I remember receiving some early coaching advice from an MIT professor. He told his seminar class a story about taking his daughter crabbing in the Boston Bay. She was very worried about there being no lid on the pail. The professor told his daughter that no lid was needed—anytime one of the crabs started working its way to the top, another would reach up and pull it down. The moral of the story was that chronically negative people (crabs) would bring the whole team down and never allow any one of them or the team to reach new heights.

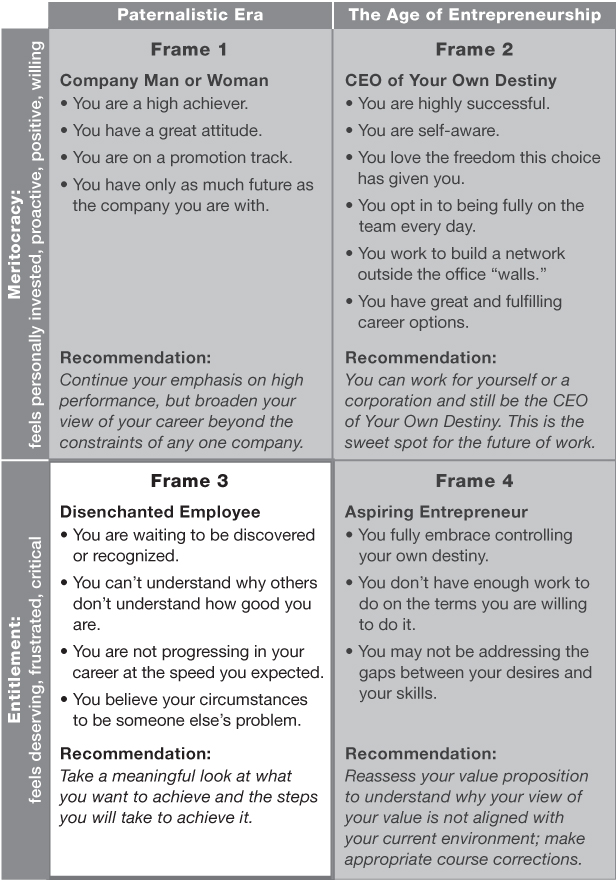

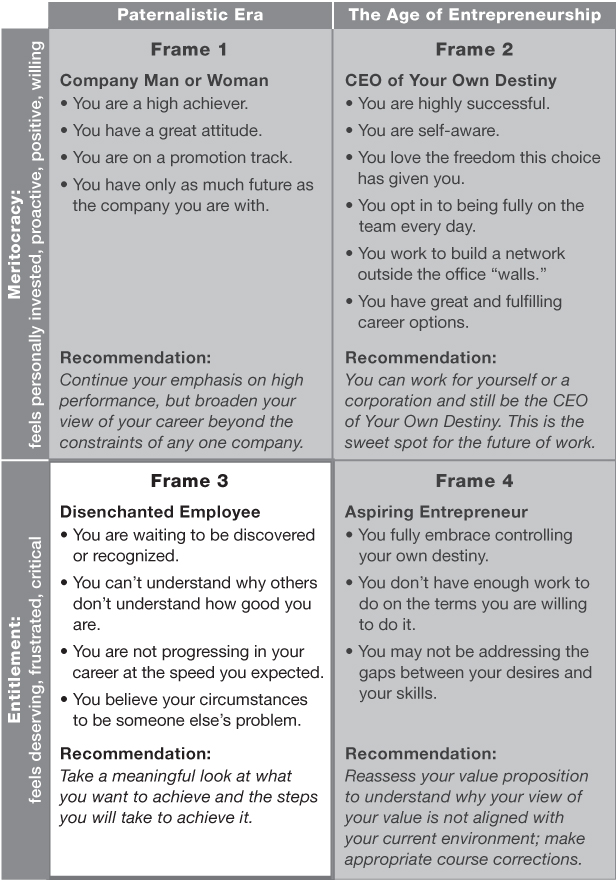

I often ask managers how many of their team they would rehire if they were starting over. In my entire career, there is only one time that a manager told me that he would rehire everyone on his team. We actually should be striving to have a team full of high-potential, high-performing individuals. If you have a couple of Frame 3 employees on your team, I assure you that your entire team will suffer.

