ASSEMBLING A FIELD INTO PLACE: SMART-CITY DEVELOPMENT IN JAPAN

Roy A. Nyberg and Masaru Yarime

ABSTRACT

We examine the concept of ‘organisational fields’, a notion employed frequently, but at times with inconsistency, to describe supra-industrial conglomerations of organisations with a mutual interest. We find this concept analytically useful in today’s world of rapid technological change and of organisations searching for business across industry boundaries. With our study of smart-city development in Japan, we provide an alternative theory to the predominant socio-cognitive explanations of how organisational fields emerge. Based on our empirical case, the drivers for the early development of an organisational field are concrete organisational actions to assemble the tangible objects of the new field.

Keywords: Organisational fields; emergence; material action; commitment; information technology; smart city

INTRODUCTION

The concept of organisational fields has been in frequent use in organisational theory literature since the seminal DiMaggio and Powell (1983) article on isomorphism and collective rationality in organisational fields. DiMaggio and Powell noted that field perspective is useful as it directs our attention to the ‘totality of relevant actors’ (p. 148). For them, these actors are neither merely the competing firms of one industry nor only those belonging to one network, but who across industries may have a common interest (Davis & Marquis, 2005). While this concept has been employed also in studies with relatively few types of organisations (Zietsma & Lawrence, 2010), its real usefulness comes from the implicit recognition that to understand phenomena about change in complex societies requires usually a broader view than merely industry level analysis. When feasible, examining a higher number of types of organisations is preferable, as it will enable a more nuanced analysis of field development.

Organisational fields are evolving entities that are different at different times. Scholars have noted that most of prior work on institutional processes has focused on mature organisational fields (Greenwood, Suddaby, & Hinings, 2002; Lounsbury, 2002), even though it is clear that plenty of effort to create new institutions takes place at the emergence stage of field development (DiMaggio, 1991; Garud, Jain, & Kumaraswamy, 2002; Lawrence, 1999; Maguire, Hardy, & Lawrence, 2004). To study this temporal phase is not justified only because we know less about these ‘transitional periods’ (Lounsbury & Crumley, 2007, p. 994), but it has also been argued that this initial period in the development of fields has often turned out to be fundamentally important to explain how new practices emerge (Furnari, 2014). Several authors have suggested that organisations are likely to gain considerable advantage and subsequent success from being actively involved in the early construction efforts of these emerging fields (Garud et al., 2002; Leblebici, Salancik, Copay, & King, 1991; Maguire et al., 2004). Thus, while existing fields are important to study, investigating how fields are created at the ‘early moments’ stage may provide particularly valuable insights about the nature of fields overall.

In this article we explore this nature of organisational fields with evidence from an empirical case that is at this ‘early moments’ stage. Our case is that of ‘smart city’ development in Japan. While there is no universally recognised definition for the term ‘smart city’ (Hollands, 2008; Neirotti, De Marco, Cagliano, Mangano, and Scorrano, 2014; Tranos & Gertner, 2012), the involvement of information and communication technologies is one of the more common characteristics cited in recent scholarly work on this topic (Angelidou, 2014; Bianchini & Avila, 2014; Bourmpos, Argyris, & Syvridis, 2014). Our working definition of ‘smart city’ has been: The objective to use data technologies in urban utility services, by which we mean primarily energy, water, waste and transport services. Our study has had two levels of inquiry: at a more detailed level we have examined the efforts to implement smart-city solutions in these areas. At a broader level our study has explored how disparate activity, actors, ideas and technologies are being brought together into a distinct and common entity, an organisational field.

We argue in this article that organisations bring to life organisational fields by their concrete, material efforts of assembling their solutions into place. This stands in contrast with the predominant explanation that organisational fields emerge through socio-cognitive effects. We describe how organisations implement smart-city solutions by assembly type of efforts, by combining concrete, material elements new and old to create new ways of using urban services. In reference to the idea of assembly work, we note Levi-Strauss’ concept of ‘bricolage’ (1967, in Garud & Karnøe, 2003) to contrast our argument with some of the similar claims in the literature. The concrete, material assembly efforts display organisations’ more definitive commitment to field development, which we suggest will result in a more enduring impact. Our contribution is thus to provide a complement to the socio-cognitive type of efforts as an explanation for field development, in particular for the ‘early moments’ stage.

While our ultimate aim is to make a theoretical contribution, we also want to further matters of practice by making a point about vocabulary. Recent theoretical work has shown how different uses of language may impact institutional change (Suddaby, 2010). We supplement this view about the linguistic impact by making a note of caution in the interest of semantic accuracy. It has been common in this empirical area, equally in public as well as in scholarly discourse, to refer to the term ‘smart cities’, but we find this usage unhelpful. First, in the absence of a universally agreed definition for a ‘smart city’, references that imply a limited set of such cities are without foundation. Second, when organisations pursue projects in this area, they are not creating entire cities (despite the ambitions, the smart-city projects of New Songdo in Korea and Maasdar in Abu Dhabi included) but rather are implementing distinct technology solutions. At most, smart-city development is about creating small communities that contain technical solutions that we refer to as ‘smart-city solutions’. As a result, we think it more accurate to employ this concept as an adjective, as in ‘smart-city solution’, which implies this implementation of technology.

THEORETICAL CONTEXT

In this article we intend to expand the concept of ‘organisational field’, which has been one of those ideas that are more frequently employed than they are actually explained. Those that have sought to theorise this concept have provided a number of useful perspectives. Yet, most of them are based on abstract theorising, and in work that is based on empirical data the authors have provided little insight about the nature of organisational fields. In particular, the question of how fields are formed is important, and the one we focus on here. For our purposes, it is relevant to present the main lines of argument about how fields are formed, before we discuss a different conceptualisation based on our empirical case. We see that there are two of these lines, one emphasising the social engagement to create fields, and another that highlights the development of mutual cognition. After we discuss the definition of this concept and the number of organisations in a field, we will turn to these two lines of argument about the formation of fields. As we noted in the introduction, we will later contrast these socio-cognitive explanations with our own insight that at ‘early moments’ organisational fields are built with concrete, material efforts.

