I WAS PLAGUED BY TERRIBLE NIGHTMARES. I was being chased through a vast crowd of people who were moving around in a purposeless, random way – terrifying. Everywhere around me trees and houses had been levelled and there were rotting corpses. Delaney was there. He was in a white tuxedo, baring his teeth: white, perfect teeth. MacDonald and Mickey Gleason, my old International Brigade chums, were there, dressed as guards, cracking their knuckles, and the varsity boys from Marlborough Street Magistrates’ Court, caked in blood. The little girl was there too, Lucy, taking photographs. And then I became lost in a dark tunnel, running along the tracks, and suddenly a train was coming towards me, lights glaring, horn blowing. ‘Life is very like a train journey,’ writes Morley in Ringing Grooves of Change, using a metaphor that will perhaps be lost on the younger generations and those without memories of steam. ‘One sometimes enters long dark tunnels and the only thing to do is to shut up the window and wait for things to clear again.’

I was horribly hung over and the room was full of the sour smell of whiskey and cigarettes. I knew a man once, a Brigader, who decided to drink himself to death: people said it took him almost a week. I began to wonder whether I should try to find the time. I thought I might spend the day in bed and then make myself scarce. But when I opened my door to go and use the bathroom at the end of the corridor I found that Morley had left a pile of clothes for me outside the room, with a note that read simply: ‘Nil desperandum! Took the liberty to kit you out afresh. Breakfast promptly. Estimated time of departure 9 a.m.’ I almost smiled. As so often, Morley was ahead of me. He had read my mood, or rather – more likely – he was proceeding simply and strictly by logic. He had worked out that the prospect of departure, any kind of departure, was going to be appealing to me. And also that I was going to need some new clothes, since my own had been ruined during the crash. Thinking ahead, he had successfully called my bluff, pulled me up short, taken me by the scruff of the neck, and set me back down again on the straight and narrow.

‘Ah, Sefton,’ he said, when I eventually presented myself at breakfast. ‘All ready for departure? You’re looking very smart.’

‘Off to do a spot of grouse shooting, are we?’ said Miriam, stubbing out a cigarette in a saucer.

‘I do wish you wouldn’t, Miriam,’ said Morley. ‘It’s a filthy habit.’

‘Oh shush, Father. Has the season begun, Sefton? I do hope you’ll allow me to join you – I love a weekend hunting party.’

The clothes were indeed of a kind that might have suited a country gent or a laird on his estate in Scotland – a particularly jolly laird with a taste for the more extravagant sort of hunting wear, for these were no rough tweeds and flannels. I was outfitted in plus-fours, enormous fat yellow socks, unyielding sunshine-orange brogues and a jacket that flared at the waist in a fashion that suggested the wearer might at any moment perform a pas de deux.

‘Where on earth did you get those ridiculous fancy dress clothes, Father?’

‘The night porter’s brother works at a rather fine gentleman’s outfitters in town. I’m afraid that at short notice this was the closest thing I could find to proper hiking gear.’

‘We’re not going hiking?’ I said.

Miriam certainly didn’t look as though she were going hiking. She was dressed, as always, with her usual verve – one might indeed say panache, if it weren’t so early in the morning – in an outfit whose abundance of black ruffles and ruches suggested that even walking might prove a problem. Her make-up was perfect and her hair precisely and elaborately smoothed around her magnificent head, giving her the look of a very fine lacquerware painting. Morley of course was dressed in his customary outfit: bow tie, suit and brogues, ‘suitable for any occasion’, he would often claim, which indeed I can confirm, having seen him fell trees and chop logs, address meetings, read scripts on the BBC, go fishing, climb mountains, and entertain bishops, duchesses and lords, all in the self-same gear. ‘Ladies and gentlemen might be able to afford the privilege of dressing appropriately,’ he liked to say. ‘The rest of us must make do with the merely practical.’

‘I don’t think I’m up to hiking,’ I said.

‘No, no,’ said Morley. ‘No time for hiking. I have taken into account your and Miriam’s concerns about us proceeding with the book as planned – and we shall indeed be pausing in our enterprise—’

‘Out of respect,’ said Miriam.

