KAREN GRIGSBY BATES

JOHN LEWIS and BAYARD RUSTIN with other members of CORE and SNCC, speaking at the Freedom Vote trial run, Newport Folk Festival, 1963

MILLIONS HAVE SEEN JIM MARSHALL’S ROCK PHOTOS, but very few people know the other side of his work, the humanitarian side. I hadn’t seen it until recently, and I was shocked at how beautiful these images are. (I can hear him now: “Why the hell are you shocked, Bates? I took ’em, didn’t I?!”)

The same year Jim shot the now-iconic photo of a very young Bob Dylan playfully rolling a tire down a street in Greenwich Village, 1963, would also see him chronicling a dry run for the March on Washington at the Newport Folk Festival. Peter, Paul, and Mary were performing there, as well as Judy Collins, John Lee Hooker, Pete Seeger, and Jim’s good friend, Joan Baez. He went for the music and stayed for the meetings.

At these meetings, activists Bayard Rustin, James Forman, and a young John Lewis consulted with other movement strategists to find out what would work and what wouldn’t for the grand civil rights march planned for the end of August in Washington, D.C. Jim’s photos show the men (and let’s be honest, they were almost all men) dressed in white shirts and dark ties, deep in conference. He also photographed groups of people, black and white, marching purposefully through Newport’s streets. Back then—especially on non-Festival days—you couldn’t get much whiter than Newport. The city’s glowing Beaux Arts “cottages” were silent witnesses to the dress rehearsal for the march that soon would occur before the marble government buildings and monuments in the nation’s capital—when Joan Baez’s silvery soprano would lead a quarter of a million people in “We Shall Overcome.”

