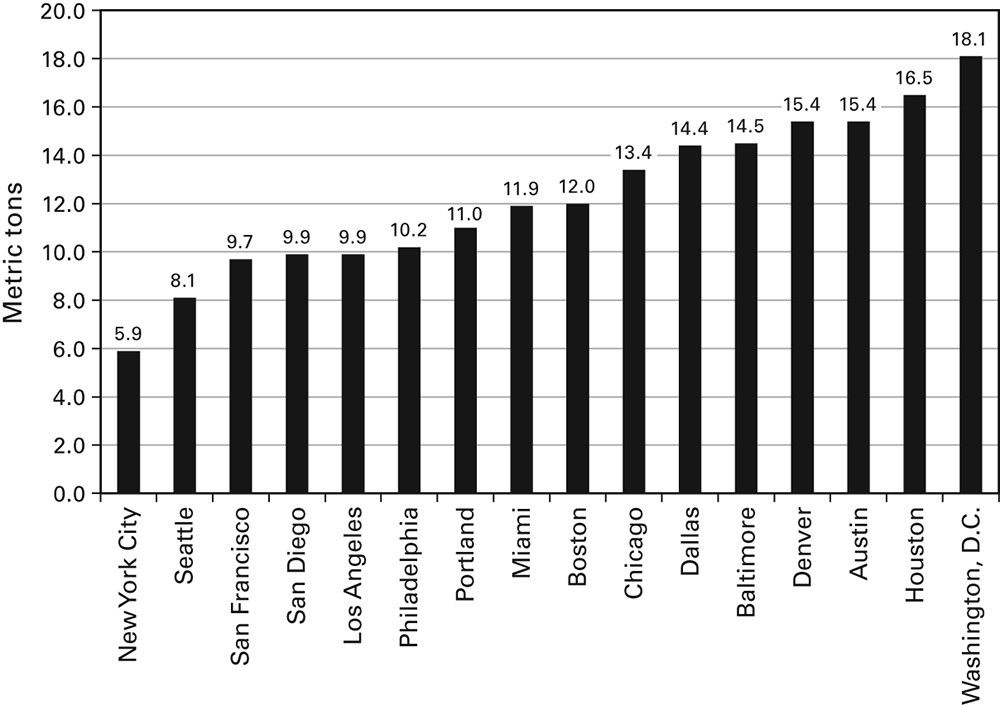

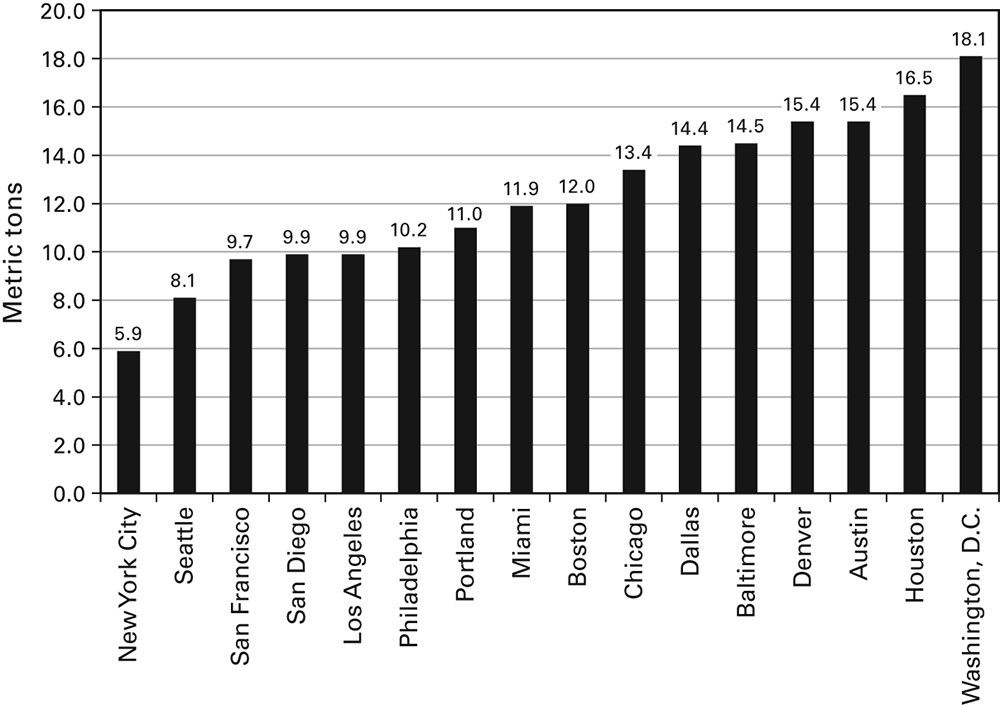

Figure 6.1

Per capita CO2-equivalent emissions in various cities in 2009.

source: New York City 2010: 6

6

The Special Case of Sustainable Cities

Although much of the conceptual literature on sustainability does not directly address many of the ambiguities in concepts of sustainability and sustainable communities, sustainability efforts in smaller geographic areas within countries have begun to provide answers to their underlying questions. This chapter focuses on how the concepts of sustainability have been applied to urban areas, particularly cities.

