Chapter 10

What Is Enlightenment, Anyway?

In This Chapter

Figuring out what makes enlightenment so special

Figuring out what makes enlightenment so special

Walking along the Theravada path to nirvana

Walking along the Theravada path to nirvana

Exploring enlightenment in the Vajrayana tradition

Exploring enlightenment in the Vajrayana tradition

Studying the path to enlightenment through the ten ox-herding pictures of Zen

Studying the path to enlightenment through the ten ox-herding pictures of Zen

A pioneering book detailing the sudden awakening experiences of ten meditators drew Stephan to the practice of Buddhism in the late 1960s. Presented in the form of letters and journal entries, these dramatic accounts chronicled years of intensive meditation practice and the powerful, life-changing breakthroughs that ultimately (though not immediately) followed. Men and women wept and laughed with joy as they finally penetrated years of conditioning and ultimately realized who they really were.

As a young college student, Stephan had experienced his share of suffering and had searched Western philosophy looking for solutions, so he was enthralled by what he read. He immediately became hooked on meditation. If those ordinary folks could wake up, he thought he could, too.

In those days, few people had even heard the word enlightenment used in the Buddhist context, and the available books on Buddhism for a general audience may have filled half a bookshelf, at best. Things have really changed in the past 30 years! Today books dealing with aspects of Buddhism regularly make The New York Times bestseller lists, and everyone seems to be seeking enlightenment in some form. You can read popular manuals for “awakening the Buddha within” or achieving “enlightenment on the run,” and you can take “enlightenment intensives” at your local yoga studio. One perfume company even produces a scent they call Satori, the Japanese word for “enlightenment.”

But what does enlightenment (or awakening) really mean in Buddhism? Though the current quick-fix culture has trivialized it, enlightenment is often considered the culmination of the spiritual path, which may take a lifetime of practice and inquiry to achieve. In this chapter, we describe (as much as words possibly can) what enlightenment is — and is not — and explain how people’s understanding of it has changed as Buddhism evolved and adapted to different cultures.

Considering the Many Faces of Spiritual Realization

If you read the stories of the world’s great mystics and sages, you find that spiritual experiences come in a dazzling array of shapes and sizes. For example:

Some Native American shamans enter altered states in which they journey to other dimensions to find allies and other healing resources for their tribe members.

Some Native American shamans enter altered states in which they journey to other dimensions to find allies and other healing resources for their tribe members.

Some Hindus experience visions of deities and feelings of ecstasy through the rising of an energy known as kundalini, enter blissful states that last for hours, or merge in union with divinities like Shiva.

Some Hindus experience visions of deities and feelings of ecstasy through the rising of an energy known as kundalini, enter blissful states that last for hours, or merge in union with divinities like Shiva.

Christian saints and mystics have encountered transformative visions of Jesus, received visitations from angels, and manifested the stigmata (marks resembling the crucifixion wounds of Christ) in their hands and feet.

Christian saints and mystics have encountered transformative visions of Jesus, received visitations from angels, and manifested the stigmata (marks resembling the crucifixion wounds of Christ) in their hands and feet.

The Hebrew Bible is filled with tales of prophets and patriarchs who meet Jehovah in some form — as the fire in the burning bush, the voice in the whirlwind, and so on.

The Hebrew Bible is filled with tales of prophets and patriarchs who meet Jehovah in some form — as the fire in the burning bush, the voice in the whirlwind, and so on.

Though such dramatic experiences can have a transformative spiritual impact on an individual, they may or may not be enlightening, as Buddhists understand this term. In fact, most traditions of Buddhism downplay the importance of visions, voices, powers, energies, and altered states, claiming that they distract practitioners from the true purpose of the spiritual endeavor — a direct, liberating insight into the essential nature of reality.

The basic Buddhist teaching of impermanence (Pali: anicca) suggests that even the most powerful spiritual experiences come and go like clouds in the sky. The point of practice is to realize a truth so deep and fundamental that it doesn’t change, because it’s not an experience at all; it’s the nature of reality itself. This undeniable, unalterable realization is known as enlightenment.

The Buddha also taught that all beings have the same potential for enlightenment that he had. Among the characteristics distinguishing ordinary beings from a Buddha are the distorted views, attachments, and aversive emotions that block the truth from their eyes.

