The penalty good people pay for not being interested in

politics is to be governed by people worse than themselves.

— Plato

My transition from community activist to elected politician was an easy one. Beginning with the St. Anthony outdoor rink project, I had fifteen years under my belt, reading expectations, identifying issues, working on solutions, troubleshooting individual concerns, and monitoring the public mood. Now I would get to pursue full-time what I had been doing on an as-required, ad hoc basis.

The opportunity to test the political waters popped up unexpectedly. In mid-1973, Frank Moores’s year-old administration was having its first public spat. Fisheries Minister Roy Cheeseman abruptly resigned his cabinet and legislative seats. He had represented the south coast constituency of Hermitage, far removed from Springdale. Yet I was recruited to carry the Liberal Party banner into the by-election, scheduled for late fall. I would become a carpetbagger, a species upon which I had long frowned.

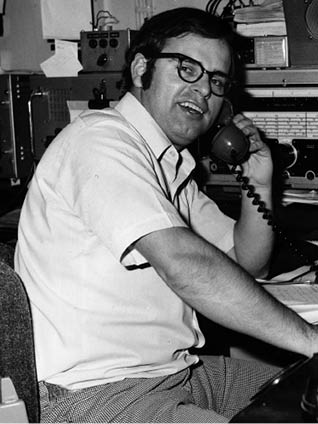

Yes, I had electoral assets. Two terms as the elected head of the NTA and my brief stint as president of the Liberal Party had given me a province-wide profile. As well, I was often the public face of Springdale’s economic diversification initiatives and a frequent media commentator on educational matters. And just a few months earlier, my daily voice reports from a cruise ship in the Mediterranean with 1,200 Newfoundland high school students aboard had been aired on province-wide TV and radio.

My potential electability was not in question. But, if elected, how could I effectively represent an area of the island where I had been, at best, an interloper? It was that issue that made me analyze my credentials and initially decide against entering the race. Phone calls from activists in Hermitage District, including one from the man who had won the seat for the Liberals in 1971, Harold Piercey, put my mind somewhat at ease, and I agreed to run.

SS Nevassa, Mediterranean Sea, 1972. With 1,250 Newfoundland high school students aboard the cruise ship, I filed daily audio updates for province-wide TV and radio. (Geoff Goodyear photo)

Milltown, NL, 1973. By-election campaign driver Bert Dowding and I prepare to fly to isolated communities. (Author photo)

The carpetbagger issue would raise its head during the campaign. My apprehension about it would linger, though it was tempered during the campaign as I listened to the aspirations and concerns of voters, realizing their issues were the same ones I knew first-hand from my days in St. Anthony and Springdale. And, it should be noted, the real skill of an effective politician lies not in being a walking encyclopedia but, rather, in the ability to quickly grasp the essence of an emerging issue and to know how to give strategic voice to it in a manner that brings about a satisfactory result.

The gang that couldn’t shoot straight

The government party and its candidates hold most of the cards during an election, from well-timed announcements to sod-turnings to visits by cabinet ministers. This is especially true during a by-election since the governing party’s candidate, if elected, will become a member of the caucus whose party holds the purse strings.

By-elections results are seen as barometers of the government’s standing in the eyes of the electorate. The by-election would be the first electoral test for the new Tory administration, and Premier Moores and his team spared no effort to influence the outcome. Hardly a day went by when there wasn’t a cabinet minister popping up somewhere in the district to announce project funding, cut a ribbon, or give a speech, all designed to give the Tory candidate the edge.

Indeed, it was the unseemly lengths to which the Conservatives went that handed me and my campaign a steady stream of election fodder. The sheer number of itinerant cabinet ministers became a laughingstock. One wag in a community of 200 population scoffed, “Yesterday was a slow day; we only saw three ministers!”

Perhaps the biggest laugh was reserved for the government’s ham-fisted approach to pork-barrelling. Determined to complete street paving in Harbour Breton before polling day, residents were treated to a once-in-a-lifetime spectacle: A plow scraped lily white snow off the street. Close behind, a paving machine disgorged jet-black asphalt. For once, there was no need of colour film in the camera to capture the moment for the evening TV news! In black and white, the picture was worth a thousand words and, in my case, at least as many votes. The backfire possibilities of voter bribery make it a lousy campaign strategy. In politics as in life, winning at all costs can get pretty expensive, for your pocketbook and your conscience.

Yet another silly little tactic portrayed the Tories as rank amateurs. In any political campaign, it is often not the mega announcements but the most miniscule missteps which determine the outcome. Capitalizing on the early darkness of a November evening and the absence of wagging tongues, a Tory campaigner relieved one of my youth volunteers of an armful of photo posters destined for the front windows of my supporters. The gossip network, a highly honed tool of election campaigns and rural communities, sprang into action. The rumour alleged the poster snatcher was none other than the premier’s parliamentary secretary, my old bosom pal, Brian Peckford. Flattery I can handle, but that he wanted thirty photos of my smiling face is more adulation than even I can handle! The scurrilous charge against him was never proven, although my erstwhile poster distributor, an alert twelve-year-old, was certain the right culprit had been fingered. The moniker “Poster Peckford” made the evening news and quickly gained currency, both during the campaign and beyond.

Staring down the posse

As the campaign neared its end, published polls were encouraging for our side. That sent the Tory camp into panic mode. A vitriolic negative campaign centred on my carpetbagger candidacy took wing, demoralizing even my staunchest supporters.

Three nights before election day, I arrived at a high school auditorium for a windup rally, the very school where my Tory opponent was the principal. Parked behind the school was the mobile home in which the candidate lived with his wife, who had been not too discreetly telling her friends she couldn’t wait to get out of town once the election was over, assuming of course that her husband was the victor.

I had not addressed the carpetbagger issue publicly. My workers said I had to do so or lose the election. I had mentally sorted out how I would handle the matter, so I was ready to follow their advice, though the strategy I had in mind was dicey and could backfire, since I was on the other guy’s home turf. I began my speech by saying,

“I hear there’s some concern about where I was born and where I’ll sleep if I’m elected. I had no say over where I was born. But I will have a say as to where I spend my time if I’m elected. I’ll spend some of it here listening to you. And I’ll spend the rest of it in St. John’s working on your problems.

“I’ll tell you where I won’t be. I won’t be down behind this building hooking up the trailer hitch so I can get out of town.”

The jam-packed auditorium erupted! Wild applause. Raucous laughter. The only times I heard about the carpetbagger label after were when constituents wanted to have a chuckle at the expense of the Tory candidate or his wife.

