HYBRID ENTREPRENEURSHIP IN UNCERTAIN AND FLUCTUATING ENVIRONMENTS

GREENWEST and GREENSOUTH, our two research sites, were founded two years apart and were among the first green banks to be established in the United States. Both banks sought to establish the new form of green banking, to be comprised of organizations engaged in banking activities that aimed to both advance the cause of sustainability and make a financial profit. The visions of the early members of the senior leadership teams of the two organizations were remarkably similar. One cofounder of GREENWEST called himself an “innovative banker” whose goal was to get “exceptional returns.” Another cofounder stated that GREENWEST bank would be the first to focus on both “banking” and the promotion of “green and sustainable resources.” Similarly, the founder/CEO of GREENSOUTH called himself “a rabid environmentalist” but also “a rabid capitalist.” In both cases, founders and directors aspired to make a real impact on the environment and were excited about how their “business model” had the potential to “define the future of the U.S. banking industry.”

These “green” privately owned banks should not be confused with “state green banks,” other governmental state-level financial institutions that emerged later to provide low-cost financial services for clean or renewable energy projects. The first among those other institutions was Connecticut’s Clean Energy Finance and Investment Authority (CEFIA), established in 2011 to leverage millions of federal funding in support of state-level clean energy initiatives. Unlike those government institutions, GREENWEST and GREENSOUTH were “regular” privately owned local community banks.

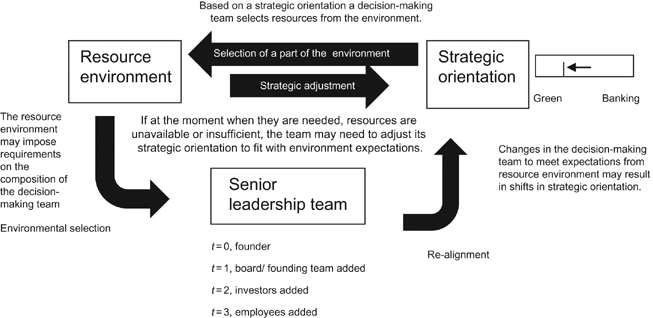

The founding process of GREENWEST and GREENSOUTH followed a startup process consisting of steps that are typical to the founding of a new bank. There are four sequential steps that correspond to the acquisition of critical tangible and intangible resources: (1) assembling a core founding group of directors with appropriate connections, legitimacy and skills; (2) obtaining regulatory approvals; (3) securing capital resources; and (4) facing the market for both employees and customers. This process is well-established and was closely followed by more than 100 new community banks per year in the years preceding our study (Almandoz, 2012). There is a “ready-to-wear” model (Battilana & Dorado, 2010), a well-defined formation process, and eager support from bank regulators, consultants and lawyers (DiMaggio & Powell, 1983) to assist founders in this endeavor.

GREENWEST’s Founding Process

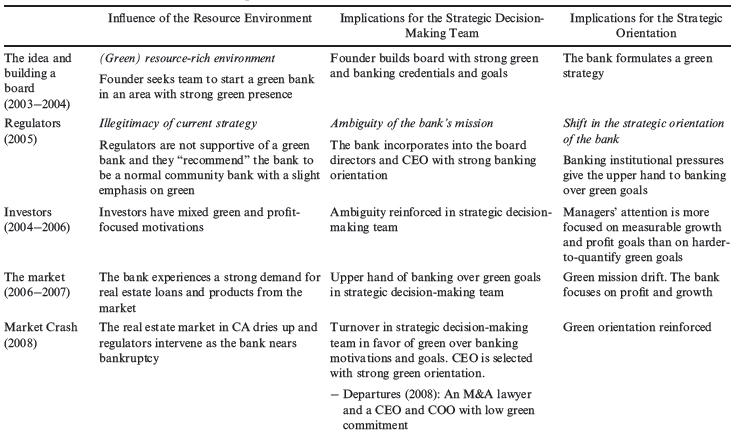

The timeline of GREENWEST’s founding is summarized in Table 2 from assembling a core founding group of directors (2003–2004), to obtaining regulatory approvals (2005), securing capital resources (2004–2006), and facing the market for employees and customers (2006–2007). Each of these steps entailed an encounter with GREENWEST’s resource environment, with resulting consequences for the composition of its senior leadership and strategic orientation.

Table 2. Impact of Resource Environment on GREENWEST.

