The apple doesn’t fall far from the tree.

— Anonymous

June 3, 1939: Hitler was putting the finishing touches on his diabolical plan to ravage Europe. FDR was halfway through his historic twelve-year stint in the White House, and Winston Churchill was in political limbo, his best days still ahead. The Oscar-winning Gone with the Wind was in theatres. And I was about to make my first move. I was born in Lewisporte, Newfoundland. Well, nearly. My mom, with lots of practice delivering God’s little soldiers, opted to sever my umbilical lifeline aboard a small boat in Notre Dame Bay, minutes before we tied up to the wharf, on the very eastern edge of the North American continent, just 1,800 miles west of Ireland.

US Supreme Court Justice Stephen Breyer, addressing an American Bar Association luncheon in Washington, DC, in August 2007, unwittingly gave me the ultimate trivia question to stump even the most finicky US history buff. The question: Despite the stipulation in the US Constitution that no person except a natural born citizen . . . shall be eligible to the Office of President, which US president probably didn’t meet the test?

Mr. Justice Breyer told us that a future US president may have been born in Canada, at Stanbridge East, Quebec. The parents, patriots certainly, but maybe also clairvoyants, had the good sense to whisk the newborn, belly button still damp, across an international border so he could claim citizenship in the land of his parents, not the land of his birth. Chester Arthur12 may have had the credentials to be the world’s first dual citizen, though he never did apply for a Canadian passport. His loss! Like Arthur, I was hatched on the way to somewhere else.

I wasn’t born a Canadian. Rather, I got my start in life in a fiercely independent dominion of 300,000 souls clinging to a remote island in the North Atlantic, Newfoundland, 1,000 miles northeast of New York.

The Simmons clan

There were fifteen of us in the Simmons litter. I’m number eight. Dead centre. Halfway. My dad, Willis, chatting up a girlfriend I was trying to impress, put it this way: “When he was hatched, I took one look and decided to keep going!” Dad was right to keep going. Arrival number fifteen is my youngest sister, Cavell. She has made the family proud by her thirty-five years’ service to Canada as a military nurse.13 Ten of the brood hung around to experience the joys of adulthood. Six of us are still above ground, strewn until recently from a perch on Vancouver Island to bustling St. John’s, Canada’s oldest city.

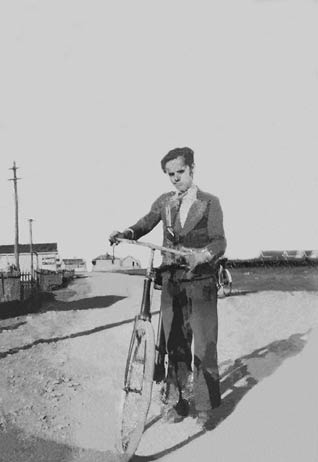

Bishop’s Falls, Newfoundland and Labrador, 1952. At the age of thirteen, I bought my first wheels for ten bucks. (Author photo)

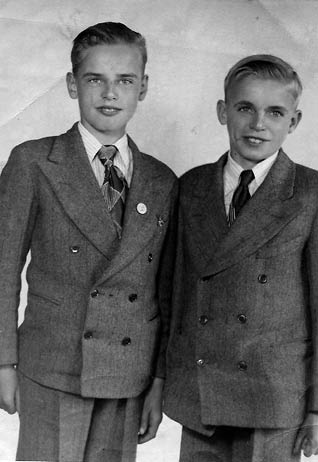

Bishop’s Falls, 1953. My brother Howard, right, and I donned our Sunday best for the itinerant photographer. (Author photo)

My brother Noel left us much too soon at forty-eight. His joie de vivre, ingenious schemes, madcap adventures, and fierce loyalties captivate, enrich and inspire us still. Howard, my protective big brother during the formative years, died in 2015. His easygoing demeanour masked a quick, creative mind; his generosity, love of nature, wacky wit, and fix-the-unfixable ingenuity knew no bounds.

Pasadena, circa 1989. With four of my brothers. L-R: me, Scott, Howard, Dale, and Dave. Noel (inset) died at age forty-eight in 1984. (Author photo)

The near-sudden passing in February 2018 of my fabulous sister, Yvonne left a gaping void. Kindness and a calming disposition were her defining hallmarks. The family’s mother hen, she provided safe haven and nurturing for many, a role model for all.

Scott, my oldest brother, served as a volunteer member of the 9/11 cleanup team in New York. His doing so underscored both his trademark outreach and his lifelong quest for new challenges. Sadly, he passed away in May 2018, leaving a marvellous legacy of business acumen, caring, and humanity.

Go forth and multiply

Religious beliefs were a driving force behind the large families of yesteryear.14 The biblical injunction to “be fruitful and multiply”15 was the eleventh of the Ten Commandments and, like the others, was to be obeyed without question. And obeyed it was.

