If you can trust yourself when all men doubt you,

But make allowance for their doubting too . . .

Yours is the Earth and everything that’s in it.

— Rudyard Kipling, English journalist,

poet, and novelist, 1865–1936

Fall seven times; stand up eight.

— Japanese proverb

My stint in Pierre Trudeau’s cabinet was brief. Revenue Canada saw to that. A personal income tax issue, which I had been given to understand had been resolved, fuelled by a payback vendetta aimed at several MPs, me among them, postponed, and ultimately derailed, my opportunity to play a meaningful role in government. In less than two weeks, I went from rising star to a potential shooting star.

The sudden reversal of fortunes is a twisted tale of brazen treachery. RevCan had thrown in the towel, shut the book on my tax issue. Then, from their warped perspective, the fertile minds in the tax agency got lucky. Their saving grace was my appointment to cabinet and, even more significantly, a monstrous gaffe by another government agency. In the blink of an eye, RevCan fixed on a whole new, bold strategy: metamorphosis. Transform a high-profile politician into a poster boy for its cause.

In response to Gordon Osbaldeston’s August 18 phone call, I immediately returned to the nation’s capital. On Sunday, August 21, I drove to Val Morin, Quebec, north of Montreal and 200 kilometres from Ottawa. There, I met with the PM’s principal secretary, Tom Axworthy.

Trustworthy, affable, and a brilliant mind, Axworthy ranks easily as one of the most competent and committed public servants to ever grace the Langevin Block156 edifice. As deputy principal secretary and, then, in the top job, he ran a tight ship. Among MPs, he had a solid reputation for keeping his ear to the ground and for being a ready pipeline to the PM.

Tom and I got quickly to the subject at hand, reviewing the bizarre sequence of happenings that had culminated in that moment, analyzing my conundrum and canvassing options. The meeting served as a valuable preparation for my meeting, the following day, with the Clerk of the Privy Council.

The right decision

I met with Osbaldeston Monday morning. Up until that time, I was firmly of the view that there had been some mix-up which could be straightened out. The Clerk quickly disabused me of that notion when he indicated that RevCan had informed him there was a fifty-fifty chance that charges would be preferred against me. The moment I heard that, it was crystal clear what I had to do. Resignation from cabinet was the only appropriate course of action. I asked Osbaldeston to immediately be in touch with the prime minister, who was travelling abroad, and to convey my decision to him. The Clerk placed the call, spoke with Trudeau, then handed me the phone. Asked by the PM to summarize the issues in play, I did so. He expressed himself “astounded” by the turn of events and said, “If you believe it’s the right decision, I accept your resignation.”

He concluded our conversation by indicating that he would be in touch when he got back to Ottawa. The prime minister called me Saturday evening, September 4, soon after returning from his overseas trip.

In theory, at least, there were options other than resigning, but whether survival in cabinet was possible is entirely beside the point. As I told my House of Commons colleagues on September 12, the first sitting day following the summer recess,

“There is only one way to be in cabinet: Because you have legitimacy, because you have the full right to be there. When I was sworn in, I had legitimacy. Once the circumstances which triggered my resignation arose, I no longer had unabridged legitimacy. Questions would arise: Should I be in cabinet in those circumstances? If the answer is ‘no’ or ‘maybe not’ or even ‘maybe,’ unless the answer is an unqualified ‘yes,’ my full legitimacy as a minister would be circumscribed, compromised, emasculated. . . . I felt it would be wrong to continue in cabinet once I had learned that the legal aspect of the tax matter was still outstanding, irrespective of whether a charge would ultimately be laid or not.

And there was a fairly easy pragmatic choice to be made: to somewhat damage my credibility by resigning from cabinet so ridiculously soon after my appointment, even if my reasons never became public, or to ultimately destroy my credibility altogether by continuing in a position for which I lacked unbridled legitimacy.”157

As I spoke, Senator Eugene Forsey sat in the gallery opposite. The retired parliamentarian, a Newfoundlander, native to my electoral riding, and a valued friend and mentor, was one of the foremost authorities on the Canadian constitution. Not normally given to hyperbole, Forsey wrote me later that day to say that my statement to the House had been a “masterpiece of erudition, concise yet comprehensive, candid, by the book.”

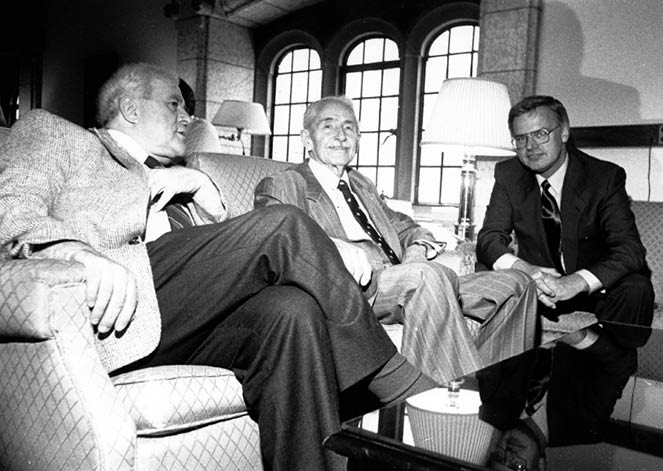

Ottawa, 1989. L-R: Steve Neary, retired senator Eugene Forsey, and me. (Author photo)

A few days prior to my House of Commons intervention, I spoke in similar vein to the Liberal caucus, noting that I had rejected the option of remaining in cabinet, of “hanging on by my fingernails,” in which case, “staying in cabinet becomes an end in itself, rather than the vehicle by which to do certain things.”

