Chapter 18

Tempe and me is all the time talking about running. The bigger her belly gets, the more we talk about it. Neither one of us wants you to be no slave. Your pa don’t neither, but he’s scared. Every plan we come up with he ends with, “Wait until after the baby.” His eye gets to twitching every time we mention it. Pretty soon his wait turns into no: What if we? No. What about? No. How about? No. Nothing is careful enough. Gets to the point Tempe and me wait on him to slip away for the night to talk about leaving. The longer the war lasts, the harder it is for Edward to get back. Days at a time go by before we see him. Any news we get come from Edward.

“How you gonna get Edward to come along?”

“With this baby,” Tempe says.

We’re lying out in the wet grass watching the clouds pass across the moon. The air is crisp. It’s been months since we heard any but we listen for the familiar rumbling of faraway gunshots. I imagine thunder is the roar of a cannon. If I close my eyes tight and put my ear to the earth, I swear I can hear screams. Hoots, squeals, chirps, the night is noisy. All around the cabin, the garden, the wood, is thick with animals hunting, being hunted. The silence creeps up on us like a ghost. A loud, twig-breaking ghost. Tempe tenses beside me. A bird screeches. I want to jump but Tempe’s nails digging into my arm pin me down.

“I said,” a boy says, “is it safe to come out?” He repeats the screech. “It’s a call, don’t y’all got one?” He steps out from behind a row of trees.

Me and Tempe sit up. I reach around for a branch or rock or something, in case I need it.

“I didn’t expect to run into nobody,” the boy says. “What y’all doing here?”

“Living,” Tempe says.

“Slaving’s over,” the boy says.

“What you talking about?” I ask. Poor thing. He can’t be more than ten years old. Running around thinking he’s free.

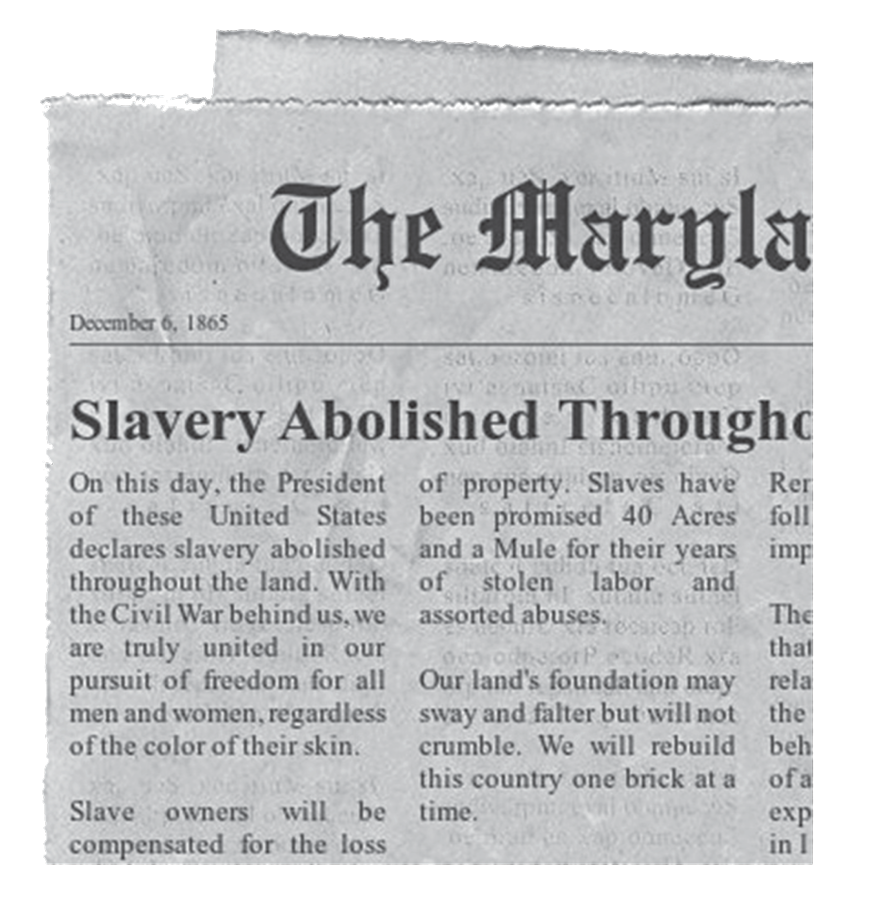

“Gal, y’all must be the last two slaves in the whole wide world. Maryland been free since last year and slaves all over been free for weeks.”

