A key element of the social construction of market categories is the existence of a shared symbol in the form of a label (Berger & Luckmann, 1966; Hsu & Hannan, 2005; Scott, 2001). Labels enable communication and activation of expectations and evaluation of products, even without full observation. However, at initial stages of social construction – such as when an organization claims a label that is otherwise novel within a proximate social space – there is limited social understanding associated with the use of the label as well as substantial uncertainty about what social understanding may develop (Kennedy, Lo, & Lounsbury, 2010). We ask which proximate social spaces are most relevant for category emergence, focusing on organizations’ choices to be early claimants of a label relative to incentives and risks that arise within differently defined social spaces.

We frame the logic by viewing market categories as socially constructed institutions that become understood through social interactions in proximate social spaces. Scholars commonly view institutions as providing social understanding (Scott, 1995) and legitimacy (DiMaggio & Powell, 1983) while offering taken-for-granted status in defining customary “ways of doing things” (Nelson, 2005, p. 127). Similarly, categories provide structure and facilitate interactions in the market by helping consumers determine the legitimacy of products based on how well they fit with the expectations and understanding of a category (Zuckerman, 1999). Viewing market categories as socially constructed institutions provides conceptual suggestions for how processes of label emergence may begin and which dimensions of social space will be relevant.

Because institutionalization of a market category requires establishing social understanding across actors, initiation of a process depends on the existence of a set of peers along with social interactions involving the peers and their products. Social interactions are likely to be concentrated in proximate social spaces because of limited time and attention, which may lead to local search by the focal organizations (Cyert & March, 1963; March & Simon, 1958). Further, proximate social space provides people with shared norms and culture, easing communication and interactions (DiMaggio & Powell, 1983; Scott, 2001). The result is that peer recognition and category emergence processes tend to occur within proximate social spaces.

While the argument for why proximate social space matters is intuitive, it is not obvious which means for delimiting social space is most relevant for category emergence, either theoretically or in particular contexts. Reflecting the nascent nature of this theory, we develop orienting propositions concerning strategic incentives and risks for organizations to be early claimants of a label for an emerging category. The first proposition focuses on the size of the peer group within an organization’s proximate social space. We then consider distinct characteristics of interactions in proximate social spaces defined by market segments or geography to develop a second orienting proposition; we expect the nature of and means for communicating in the face of deviation from existing norms will make early claims to a label more likely in proximate social spaces defined by geography than by market segment. The orienting propositions serve as the frame for empirical analysis of early labeling claims.

We examine the process of claiming labels for an emerging category in the context of a service in the U.S. nonprofit sector that is commonly referred to as fiscal sponsorship. Fiscal sponsorship is a service in which existing 501(c)3 nonprofit organizations serve as financial intermediaries, providing access to and accountability for tax-exempt sources of capital for entities that do not have tax-exempt status. Using archives of organizations’ homepages as well as data from Internal Revenue Service (IRS) information filings, we developed a longitudinal data set that associates organizations with proximate social spaces – defined by market segment (nonprofit mission, such as arts or health) and geography (metropolitan statistical area) – in which they may be likely to interact. We analyze the organizations’ choices to use the label “fiscal sponsor” on their homepage relative to characteristics of the organization and its environment. The analysis offers insights about the choice to be early claimants to a label within different definitions of proximate social space, thereby developing understanding of the dimensions of social space within which organizations act strategically during the early stages of category emergence.

This research contributes to the developing literature on the emergence of categories as part of the social construction of markets. We develop the conceptualization of categories as institutions and then use this logic to consider how category emergence processes are shaped by organizations’ strategic responses within their proximate social spaces. We demonstrate how the social environment creates incentives for an organization to take the risk of claiming a new label in a context of uncertainty about the potential for emergence of the market institution that they are trying to influence. Further, we highlight the importance of considering heterogeneous conceptions of social space, highlighting the role of proximate social spaces defined by market segment or geography in shaping strategic activity in the form of being an early claimant of a label for an emerging category and in responding to peers’ labeling claims.

EARLY CLAIMANTS TO LABELS IN PROXIMATE SOCIAL SPACE

Building on the concepts above, we develop two orienting propositions that emphasize the way that organizations assess the benefits and risks of strategically claiming new labels relative to their peers in proximate social space. Although current theory is not sufficiently robust to develop fine-grained hypotheses, the orienting propositions help guide the empirical investigation of how proximate social spaces relate to early labeling claims. The empirical investigation partly tests the base ideas and partly explores extensions of the conceptual base.

