Chapter 5

Monarchical States to Napoleon: c. 1648–c. 1815

FRANCE

Royal Absolutism

Until his assassination in 1610, Henry IV worked to revitalize his kingdom. With his finance minister, the Duke of Sully, Henry established government monopolies over a number of key commodities (such as salt) to restore the finances of the monarchy. He also limited the power of the French nobility by reining in its influence over regional parliaments. Despite this strengthening of monarchical power, Henry’s assassination in 1610 and the ensuing ascension of his nine-year-old son, Louis XIII, made France once again vulnerable to aristocratic rebellion and the potential of religious wars. Louis needed a strong minister, and he found one in Cardinal Richelieu. Richelieu defeated the Huguenots and took away many of the military and political privileges granted them by the Edict of Nantes. He brought France into the Thirty Years’ War, not as the defender of Catholic interests, but on the side of the Protestants in order to counter the traditional French enemy, the Spanish Habsburgs.

The death of Louis XIII in 1643 once again left France with a minor on the throne; the five-year-old Louis XIV was unable to benefit from Richelieu’s guidance because the great minister had predeceased Louis XIII by one year. Louis XIV’s mother, Ann of Austria, selected Cardinal Mazarin to be the regent during the King’s childhood. Mazarin had a less sure political hand than Richelieu, and once again, France had to grapple with a series of rebellions known as the Fronde in the period between 1649 and 1652. These events scarred the young Louis XIV, who at one point during the rebellion had to flee from Paris. Following the death of Mazarin in 1661, Louis decided to rule without a chief minister and to finally grapple with the central issue that had dominated France for more than a hundred years—how to deal with an aristocracy that resented the ever-increasing powers of the French monarchy.

One way that Louis achieved this goal was to advocate a political philosophy that had been developing in France since the sixteenth century—the notion that the monarch enjoyed certain divine rights. Using Old Testament examples of divinely appointed monarchs, Louis’s chief political philosopher, Bishop Bossuet, wrote that since the king was chosen by God, only God was fit to judge the behavior of the king, not parliamentary bodies or angry nobles.

Louis built the palace of Versailles twelve miles outside of Paris as another way to dominate the French nobility and the Parisian mob. Although his grandfather had converted to Catholicism to appease the people of Paris, Louis felt he could safely ignore the people from the confines of his palace. Eventually, 10,000 noblemen and officials lived at Versailles, a palace so immense that its facade was a third of a mile long, with grounds boasting 1,400 fountains. While it cost a huge amount of money to maintain Versailles, Louis thought it was worth it. Instead of plotting against the King, the aristocrats were distracted by court intrigue and gossip and by ceremonial issues such as who got to hold the King’s sleeve as he got dressed. Those members of the aristocracy who did not live at Versailles were pleased with their tax exemptions as well as their high social standing.

To administer his monarchy, Louis made use of the upper bourgeoisie. No member of the high aristocracy attended the daily council sessions at Versailles. Instead, his most important minister was Jean-Baptiste Colbert, the son of a draper. Colbert centralized the French economy by instituting a system known as mercantilism. The central goal of mercantilism was to build up the nation’s supply of gold by exporting goods to other lands and earning gold from their sale. To do this, Colbert organized factories to produce porcelains and other luxury items. He also tried to abolish internal tariffs, ultimately creating the Five Great Farms, which were large, custom-free regions.

Part of mercantilism was a reliance on foreign colonies to buy the mother country’s exports. To that end, Colbert succeeded in helping to create France’s vast overseas empire. By the 1680s, Louis controlled trading posts in India, slave-trading centers on the west coast of Africa, and several islands in the Caribbean, while the largest colonial possession was New France, the territory we know today as Quebec. Colbert particularly wanted to strike at the rich commercial empire of the Dutch, so he organized the French East India Company to compete with the Dutch. It enjoyed only limited success as a result in part of excessive government control and a lack of interest in such ventures by the French elite.

Louis XIV touted religious unity in France as a means of enhancing royal absolutism. While during the reign of his father the rights of Huguenots had declined due to the hostility of Richelieu, the Edict of Nantes was still in effect. Louis decided that the time had come to eradicate Calvinism in France. In 1685, he revoked the Edict of Nantes, a fateful decision that would greatly weaken the French state. He demolished Huguenot churches and schools and took away their civil rights. Some remained underground, but as many as 200,000 were exiled to England and the Netherlands. The Huguenots were an important part of the French economy; by fleeing to enemy lands, they aided the two countries that were at war with Louis. For Louis, however, such economic considerations meant little in comparison to what he thought was the more important goal and the one most pleasing to God—the elimination of religious heresy from France.

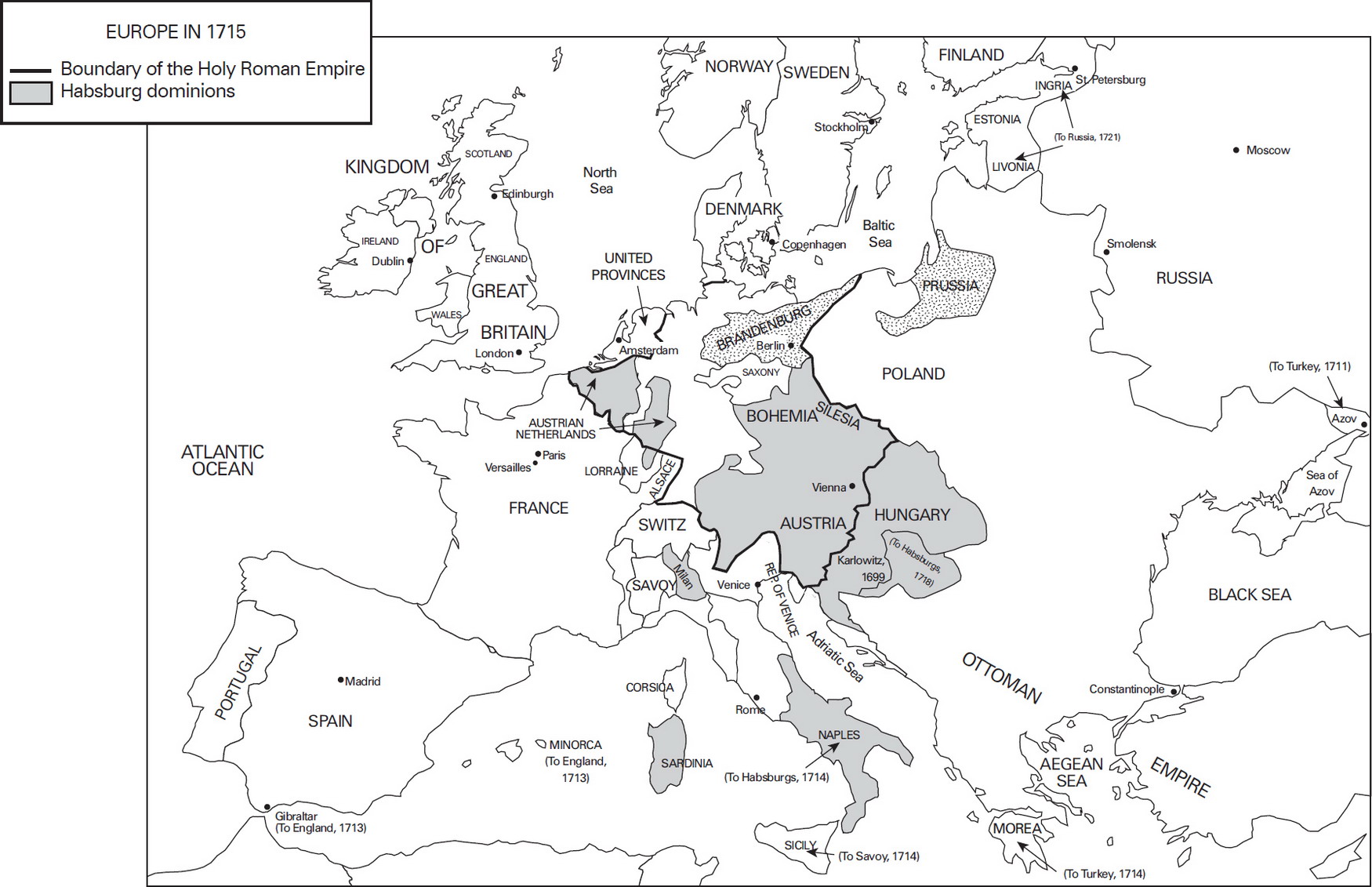

During the reign of Louis XIV, France was involved in a series of wars as a means to satiate Louis’s desire for territorial expansion. In the early part of his reign, this policy was quite successful, as France conquered territories in Germany and Flanders. This success lasted until 1688, when the English—in a move that marked the Glorious Revolution—replaced James II, the king who had received subsidies from the French, with a new monarch, William of Orange, who as leader of the Netherlands was committed to waging total war against Louis. After 1688, another series of wars erupted that lasted for twenty-five years, including the War of Spanish Succession between the French and the English and Dutch allies, which lasted from 1702 to 1713 and concluded with the Treaty of Utrecht, which left a Bourbon (Louis’s grandson) on the throne of Spain but forbade the same monarch from ruling both Spain and France. These wars ultimately resulted in the containment of Louis XIV’s France but left the French peasantry hard pressed to pay the taxes to support Louis’s constant desire for glory.

