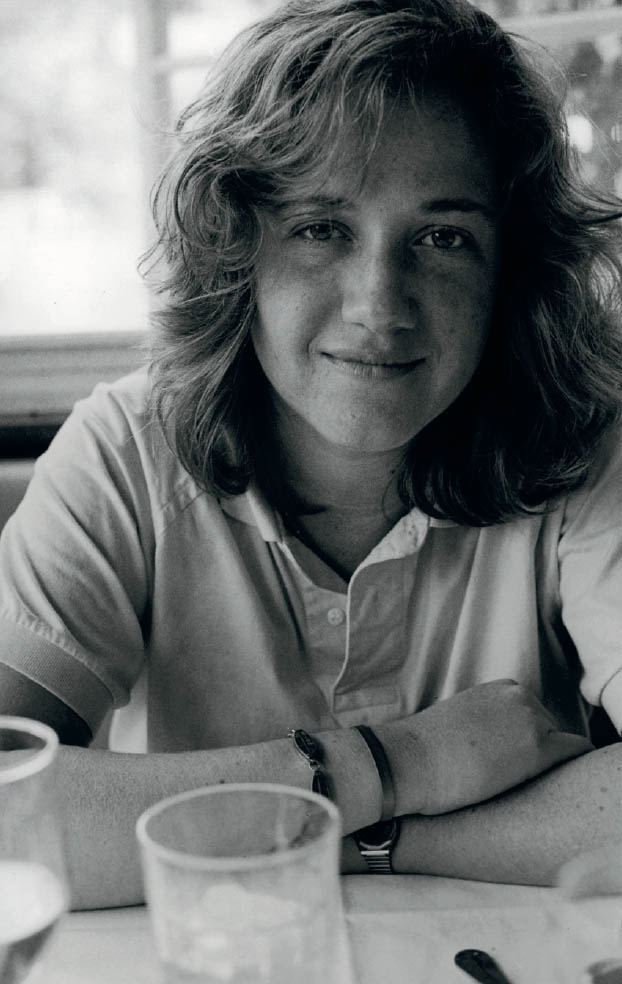

MICHELLE MARGETTS

MICHELLE MARGETTS by Jim Marshall, San Francisco, 1984

For us there will always be time—now & from before & for always—I really did love you—from before you were born—we shall always be the kid & the old man—just a note to tell you once again how much I love you.

—James

I MET JIM MARSHALL IN MARCH OF 1984. I was a journalism student at San Francisco State in need of a last-minute subject for a course assignment, a “Whatever Happened to . . .” profile. I was twenty and basically clueless about a lot of things. Like, who the hell was Jim Marshall?

Another student who knew of Jim’s work and his “dark side” suggested him as a subject after my first interviewee fell through.

He ran down a list of Jim’s highlights and lowlights: sorta famous; more importantly, infamous; into guns and coke and booze. The litany continued—Jim was maybe a genius and the best music photographer who ever lived, having photographed Woodstock, Jimi Hendrix, Miles Davis, Janis Joplin, Bob Dylan, the Beatles’ last concert, six hundred album covers, etc. He had just got out of jail for a gun beef with some neighbors in his Union Street apartment building (incorrect: he had just been released from a work furlough program); he was on probation and perhaps homeless, banned from ever stepping foot in his Union Street digs (incorrect: he never was on probation and was now living in a great apartment on 16th Street); and he was a paranoid, impulsive asshole (very correct).

Even if I could find this Jim Marshall, I was skeptical about whether he would agree to speak to me, a lowly journalism student. But I was intrigued as hell.

I began a fruitless search for him with the probation department and parole officers. Out of desperation, I called 411—I mean, what paranoid felons are listed in the phone book? Two minutes and one forwarded number later, the phone picked up on the second ring and a forceful rasp I would come to know and love—and sometimes dread—said, “YEAH lo!”

Shocked to learn that it was, in fact, the correct Jim Marshall, I stammered out the gist of my call. Jim barked out rapid-fire: “Haven’t you heard of the White Pages? Of course I’m listed, why wouldn’t I be! You call yourself a journalist! Not so fast. How old are you? Sure, I’ll meet you, but what do you look like? Cadillac Bar. Downtown. Three p.m. Don’t be fuckin’ late!!”