On paper, though, the odds favoured my opponent. If elected, he would join a government caucus with a full three years remaining in its mandate, an enticing prospect for rural electors who had been conditioned by Smallwood to look to government to address many of their problems. My election would mean three years as a member of a small opposition block.

Mischief with a motive

Well before my entry into elective politics, I had routinely been the subject of media stories, thanks to my involvement in province-wide issues and organizations, and I had cultivated an amiable working relationship with the print and electronic outlets.

Still, as the by-election campaign was winding down, I got a bee in my bonnet about CBC TV coverage. It had its beginning the evening before polling day. The reporter had been on the ground throughout the campaign, filing daily updates, and was therefore perceived by many as a reliable bellwether. He projected a runaway win for the government candidate, despite much evidence to the contrary. The actual result showed that the CBC stringer had not read the tea leaves well or had made a clumsy attempt to impact the outcome. I believed the latter.

Far from demoralizing my troops, the prediction redoubled their resolve to mobilize our supporters while infecting Tory voters with a complacency that convinced many of them there was no need to vote if a win was already in the bag. For them, their candidate, and the government, the election night count was a most unpleasant surprise:

Bert Meade, Progressive Conservative, 1,452

Roger Simmons, Liberal, 2,052

I had won my first contested election, and a sweet victory it was!

During my first federal campaign six years later, also a by-election, that same reporter again polished his trusty crystal ball the night before polling day. And, once again, he confidently predicted my demise, this time opting to name the NDP candidate as the one favoured to win. The clairvoyant’s horse came in a distant second.

On that latter by-election night, the CBC reporter, who richly deserves the anonymity I hereby accord him, showed up at my victory party. With a near-landslide vote in my favour, I decided to have a little fun at his expense, he who had twice written my political obituary. It requires a unique journalistic perspective to mistake momentum for rigor mortis!

Before cameras from two national television networks and a cluster of media mics, I, with sweet sarcasm, bestowed on my intrepid visionary the Roger Simmons Award for Consistency in Election Predictions.

The party faithful loved it. The press took note. Under the guise of playful mischief, but in the cause of payback, I had committed a stupid gaffe that would come back to bite me. What I had intended as a tongue-in-cheek settling of scores was seen by others, CBC on-air personnel among them, as a cheap shot at the venerable institution. Audiovisual recorders, like elephants, have long memories.

. . . a promise made is a debt unpaid105

Soon after my first by-election win (1973), actually two days before Christmas, I received a late-night phone call from a distraught woman.

“Roger, John is dead.”

I had no idea who was on the phone or who John was. Probably sensing my bewilderment, the woman continued:

“Rev. Spencer is gone away for Christmas. You’re the only one I can turn to.”

The mention of the clergyman’s name allowed me to narrow my frantic mental googling down to three communities where he had congregations, each of which, however, had many Johns. The question was, which John had died? The grieving woman was already at her wit’s end. I wasn’t about to push her over the edge by admitting I had no idea who John was. She solved my problem.

“You know, Roger, you were here in our kitchen, you sat in the rocking chair and had tea. You and John laughed a lot. When you left, you handed me a little card with your name on it. You said, ‘If ever I can help you, call me.’’’

Mary had no living relatives. When she got news that her husband of sixty years had passed away in a distant hospital, the sheer burden of her aloneness must have been devastating. In her most vulnerable moment, she decided to turn to someone who had promised to help her.

I spent the next day buying a coffin for John, parting with one of my suits and dispatching his corpse by boat for the trip home. It’s not quite the way I would have chosen to spend my first Christmas Eve as an elected representative. But what a valuable lesson Mary had taught me! Don’t make promises unless you are prepared to keep them. It served me well in the years ahead. It’s surprising how many politicians never learn that lesson and, in consequence, pay the price at the polls or in defensive encounters with the betrayed.

Paying the bills

The career switch from education to politics required many adjustments for me, a major one being financial. At the time of my election, I was the highest-paid elementary/secondary educator in Newfoundland, the result of a handsome wage supplement from my school board which augmented the stipend paid pursuant to the provincial salary scale.

My new job title, Member of the House of Assembly (MHA), carried with it a dramatic reduction in my personal income. I would now earn less than forty per cent of the salary to which I had become accustomed as a school superintendent. While my lifestyle has never been extravagant, it was painfully obvious I would need to find a source of additional income just to make ends meet. Once I had settled into my new legislative responsibilities, I canvassed supplementary income options and soon landed a small, education-related consulting contract. The extra remuneration eased my immediate cash flow requirements. Some years later, though, that income would morph into a giant Achilles heel, thanks to my preoccupation with political matters, my aggressiveness as a whistle-blower, an abysmal lack of attention to my personal affairs, and, arguably, thanks to a below-the-belt settling of scores by persons with long memories and few scruples.

Jobs, jobs, jobs!

As noted earlier, the province has always had the dubious distinction of having the highest unemployment rate in Canada. A dearth of jobs has long been the bane of rural Newfoundland, especially in my constituency, where all but a handful of communities depend solely on the fishery. The government-ordered shutdown of the commercial cod fishery in 1992 worsened an already bad situation and hastened the near-total demise of many once thriving outports. Heads of households and youth by the thousands were obliged to look elsewhere for an income source, accelerating the ongoing exodus of workers to distant places including the Alberta oil sands, the Great Lakes, and southern Ontario

It will come as no surprise, then, that a principal preoccupation of a politician representing those one-horse towns and villages is the urgent need to maximize employment opportunities. Their isolated location and their distance from major markets render impractical the establishment of most industries, with some exceptions in the resource and information sectors.

Milltown, St. Alban’s, and the other Bay d’Espoir communities in my former district are strung along a twenty-mile ribbon of road largely hugging the coastline of that scenic finger of Hermitage Bay. They boast an aggregate population of about 4,000. From the time its first non-aboriginal inhabitants arrived, the area thrived as a supplier of pit props for the mines of England providing steady jobs for hundreds of loggers. That source of employment dried up in the late 1950s, and the jobless rate skyrocketed. There was a bit of a reprieve in the late 1960s during the construction of the nearby Camp Boggy hydro power development. However, by the time I came on the scene, the area was in desperate economic shape.

Stirring the pot

Meanwhile, there was a battle brewing. With the completion of Stage 2 of the power facility in 1970, Camp Boggy was now fully operational. Soon after, Newfoundland Hydro implemented employment changes which didn’t sit well with the community and, particularly, those directly impacted. Specifically, the utility transferred certain functions, heretofore performed at Camp Boggy, to Bishop’s Falls and St. John’s.