In the context of the global concern for sustainable development of countries, it may seem somewhat incongruous to think of the geographically narrower idea of sustainable communities or cities. After all, isn’t one of the main reasons for global concern about the environment that small geographic areas are subject to externalities over which they have little or no direct control? Yet even in the international context, attention to sustainable development has included a focus on the local level. When the Brundtland Commission stated that “cities [in industrialized countries] account for a high share of the world’s resource use, energy consumption, and environmental pollution” (WCED 1987: 241), it was arguing that serious attention should be paid to urban sustainability. As part of the UN’s 1992 Agenda 21 resolution, significant attention was paid to the relationship between national policies and the activities of local governments particularly in chapter 28 of the Agenda 21 resolution. In a section titled “Local Authorities’ Initiatives in Support of Agenda 21,” the link is made clearer:

Because so many of the problems and solutions being addressed by Agenda 21 have their roots in local activities, the participation and cooperation of local authorities will be a determining factor in fulfilling its objectives. Local authorities construct, operate and maintain economic, social, and environmental infrastructure, oversee planning processes, establish local environmental policies and regulations, and assist in implementing national and subnational environmental policies. As the level of governance closest to the people, they play a vital role in educating, mobilizing, and responding to the public to promote sustainable development. (United Nations Environmental Programme 2000)

Thus, the idea of sustainable cities was born out of an understanding of the importance of individual human behavior, and the local governance context in which that behavior takes place. It was also founded on the idea that cities represent important places of governance where sustainability can be affected. There is no implication that cities, acting alone, could somehow make the world sustainable. The implication is that working toward making cities more sustainable is an important step toward achieving the larger goal, and that the world cannot become more sustainable if cities are not involved in the effort. It is perhaps not a stretch to say that the idea behind sustainability in cities is a specific example of the old environmental adage “Think globally, act locally.”

Although in common parlance “city” often is used to refer to many different types of urban areas, for the most part “city” as used in this chapter and in most scholarly research, focuses on what might be called geographic areas that have formal legal status or incorporation. This seems consistent with Agenda 21’s suggestion that cities represent important places for efforts at trying to become more sustainable largely because of the role ascribed to “local authorities” in adopting and implementing policies and programs.

Of course, cities aren’t all the same. Some have much more legal authority than others, and some are constrained by larger governmental jurisdictions or other entities in which they are situated. For example, in the United States cities are given their authorities and responsibilities by the states in which they are located, and sometimes a state government makes the pursuit of sustainability policies and programs difficult or even impossible. Despite this, numerous cities around the world have embarked on focused public-policy initiatives in their efforts to become more sustainable.

But these initiatives beg the question “What should cities be doing if they want to achieve sustainability?” A long answer to this question would conclude that no one knows how to make cities truly sustainable. The short answer is that, on the basis of the conceptual notions discussed earlier, cities should pursue policies that promote economic growth without damaging or degrading their bio-physical environments. They should strive to improve their environments as a high priority, and they should make concerted efforts to reduce environmental inequity and increase social justice. These goals may get translated into practice in many different ways—for example, efforts to reduce carbon emissions and carbon footprints, to protect environmentally sensitive lands and waterways, to promote particular kinds of economic development in particular areas (including “smart growth policies”), and to reduce streams of solid and hazardous waste. Numerous efforts have been made to evaluate which cities have decided to pursue which policies. Each of these efforts focuses on particular policies and programs assumed to be consistent with the broader concepts of sustainability.

The idea of sustainable cities first took hold in parts of Western Europe as early as the mid 1980s. In 1994, the member states of the European Union gathered in Aalborg, Denmark for a conference at which agreements were made to adopt and implement Agenda 21 at the local level (Aalborg 1994). That agreement resulted in what is called the Aalborg Charter, which gained more than 2,500 signatories who agreed to work to create the public policies necessary to make that happen. Ten years later, and periodically thereafter, officials met again to reaffirm their commitment to local sustainability (Aalborg 2004). Since 1994, the concept of local sustainability has spread around the world. In North America, the Canadian cities of Vancouver and Toronto and the US cities of Seattle, San Francisco, and Portland began their initial forays into trying to become more the by the late 1980s or the early 1990s.