Definition of the Concept ‘Organisational Fields’ and the Issue of Participation Numbers

The definition of fields in the sense of organisational interrelations gained its most prominent grounding in the work of DiMaggio and Powell (1983), who set the stage for the use of this concept. The most frequently cited part of their definition of fields reads:

By organisational field we mean those organisations that, in the aggregate, constitute a recognized area of institutional life: key suppliers, resource and product consumers, regulatory agencies and other organizations that produce similar services or products. (1983, p. 148)

In other words, organisational fields typically consist of any sets of organisations that due to their similar interest could be considered as connected and worth studying as a group. Such groups could consist of different types of firms, government agencies, professional and trade associations as well as different types of special interest groups (Scott, 2001). This statement presents one significant part of the definition of organisational fields, and it is perhaps its relative clarity that has made it so common as a quotation. It highlights that some phenomena are sensible to analyse more broadly than industry. We briefly address this issue of field breadth before turning to one of the core aspects about this concept that is still under debate, namely the question of how organisational fields are formed.

There has been an unfortunate overuse of the term ‘organisational field’, which has come to indicate the importance of a topic rather than to describe participation and effect. DiMaggio and Powell’s (1983) definition quoted above called for taking fields as constellations of many different types of organisations, but many studies that have referred to this concept have included a rather limited range of organisations. For example, DiMaggio’s (1991) often-cited study of field change in American art museums studied only two types of organisations, an art museum at the local level and a philanthropic organisation at the national level. Zietsma and Lawrence (2010) had four types of organisations or constituents in their investigation of the forest industry changes in British Columbia, including forestry companies, environmentalists, government officials and members of the local community. Slightly broader is the seven types of organisations in Scott, Ruef, Mendel, and Caronna’s (2000) study of the transformation in the field of health care in San Francisco Bay area, although this number appears modest considering that the study covered two major shifts over five decades.

There are also other well-known studies that carry the term ‘organisational field’ in the title, but which have studied less than five types of organisations or other constituents. Examples of such studies are Greenwood et al. (2002 – three types); Maguire et al. (2004 – four types); Ansari and Phillips (2011 – four types), which nevertheless have all been studies of complex subjects. However, if the number of organisations included is inconsequential, almost any study can be a field study. We do not question the validity of these reputable studies, but rather express our concern about the uses of the concept ‘organisational fields’. The importance of this matter for us is evident in our research design, which we will describe below.

Creating Organisational Fields through Social Interaction

One approach to conceptualise organisational fields has been to see social interaction as the driving force. In DiMaggio and Powell’s (1983) classic piece an organisational field is formed, or ‘structured’, through organisations relating to each other: by mutual awareness of a common enterprise, by interaction between field participants, by this interaction developing into patterns of either domination or cooperation and by increase in the amount of information about the field overall. As the first three of these conditions are distinctly social in nature, the essence of this argument is that fields arise from an increase in social interaction between the interested parties. While in principle this definition could also include incumbents and challengers, the requirement for interaction implies a view of field formation where no one organisation is quite able to drive the process solely towards their own aims. The third condition suggests that domination is possible, but only after some time when social interaction has developed into that type of a pattern. With no clear incumbent to direct the process, field development also seems to involve chance and therefore arguably proceeds as gradual evolution. In Geels’ (2012) words this is a cascading process, pieces falling in place one after another. This conception clearly follows the Berger and Luckmann (1966) logic of how new entities become reality over time through social processes, or ‘social construction’.

Another perspective that relies on social interaction as the driving force has suggested that the emergence of new organisational fields is driven by power and culture. These are the pivotal means by which social movements accomplish their aims. This view, provided by Fligstein and McAdam (2011), draws mainly on social movement scholarship. As our case study is about an emergent field, this perspective is particularly relevant here, since this area of work has discussed extensively ‘emergent conflict and change’ (Fligstein & McAdam, 2011, p. 22). Their core argument departs from their criticism that institutional theory and network analyses have suffered from a lack of a sufficient view of power and agency, at least to feed analysis of cases of emergence.

For Fligstein and McAdam, there are a number of factors that are part of the rise of organisational fields, or what the authors call ‘Strategic Action Fields’ (SAF). We mention here the most relevant factors for our discussion: Individual actors will be unable to control the organisation of a space with a new opportunity, and social movement type of groups will form to provide solutions that are part of the new field. Actors also need considerable political skill to gain adherents to their conception of the field that they are seeking to construct. They need to engage in the production of cultural frames for the new field in order to attract members and resources. Eventually, fields become organised essentially around political coalitions, or they are based on domination by incumbents over challengers. The state tends to play a role in field development, whether through legislation or by providing material resources1 even if the consequences may only sometimes be intended and at other times unintended. There also tends to be episodes of contention in field development, as differing views arise about field purposes and participant roles. Fields can also drift into chaos or crisis by external shocks, which may provide an opportunity for reorganising aspects of society, and thus to generate new fields. In summary, while there are other actors involved (e.g. the state) and although successful field emergence is not guaranteed (there may be crises and episodes of contention), social movement type of groups tend to rely on developing power positions and to use cultural resources to drive the emergence of new organisational fields.

Thus these are two approaches to explain how social interaction drives field emergence. The DiMaggio and Powell approach argues for more evolutionary progress as organisations interact around their issues of interest. The Fligstein and McAdam’s SAF approach suggests a more political view, where organisations use their social skills to create coalitions around themselves, to ensure resources and influence. Other work along the same lines testifies the attraction of the social perspective for scholars. Bueger (2013), Wright (2009) as well as Emirbayer and Johnson (2008) also argue in favour of the conception of fields in which power, struggle and network relations define field development.

Creating Organisational Fields through Cognitive Action

Since the Berger and Luckmann (1966) argument about the social construction of reality there has been a strong emphasis to explore the importance of meaning and meaning-making in relation to social phenomena. As in the original Berger and Luckmann argument, common social reality is established between (individuals or) organisations through shared understandings, which lead to patterns of interaction (Scott, 2001). As these meanings are shared, they also serve to set boundaries for organisational communities, by defining such things as membership, appropriate behaviour and relationships between communities (Lawrence, 1999). As these shared understandings are generated in interaction, repeated interactions will produce collective beliefs (Greenwood et al., 2002).

