Chapter 8

A Day in the Life of a Buddhist Practitioner

In This Chapter

Examining the function of monasteries

Examining the function of monasteries

Exploring practice in a Theravada monastery

Exploring practice in a Theravada monastery

Extending Zen to everyday life

Extending Zen to everyday life

Walking in the shoes of a Vajrayana practitioner

Walking in the shoes of a Vajrayana practitioner

Spending a day with followers of the Jodo Shinshu tradition

Spending a day with followers of the Jodo Shinshu tradition

The earlier chapters of this book explain how Buddhism evolved in Asia, grew into various different traditions, and made its way to the West. But how do you actually practice the Buddhist teachings? Sure, many Buddhists meditate, but how exactly do they meditate? What else do they do? How do they spend their time? How do their daily lives differ from yours?

In this chapter, we answer these questions by giving you a firsthand look at Buddhist practice through detailed day-in-the-life accounts of practitioners from four different traditions practiced today in the West. Buddhism comes in many different shapes and sizes, but the one thing that all these traditions have in common — and that makes them quintessentially Buddhist — is the importance they place on basic teachings. Examples of these teachings include the four noble truths and the eightfold path (see Chapter 3), the three marks of existence (impermanence, no-self, and dissatisfaction), and the cultivation of core spiritual qualities such as patience, generosity, loving-kindness, compassion, and insight.

We think that this chapter will bring the religion to life for you and make it more down to earth and immediate than any other chapter in this book.

Surveying the Role of Monasteries in Buddhism

Buddhist monks and nuns have traditionally relinquished their worldly attachments in favor of a simple life devoted to the three trainings of Buddhism (see Chapter 13 for more on the three trainings):

Moral discipline: Ethical conduct

Moral discipline: Ethical conduct

Concentration: Meditation practice

Concentration: Meditation practice

Wisdom: Study of the teachings and direct spiritual insight

Wisdom: Study of the teachings and direct spiritual insight

To support these endeavors, monasteries are generally set apart from the usual commotion of ordinary life. Some monasteries are located in relatively secluded natural settings like forests and mountains; others are situated near or even in villages, towns, and large cities, where they manage to thrive by serving the needs of their inhabitants for quiet contemplation and the needs of lay supporters for spiritual enrichment.

Likewise, Tibetan Buddhist monasteries are often situated near towns or villages. The monasteries draw both their members and their material support from these nearby communities. The exchange works both ways. The laity in both Tibet and Southeast Asia traditionally benefits from the teachings and wise counsel that the monks and nuns offer.

In China, the monastic rules changed to permit monks and nuns to grow their own food and manage their own financial affairs, which allowed them to become more independent of lay supporters. As a result, many monasteries in China, Japan, and Korea became worlds unto themselves, where hundreds or even thousands of monks gathered to study with prominent teachers. Here the eccentric behavior, paradoxical stories (Japanese koan; see the sidebar “Entering the gateless gate: Koan practice in Zen,” in this chapter, for more information), and unique lingo of Zen flourished. (See the section “Growing a Lotus in the Mud: A Day in the Life of a Zen Practitioner,” later in the chapter, for more details.)

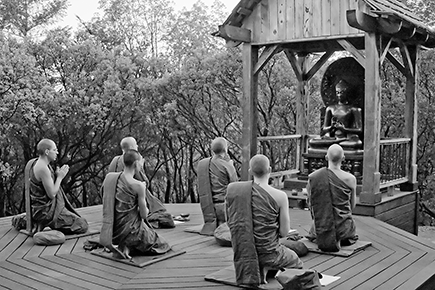

Despite their doctrinal, architectural, and cultural differences, Buddhist monasteries are remarkably alike in the daily practice they foster. Generally, monks and nuns rise early for a day of meditation, chanting, ritual, study, teaching, and work.

Renouncing Worldly Attachments: A Day in the Life of a Western Buddhist Monk

An excellent model of Buddhist monasticism in the West is Abhayagiri Buddhist Monastery, a Theravada monastery situated in Redwood Valley, in the woods of northern California, about a three-hour drive north of San Francisco. It is one of the main monasteries of the worldwide monastic community associated with Ajahn Chah (for the life of Ajahn Chah, see Chapter 15).

