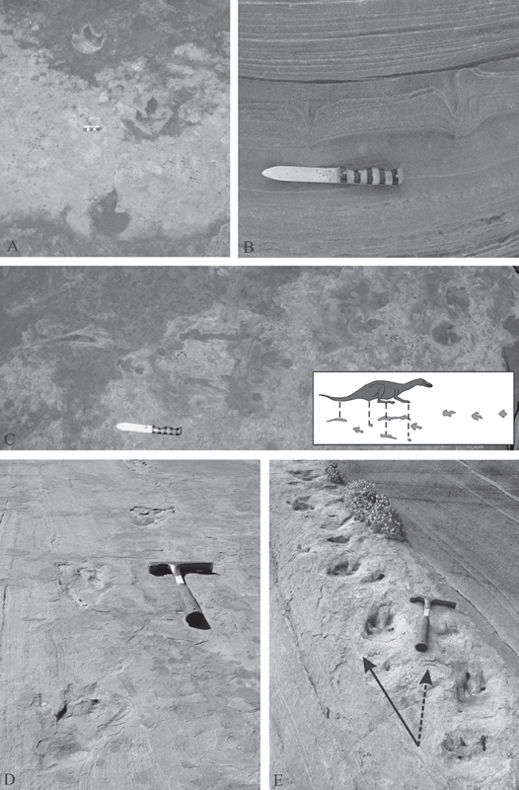

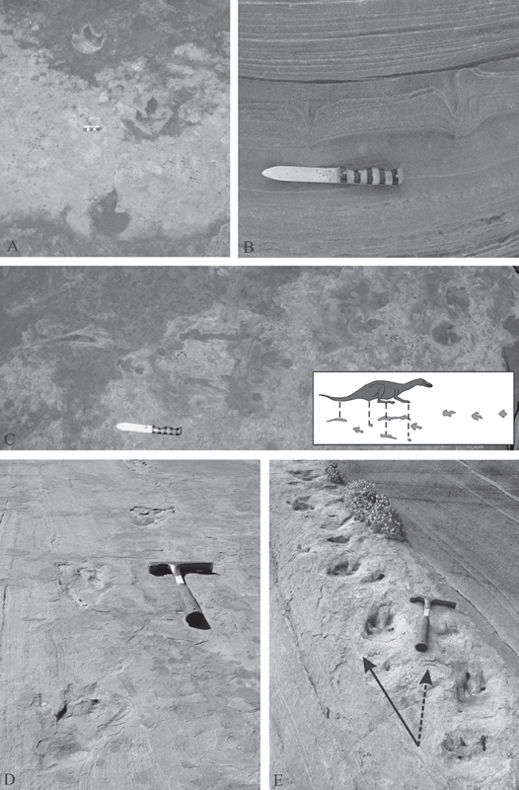

18.1. Dinosaur tracks in the Navajo Sandstone at Coyote Buttes, Utah. (A) Tracks of small theropod dinosaurs on the upper surface of an eolian grain flow (layer deposited by avalanching dry sand on the steep, downwind slope of a sand dune). (B) Close-up of dinosaur tracks in cross-section. Notice how the sharp digits have penetrated several layers of sand. Strata slope downward away from viewer. (C) Trackway of a crouching theropod on a dune slope, with interpretative drawing inset (from Milàn, Loope, and Bromley, 2008). (D) Otozoum trackway on a firm, wind-rippled interdune surface. (E) Trackway of sauropodomorph dinosaur adopting a sideways walking gait for the first part of the trackway. The later (upper) part shows that the animal then started moving directly up the slope. The solid arrow shows the direction of progression and the dashed arrow indicates the orientation of the animal’s body.

Dinosaur Tracks in Eolian Strata: New Insights into Track Formation, Walking Kinetics, and Trackmaker Behavior |

18 |

David B. Loope and Jesper Milàn

DINOSAUR TRACKS ARE ABUNDANT IN WIND-BLOWN Mesozoic deposits, but the nature of loose eolian sand makes it difficult to determine how they are preserved. This also raises the questions: Why would dinosaurs be walking around in dune fields in the first place? And, if they did go there, why would their tracks not be erased by the next wind storm?

