Chapter 9

Walking in the Buddha’s Footsteps

In This Chapter

Playing the role of a pilgrim

Playing the role of a pilgrim

Mapping out the major sites of Buddhist pilgrimage

Mapping out the major sites of Buddhist pilgrimage

Exploring what happens during a pilgrimage

Exploring what happens during a pilgrimage

Two thousand five hundred years ago, Shakyamuni Buddha inspired his original disciples and their daily spiritual practice by delivering his teachings. His enlightened presence profoundly affected most of the people he met. Even when people came to the Buddha in an agitated state of mind, they often discovered that his peaceful demeanor automatically calmed them.

But what about future generations of Buddhists who don’t have the opportunity of meeting Shakyamuni in person? Well, they can receive inspiration for their practice by visiting the places where he stayed during his lifetime. The custom of making a pilgrimage to the places Shakyamuni blessed by his presence has a long tradition that continues today. In this chapter, we talk about these places and some of the practices Buddhists perform while visiting them.

Visiting the Primary Places of Pilgrimage

Pilgrimage is the practice of visiting a site of religious significance to fulfill a spiritual longing or duty or to receive blessings or inspiration. Hundreds of millions of people around the world perform pilgrimage, one of the most universal of religious practices. Muslims consider it their duty to make a pilgrimage to the holy city of Mecca at least once during their lifetime. Many Jews journey to Jerusalem to pray at the Western Wall and view the great biblical battle sites. Christians may trace the footsteps of Jesus from Bethlehem to Golgotha or visit the sacred places where great saints performed miracles.

Four pilgrimage sites are of major significance for Buddhists:

Lumbini: Site of the Buddha’s birth

Lumbini: Site of the Buddha’s birth

Bodh Gaya: Site where he attained full enlightenment

Bodh Gaya: Site where he attained full enlightenment

Sarnath: Site of his first discourse

Sarnath: Site of his first discourse

Kushinagar: Site where he died

Kushinagar: Site where he died

According to some Buddhist traditions, visiting these and other important sites (while thinking about the events that occurred there) enables an individual of faith to accumulate merit and/or purify negative karma accumulated in past lives (see Chapter 12 for more on the concept of karma).

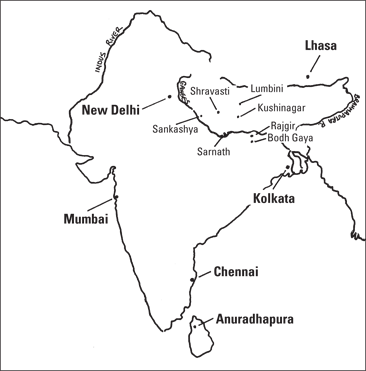

After the Buddha’s death, his teachings flourished on the Indian subcontinent for more than a thousand years, and these pilgrimage sites grew to be important Buddhist centers (see Figure 9-1 for a map of these sites). But eventually, Buddhism began to die out in India. By the 13th century, it had virtually disappeared from the subcontinent, and many of the sites suffered from neglect and fell into ruin.

Figure 9-1: Major Buddhist pilgrimage sites in northern India and Nepal.

By the time Buddhism disappeared in the country of its birth, it had already taken root in other Asian cultures (see Chapter 5 for more on the spread of Buddhism). So when the job of reestablishing these sacred Indian sites kicked into high gear in the 19th century, many Buddhists — and Western archeologists — were up to the task. As a result of their ongoing efforts, present-day pilgrims can once again visit these sites and receive inspiration for themselves.

The next few sections take a closer look at each of the four sites.

Lumbini: A visit to the Buddha’s birthplace

A good place to begin a Buddhist pilgrimage is Lumbini, which is now in Nepal near the border with India. You can get to it relatively easily by catching a train to the North Indian city of Gorakhpur and then switching to a bus that takes you across the border. (Gorakhpur is also the jumping-off point on your way to Kushinagar, site of the Buddha’s death, described later in the chapter.)

The area north of modern Gorakhpur was once part of the kingdom of the Shakyas, the clan into which the Buddha was born, and Lumbini itself was his actual birthplace (see Chapter 3 for more about the Buddha’s life story). Buddhist pilgrims from all over the world visit Lumbini to honor Shakyamuni, based on whose teachings Buddhism developed, and express their devotion and gratitude to him for entering this world and blazing the path leading to lasting peace, happiness, and spiritual fulfillment.

