Introduction

In a Surrey lane aged about three and a half having suffered a mishap.

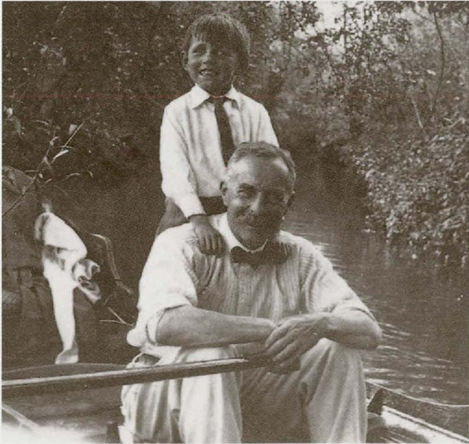

In a Thames backwater with my father, aged about seven.

To have reached the age of eighty years more or less unscathed is by no means une affaire mince, an insignificant matter, which is how a French friend of more or less the same age described it. How I contrived to reach sixty and then seventy without noticing it is still a mystery to me. When I was young, sixty-five was the age when bank managers (a species now becoming extinct) used to retire. They were good, clean living chaps who, in the not too distant past had played cricket and rugger on Saturdays against teams from other banks. This was the moment when, having arrived at the age of sixty-five, they were given gold watches, and in the nicest possible way told to make themselves scarce (otherwise given the chop). It was said, and widely believed, that within a year of receiving their awards – and marching orders – many of them would be dead. But being eighty-eight plus is a different matter (mince) altogether. This is the time when sprightly septuagenarians start giving up their seats to us eighty-year-olds on public transport and those who bid us ‘mind how you go!’ really mean it.

What was I doing when I passed through a number of ‘valleys of death’ unscathed? I am still trying to remember what I was up to all those years, when I could have been the recipient of a gold watch, if I had been a bank manager. Some of the time I must have been managing something myself– something I have never been conspicuously good at.

Only recently have I begun to appreciate the fascination my father must have felt when he himself was well over eighty and met a gentleman who had presented him with a visiting card on which were embossed the words ‘Mr Thos. W. Bowler,’ followed by an address in Walton-on-Thames which conjured up visions of a rather fine riverside house. To which my father had added the following codicil in neat pencil: ‘Met on train. The originator of the Bowler Hat?’ Like a man of the Renaissance my father was constantly being overcome by the wonders of the world in which he lived. Walking down a street he would suddenly glimpse some odd cloud formation, or a man with a goitrous protuberance, and without warning would stop in his tracks in order to enjoy the sight more closely.

As a result the simplest excursion made by our family resembled an extended streetfighting patrol in hostile territory, its members taking up entire streets.

Castelnau Mansions, Barnes, SW13. The flats in which I was born by Hammersmith Bridge.

With my mother, aged eight

My upbringing was Victorian. My father, when he was at home, strict. If I didn’t eat my greens (and I really hated them) at lunchtime on Sundays, they would appear again, cold for tea. I grew up with a strong constitution – my father saw that as an aid to victory – my bowels were kept open and my nasal passages unclogged. I was forced to sniff salt water up my nose, and to take plenty of cold baths as an aid against filthy thoughts – it doesn’t work.

His ambition was that I should win the Diamond Sculls at Henley. I didn’t. But I did learn to scull stylishly, as did my mother, in our sumptuous double-sculling skiff which was big enough to sleep three people. My mother was very much younger than my father. She had been a model girl in my father’s fashion business, and still accompanied him when he travelled, which was often.

It was also inculcated in me that work was important and that it was slightly wrong to enjoy oneself, although it didn’t inhibit my father, mother and me from doing so.

It was not my father who dinned into me ‘The Importance of Success in Business,’ but my odious uncle – my father’s brother. He was the managing director of a large department store. His Christmas present to me, when I was about ten, was a book – Lessons of a Selfmade Merchant to his Son (exhortations on how to do down the opposition and short change the customers). I told him what I had done when I put it in a wastepaper basket.

