Chapter 4

The Renaissance to the Wars of Religion: c. 1450–c. 1648

THE RENAISSANCE: AN OVERVIEW

Fifteenth- and sixteenth-century intellectuals and artists believed that they were part of a new golden age. Georgio Vasari, a sixteenth-century painter, architect, and writer, used the Italian word rinascità, meaning “rebirth,” to describe the era in which he lived. Vasari and other artists and intellectuals believed that their achievements owed nothing to the backwardness of the Middle Ages and instead were directly linked to the glories of the Greek and Roman world. History tells us that they were kidding themselves. The Renaissance artisans owed far more to the cultural and intellectual achievements of the medieval world than they cared to acknowledge. Nevertheless, the Renaissance was a time in which significant contributions were made to Western civilization, with particular gains in literature, art, philosophy, and political and historical thought. Our modern notion of individualism was also born during the Renaissance, as people sought to receive personal credit for their achievements, opposed to the medieval ideal of all glory going to God.

These intellectual and artistic developments first took place in the vibrant world of the Italian city-states. Eventually, the invention of the printing press in the mid-fifteenth century allowed these cultural trends to spread to other parts of Europe, which resulted in the creation of the Northern Renaissance movement. The Italian Renaissance writers were primarily interested in secular concerns, but in the north of Europe, the Renaissance dealt with religious concerns and ultimately helped lay the foundation for the movement known as the Protestant Reformation.

THE ITALIAN CITY-STATES

The Italian States During the Renaissance

The city-states of Renaissance Italy were at the center of Europe’s economic, political, and cultural life throughout the fourteenth and fifteenth centuries. During the Middle Ages, the towns of northern Italy were nominally under the control of the Holy Roman Empire; residents, however, were basically free to decide their own fate, which resulted in a tremendously vibrant—and at times violent—political existence. The old nobility, whose wealth was based on land ownership, often conflicted with a new class of merchant families who had become wealthy in the economic boom times of the twelfth and thirteenth centuries. Both groups had to contend with an urban underclass, known as the popolo, or “the people,” who wanted their own share of the wealth and political power.

In Florence in 1378, the popolo expressed their dissatisfaction with the political and economic order by staging a violent struggle against the government that became known as the Ciompi Revolt. The revolt shook Florence to its very core and resulted in a brief period in which the poor established a tenuous control over the government.

This struggle reverberated in the other city-states throughout Italy. In Milan, the resulting social tensions led to the rise of a tyrant, or signor, and the city eventually came to be dominated by the family of a mercenary (condottiero) named Sforza. Florence and Venice remained republics after the revolt, but a few wealthy families dominated them. The most noteworthy of these families, the Medici, used the wealth gained from banking to establish themselves first as the behind-the-scenes rulers of the Florentine republic and later as hereditary dukes of the city.

The internal tensions within the city-states were matched by external rivalries as the assorted city-states were engaged in long-term warfare among themselves. By the mid-fifteenth century, these external wars had effectively narrowed the numerous city-states of the medieval age to just a few dominant states—Florence, Milan, and Venice in the north, the papal states in central Italy, and the Kingdom of Naples in southern Italy.

In addition to every city-state’s internal and external tensions that may have helped stir the creative energy that was so important to the Renaissance, economic factors were also a significant energy-creating agent. The Italian city-states were generally more economically vibrant than the rest of western Europe, with merchants carrying Italian wool and silk to every part of the continent, and with Italian bankers providing loans for money-hungry European monarchs. Wealthy Italian merchants became important patrons of the arts and insisted on the development of secular art forms, such as portraiture, that would represent them and their accumulated wealth to the greatest effect.

Geography also played a role in the vibrant cultural life of the Italian Renaissance. Italy’s central location in the Mediterranean was ideal for creating links between the Greek culture of the east and the Latin culture of the west. Additionally, southern Italy had been home to many Greek colonies and later served as the center for the Roman Empire. In essence, classical civilization had never totally disappeared from the Italian mainland, even following the collapse of the western half of the Roman Empire in the fifth century.

HUMANISM

Humanism is a highly debated term among historians. Most would characterize it not as representing a particular philosophical viewpoint but rather as a program of study, including rhetoric and literature, based on what students in the classical world (c. 500 B.C.E. to 500 C.E.) would have studied. Francesco Petrarch (1304–1374) is often considered the father of humanism. Petrarch became dissatisfied with his career as a lawyer and set about to study literary classics. It was Petrarch who coined the phrase “Dark Ages” (c. 400–900) to denote what he thought was the cultural decline that took place following the collapse of the Roman world in the fifth century.

While literate in medieval Latin from his study of law, Petrarch learned classical Latin as preparation to study these important literary works. In a task that was to become exceedingly important during the Renaissance, Petrarch sought classical texts that had been largely unknown during the Middle Ages. It was common in the Middle Ages to become familiar with classical works not by directly reading the original manuscripts but rather by reading secondary commentaries about the works. Petrarch set out to read the originals and quickly found himself engaged with such works as the letters of Cicero, an important politician and philosopher whose writings provide an account of the collapse of the Roman Republic. Cicero was a brilliant Latin stylist. To write in the Ciceronian style became the stated goal of Petrarch and those humanists who followed in his path.

The Italian Renaissance and the Greek Revival

The revival of Greek is one of the most important aspects of the Italian Renaissance. It allowed Westerners to become acquainted with that part of the classical heritage that had been lost during the Middle Ages—most significantly the writings of the ancient Greek philosopher Plato (427–348 B.C.E.). In particular, these writers were fascinated by Plato’s belief that ideals such as beauty or truth exist beyond the ability of our senses to recognize them, and that we can train our minds to make use of our ability to reason and thus get beyond the limits imposed by our senses. This positive Platonic view of human potential is found in one of the most famous passages from the Renaissance, Pico della Mirandola’s Oration on the Dignity of Man. In addition, the Florentine Platonic Academy, sponsored by Cosimo d’Medici, merged platonic philosophy with Christianity to create Neoplatonism. A closely-related school of thought was hermeticism, a pantheistic philosophy stating that God is in everything and that humans were created divine but chose to live in a material world. It was associated with astrology, alchemy, and the kabbalah—all important parts of Italian Renaissance intellectual life.

Although his contemporaries accused him of turning to the pagan culture of ancient Greece and Rome, Petrarch—despite his fascination with classical culture—did not reject Christianity. Instead, he argued for the universality of the ideas of the classical age. Petrarch contended that classical works, although clearly written by pagans, still contained lessons that were applicable to his own Christian age.

Petrarch’s work served as inspiration to a group of wealthy young Florentines known as the “civic humanists.” They viewed Cicero’s involvement in political causes as justification to use their own classical education for the public good. They did this by serving Florence as diplomats or working in the chancellery office, where official documents were written. They also went beyond Petrarch’s achievements by studying a language that had almost been completely lost in western Europe—classical Greek.

Renaissance humanist scholarship branched out in a number of different directions. Some writers strove to describe the ideal man of the age. In Castiglione’s The Courtier (1528), such a person would be a man who knew several languages, was familiar with classical literature, and was also skilled in the arts—what we might label today as a “Renaissance Man” (or l’uomo universale). Other contributions were made in the new field of critical textual analysis. Lorenzo Valla was one of the critical figures in this area. Working in the Vatican libraries, he realized that languages can tell a history all their own. In 1440, he proved that the Donation of Constantine, a document in which Constantine, the first Christian Emperor, turned control of the western half of his empire over to the papacy, could not have been written by Constantine. Valla noticed that the word fief was used by Constantine in describing the transfer of authority to the pope, a word that Valla knew was not in use until the eighth century, around four hundred years after Constantine’s death. In another work that influenced the humanists in northern Europe, Valla took his critical techniques to the Vulgate Bible, the standard Latin Bible of the Middle Ages, and showed that its author, Jerome, had mistranslated a number of critical passages from the Greek sources.

Women were also affected by the new humanist teachings. Throughout the Middle Ages, there were women, very often attached to nunneries, who learned to read and write. During the Renaissance, an increasing number of wealthy, secular women picked up these skills. The humanist scholar Leonardo Bruni even went so far as to create an educational program for women, but tellingly left out of his curriculum the study of rhetoric or public speech, critical parts of the male education, since women had no outlet to make use of these skills. Christine de Pisan, an Italian who was the daughter of the physician to the French King Charles V, received a fine humanist education through the encouragement of first her father and later her husband. She wrote The City of Ladies (1405) to counter the popular notion that women were inferior to men and incapable of making moral choices. Pisan wrote that women have to carve out their own space or move to a “City of Ladies” in order for their abilities to be allowed to flourish. (Virginia Woolf would later espouse this idea in her early twentieth-century work, A Room of One’s Own.)

