cameros Basin (Spain): Identification, trackway patterns and changes over the Jurassic-Cretaceous. Geobios 42(6): 797–811.

Moratalla, J. J., J. García-Mondéjar, V. F. Santos, M. G. Lockley, J. L. Sanz, and S. Jiménez. 1994. Sauropod trackways from the Lower Cretaceous of Spain. Gaia 10: 75–84.

Pittman, J. G. 1989. Stratigraphy, lithography, depositional environment, and track type of dinosaur trackbearing beds of the Gulf Coastal plain; pp. 135–154 in D. D. Gillette and M. G. Lockley (eds.), Dinosaur Tracks and Traces. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, UK.

Pittman, J. G., and D. D. Gillette. 1989. The Briar site: a new sauropod dinosaur tracksite in Lower Cretaceous beds of Arkansas, USA.; pp. 313–332 in D. D. Gillette and M. G. Lockley (eds.), Dinosaur Tracks and Traces. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, UK.

Platt, B. F., and S. T. Hasiotis. 2006. Newly discovered sauropod dinosaur tracks with skin and foot-pad impressions from the Upper Jurassic Morrison Formation, Bighorn Basin, Wyoming, USA. Palaios 21(3): 249–261.

Romano, M., M. A. Whyte, and P. L. Manning. 1999. New sauropod dinosaur prints from the Saltwick Formation (Middle Jurassic) of the Cleveland basin, Yorkshire. Proceedings of the Yorkshire Geological Society 52(4): 361–369.

Ruby, D. E., and H. A. Niblick. 1994. A behavioral inventory of the desert tortoise: development of an ethogram. Herpetological Monograph 8: 88–102.

Sander, P. M. 1992. The Norian Plateosaurus bonebeds of central Europe and their taphonomy. Palaeogeography, Palaeoclimatology, Palaeoecology 93(3): 255–299.

Sander, P. M., A. Christian, M. Claus, R. Fechner, C. T. Gee, E. M. Griebeler, and U. Witzel. 2010. Biology of the sauropod dinosaurs: the evolution of gigantism. Biological Reviews 86(1): 177–155.

Thomas, D. A., and J. O. Farlow. 1997. Tracking a dinosaur attack. Scientific American 277(6): 74–79.

Thulborn, R. A., and M. Wade. 1984. Dinosaur trackways in the Winton Formation (mid-Cretaceous) of Queensland. Memoirs of the Queensland Museum 21(2): 413–517.

Varricchio, D. J. 2011. A distinct dinosaur life history? Historical Biology 23(1): 91–107.

Vila, B., F. D. Jackson, J. Fortuny, A. G. Sellés, and À. Galobart. 2010. 3-D modeling of megaloolithid clutches: insights about nest construction and dinosaur behaviour. PLoS One 5(5): e10362.

Wilson, J. A., and M. T. Carrano. 1999. Titanosaurs and the origin of ‘wide-gauge’ trackways: a biomechanical and systematic perspective on sauropod locomotion. Paleobiology 25(2): 252–267.

Wright, J. 2005. Steps in understanding sauropod biology; pp. 252–284 in K. C. Rogers and J. Wilson (eds.), The Sauropods: Evolution and Paleobiology. University of California Press, Berkeley, California.

Xing, L., D. Li, M. Lockley, D. Marty, J. Zhang, W. S. Persons, H. You, C. Peng, and S. B. Kummell. 2014. Dinosaur natural track casts from the Lower Cretaceous Hekou Group in the Lanzhou-Minhe Basin, Gansu, northwest China: Ichnology, track formation, and distribution. Cretaceous Research 52: 194–205.

SUPPLEMENTAL INFORMATION: SPECIMEN DESCRIPTIONS

Morphotype 1 pes track from Agua del Choque track site level An-1 – Anacleto Formation, Late Cretaceous, Argentina

Description: Impressions of digits I–IV and the unguals of I–III are well preserved. The pes was shallowly emplaced in soft, silty mud. The unguals of digits I, II, and III are anterolaterally directed and are canted slightly medially. Shallow pressure ridges appear to have formed in the substrate on the lateral margins of the unguals. The plantar surface of the pes is asymmetrically loaded along the medial and posterior margins.