“Then what you running around slipping through the woods for?” Tempe asks.

“Roads ain’t safe,” he says, “patrollers on the roads rounding people up.”

“Didn’t you just not one minute ago say slaving is over, we free?”

“They catching people up here, sending them to work houses, planting them on farms, selling them to folks. Y’all coming?”

Free? No running away, buying ourselves, just free. Mama will be home any day now.

“We waiting on our mama to get back,” I say. “Soon’s she get back, we’ll be on our way.”

“I got to get moving. My mama out there somewhere looking for me. I’m gonna find her.”

“How you know where to look?”

The boy presses a splayed hand over his heart. “This right here.”

“You ain’t got no map? You end up dead just following that.”

“I end up dead staying here too,” he says. “Don’t see the point of just waiting on being found. What if she hurt up? Some mean somebody might be keeping her and she can’t get back to me. No, I ain’t gonna wait here one more night. How long you gonna wait?”

I don’t know. My whole body is shaking. Free? What if he’s right? Should we just go and ask Walker? Wait on your pa? If this boy’s running to find his mama, Watson could be making his way back to me.

“Whatchu gonna do if you don’t find your mama?” Tempe asks.

“I’m gonna find her,” he says.

“Your master just let you go?”

“I left. Soon as word came that we was free, we left. The master tried to convince us to stay. Said we was family and family don’t just walk away. When that didn’t work he said he’d pay us. I don’t have no need for nothing. I have to get to my mama. Wasn’t no price he could afford that could make me wait longer than I had to. I wasn’t the only one felt like that. Some stayed. The rest of us packed up what we could but we didn’t get to keep it. When he found out we were leaving, the crazy goat came chasing after us with shotguns. He was carrying on about us owing him and him collecting in blood. Good thing he can’t see straight. I would be dead right now if someone hadn’t already run off with his ammunition.” We laugh along with him. I want to ask what it’s like, freedom, if the stars don’t look brighter, the water taste cooler, the berries sweeter, but I don’t have time. He’s caught his wind and is already edging back to the woods. “Y’all sure you ain’t coming?” he asks.

I’m halfway up.

“We sure,” Tempe says for the both of us.

He’s already gone. The night settles as if he was never there.

Tempe lies back down. “We ain’t free until Walker says we free,” she says. Before long she’s snoring.

I lay back down too but I don’t sleep.

By morning we decide to wait for your pa to come back. Tempe don’t want to leave without him. Between planning how to get Walker to tell us where Mama is, where she want to move, how she want the house to look and how she gonna act when she meets Edward’s mama, Tempe don’t hardly have time for me to talk about trying to find Watson. Soon as I bring him up, Tempe brings him down: need to find yourself a born-free man, she says. Like she done forgot your pa was born a slave just like we was. I don’t argue with her. Soon as we get settled somewhere new, I’m gonna find Watson. I spend most of the days rolling last names around my mouth. Spring Kirk. What if Watson changed his name? I wouldn’t blame him if he did. Who will I be then? Mrs. Watson. I can’t get farther than that. River, Sanctuary, Grass. I think of all the places we shared. Would he choose one of those as a name? I just hope I like our new name. It would be awful to get saddled with a name that don’t sound right but I won’t complain, won’t make a face or nothing. I won’t let on that I don’t like it, seeing as he worked hard to get us a name. At night I plan the wedding and the house we’ll build between Tempe and Edward’s and Mama’s. I’ll have to tell Watson there won’t be no babies. But we’ll have you. Won’t need no babies of our own. I don’t tell Tempe nothing. During the day I work harder than I ever done. Weeks pass.

“Ain’t nothing wrong with your hands,” I say. I spit.

Sweat and dirt are in my mouth. I been digging up all our treasures. Don’t leave nothing behind, Tempe said, instead of helping. When I finish digging, Tempe gets to telling me what to put where and how to tie this bundle and that one. She got one more time to call me dim-witted. Before I can tell her, your pa come running through the woods. He quiets Tempe’s fussing with kisses and hugs.

“Where you been?” I ask. “We been waiting on you.”

Tempe gives me a look that could freeze the damned.

“I wasn’t sure I’d find y’all here,” he says. “I been worried something fierce bout where you two would be.”

I can’t help myself, I smile.