If you live in Frame 3, please look hard at yourself in the mirror and realize that it's time to take the steps needed to get to another frame. I find that people who live chronically in Frame 3 tend to have a detrimental, negative outlook—and with it come significant ramifications: other people will be far less interested in spending additional time with them, offering them additional opportunities, or cheering them on. Any other frame is better than Frame 3—and a step closer to Frame 2, where we should all want to be.

The Framework: Where Do You See Yourself?

On-the-job stress is cited as the number-one reason for employee dissatisfaction in the American workforce: 40 percent of Americans say their job is “very or extremely stressful”; one in four employees view it as the number-one stressor in their lives; 42 percent say the stress interferes with their family or personal lives.1 The prime causes of all this stress, according to a Harris Interactive poll, are low pay, commuting, unreasonable workload, and fear of being fired or laid off.2

The statistics are alarming—this type of stress and unhappiness leads to Frame 3—the worst place for employees to be. I really worry about people who spend the majority of their time in this space. It's unhealthy for companies and for individuals.

Studies have found that unhappiness at work has a significant negative impact on one's health. Unlike one hundred years ago, when work was physically dangerous, in this century, work has become more psychologically dangerous. Sound crazy? Not really: research shows that chronic levels of work stress increase the risk of everything from the common cold to Alzheimer's, heart disease, and depression. In fact, numerous studies have found that “psychosocial” factors—like work-related stress—represent the single most important variable in determining how long somebody lives.3

Here's the amazing thing about what causes the most stress in our modern world. What stresses people out the most is not the number of hours in the workday or the bad nature of their boss, but the feeling that they have little say over their day. People are most unhappy when they can't choose their own projects or make their own decisions about what to focus on first.4 Therefore, folks in Frame 3—those who feel least in control and most like a victim of their fate—are the most at risk.

It's an unfortunate state of affairs that people are so unhappy at work, especially when Americans spend so much of their lifetimes in the office. This is especially disheartening when we consider how easy it is to change. People who are living in Frame 2, those who feel that they are the CEOs of their own destinies and calling their career shots, are happier. A Gallup poll found that self-employed people in the United States are the happiest workers and work the hardest5 because they have a “higher measure of self-determination and freedom.”6 Furthermore, this free choice, or being “the boss of you,” was a bigger predictor of happiness than making more money or achieving a greater sense of democracy and social tolerance.7 Need further evidence? The research of Italian economist Paolo Verme found that freedom and control are by far the most significant predictors of life satisfaction anywhere in the world.8 They come before money, demonstrating that pursuing what you want is a lot more rewarding than pursuing a paycheck.

That's why we see that home-based workers are sick or absent less often than people who work in an office. Not only does work make some people sick, but there is a whole population of people who fake an illness to shirk work. Consider that 78 percent of employees who call in sick aren't really sick.9 These individuals are stuck in Frame 3, unhappy with their jobs and cranky about it, but not doing anything meaningful to change it. And Frame 3 is certainly costly to companies: these unscheduled absences cost employers $1,800 per employee per year—totaling $300 billion per year for U.S. companies.10 Employers could stop this waste and use the savings toward other functions that produce a return, such as investing in innovation.

Living in Frame 3 isn't sustainable. Luckily, there's a clear path out: understanding how you got here; taking the time to think about what you really want; creating a plan, as discussed in Chapter Five; and working with a few trusted mentors and advisers, as we'll discuss in the next section.

Whether you are a winning gymnast in the Olympics, a tennis player in the U.S. Open, or a pitcher in the major leagues, you got to the pinnacle of your career with a mix of natural ability, hard work, and coaching. We understand that in sports there is a great coach behind every great player, and we celebrate these folks, but in work we somehow forget their importance. We leave behind what we learned in school athletics and approach our professional lives without giving much thought to coaching (mentoring) or where to look to continue to build our skills and abilities and be the best we can be.

That's a mistake. Everyone does better with someone watching. All of us can benefit from a mentor who can observe, offer insight, and guide us. Atul Gawande, a successful surgeon, asked a former teacher to serve as his mentor, even though Gawande was well established in his career. It was an untraditional move, and one that unnerved some of his patients, but Gawande felt that the relationship made him better in his craft—helped him understand things he might have missed because he was set in his way of doing things. He compared the experience of this kind of coaching in medicine to the way professional musicians have coaches, whom they refer to as “outside ears.” He wanted to bring that perspective into his profession—and into others, to anyone who “just want[s] to do what they do as well as they can.”11

I owe much of my personal and professional success to mentors. As it did for most people, this guidance came in its earliest form from my athletics coaches. Charlie Rowe in Little League and Abner Bigbie in high school football helped me find my talents and hone my skills. Cognizant that I had lost my dad, they stepped in and served as role models and inspiring coaches both on and off the field. Later, I found mentors at work. At IBM, one of my mentors, John Martone (a guy with a wood desk, signifying that he'd made it), suggested I start dressing more professionally, and then helped me do so by giving me some of his old suits. He told me to walk with purpose (as though I knew where I was going), and he helped me crisp up my writing.

