FINDINGS

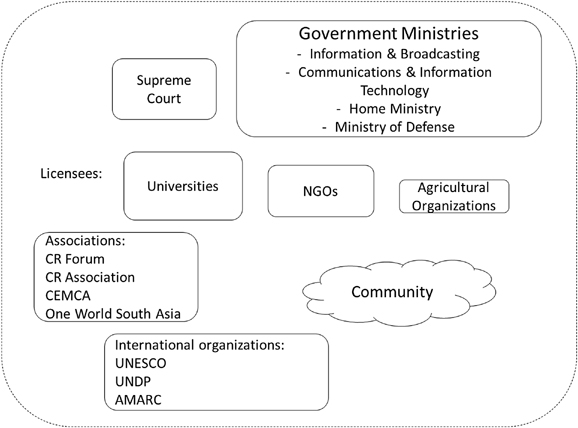

We first describe the key actors in the field of community radio (Fig. 1). Then, we present our findings on the various stages of the field. In particular, we describe how an emerging community logic was articulated and the interactions that took place between the emerging community logic and dominant logics in the field, that is state logic and development logic.

Key Actors in the Field of Community Radio

The key actors in the field of community radio in India (see Fig. 1) are as follows. The first actor can be considered as the government of India; more specifically, this comprises four ministries: Ministry of Information and Broadcasting; Ministry of Communication and Information Technology; Ministry of Defense; and Home Ministry. Independent of the government but in close interaction with it is the judiciary, specifically the Supreme Court that delivers judgments based on petitions filed by activists regarding the policies adopted by the government for community radio. Another set of key actors comprises community radio support associations, forums, and activists. These are actors who have played various roles in the build-up of the field as we delineate later. Finally, there are the licensees who actually run the community radio stations, comprising mainly of educational institutions and NGOs along with a few agricultural institutions.

We see the role of activists as significant in making space for community radio from the beginning and consider them as a core group for this study. However, these activists have been active on and off at different stages, and have wide variation in their approach and motivations. They cannot be considered as one homogeneous group struggling together for a clearly defined cause even though there are some common aspects across them. Reflecting on this, an early activist describes the beginnings of the struggle as follows:

There was this [Activist A] who actually filed the public interest litigation … and others played a stellar role. But they were very antagonistic with an activism-based kind of cause. [Activist B] believed in working with the government. [Activist C] was somewhere in between. [Activist D] was again extremely confrontationist. There were quite heated debates and there were [varied] interest groups. (I-1; see Appendix B for interviewee codes and descriptions)

Overall, there were several activists and interest groups around the issue of community radio. These different interests groups often diverged on key aspects, for example, some collaborating with and others more confrontational toward the state. Further, as mentioned in the empirical context, the communities on the ground were not organized to lead any movement in a bottom-up manner. Our observations suggest that this situation contrasts somewhat with that of social movement studies (Greve et al., 2006), though occasionally the word “movement” is used in our context. While there was macro-level coalescence, it was not in the form of movement(s) but rather can be understood better as the prevalence of several logics in the field. Our findings show more details of this aspect.

Dominance of State Logic: Problematizing by Activists

The trigger for the community radio initiatives in India can be traced to February 1995 when the Supreme Court (the apex court in India), in a landmark judgment, declared that airwaves constitute public property and must be utilized for public good. Until this time, radio in India was solely operated by the government as public service broadcasting. As a result of the judgment, several media professionals, policy actors, and civil society organizations gathered in Bangalore in September 1996 to discuss the scope for community radio in India. They signed the Bangalore Declaration, which subsequently became the basis of advocacy for community radio policy. Beyond India as well, community radio broadcasting was recognized as an essential public service in the Milan Declaration on Communication and Human Rights in August 1998.

In May 2000, the Indian government interpreted the 1995 Supreme Court judgment as a shift from government monopoly over radio toward commercial auctioning of airwaves to private players. While this move of the government was seen as important, the advocates for community radio argued for an interpretation of the judgment that would allow “a three-tier” broadcasting structure for radio; this later became known as the Pastapur Initiative (see Table 1 for timeline of events). An activist draws the links between these events:

…[the] community radio movement goes back to the Supreme Court’s judgment of 1995 which said airwaves are public property for public good. And shortly after that the first advocacy consultation in this country argued cogently for the three-tier media set up: public, private and community. We did have these ground-level advocacy moves … there were 4 or 5 community based NGOs who actually played quite an important role in taking this forward. (I-7)

These advocacy efforts for a broader interpretation of the Supreme Court judgment are corroborated by a policy actor, who also highlights the government’s reluctance and “nervousness” in allowing community radio stations:

… the interpretation [of supreme court judgment] made by the department of telecommunication officials is that the CR [community radio] license spectrum should also be auctioned. While the FM band is auctioned, CR is a not-for-profit spectrum. So there was a lot of advocacy and campaign that led to this being reviewed; and still the officers within the ministry are … shy of taking a call on making this interpretation that this [CR] is distinct from any other resource. (I-18)

At a time when the liberalization, privatization, and globalization reforms had been introduced in India, the government did not want to make a distinction between commercial radio and community radio and initially attempted to apply the same interpretation of commercially “auctioning” off the spectrum for both. Avoiding recognition of the “nonprofit” and community-oriented nature of community radio would ensure that non-state actors would be unable to “encroach” on what was traditionally seen as the government’s space. The reasons for the government’s nervousness in this regard are evident from this historical background on the role of the state in India since colonial times:

Indian telegraphic act is one of the most archaic laws in the country which was basically a British formulation; they thought so and it is still true – the national media is very critical to control the masses. So they didn’t want everybody up and running radio stations, and somehow our government after independence borrows the same notion and it still fears [losing control].(I-1)

The activist here points to the colonial history of India and the continuing domination by the Indian state using the colonial laws even after independence. The government is apprehensive of letting go of the control over media by allowing a third space apart from the government-controlled and the commercially controlled spaces. This pattern of control can be understood as the manifestation of the dominance of a state logic in the context of media in India. Clearly, as seen in the quotes above, the dominance of state logic became increasingly problematic from the perspective of community radio activists (see Table 2 for more examples of this pattern). These problematic aspects of the state logic spurred efforts among activists to articulate a community logic to create space for community radio in India. We describe this next.

Table 1. Timeline.