RENAISSANCE ART

It is arguably in the area of fine arts that the Renaissance made its most notable contribution to Western culture. A number of different factors drove Renaissance art. In a reflection of the shift toward individualism, Renaissance artists were now considered to be important individuals in their own right, whereas in the Middle Ages they toiled as anonymous craftsmen. These artists sought prestige and money by competing for the patronage of secular individuals such as merchants and bankers, who wanted to sponsor art that would glorify their achievements rather than tout the spiritual message that was at the heart of medieval art.

Classical Motifs in Renaissance Art

In architecture, one can see the increasing influence of classical motifs, such as the use of simple symmetrical decorations and classical columns. Perhaps the most noteworthy architectural achievement of the Early Renaissance period was the building of a dome over the Cathedral of Florence by Filippo Brunelleschi, the first dome to be completed in western Europe since the collapse of the Roman Empire.

These patrons demanded a more naturalistic style, which was aided by the development of new artistic techniques, including the rejection of the old practice of hierarchical sealing, in which figures in a composition were sized in proportion to their spiritual significance. In the Middle Ages, painting consisted of fresco on wet plaster or tempera on wood. In the fifteenth century, oil painting, which developed in the north of Europe, became the dominant method in Italy. Artists also began to make use of chiaroscuro, the use of contrasts between light and dark, to create three-dimensional images. Perhaps the most important development was in the 1420s with the discovery of single-point perspective, a style in which all elements within a painting converge at a single point in the distance, allowing artists to create more realistic settings for their work.

The end of the fifteenth century marked the beginning of the movement known as the High Renaissance. During the High Renaissance, the center of the Renaissance moved from Florence to Rome. Florence had experienced a religious backlash against the new style of art, while in Rome, a series of popes (most notably Michelangelo’s great patron Julius II) were very interested in the arts and sought to beautify their city and their palaces. The High Renaissance lasted until around the 1520s, when art began to move in a different direction. We sometimes label this art as Late Renaissance, or Mannerism, an art that showed distorted figures and confusing themes and may have reflected the growing sense of crisis in the Italian world due to both religious and political problems.

There are three major High Renaissance artists with whom you should be familiar: Leonardo da Vinci, Raphael, and Michelangelo.

Leonardo da Vinci

While it is a bit of a cliché to label Leonardo da Vinci (1452–1519) as a Renaissance man, the label is accurate. Leonardo was a military engineer, an architect, a sculptor, a scientist, and an inventor whose sketchbooks reveal a remarkable mind that came up with workable designs for submarines and helicopters. Recent reconstructions of his sketches show that he even designed a handbag. Oh yes, he was also a painter, as the hordes of tourists snaking their way through the Louvre to see the Mona Lisa will attest to.

Raphael

In an age of artistic prima donnas, Raphael (1483–1520), a kindly individual, stands out for not being despised by his contemporaries. He came from the beautiful Renaissance city of Urbino and died at the early age of 37, but in his brief life, he was given some very important commissions in the Vatican palaces. Besides his wonderfully gentle images of Jesus and Mary, Raphael links his own times and the classical past in The School of Athens, which shows Plato and Aristotle standing together (in a crowd that also features the images of Leonardo and Michelangelo) in a fanciful classical structure and uses the deep, single-point perspective characteristic of High Renaissance style.

Michelangelo

Like Leonardo, Michelangelo (1475–1564) was skilled in numerous areas. His sculptural masterpiece David was commissioned by Michelangelo’s native city, Florence, as a propaganda work to inspire the citizens in their long struggle against the overwhelming might of Milan. Four different popes commissioned works from him, most notably the warlike Julius II, who gave Michelangelo the task of creating his tomb. Julius II also employed Michelangelo to work on the Sistine Chapel in the Vatican, a work that Julius II began to have doubts about as he rushed to have the revealing anatomy of some of the figures covered up with fig leaves, much to the anger of its creator. Michelangelo, who enjoyed a very long life, lived to see the style of art in Italy change from the harmony and grace of the High Renaissance to the more tormented style of the Late Renaissance, as viewed in his final work in the Sistine Chapel, the brilliant yet disturbing Final Judgment.

THE NORTHERN RENAISSANCE

By the late fifteenth century, Italian Renaissance humanism began to affect the rest of Europe. Although the writers of the Italian Renaissance were Christian, they thought less about religious questions than their northern counterparts. In the north, questions concerning religion were paramount. Christianity had arrived in the north later than in the south, and northerners at this time were still seeking ways to deepen their Christian beliefs and understanding and display what good humanists they were. They believed they could achieve this higher level by studying early Christian authors. In this sense, the Northern Renaissance was a more religious movement than the Renaissances in Italy. Eventually, northern writers such as Erasmus and More, often referred to as Christian Humanists, criticized their mother church, only to find to their horror that more extreme voices of dissent—for example, that of Martin Luther—had not used their methodology to find ways to better the Catholic Church, but to show why the Church had strayed from the will of God.

Erasmus and Sir Thomas More

The greatest of the northern humanists was Desiderius Erasmus (1466?–1536). You can thank Erasmus the next time you use such tired clichés as “Where there’s smoke, there’s fire,” since he collected this and many other ancient and contemporary proverbs in his Adages. Erasmus’s In Praise of Folly used satire as a means of criticizing what he thought were the problems of the Church. His Handbook of the Christian Knight emphasized the idea of inner faith as opposed to the outer forms of worship, such as partaking of the sacraments. Erasmus’s Latin translation of the New Testament also played a major role in the sixteenth-century movement to better understand the life of the early Christians through its close textual analysis of the Acts of the Apostles. Erasmus was at first impressed with Luther’s attacks on the Church and even initiated a correspondence with him. Eventually, however, the two men found that they had significant disagreements. Unlike Luther, Erasmus wanted to reform the Church, not abandon it, and he could never accept Luther’s belief that man does not have free will.

Another important northern humanist was the Englishman Sir Thomas More (1478–1535). A friend of Erasmus, he wrote the classic work Utopia (1516). More was critical of many aspects of contemporary society and sought to depict a civilization in which political and economic injustices were limited by having all property held in common. More, like Erasmus, was highly critical of certain practices of his church, but in the end he gave his life for his beliefs. In 1534, Henry VIII had More, who was serving the King as his chancellor, executed for refusing to take an oath recognizing Henry as Head of the Church of England.

Northern Renaissance Culture

The Northern Renaissance also represented more than simply the Christian humanism of individuals such as More and Erasmus. Talented painters from the north, while clearly influenced by the artists of the Italian Renaissance with whom they often came into contact on visits to the Italian peninsula, also created their own unique style. This is seen, for example, in the work of Albrecht Durer, a brilliant draftsman, whose woodcuts powerfully lent support to the doctrinal revolution brought about by his fellow German Martin Luther: The illiterate peasants were moved more by Durer’s art than by Luther’s texts.

The greatest achievement in the arts in northern Europe in the sixteenth and early seventeenth centuries took place in England, a land that had, up until then, been a bit of a cultural backwater, with the notable exception of Geoffrey Chaucer, whose Canterbury Tales were based on The Decameron by Boccaccio (both works written during the fourteenth century). There is perhaps no way to explain the emergence of the sheer number of men possessing exceptional talent during the reign of Queen Elizabeth, since providing her with much credit for this cultural awakening seems to be unwarranted. In fact, much of what we refer to as the Elizabethan Renaissance occurred during the reign of her cousin and heir, James I.

Although Christopher Marlowe and Ben Jonson are both writers of significant repute, the age produced an unrivaled genius in William Shakespeare (1564–1616). Though little is known of Shakespeare’s life and the question of the provenance of his plays will never be answered to the satisfaction of all, this man, who received little more than a primary school education, apparently was able to author plays such as Hamlet and King Lear, works that reveal an unsurpassed understanding of the human psyche as well as a genius for dramatic intensity.

The Printing Press

The search for new ways to produce text became important in the late medieval period, when the number of literate individuals rose considerably as the number of European universities increased. The traditional method of producing books, via a monk working dutifully in a monastic scriptorium, was clearly unable to meet this heightened demand. Johannes Gutenberg, from the German city of Mainz, introduced movable type to western Europe. Between 1452 and 1453, Gutenberg printed approximately 200 Bibles and spent a great deal of money making his Bibles as ornate as any handwritten version. He eventually went broke. The significant increase in literacy in the sixteenth century supports the theory that few inventions in human history have had as great an impact as the printing press. It is hard to imagine the Reformation spreading so rapidly without the books that informed people of the nature of the religious debate.

THE PROTESTANT REFORMATION

Religious Divisions Around 1550

In western Europe in the year 1500, the simple declarative sentence, “I went to church on Sunday,” could mean only one thing, as only one church existed in the West. At the top of this hierarchical church sat the pope in Rome, to whom all of Europe looked for religious guidance. Several decades later, the Protestant Reformation movement resulted in the great split in Western Christendom, which dethroned the pope as the single religious authority in Europe. Although it took several decades, eventually there was a Catholic response to this challenge known as the Catholic Reformation.