Even though I was, for much of my career, a company guy, I consistently looked for inspiration outside the walls of my organization. Perhaps I did that because I understood the influence of my coaches in my youth, but most of all because I needed to. When I left IBM, I worked for much smaller companies that didn't have nearly the same focus on people that IBM did. There were no formal programs offered, so I had to develop mentors and coaches on my own. Furthermore, as my career progressed, I found that the right kind of mentors and role models I needed to help me grow did not exist within my company.

In 1992, I was an IT network director (working on how computers and people interact with each other) when I decided I wanted to become a chief information officer (CIO). It was a very cool emerging new job that would put me in charge of the internal systems and infrastructure processes that companies use to operate all of their business and interact with customers and suppliers. It was a challenging job no one wanted; it required completing multimillion-dollar projects on time and converting tech talk to business speak. There wasn't a handbook on how to do this, particularly as the role evolved in the late 1980s and early 1990s. (It was during this time that tech professionals were first elevated to the executive suite.) I wanted to be a part of this growing field and was especially excited about the next wave that incorporated information technology into business strategy.

Not knowing whom to tap for advice at my own company, I took matters into my own hands. I subscribed to CIO magazines and created a database of people I admired. I read studies and discovered the thought leaders in the burgeoning space. I went to industry events and listened to luminaries in my field. I got to know who they were, what they were about, and, most important, what success looked like to them.

I created a “CIO List” from the database I developed. I tracked who they were, how I knew them, and their remarkable accomplishments. I urge you to do this, but please be mindful of people's time and respectful of their boundaries. Remember that creating relationships with your role models can be about giving more than getting. I didn't want to meet these individuals for their fame; I wanted to learn how they achieved and sustained their success so that I could become better at my trade and ultimately make a better contribution to this space. Today, making these kinds of connections is easier than ever, as so much of this valuable information is available on the Web. Yahoo! and Google made it possible to search anything. Nearly everyone has a LinkedIn profile that highlights his or her career path. Industry leaders write articles and position papers and blogs. Read them.

With office buildings and hierarchies on the wane, workers have to go out and build connections themselves. I urge you to see the importance of mentors, but untangle them from the workplace. Like everything else in the changing world of work, these pivotal relationships will not develop in the office. They will come from your network. This is good news and a serious upgrade: the network has more power and influence than does one assigned mentor. With a network culled from a variety of areas, you gain access to the best and brightest minds that have the most experience specifically relevant to you and your dreams.

Once upon a time, mentors and coaches were assigned to employees. Workers were given a very clear road map to follow, and the definitions of success were clear (even if some of them were crazy). This kind of defined structure scarcely exists anymore, for a few reasons. Employee tenure has consistently become shorter, which makes getting advice or help from one's company less practical than ever. In addition, middle management has been slashed, and there are fewer folks with enough bandwidth to help. Competition is fierce, and in some cases, people worry about training their own replacement, someone the company may view as newer and less expensive. With people concerned about making themselves redundant, there's no longer an opportunity to receive years of coaching from one boss. This shift away from internal coaching is only going to be exacerbated by further shrinkages in employee tenure, and location will matter less as more people work remotely and become more entrepreneurial (either starting their own companies or becoming freelancers). Also, mentoring seldom exists at underresourced, fast-paced start-ups.

Where does this leave us? Jim Billington presciently wrote in 1997 that “the traditional mentor-protégé relationship has gone the way of the mainframe computer—while it hasn't completely disappeared, it isn't nearly as common as it used to be. Reengineering, flatter organizations, and a lack of gray-haired senior vice presidents have all contributed to the decline.”12 Now, more than fifteen years later, in the age of iPad and tablets, the mainframe has disappeared, and the mentor-protégé relationship has gone with it.

We have to acknowledge that in the Age of Entrepreneurship, the onus of personal and professional development is on the individual, not on the company. I hope that instead of fearing this new responsibility, you'll see the many benefits it brings. One of the most crucial improvements is that it eradicates the inherent conflict of interest that comes from getting advice from your employer. There are very few mentors within your company who are actively committed to having you consider extending your career outside of their company (especially if you are a star performer). You can understand why: there are never enough of the best resources on hand, and it would take a very selfless leader to be willing to lose a great talent.

