We are ready to act in service of his majesty as his faithful vassals and to preserve the Japanese realm with our last drop of blood.

—Governor-General Antonio van Diemen, 1642

Two famous scenes serve to represent the Dutch position in Japan as it stabilized after the collapse of Nuyts’s embassy in 1627. The first, a familiar image reproduced in dozens of accounts, has at its center the opperhoofd, prostrate on the floor of Edo Castle’s expansive audience chamber. Gifts stacked neatly to the side, he offers annual greetings from the Oranda kapitan, or “Holland captain,” to an indifferent shogun sitting in shadows at the opposite end of the hall. The second, also a staple of accounts of the Dutch in Japan, took place hundreds of miles away from the Bakufu’s center of power in a remote part of Kyushu. In 1638, a VOC ship, the Rijp, dropped anchor near Hara Castle in Shimabara domain. Inside the walls of this dilapidated but still formidable fortress, the Dutch crew found tens of thousands of rebels, many of them Christians, that were locked in conflict with the Tokugawa regime. The Rijp had not, however, arrived to help. Instead, the ship’s gunners opened fire, lobbing hundreds of shells into the rebel encampment and killing or injuring dozens of defenders.

Both of these familiar scenes appear in Kaempfer’s account of the Dutch in Japan as the product of a top-down process, humiliating measures that “this heathen court [the Bakufu] had no qualms in inflicting upon” an unwilling company.

1 While the Dutch seem to slip naturally into this role as passive victims, the assessment strips away their own agency in crafting the framework that ultimately gave birth to such moments. Once the automatic assumption of Bakufu culpability is dropped, it becomes clear that both scenes stemmed in fact from a deliberate shift in VOC policy toward Japan that emerged as a result of the failure of Nuyts’s embassy. Beginning in the early 1630s, the company crafted a new diplomatic strategy that saw its agents in Japan repackaged not as representatives of the “king of Holland” or a sovereign lord of Batavia but as loyal vassals of the Tokugawa shogun. Repeating again and again that they aspired only to be dutiful vassals who stood ready to present their service, Dutch representatives crafted a distinctive rhetoric of subordination that came to underpin their interactions with the shogun. The result was a remarkably durable, although conspicuously unequal, framework for interaction that remained in place until the nineteenth century.

In contrast to Nuyts’s spectacular failure, the company’s diplomatic record in Japan after 1627 was far more successful, with accommodation replacing conflict as the central theme. Yet this story of adaptation, in which VOC agents pivoted to secure a place in the Tokugawa order, came at a cost. The move into the new category of subsovereign vassal stripped away the diplomatic rights that Nuyts had so vociferously defended and denied the company access to one of its most reliable policy instruments. At the same time, the reconfigured presentation came with its own requirements. Rather than simply consenting to Dutch protestations about their role as loyal vassals, the Bakufu gave concrete form to these when it required the opperhoofd to participate in the same ceremonies mandated of the shogun’s other subordinates. The result was the annual court visit, or

hofreis, that paired rhetorical claims with a heavy ceremonial requirement. When the opperhoofd pressed his head to the floor of the castle’s audience chamber, he did so not as an ambassador—indeed there were no more official VOC embassies to Japan after 1627—but as a loyal vassal required like other vassals in the Tokugawa system to perform his part in a relentless theater of submission.

2Even more worryingly, the company’s new presentation morphed into an occasional requirement for actual service. To their very real discomfort, VOC agents discovered that hyperbolic declarations were not always enough and they were expected to discharge their obligations as dutiful subordinates by providing ships and men for service against the Bakufu’s enemies. The result was to give weight to something that had started off as little more than a flattering lie, a glossy trick designed to satisfy an otherwise intractable regime. As the decades wore on and words were wrapped together with ceremony and service, it became increasingly unclear who was actually tricking whom or where performance ended and reality began.

That the company was prepared to use such rhetoric in dealing with an Asian ruler is not in itself particularly noteworthy. European enterprises in Asia frequently made use of terms of like vassal or loyal servant to hide their activities behind a cloak of political legitimacy supplied by the putative overlord. This was famously the case in India, where English representatives employed the language of dutiful service to conceal what was in fact a massive expansion of their area of influence and a further hollowing out of Mughal structures. In Japan, on the other hand, the rhetoric of subordination functioned quite differently. Rather than providing room to maneuver, it hardened, creating walls that penned in the company and limited its actions.

This chapter explores the origins, development, and implications of the idea of the Dutch as the shogun’s vassals.

3 It aims to show how VOC agents crafted the initial outlines of a new settlement with the shogun as well as to consider the ways in which its central logic gradually evolved until it slipped from their hands to gain an unexpected substance. It does this by tracing the thread of an idea from its first appearance in 1630 running through the hofreis to the Shimabara uprising and beyond, attempting in the process to show how disparate events in the history of the VOC presence in Japan can be linked together to form one coherent story.

LANGUAGE AND RHETORIC

In the months after the failure of Nuyts’s embassy, the question of diplomacy was temporarily pushed to one side by a conflict that erupted between Japanese merchants and Dutch authorities on Taiwan. While company officials worked to resolve this crisis, which will be treated in

chapter 6, they struggled with a second question: how best to reconstitute diplomatic ties once the impasse had been removed. Although it was abundantly clear that the shogun would not receive ambassadors from Batavia, there was no consensus as to how to move forward. For Jan Pieterszoon Coen, who had taken over from Pieter de Carpentier as governor-general, the solution was obvious: the company must resuscitate its older model for diplomacy and should do so as soon as possible. Having disappeared, mysteriously erased from the 1627 letter to the shogun, the Stadhouder was, Coen decided, due for an unexpected return.

With this goal in mind, he wrote to the current incumbent, Frederik Hendrik, to request a letter for the Japanese ruler. Such a document would, Coen believed, “remove all disturbances,” effectively resetting the clock and allowing the company to pick up where it had left off before Nuyts’s unfortunate embassy.

4 The governor-general was not the only one to reach this conclusion. Having struggled for weeks to explain Batavia’s authority, Nuyts himself had also decided that a letter from the “king of Holland” held the key to diplomatic interaction with Japan.

5 A return to a model of negotiation built around the Stadhouder offered an obvious advantage. While Bakufu officials were adamant that they would not accept an embassy from Batavia, the door remained firmly open for a new delegation carrying appropriate letters from the “king of Holland.” But for all this, it was also a significant step backward for the company. The entire thrust of VOC diplomacy in this period was, as detailed in the previous chapter, away from a reliance on the Stadhouder toward a focus on Batavia Castle, which had become increasingly well-established as a fulcrum for diplomatic activity.

While Coen was eager to secure a letter as soon as possible, one of the problems with relying on a distant figure in Europe for diplomatic legitimation stemmed from the long delays it imposed on any interactions and before a document from Frederik Hendrik could arrive in Batavia, the governor-general died in office, leaving his successor to inherit the problem. By chance, the position fell to an old Japan hand, Jacques Specx, who had served as the first opperhoofd of the Hirado factory and was unquestionably the most experienced of the company’s employees when it came to dealing with the Tokugawa regime. An unpopular choice with the Heeren 17, who, clearly believing he was not the right man for the job, moved swiftly to end his tenure, Specx succeeded in engineering two significant policy shifts that reoriented Dutch relations with Japan before he was replaced by his employer’s preferred candidate, Hendrik Brouwer, in 1633. The first resolved the ongoing crisis over Taiwan while the second put in place a new diplomatic strategy for dealing with the Bakufu. Instead of following Coen’s plan and waiting for the letter from Frederik Hendrik, Specx decided that the company must adapt itself to new circumstances. Rather than going backward to reclaim a role as the subjects of the “king of Holland” or persisting with attempts to secure Tokugawa recognition for Batavia, he carved out a third path that pushed the Dutch into a new diplomatic category within Japan.

The first formulation of Specx’s presentation came in two letters sent from Batavia to Edo in 1630.

6 Deliberately omitting any reference to an external authority, he informed the Bakufu that “the Netherlanders shall display such faithful service to his Majesty [the shogun] in all matters just as his Majesty expects from the Japanese that are his own vassals (

haere Majt eigen vassalen).”7 Although it seems at first a throwaway line of no great significance, this statement was in fact to reshape the nature of the relationship between the company and the shogun. After 1630 the notion of the Dutch as vassals gradually seeped down until it became a standard theme that was repeated by VOC agents in Japan, Specx’s successors as governors-general, and even by Tokugawa officials. While the precise formulation could vary, the underlying logic remained essentially consistent. At different times company agents explained that that wished “to be like vassals of His Majesty [the shogun],” that they were “and shall remain faithful vassals of the Japanese realm,” and that they should be treated “as faithful vassals of His Majesty.”