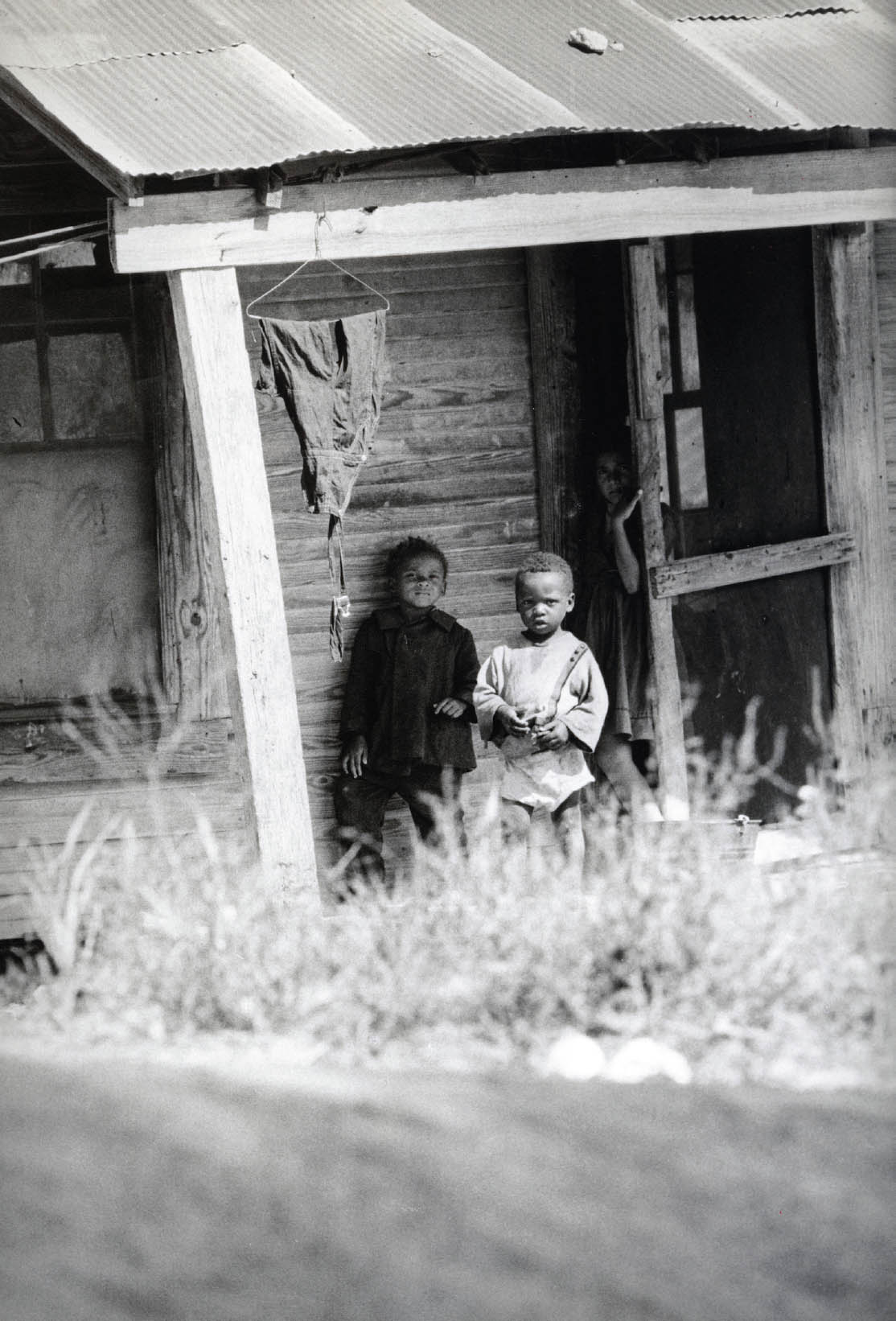

Jim also spent part of the summer of 1963 in Mississippi, recording another trial run, this time for the Freedom Summer of 1964. This was an effort to register black citizens—most of them poor, many of them generations-long residents of their small towns—who had consistently been denied their most basic constitutional rights. Jim took photos of fathers in overalls holding children close in the dusty front yards of their tarpaper-roofed homes. A series of shots show a sleeping infant on a battered cot in a room with walls made of discarded wooden doors.

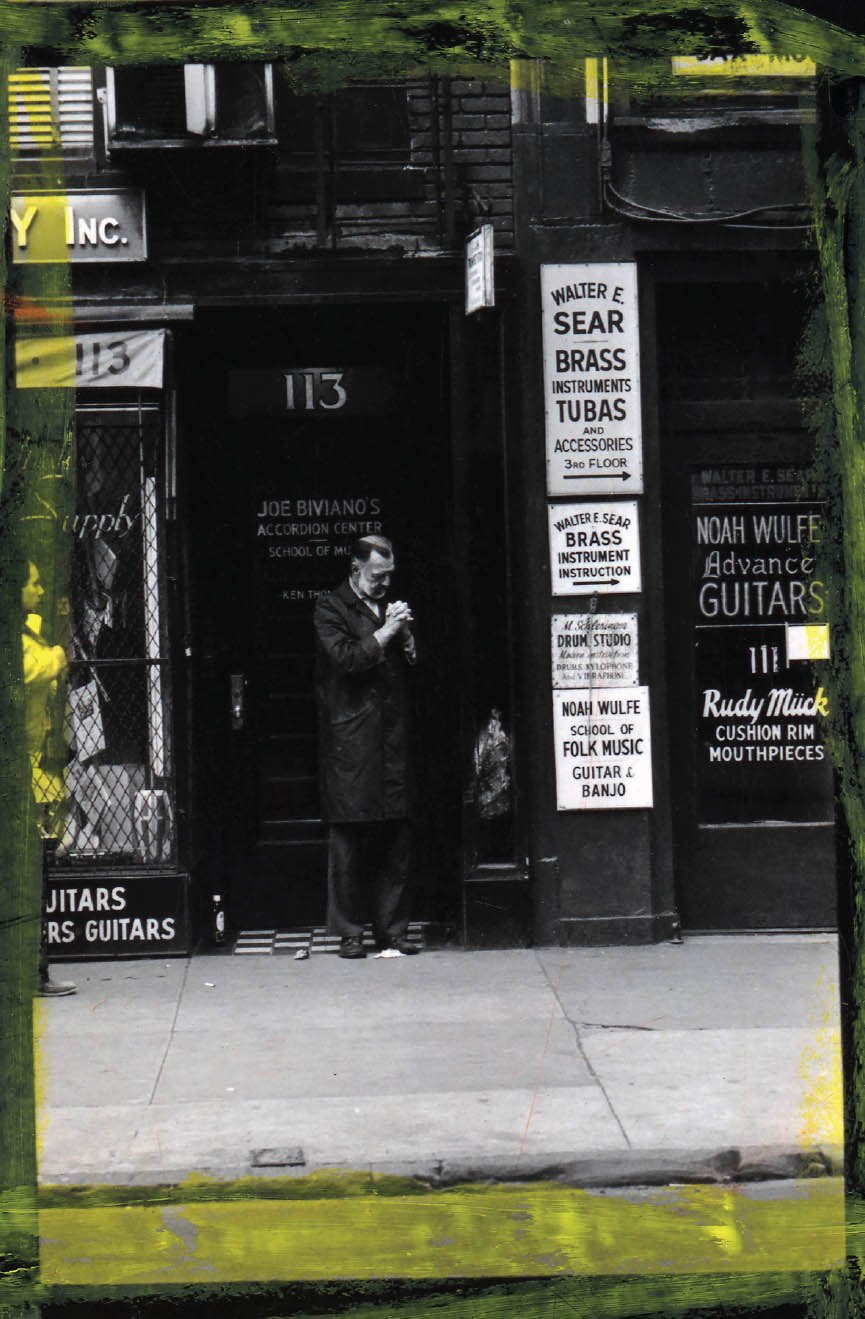

But after the triumphal optimism of the March on Washington came the fall of 1963. Jim was in New York in the Time-Life Building, probably hanging out and jawing with other photographers, maybe angling to see one of the photo editors, when news broke that President John F. Kennedy had been assassinated in Dallas. Jim probably grabbed his Leicas, hopped in the elevator, raced to ground level, and waded out into the crowded midtown street to record people’s shock and disbelief as the news began to spread. The resulting photos—of a dazed woman clutching her pearls, a stunned man sitting on a stack of papers at a newsstand, an older man in a doorway, hands raised in prayer—permanently crystallized the shock many of us felt when we heard the awful news.

