O for the touch of a vanish’d hand

And the sound of a voice that is still!

— Alfred Lord Tennyson

In addition to my intervention on behalf of Major Sarah Woodland, on only one other occasion have I been presumptuous enough to propose a candidate for an honorary degree. Memorial’s president, Axel Meisen, came to my Seattle office in 2003. I suggested that he consider a man whose contribution to Newfoundland, to Canada-US relations, and to racial harmony was immeasurable, Lanier Phillips.

There is a certain symmetry in my two choices: a woman and a man; one Caucasian, the other African-American; one Canadian, the other American. However, singling out these two persons was not about political correctness or balance. Rather, it was their amazing impact on others.

Though Sarah Woodland and Lanier Phillips were contemporaries, they were nurtured in vastly different worlds. Yet both wielded influence in the same arena, Newfoundland, and heralded the same message of love, forgiveness, and transformation. Both triumphed in spades. We are the better because of the spiritual trails blazed by two illustrious honorary graduates of my great alma mater, Memorial University: Dr. (Major) Sarah Woodland and Dr. (Mess Attendant Third Class) Lanier Walter Phillips.

Lanier Phillips was a rare bird. Born in racist Georgia in 1923, he saw first-hand the terror of the Ku Klux Klan and was taught by his great-grandmother to fear white people: “Never look a white man in the eye. If you do, you’ll get whipped or, maybe, lynched.”

To escape the segregated south, Lanier joined the US Navy when America entered the Second World War in 1941 and was assigned to the USS Truxtun, a destroyer. Lanier was a mess attendant third class, the only aboard-ship position he was permitted to fill as an African-American. Washing dishes, polishing officers’ boots, and doing other such menial tasks were his daily lot. He and the other four black men in the crew took their meals standing up since the dining mess was the exclusive domain of white men.

In mid-February 1942, the Truxtun and two other vessels, the Wilkes, also a destroyer, and the Pollux, a supply ship, sailed from Portland, Maine, destined for a US naval station at Argentia, Newfoundland. As they approached land in a severe storm, confusion and uncertainty reigned concerning the true locations of the three warships. Misinformation, wrong assumptions, indecision, and pigheadedness were among the causes. The consequences were catastrophic as all three vessels rammed the Newfoundland coast and two of them broke up in the heavy seas. Two hundred and three young Americans died in the icy North Atlantic that awful night, literally feet from safety. The good news is that 185 sailors did survive, saved by St. Lawrence miners and the men of Lawn, two small communities on Newfoundland’s south coast.

When he saw him, he had compassion on him209

Lanier Phillips was the only black man to survive. The other four perished following what was literally a life-and-death decision. Thinking they had gone aground in Iceland and knowing that the US government had agreed that blacks would not be allowed ashore in that country, the five men contemplated a stark choice, whether to go ashore and risk being lynched or stay aboard and face almost certain death by exposure. Only Lanier opted to take his chances ashore.

As he landed on the narrow rock ledge underneath a forbidding cliff, fatigue and sub-zero weather were taking their toll, physically and mentally. Lanier recalled the moment: “I decided to die!” Other people had a better plan. As Lanier lay in a fetal position on the beach, he heard a voice above him. “Get that man up! He’ll surely die there.” Lanier caught a glimpse of the two men standing over him. Something truly staggering flashed across his mind.

A white man wants me to live!

With the help of the two strangers, Lanier made it up the precipice and was taken by horse-drawn sled to a nearby mining shack.

The women of St. Lawrence had come to the mine site to help with the rescue operation. Many of the Truxtun’s survivors were coated in oil from the ship’s ruptured tanks. The local ladies scrubbed them down as they arrived in the shack. Phillips, who had lapsed into unconsciousness, recalled waking up:

“I was lying stark naked face up on a table. Two white women were hovering over me. Maybe, I thought, they belong to some pagan tribe and are preparing to sacrifice me. At that moment, I was more terrified than when I clung to the Truxtun wreck. One of the two ladies spoke. ‘I can’t get this one clean.’ That’s when I opened my mouth for the first time. ‘Ma’am, that’s the way I was born.’”

