The hottest place in Hell is reserved for those who

remain neutral in times of great moral conflict.

— Martin Luther King, Jr.

I first laid eyes on the whirling dervish known as Joey when I was nine years old. I can see him now, just down the street from my house, as he jack-in-the-boxed out of his nondescript car, microphone at the ready, turned up the volume on his screech box, and proceeded to mesmerize the growing crowd.

The historic referendum campaign was in full swing. The upcoming vote would determine Newfoundland’s constitutional destiny, deciding among three options: a return to responsible government, which had been suspended for financial reasons fourteen years earlier; confederation with Canada; status quo, a British-dominated Commission of Government, a bureaucratic and benevolent autocracy,87 which had been in office since 1934, characterized by Don Jamieson as the long night of political abnegation88.

Joey Smallwood was championing the confederation cause. He regaled all who would listen about the utopia that was just around the corner, provided, of course, they voted to turn their backs on Newfoundland’s proud independence and cast their lot with Canada. In Bishop’s Falls, he was largely preaching to the choir. Like most rural communities, the town liked what he was selling.

Many believed Newfoundland should return to self-government before deciding on its constitutional future. John Crosbie’s 1946 poem, penned during college days, leaves no doubt he shared that view:

Up true Newfoundlander! Rise!

And fight once more to win proud freedom’s prize.89

It would actually take two referenda to decide the issue. The third-place finisher in the first vote, Commission of Government, was dropped from the ballot, and Confederation with Canada won by a nose90. The lost Dominion91 became Canada’s tenth province.

The first time I got to talk to Smallwood came seven years later when I was a vagabond, not quite sixteen years old. He and I were cooling our heels in the old Gander airport terminal because a fog blanket had cancelled our respective flights. As I sat alone playing solitaire, I heard a familiar voice.

“Greg, here’s a young man going places.”

I recognized the two suits hovering over me. Finance Minister Greg Power had been Joey’s right-hand man in the battle for Confederation. Standing next to him was, you guessed it, Premier Smallwood himself. And he was talking to me!

“Are you travelling alone? Where to?”

Smallwood and his minister were probably headed off to some distant land to coax deep pockets to invest their millions in Newfoundland’s bright future. I was destined for Halifax. I had decided I wanted to travel by plane for the first time, and the Nova Scotia city was the only out-of-province place to which I could afford to fly.

I never did board that flight to Halifax, but I came within a whisker of a quick trip to Europe. By the time the fog lifted, I had passed two nights curled up on an airport sofa without much sleep. In my delirium, I responded to the wrong boarding announcement. Believing I had heard TCA, I found myself sitting aboard a TWA92 flight bound for Düsseldorf, Germany. The bane of security screening was far into the future.

Alas, it was not to be. The stewardess’s93 head count did me in. Back in the terminal, and now wide awake, I had to choose between globe-trotting and fending off starvation, having run out of money. I cashed the air ticket and made a beeline for the cafeteria, then the train station. I would not slip the surly bonds of earth94 for another two years. However, I did get to meet my political idol. A few years ahead, he would become less so.

A doting Premier

There’s a great story of how Joey got a glimpse of one of his idols. The Liberal road show had rolled into Corner Brook. As the platform party, including prominent developer Art Lundrigan, assembled in the holding room, Joey launched into yet another of his monologues, normally long and painfully repetitious.

This anecdote, though, is worth retelling—without the repetition. Smallwood and Lundrigan had played tourists in Rome. Just when the tour of the Basilica of San Clemente, a twelfth-century Christian edifice, appeared to be ending, the guide led them downstairs to a second church that had been converted from the home of a Roman nobleman in the fourth century and used by both early, secret Christians and pagans. Soon thereafter, the duo once again followed the guide below and came upon the ruins of a third structure, a villa and warehouse destroyed in the Great Fire of 64 AD. Smallwood recognized the lady standing in front of him and couldn’t contain his good fortune. In a loud whisper, he exuded to Lundrigan: “Jackie! Jackie Kennedy! It’s Jackie Kennedy!”