Brooklyn College from West Bank Bird Site Trackway S4 – Glen Rose Formation, Early Cretaceous, United States

Description: Impressions of digits I–IV and the unguals of I–III are well preserved. The pes was deeply emplaced in soft mud. The ungual of digit I is anteriorly directed; the ungual of digit II is somewhat laterally directed; and digit III laterally directed. Digit I is nearly vertical; digit II is canted slightly medially; and digit III is canted strongly medially. The plantar surface is asymmetrically loaded along the medial and posterior margins.

Brontopodus Small sauropod sequence track 1 – Glen Rose Formation, Early Cretaceous, United States

Description: Impressions of digits I–IV and the unguals of I–III are well preserved. The pes was moderately deeply emplaced in soft mud. The ungual of digit I is anterolaterally directed; the ungual of digit II is somewhat laterally directed; and digit III is laterally directed. Digit I is nearly vertical; digit II is canted slightly medially; and digit III is canted strongly medially. The plantar surface is asymmetrically loaded along the medial and posterior margins.

Brontopodus Small sauropod sequence track 2 – Glen Rose Formation, Early Cretaceous, United States

See Figures 9.3A, 9.3B.

Description: Impressions of digits I–IV and the unguals of I–III are well preserved. The pes was moderately deeply emplaced in soft mud. The ungual of digit I is anterolaterally directed; the ungual of digit II is somewhat laterally directed; and digit III is laterally directed. Digit I is nearly vertical; digit II is canted slightly medially; and digit III is canted strongly medially. The plantar surface is asymmetrically loaded along the medial and posterior margins.

Brontopodus Small sauropod sequence track 3 – Glen Rose Formation, Early Cretaceous, United States

See Figure 9.3A, 9.3B.

Description: Impressions of digits I–IV and the unguals of I–III are well preserved. The pes was moderately deeply emplaced in soft mud. The ungual of digit I is anteriorly directed; the ungual of digit II is anterolaterally directed; and digit III is laterally directed. Digit I is vertical; digit II is canted slightly medially; and digit III is canted strongly medially. The plantar surface is asymmetrically loaded along the medial and posterior margins.

Brontopodus Left manus-pes set – Glen Rose Formation, Early Cretaceous, United States

See Figure 9.4A.

Description: Impressions of digits I–IV and the unguals of I–III are well preserved. The pes was deeply emplaced in soft mud. The ungual of digit I is anterolaterally directed; the ungual of digit II is somewhat laterally directed; and digit III is laterally directed. Digit I is vertical; digit II is canted slightly medially; and digit III is canted strongly medially. The plantar surface is asymmetrically loaded along the medial and posterior margins.

S2M and pes cast; S2W – Glen Rose Formation, Early Cretaceous, United States

For S2M, see Figures 9.4C, 9.4D.

Description: Impressions of digits I–IV and the unguals of I–III are well preserved. The pes was deeply emplaced into soft mud. The unguals are anterolaterally directed with digits I and II canted slightly medially. The plantar surface is asymmetrically loaded along the medial and posterior margins.

S2N and pes cast; S2S; S2U – Glen Rose Formation, Early Cretaceous, United States

Description: Impressions of digits I–III and the unguals of I–II are well preserved. The pes was deeply emplaced into soft mud. The unguals are anterolaterally directed with digits I and II canted slightly medially. The plantar surface is asymmetrically loaded along the medial and posterior margins.

S2O; S2P – Glen Rose Formation, Early Cretaceous, United States

Description: Impressions of digits I–III and the unguals of I–III are well preserved. The pes was deeply emplaced into soft mud. The unguals are anterolaterally directed with digits I and II canted slightly medially and digit III more medially. The plantar surface is asymmetrically loaded along the medial and posterior margins.

