Tribune: An officer of ancient Rome elected by the plebeians to protect their rights from arbitrary acts of the patrician magistrates; a protector or champion of the people.

— TheFreeDictionary

The year 1988 marked my fifteenth in elective politics, ten in the Newfoundland House of Assembly and five in the House of Commons. Each arena had given me many satisfying moments, wrenching heartbreaks, and lasting memories. Having tasted national politics, that’s where my preference lay, and I was determined to get back to the House of Commons at the first opportunity. By mid-1988, it was widely assumed that Prime Minister Mulroney would go to the polls before the year was out.

To have a shot at once again becoming the honourable Member for Burin–St. George’s, I first had to win the Liberal nomination, which I fully expected would be contested, as indeed it was. In American parlance, I had to survive the primary. That was going to take some fancy stickhandling and hard work. I was ready for both.

For months before the party nomination process was set in motion, I carried in my pocket a copy of the Liberal Party’s official nomination form and invited voters to sign it. The party rules required twenty-five signatures. I secured 3,000. These included a healthy majority of party activists and community leaders.

By the time my opponent declared his intentions, I effectively had the nomination sewn up. Even his closest friends, who would have certainly been in his camp had they known earlier of his planned candidacy, were telling him instead, “Sorry, but I already gave my word to Roger.”

Yon Cassius has a mean and hungry look179

With the nomination in the bag, there was one more hurdle, though at the time I regarded it as a mere formality. The Canada Elections Act stipulates that a candidate running under the banner of a political party needs a letter of endorsement signed by the party’s leader in order to have the party’s name appear on the ballot. I had won the Liberal nomination fair and square, so how could there be a problem? Simply put, an incumbent Newfoundland MP, and a Liberal one at that, didn’t relish the notion of my returning to Parliament. Indeed, I was already aware that he had raised thousands of dollars to underwrite the campaign costs of my nomination opponent. When that investment didn’t yield the hoped-for return, the MP bent the leader’s ear, invoking my income tax problem, which had been put to bed five years earlier, to try and persuade John Turner not to sign my nomination.

Shortly after the 1988 election, Turner hosted the caucus at a reception at Stornaway180 and invited me to hang back for a one-on-one chat. He was in a talkative mood. He told me of the abortive attempt to prevent me from running as an official Liberal candidate and gave me some advice: “Watch your back.”

Turner referenced the caucus revolt against his leadership a few months before the 1988 election, telling me that the dissidents had been plotting their mutiny when one of their number slipped out of the meeting. It was the same MP who had tried to trip me up. Turner told me, “(He) came to my office. He pretended to be on my side, speaking of the seventeen conspirators as ‘they,’ trying to give the impression he wasn’t one of them. Of course, he was just covering all his bases. There are snakes in the grass around here, lots of them.” Indeed, the landscape was even more infested than Turner realized. Eventually, letters demanding his resignation were signed by twenty-two of the thirty-eight members of his caucus.181

The 1988 federal vote has become known as the free trade election. Prime Minister Mulroney had signed a free trade agreement (FTA) with the US in January 1988. In so doing, he had done a complete about-face. During the 1983 Conservative leadership campaign, Mulroney ranted forcefully against “opening the floodgates”182 when leadership contender John Crosbie spoke in favour of such an agreement. Mulroney pontificated, “Free trade affects Canadian sovereignty and we will have none of it, not during leadership campaigns or any other time.”183

However, when the MacDonald Royal Commission, appointed by Pierre Trudeau, recommended in 1984 that the government pursue a free trade agreement with the United States, Mulroney—having succeeded Trudeau as PM—embraced the idea. During the 1988 election, the Liberal Party campaigned against the bilateral pact. Protecting Canadian sovereignty became our messianic mantra, our cause célèbre.

We warned of subjugation by the behemoth on our southern flank. In so doing, we were mounting the very arguments Mulroney had employed against Crosbie.