Time |

Event |

February 1995 |

Supreme Court Judgment: Airwaves constitute public property and must be utilized for advancing public good |

September 1996 |

Bangalore Declaration: Various actors involved with policy, media and civil society organizations come together in Bangalore to study how community radio could be relevant in India. “Bangalore Declaration” is signed for community radio advocacy |

August 1998 |

Milan Declaration on Communication and Human Rights at the 7th World Congress of the World Association of Community Radio Broadcasters: Supports international recognition of community broadcasting sector as an essential public service |

May 2000 |

Commercial FM licensing phase-I: Commercialized broadcasting through auctioning is started as change from government monopoly on radio |

July 2000 |

Pastapur Declaration: Calls on the government to create a three-tier structure of broadcasting in India: nonprofit community radio in addition to state-owned public radio and private commercial radio. |

December 2002 |

Community Radio guidelines released by Ministry of Information and Broadcasting: Licenses restricted to established educational institutions |

January 2004 |

Telecom Regulatory Authority of India (TRAI) is made broadcast regulator |

May 2004 |

Ministry of Information & Broadcasting, UNDP, UNESCO hold workshop in New Delhi: Enabling framework for community radio |

August 2004 |

TRAI consultation paper on community radio |

December 2004 |

TRAI recommendations on community radio |

July 2005 |

Commercial FM licensing phase-II |

November 2006 |

New Community Radio Policy by cabinet: Community radio licenses allowed for nonprofit organizations. Restriction on news broadcast; permission to use advertising. |

June 2008 |

First community radio license given to a nonprofit organization |

October 2008 |

First nonprofit community radio station starts in Pastapur on International Day of Rural Women |

June 2012 |

132 operational community radio stations (including 41 operated by NGOs) |

May 2015 |

180 operational community radio stations (including 66 operated by NGOs) |

April 2015 |

Ministry of Information and Broadcasting order to civil society operated community radio stations asking for stations’ daily content (to monitor the stations) |

March 2016 |

191 operational community radio stations (including 70 operated by NGOs) |

Sources: Secondary data – archival sources (CR support organizations, government websites, news. See Appendix A for more information).

Table 2. Dominance of State Logic: Problematizing by Activists.

Theme |

Logics |

Representative Quote |

Context |

Inadequacy of state logic |

Still large parts of the country continue to be media dark ….We feel that in such remote areas, to address the communication rights issue, the best platform would be community radio which can address locally relevant issues rather than a market [model] or a state [controlled] public service broadcasting. (I-4) |

Lack of political will |

Problematic state logic |

I don’t think any of the [political] parties are actually looking at enabling the rural people because it will start challenging the mainstream media … It [community media] will challenge how people understand social issues. I think it won’t be encouraged because … I think [political process has] been hijacked by a few elites in India. (I-2) |

Beginnings of advocacy |

Dominance of the state logic |

Initially, [activists] wanted to get the spectrum away from government [control]…[arguing] it was our fundamental right, [while as per] the government anything which has a transmission of above 1 hertz [necessitates] a license. [Activists challenged that] are you saying that for every tube light [that has transmission frequency above 1 hertz] I need to get a license? That is where they were able to say that technically you [government] are wrong. (I-3) |

Objectives for advocacy |

Perceptions of dominance of the state logic |

[There is a perception that] whatever comes from the [state controlled public broadcasting], be it TV or radio, is the authority. [Marginalized] people … don’t hear their voice in the airwaves and they cannot have their issues discussed in the open except for panchayat [village level committee]. I think that’s the community radio station’s role to play. As a democracy, it (community radio) is by the community, for it and of it. (I-3) |

Early discussions for advocacy |

Mobilizing support to contest the domination of the state logic |

[Government] did the de-monopolization of airwaves and started auctioning FM frequencies to the highest commercial bidders. [Activists] resisted [interpretation of] public property as private property … [about] 2,000 of us met in Hyderabad under the invitation of UNESCO and we had friends from other parts of Asia … where … a very clear articulation for a need of third tier of broadcasting in India [was achieved]. (I-5) |

Advocacy |

Advocacy for community logic |

[NGO name] played a very critical role, particularly earlier which led to the opening up of the airwaves for community-based organizations who were interested in having a radio station of their own … We did have these ground level advocacy [efforts] … there were 4–5 community-based NGOs that actually played quite an important role in taking this forward. (I-7) |

Experimentation and Articulation of Community Logic

In a context where the dominance of state logic was being seen as problematic, community-based organizations started developing initiatives in line with a community logic toward their goal of realizing community media. Initial forays in this regard involved experimental efforts that tried to achieve aspects of community media even when community radio was legally not allowed; later efforts directly articulated the need for media that would be “voice for the voiceless.” One activist describes an early experiment with educational radio in this regard:

In 2001, IGNOU [Indira Gandhi National Open University] organized a consultation … which resulted in “the New Delhi Declaration.” Shortly after that, Gyanvani [a public service broadcast state FM radio] was operationalized; although an educational radio, it was actually based on a popularity model with at least 50% of the programs made with active community support and participation. (I-7)

As the activist mentions, an experimental initiative was taken in the above example to include community-generated content, which would be in major contrast to the expert-generated content typically broadcast in public service broadcasting. There were also early initiatives that showed how useful community media could be, such as those by NGOs who used media toward their developmental goals:

In 2000, at that time we did not have the community radio policy in India, we had a few initiatives that we used to call the Big 4. NGOs working in social change were using media to bring in that development. (I-6)

An NGO also actively took up action research efforts to show the importance of community radio:

[NGO name] has also, since then, been associated with a third level, promoting and deepening research initiatives that tried to show how community radio could make a difference. Participation is facilitated by very close connection to the field where researchers would work along with [NGO name] and in cases where ethnographic action research was put in place. (I-7)

These initial efforts toward highlighting the importance of community logic in media helped provide the basis for a clearer articulation of the need for a “voice of the voiceless,” that is, media that would be for the marginalized communities. Several actors in the field recount and articulate this community logic aspect in describing their support for community radio stations. As an early activist and NGO member puts it:

Mainstream media has abandoned the voice of the poor completely. I think community radio has to be the voice of that section. Of course, community radio was needed largely because where were you hearing the voice of the farmer? It’s not there on TV, it’s not in mainstream national papers. The role of community radio is to bring together weaker sections so they have a voice. (I-19)

Similarly, the lack of voice of community members, that is, “voice poverty” is brought up as an essential reason for having community radio stations:

I will say that there is poverty and there is voice poverty. The root cause of poverty is voice poverty, people don’t have a voice to demand their rights. This lack of rights keeps them in the condition they are in. So, given this “logic” we should have some radio stations in these areas. (I-5)

Another community-focused experimental initiative is described as a means to “demonstrate” the need for such community radio to the government:

One of the initiatives we tried in the absence of legitimacy [for community radio] was the use of what we called cable radio. But actually it was cable narrowcasting to the nearby villages. Initiatives like this demonstrated to the government the need for something like community-based radio to promote transparency, accountability and also deepen the development agenda. (I-7)

After some initial experimentation, the efforts continued on the articulation of the new community logic. In Table 3, we present more examples of this pattern: the articulation of community logic in support of community radio stations. Broadly, community logic has been articulated as focusing on the voice of the voiceless communities, marginalized communities, and communities that do not have access to mainstream media to voice their opinions.

Table 3. Articulation of a New Logic: Community Logic.