With a school friend going camping in Surrey, 1934

With my parents and an uncle and aunt on a South Coast beach

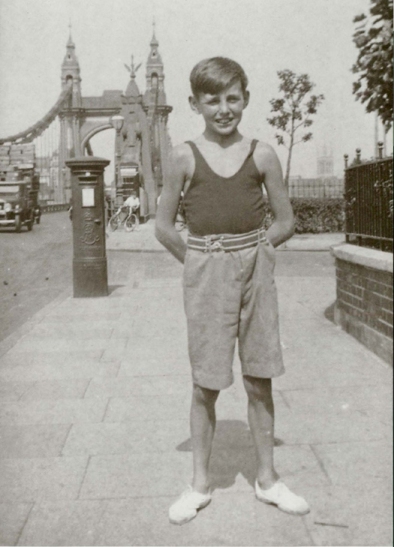

By Hammersmith Bridge, outside our flat

At this time I experienced a great feeling of inferiority at my inability to cope with problems of a mathematical nature which had to be solved algebraically. At that time (in the 1930s) a pass in Mathematics was obligatory. In spite of being good in History and English, I failed Mathematics. I was sixteen so my father took me away from St Pauls and put me into a fashionable advertising agency in W1. Two years later I left it to go to sea.

It is the sea that has influenced me most, although I am no great sailor, an oarsman more than a mariner. Introduce me to a sailing ship sailor who hasn’t been influenced by it. There is nothing more unpredictable than a sailing ship, engineless, at the mercy of the winds and currents. And there were times when the ship would show her different faces: when she was running with 63,000 sacks of grain under the hatches, or utterly becalmed in an oily sea with turtles sunbathing around her. Then there was the sound of the storm in the rigging, nothing more awesome in all the world, and going aloft in it and working the winches and grinding away at the capstans; and hearing but not seeing whales surfacing around the ship in dense fog. And St Elmo’s fire (the corposants) running along the steelyards until they seemed to be ablaze.

The year I left school (1936) and went into advertising.

And the ship itself – washing it down, chipping the rust off it, inside and out on the way to Australia, the darkness of the hold in ballast, and then red leading the great dark heart of it, like a cathedral. And washing for the crew, and cleaning the loos, and cleaning the pigs and their sties and chasing what never seemed less than half a million bedbugs below decks.

But you would die for your ship if called upon to do so, in order that she and the rest might survive. These influences will remain with me until I die.

My life has been an exercise in erratic navigation – I can see that now. Looking back on it I realise how very unpredictable it has been. But somehow I feel I can’t take the entire responsibility for what has happened. Often it has been as if a chunk of raw material has been offered to me and I have either taken or rejected it. I’ve been very lucky, both man and boy. I’ve had health and strength and quite early on the way I was able to appreciate the extraordinary diversity of the world, its beauty and mystery, as well as to witness its horrors.

With my wife Wanda, Rome 1948. We married in Florence in 1946.

Self 1945

E and W, Salcombe, Devon 1947

With daughter Sonia aged four at Hammersmith

Family at the races, Epsom 1950

In the garden of our flat by Hammersmith Bridge with Wanda and Sonia.

I didn’t get wounded or drowned off Sicily in 1941, or fall off the mountain I was trying to get to the top of (with a friend) in the Hindu Kush, in 1956. Nor did I fall in 1938, when I was blown out of the rigging of a four-masted barque, from 160 feet up – a friendly wind blew me back into it.

If all this – the description of my life sounds all too perfect, as if I am trying to make myself out to be an efficient, omnipotent traveller, I want to let it be known that this is not so. In fact I am horribly untidy. I can reduce a railway compartment to a shambles in two minutes flat and panic if my luggage is out of sight for more than a few seconds, which some might regard as a reasonable character defect. And as I get older I have become a worrier. A few days ago I was told that I was becoming a chronic worrier. The future looks black.

Several books have been a great inspiration to me. One of the books that did the most to influence me in my pursuit of the open air life was Horace Kephart’s Camping and Woodcraft: A Hand book for Vacation Campers and for Travellers in the Wilderness. The others were The Happy Traveller: A book for Poor Men by Frank Tatchell, Vicar of Midhurst. He travelled so extensively that it must have been awkward for him to function as a vicar at all. Another book that was a great inspiration was The Children’s Colour Book of Lands and Peoples, which I wrote about in A Travellers Life. Kephart’s book was first published in New York in 1917. He travelled widely in the North American wilderness, and remained in it for long periods, building cabins as the spirit moved him and later, in his book, giving advice on how to build secret camps.