The manner in which he reacted to this chance sighting of an American icon and global phenomenon was revealing, significant in a way that Joey probably didn’t realize. When the premier told us the story, he had to be reminded by Lundrigan to mention the name of the man standing beside Jackie—Aristotle Onassis! The Greek magnate’s megabucks were no match for her beauty and celebrity. It was arguably the one time in Smallwood’s political career when a gorgeous woman blinded him to his first love, a big-time tycoon rolling in dough and looking for a place to invest it.

My way or the highway

Ted Russell and I shared an office for two years at Memorial University in the 1960s. We were teaching speech to first-year students, though both of us had a complete disdain for the underlying premise of the course, namely that the incoming students needed to learn proper English and abandon their lilting Newfoundland dialects, the equivalent of decreeing that all Irishmen must speak the Queen’s English or telling US southerners that their drawl is inferior to the lingo of New Yorkers.

Russell and I were mercenaries. While we didn’t believe in the course, we needed the money, which, in Ted’s case, might strike you as strange. He was, after all, an acclaimed writer and a pioneer in heightening an awareness of Newfoundland’s distinct culture and society. But he was also persona non grata, at least insofar as Premier Joey Smallwood was concerned.

Beginning as a sixteen-year-old schoolmaster at Pass Island95 in the 1920s, Russell had been, successively, a teacher, magistrate, rural development specialist, and a cabinet minister in Joey’s first administration. His sojourn in the corridors of power was short-lived. Following a series of disagreements over the premier’s dictatorial approach to governance and policy-making, Russell threw in the towel, the first of Joey’s ministers to quit. For that, he would pay a heavy price.

Joseph R. Smallwood’s middle name should have been revenge. In his treatment of Russell and the few others who had the audacity to challenge him, the premier gave new, tawdry meaning to the word vindictive. He went to great lengths to ensure that Russell didn’t earn a living, threatening to disown anybody who hired Ted. Which explains why the literary icon brought home the bacon by teaching at Memorial and scriptwriting for the Canadian Broadcasting Corporation, just about the only two institutions that Joey couldn’t intimidate.

As an orator, Smallwood had few peers. To make certain his message got through, he used a triad progression.

“First, I tell my listeners what I’m going to tell them. Then, I tell them. And finally, I tell them what I just told them.”

His repetitive formula was as predictable as the opening bars of the Last Post on Remembrance Day, like a bugler who strikes the first note of a triad, then one after the other, the two higher notes. Even if one of the notes is slightly off-key, the listener will have heard all three. While there could be no doubt that his message was received, Joey’s repetitive speaking style could sometimes induce an effect that was far less tuneful than any trumpet or piano.

Although his oratory and histrionics wowed the masses, the substance of his message, his single-minded fixation on economic development, no matter the financial and human cost, gave many the jitters. As noted, Ted Russell left the Smallwood cabinet because of policy differences. Four years later, a second minister, Dr. Herbert Pottle, resigned for similar reasons. His book, Newfoundland: Dawn Without Light, is a cover-to-cover condemnation of Joey’s approach to industrial development and job creation. The ex-minister’s most scathing indictment is that Smallwood neglected the province’s most precious resource, its people. Pottle charges that the premier squandered the opportunity to make his fellow citizens self-reliant and trained them to be wards of the state because it suited the political agenda. Far from being partners in government, the rank and file became its pawns. In Pottle’s telling phrase, they were the counters on the shuffle-board of economic development.96

“Ill fares the land, to hastening ills a prey,

Where wealth accumulates, and men decay.”97

The anointed one

In 1964, a paper I had written as part of my university studies came to the premier’s attention. The treatise lauded advances in Newfoundland education since Confederation. Smallwood summoned me to his office and proposed my paper be expanded and published. A couple of cabinet ministers were tasked to make it happen. But the project never got off the ground—mainly, I suspected, because one of them had plans to publish a book on the same subject, which he subsequently did.

In the fall of 1965, Smallwood staged a so-called thinkers’ conference that showcased several prominent speakers, including economist John Kenneth Galbraith and political firebrand René Lévesque98. I participated in a panel with the Canadian-born Galbraith on the role of government in a dynamic society.