INTRODUCTION

Most dunes today form only in deserts and along shorelines – the only sandy land surfaces that are nearly devoid of plants. Normally plants slow the wind at the ground surface enough that sand will not move even when the plant cover is sparse. However, some dunes, such as the Great Sand Dunes of Colorado, form in semiarid areas where deflation combines with local wind corridors to permit accumulations that cover otherwise vegetated areas. Because animals are totally dependent on plants as an energy source, it might seem that dunes would be a poor place to look for animal tracks. A short walk in a modern dune field when the sun is low and shadows are long will demonstrate that this is not the case. The scarcity of life in dune fields is actually a boon for generating distinct, recognizable tracks. In the Nebraska Sand Hills (a giant dune field in central North America), the now stabilized, grass-covered dunes are at present traversed by huge numbers of cattle, but none of their tracks will get preserved. However, thin, 800-year-old cross-beds inside the dunes were deposited while the region was a howling desert and contain large numbers of distinct bison tracks and trackways (Loope, 1986). The scarcity of trackmakers prevented bioturbation (complete mixing of the sediment), thereby allowing full, three-dimensional preservation of the tracks and the trackways that did get made by the relatively small number of animals inhabiting or traversing the dunes. The hooves of the bison deformed soft, laminated sediment – the perfect medium to preserve recognizable tracks. The next windstorm buried the tracks. Today, the thick cover of grasses protects the land surface so well that there are no soft, laminated sediments for cattle to step on. And, if any tracks were, somehow, to get formed, no moving sediment would be available to bury them. Mesozoic eolian sediments around the world, which have been the focus of a number of case studies in recent years, preserve the tracks of dinosaurs that walked on actively migrating sand dunes. This chapter summarizes the known occurrences of dinosaur tracks in Mesozoic eolian strata and discusses their unique modes of preservation and the anatomical and behavioral information about the trackmakers that can be deduced from them.

TRACKS IN DEPOSITS OF LOWER JURASSIC DUNES, NAVAJO SANDSTONE, UTAH, UNITED STATES

The Early Jurassic Navajo Sandstone is a thick, widespread sedimentary layer on the Colorado Plateau of Utah and Arizona. The sandstone and its correlative strata, the Nugget Sandstone, have preserved more than 60 sites with dinosaur tracks and trackways (e.g., Lockley, Hunt, and Meyer, 1994; Rainforth and Lockley, 1996a, 1996b; Milàn, Loope, and Bromley, 2008; Lockley, 2011a, 2011b; Lockley et al., 2011), and a sparse but diverse vertebrate fauna comprising tritylodonts, crocodylomorphs, and dinosaurs (Irmis, 2005).

The Navajo Sandstone was deposited by large sand dunes that migrated southward along the subsiding, western coast of Pangaea. The sloping layers (cross-beds) deposited by the migrating dunes contain thousands of tracks of small theropod dinosaurs. Many of these tracks are preserved in dry avalanches (grain flows) that were deposited at the angle of repose of dry sand (about 32°). In a few places, it is possible to see many three-toed tracks on the upper surface of a single sandstone layer (Fig. 18.1A). Many more tracks, however, can be seen only in vertical cross-section (Loope and Rowe, 2003; Loope, 2006) (Fig. 18.1B). When viewed in cross-section, the preserved track has a U or W shape, with the top-most portion cut off by erosion. Apparently, when these animals stepped on the steep dune slopes, they created small, thin avalanches of dry sand, initiating from above the track. As an animal traversed the dune slope, each step was onto the sliding sand that it triggered by its previous step. The end result is that different tracks within the same animal’s trackway are sometimes preserved in different layers of sand, giving the false impression that the tracks are emplaced at different times and not by the same animal. As each avalanche buried a track, it eroded down into the tracked surface. The tracks of very small animals did not penetrate deeply into the dune slope, so many probably were completely eroded. The theropods, although small by dinosaur standards, were sufficiently large that they deformed the layered sand deeply enough (about 10 cm) so that most of the track (but not all) escaped erosion.