At an all-candidates rally in Stephenville, I finished my speech, the final one of the evening, with a confident prediction of Liberal vindication at the polls. Then, I strolled over to the onstage piano. “In the unlikely event we lose the election, get used to this.” The first six notes of “The Star-Spangled Banner” filled the hall. The crowd loved it. It became the coda of several subsequent speeches, usually with similar effect. I’m not saying my less-than-melodic tickling of the ivories did the trick, but I won the 1988 election with a thousand votes to spare:

Joseph Edwards, New Democratic, 2,299

Joe Price (incumbent), Progressive Conservative, 17,488

Roger Simmons, Liberal, 18,527

Snatching defeat . . .

The 1988 federal election was the Liberals’ to lose, and lose it we did. Mulroney’s honeymoon with the electorate was long since over. Having had to stare down several scandals during his first mandate, Mulroney and his Tories were vulnerable. As well, he had to fend off accusations by his detractors that he was still saddled with or, worse still, comfortable with the branch plant mentality that had been his stock-in-trade as president of Iron Ore Company (IOC), a subsidiary of Cleveland’s Hanna Mining. His maudlin public love-in with Ronald Reagan fuelled perceptions of Pavlovian submission to all things American. Canadians want their leaders to cultivate a good working relationship with their US counterparts, not a cozy sleeping arrangement.

Leadership became a factor during the campaign, according to political scientist Jon Pammett.184 Though voters had their fill of Mulroney’s bluster and brinkmanship, many didn’t see Turner as a plausible alternative, undoubtedly influenced by media stories of caucus disaffection with his stewardship. CBC, “with no hard evidence of any kind”185, aired a story asserting there was an organized move afoot to force John Turner out.

I was far removed from the fray, busily knocking on doors in Monkstown, Margaree, and McKay’s. Yet even in those places, remote from the centre of action, prospective supporters were exposed to the media’s almost daily chronicling of Turner’s alleged troubles, and they frequently raised the matter with me.

Despite a strong performance by Turner, Mulroney won a second majority, the first Conservative prime minister to do so in a century. Party standings were as follows:

Progressive Conservative, 169 seats, 43% of the popular vote

Liberal, 83, 32%

New Democratic, 43, 21%

The FTA was ratified soon after, even though a majority of electors had voted for parties opposing the deal.

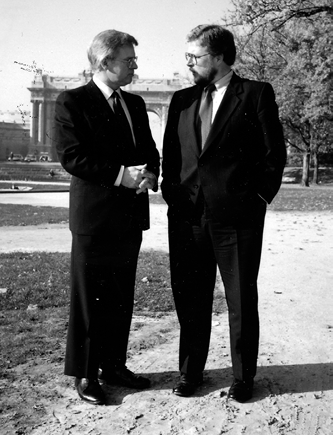

Brussels, Belgium, 1989. With Ross Reid, parliamentary secretary (later minister) for Fisheries and Oceans. (Author photo)

Bricks and Bouquets

Consigned to the opposition benches for another four years, the Liberal caucus met in St. John’s in early 1989 to lick its wounds, second-guess its election performance, and regroup for the battles ahead. There, I got to see Paul Martin in action for the first time. My initial impression was that, for a rookie MP, he was getting ahead of himself.

Nonetheless, during the ensuing years, I watched with admiration as Martin’s expertise and energy were deftly applied to his MP responsibilities and to his key role in readying the Liberal Party for the 1993 election. Subsequently, his stellar performance as Finance minister earned him well-deserved accolades far and wide. Martin’s brief stint as prime minister would be a far different story.

Rio de Janeiro, Brazil, 1992. The House of Commons’ Official Opposition delegation at the Earth Summit. L-R: Marlene Catterall (Ontario), Roger Simmons, Christine Stewart (Ontario), Charles Caccia (Ontario), Paul Martin (Quebec). (Author photo)

In the lead-up to the 1993 election, Opposition Leader Jean Chrétien tasked Martin with co-chairing a policy platform committee. As opposition Fisheries critic, I presented a policy paper entitled “Shoals & Shenanigans,” which reflected a consensus of my associate critics, (later Minister) Lawrence McAuley and Ron MacDonald, and me. Among other issues, it mapped out a strategy for dealing with the biggest threat to the fishing industry. The first Throne Speech following the election committed the new government to decisive action “to ensure that foreign overfishing of east coast stocks comes to an end.” That initiative was straight out of the proposals my two colleagues and I had advanced, and I was especially delighted when the new Fisheries minister, Brian Tobin, took dramatic and effective steps to deal with the problem. The arrest of the Estai, a Spanish trawler, after shots had been fired, immediately galvanized international action and eventually led to a more equitable fishing regime.