Sustainability Outcomes among Cities of the World

Very few efforts have been made to systematically assess how sustainable the world’s cities are by objective measures. One such effort, conducted between 2009 and 2011 under the auspices of Siemens AG, focused on trying to measure the sustainability of cities by focusing on the quality of the environment with respect to energy and carbon emissions, water, sanitation transportation, land use and buildings, and waste management. These “Green City Indexes” represent an effort to conduct standardized assessments for Europe (Siemens AG 2009), the United States and Canada (Siemens AG 2011b), Latin America (Siemens AG 2010), Asia (Siemens AG 2011a), and Africa (Siemens AG 2012). Of course, these assessments only scratch the surface of what might be considered important measures of sustainability.

The results of the Siemens studies are summarized in table 6.1. The assessments for Europe and North America are represented by Index Scores—summary measures of how each city fares across all measures. (The reports provide added detail showing how each city ranks on each separate measure.) Apparently, data limitations precluded comparable calculations in Asia and Latin America, for which the reports simply categorize cities according to whether they are “well above average,” “above average,” “average,” “below average,” or “well below average” among cities in their respective regions. All of the cities in the region that were categorized as “well above average” or “above average” are listed in table 6.1. All other assessed cities were rated as “average” or worse.

These assessments suggest that European cities have been fairly successful at achieving relatively high levels of sustainability. Three Scandinavian cities—Copenhagen, Stockholm, and Oslo—are at the top of the list. The list of US and Canadian cities shows that San Francisco, Vancouver (BC), New York, and Seattle score very high, comparable to a number of European cities. In Latin America the Brazilian city of Curitiba tops the list, and all of the cities estimated to be “above average” or “well above average” are in Brazil except Bogotá. Among Asian cities, the independent city-state of Singapore is at the top of the list and Chinese and Japanese cities dominate the “above average” rankings. In Africa, none of the fifteen assessed cities ranked “well above average,” and only Accra, Cape Town, Durban, Johannesburg, Casablanca, and Tunis were ranked “above average.”

Sustainable Cities by Design: Experiments in Creating New Cities

The vast majority of efforts to make cities more sustainable involve “retro-fitting”—that is, working incrementally toward changing established policies, programs, and behaviors so that existing cities are more in line with the goals associated with sustainable outcomes. The challenges, difficulties, and limitations associated with this approach have been well documented. But in a number of “experiments” new cities have been built from scratch. In recognition that “retro-fitting” existing cities faces enormous challenges and constraints, these new cities have been designed from the outset with an eye toward applying scientific, engineering, and design knowledge to the goal of creating sustainable places. Most such experiments, such as EcoCity Cleveland, EcoVillage at Ithaca, and Arcosanti (in Arizona), are very small in scale. The purpose of these experimental projects is to provide a real-world basis for studying what works and what doesn’t so that future efforts will have an empirical basis to guide their efforts as they seek to become more sustainable.

Two planned experiments are worth noting primarily because of their scale. One of these, the Tianjin Ecocity in China, was begun in 2007; the other, Masdar City in the United Arab Emirates, was begun in 2008. Other such efforts that have been planned or initiated including the Dongtan Ecocity in Shanghai, the Caofeidian International Ecocity in Tangshan, the Wuxi Low Carbon Ecocity, the Mentougou EcoValley in Beijing, the Tianjin Ecocity, and the PlanIT Valley in Portugal.

The Chinese government has undertaken numerous experimental projects, usually with extensive international cooperation and technical assistance (Baeumler, Ijjasz-Vasquez, and Mehndiratta 2012). In view of how indifferent China’s government seems to be to the extremely high levels of air pollution in major cities, it may be surprising that China has undertaken so many sustainable-cities projects. Yet pollution, along with a rapidly urbanizing population, undoubtedly helps drive the imperative of working toward urban sustainability for the future. The Tianjin Ecocity is one of a number of similar projects proposed by the national government, and the only such project that has come to fruition. Located about 100 kilometers south of Beijing, adjacent to the existing old city of Tianjin, it is expected to house about 350,000 residents. It has been designed and built with extreme energy efficiency and sustainability in mind, so as to minimize water use, pollution, the production of waste, and carbon emissions. Efforts are being made to get people to move there. Presumably the Tianjin Ecocity will become a laboratory for studying how successfully its design and construction have been.

The creation of Masdar City, located near the historic district of Abu Dhabi, got under way in earnest in 2008. The goal is to create the most effective low-carbon city in the world for about 40,000 residents. Located adjacent to the Abu Dhabi International Airport, Masdar City is designed to be at least as self-sufficient as any other city in the world. With substantial technical assistance from the international community, the project is supported by numerous corporations, universities, and national governments. It relies on somewhat futuristic (and, according to many, utopian) architecture and design, including efforts to exclude fossil-fuel-burning motor vehicles and to place roadways for electric vehicles underground. Masdar City “opened” in 2009 when its first occupants took residence. As of late 2013, when about 1,000 people resided in the city, there were no projections or explicit plans or set timetables for expanding the population to 40,000. Currently, the Masdar Institute of Science and Technology is the core of the city, and apparently most of the residents are associated with it.