When Buddhists visit Lumbini (and the other major pilgrimage sites), they express their devotion in different ways. In the case of Lumbini, they head to the Mayadevi Temple (see Figure 9-2) purporting to encircle the exact spot where Shakyamuni was born. Adjacent to the temple is the sacred pond where Shakyamuni’s mother Maya is supposed to have bathed before giving birth and where Shakyamuni is said to have been bathed after he was born. Pilgrims leave offerings at the temple as a sign of their respect. The offerings typically consist of flowers, candles, and incense. (You don’t have to worry about finding the items you want to offer; Buddhist and Hindu pilgrimage sites throughout India and the surrounding area are filled with small outdoor shops selling everything you may need.)

Figure 9-2: Mayadevi Temple, Lumbini, with the sacred pond.

These pilgrimage sites are also excellent places to engage in whatever formal practices you’re accustomed to performing (see Chapter 8 for some of the practices Buddhists from different traditions commonly engage in). For example, many people report that their meditations are more powerful at sites like Lumbini than they are at home, as if the place itself, blessed by the Buddha and other great practitioners of the past, gives added strength to their spiritual endeavors.

You may wonder how people know that this village is really the site of the Buddha’s birth. Even though it fell into disrepair a long time ago, experts have been reasonably certain about the location of Lumbini since the end of the 19th century. At that time, archeologists uncovered an important piece of evidence — an inscribed pillar, left behind more than 2,000 years earlier by one of the most influential of all Buddhist pilgrims: the great Emperor Ashoka. (For more about Ashoka, one of the most important figures in Buddhist history, see Chapter 4.)

Bodh Gaya: Place of enlightenment

If Buddhists have a Mecca, it’s Bodh Gaya, the site of the magnificent Mahabodhi Temple (see Figure 9-3). (Incidentally, mahabodhi means “great enlightenment” in Sanskrit.) The temple stands just east of the famous Bodhi tree (for more on the Bodhi tree, see Chapters 3 and 4). This temple (which is actually a large stupa, a monument housing relics of the Buddha) marks the single most important spot in the entire Buddhist world: the place where Shakyamuni is believed to have attained full enlightenment. The so-called “diamond seat,” where the Buddha is supposed to have meditated, is located between the Mahabodhi Temple and the Bodhi tree (see Chapter 1).

Figure 9-3: The Mahabodhi Temple in Bodh Gaya.

Most pilgrims reach the town of Bodh Gaya by first taking a train to the city of Gaya (where you can find one of Hinduism’s most holy shrines) and then continuing south 13 kilometers by taxi, auto-rickshaw, or — if you’re fond of crowded conditions — bus. The road between Gaya and Bodh Gaya runs alongside a riverbed that’s dry for much of the year — especially in winter. Winter is the height of the pilgrimage season here, and with good reason. Even though many Buddhists celebrate the anniversary of the Buddha’s enlightenment in May or June, you may not be comfortable visiting Bodh Gaya at that time of year — unless you’re a big fan of temperatures that regularly reach 120 degrees Fahrenheit and more.

Well before you enter Bodh Gaya, you can see the top of the “Great Stupa” (as the Mahabodhi Temple is often called) towering 55 meters above the surrounding plain. No one knows the age of the structure for certain, but it is likely to date from the fifth or sixth century CE.

Taking a sacred walk

The circumambulation of sacred objects has become a revered practice in Hindu, Jain, and certain Buddhist traditions. Pilgrims walk around a statue, shrine or another sacred object in a clockwise direction, always keeping the object of reverence on the right side. Buddhists come from all over the world to circumambulate the Mahabodhi Temple and pay their respects at the site of one of the defining moments of Buddhist history. At the height of the pilgrimage season, you can see Buddhists performing circumambulations at every hour of the day and night. And if you happen to be there on an evening of a full moon — when the power of such practices is thought to be much greater — you can easily be swept up in the swirling mass of humanity that seems to flood the area.

Feeling the Buddha’s influence

The area around the Mahabodhi Temple contains many smaller stupas and shrines, some of which mark places where the Buddha is believed to have stayed during the seven weeks immediately after he attained enlightenment. Many pilgrims make circle upon circle as they walk from one of these sacred structures to the other. Throughout the extensive grounds, pilgrims take part in other religious practices as well, such as reciting prayers, making offerings, or simply sitting in quiet meditation. A favorite place for this last activity is a small room on the ground floor of the Mahabodhi Temple that’s dominated by an ancient and particularly beautiful statue of the Buddha. Sitting there in front of this blessed image in the very heart of the Great Stupa gives you the feeling of being in the presence of the Buddha himself.