Rio de Janeiro, Brazil, 1992. At the Earth Summit, MP (later Prime Minister) Paul Martin and I chatted with (later Sir) Shridath “Sonny” Ramphal, former Secretary-General of the Commonwealth. (Peter MacLellan photo)

Day of reckoning

As Brian Mulroney neared the end of his second mandate, his best years, certainly insofar as elective politics was concerned, were behind him. The public’s antipathy toward him was palpable. No dummy, he read the writing on the wall and gave notice he would pack it in.

The ensuing race to succeed him soon became a coronation as party heavyweights such as Perrin Beatty, Barbara McDougall, and Michael Wilson, inexplicably cowed by the unlikely candidacy of rookie MP and Defence Minister Kim Campbell, opted not to contest the leadership. Within months of being acclaimed as the new PC chief, Campbell, savouring a tempting post-convention bump in the polls, dissolved Parliament, and the 1993 election was on.

The Liberal leader, Jean Chrétien, ran a near-flawless campaign, fielding an impressive slate of candidates and strategically dribbling out elements of a comprehensive policy platform, all neatly packaged in a so-called Red Book. Meanwhile, Campbell’s condescending forays were aggravated by a disingenuous effort to disown the Mulroney legacy, botched advertising, and a foot-in-mouth virus that cost her votes almost every time she spoke.

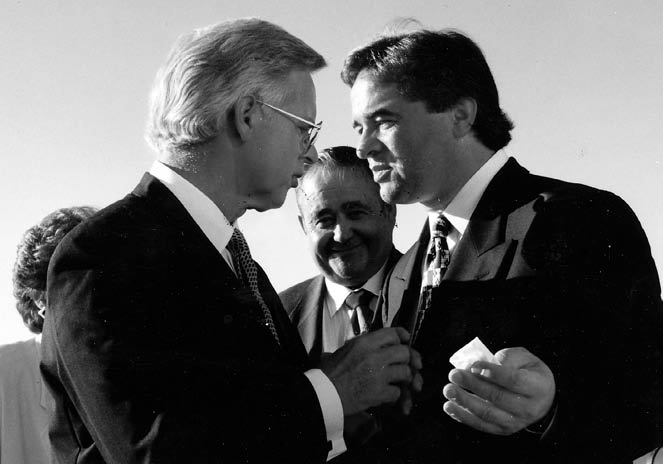

Ottawa, 1991. Waiting for a roll-call vote, I raised an issue with Prime Minister Brian Mulroney. Former Prime Minister Joe Clark is beside me. (J. M. Carisse photo)

The low point in the campaign was a Tory ad which was widely construed as a below-the-belt jab at the Liberal leader’s facial deformity, the result of Bell’s palsy when he was a child. The public backlash was electric and sustained. If the ad made voters think twice about getting on board with the Tories, it was Chrétien’s masterful handling of the incident that really upended their campaign bus:

“God gave me a physical defect. . . . When I was a kid, people were laughing at me. But I accepted that because God gave me other qualities, and I’m grateful.”

A further reference to the “face ad” was classic Chrétien:

“It’s true, that I speak on one side of my mouth. I’m not a Tory; I don’t speak on both sides of my mouth.”

Ostensibly, the electorate’s choice was between Campbell and Chrétien. In reality, the election was a referendum on the Mulroney legacy, and voters were in a judgmental, unforgiving mood. When the dust settled on polling day, the Tory bloodbath was unprecedented, the worst electoral defeat in Canadian history. Only two of the party’s 295 candidates survived. Even the prime minister lost her seat.