The public reaction was immediate and visceral and soon caught the attention of the press. In a radio interview, John Kealey, then St. Alban’s acting mayor, gave voice to the public’s frustration. He noted that some of the affected workers had worked on Camp Boggy’s construction. Their insider knowledge, Kealey observed, could be used to disrupt the flow of electricity to the trans-island grid: “If you slacken a few bolts here and a nut or two there . . .”

Bay d’Espoir power is transmitted on high-voltage wires held aloft by steel lattice towers with stabilizing guy wires. It’s these nuts and bolts, of course, which keep the towers from crashing to the ground. Local police had heard enough. Here, they decided, was a scarcely veiled threat to damage the power infrastructure. I got a call from the RCMP. Aware that I had scheduled a meeting, for that very evening, of community leaders to deal with the public uproar over Hydro’s actions, the caller informed me that a plainclothes officer would sit in on our deliberations.

My role, the RCMP instructed me, would be to simply acknowledge the officer’s presence as someone who had asked to attend as an observer, without saying who he was. During the session, I observed that our visitor was fixated on one person. Once the meeting ended, the officer shook a few hands, including the one extended by the St. Alban’s acting mayor, who inquired, “Well, Sergeant, did you find your terrorists?”

“I found one, Mr. Kealey!”

Aquaculture gets a kick-start

John Kealey, my good friend and a feisty Irishman, grew up in rural Northern Ireland at Castledawson. In his late twenties, he arrived in St. Alban’s to work on the Camp Boggy project. He married a local lady, the amazing Fanny, and took up residence in the town. A half-century later, he’s still there, energizing and/or mesmerizing all who will listen to his rapid-fire analyses and innovative solutions. I was among those who listened.

Kealey, who had studied aquaculture in college, convinced me that salmon farming was a plausible option for Hermitage Bay. The thirty-mile stretch of sheltered waters from the head of Bay d’Espoir to the Atlantic Ocean was, according to Kealey, the ideal aquaculture location. But when I said so at a public forum convened to explore potential economic development possibilities, I was pretty well laughed out of the room. There were, fortunately, a few believers and some community leaders who, though skeptical, felt anything was worth a try. Mayor Doug Sutton of Milltown summed up the general consensus:

“What have we got to lose?”

With their guarded blessing, I secured a federal grant which funded an aquaculture feasibility pilot project, administered by the local development association, the very first such undertaking in Newfoundland. The project confirmed the potential for fish farming in the area. Shortly thereafter, three entrepreneurs, John Kealey being one of them, launched aquaculture enterprises. From that modest beginning, Bay d’Espoir is today a beehive of aquaculture activity which has become a major job generator and a catalyst for similar ventures elsewhere in Newfoundland. Province-wide, aquaculture is a growth industry and currently has an annual worth of $150 million.

Joey as the spoiler

Ed Roberts succeeded Smallwood as party leader prior to the 1972 Tory rout which left the Liberals with just eight seats in the forty-two-seat House of Assembly. Lingering anti-Joey sentiment, inside the party and out, didn’t help Roberts’s attempts to rebuild and reinvigorate the once-powerful Liberals. His many years as Smallwood’s fixer made him suspect to many, and his four years in the Smallwood cabinet pigeonholed him as yesterday’s man. The facts were quite to the contrary. Roberts and cabinet colleague Bill Rowe had begun to speak their minds and give voice to the widespread mood for change soon after they joined the inner circle in 1968.

Within two years of taking over the leadership, Roberts was obliged to put his job on the line, pursuant to the party’s constitution. Four candidates contested the 1974 leadership: Roberts, of course; Smallwood, a surprise to many, but not to anyone who knew his megalomania; Steve Neary and I were the others.

My candidacy seemed presumptuous to many. I had been in elective politics just a year. What party activists and pundits didn’t know was my game plan or, more accurately, Smallwood’s game plan. My decision to join the race was the direct outcome of a hush-hush rendezvous with Joe Ashley, Joey’s long-time confidant. Ashley told me that if Roberts led on the first ballot, as was widely expected, Joey would withdraw and support me. The strategy was driven not by any affection for me or my cause, but by Smallwood’s visceral hatred for Roberts.

At the leadership convention, the first ballot results were as follows:

Edward Roberts, 337

Joseph R. Smallwood, 305

Roger Simmons, 57

Stephen Neary, 24

The moment I heard those numbers, I knew they posed a large problem for me. No, it wasn’t the distant third-place finish. That was expected. Smallwood’s surprising strength, though less than Roberts’s, convinced Joey he should hang in, notwithstanding his/Ashley’s commitment to me. The results of the first ballot meant that Neary, as the candidate with the least votes, was obliged to withdraw, and I did so as well. While the rules allowed me to stay for the second ballot, there was no realistic reason for doing so, since in order to survive for a third round of voting, I would have had to overtake Smallwood on the second ballot, clearly not a very likely possibility. Joey’s support from the first ballot held firm on the second. The result of the ballot confirmed that the once-omnipotent leader was finally a spent force:

Roberts, 403

Smallwood, 298

With a nod to W. E. Henley,106 the bludgeonings of chance may have bloodied Joey’s head, but it remained defiantly unbowed. His unconquerable soul, or, more accurately, his egomania and venom, would shortly land him yet one more time in a fight he could not win.

Frank Moores had swept the province in the 1972 general election. Just three and a half years into his mandate, he went to the polls again in September 1975. Following the 1974 Liberal leadership campaign, three of the candidates, Roberts, Neary, and me, closed ranks, and with Roberts leading the charge, the nine-member Liberal parliamentary caucus became an effective, cohesive unit. Meanwhile, the Tory government’s honeymoon with the electorate was long since over. The administration’s messaging had only one string in its bow, fixated solely on denigrating its predecessor, which began to wear thin with the public. Liberals had reason to be optimistic about the impending election.

There was one problem, however: The Smallwood political corpse was not yet cold. Rigor mortis set in, energizing a few last twitches which didn’t bode well for the Liberal leader or for the party’s fortunes at the polls. Having mounted a failed challenge to his successor and having been rejected by his party for the first time, Joey was in no mood to close ranks. Instead, he jumped ship, formed the Liberal Reform Party, and won four seats in the 1975 election. The two Liberal factions together garnered fifty-four per cent of the vote, but the split allowed the Tories to win a second majority. Slim pluralities in several seats pointed to a victory for Ed Roberts and the Liberals, absent Smallwood’s treachery. I was re-elected, and my party was once again in opposition.