To the prime minister and cabinet, the MPs and senators—in all, about 200 politicians—I said, “My decision to resign was an important one, yes, wrenching in its implications for me and others. But it was not an especially difficult decision. . . . I believe I did the right thing in the circumstances, just as I believe I did the right thing ten days previously in accepting the prime minister’s kind invitation to join his cabinet.”

Media circus

The requisite news release disclosing my resignation went out from the PMO on August 22. My departure from cabinet so soon after being appointed could be expected to set off a brief media feeding frenzy. I believed the news would be nothing more than an overnight wonder. The days ahead would thrash that assessment as the press drilled down, determined to get the story behind the story. Five days after the news broke, an Ottawa daily ran in its weekend edition no fewer than ten stories related to the resignation, ranging from the results of a national poll, to reaction from constituents, past and present, to a detailed profile on “Simmons, a private man who chose a public life.”158

Shortly before the resignation became public, my good friend Herb Metcalf and I holed up in a downtown hotel, monitoring the press until the news cycle had run its course. Before doing so, I instructed my staff to phone about twenty people, my family members, close friends, colleagues, and key supporters, before the story hit the airwaves and to pass on a carefully worded message: “Roger has asked me to call you to say that you can expect some news in the next couple of hours. He suggests that the nature of the news will be such that you may want to go somewhere with a radio or TV and collect your thoughts before talking to anyone.”

Why did my resignation receive such saturation press coverage? The best explanation is that it was the height of Ottawa’s silly season, the lazy days of late August. Media scribes couldn’t find something more substantive to write about. The press needed a story, any story. The job of the press wasn’t made any easier by the advice I had received from lawyers not to divulge the reason for my departure from cabinet. But, here again, the accommodating folks at RevCan were more than willing to lend a hand with a well-timed press leak. They were breaking the law, of course. But that wouldn’t have bothered a bunch of zealots who believe they are a law unto themselves.

“A law is only as good as those who enforce it,” I told the House of Commons on September 12. “I can only express the hope that the ‘highly placed government source’ who discussed my private tax affairs in public has a more competent, less malicious understanding of his other responsibilities and of the legal parameters within which he is supposed to operate.”

Ottawa, 1983. With Prime Minister Pierre Trudeau. (J. M. Carisse photo)

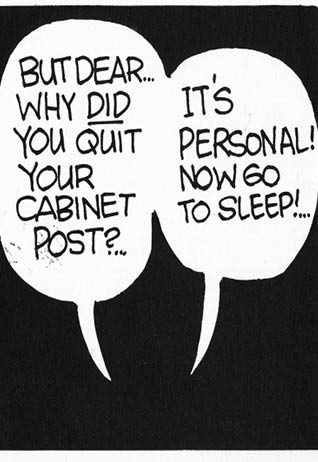

My lawyers advised me not to disclose the reason for my cabinet resignation. This cartoon by Jim Phillips ran in the Toronto Sun daily newspaper on August 29, 1983. (Author photo)

The press kept probing my psyche. Was I angry? Sad? Embarrassed? No, I was focused. One of my redeeming traits is that I do not panic under pressure. As reporter Greg Weston noted,

“The only time this week that Simmons publicly showed any signs of anger was in a face-to-face confrontation with a Citizen reporter. . . . He wasn’t mad that the paper had broken the story. . . . He was angry that a reporter had knocked on the door of his home. . . . That, he claimed, was ‘harassment’ of his wife, Miriam.”159

The Citizen reporter was none other than Weston himself. Ironically, at the very time his journalistic instincts were making life miserable for me, I gained a grudging admiration for him. He could have skewered me in the article. Instead, he showed self-discipline and integrity, two must attributes of any good news reporter.

I’ve never shied away from a reporter who knows how to get the story right. As a former journalist myself, I couldn’t help but applaud Weston’s diligence in chasing down the story, but I did feel he crossed the line when he came to my suburban Ottawa residence, in the process inflicting unwarranted trauma on an innocent party, my wife.

A man’s home is his castle, and the uninvited should not breach the moat unless the castle’s occupants are in imminent physical danger or it conceals evidence of illegality. Neither applied in my circumstance, as the journalist well knew. In the years since then, I have been delighted to watch Weston blossom as a respected scribe. Arguably, he learned a helpful lesson from his misstep that August night.

While the sheer volume of media coverage was excessive, I had little reason to complain about the substance of the reporting. With a few glaring exceptions, including the one mentioned above, the press handled the issue with the persistence and responsibility which ought always to be its trademark.

Notwithstanding, mainstream media has been known to indulge in tabloid journalism to hype a story. In the days following my cabinet resignation, there were two CBC TV reports where sensation trumped the facts. The anchor conjectured that my failure to report $28,000 income on my tax returns could net a jail term of ”up to ten years,” a preposterous fabrication which fuelled a barrage of frenetic phone calls from family and friends who assumed the network knew what it was talking about.