The premier once again invited me to his office in early 1966 and regaled me with his vision of a glowing future in politics for me on the premise, of course, that I join his slate of candidates in the pending general election.

“Only four men are capable of taking the reins when I step down.”

He then named the first three, listing their strengths but then eliminating each as he cited their weaknesses.

“And fourth, there’s you!”

In his generous assessment, I was unquestionably God’s gift to mankind and the only worthy successor to him. It was all very seductive, almost convincing for a twenty-seven-year-old political neophyte, until I learned that the exact same template had been used in pitching several other individuals. In each scenario, the person being courted was the only logical choice as Joey’s successor.

One-party state

Ever since the 1949 union of Newfoundland and Canada, the province had been Smallwood’s personal fiefdom. All decisions relating to budgetary, economic, and social policy were made by him. The choice of Liberal candidates, both provincial and federal, was controlled by Smallwood. The House of Assembly was reduced to an echo chamber for the verbose premier. On many of the major public policy decisions, the legislature didn’t even get to rubber-stamp them, as Joey routinely ignored both precedent and legality to impose his vision and ingratiate himself with voters.

In 1966, Smallwood called an election, the sixth provincial campaign since Confederation. For the electorate, it would be the fifteenth trip to the polls in eighteen years, including the two referenda and seven federal elections. For Smallwood, it would be yet another opportunity to tighten his stranglehold on power. Indeed, he seemed to be seized with the notion of wiping out the parliamentary opposition altogether. To that end, he rolled out a pie-in-the-sky platform, sweeping, audacious, and costly. And he recruited several star candidates, among them John Crosbie and Clyde Wells.

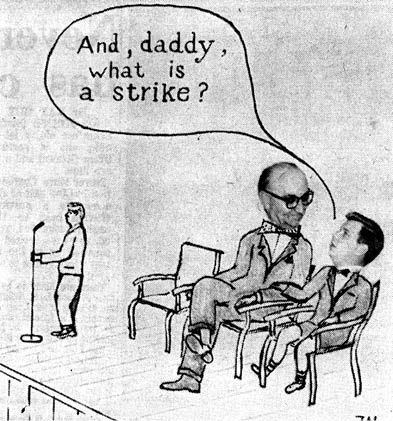

Corner Brook, NL, 1966. Western Star cartoon: Clyde Wells became Premier Smallwood’s Labour minister during a nurses’ strike. (Francis Hull cartoon)

During the campaign, I was interim editor of Corner Brook’s daily newspaper, the Western Star. The actual date of the election posed a problem for me. With the new school year getting under way, I needed to be at my desk in Springdale, more than 100 miles away, to resume my responsibilities as supervising principal. First, though, I had to discharge one final duty for the newspaper, write an editorial commenting on the election results. Except the outcome wouldn’t be known until long after I had hit the road. On the completely safe presumption that Smallwood and the Liberals would once again rack up an overwhelming majority, I penned a piece decrying the small size of the opposition and its implications for democratic governance.

The task accomplished, I made a dash for the parking lot. By the time I reached my car, I had a nagging thought: What if my assumption concerning the election is wrong? To cover another possibility, I ran back upstairs and banged out a second editorial on the Smith Corona, this time lamenting there would be no opposition in the legislature, that the Tories had been wiped out. As things turned out, it was my first editorial that ran in the paper next morning. Joey won all but three seats, shrinking the Tory rump from its previous seven. The Liberal popular vote was sixty-two per cent, within four points of its support in the first post-Confederation election seventeen years earlier. Clearly, Smallwood was still the master of his fate.

Black Duck Siding, NL, 1966. As editor of the Western Star, Corner Brook’s daily newspaper, I interviewed salmon fishermen on Harry’s River. (Western Star photo)

There are none so blind as those who will not see99

By the late 1960s, Joey had reigned as a benevolent dictator for two decades. That was about to change. The 1969 provincial Liberal convention, called by Joey to mute the growing clamour for a less autocratic regime, marked the beginning of the end for Smallwood, though few realized it at the time. If Joey himself saw it coming, which I doubt, his staggering capacity for self-delusion would have shielded him from the truth.