There was a certain biblical déjà vu in the Tory results—two MPs, one male, one female; one francophone, one anglophone; one minister, one backbencher; a moderate and a right-winger. As with Noah of old, voter-inflicted retribution for past transgressions was tempered only by the imperative to continue the species. The ultimate wisdom of the electorate should never be underestimated.

Chrétien and the Liberals won a resounding victory, and, for the fourth time, the great people of Burin–St. George’s decided I should be their advocate in Ottawa. The seat numbers told the national story:

Liberal 177, Bloc Québécois 54, Reform 52

New Democratic 9, Progressive Conservative 2

If the drubbing of the once-mighty Tory Party was a watershed event, the electorate’s choice of Her Majesty’s Official Opposition was also an eye-opener. Lucien Bouchard’s separatist party, the Bloc Québécois, had edged out the Reform Party, whose overnight emergence as an electoral player heralded a seismic realignment in the body politic.

Arsonists in the fire brigade

Recently, while addressing a group of US students visiting Canada and wanting to learn about our political system, I noted there are four parties represented in the House of Commons and quickly rhymed off three, Conservative, NDP, and Liberal. Then, I drew a blank. I could not for the life of me name the fourth party. Really, why should I? Mine was, revealingly, a mental “bloc.” You see, I’ve never been able to get past the incredulity of a taxpayer-funded presence in Parliament of a party whose avowed objective is to destroy the institution and the country it is elected to serve.

For seven of my fifteen years in the House of Commons, I sat opposite or next to Bloc MPs. During four of those years as chair of the standing committee on health, my vice-chair was a Bloc member, my late good friend, the congenial, upbeat Pauline Picard. I travelled on parliamentary junkets to China and Ukraine with members of the Bloc caucus. In Seattle, I hosted House of Commons committees including Bloc MPs. In other words, I’ve seen those guys and gals close up. I made many friends among them. A finer assemblage of humanity, intelligence, and good humour you couldn’t find.

But, as politicians, they have an agenda, one which is diametrically opposed to mine and to Canada’s. I went into Parliament with the notion that my presence could improve the lot of those I represented and otherwise contribute to fostering a better country. Bloc MPs go there to tear the country apart. After more than twenty years of trying their best to do so, their scheme is in tatters. It’s high time they threw in the towel. Yet they linger. Why? The pay is good. Pension entitlement gets better by the day.

Calculating, competitive, caring

I have known Brian Tobin for more than forty years. I was one of the three caucus members who interviewed him for his job as a press aide to the provincial Leader of the Opposition, first Bill Rowe, then Don Jamieson. His energy, clear-headedness, and people skills closed the deal for him then, as they have consistently done ever since. Tobin’s foresight and his ability to see the larger picture, his lightning grasp of complex files, and a decisive approach to resolving issues have well served him and Canada. I have greatly admired his fierce competitive streak, though, if truth be known, I was sometimes the one outfoxed by his wiles.

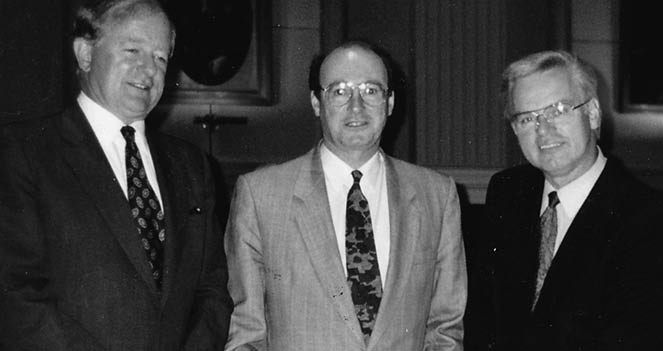

Ottawa, 1995. Going head to head. L-R: MPs Roger Simmons, Ron Fewchuk (L, Manitoba), Brian Tobin. (J. M. Carisse photo)