S2T – Glen Rose Formation., Early Cretaceous, United States

Description: Impressions of digits I–III and the unguals of I–II are well preserved. The pes was deeply emplaced into soft mud. The unguals are anterolaterally directed with digits I and II canted slightly medially. The plantar surface is asymmetrically loaded along the medial and posterior margins. The medial displacement rim is overprinted by a tridactyl pes.

S2Q and pes cast; S2V – Glen Rose Formation, Early Cretaceous, United States

Description: Impressions of digits I–IV and the unguals of I–III are well preserved. The pes was deeply emplaced in soft mud. The ungual of digit I is anteriorly directed; the ungual of digit II is somewhat laterally directed; and digit III is laterally directed. Digit I is vertical; digit II is canted slightly medially; and digit III is canted strongly medially. The plantar surface is asymmetrically loaded along the medial and posterior margins.

S2R and pes cast – Glen Rose Formation, Early Cretaceous, United States

Description: The impression of digits I–IV and the ungual of digit I is well preserved. The plantar surface between digits II and III is overprinted by a theropod track, which distorts the sauropod ungual morphology. The pes was deeply emplaced in soft mud. The ungual of digit I is deeply impressed, anteriorly directed, and vertically oriented. The plantar surface is asymmetrically loaded along the medial and posterior margins.

LCU-I-37-12p – Huérteles Formation., Early Cretaceous, Soria, Spain (see Castanera et al., 2012:fig. 4A)

See Figures 9.3G, 9.3H.

Description: Digits I–IV and the unguals of I–III are well preserved. The pes was deeply emplaced in soft mud. The ungual of digit I is anterolaterally directed; the ungual of digit II is moderately laterally directed; and digit III is laterally directed. Digit I is canted medially, and digits II and III are canted strongly medially. The plantar surface is asymmetrically loaded along the medial and posterior margins.

Dinosaur Farm Titanosaurid sauropod pes natural track cast – Wessex Formation, Early Cretaceous, Isle of Wight, United Kingdom; Pes Cast 122.88 – Summerville Formation; Middle Jurassic, Arizona, United States

For Titanosaurid, see Figures 9.3I, 9.3J; for 122.88, see Figures 9.3E, 9.3F.

Description: Digits I–III and the unguals of I–III are well preserved. The pes was moderately deeply emplaced into soft mud. The unguals of digits I and II are anterolaterally directed, and the ungual of digit III is laterally directed. Digits I and II are near vertical, and digit III is canted medially. The plantar surface is asymmetrically loaded along the medial and posterior margins.

Praia das Gentias pes track – Lourinhã Formation, Praia das Gentias, Late Jurassic, Portugal

See Figure 9.4B.

Description: Digits I–IV and the unguals of I–III are well preserved. The pes was moderately deeply emplaced in soft mud. The ungual of digit I is anterolaterally directed, and the unguals of digits II and III are laterally directed. Digit I is nearly vertical; digit II is canted medially; and digit III is canted strongly medially. The plantar surface is asymmetrically loaded along the medial and posterior margins.

Large sauropod pes natural track cast – Lourinhã Formation, Late Jurassic, Portugal

Description: Digits I–III and the unguals of I–III are well preserved. The pes was moderately deeply emplaced in soft mud. The ungual of digit I is anterolaterally directed; the ungual of digit II is somewhat laterally directed; and digit III laterally directed. Digit I is canted medially, and digits II and III are canted strongly medially. The plantar surface is asymmetrically loaded along the medial and posterior margins.

Large sauropod pes natural track cast with skin – Lourinhã Formation, Late Jurassic, Portugal

See Figures 9.5A, 9.5B.

Description: Digits I–IV and the unguals of I–III are well preserved. The pes was deeply emplaced in soft mud. The ungual of digit I is anteriorly directed; the ungual of digit II is anterolaterally directed; and digit III laterally directed. Digit I is vertical; digit II is canted medially; and digit III is canted strongly medially. Scale and tubercle impressions are present on the heel. The plantar surface is asymmetrically loaded along the medial and posterior margins.