8 Phrased initially in relatively bland terms, the presentation gradually became more hyperbolic, until it reached a crescendo in 1642 when one governor-general proclaimed in a letter to Edo that he and his subordinates were willing to spill “their last drop of blood in service of His Majesty and preservation of the Japanese realm.”

9The claim was also picked up by the company’s Japanese allies including the Matsura family, who made sure that it was continually referenced during the company’s interactions with the Bakufu. In one particularly important episode, Matsura Takanobu personally intervened to alter documents from Batavia to support the reconfigured presentation. In 1633 Specx’s successor, Hendrik Brouwer, had dispatched a letter to senior Bakufu officials in Edo thanking them for reopening trade.

10 Although there was nothing particularly controversial about the contents of the document, it failed to make any mention of the Dutch as vassals, and, when he received the letter, Takanobu elected to rewrite it to match Specx’s presentation. The revised document left no doubt as to the place of the Dutch in Japan, asking the shogun to “please hold the Hollanders as His Majesty’s own people (

eijgen volck te houden) and order us in his service. If you recognize us as such, we will always be grateful because we wish to serve his majesty until death.”

11Sitting at the top of what was once labeled a feudal structure, the Tokugawa shogun had of course many subordinates that might be called vassals. Who then was Specx, an official with considerable experience of Japan, referring to when he described the Dutch as the equivalent of the regime’s

eigen vassalen? Some sense of this is provided in two extant Japanese translations of VOC letters to the Bakufu. The first of these is a translation of Specx’s original 1630 document while the second comes from 1642 when governor-general Antonio van Diemen wrote to Edo.

12 In these documents, which were prepared by translators working for the company, the word

fudai (

譜代) appears as the most common designation for the suggested relationship. Referring to vassals or servants that stood in hereditary subordination to another family or group and who were defined by their record of loyal service, the term had by this period acquired a strong connection to one particular group within the Tokugawa order: the fudai daimyo.

Under the settlement crafted by Ieyasu, all daimyo swore an oath of loyalty to the shogun and were, at least in theory, loyal vassals, but the strength and reliability of their devotion varied enormously. On the outer end of the scale were the

tozama or outside lords, who had only recognized Tokugawa authority either during or after the battle of Sekigahara in 1600. This group included domains like Satsuma that had a decidedly antagonistic relationship with the regime. In contrast, the fudai lords were hereditary vassals who had been allied to the Tokugawa family in the years prior to its ascension to power.

13 Tied by sturdy bonds to the government, the group formed a crucial buttress to the state, staffing Edo’s expanding bureaucracy and providing the shogun with administrative muscle. In return, the fudai lords, many of whom possessed very limited income from land holdings, relied on the stipends provided by these offices to survive. The result was a system of mutual dependence that ensured their commitment to the ongoing survival of the government.

14While it is impossible to say for certain that the use of the term

fudai by the Dutch was deliberate, it matches too closely to be dismissed out of hand. These lords were the exemplary loyal vassals within the Tokugawa system and an obvious point of reference for a presentation that emphasized ongoing devotion to the regime. Even if we cannot be sure about this link, it is abundantly clear, however, that the comparison was not with low-ranking retainers but with a more elevated category of vassal, the daimyo, and it is no coincidence that the Dutch were subsequently drawn into the same ceremonial requirement enforced on these lords.

To support their claims, VOC officials from Specx onward worked, in much the same way as the daimyo themselves, to construct a genealogy of service capable of tying them directly to Ieyasu, the center of an expanding Tokugawa cult. As the first VOC ships had arrived in Japan in 1609, nine years after the crucial battle at Sekigahara, it was not possible to attach the company to this momentous victory, but it could claim a connection, albeit a very limited one, to the second great campaign of the Tokugawa period, the siege of the massive fortress at Osaka that had commenced in 1614. During this crucial campaign, Ieyasu’s forces eliminated Hideyoshi’s son, Toyotomi Hideyori (1593–1615), as an alternative source of legitimacy, thereby ensuring the security of the regime. In his 1630 letter Specx noted that the Dutch had dutifully “served His Majesty Ongosio-sama [Ieyasu] in the war at Osaka with as many cannon and constables [gunners] as they had in Hirado.”

15While the claim looked good on paper, the details were much murkier. Like many groups in Japan, the Dutch had a far more ambiguous relationship with Hideyoshi’s young heir than their later presentation suggested. When he first arrived in Japan as opperhoofd, Specx had attempted to play both sides of the fence by presenting gifts not only to Ieyasu but also to Osaka Castle in case Toyotomi loyalists prevailed.

16 When war broke out, VOC merchants supplied Bakufu forces with military provisions, but they did so at a price, hoping to profit off the increased demand for military items.

17 The story of the constable was even less laudable. In September 1615, some months after the siege had concluded, the Bakufu requested a master gunner “for the service of His Imperial Majesty.”

18 The one qualified candidate, Claes Gerritsen, was needed aboard his ship, and the governing council in Hirado was not prepared to commit such a useful employee to the shogun’s service. Their preferred nominee, a drink-prone master gunner called Frans Andriessen, proved a disaster and was recalled in disgrace, leaving the shogun’s request unfulfilled.

19 Although not particularly convincing at first, the genealogy of service looked much better after the Shimabara revolt in 1637 when VOC agents were able to tie themselves to two of the three great conflicts of the Tokugawa period by arguing that “we [had] served His Majesty Ongosio Samma [Ieyasu] in the war of Osaka and the currently ruling emperor [shogun], may he long reign, against the rebels and papists of Amakusa and Arima [Shimabara].”

20After 1630, notions of the Dutch as vassals were also mobilized to provide a structure for communication with the Bakufu. In this way company agents articulated complaints in the language of an aggrieved vassal and justified new requests by pointing to a long record of faithful service. When confronted with the possibility of new restrictions, their immediate response was to present themselves as wronged subordinates with an unblemished record of service who had been unfairly subjected to doubt through no fault of their own. Any hint of suspicion was met with an exaggerated sense of anguish: “It distresses us to learn what feelings the high authorities have to the Hollanders, especially as we are faithful vassals of His Majesty [the shogun], that are ready to risk our lives and goods [in his service], which we trust will be understood and recognized by His Majesty.”

21 A 1642 letter went even further, lamenting that the Dutch simply could not understand the shogun’s new restrictions because they had “always tried to serve the Japanese realm with humble dutifulness as faithful vassals.” So hurtful were these unwarranted suspicions that it was preferable to leave Japan than to be doubted by the shogun “as our faithfulness and sincerity … are as bright as the midday sun.”

22Such protestations meant little, however, if they fell on deaf ears in Edo or, worse still, produced the sort of interrogation that Nuyts and Muijser had been subjected to in 1627. But, whereas Tokugawa officials decisively rejected the ambassadors’ claims about the governor-general, they proved far more receptive to the presentation of the Dutch as vassals. Thus senior Bakufu representatives, the same officials who had dismissed de Carpentier’s letter to the shogun out of hand, showed no hesitation in responding to documents that presented the Dutch as loyal subordinates, accepting the parameters of the new vision apparently without dissent.

23 In the process they brushed aside past statements by VOC representatives in favor of the new consensus: If the Dutch wished to present themselves as vassals defined only by their connection to the shogun, the regime, which had its own interests in keeping its relationship with the company functioning, was quite clearly ready to consent, and there was no parallel to the relentless barrage of questions detailed in Nuyts’s diary.

This said, it would be a mistake to confuse consent with belief, and it is doubtful that any Tokugawa officials were genuinely convinced of the essential truth of these claims, particularly when they took the form of hyperbolic assertions about the willingness of Dutch representatives to shed their last drop of blood in service of the shogun. Rather the Bakufu displayed a clear willingness to accept these ideas as a framework for dealing with the company and organizing relations with its agents in Japan. Indeed, as will be discussed later, the regime was more concerned with maintaining the external appearance of devotion than with resolving the contradictions hidden behind the presentation of the Dutch as vassals.