While the logic elaborated below focuses on the benefits and risks of being an early claimant of a label and how organizations respond, we do not suggest that this is the only step in the emergence process or that producing organizations are the only relevant actors. We focus on labels because of their importance as the symbols that name categories. However, for a category and label to emerge there must be a set of products to be categorized and peers producing those products. In focusing on label emergence, we assume that the relevant set of products and organizations already exist. Further, we assume that these products share sufficient numbers of attributes that if people (either those associated with peers or other actors) within their proximate social space are able to observe the products or interact with the peer organizations, there is a meaningful probability that the products may be viewed as similar to each other. We also recognize the possibility that early use of a label arises among external actors such as trade associations and government agencies; at some point, though, the organizations would be likely to respond and begin to claim the label as part of the category emergence process.

Benefits and Risks of Early Claiming of Labels: The Impact of the Size of the Peer Group

Products that are not socially understood risk being ignored by consumers or face higher costs because they require greater effort and energy to be understood (Zuckerman, 1999). Organizations that provide such products are likely to have an interest in cultivating understanding for what they do in order to reduce those risks and costs. As we discussed earlier, claiming a label is one action that organizations can take to influence how they and their products are perceived. However, the benefits and risks of claiming a label will differ when the claim is for a new label in the context of an emerging category. While use of a new label can become informative if other peers in the same proximate social space subsequently claim the same label, the understanding of that label is subject to the uncertainty of the social construction process, including the potential for negative valence (Kennedy et al., 2010). The question is what circumstances make the potential benefits of claiming a label and creating social understanding of an emergent category most salient and valuable.

We argue that the salience and potential value of claiming a new label for an emerging category relate positively to the number of peers within a proximate social space. When multiple organizations use the same label to refer to comparable products, repetition facilitates the process through which external actors such as customers come to understand the label as associated with shared attributes of those products and their salience as a possible category (Kennedy et al., 2010). This is similar to how firms’ identification of close competitors can facilitate external understanding and identification of a new category (Kennedy, 2008).

Further, once an organization has claimed a new label and gone through the process of explaining what it means to a variety of actors within a proximate social space, peers may find it less costly to use the same label. Peers may be able to take advantage of the nascent social understanding where their stakeholders overlap with those of the initial claimant by claiming that same label. Indeed, the opportunity for category emergence depends on the existence and recognition of peers, by the peers themselves and other stakeholders. Hence, organizations that want to create social understanding of what they do and recognize the potential for category emergence by recognizing peers within the social spaces they jointly inhabit may choose to participate in category emergence as early claimants of a label. Thus, early labeling claims are likely to be positively related to the size of the peer group within a proximate social space.

Benefits arising from collective or competitive mechanisms may drive organizations to be early claimants of a label relative to the peers in their shared proximate social spaces. From a collective perspective, organizations may recognize the opportunity to create a category and seek to induce social understanding of their product through the initial claims of a label for the category (Aldrich & Fiol, 1994; Navis & Glynn, 2010). From a competitive perspective, organizations may claim a new label with the goal of influencing the understanding that develops; organizations may try to create a strong association of a label with their particular attributes to ensure that as the label diffuses, their own product remains clearly within the emerging understanding of the category. This is a version of preemption, whereby the first organizations attempt to shape the understanding that develops (Lieberman & Montgomery, 1988; Mitchell, 1989). Either the collective or competitive motive may be sufficient to induce organizations to be an early claimant of a label if they believe that there is potential for category emergence within the proximate social space(s) where they interact.

Although organizations may benefit from claiming a new label, they also face risks due to uncertainty about if and what social understanding will develop for the label and category. The label may not diffuse, so that effort to claim a label is wasted. Even if diffusion does occur, there may be persistent ambiguity about the meaning of the label (Pontikes & Barnett, 2015). For example, if the products associated with the label are diverse, other actors might not recognize the similarities of the products and so social understanding of the category and label may not develop. In parallel, numerous labels may be used for comparable products, which may prevent people from recognizing the similarity of the products. Hence, social understanding may not develop, which will tend to have negative effects for products when consumers are market takers (Pontikes, 2012). Thus, variation in the labels used or the attributes of organizations and products associated with the label may prevent social understanding from developing. In turn, the lack of social understanding – whether due to limited diffusion or to ambiguity – may create confusion in the market and so constrain the success of the organization’s products.

Further, labels may become associated with negative valence (Kennedy et al., 2010). While negative valence could be limited to resistance to the label within the market (e.g., reactions from incumbents of related categories), it could be as severe as regulations prohibiting the product associated with the label (e.g., if perceived to be normatively abhorrent by dominant actors). An example is the current challenge facing app-based taxi companies such as Uber. Perception of the emerging category overall could also become negative, making not only the label but also the attributes of the emerging category subject to negative valence. Glynn and Marquis (2004) provide a relevant example in their study of how organizations changed their names after the dot.com bubble burst to disassociate from the negative valence of being an Internet-based business. The risks from negative valence depend on the possibility for extreme reactions, such as rapid change in the social or legal acceptability of the emergent category.