“Don’t know what I would do if something happened to you and my baby,” Edward continues. “Soon as I heard y’all was free, I go see Walker. I says, I’m here to take my family home. He says, ‘You ain’t taking nothing of mine nowhere.’ I says, slavery done ended, Master Walker. He says, ‘Not here.’ I tell him, yes, sir, right here and all over Maryland. And he says, ‘Then we moving down south, me, Tempe, Spring, and the baby.’ I says, no, sir, no you ain’t, slavery is dead all over. He says, ‘You right, I be right back.’ By the time he comes back to the porch waving that rifle, I’m already halfway across the field. Ain’t stop him from shooting at me. I ran. I couldn’t stay away no longer. I was worried he’d move you away before I could get back. I was praying you’d still be here. We gonna have to leave tonight. I got a friend who can get us on a train north. Done arranged everything. Further north we get, less chance of Walker following. Woods is getting as dangerous as the roads but I don’t see no way around it.”

“We’ll leave first thing in the morning,” Tempe says.

“We ain’t got till morning,” Edward says. “Got to be right now. I got us passage.”

Tempe and Edward might have forgotten about Mama but not me. I’m not leaving without her.

“It’s too dark, Edward, what about the baby?” Your ma pats her belly.

It’s settled. No matter how well Edward knows his way, it’s safer to leave in the morning. It’s the tears that convince him. Least if we wait till morning, we can stop for help if we need it. I can see your pa don’t want to but he agrees to see if he can’t switch times with another family. He’ll be back by sunrise. Soon as he leaves we get planning.

“We gonna have to get Walker to tell us where Mama is,” Tempe says.

“How we know he even knows where she at?”

“Of course he knows. If he don’t who do?”

“Alright, I’m gonna ask him.”

“Why would he tell you anything?” Tempe asks. It’s dark. No moon to speak of, but I know she’s standing there with her hands on her hips.

“Cuz I’m a miracle.”

“No you ain’t. I am.”

“And if he don’t tell you?”

“He dies knowing something we don’t.”

Kill him. The more we talk on it, the easier it seems. Before long, don’t seem to be no other way. We gonna wait till morning and give him a chance to save his life. It’s only Christian. We’ll ask him where Mama is. Least he can do for Tempe lifting the curse is tell us. If we right, we leave and go find her. If we wrong, he dies. He ain’t gonna sell neither one of us. We too excited to sleep. We spend hours thinking how to do it. We’ll go right up the front steps, up to the door, knock. He’ll probably be expecting us to scrub the floors or get ironing or cooking. With nobody but him there, the place is bound to be knee-deep in dust. He’ll let us in. We’ll ask him then. We talk through turn after turn. Laughter, anger, begging; we got all his responses covered. If it comes to it, we got ours too.

Tempe’s set on poison. If we’re going to do it, I want something quick, painless. Shooting him seems easiest. Between cleaning them and using them to guard the Missus’ garden from critters, Tempe and me been handling shotguns for years. Know just where to find them, too.

“What about the law?” Tempe asks. “If the Missus ever do come back, the first thing she’ll see is Walker lying round with a big ol’ hole in his head. The second thing is you and me gone. It won’t be long before somebody’s looking for us.” If we drag him out the back door, through the fields and such, we can drop him in the ditch. But Tempe drags her foot along the dirt. I follow the trail she makes. Fire. If Walker won’t tell us where Mama is, we’ll send him straight to hell. Won’t even kill him first. Tempe will ask about Mama while I say it’s chilly and get a fire going. The curtains will be first. I always hated washing and rewashing that brocade cloth. It made my fingers stiff. After the curtains, the rugs, the settee, Walker. Tempe’s set on it if he don’t tell. I try to picture Walker telling us where to find Mama and me and Tempe walking out the front door and down the path free.

I can’t see it.

We’re too excited to wait until morning. We set off for the house. Tempe lumbers behind me. I carry both of our bundles. She stops every few steps. We’d be there by now if she would just keep walking. She’s breathing heavy. Just before we reach the river, her heavy breathing turns to moaning. A few more steps and she falls to her knees.

“The baby?” I don’t need to ask. We waited too long. “Help me up.”

The more I pull, the more her body seems to root to the spot. I heave her to her feet.

“Wanna go back?”