According to this thinking, fields acquire shape once mutual understandings emerge. Martin (2003) suggests that fields come into existence when a ‘set of analytic elements’ becomes aligned between organisations, and it no longer is sensible to discuss the positions of these organisations in terms of contrast. While social interaction is needed in this perspective as well, it is the ‘shared subjectivities or culture’ that are the result of this interaction, which in turn gives rise to a field (Martin, 2003, p. 42). In practice, Martin continues, the background action may be that organisations share suppliers or clients, which may produce ‘regularities in orientations’ (p. 42). For Martin, constitution of a field for any individual (or organisation) involves understanding their past, current and future situations in relation to institutions. Thus, the mere social interaction does not go far enough to establish a field, but mutual cognition about factors of the field, and one’s own position in it, are needed in this view.

While there is an implied recognition that social interaction is a factor, it seems to be merely a contextual factor to precede the development of common understandings. This seems to be the position also of Maguire et al. (2004) and Furnari (2014). Through these formulations, field emergence is dependent rather on the development of shared systems of meaning (Zietsma & Lawrence, 2010) or an institutional logic (Friedland & Alford, 1991; Reay & Hinings, 2009) than on the social engagement between organisations.

These two views, the social interaction view and the cognitive action view, have then some overlap in explanations of organisational field emergence. But they nevertheless portray distinct emphases on what forces generate new fields. We return to them in our discussion section.

METHODS AND DATA

Our curiosity about the nature of organisational fields, at the formative ‘early moments’ stage when few things are settled, meant that this study ought to be exploratory. Therefore, we designed our project to be based on qualitative data from many types of organisations. As we noted above in the introduction, our working definition of ‘smart city’ has been the objective to use data technologies in urban utility services. By these we mean energy, water, waste and transport services. Yet, we were careful not to impose this definition on our respondents, and we let them tell us their views on this concept. We describe briefly in the next section some of these conceptions.

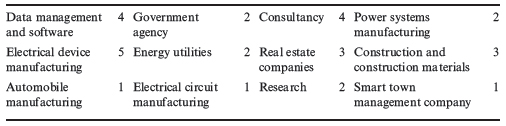

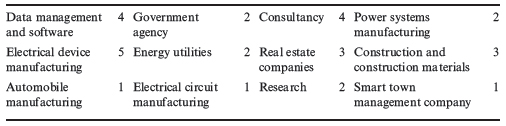

Our study included 30 organisations, which we interviewed and collected smart-city related documents at. We conducted this study as a form of ‘organisational field’ (DiMaggio & Powell, 1983) type of study, with a broad range of different organisations, linked by their common interest in pursuing and promoting ‘smart’ solutions in urban context. These are all organisations that are actively engaged in developing smart-city solutions, or are involved and shaping in other ways the smart-city ‘space’ (e.g. government agencies or university research institutes). The appendix shows the breakdown of these 12 types of organisations. Due to a commitment to confidentiality and anonymity in data collection, the organisation names cannot be made public. We also attended five events that were either about or closely related to the topic of ‘smart city’. In these events there were speakers mainly from corporations, who discussed their experiences in implementing smart-city solutions. Speakers in these events included also representatives from government and academia, providing their observations in regards smart-city development.

Our approach was a form of case study method. For a study of ‘early moments’ and entrepreneurial efforts, case study has advantages as it is ‘suited to description of … demonstrating the variety of mutually shaping influences present’ (Lincoln & Guba, 1985, p. 42). Yielding large amounts of contextual and processual detail (Flyvbjerg, 2011) and flexibility throughout the research process (Eisenhardt, 1989) are advantages of the case study method when the object of research is an ambiguous entity like a field at the ‘early moments’ stage. Thus, we treated Japan as a geographically defined case within the topic of the creation of the organisational field around smart-city development.

We performed a standard qualitative analysis on our collected research data. Qualitative research methods tend to produce data that is ‘unstructured and unwieldy’, requiring the researcher to furnish ‘coherence and structure to the cumbersome data set’ (Huberman & Miles, 2002, p. 309). With data that is often descriptive or exploratory, the qualitative researcher’s ultimate interest is to use the data to explain or evaluate phenomena (Ritchie & Lewis, 2003). These features of qualitative data fit our case context, the ‘early moments’ of field development.

We used NVivo in our analysis, to ensure consistency and thoroughness, to code the interview and documentary material for organisational efforts, challenges and for the understandings of organisations about what a ‘smart city’ is. This analysis resulted in typologies of efforts as well as challenges that are the organisational experience in building the organisational field of smart-city development in Japan. We present these typologies of efforts and challenges in the ‘evidence’ section below.

EVIDENCE

In this section we report the more incisive aspects of how organisations have sought to implement smart-city applications in Japan. We focus on two of the most common strategies in these initiatives, which illustrate different approaches at different scales. We also describe some of the main challenges organisations have been facing in their initiatives. The efforts and the challenges serve to illustrate what works and what does not at ‘early moments’ of field emergence. With this evidence we make our argument: that on the ground, the more impactful smart-city development, at least at the ‘early moments’ stage, requires assembly type of efforts. At a broader level this means that the building of organisational fields is fundamentally about concrete, practical projects that begin to give a visible, material shape to the new organisational field.

Smart-City Definitions

We asked our respondents what are their understandings of the concept of ‘smart city’. Our query resulted in a variety of views of what the label and idea ‘smart city’ means. Many referred to energy systems, and the possibility to reduce energy consumption through the use of ICTs. Some considered ‘smart city’ to mean resilience and stability in energy supply, which are values that the Japanese government has been promoting since the 2011 Great East Japan Earthquake. Others, particularly the software companies, referred to data, and the possibilities to take advantage of data collection and analysis to either improve or change various systems of operation for urban services. Yet other respondents suggested that smartness relates to using new technology to preserve the environment and to improve the quality of life.

Finally, there were some organisations in our research participant group that suggested smartness to be about collecting sensor data. This data would be used to reorganise urban services and functions in ways that reallocate roles and responsibilities between consumers, private sector organisations, civil society organisations and the government. As this non-exhaustive list of the most common views for smart-city definition in our research indicates, there is a considerable variability in regards to this concept. At the same time, these organisations recognise this label, and respond to it, which suggests it is a theme that binds them to a common purpose, making them participants of an organisational field.

Smart-City Initiatives

One approach to creating smart-city solutions is individual projects that develop concrete products and services. Several of these combine software and sensor technology that are then implemented into existing processes. One such example is in waste management. A company providing a waste related smart-city solution has developed a software that allows a sensor device to monitor the level of waste in containers. The sensor feeds data to a management centre that uses the data to optimise the routes of the collection trucks. This ‘on-demand’ type of approach replaces the conventional practice of scheduled pick-ups, designed to collect single type of waste at a time, regardless of the amount accumulated. The on-demand approach aims for higher efficiency by maximising the collected amount per round. The crucial work here has been the development of the software, coupling it with sensors, and assembling these together with existing practices and resources of refuse collection into a new arrangement of waste management.