Scattered around Abhayagiri’s 280 forested acres are little cabins that house the monastery’s roughly one dozen fully ordained monks and roughly five junior monastics in training. As in the forest tradition of tropical Buddhist countries like Thailand, where Abhayagiri’s two resident teachers (who are included among the monks in residence) began their training, each practitioner has a sparsely furnished cabin for individual meditation and study.

The monastics at Abhayagiri didn’t choose their strict lifestyle on a whim. The 12 fully ordained monks began as novices by adhering to first 8 and then 10 precepts before they committed to the full vinaya (monastic discipline), consisting of 227 rules for restraint of body, speech, and mind. (For more on precepts, check out Chapter 12.) That’s no small task, as you can imagine: Just memorizing and keeping track of all those rules can be a major undertaking! The monks recite the 227 rules on the full moon and new moon days to remind them of their conduct. After confessing any transgressions of minor rules, the monks assemble in close proximity while one monk recites the 13,000 word Patimokkha (Pali: Monks’ Code of Discipline) in the ancient Pali language from memory. Another monk corrects any omissions or mispronunciations. During the 50-minute recitation, the monks may not leave the area nor may anyone else enter or the recitation must begin again. The tradition of reciting the Patimokkha has continued for more than 2,500 years.

Needless to say, these regulations shape monastic life in significant ways. For example, monks must rely on laypeople to deal with monastery finances, and they can’t engage in any project unless the monastery has money on hand to fund it. No movies, no TV, no music, no midnight snacks. Most laypeople can’t even begin to imagine a life of such utter simplicity and discipline! Yet Abhayagiri merely follows the time-honored model for Buddhist monastic life that’s been passed down for thousands of years.

Men visiting for the first time can also arrange to stay at the monastery for up to one week, as long as they agree to follow the schedule and participate in practice. For people who’ve stayed at the monastery before, longer visits are possible. Because the monastery isn’t very old (it was founded in 1996), accommodations are quite limited.

Following a day in the life

As a monastic at Abhayagiri, you follow a schedule that’s typical of Buddhist monasteries the world over. You rise at 4 a.m. — well before the sun — shower, dress, and walk the half-mile from your cabin to gather with your colleagues at the main building for chanting and meditation, which begins at 5. For the first 20 minutes, you chant various scriptures that express your devotion to practice and touch on familiar themes, such as renunciation, loving-kindness, and insight. After taking refuge in the Three Jewels (the Buddha, Dharma, and Sangha), you meditate silently with the other monastics for an hour and then participate in more chanting. (For more on meditation in the Theravada tradition, see Chapter 5.)

Following chores from 6:30 to 7:00 a.m., you meet to discuss the morning work assignments over a light breakfast of cereal and tea. After you determine your responsibilities, you work diligently and mindfully until 10:45 a.m. and then don your robes for the main meal of the day, a formal affair that laypeople offer you. After you and the other monastics help yourselves, the laity take their share and eat with you in silence. Everyone helps wash up and put things away. You then spend the afternoon meditating, studying, hiking, or resting on your own. Remember, you’ve seen the last of solid food until 7 a.m. tomorrow morning — and private stashes are definitely not allowed!

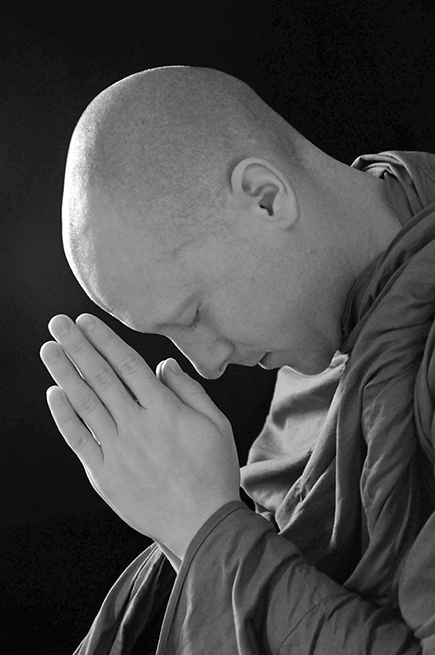

Tea and fruit juice are served in the main hall at 5:30 p.m., followed by a reading of a Buddhist text and discussion at 6:30, and meditation and chanting at 7:30 (see Figure 8-1). Sometime between 9 and 10 p.m. you’re off to your cabin to continue your meditation or to rest in preparation for yet another long day that begins at 4 a.m.