She don’t bother to answer. We time our pace with her pains. Sweat drenches her body, making it hard to even hold on to her hand. She bites down on snapped-off pieces of bark to keep from screaming. She needs to rest. We sitting there swinging our feet at the edge of the river when Tempe’s water come down. You won’t be far behind it. Owls screech. Crickets chirp. Nightbirds call. Everything’s waiting. The bark doesn’t work, Tempe screams. To quiet her, I give her a twig to chew down on. It cracks between her teeth. She howls and I’m worried hounds will join in. I try to shush her but the look she gives me sends me scurrying to find her a clump of sweetgrass to grind. The words that come out of her mouth. When she opens her mouth to scream again, I shove a clump of grass, dirt and all, inside. I imagine her biting the heads off of fat worms. Sick moves up my throat. But you coming and I swallow it. I rub my hands over her belly making rhythmic circles on her skin. You squirm beneath my fingertips. You arch and stretch, Tempe screams. A few seconds later, you do too. Your cry is an angry wail. I take some scraps from my bundle, soak them. Tempe washes your little wrinkled body. It’s the happiest I ever seen her. We slice the cord with a hunting knife. I bury the cord nearby.

She’s rocking back and forth, singing to you while you nurse.

“What’s his name?”

“Edward Jonah Freeman.”

She’s holding you so tight I’m worried you can’t breathe. “Want me to hold him?”

“He don’t deserve to be no slave,” Tempe says.

“He ain’t one. You heard that boy. Edward’s born free.”

“What if he’s wrong? What if that boy was sent by Walker to poke fun, to get us riled up, just to see what we’d do?”

“Walker wouldn’t do that. He would have just come down and said it himself. The boy was telling the truth. We free. The baby too.”

“Free. And then what? Same people that slaved us still running around.”

“Them running around don’t stop us from moving none.”

“Walker’s free. Sheriff gonna haul him off for keeping us? For selling Mama?”

“We don’t know if he sold Mama or not.”

“These people decided we was gonna be slaves. You and me, Mama, her mama, her mama’s mama. I don’t want my baby growing up with their words in his mouth.”

“Who gonna tell him? I ain’t. Nobody’s gonna call this baby a slave. Not you, not me.”

“It ain’t us I’m worried about.”

Tempe has her mouth over yours. It ain’t no kiss. It’s like she’s sucking the life from your body. You wiggle.

“Don’t do it, Tempe,” I say. My hand is on her shoulder. My breath’s in her ear. “We’ll keep him safe. You and me.”

“We’ll see,” she says. She kisses your forehead. Squeezes my hand. She’s bundling you up and already walking toward the house. I gather our belongings and hurry to catch up thinking, We can’t do this, we can’t do this. I don’t say a word.

8:15 p.m.

We kept him safe, alright, Tempe says. Blaming me for his life, blaming me for his death, for the first time in a long while, I ignore her.

Walker’s sitting on the porch rocking in that chair like he been up all night just waiting. “You put her up to this,” he says, pointing at me. “You more like your mama than I thought. Ain’t I done everything for you? I gave you a mama when your own up and killed herself.”

James was right. I can’t catch my breath. Don’t seem like my body is working at all. My heart ain’t beating. I can’t swallow. Can’t blink. All I can do is hear.

“Should have known you’d have had some of that devil in you,” he says. “Nothing but the devil. First chance you get you run off and drag your sister and that baby through the woods. And why? Cuz somebody done told you you suppose to be free?” He spits a dark clump of tobacco that near hits me. I don’t move. “Well, they done lied to y’all. The war done ended and they ain’t set you free, did they? Ain’t nobody come knocking on your door, door I provided, to give you no papers or nothing. I coulda told you wouldn’t nothing change but you wouldn’t have believed it, would you? How could you? Too full of your mama and her evil ways to know when somebody doing you right. It ain’t your fault.” He pauses, leans forward so far I think he’ll fall clear out his chair. “Ain’t Tempe’s either. It’s mine. I got my own self to blame. Treating you like family, like equals. I was going to let you all go right on working and I was going to go right on taking care of you all. No bad blood or nothing. But I see we can’t do that. Can’t be civil with animals. You want to be free. You free. There’s your papers right there.” He balls up a sheet of paper and tosses it by my feet. “Go on.”

“What about Mama?” Tempe asks.

Walker gets to grinning. “That’s what you come for? Agnes?” He laughs. “Why all you had to do was ask! I got the papers right there in the house. Come on in and help me get them,” he says.

I step up on the porch and press my palm against the wood door. The smell of dust and mold hits me soon as I open the door. I hold my breath; don’t get one foot across the threshold.

“Not you,” Walker says, “you.” He points to Tempe.

Your mama kisses you on the top of your head, squeezes you tight, and puts you in my arms.

“Just for safekeeping,” she says.

