Chapter 1

Entering the World of Buddhism: The Basics

In This Chapter

Realizing Buddhism’s growing popularity

Realizing Buddhism’s growing popularity

Considering whether Buddhism is a religion

Considering whether Buddhism is a religion

Examining the role of the Buddha

Examining the role of the Buddha

Understanding the significance of Buddhist philosophy

Understanding the significance of Buddhist philosophy

Exploring Buddhist practices

Exploring Buddhist practices

Not too long ago, the West was virtually unfamiliar with the teachings of Buddhism. Back in the 1950s and ’60s, for example, you could’ve gone about your life scarcely hearing the word Buddhism mentioned. Sure, you may have come across Buddhist concepts in school in the writings of American Transcendentalists like Thoreau and Emerson (who read English translations of Buddhist texts in the mid–19th century). But the fact is, if you were like most middle-class people then, you may have grown up, grown old, and died without ever meeting a practicing Buddhist — except perhaps in an Asian restaurant.

If you wanted to find out about Buddhism in those days, your resource options were few and far between. Aside from a rare course in Eastern philosophy at a large university, you’d have had to dig deep into the shelves and stacks at your local library to discover anything more than the most basic facts about Buddhism. The few books that you could get your hands on tended to treat Buddhism as if it were an exotic relic from some long-ago and faraway land, like some dusty Buddha statue in a dark corner of the Asian section of a museum. And good luck if you wanted to find a Buddhist center where you could study and practice.

Today the situation is much different. Buddhist terms seem to pop up everywhere. You can find them in ordinary conversation (“It’s just your karma”), on television (Dharma and Greg), and even in the names of rock groups (Nirvana). Famous Hollywood stars, avant-garde composers, pop singers, and even one highly successful professional basketball coach practice some form of Buddhism. (We’re thinking of Richard Gere, Philip Glass, Tina Turner, and Phil Jackson, but you may be able to come up with a different list of celebrities on your own.)

Bookstores and libraries everywhere boast a wide range of Buddhist titles, some of which — like the Dalai Lama’s Art of Happiness (Riverhead Books) — regularly top The New York Times best-seller lists. And centers where people can study and practice Buddhism are now located in most metropolitan areas (and many smaller cities as well).

What caused such a dramatic change in just a few decades? Certainly, Buddhism has become more available as Asian Buddhist teachers and their disciples have carried the tradition to North America and Europe. (For more on the influx of Buddhism to the West, see Chapter 5.) But there’s more to the story than increased availability. In this chapter, we try to account for the appeal this ancient tradition has in today’s largely secular world by looking at some of the features responsible for its growing popularity.

Figuring Out Whether Buddhism Is a Religion

Wondering whether Buddhism is actually a religion may seem odd. After all, if you consult any list of the world’s major religious traditions, you inevitably find Buddhism mentioned prominently alongside Christianity, Islam, Hinduism, Judaism, and the rest. No one ever questions whether these other traditions are religions. But this question comes up repeatedly in relation to Buddhism.

The answer depends on how you define religion. Ask most people what comes to mind when they think of religion, and they’ll probably mention something about the belief in God, especially when discussing the creator of the world or universe. Our dictionary agrees. Webster’s New World College Dictionary defines religion as a “belief in a divine or superhuman power or powers to be obeyed and worshiped as the creator(s) and ruler(s) of the universe.”

Worship of a supernatural power isn’t the central concern of Buddhism. God (as this word is ordinarily used in the West) is absent from Buddhist teachings, although some Buddhists do worship gods and celestial Buddhas.

Worship of a supernatural power isn’t the central concern of Buddhism. God (as this word is ordinarily used in the West) is absent from Buddhist teachings, although some Buddhists do worship gods and celestial Buddhas.

Buddhism isn’t primarily a system of belief. Although it teaches certain doctrines (as we discuss throughout Part III), many Buddhist teachers actively encourage their students to adopt an attitude that’s the opposite of blind faith.

Buddhism isn’t primarily a system of belief. Although it teaches certain doctrines (as we discuss throughout Part III), many Buddhist teachers actively encourage their students to adopt an attitude that’s the opposite of blind faith.

Many Buddhist teachers advise you to be skeptical about teachings you receive. Don’t passively accept what you hear or read — and don’t automatically reject it, either. Instead, use your intelligence. See for yourself whether the teachings make sense in terms of your own experience and the experience of others. Then, as the Dalai Lama of Tibet (see Chapter 15) often advises, “If you find that the teachings suit you, apply them to your life as much as you can. If they don’t suit you, just leave them be.”