Theme |

Logics |

Representative Quote |

Voice of the voiceless |

Articulated community logic |

… you can [invite] the collector of that area [to community radio station] and ask people to call you … so she can discuss the problems [related to] the ground realities that people are facing over there. I think that would be the major purpose of a community radio. (I-8) |

Equal voice within community |

Articulated community logic |

But the cornerstone of this is does your community radio give equal voice to each and every member of its community, particularly those who are marginalized and excluded. (I-7) |

Voice of the voiceless |

Articulated community logic |

For me, the most important responsibility of the community radio is to give voice to the voiceless … So, people who don’t have any access to share their view get community radio to air their views … The basic thing is to get their voices heard by the public. (I-9) |

Voice of the marginalized |

Articulated community logic |

Whether women are participating or not … Marginality is a very big thing … are the marginalized groups getting included or not? Participation [of marginalized should be] an overarching rule. (I-6) |

Community participation |

Articulated community logic |

… unless there are voices and participation from the community, [community radio is] not sustainable from a social point of view.… discussions which would otherwise be confined to 5–6 people would be talked about by 100s or 1000s of people in the community … Another thing that makes it more interesting is accountability- you can hold a lot of [government officials] or the heads of villages accountable to a lot of issues. (I-3) |

Expert driven versus people’s knowledge |

Articulated community logic against state logic |

information [dissemination] is still very expert driven, very policy-makers driven, top down. It does not respect people’s knowledge, [their ability] to produce information. We are saying that people have the knowledge, one needs to respect people’s knowledge. (I-5) |

Community governance |

Articulated community logic |

In an ideal world CR should be run by the community … They can do what they like, have a certain freedom of voice. A community should be tuning [wanting to] know what is actually happening in my community. Why the road is still not built? Why is this procession happening? Happy events, sad events, whatever. But for it to have credibility [there should be] ownership of the entire community in the sense that this is ours. (I-12) |

Voice of the marginalized |

Articulated community logic |

[Community radio should be for] the communities who do not have access to the communication facilities, communities whose voices are not heard, who need to be given priority over others. (I-6) |

State Logic Used to Restrict Community Logic

As the community logic was gaining strength through articulation by activists, NGOs, and other external supporters such as UNESCO and UNDP, we find that the state logic was used to restrict the emergence of the community logic in various ways. As a result of advocacy efforts by activists toward articulating a community logic, the Ministry of Information and Broadcasting released the first set of community radio guidelines in December 2002. However, according to these guidelines, licenses were restricted only to educational institutions in urban areas that already had access to other media. An academic media researcher explains how attempts were made to keep radio restricted only to “established educational institutions” which would likely pose less challenge to the dominant state logic:

The government opened licenses up for what we call established educational institutions. They opened up campus radio and called it community radio. Some of us had problems with that … many of us were talking about rural India. We were talking about dark areas of media, the under-represented community in the media and what the government did was to provide access to the already privileged communities. (I-5)

A consultation paper of 2004 by the Telecom Regulatory Authority of India (TRAI, a government body) clearly outlines these restrictions:

The present guidelines permit grant of licenses for setting up Community Radio Stations only to educational institutions. Hence, community radio licenses are not available to community cooperatives, local self-help groups, NGOs, social organizations, trade unions, associations and other non-commercial groups. (TRAI Consultation Paper, 2004)

As the above quote shows, the government was apprehensive of allowing licenses to community-based organizations and accordingly restricted the licenses to urban educational institutions. The so-called “community radio” run by these educational institutions was popularly known as campus radio, as it did not involve any community that lacked access to other media. In the government’s view, the students on campus were considered the community for these radio stations. After prolonged and persistent efforts from various activists and NGOs, four years after the first policy guidelines on community radio allowed licenses to educational institutions in 2002, new guidelines in 2006 allowed licenses to NGOs. A government consultant and NGO member recounts these time restrictions:

So even when they opened the licensing, they initially only opened it up for the educational institutions and there was a good four year gap before a review of that policy took place and when NGOs were allowed to apply for licenses. (I-18)

The licenses for community radio subsequently given to NGOs were however not without restrictions. There were restrictions in terms of eligibility criteria for licensing such as age and turnover of the NGO. A media professional talks about this as a limitation:

Policy making is in the hands of the government. You can make the procedure a little bit easier for the people because right now you must have a 7 year old NGO or institution; only then you can get this license. So there is a certain age limit. (I-8)

Another major restriction was on the content: the broadcast of news or current affairs on community radio stations was banned. One of the academic media researchers talks about the “double standards” nature of these restrictions, where on one hand community radio was being allowed and on the other hand the community logic was being restricted in the generation and broadcast of community-oriented content:

When you have a platform like this where people actually feel that they can talk about issues that matter the most to them, the current affairs clause [in state policy] becomes a very double standard thing … like you need to cater to the community but you still can’t talk about current affairs. Sometimes the current affairs are of that community – so then what do you do? Then there’s a very thin line. (I-6)

A public interest litigation was filed against this ban on the broadcast of news and current affairs. In 2014, the Supreme Court issued a notice to the government on the matter. In response, continuing the approach of restricting community logic, the Ministry of Information and Broadcasting recently allocated large sums for developing infrastructure to monitor radio stations and thereby ostensibly address security concerns (Dhawan, 2014). A further restricting measure of the government has been that community radio stations need to throw open their content to state bodies on a daily basis for scrutiny (Raman, 2015). Overall, though community logic emerged in the field through articulation by various actors and accordingly community radio stations became legally allowed, the actors aligned with the state logic – most prominently various arms of the government – acted to restrict the community logic in practice in various ways. In Table 4, we provide more findings to explicate this pattern.

Table 4. State Logic Used to Restrict Community Logic.

Theme |

Logics |

Representative Quote |

Public versus private property; ban on news |

Emerging community logic restricted by dominant state logic |

[Apex Court] judgment talks of the need for community to use community radio … to promote the right to communicate. However, [in government] policy guideline … the whole issue of article 19 which is the right to communicate was compromised by the … ban on news. (I-7) |

Consultation |

Emerging community logic overcomes resistance from dominant state logic |

[NGO name] was invited to [a] conference in 2004, on creating an enabling environment for community radio. By that time, the government itself had done some rethinking [on] opening up of airwaves. So right up to 2006–2007, [NGO name] actually continued [advocacy], from the time of the guidelines for opening up of airwaves till enabling NGOs to be eligible for licenses. (I-7) |

Community radio versus Campus radio |

Emerging community logic restricted by dominant state logic |

I think educational institutes should not be given the license to run this [community radio]. Maybe if we have any small time newspapers or magazines of the local areas, they can give a daily capsule of what’s happening in their locale and that can be broadcasted [using community radio]. (I-13) |

Ban on news |

Emerging community logic restricted by dominant state logic |

… we are looking at is the ban on news … all indications seem to point that the Supreme Court will say that news on radio cannot be banned and the government will be forced to make these kind of strange announcements on how they will manage the community radio. It becomes one more reason for the Home Ministry to say we can’t [encourage community radio]. (I-12) |

High license fees |

Emerging community logic restricted by dominant state logic |

[License fee] is quite [high], quite a burden for small organizations, but some government universities paid the higher fee because they just follow mandated orders; they didn’t campaign but they tried to see it reduced because they had to get it approved by the board, some lacked budgetary provisions for it. (I-14) |

Conflict areas |

Acceptance of emerging community logic with elements of dominant development logic |