Sustainability Policies and Programs in US Cities

The Siemens Green City Indexes attempt to quantify how sustainable cities around the world are on objective measures of the environment and related factors. Efforts also have been made to do essentially the same for US cities. The group SustainLane used fifteen arbitrarily weighted measures, including time spent commuting, traffic congestion, affordability of housing, risk of natural disaster, air quality, regional public-transit ridership, quality of tap water, presence of LEED-certified buildings, community gardens and farmers’ markets, open space, a clean-technology economy, use of renewable energy, city sustainability programs, and presence of a city office to manage sustainability efforts (Karlenzig and Marquardt 2007). As can be seen in table 6.2, which compares all the US cities that Siemens analyzed with those that SustainLane analyzed, there is significant agreement between Siemens and SustainLane as to which cities might be said to be more or less sustainable.

Table 6.2

Sustainability ratings of cities in the United States according to three indexes.

| Siemens Green City Index, 2011 | SustainLane Index, 2007 | Taking Sustainable Cities Seriously Policy and Program Index, 2011 | |||

| San Francisco | 83.8 | Portland, Oregon | 85.08 | Portland, Oregon | 35 |

| New York | 79.2 | San Francisco | 81.82 | San Francisco | 35 |

| Seattle | 79.1 | Seattle | 79.64 | Seattle | 35 |

| Denver | 73.5 | Chicago | 70.64 | Denver | 33 |

| Boston | 72.6 | Oakland | 69.18 | Albuquerque | 32 |

| Los Angeles | 72.5 | New York | 68.20 | Charlotte | 32 |

| Washington | 71.4 | Boston | 68.18 | Oakland | 32 |

| Minneapolis | 67.7 | Philadelphia | 67.28 | Chicago | 31 |

| Chicago | 66.9 | Denver | 66.72 | Columbus | 31 |

| Philadelphia | 66.7 | Minneapolis | 66.60 | Minneapolis | 31 |

| Sacramento | 63.7 | Baltimore | 64.78 | Philadelphia | 31 |

| Houston | 62.6 | Washington | 63.14 | Phoenix | 31 |

| Dallas | 62.3 | Sacramento | 62.64 | Sacramento | 31 |

| Orlando | 61.1 | Austin | 62.00 | New York | 30 |

| Charlotte | 59.0 | Honolulu | 61.42 | San Diego | 30 |

| Atlanta | 57.8 | Milwaukee | 60.42 | San Jose | 30 |

| Miami | 57.3 | San Diego | 57.18 | Austin | 29 |

| Pittsburgh | 56.6 | Kansas City | 56.64 | Dallas | 29 |

| Phoenix | 55.4 | Albuquerque | 56.10 | Fort Worth | 29 |

| Cleveland | 39.7 | Tucson | 55.86 | Nashville | 29 |

| St. Louis | 35.1 | San Antonio | 54.60 | Tucson | 29 |

| Detroit | 28.4 | Phoenix | 54.50 | Washington | 29 |

| San Jose | 54.38 | Boston | 28 | ||

| Dallas | 54.35 | Kansas City | 28 | ||

| Los Angeles | 53.28 | Los Angeles | 28 | ||

| Colorado Springs | 51.38 | Indianapolis | 27 | ||

| Las Vegas | 50.24 | Fresno | 26 | ||

| Cleveland | 50.10 | Las Vegas | 26 | ||

| Miami | 50.00 | Louisville | 26 | ||

| Long Beach | 49.46 | Miami | 26 | ||

| El Paso | 49.10 | Raleigh | 26 | ||

| New Orleans | 49.04 | San Antonio | 26 | ||

| Fresno | 48.96 | Baltimore | 25 | ||

| Charlotte | 47.58 | El Paso | 25 | ||

| Louisville | 47.14 | Cleveland | 24 | ||

| Jacksonville | 46.80 | Milwaukee | 24 | ||

| Omaha | 46.56 | Atlanta | 23 | ||

| Atlanta | 45.20 | Jacksonville | 23 | ||

| Houston | 44.68 | Honolulu | 22 | ||

| Tulsa | 43.74 | Houston | 22 | ||

| Arlington, Texas | 41.80 | Long Beach | 22 | ||

| Nashville | 40.70 | Mesa | 22 | ||

| Detroit | 40.30 | Arlington, Texas | 20 | ||

| Memphis | 40.30 | Memphis | 20 | ||

| Indianapolis | 38.40 | Tampa | 20 | ||

| Fort Worth | 37.50 | Tulsa | 20 | ||

| Mesa | 36.70 | Colorado Springs | 19 | ||

| Virginia Beach | 34.00 | Omaha | 19 | ||

| Oklahoma City | 32.92 | St. Louis | 19 | ||

| Columbus | 32.50 | Oklahoma City | 18 | ||

| Detroit | 17 | ||||

| Virginia Beach | 17 | ||||

| Pittsburgh | 16 | ||||

| Santa Ana | 16 | ||||

| Wichita | 7 | ||||

sources: Siemens AG 2011b; Karlenzig and Marquardt 2007; Portney 2013

The assessments of how sustainable cities seem to be in terms of objective measures of environmental quality provide significant information. The challenge is to understand how much of this might be due to concerted policy efforts of those cities. That a city has relatively clean air, for example, does not provide information as to why that might be the case. That a city has relatively polluted air does not tell us why such is the case; it may imply that this city emits significant pollution, or it may mean that the city is highly affected by emissions coming from elsewhere.

In any case, many cities have taken the challenge and have decided to try to become more sustainable as a matter of public policy. Regardless of their respective base lines, it is important to know what cities are doing in their policies and programs as they seek to improve their sustainability outcomes. In the US, by 2014 at least 48 of the largest 55 cities had dedicated sustainability programs. Of course, cities vary considerably in terms of their de facto definitions of sustainability.