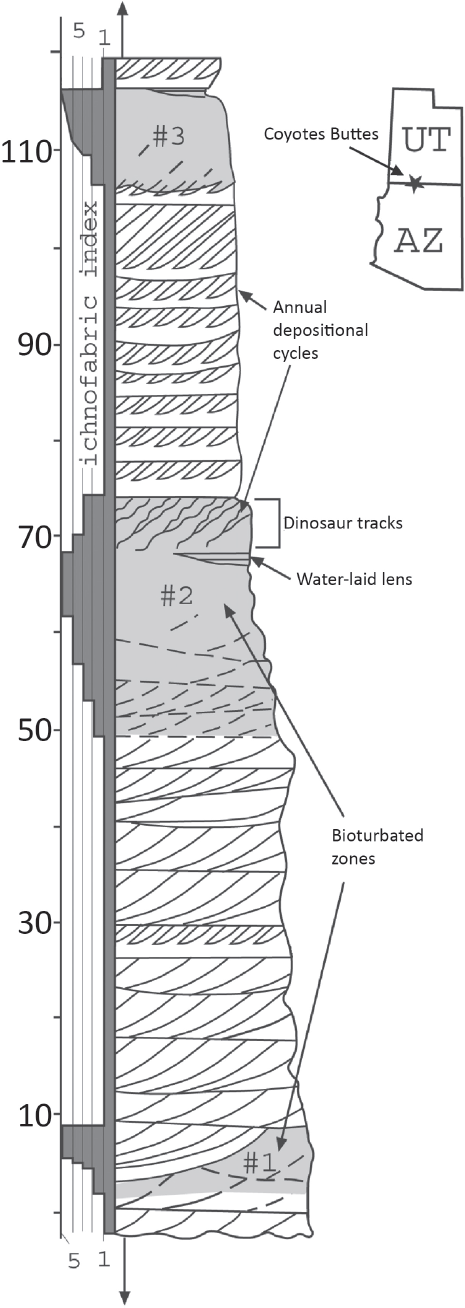

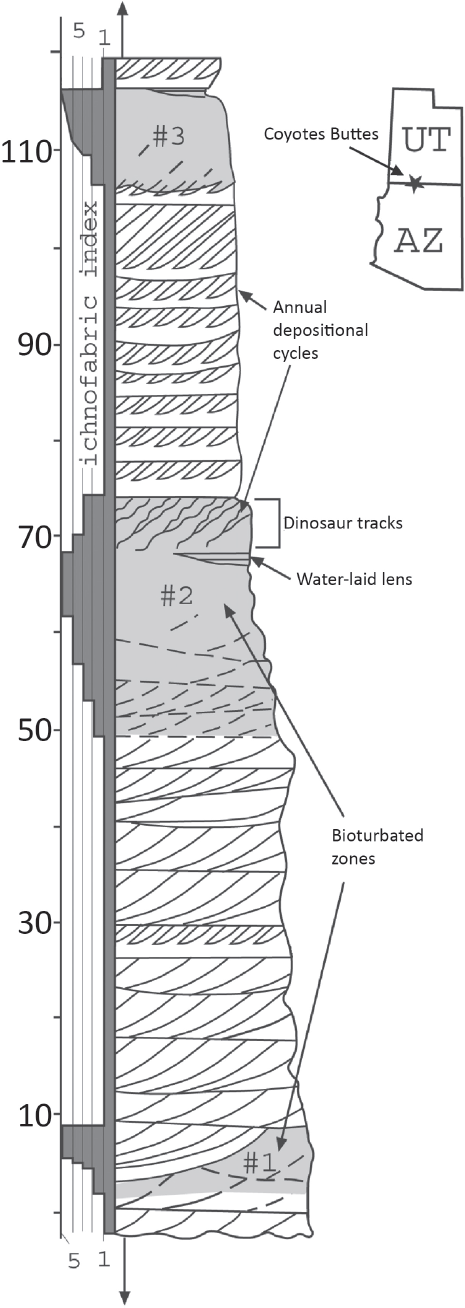

18.2. Stratigraphic column showing the distribution of tracks and burrows in the Lower Jurassic Navajo Sandstone. Tracks are restricted to one interval, but the burrows indicate there were three time periods when sufficient moisture was present in the dune field to support abundant life.

