BAILEY, PEARL

BAILEY, PEARL BAILEY, PEARL

BAILEY, PEARL(29 Mar. 1918–17 Aug. 1990), actress, singer, and entertainer, was born Pearl Mae Bailey in Newport News, Virginia, the daughter of the Reverend Joseph James Bailey and Ella Mae (maiden name unknown). Her brother Bill Bailey was at one time a well-known tap dancer.

While still in high school, Bailey launched her show business career in Philadelphia, where her mother had relocated the family after separating from Rev. Bailey. In 1933, at age fifteen, she won the first of three amateur talent contests, with a song-and-dance routine at the Pearl Theatre in Philadelphia, which awarded her a five dollar prize. In a second contest at the Jungle Inn in Washington, D.C., she received a twelve dollar prize for a buck-and-wing dancing act. After winning a third contest at the famed Apollo Theatre in Harlem, she began performing professionally—first as a specialty dancer or chorus girl with several small bands, including NOBLE SISSLE’s band, on the vaudeville circuits in Pennsylvania, Maryland, and Washington during the 1930s, then as a vocalist with Cootie Williams and COUNT BASIE at such smart New York clubs as La Vie en Rose and the Blue Angel, and on the World War II USO circuit, during the 1940s.

Bailey made her Broadway debut as a saloon barmaid named Butterfly in the black-authored musical St. Louis Woman, which opened at the Martin Beck Theatre, 30 March 1946, and ran for 113 performances. Although the show was only modestly successful, she was praised for her singing of two hit numbers, “Legalize My Name” and “(It’s) A Woman’s Prerogative (to Change Her Mind).” For her performance, she won a Donaldson Award as the best Broadway newcomer. After several failed marriages, one to comedian Slappy White, Bailey married the legendary white jazz drummer Louis Bellson Jr., in 1952; they adopted two children. Their marriage was reportedly a happy one. In later years, she frequently sang with her husband’s band, and at one time toured with CAB CALLOWAY and his band.

Pearl Bailey in her first starring role on Broadway, as Madame Fleur in House of Flowers (1954), with her three flowers, left to right, Tulip (Josephine Premice), Pansy (Enid Mosier), and Gladiola (Enid Moore). © Bettmann/CORBIS

After appearing in supporting roles in two predominantly white shows in 1950–1951, Bailey’s first Broadway starring vehicle was House of Flowers (1954), a Caribbean-inspired musical. Bailey played the part of Mme. Fleur, a resourceful bordello madam, whose house of prostitution in the French West Indies is facing hard times, forcing her to resort to desperate measures to save it. The show opened at the Alvin Theatre, 30 December 1954, and had a run of 165 performances. Despite what the New York Times (30 Dec. 1954) called “feeble material,” she was credited with “an amusing style” and the ability to “[throw] away songs with smart hauteur.”

Bailey’s most important Broadway role was as the irrepressible Dolly Levi (a marriage broker who arranges a lucrative marriage for herself) in the all-black version of Hello, Dolly!, which opened at the St. James Theatre in November 1967 for a long run, sharing the stage with the original 1964 Carol Channing version. The black version provided tangible evidence that roles originally created by white actors could be redefined and given new vitality from the perspective of the African American experience. Lyndon Johnson, who had used the show’s title song as his campaign theme song in 1964, changing the words to “Hello, Lyndon!,” saw the show when it came to Washington and was invited, along with his wife Lady Bird, to join Bailey onstage for a rousing finale. For her performance, Bailey won a special Tony Award in 1968.

Bailey’s most important film roles included Carmen Jones (1954), as one of Carmen’s friends; St. Louis Blues (1958), as composer W. C. HANDY’s Aunt Hagar; Porgy and Bess (1959), as Maria, the cookshop woman; All the Fine Young Cannibals (1960), as a boozing, over-the-hill blues singer; and Norman. . . Is That You? (1976), opposite comedian REDD FOXX, as estranged parents of a gay son. Her voice was also used for Big Mama, the owl, in the Disney animated film The Fox and the Hound (1981).

A frequent performer and guest on television talk shows beginning in the 1950s, Bailey also hosted her own variety series on ABC, The Pearl Bailey Show (Jan.–May 1971), for which her husband directed the orchestra while she entertained an assortment of celebrity guests. She also appeared on television in “An Evening with Pearl” (1975) and in a remake of The Member of the Wedding (1982), in the role of Berenice. Bailey released numerous albums and was also the author of several books, including two autobiographies, The Raw Pearl (1968) and Talking to Myself (1971), and Pearl’s Kitchen (1973), a cookbook.

In 1975 Bailey was appointed as a U.S. delegate to the United Nations. Other honors and awards included a citation from New York City mayor John V. Lindsay; Cue magazine entertainer of the year (1969); the First Order in Arts and Sciences from Egyptian president Anwar Sadat; the Screen Actors Guild Award for outstanding achievement in fostering the finest ideals of the acting profession; and an honorary Doctor of Humane Letters from Georgetown University (1977). She later earned a degree in theology from Georgetown.

During the later years of her life, Bailey was hospitalized several times for a heart ailment. She also suffered from an arthritic knee, which was replaced with an artificial one just prior to her death. She collapsed, apparently from a heart attack, at the Philadelphia hotel where she was staying (her home was in Havasu, Arizona); she died soon after at Thomas Jefferson University Hospital in Philadelphia.

Bailey was best known for her lazy, comical, half-singing, half-chatting style, expressive hands, tired feet, and folksy, congenial philosophy of life, which endeared her to audiences both black and white. The New York Times obituary (18 Aug. 1990) called her “a trouper in the old theatrical sense,” who had “enraptured theater and nightclub audiences for a quarter-century by the languorous sexuality of her throaty voice as well as by the directness of her personality.” At her funeral, Cab Calloway, who had starred with her in Hello, Dolly!, said that “Pearl was love, pure and simple love”; and her husband called her “a person of love,” who believed that “show business” meant to “show love.”