Figure 8-1: Theravada monks chanting together.

Punctuating the calendar with special events

In addition to the regular daily schedule we outline in the preceding section, the lunar quarters (that is, the days corresponding to the quarter, half, and full phases of the moon) and the three-month rainy-season retreat punctuate the monastic calendar.

On the lunar quarters (roughly every week), you observe a kind of Sabbath: You get up when you want, set aside the usual program of meditation and work, and refrain from touching computers or phones. Instead, you go on alms rounds with the other monastics — you walk the streets of the local town in your robes, begging bowl in hand, receiving food from anyone who wishes to offer it (see Figure 8-2). Then you devote the rest of the day to personal practice.

Figure 8-2: Monks on alms round.

In the evening, one of the resident teachers offers a talk that’s open to the lay community. Laypeople who attend and stay the night take the three refuges (the Buddha, Dharma, and Sangha) and commit to following 8 precepts for the duration of their stay — the usual 5 precepts for laypeople (with monastic celibacy in place of the customary precept governing lay sexual behavior), plus 3 precepts with a “twist” of renunciation: no eating after noon, no entertainment or self-adornment, and no lying on a high and luxurious bed (also understood as no overindulging in sleep). (For more on the five basic precepts, see Chapter 12.) Both laity and monastics practice meditation together until 3 a.m., followed by morning chanting. The rest of the day is completely unstructured, and monastics often use it to catch up on their sleep.

On Saturday nights, the monastery hosts a regular talk on a Buddhist theme that draws even more of an outside audience than the lunar gatherings.

Growing a Lotus in the Mud: A Day in the Life of a Zen Practitioner

Zen first gained a foothold in North America around the turn of the last century, but it didn’t achieve widespread popularity until the 1960s and ’70s, when Zen teachers began arriving in larger numbers and young people (discontented with the religion in which they were raised) began seeking alternatives. (Check out Chapter 5 for more details about Zen itself.)

Since that time, the uniquely Western expression of a place for Buddhist practice known as the Zen center has appeared in cities and towns across the North American continent. Like monasteries, Zen centers offer a daily schedule of meditation, ritual, and work combined with regular lectures and study groups. But unlike their monastic counterparts, the centers adapt their approach to the needs of busy lay practitioners who must balance the demands of family life, career, and other worldly obligations with their spiritual involvement.

Though Zen temples in Japan and Korea have lay meditation groups, nothing quite like the Zen center has ever emerged in Asia. The reason is quite simple: Lay practitioners who fervently commit themselves to Buddhist practice are far more common in the West than in Asia, where serious practitioners generally take monastic or priestly vows. Maybe this phenomenon is the result of the Western belief that we can have it all: spiritual enlightenment and worldly accomplishment. (The Judeo-Christian ethic so prominent in North America teaches that daily life is inseparable from spiritual practice.) Or perhaps Westerners simply have no choice: In a culture where the monastic style of practice isn’t widely acknowledged or supported, practitioners have to make a living while studying the teachings.

Just as the most beautiful flower, the lotus, grows in muddy water, so the lay practitioner can find clarity and compassion in the turmoil of daily life.

Though Zen centers form the spiritual hub of their respective communities, members continue their practice throughout the day by applying meditative awareness to every activity.

Following a day in the life

As a Zen practitioner, you’re encouraged to practice zazen on your own, but sitting with other members of the Sangha (spiritual community) is considered particularly effective and favorable. (Sangha is regarded as one of the Three Jewels of Buddhism, along with the Buddha and Dharma.) So, most Zen centers offer daily group meditations — usually in the early morning before work and in the evening after work. Depending on how much time you have to spare and the schedule at your local center, you can spend from one to three hours practicing Zen with others.

At zendos (meditation halls connected with Zen centers) across the country, meditators repeat the familiar ritual of gathering in the predawn dark to practice together. (Though Zen is best known in the West in its Japanese form, and we use Japanese terms throughout this section, remember that Zen began in China and that Korean and Vietnamese teachers introduced it to the West.)