Local Context and Founding Group

GREENWEST was established in a region of the United States that one executive referred to as “the Mecca of all things green.” In an organizational document explaining its initial strategy, GREENWEST specified that the area was chosen because of “the critical mass of clean businesses and sustainability focused organizations in the region” (page 2). The 15-page executive summary of the document provides abundant detail on the bank’s strategy to target green businesses, and people and organizations committed to sustainability. Ten different sectors are mentioned as potential clients of the bank – including organically and sustainably produced food, green buildings and green consumer products. Specific examples are mentioned of potential customers and their banking needs. The document lists 16 sample industry associations or cooperative organizations with whom the bank could partner and mentions that board members and organizers of the bank have existing relationships with 539 different organizations in the bank’s home region alone: 178 in clean energy, 184 in organic foods, and 177 in green buildings.

GREENWEST’s founding group was deeply embedded in green institutions, locally, nationally, and internationally, and included a broad base of directors with a strong commitment to, and affinity for, both financial and green logics, including renowned green activists and businesspeople. One of the bank founders had, years before, been instrumental in persuading large institutional investors in the region to invest in green enterprises. Others in the core group of founders had created organizations and investment funds to promote green entrepreneurship. The cofounders then hired a CEO to run the bank. (see Table 3 describing the backgrounds of board directors and organizers of the bank).

Table 3. Core Founding Group’s Involvement in Sustainability at GREENWEST.

• Cofounder of a group of business leaders advocating environmental goals |

• CEO of a social finance nonprofit focused on environmental sustainability |

• President of an organic and sustainable food product consulting firm and former president of the Organic Trade Association |

• President of a leading green building and energy efficiency company |

• Partner of venture capital fund focused on clean technology investments |

• President of a building and engineering firm focused on green and sustainable buildings |

• Director of a major private foundation with a strong focus on environmental sustainability |

• Director of an investment banking firm with a specialization in clean energy |

Interactions with Resource Environment

In its initial stages of development, the essential resources acquired by GREENWEST were largely controlled by actors embedded in the green logic. However, despite the strong green orientation of the core founding group of directors, GREENWEST’s strategic orientation became progressively more banking-oriented and less green. As one founding director explained, this shift to a banking orientation was heavily influenced by a decision to hire a CEO who was a seasoned banker, but did not have a strong commitment to sustainability. While the ideal candidate would have demonstrated operating experience within both the banking logic and the green logic, such a candidate proved impossible to find. The hire of a banking oriented CEO reinforced the banking logic, shifting the balance of representation of banking and green logics within senior leadership. (see Table 4 for detailed evidence about this period).

GREENWEST’s move toward the banking logic continued once it commenced operations. GREENWEST’s initial business plan, approved by regulators, projected a loan portfolio comprised of 50 percent real estate loans. Relative to loans made to clients in other sectors, these loans were typically not viewed as enacting the green logic, as GREENWEST borrowers rarely committed to build according to sustainable standards. However, growth in the local real estate market during the initial years of GREENWEST’s existence shifted available opportunities toward real estate. Although unanticipated, the board and management viewed the boom in real estate lending opportunities as the most promising opportunity to grow quickly and most profitably. As a result, GREENWEST’s proportion of real estate loans as a part of the overall portfolio was 65, 82, and 88 percent at the end of the first, second, and third years, respectively. So while the bank had opportunities to make loans to green customers, the growing attractiveness of the local real estate resulted in practices more consistent with the banking logic, especially the goal of rapid bank growth, and less consistent with the green logic. Thus the bank slowly drifted away from the green strategic orientation.