ENGLAND

The Stuarts

When Elizabeth died childless in 1603, as promised, her cousin King James VI of Scotland inherited the throne. To a certain extent, James was ill suited for the role of English king. The Scottish Parliament was a weak institution that did not inhibit the power of the monarch. James’s interest lay in asserting his divine notion of kingship, which he had been exposed to by reading French writings on the subject. He told the English Parliament the following during the first session with them:

The state of monarchy is the supremest thing upon Earth: for Kings are not only God’s lieutenants upon Earth and sit upon God’s throne, but even by God Himself they are called gods. As to dispute what God may do is blasphemy, so it is sedition in subjects to dispute what a King may do in height of his power. I will not be content that my power be disputed on.

Such words could not have pleased his audience. In the relationship between the king and Parliament at the start of the seventeenth century, the monarch held the upper hand—only the king could summon a parliament, and he could dismiss it at will. James did, however, have to consult the two-house English Parliament, the House of Commons and the House of Lords, when he needed to raise additional revenue beyond his ordinary expenses. This parliamentary control over the financial purse strings in an age when the cost of governing was dramatically increasing played a crucial role in Parliament’s eventual triumph over royal absolutism.

Religious issues further complicated James’s reign (he was always suspected of being a closet Catholic). The religious settlement worked out by Elizabeth in 1559 was no longer adequate in an age in which English religious passions grew increasingly intense. It failed to satisfy the radical Calvinist Protestants, known as Puritans, who emerged during the Stuart period. In 1603, most Puritans still belonged to the Church of England, although they were a minority within the Church. For the most part, what distinguished the Puritans was that they wanted to see the Church “purified” of all traces of Catholicism. Although raised in Calvinist Scotland, James, on his arrival in England, found the Church of England with its hierarchical clergy and ornate rituals more to his taste. He believed its Episcopal structure was particularly well suited to his idea of the divine right of kings. In 1604, when a group of Puritans petitioned the new king to reform the Church of England, James met them with the declaration: “I will have one doctrine, one discipline, one religion, both in substance and in ceremony.” He added words that would prove to be rather prophetic for his son: “No Bishop, No King,” meaning that by weakening the Church, the monarchy in turn weakens. James’s opposition to the Puritan proposal drove the more moderate of the Puritans—individuals who just wanted to rid the Church of England of its last traces of Catholic ritual—onto a more extreme track. Some Puritans even decided to leave England; one such group founded the colony of Plymouth, Massachusetts, in 1620.

James’s three-part program—to unite England with Scotland, to create a continental-style standing army, and to set up a new system of royal finance—met with little support from Parliament. James’s son, Charles I (r. 1625–1641), did not possess even the somewhat limited political acumen of his father. Like his father, Charles felt that the Anglican Church provided the greatest stability for his state, and he further enflamed passions by lending his support to the so-called Arminian wing of the Anglican Church. Arminius was a Dutch theologian of the early seventeenth century who argued in favor of free will as opposed to the Calvinist doctrine of predestination. In 1633, Charles named William Laud, a follower of this doctrine, his Archbishop of Canterbury. The Arminians, although certainly not pro-Catholic, refused to deny that Catholics were Christians; this philosophy greatly angered the Puritans. The Arminians further antagonized Puritan sentiment by advocating a more ornate church service.

The relationship between Charles and Parliament got off to a bad start when Parliament granted him Tonnage and Poundage (custom duties) for a one-year period rather than for the life of the monarch, as had been the custom since the fifteenth century. Charles, however, was committed to the war against Spain, so he cashed in his wife’s dowry and sent an expedition to the Spanish port of Cadiz; the mission was a complete failure. To pay for these military disasters, Charles requested a forced loan from his wealthier subjects. Several Members of Parliament refused to pay this loan and were thrown in jail. Parliament was called in again in 1628, at which time it put forward a Petition of Rights, which Charles felt forced to sign. It included provisions that the king could not demand a loan without the consent of Parliament and that Parliament must be called frequently. The petition also prohibited individuals from being imprisoned without published cause and the government from housing soldiers and sailors in private homes without the owner’s permission. Finally, it outlawed using martial law against civilians, which Charles had used to collect his forced loan.

In August 1628, Charles’s chief minister, the dashing but incompetent Duke of Buckingham, was murdered by an embittered sailor who blamed him for England’s recent military disasters. Charles, on the other hand, blamed the leaders of the House of Commons, most notably John Eliot, for inflaming passions against Buckingham. When Parliament was again called in January 1629, both sides felt that the issue of exclusive rights would lead to a conflict between Parliament and the King. In March 1629, the issue came to the foreground when Eliot proposed three resolutions.

1. High churchmen and anyone suspected of popery (practicing Catholicism) should be branded as capital enemies of the state.

2. Any of the King’s advisors who recommended that he raise funds without Parliament’s approval should be tried as capital enemies of the state.

3. Anyone who paid tonnage and poundage, which the King was still illegally collecting, would be betraying the “liberties of England.”

After hearing these demands, which he thought outrageous, the King summoned the Speaker of the House of Commons and ordered him to dissolve Parliament. Two Members of Parliament held the Speaker in his chair, a treasonable act because it disputes the right of the king to dissolve Parliament. Once Eliot’s resolutions were passed, the King’s messengers announced that he had dissolved Parliament.

For the next eleven years, what is known as the Personal Rule of Charles was the law of the land. Charles decided to govern England without calling a Parliament. Charles could have carried this off successfully and brought about the end of Parliament, as occurred in France during the same period of time. The major problem of how to raise enough revenue was solved by extending the collection of ship money throughout the kingdom, a politically explosive decision. Traditionally, certain coastal cities were responsible for raising funds for naval defense during times of national emergency. In 1634, Charles declared an emergency (although England was at peace), and two years later he extended this tax to inland cities and counties, areas that had never before paid ship money. This was such a substantial source of income that it could possibly have freed the King from ever having to call a Parliament.

The Case of John Hampden

The collection of ship money led to a famous legal case involving John Hampden, a Puritan Member of Parliament, who, having already challenged the legality of the forced loan, now questioned Charles’s raising of ship money. While the judges found against Hampden by a vote of seven to five, he was viewed as having achieved a moral victory.

By 1637, Charles was at the height of his power. He had a balanced budget, and his government policies and restructuring appeared to be effective. Yet within four years of this peak, the country would be embroiled in a civil war. Charles ultimately ruined his powerful position by insisting that Calvinist Scotland adopt not only the Episcopal structure of the Church of England, but also follow a prayer book based on the English Book of Common Prayer. The Scots rioted and signed a national covenant that pledged their allegiance to the King but also vowed to resist all changes to their Church.

In 1640, Charles called an English Parliament for the first time in eleven years, because he believed it would be willing to grant money to put down the Scottish rebellion. This became known as the Short Parliament because it met for only three weeks and was dissolved after it refused to grant funds prior to Charles addressing their own grievances. Charles was still determined to punish the Scots; after he dissolved Parliament, he patched together an army with the resources he could muster. The Scots were the victors on the battlefield and invaded northern England. They refused to leave England until Charles signed a settlement and, in the meantime, forced him to pay £850 per day for their support.

To pay this large sum, Charles was forced to call another Parliament. This became known as the Long Parliament, since it met for an unprecedented 20 years. The House of Commons launched the Long Parliament by impeaching Charles’s two chief ministers, the Earl of Strafford and Archbishop Laud (Strafford was executed in 1641 and Laud in 1645). Parliament abolished the king’s prerogative courts, like Henry VIII’s Court of Star Chamber, which had become tools of royal absolutism. Tensions grew even higher when a rebellion broke out in Ireland, which had been ruled with a strong hand since the time of the Tudors.