After entering the zendo, you bow respectfully to your cushion or chair and then position yourself in preparation for zazen. Even in its Western incarnation, Zen is notorious for its careful attention to traditional formalities. Meditation begins with the sounding of a bell or gong and generally continues in silence for 30 to 40 minutes. Depending on the school of Zen to which you belong (for more on Zen schools, see Chapter 5) and the maturity of your practice, you may spend your time following your breaths, just sitting (a more advanced technique involving mindful attention in the present without a particular object of focus), or attempting to solve a koan (a paradoxical story; see the sidebar “Entering the gateless gate: Koan practice in Zen,” for more details). Whatever your technique, you’re encouraged to sit with an erect spine and wholehearted attention.

Between meditation periods, you may form a line with other practitioners and meditate while walking mindfully around the hall together. Following a period or two of sitting, everyone generally chants some version of the four bodhisattva vows, which we mention in Chapter 6:

Beings are numberless; I vow to save them.

Beings are numberless; I vow to save them.

Mental defilements are inexhaustible; I vow to put an end to them.

Mental defilements are inexhaustible; I vow to put an end to them.

The teachings are boundless; I vow to master them.

The teachings are boundless; I vow to master them.

The Buddha’s way is unsurpassable; I vow to attain it.

The Buddha’s way is unsurpassable; I vow to attain it.

During the service that follows meditation, you bow deeply three or nine times to the altar (which usually features a statue of Shakyamuni Buddha or Manjushri Bodhisattva, flowers, candles, and incense) and chant one or more important wisdom texts, which generally include the Heart Sutra. These texts offer concise reminders of the core teachings of Zen, and the altar represents the Three Jewels of Buddhism, the ultimate objects of reverence and refuge: the Buddha, Dharma, and Sangha.

When you finish your morning meditation, your Zen practice has just begun. Throughout the day, you have constant opportunities to be mindful — not only of what you’re doing or what’s happening around you, but also of the thoughts, emotions, and reactive patterns that life events trigger. Whether on the cushion or on the go, this steady, inclusive, mindful awareness lies at the heart of Buddhist practice in every tradition.

When you get behind the wheel of your car, for example, you can stop to sense the contact of your back against the seat, listen to the sound of the engine as it starts, pay attention to the condition of the road, and notice the state of your mind and heart as you head down the street. When you stop at a traffic light, you can be aware of the impatience you feel as you wait for the light to change, the sounds of the traffic around you, the warmth of the sun through the window, and so on. As you can see, every moment, from morning to night, provides an opportunity to practice.

In addition to meditation and service, most Zen centers offer weekly talks by the resident teacher and regular opportunities for private interviews with the teacher to discuss your practice. These face-to-face encounters may touch on any area of practice, including work, relationships, sitting meditation, and formal koan study. The Zen master isn’t a guru endowed with special powers. Practitioners regard the master as a skilled guide and an exemplar of the enlightened way of life.

If you’re a serious Zen student but can’t practice at the center, because you’re sick, you live too far away, or you can’t arrange your calendar to include it, you can generally follow some version of this daily schedule on your own by sitting in the morning and again, if possible, in the evening. Then to energize and deepen your practice, you can make it a point to attend one or more intensive retreats each year.

Attending silent retreats

Most Zen centers in the West offer regular one- to seven-day retreats (Japanese: sesshin) featuring as many as a dozen periods of meditation each day, morning and evening services, daily talks on Buddhist themes, and interviews. (Korean Zen also offers retreats devoted primarily to chanting and bowing.) As a rule, these rigorous retreats are held in silence and offer an opportunity to hone your concentration, deepen your insight into the fundamental truths of Buddhism, and possibly catch a glimpse of your essential Buddha nature (an experience of awakening known in Japanese as kensho or satori). Retreats of more than one or two days are generally residential, though some centers allow you to attend part time while continuing your everyday life.

In keeping with the Mahayana spirit of general equality among monastic and lay practitioners, larger Zen centers often have country retreat centers that provide monastic accommodations and training for both ordained monks and nuns and lay practitioners. For example, the San Francisco Zen Center — which describes itself as one of the largest Buddhist Sanghas outside of Asia, a diverse community of priests, laypeople, teachers, and students — includes three separate facilities:

City Center: This facility serves urban members.

City Center: This facility serves urban members.

Green Gulch Farm: This location combines a suburban practice center and a working organic farm.

Green Gulch Farm: This location combines a suburban practice center and a working organic farm.

Tassajara Zen Mountain Center: This facility is the oldest Soto Zen monastery in the United States. During the winter months, experienced Zen students from all over the world gather to participate in the fall and winter three-month practice periods. September and April are community months in which volunteers can help the monks prepare for the transitions to and from secluded monastic practice.