… there were no licenses issued in Jharkhand, Chattisgarh[areas with armed insurgency movements]. There is no [community radio] in the North East (part of India) and this anxiety is based on a security kind of logic. I have been arguing on various forums that precisely in those regions we need community radio. So if you go by the government discourse, you see that community radio is more like a mode of development [rather than for community agendas per se]. (I-5) |

Development Logic Used to Appropriate Community Logic

While supporting the emerging community logic, several activists – particularly those from NGOs working on a development agenda – articulated community logic by describing how it would help serve their development agenda. As mentioned by an NGO professional, this situation was reflected in the policy guidelines for community radio licensing:

In India, community radio can be owned by the NGO and not directly by the community. So, when the government of India liberalized the air waves and decided to decentralize the radio to community, it was done through NGOs. (I-16)

Thus, while licenses were opened to NGOs, communities themselves did not have direct access to a community radio license. This is important because although NGOs may work for marginalized communities, they often do not have representation from these communities. A media consultant active in the community radio space further explains how NGOs aligned with a development logic came to appropriate the community logic:

In the very early days of our activism, to find some traction with the government, we positioned community radio as a development tool. It was a very big mistake. The guidelines, the policy and everything is circumscribed by this developmental paradigm. The reason why the NGOs are coming to community radio is because NGOs claim to be developmental NGOs. So, it is sort of carved in stone in the policy that you have to talk agriculture, health, women’s empowerment and all that stuff in order to get a license … (I-15)

Thus, these early attempts at articulating community logic with development logic led to policies that put NGOs first. As the media consultant elaborates further, this may be fine to a point but increasingly the NGOs seemed to be putting development logic first and community logic was seen only as a means to create a “mouthpiece for the NGO” to reach the community:

Community radio necessarily belongs to the community and should be based on what community desires and not what [NGOs] desire. Many NGOs have great interest in expanding their reach within community. But in practice, when it becomes totally conceding [to NGOs] and nothing else, this radio becomes a mouthpiece for the NGO and that’s all. (I-15)

As the licenses are only available to educational institutions and NGOs and not directly accessible to marginalized communities, there are questions on whether this serves the purpose of community radio as was articulated by various actors in terms of community logic. An activist raises this question as follows:

So the larger question is – is it really the voice of the voiceless or is it the people with a voice finding a different medium to voice their opinion. I am yet to see a truly representative community radio station. (I-1)

Overall, the early efforts at combining development logic with community logic during advocacy and subsequent policies making marginalized communities ineligible for obtaining licenses for themselves has led to a unique situation. While community logic has emerged in the field, it has been increasingly appropriated by a development logic, particularly by actors such as NGOs who are closely aligned with development-related activities. In Table 5, we provide more details on these findings.

Table 5. Development Logic Used to Appropriate Community Logic.

Theme |

Logics |

Representative Quote |

NGO radio versus community radio |

Emerging community logic combined with dominant development logic |

Pro [of community radio license being given to NGOs] is that the NGOs are already working in the community and can take care of it; but the con is that they have their own agenda which they will try to attain through the community radio. (I-16) |

NGO working for a long time |

Emerging community logic combined with dominant development logic |

NGOs have done some amount of work in or have some interest in communication. Either they have used print media or they used video … for their development work. So in a sense the [NGOs] who have applied and obtained licenses and have started the radio stations, are already familiar with some mode of communication. (I-14) |

Sustainability a challenge |

Problematic combination of emerging community logic with dominant development logic |

… major challenge is the sustainability of the community radio stations and it’s really crippling. NGOs rely on external funding, and a portion of that goes down to community radio stations. If [this funding is withdrawn] then those community radio stations would just fall apart so I think sustainability is a huge challenge. (I-17) |

NGO radio versus community radio |

Dominant development logic uses emerging community logic |

… for instance, an NGO working in the field of affordable health care has a community radio but [the mainstream media is not] interested in writing about the issue. So, for [the NGO], this is a brilliant way of talking about the work that they’re doing and the issues they’re working with. (I-2) |

NGO radio versus community radio |

Dominant development logic takes over emerging community logic |

I think somewhere the agenda of NGO or donor agencies is taking over where we need to be cautious. I have started talking about NGOvization of community radio which is dangerous and I don’t think we have a choice. Because we need NGOs, community based organizations to run radio stations, to do some hand holding, capacity building (I-5) |

Communication rights |

Extension of emerging community logic beyond elements of dominant development logic |

I think overall the community radio [activists are] to blame because they have not networked with other [activists] in the country to build the bridges. I am sensing that … the course needs to shift from development to rights, communication rights … other rights that are being articulated by those other [activists]. I think we have to see how community radio can dovetail into those other [activism]. (I-5) |

DISCUSSION

Our findings show the presence of three logics in the community radio field, namely community logic, state logic, and development logic. The three logics we observe are broadly similar to earlier identification of such logics in prior literature, but we also draw out a few new and interesting aspects of these logics based on our context. While the state logic is broadly understood as a functional logic based on bureaucracy and democratic participation (Thornton et al., 2012), our focus on the interplay of this logic with an emerging logic in the community radio field emphasizes its potential dominant and problematic side. Community logic is based on shared commitments, reciprocity, and connections among a geographically bounded collective of people (Thornton et al., 2012). This is similar to the emerging community logic we observe in our context, with the additional observation that the key communities referred to are typically marginalized communities in areas with limited access to media; community logic may thus be more crucial and yet challenging for such marginalized communities to organize around. Development logic has been less studied and may not have a broad commonly accepted understanding in the literature. However, it has been focused upon in some studies as a broad principle directing activities toward poverty alleviation and other social benefits (Battilana & Dorado, 2010; Kent & Dacin, 2013). This is quite similar to what we observe in our study. Additionally, in the context of the community radio field, we also highlight how the development logic may play a problematic role in appropriating an emerging logic in addition to its commonly understood functional role.

Our findings allow us to conceptually delineate key stages in the emergence of a new institutional logic in a field. As Padgett and Powell (2012) argue, there are two fronts to the emergence problem. First, there is the question of where novelty comes from and second is the question of how novelties get recognized as new social realities. Our findings show that novelty comes from problematizing dominant logics and emerges in friction with dominant logics. Recognition for the new logic in the field comes about through the legal rulings allowing organizational forms that reflect aspects of the new logic, and also through some eventual acceptance of the new logic from various actors including those aligned with other dominant logics.

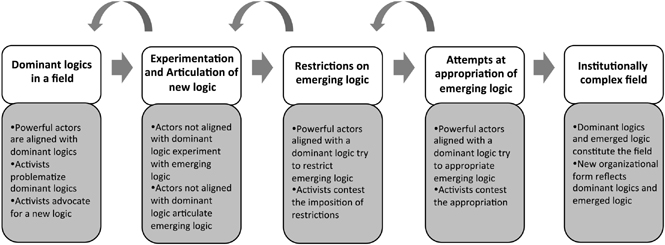

In the first stage of the emergence process, key actors problematize dominant logics in a field (box 1 in Fig. 2); this leads to experimentation that is in line with a new logic followed by more wide-scale articulation of the new logic (box 2 in Fig. 2). In our case, activists problematize the dominant state logic in the media field and a few experimental initiatives are launched that focus on community-based media. This builds into articulation of the new community logic through references about the purpose of community radio such as how, in regions with limited access to other media, such media could be the voice of the voiceless, provide freedom of expression, promote local culture, and allow diversity of voices – especially those of marginalized and oppressed groups. In general, all the stages we identify may involve some iteration, as shown by the curved arrows between boxes in Fig. 2.