In the summer of 1964, Jim was in Mississippi again. He took a lot of photos of community life. His crisply defined black-and-white photos show carefully dressed ladies in a voter education class, primly standing behind their wooden chairs. Other shots highlight the modest headstones in a segregated country graveyard (“Ida E. Proctor, 1877–1929 . . . Mother of Five Children”), and a laundry with the word “COLORED” boldly painted on its front door. (Looking at these and Jim’s other social documentarian work, I am reminded of the cool elegance of the great Walker Evans. With writer James Agee, Evans had traveled through some of the same territory about thirty years earlier to produce starkly moving photographs of white tenant farmers during the Depression for Fortune magazine.)

Jim’s pictures recorded the circumstances of these impoverished lives without demeaning the people who led them—no small feat. It was documentation without voyeurism, and it couldn’t be done without the trust between him and his subjects that would become his signature. The people in these small Delta towns opened their homes to him.

He, in turn, showed them a courtesy local white people couldn’t—or dared not. He addressed the men as “Sir” and the women as “Ma’am” and spoke to them without condescension. They might have wondered about this strange white guy from California who had waded into their lives. But they let him in and trusted him to treat them fairly.

On one occasion, Jim visited Mrs. Fannie Lee Chaney, taking portraits of her and her children as she waited to hear about the fate of her son James. He’d disappeared with fellow volunteer Mickey Schwerner and new arrival Andrew Goodman weeks earlier, as they joined local residents to begin a historic and dangerous effort to register black voters. The summerlong education and registration drive brought students from the North down to the Delta to work with the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC) and the Congress of Racial Equality (CORE). Leaders like James Forman figured, correctly, that the presence of white organizers in Mississippi would capture national attention in ways that the state’s black organizers could not.

The state’s white power structure had already boasted of their intent to meet enfranchisement efforts with whatever violence would be necessary to maintain the status quo. Black Mississippians feared the worst, even as they tried to hold onto a shred of hope. Jim was with the Chaneys when the news came that James’s brutalized body had been pulled out of a bulwark of a dam that was being constructed in Neshoba County (the same Neshoba County in which Ronald Reagan would announce his presidential candidacy four decades later).

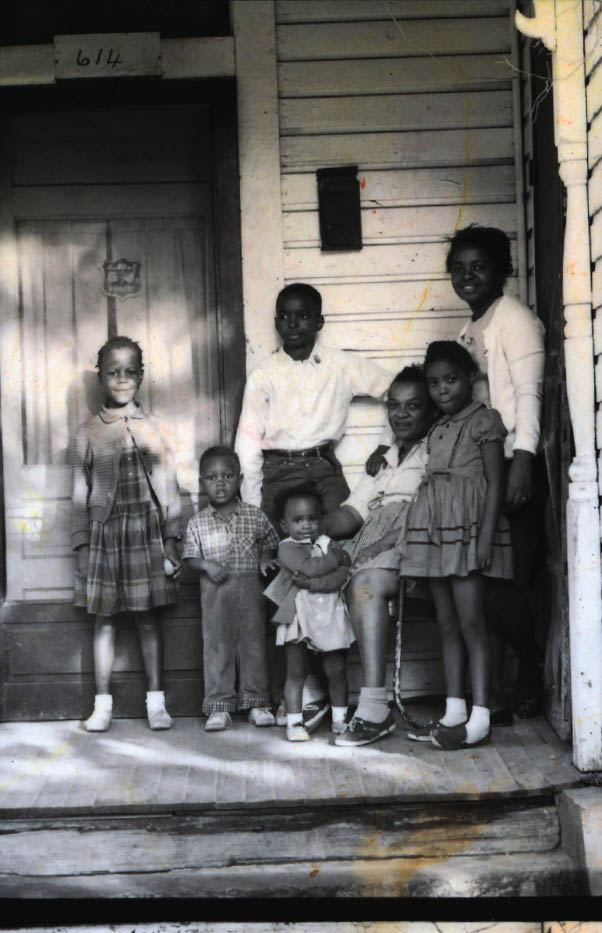

MRS. FANNIE LEE CHANEY and her family outside their house.