Bailey, Pearl. The Raw Pearl (1968).

_______. Talking to Myself (1971).

Bogle, Donald. Blacks in American Films and Television: An Illustrated Encyclopedia (1988).

_______. Brown Sugar: Eighty Years of America’s Black Female Superstars (1980).

Peterson, Bernard L., Jr. A Century of Musicals in Black and White: An Encyclopedia of Musical Stage Works by, about, or Involving African Americans (1993).

Obituaries: New York Times, 18, 24, and 25 Aug. 1990.

—BERNARD L. PETERSON

BAKER, ELLA JOSEPHINE

BAKER, ELLA JOSEPHINE(13 Dec. 1903–13 Dec. 1986), civil rights organizer, was born in Norfolk, Virginia, the daughter of Blake Baker, a waiter on the ferry between Norfolk and Washington, D.C., and Georgianna Ross. In rural North Carolina where Ella Baker grew up, she experienced a strong sense of black community. Her grandfather, who had been a slave, acquired the land in Littleton on which he had slaved. He raised fruit, vegetables, and cattle, which he shared with the community. He also served as the local Baptist minister. Baker’s mother took care of the sick and needy.

After graduating in 1927 from Shaw University in Raleigh, North Carolina, Baker moved to New York City. She had dreamed of doing graduate work in sociology at the University of Chicago, but it was 1929, and times were hard. Few jobs were open to black women except teaching, which Baker refused to do because “this was the thing that everybody figures you could do” (Cantarow and O’Malley, 62). To survive, Baker waitressed and worked in a factory. During 1929–1930 she was an editorial staff member of the American West Indian News and in 1932 became an editorial assistant for GEORGE SCHUYLER’s Negro National News, for which she also worked as office manager. In 1930 she was on the board of directors of Harlem’s Own Cooperative and worked with the Dunbar Housewives’ League on tenant and consumer rights. In 1930 she helped organize and in 1931 became the national executive director of the Young Negroes’ Cooperative League, a consumer cooperative. Baker also taught consumer education for the Works Progress Administration in the 1930s and, according to a letter written in 1936, divided her time between consumer education and working at the public library at 135th Street. She married Thomas J. Roberts in 1940 or 1941; they had no children.

Beginning in 1938 Baker worked with the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP), and from 1941 to 1946 she traveled throughout the country but especially in the South for the NAACP, first as field secretary and then as a highly successful director of branches to recruit members, raise money, and organize local campaigns. Among the issues in which she was involved were the anti-lynching campaign, the equal-pay-for-black-teachers movement, and job training for black workers. Baker’s strength was the ability to evoke in people a feeling of common need and the belief that people together can change the conditions under which they live. Her philosophy of organizing was “you start where the people are” and “strong people don’t need strong leaders.” In her years with the NAACP, Baker formed a network of people involved with civil rights throughout the South that proved invaluable in the struggles of the 1950s and 1960s. Among the more significant of her protégés was the Alabama seamstress ROSA PARKS. Baker resigned from her leadership role in the national NAACP in 1946 because she felt it was too bureaucratic. She also had agreed to take responsibility for raising her niece. Back in New York City, she worked with the NAACP on school desegregation, sat on the Commission on Integration for the New York City Board of Education, and in 1952 became president of the New York City NAACP chapter. In 1953 she resigned from the NAACP presidency to run unsuccessfully for the New York City Council on the Liberal Party ticket. To support herself, she worked as director of the Harlem Division of the New York City Committee of the American Cancer Society.

In January 1958 BAYARD RUSTIN and Stanley Levison persuaded Baker to go to Atlanta to set up the office of the Southern Christian Leadership Conference (SCLC) to organize the Crusade for Citizenship, a voter registration program in the South. Baker agreed to go for six weeks and stayed for two and a half years. She was named acting director of the SCLC and set about organizing the crusade to open simultaneously in twenty-one cities. She was concerned, however, that the SCLC board of preachers did not sufficiently support voter registration. Baker had increasing difficulty working with MARTIN LUTHER KING JR., whom she described as “too self-centered and cautious” (Weisbrot, 33). Because she thought that she would never be appointed executive director, Baker persuaded her friend the Reverend John L. Tilley to assume the post in April, and she became associate director. After King fired Tilley in January 1959, he asked Baker once again to be executive director, but his board insisted that her position must be in an acting capacity. Baker, however, functioned as executive director and signed her name accordingly. In April 1960 the executive director post of SCLC was accepted by the Reverend Wyatt Tee Walker.

After hundreds of students sat in at segregated lunch counters in early 1960, Baker persuaded the SCLC to invite them to the Southwide Youth Leadership Conference at Shaw University on Easter weekend. From this meeting the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC) was eventually formed. Although the SCLC leadership pressured Baker to influence the students to become a youth chapter of SCLC, she refused and encouraged the students to beware of SCLC’s “leader-centered orientation.” She felt that the students had a right to decide their own structure. Baker’s speech “More Than a Hamburger,” which followed King’s and James Lawson’s speeches, urged the students to broaden their social vision of discrimination to include more than integrating lunch counters. JULIAN BOND described the speech as “an eye opener” and probably the best of the three. “She didn’t say, ‘Don’t let Martin Luther King tell you what to do,’” Bond remembers, “but you got the real feeling that that’s what she meant” (Hampton and Fayer, 63). JAMES FORMAN, who became director of SNCC a few months later, said Baker felt SCLC “was depending too much on the press and on the promotion of Martin King, and was not developing enough indigenous leadership across the South” (Forman, 216).