At each stage, the emerging logic is influenced by dominant logics through restriction or appropriation, and in turn, dominant logics continue to be problematized to make space for the emerging logic (boxes 3 and 4 in Fig. 2). In our case, the actors aligned with the dominant state logic – particularly government ministries – try to use the logic to restrict the emerging community logic and thereby control access to community media. On another front, the development logic is used by NGOs and activists aligned with them in attempts to appropriate the community logic; this is reflected in the finding that the community radio is run as the mouthpiece of development-based NGOs rather than as a vehicle for expressing the voices of marginalized communities. As a result of the interaction between the emerging logic and the dominant logics through actors aligned with these logics, the field of community radio is shaped into an institutionally complex field comprising the new as well as the established logics (last box in Fig. 2). The new social reality of the community logic is recognized most visibly through legislative acts in a manner similar to that described in prior studies (Ruef, 2000) and the resultant licensing process that allows community radio stations to come into being. Our study thus shows the connections between actions of various social actors, emergence of an institutional logic, thereby shaping of a new institutionally complex field, and the (early) organizational outcomes of this process.

Prior research has looked at emergence of institutional fields and institutions (David, Sine, & Haveman, 2012; Lounsbury, Ventresca, & Hirsch, 2003; Purdy & Gray, 2009). Our work is similar and is in the tradition of emergence of neoinstitutional scholars who have focused on “particular historical cases” (Ruef, 2000, p. 659). We extend this literature by showing how an institutionally complex field is formed through the emergence of a new institutional logic. Our focus on the emergence of an institutional logic, rather than the field per se or the organizational forms in the field, provides a unique vantage point to understand emergence in institutional studies. The burgeoning research on the institutional complexity of fields (Greenwood et al., 2011) suggests the need for more nuance in understanding the formation of an institutional field. We thus suggest a focus on the emergence of an institutional logic as a macro-level social phenomenon that has functionalities quite different from that of the micro-level actors whose collective interactions lead to the logic. The notion of an institutional logic as a macro-level social object is analogous to the idea of “collective cognition” as a macro-level social reality that displays functionality different from that of its micro-level constituents (Page, 2015). Such an intervening focus helps us bring attention to an important macro-level and helps us better understand the process of the eventual formation of a complex field.

In our case, we see these aspects through the emergence of a community logic, which is distinct from the established logics of state and development; together, the three logics create the new social reality of an institutionally complex field around community radio. Further, the organizational form of community radio that develops in this field reflects this complexity in as much as it has features conforming to all three logics. Thus, the community radio stations are based in the community but are typically run on a mainstream development model with serious constraints imposed by the state.

Earlier studies have looked at institutional logics mostly as institutionalized and taken for granted (David et al., 2012; Schneiberg & Lounsbury, 1998). Our focus on emergence of a logic helps us add to this literature by also showing the problematic side of dominant logics in addition to their functional side. Thus, our findings also provide an opportunity to draw attention to normative evaluation and power dynamics in the context of how logics shape an institutionally complex field. We suggest that the problematizing we observe happens along the lines of normative evaluation, that is, actors “begin to question the institutional status … because they consider that some aspect of the status quo is ‘wrong’ or ‘unfair’” (Cloutier & Langley, 2013, p. 363). Actors in the field evaluate the dominant state logic in various ways, particularly highlighting how media based on that logic is not serving several sections of society, thereby problematizing the logic. Accordingly, a more “morally sound” logic is developed – through experimentation and then widespread articulation – under the expectation of serving society better. In our context, this means a logic that allows for shaping the field with a focus on communities, particularly those that do not have access to other forms of media.

This problematizing and evaluation is closely tied to issues of power. Power in our context is visible when we look at actor alignment with specific logics – that is, which actors stand to gain the most if the field is organized around the principles of a specific logic. This alignment of actors with dominant logics or the emerging logic provides insights into power dynamics. Actors aligned with the dominant state logic, most prominently those in various ministries of the government, can be considered to have command posts (Reed, 2012; Zald & Lounsbury, 2010) from where they attempt to preserve their power by restricting the emergence of a potentially competing logic. Similarly, key actors (NGOs in our case) derive their power in the field through legitimacy and authority in terms of speaking on important (development) issues (Lefsrud & Meyer, 2012; Riaz, Buchanan, & Ruebottom, 2016). Such power allows the actors to shape the field to their advantage, manifested in how NGOs appropriate community radio stations to serve the development logic with which they are closely aligned.

In sum, powerful actors aligned with dominant logics act to restrict and appropriate the emerging logic at various stages during the emergence process. Eventually, the organizational form that results in the institutionally complex field has the marks of this ongoing power struggle underlying the interplay among the three logics. Thus, the community radio stations that come into being, while reflective of an emerged community logic in some respects – particularly in terms of their location in geographic communities, are also severely restricted by various regulations including those on limits around content and licenses, and by some accounts end up serving a key role in the developmental efforts of NGOs. Overall, we suggest that considering the intertwinement of actors and their interests with certain logics in the field and accordingly paying attention to their roles in contestation among logics can provide an opportunity to observe how power plays a role in the formation of complex institutional fields. Such an approach may help address the lack of attention to power in neoinstitutional studies (Munir, 2015; Suddaby, 2015).

A focus on logics also helps us contribute to the emergence literature by showing the friction-laden nature of the emergence process. The interplay of the emerging logic with established dominant logics shows how at each stage the emerging logic is shaped and constrained by what came before it. We argue therefore that our findings turn the attention of emergence theorists to more sociological processes that are less “pure” or neutral than those identified in the biological or chemical sciences (Padgett & Powell, 2012). In the social realm, emergence may take place in a more “contaminated” and contested manner than how it is currently theorized in the emergence literature (Padgett & Powell, 2012; Powell & Sandholtz, 2012). Novelty does come about, and reaches scale and recognition; but the dependence on the past (Ocasio et al., 2016; Thornton et al., 2012) and the various ways in which the past influences the new social objects is crucial and is reminiscent of our existing understanding in neoinstitutional theory about the importance of fateful interaction among constituents in an institutional field.

We suggest that our approach may be useful to study emergence in a variety of contexts. The specific logics may be different, but such struggles between emerging and established dominant logics are likely common. As pointed out by Greve et al. (2006), the macro-level contest in their study of microradio in the U.S. context was between capitalism and democracy because the concentration of cultural production was with commercial chains. This contrasts with our context where the control of media was with the state, but points to the general usefulness of attention to struggles at an intervening macro-level (logics), albeit with the specific logics at play differing according to context.