Just think of how upset companies get when others (particularly competitors) recruit their best people. They call it poaching—clearly looking at it through a lens that focuses on the loss to the company, not the possible personal gain and benefit to the employee. (This is not an approach that benefits individuals. Professor Matt Marx at MIT's Sloan School of Management studies how some workplace practices, such as noncompete clauses, have a negative impact on employees. His research finds that when noncompetes are in place, employees will often stay at their current job—even if unhappy—simply to avoid any legal risk. If they leave, they often switch industries, to the detriment of their own economics and long-term potential as well as their industries.13) In short, policies that are designed to “keep” people ultimately hurt the employees' personal growth, the company's culture, and the industry these stars might defect from.

When I was at IBM, I had some good managers and advisers, and they encouraged me to take on special assignments and roles that provided visibility to senior corporate execs. I remember in my early career having built a very good reputation in computer security and being groomed to eventually move up the ranks into “corporate” in that field. The computer security department was moved into the IT department, and I acquired a new manager. Within a few months, he offered me a unique opportunity to move into financial systems in Boca Raton. I took the job excitedly, but I remember getting a very angry call from the head of security telling me that he was displeased that they were “losing” me.

The intrinsic problem with receiving coaching from your boss is that what might be a win for you is a loss for him or her. Companies don't want to relay how valuable you might be to someone else. And for someone who doesn't want to spend his or her entire career in one place, that makes mentoring as we know it a system that doesn't work very well.

Employees are aware that the system doesn't work. In a 2007 interactive poll by the Human Capital Institute about the business value of coaching or mentoring programs, participants were asked, “How effective is your organization in evaluating the business impact of coaching?” Sixty-six percent of respondents answered “not effective,” 32 percent said “moderately effective,” and 0 percent replied “very effective.”14 It's like the mainframe: it's outdated technology.

In the last decade, the social networking trend was born. Most if not all of us are familiar with Facebook, Twitter, and LinkedIn, but I'll admit I was initially turned off by these sites. As a busy executive, I spent much of my time focusing on big company issues and had little opportunity to network with random or long-lost acquaintances. The thought of putting my name out on LinkedIn so that folks could “network” with me on their terms was not appealing. I was amazed that people would put so much of their lives up on Facebook to share with mere acquaintances. I got most of my information from the web and newspapers.

Over time, though, I warmed up to the power of these networks as I realized that you can learn a lot quickly, and I developed protocols to protect my privacy. Soon, I realized I had more bandwidth than I'd thought and that I could handle the additional streams. Today, I get almost all of my latest-breaking information off of RSS feeds to my smartphone through Yahoo! and Twitter. I have more than one thousand contacts on LinkedIn. We are building special private networks within LinkedIn for my investment network (WIN) to collaborate on deals. I use Facebook. At my thirtieth high school reunion, no one knew how to find me; now, in time for my fortieth reunion, I am “friends” with more than fifty former classmates and can quickly get updated on their lives. I am able to keep up with many colleagues, and it adds a richness to know about their families and hobbies and to see them as people instead of just as work peers.

But enough about my personal life and productivity. Who would have envisioned the power of these networks to topple regimes around the world—Tunisia, Egypt, Libya, and who knows what other countries coming next? We're still in the early days of seeing the power of communities applied to companies, but it's evident that having these external networks vastly increases our work opportunities and options. This is the power of the new network.

Maintaining your own personal networks is much easier than ever before—even more so, it's becoming mandatory, as the people who do this well gain a significant advantage. Today, it's possible to access almost anyone—and that introduces incredible opportunities to build networks that can enable your careers. This external board of advisers can offer insight, direction, and introductions. These mentors can make a tremendous impact on your career and your life.