Parliament took the momentous step of limiting some of the king’s prerogative rights. They supported what was known as the Grand Remonstrance, a list of 204 parliamentary grievances from the past decade. They also made two additional demands: that the king name ministers whom Parliament could trust and that a synod of the Church of England be called to reform the Church of England. In response Charles tried to seize five of the leaders of the House of Commons, an attempt that failed, resulting in Charles leaving London in January 1642 to raise his royal standard at Nottingham. This marked the beginning of the English Revolution.

The English Revolution

During the initial stage of the English Revolution, things went poorly for Parliament. Their military commander, the Earl of Manchester, pointed out the dilemma when he noted: “If we beat the King 99 times, he is still the King, but if the King defeats us, we shall be hanged and our property confiscated.” Individuals, such as Oliver Cromwell, who were far more dedicated to creating a winning war policy, soon replaced the early aristocratic leaders. It was Cromwell who created what became known as the New Model Army, a regularly paid, disciplined force with extremely dedicated Puritan soldiers. By 1648, the King was defeated, and in the following year, Cromwell made the momentous decision to execute the King, a move that horrified most of the nation.

From 1649 to 1660 England was officially a republic, known as The Commonwealth, but essentially it was a military dictatorship governed by Cromwell. Cromwell had to deal with conflicts among his own supporters, such as the clash between the Independents and the Presbyterians. The Independents, who counted Cromwell among their ranks, wanted a state church, but were also willing to grant a measure of religious freedom for others (although Catholics were to be excluded from this tolerant policy). On the other side of the divide were the Presbyterians, who wanted a state church that would not allow dissent. Cromwell also had to deal with the rise of radical factions within his army, groups like the Levellers and Diggers, who combined their radical religious beliefs with a call for a complete overhaul of English society. They touted a philosophy that included such radical ideas as allowing all men, not just those who owned land, to vote for members of the House of Commons.

Cromwell destroyed the Leveller elements in his army in 1649 after several regiments with large Leveller contingents revolted against his rule. In the following year, Cromwell led an army to Ireland, where he displayed incredible brutality in putting down resistance by supporters of the Stuarts.

Cromwell would find, as Charles I had earlier, that Parliament was a difficult institution to control. In 1652, he brought his army into London to disperse a Parliament that dared to challenge him only to replace them with hand-selected individuals who still earned his displeasure within a matter of months. Over the next year, a group of army officers wrote the “Instrument of Government,” the only written constitution in English history and a document that provided for republican government (the Protectorate) with a head of state holding the title Lord Protector and a parliament based on a fairly wide male suffrage. Cromwell stepped into the position of Lord Protector, but still found Parliament difficult to control. Finally in 1655, Cromwell gave up all hope of ruling in conjunction with a legislature, and divided England into 12 military districts, each to be governed by a major general.

By the time Cromwell died, an exhausted England wanted to bring back the Stuart dynasty. In 1660, the eldest son of the executed monarch became Charles II. The return of the Stuarts turned back the clock to 1642 as the same issues that had led to the revolution against Charles’s father remained unresolved: What is the proper relationship between king and Parliament? What should be the religious direction of the Church of England? These issues were not fully addressed during Charles’s reign although they came to the forefront during the reign of his younger brother, James II, who succeeded Charles on the throne in 1685.

Suspected of being a Catholic like all previous Stuarts, James immediately antagonized Parliament by demanding the repeal of the Test Act, an act passed during Charles II’s reign that effectively barred Catholics from serving as royal officials or in the military (there was no law at this time barring Catholics from the monarchy). James also issued a Declaration of Indulgence, which suspended all religious tests for office holders and allowed for freedom of worship. On the surface, James appeared to have been a champion of religious freedom; this was deceptive. What James really wished to achieve in England was royal absolutism; however, the steps that he took to achieve this goal were illegal. The final stages of this conflict took place in 1688. Early in the year, James imprisoned seven Anglican bishops for refusing to read James’s suspension of the laws against Catholics from their church pulpits, the usual way of informing the community of royal edicts in an age before modern communications. James also unexpectedly fathered a child in June 1688 and now had a male heir who would be raised as a Catholic, in contrast to his previous heir, his daughter Mary, who was a Protestant. These moves to create a Catholic England created unity among previously contentious Protestant factions within England. One faction of this political and religious elite invited William, the Stadholder of the Netherlands and the husband of Mary, to invade England. When his troops landed, James’s forces collapsed in what was basically a bloodless struggle (except for in Ireland, where there was tremendous violence over the next several years), known as the “Glorious Revolution.” James was overthrown, and William and Mary jointly took the throne.

What followed was a constitutional settlement that finally attempted to address the pervasive issues of this century of revolution.

The settlement consisted of the following acts:

• The Bill of Rights (1689) forbade the use of royal prerogative rights as Charles and James had exercised in the past. The power to suspend and dispense with laws was declared illegal. Armies could not be raised without parliamentary consent. Elections to Parliament were to be free of royal interference. The monarchs also had to swear to uphold the Protestant faith, and it was declared that the monarchy could not pass into the hands of a Catholic. Most importantly, Parliament’s approval was now officially required for all taxation.

• The Act of Toleration (1689) was in many ways a compromise bill. To get nonconformists’ (Protestants who were not members of the Church of England) support in the crucial months of 1688, Whigs and Tories (Whigs being the more liberal parliamentary faction than the Tories) had promised them that an act of toleration would be granted when William became king. The nonconformists could have achieved liberty of worship from James II’s act of toleration, but an act from a popular Protestant monarch would prove to be a better safeguard to their liberties. The Act of Toleration granted the right of public worship to Protestant nonconformists but did not extend it to Unitarians or to Catholics (those two groups were also left alone, although legally they had no right to assemble to pray). The Test Act remained, which meant nonconformists, Jews, and Catholics could not sit in Parliament, until the law was changed in the nineteenth century.

• The Mutiny Act (1689) authorized the use of civil law to govern the army, which previously had been governed only by royal decree. It also made desertion and mutiny civil crimes, for which soliders could be punished during peacetime. But the act was only in effect on a year-by-year basis, which meant that a Parliament had to be summoned annually if for no other reason than to pass this act. Along with the Bill of Rights’ provision against standing armies in peacetime, the Mutiny Act brought the army under effective parliamentary control.

• The Act of Settlement (1701) was passed to prevent the Catholic Stuart line from occupying the English throne. In 1714, when Queen Anne, the second Protestant daughter of James II, died childless, the throne passed to George I, the Elector of Hanover, a Protestant prince and a distant kinsman of the Stuarts.

• The Act of Union (1707) marked the political reunification of England and Scotland, forming the entity known as Great Britain. This union was by no means a love match and, in fact, primarily occurred because relations between the two previously independent states were so bad that on his deathbed, William III urged that union take place to forestall Scotland from going to war with England as an ally of France. As part of the agreement, Scotland gave up its parliament but was allowed to maintain the state-sponsored Presbyterian Church and its Roman-based legal system.

THE NETHERLANDS

A Center of Commerce and Trade

The relative decline of Spain as an economic power was in part due to the growing competition from the Netherlands. The Netherlands had already achieved a central role in inter-European trade due to its geographic position and large merchant marine fleet. For example, it was the Netherlands that provided a connection between the raw material producers in the Baltic region and the rest of Europe. Beyond Europe, control over the lucrative spice trade in Asia was wrested out of the hands of the Portuguese, a situation which was made worse when Spain took control over Portugal in 1580 and found itself without the resources to rival the Dutch in Asia.

Increasingly, it was the city of Amsterdam (the capital of the Netherlands), rather than the Spanish-controlled city of Antwerp, that became the center of commerce in northern Europe. The sacking of the city of Antwerp in 1576 during the Dutch War for Independence and the permanent closing of the Scheldt River that led to its harbor, as part of the Peace of Westphalia, also aided in the decline of Antwerp and its replacement as an economic center by Amsterdam.

Dutch dominance in part came from technological achievements such as the development of less expensive but ocean-worthy cargo ships, but the Dutch also proved to be creative in their establishment of financial and commercial institutions. The Bank of Amsterdam, founded in the early part of the seventeenth century, issued its own currency and increased the amount of available capital, while also making Amsterdam the banking center of Europe. In 1602, the Dutch East India Company was established. The company operated under quasi-governmental control and was funded by both public and private investment. This kind of investment, used in the past but most successfully in the Netherlands, gave rise to the popularity of joint-stock companies. Such companies allowed risks and profits to be shared among many individuals. The large capitalization behind the Dutch East India Company allowed for the purchasing of more ships and warehouses. The Dutch also proved to be very nimble businessmen, so that when the prices of spices decreased due to oversupply, they quickly turned to other commodities such as coffee, tea, and fabrics, although by the beginning of the eighteenth century, Dutch commercial power, although continuing down to this day, would lose its preeminent place in Europe to the English.