All traditions of Buddhism would undoubtedly agree on the fundamental teachings about enlightenment that we outline in the two preceding paragraphs — after all, these teachings come from the earliest and most universally accepted of the Buddha’s discourses. The traditions differ, however, over the contents of enlightenment and the precise means of achieving it. What is the actual goal of the spiritual life? What do you awaken to — and how do you get there? Believe it or not, the answers to these questions changed over the centuries as Buddhism evolved.

Most traditions believe that their version of enlightenment is exactly the same as the Buddha’s. Some claim that theirs is the only true version — the deeper, secret realization that the Buddha never dared reveal during his lifetime. Other commentators insist that the realization of later Buddhist masters carried both practice and enlightenment to dimensions that the Buddha himself had never anticipated. Whatever the truth may be, the traditions clearly differ in significant ways.

As you read the following sections, keep this old Zen adage in mind: “A painting of a rice cake cannot satisfy hunger.” You can look at pictures of pastries all day long, but you won’t feel fulfilled until you taste the real thing for yourself. In the same way, you can read dozens of books about enlightenment, but you won’t really understand what they’re talking about until you catch a glimpse of the actual experience. Does that sound like an invitation to practice Buddhism? Well, you’re right — it is!

Reviewing the Theravada Tradition’s Take on Nirvana

The Theravada tradition bases its teachings and practices on the Pali canon, which includes the Buddha’s discourses (Pali: suttas) that were preserved through memorization (by monks actually in attendance), passed along orally for many generations, and ultimately written down more than four centuries after the Buddha’s death. (For someone who has a hard enough time remembering a few phone numbers, such memorization skills boggle the mind.) Because these teachings are ascribed to the historical Buddha, some proponents of the Theravada tradition claim that they represent original Buddhism — that is, Buddhism as the Enlightened One actually taught it and intended it to be practiced and realized.

The Theravada tradition elaborates a detailed, progressive path of practice and realization that leads the student through four stages of enlightenment, culminating in nirvana (Pali: nibbana) — the complete liberation from suffering. The path itself consists of three aspects, or trainings: moral discipline (ethical conduct), concentration (meditation practice), and wisdom (study of the teachings and direct spiritual insight). (For more on the three trainings, see Chapters 8 and 13. For more on the Theravada tradition, check out Chapter 5.)

Defining nirvana

Because the Buddha considered craving and ignorance to be two of the root causes of all suffering, he often defines nirvana as the extinction of craving and eradication of ignorance.

However, if nirvana has a particular feeling or tone, it’s generally characterized as unshakable tranquility, contentment, and bliss (see Figure 10-1). Sound appealing?

Figure 10-1: Shakyamuni Buddha, the classic embodiment of serenity and peace.

Revealing the four stages on the path to nirvana

These types of practitioners have attained the distinct stages on the path to nirvana:

Stream-enterer: The practitioner has broken three of ten fetters: the erroneous view that a personality exists, doubt about the path to liberation, and attachment to rules and rituals. He has thereby entered the stream that leads to nirvana. This person purportedly will attain nirvana within seven lives.

Stream-enterer: The practitioner has broken three of ten fetters: the erroneous view that a personality exists, doubt about the path to liberation, and attachment to rules and rituals. He has thereby entered the stream that leads to nirvana. This person purportedly will attain nirvana within seven lives.

Once-returner: This person has significantly weakened two additional fetters: craving and aversion. He will be reborn as a human being no more than one time before reaching the fourth stage, that of an arhat (see the last bullet point of this list).

Once-returner: This person has significantly weakened two additional fetters: craving and aversion. He will be reborn as a human being no more than one time before reaching the fourth stage, that of an arhat (see the last bullet point of this list).

Nonreturner: The practitioner has completely eliminated all of the five fetters previously mentioned and will not be reborn as a human being.

Nonreturner: The practitioner has completely eliminated all of the five fetters previously mentioned and will not be reborn as a human being.

Arhat: This person has completely broken ten fetters, including these additional five: the craving for existence in the sphere of form, the craving for existence in the formless sphere, pride, restlessness, and ignorance. He has attained full enlightenment and reached the end of suffering. The ancient collection of verses on Buddhist themes, the Dhammapada, describes him in verses 95 and 96 as follows:

Arhat: This person has completely broken ten fetters, including these additional five: the craving for existence in the sphere of form, the craving for existence in the formless sphere, pride, restlessness, and ignorance. He has attained full enlightenment and reached the end of suffering. The ancient collection of verses on Buddhist themes, the Dhammapada, describes him in verses 95 and 96 as follows:

“His patience is like that of the earth. He is firm like a pillar and serene like a lake. No rounds of rebirths are in store for him. His mind is calm, speech and action are calm of one who has attained freedom by true knowledge. For such a person there is peace.”