Much has been researched and written about the value of mentors at work. The relationship produces results: a large body of research demonstrates that when looking at career mentoring in terms of objective career success, better mentoring resulted in greater compensation, greater salary growth, and more promotions.15 In addition, people benefit personally. Other studies have found that people were more clear about their “professional identity,” meaning their unique talents and contributions at work as well as their personal values, strengths, and weaknesses.16 Perhaps this is one of the reasons why the existence of a formal mentoring program is now a criterion against which the “Best Companies to Work For” are judged.17

So why do so few of us actually invest time in building relationships with mentors or coaches? When looking for advice, people most often go to the most convenient sources, but not the right ones. They haven't developed their own networks, so they ask for advice from whoever is right in front of them. Perhaps it's their boss, or colleagues at their company. Often it's their spouses, parents, or friends. Is this really the best way? Friends are great supporters, but do they really know how you can best leverage your skill set to advance in your changing industry—an industry that is different from theirs? Your mother might know you best and be your biggest fan, but does she really know how much you are worth in the marketplace?

And mentors at work? Besides the conflict of interest we already discussed, the way mentoring is approached inside companies is somewhat misguided. Too often, mentoring takes place at specified times, such as during a performance review. There are several problems with this. First of all, it happens infrequently, usually once or twice a year, which is not enough. Second, it's tied to compensation, which often makes the conversation very tense. That's not the right time to absorb advice. People do not feel receptive and open at a time when economics are at stake. Finally, this hierarchical boss-employee structure is more like a parent–child relationship, which is not what the mentoring relationship should replicate. It also can be ruled by politics rather than reality—that is, managers are instructed as to how to rank employees, and conversations are often dictated by the need for an employee to fit into a certain slot rather than by the truth about his or her performance.

It's best to discuss development and future goals in a different zone, when people are in a more receptive place and thinking about the future as opposed to being judged for the past. Increasingly, next-generation companies are looking to new systems to change annual reviews and performance conversations to offer real-time feedback. Companies including Facebook, LivingSocial, and Spotify use social technologies such as Work.com to enable continuous advice, feedback, and recognition from people across all levels of the organization. This is a much more modern way to manage; it eliminates hierarchies and empowers and enables people to do their best work. Services like Work.com work within an organization, but as organizational walls break down further, we'll need to add external solutions to help identify mentors and connect with them.

Rebecca Graf, whose journey from Frame 1 to Frame 2 we followed in Chapter Five, and who had her share of moments in Frame 3 in the process, credits her very supportive friends who “got her through everything.” Interestingly, these weren't Rebecca's former classmates or colleagues. In fact, some of them she never even met in person. As Rebecca began her career as a freelancer, she kept in touch with others in a similar position—a proofreader, an editor she met on an assignment, a classmate from her new online school—and built a network of people who had been through some comparable experiences and understood her goals. She kept in touch with them on Facebook and LinkedIn and via email and Skype, and says she would reach out to them when she was struggling with something—whether facing a plot snafu in her book or just needing some encouragement that it would work. “They are the reason I keep going,” she says. These people also became trusted colleagues and cofounders in her new publishing endeavor.

As Rebecca has found, there's incredible merit to having a network of trusted advisers. In the process of writing this book, I looked for formal mentoring services that could help individuals build their own external networks to which they could go for insight, advice, and encouragement. There wasn't one service that was implemented broadly, so with a team of great entrepreneurs, I created a company, which connects people with experts who can give them appropriate advice. Think of it as eHarmony meets LinkedIn. Developing personal networks takes time and effort, but with social technologies it's easier than ever to find great mentors anywhere.

Too often we are guilty of making a terrible mistake: we keep our dreams and aspirations near and dear and are reluctant to share them with anyone. But when dreams are kept private, it's harder for them to take off. However, when we share them, amazing things can happen. Just ask Marc Benioff. When he started salesforce.com, he was, unlike many entrepreneurs, open to sharing his idea with trusted advisers and mentors and was thus able to tap into helpful expertise and a critical network. One of his mentors, a successful entrepreneur named Bobby Yazdani, the founder of Saba Software, introduced him to three talented developers who became Marc's cofounders and helped him build an incredible service and company. In fact, Marc has described meeting Parker Harris, one of the developers, as “the luckiest thing in my life.” It wasn't luck; it was the result of Marc's articulating his vision and sharing it with a mentor who had experience, understanding, and a desire to help.

Marc Benioff's passion, energy, and enthusiasm for creating a whole new space called cloud computing inspire me. He had a vision for changing the software industry, and he didn't stop with cloud computing; he extended it to leverage social technologies. Most of all, he does everything with a big heart. In a similar vein, Steve Jobs's unbelievable dedication to creating great products that are focused on the customer experience has taught me many lessons. I admire Meg Whitman's ability to see what needs to be done, and to articulate it and inspire a team. She has a willingness to tackle hard and significant problems—which is why she ran for governor of California and why she is now heading up one of the world's biggest technology companies, Hewlett-Packard, even though she has already accomplished so much. These people have served as important mentors to me, and they have given me direction and purpose that has greatly affected my career and life.

