Peel your onions and boil them very slow for a qr of an hour lard them and put them into a small crock with melted butter, pepper and salt, bake them in a smart oven the crock must not be covered half an hour is enough drain them from the oil, put some good gravy under them and serve them up.

—from an 18th century Irish cookbook manuscript

Traditionally, the Irish aren’t big snackers. As an agrarian society, the day was punctuated by a large breakfast, a big midday dinner, and a lighter evening supper, or “tea,” as the evening meal is still known in many homes. Add in the religious element with its various times for fasting and strictures on what could be eaten during which times, and you get some pretty strong food habits that do not include a lot of eating outside of mealtimes. Times have changed, certainly; when I was a child, we were never given food when it wasn’t mealtime, whereas my own children sometimes seem to have more snacks than meals! And yet, there are smaller bites that are traditionally Irish, whether they form the basis of a light meal or a hasty nibble before going out to the pub or after coming home. Some, such as Potted Shrimp, can also serve as an elegant starter to a heavier meal, perhaps served with toast points; but if you slather it on a thick slab of buttered bread, it’s a great midnight snack. In general, however, we like our sandwiches simple and thin. They’re no less savory and delicious for that.

“Potting” fish or meats was an old way of storing them. Leftover meats such as chicken or ham or seafood such as fish or shrimp were pounded together with nearly an equal quantity of butter (I use a little less) to make a rough paste, then seasoned with salt and mace, nutmeg, or another warm spice. The paste was then poured into a small container and covered with clarified butter, sealing out the air so it could be stored in a cool pantry. Because it’s now stored in the refrigerator, I don’t bother to clarify the butter—the milk solids don’t bother me or affect the flavor. And I don’t “pound” it but simply run it through the food processor. (Some recipes use tiny shrimp and leave them whole in the butter.) The lemon juice is not traditional, but it ties all the flavors together well. Served on crisp, hot thin toast or with crackers or bread, it’s an excellent light lunch, a starter, or even a savory at the end of a meal.

Makes about 3 cups

½ cup (1 stick) butter, plus ¼ cup (½ stick) melted butter (or a little more as needed)

8 ounces medium raw shrimp, peeled (about 2 cups)

1 tablespoon lemon juice

teaspoon freshly grated nutmeg

teaspoon freshly grated nutmeg

Salt and pepper

1 In a large skillet over medium-low heat, melt the ½ cup of butter. Add the shrimp and increase the heat slightly. Cook, stirring frequently, just until the shrimp is pink and opaque, 3 to 4 minutes. Do not overcook or the shrimp will be tough and rubbery.

2 Turn the shrimp into a food processor. Add the lemon juice and nutmeg and a sprinkle of salt and pepper. Process to form a coarse paste. Taste and add salt or lemon juice if needed.

3 Divide the shrimp paste among 2 or 3 ramekins or small bowls (or one larger dish, but smaller ones are more common) and smooth the surface with the back of a spoon. Pour the remaining melted butter over the top of each to make an even layer that seals the entire surface. Store in the refrigerator for up to a week.

Substitute 2 cups cooked, skinless, boneless wild salmon for the shrimp

Substitute 2 cups cooked, skinless, boneless chicken breast for the shrimp, leave out the lemon juice, and season the mixture with ground mace instead of nutmeg.

Substitute 2 cups cooked, cubed ham for the shrimp, leave out the lemon juice, and season the mixture with ground mace instead of nutmeg.

Pigs’ feet, boiled with aromatics, were a hand food, perhaps to be eaten out of hand during a day at the horse races or at a country fair. They were a specialty food that turned up at public events and special occasions, not necessarily something that was a regular staple in shops. They’re sticky and unctuous, and you nibble the bits of tender, succulent meat off the bone. Pork is so widely eaten in Ireland that pigs’ trotters are readily available at butcher shops.

8 pigs’ trotters

2 medium yellow onions

1 large carrot

2 tablespoons kosher salt (or 1 tablespoon table salt)

3 to 4 sprigs fresh thyme

½ teaspoon whole black peppercorns

10 whole cloves

1 Put all the ingredients in a large, heavy stewpot and cover with water. Bring to a boil over high heat. Reduce to medium and simmer gently, loosely covered for 3 to 4 hours until the meat is completely tender. Cool slightly and serve just warm enough to handle.

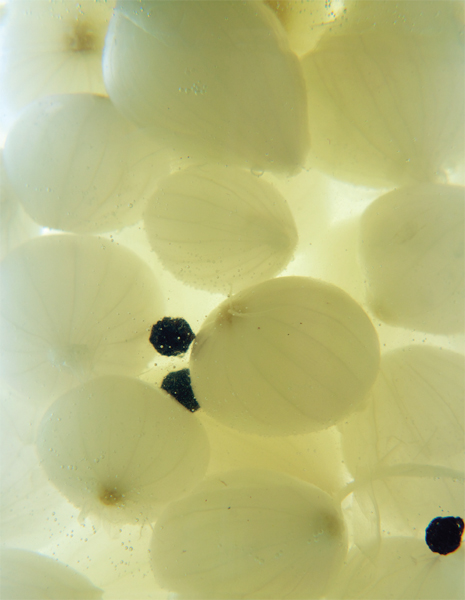

If you’re eating a cheese sandwich and something seems to be missing . . . it’s probably that you need a pickled onion or two alongside. Back in the old days, there wasn’t that much food in Irish pubs, but in country pubs you might see a jar or bowl of pickled onions, and you could have one free with your pint. Salty and tangy, it’s just a savory little bite that sort of whets your appetite. They were considered to be packed with vitamins, and the vinegar was thought to help digestion. Salting the onions first helps keep them crisp. (If you don’t have pickling salt, you can use kosher, but be sure it’s the kind without additives like anti-caking agents.)

