If you think education is expensive, try ignorance.

— Derek Bok, president of Harvard University, 1930–

St. John’s, July 1955. I was living the dream. I had conned my way into a cushy job at Fort Pepperrell37 Air Force Base. The US military installation was one of several in Newfoundland and Labrador, the result of the 1941 Lend-Lease deal between the Americans and the British. I arrived in St. John’s on my sixteenth birthday and, that afternoon, convinced the base’s hiring officer that I was eighteen and promptly landed a position as busboy in the officers’ mess.

Living quarters were my next preoccupation. An until-then futile search eventually took me to Brazil Square in the seedy part of town and to Chatfield House, a nondescript three-storey walk-up. I told the boarding mistress I wanted a private room. She smiled grimly and said, “Come with me.” After a hurried climb up two flights of steep, rickety, creaking, narrow stairs, we entered a room with four beds.

“Four guys in one room?” I muttered, incredulous.

“Eight,” she shot back. “Counting you, eight.”

The boarding house lady suggested adding a single cot. I agreed, having run out of options. Soon after, the empty spot in the fourth double bed was filled. For the next month, nine of us, I being by far the youngest, bunked in that room.

The $35-a-week paycheque was just a fraction of my Fort Pepperrell income. Senior, well-paid officers, enamoured by a gabby teen who loved to talk politics, ask questions, and tell stories, tipped me handsomely, sometimes as much as $150 a week.

The job was a blast. Regular hours. Lots of friendly people to talk to. And I was flush with cash, more money than I knew what to do with. So, I bought a car, used but nice-looking and reliable. The horn worked but was superfluous; the roar of the faulty muffler alerted the endangered. Too young to qualify for a driver’s licence, I had one of my suddenly large circle of friends do the driving.38 At sixteen, I had my own chauffeur! Clearly, I had arrived!

Plotting a new course

It was then, on a sunny July day, that I met a Salvation Army officer in downtown St. John’s, an encounter that dramatically changed my life. Major Charlie Woodland approached me or, more accurately, accosted me: “You’re Roger Simmons. I’ve heard all about you, how you got kicked out of school, how you’re throwing everything away.”

The Major invited me to his nearby home for lunch, and it was there I met his wife, Major Sarah Woodland, a beautiful, spirited woman who would be my mentor and friend until the day she died nearly fifty years later. Her husband pursued his mission: “My son, you gotta get back in school. The train leaves at five this evening. Be on it. Go to Windsor. There’s a welfare officer there, Julia Morgan. She used to be a teacher, a good one. She can help you play catch-up in grade ten math and English.”

As the well-meaning Major droned on, I mentally dismissed his every word: You idiot! Don’t you know how good I got it? A job, lots of money, a car. No parents around to hassle me. And besides, I plan to go to night school. Even if Major Woodland could have heard my thoughts, I doubt they would have swayed him. Indeed, the more I mulled over the specifics of his proposal, the less sure I was of my own argument. By five o’clock, I had quit my busboy job, picked up my paycheque, sold my beloved car, bid a hasty adieu to my palatial boarding house digs, and was sitting aboard the westbound passenger express, headed for home, for Windsor and for an entirely new twist in my already circuitous pilgrimage.

At nine the next morning, I found myself at the Windsor welfare office. As I approached reception, a voice off to my left pronounced, “You must be Roger Simmons. Come in.” Half-lenses perched on her nose, Dr. Morgan exuded a no-nonsense yet amiable aura. She drew my attention to eight scribblers39 on her desk, then pushed four of them, labelled Algebra, Geometry, English, French, toward me. “You’ll see I’ve put some assignments in them. Do what I wrote. Come back next Tuesday at two o’clock. I’ll take a look at what you did, and I’ll have another load of work for you in these.” She nodded toward the other four scribblers.

Dr. Morgan arranged for me to meet with the principal of the newly constructed all-grade Salvation Army School just up the street from her office. Captain Otto Tucker got quickly to the point: “I’ll take you into grade eleven—for a month. If you can handle it, you can stay.”