And, in a story aired on the night of August 23, CBC declared my office was shuttered and I was nowhere to be found. That was a barefaced lie. The public network had merely resorted to one of the oldest journalistic tricks in the book: If you can’t get the facts, make ’em up, improvise, run with something that sounds plausible. Apart from those incidents, I’ve not had any scores to settle with the media, including the CBC.

Except for four hours immediately following the resignation announcement, I was on Parliament Hill and, for the most part, in my office every day during the week of August 22 and was regularly intercepted by members of the media as I moved between meetings. Indeed, one commentator suggested that I was too available to the press, that I was somehow enjoying the whole media circus. While it wasn’t a particularly fun experience, I didn’t see the need to skulk about like a fugitive. If reporters were determined to keep asking the same questions, I was not averse to giving them the same answers.

Picking up the pieces

My conveyor belt odyssey in cabinet behind me, I turned my focus to charting the uncertain course ahead. I wasn’t yet aware whether Justice would lay charges against me, but I had to be ready just in case. More immediate, it was imperative that every conceivable angle be explored to see if the matter could be put to bed by an appropriate approach to RevCan. It was with that objective in mind that I engaged the services of a top-notch tax lawyer.

A year or so earlier, I had addressed the Law Society of Upper Canada160 at the behest of its treasurer161 and Allan Lutfy162, the PM’s in-house legal counsel. It was Lutfy who, on hearing of RevCan’s reversal, gave me the legal advice I needed: Get the best tax lawyer in the country, he exhorted. And I did, again thanks to Allan.

Heward Stikeman, co-founder of the highly respected law firm of Stikeman Elliott, had all the right credentials. He had been deputy minister at RevCan, had authored the definitive bible on Canadian tax law, and was a friend and former colleague of several senior RevCan personnel. I tracked down Stikeman by phone the day after my resignation, and I met him five days later at his summer getaway at Rideau Ferry, just over an hour’s drive from Ottawa. His opening words were, “Before you even called me, I saw you on the TV and I thought, ‘That guy’s got a tax problem!’”

We spent the next three hours together. I talked. He listened, posed questions, and cross-examined. He scrutinized the documents I had brought. Then, he stood, extended his hand, looked me in the eye, and said, “I believe you! Absolutely, and without qualification!”

Two days later, on August 30, Stikeman came to Ottawa to meet with a senior RevCan official, then with me. His account of the meeting with the official confirmed what I already knew to be the case. He quoted the official as saying, “Don’t worry about it. Obviously there’s been a monumental screw-up here.”

Within twenty-four hours, Stikeman was summoned back to RevCan to receive a very different message. Here again is my lawyer’s account of what the official told him:

“Simmons’s investigation was complete. A decision had been made to assess a penalty and close the file. However, when your man went into cabinet, we had a problem, a—uh—perception problem. How could we ever explain that the file had been taken off the desk before he became a minister? So, we decided to put the file back on the desk. We solved our problem. Now, it’s his problem.”

In a further meeting, sometime during the week of September 5, between the two men, the official told my lawyer that, “If this thing goes to court, it will be thrown out the same day.”

If Stikeman was a believer after our first encounter, by our third get-together he had become my champion. He was deeply offended by RevCan’s about-face and spoke repeatedly of the official’s duplicity as a betrayal of their long friendship.

Skipper, my dad, was always good for a story, usually one that was true and had an unexpected twist, like the following. A father and his three grown sons worked as a unit harvesting logs for the paper mill. Early one morning a freak accident took the life of the eldest son. Not surprisingly, the two devastated brothers assumed the tragic turn of events meant an immediate cessation of their logging. The father had other ideas. He commanded them to lay out their brother on the log pile. Then, he addressed the lifeless body of his firstborn: “Jim, my son, you’re gone. Taking you home now won’t bring you back. And would you want us to lose a day’s pay?”

Whereupon the father picked up his bucksaw and tackled another tree. Two flabbergasted siblings took the hint. The deceased had to await the end of the work day for his last ride home!

There are times when the practical thing to do is definitely not the appropriate course of action. From RevCan’s perspective, the practical solution was to “put the file back on the desk,” while turning a blind eye to the gross indecency of its action.

Seismic blunder

The absence of the Clerk of the Privy Council from Ottawa at the time of the August 12 cabinet shuffle was the pivotal element in my dramatic reversal of fortunes. Long-standing practice and common sense dictate that, before the prime minister invites someone to join the cabinet, the Clerk initiates a thorough screening of the candidate to ensure the candidate has no legal, financial, or other skeletons in the closet. It was that certainty which underpinned my assurances to my wife during our conversation the night before the cabinet shuffle. Astoundingly, in Gordon Osbaldeston’s absence, no such screening was done. None of the four ministers who joined the cabinet that day had been vetted163.

Consider what would have transpired if the requisite screening of prospective cabinet members had been undertaken. Simple logic dictates that there could have been two, and only two, possible outcomes insofar as my screening was concerned. Either charges were pending—a finding which would have eliminated me from cabinet consideration—or there was nothing to abort my cabinet candidacy, confirming, de facto, that there was no intention to lay charges, which was in fact the case.

That’s what I was told on June 20. And that syncs with Stikeman’s account of his August 30 meeting with the senior RevCan official and, specifically, the latter’s statement that the file was “off the desk.” That finding would have been the green light for the PM to invite me into the cabinet and, crucially, would not have allowed RevCan to “put the file back on the desk” as the official confessed to Stikeman during their August 31 meeting.