In part, the Reformation of the sixteenth century was a reflection of the ways in which Europe was changing. The humanism of the Renaissance, particularly in the north of Europe, had led individuals to question certain practices such as the efficacy of religious relics and the value to one’s salvation of living the life of a monk. In addition, the printing press had made it possible to produce Bibles in ever greater number, which made the Church’s exclusive right to interpret the Scriptures seem particularly vexing to those who could now read the text themselves. The rise of powerful monarchical states also created a situation in which some rulers began to question why they needed to listen to a distant authority in Rome or Vienna.

One important thing to keep in mind is that on the AP European History Exam, you are not looking for absolute religious truths. So, when dealing with religious questions, leave your personal beliefs at the door and think as a historian.

Problems Facing the Church on the Eve of the Reformation

It is important for the student of the sixteenth-century Reformation to remember that the Reformation is far more than just the story of Martin Luther (1483–1546). While Luther is a central figure in the story, to reduce it simply to his own struggles against the Catholic Church oversimplifies what is actually a complex and compelling story.

The Church was facing significant problems on the eve of the Reformation. Some of these problems resulted from the crisis of the fourteenth century, when the Black Death, a ferocious outbreak of plague, struck the population of Europe. These problems included a growing anticlericalism—a measure of disrespect toward the clergy, stemming in part from what many perceived to be the poor performance of individual clergymen during the crisis years of the plague. Geoffrey Chaucer’s The Canterbury Tales and Boccaccio’s The Decameron reveal some of the satirical edge with which literate society now greeted clergymen. Additionally, this period witnessed a rise in pietism, or the notion of a direct relationship between the individual and God, thereby reducing the importance of the hierarchical Church based in Rome. The fourteenth century was undoubtedly a disaster for the Church, with the papacy under French dominance in the city of Avignon for almost 70 years. It was further damaged by the Great Schism, which for a time resulted in three competing popes excommunicating each other.

Other problems on the eve of the Reformation included a poorly educated lower clergy. Peasant priests, who in many cases knew just a bit of Latin, proved to be unable to put forward a learned response to Luther’s challenge to their Church. Simony, the selling of church offices, was another considerable problem, as was the fact that some clergy held multiple positions, thus making them less than effective in terms of ministering to their flocks.

In response to some of these problems, a number of movements arose in the late Middle Ages that would be declared heretical by the Church. In England, John Wycliffe (1329–1384) questioned the worldly wealth of the Church, the miracle of transubstantiation, the teachings of penance, and, in a foretaste of the ideas of Luther, the selling of indulgences. Wycliffe urged his followers (known for unclear reasons as the Lollards) to read the Bible and to interpret it themselves. To aid in this task, Wycliffe translated the Bible into English.

In Bohemia (the modern-day Czech Republic), Jan Hus (1369–1415) led a revolt that combined religious and nationalistic elements. Hus, the rector of the University of Prague, argued that it was the authority of the Bible and not the institutional church that ultimately mattered. Like Wycliffe, he was horrified by what he saw as the immoral behavior of the clergy. This antagonism toward the clergy and its special role in administering the sacraments led Hus to argue that the congregation should be given the cup during the mass as well as the wafer, something that only clergymen were allowed. Hus was called before the Council of Constance in 1415 by Pope Martin V, and although he was promised safe passage, he was condemned as a heretic and burnt at the stake. In response, his followers in Bohemia staged a rebellion, which took many years to put down.

Martin Luther

The initial issue that first brought attention to Martin Luther (1483–1546) was the debate over indulgences. The selling of indulgences was a practice that began during the time of the Crusades. To convince knights to go on crusades and to raise money, the papacy sold indulgences, which released the buyer from purgatory. Eventually, long after the crusading movement had ended, the Church began to grant indulgences as a means of filling its treasury. In 1517, Albert of Hohenzollern, who already held two bishoprics, was offered the Archbishopric of Mainz. He had to raise 10,000 ducats, so he borrowed the money from the great banking family of the age—the Fuggers. To pay off his debt, the papacy granted him permission to raise money from the preaching of an indulgence, with half of the money going directly to Rome, where the papacy was in the midst of a program to finally complete St. Peter’s Basilica. Johann Tetzel, a Dominican friar, was sent to preach the indulgence throughout Germany with the famous phrase “As soon as gold in the basin rings, right then the soul to heaven springs.”

Luther was horrified by the behavior of Tetzel and tacked up his 95 Theses on the Castle Church at Wittenberg, which was the medieval way of indicating that an issue should be debated. Part of Luther’s complaints dealt with German money going to Rome. Another major point involved control over purgatory. If the pope had control over it, Luther wondered, why didn’t he allow everyone out? Luther believed that a pope could only remit penalties that he himself had placed on someone. Therefore, the pope had no right to sell misleading indulgences.

In a reflection of the power of the printing press, the 95 Theses were quickly printed all over Germany. At first, the papacy was not concerned. Pope Leo X reportedly said he was not interested in a squabble between monks. The Dominicans wanted to charge Luther with heresy, but Luther soon found himself with a large number of supporters.

Luther began to move in a more radical direction. In part, a great deal of his attack on the Church was based on his own fears that he was unworthy of salvation. Back in 1505, he was caught in a thunderstorm and a bolt of lightning struck near him. He cried out, “St. Anne help me; I will become a monk.” Luther kept his promise and joined the Augustinian order. However, Luther was dissatisfied leading the life of a monk. In later years, he claimed that if any monk could have been saved by what he termed “monkery,” it was he:

Though I lived as a monk without reproach, I felt that I was a sinner before God with an extremely disturbed conscience. I could not believe that He was placated by my satisfaction. I did not love, yes, I hated the righteous God who punishes sinners, and I was angry with God.

Still troubled, Luther went on to be appointed Professor of Scriptures in Wittenburg in Electoral Saxony (northern Germany).

Following the publication of his 95 Theses, Luther engaged in a public debate on these issues in Leipzig, where John Eck, a prominent theologian, challenged him. Eck then called Luther a Hussite, while Luther claimed that Hus had been unjustly condemned at the Council of Constance. After this debate, Luther spent the year 1520 writing three of his most important political tracts.

1) In his Address to the Christian Nobility, he urged that secular government had the right to reform the Church.

2) In On the Babylonian Captivity of the Church, Luther attacked other teachings of the Church, such as the sacraments.

3) Finally, in Liberty of a Christian Man, he hit on what would become the basic elements of Lutheran belief: Grace is the sole gift of God; therefore, one is saved by faith alone, and the Bible is the sole source of this faith.

In response to these works, Pope Leo X finally decided he had to act. He issued a papal bull (an official decree) that demanded that Luther recant the ideas found in his writings or be burnt as a heretic. In a highly symbolic gesture, Luther publicly burned the bull to show that he no longer accepted papal authority. In turn, the pope excommunicated Luther.

Luther was fortunate in that, unlike Hus, he had some important patrons. Some North German princes, such as Frederick the Elector of Saxony, were either sympathetic to Luther’s ideas or at least wanted him to be given a public hearing. To that end, in 1521 Luther appeared before the Diet of Worms, a meeting of the German nobility. In one of the most famous scenes in history, Luther was asked by Charles V, the Holy Roman Emperor, “Do you or do you not repudiate your books and the errors they contain?” Luther began to answer with a quivering voice but then gathered his courage and said:

Unless I am convicted by Scripture and plain reason—I do not accept the authority of popes and councils, for they have contradicted each other—my conscience is captive to the Word of God. I cannot and I will not recant anything, for to go against conscience is neither right nor safe. God help me. Amen.

In response, Luther was placed under the ban of the Empire but was safely hidden over the next year in Wartburg Castle by the Elector of Saxony. In the castle, Luther continued to write prolifically and finished some of his most important works, including a translation of the Bible into German.

Since he now considered papal authority to be a human invention, Luther and his friend Philip Melanchthon decided to form a new church based on his revolutionary ideas free from papal control. Instead of the seven sacraments of the Catholic Church (Marriage, Ordination, Extreme Unction, Confirmation, Penance, Communion, Baptism), he reduced them to two—baptism and communion. Luther changed the meaning of the latter (also called the Holy Eucharist) by rejecting the Catholic idea of transubstantiation, the miraculous transformation of the bread and wine into the flesh and blood of Christ, an act that could be performed only by an ordained priest. Instead, Luther claimed that Christ was already present in the sacrament. Luther also did away with the practice of monasticism and the insistence on the celibacy of the clergy. He himself went on to have a happy marriage with a former nun with whom he had several children.

Why Did the Reformation Succeed?

Within three decades after Luther posted his 95 Theses, Protestantism had spread to many of the states of northern Germany, Scandinavia, England, Scotland, and parts of the Netherlands, France, and Switzerland. There are a number of possible explanations for its phenomenal success.