Making a difference

Keeping in touch with constituents between elections is any good politician’s bread and butter. It is also a never-ending challenge, particularly so in rural areas where much valuable time is consumed just getting from one place to the next. A further restriction is the dearth of public venues. Other than private homes and small shops and convenience stores, the only buildings in many small communities are the post office and the church. I would often gear my arrival at a post office to coincide with the time frame when the day’s incoming letters and parcels had been sorted. As my electors picked up their mail, I picked up the local pulse and constituent inquiries for follow-up.

One other routine worked well. As I drove from one community to the next, I would mentally pre-select a house at random, say, the next two-storey dwelling on the right with laundry on the clothesline. On one such occasion, my door-knocking summoned a young woman with a baby in arms and a small boy clinging to her skirt. As I sat in her kitchen and chatted, I watched her three-year-old, the same age as my son, who appeared to be hiding his right hand from my view. His mother, sensing my curiosity, took her child’s hand and opened it, at least partly, to reveal a palm that had been severely burned, Tommy having fallen the previous year onto the floor furnace. She had removed the protective grating for a moment as she vacuumed. She told me resignedly, “The doctors have done all they can do.”

I knew better. Rage boiled inside me at the thought that some pathetic excuse for a physician had decreed this child would go through life with a withered hand. Exercising care not to raise false hopes and armed with the mother’s agreement that she was open to the possibility of getting a second opinion, I headed straight for St. John’s. Next morning, I called on the province’s deputy minister of Health. Dr. Lorne Klippert gave the matter the priority it merited, and in time, Tommy had a fully-functional right hand.

Anatomy of a scandal

There is a classic yet simple template for many, if not all, government spending scandals which involve the illegal disbursement of public funds to non-government recipients. A person (or persons) in the private sector with contacts in the bureaucracy gets greedy. He/she finds a public servant who is equally greedy. They both want lots of money, and they need each other to flow the money in a manner that minimizes the probability of being found out. Their only scruple relates not to ethics or morality but to whether they may get caught.

It is instructive to note that this fraud template doesn’t require the collusion or knowledge of political masters. Indeed, that would scuttle the entire scheme or require more sharing than greed would condone. Besides, government ministers get defeated at the polls. Bureaucrats, like the Energizer bunny, just keep on going.

The 1976 Auditor General’s report to the Newfoundland House of Assembly contained a small but intriguing paragraph that caught my attention as chairman of the Public Accounts Committee (PAC), an all-party, post-audit panel charged with determining whether public money has been spent according to law and whether commensurate value was received. The item in the AG’s report intimated that certain companies may have contravened the province’s public tender legislation, enacted less than three years earlier to great Tory fanfare. The curious thing about the AG item was that the alleged perpetrators were identified only as Companies A, B, and C, which signalled to me that the Auditor General didn’t have enough smoking-gun evidence to name names but, nevertheless, felt an obligation to draw the House’s attention to the matter.

London, England, 1981. Schmoozing with the Iron Lady, British PM Margaret Thatcher. (Author photo)

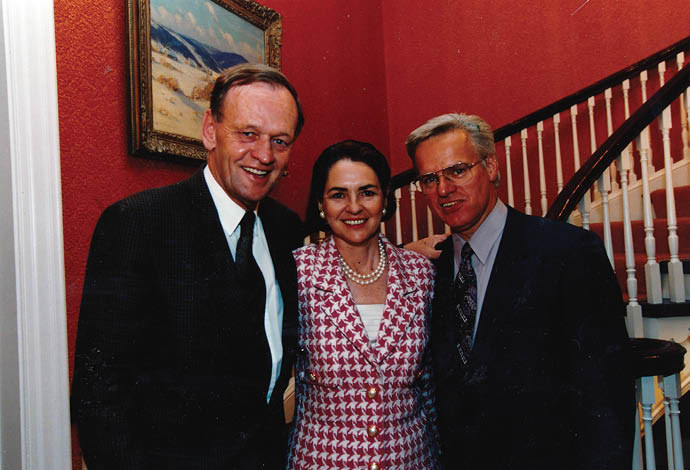

Ottawa, 1983. I hosted a Parliament Hill reception for the honourable Don Jamieson on his appointment as Canada’s High Commissioner to the United Kingdom. L-R: Prime Minister Pierre Trudeau, Jamieson, me, Barbara Jamieson, Miriam Simmons. (Author photo)

St. John’s, 1987. Leadership and support staff of the Official Opposition, Newfoundland House of Assembly. L-R: Rex Murphy, Ruth Sheppard, Gloria Hibbs, Kim Ploughman, Delores Linehan, Daisy Parsons, Rosie Frey, Opposition House Leader (later Premier) Beaton Tulk, Marie Walsh, Opposition Leader Roger Simmons, Joan White, Phyllis Fiander, Opposition Whip (later Speaker) Tom Lush, Barbara Nugent, Cathy Brodie, Cindy Gollop. (Author photo)

St. John’s, 1987. Leader of the Opposition, Newfoundland. (Author photo)

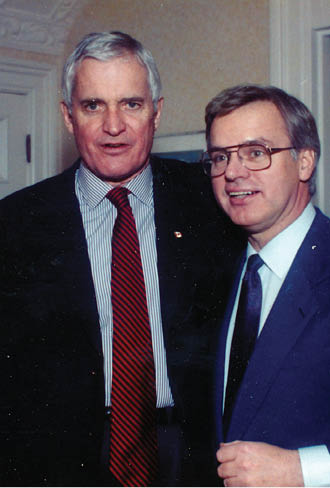

Ottawa, 1989. With Right Honourable John Turner. (J. M. Carisse photo)

Airborne between St. John’s and Stephenville, NL, circa 1989. Renowned Franco-Newfoundland fiddler Émile Benoit plays a jig he composed, “The Roger Simmons Breakdown.” (Author photo)

Oslo, Norway, 1990. At home with the Ingstads, Helge and Anne, of L’Anse aux Meadows fame. (Author photo)