He brought a beat-up Kodak Ektacolor eleven-by-fourteen-inch photo paper box full of black-and-white proof sheets to our first meeting. “I’m thinking about making a poster,” he said, “as my comeback: Jim Marshall Shoots People, with all these killer shots.” He had it figured out, how you can get ten images across it and fourteen down. He’d designed it all in his head, before he’d even shown it to an art director.

Jim had been out of work furlough for five weeks, and he literally couldn’t make rent. He claimed he knew the precise number of ignition turns he had left on his ancient Ford Ranchero—it was ninety-three.

I didn’t have the guts to tell him I’d never heard of him. He scooted his chair closer and ordered us green margaritas (for St. Patrick’s Day). He kept picking at his cuticles when he wasn’t trying to hold my hand. I slowly flipped through the proof sheets, with hero shot after hero shot circled in yellow and red grease pencil. I could not resolve the strange, horny little man with the Leica over his shoulder and the hundreds of transcendent portraits I was seeing. And I could see, deep in that all-appraising gaze Jim was famous for, that this was big trouble. The very definition of “conflict of interest.” Journalism 101, but Jim didn’t care. He was in love.

And he was determined to pull out all the stops, including walking me to my car, even though it was parked right outside the bar and it was still broad daylight. I was getting tense, thinking this old fuck was going to try to kiss me, and I’d have to knee him in the ’nads. But as I turned around to thank him again and ask about the timing of a follow-up interview (now that I seemed to have passed the audition), he leaned up at me and very gently caressed my cheek with the back of his left hand. He said he looked forward to our interview on Saturday and walked away. Later, he crowed to anyone who would listen that the “hand thing” was a move he’d seen James Dean do to Julie Harris in one of his favorite movies, East of Eden.

I wrote the profile and tried (unsuccessfully) to keep Jim, and his hands, at arm’s length. My professor asked for a few rewrites and gave me an “A.” The profile was slated to be the cover story of the campus quarterly I was art directing, set to run with a portfolio of Jim’s greatest hits.

We figured out which photos to use and what was going to be the cover. The deadline was getting close, and then Jim pulled the Jim card. He tried to use the photos to manipulate me, threatening to pull them if I didn’t tell my family that he and I were in love. He kept saying, “I don’t want to be with you in the shadows.”

They say sunlight is the best disinfectant. I came to my senses and pulled the story. I went to my editor and John Burks, my advisor and publisher of the campus magazine. I said, “I need to confess something, I’m having a relationship with this guy, and we’re not running this article.” What I learned, and of course, every journalist needs to learn is, you can’t really cross that barrier. You are going to be a lover writing about the person you are sleeping with, or you are going to be objective, however you define that, and view this person with all their warts. You cannot have it both ways; it’s impossible. To this day, that article has never been published.

INSTEAD, I CALLED JIM’S BLUFF and went for the relationship. The thing that always made me love Jim, no matter how much I wanted to kill him, was that he was the first person to convince me I could go to New York and make it there. Even though he was asking me to marry him every third day, he really wanted me to go to New York. The best part of him wanted me to find out who I was supposed to be. And deep down, he knew it wasn’t Mrs. Jim Marshall.

Since we were such an odd couple, Jim delighted in finding things we had in common: We both hated onions, loved Levi’s 501s, and swore by Colgate toothpaste. We liked Grey Flannel cologne, Brooks Brothers button-downs, Bass or Cole Haan penny loafers, and Basic soap. A coffee purist, Jim loved to grind Celebes Kalossi blended with French Roast coffee beans for us in the morning—he used a classic pour-over glass Chemex carafe. I still have a Braun coffee grinder he gave me.

JIM MARSHALL by Michelle Margetts, 1984

MICHELLE MARGETTS by Jim Marshall, 1984

The twenty-eight-year age difference was more curse than blessing, and our basic temperaments were far too combustible to make it as a couple. What I really wanted was for Jim to take everything that was good and wise in his brain—all that he knew about life, love, the world, the arts, photography, editing, and writing—and just shove it into mine. And he did his best to oblige.

He gave me Maxwell Perkins’s biography. He had me read Let Us Now Praise Famous Men. He told me about W. Eugene Smith, James Agee, Walker Evans, Dorothea Lange, Roy DeCarava, Jill Freedman, and Magnum Photo Agency. He gave me The Family of Man, Jerry Stoll’s I Am a Lover, and poetry from the 1960s, and he held forth on William Blake and Lawrence Ferlinghetti.