Makes 2 cups

½ cup pickling salt

1 pound pearl onions (about 2 cups), trimmed and peeled

2 cups white vinegar

3 tablespoons sugar

12 whole black peppercorns

1 bay leaf

1 Put 3 cups of water in a medium glass or ceramic bowl (not metal) and stir in the salt to dissolve. Add the onions and lay a small plate on top to hold them underwater. Leave them for 2 days. Drain and rinse them.

2 In a medium saucepan over medium heat, boil the vinegar, sugar and peppercorns. Set aside to cool.

3 Pack the onions into a glass jar (because of their size, you may need a quart jar to hold them). Add the bay leaf, pour on the vinegar, and cover the jar. Refrigerate at least 2 weeks before eating them. The onions will last for several months.

Irish crab is excellent. Stone crabs in particular taste deeply “crabby.” They tend to be very large, and they’re fresh, sweet, briny, meaty, and packed with flavor. “Devilling” foods is an old tradition in the British Isles, a sort of creamy and mustard-sharp treatment that piques your taste buds and heightens the natural sweetness of the food. Devilled crab is often served in the cleaned shells, but it’s just as good in individual ramekins or a shallow single casserole.

Serves 4

For the devilled crab:

½ cup heavy cream

½ cup chopped parsley

1 stalk celery, finely chopped

2 scallions, thinly sliced

1½ teaspoons dry mustard powder

1 teaspoon salt

1½ pounds crabmeat

For the topping:

½ cup breadcrumbs

¼ cup (½ stick) butter, melted

1 Preheat oven to 350 degrees F and butter 48-ounce ramekins or a shallow 1-quart casserole.

2 Combine all the devilled crab ingredients but the crab in a mixing bowl, tossing well to combine.

3 Gently turn the crabmeat into the mixture, folding just to combine but being careful not to break up the chunks of meat too much.

4 Divide the mixture among the prepared ramekins or spread it in the casserole. Sprinkle with breadcrumbs and drizzle with the melted butter. Bake for 25 minutes, until bubbling and browned. Serve hot.

Irish sandwiches tend to be quite thin by American standards. In general, we don’t like hugely overstuffed sandwiches, preferring thin and savory fillings on thin-sliced bread. The difference is, we eat a lot of them at once! Here are some standard Irish sandwich fillings, to be made on white, brown or granary (multigrain) pans (or sliced commercial loaves). The bread is usually buttered first and nearly all sandwiches are cut diagonally into two triangles, never two rectangles.

Mash four hardboiled eggs with the back of a fork and stir in 1/4 cup mayonnaise, 1 tablespoon chopped chives (or finely minced scallion), and season with salt and pepper.

Layer onto buttered white bread 1/4-inch slices of white cheddar, a few thin slices of ripe tomato, and just enough onion, cut into paper-thin rings, for flavor.

Drain a 6-ounce can of tuna and mix with 3 tablespoons mayonnaise and 1/4 cup of drained canned corn. Spread on buttered brown pan. Sometimes the tuna is topped with a layer of coleslaw made with cabbage, shredded carrot, and mayonnaise—this is surprisingly delicious.

I can’t claim I was deeply into this sandwich, but it’s enduringly popular, particularly after an evening in the pub: Butter two slices of white pan and line one with a row of thick-cut French fries (the “chips”). Top with ketchup or brown sauce, as desired. Then with the other slice of buttered bread, crush together, and eat without cutting.

The “farmhouse” part of the title has become inseparable from “vegetable soup,” but it does conjure up images of a hearty pot of wholesome soup on the back of the range in a farm kitchen. Farmhouse vegetable soup also tends to be mostly puréed, with just a few chunks of visible vegetable left floating. And it’s often enriched with a dash of heavy cream, but it’s no problem to leave that out. I love this simple soup with crunchy, freshly made croutons floating on the surface. They only take a few moments to prepare.

Makes 4 to 6 servings

2 tablespoons butter

2 medium yellow onions, chopped

3 stalks celery, thinly sliced

4 large russet potatoes, peeled and diced

2 large carrots, diced

2 quarts (8 cups) chicken stock

1 teaspoon fresh thyme leaves

½ teaspoon dried sage

1 cup frozen peas

¼ cup heavy cream (optional)

Salt and pepper

Croutons for serving:

2 thick slices good bakery bread

3 tablespoons olive oil

1 Heat the butter in a large, heavy soup pot over medium heat. Stir in the onions and celery, and put the lid on the pot. Cook the vegetables covered for 6 to 7 minutes, so they steam and soften but do not brown.