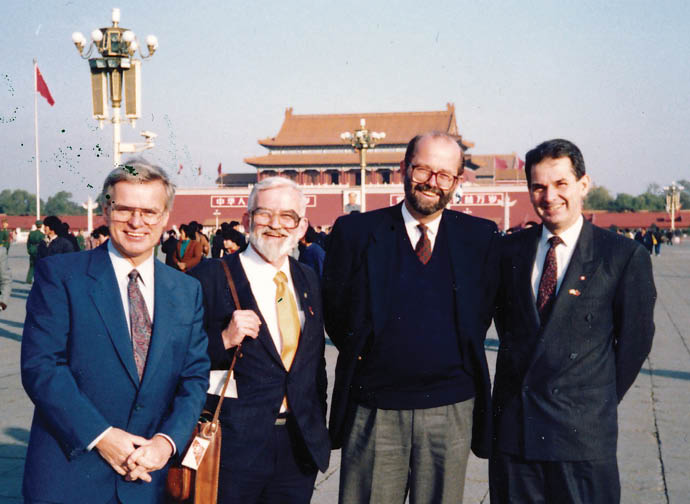

Beijing, China, 1990. Following the 1989 Tiananmen Square student protests, three MP colleagues and I were the first elected officials from a western democracy to visit the People’s Republic of China. L-R: Roger Simmons, Dan Heap (NDP, Ontario), former Speaker John Bosley (PC, Ontario), and Bob Wenman (PC, British Columbia). (Author photo)

Rio de Janeiro, Brazil, 1992. Just five months after her historic space flight, our focus was decidedly down-to-earth as astronaut Roberta Bondar and I teamed up to arrange seating for a Canadian NGO seminar. (Author photo)

Tokyo, 1992. Federal Fisheries Minister John Crosbie and I, his Official Opposition critic, travelled to Asia and Europe for bilateral talks on foreign overfishing. (Author photo)

Ottawa, 1993. Taking the MP oath of office for the fourth time. L-R: My sons, Mark (14) and Paul (17), Captain Randy Hicks, Senator Phil Gigantès, Colonel Hugh Tilley, Mildred Conibear, Colonel Noreen Tilley, Deputy Clerk of the House of Commons Mary Ann Griffith, Majors Cliff and Ruth Holman. (Author photo)

Ottawa, 1994. I was honoured to conduct the Salvation Army International Staff Band in its Parliament Hill rendition of “Goldcrest,” a jazzy march by Army officer and composer James Anderson. (Author photo)

Saint-Jean-sur-Richelieu, QC, 1994. Improving my oral French at the Royal Military College with MPs Jean Augustine (L, Ontario), left, and Sue Barnes (L, Ontario). (Author photo)

Ottawa, 1996. Five of the fabulous persons who staffed my offices. L-R: Janice Lane (Marystown, NL), Gwen Lomond (Stephenville, NL), and in Ottawa, Sarah Watts-Rynard, Joanne Blondeau, and Catherine Parker. (Author photo)

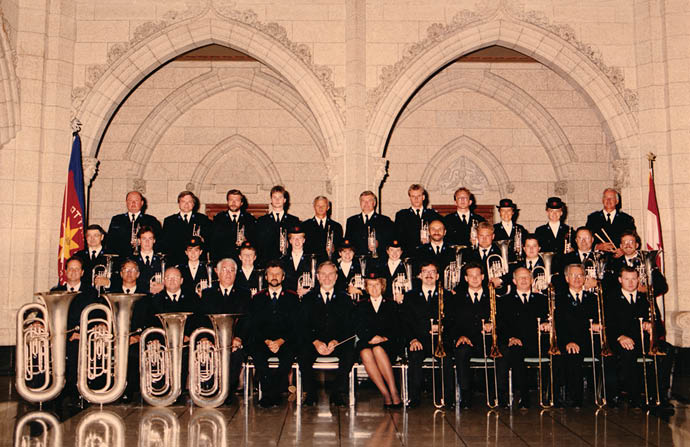

Ottawa, 1992. The Salvation Army’s Ottawa Citadel Band posed in front of the House of Commons. L-R, front row: Eric Dinsdale, Albert Verhey, Munden Braye, Allan Bacon, Capt. David Ivany, Bandmaster Douglas Burden, Capt. Beverly Ivany, John van Gulik, Jr., Geoff Clayton, Fred Waterman, Roger Simmons, Leonard Ferguson. Middle row: Ted Venables, Calvin Wong, Kerry Brazeau, Arlene van Gulik, Kristen Hollman, Donna van Gulik, Stephanie Hodgson, Cyril Fry, Karl Rayment, Sean Wong, John van Gulik, Peter van Gulik. Back row: Brian Greenwood, Allan Weatherall, Dave Perry, Brent Ferguson, Martyn Hodgson, Jim Ferguson, Curtis Jackson, Scott van Gulik, Linda Colwell, Debbie van der Horden, Ralph Verhey. (Author photo)

Ottawa. 2001. Canada’s North American heads of mission. L-R: Roger Marsham, Buffalo; Susan Thompson, Minneapolis; Colin Robertson, Los Angeles; Michael Phillips, New York; Jon Allen, DG, North American Bureau; Hon. John Manley, Minister of Foreign Affairs; John Tennant, Detroit; Astrid Pregel, Atlanta; Chris Poole, Chicago; Hon. Roger Simmons, Seattle; Allan Poole, Dallas; Keith Christie, Mexico; Marc Lortie, ADM Americas. (Author photo)

Seattle, 2002. Roger Simmons with Bishop Desmond Tutu. (Author photo)

USS Abraham Lincoln, Pacific Ocean, 2003. Honorary Captain Cedric Steele, Canadian Navy, and I helicoptered to Victoria, having spent the night on the aircraft carrier. (Author photo)

North Saanich, BC, 2004. Birthday boy!

My stepdaughters, Stacy, left, and Holly. (Author photo)

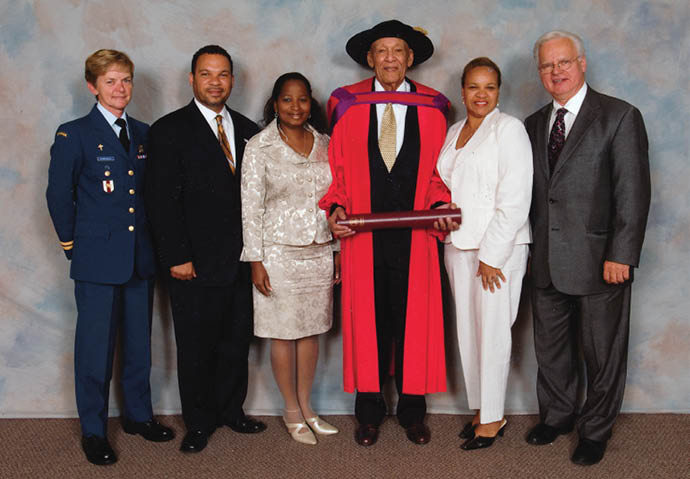

St. John’s, 2008. Memorial University saluted the achievements of Lanier Phillips with an honorary degree. L-R: Capt. Cavell Simmonds, Terry Phillips (Lanier’s son), Terry’s wife, Tamara, Dr. Lanier Phillips, Dr. Vonzia Phillips (Lanier’s daughter), Roger Simmons. (Author photo)

Atlantic Ocean near Great Brehat, NL, 2016. With Glorina Drodge, reliving cherished memories and making new ones. (Stephen Simms photo)

I paid a visit to AG David Howley’s office and became quickly convinced that the obscure paragraph was fertile ground for digging and well within the mandate of the Public Accounts Committee. I also learned that many of the disbursements from public coffers related to a small kitchen fire in the College of Fisheries, a Crown property. I asked the AG, “How do I get my hands on a copy of the fire commissioner’s report?”