As a former race driver, Jim taught me some tricks to navigate the mean streets of San Francisco: how to never end up idling on a steep hill at a light with a stick shift; how to go into a curve low and come out high; how to watch the left front tire of the car to your right to anticipate when it might merge; and mostly how to look far down the road, as far as you could, so that nothing surprised you.

Jim wasn’t a mechanic, but he was mechanically minded, and he feared all things digital. He loved cars, guns, and cameras, as everybody knows. But what he loved was elegant (i.e., simple) design, reliability, and explicability. He could always explain to me, if I asked, what was going on with his truck, or what was going on with his camera. He could put a new roll of film in his camera one-handed and faster than anyone I ever saw. He was a gearhead.

I have a mostly blue-collar background. I grew up as a plumber’s daughter, with carpenters, mechanics, warehousemen, and steelworkers. And that helped me really understand and appreciate Jim, whereas a lot of people—including himself—judged him for not being from the posh side of the hill.

Jim was very class conscious. When some Marin frat boy with a pink button-down came around in a tricked-out Mercedes, Jim could be a fanboy, using the commonality of the car to connect, but it was nearly obsequious. I’d ask him, “Why are you being so over-the-top ass-kissy to that guy?” And he would grimace and give me the side eye, pretending he didn’t know what I was talking about. But he also knew these guys were potential collectors of his work.

Jim made his comeback in the mid-1980s by developing a roster of regular collectors and sporadic photo shoots that kept the lights on. But he didn’t feel he deserved any of it, so he sabotaged a lot. Before the first gallery show that came together when we were a couple, he almost pulled out at the very last second because he didn’t have his own wall of work. I had to literally drag him into this gallery. He was upset, because no matter how wonderful the show might be, he knew it was never going to be enough. He had that hole in him that just seemed to be unfillable.

He talked a lot about his mom with me. She was still alive, but they were completely estranged because of the way Jim’s second wife, Rebecca, had to leave him. Rebecca was really, really close to his mom, apparently, and she had to, essentially, vanish because Jim was just a degenerate cokehead at that point. He had a lot of guns, and probably a lot of not-great people around him. The way Jim told me, Rebecca left one day for a work trip with one suitcase. She took twenty thousand dollars, left him a note in his sock drawer, and never came back. A year later she sent divorce papers. He spiraled out of control. That was two years before we met.

Jim wouldn’t talk much about his dad. He told me his father spoke fourteen languages, was an alcoholic, and was probably a spy during World War II. He told me that his dad would hit him, and that the last time he hit Jim was when they were eating dinner at their apartment in the Outer Richmond. Jim said, “He took my head, and he smashed it down on the kitchen table.” He knocked a tooth out, so Jim had a fake front tooth. Jim had hit puberty, but sometimes I wasn’t sure how much further along he’d gotten. Maybe that one smash to his head on the table froze him in place.

I don’t think Jim’s mom was integrated into American culture. I never met her, but I don’t think her language skills and English were tremendous. She worked in a laundry; she had a few different jobs. He was mortified at her lack of sophistication, and this insecurity propelled him toward that preppy thing.

I DEFINITELY KNEW THAT I WANTED JIM in my life, but I didn’t want all the rest of my life to be vaporized. It put a big rift in my family for a couple of years. It was only about two years that he and I were together, and we were probably off more than we were on. He wouldn’t really let me break up with him, and he was relentless. I said, “Don’t call me.” He asked if he could write, and then the five-by-seven-inch yellow legal pads covered in his telltale handwriting started to show up at my dorm mailbox. And flowers. It was a heady experience to be in Jim’s emotional crosshairs.

I also continued to want to have the experiences Jim offered and meet the people Jim knew. I got to go backstage at Santana concerts; I met Mimi Fariña, Joan Baez, and Mary Travers of Peter, Paul, and Mary. There are hundreds, maybe thousands, of stories and people that I wouldn’t have in my life without him. And even in that down, dark time, it was really exciting to be around him. And frustrating. The worst thing I ever wrote to Jim, after I had been in New York for a few months and he was being a real dick, was this: “You are a rock and roll suicide that never died.”