During the next eight weeks, I morphed into a hermit, leaving our house on Tuesdays only, hustling night and day to keep abreast of the merciless mounds of equations and theorems, essays and conjugations which Dr. Morgan kept dishing out, covering, she said, the entire grade ten course requirements in the four subjects. Fortunately, my early fascination for history and geography meant they wouldn’t trip me up in the year ahead.

Mentor par excellence

I enrolled in grade eleven. Daily, for the entire school year, I hitchhiked the ten miles from my Bishop’s Falls home to the school at Windsor. While there was a teaching staff of a dozen or more, large by rural Newfoundland standards at the time, the senior classes were sparsely populated. The previous school building had burned down, obliging the dispersal to other schools of secondary students, most of whom elected to remain there for their final year or two. There were so few students in grades nine to eleven that we were all corralled in one classroom. There were just two of us in grade eleven, Ray Brooks and me.

The good Captain was a teacher-principal. He ran the school and taught some of the courses. A brilliant communicator, he married a devastating sense of humour with a gentle humanity to motivate even the most apathetic scholar. Two or three weeks into the term, Tucker decreed that Ray and I would spend most of our school day in the unstaffed library. We were ecstatic because we had the place all to ourselves. Tucker told us he trusted our good sense to spend our time productively. The trust was misplaced. His grade eleven twosome quickly found creative, though not Board of Education–approved, pastimes, often smirking at the Captain’s presumed naivety and our ability to fool him. It didn’t take long, however, to realize the joke was on us. It dawned on us that we had two choices: fritter away the year or do whatever we could to graduate. We asked Tucker for specific assignments. He let go one of his trademark raucous laughs: “You boys are smarter than I figured. I was going to give you another week or two.”

There had been a method to his madness and an early glimpse into the creative mind of a top-notch educator who employed trust as a teaching tool. He recognized that leadership sometimes means simply getting out of the way, yet staying close enough to inspire, course-correct, and adjudicate. In dispatching us to the library, Tucker’s unspoken purpose was to get us to self-motivate and assume some responsibility for our education. It worked. For the balance of the school term, Captain Tucker functioned as the resource person to two inquiring minds, not a talking head who dispensed pearls of wisdom in fifty-minute monologues.

As the school year was winding down, the principal gave Ray and me info on the government’s student-teacher indenture program aimed at enticing high school graduates into a career in education. I was silently dismissive of the notion that I should become a lowly teacher. I had a grander scheme in mind.

It didn’t take long to figure out that the realization of my dream would come with a hefty price tag. I soon concluded that my only ticket to university was the indenture program. There was no choice but to fill in the application and drop it in the mail. Though the paperwork for enrolment at Memorial University was in place, there remained one big obstacle: money. The bursary would cover my tuition, but there would also be textbooks and living expenses.

Chasing the almighty buck

Soon after writing the final school exams, off to Ontario I went to seek my fortune, as untold thousands of Newfoundland guys and gals had done before me. My travel companion, John Pelley, had relatives in Oshawa, so we made a beeline for Canada’s auto manufacturing nerve centre. Within hours of stepping off the train, I joined Oshawa’s workforce, first as a carpenter’s helper, and three days later as a confidential clerk in General Motors’ truck plant.

The latter job was a boondoggle, at least, for me. The job title messaged my assignment as an indispensible insider, the custodian of the closely guarded paint codes which, it was asserted, gave GM an edge on the competition. Whenever assembly line workers needed paint, they came to me, holed up alone among endless shelves of oversized paint cans. Hours, sometimes days, would pass without a single customer, facilitating marathon literary pursuits and, on occasion, a welcome nap. Alas, my utopia was short-lived. The plant routinely shut down in August for staff holidays, which didn’t include me, a short-term, non-unionized worker.