Violet Pike and Charlotte Kelly may have understood the words Lanier said. They certainly didn’t comprehend the import of his utterance, having never before seen a black man. Without missing a beat, Mrs. Pike responded, “Don’t worry, my son, we’re going to get you clean, supposin’ we’re here all night.”

Outstretched hands

Today, a unique and moving memorial honours the memory of the lost, the courage of the survivors, and the selflessness of their saviours. Situated in the town square at St. Lawrence, it is the work of Newfoundland sculptor Luben Boykov, who ingeniously captures the moment of rescue. A steep marble incline represents the rock face that stood between the shipwrecked and safety. At the base of the incline, a prostrate figure in navy dress extends his right hand upwards. At the top, a man with a miner’s light strapped to his forehead extends his hand toward the sailor. Their extended hands nearly touch, but not quite, symbolizing both the almost unfathomable gulf that separates them and the spiritual bond that unites them.

The striking memorial is a well-known Bible story in 3-D. All the elements are in play: two men from vastly different worlds, one with a desperate need, the other able and willing to meet that need. Boykov’s masterpiece is aptly titled Echoes of Valour. I’ve always thought of it as the Good Samaritan sculpture.

Transformation

Fifty years after the Truxtun-Pollux tragedy, I boarded the USS Samuel Eliot Morison at Montreal. St. Lawrence Mayor Fabian Aylward and I embarked on a two-day voyage to Chambers Cove, where the Truxtun had met its end and where Lanier Phillips had chosen an uncertain future ashore over almost certain death on the doomed ship. We paused over the deteriorating wreck, which can still be seen just below the surface. Our moment of reflection over, we headed into St. Lawrence harbour to participate in a reunion of many of the survivors, their families, and their rescuers. The town hosted a celebratory event, and Lanier Phillips was the after-dinner speaker. He spoke of that long-ago day when he had been touched by a white person for the very first time in his life. He recalled how astonished he had been to be treated evenly by white people: “I asked myself, did I die and go to Heaven?” Phillips’s listeners were spellbound as he recalled that momentous morning half a century before:

“Mrs. Pike took me into her home. She tucked me into bed, heated rocks in her stove to warm my feet, and spoon-fed me soup.”

And then he spoke of the jolting, bitter aftermath:

“A US navy ship arrived at St. Lawrence to pick up the white survivors. I was told I had to wait for a freight boat. . . . A few days later, now back in the southern US, I was hungry and tried to enter a military mess. As I reached for the doorknob, a white guard knocked me to the ground with his rifle butt.”

The black sailor who had just survived a watery grave in the service of his country could only watch through the window as white men enjoyed a hearty meal. And not just any white men. The diners were German prisoners of war. In Lanier’s absence from the south, and despite his transforming encounter with white people in Newfoundland, nothing had really changed. Except Lanier Phillips was a different man. At the St. Lawrence reunion, Lanier told his audience, “You people not only saved my life, you changed my life.”

And changed he was. I was thoroughly captivated by his words and by the passion and sincerity with which he spoke them. Then and there, I told myself the whole world should hear his story and should hear it from him. Over the succeeding eighteen years, until I went to the Middle East in 2010, I organized events each year, with Lanier as the speaker, to coincide with the anniversary of the dramatic rescue. From San Diego, California, to Nanaimo, British Columbia, we took his message of racial equality to schools and colleges, to service clubs and editorial boards, to public meetings and broadcast audiences. We even participated in an online link between schools in Washington state and Newfoundland.

Poignant moments

Three memories stand out. In View Royal, near Victoria, BC, the 200 primary students who had assembled in the school library were the youngest audience Lanier had addressed, and he was concerned that he wouldn’t be able to connect with them. He need not have worried. He asked rhetorically: “Should a black man have to serve a white man?”

Every five-year-old hand in the front rows shot up. I pointed to a cute little blonde girl who was bursting to respond to Lanier’s question.

“Not unless he’s hurt.”

What is it the Book of Psalms says about “out of the mouths of babes’’? The five-year-old had succinctly compressed the essence of Lanier’s message into a single phrase. Human relationships ought to be catalyzed by need and compassion, not skin colour.

