Chapter Twenty-Three

Buckley Slams Vidal as a Sexual Deviant; Vidal Labels Buckley “A Closeted Old Queen”

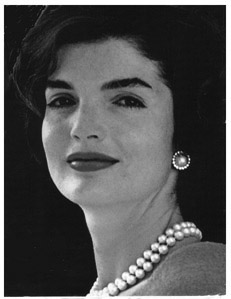

Behind the Scenes, Jackie Gets Involved

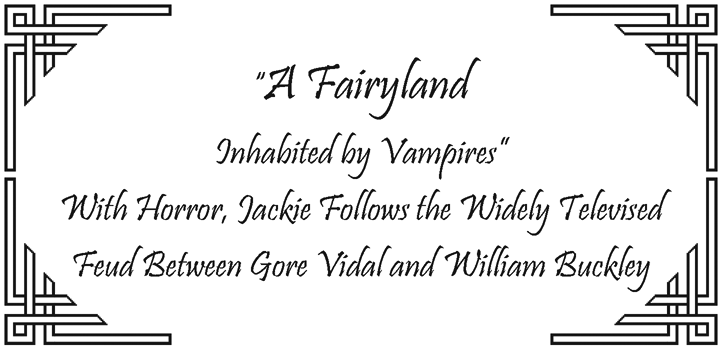

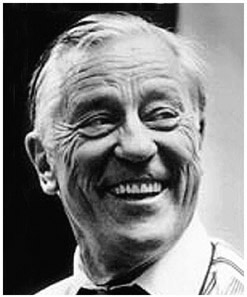

Left photo: In 1968, during the Democratic Presidential nominating convention in riot-plagued Chicago, ABC hired right-wing commentator William F. Buckley, Jr. (left) to face off with Gore Vidal (right, with only the back of his head showing), for a nationally televised debate. The moderator was ABC-TV’s Howard Smith (right photo).

In front of millions of TV viewers, “Mr. Cool” (a reference to Buckley) lost it and threatened Vidal with physical violence, calling him a “queer” in response to charges of Nazism.

Despite her role as the uncrowned Queen of Democratic Party politics in America, and her status as the widow of its assassinated torch-bearer, Jackie refused to attend the 1968 Democratic Convention in Chicago. But her absence resulted from years of soul-searching dialogues with her late husband. As early as 1960, she and JFK, when he was running for president, often talked about where their lives would be in 1968.

According to their plan, he would be retiring from the White House, assuming he’d be re-elected in 1964. They discussed what they might do during retirement, where they might live. Jackie suggesting they might travel frequently. She recommended that they might maintain apartments in New York, London, and Paris, while keeping residences in Palm Beach and Hyannis Port.

At a party, William Buckley, Jr., confronted Jackie, describing his plan to write a book exploding Camelot as a myth of her own making. He wanted to entitle it The Dark Side of Camelot. Ironically, in 1997, three years after Jackie’s death, investigative reporter Seymour M. Hersh wrote just such a book, with that title.

“I have met some despicable excuses for a man in my life,” Jackie told Gore Vidal. “The Buckley thing is at the top of my hate list.”

Her plans changed drastically when 1968 actually came, and Robert Kennedy was assassinated in Los Angeles after winning the California primary.

Originally, and until she changed her mind, Jackie had agreed to be “showcased,” with fanfare and klieg lights, at the Democratic Convention, which she hoped would lead to a nomination of Robert Kennedy (Bobby) as the party’s candidate in the upcoming challenge from the Republican right. That challenge would be in the form of Richard Nixon, whom—although she masked her contempt—she had grown to despise.

Jackie had no enthusiasm for Lyndon B. Johnson’s choice—Hubert Humphrey—as head of the Democratic ticket and its candidate for president.

He’d run against her husband in the West Virginia and Wisconsin primaries in 1960, and she had developed an intense dislike for him and his “down-home” approach to campaigning. “The man has no class,” she told friends. She cited a “cornpone” picture of the Humphreys holding hands with their “dull-looking children” in front of an extremely modest shingle-sided cabin.