Staying at a stately home in Italy. Eric, Wanda and family and Chicchi Mapelli Mozzi.

Wash and brush up for the family while camping in the Dolomites 1954.

Camping in France with specially made tents

The book begins with a description of how to build a luncheon fire, and later a dinner fire. ‘So, in twenty minutes the meal will be cooked,’ he wrote. ‘Whereas a man acting without a system can waste an hour in pottering over smoky mulch.’

One of the most hair-raising chapters is titled ‘Pests of the Woods’. Among the most hardy of these are mosquitoes which, appear when the temperature is -75° Fahrenheit, in Verkhoyansk, the arctic pole in Siberia. ‘In Alaska,’ he wrote ‘all animals leave for the snowline as soon as the mosquitoes appear. Deer and moose are killed by mosquitoes, which settle on them in such amazing swarms that the unfortunate beasts succumb from literally having the blood sucked out of their bodies. The men who penetrate these regions become so unstrung from days and nights of continuous torment that they sometimes weep.’ After reading this I decided to give the polar regions a miss.

Under the calm gaze of Kephart, I could (with the help of the index) visualise myself crossing abysses and curing abscesses, cross-lining bees, making beds with boughs, removing broken axe-halves, dealing with copperhead snakes, and ingrowing toenails. Getting lost: in canebrakes, in flat woods, in hilly country, in overflow country, in a snowstorm, in thickets and in circles, tanning hides, making tea in a bark kettle and so on.

Getting lost was much worse than I imagined. ’A man is really lost when, suddenly (it is always suddenly) there comes to him the thudding consciousness that he cannot tell, to save his life, whether he should go north, east, south or west. This is an unpleasant plight to be in … Nervously he consults his compass, only to realise that it is no more service to him now than a brass button.’

This is a disturbing situation to be in, as I found lost on Dartmoor. You just needed to have Kephart with you.

With a new hairdo – not a success!

Wanda was more successful.

As Travel Editor of the Observer, engaged in a mineral water tasting.

Colleagues from Secker and Warburg, publishers. Centre Graham Greene; right David Holt, 1958.

At a party, London 1974 with Eamonn Andrews host of This is Your Life before I was enmeshed in the programme.

With Wanda at our house in Dorset

Of the many people and places I haven’t visited, I would most like to have seen the Great Pyramid before the Arabs stripped it of its white limestone casing, all twenty-three acres of it, and carted it away to build Cairo. And I would like to have seen the source of the Blue Nile. The first known Europeans to get to it were two Jesuit priests in around 1613, Father Lobo and Father Paez. Lobo described it as being ‘two springs … each about five and a half feet deep, a stone’s cast from one another’. A modest beginning for one of the more famous rivers of the world. And I would have liked to have seen Thomas Stevens lugging a penny farthing bicycle up through the gorges of the Pi-Kiang river in China on his way biking around the world in 1886. And I would have liked to have seen the route adopted by the Indian Secret Service agent, Hari Ram (fl 1891-1873) travelling down the Bhotia Khosi in Nepal. ‘At one place the river ran in a gigantic chasm and the path became so impracticable that it had to be supported on iron pegs driven into the vertical sides of the cliff, in no place more than eighteen inches wide and in some places no more than nine inches wide for a third of a mile along the face of the cliff some 1500 feet above the river, which could be seen roaring below in its narrow bed.’ The explorer, who had seen much difficult ground in the Himalayas, said he never in his life had met with anything to equal this stretch of path.

There is another compulsive traveller I would like to have seen in action, Alexander the Great, who had it pointed out to him by one of his generals, Coenus (a risky thing to do), that he, Alexander – above all others a successful man – should know when to stop. And Alexander stopped. And so should I know when to stop. So I’m stopping.

The end of the Road in Italy.