What did it mean for VOC agents, who had once compared the governor-general to a sovereign king, to claim a place as the shogun’s vassals? At its heart, Specx’s strategy hinged on a basic denial of foreignness. In staking out a role as loyal subordinates, he argued that the Dutch no longer wished to be counted as outsiders but desired instead to take up a position alongside the shogun’s other subjects as “faithful vassals of His Majesty and not foreigners.”

24 The result was to pull Dutch agents in Japan into a domestic political landscape and shrink the boundaries of their world to one circumscribed by the shogun’s authority. Prior to his intervention, VOC agents had always claimed to represent a sovereign authority located outside Japan and had used this connection to assert their rights to negotiate with the shogun in the same way as the representatives of a more conventional state. Starting off as the Stadhouder, this external authority had by 1627 become the governor-general who wrote to Edo from his stronghold in Batavia.

Although such claims provided a way into diplomatic circuits, they also set a high bar for interaction, requiring Japanese officials to recognize the authority of castle Batavia as a starting point for engagement. Specx’s new presentation effectively removed any such requirement, for, to function smoothly, it required the shogun simply to consent to Dutch assertions that they were loyal vassals. In this way VOC agents became defined not by a connection to an external sponsor but rather to the shogun himself, thereby erasing the question—who exactly do you represent?—that had so plagued their past diplomatic efforts. The revised framework simplified the company’s role in Japan by taking it out of the business of official diplomacy. Whereas Nuyts had struggled to stake out a place for the organization within the Tokugawa diplomatic order alongside other sovereign actors, Specx opted simply to retreat to a new subsovereign category. Since they were tethered to a domestic overlord, vassals had no need to write diplomatic letters, to send embassies, or to prove their right to correspond directly with the shogun.

Although the decision to claim a role as vassals removed a series of hurdles, it also marked a retreat from rights the company took for granted in other parts of Asia. By 1630, when the idea of the Dutch as vassals was first aired, Batavia had been transformed into a diplomatic hub that stood at the center of an increasingly expansive web of international relations. Even if he was prone to exaggeration, Nuyts’s basic assertion that the governor-general was “of such a status that he sends ambassadors to the principal kings of China, Siam, Aceh and Patani; to the emperors of Java and Persia; to the Great Mughal” was grounded in fact.

25 Taking on a role as vassals signaled an implicit abandonment of these diplomatic prerogatives. Rather than trying to convince the Japanese of the governor-general’s capacity to send embassies, Specx resolved instead to shelter in the shadow of the shogun and abandon any claim for Dutch representatives to be treated in the same way as those of a more conventional state. It was not to prove a temporary withdrawal. After 1630 the company dispatched no further official embassies to Japan. There was thus no equivalent in Japan to the splendid VOC delegations sent from Batavia to India, Persia, and other powerful states across Asia.

26The scale of the concession was significant. For all its costs, and even though there was always a potential for failure, the embassy remained a vital policy tool for the VOC in Asia. For close to two centuries, formal diplomatic missions dispatched from Batavia with documents, gifts, and a clear set of aims remained the one weapon called into action whenever the company faced a crisis, hoped to secure a significant concession or simply wanted something from an Asian ruler. It was for this reason that de Carpentier had dispatched Nuyts in the first place, in order to defuse the escalating crisis over Tayouan, and why it continued to rely on such delegations whenever a serious problem arose. That Specx was prepared to take such a step—and his successors to confirm it—was a measure of the company’s desperation and a frank acknowledgement of the difficulty its representatives faced in securing sovereign recognition in Japan. Rather than, as Nuyts had done, endlessly protesting about the governor-general’s diplomatic rights, the company’s representatives chose to adapt by shifting course to secure an ongoing framework for exchange with the shogun. In this way, for all its success in stabilizing relations with Edo, the decision to abandon Batavia’s diplomatic prerogatives represented a significant retreat, the first in a number, from the trinity of powers laid out in the company’s 1602 charter.

Given the nature of the concession, it is not surprising that some VOC officials toyed occasionally with the idea of getting back into the embassy business, but these plans were swiftly quashed.

27 Strikingly, even when Bakufu officials specifically requested a new mission, the Dutch pulled back. To jump briefly ahead, this was the case after the Breskens incident, which has been superbly documented by Reinier Hesselink in his important 2002 book. In 1643 ten Dutch sailors were arrested after landing unexpectedly in the port of Nanbu in northern Japan. After they agreed to free these prisoners, Bakufu officials demanded that the Dutch arrange an embassy from Holland to thank the regime for its generosity.

28 Hesselink suggests, and he is surely correct, that the request came directly from the shogun himself and was prompted by a desire to parade a lavish embassy from the “king of Holland” through his capital.

Setting aside the fact that they believed the original arrest of their employees had been illegal, the request presented VOC officials with a problem. If the shogun wanted an embassy, one had to be provided, but what sort of delegation could possibly be sent?

By 1646, when the embassy was requested, the company was no longer prepared to make use of the “king of Holland” model of diplomacy, which had been abandoned across its area of operations. It was also, given its experience with Nuyts’s embassy, not willing to send a formal mission from Batavia equipped with letters and gifts from the governor-general. Confronted with this dilemma, it opted for a bizarre delegation headed by a dying ambassador who was dispatched with the expectation that he would succumb to his illness before he reached Japan, thereby muddying the waters enough to prevent any backlash when the embassy failed to meet Bakufu expectations. This so confused Tokugawa officials that they eventually concluded that although the surviving members of the embassy must be recognized in some way they could not possibly appear before the shogun and abandoned any further talk of an embassy from Holland. The result was to confirm the conclusion that Specx had reached years earlier, that there was no acceptable route back into the embassy business for the Dutch in Japan.

In the early 1630s, to return to the period under discussion, Bakufu officials displayed far more interest in securing a workable framework for interaction with the Dutch than in encouraging any thoughts of a new embassy. Because of this, they were quick to accept VOC documents organized around the notion of the Dutch as vassals and made no objections even to the company’s more florid claims. In fact, the Bakufu did more than simply tolerate this idea. Rather, it added a heavy ceremonial requirement to the company’s rhetoric, giving an unexpected weight to the idea first introduced by Specx and creating the conditions for the notion of the Dutch as domestic vassals to take on a life of its own within Japan

THE HOFREIS

In April 1634, the staff of the Japan factory learned that they were now expected to travel to Edo every year to pay homage to the shogun.

29 Although it came with little fanfare, this announcement marked the beginning of one of the most enduring ceremonial requirements for Europeans in Asia, the hofreis or the annual visit to court, that would continue essentially uninterrupted from 1634 to 1850. Described in hundreds of accounts, the hofreis, and particularly its ceremonial climax in which the opperhoofd pressed his face to the floor in front of the shogun, has become such a familiar feature of descriptions of the VOC presence in Japan that the exact reasons for its introduction have become blurred.

30 The result has been that while most scholars agree that the hofreis proper commenced in 1634, there is no clear consensus as to what prompted its development and why the visit to the court took on the form it did.

31 If we look more closely at the nature of these visits, however, it becomes clear that the hofreis was, in many ways, a direct response to the rhetoric of subordination; it served, quite simply, to place the company’s representatives in Japan in the role they had claimed for themselves. Because of this, its genesis lay in the shift in VOC diplomatic strategy that had taken place in 1630.

In 1634, when the Bakufu mandated annual journeys to Edo, two alternatives existed that were capable of providing a model for the opperhoofd’s visit to the court. The first was arranged around the state embassy. Although it included the first Dutch missions to Japan, this template was most closely associated with delegations from Korea and the Ryukyu kingdom that continued to arrive across the long expanse of the Tokugawa period. The embassy model incorporated four distinct features that were present regardless of where the delegation originated. The first of these related to timing. Embassies were not regular events. Instead, their arrival was triggered by special occasions such as the accession of a new shogun, making them extremely sporadic. Over a period of more than two centuries, only twelve delegations arrived in Japan from Korea, and even the more numerous missions from the Ryukyu kingdom just reached twenty.

32Second, embassies merited official support from the central regime. As soon as they set foot on Japanese soil, embassy processions, which often consisted of hundreds of participants, received financial backing, sometimes at a ruinous cost both to the Bakufu and the unfortunate domains that lay on their route through the archipelago.

33 Third, embassies arrived in Edo as the representatives of an external power. Although ambassadors could be influential figures in their own right, their primary role was to act as proxies for the sovereign, with the result that their most important responsibility was the delivery of the diplomatic letters they carried.