Either of the two possible findings would have saved the public purse several hundreds of thousands of dollars and spared me and my family from astronomical legal bills and unjustified humiliation.

In hindsight, I should have raised the issue with the PM in our morning meeting on August 12. That retrospective is not a new insight. I realized my error the moment I learned that RevCan had, in the official’s words, “put the file back on the desk” and the reason for doing so. Despite my disgust at the ruthlessness of RevCan during the fishermen’s audit, I could not have fathomed it could stoop to the kind of treachery acknowledged by the official in his August 31 meeting with Stikeman.

“A friend in need is a friend indeed”164

From the time of Osbaldeston’s August 18 call to me until Stikeman reported to me on his second (August 31) meeting with RevCan, I remained optimistic that the matter could be resolved quickly. That frame of mind and my belief in the rightness of my decision to resign kept me buoyant. That second Stikeman meeting with the agency changed everything.

Reeling from RevCan’s kick in the guts, I needed to talk to someone who could make some sense of what was happening. A one-on-one chat with my good friend David Smith was just the therapy required. So, off to Toronto I went.

A crackerjack corporate lawyer and a former deputy mayor of Toronto, Smith was the MP for Don Valley East. At the very first post-election caucus get-together in 1980, as I took my turn telling the bartender my beverage choice, a voice over my shoulder inquired: “Salvation Army or Pentecost?”

Overhearing my request for a Diet Sprite, David Smith had deduced I must be a teetotalling evangelical. And so began my enduring friendship with an amazing guy. David comes by his knowledge of Pentecostalism first-hand, his dad having been the elected head of the Pentecostal Assemblies of Canada for seven years and served another seven as president of its seminary at Peterborough, Ontario. David’s impressively large collection of Salvation Army brass band and choral recordings attests to his affinity for the Army, and they routinely fill the air during my visits to his den.

Heather Smith is, like her husband, David, a delightful host and a loyal friend. A long-time judge of Ontario’s Superior Court165, she is a woman of flawless circumspection with a practised ease at staying above the fray. David and Heather Smith’s cozy nest in Forest Hill became my port in the storm where empathy, advice, and a willing ear worked miracles in sharpening my focus for the battles ahead.

Taking it on the chin

The phone call I was most dreading came soon after my resignation from cabinet became public. Don Jamieson was among the close friends my staff had called. Serving as Canada’s high commissioner to Britain, he was back in Newfoundland on vacation and wasted no time in tracking me down. I was right to be apprehensive, but for the wrong reason. I was fully expecting a stern dressing-down for the sequence of events which culminated in my resignation. Instead, he threw me a curve, though the surprise was no less painful:

“Resignation! That’s the last thing you should’ve done. Stupidity personified! Why didn’t you call me before you committed suicide? It’s a whole lot easier to keep the lid on than to put the genie back in the bottle. You’ve played into their hands. Now that bunch of reprobates in Revenue has all the cards. Your goose is cooked!”

Cooked or not, Jamieson insisted I come to see him without delay, which I did ten days later. The eyeball-to-eyeball reprise of his telephone rant was no more palatable. After unloading on me at length, he turned his attention to a review of the facts and next steps. Like Trudeau and Stikeman, Jamieson was incredulous when I told him the details of my tax case. He insisted there had to be more to it, that I was holding back something.

“No one gets dragged into court for five thousand dollars in unpaid taxes. No one quits cabinet over such miniscule piffle. What are you not telling me?”

He chewed me out royally. I told him of the PCO oversight in not screening the candidates for cabinet and of Stikeman’s two meetings with RevCan. Jamieson exploded yet again.

“Those nefarious, low-life, self-serving, cowardly gangsters in Revenue. Your cabinet appointment gave them an opening. By quitting, you handed them your head on a platter!”

In full flight now, his renowned broadcaster’s cadence kicked in as he paced the floor, repeatedly slashing the air for emphasis. Then, slumping into his favourite recliner, he went silent, except for asking me to turn up the volume on the stereo. “Louder! Put her up on blast!” The deafening roar of Sir Edward Elgar’s “Pomp and Circumstance” transformed the room and Jamieson. I knew from previous visits that gorging on ear-splitting music, often the very piece now playing, was how he recharged his batteries and pondered tough issues. At long last, he spoke, quoting the lyrics behind the music:

“‘Thine equal laws, by freedom gained, have ruled thee well.’ It was stupid politicians, lawmakers, like us who gave these charlatans the noose. Now, let’s see if we can get it off your neck. There’s got to be a way to get you out of this mess.”

Matter-of-factly, Jamieson canvassed the facts of my case, drilled me some more, and spelled out likely scenarios. I came away from that unforgettable, marathon evening with many ideas, angles, and options to put to my lawyer. More importantly, Don did me an invaluable service by succinctly mapping out a way forward and steeling my resolve. In subsequent phone calls and visits, his broad shoulders and wise counsel were a key source of strength in the rough weeks and months which followed166.

Decades later, to hear “Pomp and Circumstance” is to fondly remember a larger-than-life, blunt-talking, astute friend, Don Jamieson.