After the Easter conference weekend, Baker resigned from the SCLC, and after having helped Walker learn his job she went to work for SNCC in August. To support herself she worked as a human relations consultant for the Young Women’s Christian Association in Atlanta. Baker continued as a mentor to SNCC civil rights workers, most notably ROBERT P. MOSES. At a rancorous SNCC meeting at Highlander Folk School in Tennessee in August 1961, Baker mediated between one faction advocating political action through voter registration and another faction advocating nonviolent direct action. She suggested that voter registration would necessitate confrontation that would involve them in direct action. Baker believed that voting was necessary but did not believe that the franchise would cure all problems. She also understood the appeal of nonviolence as a tactic, but she did not believe in it personally: “I have not seen anything in the nonviolent technique that can dissuade me from challenging somebody who wants to step on my neck. If necessary, if they hit me, I might hit them back” (Cantarow and O’Malley, 82).

After the 1964 Mississippi summer in which northern students went south to work in voter registration, SNCC decided to organize the Mississippi Freedom Democratic Party (MFDP) as an alternative to the regular Democratic Party in Mississippi. Thousands of people registered to vote in beauty parlors and barbershops, churches, or wherever a registration booth could be set up. Baker set up the Washington, D.C., office of the MFDP and delivered the keynote speech at its Jackson, Mississippi, state convention. The MFDP delegates were not seated at the Democratic National Convention in Washington, D.C., but their influence helped to elect many local black leaders in Mississippi in the following years and forced a rules change in the Democratic Party to include more women and minorities as delegates to the national convention.

From 1962 to 1967 Baker worked on the staff of the Southern Conference Education Fund (SCEF), dedicated to helping black and white people work together. During that time she organized a civil liberties conference in Washington, D.C., and worked with Carl Braden on a mock civil rights commission hearing in Chapel Hill, North Carolina. In her later years in New York City she served on the board of the Puerto Rican Solidarity Committee, founded and was president of the Fund for Education and Legal Defense, which raised money primarily for scholarships for civil rights activists to return to college, and was vice chair of the Mass Party Organizing Committee. She was also a sponsor of the National United Committee to Free ANGELA DAVIS and All Political Prisoners, a consultant to both the Executive Council and the Commission for Social and Racial Justice of the Episcopal Church, and a member of the Charter Group for a Pledge of Conscience and the Coalition of Concerned Black Americans. Until her death in New York City she continued to inspire, nurture, scold, and advise the many young people who had worked with her during her career of political activism.

Ella Baker’s ideas and careful organizing helped to shape the civil rights movement from the 1930s through the 1960s. She had the ability to listen to people and to inspire them to organize around issues that would empower their lives. At a time when there were no women in leadership in the SCLC, Baker served as its executive director. Hundreds of young people became politically active because of her respect and concern for them.

Ella Baker’s papers are in the Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture of the New York Public Library.

Cantarow, Ellen, and Susan Gushee O’Malley. Moving the Mountain (1980).

Forman, James. The Making of Black Revolutionaries (1972).

Hampton, Henry, and Steve Fayer. Voices of Freedom (1991).

Ransby, Barbara. Ella Baker and the Black Freedom Movement (2003).

Weisbrot, Robert. Freedom Bound (1990).

Obituary: New York Times, 17 Dec. 1986.

—SUSAN GUSHEE O’MALLEY

BAKER, GEORGE.

BAKER, GEORGE.See Father Divine.

BAKER, JOSEPHINE

BAKER, JOSEPHINE(3 June 1906–10 Apr. 1975), dancer, singer, and entertainer, was born in the slums of East St. Louis, Missouri, the daughter of Eddie Carson, a drummer, who abandoned Baker and her mother after the birth of a second child, and of Carrie McDonald, a one-time entertainer who supported what became a family of four by doing laundry. Poverty, dislocation, and mistreatment permeated Baker’s childhood. By the age of eight she was earning her keep and contributing to the family’s support by doing domestic labor. By the time Baker was fourteen, she had left home and its discord and drudgery; mastered such popular dances as the Mess Around and the Itch, which sprang up in the black urban centers of the day; briefly married Willie Wells and then divorced him; and begun her career in the theater. She left East St. Louis behind and traveled with the Dixie Steppers on the black vaudeville circuit, already dreaming of performing on Broadway.

Baker’s dream coincided with the creation of one of the greatest musical comedies in American theater, Shuffle Along, with music by EUBIE BLAKE and lyrics by NOBLE SISSLE. A constant crowd-pleaser with her crazy antics and frantic dancing as a comic, eye-crossing chorus girl, Baker auditioned for a role in the musical in Philadelphia in April of 1921, only to be rejected as “too young, too thin, too small, and too dark.” With characteristic determination, she bought a one-way ticket to New York, auditioned again, and was rejected again, but she secured a job as a dresser in the touring company. On the road she learned the routines, and, when a member of the chorus line fell ill, she stepped in and became an immediate sensation. More than five hundred performances later, in the fall of 1923, the Shuffle Along tour ended, and Baker was cast in Sissle and Blake’s new show, Bamville, later retitled and better known as The Chocolate Dandies. When the musical opened in New York in March of 1924, Baker not only played Topsy Anna, a comic role straight out of the racist minstrel tradition, but also appeared as an elegantly dressed “deserted female” in the show’s “Wedding Finale,” foreshadowing the poised and polished performer of world renown she would become.

In the summer of 1925 Baker’s dancing at the Plantation Club at Fiftieth Street and Broadway caught the eye of Caroline Dudley Reagan, a young socialite planning to stage a black revue in Paris in the vein of Shuffle Along or Runnin’ Wild, the revue that introduced the Charleston in 1924. The company that came to be known as La Revue Nègre was long on talent, with such now legendary figures as the composer Spencer Williams, the bandleader and pianist Claude Hopkins, and the clarinetist SIDNEY BECHET, the dancer and choreographer Louis Douglas, and the set designer Miguel Covarrubias. Baker joined the troupe as lead dancer, singer, and comic. When the performers arrived in Paris in late September 1925, opening night at the Théâtre des Champs Elysées was ten days away. During that brief time the revue was transformed from a vaudeville show, replete with the stereotypes expected by a white American public, into a music-hall spectacle filled with colonialist fantasies that appealed to the largely male, voyeuristic Parisian audience.