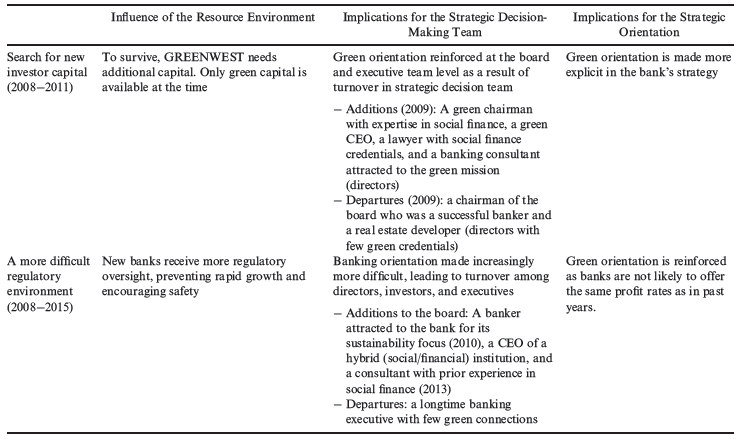

GREENWEST’s rapid growth was interrupted suddenly by the market crash in 2008, which caused the market for real estate loans to plummet. The result was a much less attractive real estate market and a dramatic turnover in the board of directors and executive team. As a member of the founding team and board mentioned, “The chairman of the board resigned and we really needed to make some changes with the management. So we basically reconstituted the board and hired a new CEO.” As it attempted to shift its strategy away from its failed real estate loans, the bank required new financing. During this period, it discovered that investment capital was only available within the green investing community, whose normative motivations for providing financing had persisted despite the crisis. The bank’s strategic orientation thus shifted back toward the green logic. This shift to the green logic and away from the banking logic was reinforced again when the regulatory environment after the crisis (2008–2011) resulted in more stringent regulatory constraints on banks’ growth and profitability targets. This shift in the strategic orientation of the bank was also accompanied by significant turnover in the senior leadership of the bank that resulted in a greater proportion of members representing the green logic.

In summary, GREENWEST was founded with a strong green orientation that progressively weakened through the course of the founding process as it was forced to seek resources from the banking sector and as it was tempted by opportunities for growth. But shifts in the resource environment as a result of the crisis led to a refocusing of the bank’s strategic orientation on green products and customers, which also corresponded to a re-shuffling of the bank’s investors and organizational members toward those motivated by the bank’s green orientation. Table 4 shows qualitative evidence from interviews and archival data that supports the story of how uncertain and fluctuating resource environments determined the composition of the decision-making team and the orientation of the bank’s strategy.

Table 4. Illustrations of the Impact of Resource Environment on GREENWEST.

The idea and building a board (2003–2004) |

The market was ideal for a new bank that could potentially make a difference in the banking sector. |

Founding member. We saw the need. There is a need to be a successful business in order to grow and generate resources to make a difference in the environment. |

|

Employee. I saw the opportunity to be on the cusp of something new, different and enduring. We would like that in 10 years everyone will be wondering, “Why weren’t we always banking like this?” |

|

Press release. We are the bank for people leading the way to a more sustainable world. We are a mission driven bank focused on sustainability; that means we work to have positive environmental and social impact, as well as make a profit, and we support businesses that do the same. |

|

Business Plan. The bank’s market [in the area], which is underserved by commercial banks currently operating in the local market and is also home to a thriving and highly connected network of rapidly growing clean businesses and leading sustainability focused organizations. |

|

Regulators (2005) |

Regulators pushed the bank to give more priority to banking goals and less to green goals |

Founding member. I think the regulators focus on risks, and not necessarily on the other issues that need to be addressed in society. So an idea that is new is sometimes challenging. If you focus on green business you are going to be too concentrated from a risk standpoint. So, [regulators] actually had a lot of input initially into how we evolved the business model. They were definitely the hardest ones to please. They actually said, “We want you to act as a community bank and serve the rest of the community as well.” That’s what they required us to do. |

|

Second CEO. While the idea of a green bank was highly important to the bank founders, the bank opened as a more general community bank that had a focus on green. There was a lack of clarity up front about what the green strategy was going to be. |

|

Investors (2004–2006) |

Investors focused the bank on banking goals |

Second CEO. There were two kinds of investors. The ‘fast banking’ investor was asking how fast can you grow? How high can your ROE be and how big an exit can we achieve by selling this bank in 10 years? And then there were ‘slow banking’ investors, who were in this for the long run and not looking for an exit strategy. |

|

The market (2006–2007) |

The market opened attractive opportunities for banking goals |

Second CEO. I would say that in the end the idea was never really clearly laid out. What did success look like? In the end, there were definitely competing goals [in the board]. The bank was formed to be green, but we wanted to grow as fast as we could and that means we could do a lot of non-green stuff in the interest of growth. |

|

Second chairman. When we were looking to hire a CEO it was hard. We couldn’t find any seasoned banker who was really interested in the mission. I could tell immediately that they were “Yeah, yeah, yeah, we are happy to do this green stuff,” but it was more like icing on the cake. You could just feel that they were not going to build a different kind of culture in the organization. |

|

Second chairman. We grew really, really quick and probably we made some mistakes in the early days by feeling that we needed to get to profitability very quickly, and therefore put a lot of loans on the books. So the bank got ahead of itself ….[At the end of the run, some founders] “were shocked that an important part of lending we were doing was not mission related.” |

|

Employee. Dollar signs and growth were more important than truly adhering to the [green] mission. |

|

Market Crash (2008) |

The market crash shrinks the resource environment and returns the bank to the original green mission for which there are still available pools of resources |