Lowering the boom

Immediately after his second RevCan meeting, Stikeman told me he had no doubt that my tax file would wind up in court:

“This is now so high-profile. They have to charge you to sustain their tough-guy image, to show the public that not even a prominent politician can get away with trying to beat the taxman, as they allege you’ve done. You are now RevCan’s poster boy.”

Therein lay the essence of Don Jamieson’s reason for maintaining I should not have quit cabinet. My action had introduced a public dimension, allowing RevCan to take advantage of the changed circumstance. I believe that, whether I had remained in cabinet or not, the agency would have ensured that my case became widely known. In the lingo of computerese shorthand, there’s an app for that. It’s called a RevCan press leak, illegal167 but effective. The income tax moguls are its past masters.

Stikeman’s prediction came true within days. It’s rare to find an MP on Parliament Hill when the House is in recess. Nonetheless, my continuing preoccupation with two issues, fisheries and my tax case, kept me late at the office on most days. Friday, September 9, was such a day. At 6:40 p.m., the phone rang. It was RevCan’s deputy minister, Doug Rutherford. Justice would be laying charges on Tuesday, he told me.

RevCan’s public version of events was that it recommended to Justice on July 24 that charges be laid. That doesn’t square with, indeed directly contradicts, what the official told Heward Stikeman during their meetings on August 30 and 31. Nor does the July 24 date make sense in the context of what Osbaldeston told me during our August 22 meeting. He had been informed by RevCan on August 18 that a decision to prosecute had not been made.

It’s also intriguing to note that, if the recommendation to prosecute was indeed made on July 24, the failure of the Privy Council Office to screen cabinet candidates prior to the August 22 shuffle was an omission of monumental significance.

What, then, caused RevCan to change its mind between June 20 and August 18, the day that Osbaldeston was informed of my tax issue? The answer is simple, and it’s right from the horse’s mouth. The RevCan official told Stikeman on August 31 that, “When your man went into cabinet, we had a problem.”

We also know when RevCan changed its mind or, perhaps more correctly, when the official became aware of his department’s new stratagem. It had to be sometime subsequent to the August 30 (first) meeting between the official and my lawyer.

What is crystal clear is that RevCan changed its mind because of one piece of new information, and one piece only: I had become a cabinet minister. That had the potential to create an awkward public perception problem for the tax agency. In the official’s own words, “How could we ever explain that the file had been taken off the desk before he became a minister?”

RevCan had a solution to the problem. Make it my problem, which it did immediately and in spades.

Gentle giant

Heward Stikeman was nearing the end of a brilliant career when he immersed himself in my troubles. I owe him a great debt for his helpful advice and, especially, his unwavering belief in me and my cause. He counselled me through six meetings and numerous phone consultations. He travelled three times to Ottawa from Rideau Ferry and once to Montreal on my behalf.

Having long since quit the courtroom, Stikeman arranged for John Sopinka, a partner in Stikeman Elliott’s Toronto office, to spearhead my defence. Catherine Chalmers, Sopinka’s Toronto colleague, joined the defence team, as did my long-time friend, St. John’s lawyer Norm Whalen.

Stikeman, Sopinka, and I met in Montreal on September 15. It was immediately obvious that Sopinka enjoyed both a cordial relationship with Stikeman and his complete confidence. That trust was clearly not misplaced: Just five years after Sopinka acted for me, he was named to the Supreme Court of Canada. He died much too soon in 1997.

When the time came to settle up with Stikeman, he refused to take a dime. “This one’s on me. Besides, someone has to keep an eye on that gang.” Stikeman was certainly right about that. He passed away in 1999. I hadn’t had the opportunity to reconnect with him for several years. The last time we spoke, RevCan’s betrayal of him, and me, was still a raw wound for both of us. Ten years after his passing, a tribute in the Globe and Mail saluted “his gentleness, intellect, zany wit, and single-mindedness of purpose.” Dr. Glenn D. Feltham, former tax law professor and president of the Northern Alberta Institute of Technology, said of Stikeman, “No individual has had a more profound effect on the development of tax in Canada.”

Once, twice, maybe three times in a lifetime, you get to know a truly great human being. Heward Stikeman fit the bill to a T.

Given my long involvement in Newfoundland education and politics and the resulting high profile, the challenge for the St. John’s court administration was to assign a judge to my case who didn’t know me personally. The choice of Judge John Trahey was ominous. The following day, I ran into Gord Seabright, a close friend dating back to my Springdale days and an imposing, flamboyant character with a verbal bluntness that could shatter windowpanes. Seabright, like Trahey a provincial court judge, took me aside at a reception. His candid assessment of Trahey’s new assignment was far from reassuring: “Yesterday was not your lucky day! Trahey’s notion of consistency is ‘Convict all of ’em!’ Once in a blue moon, he acquits—just to keep his batting average respectable!”

The other shoe dropped when I learned that RevCan had fingered superstar lawyer Clyde Wells to prosecute my case. Up until then, I had enjoyed a friendly relationship with Wells stretching back nearly two decades to our Young Liberal days. Indeed, he had acted for me in a real estate transaction some years earlier.

Clyde had a well-deserved public persona as a successful lawyer and as a guy to watch. Joey Smallwood had recruited him at age twenty-eight to join the provincial cabinet. As Joey soon learned to his sorrow, his new Labour minister was, to quote British Prime Minister Margaret Thatcher’s descriptive self-assessment, “not for turning.” Brian Mulroney and all of Canada would learn the same lesson during the Meech Lake shemozzle. Wells’s stick-to-it-iveness on any position he espouses is legendary. Compromise and flexibility do not figure prominently in his vocabulary or way of operating.