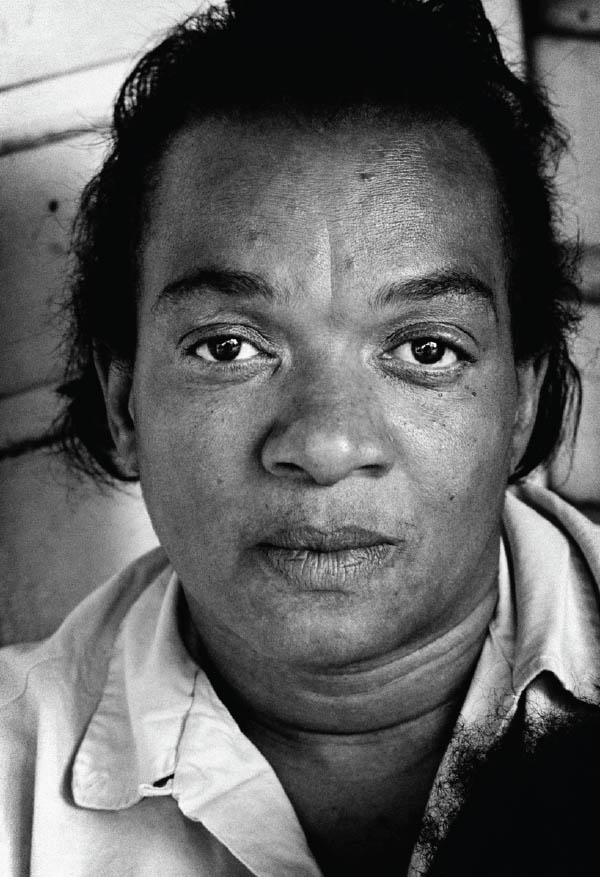

MRS. FANNIE LEE CHANEY outside her house, hearing of the death of her son, James Chaney, Mississippi, “Mississippi Eyewitness,” Ramparts magazine, 1964

Selection from a proof sheet: JOAN BAEZ and FREEDOM SINGERS participating in the trial run for the March on Washington through the town of Newport, Rhode Island, Newport Folk Festival, July 1963

The photos taken earlier that day, of Mrs. Chaney with her toddler daughter in her lap, of the Chaney children arranged on the front porch, ended up illustrating a special issue of Ramparts magazine called “Mississippi Eyewitness,” which infuriated segregationist Southerners who heard about it. They thought the articles and Jim’s pictures were purposefully smearing a way of life that had worked perfectly well (for them) before outside agitators came along and spoiled everything. But Jim wasn’t telling lies about Mississippi; his photographs were exposing an ugly truth about the Delta’s black residents’ separate and definitely unequal lives to the outside world.

Jim took these photographs before he became known as the chronicler of rock royalty. The quiet dignity of the Mississippi Delta residents stands in stark contrast to his later photos of the Summer of Love, when thousands descended upon a woefully unprepared San Francisco to tune in, turn on, and drop out. The Mississippi photos came before Jim Morrison strutted across the stage. Before Janis Joplin made crowds fall in love with her raspy, revivalist voice and her leave-it-all-on-the-stage energy. Before tens of thousands took the world’s largest communal mud bath at Woodstock. Before the Beatles made San Francisco’s Candlestick Park reverberate with joy and grief at their last concert.

Jim would probably say that these pictures from 1963 and 1964, of people great and small who tried to rearrange the country’s architecture of injustice to form a more perfect union, are just as important. And woe to the person who can’t or doesn’t get that. Jim might be dead—but friend, do not underestimate his reach.

Woman clutching her pearls in reaction to JFK’s assassination, New York City, November 22, 1963

Men’s reactions to JFK’s assassination, New York City, November 22, 1963

“PRESIDENT SHOT DEAD,” New York City, November 22, 1963

Selection from a proof sheet: Man praying in doorway in reaction to JFK’s assassination, New York City, November 22, 1963

Selections from proof sheets: BAYARD RUSTIN (this page) and JAMES FORMAN (opposite) speaking at the CORE and SNCC Freedom Vote trial run, Newport Folk Festival, Rhode Island, 1963

Selection from a proof sheet: Headstone for Ida E. Proctor, Mississippi, “Mississippi Eyewitness,” Ramparts magazine, 1964

Selection from a proof sheet: Women during voter registration training, CORE and SNCC Freedom Vote trial run, Mississippi, 1963

Selection from a proof sheet: Proud father with children during the CORE and SNCC Freedom Vote trial run, Mississippi, 1963

Mississippi, 1964

Selection from a proof sheet: Little girl and her sister sleeping on a cot at the CORE and SNCC Freedom Vote trial run, Mississippi, 1963

Mississippi, 1964

“Colored” laundry, Mississippi, “Mississippi Eyewitness,” Ramparts magazine, 1964