As the convention opened, Jackie had so little interest that she didn’t plan to follow the proceedings. But she changed her mind when she read that ABC-TV had hired both Gore Vidal and William Buckley, Jr., to cover the convention in Dallas. She later admitted, “I watched the proceedings like a cobra about to strike.”

“I’ll Sock You in Your Goddamn Face”

On Nationwide TV, A “Porno-writing Queer” Dukes It Out With a “Crypto-Nazi”

Because of Bobby Kennedy’s feud with Vidal, her friendship with him had been put into storage. But she despised Buckley—“I loathe him,” were her exact words.

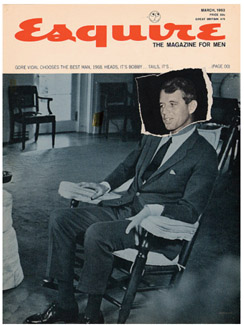

Buckley sued Vidal (photo above) for his response to an attack Buckley had written about him in Esquire. “Finally, the right-wing creep backed down and dropped the suit,” Gore said. “But I had to pay my lawyers for his crazed madness. One never forgives that. Hopefully, the fanatical Buckleys of America will be stopped one day before they destroy the country.”

Her disdain for this right-wing commentator was not entirely political, but personal.

At least some of it derived from their encounter, in 1965, at a party in Manhattan, to which she was escorted by Ted Sorensen. There, he confronted her to tell her, provocatively, that he was contemplating writing a book entitled The Dark Side of Camelot.

Buckley was very frank with her, informing her that the book would revolve around the theme that her husband had been one of the worst presidents in U.S. history.

“I want to write about how Kennedy used his old man’s bootleg millions and his Mafia links to gain power,” Buckley told an astonished Jackie. “I’ll write about his charm—your charm, too—but reveal how both of you used it like a weapon.”

“I will charge that Kennedy followed only his own moral code, which is actually immoral. He virtually did what he wanted. He was completely reckless, a womanizer from hell. You know that better than anyone. I also want to reveal how he lied to the American people about his health. I plan to suggest that Kennedy’s very recklessness had gotten out of control, and that he was on the dawn of being publicly disgraced, which would have cost him the presidency in 1964.”

“I plan to suggest that he, with your help, masked personal weaknesses which cast a dark shadow over the House of Camelot.”

“He seduced the public and used you as a kind of star magnet to avert attention from his private life.”

“I am sorry to do this to you, Mrs. Kennedy, but I am far more interested in history getting it right than in offending one lady, who I understand has had her own detours down the primrose path.”

Having listened to him with jaw-dropping astonishment, Jackie withdrew. In a quiet rage, she said, “Please, Mr. Buckley, try not to appear in the same city with me. Your stench is overpowering, worse than the poison gas used on Allied soldiers in the trench warfare of World War I.” Then she turned and walked away, leaving the party.

Sorensen later reported to former White House aides and Kennedy loyalists, “Never in my life had I ever heard Jackie take such a forceful stand against anyone. But it was understandable. Here was this obnoxious right-winger notonly insulting her to her face at a party, but threatening to explode the so-called Myth of Camelot, which she’d worked so hard to create. He was threatening to reveal all the dark secrets of the Kennedy administration, which she had strived to keep from the public. I had never seen her so enraged.”

Vidal, a spokesman from the American left, and Buckley, the darling of the far right, had long been ideological enemies. Buckley even suggested that Vidal was not really an American. “He lives as an expatriate far from these shores, and once applied for citizenship in Switzerland, which would have required a revocation of his American passport.”

Executives at ABC decided that they would make “good television” their priority during their coverage of the 1968 Democratic Convention in Chicago, an event that ultimately nominated Hubert Humphrey as the Democratic candidate for U.S. president, a man who had previously functioned as Lyndon Johnson’s vice president.

[During the 1968 presidential elections, Humphrey would eventually lose to Richard Nixon.]