In a second example of individual projects another company brings the power of data analysis to energy management. The objective is to influence consumer behaviour through providing periodic reports of energy consumption that are compared with consumption of similar households in the area. This company’s effort consists of bringing together insights from behavioural psychology, the customer energy use data from their clients the energy utilities, and software they have developed to analyse this use data. Their output is the customised energy reports where they use the insight from psychology that we are most likely to take action when our peers take action. Thus, their reports achieve better effectiveness by harvesting energy user data and matching that with customer profiles. While the reports make consumers better informed and more inclined to actively manage their energy consumption, they are also a novel approach for energy companies in customer relationship management. Again, the core organisational effort here is arranging data access, software development and assembling the different pieces into compelling reports for consumers.

Our first two examples describe the assembly of disparate items into complete systems, but our third perspective goes further into connecting systems. A central feature of smart-city solutions is information exchange, which requires that the different data repositories are connected into a network. The interoperability of electrical devices enables simultaneous control over various devices, in order to manage energy use and grid stability, both in regular operation and at time of emergency. Thus, many software companies are working to provide platforms to connect devices that previously have not been linked. One of our respondents expressed this central interest in smart-city development in the following statement:

Smart cities is an enabler of the Internet of Things, that includes large-scale databases, which in turn includes large clusters of computation nodes, all working to manage energy, safety, etc. There is a clear application of managing resources, of energy, of traffic, all things that cities do. Smartness comes from the fact that you can interconnect everything and process the information, and the technologies are coalescing now. You could not have done smart cities when there was the machine-to-machine era. (CTO of a software company)

In his subsequent comment the respondent noted that through this connecting of different systems it is possible to begin rearranging how different functions operate in society. Yet, for our purposes, this comment reveals again the core mode of implementing smart-city solutions: different elements are assembled together, and organisations are seeking for fitting combinations of functions, and the most sensible ways of furnishing these connections. This is a central factor in smart-city development but we think it is likely to apply more broadly in the 21st century, as all organisational operations begin to be dependent on information systems.

Beyond individual projects, another prominent approach to smart-city initiatives in Japan is the building of ‘smart towns’, which are assemblies of different solutions put together at a community scale. There are several of these ‘smart town’ projects around Japan, for example the Fujisawa and the Kashiwanoha sites around Tokyo, and one site in the Toyota city area. These are newly built communities with several distinct features: they consist of houses that use local renewable (often photovoltaic, but also wind) energy; households have their own storage batteries to guarantee stable supply of energy; inhabitants connect their electric vehicles to the electricity grid and all houses are connected to a community energy management system, which allows the complete monitoring (and adjustment if necessary) of the energy use of an individual household. These are large-scale, long-term projects that are usually led by one or two large technology companies such as Panasonic, Hitachi and Toyota and which are joined by smaller service or technology device providers. The funding for these projects tends to be a mixture of public and private sources.

These ‘smart towns’, while more complex than the individual projects described above, suggest the same tendency in smart city development. In terms of project execution, they involve many different types of companies, who bring their own expertise to the project. Also many technologies are involved, serving different aspects of urban life. These ‘smart towns’ are assemblies of organisations, products and services, of different types of information generated about living in a city and of ideas on what city living ought to be about. Just like the individual initiatives at a smaller scale, the ‘smart towns’ are essentially ‘ensemble’ solutions that are assemblies of other solutions of narrower scope, that are propositions of new ways of living.

Finally, there are other substantial organisational ‘products’ that serve to indicate the relative stability of the idea of the ‘smart city’. Organisational commitment to the ‘smart city’ idea is visible through the following list of items: there are some annual seminar and conference events on this topic; corporations and other organisations have websites, printed documentary material, as well as seminar presentations (which are usually available on the website) on their smart-city solutions; there is on-going funding from the central government for this subject area; there is a national association with almost 300 members (JSCA, 2013); and in a handful of companies there are distinct professional positions, such as the position of a ‘Smart City Manager’. While it is conceivable that any of these could be discarded still, the on-going commitment of organisations for these in the Japanese smart-city community suggests that they are elements with some permanence. Thus, the ‘early moments’ smart-city development in Japan has involved much organisational effort towards producing concrete, material or otherwise actual outputs.

Smart-City Challenges

We also report some of the challenges that organisations in Japan have faced in their smart-city initiatives. While on the one hand these challenges are part of the overall narrative of smart-city development, for us they are also important evidence about field emergence, and in particular about the limitations related to socio-cognitive efforts at the ‘early moments’ phase. The variety of these problems shows how realising smart-city objectives will require efforts in many areas, that is assembly of disparate elements into coherent propositions and solutions. We describe these challenges through two fundamental questions for organisations in smart-city development, which highlight how social and cognitive efforts have been inadequate in early field development.

One of the main questions for organisations in smart-city development is about ‘what solutions to build’. This question contains a cognitive and a social dimension. The cognitive dimension relates to the issue of vision. Some of our technology company respondents explained that it is important for the purposes of investment and operational strategy to have a clear future vision about smart-city development. Yet, even if there have been many visionary statements about the benefits of smart-city solutions, very few pronouncements have gone past these high-level proclamations to break the vision into practical implications. One of our respondents noted that there have been calls for more renewable energy and less nuclear energy, for example, but that these should be accompanied by clearer parameters for action, that is a more specified vision about smart-city development. Such a specified vision would contain specific answers to a number of crucial questions, such as what is the precise problem to be solved with these solutions, and what is the value hierarchy to decide between competing interests, such as environmental concerns, cost efficiency, speed of delivery and social inclusiveness of service. The answers to these questions would then be translated into concrete system specifications for finding the technical solutions and thus made more actionable for companies that develop technical systems. The difficulty for organisations to project, or ‘see’, alternative and most likely trajectories for smart-city development is a cognitive obstacle for field development.