34 Fourth, once in Edo, embassies were incorporated into impressive ceremonies that climaxed with the presentation of official greetings in the castle’s audience chamber.

35 While these were designed to demonstrate the shogun’s position at the center of a Japanocentric order, they nonetheless accorded the ambassador, as the representative of an external power, considerable status.

Tellingly, the Dutch hofreis incorporated none of these features. Instead, it drew on a different template that had been crafted for the shogun’s domestic vassals and which was coming to final development at the exact moment when annual visits to court became a requirement for the opperhoofd. After the Bakufu seized power in 1600, it became an unwritten expectation for daimyo to make regular journeys to its headquarters, and by the time of Ieyasu’s death in 1615 many of these lords were frequent guests at the shogun’s court.

36 While this ensured periodic visits to Edo, the system was flexible as it hinged largely on the timetables of individual domains. This changed in 1635, just one year after the Dutch hofreis commenced, when the Bakufu issued an edict instructing the daimyo to “serve in turns [

kōtai] at Edo. They shall proceed hither [

sankin] every year in summer during the course of the fourth month.”

37 The order marked the beginning of the famous alternate attendance or

sankin kōtai system, which turned the daimyo visit from a voluntary act into a fixed obligation.

Although it also culminated in an audience with the shogun, the daimyo visit, as one would expect for a system organized for domestic subordinates, looked nothing like the model developed for embassies. It was, first of all, fixed according to a rigid schedule that saw most lords make annual visits to Edo.

38 Since all costs were borne by the domain, the arrangement effectively required individual daimyo to turn over a significant portion of their income funds to a repetitive cycle of travel. Once in Edo, these lords participated in ceremonies designed to hammer home a straightforward message of Bakufu dominance and domainal submission. In this way the sankin k

ōtai system provided a potent symbol of a much larger program in which, to use Eiko Ikegami’s description, the Bakufu “compelled the daimyo (who had originally held equal status) to accept a hierarchically structured relationship between them, with the shogun as the master and the daimyo as subordinate vassals.”

39The link between the Dutch hofreis and the sankin k

ōtai system was obvious to company employees, who instinctively made the comparison. Engelbert Kaempfer, a participant in two visits to the court, noted that: “all daimyo and shomyo, that is, all greater and lesser territorial lords, appear annually at the shogun’s court. They pay homage by offering their respects and presenting gifts: while the greatest of them—one could call them princes or petty kings—call on the shogun personally, the lesser are received by an assembly of councilors. This custom is also enforced upon the servants of our illustrious Dutch company.”

40 While Kaempfer was an astute observer of Japanese customs, it was a natural conclusion to reach with each stage of the hofreis closely matching its daimyo equivalent and incorporating a comparable dynamic of authority and submission. This fact becomes immediately clear when the two are set alongside each other. To illustrate this point it is possible to select almost at random, since the hofreis possessed a remarkable uniformity over its more than two centuries of operation, but as one representative example we can focus on Zacharias Wagenaer’s 1657 visit to the shogun’s court.

41 Until he was caught up at the end of his stay in Edo in the devastating Meireki fires, Wagenaer’s experience was utterly unexceptional, following a well-worn path that was in turn duplicated by dozens of his successors.

Wagenaer arrived in Nagasaki in August 1656 to take up his post as head of the Japan factory. Once the official handover had taken place in November, he began preparations for his trip to Edo, which formed the most pressing duty for any new opperhoofd. Unlike embassies, which required a special cue, the hofreis was a legal requirement that could not be ignored, substantially delayed, or significantly altered. It was thus a built-in function of the ongoing relationship between the company and the shogun. Like the daimyo, the various heads of the Japan factory were required to travel to Edo at regular intervals, but their timetable was in fact more onerous than that enforced on the majority of domainal lords. The classic sankin k

ōtai timetable saw most daimyo spend every alternate year in Edo while only a select group of minor fudai lords, who ruled over domains located close to the shogun’s headquarters were required to undertake annual journeys. Despite the distances involved between Edo and their base in Kyushu, the Dutch were instructed to make the journey to the shogun’s court every year, receiving exemptions only in the most extraordinary of circumstances.

42After making all the necessary arrangements, Wagenaer left Nagasaki on 18 January 1657 or the fourth day of the twelfth month in the second year of Meireki. The timing of his departure was important. As was the case with daimyo visits to court, the precise schedule of the hofreis evolved over time to become increasingly rigid. When it commenced in 1634, the Dutch were advised to arrive before the end of the Japanese year so they could be granted an audience in the first month of the Japanese calendar.

43 During the 1640s, audiences generally took place earlier in the eleventh or twelfth month, but by the time Wagenaer left Nagasaki they had been pushed back to the original schedule, usually occurring on the fifteenth or twenty-eighth day of the first month.

44 The timing allowed some flexibility, permitting the opperhoofd to choose when he wanted to leave, with the condition, of course, that he appeared in Edo at the right time. This leeway was erased, however, in 1660, when Bakufu mandated the fifteenth day of the first month as the required date for departure from Nagasaki.

45 The decision brought the hofreis into line with daimyo conventions, prompting Kaempfer to note that just “as the shogun gives every prince and vassal in the empire a day on which he has to set out and begin his annual journey to court, so the Dutch too are assigned a day for their departure. This is the fifteenth or the sixteenth day of the Japanese first month, which corresponds to February in our calendar.”

46Leaving Nagasaki, Wagenaer traveled by sea to Osaka before proceeding on land to Edo.

47 Whereas state ambassadors could count on the Bakufu’s support to defray any costs, the opperhoofd was required to pay for all expenses as he made his way through Japan. These were considerable. In Osaka, Wagenaer made arrangements to hire 85 bearers and 46 horses to transport his group to the shogun’s capital.

48 To these expenses were added the costs for accommodation (both on the road and in Edo), food, and miscellaneous items such as tea and tobacco.

49 Once everything was included, the total for Wagenaer’s hofreis came to the large sum of 15,893 guilders.

50 Given that a similar expenditure was required each year, it constituted an onerous burden on the factory, which was compelled to pay out regardless of the season’s trading profits. This said, the daimyo, who could not draw on the vast financial resources of a multinational organization to subsidize their journey to court, suffered far more from the requirement. For many of these lords, the expenses associated with the sankin k

ōtai system consumed a large percentage of their available income, draining away resources and requiring the accumulation of huge debts.

51After a relatively quick journey, Wagenaer reached Edo on 16 February 1657, just in time to notice smoke rising from the eastern side of the vast metropolis.

52 The next day he discovered that the audience had been set for 27 February or the fifteenth day of the first month. Although this was Wagenaer’s first experience of the hofreis, he would have known what to expect from his predecessors who had participated in almost identical ceremonies in the years since 1634. While it took a similar form to the daimyo audience, the ritual climax of the hofreis also marked out the opperhoofd’s unique status in the Tokugawa system. In Edo, low-ranking daimyo such as the lords of Hirado domain took part in mass audiences during which they prostrated themselves in a ritualized performance of submission before a shogun who was often partially obscured from view in a raised part of the audience chamber.

53 With no opportunity for deviation, the daimyo—powerful individuals in their own right—were reduced to the role of mute participants compelled to follow a script they had no power to alter. In contrast, the opperhoofd received the rare privilege of an individual audience, but this had more to do with his ambiguous position in the Tokugawa order than it was indicative of a particularly high status.

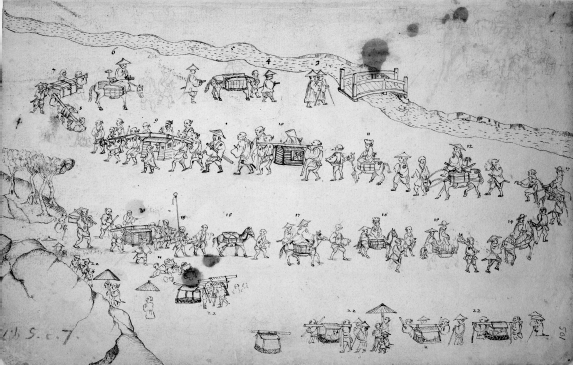

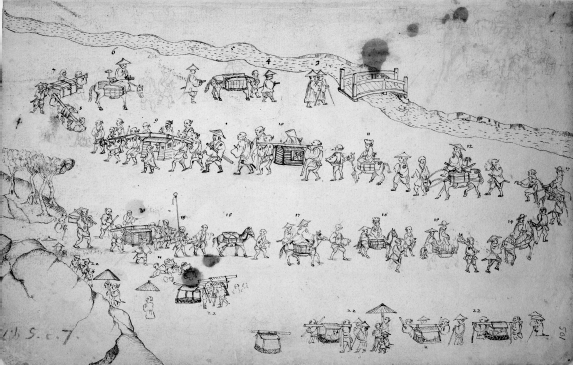

Figure 3.1. The Dutch procession to Edo. Courtesy of the British Library, Sloane Manuscript 3060, folio 501

Although it often required weeks of waiting, the actual audience lasted just a few seconds. In his diary Wagenaer provided a description of the ceremony, noting that “I pressed my face down, whereupon immediately I heard a loud cry ‘Holland Captain.’ With that the song and the ceremony came to an end.”