Just as the potential benefits from being an early claimant of a label are likely to correlate with the size of the peer group, potential risks also will tend to increase with the size of the peer group. When there are multiple products and peers, organizations can claim more different labels, which could undermine the opportunity for category emergence. Similarly, the more peers there are, the greater the likelihood that at least one will engage in deviant behavior that casts a negative shadow across the entire emerging category.

Nonetheless, the potential for category emergence does not exist for peers and products that exist as solo entrants. Taken-for-grantedness of a category based on habitualization and generalizations can only arise when there are multiple products across which commonalities can be identified. Further, the opportunity for recognizing peers and similar products increases when there are more of each within a proximate social space. This also extends to the potential for sufficient social understanding and cohesion among peers and their closest stakeholders such that there may be sanctioning within the group of social actors closest to the emerging category according to the developing norms and expectations. In this way, recognition and interaction not only enable development of social understanding but also the norms and sanctioning through which the peers may try to protect it. Thus, we expect that the potential for emergence of social understanding – including norms, sanctions, and expectations – is so strongly dependent on there being a peer group of some size that the benefits will tend to outweigh the risks when the peer group within a proximate social space is larger.

Our summary argument is that incentives to be early claimants of a label increase with the size of the peer group within a proximate social space. Peer density creates more interactions that increase the likelihood that any one peer recognizes the potential benefits of category emergence. Recognition of the potential for category emergence will relate to the choice an organization makes about claiming a label, whether motivated by competitive or cooperative dynamics. This logic leads to our first orienting proposition, which provides a baseline to explore how market segment and geography function as potentially relevant proximate social spaces.

Orienting proposition 1. The larger the peer group within a proximate social space, the greater the likelihood that a focal organization will be an early claimant of a label.

Relevant Proximate Social Space: Market Segment and/or Geography?

The argument so far focuses on the increased benefits of being an early claimant of a label when there are more peers within a proximate social space, which makes it more likely that people are exposed to and will develop understanding of the emerging category. However, differently defined proximate social spaces may differentially enable or inhibit these social processes. We now turn to the types of proximate social spaces in which these processes occur.

These arguments are premised on two assumptions. First, the product being brought into the market is sufficiently general that it has potential to be used across market segments and across geographies – for example, computers, telecommunications, and financial services. Second, we assume that given this level of generality, there is sufficient latent supply and demand within each proximate social space that there is potential for the set of peer organizations to succeed in creating a market category. Given these assumptions, we argue that some of the key distinctions between proximate social spaces that are defined by market segment and geography are factors affecting the ease with which people can interact in terms of the frequency, content, and opportunities for overcoming communication challenges.

Uncategorized products face difficulties because what they do and the value they provide are not taken for granted nor likely to be obvious, in part because there will often be conflict with existing expectations and beliefs about the market by at least some potential stakeholders (Rao, Monin, & Durand, 2003). While we have already discussed how the socio-cognitive perception of the potential category requires a set of products and peer organizations, peer organizations are not the only actors that matter for the emergence process. Organizations need to identify actors throughout the value chain, converting potential stakeholders into realized stakeholders who have sufficient understanding of the product to value it. This process is likely to depend on the frequency and breadth of interactions as well as the means for communicating; these factors may differ with the distinct dimensions for defining proximate social spaces.

Table 2 compares proximate social spaces defined by geography and market segment. The comparisons relate to the ease of interactions that may help either reach potential stakeholders or convert actors identified as potential stakeholders who may in turn become sources of information about the uncategorized product within the market. Identifying and reaching potential stakeholders will relate to the frequency and breadth of interactions, particularly when it is not clear who one might be searching for because of the latent nature of demand and supply of an uncategorized product. Further, the availability of diverse means of communication and the constraint from norms within the shared space will be important for the conversion of latent stakeholders. We initially consider market segment and geography as distinct dimensions for defining proximate social spaces.

Table 2. Factors That Vary between Proximate Social Spaces Defined by Market Segment and Geography and Their Anticipated Sign on the Effects on Social Interactions and Communication Patterns.

Colocation By |

Market Segment |

Geography |

Frequency of interactions |

|

+ |

Quality of interactions (means for conveying information such as body language, use of objects) |

|

+ |

Diversity of interactions |

|

+ |

Lower risks from interactions (less deviation from industry norms; fewer competitive spillovers) |

|

+ |

Depth of interactions (shared language and norms from institutions in which colocated) |

+ |

|

Geographic proximate social spaces offer frequency, quality, and diversity of interactions. Studies of regional clusters and agglomeration (Alcácer & Chung, 2007, 2014; Saxenian, 1996) suggest that geographic closeness facilitates identifying and connecting with stakeholders because it is easier to interact frequently via in-person interactions, whether by chance or intention. Personal interactions facilitate high-quality communication. In-person interactions allow people to use physical objects and gestures as part of their communication toolkits, which may facilitate their ability to convey information that is otherwise difficult for the receiver to understand (e.g., making abstract concepts more concrete through demonstration). Because in-person interactions tend to be more frequent among people who are physically colocated, we expect that this should be more relevant within geographic proximate social spaces. In parallel, the diversity of multiple market segments represented within a geographic space may make people more willing to try different narratives or framings as they search for common ground (Kaplan, 2008). These benefits will facilitate overcoming communication challenges that arise when exchange interactions lack preexisting social understanding.