Portney (2013) has attempted a systematic assessment of what cities are actually doing in their public-policy efforts for sustainability, focusing on 38 specific types of policies and programs. That effort doesn’t try to measure sustainability outcomes, such as water quality and air quality. Instead, it focuses on the efforts cities have put into policies and programs that, when implemented, promise to help them become more sustainable. These include smart growth policies related to eco-industrial park development, targeted or cluster green economic development, urban infill or transit-oriented housing, brownfield redevelopment, land-use planning related to zoning to protect environmentally sensitive areas, comprehensive land-use planning incorporating environmental impacts, tax or fee incentives for environmentally friendly development; transportation policies supporting operation of city public transit, limits on downtown parking, high-occupancy vehicle lanes on city streets, alternatively fueled city fleet vehicles, bicycle-ridership or bicycle-sharing programs, pollution reduction or remediation efforts on household solid waste recycling, industrial and residential hazardous waste recycling, volatile organic compound and carbon air emissions reduction, city recycled product purchasing, superfund or hazardous waste site remediation, asbestos and lead paint abatement, pesticide reduction, and urban gardens, sustainable food systems, or sustainable agriculture; energy and natural-resource conservation or efficiency through green buildings, affordable green housing, renewable energy use by city government and renewable energy options for residents, energy conservation, water conservation, the existence of a sustainability indicators effort with regular progress reports (including sustainability program performance indicators and action plans), governance that supports sustainability policies with mayoral and city council involvement, a city agency responsible for managing programs, involvement of metropolitan-wide agencies and local businesses, and public participation. Portney’s assessment simply counts how many of the 38 programs each city had adopted and implemented at the time. The results show that Portland, San Francisco, and Seattle each had adopted and implemented 35 of the 38 programs, whereas Wichita had adopted only seven of them. Six cities had scores of 29, and another six had scores of 26, although the specific programs differed. On the basis of this assessment, a cluster of cities stand out as “taking sustainability more seriously” than most of the others. These include the three cities tied at the top of the rankings and Denver (33), Albuquerque (32), and Oakland (32). The statistical correlation between the Siemens Index and the SustainLane Index is 0.79 for the 19 cities on both lists; the statistical correlation between the Siemens Index and the Taking Sustainable Cities Seriously Index is 0.75 for the 21 cities that are on both lists. The statistical correlation between the SustainLane Index and the Taking Sustainable Cities Seriously Index is 0.67 for the 49 cities on both lists. Although each of these measures of how sustainable US cities are or are trying to become has significant limitations, they all suggest that some cities seem to be more sustainable than others. There is a high level of agreement about which cities are more sustainable, and these tend to be the same cities that are trying to do more as a matter of public policy.

The working definitions of sustainability that cities themselves have developed provide hints to what they see as important. In Seattle, sustainability has been defined as “long-term cultural, economic, and environmental health and vitality.” Santa Monica’s sustainable-communities initiative seeks “to create the basis for a more sustainable way of life both locally and globally through the safeguarding and enhancing of our resources and by preventing harm to the natural environment and human health.” In Cambridge, sustainability means the pursuit of “the ability of [the] community to utilize its natural, human, and technological resources to ensure that all members of present and future generations can attain high degrees of health and well-being, economic security, and a say in shaping their future while maintaining the integrity of the ecological systems on which all life and production depends” (Zachary 1995: 8). These working definitions may well provide the foundational frameworks for more elaborate definitions. Indeed, as many cities move through the process of developing sustainability initiatives, they inevitably develop definitions of sustainability that they believe to be appropriate for them.