She takes my place at the door. Walker closes it behind them. I’m out there rocking you when your pa comes. I put you in his arms. He’s holding and kissing and loving on you. He’s still holding you when we hear your mama screaming. Smoke’s streaming from the roof. Windows get to popping. The house is on fire. A shot. More screaming. I run to the door to save Tempe. The door’s already gone. Inside, the front room, parlor, sitting room is fire. What used to be furniture are melting balls of flames, the walls and floor are nearly gone. I’m calling, Tempe! Tempe! But there’s no answer. She’s the only thing on my mind. I can’t live without her. She’s all I have.

Your pa pulls me back, drops you in my arms.

“Run! Keep my boy safe!” he says.

The house is splintering, cracking in two. It’s being eaten alive and taking Tempe with it. Your pa shoves me down what’s left of the steps. Without looking back or knowing your name, he jumps into the flames. Two more shots, one more scream. I run.

You hungry, soiled, and angry. I don’t know where we heading but I plan to stay in the woods most of the day. I ain’t the only one. Freedom come alright. For most of us, it hasn’t come on horses or with golden trumpets. Wasn’t no angel going around saving all the slaves. Some owners turn people loose. Some slaves walk off. Far as I know, wasn’t nobody going round checking if people had set slaves free. And don’t seem like nobody’s making sure we stay free either.

The woods overflow with people. They spill over paths forging ways where there were none. Even in sleep they seem to be moving. Some further south, others up north. A few of them wander, stumbling over rocks and people, silently staring straight ahead. Most people talking, singing, mumbling, laughing, moaning, crying, some of them all at the same time. Everybody’s carrying some bit of news or looking for some. I can’t rest at a log or sip along the river without somebody slipping behind me asking if I know their brother, sister, mother, father. If I can help them find their daughter, cousin, grandmama. Their stories keep me up. For that, I’m thankful. I can’t close my eyes without seeing Tempe.

She’s in Walker’s parlor and I’m there with her. They don’t see me. Walker’s pointing a shotgun at Tempe’s chest. Tempe’s holding a hot poker above her head. He’s about to pull the trigger. She’s about to strike. I open my eyes.

I’m back in the woods. I can’t catch my breath.

Keep moving. It’s a whisper just above my ear.

I turn around but ain’t nobody there.

Hurry up. The whisper surrounds me, blowing in both my ears at once.

“Tempe?” I whisper back. I know it ain’t her but it’s her voice. It feels like Tempe. I’m in the middle of the woods talking to myself. People walk right around me not paying me any mind.

You’ll miss her.

“I don’t have time for this foolishness,” I say. “I ain’t taking no parts in this.”

Somebody’s playing tricks on me. I’ll stand right there until the rascal comes out. Ought to be ashamed. I’m tapping my foot, waiting. A hot breeze pushes against my back. The longer I stand, the hotter it blows. I’ll just keep walking, I decide. “I ain’t leaving on account of you,” I say.

I’m not sure but I think I hear laughter.

I’m carrying you tight to my breasts. You mad about it and let me know it. I emptied one of them bundles and wrapped you up inside it. Left them shells, rocks, molded food behind. Memories scattered all over Maryland. From your smell won’t be too long before I have to empty the other one. All I have left is this book, a few skins, a little bit of food, and you. Between screaming, you rooting around and biting on me. More than once I wonder if babies can drink blood cuz you sure seem fit to draw it.

“He’s hungry,” a woman says, like I don’t know it. She slips up beside me. I been trying to mash anything I could find to settle you. “You ain’t got no milk?” She puts out her arms. I undo the bundle. Hand you to her. She’s shaking her head and clucking about how small you is and how lucky you is to be free. She nurses you till you fall asleep. “You ain’t gonna get far with this baby and no milk.”

I don’t ask her why she got milk and no babies. She looks like she been running day and night since the war began. She fidgets when she sits, while she talks. She’s itching to get on her way.

“Now we gonna have to watch out,” she says. “Everybody ain’t ready to stop slaving. They done set up so many rules and laws, the woods is the safest place to be right now. But won’t be for long. So many soldiers marching, slipping, and running through the woods on the way to or from some battle, pretty soon we’ll have to take the main road. The baby’s likely to slow us down. Don’t make no never mind, we’ll head north at nightfall.”

We? I don’t even know this gal’s name and she’s already tied herself to us. You fall asleep in her arms. She ain’t far behind you. Both of you snuggled up against a tree trunk, snoring. Soon as she wakes up I’ll tell her we ain’t going. What do I know about up north? How can I leave Tempe behind?