54 A more detailed account was provided by one of his predecessors who made the trip to Edo three years earlier:

I was suddenly summoned [after a two to three hour wait] to present myself before the Japanese monarch. I followed stiffly behind Sickingo [Inoue Masashige] and Quiemon [Kiemon Masanobu] through a covered passage and then went at a pace as the old commissioner called out occasionally, “Hurry, hurry.” We went round the outside of the palace and turned two corners, passing by a large hall with many lords and came to where our gifts had been placed. There I was instructed to bow down with my face to the planks (I did not even step onto the mats). Right across the hall the councilors and the shogun were standing and Ando Okiosamma [And

ō Shigenaga] loudly called out “Holland Captain.” If I was to say that I had seen this powerful lord more than I had heard, my heart would contradict it.

55

During the audience, the shogun stood in the furthest recesses of the audience hall, partially concealed from the opperhoofd by distance and lighting. The arrangement served to open up the maximum possible space between overlord and supplicant, who were positioned at opposite ends of the massive chamber. Determined to catch a better glimpse of the object of devotion, Wagenaer contravened instructions by deliberately raising his head as he stood up and managed in this way to make out a shadowy figure “standing in a dark place” across the expanse of the hall.

56As was the case across the duration of the hofreis, the Dutch representative was announced simply as Oranda kapitan or the “Holland Captain.” The designation was a telling one, for, in contrast to the embassy equivalent, it omitted any reference to an external figure standing outside Japan. The result was to define Wagenaer’s position within a domestic political order that was bounded by the shogun’s authority. Rather than a proxy of some greater power, he was announced simply as the captain of a small piece of territory within the shogun’s realm. The label was particularly appropriate after 1641 when the factory was moved from Hirado to the tiny man-made island of Deshima in Nagasaki harbor, which formed a self-contained Dutch enclave under the control of the opperhoofd. There, on a tiny speck of land measuring just 1.31 hectares or just over three acres, the “Holland Captain” presided over a kind of domain, complete with its own laws and administration, albeit one shrunk to a miniature scale.

Although the location of the audience is traditionally identified as the

ōhiroma or great hall, the exact placement of the ceremony could be more complicated than this. A key ceremonial space within the castle, the

ōhiroma was divided into six separate sections, access to which was regulated according to a strict hierarchy. Thus, for example, a low-ranking daimyo might offer reverence from one of the lesser sections of the hall, while a more senior lord could occupy a more elevated space.

57 The opperhoofd was, however, frequently pushed outside the walls of the

ōhiroma itself to the verandah (

ochien) that encircled it. This was the case with Wagenaer whose “gifts were,” according to

Tsūkō ichiran, “laid out on the verandah of the great hall and Hollanders made their greetings [from there].”

58 Gabriel Happart, who traveled to Edo three years earlier, noted that he was not allowed to step onto the mats of the great hall but had to press his face to the wooden planks of the verandah.

59

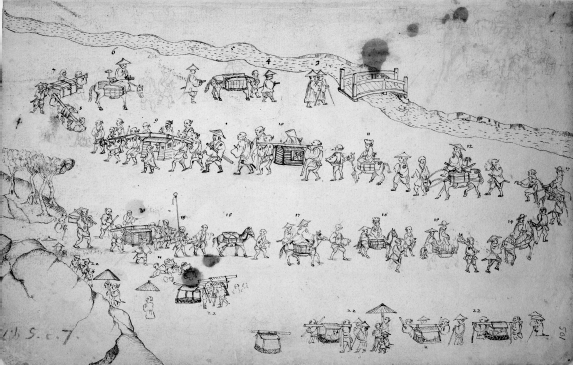

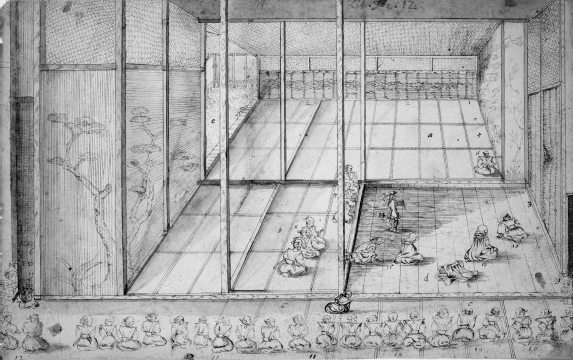

Figure 3.2. Kaempfer’s audience with shogun. This image shows a second, more informal meeting that took place after the official audience with the opperhoofd. Nonetheless it provides a good sense of the scale and layout of the great hall. As can be seen here, the Dutch were in this case given access to the hall itself. Courtesy of the British Library, Sloane Manuscript 3060, folio 514

The choice of this section, a liminal space both part and not part of the main audience hall, perfectly encapsulated the nature of the opperhoofd’s position. Simultaneously a daimyo and not, he was marooned on the peripheries of the great hall, a participant in the same ceremonies as the shogun’s vassals but without consistent access to the space used by his domestic counterparts.

60 At times the Dutch were pushed back even one step further to the uncomfortable edges of the

ōhiroma. When Wagenaer returned for a second audience in 1659, he offered his greetings on an outer walkway that ran round the side of the verandah.

61 The contrast with foreign ambassadors, who were permitted access to a far more prestigious section of the hall, is obvious, while there was, as Ron Toby notes, an additional divide in terminology. Whereas embassies were received “in audience” (

inken or

nyūetsu), the Dutch and their gifts were, in a further marker of their distinct status, simply “viewed” (

goran).

62

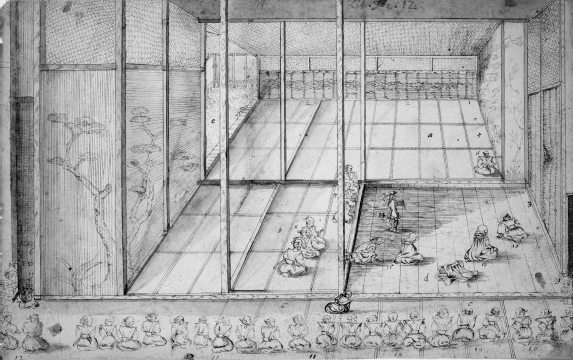

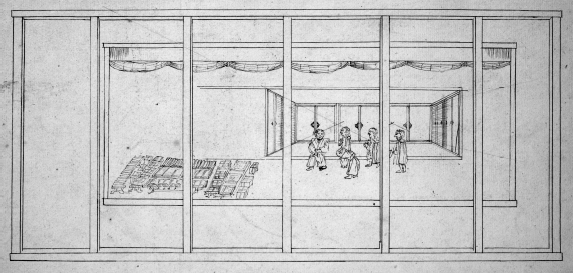

Figure 3.3. Audience hall with presents for the shogun. Courtesy of the British Library, Sloane Manuscript 3060, folio 512

During the audience the opperhoofd pressed his head to the floor alongside the company’s offerings for the year. In dutch records these are described as

schenkagie, or gifts, a generic designation that gives little sense as to what the items actually meant in this context. Japanese sources are clearer, routinely describing these items as “tribute” (

nyūkō or

kenjō butsu).63 Rather than embassy gifts presented as a token of friendship from one sovereign to another, these were ritual items offered from vassal to suzerain. In this way they parallel the offerings made by the daimyo who were also required to give tribute, usually known as

sanpu kenjō, when they arrived in Edo.