Numerous studies have tried to assess the extent to which cities seem to have actually begun working toward sustainability. For example, Devashree Saha and Robert Paterson (2008) analyzed results of a survey administered to officials in 261 US cities and found that programs created to deal with environmental problems and issues were much more prevalent than those focusing on sustainable economy or equity, which led them to suggest that if the three elements of sustainability were depicted as overlapping circles then the environment circle would be considerably larger than the other two. In a similar effort to investigate the types of policies and programs cities have adopted, Eric Zeemering (2009) studied what cities in the San Francisco Bay Area were actually doing and found that cities’ policies tended to gravitate toward prescribing aspects of urban design, traditional economic development, and civic engagement. In other words, cities tended to define sustainability in terms of the architecture of buildings and their relation to one another, of using sustainability notions to bolster traditional approaches to attracting new employers and businesses, and of involving residents in planning processes. What was left out, perhaps surprisingly, was concern about environmental protection and preservation, sustainable food systems, and environmental or social equity. Despite the conceptual underpinnings of the idea of sustainability, in practice local policies seemed to resist incorporation of two of the three pillars of sustainability: the environment and equity.

In a broader national study, XiaoHu Wang, Christopher Hawkins, Nick Lebredo, and Evan Berman (2012) asked officials in 264 US cities whether their city had enacted any of dozens of different specific sustainability-related policies and programs. They found that an overall frequency of program adoptions somewhat lower than those found in other studies. They also found that economic sustainability programs were far less common than social or environmental sustainability efforts. All of the studies of city policies and programs seem to agree that no city is doing everything it could to take sustainability seriously.

Policies for Climate Mitigation and Climate Adaptation

Climate-change issues, which constitute a significant aspect of sustainability, also figure prominently in cities’ attempts to achieve sustainability. Indeed, policies and programs designed to reduce carbon footprints often serve as the cornerstones of cities’ sustainability policies. Climate mitigation has, for at least twenty years, been a focus of many cities’ sustainability policies and programs. These programs have sought to foster energy efficiency, to reduce reliance on fossil fuels and increase reliance on renewable energy sources, and to foster an array of “smart growth” policies designed to reduce the need for personal motor vehicles. When cities engage in transit-oriented development, in the creation of eco-villages, in mixed-use development, in improving public and rapid transit, and in the creation of bicycle-ridership and bicycle-sharing programs, they do so largely with an eye toward promoting behaviors and lifestyles that require less energy and ultimately are responsible for lower carbon emissions. Few cities have gone as far as London, which established a system whereby drivers of motor vehicles are charged substantial tolls to drive in certain congested areas. When New York’s city council enacted a similar program, which required approval from the state legislature, the city was denied the authority to implement it. This demonstrates, at least for programs of that kind, that cities may not have the legal authority to enact and implement the policies with which they wish to address sustainability and climate protection.

Clearly, many cities began to address issues of air pollution before others. Although some cities might compartmentalize climate action as a stand-alone program, more and more cities tackle climate issues as part of their larger environmental and sustainability efforts (Wheeler 2008). In a 2007 survey sponsored by the United States Conference of Mayors, 92 percent of the 134 mayors surveyed reported that their climate-protection activities were part of a larger environmental strategy (United States Conference of Mayors 2007). When cities embark on climate-protection programs, they usually adhere to an approach prescribed by one or more national or international organizations. One organization, called ICLEI—Local Governments for Sustainability, is an outgrowth of the UN’s Local Agenda 21 program; it is a membership organization that a city can join for a fee. The United States Conference of Mayors’ Climate Protection Program invites mayors to sign up and pledge to work to reduce carbon emissions. The US Environmental Protection Agency operates a similar climate program. And the Clinton Foundation created a climate-protection program in combination with its C40 cities initiative to work with the world’s forty largest cities and other willing partner cities to help reduce their carbon emissions. Joining ICLEI’s program or that of the United States Conference of Mayors requires pledging that one’s city will engage in specific activities, starting with efforts to measure carbon emissions.

There are various ways of measuring emissions of carbon and other chemicals that have the same effect on climate change, but all require reductions in emissions over time from some designated base-line year. Although different protocols for measuring local carbon emissions have evolved and improved, there are still some that may not accurately capture the full range of emissions that are likely to affect the climate. And in recent years cities’ decisions to join or to renew membership in these organizations have become matters of political controversy, as was discussed in some detail in chapter 2 above.

Largely as a result of the efforts of the United States Conference of Mayors’ Climate Protection Program, the ICLEI’s Climate Program, the US EPA’s climate initiative, and other programs and initiatives (discussed below), cities have become much more rigorous and systematic in addressing air emissions (Betsill and Rabe 2009; Bulkeley and Betsill 2003; Zahran et al. 2008). In short, climate protection is mainly about reducing emissions, especially greenhouse gases. The idea behind the Conference of Mayors, ICLEI, and EPA climate protection initiatives, of course, is to help cities adopt and implement a variety of specific programs that they hope and expect will lead to reductions in the emission of greenhouse gases.