I can’t sleep with the woods and my head filled with moaning, crying, and footsteps. I close my eyes and see your mama standing in the doorway burning. Each time I blink, my heart jumps. I hear crackling, popping, screaming. Before long it’s like I’m in the house watching Tempe ask Walker about Mama. I can hear him laughing. Pushing up against her, whispering in her ear how he done sold Mama Lord knows where to God knows who. He grabs for her. She snatches up a poker. He reaches for it. She swings. The curtains catch afire, then the settee, then Walker. But he’s got a shotgun. Shots splintering the sky like lighting splitting wood. Sometimes it’s a shotgun in Walker’s hand. Sometimes it’s in Tempe’s. It’s always me pulling the trigger.

Get up.

I don’t need no ad in the paper, no crow flying over my shadow, or no cock crowing to tell me Tempe’s dead. I’m lying there holding my breath, one, two, three, thinking about her, Mama, Watson, Edward. Everybody gone. I’m thinking about the times I ain’t never known that Samantha told us about. The things James said. The stories. Back when he was little, Watson, me, and the kids from the other plantations playing out back of the cabin, snatching crumbs of grown-folk talk, thinking we was grown. Mama teaching me to walk, to run, to be Spring and not Sister all the time. Not my mama? They wrong. All of them. The rumbling snores stop. There’s no wind blowing. Nothing. I ain’t breathing, ain’t holding my breath no more and not bursting for air. It’s pitch black. Something’s moving. It’s light-footed, graceful, close. It’s right next to me, warm. It smells like cinnamon. Ain’t no man, no animal either. I know it ain’t nothing else but Tempe.

Seems like soon as I know it, I can see her. The only light comes from her. Her entire body smolders like burning coal. I feel like I should holler out or scream or pray but I don’t do none of those things. I just wait. She kisses you all over. She can’t get enough of you. I can’t move, don’t want to. She sits beside me. She holds my hands in her warm, smooth ones. We stay there, her sitting and rocking and humming and me just lying there not able to smile, to talk, to breathe. I can’t open my lips, can’t make the words come out. Can’t tell her I love her. I feel a stinging sensation of love all around me, through me. She tells me everything she’s seen since she been dead. How she flips through time like pages and sees whole lives. She tells me about Ella and Mama, Papa Jonah and Mama Skins. Remember, she says. She don’t tell me everything but I don’t know it then. She don’t say it, but I know she wouldn’t have done it if it weren’t for me. She wouldn’t have left you if there had been some other way. If I hadn’t put it in her head that she could save us, that Walker would tell her where Mama was, she’d be alive today instead of me. My heart starts beating fast. I take a deep breath and hold it. I know by the time I let it out, she’ll be gone. I hold it for as long as I can. Sooner or later I breathe.

I sleep for an hour, maybe more. It’s still dark. You’re bound to my bosom, full and happy. The girl is jumpy, ready to move. She’s weaved some hides to make something you can hold on to. When we reach the river, she fills one with water, stitches it. We set off following the river. Twice as many folks out at night as during the day. She’s asking folks about her kin: an old woman with eyes that twinkle when she laughs and nails as long and thick as fingers. A baby that ain’t never opened her eyes.

“Ain’t you got nobody to find?” she asks.

“You seen a woman called Agnes?” I ask the next person we see.

The woman stares at me, waits. “Agnes what?” she asks. “Walker, we belonged to Walker.”

She purses her lips. “Who’s your kin?”

“Just Mama and my sister, Tempe.”

“What she look like?”

I get to describing her. Soon’s as I say one thing, I remember another. “She’s about this tall, no, this tall. About this wide, no,” I picture her again, “this wide. She’s got a laugh that could make the birds take notice. Her voice sounds like trickling rain, she moves like the river.”

The woman grabs both of my hands in hers. “If I see her, I’ll tell her you looking for her. God bless,” she says.

“You ain’t never gonna find your mama like that,” my companion says after a few days.

I picture her twinkling-eyed, long-nailed mama. I’m not the only one, I think. We been walking for miles before I find out her name. We stopped a few minutes ago. She’s nursing you for the umpteenth time.

“What’s his name?”

You’re suckling on one teat, already eyeing the other one. “Edward Freeman, just like his pa. What’s yours?”

“Spinner, like my ma. She was the best spinner on the whole plantation. I’m gonna change my name, though. What they call you?”

Flames lick at the bottom of my feet, up my calves and thighs, to my belly, through my chest. They creep up my neck. Not Sister, not anymore. “Spring, my name’s Spring.”