64 Since bonds of fealty were meant to be reciprocal, the shogun responded with his own gifts in the form of seasonal clothing, or

jifuku, that were presented to the opperhoofd at the conclusion of his stay in Edo. According to a later account from 1664: “He [the Nagasaki

bugyō, Shimada Ky

ūtar

ō Toshiki] indicated three large present trays that lay a little way away from me. On each of these were ten dresses (

rocken). He said that these were the return gifts of his majesty, which must be accepted and taken away. After giving my thanks, I crawled over to the middle tray of the three and lying down with my face on the ground placed the sleeve of one of the aforementioned dresses against my head.”

65 For the Dutch, such objects, which possessed little or no commercial value outside of Japan, were frustrating as they offered no way to recoup the expenses involved in the hofreis but, as the description makes clear, they recognized the heavy symbolic weight of the transaction and acted accordingly. Once again, the parallel was with the daimyo, who received similar items when they headed back to their domains.

66While the audience represented the climax of the hofreis, it did not signal the end of the opperhoofd’s stay in Edo, and there was one further reminder of his role as ersatz vassal. Throughout the 1640s, Bakufu officials periodically issued the Dutch factory with instructions to avoid contact with the Portuguese and to make sure that no Japan-bound ships carried missionaries or Christian paraphernalia. In 1659 this practice was transformed into a formal set of written orders that were issued to the opperhoofd at the conclusion of his stay in Edo. During his second stint in Japan, Wagenaer was called back to the castle ten days after his initial audience and brought again to the verandah where he had prostrated himself before the shogun. There he was presented with a set of orders that were read out by a court functionary in the presence of four senior Bakufu officials.

67 The exact content of these orders varied over time, gradually gaining new clauses until they eventually assumed a settled six-part form in 1673. Of these six parts, which were continually issued to VOC representatives across the long history of the hofreis, two stand out in particular.

68First, the Bakufu prohibited the Dutch from having any dealings, whether political, commercial, or diplomatic, with the Portuguese, who had been expelled from Japan in 1639. To help police the provision, the regime ordered the company to supply it with a list of possible contact points where the Dutch might encounter the Portuguese so it could investigate any rumor of correspondence between the two nations. Second, and arguably more important, the opperhoofd was ordered to report any news about Catholic expansion into new territories or planned voyages to Japan. This requirement translated over time into a formal intelligence report that was delivered annually to Bakufu officials in Nagasaki. At first focused on the Iberian powers, these documents, which came to be known as the

Oranda fūsetsugaki or “reports of rumors from the Dutch,” became steadily more expansive until the company was required, in the words of one opperhoofd, to provide “general news, including reports of wars, peace, battles, victories, successions, the death of kings, and other such things, [which] is presented and written down by the interpreters.”

69 Starved of information from other sources, the regime came to rely on these reports as a vital conduit for intelligence, and their focus was adjusted according to the Bakufu’s own preoccupations, shifting from a seventeenth-century obsession with Catholicism to a nineteenth-century concern with the rising tide of Western imperialism.

70 As such, the

Oranda fūsetsugaki formed a concrete and highly visible emblem of the company’s ongoing service that was offered up year after year without respite.

The regime’s six-part orders, another item that had no place in an embassy, further reinforced the link with the daimyo, who like the opperhoofd returned from Edo with instructions from the shogun. The annual reading out of these orders provided yet another occasion for the company’s representative to act out his designated role as loyal subordinate. During the ceremony he was required to wait in respectful silence by kneeling with his face turned downward and, once it was completed, he was then to respond with an enthusiastic affirmation of loyalty.

71 One opperhoofd declared that “we would obey the instructions of the emperor [shogun] and would always try to serve the Japanese realm,” while a second explained that “the emperor, the councilors, and the whole of Japan could be certain of our loyalty to the realm.”

72In these ways the hofreis, which drew on daimyo practices, treated the Dutch as domestic vassals tied directly to the shogun. Because of this, it would be a mistake to dismiss the connection between what Specx and other VOC representatives were saying about their place in Japan and the reconfigured form of the court visit as coincidence. Rather, the inception of hofreis was inextricably bound up with the company’s post-1630 strategy, which deliberately positioned its employees in this role. But, if it stemmed originally from a VOC policy, the hofreis was also a new development that pushed the Dutch down an unfamiliar road. The initial formulations of the rhetoric of subordination were comparatively loose and lacked any real detail. Even more importantly, they were conspicuously devoid of any real obligation beyond the need to repeat vague declarations of loyalty. When it mandated an annual visit to Edo that ran in parallel with sankin k

ōtai conventions, the Bakufu gave the idea of the Dutch as domestic vassals physical form by providing the opperhoofd with a fixed script that he was required to follow. The result was to add a heavy ceremonial burden to what had previously been little more than a convenient fiction designed to smooth over potential difficulties with the regime.

All of this raises some obvious questions. How could the Dutch be so palpably foreign, the subject of wondrous accounts in Tokugawa period literature, and yet assume a role as domestic vassals? If their primary connection was with the shogun, what about the Dutch “king” in Holland or the governor-general in Batavia, both of whom Bakufu officials continued to refer periodically to?

73 Finally, how could the opperhoofd act (and be treated) like a daimyo if his domain extended to just a handful of Dutch employees who made up the factory’s permanent staff? To understand how this string of obvious contradictions could be tolerated requires a brief examination of the nature of the Tokugawa regime, which displayed a surprising capacity to accommodate such paradoxes.

The Tokugawa Bakufu has always resisted easy characterization. At its heart lay a basic contradiction between the existence of a central government that claimed dominion over the archipelago and dozens of semi-autonomous domains, which retained considerable financial, military, and legal power. Indeed, it is precisely because of this basic paradox that historians sometimes make use of oxymoronic designations to define the regime. Edwin Reischauer, for example, famously described the Tokugawa state as an example of that rarest of political oddities, “centralized feudalism,” a regime that was never properly centralized nor fully feudal.

74 Recent studies have shown that these contradictions extended beyond the basic structure of the regime to the way it operated from day to day. Of most relevance to this discussion is Luke Roberts’s groundbreaking work, published in 2012, which focuses on the Bakufu’s interactions with the domains.

75 Although the daimyo appear in Tokugawa sources as undifferentiated and perfectly regimented servants of the regime, their relationship with the Bakufu incorporated a mass of contradictions. Thus, as Roberts has shown, one daimyo might be both dead and alive in order to facilitate a successful adoption, while another might supply false or misleading information about the condition of his domain “with the full complicity of Tokugawa officials,” who supposedly prized accurate intelligence on precisely these questions.

76For Roberts, this willingness to tolerate seemingly obvious contradictions stems from a crucial but largely neglected distinction between two key concepts,

uchi, the (often) hidden inside, and

omote, the outside facade presented to the world, that were integral to the functioning of the Tokugawa state. The Bakufu’s governing dynamic relied on keeping these two categories separate, allowing the domains considerable autonomy within their own spaces of operation as long they preserved the outward illusion of perfect subservience. This translated into a preoccupation with performance; Roberts writes that the “ability to command performance of duty—in the thespian sense when actual performance of duty might be lacking—was a crucial tool of Tokugawa power that effectively worked toward preserving the peace in the realm.”

77 Because of this, the regime was prepared to tolerate a range of otherwise disruptive behaviors within the domain’s interior spaces as long as they were hidden behind an unblemished performance of subservience.

On the other side of the equation, the daimyo were able to adopt multiple identities that changed according to situation and audience. In Roberts’ words, “the identity and subjectivity of actors changed radically, depending upon whether they were operating in an

omote space or an

uchi space, and reveals that the character of political units themselves were likewise expressed differently according to

omote and

uchi.”78 By recognizing that one language was used within the domains while a second quite different set of terms and ideas could appear in documents exchanged between the regime and the daimyo, Roberts is able to reconcile the apparently conflicting identities of Tokugawa period domains, which sometimes appear as independent political units, that is, states or countries in their own right, while also seeming, when viewed from a different perspective, nothing more than subordinate components of the Tokugawa system and subsovereign parts of the national polity.