Both sides of my family tree heeded the scriptural edict. My mother had eight siblings, my father, seven. Of these, two died in infancy, and only my maternal Aunt Emma remained single, serving for over forty years as a Salvation Army officer. So, I had twenty-five aunts and uncles, most of whom produced large families, giving me armies of cousins. The Simmons-Williams-Simms-Cobb gene pool has sent hundreds out across Newfoundland, Canada, and the world, some in prominent roles as a missionary, diplomat, legislative Speaker, author, corporate director, business tycoon, Hollywood film actress, and university president.

A strong work ethic

Dad’s immediate forebears were from England’s West Country. Like tens of thousands of other people from Devon, Dorset, and Somerset, they came as indentured servants of fishing interests. My mother’s ancestry was Welsh and English. Her clan, too, had come to Newfoundland for similar reasons.

Willis Simmons and Ida Williams were both born into families with a strong work ethic. Grandfather Sam Simmons, boat builder and construction contractor, was a dour martinet who expected all to pull their weight. His three sons were conscripted into the workforce well before puberty, as were most of the daughters.

Herbert Williams, Ida’s father, and her mother, Maud Simms, were the offspring of fishing families. The father and his five sons took up the family trade as youngsters. One went on to become a prominent entrepreneur in building supplies and transportation, another in retail, and a third served as a merchant mariner during the Second World War and survived to tell the tale. The Williams girls, too, got an early start in bringing home the bacon. My parents, Willis and Ida, spared no opportunity to drill into us that same work ethic. The unkindest epithet Dad could hurl at you was, “You’re worse than a hangashore”—someone regarded as too lazy to fish; a worthless fellow, a sluggard; a rascal.16

That term certainly didn’t apply to my dad. By day, he was a carpenter with the railway. He spent most of his evenings in his backyard workshop fabricating various items for sale in the local community. His signature creation was the four-seater garden swing. His product line also included clock shelves and pincushions (for sewing needles and thread spools), both of which were emblazoned with one of three assertions: God is love, Jesus saves, Christ died for our sins. Employing these inscriptions had less to do with evangelical grandstanding than marketing! Another of his for-sale items, a flower stand, proclaimed no gospel message at all. It obviously targeted the agnostic niche market! Peddling Dad’s output was accomplished by his very own door-to-door sales force, my siblings and me.

Sliding into home plate

Dad could see humour in all things. The neighbour’s very obese wife was in a St. John’s hospital, 300 miles distant. For Joe, the doting husband, the nearest phone was at the railway station, just beyond our house. As he returned from his weekly phone call to the hospital, my dad asked, “Joe, how’s the missus comin’ along?” Obviously not familiar with the term “up and around,” Joe responded, “She’s up and hoppin’ around.”

The dramatic imagery of this obese woman’s newly acquired agility fired my dad’s imagination: “At that rate, Joe, she’ll be here by sundown—on foot!”

The chromosomes made me do it

Herbie Dart acquired his nickname for his agility and energy. As a youth, he and his friends would arrange ten puncheons17 in a row. The challenge was to leapfrog from one barrel into the next. Only he could reach the final barrel. Herbie Dart was my maternal grandfather. His daughter, Ida, definitely had his genes. My mother was intense and focused, had energy to burn, well-honed social animal instincts, and a fast, lethal, hinged-in-the-middle tongue. She could work a room better than Bill Clinton or Paul Martin, Sr18. A multi-tasker, though not a workaholic, she knew how to change gears, to relax, to have fun.

Like my father, I’m sawed off19. I’m saddled with his ducktail rear end, his warped sense of humour, his eschewing of confrontation. He was a very egalitarian and tolerant person who was at ease with all he met.

In sum, I’m a Simmons chassis that laughs, seeks compromise, and has no choice but to look up to almost everyone I meet. And I’m a Williams engine that propels, often at breakneck speed, and belches, always for a reason, laudable or otherwise.

Irreconcilable differences

Mom routinely drove my dad round the bend with her scathing denunciations, her non-stop energy, her impatience to launch the latest household improvement or community project. Gamblers, boozers, partygoers, adulterers. They topped the list of my mother’s prime candidates to be Lucifer’s eternal charges: “Hell is too good for that clique, that band of rogues.”

As fast as I put pictures of Doris Day or Kim Novak on my bedroom wall, using little dabs of a homemade flour-based adhesive, my crusading mother would tear them down in the continuing challenge of saving her boy from Satan’s clutches. Any female photo showing bare flesh below the chin or above the knee she deemed evil pornography. My mother had very definite ideas about many things. Her world was pitch-black and lily-white.

Dad saw a grey universe and functioned accordingly. Skipper, as the offspring often referred to him, saw people as individuals, not as exhibits to be categorized and labelled.

A “doctor” does double duty

In my early years, Mom was bedridden during the cold-weather season because of a rare disease, phlebitis. For an agonizingly long time, her condition had been misdiagnosed and, consequently, mistreated by a quack. The “doctor” whose patient she had been was in Lewisporte on a very different assignment. A few hours before a German U-boat sank the SS Caribou in the Gulf of St. Lawrence in October 1942, sending 137 passengers and crew to their deaths, he wired a telegram which read “Don’t sail on the Caribou” and promptly disappeared. Spies make themselves scarce once their cover is blown.