There were some signs. Joey’s attempt in the fall of 1968 to stack the party’s executive with his sycophants backfired. His hand-picks for president and vice-president were defeated by two young upstarts, Rick Cashin and me. We were a whole lot happier than Joey was! At the reception which followed, Joey pumped the hands of the party’s newly elected executive members. Despite their many differences, the new president and the premier had a grudging respect for each other going back to Cashin’s days as an MP100 and beyond. So, it wasn’t surprising to see them chatting up a storm just minutes after the young fox had outfoxed the old fox.

What happened next did surprise onlookers, though not me as I stood beside Cashin. Smallwood’s handler said, “Premier, you know Mr. Simmons, I believe?”

Joey fixed a frigid stare over my shoulder, ignored my extended hand, and, without uttering a word, moved on to deliver an affectionate bear hug to one of his acolytes who had survived the election of party officers.

Smallwood had reason to pretend I didn’t exist. During the 1966 election, I had published in the Western Star a couple of impish cartoons and penned several editorials that cut close to the bone. In reference to an ongoing nurses’ wage dispute, I ran the first political cartoon featuring Clyde Wells101—depicting Joey’s new Labour minister dressed in short pants, legs dangling above the floor, beseechingly looking up at the premier seated beside him: “And, daddy, what’s a strike?”

A second cartoon was more biting. The island portion of the Trans-Canada Highway had been completed to great fanfare in 1965, facilitated largely by federal dollars and, specifically, by Prime Minister Lester Pearson. As construction proceeded, the 600-mile stretch of road from St. John’s to Port aux Basques was peppered with signs which read, “We’ll finish the drive in ’65, thanks to Mr. Pearson!”

Paving of the final sections had been a bit of a rush job, and within months there were problems with potholes and undulating blacktop. The cartoon sketch captures driver frustration. A motorist fixes a flat tire. A nearby highway sign reads, “We’ll patch and fix in ’66, thanks to Mr. Smallwood!”

One Star editorial in particular hit a nerve. Entitled The one-party state, it likened Newfoundland to the USSR in its governing practices. My opinion piece was such a frontal attack on the government that I cleared it with the publisher, Wallace McKay, who predicted that the editorial would cause some waves. Sure enough, the newspaper had barely hit the streets when I got a call from a senior staffer in the premier’s office. I don’t recall what he said to me, but his words certainly had the intended effect. I raced into McKay’s office and blurted out, “Ed Roberts just called me.” My panicky tone of voice and matching body language communicated the real message. McKay, ex-military, went ballistic.

“I knew it was a mistake to bring you aboard. Whimpering nervous Nellies I don’t need. If you’re not up to the job, clean out your desk and make yourself scarce.”

McKay’s contrived tantrum saved the day. As I continued to write provocative editorials, tirades from the premier’s office no longer triggered the urge to seek cover from the publisher.

The relationship between the premier and me, his newly minted vice-president, would get worse. At the national level, Prime Minister Lester Pearson had spearheaded dramatic and enduring changes in social policy during his five years in the top job. Having twice failed to win a majority government, he decided to step down, setting in motion a leadership process to choose his successor.

Don Jamieson, Newfoundland’s member in the Pearson cabinet, suggested I get myself elected as a delegate to the 1968 federal Liberal leadership convention. I made my intention known to two key Liberals in Springdale and was assured of their support. Joey had other ideas. At the delegate selection meeting, as soon as I was nominated, the two guys, whose blessing I thought I had, ganged up on me, one of them nominating the other, who bested me by three votes to win the sole delegate position, but not before the meeting’s chairman had extolled the virtues of my opponent. The chairman was a known Smallwood henchman brought in from a nearby town, and in a delicious tidbit of finessing, he was my cousin, Wes Simms.

However, all was not lost. Jamieson, no fan of Smallwood, arranged for me to attend the convention as an observer. As I entered the Ottawa convention venue, I came face to face with Smallwood and two other Newfoundland politicians, one of whom was and is a close friend. Fred Rowe, Jr. later told me of the premier’s verbal outburst when he spotted me: “Who let that little pipsqueak in here!” A few months later, commiserating with other party members about Joey’s stubborn refusal to pass the torch to the next generation, I elevated foot-in-mouth disease to new heights by declaring: “What this party needs is a good state funeral!”