When La Revue Nègre opened to a packed house on 2 October 1925, it was an instantaneous succès de scandale. First, Baker stunned the rapt onlookers with her blackface comic routine, in which, seemingly part animal, part human, she shimmied, contorted her torso, writhed like a snake, and vibrated her behind with astonishing speed. Then she provoked boos and hisses as well as wild applause when, in the closing “Dance sauvage,” wearing only feathers about her hips, she entered the stage upside down in a full split on the shoulders of Joe Alex. Janet Flanner recorded the moment in the New Yorker: “Midstage, he paused, and with his long fingers holding her basket-wise around the waist, swung her in a slow cartwheel to the stage floor, where she stood like his magnificent discarded burden, in an instant of complete silence. She was an unforgettable female ebony statue.” Called the “black Venus” and likened to African sculpture in motion, Baker was seen both as a threat to “civilization” and, like le jazz hot, as a new life force capable of energizing a weary France mired down in tradition and in need of renewal.

Paris made “la Baker” a celebrity, embracing both her erotic yet comic stage persona and her embodiment of Parisian chic as she strolled the city’s boulevards beautifully dressed in Paul Poiret’s creations. Beginning in 1926 Baker starred at the oldest and most venerated of French music halls, the Folies-Bergère. Once again, she was a shocking sensation. Instead of the customary bare-breasted, light-skinned women standing in frozen poses onstage at the Folies, Baker presented the Parisian audience with a dark-skinned, athletic form clad in a snicker-producing girdle of drooping bananas, dancing the wildest, most electrifying Charleston anyone had ever witnessed. As the young African savage Fatou, she captured the sexual imagination of Paris.

In 1928, sensing that her public was beginning to tire of her frenetic antics, Baker left Paris. During an extended tour of European and South American cities with her manager and lover, Giuseppe “Pepito” Abatino, she studied voice, disciplined her dancing, and learned to speak French. However, Baker’s reception in such cities as Vienna, Budapest, Prague, and Munich was not what it had been in Paris. Protests broke out in hostile reaction to her nudity, to jazz music, and to her foreignness. Baker also encountered for the first time the racism she thought she had left behind in America, the racism against which she would campaign onstage and off for the rest of her life. By the time she made her triumphal return to Paris two and a half years later, she had transformed herself into a sophisticated, elegantly attired French star.

In the 1930s Baker’s career branched out in new directions. Singing took on new importance in her performances, and in her 1930–1931 revue at the Casino de Paris she perfected her signature song, “J’ai deux amours,” proclaiming that her two loves were her country and Paris. She began recording for Columbia Records in 1930. She starred in two films, Zou-Zou (1934) and Princesse Tam-Tam (1935), whose story lines paralleled her rags-to-riches life. In the first film she is transformed from a poor laundress to a glamorous music-hall star and in the second from a Tunisian goat girl to an exotic princess. In the fall of 1934 she successfully tackled light opera in the starring role of Offenbach’s operetta La Créole.

One year later, hoping to enjoy the success at home she had earned abroad, Baker sailed with Pepito to New York and began four months of preparation for the Ziegfeld Follies of 1936. The reviews of the New York opening in January took hateful aim at Baker’s performance. Belittling her success abroad with the explanation that in France “a Negro wench always has a head start,” the reporter remarked that “to Manhattan theatergoers last week she was just a slightly buck-toothed Negro woman whose figure might be matched in any night-club show, and whose dancing and singing might be topped practically anywhere outside of Paris.” Critics, black and white, resented her performing only French cabaret material rather than “Harlem songs.” Newspapers also reported that Baker personally was snubbed, refused entrance to hotels and nightclubs.

Reactions to this discrimination varied, with some condemning her for “trying to be white.” The columnist Roi Ottley of the Amsterdam News, on the other hand, praised her efforts to overcome Jim Crowism, saying that “she was just trying to live ignoring color.” He recommended that “Harlem. . . should rally to the side of this courageous Negro woman. We should make her insults our insults.”

Disappointed by her reception in her homeland and saddened by the death from cancer of Pepito, Baker returned to Paris and to the nude revues at the Folies-Bergère. By then thirty years old, she wanted to marry and have children. She realized the first desire on 30 November 1937, when she wed Jean Lion, a rich and handsome Jewish playboy and sugar broker. After fourteen months of marriage, during which Baker did not become pregnant and Lion continued his wild ways, she filed for divorce, which was granted in 1942.

In June of 1940 German troops invaded Paris. Baker, who refused to perform either for racist Nazis or for their French sympathizers, fled to Les Milandes, her fifteenth-century château in the Dordogne, with her maid, a Belgian refugee couple, and her beloved dogs. Since September 1939 Baker had served as an “honorable correspondent,” gathering information about German troop locations for French military intelligence at embassy and ministry parties in Paris. Once Charles de Gaulle had declared himself leader of Free France in a radio broadcast from London and called for the French to resist their German occupiers, Baker joined “résistance” and was active in it throughout World War II, working mostly in North Africa. For her heroic work she was awarded the Croix de Guerre, and de Gaulle himself gave her a gold cross of Lorraine, the symbol of the Fighting French, when he established headquarters in Algiers in the spring of 1943. Baker was a tireless ambassador for the Free France movement and for de Gaulle, performing for British, American, and French soldiers in North Africa and touring the Middle East to raise money for the cause. In recognition of the propaganda services she performed during this tour, she was made a sublieutenant of the Women’s Auxiliary of the French Air Force. After the war de Gaulle awarded Baker the coveted Medal of Resistance.