Buddhist teachings therefore encourage you to use the entire range of your mental, emotional, and spiritual abilities and intelligence — instead of merely placing your blind faith in what past authorities have said. This attitude makes the teachings of Buddhism especially attractive to many Westerners; although it’s 2,500 years old, it appeals to the postmodern spirit of skepticism and scientific investigation.

In addition to fundamental teachings on the nature of reality, Buddhism offers a method, a systematic approach involving techniques and practices, that enables its followers to experience a deeper level of reality directly for themselves. In Buddhist terms, this experience involves waking up to the truth of your authentic being, your innermost nature. The experience of awakening is the ultimate goal of all Buddhist teachings. (For more on awakening — or enlightenment, as it’s often called — see Chapter 10.) Some schools emphasize awakening more than others (and a few even relegate it to the background in their scheme of priorities), but in every tradition, it’s the final goal of human existence — whether achieved in this life or in lives to come.

By the way, you don’t have to join a Buddhist organization to benefit from the teachings and practices of Buddhism. For more info on the different stages of involvement in Buddhism, see Chapter 6.

Recognizing the Role of the Buddha

Buddhist systems are based upon the teachings given 2,500 years ago by one of the great spiritual figures of human history, Shakyamuni Buddha, who lived in the fifth century BCE. According to legendary accounts of his life (see Chapter 3), he was born into the ruling family of the Shakya clan in today’s Nepal and was expected to someday succeed his father as king. Instead, Prince Siddhartha (as he was known at the time) quit the royal life at the age of 29 after he saw the reality of the extensive suffering and dissatisfaction in the world. He then set out to find a way to overcome this suffering.

After many hardships, at age 35, Prince Siddhartha achieved his goal. Seated under what became known as the Bodhi tree — the tree of enlightenment — he achieved the awakening of Buddhahood. Today a stone platform known as the diamond seat (vajrasana) near the Bodhi tree in Bodh Gaya (see Figure 1-1) marks the spot. From then on, he was known as Shakyamuni Buddha, the awakened (Buddha) sage (muni) of the Shakya clan.

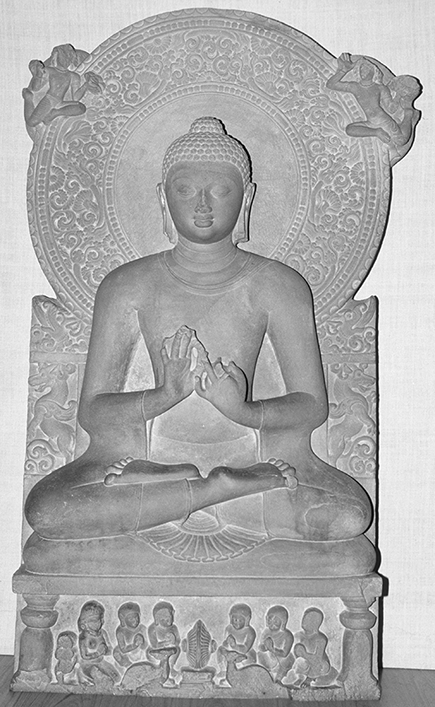

Prince Siddhartha spent the remaining 45 years of his life wandering the northern part of the Indian subcontinent, teaching anyone who was interested in the path that leads to freedom from suffering. The famous Buddha statue in Sarnath (India), the place where he gave his first sermon (see Figure 1-2), shows the Buddha making the gesture of turning the wheel of his teaching. (Part III offers an overview of the entire Buddhist path.) After a lifetime of compassionate service to others, Shakyamuni died at the age of 80.

Figure 1-1: Stone platform and Bodhi tree in Bodh Gaya.

Figure 1-2: Shakyamuni Buddha.

The question is often asked, “What kind of being was Shakyamuni Buddha — a man, a god, or something else?” Some biographical accounts state that the Buddha was once a human being with the same hang-ups and problems as everyone else. He didn’t start out as a Buddha; he wasn’t enlightened from the beginning.

Only through great effort exerted over a long period of time — over many lifetimes, as the Buddhist texts tell us — did he succeed in attaining enlightenment. However, the later tradition clearly considered the Buddha an exceptional human being and elevated him to a special status. Legendary accounts of his life emphasize, for example, his miraculous birth in the Lumbini grove from his mother’s side, the 32 marks of a “great man” that were found on his body, and his ability to work miracles. (See Chapter 3 for more about his birth and the 32 marks.)

The Buddhist spiritual community (Sangha) took great pains to preserve and transmit his teachings as purely as possible so that they could pass from one generation to the next. These extensive teachings were eventually written down, producing a vast collection (or canon) of the Buddha’s discourses (Pali: suttas; Sanskrit: sutras).