Theropod tracks are not the only signs of life in the Jurassic dune deposits. There are also abundant, small burrows, and surface trails made by insects or other invertebrates (Fig. 18.2). Theropods likely fed on the burrowers, but it is a mystery what the burrowers ate. There are no traces of rooted plants in the vicinity of the tracks, and very few in the whole formation. The three intervals containing abundant traces of animal life record relatively wet climatic conditions in the dune field (Fig. 18.2), but the dunes (apparently never stabilized) continued to migrate southward during both wet and dry intervals.

In a few other places, the Navajo Sandstone contains thin, isolated limestones that are completely surrounded by sandstone. These were deposited in lakes that formed between the dunes during the wet climatic intervals that lasted thousands of years. Petrified wood and stromatolites are recorded and sometimes abundant at some of these sites, and dinosaur tracks are also found around these ancient oases (Eisenberg, 2003; Parrish and Falcon-Lang, 2007).

Among the abundant tracks and trackways in the Navajo Sandstone are rare examples of trackways that have preserved evidence of individual behavior of the trackmakers. At the Coyotes Buttes locality, one trackway has preserved tracks of a small theropod, walking directly up a sloping dune front; crouching down; making full impressions of the metatarsi, the belly, and both hands; and then continuing straight up the dune front (Milàn, Loope, and Bromley, 2008) (Fig. 18.1C). One sauropodomorph, trackway, Otozoum, shows normal bipedal progression (Fig. 18.1D), whereas another sauropodomorph trackway, Navahopus, shows a sauropodomorph in quadrupedal stance walking up the sloping dune front. The first part of the trackway shows the animal walking at an angle upward, all the time keeping the axis of the body directed upward, before changing its mode of progression to directly up the slope (Fig. 18.1E). Trackways showing a similar mode of progression are known from Pleistocene coastal eolianites from the Mediterranean island Mallorca, where Pleistocene goats adopted a similar sideways gait when they progressed up the steep dune faces (Fornos et al., 2002), and reptile trackways in the Permian eolian Coconino Sandstone of Grand Canyon also show a similar sideways mode of progression (Brand and Tang, 1991; Loope, 1992).