By contrast, interactions among actors who operate in a common market segment may facilitate deep engagements, reflecting shared understandings about customers, suppliers, regulators, and other relevant actors. However, market segment interactions are more likely to be oriented around formal events such as industry conferences and the use of tools such as directories for purposive interactions with specific individuals, especially for actors who are not also colocated geographically. These needs will often limit at least the frequency and diversity of interactions and may inhibit the quality of interactions if there is limited time for engagement.

Moreover, deep interactions with actors within market segments may be most valuable once one knows what one is looking for. By contrast, early in coming to market, organizations are likely to focus on identifying exchange partners, suppliers, and customers. In these circumstances, chance interactions and stakeholder diversity may be particularly valuable. Geographic proximate social spaces will tend to facilitate these types of unplanned interactions, such as run-ins at a local coffee shop or grocery store or while picking up a child from school.

The risks also will vary across market segment and geography. Interactions that deviate from the existing norms of the proximate social space in which the interactions occur may provoke punishment by other actors within that space. Interactions about market-based exchanges, such as during the emergence process for a market category, will have particularly salient norms – that also are more likely to be violated – when the actors are in a proximate social space defined by market segment. Market segments share similar suppliers and consumers, so that problems that arise from a problematic attempt to claim a new label will be highly visible to market segment peers, who fear contamination of their own commercialization efforts. They may be particularly likely to draw on their social networks and other contacts to sanction labeling attempts that they view as improper, such as by fostering regulatory opposition.

Clearly, geographical patterns of interaction also pose risks due to deviation, particularly as the actors often engage in similar social circles. However, to the extent that actors within the same geography operate in different market segments, they may be functioning under different norms of market interaction. As such, there may be greater willingness to allow market-oriented experimentation in norms and language without attempting to impose sanctions. This suggests that the risks from deviating from existing norms of the proximate social space will be lesser in geographic proximate social space than that defined by market segment.

Further, the process of publicly claiming a label raises risks of losing valuable information to a competitor. Such risks may be particularly high early in the development of a market category, while norms and market positions specific to the emerging category are in substantial flux. These risks will be highest in the case of market segments, where peers tend to be rivals. By contrast, the risks of information loss may be lower in geographic proximate social space, owing to lesser direct rivalry and greater diversity in the stakeholder base.

The logic above suggests that early-stage emergence processes will be more likely to occur when proximate social space is defined by geography rather than market segment. Because random interactions are more likely, it may be easier to identify latent stakeholders within geographic proximate social spaces. Further, conversion should be easier within geographic proximate social spaces because of opportunities for overcoming communication barriers and lower risk of violating norms shared by the organization and potential stakeholders.

Orienting proposition 2. The size of the peer group within a geographic proximate social space will have a stronger relationship with an organization’s choice to be an early claimant than the size of the peer group within a market segment proximate social space.

Clearly, organizations exist in proximate social spaces defined along different dimensions concurrently, such as the presence of market segment peers within a geographic region. Hence, the intersection of market segment and geography also might define proximate social spaces. However, the causality within such jointly defined proximate social space is more complex than we are willing to theorize at this point. The joint space has the benefits of geographical proximity in the form of interconnected networks and market segments in the form of shared backgrounds that will provide shared language and practices. Within the intersection, interaction may be more likely and more in-depth, and thus increase the likelihood of opportunity recognition while also reducing communication costs. However, the duality also generates increasing constraints because of the depth of existing norms and expectations. When colocation is entirely based on geography, organizations and stakeholders may have some lenience due to their variation across market segments; by contrast, when proximate social space is defined by the intersection of geography and market segment, there may be much greater constraint because of expectations from both individual dimensions and their union, particularly if patterns of interaction among actors inhabiting that space predate the process of category emergence. This could increase the risk of penalty due to deviation from existing social norms. Hence, we will conduct exploratory analysis with proximate social spaces defined by the duality of market segment and geography.

Moreover, organizations will often prioritize different social spaces at different times or for different goals. For the purpose of identifying how interactions vary in differently defined proximate social spaces, it is useful to think of organizations at extremes: those that interact primarily within their geographic proximate social space and those that interact primarily within their market segment proximate social space. The argument so far applies to patterns of prioritization of social spaces, such that geography may be particularly salient in interactions even as organizations retain connections within their market segment, and vice versa.