When the Simmons clan relocated to Bishop’s Falls, Dr. Davey Tulk quickly recognized Mom’s symptoms because his wife, Dr. Helen Tulk, suffered from the same rare condition. Davey Tulk recommended hot water bottles. The Lewisporte impostor had prescribed ice packs! In no time, Mom had a whole new lease on life, and in her later years, a new drug eased her situation even further.

Small wonder, then, that Mom named the next male member of the litter Davey Grenfell, the latter to honour Sir Wilfred Grenfell, the legendary English-born medical missionary to the Labrador and northern Newfoundland coasts. Ida Williams Simmons was a prolific reader, and this reflected in her choice of baby names. No Mary, Ann, Jim, or John for her. Almost all of my fourteen siblings were given less-common monikers. For example, my three surviving sisters were christened Primrose, Bonnette, and Cavell, evoking the memory of Edith Cavell, the British nurse executed by Germany during World War I.

The case of the living dead

My dad was the go-to coffin maker in Bishop’s Falls at a time when store-bought caskets were not an option for a couple of reasons—lack of availability and exorbitant cost. When the much-disliked George Cobb, the railway’s local head honcho, escaped the mortal coil, the whole town turned out to watch the funeral cortège go by, not to pay last respects, but to get a look at “the most expensive wooden overcoat ever seen in these parts,” as Dad put it.

My father’s coffin-making was his version of moonlighting, and a familiar ritual unfolded every time there was a new demand on his services: A knock on the door would announce the passing of a local resident and request that Billy Simmons, as he was known in the community, “make a box” for the newly departed. There was no time to lose. Tradition dictated that the body be waked in its bed the first two nights, placed in the coffin late on the third evening, and interred the next day.

Billy sprang into action. His regular job at the railway occupied him during the day, so he had just two or three evenings to complete the task. One of my most enduring memories is of my father bursting into the house late in the final evening and announcing, “She’s done!” That was his way of inviting us to his workshop, behind the house, to critique the finished product, an irregular hexagon covered in fabric, purple for the very old, grey for other adults, and white, pink, or pale blue for a child.

Dad, though largely introverted, could be a showman when circumstances warranted it. The family coffin inspection was such an occasion. My dad would, with a theatrical flourish, climb into the casket, adopt the pose of a laid-out corpse, and, addressing the soon-to-be occupant by name, would intone with mock solemnity, “Sam, boy, I sure hope you have a smooth ride over Jordan in this one!”

Carpentry and inspection ritual complete, one of the sons would be enlisted to “grab the end of the box,” and with Dad at the other end, they would carry the coffin to the home of the deceased, sometimes a mile or more away. Soon after, body and box got together for eternity.

Claude Andrews had died, we had been told, and it was my turn to grab one end of his newly finished coffin. Arriving at the Andrews home, Dad paused a moment near the still body and then joined the wake in the kitchen, leaving ten-year-old me sitting in the doorway of the master bedroom with a good view of the wakers just off to my left and of the comatose form directly in front of me.

Mr. Andrews sat up! He stared at me, clearly puzzled that I was there. After all, no one told him he had died! Claude, we soon learned, had “died” twice before. Each time, a deep coma had been mistaken for death. He lived another seven months before dying for good. Just to be sure, he was waked for five days before the burial—in, of course, a custom-tailored wooden overcoat stitched together by Billy Simmons.

Forty years later, while attending a Port aux Basques house party, I had launched into the above story which, on many previous recitals, unfailingly evoked an awkward, skeptical silence, if not outright dismissal. This time, as my hostess sensed where my story was leading, she interrupted me, summoning a guest in the adjoining room, and said, “Calvin, get in here. Roger is talking about your grandfather!”

Calvin Andrews, the local newspaper editor, had been getting the same less-than-convinced stares as I had whenever he tried to tell friends of his forebear’s miraculous return to life and of the ten-year-old boy who was there to witness it. At last, Calvin and I had found someone who had good reason to believe our tall tale. My good friend is himself very much alive these days as Pastor Calvin Andrews, retired General Superintendent of the Pentecostal Assemblies of Newfoundland and Labrador.

12 Twenty-first US president (1881–85)

13 Cavell has been named to Team Canada for the Australian Invictus Games in October 2018.

14 Of course, a comprehensive analysis of then-and-now family size would need to canvass the impact of other factors, such as economics, evolving values, and the advent of the pill.

15 Genesis 1:22, KJV

16 Newfoundland Dictionary of English, 2nd ed, 1999, University of Toronto Press

17 Large wooden barrel of varying capacity, but usually eighty gallons (304 litres)

18 The father of former prime minister Paul Martin served Canada with distinction as a Member of Parliament, cabinet minister, and High Commissioner to the UK.

19 i.e. short of stature, for those lacking a proper Newfoundland vocabulary