Over the centuries, the Sangha also erected burial monuments (stupas) in honor of the major events in their teacher’s life, which allowed later practitioners to make pilgrimage to these honored sites and receive inspiration. (Chapters 8 and 9 have more information on Buddhist devotional practices and rituals.)

Thanks to the efforts of teachers and their disciples, the Buddha’s teachings (known as Dharma) have been handed down from generation to generation up to the present day. That’s why, after 2,500 years, Buddhism is still a living tradition, capable of bestowing peace, happiness, and fulfillment upon anyone who practices it sincerely.

Understanding the Function of Philosophy in Buddhism

Socrates, one of the fathers of Western philosophy, claimed that the unexamined life isn’t worth living, and most Buddhists would certainly agree with him. Because of the importance they place on logical reasoning and rational examination, many Buddhist traditions and schools have a strong philosophical flavor. Others place more emphasis on devotion; still others focus on the direct, nonconceptual investigation and examination that take place during the practice of meditation. (For more on meditation, turn to Chapter 7.)

Like other religions, Buddhism does put forth certain philosophical tenets that sketch out a basic understanding of human existence and serve as guidelines and inspiration for practice and study. Over the centuries, a variety of schools and traditions came into existence, each with its own fairly elaborate and distinct understanding of what the Buddha taught. (For the story of these different traditions, see Chapters 4 and 5.) In addition to the discourses memorized during the founder’s lifetime and recorded after his death, numerous other scriptures emerged many centuries later that were attributed to him.

Despite all its philosophical sophistication, however, Buddhism remains at heart an extremely practical religion. In the Dhammapada (Words on Dhamma), an ancient collection of verses on Buddhist themes, his followers have summarized the teachings as follows:

Abstaining from all evil, undertaking what is skillful, cleansing one’s mind — this is the teaching of the Buddhas. (Verse 183)

Not blaming, not harming, living restrained according to the discipline, moderation in food, seclusion in dwelling, focusing on the highest thoughts — this is the teaching of the Buddhas. (Verse 185)

The Buddha has often been called the Great Physician, for good reason: He avoided abstract speculation and made his chief concern identifying the cause of human suffering and providing ways to eliminate it. (See the sidebar “The parable of the poisoned arrow” for details.) Likewise, his teachings are known as powerful medicine to cure the deeper dissatisfaction that afflicts us all. The Buddha’s first and best-known teaching, the four noble truths (see Chapter 3), outlines the cause of suffering and the means for eliminating it. All subsequent teachings, such as the 12 links of dependent arising (see Chapter 13), merely expand and elaborate upon these fundamental truths.

Reality is constantly changing; as the Greek philosopher Heraclitus said, you can’t step into the same river twice. Success and failure, gain and loss, comfort and discomfort — they all come and go. And you have only limited control over the changes. But you can exert some control over (and ultimately clarify) your chattering, misguided mind, which distorts your perceptions, mightily resists the way things are, and causes you extraordinary stress and suffering in the process.

Happiness is actually quite simple: The secret is to want what you have and not want what you don’t have. Simple though it may be, it’s definitely not easy. Have you ever tried to reign in your restless and unruly mind, even for a moment? Have you ever tried to tame your anger or your jealousy, control your fear, or remain calm and undisturbed in the middle of life’s inevitable ups and downs? If you have, you’ve no doubt discovered how difficult even the simplest self-control or self-awareness can be. To benefit from the medicine the Buddha prescribed, you have to take it — which means that you have to put it into practice for yourself. (See Chapter 17 for ten practical suggestions for putting the Buddha’s teachings to use in your everyday life, and check out Chapter 14 for additional hands-on advice.)

Appreciating Buddhist Practices

Anyone interested in benefiting from the teachings of Buddhism — beyond simply discovering a few interesting facts about it — has to ask, “How do I take this spiritual medicine? How can I apply the teachings of Shakyamuni to my life in such a way to reduce, neutralize, and eventually extinguish my restlessness and dissatisfaction?” The answer is spiritual practice, which takes three forms in Buddhism:

Ethical behavior

Ethical behavior

Meditation (and the wisdom that follows)

Meditation (and the wisdom that follows)

Devotion

Devotion

Living an ethical life

Ethical behavior has been an essential component of the Buddhist spiritual path since the historical Buddha first cautioned his monks and nuns to refrain from certain behaviors because they distracted them from their pursuit of truth. During the Buddha’s lifetime, his followers collected and codified these guidelines, which eventually became the code of discipline (vinaya) that has continued to shape the monastic life for more than 2,500 years. (The term monastic describes both monks and nuns.) From this code emerged briefer guidelines or precepts for lay practitioners, which have remained remarkably similar from tradition to tradition. (For more on ethical behavior, see Chapter 12.)