Second CEO. It is not about building for exit multiples. Growth and profitability are essential and important, but they are means-goals and not end-goals. The end-goal has to be building a sustainable community. |

|

Search for new investor capital (2008–2011) |

The reinforced green strategy of the bank limiting profit expectations changes the investor composition |

Second CEO. Some investors actually love what we are doing and a lot of them are doubling down. One 10-percent investor is going to become a 25-percent investor and a 1-percent is going to become a 10-percent investor. So we have some significant increases from existing investors as a result of this greater mission clarity. But there are others who are unhappy so I am connecting them with our market-maker and they want out. So there will be some shifting among those investors. |

|

A more difficult regulatory environment (2008–2015) |

Increasing regulatory oversight limiting growth |

Second CEO. Our IRR will get up to 10 percent and that’s probably the new normal for community banking |

GREENSOUTH’s Founding Process

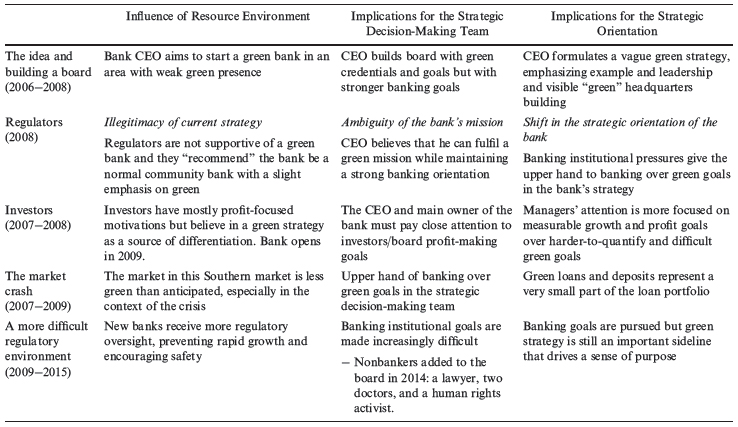

The timeline of GREENSOUTH’s founding is summarized in Table 5 from assembling a core founding group of directors (2006–2008), to obtaining regulatory approvals (2008), securing capital resources (2007–2008) and facing the market for employees and customers (2007–2009).

Table 5. Impact of Resource Environment on GREENSOUTH.

Local Context and Founding Group

GREENSOUTH began the process of opening a green bank one year after the founding of GREENWEST. In stark contrast to the Western state, the Southern state was viewed by some GREENSOUTH executives as “the land of the Neanderthal when it comes to sustainability,” In a standard document describing the bank’s strategy, GREENSOUTH provides far fewer details than GREENWEST regarding local connections with green organizations beyond the commitment and personal involvement of three board directors. One of them is an “internationally known spokesperson” for the environment; another is actively involved in 16 green associations, some local, some national, and some international; and the third, the main founder and CEO, has served as chairman for a political action committee advancing a green cause. Reflecting a perception that the bank’s focus on the sustainability would not be appreciated by regulators, GREENSOUTH does not emphasize its green mission in that official document.

Prior to founding GREENSOUTH, its CEO and founder had extensive experience as a banker. Confident because of his prior success in founding another bank, and inspired by the story of the founder of Patagonia, a prominent sustainable apparel company, he decided to start a values-driven bank that would combine his passions for banking and the environment. Based on these influences, he saw an opportunity to pair his professional skills and personal passions by launching a green bank in a region where he was born and had always lived. He hand-picked a core founding group from among friends and family and from business partners, some of whom had been directors of his prior bank’s board of directors. (See Table 6 describing the backgrounds on sustainability of board directors).

Table 6. Core Founding Group’s Involvement in Sustainability at GREENSOUTH.