‘And also out of necessity,’ said Morley. ‘I feel the police might require our assistance.’

Miriam looked at me and raised her eyebrows. After last night’s performance I think we both rather doubted whether Morley’s assistance would be welcome.

‘They’re very keen to talk to you this afternoon, Sefton,’ continued Morley. ‘So I said I’d have you back after lunch.’

‘I’m not sure,’ I said.

‘Not sure about what?’ asked Miriam, extravagantly rearranging herself at the table, causing something of a commotion. She was the sort of woman who couldn’t move without attracting attention.

‘Not sure that I can help them with very much,’ I said.

‘I think you’ll find you don’t have much choice in the matter, Sefton,’ said Morley. ‘Eye-witness and what have you. And anyway we have a pre-existing arrangement this morning to visit an archaeological dig near Shap – part of our original itinerary – and Miriam and I both agree that we should probably fulfil that obligation.’

‘It would be terribly bad manners to cancel at such short notice, Sefton,’ said Miriam. ‘Don’t you think?’

‘Bad manners?’

‘Anyway,’ said Morley. ‘The main thing is we’re off again!’

‘That’s the departure?’ I said. ‘That’s where we’re going? To an archaeological dig at a place called Shap?’

‘That’s right,’ said Morley. ‘Not far. And then we’ll have you back this afternoon for your little chat with the police. I hope that suits?’

‘Do I have a choice?’ I said, feeling rather cheated.

‘There’s always a choice,’ said Miriam. ‘You could always stay here.’

I looked around at the glacial breakfast room of the Tufton Arms – full to capacity with guests, police and survivors of the crash, picking over their cold damp toast and their tepid tea and eggs – and shivered.

‘I suppose I’ll come, then.’

‘Excellent!’ said Morley, clapping his hands. ‘Excellent!’

‘It’ll do you good,’ said Miriam, patting my arm.

![]()

And so, after a hurried breakfast of coffee and cigarettes, and all done up in my ludicrous hunting outfit, I joined my companions in the Lagonda.

Miriam, as always, was driving, and I was stuck in the back with Morley, who was doing his best to educate me in the local lore and legends of Westmorland, from tales of dobbies and hobthrusts and other little people, to ruminations on the etymology of Old Norse place names, to the nature of the allurements of Ambleside, ‘the hub of Wordsworth’s wheel of Lakeland beauty’.

‘And home to Harriet Martineau,’ added Miriam. ‘We mustn’t forget Harriet.’

‘Dear Harriet,’ said Morley absentmindedly, proceeding to praise the fascinations of Kendal, ‘the cloistered auld grey town’ and ‘possessor of perhaps the country’s most pleasingly punning motto, pannus mihi panus’, the majesty of Patterdale, ‘home to the mighty Helvellyn’, and the ‘soothing calm’ of Windermere and Witherslack.

I did my best to stay awake.

‘Can you name how many lakes there are in the so-called Lake District, Sefton?’

‘Erm. No idea. Sorry, Mr Morley.’

‘Guess.’

‘Ten?’

‘No.’

‘Twenty?’

‘No.’

‘Thirty?’

‘Wrong, wrong, and wrong again. There is in fact only one lake in the Lake District.’

‘Really?’

‘Correct. Bassenthwaite. The rest are properly tarns, waters or meres.’

‘Ah.’

‘That’ll go in the book, of course.’

‘Jolly good,’ I said.

‘Make a note,’ said Morley, thrusting some notecards at me. ‘We don’t want to waste a minute, eh? Do you have a pencil?’

He handed me a pencil – his favourite, a Ticonderoga No.2, imported specially from America – sharp and ready to go.

‘We should probably be using a Lakeland, of course,’ he said. ‘Or a Derwent. Excellent pencils. If we get up into Cumberland we really must visit Keswick. Home of the English pencil – did you know?’