This “Golden Age” in the Netherlands produced a high standard of living, with wealth being more equally distributed than any other place in Europe. The Netherlands also stood out from the rest of Europe for its tolerant attitude toward religious minorities, with Jews fleeing from the Spanish Inquisition and Anabaptists as well as Catholics finding a place among the majority Calvinist population.

Political Decentralization

Dutch exceptionalism also extended to the political realm because politically, the Netherlands didn’t look like any other state in Europe. For most of the seventeenth century, it was politically decentralized, with each of the seven provinces retaining extensive autonomy. Wealthy merchants dominated the provincial Estates, which retained powers far more extensive than those of national Estates General, particularly in the area of taxation. Executive power, such as it was, came from the noble House of Orange, whose family members had achieved prominence for leading the revolt against Spain. The male head of this family held the title of stadholder, an office with primarily a military function, no mere formality as the Netherlands switched from fighting for its independence from Spain to economic wars against the English and a long-term struggle for survival against France. During the struggle with Louis XIV’s France, the power of the provincial Estates went into decline, while the authority of William of Nassau, the head of the House of Orange, increased tremendously, particularly when William became King of England after the Revolution of 1688.

A Golden Age of Art

Culturally, the seventeenth century proved to be a golden age as well. Dutch artists, reflecting the fact that the majority of the population was Calvinist, didn’t receive large commissions to be placed in churches, although the Baroque style of painting penetrated the Netherlands through Catholic Flanders. Instead, Dutch artists painted for private collectors, who supported an incredibly large number of painters and a wide range of styles, including the production of a large number of landscapes. Like so much else in the Netherlands, pictures were treated as commodities, with prices at times reaching speculative rates.

The art market didn’t just flourish in Amsterdam, as shown by the thriving career of Franz Hals (c. 1580–1666), the great portrait painter from Haarlem. Another gifted Dutch painter, Jan Vermeer (1632–1675), had initially thought of being a painter of historical scenes, but when he received no commissions, he turned to the carefully composed genre scenes of everyday Dutch life, for which he has become justifiably famous. The greatest genius of the Dutch golden age was Rembrandt Van Rijn (1606–1669), whose paintings, which were initially influenced by the High Baroque style and were later in his career more subtly painted, are fraught with a deep emotional complexity. One of his masterpieces, The Night Watch (1642), transforms a standard group portrait of a military company into a revealing psychological study.

ECONOMIC AND SOCIAL LIFE IN EARLY MODERN EUROPE

It’s a little difficult to generalize about life in early modern Europe because conditions varied from region to region, but general trends do emerge for the period.

Economic Expansion and Population Growth

By the end of the fifteenth century, Europe was ushering in an age of economic expansion that sharply contrasted with the decline that had taken root in the fourteenth century with its disastrous famines and plagues. The key development in the period was the growth in population. To use France as a typical example, the population doubled from 10 million to 20 million from 1450 to 1550. This significant population expansion was very important for economic productivity, in an age in which manpower was still far more important than labor-saving technology. The expansion of Europe’s population also provided for additional consumers, which meant that there was greater incentive to bring more food and other essentials to market.

The growth of population also had an impact on another important development: the significant increase in prices in the early modern period, which has become known as the Price Revolution. Initially, historians thought that this increase came from the influx of precious metals from the New World and the debasement of their coinage by money-hungry monarchs, but it is now apparent that it was population growth that put pressure on the prices of basic commodities such as wheat. This inflation did not increase at a rate that would impress a modern consumer, with grain prices increasing 500 percent—which sounds much more impressive until you take into account that this increase took place in the 150-year period from 1500 to 1650. Nevertheless, for a society that was accustomed to stable prices, a price increase of this magnitude came as a shock. Historians have even tried to find ways of connecting the Price Revolution to the political and religious struggles of the age, based on the theory that periods of high inflation can be an important factor behind the development of social tensions.

Rural Life and the Emergence of Economic Classes

One way in which rural life was transformed in this period, in part due to the Price Revolution, was the emergence of a class of wealthy individuals, located socially below the aristocracy, who began to buy significant amounts of newly valuable landholdings. In England, this class of individuals, who often had their economic roots in fortunes made in towns and cities, were known as the gentry, and would play a major role in the political struggles that the English Parliament would wage against the monarchy in the seventeenth century. The land-buying habits of the gentry forced up the price of land. In addition, the gentry were able to use their social connections to get local authorities to accept the enclosure of lands for their own personal use, land that had previously been available for the grazing of animals by the entire community.

The problem of rural poverty became significantly worse in the early modern period, with many small farmers reduced to the role of beggars, spending their days tramping from one locale to another. Increasingly, the problem of poverty weighed on the political elite; in Catholic lands, the Church remained the major provider of social services, while in Protestant countries it became the task of the state to provide for the destitute, such as the first English Poor Law during the reign of Queen Elizabeth. Although rural overpopulation was a problem throughout most of western Europe, in eastern Europe, low population density was a much more serious problem, leading wealthy landowners to solve their labor shortages by binding the formerly free peasantry to the land in a process of enserfment.

Farm Life

For the majority of individuals in Europe, who lived in rural areas as small-scale farmers, life was fairly dismal and revolved around a constant struggle to find the resources to survive. Life centered on the small village, often with fewer than fifty households, with most people never traveling a few miles beyond the location of their birth. Housing in rural villages offered little protection from the cold and wet winters. Homes were generally made of wood, with packed mud on the walls and straw on the floor, lacking windows and adequate ventilation. For the most part, they consisted of one main room that possessed a stone hearth that provided heat. The possessions that went into these houses were as simple as their surroundings. The worldly possessions of most rural households could fit in a single chest, which could double as a table and could be carried away by the family in case they had to flee during an emergency, such as the arrival of mercenaries looking for plunder.

The workdays were long during the summer harvests, and shorter in the winter, with late winter offering the rural household the terrifying prospect of not having enough resources to tide them over until the coming of spring. Although farming began to change by the end of the seventeenth century in the Netherlands and in England with the beginnings of what we may refer to as scientific methods, for the most part, Europeans were farming in 1800 the same way they had farmed going back to the High Middle Ages (c. 1001–1300). The three-field system (where crops were rotated across three pieces of land) was used in the north of Europe, while the two-field system (crops rotated on two pieces of land) predominated in the Mediterranean region. Farmland in most rural areas was set out in long strips, with individual peasant families owning a portion of land in each of the strips. Because animals such as cows or sheep needed copious amounts of food, common lands in each village were shared, although the wealthy rural elite was increasingly coveting this common land. Most of what was grown was used by the farmers for their own households, leaving very little to be brought to market. The diet of the average European peasant farmer was incredibly monotonous, with most calories coming from grain in various forms, ranging from dark bread to gruels and beer.

Life in the Cities and Towns

Although towns and cities held scarcely more than 10 percent of the overall population, they provided for some variation from what Karl Marx would call “the idiocy of rural life.” Townspeople in general lived better than their rural counterparts, with better housing and a more varied diet, although urban poverty was also increasing in this period.

There was also a much greater variety of occupations, with a much greater emphasis on specialization, with specific tasks such as baking or brewing taking place in specific quarters of the town. Guilds, which began to dominate the urban economy during the High Middle Ages, continued to play a role in the production of commodities down to the time of the French Revolution.

However, the guild method of production was being supplanted by a new means of production that was in part directed by the expansion of population and the growth of markets. Cloth was now produced on a much larger scale by a new group of capitalist entrepreneurs and required a large outlay of money to get started. These individuals would provide the money and the organizational skills, which they used to direct every stage of the production of broadcloth, beginning with the cleaning of the wool and ending with the weaving. This work provided a benefit in some rural households (where the various stages of production would now take place), adding an important source of revenue particularly during the long winter months.

For guild members, however, this new competition created great hardships. Also, for apprentices and journeymen the dream of becoming a full-fledged guild master was becoming an increasingly rare occurence. These men essentially became wage earners with little hope of rising up the economic and social ranks. Dissatisfied journeymen and apprentices would play an important role in the urban revolts of the period.

Family Life and Structure

Although we tend to assume that some notion of the extended family existed in the past, with several generations living under one roof, the family in the Early Modern period would not look significantly different from today’s nuclear family. Family size was smaller than what one might have imagined for the period, with the average family consisting of no more than three or four children. The relatively small number of children was partly the result of fewer childbearing years resulting from later marriages, with women on average marrying around age 25 and men two years later. Traditionally, marriages were either arranged by the parents or at least formally approved, in part because even in the poorest of rural communities, marriage involved some transfer of property. Weddings were important community events, because the married husband and wife were now considered to be full-fledged members of society, and in general, single adults were looked on as potential thieves or troublemakers if they were male and as prostitutes if they were female.