In utter astonishment, Jackie watched the convention and the TV commentaries it catalyzed, including the joint appearance of Vidal with Buckley. She was motivated not just with Buckley’s vow to tarnish her late husband’s reputation, but Vidal’s increasingly cynical viewpoint about the Kennedy “Dynasty” as well. He’d become rather hostile about issues associated with Camelot, and had written devastating critiques of Bobby too.

In spite of that, Jackie was willing to root for him. As she told Sorensen, “In spite of some past difficulties I’ve had with Gore, he’s still on our side. At this convention, he’s become the holder of the flame against this horrible man, Buckley. I have never wanted to slap someone’s face as much as I wanted to slap his at that party. How dare he talk to me that way? I hope Gore makes mince pie out of this man who opposed everything Jack ever did.”

She was watching a televised broadcast of the Convention on the evening of Wednesday, August 28 at 9:30 EST, and would never forget what she saw.

ABC anchorman Howard K. Smith, who was stuck in the middle as a moderator, would never forget it either, even though his anchor desk was in another room, separate from the two commentators.

Gore and Buckley were not strangers to each other, having debated twice before—first in September of 1962 and again in July of 1964, with TV host David Susskind functioning as moderator in both of those instances.

What was happening outside the convention hall was more intriguing than the speeches being made inside. Chicago Mayor Richard Daley, later denounced as “a Gestapo leader,” had mobilized a massive police force to control violent protests against the Vietnam War. Most of that war had unfolded during Lyndon Johnson’s administration, but it had been launched—although on a much smaller scale—by JFK, or so his critics claimed.

On the streets of Chicago, the battle between the police and the mostly young protesters, as described by one reporter, “involved gross police brutality as Mayor Daley’s cops beat the shit out of the yippies and hippies assembled to witness the Democratic Party’s coronation of miserable old Humphrey.”

TV cameras focused on young, presumably American-born men waving the Viet Cong’s flag.

That night, some ten million Americans, along with Jackie, had tuned in to ABC to watch the Vidal/Buckley debates, sandwiched into the barely controlled chaos unfolding both inside and outside the Convention Hall.

Vidal defended the protesters. He even claimed that the waving of the Viet Cong flag fell under the U.S. Constitution’s guarantee of Free Speech.

The Chicago riots of August of 1968 may have cost the Democratic Party the presidential elections. Using their batons like clubs, the Chicago police, under Mayor Richard Daley (upper photo), were violently beating Vietnam protesters, their actions projected on hourly newscasts into the horrified consciousness of viewers everywhere

For Buckley, the revolt of the left-wingers represented heinous anarchy. Vidal interpreted it differently, alleging that “The police state and the American empire were murdering free speech.” Both men were, in the words of one writer, becoming “angry, defensive, and aggressive,” their moods within the Chicago TV studio reflecting opposing sides in the pitched battles outside on the streets.

As early as 1962, Buckley had been referring to Vidal, in public, as “a pinko queer.” He threatened that if Vidal wanted to sue him, “I shall fight by the laws of the Marquess of Queensberry.”

In contrast, Buckley, “was hissing like a cobra,” [Vidal’s words] during the attacks he was spewing on the young people rioting in Grant Park. He accused them of “begging the Viet Cong to kill American marines.”

Before that infamous television broadcast, Jackie had watched Vidal and Buckley engage in mutual bickering. One Chicago newsman defined it as “hysterical combat.”

As their altercation intensified, Buckley defined the protesters as “pro-Nazi.”

In immediate response, Vidal charged, “As far as I am concerned, the only sort of pro-crypto Nazi I can think of is yourself.”

Buckley exploded in anger. A notorious homophobe, he shot back. “Now listen, you queer! Stop calling me a crypto-Nazi or I’ll sock you in your goddamn face and you’ll stay plastered!”

TV audiences across the country were stunned. So was Jackie.

She had been watching the debates with her friends Ben and Toni Bradlee. Of all members of the Washington press corps, Bradlee at The Washington Post had been the closest to her husband. However, in 1975, after he published his book, Conversations with Kennedy, Jackie dropped him from her list of friends.