Far from establishing an absolute standard of right and wrong, ethical guidelines in Buddhism have an entirely practical purpose: to keep practitioners focused on the goal of their practice, which is a liberating insight into the nature of reality. During his 45 years of teaching, the Buddha found that certain activities contributed to increased craving, attachment, restlessness, and dissatisfaction, and led to interpersonal conflict in the community at large. By contrast, other behaviors helped keep the mind peaceful and focused, and contributed to a more supportive atmosphere for spiritual reflection and realization. From these observations, not from any abstract moral point of view, the ethical guidelines emerged.

Examining your life through meditation

In the popular imagination, Buddhism is definitely the religion of meditation. After all, who hasn’t seen statues of the Buddha sitting cross-legged, eyes half closed, deeply immersed in spiritual reflection; or picked up one of the many titles available these days devoted to teaching the basics of Buddhist meditation?

But many people misunderstand the role meditation plays in Buddhism. They falsely assume that you’re meant to withdraw from the affairs of ordinary life into a peaceful, detached, and unaffected inner realm until you no longer feel any emotion or concern about the things that once mattered to you. Nothing could be farther from the truth. (We cover other misconceptions about Buddhism and Buddhist practice in Chapter 16.)

Meditation facilitates this insight by bringing focused, ongoing attention to the workings of your mind and heart. In the early stages of meditation, you spend most of your time being aware of your experience as much as you can — an almost universal Buddhist practice known as mindfulness. You may also cultivate positive, beneficial heart qualities like loving-kindness and compassion or practice visualizations of beneficial figures and energies. But in the end, the goal of all Buddhist meditation is to find out who you are and thereby end your restless seeking and dissatisfaction. (For more on meditation, see Chapter 7.)

Practicing devotion

Devotion has long been a central Buddhist practice. No doubt it began with the spontaneous devotion the Buddha’s own followers felt for their gentle, wise, and compassionate teacher. After his death, followers with a devotional bent directed their reverence toward the enlightened elders of the monastic community and toward the Buddha’s remains, which were preserved in burial monuments known as stupas (see Chapter 4 to find out more about the stupas).

As Buddhism spread throughout the Indian subcontinent and ultimately to other lands, the primary object of devotion became the Three Jewels of the Buddha, Dharma, and Sangha — the great teacher, his teachings, and the spiritual community, which preserves and upholds the teachings. To this day, all Buddhists, both lay and monastic, take refuge in the Three Jewels (also known as the Three Treasures or Triple Gem). (For more on taking refuge, see Chapter 6.)

Eventually, in certain traditions of Buddhism, a host of transcendent figures came to be revered. These figures include other enlightened beings (Buddhas), bodhisattvas (beings striving for enlightenment; see the next section), and celestial figures such as the goddess Tara. (See Chapter 5 for more information on Tara.) By expressing heartfelt devotion to these figures and, in some traditions, by imagining yourself merging with them and assuming their awakened qualities, you can ultimately gain complete enlightenment for the benefit of yourself and others — or so these traditions teach.

Study and reflection help clarify the Buddhist teachings, but devotion forges a heartfelt connection with the tradition, allowing you to express your love and appreciation for the teachers (and teachings) and to experience their love and compassion in return. Even traditions like Zen, which seem to de-emphasize devotion in favor of insight, have a strong devotional undercurrent that gets expressed in rituals and ceremonies but isn’t always visible to newcomers. For lay Buddhist practitioners who may not have the time or inclination to meditate, devotion to the Three Jewels may even become their main practice. In fact, some traditions, like Pure Land Buddhism, are primarily devotional. (For more on the different traditions of Buddhism, including Zen and Pure Land, see Chapter 5.)

Dedicating Your Life to the Benefit of All Beings

Mahayana (“The Great Vehicle” or “Great Path”), a major branch of Buddhism, encourages you to dedicate your spiritual efforts not only to yourself and your loved ones, but also to the benefit and enlightenment of all beings.

Many Buddhist traditions teach their followers to actively cultivate love and compassion for others — not only those they care about, but also those who disturb them or toward whom they may feel hostility (in other words, enemies). In fact, some traditions believe that this dedication to the welfare of all forms the foundation of the spiritual path upon which all other practices are based. Other traditions allow the love and compassion to arise naturally as insight deepens and wisdom ripens, while instructing practitioners to dedicate the merits of their meditations and rituals to all beings.