Moving into the 1950s Baker harnessed her formidable energies behind two causes. The first was her own pursuit of racial harmony and human tolerance in the form of her “Rainbow Tribe.” To demonstrate the viability of world brotherhood, with the orchestra leader Jo Bouillon, whom she had married in 1947, Baker adopted children of many nationalities, races, and religions and installed them at Les Milandes. In order to support the family that eventually numbered thirteen and to finance the massive renovation of the château and related construction projects, Baker returned to the stage. A quick trip to the United States in 1948 was as unsuccessful as the one twelve years earlier and left her convinced that, if possible, race relations there were even worse than before. This realization prompted Baker’s second cause, the pursuit of civil rights for black Americans through the desegregation of hotels, restaurants, and nightclubs.

Traveling with a $250,000 Parisian wardrobe; singing in French, Spanish, English, Italian, and Portuguese; and performing with masterly showmanship, in 1951 Baker began an American tour in Cuba. When word of her success in Havana reached Miami, Copa City moved to book the star for a splashy engagement. Contract negotiations were long and difficult. Initiating what would become her standard demand with nightclubs, Baker insisted on a nondiscrimination clause. If management would not admit black patrons, she would not perform. The integrated audience for Baker’s show at Copa City was the first in the city’s history. Baker took her tour and her campaign against color lines from city to city—New York, Boston, Atlanta, Las Vegas, and Hollywood. And audiences loved her. Variety wrote, “The showmanship that is Josephine Baker’s. . . is something that doesn’t happen synthetically or overnight. It’s of the same tradition that accounts for the durability of almost every show biz standard still on top after many years.”

The pinnacle of Baker’s civil rights efforts was reached in August 1963 when she was invited to the great March on Washington. Dressed in her World War II uniform, Baker stood on the platform in front of the Lincoln Memorial and spoke to the crowd of thousands, blacks and whites, demonstrating for justice and equality: “You are on the eve of victory. You can’t go wrong. The world is behind you.” Baker was among those arrayed around Martin Luther King Jr. as he delivered his “I have a dream” speech. Certainly, for Josephine Baker, that day was a dream come true.

The remaining years of Baker’s life were not tranquil. Given her extravagant spending and generosity, financial problems continued to plague her. Jo Bouillon finally despaired of trying to raise so many children or to impose any fiscal responsibility and left Baker. In 1968 Les Milandes was sold, and Baker, who barricaded herself in the house with her children, was evicted. Such setbacks notwithstanding, she continued to give comeback performances, astonishing crowds with her ability to rejuvenate herself the moment she stepped on stage, the consummate star. Her final performance in Paris to a sold-out house on 9 April 1975 was no exception. The following day, just two months shy of her sixty-ninth birthday, Baker died of a cerebral hemorrhage brought on by a stroke. All of France mourned the passing of “la Joséphine.” National television broadcast the procession of her flag-draped coffin through the streets of Paris and the funeral service at the Church of the Madeleine, where twenty thousand Parisians gathered to pay their respects.

In Jazz Cleopatra: Josephine Baker in Her Time, Phyllis Rose writes of Baker’s “cabaret internationalism” as her “way of expressing a political position.” A performer of consummate skill, Baker enthralled audiences for more than a half century. But personal adulation was not enough. Like PAUL ROBESON, HARRY BELAFONTE, LENA HORNE, BILL COSBY, and others, Baker put her prestige and popularity in the service of civil rights, racial harmony, and equality for all humanity.

Baker, Josephine, and Marcel Sauvage. Les mémoires de Joséphine Baker (1927).

_______. Les mémoires de Joséphine Baker (1949).

Baker, Josephine, and Jo Bouillon. Joséphine (1976).

Colin, Paul. Le tumulte noir (1927).

Hammond, Bryan, and Patrick O’Connor. Josephine Baker (1988).

Rose, Phyllis. Jazz Cleopatra: Josephine Baker in Her Time (1989).

Obituary: New York Times, 13 April 1975.

—KAREN C. C. DALTON

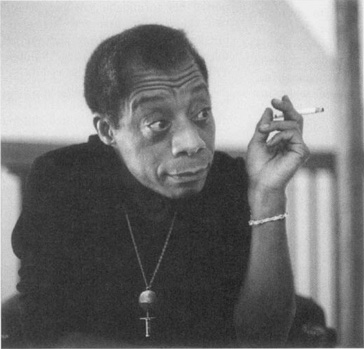

BALDWIN, JAMES

BALDWIN, JAMES(2 Aug. 1924–30 Nov. 1987), author, was born James Arthur Baldwin in Harlem, in New York City, the illegitimate son of Emma Berdis Jones, who married the author’s stepfather, David Baldwin, in 1927. David Baldwin was a laborer and weekend storefront preacher who had an enormous influence on the author’s childhood; his mother was a domestic who had eight more children after he was born. Baldwin was singled out early in school for his intelligence, and at least one white teacher, Orrin Miller, took a special interest in him. At P.S. 139, Frederick Douglass Junior High School, Baldwin met black poet COUNTÉE CULLEN, a teacher and literary club adviser there. Cullen saw some of Baldwin’s early poems and warned him against trying to write like LANGSTON HUGHES, SO Baldwin turned from poetry to focus more on writing fiction. In 1938 he experienced a profound religious conversion at the hands of a female evangelist/pastor of Mount Cavalry of the Pentecostal Faith, which he later wrote about in his first novel, Go Tell It on the Mountain (1953), in his play The Amen Corner (1968), and in an essay in The Fire Next Time (1963). Saved, Baldwin became a Sunday preacher at the nearby Fireside Pentecostal Assembly.