Recalling our past association as political fellow-travellers and friends, I was understandably taken aback at the news of Clyde’s impending role in my case, as were some of his law colleagues—though I understood that, from his perspective, this latest assignment was all in a day’s work for a lawyer with his credentials.

Encouraging signs

With the court proceeding set to get under way on October 24, 1983, I had reason to be optimistic. I had the best legal team I could have wished for. I felt there was no substantive case against me.

John Sopinka asked me to indicate my preferences for character witnesses. Several friends and former work colleagues had already come forward offering to take the stand on my behalf. I chose Clarence Wiseman and Don Batstone, both of them men of sterling character and reputation. General Clarence Wiseman, my fellow Newfoundlander and long-time role model, mentor, and friend, had been worldwide head of the Salvation Army (1974–77). He flew in from Toronto for the court hearing. Don Batstone, my former school board chairman in Green Bay, had recently retired from a distinguished career in RCMP counter-intelligence. Both knew me well, both had plenty of experience doing character assessments, and their long public service careers ensured they wouldn’t be intimidated by the vagaries of the court process or wilt under the pressure of a baiting prosecutor.

I was buoyed by the fact that the prime minister had not filled the cabinet vacancy created by my resignation, which I interpreted as tangible evidence both of his confidence in me and his resolve not to prejudice the outcome of my legal battle. I was also encouraged by several conversations I had with the PM, often sitting beside him in the Commons chamber, while my tax problem wended its way through the court.

My spirits were certainly lifted by the many dozens of phone calls, countless one-on-one conversations, and hundreds of letters and telegrams from friends and strangers alike. Here’s a sampling:

“I continue to be a strong admirer and friend.”

— Future senator Michael Kirby, Montreal, August 24

“Those of us who know you will miss the enthusiasm

you could have brought to the cabinet table.”

— Senior advisor to federal cabinet minister

John Roberts, Ottawa, August 25

“May strength, quietness of spirit, and deep inner peace be with you.”

— Clergywoman and former university colleague, Toronto, August 29

“I will always remember . . . the night of the 22nd. All around you might have been going bad, but you stressed the importance of looking only to the future.”

— Ever so briefly, my ministerial chauffeur, August 30

“The widespread support is a tribute to your ability and integrity.”

— Future colleague and prime minister, Paul Martin, Montreal, September 9

“Our priest asked the congregation to write you urging you to be strong.”

— Joan White, constituent and ex-member

of my House of Assembly staff, October 3

“Claire and I . . . want you to know that we hope you have

the strength to overcome these difficulties.”

— Lily Shreyer, Rideau Hall, Ottawa, October 10

The caring, handwritten note from Her Excellency was especially appreciated. It had been my pleasure, three months earlier, to spend several days aboard a Coast Guard ship with Governor General Ed Shreyer and his wife. Authors Farley and Claire Mowat, close friends of the Shreyers, also made the trip.

The incoming mail wasn’t all pleasant to read. My circumstance, both before and after the court’s decision, unleashed a small torrent of abuse, ridicule, and hatred, impugning everything from my party affiliation to my morals to my sanity.

As matters took their course in the provincial courthouse in St. John’s, it became ever more obvious that the case mounted against me, aided by the interventions and body language of the presiding judge, would be deciding factors, not what I knew to be the truth. Wells, skilled courtroom performer that he was, played Judge Trahey like a compliant fiddle. Even the come-from-away domicile of my two Toronto lawyers was fair game as they were repeatedly admonished with “That’s not how we do things here’ put-downs.

Throughout the four-day proceeding, I was rarely ill at ease or frustrated; focused and engaged, yes, but not panicky or distraught. My defence team did a superb job of presenting our case, refuting prosecution claims and blunting surprises from the other side.

With the benefit of hindsight, limitless moments of reflection, and lots of Monday morning quarterbacking, I do second-guess my defence team in one respect. The entire thrust of its strategy was centred on the issue of wilfulness on which the Justice charge was predicated. The vendetta which, I believe, was at the heart of RevCan’s audit and investigation of my tax file, and the agency’s duplicity in putting the file “back on the desk,” were not canvassed during the court proceeding. In particular, sworn testimony by the iconic Stikeman concerning the substance of his meetings with RevCan would have been persuasive evidence of the tax agency’s real agenda.

As well, my lawyers and I were not aware, at the time of the court proceeding, that there was a key relationship between one of the RevCan investigators and Alex Walsh, the businessman serving prison time for his role in the Newfoundland Public Works spending scandal which I had exposed as chair of the Public Accounts Committee.

If you can bear to hear the truth you’ve spoken twisted by knaves . . .168

My blood pressure shot up when the two investigators’ recounting of what transpired during our several meetings bore little resemblance to the facts. Their charge that I had been reticent in admitting I had received the unreported income was a complete fabrication, a blatant lie, tailored to shore up their claim that I had deliberately failed to report this income. As soon as I was made aware of the income and its source, I immediately indicated the approximate sums I had received.