Thus, considering emergence with a logics perspective needs close attention to the history and mix of existing logics in a particular context. For example, our context in India had a development logic in addition to state and community logic and thus a consideration of only one set of protagonists against another set of antagonists (as is more common in social movement studies) may not have captured the nuanced struggles. Instead, considering the non-unified nature of activism by parties with a variety of interests, including those seeking an appropriation of the emerging logic for their dominant logic, allowed for a richer understanding. Extending this approach across the global south, such attention to development logic may be necessary in several countries. The emergence of new logics in several non-western contexts may have lesser interaction with existing market logic than typically found in western contexts. A unique example would be China, where market logic can be seen as subservient to state logic even though both are well established, and accordingly the emergence of any new logics such as around social issues or community initiatives has to be seen in this complex context.

Beyond the traditionally identified logics (Thornton et al., 2012), our understanding of field formation and emergence may gain from attention to logics that have previously received less investigation in the literature. For example, the increasing recognition of a “financialization” logic in the United States (Davis, 2009; Van der Zwan, 2014) suggests a historically unique context where phenomena of field formation and change may be better understood by including such a logic in the analysis. In such contexts, even socially oriented organizations such as nonprofits are arguably subject to a financialization logic (Jenkins, 2015), and therefore considering a perspective of struggles among logics is crucial. In contrast, emergence and field formation around socially oriented organizations in parts of continental Europe (Borzaga & Defourny, 2001; Defourny & Nyssens, 2010) may proceed under a different configuration of logics, with lesser influence of financialization logic.

How our perspective applies to a context may also depend on whether a new logic is an instantiation in that particular context of a logic available elsewhere or is novel across contexts (Bertels & Lawrence, 2016). In our case, due to the fact that community radio is well established in some other countries of the world, we see occasional influence from outside India through international actors interacting with local actors (see Timeline in Table 1). We suggest that attention to broader patterns of global influence, such as through colonialism, imperialism, and transnational institutions, may be helpful to untangle this aspect. Future research may tease out more aspects of how emergence is subject to such influence across contexts.

In conclusion, our article calls for a deeper conversation between sociologists and emergence theorists, with likely influence going in both directions to refine and add to our theoretical understandings of both the literatures. Similar to the conversation reinvigorated by Page (2015) to draw the interest of sociologists toward complexity, our study helps draw the attention of neoinstitutional theorists to emergence processes and also helps emergence theorists add a sociological flavor to emergence studies.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We would like to acknowledge the Research Grants Council of Hong Kong (GRF Grant: PolyU 548210 and PolyU 549211) for their funding of this research. We would like to acknowledge Babita Bhatt, who was co-investigator on GRF Grant (PolyU 549211), for her help in early stages of data collection and transcription. We also acknowledge assistance provided by Anusha Satturu at UMass Boston.

REFERENCES

Aldrich, H. E. (2011). Heroes, villains, and fools: Institutional entrepreneurship, NOT institutional entrepreneurs. Entrepreneurship Research Journal, 1(2), 1–6.

Alford, R. R., & Friedland, R. (1985). Powers of theory: Capitalism, the state, and democracy. New York, NY: Cambridge University Press.

Bartley, T. (2007). Institutional emergence in an era of globalization: The rise of transnational private regulation of labor and environmental conditions. American Journal of Sociology, 113(2), 297–351.

Battilana, J., & Dorado, S. (2010). Building sustainable hybrid organizations: The case of commercial microfinance organizations. Academy of Management Journal, 53(6), 1419–1440.

Bertels, S., & Lawrence, T. B. (2016). Organizational responses to institutional complexity stemming from emerging logics: The role of individuals. Strategic Organization, 14(4), 336–372.

Besharov, M. L., & Smith, W. K. (2014). Multiple institutional logics in organizations: Explaining their varied nature and implications. Academy of Management Review, 39(3), 364–381.

Bjerregaard, T., & Jonasson, C. (2014). Managing unstable institutional contradictions: The work of becoming. Organization Studies, 35(10), 1507–1536.

Borzaga, C., & Defourny, J. (2001). The emergence of social enterprise. New York, NY: Routledge.

Cloutier, C., & Langley, A. (2013). The logic of institutional logics: Insights from french pragmatist sociology. Journal of Management Inquiry, 22(4), 360–380.

Currie, G., & Spyridonidis, D. (2016). Interpretation of multiple institutional logics on the ground: Actors’ position, their agency and situational constraints in professionalized contexts. Organization Studies, 37(1), 77–97.

David, R. J., Sine, W. D., & Haveman, H. A. (2012). Seizing opportunity in emerging fields: How institutional entrepreneurs legitimated the professional form of management consulting. Organization Science, 24(2), 356–377.

Davis, G. F. (2009). Managed by the markets: How finance re-shaped America. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Defourny, J., & Nyssens, M. (2010). Conceptions of social enterprise and social entrepreneurship in Europe and the United States: Convergences and divergences. Journal of Social Entrepreneurship, 1(1), 32–53.

Delbridge, R., & Edwards, T. (2013). Inhabiting institutions: Critical realist refinements to understanding institutional complexity and change. Organization Studies, 34(7), 927–947.

Denzin, N. K., & Lincoln, Y. S. (2000). Qualitative research. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

Dhawan, H. (2014). Govt may lift ban on private and community radio news. The Times of India, January 5. Retrieved from http://timesofindia.indiatimes.com/india/Govt-may-lift-ban-on-private-and-community-radio-news/articleshow/28415712.cms

DiMaggio, P. J., & Powell, W. W. (1991). The new institutionalism in organizational analysis. Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press.

Dorado, S. (2005). Institutional entrepreneurship, partaking, and convening. Organization Studies, 26(3), 385–414.

Eisenhardt, K. M. (1989). Building theories from case study research. Academy of Management Review, 14(4), 532–550.

Eisenhardt, K. M., & Graebner, M. E. (2007). Theory building from cases: Opportunities and challenges. Academy of Management Journal, 50(1), 25–32.

Eswaran, M., Ramaswami, B., & Wadhwa, W. (2013). Status, caste, and the time allocation of women in rural India. Economic Development and Cultural Change, 61(2), 311–333.

Fendt, J., & Sachs, W. (2007). Grounded theory method in management research: Users’ perspectives. Organizational Research Methods, 11(3), 430–455.

Garud, R., Jain, S., & Kumaraswamy, A. (2002). Institutional entrepreneurship in the sponsorship of common technological standards: The case of sun microsystems and java. Academy of Management Journal, 45(1), 196–214.

Glaser, B. G., & Strauss, A. L. (1967). The discovery of grounded theory: Strategies for qualitative research. Chicago, IL: Aldine.

Glynn, M. A., & Lounsbury, M. (2005). From the critics corner: Logic blending, discursive change and authenticity in a cultural production system. Journal of Management Studies, 42(5), 1031–1055.

Greenwood, R., Diaz, A. M., Li, S. X., & Lorente, J. C. (2010). The multiplicity of institutional logics and the heterogeneity of organizational responses. Organization Science, 21(2), 521–539.