Tassajara Zen Mountain Center: This facility is the oldest Soto Zen monastery in the United States. During the winter months, experienced Zen students from all over the world gather to participate in the fall and winter three-month practice periods. September and April are community months in which volunteers can help the monks prepare for the transitions to and from secluded monastic practice.

From late spring to early fall, Tassajara opens its gates, meditation hall, cabins, wilderness trails, and hot springs to guests, work students, and retreatants who participate in varied offerings and opportunities, ranging from relaxed day trips and vacations to extended monastic training.

All three facilities offer regular residential retreats, but the program at Tassajara is particularly intensive.

Gathering for special events

Every Zen center has its own calendar of special ceremonies and events that punctuate the year. At the San Francisco Zen Center, for example, these events include the following:

Memorial ceremonies honoring the founder, Shunryu Suzuki Roshi

Memorial ceremonies honoring the founder, Shunryu Suzuki Roshi

Monthly full moon bodhisattva ceremonies

Monthly full moon bodhisattva ceremonies

Solstice and equinox ceremonies

Solstice and equinox ceremonies

New Year’s Eve and New Year’s Day celebrations

New Year’s Eve and New Year’s Day celebrations

Annual Martin Luther King, Jr., ceremony

Annual Martin Luther King, Jr., ceremony

The Buddha’s birthday in April and enlightenment day in December

The Buddha’s birthday in April and enlightenment day in December

Annual ceremonies honoring Bodhidharma, the founder of Chan in China, and Eihei Dogen, the founder of Zen in Japan.

Annual ceremonies honoring Bodhidharma, the founder of Chan in China, and Eihei Dogen, the founder of Zen in Japan.

Many centers also offer weekly study groups focusing on Buddhist scriptures and the teachings of the great Zen masters. Zen communities, like churches of other denominations, also sponsor social gatherings where members get to mingle and enjoy one another’s company.

Devoting Yourself to the Three Jewels: A Day in the Life of a Vajrayana Practitioner

In addition to North American converts to Buddhism, the continent has many thousands of ethnic practitioners who carried their Buddhist practice with them from Asia or learned it from their Asian parents or grandparents.

Some of these Asian American Buddhists are monks and nuns (many come from Southeast Asia) who have transplanted traditional forms and practices to Western soil. But most folks are laypeople for whom Buddhism is often more a matter of devotion and ritual than meditation and study.

For these Asian Americans, being a Buddhist may involve the following actions:

Going to the temple on the weekend to listen to a sermon

Going to the temple on the weekend to listen to a sermon

Chanting Buddhist texts in the language of their homeland

Chanting Buddhist texts in the language of their homeland

Participating in the special ceremonies that mark the changing of the seasons and the turning of the year

Participating in the special ceremonies that mark the changing of the seasons and the turning of the year

Sharing food at temple gatherings

Sharing food at temple gatherings

Helping fellow temple members in times of need

Helping fellow temple members in times of need

As an ethnic lay practitioner of Tibetan Vajrayana Buddhism now living in the West, you may engage in some or all of the following daily practices (for more info on the Vajrayana Buddhism of Tibet, see Chapter 5):

You rise early, between 5 and 6 a.m., to begin your day with meditation.

You rise early, between 5 and 6 a.m., to begin your day with meditation.

You walk around (circumambulate) your house, which holds a sacred shrine containing statues, scrolls, and other ritual objects.

You walk around (circumambulate) your house, which holds a sacred shrine containing statues, scrolls, and other ritual objects.

As you walk, you finger your mala (a string of beads, a rosary) while chanting a sacred mantra such as Om mani-padme hum (the famous mantra of Avalokiteshvara/Chenrezig, the bodhisattva of compassion) or the longer mantra of Vajrasattva, the bodhisattva of clarity and purification.

As you walk, you finger your mala (a string of beads, a rosary) while chanting a sacred mantra such as Om mani-padme hum (the famous mantra of Avalokiteshvara/Chenrezig, the bodhisattva of compassion) or the longer mantra of Vajrasattva, the bodhisattva of clarity and purification.

After cleaning your shrine, you offer 108 prostrations (see Figure 8-3 to get a glimpse of how they’re done) as an expression of your devotion to and refuge in the Three Jewels (the Buddha, Dharma, and Sangha).