Brainy, articulate, fast on the draw, take-no-prisoners. That’s the Brian Tobin Canadians see. Yet there’s a whole other dimension to him which may not be readily obvious to those who know him only as a public figure and business entrepreneur. From the first time he and I met, when he showed up on my doorstep to offer support for my 1977 provincial Liberal leadership run, I’ve often had the good fortune to be on the receiving end of his generosity, humanity, and empathy. During my 1983 hospitalization at Ottawa’s National Defence Medical Centre, Brian was the only MP to drop by. While he was a federal cabinet minister and, then, premier of Newfoundland and Labrador, he and I collaborated on many files aimed at benefiting our constituents. When I lost my 1997 re-election bid, he was on the phone that very night from Toronto, taking time out from his gig as a national TV election analyst. In early 2004, as I was trying to make a go of my new consulting business, it was Tobin who lined me up with a Calgary developer with whom I secured a long-term contract.

Tompkins, NL, 1993. “First lady of the accordion.” With the talented Minnie White, CM, and her daughter, Barbara. (Author photo)

As a member of Parliament’s ingenious Rat Pack, Brian Tobin had distinguished himself as a skilled debater and strategist. When the Tories won power in 1984, he and fellow Rat Packers Don Boudria, Sheila Copps, and John Nunziata kept government ministers on their toes and cemented the Liberals’ profile as a proactive, effective opposition. Brian was a key Chrétien activist during the 1990 Liberal leadership campaign and the Liberals’ 1993 election victory. His well-earned status as a valued Chrétien player, coupled with my blotted copybook in the 1983 RevCan affair, meant that Tobin, not I, would be a shoo-in for Newfoundland and Labrador’s seat in cabinet.

Like legions of other Canadians, I was deeply disappointed when Tobin abandoned his 2003 Liberal leadership campaign in the face of the Paul Martin juggernaut. John Crosbie’s promising candidacy in the 1983 Tory leadership was torpedoed by his inability to speak passable French. Crosbie and Tobin had racked up enviable track records as leaders, both in Newfoundland and Labrador and nationally. Oft has it been said of Robert Stanfield186 that he was among the best prime ministers Canada never had. John Crosbie and Brian Tobin belong to that exclusive club.

Loose lips sink ships

Some days, it’s best to keep your mouth shut, one of the many lessons I’ve learned the hard way. In 1993, I was one of several MPs who let their names stand for the House of Commons Speakership. I had positioned myself well for a serious bid. The several Liberal colleagues who were also candidates could be expected to garner the lion’s share of caucus support. My strategy, while not neglecting my Liberal friends, was to focus on the other caucuses and, specifically, the Bloc Québécois and Reform MPs.

A bit of sheer good luck gave me a kick-start. I found myself at the same Calgary hotel as the new batch of Reform MPs who were convening for their first caucus since their dramatic success at the polls, going from a single seat in Parliament to fifty-two. For two whole days, I had a captive audience of newbies, all friendly, most of them anxious to have corridor conversations to glean insights on the finer points of life on Parliament Hill. I subsequently met in Ottawa with the entire Reform caucus. I came away with many assurances of support and believed I would do very well among Reform MPs, a conclusion confirmed by my good friend John Cummins187, a Reform member from BC who was partial to my candidacy.

As I had done prior to my session with the Reformers, I thoroughly briefed myself on MPs in the other caucuses as though cramming for a final exam. My trusty researcher, Catherine Parker, would sit across the desk quizzing me on the names of constituencies and their respective MPs until I could match every last electoral riding with its MP’s name and photo.

The Bloc Québécois was a special challenge. My oral French capability was limited, especially in a meeting with fifty-four MPs whose mother tongue was Quebec French with its rich idioms and nuanced intonations, noticeably different than the international French I had studied. Here again, Lady Luck was on my side. The scheduled fifteen-minute question and answer session went on for more than an hour. I believe I understood most of what was said to me, and either the Bloquists comprehended my responses or they were awfully polite in not saying otherwise. At the conclusion of the meeting, my assessment was that most of the Bloc MPs were comfortable with my candidacy. One in particular, Claude Bachand188, an early supporter, was optimistic that most of his colleagues would vote for me.