With family and friends in Toronto, I decided to try my luck there and became a mailroom clerk at Colgate Palmolive. My routine included twice-daily tours of the building’s six storeys, delivering mail and emptying “out” baskets. The manufacturing floors I dreaded. Gagging lye fumes hung heavily in the air. I became adept at exiting the stairwell at a sprinter’s pace, delivering the goods, snatching the outgoing mail, and disappearing into the stairs, all the while holding my breath.

Company policy allowed us a free hand in soaps and toothpaste. We regularly subsidized, ever so slightly, our meagre paycheques by swapping our freebees for chewing gum with Wrigley’s workers across the street.

Early September 1956, my best buddy since childhood, Ivan Seaward, and I took the train east to North Sydney, Nova Scotia, then the ferry to Port aux Basques and the legendary “Bullet” train to Bishop’s Falls. A few days later, we were off to St. John’s and university.

First-year college was a coming-out for me. I was soon knee deep in campus politics, a stringer for the student newspaper, a gofer member of the debating society, and an officer-cadet in the Canadian Officer Training Corps (COTC), an army reserve unit.

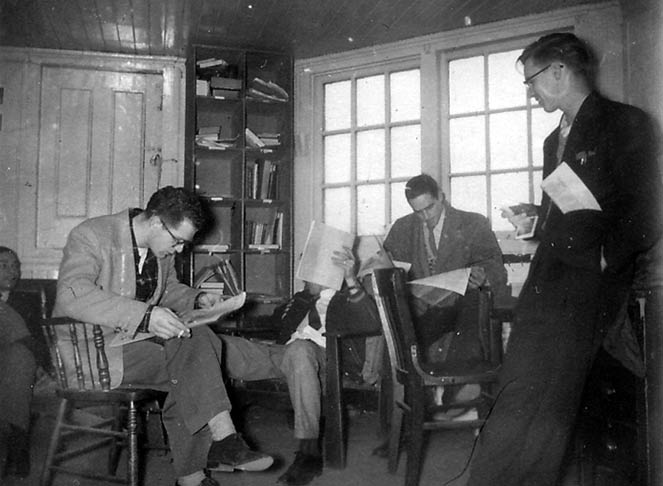

St. John’s, 1956. The Muse (student newspaper) office, Memorial University. L-R: Garf Fizzard, Harry Stamp, Dave White, Dave Pike, and me. (Author photo)

Boot camp

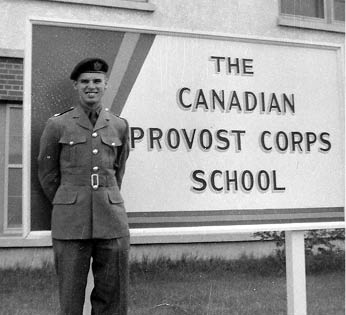

As a COTC cadet, I participated in a mid-week drill and a rifle practice on Saturday. I was assigned to the provost corps and spent the summer of 1957 at Camp Shilo, near Brandon, Manitoba. Sweltering temperatures and the endless sand justified the base’s nickname, Little Sahara. During a field exercise, cocooned in full battledress, I succumbed to the heat and was carted off to the hospital.

The cadets were a motley host and hailed from pretty well every province and territory: three Newfs, my buddy Ivan, Ralph Dale, later a member of my teaching staff, and me. Feldman, an insufferable elitist from Quebec. David Searle, a pleasant fellow from Northwest Territories, now a retired lawyer, having been Speaker of the NWT legislature and a UBC professor. Our drill sergeant, surnamed May, nicknamed Maysie, did justice to the stereotype. Brutal, loud, abusive, vulgar, merciless. I’ve met a few obnoxious types but none who took such pleasure from being mean and nasty.

Shilo, MB, 1957. Officer Cadet Roger Simmons, COTC. (Author photo)

Weekends, I played tenor trombone in the Brandon Salvation Army Band. I was often seconded to another, the Ellice Avenue Band in Winnipeg. With that group, I toured around Manitoba on weekends, doing concerts in Riding Mountain National Park, the International Peace Garden at the US border, and other venues.