I had seen no need to have someone in those meetings with me who could later attest to the truth or otherwise of what was said. Indeed, I naively thought that would have been interpreted as an admission of guilt.

As a takeaway from my ordeal, I maintain that good tax law should stipulate that, in any such meeting during which evidence is sought which may be subsequently used in a prosecution, the taxpayer should be required to have a lawyer or other corroborating witness in attendance. Conversely, the statute should provide that evidence obtained in a meeting where no such witness is present is inadmissible in prosecuting a case.

In the absence of such protection from unscrupulous fishing expeditions, I was a lamb to the slaughter. It was my word against that of two others, not exactly a balanced formula for establishing truth, particularly if they have an agenda and are seeking to advance it. I believe the outcome of my case would have been quite different had I been able to rely on a witness who could affirm that significant elements of what the investigators alleged didn’t square with the facts. The truth shall set you free is a good guidepost. In my case, though, the more I told the truth, the deeper I dug the hole because my interrogators cherry-picked the facts that suited their narrative.

A case in point and the final irony is the following: In addition to the $28,000 in the court documents, I had other unreported income during the same years. And I told the tax investigators about it. Dozens of forty-foot accommodation trailers had become surplus to housing requirements in Churchill Falls, Labrador. I bought ten of them and had them shipped, at considerable cost, to my Kona Beach property, forty miles north of Grand Falls, Newfoundland. I sold two of them, but the others were rendered unusable in a severe windstorm. The sales revenue was dwarfed by the financial bath I took on the damaged units.

The tax investigators informed me they had decided not to factor the trailer income and expenses into their reassessment of my returns. At the time, I thought they were doing me a favour. Their real motive was something far less helpful. My losses in the trailer affair essentially offset the unreported income to which I had already admitted. As well, my failure to claim these losses buttressed my explanation of negligence while undermining the investigators’ thesis of wilful tax avoidance. How could they argue that I was out to beat the system if I had not seen fit to claim offsetting expenses?

At the conclusion of the four-day proceeding, Judge Trahey reserved judgment, ultimately handing down his decision a week later. He ruled for the prosecution, and I was fined $3,500.

It goes without saying that my biggest faux pas was neglecting to report the $28,000 income on my annual tax returns. But it was other naive mistakes I made subsequently which helped to seal my fate. Meeting with the two investigators, in the absence of a corroborating witness, was, without a doubt, my second biggest blunder.

My case set a precedent as the smallest in dollar value of unreported income ever to be prosecuted169. All others of similar or less size have been mitigated by assessing a financial penalty, including cases where there was clear evidence of a wilful act of tax evasion.

Stamping out ruthless fishing expeditions

It is not hard to draw the conclusion that my income tax ordeal was less about compliance than about good old-fashioned payback. I don’t have a martyr complex. I am not a likely candidate for self-immolation. But if a guy is towering over me swinging a baseball bat toward my head, I know he’s not here to play ball with me. Whether or not a second vendetta, fuelled by my role in unearthing the Newfoundland Public Works scandal, added to my troubles, others will have to decide.

An arm of government should not have the licence to purposely inflict misery on its citizens. Yet that is the daily option of the Canada Revenue Agency, and, in my experience both as a taxpaying citizen and a veteran politician, I can attest that it is all too often the agency’s way of carrying out its business.

It is not bureaucrats as a whole who are at fault, though if duplicity and malevolence are communicable diseases, RevCan/CRA has infected a whole generation of well-intended public servants. The real culprit is the system itself. In Canada, as in other jurisdictions, the imperative to ensure that no one is above the law has, irony of ironies, unwittingly spawned a horde of bureaucrats who are not only beyond the reach of the law, they get to de facto rewrite the law to suit their warped agenda and to rewrite it yet again as that agenda changes.

The challenge for duly elected lawmakers, not the self-appointed legislative drafters in tax agencies, is Olympian. Whether in Canada or elsewhere, the impossible task is to put the genie back into the bottle, to craft a tax law enforcement regime which achieves its legitimate purpose, while thwarting unscrupulous zealots who self-righteously rank their misguided mission above any consideration of the real intent of the legislation. The tragic result is the unjustifiable and continuing harassment, yea, the ruin, of law-abiding taxpayers such as the fishermen who were vilified in the 1982 audit, such as BC’s Irvin LeRoux and untold thousands of others.

What’s needed is a tax law enforcement arbiter. Oh, I’m aware that Canada already has an income tax ombudsman. However, that office is mere window dressing; it has no power, no teeth. The ombudsman’s involvement is after the fact. What I propose is an arbiter who is a parliamentary, not a government, appointee and whose decisions are binding. Tax agency stratagems would have to pass muster with the arbiter to guard against mindless, malevolent fishing expeditions and unethical ploys by tax investigators to cover their tracks when some diabolical scheme blows up in their faces. A tax arbiter may not have saved my seat at the cabinet table. But an arbiter would, at the very least, rein in the ruthless excesses which are the stock-in-trade of CRA.

Retrospective

Every cloud has a silver lining, even an ominous monstrosity that blocks the sun and darkens the sky. That is an apt metaphor for my tax troubles. And yes, believe it or not, I have found the silver lining, again and again. My doctoral-level seminar in personal financial management, treachery, and kneecapping has reaped untold dividends. I believe I am a better person, more organized, less procrastinating, certainly less trusting, more alert to demented con artists who think that making life miserable for law-abiding citizens is an honourable way to earn a paycheque.