Buddhists from around the world have taken advantage of this special place by building temples in the area surrounding the Mahabodhi grounds. The number of temples has grown significantly in recent years. In fact, certain portions of Bodh Gaya now look like a Buddhist theme park, filled with examples of the most diverse religious architecture Asia has to offer.

Venturing to other notable sites

Not far from Bodh Gaya are other pilgrimage sites that, although not nearly as built up as those within Bodh Gaya itself, are still of great interest. For example, on the other side of the dry riverbed are the spots where the Buddha is believed to have spent six years fasting before his enlightenment and where he is said to have broken his fast by accepting Sujata’s offering (see Chapter 3). You can also find caves used by some of the great meditators of the past in the surrounding hills.

Sarnath: The first teaching

When the Buddha decided the time was ripe to share the fruits of the enlightenment he’d achieved, he traveled to the Deer Park in Sarnath to teach his former companions. Sarnath is on the outskirts of Varanasi (or Benares, as it was formerly called in the West). Even in the time of the Buddha, Varanasi was already an ancient holy site. Varanasi is probably most famous as the place where Hindus come to cleanse themselves of impurities by bathing in the sacred waters of the Ganges River and to cremate the bodies of their loved ones.

But Buddhist pilgrims turn their attention a little to the north of Varanasi, to Sarnath, where the Buddha first turned the wheel of Dharma by teaching the four noble truths that form the basis of all his subsequent teachings (as we explain in Chapter 3). Buddhists around the world commemorate this event because the Buddha’s teachings are considered his true legacy.

You can find all the sites associated with the Buddha’s first teaching within a relatively new park in Sarnath. Two stupas once stood on this site. The one built by King Ashoka was destroyed in the 18th century, but the Dhamekh(a) stupa of the 6th century still remains (see Figure 9-4). During the period when Buddhism declined in India, many precious works of art were lost. Fortunately, a number of these items have since been unearthed and are currently on exhibit in Sarnath’s small but excellent museum. Among the items on display is the famous Lion Capital, from the pillar Ashoka erected here. This image is now used as the national emblem of the Republic of India and appears on its currency; the wheel design also located on the capital is reproduced on India’s national flag.

Figure 9-4: The Dhamekh(a) stupa in Sarnath, site of the Buddha’s first teaching.

Buddhists from various Asian countries have built temples in Sarnath as they’ve done in Bodh Gaya (check out the “Bodh Gaya: Place of enlightenment” section, earlier in this chapter). The tradition of learning that flourished in Sarnath during the early years of Buddhism has also been reintroduced. The Central Institute of Higher Tibetan Studies, its library, and publishing venture are all relatively new expressions of this tradition. In these and other ways, concerned individuals and groups have rekindled the Dharma flame originally lit at Sarnath.

Kushinagar: The Buddha’s death

The fourth major pilgrimage site is Kushinagar, where the Buddha died.

According to tradition, sometime before he died, the Buddha announced to his closest attendant, Ananda, that the time for him to enter the state of parinirvana, or final liberation, was approaching. According to popular belief, Buddha lay down on his right side in what’s known as the lion posture, entered progressively deeper states of meditation, and then died. Afterward, his body was cremated.

Although archeological evidence proves that numerous Buddhist monasteries once stood in Kushinagar and that King Ashoka built several stupas there, very little remains today. However, an ancient statue of the Buddha reclining in the lion posture has been restored. This statue, the Parinirvana Temple and Nirvana Stupa are among the monuments to mark the Buddha’s final resting place and cremation. Many pilgrims report that Kushinagar possesses an extraordinarily calm atmosphere, making it a perfect site for peaceful meditation.

Seeing Other Important Pilgrimage Sites

Four other places of Buddhist pilgrimage in northern India deserve at least a brief mention:

Rajgir: The capital city of the kingdom of Magadha, whose king, Bimbisara, was a disciple of the Buddha

Rajgir: The capital city of the kingdom of Magadha, whose king, Bimbisara, was a disciple of the Buddha

Shravasti: The area where the Buddha spent many rainy seasons

Shravasti: The area where the Buddha spent many rainy seasons

Sankashya: The place where the Buddha is believed to have returned to Earth after teaching his mother in heaven

Sankashya: The place where the Buddha is believed to have returned to Earth after teaching his mother in heaven

Nalanda: The site of a world-renowned monastic university

Nalanda: The site of a world-renowned monastic university

The next few sections take a closer look at each of these sites.

Rajgir

When the Buddha left his father’s palace in search of an end to all suffering (see Chapter 3 for more details), he passed through the kingdom of Magadha, where he caught the eye of King Bimbisara. The Buddha promised the king that, if his search was successful, he would return to Rajgir and teach him.