At this point, the circumstances of life no longer have the slightest hold over a person; positive or negative experiences no longer stir even the slightest craving or dissatisfaction. As the Buddha said, all that needed to be done has been done. There’s nothing further to realize. The path is complete.

Getting a Handle on Two Traditions of Wisdom

As Buddhism developed over the centuries, various schools emerged that differed in how they framed the path to enlightenment and how they understood the ultimate goal of this path. (For more on these developments, see Chapters 4 and 5.) Some Mahayana (“Great Vehicle” or “Great Path”) schools shifted the emphasis from the experience of no-self to the experience of emptiness. (Chapter 14 explains the concept of emptiness.)

The two main commentarial branches of the Mahayana tradition understood emptiness (or ultimate reality) in two quite different ways. The Madhyamika (Sanskrit for “middle doctrine”) school refused to assert anything about ultimate reality. Instead, these folks chose to refute and discredit any positive assertions that other schools made. The end result left practitioners without any belief or point of view to hold on to, which effectively pulled the rug out from under their conceptual minds and forced them to, in the words of the great Mahayana text, the Diamond Sutra, “cultivate the mind that dwells nowhere” — the spacious, expansive, unattached mind of enlightenment.

By contrast, the Yogachara (Sanskrit for “practice of yoga”) school said that the world as we perceive it is only a manifestation of the mind, or consciousness. (This view gave rise to the other name for this school, Vijnanavada (Sanskrit for “teaching [in which] consciousness or mind [plays a special role]”).

Realizing the Mind’s Essential Purity in the Vajrayana Tradition

“Nondual” simply means that subject and object, matter and spirit are “not two” — that is, they’re different on an everyday level, but they’re inseparable at the level of essence. For example, you and the book you see in front of you are different in obvious ways, but you’re essentially expressions of an inseparable whole. Now, don’t expect us to put this oneness into words the mind can understand, though mystics and poets have been trying their best for thousands of years. If you want to know more, you just may have to check it out for yourself.

Not only is the nature of mind innately pure, radiant, and aware, but it also spontaneously manifests itself in each moment as compassionate activity for the benefit of all beings. Though conceptual thought can’t grasp the nature of mind, this mind-nature (like no-self) can be realized through meditation in a series of ever-deepening experiences culminating in complete realization, or Buddhahood.

In Vajrayana, the path to complete enlightenment begins with the extensive cultivation of positive qualities, like loving-kindness and compassion, and then progresses to the development of various levels of insight into the nature of mind. In some traditions, practitioners are taught to visualize themselves as the embodiment of enlightenment itself and then to meditate upon their inherent awakeness, or Buddha nature. (For more on the Vajrayana path, see Chapter 5.)

Taking the direct approach to realization

Some consider the Dzogchen-Mahamudra teachings the highest teaching of the Tibetan traditions. Dzogchen means “great perfection” in Tibetan, and Mahamudra is Sanskrit for “great seal.” Both terms refer to the insight that everything is perfect just the way it is.

These two approaches are generally considered to be slightly different expressions of the same nondual realization. (For a complete explanation of nondualism, see the second paragraph earlier in this section.) Traditionally, only practitioners who completed years of preliminary practice are qualified to learn about Dzogchen-Mahamudra, but today in the West, anyone sincere and motivated enough to attend a retreat can explore this approach to enlightenment.

Understanding the complete enlightenment of a Buddha

The Theravada tradition considers the final goal of spiritual practice, exemplified by the arhat (see the section “Reviewing the Theravada Tradition’s Take on Nirvana,” earlier in the chapter, for a reminder of what arhat means), to be eminently attainable in this lifetime by any sincere practitioner. In the time of the historical Buddha, numerous disciples achieved complete realization and were acknowledged as arhats, which meant that their realization of no-self was essentially the same as the Buddha’s.