Howley winked and said, “ Maybe you’ll get lucky!” When I opened my office door next morning, I stepped on a plain brown envelope. Inside was the damage assessment done shortly after the fire had been extinguished. It was but the first of many plain brown envelopes that would come into my possession in the months ahead.

The fire commissioner had estimated the cost of repairing the damaged kitchen at $17,000. The government’s Public Works department had paid out more than $600,000 to two corporate entities, both controlled by the same individual, for repairs to the kitchen. The Public Tender Act stipulated that expenditures exceeding $10,000 required a competitive bid process. Lesser amounts could be authorized by work order.

In the case of the kitchen fire, one official had signed all the work orders, being careful to keep the amount of each just under $10,000 and issuing every last one to the same two contractors. The official’s ostentatious oceanfront property suggested a lifestyle well beyond the capacity of his paycheque to underwrite.

The official also knew how to cover his tracks. Other than the work orders, there wasn’t a single shred of documentable evidence linking him to the contractor. When the axe fell, it landed nowhere close to the official’s neck. The contractor, Alex B. Walsh, wasn’t quite so lucky.

Brass-knuckle shenanigans

Brown envelopes were not the only intruders. On arriving at my St. John’s home following the weekend at Kona Beach, my campsite facility in central Newfoundland, I faced a surprising, unnerving disarray. The upholstered sofas and chairs in my living room and home office had been slashed. The walls and carpet had also been vandalized. I called the CID.107 I was in for another surprise or two. Next morning, I went to my parliamentary office, only to discover that a locked filing cabinet had been forced open. I made a second phone call to the CID. A day or so later, an officer, having completed his investigation of the two incidents, came to see me.

“Do you have enemies?”

“In my line of work, probably. Why? What’s up?”

“The break-in at your house was made to look like vandalism, but that was to cover the tracks of the perpetrators. They were looking for something. Our examination of the contents of the filing cabinets in both your offices tells us that someone went through each file, page by page.”

Bad news comes in three, they say. My third rude awakening was exactly that, a phone call at 3:00 a.m. I hustled from the master bedroom to my adjoining home office to grab the receiver before the ringing stopped.

“Are you Roger Simmons?”

“Yes. Can I help . . .”

“You have a son named Paul. He was born October 11, 1976. Do you want him to grow up?

Click. He was gone. Message delivered. I called the CID a third time. Nothing came of the three incidents, despite a commendable police effort. They and I knew the three intrusions were a classic needle-in-a-haystack case.

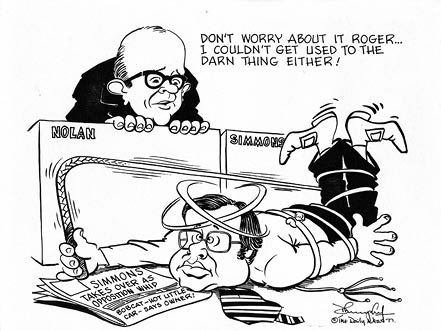

St. John’s, 1977. I succeeded broadcaster and MHA John Nolan as caucus whip. (Daily News cartoon)

St. John’s, 1977. Newfoundland’s Minister of Public Works, Joe Rousseau, and I were the subjects of a Daily News cartoon.

There was no doubt in my mind, and there’s none now, that the furtive filing cabinet searches and the middle-of-the-night phone threat were connected to the Public Works probe. If a couple of greedy guys had successfully conned the government out of $600,000 over a three-year period, they certainly had the smarts, motive, and perversity to pull those cowardly stunts at my expense or to instruct their henchmen to do so. Yet the lengths to which they were prepared to go to curb my legitimate legislative activities were small potatoes compared to something else which, I firmly believe, they did several years later, after I had left the provincial arena.

Outsmarting government patsies

There are institutional constraints on the ability of a public accounts committee to do its job. The provision that the chair must be an opposition member does give the presiding officer a wide berth in determining the committee’s agenda. However, since the ratio of government and opposition members reflects their respective House numbers, a majority government can control the committee’s activities, including, importantly, its findings and recommendations.

When I first raised the Public Works spending issue, the Tory majority used every trick in the book to frustrate the committee’s deliberations. Every time that I, as the chair, or the clerk proposed a course of action, the four government members routinely voted it down. One of the many brown envelopes that showed up under my door included a note that read, “If I were you, I would try and reconcile the number of mercury vapour lights in the Public Works hangar with the purchase invoices.”

Experience had long since taught me I would not get committee approval for a fact-finding excursion. So, I opted for a little improvisation in the interests of accountability. The moment I called the committee to order, I said, “The government hangar at Pepperrell has a whole bunch of mercury vapour lights, and I plan to find out how many. The committee is adjourned”—I banged the gavel—“and will convene in thirty minutes in the hangar.”

Regina, SK, 1977. Dr. Ray Winsor, vice-chair of the Newfoundland Public Accounts Committee, and I met with Saskatchewan Premier Allan Blakeney. (Author photo)

Ignoring energetic protestations from the Tory majority, I made a beeline for the door. The government members, not about to trust me to do the counting, were already in the hangar by the time I arrived. The count completed and duly noted by the clerk, we convened for the third time that day back at our regular venue. The committee researcher read the related paid invoices into the record, revealing the government had been conned into paying for many times the number of light fixtures than had been supplied. In a friendly aside to Dr. Ray Winsor, my vice-chair, a government member and respected dentist, I said, “The jig is up. First, that very expensive kitchen fire. And now, enough fixtures to light up a cruise ship. If I were you, I’d get on the right side of this boondoggle while there’s still time.”

Thereafter, the committee became a relatively collaborative effort, and its report to the House documented a litany of abuses that the government could ill afford to sweep under the carpet.