Greenwood, R., Raynard, M., Kodeih, F., Micellota, E., & Lounsbury, M. (2011). Institutional complexity and organizational responses. The Academy of Management Annals, 5(1), 317–371.

Greenwood, R., & Suddaby, R. (2006). Institutional entrepreneurship in mature fields: The big five accounting firms. Academy of Management Journal, 49(1), 27–48.

Greve, H., Pozner, J.-E., & Rao, H. (2006). Vox Populi: Resource partitioning, organizational proliferation, and the cultural impact of the insurgent microradio movement. American Journal of Sociology, 112(3), 802–837.

Hargrave, T. J., & Van De Ven, A. H. (2006). A collective action model of institutional innovation. Academy of Management Review, 31(4), 864–888.

Hirsch, P., & Lounsbury, M. (2015). Toward a more critical and ‘Powerful’ institutionalism. Journal of Management Inquiry, 24(1), 96–99.

Hoffman, A. J. (1999). Institutional evolution and change: Environmentalism and the U.S. Chemical industry. Academy of Management Journal, 42(4), 351–371.

Jay, J. (2012). Navigating paradox as a mechanism of change and innovation in hybrid organizations. Academy of Management Journal, 56(1), 137–159.

Jenkins, G. W. (2015). The Wall Street takeover of nonprofit boards. Stanford Social Innovation Review, 13, 46–52.

Kennedy, M. T., & Fiss, P. C. (2013). An ontological turn in categories research: From standards of legitimacy to evidence of actuality. Journal of Management Studies, 50(6), 1138–1154.

Kent, D., & Dacin, M. T. (2013). Bankers at the gate: Microfinance and the high cost of borrowed logics. Journal of Business Venturing, 28(6), 759–773.

Kumar, K. (2003). Mixed signals: Radio broadcasting policy in India. Economic and Political Weekly, 38(22), 2173–2182.

Labianca, G., Gray, B., & Brass, D. J. (2000). A grounded model of organizational schema change during empowerment. Organization Science, 11(2), 235–257.

Lawrence, T. B., Hardy, C., & Phillips, N. (2002). Institutional effects of interorganizational collaboration: The emergence of proto-institutions. Academy of Management Journal, 45(1), 281–290.

LeCompte, M. D. (2000). Analyzing qualitative data. Theory into Practice, 39(3), 146–154.

Lefsrud, L. M., & Meyer, R. E. (2012). Science or science fiction? Professionals’ discursive construction of climate change. Organization Studies, 33(11), 1477–1506.

Lounsbury, M. (2007). A tale of two cities: Competing logics and practice variation in the professionalizing of mutual funds. Academy of Management Journal, 50(2), 289–307.

Lounsbury, M., Ventresca, M., & Hirsch, P. M. (2003). Social movements, field frames and industry emergence: A cultural-political perspective on US recycling. Socio-Economic Review, 1, 71–104.

Marquis, C., & Lounsbury, M. (2007). Vive la resistance: Competing logics and the consolidation of U.S. community banking. Academy of Management Journal, 50(4), 799–820.

Maxwell, J. A. (2013). Qualitative research design: An interactive approach. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

McCracken, G. (1988). The long interview. London: Sage.

Mintzberg, H. (1979). An emerging strategy of direct research. Administrative Science Quarterly, 24(4), 582–589.

Munir, K. A. (2015). A loss of power in institutional theory. Journal of Management Inquiry, 24(1), 90–92.

Navis, C., & Glynn, M. A. (2010). How new market categories emerge. Administrative Science Quarterly, 55(3), 439–471.

Ocasio, W., Mauskapf, M., & Steele, C. (2016). History, society, and institutions: The role of collective memory in the emergence and evolution of societal logics. Academy of Management Review, 41(4), 676–699.

Pache, A. C., & Santos, F. (2010). When worlds collide: The internal dynamics of organizational responses to conflicting institutional demands. Academy of Management Review, 35(3), 455–476.

Pache, A. C., & Santos, F. (2013). Embedded in hybrid contexts: How individuals in organizations respond to competing institutional logics. In M. Lounsbury & E. Boxenbaum (Eds.), Institutional Logics in Action, Part B (Vol. 39, pp. 3–35). Research in the Sociology of Organizations. Bingley, UK: Emerald Group Publishing Limited.

Padgett, J. F., & Powell, W. W. (2012). The problem of emergence. In J. F. Padgett & W. W. Powell (Eds.), The emergence of organizations and markets (pp. 1–32). Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

Page, S. E. (2015). What sociologists should know about complexity. Annual Review of Sociology, 41(1), 21–41.

Patil, D. A. (2014). Exploring the subaltern voices: A study of Community Radio Reporters (CRR’s) in rural India. The Qualitative Report, 19(33), 1–26.

Pavarala, V., & Malik, K. K. (2007). Other voices: The struggle for community radio in India. New Delhi: Sage.

Powell, W. W., Packalen, K., & Whittington, K. (2012). Organizational and institutional genesis. In F. J. Padgett & W. W. Powell (Eds.), The emergence of organizations and markets (pp. 434–465). Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

Powell, W. W., & Sandholtz, K. W. (2012). Amphibious entrepreneurs and the emergence of organizational forms. Strategic Entrepreneurship Journal, 6(2), 94–115.

Pratt, M. (2009). From the editors: For the lack of a boilerplate: Tips on writing up (and reviewing) qualitative research. Academy of Management Journal, 52(5), 856–862.

Purdy, J. M., & Gray, B. (2009). Conflicting logics, mechanisms of diffusion, and multilevel dynamics in emerging institutional fields. Academy of Management Journal, 52(2), 355–380.

Qureshi, I., Kistruck, G. M., & Bhatt, B. (2016). The enabling and constraining effects of social ties in the process of institutional entrepreneurship. Organization Studies, 37(3), 425–447.

Raman, A. (2015). Community radio stations now face the heat. The Hindu, May 1. Retrieved from http://www.thehindu.com/news/national/community-radio-stations-now-face-the-heat/article7160000.ece

Reed, M. I. (2012). Masters of the universe: Power and elites in organization studies. Organization Studies, 33, 203–221.

Reinecke, J., Manning, S., & von Hagen, O. (2012). The emergence of a standards market: Multiplicity of sustainability standards in the global coffee industry. Organization Studies, 33(5–6), 791–814.

Riaz, S., Buchanan, S., & Ruebottom, T. (2016). Rhetoric of epistemic authority: Defending field positions during the financial crisis. Human Relations, 69(7), 1533–1561.

Ruef, M. (2000). The emergence of organizational forms: A community ecology approach. American Journal of Sociology, 106(3), 658–714.

Sarma, A. (2013). Community radio in India issues and challenges. Asian Journal of Research in Business Economics and Management, 3(1), 323–333.

Schneiberg, M., King, M., & Smith, T. (2008). Social movements and organizational form: Cooperative alternatives to corporations in the American insurance, dairy, and grain industries. American Sociological Review, 73(4), 635–667.

Schneiberg, M., & Lounsbury, M. (1998). Social movements and institutional analysis. Analysis, 43(780), 648–670.