The question ‘what solutions to build’ has also two social aspects to it. First, several of our organisational respondents noted that there is a shortage of effective leadership around smart-city development. More determined leadership would be needed for providing a vision, which would prompt organisations into more committed and coherent action. This type of leadership would specify the above-mentioned aspects about problems and values more clearly and commit their organisations to a certain development trajectory. A comment from one of our respondents about the absence of ‘platform leaders’ epitomises this leadership shortcoming. ‘Platform leaders’ take a ‘base’ and assemble a variety of elements on top, to create an ‘ensemble’ of solutions. In the smart-city context this type of a base could be a technical system of data collection and management, supporting a range of urban services and functions. A broader view would perceive a base as a vision about a network of smart-city solutions, upon which the leader would assemble disparate elements of technologies, service propositions and institutionalised rules and practices into an ‘ensemble’ of solutions. In most cases, such a network of solutions would be built by a collection of organisations, which suggests that missing such a leader is de facto an absence of a social movement type of a leader.

Ideas about what solutions to build may also come from customers, which is the second case of how social interaction has failed to foster smart-city development. One technology company involved in many smart-city projects noted that usually technology solutions are developed as a response to customer-defined problems. A remark from the respondent of this company highlights the dynamic of this form of interaction:

One big difference from our previous experience is that in this case nobody knows what we should do. Vision is okay, but that is still high-level … when we developed our … system, we had a very good customer, a good partner. Customer is always demanding: I want to do this, I want to do that, can you do that? … This kind of a heavy discussion is really good for us to develop new things and to find solutions. At this moment, in smart cities, we have no such customers. (Divisional Managing Director of a large technology company)

In smart-city development this type of social interaction between organisations has been absent, which has made it more difficult for organisations to make investment decisions regarding technology development.

The second fundamental question in smart-city development is ‘how to make money’. Based on our discussions with organisations, they have had great difficulties in generating answers to this question. The most common lament from organisations in Japan in regards smart-city development is the absence of business models. In other words, there is a widespread confusion about how to make money with smart-city solutions. Development of a business model is a result of organisational efforts, and the failure of these efforts to produce this outcome can be traced back to social and cognitive shortcomings.

At the heart of smart-city development is data, to which the inability to develop viable business models is keenly related. Every organisation is dependent on information, whether about its customers, its competitors, the efficiency of its internal operations or the sales of its products and services. Thus, the importance of data is not a new idea. However, data collection in smart-city solutions has raised the quantity of data, as well as the range of its potential sources. Useful example of this change is in the area of energy, the most prominent area of smart-city activity in Japan. The ‘smart meter’, providing energy consumption information at 30-minute intervals instead of the conventional monthly data reading, is the most salient energy-related smart-city solution. As indicated by Tokyo Electricity Company’s website, ‘smart meters’ enable an immense increase in the volume of data. Their implementation of ‘smart meters’ has consisted of 2.4 million households in one area of Tokyo by July 2015, with an increase from one monthly data point to 1,440 data points per month (Tepco, 2015). This volume of individualised data about energy use creates a new situation for data management, even for a large electricity utility.

The cognitive challenge concerning data increase relates to the profiles of the organisations involved. Those organisations that have provided utility services to large geographical areas are accustomed to designing their strategies based on two types of customers, the industrial and other large-scale customers, as well as the mass of household customers. Their capabilities in strategic planning have thus developed for contexts of large units. They are now facing difficulties in conceptualising the possibilities and strategic positioning in a context where commercial contracts could be tailored for each household customer. Moreover, relatively large fluctuations over 24 hours of daily household energy use are significantly different from the pattern of more stable use in industry or, for example, in hospitals. These producers of utility services in ‘bulk’ are finding it complicated to rethink their services and data use on ‘individualised’ basis.

Another challenge about business model development relates to the positioning of the smart-city demonstration projects that many organisations have taken part in. As the respondent from one small software developer explained, these projects bring participants knowledge and visibility in this area, but they have little impact for developing business models for smart-city solutions. They noted that these project goals are designed mainly for technical purposes, to test ‘whether a signal comes through’. These projects are not evaluated on business success, but only on ‘can you do this’? They are not testing and examining economic structures and incentives that may uphold the production of smart-city services and products. According to this respondent, such projects could explore for example ‘demand side management contracts’, which would be evaluated for their effectiveness for revenue generation. Yet, the government-funded projects have so far not conceptualised smart-city development through these types of objects but merely as a technical endeavour. In other words, developing technology in these types of projects has become such an institutionalised approach that it does not seem possible to think of other aims for them.

Finally, there is a factor of Japanese culture that complicates the kind of social interaction that would facilitate the development of new business and field emergence. This cultural factor is the high value on trust-relationships, which makes it difficult for new companies to gain a foothold where established or large companies already operate. Respondents from several small firms noted that the large companies involved in smart-city development are reluctant or refuse to talk to newcomers. Building the trust-relationships and gaining access to those networks that are included in projects and other partnerships takes a long time. Information about new ventures is difficult to obtain without contacts, and thus gaining access to new development networks is difficult. This has meant that small firms aiming to provide smart-city services are not able to test and develop their business model while working with large-scale customers. It has also meant that many of the smaller firms have no position in the smart-city field, where the large technology, consulting and utility companies are most visible. The mutual awareness that DiMaggio and Powell (1983) listed as one defining feature in field development is limited to the large companies that are already known. This constraint on social interaction has meant that only few small firms have been able to contribute their new ideas to smart-city development.

In this evidence section we have described some of the more prominent types of efforts and challenges at the ‘early moments’ stage of smart-city development. In this case, the more concrete and tangible efforts seem more potent for a lasting impact. At the same time, there have been many challenges that are linked to social and cognitive types of efforts. In the next section we discuss how these findings relate to the predominant theoretical insights on field emergence.

DISCUSSION

As we stated at the beginning, our claim in this article is that smart-city development is carried out primarily, at least at the ‘early moments’ stage, by assembly type of efforts. Organisations create smart-city solutions by putting together a variety of technical, social and institutional elements. We referred in the introduction to bricolage, a concept that has been borrowed into organisation theory from Levi-Strauss (1967, in Garud & Karnøe, 2003). We return to this concept below to discuss how it relates to our perspective of assembly. By assembly effort we mean that the formation of organisational fields is about organisations constructing concrete, material projects by which the field begins to acquire visible, largely material shape.