REFERENCES

Alcácer, J., & Chung, W. (2007). Location strategies and knowledge spillovers. Management Science, 53(5), 760–776.

Alcácer, J., & Chung, W. (2014). Location strategies for agglomeration economies. Strategic Management Journal, 35(12), 1749–1761.

Aldrich, H. E., & Fiol, C. M. (1994). Fools rush in? The institutional context of industry creation. Academy of Management Review, 19(4), 645–670.

Alexy, O., & George, G. (2013). Category divergence, straddling, and currency: Open innovation and the legitimation of illegitimate categories. Journal of Management Studies, 50(2), 173–203.

Berger, P., & Luckmann, T. (1966). The social construction of reality. Garden City, NY: Doubleday.

Carroll, G. R., & Swaminathan, A. (2000). Why the microbrewery movement? Organizational dynamics of resource partitioning in the U.S. brewing industry. American Journal of Sociology, 106(3), 715–762.

Chakrabarti, A., & Mitchell, W. (2013). The persistent effect of geographic distance in acquisition target selection. Organization Science, 24(6), 1805–1826.

Chakrabarti, A., & Mitchell, W. (2016). The role of geographic distance in completing related acquisitions: Evidence from U.S. chemical manufacturers. Strategic Management Journal, 37(4), 673–694.

Chakrabarti, A., Vidal, E., & Mitchell, W. (2011). Business transformation in heterogeneous environments: The impact of market development and firm strength on retrenchment and growth reconfiguration. Global Strategy Journal, 1(1–2), 6–26.

Chown, J. D., & Liu, C. C. (2015). Geography and power in an organizational forum: Evidence from the U.S. Senate Chamber. Strategic Management Journal, 36(2), 177–196.

Colvin, G. L., & Link, G. (1993). Fiscal sponsorship: 6 ways to do it right. San Francisco, CA: Study Center Press.

Cyert, R. M., & March, J. G. (1963). A behavioral theory of the firm. Upper Saddle River, NJ: Prentice Hall.

DiMaggio, P. J., & Powell, W. W. (1983). The iron cage revisited: Institutional isomorphism and collective rationality in organizational fields. American Sociological Review, 48(2), 147–160.

Durand, R., & Paolella, L. (2013). Category stretching: Reorienting research on categories in strategy, entrepreneurship, and organization theory. Journal of Management Studies, 50(6), 1100–1123.

Feld, S., & Grofman, B. (2009). Homophily and the focused organization of ties. In P. Hedström & P. Bearman (Eds.), The Oxford handbook of analytical sociology (pp. 521–543). Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Fosfuri, A., Lanzolla, G., & Suarez, F. F. (2013). Entry-timing strategies: The road ahead. Long Range Planning, 46(4–5), 300–311.

Glynn, M. A., & Marquis, C. (2004). When good names go bad: Symbolic illegitimacy in organizations. In C. Johnson (Ed.). Legitimacy processes in organizations (Vol 22, pp. 147–170). Research in the Sociology of Organizations. Bingley, UK: Emerald Group Publishing Limited.

Glynn, M. A., & Navis, C. (2013). Categories, identities, and cultural classification: Moving beyond a model of categorical constraint. Journal of Management Studies, 50(6), 1124–1137.

Granqvist, N., Grodal, S., & Woolley, J. L. (2013). Hedging your bets: Explaining executives’ market labeling strategies in nanotechnology. Organization Science, 24(2), 395–413.

Greve, H. R. (1998). Managerial cognition and the mimetic adoption of market positions: What you see is what you do. Strategic Management Journal, 19(10), 967–988.

Greve, H. R., & Rao, H. (2014). History and the present: Institutional legacies in communities of organizations. Research in Organizational Behavior, 34, 27–41.

Hannan, M. T., Pólos, L., & Carroll, G. R. (2007). Logics of organization theory: Audiences, codes, and ecologies. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

Haveman, H. A. (1993). Follow the leader: Mimetic isomorphism and entry into new markets. Administrative Science Quarterly, 38(4), 593–627.

Hsu, G., & Grodal, S. (2015). Category taken-for-grantedness as a strategic opportunity: The case of light cigarettes, 1964 to 1993. American Sociological Review, 80(1), 28–62.

Hsu, G., & Hannan, M. T. (2005). Identities, genres, and organizational forms. Organization Science, 16(5), 474–490.

Kaplan, S. (2008). Framing contests: Strategy making under uncertainty. Organization Science, 19(5), 729–752.

Kaplan, S., & Vakili, K. (2015). The double-edged sword of recombination in breakthrough innovation. Strategic Management Journal, 36(10): 1435–1457.

Kennedy, M. T. (2008). Getting counted: Markets, media, and reality. American Sociological Review, 73(2), 270–295.