In no time flat, my reckless utterance reached Smallwood’s ears with predictable consequences. My status as persona non grata was confirmed and cemented. Meanwhile, the federal leadership convention chose Pearson’s successor on the fourth ballot. The new Liberal leader and prime minister, Pierre Trudeau, was a first-term MP from Montreal and had served as Justice minister under his predecessor. He had come to national prominence for his role in constitutional negotiations and his groundbreaking initiatives in justice reform. Two months into office, the new prime minister went to the polls.

If the mini-revolt which Cashin and I staged, with a lot of help from our friends, was an omen of Smallwood’s loosening grip on power, the results of the 1968 federal election were a full-blown mutiny. Lifelong Liberals by the thousands bolted and cast their votes for change. Even many a Joey disciple swallowed hard and marked an X for the “dirty Tories,” a term much-used by Smallwood to imply cause-and-effect between the party that formed the Newfoundland government in 1932 and the “dirty ’30s.”

Trudeaumania swept the nation, racking up 155 seats in the 264-member Commons. Yet, despite Smallwood’s choreographed switch to Trudeau as the federal leadership convention got under way two months earlier, all but one of Newfoundland’s seven ridings elected Tory MPs. “While the rest of Canada was revelling in Trudeaumania, we were swept up in Smallwoodphobia.”102

Why me, Lord?103

John Crosbie and Joey Smallwood had a tempestuous relationship that can best be described as love-hate, not alternating but sequential. Things got off to a promising start when the thirty-five-year-old deputy mayor of St. John’s and established lawyer joined Smallwood’s cabinet in the lead-up to the 1966 provincial election. Even then, though, Crosbie must have cross-examined himself in the mirror the very next morning:

“What, in the name of the good Lord, have you done?”

Done, it was. And whatever misgivings the new minister may have had, campaign imperatives kept his lip buttoned, publicly, at least, until the polls closed. Almost immediately thereafter, the Smallwood-Crosbie marriage began to show ominous strains. The premier’s dictatorial ways and, just as significant, his seat-of-the-pants approach to public policy and drooling fascination with industry tycoons were more than the egalitarian, rational, business-savvy Crosbie could stomach.

The Come By Chance boondoggle brought matters to a head. The breaking point for Crosbie, and for Clyde Wells, was interim financing for the proposed Come By Chance oil refinery. The premier had agreed to advance $10 million to start the project, even though developer John Shaheen had no equity in the venture. Both Crosbie and Wells quit the cabinet. That’s their version. Smallwood insisted they had been given the boot.

I believed John and Clyde. I was not alone. Much of the public, but especially the pundits and insiders, had their fill of the premier’s revisionist editing of the facts and his petulance.

Wells quit politics altogether, though that wouldn’t be the last we saw of him. Crosbie eventually joined the microscopic Tory caucus, but not before challenging Smallwood in a riveting tug-of-war, the 1969 Liberal leadership race.

A leg-up for Peckford

Delegations were being chosen across the province for the upcoming leadership convention. Smallwood, Crosbie, and Alec Hickman were the main leadership contenders. I was a Hickman supporter. Each candidate’s partisans were running slates, and as the delegate selection meeting in Green Bay district proceeded, it became obvious that Smallwood’s list would take every position. That’s when I withdrew the Hickman nominee for secretary and asked my group to vote for Brian Peckford, a Crosbie supporter. The final delegate count was Smallwood 15, Crosbie 1.

In enabling Peckford’s win, I played a small yet key role in Peckford’s path to the premiership. My friend was elected and soon came to Crosbie’s attention, who, realizing Brian’s smarts and people skills, recruited him as a full-time organizer. Three years later, Peckford was elected to the House of Assembly and would later succeed to the top job.

Crosbie comes courting

Meanwhile, Crosbie was slogging away. I flew with him in his chartered aircraft to Goose Bay, mostly to salvage some credibility as party VP after having traipsed around the province as part of a tag-team act with Smallwood and Cashin.