With what seemed like solid support for my candidacy in the two largest opposition caucuses and the assurance of a smattering of votes from my own caucus, it looked like I would be a viable contender for the Speakership.

It was then I made my big blunder. I opened my mouth. On the afternoon before the Speaker vote, members of the Liberal caucus went to the Commons chamber to get a first look at the new seating assignments. Two cabinet ministers and I mused about the upcoming vote, and I mentioned the presumed strength of my support in the Bloc and Reform caucuses. The telltale body language which my bragging triggered in my two colleagues instantly made me regret my confident strutting and ego-tripping. All too soon, I would know why.

Early next morning, just a couple of hours before the vote, I got two phone calls in quick succession. John Cummins called to say that his Reform colleagues couldn’t support me because of my “continuing income tax problems.” That matter had been fully resolved ten years earlier, a fact that got omitted from the overnight smear job. Minutes later, Claude Bachand was on the phone saying that his leader, Lucien Bouchard, had it from “a reliable source” that I was “recklessly anti-Quebec.”

The fix was in. Quick-thinking Liberal colleagues, with agendas different than mine, had torpedoed any chance I had of becoming Speaker. But it was my wagging tongue that had launched the missile.

I am not suggesting that, but for some creative overnight mischief-making that decimated my potential Bloc and Reform support, I would have been chosen. The man elected that day, the late Gilbert Parent, and his successor, Peter Milliken, also a candidate in 1993, were formidable contestants and, like a fourth candidate, the late Jean-Robert Gauthier, were highly respected, active Members of Parliament. Each of them had large followings, not only in the government caucus but on all sides of the five-party chamber. I do know, however, that my failure to button my lip when it mattered and the mischief it spawned ensured I would be nothing more than an also-ran. Yet another valuable lesson learned.

Though I wasn’t a happy camper at the time, I didn’t feel betrayed. Instead, my real anger was directed toward my glibness and strategic stupidity. I regarded the incident as just a couple of guys who faced a choice between friendship and political considerations. All politicians make that choice almost daily. John Crosbie notes, “Friendship count(s) for less in politics than in any other field”189. And, according to Brian Tobin, “Friendship in politics must be peripheral to other concerns”190. Just about all the opponents I faced in nomination and election battles have been among my good friends. I’ve never thought of friendship as cloning.

Port aux Basques, NL, 1995. Me, MHA Bill Ramsay, Mayor Aneitha Sheaves, provincial Minister John Efford. (Author photo)

Politics, a blood sport

There was one pivotal incident that breached the usual civility that is the hallmark of electioneering in Newfoundland. The event was pivotal because, I believe, it single-handedly transformed my 1997 election candidacy into a lost cause.

At a Port aux Basques public rally, a man stepped up to the floor microphone and, interrupting my response to a question, shouted “Liar! Liar!” The aggressive intervention was timely in at least one respect. Jim Carrey’s popular movie of the same name was in theatres and, obviously, gave rise to the wording of the interjection.

The audience was justifiably exercised over the shortage of doctors in rural areas. My party, on assuming office four years earlier, had taken an axe to the outrageously high deficit inherited from the previous administration. The resulting government cutbacks in funding to the provinces for health care had struck a nerve with the public, indeed, had become a dominant issue in the campaign. “Liar, liar” mobilized the audience’s anger over the health issue. There was thunderous applause. At that moment, standing at the onstage mic was a very lonely vigil.

Things got worse in the days ahead. A CBC video camera had captured the moment, including the blood-drained stare on my face, and the clip was aired repeatedly, not only in the next day’s news bulletins but for the rest of the campaign whenever a promo for election night coverage was shown. The “liar” incident and its frequent reruns on TV helped to energize the health protest vote and had, I believe, an adverse impact on the chances of every Liberal candidate in the province. For me, and for my fellow Newfoundland MPs, election night counts told the tale as our massive Liberal margins of previous campaigns shrunk dramatically.