‘Yes, Mr Morley,’ I said. I had no idea that Keswick was the home of the English pencil and was less than interested, but was rather hoping that by pretending to knowledge I might avoid any kind of lecture – but no luck. With Morley, there was always a lecture.

‘Cumberland plumbago,’ he said. ‘Absolutely unbeatable. And the availability of cheap timber, of course. The extraordinary history of pencil production in this part of the world is surely something that should be more widely celebrated. Don’t you think?’

‘Indeed.’

‘One might perhaps consider constructing a shrine to the pencil, on the shores of Derwentwater.’

‘One might,’ I agreed.

‘A pencilarium!’

‘Uh-huh.’

‘There’s no such thing,’ said Miriam.

‘A Museum of Pencils then!’ cried Morley. ‘A temple to human ingenuity and humble engineering.’

‘I don’t think so, Father,’ said Miriam. ‘Who on earth would visit a museum of pencils?’

‘I would,’ said Morley. ‘A room devoted solely to the Koh-i-nor. And the Everlast mechanical pencil. Perhaps a working exhibition—’

‘Anyway!’ cried Miriam. ‘Let’s assemble, Father, not disperse’ – this being one of the phrases Miriam liked to use to refocus Morley’s attention. (Other phrases included ‘Interventions, not interjections’, ‘March, don’t waltz’ and ‘Reality, not illusions’.)

‘Yes,’ said Morley. ‘Quite right. Assemble, not disperse. Where were we, Sefton?’

‘I’m not sure, Mr Morley.’

‘Ah, yes! You were making a list. The tarns, waters and meres in Westmorland and Cumbria.’

‘That’s right.’

‘They are?’

‘Erm …’

‘In order of size?’

‘Erm …’

‘Descending order of size?’

‘Erm …’

‘Windermere; Ullswater; Derwentwater; Coniston Water; Haweswater; Thirlmere; Ennerdale Water; Wastwater; Crummock Water; Esthwaite Water; Buttermere; Grasmere; Loweswater; Rydal Water; Brotherswater.’

‘That’s just what I was going to say.’

‘Good,’ said Morley. ‘Do you know the entire population of the world could be stored in Lake Windermere, if you stacked them correctly?’

‘Really?’ said Miriam. ‘How fascinating.’

‘Or packed shoulder-to-shoulder on the Isle of Wight.’

‘Well, that’s good to know, Father.’

‘Isn’t it? Write it all down then, Sefton. Write it all down.’

If there is only one thing I learned from my time with Morley it was probably that: the secret of successful authorship, summed up in just four words. Write it all down. Assemble, not disperse. Interventions, not interjections. March, don’t waltz. Reality, not illusions. And always keep a pencil handy.

On our rather circuitous drive – ‘We must stop here!’ Morley would announce, every ten minutes, and ‘No, Father,’ Miriam would invariably retort, before we did often end up stopping, for no good reason other than to admire a view. ‘Aren’t we just the William Gilpins!’ Morley would exult – we passed a couple of gypsy caravans, tucked down narrow lanes away from the main road.

‘Miriam!’ cried Morley. ‘Didn’t our friend the signalman mention gypsy children on the line? I wonder if perhaps we should—’

‘No, Father!’ said Miriam. ‘Sorry! No time. We’re due at the dig.’

‘But—’

‘No ifs, no buts, no nothing. I have the wheel, in case you didn’t notice. If you want to speak to the gypsies you’ll have to do it later.’

‘Do you know the gypsiologist John Sampson?’ Morley asked me.

‘I can’t say I do, Mr Morley, no.’

‘Terribly interesting. Bit of an oddball. Founding member of the Gypsy Lore Society. Rather romantic view of things – the gypsy as a kind of ur-ancestor of mankind. Interesting notion of course, and a long line of such thinking in the literary imagination: Arnold associating gypsies with resistance to the “strange disease” of modern life. Other examples?’

‘Erm.’

‘Miriam: other examples of representations of the gypsy in English literature?’

‘Heathcliff?’ called Miriam.

‘He’ll do, I suppose,’ said Morley.

‘He’ll more than do,’ said Miriam.

‘Never seen the appeal myself,’ said Morley.