It was Crosbie’s decision to pitch his rented helicopter on my front lawn in Springdale that made me smile and perhaps helped to burnish my image among the locals. The mountain had come to Muhammad. I had begged off on earlier entreaties to have a chat with him. Crosbie showed me the results of a poll, one of a series he had commissioned to arm him with up-to-date information on issues and on people who could impact his leadership bid.

The findings of one question in particular had me thinking vain thoughts. Having just been head of the province-wide teachers’ organization and now as vice-president of the Liberal Party, I had achieved a high profile, which wasn’t that difficult given the times and Newfoundland’s small population. TV viewers, in the pre-cable era, had a choice of just two channels. The odds were good that most viewers were exposed daily to one or both of the news telecasts.

Here is the relevant excerpt from the Crosbie poll.

Voter job ratings of the 10 best-known leaders

in politics, the public service and academe

July 1969 (excerpt)

|

% positive job rating |

Ranking |

|

|

Dr. Phil Warren, Professor, Memorial University* |

79 | 1 |

|

Alec Hickman, provincial Minister of Justice and Health |

72 | 2 |

|

Donald Jamieson, federal Minister of Transport |

71 | 3 |

|

Roger Simmons, President, Newfoundland Teachers’ Association |

70 | 4 |

|

James McGrath, Member of Parliament |

66 | 5 |

|

Frank Moores, President, Progressive Conservative Party of Canada |

64 | 6 |

|

John Crosbie, Member, Newfoundland House of Assembly |

58 | 8 |

|

Joseph Smallwood, Premier of Newfoundland |

56 | 12 |

|

Clyde Wells, Member, Newfoundland House of Assembly |

53 | 15 |

|

Pierre Trudeau, Prime Minister of Canada |

36 | 22 |

|

* Position/title at the time of the poll |

With reference to me, the pollsters noted,

“Those who feel familiar with him give him very high marks. His job rating is seventy per cent favourable. Most assuredly Roger Simmons, if he can be inveigled into the Crosbie camp, must be used heavily . . .”

Reading the pollsters’ assessment of my potential utility as an ally, it was easy to see why Crosbie was courting me. The truth is that I was quite attracted to his candidacy. The issues he espoused, sound economic development, a progressive social agenda, and fiscal probity, were all music to my ears. And I had been one of his biggest fans ever since he and Clyde Wells had stood up to Smallwood on the Come By Chance financial arrangements. But like many of Crosbie’s growing army of admirers, I couldn’t get past his clumsy, halting attempts at speechmaking. I had difficulty seeing that Newfoundland, where firebrand oratory is considered the requisite tool of every aspiring Moses, would embrace one so ill at ease at a podium.

My candidate of choice was Alec Hickman, Joey’s Justice minister. As the Smallwood-Crosbie duel became ever more toxic and polarized, Hickman’s chances, slim at the starting gun, withered with each passing day and each delegate selection meeting. By the time the leadership convention was gavelled to order, the outcome was a foregone conclusion. The first and only ballot confirmed the obvious:

Crosbie, John, 440

Hickman, Alec, 187

Smallwood, Joseph, 1,070

If there was any surprise, it was that Crosbie had fared much better than expected, given the ruthlessness and dominance of the Smallwood juggernaut.

End of an era

The six Tory MPs elected in 1968 quickly established themselves as Newfoundland’s voice in Ottawa, earning themselves the nickname “The Noisy Six.” History was being made, and not the version Smallwood would have written. For the first time since Confederation, Joey’s megaphone, his take on reality, had to compete with, indeed was being drowned out by, a far more progressive message. It was suddenly respectable for voters, long the captives of the Smallwood agenda, to openly debate and consider their electoral options.