I had signed up for a parachute course at the end of the summer camp, but it got cancelled. My early departure meant that I had to forgo a much-anticipated outing. The new prime minister, John Diefenbaker, was coming to town for a fishing trip with the local MP and cabinet minister, Walt Dinsdale, who had invited me to join them. Dinsdale was my bandmaster at Brandon Citadel.

A few months earlier, I had seen the mercurial Diefenbaker at an election rally in St. John’s. At the old CLB40 Armoury, the Conservative leader wowed an overflow crowd as he invoked the name of a Liberal warhorse:

“Jack Pickersgill41 says he has a sixth sense, the political sense. Ladies and gentlemen, what a fine man he’d be if he had the other five senses!”

I never did get to meet Diefenbaker. He was still an MP when he passed away in August 1979, three months before my election to the House of Commons.

Cash flow

Personal financial realities made my first university stint a short one. With just a year under my belt, I had to forsake the joys of college life and find a source of income, becoming a teacher in a remote outport. Over the next five years, I alternated between teaching and studying, completing the second-year university requirements in summer sessions, and graduating from the Salvation Army College for Officers.

My return to Memorial full-time was by a roundabout route. Although accepted for the 1962–63 academic year, an unexpected family circumstance gutted my savings and necessitated a hasty change of plans. I found myself in Wabush, then an embryonic mining town in western Labrador, as a junior high school teacher. The principal was my long-time friend, Dom Howse, a gentle soul and highly competent administrator. Two weeks into the school term, a doctor diagnosed a condition which threatened to get more complicated, and he advised me to immediately relocate closer to adequate medical facilities, there being no hospital in Labrador West at the time.

Back in St. John’s, it was time to reactivate Plan A, if possible. With the fall semester already started, was I too late to enrol? I called on the university registrar. H. T. Renouf found a way. I was basically back to square one. However, the reason I had wound up in Wabush rather than in a college lecture theatre was still very much in play. I needed money, and fast.

My one Wabush paycheque gave me a little working capital, which I promptly invested. A classified ad in a St. John’s daily announced my availability as a tutor in high school French and math. Responses to the ad flooded in. Almost overnight, I had more students than I could handle alone. I had tapped into a niche market where there was real demand, and not just in my advertised specialties. How about English, the callers asked, or Latin, or history?

I responded by incorporating, well, just about. The St. John’s Tutorial Service was born, sizable print ads proclaimed tutors available in all subjects, and, to respond to the ever-increasing demand, I contracted twenty-five fellow Faculty of Education students, all experienced teachers upgrading their qualifications. I hired a secretary to track the tutoring requests and assignments, bill clients, and pay tutors.

Expanding my portfolio

My French tutoring spawned two other lucrative spinoffs. The Department of National Defence (DND) signed me up to conduct oral French classes for its officer personnel at Fort Pepperrell.

My high school tutoring ritual included leaving with the student a one-page summary of the concepts covered during a session. These notes came to the attention of several teachers, who requested copies. And that’s how I stumbled onto the idea of formalizing, expanding, and publishing the notes. All About (French) Verbs was the result. To ensure a quality product and to give some legitimacy to my presumptuous undertaking, I sought out the reigning expert on the teaching of high school French, school principal Clifford Andrews. He generously agreed to edit the work and provide a preface, and he became an indispensable mentor and cherished friend. For more than half a century until his 2013 death, I never ventured anywhere near St. John’s without seeing Cliff and his bride, Joan. We enjoyed great get-togethers puzzling over the present, crystal-balling the future, and telling lies about the past.

All About Verbs shortly became an ancillary text for the teaching of high school French and received the provincial Department of Education’s approval as such. Demand for the slim volume was brisk, with considerable impact on my bottom line.