Filibustering for a cause

House of Assembly rules provided that, as the opposition spokesperson first responding to Finance Minister Bill Doody’s budget motion, I had unlimited speaking time. I gave notice it was my intention to keep talking until the government agreed to establish a judicial inquiry into the Public Works spending irregularities. I began to speak late Thursday, and as of noon Friday, I was showing no signs of running out of steam any time soon. When nature called or I needed a little sustenance, my late, great friend and colleague, the indomitable Steve Neary, a past master of both parliamentary procedure and histrionics, could be counted on to incite a procedural row to allow me to attend to business.

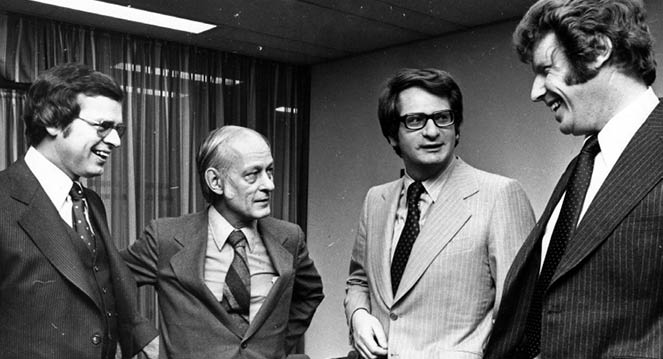

Montreal, 1977. L-R: Roger Simmons, Quebec Premier René Lévesque, Newfoundland Leader of the Opposition Edward Roberts, and Labrador MHA Ian Strachan. (Author photo)

By mid-afternoon, the government front bench, procedurally unable to move the adjournment motion unless I yielded, faced the unpalatable choice of caving in to our demand for an inquiry or enduring, well into the weekend, my non-stop verbiage. Finally, Minister Doody, having conferred by phone with Premier Moores, who was out-of-province, rose under the guise of a point of order.

“Mr. Speaker, I wish to inform the House that the premier has agreed to set up a public inquiry. . . . Now, will the Member for Burgeo–Bay d’Espoir sit down?”

I collapsed in my seat as my colleagues thumped their desks. We had won!

The soon-appointed judicial probe and its hair-raising report would, in time, put a large dent in the government’s claim as trusted custodians of the public purse, abort the careers of two ministers, and send a greedy businessman to jail. Alex Walsh was convicted of fraud and sentenced to three and a half years in New Brunswick’s Dorchester Penitentiary. It would also set the stage for a settling of scores, with me on the receiving end.

Caught in the middle

The two members of cabinet on whose successive watches the fraud had been perpetrated were hounded into resignation. Joe Rousseau’s only possible sin may have been one of omission, though how he could have prevented the fraud is beyond me. Rousseau was a decent man and my long-time friend. Indeed, he and I had briefly taught school together. But he was also a political adversary, and what my party, me included, did to his reputation, and possibly his health, was shameful and unwarranted. It was easily the low point of my quarter-century in elective politics and something I will always regret.

The case of the other minister, Dr. Tom Farrell, is less clear-cut. While there was no evidence that he benefited financially from the spending scandal or was even aware of the matter until the Auditor General flagged it, his alleged involvement in another shady shenanigan led to a public inquiry and the filing of charges against him which were later dismissed. Clyde Wells acted for Farrell and received an anonymous phone call “threatening to kidnap the Wells children if the case was not dropped.”108 The inquiry judge was also targeted with a similar call.109

Aviation icon Gene Manion, in his 2009 book, Flying on the Edge, recounts a 1972 meeting with recently appointed Minister Farrell. Manion’s company had won a publicly tendered bid to provide helicopter services to the province, but according to Manion, Farrell made the contract award conditional on a ten per cent donation to the minister’s political party. Manion records, “I grabbed the contract off his desk, ripped it to shreds, tossed the pieces on his desk . . . and stomped out of his office.”110

John Crosbie asserts in his autobiography that the Moores administration put honesty back into government.111 There is considerable evidence to support that claim. But there were exceptions, the most egregious being the Public Works scandal. And, according to Manion, at least one minister was on the take.

Unscrupulous tactics

Our adversarial system of governance is soundly based and, for the most part, serves well its intended purpose of ensuring good government, adequate accountability, and transparency. Here’s the “but”: When an opposition member gets on a roll about some government shortcoming, the partisan political objectives are served only if linkage to government politicians can be shown or, at least, insinuated. Too often, such linkage exists solely in the fertile mind of an unscrupulous politician whose yardstick for success is tonight’s TV clip or tomorrow’s headline, not the fairness of the pursuit or the veracity of the accusations.

I remember well the many early mornings in Ottawa when we, the Liberal opposition strategy group, all of us skilled at finding jugulars and going for them, would gather to decide the day’s line of attack during the Oral Question period in the Commons. Our House Leader, Herb Gray, could always be counted on to keep some sanity in the room: Do we know that for sure? Do we really want to go there? Is that fair?

Herb was no shrinking violet, to be sure. He could hold his own with the best of them in a frontal attack on the floor of the House. But, to his great credit, he never let the thirst for the kill dilute either his sterling integrity or his marvellous humanity. Deliberative bodies the world over need more Herb Grays!

Man on a mission

A distinct bonus of the political life is the cast of characters with whom you get to rub shoulders. One I came to know well and admire deeply is John Crosbie. If ever a man entered the political arena for all the right reasons, it was Crosbie. He came well-equipped. A mind like a steel trap. Independently wealthy, so he wasn’t for sale. Firmly held convictions. Highly educated. Self-deprecating wit. For all his riotous display of tough partisanship, Crosbie doesn’t have a mean bone in his body.

When he was first elected to the Newfoundland House of Assembly, following a stint as deputy mayor of St. John’s, he lacked one essential skill, an easy command of oratory. With speech coaching, he not only transformed himself into a competent speaker with a devastating brand of humour, but also one of the most effective communicators in public life and a master of the thirty-second sound bite.

Now, if you think John Crosbie is the smartest creature on two legs, you haven’t met Jane Crosbie. Feisty, acerbic, lovable Jane. She was succinctly profiled as a spirited woman with views of her own by Susan Riley, writing in Maclean’s magazine.

Over the years, and particularly in the early 1990s, it was my privilege to spend time with John and Jane, sometimes in foreign capitals where we rallied support for Canada’s position on overfishing of transboundary fish stocks. The three of us and two of Minister Crosbie’s staff were in Tokyo. After a full set of meetings with Japanese officials, we were unwinding over dinner and John was in full oratorical flight. Jane was not buying her husband’s assessment of the day’s events and dramatically registered her disagreement. Sitting beside her, I became aware of her swift kick to John’s shins. Communication doesn’t have to be verbal to be effective!