• The CEO is Chairman of a political action committee to purchase and preserve public land. |

• A respected pastor, leader in a large evangelical community who has been named one of the top 15 religious environmental leaders worldwide. |

• A biologist and entrepreneur who started a local tissue laboratory and nursery specializing in the production of indoor tropicals and fruits and who is involved in national and international plant, foliage, nursery, and horticulture societies. |

Interactions with Resource Environment

Subsequent encounters with the resource environment had implications for the composition of the strategic decision-making team and the strategic orientation of the bank, which made the bank progressively more focused on its banking orientation. During the regulatory approval process, state banking regulators strongly suggested that the green logic should not be the main focus of the bank. Although the Founder/CEO sought investors oriented toward green issues, he was unable to find many such investors, and the bank took capital from investors who viewed the bank primarily as an opportunity to pursue financial returns. The unavailability of green investors became even more pronounced as the financial crisis deepened. Initially the founding group was aiming to require a minimum $100,000 investment per person but financial volatility led them to drop this minimum required investment to $60,000. An initial premise of GREENSOUTH’s strategy had been to use banking relationships as a way to encourage clients to make sustainability-oriented investments (i.e., in energy-efficient buildings); however, the crisis also limited the feasibility of such investments for GREENSOUTH’s clients.

Following the crisis, GREENSOUTH continued to pursue green opportunities, but primarily inside the organization. Opportunities to make loans to green companies and industries remained sparse, so the Founder/CEO focused on alternative means to advance the cause of sustainability. For instance, GREENSOUTH designed their internal operations to focus on sustainable principles such as operating without physical paper. GREENSOUTH also sought to use the bank as a platform for sustainability by drawing media attention to its sustainability mission.

Table 7 shows qualitative support for the evolution of GREENSOUTH’s strategic orientation as a result of an increasingly difficult resource environment forcing the bank to focus more on its banking orientation. Unlike the example of GREENWEST’s process of formation, there were no fluctuations in the relative abundance of resources aligned with the green and banking logics; there was only of a steady decline in both banking and green available resources.

Table 7. Illustrations of the Impact of Resource Environment on GREENSOUTH.

The idea and building a board (2006) |

A committed environmentalist and successful banker wants to make a difference in a territory that is not keen on sustainability |

Founder. I am a committed environmentalist, and I love banking. A rabid environmentalist and a rabid capitalist. So I was running with a friend, and we talked about it, and he said, “It’s your destiny. You need to merge the two things.” That’s the genesis of it. |

|

Founder. There were a handful of key people [on my previous bank board] that I wanted to have on the board who would be understanding and supportive of sustainability and there were plenty of others who would have liked to join me, and in fact some of them, once they found out, came to me and were irritated when I did not invite them, but I didn’t want anybody pushing back |

|

Executive. “This is the land of Neanderthals when it comes to sustainability.” |

|

Executive. We are very excited about this business model, and we believe it will define the future of the U.S. banking industry. To my knowledge, this will be the first bank of its kind to promote positive environmental and social responsibility while providing for increased profits for investors and clients. |

|

Regulators (2007) |

Regulators and consultants pushed the bank to give more priority to banking goals and less to green goals |

Founder. Regulators wanted to put us into the niche bank category [a bank serving a specialized and undiversified sector] and all our consultants and advisors said, “You don’t want to do that.” So, we said, “No, we are a community bank. We are not a niche bank.” I am not sure that was the right decision in the end, because we ended up having to straddle between what is seen as traditional community banking and what we were really doing in terms of our mission. |

|

Founder. At that point, I said, “Whoa, whoa, whoa! We’re a bank, we’re a bank, we’re a bank! If somebody comes in and they want to do a 5-acre slash-and-burn real estate development deal, we’re still going to do it because we have shareholder value to maintain. We’re going to try everything we can to teach them a better way, but we’re still going to do it. We won’t want to do it and we will kick and scream the whole time.” So finally I got them to back off. |

|

Investors (2007–2008) |

Investors had different motivations in mind when they joined the bank |

Founder. [Reported that an investor who agreed to invest $500,000 in the bank said]: “I don’t believe in this [green] stuff, but yours is the best marketing ploy I have ever seen.” |

|

The market crash (2008–2009) |

The market in this Southern market is less “green” than anticipated because of the crisis |