The Role of Men in the Family

In many ways, the family with the father as the patriarchal head served as a reflection in miniature of the larger hierarchical ordering of early modern society. In wealthier families, the father had to ensure that the family’s wealth remained intact, which meant that the oldest male child inherited most of the estate (primogeniture), with younger sons being guided toward careers in the Church, military, or in the increased opportunities offered by the burgeoning administration of the early modern state.

The Role of Women

The only claim that daughters would have on the parental estate would come with the dowry that they would receive upon marriage. Wives could usually determine who should receive their dowry upon their death, although during their own lifetimes their husbands would manage the dowry. Among the poor, arrangements would be different, with boys apprenticed off to a trade or as servants at the age of seven, and domestic service being the only opportunities for girls, who in the poorest of families were left with the difficult task of trying to raise their own dowries.

The Family as Economic Unit

Early modern families, whether rich or poor, can be seen as economic units. Before the late Industrial Revolution, child labor was accepted and commonplace. To some extent, jobs were gendered: Men played a larger role in the “public” sphere, such as plowing, planting, and commerce, while women had responsibility over the home. However, in agricultural communities, everyone was expected to work in the fields; and among merchant classes, the “private” sphere might include bookkeeping and other administration of the family business while the men went on purchasing tours. In some cases, the main difference between women’s work and men’s work was that women’s work included all the men’s work, plus taking care of the house and the cooking. The strongest division between men’s and women’s roles was in the upper classes and the nobility. Only these very wealthy people could afford the luxury of an idle woman. This, combined with better diet, wet-nursing, and more sanitary conditions, was why wealthier families might see annual pregnancies (as opposed to every two or three years for poorer women), as well as why the wealthy had a much lower childhood mortality rate.

How the Protestant Reformation Changed Family Life

Although one can scarcely talk about a revolution taking place in family life in this period, the Protestant Reformation did usher in some changes. In Protestant lands, the household became the center of Christian life, rather than the church or monastery. Arguably, paternalism increased, as the father now assumed a spiritual role as the chief intermediary between the family and God, while also more strictly enforcing moral standards and the value of hard work. For women who wanted to avoid marriage and constant childrearing, the option of convent life came to an end, and frugal fathers lost the opportunity to save dowry money. In some places, divorce was allowed, something that was anathema to the Catholic Church.

Women in Protestant lands were conceivably freer in the sense that they were able, like any man, to directly communicate with God without relying on a male priest as an intermediary. However, those women who wanted to take a more active role by leading congregations and preaching—as seen in some of the more radical Protestant sects such as the Anabaptists—were brutally persecuted.

EVENTS LEADING TO THE SCIENTIFIC REVOLUTION

In 1611, the English poet John Donne wrote An Anatomy of the World, in which he reflected on the multitude of ways that his world had changed as a result of the new discoveries in science.

New philosophy calls all in doubt

The element of fire is quite put out;

The sun is lost, and th’ Earth, and no man’s wit

Can well direct him where to looke for it.

And freely men confesse that this world’s spent,

When in the Planets, and the new firmament

They seeke so many new; then see that this

Is crumbled out againe to his Atomies

'Tis all in peeces, all coherance gone;

All just supply, and all Relation.

As Donne understood, the scientific discoveries of the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries brought about a fundamental change in the way Europeans viewed the natural world. To call this change a revolution may be misleading in light of the length of time over which it occurred, but the implications from these discoveries were truly revolutionary. Not only did it change the way Europeans viewed the world around them, but it also had significant implications in such areas as religion, political thought, and how they fought wars.

Why was it that seventeenth-century thinkers challenged the medieval view of the natural world? What possibly occurred in that age that led them to question ideas that previously had been readily accepted? The following are some possibilities.

Discovery of the New World

The period of exploration and conquest led to the discovery of new plant and animal life and possibly encouraged greater interest in the natural sciences. Also, the traditional link between navigation and astronomy and the great advances made by Portuguese navigators in the fifteenth century helped fuel an interest in learning more about the stars.

Invention of the Printing Press

Scientific knowledge could spread much more rapidly because of the printing press. By the second half of the seventeenth century, there were numerous books and newsletters keeping people informed about the most recent scientific discoveries. It is because of the printing press that Thomas Hobbes, sitting in England, was cognizant of scientific discoveries coming out of Italy.

Rivalry Among Nation-States

The constant warfare between the various nation-states may have pushed scientific development by placing an increasing importance on technology, or applied science. Further, Europe was a region with many powerful leaders who could fund scientific development. Columbus, an Italian, could find funding for his voyages from Ferdinand and Isabella of Spain after being turned down by John of Portugal. Compare this to the situation in China; with few technological competitors and a single ruler capable of canceling major projects, Chinese technological development slowed relative to that of Europe.

Reformation

The historian Robert K. Merton suggested a number of years ago that the English who professed Calvinist beliefs were somehow linked to those who were active in the new science. Even earlier than Merton, one of the fathers of sociology, Max Weber, argued that the worldly asceticism found in Protestantism helped create capitalism, which in turn helped propel the Scientific Revolution. These theories, however, ignore the fact that much of the Scientific Revolution came from Catholic Italy. The telescope and microscope, for example, were Italian in origin, as was the new botany. Nevertheless, the Protestant Reformation, by encouraging people to read the Bible, did help create a larger reading public. And although Luther, Calvin, and the like were not interested in challenging the traditional scientific worldview, their opposition to the religious hegemony of Rome did provide a powerful example of challenging established authority.

Renaissance Humanism

Humanist interest in the writings of the classical world also extended to the scientific texts of the ancient Greeks. Certain texts, such as Archimedes’s writings on mathematics and Galen’s anatomical studies, were rediscovered in the Renaissance. Although the Scientific Revolution ultimately rejected the ideas contained in such works, this basic familiarity with the past was a necessary stage in order for modern scientific thought to mature.

PRE-SCIENTIFIC WORLDVIEW

The medieval worldview was based on scholasticism, a synthesis of Christian theology with the scientific beliefs of the ancient authors. The great architect of this synthesis was Thomas Aquinas (1225–1274), who took the works of Aristotle and harmonized them with the teachings of the church. Knowledge of God remained the supreme act of learning and was to be attained through both reason and revelation. The value of science, for those living in the Middle Ages, was that it offered the possibility of a better understanding of the mysterious workings of God. To view science without this religious framework was simply inconceivable in the Middle Ages.

Influenced by the work of Aristotle, medieval people thought that the material world was made up of four elements: earth, air, fire, and water. Earth was the heaviest and the basest of the elements and therefore tended toward the center of the universe. Water was also heavy but lighter than Earth, so its natural place was covering the Earth. Air was above water, with fire as the lightest element of all. It was this notion of the four elements that gave rise to the idea of alchemy, or the perfect compound of the four elements in their perfect proportions. Less perfect metals such as lead might be transformed by changing the proportion of their elements. The four-element approach also dominated the practice of medicine. The four elements combined in the human body to create what were known as the four humours: blood, phlegm, yellow bile, and black bile. An excess of any one of the humours produced one’s essential personal characteristics.

People in the Middle Ages did not have a great interest in astronomy; the popular work of the Greek astronomer Ptolemy (c. 85–165 A.D.) was not questioned. The Ptolemaic, or Geocentric, system placed the Earth as a stationary object around which heavenly bodies moved, while the stars were fixed in their orbits. One problem with this system was addressed rather early: How does one explain the unusual motion of the planets in relation to the fixed stars? At times planets even appeared to be moving backward. To cope with these problems, epicycles—planetary orbits within an orbit—were added to the system.

THE COPERNICAN REVOLUTION

In 1543, Nicholas Copernicus (1473–1543), a Polish mathematician and astronomer, wrote Concerning the Revolutions of the Celestial Spheres. Copernicus was a cleric, and because he was afraid of the implications of the ideas contained in the work, he waited many years before he finally decided to publish. When he finally took that step, Copernicus cautiously dedicated the book to Pope Paul III and included a preface that claimed that the ideas contained in it were just mathematical hypotheses. Even the language of the work was moderate as Copernicus merely suggested that should the Earth revolve around the sun, it would solve at least some of the problematic epicycles of the Ptolemaic system. However, since the Copernican, or Heliocentric, system explains that the planets move in a circular motion around the sun, it did not completely eliminate all the epicycles. Despite his book’s famous reputation, Copernicus’s ideas did not stir a revolution in the way in which people viewed the planets and the stars.