In the Vajrayana tradition, by contrast, the realization of Buddhahood appears to be a much more protracted path. The completely enlightened ones experience the end of all craving and other negative emotions, but these folks also exhibit numerous beneficial qualities, including boundless love and compassion, infinite, all-seeing wisdom, ceaseless enlightened activity for the welfare of all beings, and the capacity to speed others on their path to enlightenment.

Needless to say, many of the faithful (especially at the beginning levels of practice) may see such an advanced stage of realization as a distant and unattainable dream. Compounding this feeling may be the many inspiring stories of exceptional sages who meditate for years in mountain caves and achieve not only a diamondlike clarity of mind and inexhaustible compassion, but also numerous superhuman powers.

Yet dedicated Vajrayana practitioners do gradually see their efforts lead to greater compassion, clarity, tranquility, and fearlessness, along with a deeper and more abiding recognition of the nature of mind. Indeed, Vajrayana promises that everyone has the potential to achieve Buddhahood in this lifetime by using the powerful methods it provides. (For more on Vajrayana practices, see Chapter 5.)

Standing Nirvana on Its Head with Zen

Zen is filled with stories of great masters who compare their enlightenment with Shakyamuni’s enlightenment and speak of him as if he were an old friend and colleague. At the same time, enlightenment (though elusive) is regarded as the most ordinary realization of what has always been so. For this reason, the monks in many Zen stories break into laughter when they finally “get it.” Awakened Zen practitioners are known for their down-to-earth involvement in every activity and for not displaying any trace of some special state called “realization.”

Tuning in to the direct transmission from master to disciple

A reflection of a certain attitude toward enlightenment may be found in this Chan/Zen slogan:

A special transmission outside the scriptures,No dependence on words and letters.Directly pointing to the mind,See true nature, become a Buddha.

The verse makes several points, which the following list expands on:

Special transmission outside the scriptures: Zen traces its lineage back to Mahakashyapa, one of the Buddha’s foremost disciples who apparently received the direct transmission of his teacher’s “mind essence” by accepting a flower with a wordless smile (see Chapter 5 for more info). Since then, masters have directly “transmitted” their enlightened mind to their disciples, not through written texts, but through teachings passed on from mind to mind (or, as Stephan’s first Zen teacher liked to say, “from one warm hand to another”). But the truth is that enlightenment itself isn’t transmitted; it has to burst into flame anew in each generation. The teacher merely acknowledges and certifies the awakening.

Special transmission outside the scriptures: Zen traces its lineage back to Mahakashyapa, one of the Buddha’s foremost disciples who apparently received the direct transmission of his teacher’s “mind essence” by accepting a flower with a wordless smile (see Chapter 5 for more info). Since then, masters have directly “transmitted” their enlightened mind to their disciples, not through written texts, but through teachings passed on from mind to mind (or, as Stephan’s first Zen teacher liked to say, “from one warm hand to another”). But the truth is that enlightenment itself isn’t transmitted; it has to burst into flame anew in each generation. The teacher merely acknowledges and certifies the awakening.

Directly pointing to the mind: The master doesn’t explain abstract truth intellectually. Instead, he points his disciples’ attention directly back to their innate true nature, which is ever present but generally unrecognized. With the master’s guidance, the disciple wakes up and realizes that he isn’t this limited separate self, but is rather pure, vast, mysterious, ungraspable consciousness itself — also known as the Buddha nature or Big Mind.

Directly pointing to the mind: The master doesn’t explain abstract truth intellectually. Instead, he points his disciples’ attention directly back to their innate true nature, which is ever present but generally unrecognized. With the master’s guidance, the disciple wakes up and realizes that he isn’t this limited separate self, but is rather pure, vast, mysterious, ungraspable consciousness itself — also known as the Buddha nature or Big Mind.

See true nature, become a Buddha: Having realized true nature, the disciple now sees with the eyes of the Buddha and walks in the Buddha’s shoes. No distance in space and time separates Shakyamuni’s mind and the disciple’s mind. Illustrating this point, some version of the following passage appears repeatedly in the old teaching tales: “There is no Buddha but mind, and no mind but the Buddha.”

See true nature, become a Buddha: Having realized true nature, the disciple now sees with the eyes of the Buddha and walks in the Buddha’s shoes. No distance in space and time separates Shakyamuni’s mind and the disciple’s mind. Illustrating this point, some version of the following passage appears repeatedly in the old teaching tales: “There is no Buddha but mind, and no mind but the Buddha.”