We remind that our empirical study has a specific temporal context, which distinguishes it from most other studies on organisational fields. We have called our time frame the ‘early moments’. By this term we refer to that period when several key elements are still unsettled or unproven. Typical elements of ambiguity are viable business models, dominant designs in technology (Tushman & Anderson, 1986) and questions about which organisations will dominate product and service markets. We proceed now to contrast the arguments of the theoretical literature with the evidence from our empirical case. In the following, we raise five points.

First, our analysis suggests that the arguments of prior literature on organisational fields apply only partially to the case of smart-city development in Japan. DiMaggio and Powell (1983) suggested that social interaction is the driving engine in field creation, and undoubtedly it plays a part in the development of any open systems. In smart-city development, there has been inter-organisational cooperation in large projects and in small projects. The ‘smart town’ projects have been led usually by large technology companies, but other organisations have participated in project consortia. Equally, there has been some initial development of mutual understandings about a ‘smart city’, with a common term and a recognition that information and communication technologies are an important part of this development. However, in many respects the social and cognitive interactions provide little explanation to the development of the organisational field of ‘smart city’ in Japan.

The circumstances around cognitive interaction appear to us as the main stumbling block in smart-city field development. The cognitive choices that seem to have been made are impeding smart-city solutions becoming more widely implemented and accepted. The ‘early moments’ stage seems to have the effect that actors find it very difficult to ‘see’ or ‘imagine’ both upwards and downwards. In an upwards case, the focus of the demonstration projects is in technical detail, with an aim to test technical functionality. As we have explained in our evidence section, this orientation has foreclosed the development of business models at a higher-level, which could be studied if the projects were positioned towards social interaction in commercial relationships. In other cases there has been an inability to ‘see’ downwards, i.e. to provide more detailed specifications from a higher-level statements or decisions. For example, there has been no shortage of visionary statements about smart-city development, but accompanying detail on priorities about technology or cost has been lacking.

Perhaps the most revealing instance of these cognitive difficulties has had an impact both upwards and downwards development. There has been an evident inability for users of mass data to think about large amounts of data in atomised terms. These users of mass data are, for example, energy utilities who in their conventional business model collect large amounts of data in order to provide energy with economies of scale in supply and delivery. If the management of cities is starting to revolve around data use that is individualised or detailed for time and application, then the old business approach may need to be changed. The inability at the moment to imagine the new business model complicates making more practical technical decisions while also befuddling thinking on the broader question of the new business model for energy utilities.

The social interaction difficulties have mostly followed the cognitive ones. The absence of clarity about functioning business models and dominant technology designs (Tushman & Anderson, 1986) has meant a lack of clear signals in client relationships about development priorities. It has also hindered determined leadership that would provide a detailed vision of how to proceed. On the other hand, this case has shown that social interaction may fail to produce results at ‘early moments’ stage also due to specific cultural context. As we have described, trust relationships are of prime importance in Japanese business culture, the lengthy development of these relationships fits poorly with urgent progress towards field maturity.

In fact, the social interaction view appears less compatible than the other perspectives with the ‘early moments’ phase, which would usually consist of vibrant experimentation. The social interaction view suggests a somewhat passive imagery, in its reliance on gradual evolution over time. Evolutionary dynamics is an explanation where a compounding effect over a long period of time will institutionalise technology uses, professional practices and actor roles. Thus, with long enough perspective, one may arguably always see an impact that is in some ways produced by social interaction. Our case focuses attention on the mechanisms that impact field development over shorter term. We have found that even if there has been social interaction between organisations in project consortia or in supply relationships, social interaction appears to explain little at the ‘early moments’ stage for smart-city development in Japan.

The cognitive interaction perspective may precede social interaction. There is still a lingering conceptual dissonance about the definition of a ‘smart city’, betrayed by the range of views that organisations have told us about. At the same time, there is agreement about some general aspects in regards the concept, such as that smart-city solutions involve ICTs, and that the universal objective in these projects is to gain improvements in operational performance. Certainly these are general aims that most, if not all, private sector companies would adhere to even without any association with the concept ‘smart city’. The emergence of a concept very early on, even with such elementary features of definition, suggests that cognitive accord, or at least some elements of it, may surface relatively early in field development. These, perhaps fragmentary, features may serve to give some support to the early efforts of field development. Moreover, we have suggested above that the cognitive confusion appears to hold back some of the social integration. Therefore, it seems that some cognitive development is necessary before achieving mutual awareness and partnerships around an organisational field. Interestingly, this finding is opposite to what authors such as Maguire et al. (2004) and Furnari (2014) have suggested.

Instead of the cognitive and social interaction effects, we think that there is some degree of permanence that the field has already gained through concrete and material organisational actions. Items such as annual events, a national association, corporate commitments through websites, documentary material and some professional positions suggest that organisations are making concrete commitments around smart-city solutions. Above all, the ‘smart towns’ is the most tangible and visible example of such durable smart-city solutions. Their partial role as demonstration projects may imply certain transience, but they are completely operational, with inhabitants and customary urban services and functions. We recognise it is not impossible for such communities to be repurposed at some point, with the label ‘smart town’ substituted for some other label under some new circumstances. Nevertheless, the substantiality of the above-mentioned actions, and especially the materiality of the ‘smart towns’, suggests that they are not easily erasable and therefore give distinct durability to the emerging field in comparison with the socio-cognitive actions.

Our second point is the temporal aspect that our argument adds to the theory of organisational fields. We think that the concrete, material projects and other substantive organisational action we have described are the precursor to the cognitive and social interaction. Now that these concrete representations have been built and are on display, it is easier for a common understanding to emerge about ‘smart city’. The obvious example of this is the ‘smart towns’, the most tangible representation of a ‘smart city’. These are even organised tours for these sites, which enable the general public to look inside a built ‘smart town’. Seeing a physical ‘smart town’ nurtures a cognitive agreement on what a ‘smart city’ is, but such a concrete representation also facilitates interaction between organisations that may be contemplating joint smart-city projects. It seems likely that cognitive and social interaction may have their impact at a later stage when the material efforts have first established the field to a certain degree.

Third, we think that the idea of ‘commitment’ represents a further distinction between the concrete, material efforts and the cognitive and social interaction in field development. This is a useful auxiliary term for this discussion, and there are two important aspects to note. First, we think that developing organisational fields are more likely to gain durability when their building involves assembly type of efforts. Organisational fields are complex amalgamations of technical, social and institutional factors. Their complexity requires at least some level of assembly, a point that has been muted in past literature, but which we emphasise in this argument. Assembly necessarily always involves organisations, as putting together credible large-scale propositions requires considerable resources as well as legitimacy. Assembly of multiple elements together into a coherent proposition necessitates more commitment than more simple, discrete installations. Thus, assembly as a type of effort entails that organisations are committed at a higher level to see an organisational field realised.