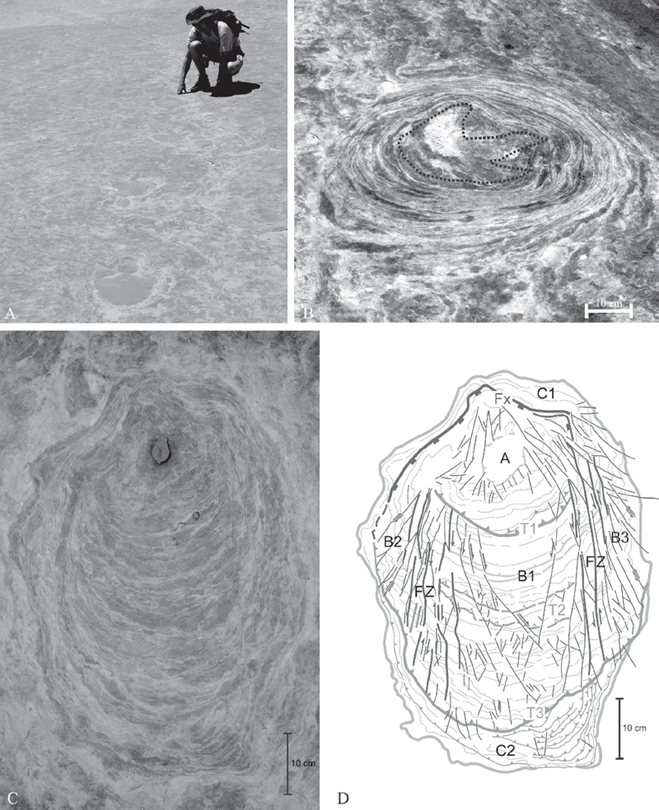

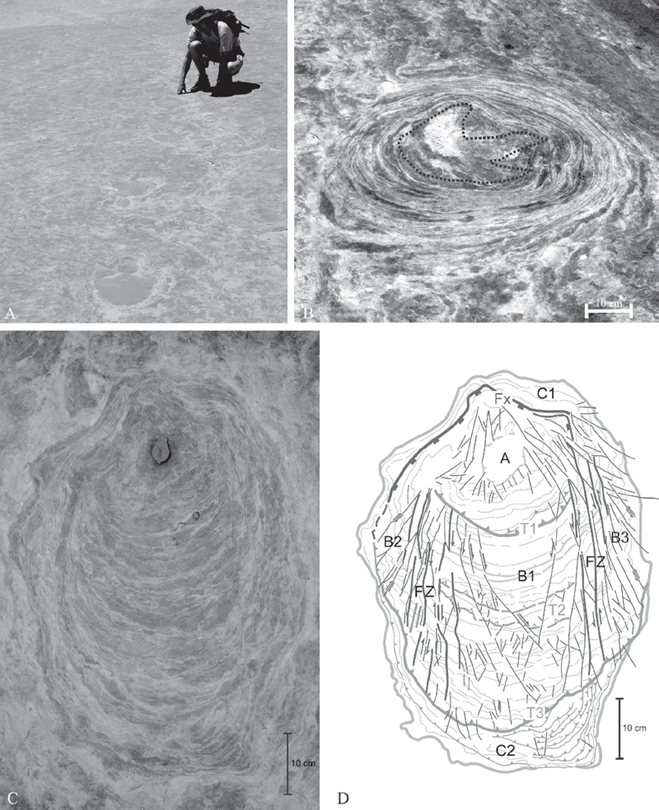

18.3. Tracks in the Entrada Sandstone at Twentymile Wash, Utah. (A) Trackway of large theropod preserved on a laminated interdune surface. (B) Close-up of single track with an extensive zone of disturbed sediment around it. The estimated extent of the original footprint is indicated by broken line. (C) Track where the dynamic contact between the trackmaker’s foot and the substrate has caused an extensive set of faulting and rotated discs. (D) Interpretation of C (from Gravesen, Milàn, and Loope, 2007).

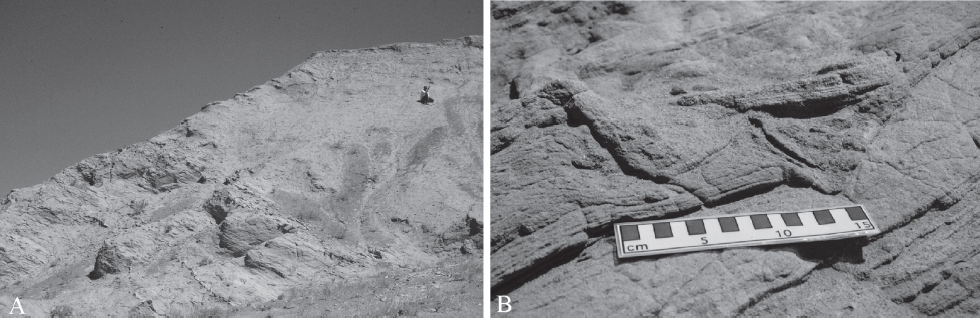

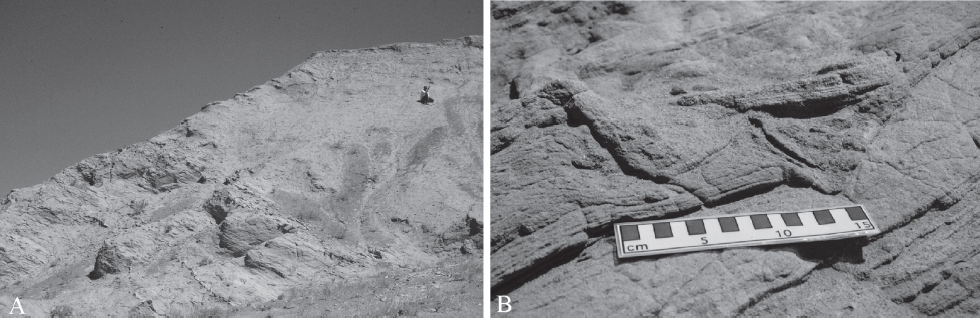

18.4. Cretaceous dune deposits from southern Mongolia. (A) Cross-bedded sandstone on the left contains well-preserved tracks; deposits on the right are bioturbated and have abundant dinosaur bones (man sits at bone site). (B) Cross-section of a typical dinosaur track from one of the cross-bedded parts of the formation.