The ten ox-herding pictures

Ever since the ten ox-herding pictures were first created in 12th-century China, Zen masters in China, Korea, and Japan have used them to instruct and inspire their students. The images illustrate the ten stages of training the mind by comparing them to the taming of an ox. They begin with an individual’s search for the ox and culminate with his or her complete liberation. The images (less frequently known as the cow-herding pictures) depict, in most cases, a water buffalo. After they became popular, numerous artists drew them over the centuries, with only minor differences. There’s also a series of six ox-herding pictures in which the color of the ox undergoes gradual lightening from dark to white until the ox disappears. The comparison of an ox that needs to be tamed to a practitioner’s unruly mind was already being made in early Indian Buddhist texts. These texts commonly use similes that appeal to a society whose main occupation was agriculture. One example is comparing the concept of karma to a seed that is sown in the ground and eventually bears fruit.

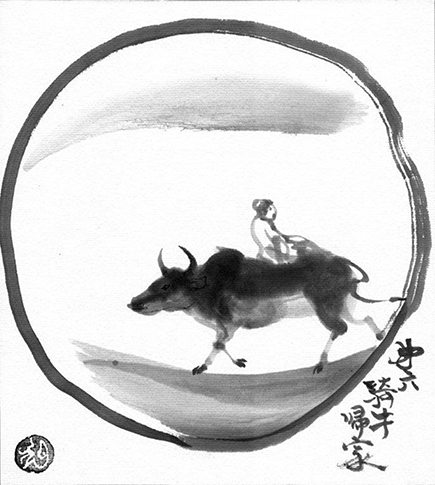

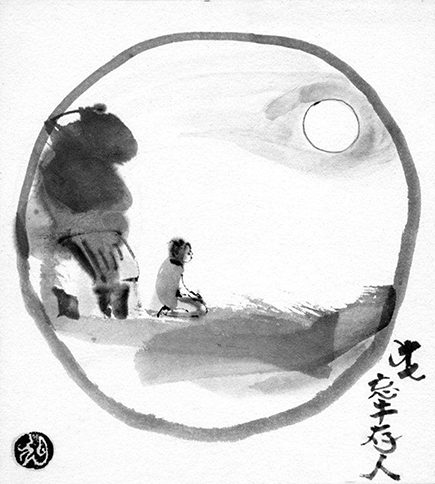

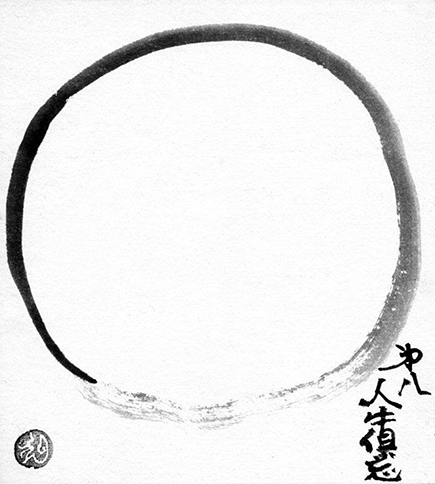

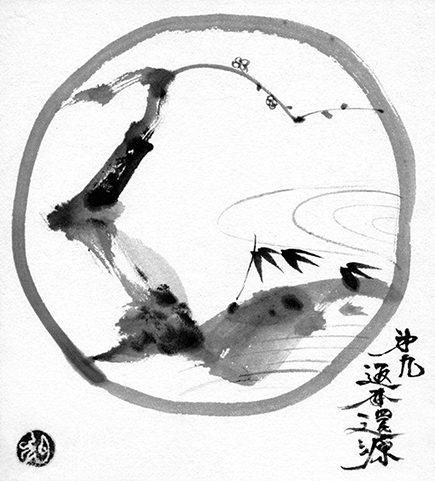

Here we reproduce the set of ten ox-herding pictures painted by the Japanese artist Tatsuhiko Yokoo (born in 1928; see Figures 10-2 to 10-11).