Kennedy, M. T., & Fiss, P. C. (2013). An ontological turn in categories research: From standards of legitimacy to evidence of actuality. Journal of Management Studies, 50(6), 1138–1154.

Kennedy, M. T., Lo, J. (Yu-Chieh), & Lounsbury, M. (2010). Category currency: The changing value of conformity as a function of ongoing meaning construction. In G. Hsu, G. Negro, & Ö. Koçak (Eds.), Categories in markets: Origins and evolution (Vol. 31, pp. 369–397). Research in the Sociology of Organizations. Bingley, UK: Emerald Group Publishing Limited.

Koçak, Ö., Hannan, M. T., & Hsu, G. (2014). Emergence of market orders: Audience interaction and vanguard influence. Organization Studies, 35(5), 765–790.

Kossinets, G., & Watts, D. J. (2009). Origins of homophily in an evolving social network1. American Journal of Sociology, 115(2), 405–450.

Kovács, B., & Hannan, M. T. (2010). The consequences of category spanning depend on contrast. In G. Hsu, G. Negro, & Ö. Koçak (Eds.), Categories in markets: Origins and evolution (Vol. 31, pp. 175–201). Research in the Sociology of Organizations. Bingley, UK: Emerald Group Publishing Limited.

Kovacs, B., & Johnson, R. (2014). Contrasting alternative explanations for the consequences of category spanning: A study of restaurant reviews and menus in San Francisco. Strategic Organization, 12(1), 7–37.

Leung, M., & Sharkey, A. (2014). Out of sight, out of mind? Evidence of perceptual factors in the multiple-category discount. Organization Science, 25(1), 171–184.

Lieberman, M. B., & Montgomery, D. B. (1988). First-mover advantages. Strategic Management Journal, 9(S1), 41–58.

March, J. G., & Simon, H. A. (1958). Organizations. New York, NY: Wiley.

Marquis, C. (2003). The pressure of the past: Network imprinting in intercorporate communities. Administrative Science Quarterly, 48(4), 655–689.

Marquis, C., & Battilana, J. (2009). Acting globally but thinking locally? The enduring influence of local communities on organizations. Research in Organizational Behavior, 29, 283–302.

Marquis, C., Davis, G. F., & Glynn, M. A. (2013). Golfing alone? Corporations, elites, and nonprofit growth in 100 American communities. Organization Science, 24(1), 39–57.

Marquis, C., & Lounsbury, M. (2007). Vive la résistance: Competing logics and the consolidation of U.S. community banking. Academy of Management Journal, 50(4), 799–820.

McPherson, M. (1983). An ecology of affiliation. American Sociological Review, 48(4), 519–532.

Meyer, J. W., & Rowan, B. (1977). Institutionalized organizations: Formal structure as myth and ceremony. American Journal of Sociology, 83(2), 340–363.

Mitchell, W. (1989). Whether and when? Probability and timing of incumbents’ entry into emerging industrial subfields. Administrative Science Quarterly, 34(2), 208–230.

Navis, C., & Glynn, M. A. (2010). How new market categories emerge: Temporal dynamics of legitimacy, identity, and entrepreneurship in satellite radio, 1990–2005. Administrative Science Quarterly, 55(3), 439–471.

Nelson, R. R. (2005). Technology, institutions, and economic growth. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Phillips, N., Lawrence, T. B., & Hardy, C. (2004). Discourse and institutions. Academy of Management Review, 29(4), 635–652.

Pontikes, E. G. (2012). Two sides of the same coin: How ambiguous classification affects multiple audiences’ evaluations. Administrative Science Quarterly, 57(1), 81–118.

Pontikes, E. G., & Barnett, W. P. (2015). The persistence of lenient market labels. Organization Science, 26(5), 1415–1431

Pontikes, E. G., & Hannan, M. (2014). An ecology of social categories. Sociological Science, 1, 311–343.

Porac, J. F., Thomas, H., & Baden-Fuller, C. (2011). Competitive groups as cognitive communities: The case of Scottish knitwear manufacturers revisited. Journal of Management Studies, 48(3), 646–664.

Prottas, J. (2013). How do funders understand fiscal sponsorship? National Network of Fiscal Sponsors Annual Meeting. Boston.

Rao, H., Monin, P., & Durand, R. (2003). Institutional change in Toque Ville: Nouvelle cuisine as an identity movement in French gastronomy. American Journal of Sociology, 108(4), 795–843.

Rosa, J. A., Porac, J. F., Runser-Spanjol, J., & Saxon, M. S. (1999). Sociocognitive dynamics in a product market. Journal of Marketing, 63, 64–77.

Saxenian, A. (1996). Inside-out: Regional networks and industrial adaptation in Silicon Valley and Route 128. Cityscape, 2(2), 41–60.