Cities participating in climate-protection programs are essentially required to conduct a comprehensive greenhouse-gas inventory to measure, from some annual base line, the levels of greenhouse gases emitted by different sectors of their economy. Typically the base-line year is 1990, and cities are expected to reach target reductions from that base line (for example, a 7 percent reduction by 2012, a 40 percent reduction by 2030, and an 80 percent reduction by 2050). The reductions are expected to represent total reductions, not per capita reductions. New York City, which set reduction goals of 30 percent from 2005 to 2030 and 30 percent in municipal government emissions from 2006 to 2017, reported in 2010 that it had achieved reductions of nearly 13 percent between 2005 and 2009 (New York City 2010: 22). A climate action plan requires specification of policies and programs expected to reduce carbon emissions, and periodic (usually annual) progress reports to document reduction efforts and actual reductions. Because of cities’ participation in efforts to measure their emissions over time, this is one of the few areas of sustainability in which we have enough information to begin making inferences about whether and how well specific programs seem to work. In a few cities, these measurements have become part of efforts to develop performance management metrics to ensure that city agencies’ activities are oriented toward the goal of reducing carbon emissions.

Implementing climate action plans is challenging on many fronts. Yet cities have made significant strides in measuring their emissions of greenhouse gases, and in prescribing and taking actions to try to meet their targeted reductions and deadlines. From the perspective of trying to compare these efforts across cities, the data are largely inadequate. Many cities have not yet reported the results of their inventories. Even among those that have done so, very few years have been covered, so trends within cities are difficult or impossible to observe. Moreover, cities are a long way away from being able to link their specific programs with measurable reductions in emissions. One comparison, produced by the City of New York as part of its PlaNYC Climate Action program, shows significant variation across cities in terms of per capita emissions of greenhouse gases (carbon dioxide equivalents, in per capita metric tons) (New York City 2010: 6). Figure 6.1 provides a summary of this comparison for major US cities, although there is no indication that these estimated emissions are for the same year.

Figure 6.1

Per capita CO2-equivalent emissions in various cities in 2009.

source: New York City 2010: 6

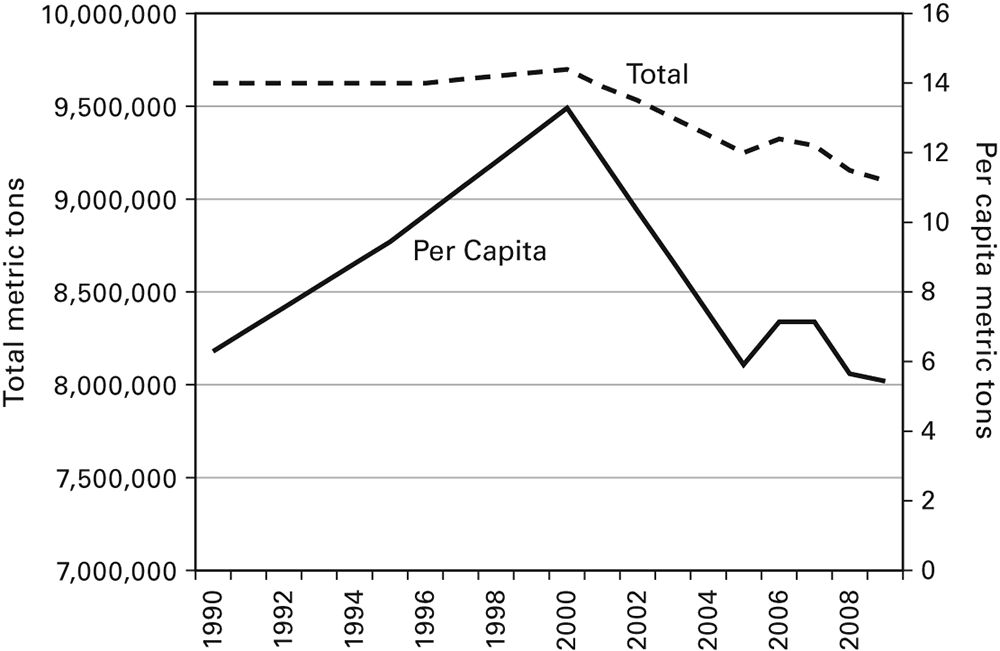

Some cities have been working on their greenhouse-gas inventories for a number of years and are able to report trends and changes. Seattle’s 2009 Climate Action Plan Progress Report presents information for 1990, 2005, and 2011. According to the report (Seattle 2009), total emissions of greenhouse gases in the city have declined to such an extent that the city can claim to have met its 2012 target of a 7 percent reduction from the 1990 level, although a significant amount of the reported reduction actually occurred as a result of “carbon offsets” purchased by the city’s electric utility company. Portland’s 2009 Progress Report, released in December of 2010, presents estimates of greenhouse-gas emissions for 1990, 1995, 2000, and 2005 through 2009 (Portland 2009). These estimates, shown in figure 6.2, suggest that Portland’s total emissions have decreased 15 percent since 2000 and its per capita emissions have decreased 22 percent over the same period. In terms of both total and per capita emissions, Portland seems to have already achieved reductions below the 1990 base line. Of course, reductions in emissions of greenhouse gases in Seattle, in Portland, and in other cities may well have occurred largely because of the nationwide economic downturn that began in 2007. Whether cities can meet their targets in the future, when their respective economies improve, remains to be seen.