The exercise in Appendix A on becoming the CEO of Your Own Destiny can help you determine and then articulate what you want to achieve at work and at home. Even though you might still be a long way from reaching your goals, sharing them with a trusted adviser is an important step to making them happen. Like my friend Marc Benioff, I believe that it's key.

Of course, the choice of the people with whom you share your goals is also an important consideration. Peter Gollwitzer, professor of psychology at New York University, who has called attention to some of the dangers of sharing goals too broadly, says that should you wish to make your goals public, you should tell only one or two people who “hold power over you” (metaphorically speaking), so that they will help you adhere to your intentions.18 Jim Billington advised a network of three: “One mentor in your company, another in your field, and a third in your career together can form the narrow, but broadening, network that you need.”19 We know that the definition of “company” may be different now, but this guidance still holds. There's a big difference between telling a few carefully selected and cultivated mentors and a few hundred friends, colleagues, relatives, and Facebook connections.

Always aim high, but be very specific about what you want to achieve and how you will achieve it, and share these plans and aspirations with a few key advisers and mentors. Doing so makes you more committed and gets others invested in seeing you reach your dreams.

I get inspired by doing new and innovative things, but I know that not everyone is as enthusiastic as I am about this. The tougher the challenges, the more intractable the resistance to change can be. And when it comes to revolutionizing work both on a micro and a macro level, there are many intimidating roadblocks.

Our technology and our digital lives have been advancing at a breakneck pace, and we have seen some of the intricate challenges that our social, business, and policy leaders are facing to keep up with this changing world. Our human hardwiring makes us fear behavioral change, and the way our businesses are structured makes it hard for management both to grant new freedoms to workers and to institute dramatic changes as a company. As technology and policy move forward, our first reactions are often based on fear. We become more protective of the old ways of doing things and often resist innovation and change.

Although we are seeing an increase in telecommuting and flex hours, corporations for the most part still adhere to yesterday's management principles, which are poorly suited for today's world. When it comes to adopting the less traditional and more innovative programs that will enable us to fix work, the most commonly cited obstacle is lack of management buy-in. Managers fear that employees, left unmonitored, will not work as hard as they otherwise would. That's baloney, though. Study after study demonstrates that people who work from home are more productive than their office counterparts. Why? In part it is because home-based workers have fewer interruptions, as they aren't distracted by chitchat, coffee breaks, birthday parties, fantasy football pools, and all the black holes that suck time out of every day in the office. Amazingly, office employees admit to wasting two hours a day outside of lunch and scheduled breaks. It adds up: businesses lose $600 billion a year in workplace distractions.20

We have to address the serious problems with the world of work and stop living in fear of failure and fear of change. We have to take a How Can I? approach. Jeremy Lin, formerly of the New York Knicks and now with the Houston Rockets, moved from an obscure backup to a team star, and even though his coaches couldn't believe how far he'd come, it wasn't all that “Lin-sane.” Lin wasn't living in Frame 3, filled with bitterness and a crabby attitude when he was sitting on the bench. He was always working on bettering himself to get where he wanted to be. He started practice early every morning—hours before his former teammates rolled in. With hard work, dedication, and a new can-do attitude, we can change our lives and take charge of our destinies.

One of the most important lessons I've learned in my career is that “miracles” happen every day in the workplace. I've been lucky enough to experience several in my career. When I went to eBay in 1999, the company was battling some significant technology issues. Many people said I was crazy to join in the midst of such turmoil. Certainly during those dark days at eBay, no one believed the company would evolve into the world's largest online marketplace and transform the world of e-commerce. But the real miracle I witnessed was not eBay's rise to greatness but rather the many moments when I saw teams unleash their potential and brilliantly solve what was previously deemed impossible.

At the time, the site's architecture couldn't handle the company's sudden growth, and the site kept crashing. At its worst, there was a twenty-two-hour outage that nearly destroyed the company. Things were so bad that employees put paper over the windows to keep the reporters from seeing in. Users grew wary, and the stock tanked.

There was a traditional way that these issues were handled: stop everything and figure out exactly what was bringing down the system. No changes. No new code. No innovation until the system was stabilized. But in an online world, that old model didn't make sense. Why did a company have to choose between stabilization and innovation when it really needed both? I realized that we needed reliability and new features that could handle increased volume. We had previously seen the dangers of making the wrong choices when eBay froze product development for three months to stabilize and we fell far behind in our development plan. In those few months, Yahoo! went into Japan and built the market, which they still dominate today.