‘He’s not for you, Father.’

‘Well, who is he for? Dreadful man. Tortured romantic soul, prone to violence, troubled past. Can’t see the appeal.’

‘That’s precisely the appeal,’ said Miriam. ‘Isn’t it, Sefton?’

I forbore to answer.

‘I rather prefer Arnold’s scholar gypsy,’ said Morley.

‘You would,’ said Miriam.

‘Rather fascinating topic, though, eh?’ said Morley. ‘The English gypsy. Fascinating …’

(A complete history of Morley’s fascinations would be very long indeed. There is, I believe, a doctoral student in the United States of America, a Mr Balokowsky, who is currently compiling an index of Morley’s topics and themes, culled from the thousands of publications. It seems to me like an utterly pointless and very probably endless enterprise. I have made my views known to the young man and declined to become in any way involved. The task is simply too great, like compiling a list of everything. I doubt that there was any subject, place, person, entity, animal, vegetable or mineral that during our time together I did not hear Morley describe as ‘fascinating’. The rules of etiquette: fascinating. Electro-plating: fascinating. Falconry, fingerprinting, flower lore: fascinating. But as for the English gypsy, ‘the Romanichal’, this was more than fascinating: the Romanichal were an obsession.)

‘Maggie Tulliver’s defection to the gypsy camp,’ he continued, ‘and Jane Austen’s Harriet Smith accosted by begging gypsy children on the outskirts of Highbury in Emma. The gypsy perhaps as the Englishman’s surrogate self’ – and certainly as Morley’s surrogate self. He was in many ways a romantic wanderer, strange and set apart, just like the scholar gypsy in Arnold’s poem. ‘O like unlike to ours! / Who fluctuate idly without term or scope, / Of whom each strives, nor knows for what he strives, / And each half lives a hundred different lives; / Who wait like thee, but not, like thee, in hope.’

Anyway, Miriam, I am delighted to say, accelerated quickly past the gypsy caravans.

‘Miriam!’ cried Morley. ‘Couldn’t we stop just for a moment?’

‘No time!’ cried Miriam. ‘Fugit irreparabile tempus.’

‘But they look like very fine wagons! You can’t beat a gypsy vardo. I remember I was in the Carpathians once—’

‘It’s not happening, Father.’

‘Have you ever been inside a gypsy vardo, Sefton?’ asked Morley.

‘I can’t say I have, Mr Morley, no.’

‘And he’s not going to be today, Father,’ said Miriam. ‘Come on. No slacking, no shilly-shallying. No funking.’

‘Very well,’ said Morley. ‘Very well.’

He returned to his typing, while Miriam let out a triumphant laugh, tossed back her head with typical dash, and floored the accelerator. I, as always, felt rather sick and wondered what on earth I was doing with these lunatics.

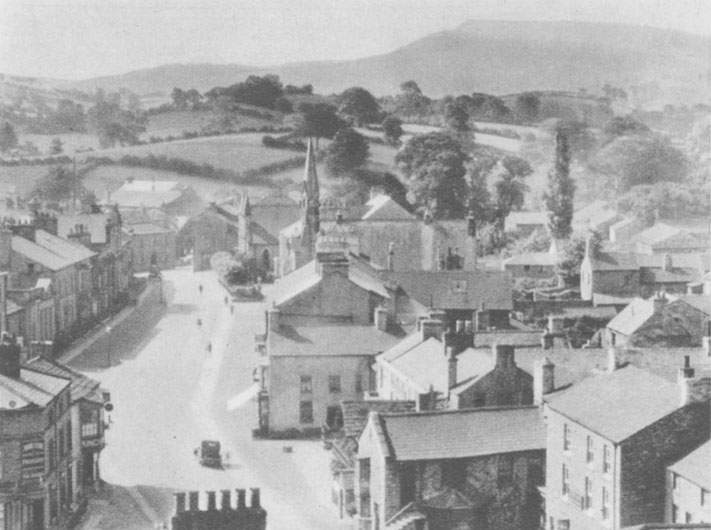

My leg, which had been expertly dressed by the nurse the day before, was now throbbing rather. And my head: the bump from the luggage rack had swollen into a lump the size and colour of one half of a bad potato. I did perhaps mention my pains once or twice, and perhaps more than once or twice, and certainly so much that as we were driving through Kirkby Stephen – ‘Just a little detour?’ Morley had petitioned Miriam. ‘To see the parish church, the Cathedral of the Dales?’ – Miriam pulled over the Lagonda and we parked outside a pharmacy in the centre of the town.