Montreal, 1992. The captain of the USS Samuel Eliot Morison, a US Navy frigate, greeted St. Lawrence Mayor Fabian Aylward, right, and me when we embarked on a memorable voyage to Chambers Cove, where Lanier Phillips was shipwrecked. (Author photo)

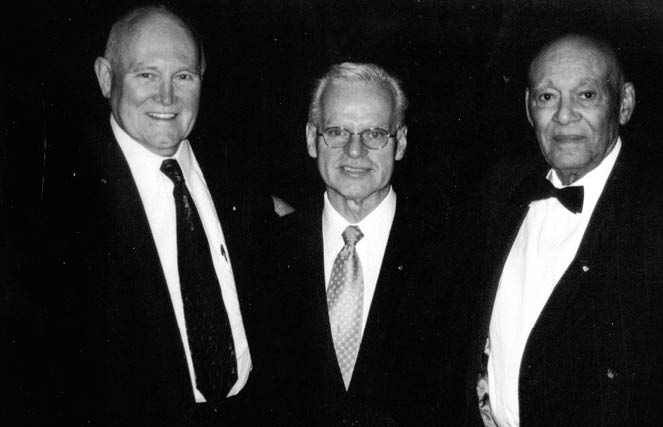

On Valentine’s Day, 2003, Lanier addressed a public meeting at Seattle’s Town Hall. As the crowd gathered, an elderly Caucasian gentleman approached Lanier and said, “I was on the Pollux!”

Edgar Brown, who also grew up in the US south, was an officer on the supply ship when it rammed the Newfoundland coast that fateful night sixty-one years earlier. Ensign Brown and Mess Attendant Third Class Phillips—two men, one white, one black—embraced. The years fell away, as did the bigotry of another time.

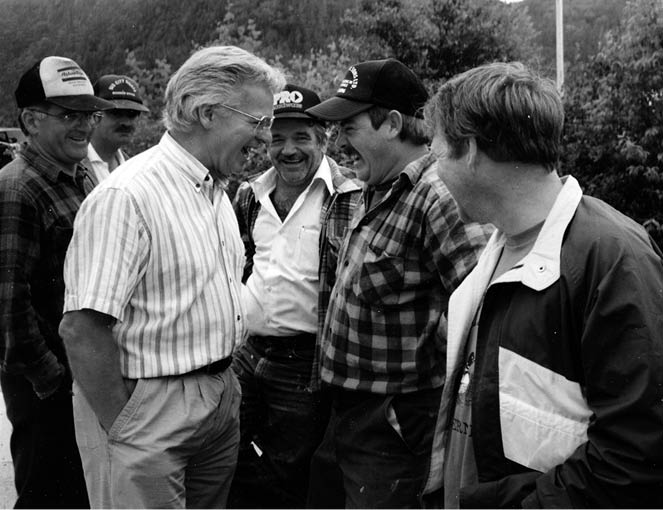

Pool’s Cove, NL, 1993. L-R: Gordon Caines, Melvin Perham, Pius Fizzard, Bruce Savoury. (Author photo)

A never-to-be-forgotten moment happened in Santa Rosa, California. It was Sunday morning, and Lanier and I were standing with the pastor of a Baptist congregation in the entrance foyer of his church. Our sponsors for the California tour, Hugh and Connie Codding, were with us. As we awaited the arrival of parishioners, among the first to enter was an elderly African-American. Spotting Lanier, the man ran to him and, weeping uncontrollably, threw his arms around him and uttered words whose significance only Lanier could fully comprehend: “I was at Pearl Harbor.” Decoded, the stranger’s utterance had said, in effect, “I was a Mess Attendant Third Class in World War II, just like you. I know what you went through.”

Lanier and I sat behind the pulpit with the pastor. A thousand people had come to church that morning. One person in particular had my attention. Sitting in the front row, that same elderly war veteran sobbed his way through the church service and Lanier’s speech which followed. His name—and no, I’m not making this up—was Brother Love!

Lanier’s presence had provided a measure of closure. Sixty years after Pearl Harbor, Brother Love had finally encountered someone who understood the humiliation and cruelty he had endured.

Hugh Codding. Now, there was a character! He served in World War II and was attached to a naval unit at Iwo Jima when the conflict ended. Rambunctious, larger-than-life, and savvy, he was a very wealthy business tycoon and owned a dozen shopping malls in Sonoma County, north of San Francisco.