After Copernicus

The Earth-centered system would not go away that quickly. The Danish astronomer Tycho Brahe (1546–1601) tried to come up with a different Earth-centered system rather than just relying on the Ptolemaic system. Brahe had plenty of time on his hands to construct the best astronomical tables of the age, as his social life was nonexistent after he lost part of his nose in a duel and rebuilt it with a prosthetic made of silver and gold alloy. Brahe proposed a system in which the moon and the sun revolved around the Earth, while the other planets revolved around the sun.

Brahe’s student, Johannes Kepler (1571–1630), disagreed with his teacher concerning Copernicus’s findings. Kepler ended up using Brahe’s own data to search for ways to support Copernicus and eventually dropped Copernicus’s “planets move in a circular motion” theory, instead proposing that their orbits were elliptical. However, it would take the greatest mind of the next age, Isaac Newton, to explain why this elliptical motion was in fact possible.

Galileo

The first scientist to build on the work of Copernicus was a Florentine by the name of Galileo Galilei (1564–1642). In 1609, he heard about a Dutchman who had invented a spyglass that allowed distant objects to be seen as if close up. Galileo then designed his own telescope that magnified far-away objects thirty times the naked eye’s capacity. Using this instrument, he noticed that the moon had a mountainous surface very much like the Earth. For Galileo, this provided evidence that it was composed of material similar to that on Earth and not some purer substance as Aristotle had argued. Galileo also realized that the stars were much farther away than the planets. He saw that Jupiter had four moons of her own. This challenged the traditional notion of the unique relationship between Earth and her moon. Sunspots and rings around Saturn also put the whole Ptolemaic construct into doubt.

Galileo was also interested in the question of motion. He may not have really thrown a ten-pound weight and a one-pound weight from the top of the Leaning Tower of Pisa, but he did notice that heavier weights do not fall any faster than lighter ones. He also noticed that under ideal conditions a body in motion would tend to stay in motion. It was therefore relatively easy for him to deduce from this the possibility that Earth is in perpetual motion.

Following the publication of his Dialogues on the Two Chief Systems of the World (1632), the Catholic Church began to condemn Galileo’s work. The Church authorities warned Galileo not to publish any more writings on astronomy. Throwing caution to the wind, he wrote a book that compared the new science with the old; an ignorant clown Simplicio represented the old science. Pope Urban VIII thought the book was making fun of him, and he put Galileo under house arrest for the remainder of his life. This did not stop Galileo from writing, although he was forced to send his manuscripts to Holland where the mood was more tolerant.

Sir Isaac Newton

The greatest figure of the Scientific Revolution was Isaac Newton (1642–1727). Newton wanted to solve the problem posed by the work of Copernicus, Kepler, and Galileo: How do you explain the orderly manner in which the planets revolve around the sun? Newton worked for almost two decades on the problem before he published his masterpiece, Principia, in 1687. Galileo’s work on motion influenced Newton, a sign of the intellectual link between southern and northern scientists. Newton wondered what force kept the planets in an elliptical orbit around the sun, when theoretically they should be moving in a straight line. Supposedly Newton saw an apple drop from a tree and deduced that the same force that drew the apple to the ground may explain planetary motion. Newton finally posited that all planets and objects in the universe operated under the effects of gravity.

It is important to remember that Newton was an extremely religious man and often wondered why, when he delivered public talks, his audiences were more interested in his scientific discoveries than in theology. He spent a great deal of time making silly calculations of biblical dates and practicing alchemy.

More importantly, he began to experiment with optics, thus making the study of light a new scientific endeavor. It was Newton who showed that white light was a heterogeneous mixture of colors rather than the pure light many believed it to be. Newton is also the father of differential calculus (much to the regret of those of you who have to take it in high school). Finally, Newton also eventually became head of the British Royal Society, an organization committed to spreading the new spirit of experimentation.

THE IMPACT OF THE SCIENTIFIC REVOLUTION ON PHILOSOPHY

Among the philosophers affected by the new science was Francis Bacon (1561–1626). Bacon led an extraordinarily varied life. He was a lawyer, an official in the government of James I, a historian, and an essayist. The one thing he did not do in his life, it seems, was perform scientific experiments. What he did contribute to science was the experimental methodology. In his three major works, The Advancement of Learning (1605), Novum Organum (1620), and New Atlantis (1627), Bacon attacked medieval scholasticism with its belief that the body of knowledge was basically complete and that the only task left to scholars was to elaborate on existing knowledge. Instead, Bacon argued that rather than rely on tradition, it was necessary to examine evidence from nature. Bacon’s system became known as inductive reasoning, or empiricism. In France, this debate over the new learning became known as the conflict between the ancients and the moderns, while in England it was known as the “Battle of the Books.”

René Descartes

The French philosopher Descartes (1596–1650) can in some ways be seen as the anti-Bacon. For Descartes, deductive thought (also referred to as Rationalism)—using reason to go from a general principle to the specific principle—provided for a better understanding of the universe than did relying on the experimental method. However, like Bacon, Descartes believed that the ideas of the past were so suffocating that they all must be doubted. In his famous quote, “I think, therefore I am,” Descartes stripped away his belief in everything except his own existence. Another way that Descartes broke with the past was by writing in French rather than Latin, which had been the language of intellectual discourse in the Middle Ages. Descartes was also a highly gifted mathematician who invented analytical mathematics.

Descartes’s system can be found in his Discourse on Method (1637). In the work, he reduced nature to two distinct elements: mind and matter. The world of the mind involved the soul and the spirit, and Descartes left that world to the theologians. The world of matter, however, was made up of an infinite number of particles. He viewed this world as operating in a mechanistic manner, as if in a constant whirlpool that provided contact among the various particles.

Blaise Pascal

Pascal (1623–1662) saw his life as a balancing act. He wanted to balance what he saw as the dogmatic thinking of the Jesuits with those who were complete religious skeptics. His life’s attempt to achieve this balance is found in his Pensées, particularly in the idea that became known as Pascal’s Wager, in which Pascal concluded that it was better to wager on the existence of God than on the obverse, since the expected value that comes from believing is always greater than the expected value of not believing. Pascal became involved with the Jansenists, a Catholic faction that saw truth in St. Augustine’s idea of the total sinfulness of mankind and the need for salvation to be achieved through faith because we are predestined—ideas that were also followed by the Calvinists.

Thomas Hobbes

Thomas Hobbes (1588–1679) personally knew Galileo, Bacon, and Descartes and was also friends with William Harvey (1578–1657), who, rather than relying on the writings of the Ancient Greeks, used dissections to show the role the heart plays in the circulation of blood through the body. His contact with the leading figures in the world of science influenced Hobbes to apply the experimental methods they used in the study of nature to the study of politics. Hobbes was horrified by the turmoil of the English Revolution and was convinced of the depravity of human nature; man was like an animal in that he was stimulated by appetites rather than by noble ideas. Hobbes wrote in his classic work, Leviathan, that life without government was “nasty, brutish, and short.”

Hobbes’s view of the depravity of human nature led him to propose the necessity for absolutism. Man formed states, or what Hobbes called the great Leviathan, because they were necessary constructs that worked to restrain the human urges to destroy one another. Out of necessity, the sovereign has complete and total power over his subjects. The subjects are obliged never to rebel, and the sovereign must put down rebellion by any means possible. When the parliamentary side won the civil war, Hobbes went back to England and quietly went on with his life. He readily accepted any established power, and could therefore live under Cromwell’s firm rule. His theories did not please traditional English royalists, since his brand of absolutism was not based on the divine right theory of kingship.

John Locke

Like Hobbes, John Locke (1632–1704) was interested in the world of science. His Two Treatises on Government, written before the Revolution of 1688, was published after William and Mary came to the throne and served as a defense of the revolution as well as a basis for the English Bill of Rights. It also proved critical for the intellectual development of the founders of the United States. Locke argued that man is born free in nature, although as society gets more advanced, government is needed to organize this society. Because man is a free and rational entity, when he enters into a social contract with the state, he does not give up his inalienable rights to life, liberty, and property. Should an oppressive government challenge those rights, man has a right to rebel.

Locke was an opponent of religious enthusiasm. In his Letter Concerning Toleration, Locke attacked the idea that Christianity could be spread by force. His influential Essay on Human Understanding contained the idea that children enter the world with no set ideas. At birth, the mind is a blank slate or tabula rasa, and infants do not possess the Christian concept of predestination or original sin. Instead, Locke subscribed to the theory that all knowledge was empirical in that it comes from experience.