DINOSAUR TRACKS IN INTERDUNE DEPOSITS, MIDDLE JURASSIC ENTRADA SANDSTONE, UTAH, UNITED STATES

Although small theropod tracks are found in cross-bedded dune facies within the Entrada Sandstone (Lockley, Mitchell, and Odier, 2007), tracks are also found preserved in flat-bedded eolian sandstones. In many dune fields, the areas between migrating dunes are covered with wind-ripples. When wind-ripples migrate, they commonly climb over one another, producing firm, flat deposits of thin-bedded sand. Animals do not sink deeply into these deposits, so tracks are shallow (Fig. 18.1D). In some interdune areas, the water table is near the surface, and the sand can get cemented by salts when moisture evaporates. In the wind-deposited, Middle Jurassic Entrada Sandstone of south-central Utah, hundreds of large dinosaur tracks are arranged in long, horizontal trackways (Milàn and Loope, 2007) (Fig. 18.3A). The animals walked over a flat desert surface that was mantled by small dunes. Salts lightly cemented the sandy surface, so the weight of the large theropods not only depressed the material directly under their feet (the “true track”), but it also disturbed a large area around each track (Foster, Hamblin, and Lockley, 2000; Breithaupt, Matthews, and Noble, 2004; Milàn and Loope, 2007) (Fig. 18.3B). As animals walk, they first compress the sediment under their feet, then push it backward, and, as they remove the foot, stretch the sediment. The damp, thinly laminated sands of the Entrada Sandstone at the Twentymile Wash locality in Utah has captured this interaction between the trackmaker and the substrate.

Close inspection reveals that the disturbed area around each track contains several types of small faults that make it possible to interpret the walking dynamics of the animal (Gravesen, Milàn, and Loope, 2007; Milàn, Gravesen, and Loope, 2014). The sediment layers under the dinosaurs’ feet were pushed down and then radially outward, moving as sheet-like slabs, not as loose sand grains. During the kickoff phase of the dinosaur’s step, a plate of sand is first rotated below the foot, before being pushed backward, creating a set of parallel faults in the sediment (Fig. 18.3C). The well-preserved evidence of “dinosaur-induced tectonics” has been successfully described using terminology from structural geology, which allowed precise reconstruction of the dinosaurs’ walking dynamics (Gravesen, Milàn, and Loope, 2007) (Fig. 18.3D).

SCATTERED TRACKS IN CRETACEOUS DUNES, SOUTHERN MONGOLIA

In the dune deposits of the Cretaceous Djadochta Formation of the Gobi Desert, scattered tracks are visible in cross-sections of sloping dune deposits (Loope et al., 1998) (Fig. 18.4B). Ukhaa Tolgod, a site recently discovered by paleontologists from the Mongolian Academy of Sciences and the American Museum of Natural History, is famous for its dinosaur bones. The bones, however, are never found in the cross-beds with the tracks. The bones are in crudely bedded or unbedded sandstone in between the cross-bedded deposits (Fig. 18.4A). The unbedded sediment was bioturbated by abundant burrowing insects (?) and plant roots that are now replaced by calcite (rhizoliths).

The distribution of the fossils and the tracks suggests that the animals whose bones were fossilized lived in a dune field that was stabilized by plants and had abundant life (somewhat similar to the modern Nebraska Sand Hills, a grass-stabilized dune field on the North American Great Plains). When the Cretaceous dunes were active (desert conditions) only a few animals walked across the actively migrating dunes, so only a few tracks and no bones are preserved during those time intervals.

EOLIAN ICHNOFACIES

Based on characteristic assemblages of vertebrate tracks occurring together in eolian deposits, multiple eolian vertebrate ichnofacies have been erected (Lockley, Hunt, and Meyer, 1994). The term “ichnofacies” was introduced by Seilacher (1964, 1967) to cover recurring associations of trace fossils related to sedimentary facies and depositional environments. The term has later been used in many different scales from global associations to individual rock units (Bromley, 1996). Dealing with vertebrate trace fossils, Lockley, Hunt, and Meyer (1994:242) suggest defining vertebrate ichnofacies as “multiple ichnocoenosis that are similar in ichnotaxonomic composition and show recurrent association in particular definite environments.”