Scott, W. R. (1995). Institutions and organizations. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

Scott, W. R. (2001). Institutions and organizations. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

Sorenson, O., & Stuart, T. E. (2001). Syndication networks and the spatial distribution of venture capital investments. American Journal of Sociology, 106(6), 1546–1588.

Vergne, J.-P., & Wry, T. (2014). Categorizing categorization research: Review, integration, and future directions. Journal of Management Studies, 51(1), 56–94.

Wry, T., Greenwood, R., Jennings, P. D., & Lounsbury, M. (2010). Institutional sources of technological knowledge: A community perspective on nanotechnology emergence. In N. Phillips, G. Sewell, & D. Griffiths (Eds.), Technology and organization: essays in honour of Joan Woodward. Research in the Sociology of Organizations (Vol. 29, pp. 149–176). Bingley: Emerald Group Publishing.

Wry, T., Lounsbury, M., & Glynn, M. A. (2011). Legitimating nascent collective identities: Coordinating cultural entrepreneurship. Organization Science, 22(2), 449–463.

Zuckerman, E. W. (1999). The categorical imperative: Securities analysts and the illegitimacy discount. American Journal of Sociology, 104(5), 1398–1438.

APPENDIX A: ANALYSIS OF POTENTIAL FOR SURVIVOR BIAS

The earliest known list that attempts to identify the population of fiscal sponsors is from 2005 to 2006. However, because our interest is in the beginning of the label emergence process, when we initially began examining the website archives of these organizations we realized that there were instances of use of the fiscal sponsor label on some of their homepages that predated 2005. Building our data set going back all the way to the earliest observations is in keeping with the theoretical process of interest, but increases concerns about survivor bias. In particular, the concern is that proximate social spaces that have low density of peers identified might be due to factors in those proximate social spaces that make them inhospitable to these types of organizations, and so the low density may be an outcome of a process which leads to closures of organizations that thus should have been included in our data set, but were not because they were no longer operating in 2005.

We performed supplementary data collection and analysis to assess this risk. Because the primary concern is that survivor bias is inappropriately inflating our results, we focus our supplementary analysis on geographically defined social spaces, as this is the set of analyses in which we are most concerned about overestimating coefficients since these are the analyses that resulted in significant results.

For all of the MSAs (and where missing, the county codes in keeping with the data construction for our sample) in our sample at any point in time, we collected data on the number of organizations that were listed in the IRS data files and then calculated the percent change relative to key thresholds. Because we have organizations that entered the sample during the years of observation, we segmented this analysis based on the year that organizations incorporated with the IRS and calculated the percent change within those groups of organizations. While the IRS has historically removed organizations from their data files when they know that they closed or went out of business, organizations that were inactive were not historically removed. This was true until 2011, at which point thousands of organizations had their nonprofit status revoked, and were removed from these data files. Because of this, we calculate the percent change in the number of organizations by geography and incorporation year between both the time of incorporation and 2005 as well as between 2010 and 2011.

Because IRS data are collected and compiled throughout the year, and with some leeway, we use data files from the year after the year of interest for the first set of calculations, which can be thought of as the active changes to incorporated nonprofits. Table A1 explains the years of data collection for t0, whereas t1 data was all from 2006. The later data, which can be thought of as the inactive changes to incorporation status all use data from 2010 and 2011 to assess the changes, which are again calculated by geography and incorporation year. The percent change is calculated such that a decrease in the number of organizations in a geography with a particular incorporation date is positive:

In correlating these change variables with the proportion of organizations within a geography that are identified as peers, a positive correlation means that there is a relationship such that decreasing organizations in the MSA are related to an increase in the relative number of peers. A positive correlation between the change variables and the number of registered organizations means that there is a relationship between a decrease in the number of organizations founded at a particular point in time and the total population of nonprofits in that same geography. And a positive correlation between the change variables and the number of peers in an MSA demonstrates that regions that exhibit greater loss of organizations from those particular points in time are not those which have fewer peers in later years. Thus, positive correlations indicate that there should not be concern about the effects of survivor bias based on the distribution of closures across geographies, which is the closest we can get to assessing the possibility of specific dynamics for practitioners of fiscal sponsorship without actually knowing the population of fiscal sponsors as they existed at those points in time.

Table A1 presents the correlations between the change variables and the focal variables from our analysis. It demonstrates that there is little need to be concerned about survivor bias based on this analysis. Even for the correlation that would be of most concern at −0.19, this appears to be attributable to the fact that even though it is positively correlated with both the denominator and numerator, the correlation is larger with the denominator. We replicate these correlations using data from 2006 because of the timing of the list creation. We also replicated these general patterns both including and excluding geographical regions that had problematic percent changes (they were less than −1), which either reflected changes to how the IRS was defining the geographical areas or that there were unusually large movements between MSAs.