The Origins of the Term Protestantism

The term today is used very broadly and means any non-Catholic or non-Eastern Orthodox Christian. Initially, it referred to a group of Lutherans who in 1529 attended the Diet of Speyer in an attempt to work out a compromise with the Catholic Church and ended up “protesting” the final document that was drawn up at its conclusion.

Luther and the church that he founded were socially conservative and therefore not a threat to the existing social order. Luther’s conservatism can be seen clearly in the German Peasants’ Revolt of 1525. The revolt was the result of the German peasants’ worsening economic conditions and their belief, articulated in the Twelve Articles, that Luther’s call for a “priesthood of all believers” was a message of social egalitarianism. It certainly was not. The revolt and the distortion of his ideas horrified Luther. He published a violently angry tract entitled “Against the Robbing and Murderous Hordes of Peasants,” in which he urged that no mercy be shown to the revolutionaries.

Another reason Luther’s movement was allowed to grow was that Luther was willing to subordinate his church to the authority of the German princes. As his response to the Peasants’ Revolt shows, political questions were not of great importance to Luther, who felt that what occurred on this Earth was secondary to what truly mattered—the Kingdom of Heaven. He was not critical of the German princes who created state churches under their direct control. Luther also encouraged German princes to confiscate the lands of the Catholic Church, and many rulers did not have to be asked twice, in part because one-quarter of all land in the Holy Roman Empire was under Church control.

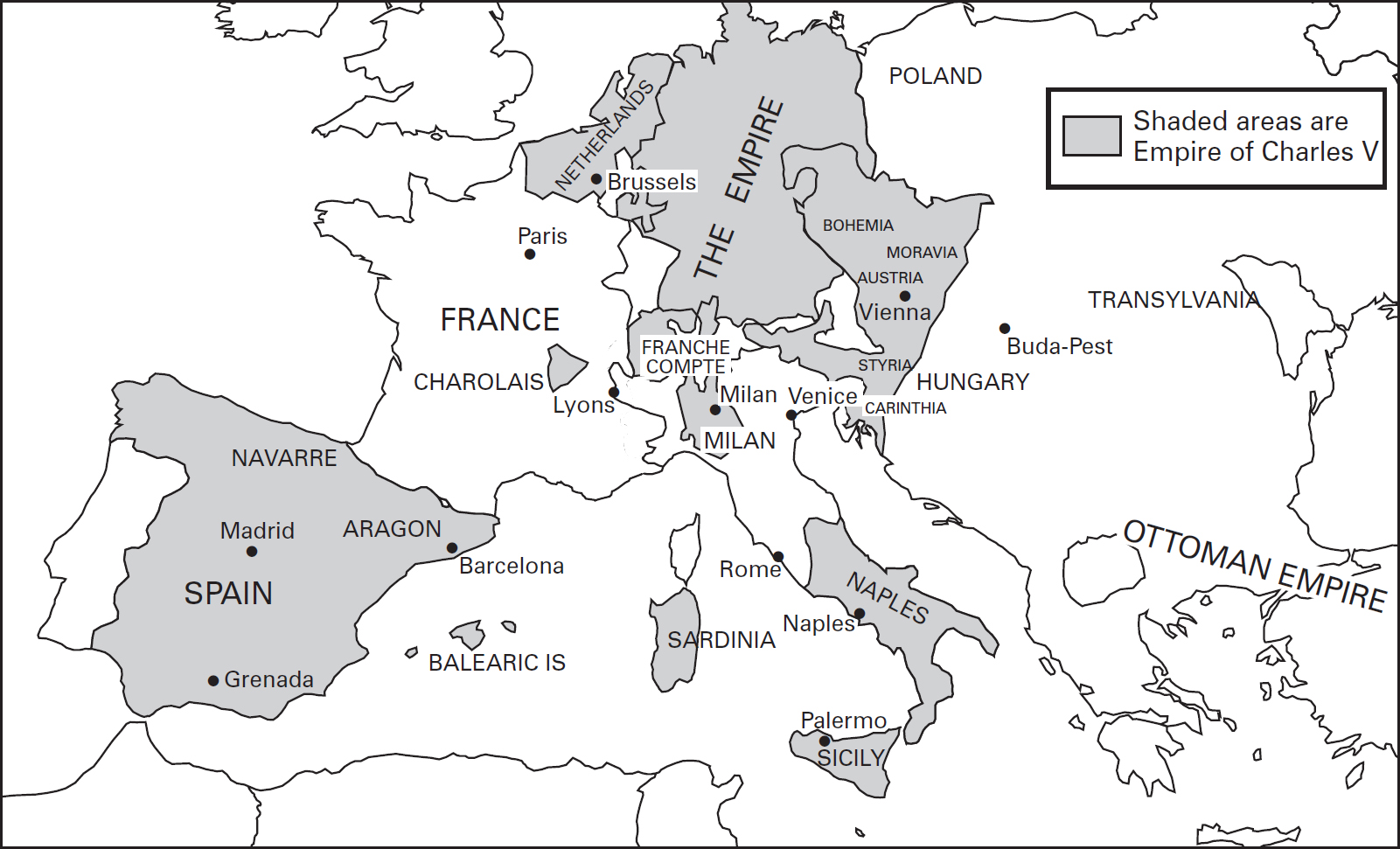

Political issues within the Holy Roman Empire produced turmoil. When the Emperor Maximilian died in 1519, his grandson and heir Charles V was caught in a struggle with the French King Francis I to see who would sit on the imperial throne. Although Charles V was able to muster enough bribe money, borrowed from the Fuggers, to convince the rulers of the electoral states to select him, he was ultimately unable to effectively control his empire. Also, as ruler of a vast multinational empire that included Spain and its possessions in the New World, the Netherlands, southern Italy, and the Habsburg possessions in Austria, Charles had huge commitments. He was unable to deal with the revolt in Germany for several critical decades because he was involved in extended wars with France as well as with the powerful Ottoman Empire to the east.

In the 1540s, the Schmalkaldic War was fought between Charles and some of the Protestant princes. While for a time Charles had the upper hand, by 1555 he was forced to sign the Peace of Augsburg. This treaty granted legal recognition of Lutheranism in those territories ruled by a Lutheran ruler, while a Catholic ruler ensured that the territory remained Catholic.

The Empire of Charles V

Radical Reformation

Historians sometimes use the term “Radical Reformation” to describe a variety of religious sects that developed during the sixteenth century, inspired in part by Luther’s challenge to the established Church. Many felt that Luther’s Reformation did not go far enough in bringing about a moral transformation of society.

One such group was the Anabaptists, who upon reading the Bible, began to deny the idea of infant baptism. Instead they believed that baptism works only when it is practiced by adults who are fully aware of the decision they are making. Eventually, rebaptism, as the practice became known, was declared a capital offense throughout the Holy Roman Empire, something on which both the pope and Luther heartily agreed. Attacks against Anabaptists became even worse following the Anabaptist takeover of the city of Munster in 1534, during which time they attempted to create an Old Testament theocracy in which men were allowed to have multiple wives. Following the capture of Munster by combined Catholic and Protestant armies, Anabaptism moved in the direction of pacifism under the leadership of Menno Simons.

Besides Anabaptists, other groups such as the Antitrinitarians, who denied the scriptural validity of the Trinity, were part of the Radical Reformation. Both Catholics and Lutherans hunted down those who held such beliefs.

Zwingli and Calvin

Shortly after the appearance of Luther’s 95 Theses, Ulrich Zwingli’s (1484–1531) teachings began to make an impact on the residents of the Swiss city of Zurich. Like Luther, Zwingli accused monks of indolence and high living. In 1519, Zwingli specifically rejected the veneration of saints and called for the need to distinguish between their true and fictional accounts. He announced that unbaptized children were not, in fact, damned to eternal hellfire. He questioned the power of excommunication. His most powerful statement, however, was his attack on the claim that tithing was a divine institution. Unlike Luther, however, Zwingli was a strict sacramentarian in that he denied all the sacraments. To him, the Last Supper was a memorial of Christ’s death and did not entail, as it did for Luther, the actual presence of Christ. Zwingli was also a Swiss patriot in ways that Luther could not be called a German patriot. Zwingli was far more concerned with this world and called for social reform. He died leading the troops of Zurich against the Swiss Catholic cantons in battle.

John Calvin (1509–1564) was born in France, although he eventually settled in Geneva, Switzerland. His main ideas are found in his Institutes of the Christian Religion, in which he argued that grace was bestowed on relatively few individuals, and the rest were consigned to hell. This philosophy of predestination was the cornerstone of his thought, and one that does not make any room for free will. This was contrary to everything that the Catholic Church taught about death. Although many of the Catholic Church’s practices, such as the sale of indulgences, were extremely corrupt, the Church also taught that people have the ability to save their souls following death. Calvin preferred for his followers to focus on correct living in earthly matters. He was a strict disciplinarian who did his best to make Geneva the new Jerusalem. He closed all the taverns and inflicted penalties for such crimes as having a gypsy read your fortune.