Soon, I was gearing up for another publishing endeavour. The province’s school boards, numbering nearly 300 at the time, depended largely on St. John’s and Corner Brook42 dailies to advertise available teaching vacancies. This left the more remote boards and would-be applicants at a disadvantage. The choice jobs were snapped up by those who first got their hands on the newspapers, namely teachers in urban areas. An up-to-the-minute listing of available teaching and administrative openings, regularly available to all the province’s educators, would help mitigate the problem. Voila! Educators’ Gazette was hatched! The publisher? You guessed it: me. The new service was an immediate hit and continued biweekly publication for eight years, until the consolidation of school boards to fewer than twenty rendered the Gazette a much less viable enterprise.

By early 1963, I had two popular publications, a tutorial business that was humming nicely along, a small DND teaching contract, several tutorial students, and twenty-seven part-time employees, including a staffer to handle the minutiae generated by the Gazette. And, oh yes, I was also a full-time university student.

Throughout the next two and a half years, the hectic pace of my sundry pursuits continued. Multi-tasking was the watchword; a growing bank balance, the social life of a Buddhist monk, and sleep deprivation, the consequences. My faculty advisor in my senior years43 was Dr. Phil Warren, later minister of Education in a Wells44 cabinet. As I awaited Dr. Warren’s arrival, his office partner, Dr. Ray Barrett, spoke up.

“We’ve been talking about you. If you didn’t have so many irons in the fire, you could graduate with a first-class degree.”

Dr. Barrett recalled many years later that my reply at the time was, “Who wants a first-class degree when I can have all the fun I’m having and get a second-class degree?”

The two profs had read my situation perfectly. Less-than-optimal time management, coupled with a little old-fashioned greed and overreaching, had me juggling university obligations with more tutoring assignments than I should have accepted.

Speaking for the affirmative

Those latter three years at Memorial weren’t all business and study. I chaired the Students’ Representatives Council and headed the campus branch of the Newfoundland Teachers’ Association. I was increasingly active in the debating society. Fellow Lewisporte native Gordon Moyles and I were the university champions.

A debating partner and I got to represent our alma mater at inter-varsity debating events in other provinces, with mixed results. Our low point was at St. Dunstan’s, now UPEI, in Charlottetown. Two of the judges, one of the opposing debaters and the chairman, were all surnamed McDonald. Unaware of the proliferation of the McDonald clan in PEI, we were sure the cards had been stacked heavily against us. Our suspicions robbed us of our usual aplomb, focus, and good humour. A distracted, lacklustre performance cost us the debate. It was a self-inflicted wound—and a valuable lesson. Do not distress yourself with dark imaginings.45

The Methodist College Literary Institute (MCLI) had been a catalyst and venue for debating showdowns in St. John’s since 1866. It was my privilege only once to debate under its auspices and on its historic turf. My team was challenged to a debate on public education versus church-operated schools. The challengers were the legendary Albert Perlin, editor of the St. John’s Daily News and a journalistic icon, and Memorial’s president, Dr. Raymond Gushue. My debating partner and I acquitted ourselves well and were declared the winners.

Notwithstanding my many extracurricular preoccupations and the need to maintain focus as a student with graduation aspirations, my involvement in student activities earned me the President’s Gold Merit Award, for outstanding contribution to student affairs. I could never quite decide whether I was deserving of the commendation or if Dr. Gushue was affirming he bore no grudge for the MCLI debate outcome.

My tutoring enterprise had quickly become a thriving business that continued to prosper, until I folded it two years later to accept a rural school principalship. Career-wise, that was a defining move, away from education as a business to educational administration. It was also a lifestyle change, a conscious values decision to trade my rapidly improving financial circumstances for a less opulent but, hopefully, more satisfying challenge in an arena I knew and loved, rural Newfoundland and, specifically, Springdale, a coastal community of 2,000 population, where I had earlier spent two rewarding years as a clergy-teacher-principal.

America beckons

In the days when Newfoundland was still independent, several American universities enrolled a sizable number of graduate students from the Rock. Even after we cast our lot with Canada, the practice continued. In May 1964, just days after my first Memorial University convocation, I joined the pilgrimage to American academe. My objective was a master’s degree in educational administration. This time, money, that is to say, the lack of it, was not an obstacle. My myriad business ventures of the previous two years had secured a sound financial footing for me.