“Jackie jumped up and glared at the TV set as if she could not believe what had transpired,” Bradlee later said.

Howard Smith, the debate’s anchorman later said, “Mr. Cool [a reference to Buckley] lost it that night. The ice cube turned into a ball of fire. Perhaps this was the first time in his life that Buckley threatened physical violence against those who didn’t agree with his position.”

Bemused and jovial, Ben Bradlee (above) and his wife, Toni, had long been friends to both Jack and Jackie. Often, they went out as a foursome.

Ben’s friendship with Jackie continued during the post-assassination era—that is, until 1975, when, in Jackie’s eyes, he committed an unpardonable sin. He wrote a book about his conversations with JFK.

“I would expect physical violence from Norman Mailer, not from Buckley,” Vidal later said. “I must have really crawled under his skin. Perhaps I labeled him correctly after all. He’s a representative of the lunatic right, where Goebbels would have felt at home.”

“Actually, he was the first to use the word ‘Nazi,’” Vidal later said. “My repeating it was a slip of the tongue. I had meant to say ‘fascist’ instead.”

Buckley later said he should not have used the word “queer.” But he couldn’t resist a dig, “Gore Vidal, however, is the Evangelist for bisexuality.”

Ben Bradlee later reported that watching the Vidal/Buckley broadcast had “ravaged” her [Jackie’s] mind. She ordered a strong drink from her maid—and later, a lot more. She feared the fallout from that broadcast had only begun—and she was right!”

—Gore Vidal

As the new year of 1969 dawned, Vidal seemed willing to put the notorious Chicago TV incident behind him.

Buckley, however, was not. Still fuming, he called Harold Hayes, a high-placed editor at Esquire, for permission to submit an article attacking Vidal. He wanted it to appear in the magazine’s August issue. But he had one condition: “Will I be allowed to charge Vidal with homosexuality?”

Hayes thought Esquire’s lawyers might agree to that. “Permission granted, unless I call you and tell you otherwise.”

That afternoon, in his role as a provocative editor with a scandal to publicize, Hayes reached Vidal at his home in Ravello along the Amalfi coast in Italy. He told him about Buckley’s plans and offered him space in Esquire for a rebuttal, with the understanding that he’d be able to evaluate and/or attack Buckley in an articles that would run in the magazine’s September issue.”

Vidal agreed, but protested. “Why are you giving space to this dimwit? He’s mad. He exists in the mind of the public only because of his attacks on me.”

More and more of Jackie’s former friends and confidants were, in her words, “betraying me.” She was horrified when someone brought her the March, 1963, issue of Esquire in which Vidal attacked Bobby Kennedy as unfit to ever become President.

Hayes personally liked Buckley but hated his politics: Hayes didn’t particularly like Vidal, but endorsed many of his political views. The editor saw the obvious: Mutually aggressive articles by Vidal and Buckley, each attacking the other, would be good for circulation.

After Vidal’s attack on Bobby Kennedy, circulation had soared. The cover of Esquire’s issue that contained it featured a replica of Bobby sitting in President Kennedy’s White House rocking chair. The headline read—WHEN BOBBY TAKES OVER.

Jackie interpreted Vidal’s article as a “revenge piece,” compiled in retaliation for Bobby kicking Gore out of the White House in 1961. In it, Vidal had labeled the Attorney General as a McCarthy clone—“a graceless, illiberal, and puritanical politician, unqualified by temperament or judgment to be President.”

Bobby and Jackie were furious at Vidal.

When she heard of Buckley’s upcoming attack on Vidal in the same issue, Sorensen said that Jackie was almost forced to take Vidal’s side and forget about his attack on Bobby. She told Sorensen, “Gore is just the advance soldier in the field that Buckley wants to slay. As you know, his ultimate aim is to ridicule and mock Jack’s accomplishments in the White House.”

***

According to the lawyers at Esquire, the first draft of Buckley’s article on Vidal was libelous. Even if it were cut and rigorously edited, publishing it would still represent a bit of a risk for the magazine, they said.