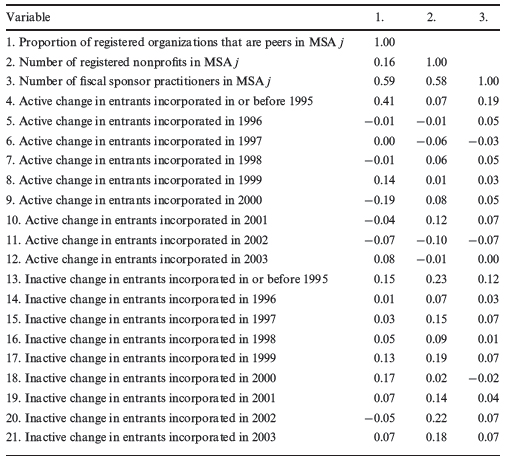

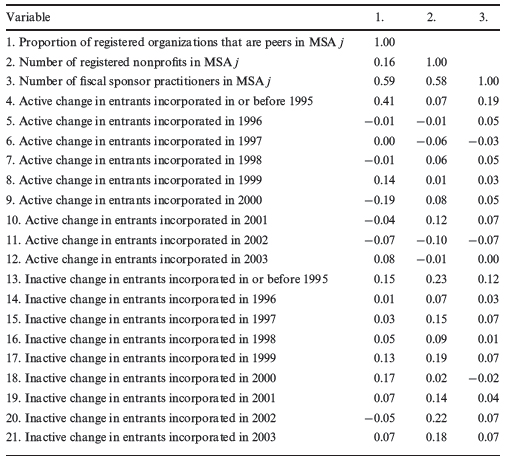

Table A1. Correlations between Change Variables and Conceptual Variable and Its Components.

APPENDIX B: DESCRIPTIVE STATISTICS

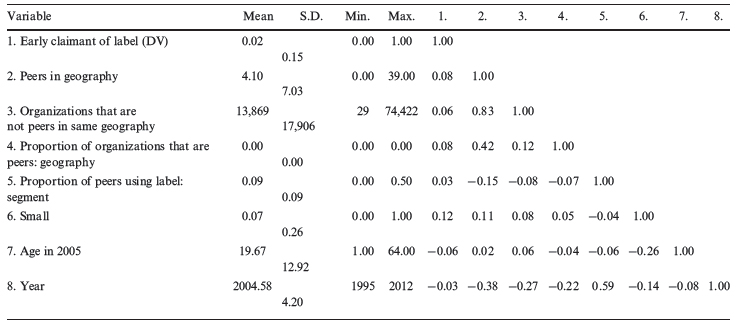

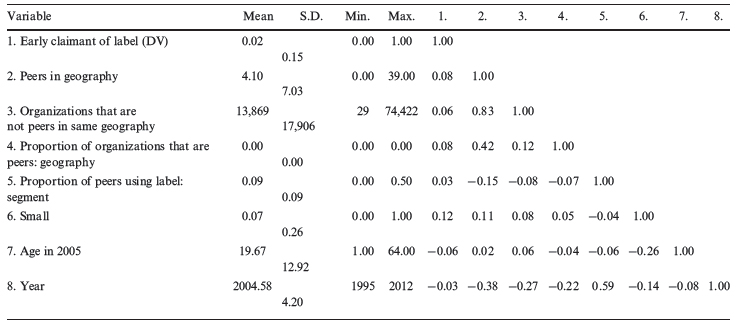

Table B1. Summary Statistics for Sub-Sample Based on Market Segment (478 Cases).

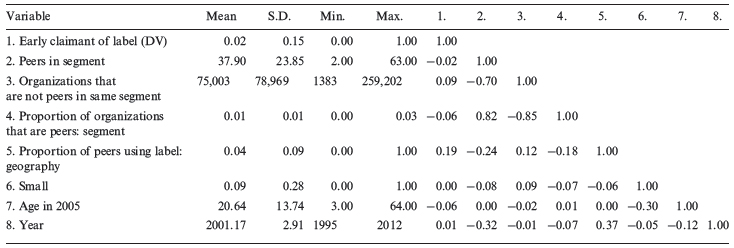

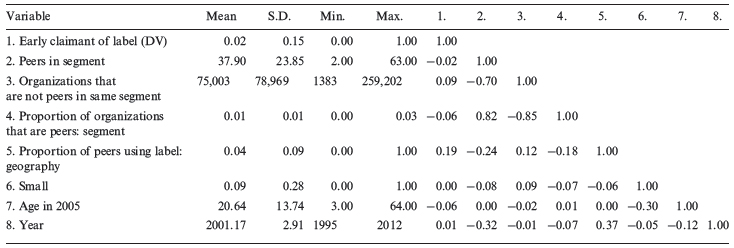

Table B2. Summary Statistics for Sub-Sample Based on Geography (1,550 cases).