In 1938 Baldwin entered De Witt Clinton High School in the Bronx; he graduated in 1942. There Baldwin was challenged intellectually and was able to escape home and Harlem. He wrote for the school magazine, the Magpie, and began to frequent Greenwich Village, where he met black artist BEAUFORD DELANEY, an important early influence. Torn between the dual influences of the church and his intellectual and artistic private life, Baldwin finally made a choice. At age sixteen he began a homosexual relationship with a Harlem racketeer and later said he was grateful to the older man throughout his life for the love and self-validation he brought to the tormented and self-conscious teenager. As a preacher, Baldwin considered himself a hypocrite. At this same time, he discovered that David Baldwin was not, in fact, his real father and began to understand why he had felt deeply rejected as a child and had hated and feared his father. Fearing gossip about his homosexual relationship would reach his family and church, Baldwin broke with both the racketeer and the church. Now eighteen, he also moved away from home, taking a series of odd jobs in New Jersey and spending free time in the Village with artists and writers, trying to establish himself. He returned home in 1943 to care for the family while his stepfather was dying of tuberculosis. A few hours after his father’s death, his youngest sister was born, named by James Baldwin, the head of the family. The Harlem riot of 1943 broke out in the midst of this family upheaval, all of which Baldwin described eloquently in Notes of a Native Son (1955).

James Baldwin, author of Go Tell It on the Mountain, photographed in Paris in 1975. © Sophie Bassouls/CORBIS SYGMA

After his father’s funeral Baldwin left home for the last time, determined to become a writer. In 1944 he met RICHARD WRIGHT, who helped him get a Eugene F. Saxon Fellowship to work on his first novel, then titled “In My Father’s House.” He gave part of the $500 grant to his mother and tried to start his literary career. Although Baldwin’s first novel was rejected by two publishers, he began to have some success publishing book reviews and essays, establishing a name and a reputation. At the same time, he had difficulty extracting himself from the influence of Richard Wright, who became for Baldwin the literary father that he had to reject, as David Baldwin had been the punishing stepfather to be overcome. With what was left of the Rosenwald Fellowship he had received in 1948, Baldwin, frustrated by the fits and starts of his writing career and tired of America’s racism, bought a one-way air ticket to Paris and left the United States on 11 November.

In Paris, Baldwin met writers such as Jean-Paul Sartre, Jean Genet, and Saul Bellow. He garnered notice as a critic with the essay “Everybody’s Protest Novel,” which came out in Partisan Review in 1949. Although mostly a critique of Harriet Beecher Stowe’s Uncle Tom’s Cabin, this was the first of a series of three essays in which Baldwin attacked his literary mentor, Wright. Baldwin followed with “Many Thousand Gone” in 1951 and, after Wright’s death, “Alas Poor Richard” in 1961. But not until he took himself, his typewriter, and his BESSIE SMITH records to a tiny hamlet high in the Swiss Alps in 1951 did Baldwin begin to work in earnest on his first and best novel, Go Tell It on the Mountain. In this autobiographical family novel, fourteen-year-old John Grimes undergoes an emotional-psychological-religious crisis of adolescence and is “saved.” Go Tell It on the Mountain explores the histories and internal lives of John’s stepfather Gabriel, mother Elizabeth, and Aunt Florence, spanning the years from 1875 to the Depression and including “the Great Migration” from the South to Harlem. It was well received and was nominated for the National Book Award in 1954; Baldwin said in an interview with Quincy Troupe that he was told it did not win because RALPH ELLISON’s Invisible Man had won in 1953 and America was not ready to give this award to two black writers in a row.

Baldwin won a Guggenheim grant to work on a second novel, published in 1956 as Giovanni’s Room, about a homosexual relationship and with all-white characters in a European setting. Baldwin’s American publisher turned it down for its honesty, so Baldwin had to publish Giovanni’s Room first in London. It was a book Baldwin had to write, he said in an interview with Richard Goldstein, “to clarify something for myself.” Baldwin went on to say, “The question of human affection, of integrity, in my case, the question of trying to become a writer, are all linked with the question of sexuality.” The central character, David, a young American living in Paris, is forced to choose between his fiancée, Hella, and his male lover Giovanni. David rejects Giovanni, who is later tried and executed for the murder of an aging homosexual. Racked with guilt, David reveals his true homosexual nature and breaks his engagement, making Giovanni the injured martyr and moral pole in the novel.

Baldwin’s first collection of essays, Notes of a Native Son, appeared in 1955. These autobiographical and political pieces made Baldwin famous as an eloquent and experienced commentator on race and culture in America. Here he says on his father’s funeral,

This was his legacy: nothing is ever escaped. That bleakly memorable morning I hated the unbelievable streets and the Negroes and whites who had, equally, made them that way. But I knew that it was folly, as my father would have said, this bitterness was folly. It was necessary to hold on to the things that mattered. The dead man mattered, the new life mattered; blackness and whiteness did not matter; to believe that they did was to acquiesce in one’s own destruction. Hatred, which could destroy so much, never failed to destroy the man who hated and this was an immutable law.

(Bantam ed. [1968], 94–95)

Baldwin returned periodically to the United States throughout the 1950s and 1960s, but never to stay. He first visited the South in 1957 and met MARTIN LUTHER KING JR. In 1961 he published the collection of essays Nobody Knows My Name: More Notes of a Native Son. By 1963 he was prominent enough to be featured on the cover of Time magazine as a major spokesman for the early civil rights movement after another collection of essays, The Fire Next Time, arguably Baldwin’s most influential work, appeared. His first play, Blues for Mr. Charlie (1964), a fictionalized account of the 1955 Mississippi murder of fourteen-year-old EMMETT TILL, followed. In The Fire Next Time Baldwin effectively honed his prophetic, even apocalyptic rhetoric about racial tensions in America, fusing his themes of protest and love. During this period Baldwin had also published his third novel, Another Country, in 1962. His influence in national politics and American literature had reached a peak.