79The distance between a daimyo who might be simultaneously both living and dead or a domain with a dual political status and the opperhoofd’s unusual place in Tokugawa Japan is not as far as it may appear at first. Indeed it is precisely the same distinction Roberts describes, a division between an inside or

uchi identity and the outside or

omote facade, that enabled the company’s rhetoric of subordination to function. The opperhoofd’s actual status and whatever he did or said within the walls of the Japan factory were less important than the conduct of the company’s representatives in Edo and their willingness to stage a perfect performance of subservience. And it was in this sphere that, after the commencement of the hofreis in 1634, the Dutch proved consistently reliable. In contrast with Nuyts’s and his botched embassy,

opperhoofden like Zacharias Wagenaer became adept at following the script that was provided for them by the regime. If, as Roberts maintains, the “key demands of the Tokugawa were for everyone to hold up a front of compliance and respect and to see that disorder did not erupt into the outside of their realms,” then the company’s representatives had by this point learned to excel in precisely this department.

80This sense of dependable performance was reflected in Tokugawa sources recording Dutch visits to the court after 1634.

81 In these brief accounts, the Dutch are depicted as devoted and predictable servants, arriving in Edo at the right time, performing the appropriate ceremonies, and leaving when they were told to do so. Although the entry for each year is slightly different, they follow the same basic pattern: The Hollanders (

ranjin or

orandajin) arrive in the castle with their tribute (

nyūkō), which is subsequently viewed (

goran) either by the shogun or senior officials (if he is not available), and the audience concludes.

82 From the regime’s point of view, the

omote illusion of perfect subservience was thus preserved, leaving the opperhoofd free, as his domainal counterparts were, to maintain a different

uchi identity as long as it did not breach the surface and disrupt relations with the Bakufu.

Maintaining this illusion, however, required considerable effort for the company and its representatives. When the hofreis commenced in 1634, its first participants expressed no particular distaste for the new arrangement. To the contrary, the initiation of regular court visits was welcomed by the Dutch as the clearest sign that relations with the shogun had finally begun to stabilize after years of difficulty. But this sense of satisfaction gradually faded as the years dragged on without any loosening of the requirement. By the 1650s, when zacharias Wagenaer completed his two visits to the court, the hofreis, with its exaggerated marks of subordination and unrelenting time line, had become increasingly unpalatable, wearing down its primary participants, whose resentment bubbled to the surface of their diaries. In 1654 one opperhoofd lamented that “this is what we usually call the audience before the Japanese Majesty. It would be better to call it reverence (or better still) submissive performance, abject humiliation or another kind of vile homage [homagie].”

83 But as much as they protested in internal documents, Dutch agents in Japan recognized that they possessed no power to alter the form of the ceremony or the requirement for annual performance.

At first glance, the sheer durability of the hofreis is difficult to grasp. It remained an annual requirement for over 150 years, until 1790, during which time the Dutch made a total of 167 visits to the court.

84 In 1790 the Bakufu finally reformed the system, but only by shifting the hofreis from its annual basis to once every 5 years, leaving the form of the ceremony unchanged. As a result, the last hofreis only took place in 1850, just 3 years before Perry’s fleet arrived in Edo bay. As such, it outlasted the Dutch Republic and the company itself, which collapsed at the end of the eighteenth century. Across this period the nature of the ceremony remained remarkably consistent. Despite the momentous political changes that had occurred in the intervening years since its creation, the nineteenth-century hofreis would have been immediately familiar to individuals like Wagenaer.

This is clear from the account of one opperhoofd, Hendrik Doeff, who made four visits to court in 1804, 1806, 1810, and 1814. Like his seventeenth-century predecessors, Doeff departed Nagasaki on a fixed day, traveled along a familiar route to Edo, and once there participated in an unchanged ritual, although he was at least given access to the ōhiroma itself:

Through a wooden gallery, I was escorted to the

hall with the hundred mats…. I went alone with the governor of Nagasaki into the audience hall where I found the presents at my left hand side…. I paid my respects in the same manner as all the princes of the realm do, whereupon one member of the government council introduced me by calling out: Oranda kapitan. After this, the governor of Nagasaki who stood a few feet behind me pulled at my cloak to indicate that the audience was over. The whole ceremony took at most one whole minute.

85

Tellingly, Doeff also made the link with the daimyo, noting that he paid his respects “in the same manner as all the princes [daimyo] of the realm.”

86 Returning to the castle a few days after the audience, he received the Bakufu’s standard six-part set of orders, including outdated warnings about contact with the Catholic powers. In this way, and though separated by a significant span of time from the original presentation of the Dutch as domestic vassals, a nineteenth-century opperhoofd was compelled to act out the role that had first been outlined in Specx’s letter so many years earlier. Once claimed, the role could not be, Doeff’s experience makes clear, easily discarded.

While the hofreis gave physical form to the company’s rhetoric of subordination, it was not the only instance in which VOC agents were called upon to pair their words with deeds, and eight years after Specx’s letter the Dutch found themselves unexpectedly involved in military operations against the shogun’s enemies. The company’s participation in the campaign to put down the Shimabara uprising, a domestic rebellion with a significant Christian element that commenced in 1637, has long attracted controversy. For (usually non-Dutch) critics, the willingness of the company to assault fellow believers in the service of a foreign potentate was unforgivable. Kaempfer, a German by birth, lamented the company’s involvement as despicable while a later American writer described it “an act … too clearly proved to admit of denial, and too wicked and infamous to allow of palliation.”

87 In contrast, Dutch writers, including a number who worked in the Japan factory, have vigorously protested the tendency of “ignorant foreigners … [to] put this matter in the most despicable light” by arguing that the VOC opperhoofd was called upon simply to lend assistance against domestic insurgents.

88This back and forth between accusation and defense brings us no closer to explaining why the company was involved in the first place. One explanation put forward by modern scholars suggests that the Dutch were the victims of a test engineered by Bakufu officials to make sure they could be completely trusted.

89 If the Dutch were prepared to turn their guns against fellow believers, they could, so the reasoning went, be relied upon to fully submit to the shogun’s anti-Christian prohibitions. But this explanation, though certainly neat, relies on an assumption that Bakufu officials, in the middle of putting down the first major challenge to the regime’s authority in decades, paused to orchestrate a test of loyalty for a minor foreign group. The theory becomes even less convincing when it is traced back to its origins, a comment supposedly made by a Bakufu commander that was later reported second or third hand to the Dutch.

90To understand the factors that propelled the company’s involvement in the uprising requires first a damping down of some of the associated rhetoric.

91 When separated out from some of the more knee-jerk accusations of Dutch wickedness, the facts of the case are not as shocking as some writers make them seem. While Shimabara was in part a Christian uprising, it was also a Catholic one, sparked by decades of Jesuit proselytizing in Kyushu. By 1638, when the company opened fire on the rebel encampment, it had been engaged in a vicious war against Portugal and Spain, the Catholic powers in Asia, and their local allies for almost four decades. Back in Europe, its home state, the Dutch Republic had been fighting for survival against Spanish incursions for considerably longer. The Dutch crew that manned the vessel dispatched to Shimabara were thus no strangers to violence directed against Catholic targets, and there was no special immunity conferred on the rebels by their Christian faith.

And yet it is nonetheless surprising that the company, an organization that consistently refused to devote resources to nonessential military campaigns, was willing to commit ships and men to the suppression of a domestic revolt that offered no direct benefit to its bottom line while consuming valuable resources and disrupting its trading schedule.

92 The precise way in which the commitment materialized also demands explanation. Rather than being trapped by a Bakufu test, the Dutch volunteered to act, and they did so by citing their responsibilities as the shogun’s loyal vassals. At the same time, the interactions between VOC agents and the Bakufu officials tasked with the suppression of the revolt were coated with a thick layer of the kind of rhetoric first introduced by Specx in 1630. All of this suggests that a direct line can be drawn from events at Shimabara to the shift in diplomatic strategy described in this chapter. Indeed, the ways in which the organization responded to the uprising provides some of the clearest evidence yet as to how central the notion of a lord-vassal relationship had become to the company’s interactions with the shogun.

The ease with which talk about loyal service could morph into a commitment to actual action first became clear some months before the opening salvos were fired at Shimabara. In the second half of 1637, officials in Nagasaki began to hint with increasing boldness that the Dutch should volunteer for an ambitious scheme to attack the Spanish colonial city of Manila.

93 The proposed assault was intended as punishment for the sinking of a Japanese ship carrying a Bakufu-issued trading pass by a Spanish fleet years earlier in 1628.

94 It followed on from a earlier attempt to attack Manila, which had been organized in the immediate aftermath of the incident but had failed when Matsukura Shigemasa, the daimyo placed in charge of scouting out the city’s defenses, died leaving no obvious replacement.