This time we turned our back on the old-fashioned way and embraced the Spirit of “And”: we committed to stabilizing the system and making it better. (We also refunded sellers who had live auctions at the time the site went down.) As we restored trust with users and our partners, we also earned a better relationship with Wall Street.

I again saw a tech team achieve greatness against the odds when we had issues with getting search to scale at the massive rates at which we were bringing in new products. It would take twenty-four hours to index description listings before they went live, angering sellers who were paying for the service. In addition, the infrastructure updates cost the company millions. Solving this technology puzzle was not eBay's core competency, so the management team looked to buy a solution rather than build it. We approached Google and Yahoo!, but ultimately, given the uniqueness of our needs and the urgency of the situation, we decided to build it ourselves. The developer team knew its mission and didn't have to be driven hard. They were self-motivated and inspired and engaged to create change. That self-direction—as opposed to command-and-control pressure from above—made all the difference. What should have been a twelve- to eighteen-month project was achieved in two months. The newly built solution allowed us to get listings up in minutes and saved us millions of dollars.

My most favorite miracle at eBay, though, was what the team accomplished in response to 9/11. Moments after the attack, I got a call from eBay's trust and safety division: someone had tried to auction rubble from the Twin Towers on our site. It was our policy not to allow sellers to profit from disasters, but we realized that something bigger could be done than just stopping the vulture postings. That afternoon, Governor Pataki called and asked if we could auction items that were given to the state of New York and then send the proceeds to charities. What about doing something more compelling, we asked? What about firing up our community of sellers to help set up an auction and raise money for victims of the disaster?

We had never done a project like this, which we soon named Auction for America. We needed to get toll-free 800 numbers and create the capability for people to answer the calls. (Previously we had relied on emails.) There were also tax considerations and government regulatory issues and approvals we needed. And on top of that, the coding itself was massively complex. In the past, this would have taken us six months, but we didn't have that kind of time. And as it turned out—as the team showed us—we didn't need it.

We worked night and day, literally, for four nights, and maybe that sounds hellacious, but it wasn't. In that time we built a fully functioning auction site. Jay Leno donated his motorcycles, and Bo Derek donated her bathing suits. By letting go of the old way of doing things and unleashing the potential of the team and the community, we raised $25 million.

Every day I am inspired by what's possible. People thought it was impossible to walk on the moon, get fingers to grow back, or talk to anyone in the world in real time through the computer. I've been fortunate enough to learn from some of the best “and” entrepreneurs. And the results are impressive: Omar Hamoui dropped out of Wharton to start AdMob and transformed an industry in eighteen months (and had two industry titans fight over his company in their quest to dominate the mobile landscape). Marc Benioff quit an executive post at Oracle to change the enterprise software industry and pioneered a phenomenon now known as cloud computing.

There's a false notion that success is a zero-sum game. That to win in our careers we have to give up family. That to work hard we have to sacrifice sleep. That to be successful we must take (or borrow or steal) from somewhere else in our lives. It's just not the case. Working harder is not a sustainable solution, and it's not how people meet their destiny. It's time to get more creative. Instead of choosing one thing we love over something else we love, we must ask, “How can I do both?” And, then, we can find solutions (perhaps by eliminating something we hate, like commuting).

There's never been a better time to change the way you think. Replace every “I can't” with “How can I?” This might sound like semantics, but I promise that this shift in thinking will bring whatever you want to accomplish much closer to reality. Things that you thought would take six months might take six weeks, or even six days.

Where do you see yourself in nine months, two years, and five years? Where do you see yourself in the future? I think that in the future, companies will compete better, individuals will have great careers, and the planet will be sustainable. I urge you to join me. It's much more rewarding to be inspired by all that you can do rather than to be afraid that you can't.

1 Steven Sauter et al., “Stress . . . at Work,” National Institute for Occupational Health and Safety Working Paper No. 99–101 (1999), http://www.cdc.gov/niosh/docs/99-101/pdfs/99-101.pdf; see also Column Five, “Desk Rage: The Tell-Tale Signs of an Overworked Employee,” infographic on Alltop, posted May 21, 2012, http://holykaw.alltop.com/desk-rage-the-tell-tale-signs-of-an-overworke?tu2=1.