Did I think the “liar, liar” intervention was unfair? Of course. I had the facts to refute the charge. But no one was listening. Reasonable politics is an oxymoron. Political fortunes can turn on a dime. “Liar, liar” was my dime.

It was all downhill after that. The incident telegraphed that I was vulnerable in what was considered a safe Liberal seat. In the previous election, four years earlier, I had garnered seventy per cent of the votes cast, the fifth-highest percentage of all 1,500 candidates across Canada. It would be a very different story this time.

Shooting the messenger

There’s a time-tested adage that says, “Four things come not back—the spoken word, the spent arrow, wasted time, the neglected opportunity.” With deadly skill, I managed to trample the wisdom of that cautionary line by opening my trap when I should have clamped it shut. In a media interview soon after that game-changing night in Port aux Basques, I let go with a one-liner, “The CBC got out of the news business years ago.”

Yes, the “liar” story had created a big problem for me and my campaign. But it was I who compounded the damage by trying to shoot the messenger. You must never taunt the guy holding the mic, especially if he gets to use it on television every day. That valuable lesson was learned too late to salvage my plummeting electoral fortunes. But it was learned.

On reflection, it was my journalistic instincts, shaped during stints as a daily newspaper editor and a magazine and weekly publisher, that put the incident in its proper context. The CBC video journalist had done exactly what I would have done. Beyond the size of the crowd and the issue that drew them to the hall, there wasn’t much about the event that would make it to the evening news. The “liar, liar” outburst was pure gold for the reporter. He got his story and, from his perspective, a captivating film clip to go with it.

Close only counts in horseshoes and hand grenades191

What turned out to be my last kick at the can, electorally speaking, wasn’t the roaring success I dearly wanted it to be. I came up short. My long stint in politics was over. What an amazing experience it was! For close to a quarter of a century, I had the honour of being the voice of the best people on the planet. I am proud and grateful beyond words, and will ever be.

A week or so after the election, I attended my last caucus. Defeated incumbents and MPs who had not sought re-election were each presented with a plaque of appreciation and invited to say a few words. By the time my turn came, I had to dig deep for something that had not already been said:

“Driving here today, as I caught a glimpse of the Peace Tower, my reaction was not regret that I will no longer be here, but pride that I have been.192 The opportunity of representing one’s fellow citizens is a unique privilege. It gives me great satisfaction that I was able to do so.

“As a teenager, I ran away from home. My first night on the lam, I slept on a concrete dock. Thirty years later, I was having dinner with the Queen. On both occasions, my first thought was exactly the same: What am I doing here?

“Each of these incidents taught me a valuable lesson which has since served me well. I commend them to you, especially new MPs. First, set a high personal standard. And two, take full advantage of every opportunity, however fleeting or unusual.”

179 Julius Caesar, William Shakespeare, Act 1, Scene 2

180 Official residence of the Leader of the Official Opposition

181 Divided Loyalties, Brooke Jeffrey, Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 2010, p. 116

182 No Holds Barred, John Crosbie, Toronto: McClelland & Stewart, 1997, p. 212

183 Divided Loyalties, Brooke Jeffrey, Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 2010, p. 56

184 Ibid, p. 162

185 Ibid, p. 148

186 Lawyer, premier of Nova Scotia (1956–67), leader of the federal Progressive Conservative Party, and Leader of the Opposition (1967–76)

187 British Columbia MP, 1993–2011; leader of the BC Conservative Party, 2011–13

188 Quebec MP, 1993–2011

189 No Holds Barred: My Life in Politics, John Crosbie, Toronto: McClelland & Stewart, 1997, p. 63

190 All in Good Time, Brian Tobin, Toronto: Penguin, 2002, p. 66

191 Frank Robinson (1935–), baseball player, first African-American manager of a major league team, Baseball Hall of Fame member

192 A similar sentiment is a proverb frequently attributed to American author Theodor Seuss Geisel (1904–91), pen name Dr. Seuss, but also to Gabriel García Márquez (1927–2014), Colombian writer and journalist: “Don’t cry because it’s over. Smile because it happened.”