Calvinism began to spread rapidly in the 1540s and 1550s, becoming the established church in Scotland, while in France—where the Calvinists were known as Huguenots—only a significant minority joined. In many ways, it can be said that Calvinism saved the Protestant Reformation, since in the mid-sixteenth century, it was a dynamic Calvinism—rather than the increasingly moribund Lutheranism—that stood in opposition to a newly aggressive Catholic Church during the Catholic Counter-Reformation. It’s also worth noting that it was a group of English Calvinists (who were called Puritans) who grew tired of religious harassment from the mainstream Anglican church and fled England to Holland. In the shipbuilding capital of Europe, they saved enough money to build a pair of ships, which they used to sail across the Atlantic Ocean, where they established a new colony in Massachusetts based on religious freedom. Yes, these were the Pilgrims.

THE ENGLISH REFORMATION

The English Reformation was of a different nature—a political act rather than a religious act as in other parts of Europe. Henry VIII (reign 1509–1546), the powerful English monarch, was supportive of the Catholic Church. He even criticized Martin Luther in a pamphlet that he wrote, The Defence of the Seven Sacraments. Henry was never comfortable with Protestant theology. He did not believe in salvation by faith and saw no need to limit the role of the priest. The story of the English Reformation begins with what became known as the “King’s Great Matter,” which involved King Henry VIII’s attempt to end his marriage to his Spanish wife, Catherine of Aragon. Henry had grown concerned that he did not have a male heir, and he began to question whether Catherine’s failure to produce sons (a man of his times, he blamed his wife) was a sign of God’s displeasure at his marriage to Catherine, who had earlier been married to Henry’s deceased older brother. Because the Catholic Church did not recognize divorce, Henry would have to go through the process of getting an annulment. During this time, Henry fell in love with a young woman at his court, Anne Boleyn, who virtuously refused to sleep with him unless he made her his queen.

When the papacy showed no signs of granting the annulment, primarily because Catherine was the aunt of the powerful Charles V, Henry decided to take authority into his own hands. Starting in November 1529 and continuing for seven years, he began what became known as the Reformation Parliament, which Henry used as a tool to give him ultimate authority on religious matters. This parliament would come to be very useful, since by 1533, Henry was on a short timetable. He had bribed Anne Boleyn into joining him in bed. Three months later she was pregnant and had secretly married Henry, although Henry was still married to Catherine as well. If Henry was to be saved from bigamy, and if his child was to be legitimate, he had only eight months to end his marriage to Catherine. Henry decided the only way to do this was by cutting off the constitutional links that existed between England and the papacy. In April 1533, Parliament enacted a statute known as the Act in Restraint of Appeals, which declared that all spiritual cases within the Kingdom were within the King’s jurisdiction and authority and not the pope’s. A month later, Henry appeared before an English church tribunal headed by the man he selected to be Archbishop of Canterbury. The tribunal declared that his marriage to Catherine was null and void and that Anne Boleyn was his lawfully wedded wife. That September, a child was born, but it was a baby girl, Elizabeth Tudor, instead of the boy Henry so desperately wanted. Eventually, Henry would marry a total of six times; his third wife, Jane Seymour, provided him with a son, Edward. In 1534, the English Reformation was capped off by the Act of Supremacy, which acknowledged the King of England as the Supreme Head of what became known as the Church of England.

While Henry may have been merely interested in creating what we might call Catholicism without the pope—in that he wanted to keep all the aspects of Catholic worship without acknowledging the primacy of the pope—it proved to be difficult to stem the tide of change. Henry himself played a role in this by closing all English monasteries and confiscating their lands. The brief reign of his son Edward VI (r. 1547–1553) saw an attempt to institute genuine Protestant theology into the church that Henry had created.

During the similarly short reign of his half-sister Mary Tudor (r. 1553–1558), the daughter of Catherine of Aragon and wife of the fanatically Catholic Philip II of Spain, there was an attempt to bring England back into the orbit of the Catholic Church. While succeeding in restoring the formal links between England and the papacy, Mary found that many still held to their Protestant beliefs. To end this heresy, she allowed for several hundred Englishmen to be burnt at the stake, thus earning her the sobriquet “Bloody Mary.” It was only during the long, successful reign of her half-sister Elizabeth (r. 1558–1603), the daughter of Anne Boleyn, that a final religious settlement was worked out, one in which the Church of England followed a middle-of-the-road Protestant course.

THE COUNTER-REFORMATION

Although it took several decades to be effective, eventually there was a Catholic response to the Protestant Reformation. Initially, historians referred to this movement as the Counter-Reformation, although today it is more commonly known as the Catholic Reformation. To a certain extent, both labels are appropriate. It was Counter-Reformation in the sense that the Catholic Church was taking steps to counteract some of the successes of the Protestant side. Among these steps was the creation of the notorious Index of Prohibited Books, including works by writers such as Erasmus and Galileo. Also, the medieval institution of the papal Inquisition was revived, and individuals who were deemed to be heretics were put to death for their religious beliefs. The term Catholic Reformation is also apt in that the Catholic Church has a long tradition of adjusting to changed conditions, whether it was the papal Reform Movement of the eleventh century or, more recently, the Second Vatican Council of the 1960s.

The centerpiece of the Catholic Reformation was the Council of Trent (1545–1563). Unlike the medieval conciliar movement, which sought to place the papacy under the control of a church council or parliament, the Council of Trent was dominated by the papacy and, in turn, enhanced its power. The council took steps to address some of the issues that had sparked the Reformation, including placing limits on simony, the selling of church offices. Recognizing that the poorly educated clergy were a major problem, the council mandated that a seminary for the education of clergy should be established in every diocese. The Council of Trent refused to concede any point of theology to the Protestants. Instead they emphatically endorsed their traditional teachings on such matters as the sacraments, the role of priests, and the belief that salvation comes from faith as well as works, and that the source for this faith was the Bible and the traditions of the Church. Although it is incorrect to say that the council created the idea of the baroque style of art, the council was critical of what it deemed to be the religious failings of the mannerist style and urged that a more intensely religious art be created, something that did play a role in the development of the early baroque.

Perhaps the greatest reason for the success of the Catholic Reformation was the founding of the Society of Jesus (Jesuits) organized by Ignatius Loyola (1491–1556), a Spanish noble who was wounded in battle and spent his recuperation time reading various Catholic tracts. After undergoing a religious conversion, he attempted, not unlike Luther, to reconcile himself to God through austere behavior. He became a hermit but still felt that something was amiss. While Luther, in his search for spiritual contentment, decided that the Bible was the sole source of faith, Loyola believed that even if the Bible did not exist, there was still the spirit.

Loyola’s ideas are laid out in his Spiritual Exercises; one passage in particular states his belief in total obedience to the Church:

To arrive at complete certainty, this is the attitude that we should maintain: I will believe that the white object I see is black if that should be the desire of the hierarchical church, for I believe that linking Christ our Lord the Bridegroom and His Bride the church, there is one and the same Spirit, ruling and guiding us for our souls’ good. For our Holy Mother the church is guided and ruled by the same Spirit, the Lord who gave the Ten Commandments.

This total and complete loyalty is why the Jesuit order, although at first under suspicion by a cautious papacy uncomfortable with Loyola’s mysticism, would be accepted as an official order of the Church in a papal bull in 1540. The Jesuits began to distinguish themselves as a teaching order and also worked as Catholic missionaries in places where Lutheranism had made large inroads. Poland served as a strong example of where Catholicism was re-prosthelitized.

THE PORTUGUESE AND SPANISH EMPIRES

If geography is destiny, then it is not surprising that the Portuguese would look to the sea. Living in a land that was not well suited to farming, the Portuguese had always looked to distant lands for sources of wealth. In 1415, Prince Henry the Navigator, a younger son of the King of Portugal, participated in the capture of the North African port of Ceuta from the Muslims. This conquest spurred his interest in Africa. It also inspired him to sponsor a navigational school in Lisbon and a series of expeditions, manned mainly by Italians, which aimed not only to develop trade with Africa but also to find a route to India and the Far East around Africa and thereby cut out the Italian middlemen.

In 1487, a Portuguese captain, Bartholomew Dias, sailed around the Cape of Good Hope at the tip of Africa. A decade later, in 1498, Vasco da Gama reached the coast of India. The Portuguese defeated the Arab fleets that patrolled the Indian Ocean by being the first to successfully mount cannons on their ships and also by deploying their ships in squadrons rather than individually, which gave them a huge tactical advantage. The Portuguese established themselves on the western coast of India and for a while controlled the lucrative spice trade.

With the Portuguese having a head start on the African route to the Indian Ocean, the Spanish decided to try an Atlantic route to the East. Christopher Columbus, a Genoese sailor, set sail on August 2, 1492, certain that he would find this eastern route. Although Columbus was not unique in insisting that the world was round, he did believe he would fulfill medieval religious prophesies that spoke of converting the whole world to Christianity. After a thirty-three-day voyage from the Canary Islands, Columbus landed in the eastern Bahamas, which he insisted was an undeveloped part of Asia. He called the territory the “Indies” and the indigenous population “Indians” and noted ominously in his diary that they were friendly and gentle and therefore easy to enslave.