As a result of this promise, Rajgir became one of the most important places where the Buddha turned the wheel of Dharma. On a hill called Vulture’s Peak, just beyond the city, the Buddha delivered some of his most important teachings (see Figure 9-5).

Figure 9-5: The Vulture’s Peak at Rajgir.

Rajgir is an ancient city, and visitors can still see and use the baths where the Buddha supposedly refreshed himself. They can also view the remains of the parks given to the Buddha by his first patrons for the monastic community to use. Many important events in Buddhism’s early history took place in Rajgir, including the gathering of the First Council, where 500 monks collected and compiled Shakyamuni’s teachings. (To find out more about the historical development of Buddhism, including the meeting of the First Council, check out Chapter 4.)

For many of today’s visitors to Rajgir, the most impressive sight is a large stupa, visible for many miles around, that Japanese Buddhists constructed on the top of the hill above Vulture’s Peak. This stupa, radiantly white in the glare of the sun, is adorned on four sides with gold images illustrating the four major events in the Buddha’s life mentioned throughout this chapter: his birth, enlightenment, first turning of the wheel of Dharma, and entrance into parinirvana.

Shravasti

Even today, the monsoon season in India (which lasts from about June to September in the north) makes travel difficult. During the time of the Buddha, before paved roads existed, getting around must’ve been close to impossible. So the Buddha remained in retreat with his disciples during this time, and he spent his first rainy season in Rajgir. But for many rainy seasons after that, he and his followers gathered at Shravasti, where a wealthy merchant had invited them to stay. The area became known as the Jetavana Grove, an often-mentioned site of the Buddha’s teachings.

Many events in the life of the Buddha are associated with Shravasti, but the one that catches the imagination is the legend of the Buddha’s display of miraculous powers, the “great miracle of Shravasti.” Generally, Buddhists downplay the importance of the extraordinary powers that sometimes result from deep meditation. They’re generally ignored or kept hidden unless an overwhelming purpose for displaying them arises. These powers aren’t troublesome, but they can distract the practitioner from the true aim of meditation — spiritual realization.

According to the legend, the Buddha had good reason to display his miraculous abilities in Shravasti. During the years he traveled across India giving teachings, teachers from opposing philosophical schools often challenged him to debate points of doctrine and to engage in contests of miraculous abilities. For the first couple decades after his enlightenment, the Buddha consistently declined to take up these challenges. But eventually, he chose to accept the challenge because he realized that it would enable him to bring a large number of people into the Dharma fold. So the Buddha announced that he would meet with other spiritual teachers and engage in the contests they desired, with the understanding that whoever lost would, along with his followers, become the disciple of the winner.

You can probably guess how this contest turned out. The Buddha overwhelmed the crowds who’d gathered with a pyrotechnical display of his magical abilities — from flying through the air to producing countless manifestations of himself so that the sky was filled with Buddhas! The defeated rivals and their followers developed great faith in the Buddha, who then gave them his teachings. The whole event is still commemorated in various Buddhist lands. In Tibet, for example, Lama Tsongkhapa (whom we mention in Chapters 3 and 15 as the guru of the First Dalai Lama) instituted a 15-day prayer festival in Lhasa to mark the New Year and recall the events at Shravasti.

Sankashya

Sankashya, identified with the village of Basantpur in the Farrukhabad district of today’s state of Uttar Pradesh, is the site where, according to legendary accounts, the Buddha descended after visiting his mother in heaven, where she had taken rebirth. As we explain in Chapter 3, the Buddha’s mother, Queen Maya, died within a week of giving birth to him, and she was reborn in heaven. To repay her kindness, the Buddha ascended to heaven and gave her teachings on the topic of higher knowledge (abhidharma; see Chapter 4 for more on this topic). Sankashya is the spot where the Buddha, flanked by the great gods of ancient India, Indra and Brahma, is believed to have returned to Earth after this special teaching.

Nalanda

Last on the list of pilgrimage sites is Nalanda, which is located near Rajgir. At one time, Nalanda was the site of a mango grove where the Buddha often stayed. But it became famous several centuries after the time of the Buddha when an influential monastic university grew up there. This university shaped the development of Buddhist thought and practice in India and around the world. Nalanda was one of the major seats of learning in Asia, attracting Buddhists and non-Buddhists alike, and it remained influential until its destruction at the end of the 12th century.