2 Add the potatoes, carrots, stock, thyme, and sage. Bring to a boil, cover loosely, and simmer for 20 to 25 minutes, until all the vegetables are tender. Add the peas for the last 5 minutes of cooking time.

3 Add the cream, if using, and season to taste with salt and pepper. Using an immersion blender, purée most of the soup, leaving a few visible chunks of vegetables.

4 To serve, cut the crusts off the bread and trim the slices into 1/2-inch cubes. Heat the oil in a nonstick skillet over medium heat, add the bread, and fry briskly, shaking the pan and turning the croutons, until golden brown, 3 to 4 minutes. Spoon the soup into bowls and sprinkle with croutons.

We love celery in Ireland, and I ate a lot of it growing up. Funny enough, almost never in the raw form, as in celery sticks, but always cooked in soups and stews, and also cooked in thick slices until tender and tossed in a buttery cream sauce as a side dish. My American wife had almost the opposite experience: she mostly ate it raw, in salads or with tuna, perhaps stuffed with peanut butter, so she was surprised to see how often it showed up on Irish tables as a cooked side dish. Celery’s delicate, sweet flavor makes a wonderful soup.

Makes 6 servings

¼ cup (½ stick) butter

1 head celery (about 1 pound), trimmed and sliced thin

2 large russet potatoes, peeled and diced

2 medium yellow onions, chopped

2 quarts (8 cups) chicken stock

1 bay leaf

¼ teaspoon ground nutmeg

1 cup light cream

Salt and pepper

1 Melt the butter in a large, heavy soup pot over medium heat. Stir in the celery, potatoes, and onion, and cover the pot. Cook for 6 to 7 minutes, to soften the vegetables without browning them.

2 Add the stock, bay leaf, and nutmeg. Bring to a boil, reduce heat, and simmer gently for 20 to 25 minutes, until the vegetables are completely tender. Remove the bay leaf, and with an immersion blender, purée the soup until completely smooth. Stir in the cream, heat through, and season to taste with salt and pepper.

This soup shows up on menu after menu, because it features two favorite Irish vegetables. On its own, a plain potato soup has the potential to be sort of heavy and bland. Add flavorful leeks with their vaguely squeaky texture between the teeth, and the soup lightens up and takes on character. Be sure to wash the leeks after slicing so you get out any dirt hiding between the layers.

Makes 6 servings

¼ cup (½ stick) butter

6 large russet potatoes

2 to 3 leeks, trimmed, white and green parts sliced, and well washed

2 quarts (8 cups) chicken stock

2 cups light cream (or whole milk)

Salt and pepper

1 Melt the butter in a large, heavy soup pot over medium heat. Stir in the potatoes and leeks, and cover the pot. Cook for 6 to 7 minutes, to soften the vegetables without browning them.

2 Add the stock, bring to a boil, reduce heat, and simmer for 25 to 30 minutes, until the potatoes are completely tender and falling apart to thicken the soup.

3 Stir in the cream or milk, heat through, and season to taste with salt and pepper. If you like, you can eat this soup as is, with thinner broth and chunks of vegetables, or puree it partially, or purée it into a smooth cream. It’s good whatever you do.

Two of my brothers were prone to eczema, so my mother used to take them to see the local “bonesetter,” as neighborhood healers were known. Some bonesetters in Ireland were truly famous for their healing powers, and it’s a fine tradition that modern science has not completely killed off, especially in the country. That’s because a lot of bonesetters know exactly what they’re doing when it comes to herbal treatments, and this soup is a prime example. Not only did my two brothers have to eat it, we all had it as a sort of spring tonic. It cleared up their skin and made us all feel sprightly. Now I don’t eat it for health but only as a foraging gourmet, because nettles have a terrific fresh green taste, reminiscent of spinach, but without tannic undertones. Wear gloves and long sleeves to collect and wash them. Once they hit the hot water, their stinging power is gone. Also, be sure to use the tender young shoots of early spring; later the stalks get tough.

Makes 4 servings

¼ cup (½ stick) butter

2 leeks, trimmed, sliced, and well washed

1 medium yellow onion, chopped

4 large russet potatoes, peeled and diced

2 quarts (8 cups) chicken stock

1 pound fresh nettles (pick when no higher than 12 inches), well rinsed

1 cup heavy cream, Greek yogurt, or crème fraÎche (or more for serving)

Salt and pepper

1 In a large, heavy soup pot over medium heat, melt the butter and add the leek, onion, and potato. Stir to coat with the butter, then cover and cook 6 to 7 minutes to soften the vegetables without browning.

2 Add the stock and bring to a boil. While the soup is boiling, stir in the nettles by handfuls (don’t forget your gloves!). They’ll wilt, and you can add more.

3 When all the nettles have been added, reduce heat and simmer the soup for 25 to 30 minutes until the vegetables are completely tender.

4 Purée the soup using an immersion blender (or carefully, in batches, in a blender or food processor) until completely smooth. Stir in the cream, yogurt, or crème fraiche and season to taste with salt and pepper. If you like, swirl a little more of the dairy product on top of each bowl of soup.