Scientists and Philosophers of the Scientific Revolution, 1450–1700

THE EIGHTEENTH-CENTURY ENLIGHTENMENT

Although his response has become a bit of a cliché, there is no better answer to the question “What is the Enlightenment?” than that offered by the German philosopher Immanuel Kant (1724–1804). For Kant, the answer was clear: “Dare to know.” By this, he meant that it was necessary for individuals to cast off those ideas of the past that had been accepted simply because of tradition or intellectual laziness and instead use one’s reason to probe for answers to questions on the nature of mankind. The ultimate reward, stated Kant, would be something that all previous generations had so woefully lacked—freedom. This freedom would extend to the political and religious realms and would also lead the writers of the Enlightenment to cast doubt on such ancient human practices as slavery.

Traditionally, the Enlightenment has been associated with France, where they use the term philosophes to describe the thinkers of the age. These philosophes were not organized in any formal group, although many of the most prominent displayed their erudition at salons, which were informal discussion groups organized by wealthy women. Others would hang around the print shop putting the final touches on their pamphlets. No matter where their ideas were produced, French thinkers helped produce the so-called “Republic of Letters,” an international community of writers who communicated in French. This Republic of Letters extended throughout much of western Europe and, of course, to the American colonies, where the ideas of the Enlightenment would play a significant role in the founding of the United States.

The direction of the Enlightenment changed over the course of the eighteenth century. The early Enlightenment was deeply rooted in the Scientific Revolution and was profoundly influenced by Great Britain, which appeared to continental writers as a bastion of freedom and economic expansion, while also providing the world with such inestimable thinkers as John Locke. Locke’s idea, expressed in his Essay Concerning Human Understanding, that the individual is a blank slate at birth, provided a powerful argument for the potential impact of education as well as for the inherent equality among all people. Locke also greatly influenced eighteenth-century thought through his contention that every person has the right to life, liberty, and property, and that there is a contractual relationship between the ruler and the subjects.

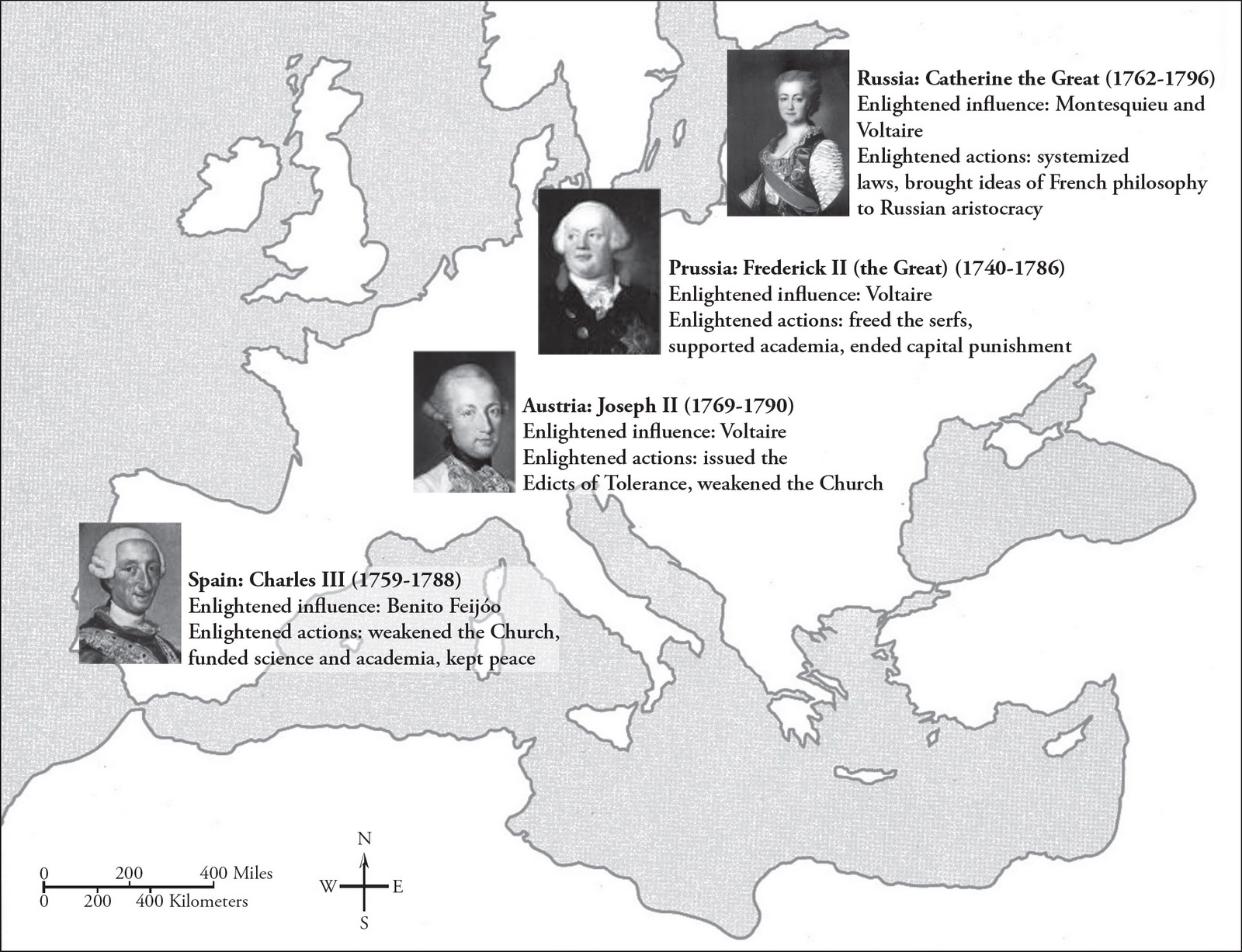

As the age of Enlightenment continued, it moved beyond the influence of Locke, who had refused to see how freedom could be granted to slaves in the Americas. Writers such as Voltaire and David Hume would offer a powerful challenge to established religion. By the end of the century, people such as Adam Smith had veered into other areas such as economic thought. Jean-Jacques Rousseau inspired people of the age to seek to find truth not through the cold application of reason, but rather through a thorough examination of their inner emotions. Meanwhile, in places such as Russia, Prussia, and Austria, rulers sought to find ways to blend their royal absolutism with some of the ideas of the Enlightenment, although little would come out of this attempt except perhaps a further enhancement of their absolute authority.

Voltaire

Perhaps the greatest of the philosophes was Voltaire (1694–1778). After writing a number of rather forgettable volumes of poetry and drama, Voltaire went to England, a trip that would forever change his life. He was struck by the relative religious tolerance practiced there as well as the freedom to express one’s ideas in print—far greater than that which existed in France. Voltaire was also struck by the honor the English showed Newton when the scientist was buried with great pomp at a state funeral. To Voltaire, England seemed to offer those things that allowed for the happiness of the individual, which seemed so desperately lacking in his own land of France.

Although educated by the Jesuits, Voltaire hated the Catholic Church and despised what he thought was the narrowness and bigotry that was at the heart of all religious traditions. Voltaire, like many of his contemporaries, was a deist, one who believes that God created the universe and then stepped back from creation to allow it to operate under the laws of science. Voltaire felt that religion crushed the human spirit and that to be free, man needed to Écrasez l’infame! (Crush the horrible thing!)—his famous anti-religious slogan.

Voltaire became an intellectual celebrity across Europe following his involvement in the case of Jean Calas, a French Protestant who was falsely accused of murdering his son after learning that the son was planning to convert to Catholicism. In 1762, the Parlement of Toulouse ordered Calas’s execution, and he was brutally tortured to death. In the following year, Voltaire published his Treatise on Toleration and pushed for a reexamination of the evidence. By 1765, the authorities reversed their decision, and while it was obviously too late to aid the unfortunate Calas, Voltaire was able to use the case as a lynchpin in his fight against religious dogmatism and intolerance, one of the greatest legacies of the Enlightenment.

Voltaire’s Famous Candide

Voltaire’s most famous work is Candide (1759), which he was inspired to write following an earthquake that completely leveled the city of Lisbon in 1755. Voltaire was particularly struck by the story of a group of parishioners who, following the earthquake, went back into their church to give thanks to God for sparing their lives, only to have the weakened foundations of the church collapse on them. One of the false stereotypes concerning the Enlightenment is that it was fundamentally optimistic. Candide is a deeply pessimistic work, as young Candide and his traveling companions meet with one disaster after another. The book basically touts the idea that humans cannot expect to find contentment by connecting themselves with a specific philosophical system. Instead, the best one can hope for is a sort of private, inner solace, or as Voltaire put it, “one must cultivate one’s own garden.”