Fred Kaplan, Vidal’s biographer, wrote: “Buckley’s article seemed not only inaccurate, in fact, but whiningly self-serving and viciously homophobic. It was a theocracy of sorts, a justification not of God but of Buckley, an egomaniacal self-projection so vast that it seemed Satanic, the devil in the guise of an infinite self-righteous rectitude.”

As stated by Buckley, Vidal was a “money-grabbing pornographer—Myra Breckinridge is pure pornography—whose immorality was purposeful, self-conscious, and serving—and that is a sin. He is also a sexual deviant, and that is an illness. Unlike most sick people, Vidal does not want to be cured.”

Before publication, Hayes sent Vidal a copy of Buckley’s article, tacitly seeking his permission to publish it. He feared Vidal might sue.

As evidence of their sense of editorial “fair play,” Esquire planned to provide Vidal with a chance to respond to Buckley’s attacks within its subsequent issue. By now, however, Buckley was demanding that only his attack on Vidal be run, and that Esquire refrain from publishing Vidal’s rejoinder.

When Esquire’s August issue appeared on newsstands nationwide, it managed to enrage not only Vidal, but also millions of homosexuals and their sympathizers, Jackie among them.

In his article, Buckley labeled Vidal as an apologist for homosexuality. “The man in his essays proclaims the normalcy of his affliction—that is, homosexuality—and in his art, the desirability of it. Vidal is not the man who bears his sorrow quietly. The addict is to be pitied, and even respected, not the pusher.”

In his own defense, Vidal composed and submitted his response, as requested by Hayes, for Esquire’s September issue. He cited damaging evidence that Buckley was not only a “homophobe, but anti-black, anti-Semitic, and a warmonger.”

He also came up with some damaging evidence, claiming that in 1944, Buckley, along with “unnamed siblings,” vandalized a Protestant church in their hometown of Sharron, Connecticut, after its pastor’s wife sold a house to a Jewish family.

Surprisingly, the actress/entertainer, Jayne Meadows, who was privy to some of the more sordid details associated with the Buckley family, provided “a lot of juice to Gore,” although she requested that her name not be cited.

[Jayne Meadows (born 1920) was the wife and business partner of talk show host/comedian Steve Allen, and the sister of Audrey Meadows, famous for her character of Alice Kramden in The Honeymooners.]

Actress Jayne Meadows, of all people, came to the aid of Gore Vidal by supplying “incriminating evidence” against the Buckleys.

Some of Vidal’s material had to be excised by Esquire, particularly the charges that Buckley was a closeted homosexual himself. Vidal did accuse him of having “faggot logic,” even suggesting that “where there is smoke, there is a fire.”

He claimed that many TV viewers had cited Buckley’s “effeminate manners and speech, behavior that made him sound queenlike.”

Jackie, too, had heard rumors about Buckley, particularly when she dated one of his classmates from Yale. Her beau at the time told her that Buckley had been known on campus as a homosexual.

Maneuvering behind the scenes, Jackie asked Onassis to intervene. Onassis’ lawyer, Roy Cohn, a homosexual himself, was one of J. Edgar Hoover’s closest friends. She knew that Hoover, who had files on everyone, would obviously have investigated Buckley.

Onassis agreed to ask Cohn to find out “the dirt” in Buckley’s file, and the ever-diligent Cohn did just that, reporting his findings the following week.

In February of 1964, Town and Country published a cover story on Aristotle Onassis. There was a certain irony in the headline: WHAT ONASSIS WANTS ONASSIS GETS. At the time, the editors didn’t know that Ari wanted Jackie.

The most damaging evidence about Buckley’s homosexuality came from a former classmate [name withheld] at Yale. At the time the file was made available to Jackie, the Yale man was a successful stockbroker in New York with a wife and three children.

He had told the FBI that to stay on the football team, he had to maintain a certain grade average, and that whereas he had been a poor student, Buckley was considered a scholar and an intellectual.