So far, two distinct eolian vertebrate ichnofacies have been recognized. The Paleozoic Laoporus ichnofacies is a recurrent association of vertebrate tracks from the Permian Coconino Sandstone of Arizona and contemporary Lyons Sandstone of Colorado. The ichnofacies comprise the synapsid trackways Laoporus, the lizard-like ichnogenus Dolichopodus together with abundant invertebrate traces including Octopodichnus and Paleohelcura (Lockley, Hunt, and Meyer, 1994). As Laoporus is a junior synonym of Chelichnus, the Laoporus ichnofacies is now referred to as the Chelichnus ichnofacies (Hunt and Lucas, 2007; Lockley, 2007).

The Mesozoic Brasilichnium ichnofacies are confined to erg settings and found in the Lower Jurassic Navajo and Nugget sandstones of the Colorado Plateau region, the equivalent Aztec Sandstone of California, and the Botucatu Formation of South America. The trackmaker for Brasilichnium is considered a synapsid with mammal-like reptilian affinities (Lockley, 2011a). Apart from abundant Brasilichnium tracks, also the invertebrate tracks Octopodichnus and Paleohelcura are abundant, as well as theropod, prosauropod, and small mammal tracks (e.g., Lockley, Hunt, and Meyer, 1994; Rain-forth and Lockley, 1996a, 1996b; Milàn, Loope, and Bromley, 2008; Lockley, 2011a, 2011b; Lockley et al., 2011). Because of the morphological similarities between Jurassic and Late Paleozoic Octopodichnus, Paleohelcura and mammaloid tracks (Chelichnus in the Permian and Brasilichnium in the Jurassic) the dune ichnofacies from eolian deposits spanning this long time interval are almost indistinguishable.

CONCLUSIONS

Recent research into tracks registered and preserved in eolian strata and the usage of the concept of eolian vertebrate ichnofacies has provided important information about animal behavior and ancient environments. Because skeletal remains are uncommon in eolian strata, tracks provide additional, and often the only, information about the fauna that inhabited the area. Tracks are easily recognized in vertical cross-sections as disturbances of the uniformly bedded eolian strata. Close examination of dinosaur tracks in finely laminated interdune strata, provides insight into the second for second interaction between an extinct animal and the sediment it walked on, allowing a very detailed reconstruction of the walking kinetics of the trackmaker.

REFERENCES

Brand, L. R., and T. Tang. 1991. Fossil vertebrate footprints in the Coconino sandstone (Permian) of northern Arizona: evidence for underwater origin. Geology 19: 1201–1204.

Breithaupt, B. H., N. A. Matthews, and T. A. Noble. 2004. An integrated approach to three-dimensional data collection at dinosaur tracksites in the Rocky Mountain west. Ichnos 11: 11–26.

Bromley, R. G. 1996. Trace Fossils: Biology, Taphonomy and Applications. 2nd edition. Chapman and Hall, London, U.K., 384 pp.

Eisenberg, L., 2003. Giant stromatolites and a supersurface in the Navajo sandstone, Capitol Reef National Park, Utah. Geology 31: 111–114.

Fornos, J. J., R. G. Bromley, L. B. Clemmensen, and A. Rodriguez-Perea. 2002. Tracks and trackways of Myotragus balearicus Bate (Artiodactyla, Caprinae) in Pleistocene aeolianites from Mallorca (Balearic Islands, western Mediterranean). Palaeogeography Palaeoclimatology Palaeoecology 180(4): 277–313.

Foster, J. R., A. H. Hamblin, and M. G. Lockley. 2000. The oldest evidence of a sauropod dinosaur in the western United States and other important vertebrate trackways from Grand Staircase-Escalante National Monument, Utah. Ichnos 7: 169–181.

Gravesen, O., J. Milàn, D. B. Loope. 2007. Dinosaur tectonics: a structural analysis of theropod undertracks with a reconstruction of theropod walking dynamics. Journal of Geology 115: 375–386.

Hunt, A. P., and S. G. Lucas. 2007 Tetrapod ichnofacies: a new paradigm. Ichnos 14: 59–68.

Irmis, R. B. 2005. A review of the vertebrate fauna of the Lower Jurassic Navajo sandstone in Arizona. Mesa Southwest Museum Bulletin 11: 55–71.