Second, we also suggest that concrete, material outputs imply more commitment than social and cognitive efforts in the development of organisational fields. Material commitments, such as developing products or erecting buildings, are likely to involve more cost and risk than most social and cognitive efforts, such as establishing partnerships or communicating a new conceptualisation of a technology or practice. In our case study, the building of ‘smart towns’ is the obvious example of material outputs that show significant organisational commitment. In contrast, we have also described how providing general smart-city visions without technical and other particulars results in uncertainty and lower level of commitment. Thus, committing material resources engages an organisation more firmly into an undertaking than assurances of social or cognitive accord.

Fourth, our emphasis on concrete, material efforts in the emergence of fields has potential implications also on analysis of broader societal development and the dynamics of innovation. The idea that material commitments by organisations are more solid evidence of a shift is useful for analysis of contemporary trends. Trends, such as ‘management fashions’ (Abrahamson, 1996), tend to create a hubris-like expectations of change, which may in the end turn out to be largely unfounded. The proponents of such trends inflate the assumed benefits until lack of evidence creates a response to counter the trend. In David and Strang’s (2006) account of Total Quality Management (‘TQM’) the early promotion of the practice was based on generalised discourse and exaggerated claims. After the trend collapsed, it became founded more solidly on actual technical expertise, with technical specialists providing the expert advice. Analytical focus on the absence of the concrete, material foundations of TQM would potentially have been able to expose the weak foundations of this management fashion in its early stage. In this way this perspective may help deter ill-considered organisational behaviour, such that may lead to larger economic problems such as bubbles.

Finally, the idea of assembly is a type of bricolage, conveying the sense that committed actors are constructing a new entity. We find conceptual overlap with some scholars that have borrowed Levi-Strauss’ bricolage – concept, and here we refer to two sets of them. Garud and Karnøe (2003) took Levi-Strauss’s concept of bricolage to mean the ‘co-shaping of the emerging technological path’ (Garud & Karnøe, 2003, pp. 278–279), with considerable weight on the dispersed nature of technology development. In their view, there are distributed actors contributing artefacts, tools, practices, rules and knowledge. Maguire et al. (2004) argued that emerging fields in particular are spaces that are unconstrained, and that they consist of disparate materials from which to build new institutions from. They note that these spaces need to be assembled ‘in ways that appeal to and bridge disparate groups of actors’ (Maguire et al., 2004, p. 674). However, one of the defining features in both of these works is their considerable emphasis on the emergence, that is the gradual accumulation of momentum that these efforts create.

Our emphasis is less on the evolutionary dynamic that is evident in the formulations by these authors. Instead of this imagery of slow accumulation of artefacts and other evidence of the field, our emphasis is rather on the concreteness of the efforts. We offer assembly in the sense of bricolage that is purposive, intentional, not always successful, but learning from mistakes while making concerted efforts to accomplish the organisational objectives. At the early moment stage, as we have reported in the smart-city case, organisations make committed efforts to assemble tangible smart-city elements. These are material expressions of the field that facilitate the understanding of and the formalisation of social relations within an organisational field.

CONCLUSION

In this article we have attempted to show what organisations are trying to do in the area of smart-city development in Japan. While our account is necessarily limited in scope, through the descriptions of the initiatives and the related challenges we hope to have conveyed the sense that smart-city development is an endeavour of experimentation, of lofty ideas and also of setbacks and obstacles. We have argued that the characteristic task for implementing smart-city solutions successfully is about the assembly of disparate and especially material parts. From this we have drawn our conclusion that fields are primarily generated at the ‘early moments’ stage through concrete and committed organisational activities, as opposed to the more fleeting cognitive and social interaction.

As socio-cognitive explanations of organisational behaviour have dominated our journals in recent decades, this alternative perspective of studying the impacts of more substantive and material efforts is open territory for further research. A follow-up work to our research would continue collecting data on smart-city development to reach the point when the field appears mature. This would allow one to make more definitive statements than we have made about the impact on field development that the three types of efforts, the concrete/material, the cognitive and the social interaction may have. Such a study could also confirm over a longer period the temporal sequence that we have suggested between these efforts.

We also believe that there is use for more studies of ‘fields-in-the-making’ (cf. ‘technology–in-the-making’, Garud & Rappa, 1994, p. 345). On-going field development is a challenging topic of work, as there tends to be a few stable aspects of the field that the researcher can pivot their study on. But as we have demonstrated with our study, a design that avoids the ‘retrospective rationality trap’ (Garud & Rappa, 1994, p. 348) allows one to often arrive at relatively novel findings. When respondents have no fixed ideas yet about working business models, and when challenges they have faced are still fresh in their memory, one can paint different pictures about how organisations behave. Incessant technological development is likely to further accelerate the introduction of new technologies and service concepts, and particularly assemblies of these as new organisational fields. This provides ample opportunity to not only enrich our conceptual reservoir but also to make an important practical contribution by explaining to managers which organisational efforts have most impact in field development.

NOTE

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

R. A. Nyberg gratefully acknowledges financial support from the Canon Foundation Europe, and the SRA Fund of the Said Business School of University of Oxford. R. A. Nyberg also wishes to acknowledge institutional support by University of Oxford, Institute of Science, Innovation and Society; by University of Tokyo, Graduate School of Public Policy and by George Mason University, Department of Sociology and Anthropology. We also thank Marc Ventresca and the volume Editors for comments on an earlier version of this text.

REFERENCES

Abrahamson, E. (1996). Management fashion. The Academy of Management Review, 21(1), 254.

Angelidou, M. (2014). Smart city policies: A spatial approach. Cities, 41, S3–S11.

Ansari, S. (S.), & Phillips, N. (2011). Text me! New consumer practices and change in organizational fields. Organization Science, 22(6), 1579–1599.

Berger, P., & Luckmann, T. (1966). The social construction of reality: A treatise in the sociology of knowledge (1st ed.). Garden City, NY: Doubleday.

Bianchini, D., & Avila, I. (2014). Smart cities and their smart decisions: Ethical considerations. IEEE Technology and Society Magazine, 33(1), 34–40.