Founder. Initially, the emphasis on sustainability went very well. But as things began to change all that became almost a non-issue. Nobody wanted to hear it; no one wanted to talk about it, which was really disturbing to me, because that was the genesis of the whole idea. |

|

Founder. We opened at the peak of the great recession and nobody, absolutely nobody, has any interest in doing anything sustainable. People are having trouble and when they do they just want to be able to meet their mortgage payment, they don’t care about green. |

|

A more difficult regulatory environment (2008–2015) |

New banks receive more regulatory oversight, preventing rapid growth and encouraging safety and causing a renovated emphasis on the green mission |

Employee. I think it’s better for the bank to be here [rather than in the local environment of GREENWEST] because it has a chance to be the leader whereas GREENWEST may just be one of [many organizations] in [that area] doing this. Here GREENSOUTH has a chance to be on the leading edge to help promote what it feels strong about. It stands out more here. [So] in order to grow a movement this is a better place to do it. |

Long-Term Strategic Orientation

These two organizations, despite the similar intentions of their founders, ended up with significant differences in the degree to which goals connected with the green and banking institutional logics were realized in their strategies.

GREENWEST

GREENWEST emerged from the financial crisis operating with a strong green logic, despite its shift toward the banking logic prior to the crisis. The green strategy at GREENWEST focused on three aspects of its strategy. First, the bank committed to focusing client acquisition on companies already committed to sustainability, either because their business was in a green or sustainable sector, or because they made a clear commitment to operate in a sustainable fashion. As a consequence of its client selection, GREENWEST pursued modest growth and limited its own potential for profitability. Clients would be asked to take a survey every year and, based on the survey, they would be classified as either “learners,” “achievers,” “leaders,” or “champions.” The bank also developed toolkits with green recommendations and resources.

Second, bankers were trained to become trusted advisors on sustainable practices. The strategy involved helping clients become more environmentally sustainable and developing to that end a green expertise so that GREENWEST’s bankers could become trusted advisors, especially adept at helping customers “unlock the economic value of sustainability” through branding and marketing practices, hiring and retaining employees, cost savings, and access to meaningful networks of similarly committed organizations and individuals.

Third, the renewed alignment with the green strategy entailed presenting a quarterly sustainability report to the board of directors, including aggregate scores on sustainability. The board also planned to review the bank’s progress each year in fulfilling its green mission. To commit even more explicitly as a matter of governance to the green strategic orientation, the bank chose to become a B Corporation, joining other hybrid companies with both profit and nonprofit goals. Even though becoming a B Corporation currently had no legal consequence in the GREENWEST’s home state, it was a way to signal the organization’s commitment to a triple bottom line (return to shareholders, to employees, and to the environment). Bank investors were thus forewarned that maximizing value to shareholders was not the bank’s sole purpose or even its central purpose.

GREENSOUTH

GREENSOUTH did not commit itself to serving only customers committed to green causes, finding insufficient demand for green banking services, nor to make its bankers experts in sustainability. It also did not establish governance practices to measure the degree to which the bank was serving a green mission. GREENSOUTH’s strategic orientation was instead focused on internal operations rather than in its relationships with external stakeholders. First, they built a landmark headquarters building that received platinum LEED certification – the highest level. Living out their mission in the “land of the Neanderthals,” where green concerns were not legitimate involved, attracting considerable media attention. GREENSOUTH’s building served that purpose: it was built partly from recycled materials and had electric vehicle charging stations, larger windows to receive natural lighting, solar roof panels, and multiple other green and sustainable features.

Second, the bank operated sustainably, in a largely paperless fashion, and offered incentives to employees and customers who made investments in products and services aligned with green causes, such as purchasing energy-efficient cars, and remodeling homes to improve energy efficiency. Because of the crisis and the lack of local interest in sustainability, less than 10 percent out of $138 million in the loan portfolio four years after establishment was composed of green loans, including loans to construction, landscaping, farming, nursery, organic foods, solar energy, medical, and water distribution companies. Green deposits comprised less than two percent out of $171 million as of that time.

In sum, compared to that of GREENWEST, GREENSOUTH emphasized the green logic primarily through internal practices and its public example, rather than through monitoring the green practices of its clients. The green mission was promoted in the bank through personal influence, mostly that of the CEO. Some bankers told stories about the bank’s impact, one person at a time, leading to more hybrid cars purchased, and incandescent light bulbs being replaced by florescent or low-voltage bulbs. As one banker put it, “You can tell that you are having an impact and making a difference when a client tells you, without you asking, about a new sustainable practice he or she is following.”