Scott, W. R. (2013). Institutions and organizations: Ideas, interests, and identities. London: Sage.

Seo, M.-G., & Creed, W. E. D. (2002). Institutional contradictions, praxis and institutional change: A dialectical perspective. Academy of Management Review, 27(2), 222–247.

Strauss, A., & Corbin, J. (1998). Basics of qualitative research: Procedures and techniques for developing grounded theory. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

Suddaby, R. (2006). What grounded theory is not. Academy of Management Journal, 49(4), 633–642.

Suddaby, R. (2015). Can institutional theory be critical? Journal of Management Inquiry, 24(1), 93–95.

Thornton, P. H. (2002). The rise of the corporation in a craft industry: Conflict and conformity in institutional logics. Academy of Management Journal, 45(1), 81–101.

Thornton, P. H., & Ocasio, W. (2008). Institutional logics. In R. Greenwood, C. Oliver, S. K. Andersen, & R. Suddaby (Eds.), Handbook of organizational institutionalism (pp. 99–129). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

Thornton, P. H., Ocasio, W., & Lounsbury, M. (2012). The institutional logics perspective: A new approach to culture, structure, and process. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

UNESCO. (2003). Legislation on community radio broadcasting: Comparative study of the legislation of 13 countries.

Vaast, E., Davidson, E. J., & Mattson, T. (2013). Talking about technology: The emergence of a new actor category through new media. MIS Quarterly, 37(4), 1069–1092.

Van der Zwan, N. (2014). Making sense of financialization. Socio-Economic Review, 12(1), 99–129.

van Gestel, N., & Hillebrand, B. (2011). Explaining stability and change: The rise and fall of logics in pluralistic fields. Organization Studies, 32(2), 231–252.

Zald, M. N., & Lounsbury, M. (2010). The wizards of OZ: Towards an institutional approach to elites, expertise and command posts. Organization Studies, 31, 963–996.

APPENDIX A

Table A1. Archival Sources.

Government of India Archives. Relevant documents from |

Ministry of Information and Broadcasting Ministry of Information and Broadcasting

|

Ministry of Communication and Information Technology Ministry of Communication and Information Technology

|

Ministry of Defense Ministry of Defense

|

Home Ministry Home Ministry

|

Consultation papers and recommendations |

Policy Guidelines for setting up Community Radio Stations in India, 2002 Policy Guidelines for setting up Community Radio Stations in India, 2002

|

Telecom Regulatory Authority of India, Consultation paper, 2004 Telecom Regulatory Authority of India, Consultation paper, 2004

|

Telecom Regulatory Authority of India, recommendations, 2004 Telecom Regulatory Authority of India, recommendations, 2004

|

Policy guidelines for setting up community radio stations, 2006 Policy guidelines for setting up community radio stations, 2006

|

Community radio-grant of permission agreement, 2006 Community radio-grant of permission agreement, 2006

|

Compendium 2011 – Community radio stations in India Compendium 2011 – Community radio stations in India

|

List of operational community radios, 2012 List of operational community radios, 2012

|

Compendium 2013 – Community radio: celebrating a decade of people’s voices Compendium 2013 – Community radio: celebrating a decade of people’s voices

|

Community radio – grant of permission agreement, 2014 Community radio – grant of permission agreement, 2014

|

Telecom Regulatory Authority of India, Consultation paper – Issues related to Community Radio Stations, 2014 Telecom Regulatory Authority of India, Consultation paper – Issues related to Community Radio Stations, 2014

|

Compendium 2014 – Community radio for social change Compendium 2014 – Community radio for social change

|

Telecom Regulatory Authority of India, recommendations, 2014 Telecom Regulatory Authority of India, recommendations, 2014

|

DAVP Empanelment Guide for Community Radio Stations, 2014 DAVP Empanelment Guide for Community Radio Stations, 2014

|

Process and Document Checklist for Community Radio License Procedure, 2014 Process and Document Checklist for Community Radio License Procedure, 2014

|

List of operational community radios, 2015 List of operational community radios, 2015

|

International and multilateral agencies |

UNESCO National Consultation Report − 2007 UNESCO National Consultation Report − 2007

|

UNESCO − 2011: Ground Realities – Community radio in India UNESCO − 2011: Ground Realities – Community radio in India

|

UNESCO, CEMCA, Ideosync-Community radio and sustainability UNESCO, CEMCA, Ideosync-Community radio and sustainability

|

UNESCO Chair on Community Media Quarterly Publication (2010–2015) UNESCO Chair on Community Media Quarterly Publication (2010–2015)

|

Information on the website of Ek Duniya Anek Awaaz (http://edaa.in/) Information on the website of Ek Duniya Anek Awaaz (http://edaa.in/)

|

Information on the website of OneWorld Foundation India (http://oneworld.net.in/) Information on the website of OneWorld Foundation India (http://oneworld.net.in/)

|

Information on the website of Commonwealth Educational Media Centre of Asia (CEMCA, http://cemca.org.in/) Information on the website of Commonwealth Educational Media Centre of Asia (CEMCA, http://cemca.org.in/)

|

CEMCA-Ethical practice guidelines for community ratio stations, 2013 CEMCA-Ethical practice guidelines for community ratio stations, 2013

|

CEMCA – Development of community radio continuous improvement toolkit, 2015 CEMCA – Development of community radio continuous improvement toolkit, 2015

|

CEMCA – Innovations in community radio, 2015 CEMCA – Innovations in community radio, 2015

|

APPENDIX B

Table B1. Interviewee Codes and Description.

Interviewee Code |

Interviewee Description |

I-1 |

Board member of a nonprofit, early activist, affiliated to donor agency |

I-2 |

Communication consultant |

I-3 |

Media researcher |

I-4 |

Board member of a CR support organization, early activist, affiliated to donor agency |

I-5 |

Academic media researcher, activist |

I-6 |

Academic media researcher |

I-7 |

Board member of a CR support organization, early activist, donor agency |

I-8 |

Media professional |

I-9 |

NGO head, CR support organization member |

I-10 |

CR support organization member, NGO professional |

I-11 |

CSR run CR station manager |

I-12 |

NGO head, CR station manager |

I-13 |

CR support organization member, academic researcher, CR station manager |

I-14 |

Policy actor |

I-15 |

CR support organization member, media consultant |

I-16 |

NGO professional |

I-17 |

Student researcher |

I-18 |

CR station manager, educational institute |

I-19 |

CR station manager, CR support organization member |

I-20 |

CR station manager, NGO head |

I-21 |

Academic, CR support organization director |

I-22 |

CR station manager and founder |

I-23 |

NGO professional, CR support organization member |

I-24 |

CR station manager, NGO professional |

I-25 |

NGO professional, student |

I-26 |

NGO founder, CR support organization member |

I-27 |

CR station manager, NGO professional |

I-28 |

Student researcher |

I-29 |

CR station manager and founder |

I-30 |

CR station manager, semi-government organization |

I-31 |

CR station manager, NGO professional |

I-32 |

Government consultant, NGO board member |

Ministry of Information and Broadcasting

Ministry of Information and Broadcasting