CTD-TCH-1014-S4-LP4; CTD-TCH-1000-S9-LP5; CTD-BSY-1015-S2-LP3; CTD-BSY-1015-S2-RP3 – Reuchenette Formation, Late Jurassic, Jura Canton, Switzerland

Description: Digits I–IV and the unguals of I–III are well preserved. The pes was shallowly emplaced in a microbial mud mat. The ungual of digit I is anterolaterally directed, and the unguals of digits II and III are laterally directed. Digit I is nearly vertical; digit II is canted medially; and digit III is canted strongly medially. The plantar surface appears evenly loaded.

Morphotype 1 pes natural track cast – Morrison Formation, Late Jurassic, United States

Description: Digits I–IV are preserved. Details of the unguals are not preserved. The pes was deeply emplaced in soft mud. Digit I is anterolaterally directed; digit II is laterally directed; and digit III posterolaterally directed. Long (~10 cm) vertical scour marks are associated with the tips of digits II–IV.

CU 194-2/LACM 15499 Brontopodus pes track cast – Morrison Formation, Late Jurassic, Utah, United States

See Figures 9.3C, 9.4D.

Description: Digits I–III and the unguals of I–III are well preserved. The pes was moderately deeply emplaced in soft mud. The ungual of digit I is anterolaterally directed; the ungual of digit II is moderately laterally directed; and digit III laterally directed. Digit I is canted slightly medially, and digits II and III are canted strongly medially. The plantar surface is asymmetrically loaded along the medial and posterior margins.

Morphotype A pes cast – Saltwick Formation, Late Jurassic, England

Description: Digits I–IV and the unguals of digits I–II are preserved. The pes was deeply emplaced in soft mud. The ungual of digit I is anterolaterally directed; the ungual of digit II is somewhat laterally directed; and digit III laterally directed. Digit I is nearly vertical; digit II is canted medially; and digit III is canted strongly medially. The plantar surface is asymmetrically loaded along the medial and posterior margins.

?Morphotype B pes cast 1 – Saltwick Formation, Late Jurassic, England

Description: Digits I–II and the unguals of I–II are well preserved. The pes was deeply emplaced into soft mud. The ungual of digit I is anterolaterally directed, and the ungual of digit II is laterally directed. Digit I is canted medially, and digit II is canted strongly medially.

Morphotype B pes cast 2 – Saltwick Formation, Late Jurassic, England

Description: Digits I–IV and the unguals of digits I–III are well preserved. The pes was moderately shallowly emplaced into soft mud. The unguals of digits I and II are anterolaterally directed, and the ungual of digit III is laterally directed. Digit I is canted medially, and digits II and III are canted strongly medially.

UCRC I 173 Natural pes track cast – Kem Kem Beds, Late Cretaceous, Er Remlia, Morocco

Description: Digits I–IV and the unguals of I and II are well preserved. The pes was deeply emplaced (~38 cm) in soft mud. Digit I is anterolaterally directed; digit II is strongly anterolaterally directed; and digit III appears laterally directed. Very long (~30 cm) subvertical scour marks are associated with the tips of digits I and II. Unguals of digits I and II are canted slightly medially, and digit III is incomplete. The plantar surface appears asymmetrically loaded along the medial margin.

CDUE Locality 100 Right pes track – Amiskoud Formation, Early Middle Jurassic, Tafaytour, Morocco

Description: Impressions of digits I–IV and the unguals of I–III are well preserved. The ungual of digit I is anterolaterally directed, the ungual of digit II is somewhat laterally directed and digit III is strongly laterally directed. The angular orientation of the unguals is not clearly discernable, though they do appear to have contacted the substrate in at least a subvertical position. The plantar surface of the pes is asymmetrically loaded along the medial and posterior margins, with a mediolaterally directed slide scour close to 20 cm long off the anteromedial portion of the track.