“I needed help, and I couldn’t afford to pay for extra tutoring,” the former Yale man said. “I caught Buckley checking me out in the shower room. He seemed fascinated by my cock. I figured out what to do. In exchange for his private tutoring, I would let him perform fellatio on me—nothing else. When I presented the offer to him, he willingly agreed. Our special relationship went on for the rest of the semester. I graduated from Yale, and Buckley took care of me, because I was perpetually horny.”

In February of 1968, Esquire devoted a cover issue to the notorious homosexual lawyer, Roy Cohn, who often handled legal matters for Aristotle Onassis.

In a murky payback, Jackie asked Ari to pay Cohn for blackmail evidence that Cohn’s closest friend, FBI Director J. Edgar Hoover, had accumulated on William Buckley, Jr.

Secretly, Jackie had the file copied. A member of Onassis’ staff had it delivered anonymously to Gore’s residence to use in any way he saw fit.

***

Buckley did not remain idle while Vidal was digging up a homosexual scandal from his past. He, too, had a detective agency investigating his adversary.

It was learned that Vidal, throughout his life, had often had sex with underage hustlers. Buckley had eyewitness accounts from some of the teenage boys Vidal had picked up on Santa Monica Boulevard who claimed that at the time of their encounters with him, they were under sixteen, maybe in one instance a well-developed thirteen.

Like Michael Jackson in a TV special, Vidal admitted in his memoirs, Palimpsest, that he was “attracted to adolescent males—like most men.”

The agency discovered that Vidal had taken several “Golden Cock Tours” to Thailand as they were labeled. These tours were often booked by pedophiles, the majority of the participants coming from German cities, especially Berlin. But the detectives had no way of gathering information about Vidal from Bangkok.

Vidal repeatedly denied that he was a member of NAMBLA, the North American Man/Boy Love Association. He did, or so it was once reported, endorse NAMBLA’s goal of legalizing “intergenerational sex.” Privately, Vidal, a sexual sophisticate, said, “Sometimes, it takes a nubile twelve-year-old boy to get a rise out of an 84-year-old man.”

Vidal did make an appearance at a NAMBLA fund-raising in 1978, although he claimed it was to take a stand against Salem-like witch hunts aimed at persecuting gay people. Viewed harshly, his presence was later criticized. He was falsely charged with favoring the rape of young boys, which he had never endorsed.

From afar, Jackie observed how Buckley vs. Vidal lawsuits, threats of exposure, and counter-suits were mushrooming everywhere. Her ultimate conclusion, as told to Sorensen, was that Vidal and Buckley “found so much homosexual scandal about each other that they had to declare a Mexican stand-off before seriously damaging each of their reputations.”

“I knew enough, though, to keep my son John away from both of them,” Jackie said.

***

After Vidal delivered the draft of his article to Esquire, Buckley, in advance of its publication, announced his lawsuit.

Pre-emptively, and not without touches of paranoia and personal vanity, Buckley sent the following telegrams to twenty American magazine publishers:

“Last August, I was defamed on network television by Mr. Gore Vidal. Mr. Vidal has not retracted his libel or apologized to me. On the contrary, he has sought to give renewed currency to that libel and to launch others, to which end he submitted a manuscript to Esquire which Esquire declined to publish because it was defamatory and untrue. Mr. Vidal’s activities have left me with no other recourse than a lawsuit, and accordingly, I have filed suit against Mr. Vidal for $500,000 in damage.”

By sending these telegrams, Buckley hoped to prevent Esquire from publishing Vidal’s rejoinder in their September issue.

This began a legal waltz between Vidal and Buckley—with the horrified involvement of Esquire— that would drag on for three years. Jackie had closely watched developments before and after the publication of both articles. Aware of the legal heat generated by the affair, Hayes demanded that only facts that could be reasonably proved be allowed in his magazine, or else free speech about political stances which seemed libel-proof. Even after their cuts and edits, both articles still seemed explosive.

Endless meetings with lawyers and precautions preceded publication, but finally each of the two articles was printed. Buckley as promised sued in the United States District Court, although at this point, he’d upped his claim for damages to $1 million.