After cleaning your shrine, you offer 108 prostrations (see Figure 8-3 to get a glimpse of how they’re done) as an expression of your devotion to and refuge in the Three Jewels (the Buddha, Dharma, and Sangha).

You engage in a particular practice your teacher has given you, often a visualization of a particular deity accompanied by chanting, prayer, and prostrations.

You engage in a particular practice your teacher has given you, often a visualization of a particular deity accompanied by chanting, prayer, and prostrations.

As you go about your day, you chant Om mani-padme hum, either aloud or silently to yourself, while cultivating the qualities of compassion and loving-kindness for all beings.

As you go about your day, you chant Om mani-padme hum, either aloud or silently to yourself, while cultivating the qualities of compassion and loving-kindness for all beings.

You spend an hour or two in the evening studying certain special teachings recommended by your teacher.

You spend an hour or two in the evening studying certain special teachings recommended by your teacher.

Before you go to sleep, you make offerings of incense and candles at your altar, meditate, do additional prostrations, and recite long-life prayers for your teacher(s).

Before you go to sleep, you make offerings of incense and candles at your altar, meditate, do additional prostrations, and recite long-life prayers for your teacher(s).

As you can see, the life of a traditional Vajrayana lay practitioner is permeated by spiritual practice. Of course, some people are more devoted than others, and young people are more inclined to diverge from the traditional ways of their parents. But in general, Tibetan culture, even in exile, is filled with strong Buddhist values that often express themselves in dedicated practice.

Figure 8-3: Performing full prostrations in the Tibetan style.

Trusting the Mind of Amida: A Day in the Life of a Pure Land Buddhist

Unlike most other forms of Buddhism that recommend spiritual practices (particularly meditation) as the means to attain enlightenment, Jodo Shinshu (a popular Japanese Pure Land school whose name means “The True Pure Land school”) teaches its followers not to rely on their own personal practice. Instead, Jodo Shinshu instructs practitioners to rely on the “great practice” of Amida Buddha himself, who took a vow to lead all beings to enlightenment. (Check out Chapter 5 for a more in-depth discussion of Jodo Shinshu and the many facets of Pure Land Buddhism.)

As a Jodo Shinshu follower, you’re taught that entry to the Pure Land (which is more a state of mind than a future realm) occurs through other power (that is, the power of what Amida Buddha has already accomplished) rather than through whatever you yourself may try to do. Jodo Shinshu understands Amida (or Amitabha, in Sanskrit) to be an expression of the infinite, formless, life-giving Oneness that, out of deep compassion, took form to establish the Pure Land and lead beings to Buddhahood.

Shinran himself left the monastic life to marry and raise a family because he felt that making the Buddhist teachings more accessible to laypeople was extremely important. In this spirit, Jodo Shinshu emphasizes that everyday life in the context of family and friends is the perfect setting for spiritual practice. As a result, Jodo Shinshu followers lead ordinary lives that differ little from those of their non-Buddhist counterparts, except that they attempt to put into practice basic Buddhist principles, like patience, generosity, kindness, and equanimity. They get up and go to work, make dinner, and help their kids with their homework just like everyone else.

Without prescribed techniques, practice becomes a matter of attitude rather than activity. At the same time, followers of Jodo Shinshu can engage in any traditional Buddhist practice, such as meditation or the practice of mindfulness of the Buddha (nembutsu) by chanting the mantra Namu amida butsu (“Homage to Amida Buddha”), as long as they do it as an expression of their gratitude for the gift of Amida’s grace (not as a means to attain enlightenment).

On Sunday mornings, followers generally gather at their local temple to listen to a talk on a Buddhist theme while their children attend the Buddhist version of Sunday school — a short sermon followed by an hour-long class about Buddhist values. If they’re strongly motivated, adult members may join a discussion or study group focusing on Jodo Shinshu themes.

Seasonal holidays also bring the community together to celebrate special occasions like the Buddha’s birth, enlightenment days, the vernal and autumnal equinoxes, and a summer ceremony honoring the spirits of departed ancestors. For many practitioners, the temple (like the local church or synagogue) is the focal point of social and community life. Temples often offer classes in martial arts, flower arranging, taiko drumming, and Japanese language that instill Buddhist principles and Japanese culture and values.