‘Come on, you big baby,’ she said, getting out and slamming the door.

‘What?’

‘Let’s get you something for those bangs and bruises.’

Morley was about to leap out of the car and follow.

‘We’re not stopping here, Father,’ said Miriam, pushing him back in.

‘Well, we are, actually,’ said Morley. ‘Strictly speaking, we have stopped. We are no longer—’

‘I mean we’re not stopping here for long,’ said Miriam. ‘We’ll only be a minute. You just stay in the car.’

‘Fine!’ said Morley, who was already hammering away at his typewriter again, his attention having been caught by some pillared shelter. ‘Hmm. What do you think, early nineteenth century, Sefton?’

‘Back in a moment, Father! Come on, Sefton. Chop, chop.’

Taylor’s Pharmacy – ‘ALL PATENT MEDICINES AND PROPRIETARY ARTICLES KEPT IN STOCK’ – was a jigsaw-puzzle neat storehouse of brown and white bottles and pots in glass cabinets, decorated with gilt and mirrors and dark mahogany drawers. Mr Taylor, the pharmacist – for it was he – stood in his pharmacist’s white coat, perfectly framed before this vast pharmacopoeia and behind a tiny set of shiny brass scales, like a god preparing to weigh mercy and justice, sub specie aeternitatis. He was younger than one might have expected for a pharmacist and might perhaps generously have been described as ‘robust’, sturdy around the chest and waist, though with a generous, soft clerical sort of face. He looked indeed like the perfect pharmacist: one could imagine him both dispensing and refusing to dispense you with absolutely anything. The drawers and bottles and cabinets behind him suggested a world of wonders and he the guardian to another realm. The whole atmosphere of the place, I have to say, made me rather excited. I felt like a cook, or a gourmand, surveying a well-stocked kitchen, come to petition the larder keeper.

Miriam explained that we were just passing through and were on our way to Shap, and that we required a little something for bumps, bruises and a headache.

‘You’re not locals then?’ said Mr Taylor, gathering whatever it was he saw fit to dispense.

‘No, sir, from Norfolk. We’re here on a trip.’

‘You heard about the crash yesterday, at Appleby?’

‘Not only did we hear about the crash,’ said Miriam. ‘I’m afraid my companion here sustained his injuries in the course of it.’

‘You’re not the fellow from London who everyone’s talking about?’

‘Almost certainly!’ said Miriam.

‘The chap who saved the family from the burning carriage?’

‘The man himself.’

I winced.

‘Well done, sir,’ said Mr Taylor. ‘Congratulations.’

I had nothing to be congratulated on.

‘I’m sure you must have been busy here yesterday with the crash?’ asked Miriam.

‘We sent over some supplies, yes,’ said Mr Taylor. ‘Terrible business.’

‘Yes,’ agreed Miriam.

‘There was a little girl who died, from London, is that right?’

Miriam, kindly, did not answer, and Mr Taylor carried on with his tasks.

‘They don’t know yet what caused it then?’ he asked.

‘Not as far as I’m aware,’ said Miriam.

At which point a bell rang in the shop, announcing another customer – and Morley wandered in.

‘Father!’ said Miriam. ‘I told you to wait in the car!’

‘I know, my dear. I know, I know. I just thought you were taking so long that there might be some sort of problem.’

‘There’s no problem, Father. Everything’s in hand, thank you. You can go and wait in the car. Otherwise we’ll fall behind schedule. Far far behind schedule. You know how far behind schedule we are already.’ She looked at me imploringly.