John Crosbie and I are kindred spirits. There is, though, one area of fundamental difference. He has written that Liberals “have no principles whatever . . . no scruples and no honour”112. I disagree. Oh yes, I can name a few rogues who have held influential positions in the Liberal party. Equally, I have known Tories who fit the category. I do take exception, however, to Crosbie’s tarring all Liberals with the same brush. Long-time senator Eugene Forsey was no rogue. Nor was Monique Begin, Iona Campagnola, or David Collenette113. Far from being exceptions that prove the rule, they number among an army of Liberal politicians who have served Canada well with their integrity intact. In the same vein, I have never pigeonholed Mary Collins or Ray Hnatyshyn, Flora MacDonald or Don Mazankowski114 as morally depraved simply because they didn’t belong to my party. Each of them and countless other Tories did a stellar job of pursing their mandates without ever stooping to unprincipled, venal tactics.

Conservatives, NDPers, Bloquistes115, and Liberals are all sprung from the same root. Like fishermen and scientists, housewives and clergymen, some of them are rotten apples. The saving grace, the overwhelming truth, is that all but a sorry few are principled people, irrespective of party label or station in life.

In the Newfoundland House of Assembly, I touched off a procedural row by saying, in reference to Justice Minister Alec Hickman, that, “There’s nothing worse than a reformed alcoholic!” In the context of the moment, my comment was an allusion to a well-known phenomenon. A convert to a new cause can be unbearably preachy in decrying what s/he once embraced. Hickman, a former Liberal cabinet minister, had switched allegiances and joined the Tories, as did Crosbie, which probably best explains the latter’s scathing assessment of Liberals as a genre.

Viceregal panache

En passant, I just loved Prime Minister Harper’s December 2007 appointment of Crosbie as lieutenant-governor of Newfoundland and Labrador. The minute I got wind of the announcement, I emailed him my congratulations, saying his new assignment was “richly deserved and deliciously diabolical, because it will drive your few remaining detractors absolutely bonkers!”

The refreshingly irreverent Crosbie made liars of his critics as he and Jane brought new substance and class to the viceregal office. As Her Majesty’s envoy, John followed in the footsteps of a long line of outstanding appointees, some of whom had made a real contribution toward the archaic institution’s becoming more in step with the times and the citizenry. Crosbie’s two immediate predecessors certainly qualify.

Before becoming the Queen’s representative in 2002, the intellectual Edward Roberts had a successful political career spanning thirty years and has the distinction of being the only minister to sit in cabinet with Smallwood, Wells, and Tobin, the province’s first three Liberal premiers. As party leader, Roberts recruited me into politics, and I am indebted to him for doing so and for his wise and unselfish mentoring during my formative years as a legislator.

Dr. Max House, lieutenant-governor from 1997 to 2002, spent thirty years as a professor of neurology. He is known worldwide as a telemedicine pioneer, having founded Memorial University’s telemedicine centre, recognized internationally as the model for such systems. The Canadian Medical Association saluted him, saying, “his use of communication technology to deliver care elevated the standard of medical care in some of Canada’s most remote locations.”

The current lieutenant-governor is the indomitable Judy Foote, the first woman to hold the position. She’s already devoted more than two decades to public service as an elected member and cabinet minister, provincially and federally. She becomes the fourteenth lieutenant-governor since Confederation, the ninety-second since John Guy took office in 1610, and number 104, if you include the dozen French appointees when France held sway in parts of Newfoundland for the half-century ending in 1713.

The pot calls the kettle black

Newfoundlanders have gone to the ice since the early 1600s. The annual seal hunt has long been a source of supplementary income for seasonal fishermen and a welcome foodstuff, even a delicacy for many.

By the mid-1970s, the seal hunt was in the sights of animal rights activists and the anti-fur lobby. Each spring, St. Anthony, on the island’s northern tip, was transformed into a global media centre as celebrities and spin doctors descended on the community to demonize the hunt. When two US congressmen showed up in March 1978, the media frenzy was ratcheted up a notch. Vermont’s Jim Jeffords and Leo Ryan from northern California held forth in the local motel’s cramped, smoky boardroom.

A Newfoundland government minister and two other Members of the House of Assembly, Opposition Leader Bill Rowe and I, were there as well, both as a courtesy to our distinguished US visitors and also to ensure their version of reality was duly rebutted, if called for. The congressmen railed at length about the alleged barbarity of the seal hunt. The minister, blunt-talking, no-nonsense John Lundrigan, got quickly past the courtesies and went straight for the jugular: “You want to save some seals? Why don’t you go to the (US) Pribilof Islands116 in your own backyard? One of these days, you’re going to stick your nose in once too often!”

Little did Minister Lundrigan expect, once too often would come so soon and so tragically. Just eight months later, Congressman Ryan perished in a hail of bullets on the tarmac in Guyana as he attempted to leave Jonestown the day that 918 men, women, and children died in Jim Jones’s diabolical Kool-Aid massacre.

St. Anthony, NL, 1978. US politicians protested the seal hunt. We treated them civilly and, their misguided arguments, firmly. L-R: Congressman Leo Ryan (D-California), Newfoundland Liberal Leader Bill Rowe, me, MP Bill Rompkey, Congressman Jim Jeffords (R-Vermont). (Author photo)

105 “The Cremation of Sam McGee” by Canadian poet Robert W. Service

106 English poet, critic, and editor who wrote the poem “Invictus”

107 Criminal Investigation Division of the Royal Newfoundland Constabulary, the city’s police force.

108 Clyde Wells: A Political Biography, Claire Hoy, Toronto: Stoddart Publishing, 1992, p. 99

109 Ibid

110 Flying on the Edge, Gene Manion, St. John’s: DRC Publishing, 2009, p. 194

111 No Holds Barred, John Crosbie, Toronto: McClelland & Stewart, 1997, p. 137

112 No Holds Barred, John Crosbie, Toronto: McClelland & Stewart, 1997, p. 186

113 Former Liberal MPs and ministers from Quebec, British Columbia, and Ontario, respectively

114 Former Conservative MPs and ministers from British Columbia, Saskatchewan, Ontario, and Alberta, respectively

115 New Democratic Party; Bloc Québécois, the Quebec separatist party in federal politics

116 A group of four volcanic islands in the Bering Sea, 200 miles off the coast of mainland Alaska, with a population of 700. Subsistence hunting of seals by native Aleuts is legal.