Which is undoubtedly why I was able to quickly immerse myself into the course of study at Boston University (BU). Without the time demands of my many extracurricular schemes, the master’s program had my undivided attention. Well, almost. One diversion was hard to resist. The storied Fenway Park and the fabled Red Sox were just a stone’s throw away across Commonwealth Avenue, and many an exciting afternoon I spent there.

I got my undergraduate degrees at Memorial. I got an education at BU. That’s not an aspersion against Memorial, rather a comment on my mindset, increased maturity, and focus by the time I arrived at BU. The much smaller graduate classes also helped, as did their composition. My fellow Newfoundlander and good friend Ern Cluett and I were usually the youngest students in the room and, unlike most of the rest, without any administrative track record. Many of the others were seasoned educational managers at mid-career. The pressure was on Ern and me to measure up. Anonymity also played a role. Without the baggage of prior association, we were seen for who we were, just two more students determined to complete the program.

The presence of Ern and, surprisingly, three dozen other Newfoundlanders, made the adjustment to a foreign campus quite manageable and, indeed, enjoyable. Eric Abbott, who would later become a valued member of my teaching staff, was completing his doctorate, as were Salvation Army officers Wil and Val England. A future Newfoundland minister of Education, Wallace House, and dozens of other school administrators from the Rock, were also there.

Comfort food

The rooftop of the Englands’ accommodations was a welcome spot to cope with Boston heat and humidity and, especially, to gorge on Newfoundland cuisine.

Speaking of comfort food, Nestle’s Pure Thick (canned) Cream was always a popular condiment among BU’s Newfie mafia. On my second trip to Boston, the car trunk contained two cases of Nestle’s. The US agent at the Calais, Maine, border crossing didn’t buy my story, suspecting the cans concealed something far less innocent, maybe diamonds or drugs. With his bayonet, he pried open one can, then another, but found nothing to confirm his suspicions. As he stood there looking ridiculous, his hands dripping my precious cream, I tried a little humour: “If I were you, I’d lick ’em!”

He was not amused. His sticky right hand fled to his gun holster; he glared at me and walked away. All but two of the ninety-six cans of cream made it to the appreciative palates of Newfoundlanders in exile. Had the border agent taken my advice and licked his fingers, I might’ve had to surrender the whole stash!

Over the years, I have made literally hundreds of trips to the US, regularly interfacing with law enforcement personnel at border crossings, airports, and highway checkpoints. I’m sure that, in their off-duty hours, they’re no different than the overwhelming majority of Americans whom I know—personable, generous, and inclusive. But here’s the rub: When those same people don a uniform, wear a badge, or tote a gun, too many of them become stark raving maniacs, confrontational, humourless, and stone deaf. In a nod to Clint Eastwood, I call such types the Make my day posse. Rodney King46 would have known exactly what I mean, as would Katie McCrary, the homeless woman in Decator, GA, beaten by police in July 2017 for begging in public.

37 Sir William Pepperrell was an Anglo-American soldier who led American colonists in the capture of the fortress of Louisbourg, Nova Scotia, from the French in 1745.

38 Most of the time, it was my late friend, Harry White, a fellow bandsman at the Salvation Army’s Duckworth Street Corps, who later distinguished himself as bandmaster of Army bands in the Toronto area.

39 Newfanese for exercise books

40 Established in Newfoundland in 1892, the Church Lads’ Brigade is an Anglican youth organization.

41 Newfoundland’s representative in the federal cabinet

42 A city on Newfoundland’s west coast

43 I graduated at Memorial University in 1964 with a Bachelor of Arts (education) and in 1965 with a B.A. (French).

44 Clyde Wells was premier of Newfoundland from 1989 to 1996.

45 “Desiderata,” a 1927 prose poem by American writer Max Ehrmann, 1872-–1945

46 African-American construction worker beaten by Los Angeles police officers in 1991