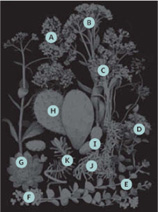

Hardy succulents: A Sedum telephium ‘Atropureum’; B S. telephium; C S. spurium ‘Tricolor’; D S. kamtschaticum; E S. spurium; F S. makinoi ‘Ogon’; G Sempervivum hybrid; H Opuntia humifusa; I O. fragilis; J Sedum lineare ‘Variegatum’; K Euphorbia myrsinties.

Every cactus is a succulent, but not every succulent is a cactus. A succulent is a plant that stores moisture in its stems and fleshy leaves. Cacti don’t even have leaves; they vanished eons ago. Photosynthesis takes place instead through the green skin of modified stems swollen with water. Their leaves are gone but not forgotten; they’ve turned into the spines that arise from areoles—the physical characteristic that distinguishes cacti from all other plants. The spines are for protection of course, but they also comb moisture from fog and dew.

The drought-loving cacti are indigenous to North American deserts from Mexico north to the Southwest and Colorado, and some species come from the dryland plains of Montana and Alberta, Canada. Good garden practice advocates planting the right plant in the right place. Very fast-draining soil in plenty of sun is a spot for cold-hardy cacti. You can also create the right soil mix in a sunny spot. I grow several cacti in nearly pure three-eighths-inch crushed rock (gravel) to which I’ve added about a third more garden loam.

Gardeners think of cacti as only coming from hot, dry climates. But there are humidity-loving tropical jungle species like the Epiphyllum (here). There are also thousands of other frost-tender succulent species from around the world, and many could be additions to frost-free gardens in the South and coastal California, where temperatures do not dip below freezing. Aeonium, Aloe, Crassula, Delosperma, Dudleya, Euphorbia, and Pelargonium are just a few.

Cold-hardy succulents are either deciduous or evergreen. The evergreen ones, including cacti, expel stored moisture in winter, so that freezing water will not rupture their cells. By winter’s end, the shriveled plants are colorless, but in short order, they plump up, grow, and blossom.

Sedum varieties are frequently grown succulents for cold climates. They range from tiny ground covers often called stonecrops, to the eighteen-inch-tall versions of live-forever: Sedum telephium and S. spectabile. The taller sedum species and hybrids want well-drained soil and good air circulation, similar to companion plants like lavender, Russian sage, coreopsis, and Rudbeckia (black-eyed Susan).

Short sedum varieties are traditional rock garden plants, where they may mingle with diminutive “alpines” like rockcress (Arabis spp.), sea pink (Armeria spp.), basket-of-gold (Aurinia saxatilis), pinks (dwarf Dianthus spp.), moss pink (Phlox subulata), succulent hen-and-chicks (Sempervivum varieties), and creeping thyme (Thymus spp.). These days, you may find these succulents planted atop buildings as energy-saving “green roofs.”

Succulents in Judy Bradley’s San Diego water-wise garden with fuzzy Kalanchoe beharensis, dark red Aeonium arboreum ‘Schwarzkopf’, and colorful Echeveria varieties.

A border of Aloe vera plants in an Arizona garden. The tubular blossoms are favorites of many of the hummingbird species that can be seen in the American Southwest.