Codding was in his mid-eighties when he and I met “down under” in a Trident nuclear submarine just off Bangor, Washington. I told him about Lanier and our annual speaking tours. Hugh invited us to come to Santa Rosa, and that’s how we wound up in a southern Baptist church that memorable Sunday morning.

The previous week, Lanier and I had been in Burbank to meet with film industry people, after which we planned to take a commercial flight to San Francisco and a car to Santa Rosa. Hugh had a better idea. He sent his personal jet to Burbank, and we travelled direct to our destination in style. Yes, I sat up front with the pilot. This time, though, I had the good sense to keep my mouth zipped about my vaunted expertise at manoeuvring aircraft.

When we touched down in Santa Rosa, our pilot, CJ, drove us to the Codding mansion. Lanier and I spent the next couple of days salivating in the lap of luxury. Two old navy guys became buddies as they swapped war stories. I was impressed, awed, even, as Connie and Hugh, Caucasian both, showered affection and deference on Lanier, treating him like royalty, which he was.

Bigotry, alive and well

Lanier lived at the naval retirement facility in Gulfport, MS. It was home to hundreds of veterans. Only a handful were African-American. As Lanier and I walked the corridors, many of the white residents greeted him warmly; others shunned him. Some hugged the far wall as we passed. A white man boarded an elevator. Lanier and I followed. The white man abruptly left. My curiosity got the better of me. I exited the elevator on the next floor, raced down the stairs, and watched in disgust as the white guy boarded the elevator.

Lanier seemed never to be perturbed by such affronts. A lifetime of being on the receiving end of rank prejudice had long since taught him to bite his lip and move on. Occasionally, in response to my reactions of disbelief, he would calmly say, “They can’t help it. That’s the way they were reared. It’s their problem, not mine!”

Powerful words

By late 2007, no action had been taken by Memorial on my recommendation that it recognize Lanier Phillips’s remarkable achievements. I decided to try one more time and mentioned my proposal to the university’s chancellor, my old friend and sparring partner during the political wars, John Crosbie.

Lanier had moved to the Armed Forces Retirement Home (AFRH) in Washington, DC, after his former residence, the naval home in Mississippi, had become a casualty of Hurricane Katrina in 2005. In early 2008, on one of my frequent visits to Lanier’s room, he excitedly showed me a letter from Memorial University. He would be awarded an honorary doctorate of laws and be the May convocation speaker. Crosbie had delivered yet again.

It was indeed a proud moment as I sat beside Lanier’s daughter, Dr. Vonzia, his son, lawyer Terry, and daughter-in-law, Tamara, in the VIP box at the St. John’s Arts and Culture Centre, the convocation venue. Lanier had been a bag of nerves in the days leading up to his convocation address. Though clear on the message he intended to deliver, he doubted whether he could measure up in front of so many academics.

Rising magnificently to the occasion, Lanier transported his listeners by his humility, humanity, and passion. He spoke for just thirteen minutes. As he finished, the 1,200-strong assemblage, faculty and dignitaries, graduands and their families, rose as one in thunderous applause, a tangible tribute to a legend whose powerful message and captivating storytelling style had electrified and inspired audiences all over North America.

Feisty to the end

I had lunch with Lanier at his Washington retirement home the day after President Obama’s 2009 inauguration. Age was taking its physical toll, though, with the aid of a four-point walker, Lanier was still mobile. Mentally, he was not diminished. He was the same engaged, inquisitive conversationalist I had first met nearly seventeen years earlier and, I believe, the same fighting spirit whose will to live landed him on a rocky shelf on a frigid wintry night fifty years before that. It was the last time I saw him, though we continued to connect by phone while I was on assignment in the Middle East.

Lanier spent his final years back in Gulfport, MS, at the rebuilt military retirement facility. Sadly, he passed away in March 2012, three days shy of his eighty-ninth birthday. He left us quite a legacy.

Many a sailor has been shipwrecked and lived to tell the tale. Few have been changed by the experience as thoroughly as Lanier was. Fewer still have catapulted their transformation into an irresistible plea for equality and compassion as effectively as the great-grandson of slaves, Dr. Lanier Phillips.

209 Luke 10:33, KJV