Bourmpos, M., Argyris, A., & Syvridis, D. (2014). Smart city surveillance through low-cost fiber sensors in metropolitan optical networks. Fiber and Integrated Optics, 33(3), 205–223.

Bueger, C. (2013). Responses to contemporary piracy: Disentangling the organizational field. In D. Guilfoyle (Ed.), Modern piracy: Legal challenges and responses (pp. 91–114). Cheltenham: Edward Elgar.

David, R. J., & Strang, D. (2006). When fashion is fleeting: Transitory collective beliefs and the dynamics of TQM consulting. Academy of Management Journal, 49(2), 215–233.

Davis, G. F., & Marquis, C. (2005). Prospects for organization theory in the early twenty-first century: Institutional fields and mechanisms. Organization Science, 16(4), 332–343.

DiMaggio, P. J. (1991). Constructing an organizational field as a professional project: US art museums, 1920–1940. In W. W. Powell & P. DiMaggio (Eds.), The new institutionalism in organizational analysis (pp. 267–292). Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press.

DiMaggio, P. J., & Powell, W. W. (1983). The iron cage revisited: Institutional isomorphism and collective rationality in organizational fields. American Sociological Review, 48(2), 147–160.

Eisenhardt, K. M. (1989). Building theories from case study research. The Academy of Management Review, 14(4), 532–550.

Emirbayer, M., & Johnson, V. (2008). Bourdieu and organizational analysis. Theory and Society, 37(1), 1–44.

Fligstein, N., & McAdam, D. (2011). Toward a general theory of strategic action fields. Sociological Theory, 29(1), 1–26.

Flyvbjerg, B. (2011). Case study. In N. K. Denzin & Y. S. Lincoln (Eds.), The Sage handbook of qualitative research (4th ed.). London: Sage.

Friedland, R., & Alford, R. R. (1991). Bringing society back in: Symbols, practices, and institutional contradictions. In W. W. Powell & P. J. DiMaggio (Eds.), The new institutionalism in organizational analysis (pp. 232–263). Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press.

Furnari, S. (2014). Interstitial spaces: Micro-interaction settings and the genesis of new practices between institutional fields. Academy of Management Review, 39(4), 439–462.

Garud, R., Jain, S., & Kumaraswamy, A. (2002). Institutional entrepreneurship in the sponsorship of common technological standards: The case of sun microsystems and java. Academy of Management Journal, 45(1), 196–214.

Garud, R., & Karnøe, P. (2003). Bricolage versus breakthrough: Distributed and embedded agency in technology entrepreneurship. Research Policy, 32(2), 277–300.

Garud, R., & Rappa, M. A. (1994). A socio-cognitive model of technology evolution: The case of cochlear implants. Organization Science, 5(3), 344–362.

Geels, F. W. (2012). A socio-technical analysis of low-carbon transitions: Introducing the multi-level perspective into transport studies. Journal of Transport Geography, 24, 471–482.

Greenwood, R., Suddaby, R., & Hinings, C. R. (2002). Theorizing change: The role of professional associations in the transformation of institutionalized fields. The Academy of Management Journal, 45(1), 58–80.

Hollands, R. (2008). Will the real smart city please stand up?: Intelligent, progressive or entrepreneurial? City, 12(3), 303–320.

Huberman, A. M., & Miles, M. B. (2002). The qualitative researcher’s companion. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

JSCA. (2013). JSCA Japan smart community alliance – Membership list. Retrieved from https://www.smart-japan.org/english/memberslist/index.html. Accessed on January 14, 2016.

Lawrence, T. B. (1999). Institutional strategy. Journal of Management, 25(2), 161–187.

Leblebici, H., Salancik, G. R., Copay, A., & King, T. (1991). Institutional change and the transformation of interorganizational fields: An organizational history of the US radio broadcasting industry. Administrative Science Quarterly, 36(3), 333–363.

Levi-Strauss, C., 1967. The Savage Mind. Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press.

Lincoln, Y. S., & Guba, E. G. (1985). Naturalistic inquiry. Beverly Hills, CA: Sage.

Lounsbury, M. (2002). Institutional transformation and status mobility: The professionalization of the field of finance. The Academy of Management Journal, 45(1), 255–266.

Lounsbury, M., & Crumley, E. T. (2007). New practice creation: An institutional perspective on innovation. Organization Studies, 28(7), 993–1012.

Maguire, S., Hardy, C., & Lawrence, T. B. (2004). Institutional entrepreneurship in emerging fields: HIV/AIDS treatment advocacy in Canada. Academy of Management Journal, 47(5), 657–679.

Martin, J. L. (2003). What is field theory? American Journal of Sociology, 109(1), 1–49.

Neirotti, P., De Marco, A., Cagliano, A. C., Mangano, G., & Scorrano, F. (2014). Current trends in Smart City initiatives: Some stylized facts. Cities, 38, 25–36.

Reay, T., & Hinings, C. R. (2009). Managing the rivalry of competing institutional logics. Organization Studies, 30(6), 629–652.

Ritchie, J., & Lewis, J. (2003). Qualitative research practice: A guide for social science students and researchers. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

Scott, W. R. (2001). Institutions and organizations. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

Scott, W. R., Ruef, M., Mendel, P., & Caronna, C. (2000). Institutional change and organizations: Transformation of a healthcare field. Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press.

Suddaby, R. (2010). Challenges for institutional theory. Journal of Management Inquiry, 19(1), 14–20.

TEPCO. (2015, August 7). TEPCO: Smart meter system operations status. Retrieved from http://www.tepco.co.jp/en/announcements/2015/1257023_6902.html. Accessed on April 15, 2016.

Tranos, E., & Gertner, D. (2012). Smart networked cities? Innovation: The European Journal of Social Science Research, 25(2), 175–190.

Tushman, M. L., & Anderson, P. (1986). Technological discontinuities and organizational environments. Administrative Science Quarterly, 31(3), 439–465.

Wright, A. L. (2009). Domination in organizational fields: It’s just not cricket. Organization, 16(6), 855–885.

Zietsma, C., & Lawrence, T. B. (2010). Institutional work in the transformation of an organizational field: The interplay of boundary work and practice work. Administrative Science Quarterly, 55(2), 189–221.

APPENDIX

Table A1. Types of Participating Organisations in the Research.