Jim was very conflicted when I met him about how the music business had evolved. I didn’t fully understand what it took to document Woodstock the way he did. It would bounce off my forehead a lot, how deeply wounded Jim was to be lumped in with all the paparazzi. And he would go absolutely psychotic if he was asked to stand in a pit, “like cattle,” with a bunch of other photographers for only three songs and then herded out of the venue. We went to a TV talk-show taping with the famous paparazzo Ron Galella, who stalked Jackie O. I thought Jim was going to try to strangle him, but he just asked Galella a really pointed question, his voice shaking with rage, about trust and how Galella could live with himself when he had betrayed so many people. Galella didn’t have much of an answer.

Jim couldn’t hear very well at that point. He was mostly deaf in one ear, and his memory was getting shaky. He always had a black Sharpie with him, and one of those five-by-seven-inch yellow legal pads, which he kept in a beautiful leather holder with a “Gort” sticker on it (from his favorite movie, The Day the Earth Stood Still). He would write down everything he had to do for the day: Take in the laundry, buy dental swords, prep for Joan Baez shoot, and threaten that guy who owes him money. He could be extremely methodical and obsessively thorough.

I have boxes of these little yellow legal pads, many of which he wrote during our “dark times.” But many he mailed to me in the years after I went to New York in June of 1985. Here is text Jim scratched out on some pages, outlining a seminar he hoped to give one day:

I think that sometimes photography in schools is too formulaic and far removed from the reality of day-to-day working photographers. I feel all of this work happens in concert with the open exchange of ideas and philosophies, and we all should be proud of it, and all try to elevate standards of our profession or our vocation.

What I would like to do in a one-day seminar is to show my work from various aspects of my career, discuss the photographs, and look at the portfolios of the people attending. To discuss ethics and values, personal trust, not the business but how one can apply all their skills to the commercial world. Not to compromise when people allow you into their lives with a camera.

To try to explain the difference between a fine photograph, perhaps taken at a tense or very private moment, and perhaps when to back off and not photograph. It is a difficult decision. I feel an open discussion of this could be very rewarding, and perhaps change some people’s way of photographing without intention. It is a fine line.

This will not be a technical class, yet I shall not hesitate to berate sloppy craftsmanship. We do what we do. I would like to keep a loose structure to the day and be open to any and all constructive ideas. In photojournalism, to become 99% involved, yet leave 1% detached so one can function, 1% can work the mechanical thing called the camera. To not let this machine come between your vision and feelings and what ends up on film.

AS I BECAME A WEB PRODUCER, I learned more and more about databases and digital design, the way links connect, and the way tangents and conflicts can lead to intrigue and action. And I realized that this was the way Jim’s brain worked, too. He linked everything naturally and dove right in. He could go up to strangers, introduce himself, and ask the most blatant stuff: “Are you Jewish? Where are you from? You have a big nose for a Protestant. Oh, buy this Jew a drink.” And ten minutes later “this Jew” is buying seventeen signed prints from him, and isn’t Jewish, by the way. I saw him do this countless times in his apartment, in my loft, in living rooms, in the best restaurants and bars in San Francisco and New York. Anywhere the world found him or he found it.

It’s been more than thirty years since our first meeting and the first crucial lessons I learned from Jim. But there were many, many more dispensed over the years. Listen to your instincts. Be true to yourself. Don’t bullshit. Keep it simple. Know your equipment. Respect your subject’s trust. Get closer! Protect your work. No. Matter. What.

I would say that I miss Jim, but I can’t. He’s in my heart and head. His framed work covers our walls: the first iconic John Coltrane portrait, the only image of Janis Joplin and Grace Slick together, the only photo of Thelonious Monk with his family, a rare partial frame of Jimi Hendrix singing in Golden Gate Park, so in focus that you see a tiny strand of spit attached to his mic. They are all such intimate moments that could have been mere snapshots, or out of focus, or sappy images you’ve seen a hundred times, and yet in Jim Marshall’s ravaged hands these pictures have become the enduring truth.

MIRIAM MAKEBA, night club in New York, 1960. Born in South Africa and known as “Mama Africa,” Makeba popularized African music in the United States and globally. She campaigned against apartheid feverishly, for which her citizenship and right to return to her home were revoked. She returned in 1990, after Nelson Mandela’s release from prison.