Although Columbus’s failure to locate either gold or spices during his voyages was a disappointment, within a generation, others built on Columbus’s discoveries. The most important of the journeys was undertaken by Ferdinand Magellan in 1519, who set out to circumnavigate the globe. Although Magellan did not live to see the end of his voyage (he died in the Philippines), he did prove that the territory where Columbus landed was not part of the Far East but rather an entirely unknown continent, a continent that the Spanish planned to conquer.

In 1519, Hernán Cortés landed on the coast of Mexico with a small force of 600 men. He had arrived at the heart of the Aztec Empire, a militaristic state, which through conquest had carved out a large state with a large central capital, Tenochtitlán (modern-day Mexico City). The Aztecs were less than popular with the people they conquered, primarily because they practiced human sacrifice to appease their gods. These conquered people felt no loyalty to the Aztec state and were willing to cooperate with the Spanish.

The Aztecs viewed the light-skinned Spaniards, who were riding on horses (unknown at this time in North and South America), wearing armor, and carrying guns, as gods. At first, Montezuma, the Aztec ruler, tried to appease them with gifts of gold. Unfortunately for the Aztecs, this just further whetted the appetite of the Spanish, who seized the capital city and took Montezuma hostage. He died mysteriously while in Spanish captivity. While rebellions against Spanish rule continued, the Aztec ability to fight was sapped by smallpox and other European diseases foreign to the indigenous peoples. By 1521, Cortés declared the former Aztec Empire to be New Spain.

The Spanish also succeeded in destroying another great civilization, the Inca Empire of Peru. Like the Aztecs, the Incas had carved out a large empire by conquering and instigating harsh rule over many other tribes. In 1531, Francisco Pizarro, a Spanish soldier, set out for Peru with a tiny force of approximately 200 men. Pizarro, following Cortés’s brutal example, treacherously captured the Inca Emperor Atahualpa, who then had his subjects raise vast amounts of gold for ransom. By 1533, Pizarro had grown tired of ruling through Atahualpa, and he had him killed. Once again, Western technology and diseases sapped the indigenous population’s ability to fight back, and while it took longer for the Spanish to secure their hold over the Inca territories, by the 1560s, they had stamped out the last bit of resistance.

The impact of this age of exploration and conquest was immense, not just for Europe but for the entire globe. The Spanish set out to create haciendas, or plantations, to exploit both the agricultural and mineral riches of the land. The indigenous population, compelled to work under a system of forced labor called encomienda, continued to die at an incredible pace from both disease and overwork. So to provide labor for their estates, the Spanish and Portuguese began to take captured Africans from their homeland to serve on the farms and in the mines of the New World. It has been estimated that by the time the slave trade ended in the early nineteenth century, almost 10 million Africans were abducted from Africa, with countless numbers dying as a result of the inhumane conditions on the difficult overseas passage.

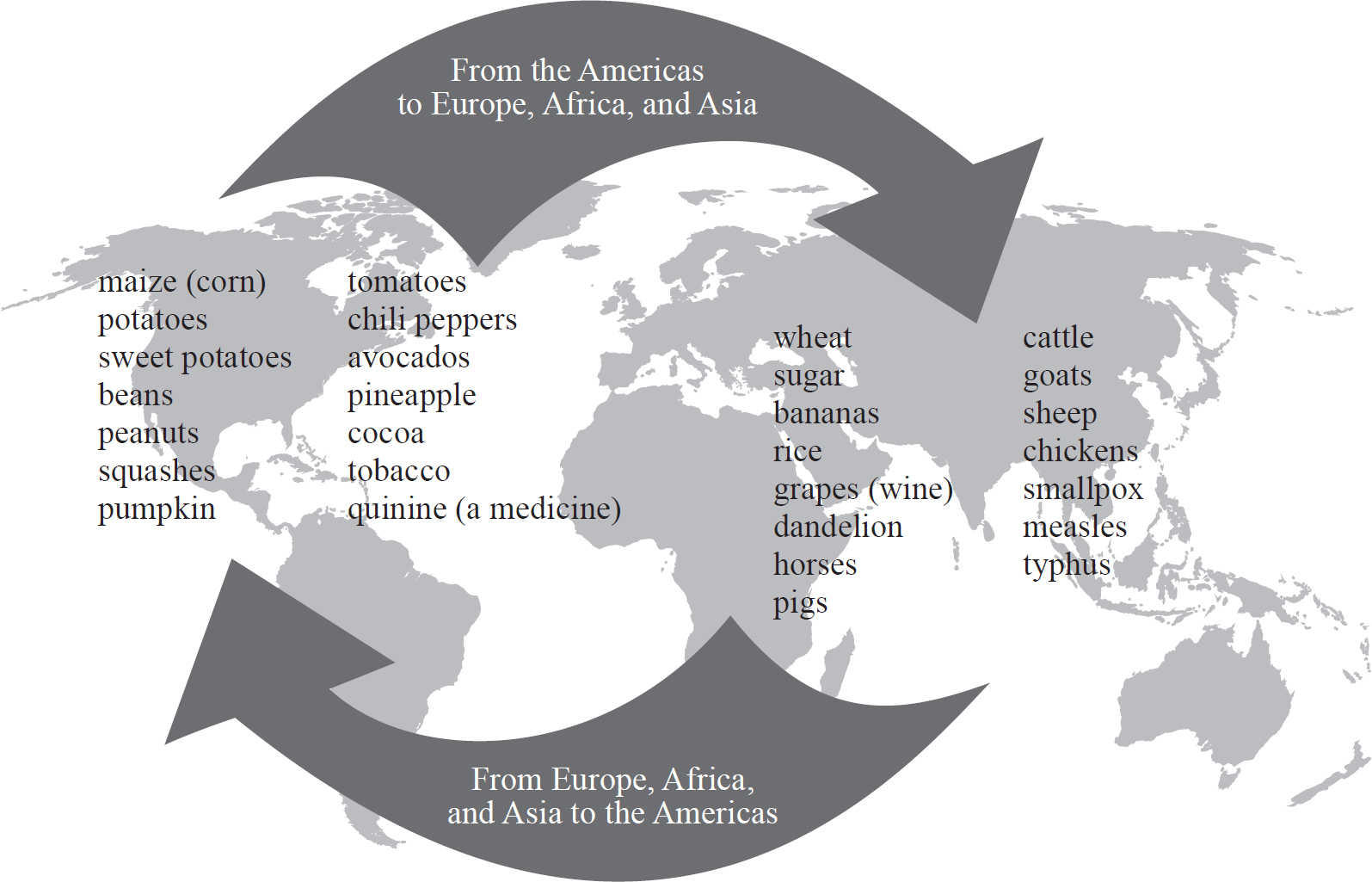

Another consequence of the Spanish and Portuguese empires in the New World was what became known as the Columbian Exchange—the transatlantic transfer of animals, plants, diseases, people, technology, and ideas among Europe, the Americas, and Africa. (See the map on the next page.) As Europeans and Africans crisscrossed the Atlantic, they brought the Old World to the New and back again. From the European and African side of the Atlantic, horses, pigs, goats, chili peppers, and sugarcane (and more) flowed to the Americas. From the American side, squash, beans, corn, potatoes, and cacao (and more) made their way back east. Settlers from the Old World carried bubonic plague, smallpox, typhoid, influenza, and the common cold into the New, then carried Chagas and syphilis back to the Old. Guns, Catholicism, and slaves also crossed the Atlantic. Never before had so much been moved across the oceans, as ship after ship carried the contents of one continent to another.

THE DEVELOPMENT OF MONARCHICAL STATES

Tools of statecraft, such as permanent embassies in foreign lands, were first developed in the city-states of Renaissance Italy. Large, unified nation-states began to develop in northern Europe during the early modern period. These city-states ultimately came to dominate the Italian peninsula and contributed to the transition away from the medieval notion of feudal kingship. Prior to the sixteenth century, the king was not an absolute ruler; instead he had to rule with the consent of his great vassals. In the age of the new monarchical state, it was deemed that monarchical power was God-given and therefore by its very nature absolute. Although in the Middle Ages, parliamentary institutions developed throughout Europe as a means of placing limits on kings, in the early modern period, thought shifted. The sixteenth-century French philosopher Jean Bodin wrote of this new style of monarchy:

It is the distinguishing mark of the sovereign that he cannot in any way be subject to the commands of another, for it is he who makes law for the subject, abrogates laws already made, and amends absolute law.