‘Mr Morley,’ I said. ‘We really must hurry along. This is not a part of the itinerary.’

‘Oh, but I do love a pharmacy,’ said Morley, beginning to fossick around, running a hand along a super-shiny wooden counter. ‘I’m always reminded of Blake in a pharmacy, aren’t you, Sefton? “If the doors of perception were cleansed every thing would appear to man as it is, Infinite. For man has closed himself up, till he sees all things thro’ narrow chinks of his cavern.” You have the keys to unlock the doors of perception, sir,’ he said to Mr Taylor, who was concentrating on weighing and packing our prescription.

‘Don’t mind my father,’ said Miriam. ‘We’ll be gone in a moment.’

‘You certainly keep this place spick and span,’ said Morley.

‘I do my best, sir.’

‘And are we to assume that you are the Mr Taylor of Taylor’s Pharmacy?’

‘That I am, sir. Gerald Taylor. Third generation of Taylors to be running this shop. Pleased to make your acquaintance.’

‘Likewise,’ said Morley. ‘Likewise.’ He was staring up at the many awards and certificates that were framed, high up on the walls.

‘You appear to be supremely well qualified, Mr Taylor,’ said Morley, gesturing towards the certificates. ‘Inspires confidence, eh?’

‘Them?’ said Mr Taylor. ‘Oh, no, they’re not for the pharmacy. They’re for the wrestling.’

‘The wrestling?’

‘Westmorland wrestling. Bit of a hobby. Goes back generations in our family. You’ve mebbe not heard of it, sir? It’s local.’

‘Westmorland wrestling!’ cried Morley, becoming dangerously but predictably excited. ‘Westmorland wrestling! Not only have I heard of it, Mr Taylor!’ he exclaimed, standing up tall on tiptoes in his brogues. ‘I am a great fan of wrestling of all kinds.’ (This I can confirm. He was also an enthusiastic practitioner.)

‘Father,’ said Miriam. ‘It’s probably time we went. Mr Taylor, if I could pay you perhaps, for the—’

‘Greco-Roman. Freestyle. Lancashire wrestling. Do you know William Litt’s Wrestliana, perhaps, Mr Taylor, in which he claims that wrestling is of divine origin? Wonderful book. Jacob wrestling with the angel at the River Jabbok?’

‘I can’t say I do, sir. I just likes the wrestling.’

‘You know, the most extraordinary bout I think I’ve ever seen was when I was in Turkey once,’ said Morley, warming to another theme. (Note, Mr Balokowsky – another theme. There is no shortage. There can be no definitive list.) ‘They have this most peculiar sport of oil wrestling. Have you come across it at all at all at all?’

‘I can’t say I have, sir, no.’

‘The competitors oil themselves up until they’re positively glistening – almost like they’ve been dipped in honey—’

‘Mmm,’ said Miriam involuntarily.

‘And then the aim is not to throw the opponent but rather to hold on to them.’

‘More like pig wrasslin,’ said Mr Taylor.

‘Precisely like pig wrestling,’ said Morley. ‘Rather spectacular, actually. Reminds one of Marcus Aurelius.’

‘Father!’ said Miriam. ‘There’s no time to be reminded of Marcus Aurelius! We really must press on.’

‘“The art of living is more like wrestling than dancing.”’

‘Father!?’

‘But do you know I have never once seen Westmorland wrestling,’ continued Morley. ‘Never had the opportunity.’

‘Well, I’m going to be across in Egremont later, sir, at the fair. If you’re interested.’

‘Well, we really should, Miriam, shouldn’t we?’

‘You’d be very welcome, sir.’

‘Thank you, Mr Taylor. Very best of luck to you today.’

‘Thank you, sir.’

We took the medicines and left.

‘What an absolutely charming fellow,’ said Morley. ‘And he must be quite a wrestler, judging by all the awards and certificates.’

‘Mmm,’ said Miriam. ‘Big hog of a man.’

‘Break your neck quite easily, I would have thought,’ said Morley.

‘Oh, don’t be morbid, Father. Now, Shap here we come!’