Lockley, M. G. 2007. A tale of two ichnologies: the different goals and missions of vertebrate and invertebrate ichnology and how they relate in ichnofacies analysis. Ichnos 14: 39–57.

Lockley, M. G. 2011a. The ichnotaxonomix status of Brasilichnium with special reference to occurrences in the Navajo sandstone (Lower Jurassic) in the western USA. New Mexico Museum of Natural History and Science Bulletin 53: 306–315.

Lockley, M. G. 2011b. Theropod- and prosauropod dominated ichnofaunas from the Navajo-Nugget sandstone (Lower Jurassic) at Dinosaur National Monument: implications for prosauropod behavior and ecology. New Mexico Museum of Natural History and Science Bulletin 53: 316–320.

Lockley, M. G., A. P. Hunt, C. A. Meyer. 1994. Vertebrate tracks and the ichnofacies concept; pp. 241–268 in S. K. Donovan (ed.), The Palaeobiology of Trace Fossils. Wiley, New York, New York.

Lockley, M. G., L. Mitchell, and G. Odier. 2007. Small theropod track assemblages from Middle Jurassic eolianites of eastern Utah: paleoecological insights from dune facies in a transgressive sequence. Ichnos 14: 132–143.

Lockley, M. G., A. R. Tedrow, K. C. Chamberlain, N. J. Minter, and J.-D. Lim. 2011. Footprints and invertebrate traces from a new site in the Nugget sandstone (Lower Jurassic) of Idaho: implications for life in the northwestern reaches of the great Navajo-Nugget erg system in the western USA. New Mexico Museum of Natural History and Science Bulletin 53: 344–356.

Loope, D. B. 1986, Recognizing and utilizing vertebrate tracks in cross section: Cenozoic hoofprints from Nebraska. Palaios 1: 141–151.

Loope, D. B. 1992. Comment on ‘Fossil vertebrate footprints in the Coconino sandstone (Permian) of northern Arizona: evidence for underwater origin.’ Geology 20: 667–668.

Loope, D. B. 2006, Dry-season tracks in dinosaurtriggered grainflows. Palaios 21: 132–142.

Loope, D. B., and C. M. Rowe. 2003. Long-lived pluvial episodes during deposition of the Navajo Sandstone. Journal of Geology 111: 223–232.

Loope, D. B., L. Dingus, C. C. Swisher III, and C. Minjin. 1998. Life and death in a Late Cretaceous dunefield, Nemegt Basin, Mongolia. Geology 26: 27–30.

Milàn, J., O. Gravesen, and D. B. Loope. 2014. Dinosaur tectonics: when biomechanics meet structural geology. Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology, Program and Abstracts 2014: 188.

Milàn, J., and D. B. Loope. 2007 Preservation and erosion of theropod tracks in eolian deposits: examples from the Middle Jurassic Entrada sandstone, Utah, USA. Journal of Geology 115: 375–386.

Milàn, J., D. B. Loope, and R. G. Bromley. 2008. Crouching theropod and Navahopus sauropodomorph tracks from the Early Jurassic Navajo sandstone of USA. Acta Palaeontologia Polonica 53: 197–205.

Parrish, J. T., and H. J. Falcon-Lang. 2007. Coniferous trees associated with interdune deposits in the Jurassic Navajo Sandstone Formation, Utah, USA. Palaeontology 50: 829–843.

Rainforth, E. C., and M. G. Lockley. 1996a. Tracks of diminutive dinosaurs and hopping mammals from the Jurassic of North and South America; pp. 265–269 in M. Morales (ed.), The Continental Jurassic. Bulletin 60. Museum of Northern Arizona, Flagstaff, Arizona.

Rainforth, E. C., and M. G. Lockley. 1996b. Tracking life in a Lower Jurassic desert: vertebrate tracks and other traces from the Navajo sandstone; pp. 285–289 in M. Morales (ed.), The Continental Jurassic. Bulletin 60. Museum of Northern Arizona, Flagstaff, Arizona.

Seilacher, A. 1964. Biogenic sedimentary structures; pp. 296–316 in J. Imbrie and N. Newell (eds.), Approaches to Palaeoecology. Wiley, New York, New York.

Seilacher, A. 1967. Bathymetry of trace fossils. Marine Geology 5: 413–428.