Frank Moores, one of the six Tory MPs, became the vehicle for change. As the new provincial leader, he quickly mobilized voter discontent with Smallwood. His first election, in October 1971, ended Joey’s erstwhile stranglehold. When the votes were counted, Moores had won twenty-one seats, all but three of them gains from the Liberals. Joey got twenty seats. The rout was in full gear. Although Smallwood clung to power for another three months through a never-ending barrage of media assaults, court challenges, and constitutional musings, the writing was on the wall. Even a comical, yet pathetic, orgy of musical chairs couldn’t save him. The six-term premier who had held office for twenty-three years finally gave up the ghost in January 1972. Moores, having assumed the premiership, triggered the dissolution of the legislature, clearing the way for a second general election in five months and a Tory sweep of all but eight of the legislature’s forty-two seats.104

Toasting the new regime

I spent part of that very first day of a Tory government with the new premier. Sheer coincidence and Moores’s legendary bonhomie made it happen. As I entered the dining room of the original Newfoundland Hotel for a late dinner, I caught sight of the only other patrons, the premier and two of his ministers. Assuming they were heavily into affairs of state, I chose a table in the far corner, but before I could take a seat, Moores bellowed across the room: “Simmons, don’t like our company?” He insisted I join them for dinner, which I gladly did, surprised as I was that he would want me, a high-profile Liberal, to intrude at such a momentous time for him and his colleagues. We spent a memorable hour canvassing the events of the day and swapping stories. I raised an issue then preoccupying much of my attention, the rapidly unravelling economic situation in the Springdale area.

Premier Moores suggested the establishment of a joint committee with three representatives each from government and the Green Bay Economic Development Association, of which I was the president. Soon thereafter, the ad hoc group was put in place and tasked with exploring employment initiatives. One of the ministers at the dinner table, Ed Maynard, whose new responsibilities included Crown (public} lands, subsequently facilitated the transfer to the association of 1,000 acres of prime agricultural land which became the nucleus of a highly successful farming endeavour, which continues to thrive.

Moores’s collegial approach to governance launched a whole new era in provincial politics. For me, it opened the possibility of a career in elective office.

87 “Public Administration in Newfoundland during . . . Commission of Government,” Susan McCorquodale, thesis, Queen’s University, 1973

88 No Place for Fools, Don Jamieson, St. John’s: Breakwater Books, 1989, p. 22

89 No Holds Barred, John Crosbie, Toronto: McClelland & Stewart, 1997, p. 20

90 Confederation with Canada: 78,323; Responsible Government: 71,334. The turnout at the polls for the second vote was 85% of eligible voters compared to 88% in the first referendum.

91 No Holds Barred, John Crosbie, Toronto: McClelland & Stewart, 1997, p. 5

92 Trans-Canada Air Lines (TCA) is now Air Canada; Trans World Airlines (TWA) was bought by American Airlines in 2001.

93 Today, of course, the preferred term is flight attendant. What’s wrong with stewardess, I don’t know. Actress, mistress, princess, and seamstress have so far escaped the attention of politically correct revisionists, but don’t hold your breath.

94 “High Flight” by John Magee, an American aviator and poet who died at the age of nineteen in a mid-air collision over Lincolnshire, England, during World War II. He was serving in the Royal Canadian Air Force, which he joined before the United States officially entered the war.

95 A tiny fishing village, since abandoned, on Newfoundland’s south coast. Many of the characters and anecdotes in Russell’s plays and radio scripts draw on his two years at Pass Island.

96 Newfoundland: Dawn Without Light, Herbert L. Pottle, St. John’s: Breakwater, 1979, p. 66

97 “The Deserted Village” by Oliver Goldsmith, Irish poet and novelist, 1728–1774

98 A Quebec provincial cabinet minister and, later, leader of the separatist Parti Québécois and premier (1976–85) following the party’s seismic win at the polls

99 John Heywood, English playwright, musician, and composer, 1497–1580

100 Richard Cashin was the Member of Parliament for St. John’s West from 1963 to 1968.

101 Clyde Wells: A Political Biography, Claire Hoy, Toronto: Stoddart Publishing, 1992, p. 50

102 No Holds Barred, John Crosbie, Toronto: McClelland & Stewart, 1997, p. 74

103 Kris Kristofferson (1936–), American country music singer and songwriter

104 I heartily recommend John Crosbie’s autobiography, No Holds Barred: My Life in Politics, which details the unbelievable intrigue which characterized the slow-motion transition from Smallwood to Moores.