Another Country took Baldwin six years to complete; it eventually sold four million copies after a slow start with negative reviews. It is considered to be Baldwin’s second-best novel. In it Baldwin portrays multiple relationships involving interracial and bisexual love through a third-person point of view. Again he looks for resolutions to racial and sexual tensions through the power of love. The characters, however, often have trouble distinguishing sex from love and sorting through their attitudes toward sex, race, and class. Though successful, the novel is somewhat unwieldy with nine major characters, dominated by black jazz drummer Rufus Scott, who commits suicide at the end of the first chapter. The conclusion leaves readers with the hope that some of these troubled characters can achieve levels of self-understanding that will allow them to continue searching for “another country” within flawed and racist America. As Nigerian writer Wole Soyinka wrote in 1989,

In the ambiguities of Baldwin’s expression of social, sexual, even racial and political conflicts will be found that insistent modality of conduct, and even resolution, celebrated or lamented as a tragic omission—love. . . . James Baldwin’s was—to stress the obvious—a different cast of intellect and creative sensibility from a Ralph Ellison’s, a Sonia Sanchez’s, a Richard Wright’s, an AMIRI BARAKA’s, or an Ed Bullins’s. He was, till the end, too deeply fascinated by the ambiguities of moral choices in human relations to posit them in raw conflict terms. His penetrating eyes saw the oppressor as also the oppressed. Hate as a revelation of self-hatred, never unambiguously outward-directed. Contempt as thwarted love, yearning for expression. Violence as inner fear, insecurity. Cruelty as an inward-turned knife. His was an optimistic, grey-toned vision of humanity in which the domain of mob law and lynch culture is turned inside out to reveal a landscape of scarecrows, an inner content of straws that await the compassionate breath of human love.

(Troupe, 11, 17–18)

With the death of Martin Luther King Jr., and the change in the civil rights movement of the late 1960s from integrationist to separatist, Baldwin’s writing, according to many critics, lost direction. The last two decades of his life he spent mostly abroad, particularly in France, which may have increased his distance from America in his work. In the essay collection No Name in the Street (1972), Baldwin discussed his sadness over the movement’s waning. At the same time, he found himself the subject of attacks by new black writers such as ELDRIDGE CLEAVER, much like his own rejection of Richard Wright in the 1950s. The Devil Finds Work (1976) is Baldwin’s reading of racial stereotypes in American movies, and The Evidence of Things Not Seen (1985), an account of the Atlanta child murder trials, was unsuccessful, although the French translation of this book was very well received. Baldwin also wrote a series of problematic novels in his later years: Tell Me How Long the Train’s Been Gone (1968), If Beale Street Could Talk (1974), and Just above My Head (1979). In these novels Baldwin seems to go over the familiar ground of the first three novels: racial, familial, and sexual conflicts in flawed, autobiographical plots. He never again achieved the mastery of his first novel, Go Tell It on the Mountain, one of the key texts in all of African American literature and of American literature as a whole.

After Baldwin died on the French Riviera, his funeral was celebrated on 8 December 1987 at the Cathedral of St. John the Divine in New York, where MAYA ANGELOU, TONI MORRISON, AMIRI BARAKA, the French ambassador Emmanuel de Margerie, and other notables spoke and performed. Baldwin has generally been considered to be strongest as an essayist, though he published one outstanding novel, and weakest as a playwright because he became too didactic at the expense of dramatic art. His achievements and influence tended to get lost in the sheer productivity of his career, especially as his later work was judged not to measure up to his earlier work. After his death scholars were able to look at Baldwin’s contribution with perspective and a sense of closure, and his literary stature grew accordingly.

Baldwin’s personal papers and manuscripts are in the James Weldon Johnson Collection, Beinecke Rare Book and Manuscript Library, Yale University; the Berg collection at the New York Public Library, and the Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture of the New York Public Library, among other repositories.

Books by Baldwin not mentioned above include Going to Meet the Man (1965), A Dialogue: James Baldwin and NIKKI GIOVANNI (1971), One Day When I Was Lost: A Scenario Based on ALEX HALEY’s “The Autobiography of MALCOLM X” (1972), A Rap on Race (with Margaret Mead [1973]), Little Man, Little Man: A Story of Childhood (1976), Jimmy’s Blues: Selected Poems (1983), The Price of the Ticket: Collected Nonfiction (1985), and Perspectives: Angles of African Art, ed. James Baldwin et al. (1987).

Campbell, James. Taking at the Gates: A Life of James Baldwin (1991).

Gates, Henry Louis, Jr. “The Welcome Table [James Baldwin]” in Thirteen Ways of Looking at a Black Man (1997).

Leeming, David Adams. James Baldwin: A Biography (1994).

Porter, Horace A. Stealing the Fire: The Art and Protest of James Baldwin (1989).

Standley, Fred L., and Nancy V. Burt, eds. Critical Essays on James Baldwin (1988).

_______, and Louis H. Pratt, eds. Conversations with James Baldwin (1989).

Troupe, Quincy, ed. James Baldwin: The Legacy (1989).

Weatherby, W. J. James Baldwin: Artist on Fire (1989).

Obituaries: New York Times, 2 Dec. 1987; Washington Post, 5 Dec. 1987; New York Review of Books 34 (Jan. 1988).

—ANN RAYSON

BANNEKER, BENJAMIN

BANNEKER, BENJAMIN(9 Nov. 1731–19 Oct. 1806), farmer and astronomer, was born near the Patapsco River in Baltimore County in what became the community of Oella, Maryland, the son of Robert, a freed slave, and Mary Banneky, a daughter of a freed slave named Bannka and Molly Welsh, a freed English indentured servant who had been transported to Maryland. Banneker was taught by his white grandmother to read and write from a Bible. He had no formal education other than a brief attendance at a Quaker one-room school during winter months. He was a voracious reader, informing himself in his spare time in literature, history, religion, and mathematics with whatever books he could borrow. From an early age he demonstrated a talent for mathematics and for creating and solving mathematical puzzles. With his three sisters he grew up on his father’s tobacco farm, and for the rest of his life Banneker continued to live in a log house built by his father.

At about the age of twenty Banneker constructed a striking clock without ever having seen one, although tradition states he may once have examined a watch movement. He approached the project as a mathematical challenge, calculating the proper sizes and ratios of the teeth of the wheels, gears, and pinions, each of which he carved from wood with a pocket knife, possibly using a piece of metal or glass for a bell. The clock became a subject of popular interest throughout the region and many came to see and admire it. The timepiece operated successfully for more than forty years, until his death.