Even though it now lies in ruins, the extensive excavations at Nalanda give visitors an idea of the huge size of this and other Buddhist monasteries of the time, as well as the enormous impact they must have had on Indian culture. The list of individuals who studied and taught at Nalanda includes many of the most revered Indian Buddhist masters, many of whose works are still studied today.

Going on Pilgrimage Today

Although Shakyamuni Buddha spent his entire life in the northern portion of the Indian subcontinent, it isn’t the only part of the world where a person can go on Buddhist pilgrimage. As Buddhism spread throughout India and beyond (see Chapters 4 and 5), many different places became associated with important teachers and famous meditators, and these, too, became destinations of the devout (or merely curious) Buddhist pilgrim.

We can’t possibly do justice to the large number of Buddhist holy places that pilgrims still visit to this day. Even in a relatively small area like the Kathmandu Valley of Nepal, you could spend months going from one sacred spot to another and still not see them all. The following short list, therefore, is just a sampling of the rich treasure of sites you may consider visiting some day:

Temple of the Sacred Tooth, in Kandy, Sri Lanka (formerly Ceylon): A tooth said to belong to Shakyamuni Buddha is enshrined here. On the full moon of August every year, a magnificent festival is held — complete with elephants — in its honor.

Temple of the Sacred Tooth, in Kandy, Sri Lanka (formerly Ceylon): A tooth said to belong to Shakyamuni Buddha is enshrined here. On the full moon of August every year, a magnificent festival is held — complete with elephants — in its honor.

Shwedagon Pagoda, in Yangon (formerly known as Rangoon), Myanmar (formerly Burma): This world-famous golden monument, housing eight of the Buddha’s hairs, rises over 320 feet and is the most venerated of all Burmese Buddhist shrines.

Shwedagon Pagoda, in Yangon (formerly known as Rangoon), Myanmar (formerly Burma): This world-famous golden monument, housing eight of the Buddha’s hairs, rises over 320 feet and is the most venerated of all Burmese Buddhist shrines.

Mount Kailash, in western Tibet: This remote, pyramid-shaped snow mountain is a sacred site for Hindus and Buddhist pilgrims. It is considered the home of Hindu and Buddhist deities. Pilgrims hardy enough to make the rugged journey here and complete the circuit around this sacred mountain report this pilgrimage to be a high point (literally as well as figuratively) of their lives.

Mount Kailash, in western Tibet: This remote, pyramid-shaped snow mountain is a sacred site for Hindus and Buddhist pilgrims. It is considered the home of Hindu and Buddhist deities. Pilgrims hardy enough to make the rugged journey here and complete the circuit around this sacred mountain report this pilgrimage to be a high point (literally as well as figuratively) of their lives.

Borobudur, on the island of Java, Indonesia: This enormous structure of many terraces — built in the shape of a sacred diagram (mandala) — is located on a hill and filled with hundreds of Buddha statues and stupas.

Borobudur, on the island of Java, Indonesia: This enormous structure of many terraces — built in the shape of a sacred diagram (mandala) — is located on a hill and filled with hundreds of Buddha statues and stupas.

The 88 Sacred Places of Shikoku, Japan: The great Japanese Buddhist master Kukai (774–835 CE) is believed to have established a pilgrimage route around the beautiful and mountainous island of Shikoku, and people of all ages and nationalities come to complete all or part of the circuit. (For Kukai, also known as Kobo Daishi, see Chapter 5.)

The 88 Sacred Places of Shikoku, Japan: The great Japanese Buddhist master Kukai (774–835 CE) is believed to have established a pilgrimage route around the beautiful and mountainous island of Shikoku, and people of all ages and nationalities come to complete all or part of the circuit. (For Kukai, also known as Kobo Daishi, see Chapter 5.)

Almost anywhere: Inspired by Kukai’s example, a number of modern-day Buddhists have established pilgrimage routes through scenic areas of their own countries. Some of the Beat poets associated with California, for example, made a practice of walking around Mount Tamalpais, a mountain north of San Francisco sacred to Native Americans. This practice continues today, and with the founding of an ever-growing number of monasteries, retreat centers, and temples in the West, trails linking them to Buddhist pilgrimage routes are bound to grow.

Almost anywhere: Inspired by Kukai’s example, a number of modern-day Buddhists have established pilgrimage routes through scenic areas of their own countries. Some of the Beat poets associated with California, for example, made a practice of walking around Mount Tamalpais, a mountain north of San Francisco sacred to Native Americans. This practice continues today, and with the founding of an ever-growing number of monasteries, retreat centers, and temples in the West, trails linking them to Buddhist pilgrimage routes are bound to grow.