And I now know who my friends are.

News of the court decision unleashed yet another flood of mail, telegrams, phone calls, and one-on-one conversations. The outpouring of empathy and support was overwhelming and uplifting. From all walks of life, from every corner of the nation, expressions of support poured in.

Not that all of the mail was reassuring or pleasant to read. Partisans of other party stripes, armchair experts, self-appointed executioners, and, in a few cases, certifiable hate-mongers and sickos all took their pound of flesh at my expense.

The option to appeal Judge Trahey’s finding was, of course, open to me. After consultations with friends and tax lawyers, I reluctantly decided against launching an appeal. The overriding reason was financial. To date, I had racked up legal bills of more than $70,000, and I was effectively bankrupt. The appeal, I was told, could double my indebtedness. In reality, there was no decision to make. I just didn’t have the money.

I’ve recently reviewed my entire file on the tax issue, including the hundreds of letters, first of congratulation, then of condolence, support, puzzlement, ridicule, and judgment that my cabinet appointment and its aftermath spawned. My abiding reaction is just how completely I let so many people down by my carelessness. I shall go to my grave lamenting the pain and the dashed hopes I inflicted on others by my inattention to my personal affairs and the havoc it caused.

In January 1984, soon after I had forfeited my right to appeal, the PM reappointed my predecessor, colleague and lifelong friend Bill Rompkey, as Newfoundland and Labrador’s representative in the federal cabinet. Bill’s outstanding political career spanned nearly forty years as an MP, minister, and senator, a position he held until his 2011 retirement. What a wonderful guy! His humanity and bonhomie touched many lives. Sadly, Bill passed away in early 2017. We miss him dearly.

The voters weigh in

Prime Minister John Turner convened his first caucus the day after assuming the Liberal leadership in 1984. He canvassed the views of members on the timing of an election call. With the Liberals leading by ten points in the polls, should he opt for an immediate trip to the ballot box or delay a few weeks until he could put his own imprint on the government? I was among those who favoured the latter option and said so. Then, I added, “However, if you decide to pull the plug now, don’t worry about me. If I lose my seat, you won’t get forty.” Turner opted to pull the plug. I lost my seat, and we got forty!

My narrow defeat in the 1984 federal general election was the first following my public mauling at the hands of RevCan. It is unclear to what extent the tax issue was a factor. The election night figures placed me just one per cent or 299 votes behind the victor while holding most of my support from the previous election, when the final count had ranked me among the top five vote-getters nationally. Across the country, my party lost sixteen per cent of the popular vote in 1984 compared to the 1980 election results and dropped from 147 to 40, a staggering 107 seats. Forced to choose between Brian Mulroney’s liberal Tories and the Liberal Party’s toryism, voters across Canada opted for hope over exhaustion. My narrow defeat appears to have been part of a referendum on the national Liberal brand.

The income tax issue may well have helped my campaign. My constituents were well aware of its essential elements, including the tax agency’s unprecedented decision to prosecute such a low-dollar case. They were equally cognizant of my aggressive role concerning the fishermen’s audit, and many of them saw linkage between the two matters. Further, thousands of fishermen who had been mercilessly run into the ground by their RevCan audits and their families had an axe to grind with the agency. My axe became their axe. Often, during the campaign, I was told by electors that their reason for supporting me was directly related to what RevCan had done to them—and to me.

Discharged by the electorate and out of politics for the first time in more than a decade, I looked for other opportunities and quickly found one, or, more accurately, it found me. As one door closes, another opens is a creed I live by. The glass is always half full.

156 In June 2017, the building was renamed the Office of the Prime Minister and Privy Council.

157 House of Commons Debates, September 12, 1983

158 Ottawa Citizen, August 27, 1983

159 Ibid

160 Renamed as the Law Society of Ontario by its governing body in November 2017

161 An organization usually refers to its head honcho as chairman or president. Not so with the lawyers! Their top dog is the guy/gal who holds the purse strings! Who said lawyers aren’t smart?

162 He was appointed as a federal court judge in 1996, where he served for fifteen years, eight as chief justice.

163 Prime Minister Trudeau later confirmed that the standard security check was not done prior to the August 12 cabinet shuffle. (Canadian Press, September 15, 1983)

164 Quintus Ennius, Roman poet, dramatist, and satirist, 239 BC–169 BC

165 Madam Justice Heather Forster Smith began her legal career as a Crown prosecutor with the federal Department of Justice. She is the current Chief Justice of the Ontario Superior Court of Justice, having been appointed to that position in 2002.

166 As we say in Newfoundland, Jamieson was no slouch at speaking his mind, peppering every phrase with colourful descriptors, some of them printable. Anyone who knew him will recognize that I have sanitized or omitted his more graphic characterizations. Otherwise, the above quotes reflect the tone and essence of his utterances and are extracted from notes I made during and immediately after our session.

167 “CRA (RevCan) officials are forbidden by law from discussing the filings of individual taxpayers.” – Globe and Mail, October 31, 2007; updated March 27, 2017

168 Rudyard Kipling, English journalist, poet, and novelist, 1865–1936

169 Clyde Wells: A Political Biography, Claire Hoy, Stoddart Publishing, Toronto, 1992, p. 122