Montesquieu

Charles Louis de Secondat, Baron de Montesquieu (1689–1755), wrote what was perhaps the most influential work of the Enlightenment, Spirit of the Laws (1748). Montesquieu, who became president of the Parlement of Bordeaux, a body of nobles that functioned as the province’s law court, was, like Voltaire, inspired by the political system found in Great Britain. He incorrectly interpreted the British constitution, and in the Spirit of the Laws, Montesquieu wrote of the English separation of powers among the various branches of government providing for the possibility of checks and balances, something that did not exist in the British system. In many ways Montesquieu was a political conservative who did not believe in a republic—which he associated with anarchy—but rather wanted France to reestablish aristocratic authority as a means of placing limits on royal absolutism.

In an earlier work, Persian Letters (1721), Montesquieu critiques his native France through a series of letters between two Persians traveling in Europe. To avoid royal and church censorship, Montesquieu executed a deeply satirical work that attacked religious zealotry, while also implying that despite the differences between the Islamic East and the Christian West, a universal system of justice was necessary. Another aspect of Montesquieu’s universal ideals was his anti-slavery sentiment; he deplored slavery as being against natural law.

Diderot and the Encyclopedia

The Encyclopedia, the brainchild of Denis Diderot (1713–1784), was one of the greatest collaborative achievements of the Enlightenment and was executed by the community of scholars known as the Republic of Letters. The Encylopedia exemplifies the eighteenth-century belief that all knowledge could be organized and presented in a scientific manner. The first of 28 volumes appeared in 1751, with such luminaries as Voltaire, Montesquieu, and Rousseau contributing articles. Diderot, the son of an artisan, also had a great deal of respect for those who worked with their hands, and included articles on various tools and the ways in which they made people more productive.

The Encyclopedia was also important for spreading Enlightenment ideas beyond the borders of France; copies were sent to places as far away as Russia and Scandinavia, and on the American shores, Thomas Jefferson and Benjamin Franklin purchased their own sets. In various parts of Europe, the work was attacked by the censors, particularly in places like Italy where the Catholic Church was highly critical of what it viewed as thinly veiled attacks on its religious practices. In France, the work was at various times placed under the censor’s ban, since it was highly critical of monarchical authority. Ironically, Diderot had to turn to the throne for protection of his copyright when printers published pirated copies.

Jean-Jacques Rousseau

Enlightenment thought did not consist of a single intellectual strand. The work of Rousseau (1712–1778) provides one of the best examples of this fact. He lived a deeply troubled and solitary existence, and at one point or another antagonized many of the other leading philosophes, including Voltaire, who hated Rousseau’s championing of emotion over reason. Rousseau was perhaps the most radical of the philosophes. Unlike many of the philosophes who believed in a constitutional monarchy as the best form of government, Rousseau believed in the creation of a direct democracy. Although during his lifetime his works were not widely read, following Rousseau’s death, his ideas became far more influential, and many of the leading participants in the more radical stages of the French Revolution studied his work.

His greatest achievement, The Social Contract (1762), begins with the classic line: “All men are born free, but everywhere they are in chains.” He once again differed from many of the other philosophes, however, in that he had little faith in the individual’s potential to use reason as a means of leading a more satisfactory life. Instead, Rousseau explained that the focus needed to be placed on reforming the overall community, since only through the individual’s attachment to a larger society could the powerless people hope to achieve much of anything. Sovereignty would be expressed in this ideal society not through the will of the king but rather via the general will of the populace; only by surrendering to this general will could the individual hope to find genuine freedom.

Rousseau and Romanticism

Rousseau helped set the stage for the Romantic Movement of the late eighteenth and nineteenth centuries. His pedagogical novel Émile (1762) deals with a young man who receives an education that places higher regard on developing his emotions over his reason. To achieve this, the character Émile is encouraged to explore nature as a means of heightening his emotional sensitivity. Rousseau was also important for emphasizing the differences between children and adults. He argued that there were stages of development during which the child needed to be allowed to grow freely without undue influence from the adult world.

THE SPREAD OF ENLIGHTENMENT THOUGHT

Although originally rooted in France, over the course of the eighteenth century, the Enlightenment spread to other parts of Europe.

Germany

The greatest figure of the German Enlightenment, Immanuel Kant (1724–1804), argued in his Critique of Pure Reason (1781) against the idea that all knowledge was empirical, since the mind shapes the world through its unique experiences. Like Rousseau, Kant’s emphasis that other, possibly hidden, layers of knowledge exist beyond the knowledge that could be achieved through the use of reason served to inspire a generation of Romantic artists, who felt stifled by the application of pure reason.

Italy

In Italy, Cesare Beccaria (1738–1794), in his work On Crimes and Punishment (1764), called for a complete overhaul in the area of jurisprudence. For Beccaria, it was clear that those who were accused of perpetrating crimes should also be allowed certain basic rights, and he argued against such common practices of the day as the use of torture to gain admissions of guilt as well as the application of capital punishment. Beccaria’s work can be seen as part of the overall theme of humanitarianism found in the Enlightenment, which extended from such areas as the push to end flogging in the British navy to the call for better treatment of animals.

Scotland

One of the most vibrant intellectual centers of the eighteenth century was Scotland, a place that hitherto had not been at the center of European intellectual life. The philosopher David Hume (1711–1776) pushed his thinking further than French deists and delved directly into the world of atheism. In Inquiry into Human Nature, Hume cast complete doubt on revealed religion, arguing that no empirical evidence supported the existence of those miracles that stood at the heart of Christian tradition.

Another Scottish author, Edward Gibbon (1737–1794), reflected the growing interest in history that was first seen during the Enlightenment with his monumental Decline and Fall of the Roman Empire. His work criticized Christianity in that he viewed its rise within the Roman Empire as a social phenomenon rather than a divine interference. He also asserted that Christianity weakened the vibrancy of the Empire and contributed to its fall.

The Scottish Enlightenment also made a huge impact on economic thought through the work of Adam Smith (1723–1790), a professor at the University of Glasgow. In 1776, Smith published Inquiry into the Nature and Causes of the Wealth of Nations, in which he argued against mercantilism, a term that refers to the system of navigation acts, tariffs, and monopolies that stood as the economic underpinnings for most of the nations of Europe. Smith became associated with the concept of laissez-faire, literally to “leave alone,” since he argued that individuals should be free to pursue economic gain without being restricted by the state. Rather than producing economic anarchy, such a system would be self-regulating, as if controlled by an invisible hand, which would lead to the meeting of supply and demand. Smith’s thinking proved influential for both the Manchester School of economists in England and the Physiocrats in France.

WOMEN AND THE ENLIGHTENMENT

Women figured prominently in the Enlightenment; most of the Parisian salons were organized by women. At times, these wealthy and aristocratic individuals would use their social and political connections to help the philosophes avoid trouble with the authorities or perhaps aid them in receiving some sort of government sinecure to allow them greater freedom to work. Perhaps surprisingly, given the great help that women proffered to the philosophes, these male thinkers for the most part were not tremendous advocates of the rights and abilities of women. The Encyclopedia barely bothered to address the condition of women, although the work may never have reached the reading public without the aid of the Marquise de Pompadour, Louis XV’s mistress, who played a critical role in helping Diderot avoid censorship.

Some writers were more sympathetic to women’s issues than others. Montesquieu, in his Persian Letters, included a discussion of the restrictive nature of the Eastern harem, which by implication, was a criticism of the treatment of women in western Europe. Rousseau, on the other hand, while a radical on many issues, was an advocate of the idea that men and women occupied separate spheres and that women should not be granted an equal education to men. By the end of the century, inspired partially by the French Revolution and partially by the Enlightenment, the Englishwoman Mary Wollstonecraft (1759–1797) wrote in her Vindication of the Rights of Women that women should enjoy the right to vote as well as to hold political office, the first openly published statement of such ideas.

THAT’S A LOT OF NAMES, HUH?

Many AP European History students struggle with the sheer volume of ideas and thinkers during the Age of Enlightenment. Check out this handy graphic to help you review who said what and hailed from where.

EUROPEAN POWERS IN THE AGE OF ENLIGHTENMENT

The eighteenth century witnessed a number of significant developments for the European nation-states. Two major powers, Prussia and Russia, emerged over the course of the century, while Austria, France, and Great Britain adjusted to changing political, economic, and social circumstances.