The following describes each picture and explains its meaning:

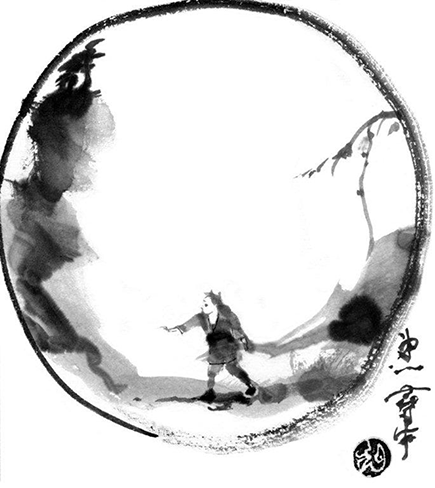

Seeking the ox (see Figure 10-2): The first picture shows the herder, rope in hand, wandering in search of the lost ox.

Seeking the ox (see Figure 10-2): The first picture shows the herder, rope in hand, wandering in search of the lost ox.

You have the desire to practice the Buddha’s teaching and are taking the first steps in Zen practice.

Figure 10-2: Seeking the ox.

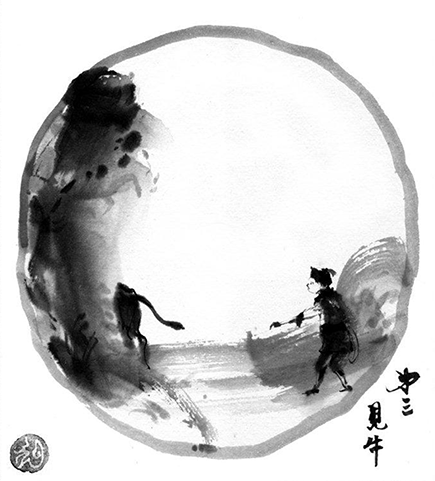

Finding the tracks (see Figure 10-3): In the second picture, the herder finds the tracks of the ox and follows them.

Finding the tracks (see Figure 10-3): In the second picture, the herder finds the tracks of the ox and follows them.

Having been introduced to the teachings of Zen, you study and practice them diligently and acquire a conceptual understanding of them.

Figure 10-3: Finding the tracks.

Glimpsing the ox (see Figure 10-4): In the third picture, the herder glimpses the rear of the ox.

Glimpsing the ox (see Figure 10-4): In the third picture, the herder glimpses the rear of the ox.

You’ve clearly seen your true nature for the first time. But this realization quickly slips into the background, and you’re still a long way from making it your constant companion.

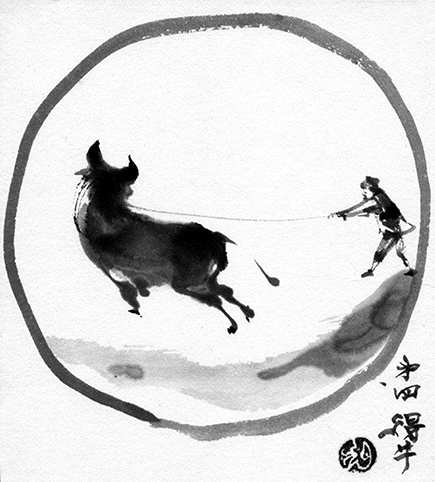

Catching the ox (see Figure 10-5): In the fourth picture, the herder has caught the resistant ox and holds it by a rope.

Catching the ox (see Figure 10-5): In the fourth picture, the herder has caught the resistant ox and holds it by a rope.

You’re aware of your true nature in every moment and situation; you’re never apart from it — even for an instant. But your mind continues to be turbulent and unruly, and you need to concentrate to keep from getting distracted.

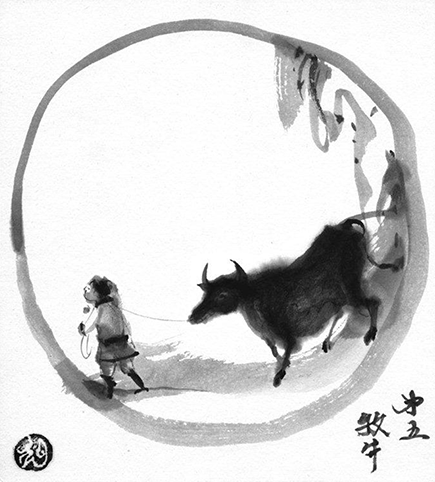

Taming the ox (see Figure 10-6): In the fifth picture, the herder leads the now-docile ox by a rope.

Taming the ox (see Figure 10-6): In the fifth picture, the herder leads the now-docile ox by a rope.