Figure 6.2

Total and per capita CO2-equivalent emissions (metric tons), Portland, Oregon, 1990–2009.

source: Portland 2009

Increasingly, cities have turned their attention toward climate adaptation—that is, toward efforts to understand the impacts that climate changes are likely to have on the city and to formulate plans to be prepared for these changes. Adaptation has become an important element of cities’ sustainability and resiliency programs for at least two related reasons. First, cities seem to be experiencing weather events that might be tied to rising temperatures, such as sea-level rise, inundation during storms in coastal communities, and increased flooding. Recognition of these impacts has sometimes come as a result of new estimates from federal and state agencies, and sometimes as a result of private and public insurance rate increases. Second, adaptation seems to be a response to recognition that climate change is happening and will continue to happen even if a city manages to reduce its carbon emissions. In view of global carbon emissions today, the climate effects will likely continue to be felt for decades even if carbon reductions meet their future targets. Regardless of the reasons, adaptation efforts have become part of the planning efforts of many cities.

International Organizations in Support of Sustainability in Cities

The city-based pursuit of sustainability, both in the United States and elsewhere, has received considerable assistance from the international community of organizations. Numerous non-governmental organizations have provided technical and financial assistance to cities that wish to adopt and implement sustainability and related policies and programs. Two of these organizations, already mentioned earlier in this chapter, are ICLEI—Local Governments for Sustainability and the Clinton Foundation.

The International Council for Local Environmental Initiatives (ICLEI) was founded in 1990 by an initial group of 200 local governments from 43 countries that convened for the first World Congress of Local Governments for a Sustainable Future at United Nations headquarters in New York. Its World Secretariat is in Toronto and its European Secretariat is in Freiburg, Germany. Its first international programs were Local Agenda 21, a program promoting participatory governance and local planning for sustainable development, and Cities for Climate Protection. In 2003, the ICLEI’s governing council acknowledged a broadening mission and mandate of the association, and renamed the association ICLEI—Local Governments for Sustainability. At present the ICLEI has offices in Canada, in the United States, in Europe, in Asia, and elsewhere. Its primary mission has been to provide extensive advice and technical assistance to cities seeking to understand the “best practices.”

The Clinton Foundation, founded by former President Bill Clinton and headquartered in New York City, includes within its mission an effort to work with cities of the world to mitigate climate change (Clinton Foundation 2011). Its C40 initiative involves working across many different domains and program areas to improve the quality of life in the megacities of the world. The foundation’s efforts have focused largely on providing access to technical and financial assistance to help cities improve their biophysical environments in cost-effective ways.

Among the other NGOs that have become involved in working with cities on sustainability-associated programs are the World Bank’s Sustainable Cities Initiative, the International Institute for Sustainable Development, the International Monetary Fund, the World Water Council, and the Urban Water Sustainability Council. In the United States, supportive organizations include the National League of Cities’ Sustainable Cities Institute, the United States Conference of Mayors’ Climate Protection program, and the International City Management Association’s Center for Sustainable Communities. The nonprofit sector in the US and its counterparts in other countries have provided extensive support for the national and subnational support of sustainability, as is discussed throughout this volume.

Sustainability in Cities: A Summary

This chapter has focused on local governments’ policies and programs. It has looked at the efforts made by cities around the world with special emphasis on cities of Western Europe and North America with an eye toward documenting their sustainability policies, programs, and outcomes. It has also provided descriptions of efforts in China and the Middle East to create sustainable cities from scratch, with special attention to Tianjian Ecocity in China and Masdar City in Abu Dhabi.

Analyses of sustainability and climate-protection policies in US cities have endeavored to understand the specific programs these cities have adopted and implemented, and to develop explanations for why some cities seem to be willing to do so much more than others. San Francisco, California, Seattle, Washington, Portland, and Denver have surpassed other US cities in their public-policy commitments to sustainability. Other cities, among them Virginia Beach and Wichita, have not been willing to make sustainability a priority. There are numerous reasons for these differences, including differences in the presence of significant groups and organizations advocating that city governments establish more sustainability-related programs. When information and knowledge are lacking in cities, a number of international organizations have been active in helping.