The French monarchy is the most important example of how this power shift came about. It was not an easy victory for the French monarchy, which had to deal with assorted aristocratic and religious conflicts that threatened to destroy the state. Eventually, under Louis XIV, France created a centralized monarchy in which the power of the king was absolute, although it came at a high price as it helped pave the way for the late eighteenth-century French Revolution. England serves as a very different model. In England, the Stuart monarchs, who reigned for most of the seventeenth century, were interested in adopting French-style royal absolutism but found that the English Parliament stood in their way. Eventually, England became embroiled in what one historian has labeled as a “century of revolution,” which eventually resulted in the supremacy of Parliament over the monarchy.

Be aware of these important characteristics of the new nation-states:

1. Growing Bureaucratization

Across Europe, salaried officials began to depend on the monarchy for their livelihood. In France, the monarchy established the new office of intendant, which employed individuals to collect taxes on behalf of the monarch. Corruption was still a part of this system, as was the practice of buying and selling royal offices to satisfy the short-term financial needs of the monarch. England was the exception to this trend. In England, the older system of cooperation between the crown and its leading subjects continued.

2. Existence of a Permanent Mercenary Army

In the late medieval/early modern periods, a revolution in warfare came about. In the fourteenth century, Swiss mercenary infantrymen lined up in a phalanx of 6,000 men and used their pikes to kill aristocratic horsemen, but by the end of the century, gunpowder further eroded the dominance of the mounted knight and made feudal castles far easier to conquer. The rising cost of warfare, most particularly the need to provide for an army on an annual (as opposed to occasional) basis, played into the hands of the developing monarchical state, which alone could tap into the necessary resources. Again, England was the exception, since it did not establish a permanent army until the end of the seventeenth century when it was firmly under parliamentary control.

3. Growing Need to Tax

This is an instance where 1 + 2 = 3. Countries like France basically faced a vicious circle: Monarchs were in constant need of taxes to pay for their permanent armies, while it was the army that the monarchy needed to ensure control over a rebellious peasantry who resented the high rate of taxation. Traditionally, medieval monarchs were supposed to live off their own incomes, although in the early modern period this was becoming impossible due to the Price Revolution and the increased costs of managing a centralized state.

ITALY

Not every part of Europe followed this process of national consolidation under a centralizing monarchy. The Italian peninsula remained divided throughout this period, and thus it became an easy target for ambitious monarchs of centralized states such as France and Spain.

The Treaty of Lodi (1454) had provided for a balance of power among the major Italian city-states. It created an alliance between long-term enemies Milan and Naples and also included the support of Florence. Their combined strength was enough to ensure that outside powers would stay out of Italian affairs. This system came to an end in 1490, when Ludovico il Moro, upon becoming despot of Milan, initiated hostilities with Naples and then four years later invited the French into Italy to allow them to satisfy their long-standing claims to Naples. Charles VIII, the King of France, didn’t have to be asked twice; he immediately ordered his troops across the Italian Alps.

Charles and his forces crossed into Florence, where a radical Dominican preacher, Savonarola (1452–1498), had just led the Florentine population in expelling the Medici rulers and then had established a puritanical state. This complete religious and political transformation of the city marked the end of Florence’s leading role in Renaissance scholarship and art. Eventually, by 1498, Ludovico il Moro recognized the folly of what he had wrought and joined an anti-French Italian alliance that ultimately succeeded not only in expelling the French but also in restoring the Medici in Florence. The Medici promptly burnt Savonarola at the stake with the support of the papacy, which hated the Dominican friar because of his pre-Lutheran call for a complete overhaul of the Church, including the institution of the papacy.

The damage to the independence of the Italian city-states had already been done. Throughout the sixteenth century, Italy became the battlefield in which Spain and France fought for dominance. The collapse of Italian independence was the historical context in which Niccolò Machiavelli wrote what is generally seen as the first work of modern political thought, The Prince (1513). Machiavelli had happily served his beloved Florentine Republic as a diplomat and official in the chancellery. When the Republic was overthrown by the Medici, Machiavelli was forced into exile to his country estate. The Prince is a résumé of sorts in which Machiavelli tried to convince the Medici to partake of his services. Although some scholars have debated whether he was serious about his ideas, it does appear that Machiavelli was genuinely horrified by the increasing foreign domination of the Italian peninsula and believed that only a strong leader using potentially ruthless means could unify Italy and expel the foreigners.

ENGLAND

The Tudors

England had achieved a measure of unity under a centralized monarchy in the medieval period, well before its continental counterparts. The fifteenth-century Wars of the Roses (commonly known to us, although a bit inaccurately, through the plays of Shakespeare) were not aristocratic attempts to break the power of the monarchy but rather a series of civil wars to determine which aristocratic faction, York or Lancaster, would dominate the monarchy. In the end, it was a junior member of the Lancastrian family, Henry Tudor (Henry VII), who won central authority in England when he established the Tudor dynasty following his defeat of Richard III in 1485 at the battle of Bosworth Field.

Following the death of his autocratic father in 1509, Henry VIII became king and maintained his father’s policies to strengthen the crown. The near total decimation of aristocratic opponents during the Wars of the Roses and an expanding economy, which benefited the Tudor dynasty throughout the sixteenth century, helped the King to restore royal authority. Henry created a small but efficient bureaucracy that made the King’s intentions known throughout the land. Henry, however, believed that his sovereignty would not be manifest so long as England was under the religious leadership of the papacy. In 1534, he made a political—not a religious—decision when he broke with Rome and created the Church of England. Although their tenures on the throne were short and full of religious tension, Henry VIII’s children, Edward VI and Mary Tudor, enjoyed the benefits of the restored prestige of the monarchy, which resulted from the efforts of Henry VII and Henry VIII.

The greatest of all the Tudors was Queen Elizabeth (r. 1558–1603), Henry VIII’s daughter with Anne Boleyn. Elizabeth was an intelligent woman who had been educated in the Italian humanist program of classical studies. She was a diligent worker and had excellent political instincts like her father. Also like her father, Elizabeth knew how to select able ministers who would serve the crown with distinction—men such as William Cecil (Lord Burghley)—but she always kept herself as the ultimate decision maker in the land. Elizabeth used the prospect of marriage as a diplomatic tool and allowed almost every single ruler in Europe to imagine that he could possibly marry her—a powerful way to build alliances whenever the need arose. Whether she truly was the “Virgin Queen” is a question that no one—not even the wise folks who write the questions for the AP exam—could ever answer. She did seem to regard marriage as incompatible with her sovereignty. Yet by staying single, she exposed England to the risk of religious war, since as long as she remained single, the Catholic Mary Stuart, the ruler of Scotland, was her legal heir.

The relationship between England and Scotland was a complex affair that continued to plague both lands throughout the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries. For years, Mary lived as Elizabeth’s prisoner, following a rebellion by Scottish nobles that forced her from the throne. Elizabeth treated Mary as the rightful ruler of Scotland and the probable heir to the English crown, though she kept her under house arrest because she feared that Mary was plotting against her. Only after Mary conspired with Philip II of Spain did Elizabeth decide to settle relations with the Scots and distance herself from Mary. In the Treaty of Berwick in 1586, she entered into a defensive alliance with Scotland; she recognized James, Mary’s son who was being raised as a Protestant, as the lawful king; gave him an English pension; and while she never specifically said so, let it be known that James was the heir to her throne. In 1587, Elizabeth finally took a step that she had been reluctant to take: She ordered the execution of Mary, Queen of Scots.

In 1588 came the greatest moment in Elizabeth’s reign—the defeat of Philip II’s Spanish Armada, which ensured that England would remain Protestant and free from foreign dominance. Although at least part of Elizabeth’s authority gradually eroded as she grew older and people began to look beyond her reign to the future, the decades that followed the Armada conquest were also a period of an incredible cultural flourishing. This was the age of Shakespeare, Christopher Marlowe, Ben Jonson, and Edmund Spenser; and while Elizabeth may not have been a significant direct patron of this English Renaissance, the stability that she provided England during her reign allowed it to take place.

SPAIN

Prior to the fifteenth century, Spain was divided into several Christian kingdoms in the north, while the south had been under Islamic control since the eighth century. The 1469 marriage of Ferdinand, King of Aragon, and Isabella, Queen of Castile, laid the groundwork for the eventual consolidation of the peninsula, with the final stage of the Reconquista taking place in 1492, when their armies conquered the last independent Islamic outpost in Spain—the southern city of Grenada. The same year also marks the beginning of a new wave of religious bigotry, as the ardently Catholic Ferdinand and Isabella began to demand religious uniformity in their lands and formally expelled the Jewish population that had been established in Spain since the time of the Roman Empire. Those Jews and Moors who converted so they could remain in Spain were later hounded by the Spanish Inquisition, an effective method that the Spanish monarchy would later use to root out suspected Protestants.