Finally, as every trace of doubt disappears, the mind settles down. You’re so firmly established in your experience of your true nature that even thoughts no longer distract you, for you realize that, like everything else in the universe, they’re just an expression of who you fundamentally are.

Figure 10-4: Glimpsing the ox.

Figure 10-5: Catching the ox.

Figure 10-6: Taming the ox.

Riding the ox home (see Figure 10-7): In the sixth picture, the herder has mounted the ox and rides home. The ox moves of its own accord, without being led by a rope.

Riding the ox home (see Figure 10-7): In the sixth picture, the herder has mounted the ox and rides home. The ox moves of its own accord, without being led by a rope.

Now you and your true nature are in total harmony. You no longer have to struggle to resist temptation or distraction; you’re completely at peace, inextricably connected to your essential source.

Forgetting the ox (see Figure 10-8): In the seventh picture, the herder is sitting outside his hut alone at sunrise.

Forgetting the ox (see Figure 10-8): In the seventh picture, the herder is sitting outside his hut alone at sunrise.

At last, the ox of your true nature has disappeared because you have completely and inseparably incorporated it. The ox was a convenient metaphor to lead you home. Ultimately, however, you and the ox are one! With nothing left to seek, you’re thoroughly at ease, meeting life as it unfolds.

Forgetting both self and ox (see Figure 10-9): The last three pictures describe the state of a Buddha after his enlightenment. In the eighth picture, we see an empty circle.

Forgetting both self and ox (see Figure 10-9): The last three pictures describe the state of a Buddha after his enlightenment. In the eighth picture, we see an empty circle.

The last traces of a separate self have dropped away, and, with them, the last vestiges of realization have vanished. Even the thought “I am enlightened” or “I am the embodiment of Buddha nature” no longer arises. You’re at the same time completely ordinary and completely free of any attachment or identification.

Figure 10-7: Riding the ox home.

Figure 10-8: Forgetting the ox.

Figure 10-9: Forgetting both self and ox.

Returning to the source (see Figure 10-10): The ninth picture shows nature in full bloom, without an observer.

Returning to the source (see Figure 10-10): The ninth picture shows nature in full bloom, without an observer.

After you’ve merged with your source, you see everything in all its diversity (painful and pleasurable, beautiful and ugly) as the perfect expression of this source. You don’t need to resist or change anything; you’re completely one with the suchness of life.

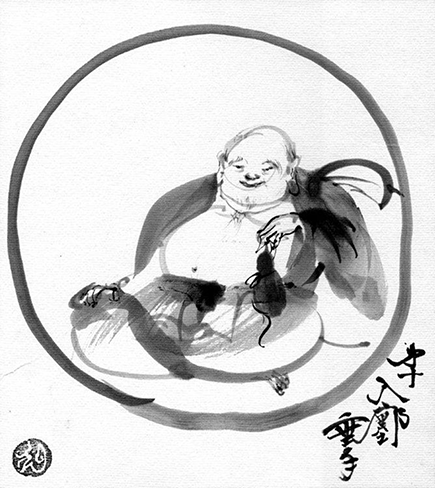

Entering the world with helping hands (see Figure 10-11): In the tenth picture, an older big-bellied and bare-chested figure sits happily at rest.

Entering the world with helping hands (see Figure 10-11): In the tenth picture, an older big-bellied and bare-chested figure sits happily at rest.

With no trace of a separate self to be enlightened or deluded, the distinction between the two dissolves in spontaneous, compassionate activity. Now you move freely through the world like water through water, without the slightest resistance, joyfully responding to situations as they arise, helping where appropriate and naturally kindling awakening in others.

Figure 10-10: Returning to the source.

Figure 10-11: Entering the world with helping hands

Finding the Common Threads in Buddhist Enlightenment

The experience of enlightenment, though described slightly differently and approached by somewhat different means, bears notable similarities from tradition to tradition.

Enlightenment signals the end of suffering and the eradication of craving and ignorance.

Enlightenment signals the end of suffering and the eradication of craving and ignorance.

Enlightenment also inevitably brings the birth of unshakable, indescribable peace, joy, loving-kindness, and compassion for others.

Enlightenment also inevitably brings the birth of unshakable, indescribable peace, joy, loving-kindness, and compassion for others.

Enlightenment involves being in the world but not of it.

Enlightenment involves being in the world but not of it.