Buckley told the press, “I have been defamed. Vidal has accused me of being a Nazi, a homosexual, a war lover, and an anti-Semite.”

Buckley’s attorney requested the court for a summary judgment, at which time the judge dismissed Vidal’s countersuit, virtually labeling it as a “nuisance suit.”

Buckley’s suit never made it to court. Esquire admitted no culpability, but it did agree to pay Buckley’s legal fees up to $115,000. However, Vidal was left dangling to pay his own lawyers, with no comparable offer of reimbursement from Esquire.

In the immediate aftermath, Buckley summoned a press conference in which he lied, falsely claiming that he had won the case against both Esquire and Vidal. He said Esquire had “disavowed Vidal’s charges against me and in its November issue would publish a retraction.”

No such agreement had been reached, and no such retraction ever appeared.

“Let Vidal pay his own unreimbursed legal expenses, which will teach him to observe the laws of libel,” Buckley crowed.

Throughout the rest of his life, Buckley would maintain the fiction, at parties and to his friends, that the court had interpreted Vidal’s article as defamatory and that Esquire “had to pay up” for having published it.

Privately, Vidal said, “The closeted old queen is just deluding herself until the end. She lives in a fairyland peopled by the lunatic fringe and at night, dances with vampires in KKK drag.”

It is not known, but Onassis, through Cohn, might have blackmailed Buckley into abandoning his plans for a book that would have exposed Jackie, JFK, and the myth of Camelot. Jackie personally did not want to “leave my fingerprints on any of this maneuvering. Let Cohn do his job. Let’s face it: Ari pays him enough!”

—Gore Vidal

The feud and charges of libel continued into the 21st Century. Buckley died in 2008, Vidal outliving him, dying in 2012.

However, in 2003, Esquire republished Vidal’s attack on Buckley, in a book entitled Esquire’s Big Book of Great Writing. Apparently, the editor of the anthology was not familiar with the long-ago lawsuit, much to the horror of Esquire’s administration.

Buckley once again filed suit for libel, and Esquire agreed to settle for $55,000 in attorney fees and $10,000 in personal damages to Buckley.

When documents associated with the Vidal/Buckley debate became available on the internet, viewers weighed in with strong opinions. “Sarah Heart-burn” claiming, “I will make my hands bleed applauding for Vidal.” She attacked Buckley’s suggestion that “HIV-sufferers be tattooed—on the ass.’ How the holy fuck can the man be touted in the press as an erudite, wise, political spokesman?”

Upon hearing of Buckley’s death, Vidal said, “Although one is not supposed to speak ill of the dead, Buckley was often drunk and out of control. He was always a spontaneous liar on any subject that his dizzy brain might extrude.”

He concluded that Buckley was a “most hysterical right-wing queen, much admired by the fascist press in America that merely published Buckley’s own delusional evaluation of himself.”

In 2008, in the wake of Buckley’s death, Deborah Solomon of The New York Times asked Vidal, “How did you feel when you heard that Buckley had died?”

“I thought hell is bound to be a livelier place with him in it,” he said. “Buckley joins forever those whom he served in life, applauding their prejudices and fanning their hatred.”

As for Jackie, she went to her grave in 1994 detesting Buckley. Whenever he appeared on TV, she switched channels.

In October of 1972, Jackie threw a surprise party at Manhattan’s El Morocco, celebrating the fourth anniversary of her marriage to Aristotle Onassis—not that that marriage had anything to celebrate. Her guest list included Doris Duke, Rose Kennedy, Oleg Cassini, and such New Frontiersmen warriors of yesterday as Pierre Salinger.

Surprise of surprise, she invited William Buckley, Jr. He was shocked, knowing how much she despised him, but he attended anyway. He wished he hadn’t.

Years before, he had infuriated her at a party, when he had cheerfully informed her that he was about the expose the myth of Camelot in a book. She waited for almost a decade before confronting him privately at her El Morocco party to inform him of the incriminating data that the Kennedys had amassed on him. “Back off!” she threatened him, “or we’ll destroy you.”

He got the message.