Through a series of well-planned marriages, Ferdinand and Isabella’s grandson, Charles V, eventually controlled a vast empire that dominated Europe in the first half of the sixteenth century. His Spanish possessions were the primary source of his wealth and also supplied him with the tough Castilian foot soldiers who were the best in Europe. When Charles V—exhausted from his struggles to destroy Protestantism in the Holy Roman Empire—abdicated in 1556, he gave his brother Ferdinand (whom he disliked intensely) the troublesome eastern Habsburg lands of Austria, Bohemia, and Hungary as well as his title of Holy Roman Emperor, while Charles’s son Philip (r. 1556–1598) received the more valuable part of the empire—Spain and its vast holdings in the New World, along with southern Italy and the Netherlands.

Philip gained a vast wealth from the New World’s silver mines. Yet surprisingly, Philip spent most of his reign in debt as he used his riches to maintain Spanish influence. In the Mediterranean, the Spanish fought for supremacy against the Ottoman Empire and won a notable success against that eastern power at the Battle of Lepanto in 1571. In northern Europe, however, Philip was caught in a quagmire when he attempted to put down a revolt in the Netherlands. This revolt combined religious and nationalistic ideas, as did the whole Reformation, and began in 1568 following an attempt by Philip to impose the doctrines of the Council of Trent and the Inquisition in a land where Calvinism had made significant inroads, particularly among key members of the aristocracy. For the next several decades, Philip expended huge amounts of money to try to restore Spanish control. Inquisition-based efforts such as the Duke of Alva’s Council of Troubles (aka the “Council of Blood”) failed, as did the effort of military hero Don Juan. It was for this reason that Philip launched the great Spanish Armada in 1588 as an attempt to conquer England, which, under Queen Elizabeth’s rule, was aiding the Dutch rebels. By 1609, an exhausted Spain conceded virtual independence to the northern provinces of the Netherlands (while still maintaining control over the southern part of the country) and in 1648 formally acknowledged their independence.

Golden Age in Spain

The sixteenth and early seventeenth centuries were a cultural golden age that featured the writings of Cervantes (1547–1616), possibly Spain’s greatest writer, whose masterpiece, Don Quixote, bemoans the passing of the traditional values of chivalry in Spain. It was also a period of remarkable Spanish painters such as the Greek-born El Greco (1541–1614), whose magnificent yet somber works reveal much about a Spain that appeared to have it all, only to find it could not maintain its preeminent European position. In fact, the golden age of Spain did prove to be short-lived. The constant wars, the effects of the Price Revolution, and the economic collapse of the Castilian economy led to a decline in Spain’s power by the end of the seventeenth century.

THE HOLY ROMAN EMPIRE

The Holy Roman Empire, a large “state” that straddled central Europe, can be said to date back to 962, when the Saxon King Otto I was crowned emperor in Rome by the pope. In the late-tenth and eleventh centuries, the Empire was the most powerful state in Europe, but it was eventually weakened as a result of a series of conflicts with the papacy. While lacking the soldiers to stem the ambitions of the Holy Roman emperors, successive popes were able to find support among the German nobility, who chafed under strong imperial leadership. By 1356, the practice of electing the emperor was formally defined in the Golden Bull of Emperor Charles IV. This document, which granted to seven German princes the right to elect an emperor, made it clear that the emperor held office by election rather than hereditary right. The electors usually chose weak rulers who would not stand in the way of their own political ambitions.

In the ensuing centuries, the empire continued to splinter into numerous semi-autonomous territorial states so that by 1500 it consisted of more than 300 semi-autonomous entities over which the emperor ruled but had very little actual authority. Charles V, the powerful Habsburg (also spelled Hapsburg) ruler who was elected emperor in 1519, attempted to establish genuine imperial control over the state. He soon found that the Lutheran Reformation provided a new weapon for those German princes and cities that wanted to avoid losing their independence.

The Peace of Augsburg (1555) signified the end of the religious wars in the time of Charles V, who now agreed to adhere to the basic principle that the prince decides the religion of the territory. The treaty, however, did not grant recognition to Calvinists, thus creating a problem when Frederick III, the ruler of the Palatinate, (a region in southwest Germany) converted to Calvinism in 1559. What further complicated the situation was that as the ruler of the Palatinate, Frederick was one of the seven electors of the Holy Roman Emperor.

Within the next two decades, several other German princes followed Frederick’s lead and aggressively challenged the religious status quo achieved by the Peace of Augsburg. The tremendous success of the Catholic Counter-Reformation in Southern Germany further stoked religious tensions in Germany.

In areas such as Bavaria, all traces of Protestantism were stamped out as Jesuits were invited to take charge of Bavarian schools and universities. Although Charles V failed in his attempt to create a unified German state, the dream would continue. The Thirty Years’ War (1618–1648), a struggle that combined political and religious issues, marked one final attempt within the Holy Roman Empire to make that dream a reality.

The Thirty Years’ War (1618–1648)

The Thirty Years’ War began in Bohemia (the modern-day Czech Republic), where in 1617 Ferdinand of Styria, an avid Catholic, was crowned King of Bohemia. The majority of Bohemians were Protestant, and they were angered with their new King Ferdinand’s intolerance toward their religious beliefs. In May of 1618, a large group of Bohemian Protestant nobles surrounded two of Ferdinand’s Catholic advisors and threw them out of a window (the second Defenestration of Prague). They survived by landing in a dung heap. The next year, Matthias, the Holy Roman Emperor, passed away, and his cousin Ferdinand, the King of Bohemia, was elected Emperor in his stead. A few hours after being elected, Ferdinand learned to his horror that rebels in Bohemia had deposed him and elected Frederick, the Calvinist Elector of the Palatinate, as their king. Since he did not have an army, Ferdinand had to turn to the Duke of Bavaria, who agreed to lend his support in exchange for the electoral right enjoyed by the Palatinate. At the Battle of White Mountain, the Bavarian forces won a major victory, and Frederick became known as the Winter King since he held onto the Bohemian throne for only that season. By 1622, he had lost not only Bohemia but also the Palatinate.

The question now arises as to why the Thirty Years’ War didn’t end in 1622 (and force historians to give it a different name). Part of the problem was that there were still private armies throughout the Empire that wanted to fight to keep earning a living. The perceived threat to Protestants in Germany drew outsiders, such as the King of Denmark, into the fight. Additionally, both Catholic and Protestant rulers were concerned that the traditional constitution of the Holy Roman Empire had been dramatically altered when the Palatinate’s electoral vote was given to Bavaria. Taking away this vote from the Palatinate was deemed an attack on what contemporaries called “German liberties,” by which they meant the independence and political rights enjoyed by territories within the Holy Roman Empire.

This issue of liberties also came to the foreground when Emperor Ferdinand confiscated defeated Protestant princes’ land in the north and created the genuine opportunity to forge a unified state under Habsburg control. Given this opportunity, Ferdinand first had to find a new army, since he could no longer rely on the Duke of Bavaria, who began to fear Habsburg domination. He turned to a Bohemian noble by the name of Albrecht von Wallenstein for this second phase of the war, who promised to create a vast mercenary army. By 1628, Wallenstein controlled an army of 125,000 and had won a series of major victories in the north.

The high-water mark for Habsburg success in the Thirty Years’ War came with the Edict of Restitution of 1629. The edict outlawed Calvinism in the empire and required Lutherans to turn over all property seized since 1552—16 bishoprics, 28 cities and towns, and 155 monasteries and convents. This led the King of Sweden, Gustavus Adolphus, to enter the war, triggering a third phase. Although he claimed that he became involved to defend Protestant rights in Germany, Adolphus was also interested in German territory along the Baltic. To make matters even more confusing, the French government financially supported the Swedish army, because France’s chief minister, Cardinal Richelieu, was concerned about the increase of Habsburg strength in Germany. Clearly this skirmish had ignited far beyond a religious war.

The Swedes rolled back the Habsburgs until 1632, when Adolphus died in battle. The next year, Wallenstein was murdered on orders of the emperor, since Ferdinand began to fear that his general was negotiating with his opponents. The final phase of the war consisted of the French and Swedes fighting against the Austrian Habsburgs and their Spanish allies. This was the most destructive phase of the war; German towns were decimated, and a general agricultural collapse and famine ensued. By the end of the war in 1648, the Empire had eight million fewer inhabitants than it had in 1618.

The Peace of Westphalia (1648) marked the end of the struggle. Thirty years of war had brought about very little. The Holy Roman Empire maintained its numerous political divisions, and the treaty ensured that the Emperor would remain an ineffectual force within German politics. The treaty also reaffirmed the Augsburg formula of each prince deciding the religion of his own territory, although the new formula now fully recognized Calvinism.

FRANCE

By the end of the reign of the powerful Francis I, it appeared as if the struggle between the feudal aristocracy and the monarchy had been settled in favor of the newly powerful centralized monarchy. However, the French Wars of Religion (1562–1598) revealed that the struggle was not quite over. Although ostensibly concerned with religious ideas, this series of civil wars was part of a long tradition, dating back to the very roots of French history, in which the aristocracy and monarchy battled one another for supremacy.