95 In 1637, however, the plan was resurrected by officials in Nagasaki who saw an opportunity to curry favor with their superiors in Edo by presenting a low-cost way to take revenge on the Spanish through the pairing of Japanese military might with Dutch maritime technology. It was rendered still more attractive by its promise to permanently shut down the missionary pipeline from Manila, which had become an increasing source of concern for Tokugawa officials.

In September 1637 the two Nagasaki governors (

bugyō), Baba Sabur

ōzaemon Toshishige (in office 1636–52) and Sakakibara Hida-no-kami Motonao (in office 1634–38) learned from some captured Dominican friars that the colonial government in Manila was planning to send a steady flow of missionaries into Japan.

96 They responded to the threat by maneuvering to pull the Dutch into a proposed campaign against Manila. On 30 October the bugy

ō made their opening gambit when they asked the opperhoofd why the Dutch allowed “Manila to remain unmolested.” If the city was attacked and destroyed, it would, they explained, greatly please the shogun.

97 The implication was clear: as faithful servants of the regime, the Dutch should anticipate the shogun’s wishes and volunteer their services for a campaign against his enemies. While the company was, of course, at war with the Spanish, the governors’ plan carried with it huge risks. Since its establishment in 1571, Manila had become one of the best-defended European enclaves in Asia, fortified with thick walls mounted with heavy cannon and manned by a large garrison.

98 A failed offensive could devastate the company’s fleet, causing large numbers of casualties and permanently disrupting its trading activities. Keenly aware of these perils, the opperhoofd resisted the bugy

ō’s suggestions by explaining that the Dutch were more merchants than soldiers and lacked the resources necessary to mount such a campaign.

The next day the lobbying campaign was renewed by a subordinate official, the Nagasaki magistrate (daikan), who explained that he had prepared a petition for the Dutch to sign and submit in their name to Edo. Framed in the language of the loyal vassal eager to serve his master, the document volunteered the company’s ships, men, and ordinance for the campaign in unambiguous terms:

Recently, we [the Dutch] have understood that the people of Manila are breaking the emperor’s [shogun’s] prohibitions and are sending priests, who are forbidden in Japan. As a result, they are viewed as criminals (

misdadigen) by Your Honors. If the high Authorities decide to destroy this place, the Hollanders, who bring a good number of ships to Japan every year, are always ready, in time or opportunity, to present our ships and cannon for your service. We ask that Your Honors trust and believe that we are, in all matters without exception, ready to serve Japan. For this reason, we are presenting this to Your Honors.

99

The document was rife with potential dangers. Once put into writing and dispatched to Edo, the promise to provide military support could not be retracted, with the result that the petition amounted to a contract pledging Batavia’s men and ships if the regime decided to revive the planned attack against Manila.

Unwilling to make such an open-ended commitment, the factory’s representative demurred by explaining that such an important matter had to go up the chain of command to the governor-general before it could be approved. Clearly expecting such an answer, the magistrate demanded that the company make good on its promises: “How cowardly. What are you saying? I do not wish [to know] of your ways and surely you do not wish that the regents [bugy

ō] hear this answer. You should rightly say ‘O happy time that we have wished for so long. Now we can show his majesty [the shogun] that we are ready to serve Japan.’ I want to tell you the results of what will happen if you refuse. First, you will be thought of as unwilling liars as you always say that you are ready to serve Japan with all your might.”

100 Going on, he explained that he had always told his superiors that the Dutch were trustworthy and stood ready to serve the shogun with their “strength, ships and ordinance, indeed so faithfully and furiously as one of the lords of his Majesty’s own land.” If, having already promised so much, they were now to refuse service, their claims would “be known to be a lie”

101Although they came from the mouth of a Japanese official, the remarks almost perfectly parroted the sentiments voiced by VOC representatives, and they provide some sense of how widely the idea of the Dutch as vassals had spread. But, while repetition reinforced the company’s own presentation in useful ways, it also indicated how little control the Dutch in Japan retained over its central logic. By 1637, as the

daikan’s comments make clear, the ideas first introduced by VOC agents could no longer be restrained and the company’s rhetoric had become accessible to a range of groups with their own interests. By simply reciting VOC declarations of loyalty, the magistrate offered a script for the Dutch to follow, demanding, as was the case in the hofreis, that they act out the role they had claimed for themselves.

In the factory the governing council convened to discuss the petition. Its members quickly recognized the precariousness of their situation, caught between the risks of having their claims exposed and the danger of military participation. The petition could not simply be dismissed, for doing so would amount to an admission that past protestations about their willingness to serve had been a sham. This would cause, the members of the council lamented, the Dutch to be regarded as “liars and unwilling people” because they had offered “our assistance and service to Japan many times before this.”

102 On the other hand, the council was understandably reluctant to make an open-ended pledge to commit the company’s “naval might of ships and weapons to the service of Japan.” With neither prospect particularly appealing, the final decision was in favor of giving in. Concluding that it was more dangerous to contradict promises already made than to offer support, the council resolved to volunteer six vessels, four ships, and two yachts for the attack.

103Before any steps could be taken to realize the Manila plan, events in Shimabara intervened to turn the Bakufu’s attention to domestic issues. On 17 December, word reached Hirado “that the residents or the peasants of the territory of Arima have rebelled and are fighting against their lord.”

104 The revolt had been prompted by rising discontent with the high taxes ordered by the local daimyo, but the wider area was a tinderbox ready to spark into flames, and the uprising quickly spread to Amakusa Island where hundreds of villagers took up arms. As it grew, the rebellion began to draw on support from hidden Christians eager to escape Tokugawa persecution. In Hirado the Dutch received word that villagers were burning shrines and temples, erecting in their place churches adorned with images of Jesus and Mary.

105 Poorly armed and badly supplied, the rebels quickly ran into resistance and, after suffering a series of setbacks, elected to make their stand in Hara Castle, an abandoned fortress in Shimabara domain. Surrounded on three sides by the sea and guarded by thick walls, the fortress was, even in its crumbling state, a formidable stronghold, and there thirty thousand men, women, and children gathered to await the inevitable response from Edo.

The rebellion shocked the Tokugawa regime, which found itself faced by a challenge to its authority from an unexpected quarter. It responded by dispatching Itakura Shigemasa at the head of a large force to crush the uprising and restore order. Moving as fast as it could, the army reached Kyushu around the middle of January 1638.

106 Given the recent discussion over the Manila campaign and the immediacy of the threat to Tokugawa authority, the opperhoofd, Nicolaes Couckebacker, was left with little choice but to immediately offer his support. In a letter dated 17 January he did so in unequivocal terms. Adopting the by now well-worn language of the faithful vassal, he assured Itakura that “if you need anything, that is within our capabilities, please command as we are always ready to serve faithfully.”

107 The result was to volunteer the company for service in the campaign while making it clear (without any prompting from Tokugawa officials) that the Dutch were prepared to play their designated role as loyal subordinates.

It did not take long for the first request to arrive. On 27 January, the Nagasaki magistrate wrote to Couckebacker asking him to send a large quantity of gunpowder to supply the Bakufu forces gathering near Hara Castle.

108 Having dispatched six barrels of gunpowder, Couckebacker decided on 5 February to make another offer of service, this time to the Nagasaki bugy

ō, who was stationed with the main force of Bakufu troops: “With respect, we send Your Honors this letter…. We have prepared a supply of cannon and shot in case your Honors deem it necessary. We shall supply it whenever Your Honors order…. If there is anything without exception that the Hollanders are capable of serving Your Honors in, please command us.”

109 The offer prompted another request with Couckebacker receiving instructions on 10 February to send additional gunpowder as well as five large cannon to Shimabara. Writing back to the Nagasaki magistrate, he boasted that he had dispatched the most powerful guns at his disposal for service in the shogun’s campaign.

110While this exchange was going on, Itakura’s campaign stumbled from one setback to another. Two assaults succeeded only in producing large numbers of casualties without making any inroads into the rebel fortification. unhappy with the progress of the campaign, Edo decided to replace Itakura with two new generals, Matsudaira Nobutsuna and Toda Ujikane. By the time they arrived, Itakura was dead, killed in a third—and equally fruitless—assault launched on 14 February. Recognizing that a frontal attack was unlikely to succeed, Matsudaira and Toda opted instead for a prolonged siege. It was at this point that the Dutch were called upon to redeem their promises, and on 19 February the opperhoofd was instructed to send all available “ships and cannon” for service in the siege.