2 American Institute of Stress, “Attitudes in the American Workplace VII” (June 2001), http://americaninstituteofstress.org/wp-content/uploads/2011/08/2001Attitude-in-the-Workplace-Harris.pdf.

3 Jonah Lehrer, “Your Co-Workers Might Be Killing You: Hours Don't Affect Health Much—but Unsupportive Colleagues Do,” Wall Street Journal, August 20, 2011, http://online.wsj.com/article/SB10001424053111903392904576512233116576352.html.

4 Ibid.

5 Catherine Rampell, “The Self-Employed Are the Happiest,” New York Times, September 16, 2009, http://economix.blogs.nytimes.com/2009/09/16/the-self-employed-are-the-happiest/.

6 Matthias Benz and Bruno S. Frey, “Being Independent Is a Great Thing: Subjective Evaluations of Self-Employment and Hierarchy,” Economica 75 (2008): 362; Will Wilkinson, “Happiness, Freedom, and Autonomy,” Forbes, March 23, 2011, http://www.forbes.com/sites/willwilkinson/2011/03/23/happiness-and-freedom/.

7 Wilkinson, “Happiness, Freedom, and Autonomy.”

8 Paolo Verme, “Happiness, Freedom and Control,” Università Commerciale Luigi Bocconi, Econpubblica Centre for Research on the Public Sector, Working Paper No. 141 (July 3, 2009); available at SSRN: http://ssrn.com/abstract=1499652; Wilkinson, “Happiness, Freedom, and Autonomy.”

9 CCH, “2007 Unscheduled Absence Survey” (October, 10 2007), http://www.cch.com/press/news/2007/20071010h.asp.

10 Kate Lister and Tom Harnish, “Workshifting Benefits: The Bottom Line,” Telework Research Network (prepared for Citrix Online) (May 2010), http://www.workshifting.com/downloads/downloads/Workshifting%20Benefits-The%20Bottom%20Line.pdf.

11 Atul Gwande, “Personal Best,” New Yorker, October 3, 2011, http://www.newyorker.com/reporting/2011/10/03/111003fa_fact_gawande#ixzz1kU5yz5S2.

12 Jim Billington, “Meet Your New Mentor. It's a Network,” Harvard Business Review, August 1, 1997, 3. Available at http://hbr.org/product/meet-your-new-mentor-it-s-a-network/an/U9708A-PDF-ENG.

13 Matt Marx, “The Firm Strikes Back: Non-Compete Agreements and the Mobility of Technical Professionals,” American Sociological Review. 76, no. 5 (October 2011): 695–712.

14 Ross Jones, “Measuring the Success of Coaching and Mentoring,” Human Capital Institute white paper (May 18, 2007): 3, http://www.menttium.com/servlet/servlet.FileDownload?file=00P80000007kxTsEAI.

15 For an overview of this research, please see Tammy D. Allen, Lillian T. Eby, Mark L. Poteet, Elizabeth Lentz, and Lizzette Lima, “Career Benefits Associated with Mentoring for Protégés: A Meta-Analysis,” Journal of Applied Psychology 89, no. 1 (February 2004): 127–136.

16 Monica C. Higgins and Kathy E. Kram, “Reconceptualizing Mentoring at Work: A Developmental Network Perspective,” Academy of Management Review 26, no. 2 (April 2001): 264–288.

17 Sheryl Branch, “The 100 Best Companies to Work for in America,” Fortune 139, no. 1 (1999): 118–130.

18 Jacque Wilson, “Want to Lose Weight? Shut Your Mouth,” CNN, November 14, 2011, http://www.cnn.com/2011/11/14/health/lose-weight-mouth-shut-secret/index.html. For additional research on goal setting, see Peter M. Gollwitzer, Paschal Sheeran, Verena Michalski, and Andrea E. Seifert, “When Intentions Go Public: Does Social Reality Widen the Intention-Behavior Gap?” Psychological Science 20, no. 5 (2009): 612–618.

19 Billington, “Meet Your New Mentor. It's a Network,” 4.

20 Jonathan Spira and Joshua Feintuch, The Cost of Not Paying Attention: How Interruptions Impact Knowledge Worker Productivity (Basex, September 2005): 4, http://www.basex.com/web/tbghome.nsf/23e5e39594c64ee852564ae004fa010/ea4eae828bd411be8525742f0006cde3/$file/costofnotpayingattention.basexreport.pdf; Lister and Harnish, “Workshifting Benefits.”