After his father’s death in 1759, Banneker continued to farm tobacco, living with his mother until she died some time after 1775. Thereafter he lived alone, his sisters having one by one married and settled in the region. They attended to his major household needs. His life was limited almost entirely to his farm, remote from community life and potential persecution because of his color, until the advent of new neighbors.

In about 1771 five Ellicott brothers of Bucks County, Pennsylvania, purchased large tracts of land adjacent to the Banneker farm and began to develop a major industrial community called Ellicott’s Lower Mills (now Ellicott City, Maryland). They initiated the large-scale cultivation of wheat in the state, built flour mills, sawmills, an iron foundry, and a general store that served not only their own needs but also those of the region. They marketed their flour by shipping it from the port of Baltimore. Banneker met members of the Ellicott family and often visited the building sites to watch each structure as it was being erected, intrigued particularly by the mechanisms of the mills.

George Ellicott, a son of one of the brothers, who built a stone house near the Patapsco River, often spent his leisure time in the evenings pursuing his hobby of astronomy. As he searched the skies with his telescope, he would explain what he saw to neighbors who came to watch. Banneker was frequently among them, fascinated by the new world in the skies opened up by the telescope. Noting his interest, in 1789 young Ellicott lent him a telescope, several astronomy books, and an old gateleg table on which to use them. Ellicott promised to visit Banneker as soon as he could to explain the rudiments of the science. Before he found time for his visit, however, Banneker had absorbed the contents of the texts and had taught himself enough through trial and error to calculate an ephemeris for an almanac for the next year and to make projections of lunar and solar eclipses.

Banneker, now age fifty-nine, suffered from rheumatism or arthritis and abandoned farming. He subsequently devoted his evening and night hours to searching the skies; he slept during the day, a practice that gained him a reputation for laziness and slothfulness from his neighbors.

Early in 1791 Banneker’s new skills came to the attention of Major Andrew Ellicott, George’s cousin, who had been appointed by President George Washington to survey a ten-mile square of land in Virginia and Maryland to become the new site of the national capital. Major Ellicott needed an assistant capable of using astronomical instruments for the first several months of the survey until his two brothers, who generally worked with him, became available. He visited Ellicott’s Lower Mills to ask George to assist him for the interim, but George was unable to do so and recommended Banneker.

At the beginning of February 1791 Banneker accompanied Major Ellicott to Alexandria, Virginia, the beginning point of the survey, and was installed in the field observatory tent where he was to maintain the astronomical field clock and use other instruments. Using the large zenith sector, his responsibility was to observe and record stars near the zenith as they crossed the meridian at different times during the night; the observations were to be repeated a number of nights over a period of time. After he had corrected the data he collected for refraction, aberration, and nutation and compared it with data in published star catalogs, Banneker determined latitude based on each of the stars observed. He also used the transit and equal altitude instrument to take equal altitudes of the sun, by which the astronomical clock was periodically checked and rated.

Banneker had the use of Major Ellicott’s texts and notes, from which he continued to learn, and spent his leisure hours calculating the ephemeris for an almanac for 1792. In April, with the arrival of Major Ellicott’s brothers, Banneker returned to his home. He was paid the sum of sixty dollars for his services and travel. Ellicott was paid five dollars a day exclusive of room and board while his assistant surveyors were paid two dollars a day. Banneker still supported himself primarily with proceeds from his farm.

Shortly after his return home, with the assistance of George Ellicott and family, Banneker’s calculations for an almanac were purchased and published by Baltimore printers Goddard & Angeli as Benjamin Banneker’s Pennsylvania, Delaware, Maryland and Virginia Almanack and Ephemeris, for the Year of Our Lord, 1792 . . . ; a second edition was produced by Philadelphia printer William Young. The almanac contained a biographical sketch of Banneker written by Senator James McHenry, who presented Banneker’s achievement as new evidence supporting arguments against slavery.

Shortly before the almanac’s publication, Banneker sent a manuscript copy of his calculations to Thomas Jefferson, secretary of state, with a covering letter urging the abolition of slavery. Jefferson replied, “No body wishes more than I do to see such proofs as you exhibit, that nature has given to our black brethren, talents equal to those of the other colors of men, and that the appearance of a want of them is owing merely to the degraded condition of their existence. . . . No body wishes more ardently to see a good system commenced for raising the condition both of their body & mind to what it ought to be.” The exchange of letters between Banneker and Jefferson was published as a pamphlet by Philadelphia printer David Lawrence and distributed widely at the same time that the almanac appeared. Promoted by the abolitionist societies of Pennsylvania and Maryland, the almanac sold in great numbers.

Encouraged by his first success, Banneker continued to calculate ephemerides for almanacs that were published for the succeeding five years and sold widely in the United States and England. A total of at least twenty-eight editions of his almanacs were published, largely supported by the abolitionist societies. Although he continued to calculate ephemerides each year until 1804 for his own pleasure, diminishing interest in the abolitionist movement failed to find a publisher for them after the 1797 almanac.

Although he was not associated with any particular religion, Banneker was deeply religious and attended services of various denominations whenever ministers or speakers visited the region, preferring meetings of the Society of Friends. He was described as having “a most benign and thoughtful expression,” as being of erect posture despite his age, scrupulously neat in dress. Another who knew him noted, “He was very precise in conversation and exhibited deep reflection.” Banneker died in his sleep during a nap after having taken a walk early one Sunday morning a month short of his seventy-fifth birthday. He had arranged that immediately after his death, all of his borrowed texts and instruments were to be returned to George Ellicott, which was done before his burial two days later. During his burial in the family graveyard on his farm, his house burst into flames and was destroyed. All that survived were a few letters he had written, his astronomical journal, his commonplace book, and the books he had borrowed.

The publication of Banneker’s almanacs brought him international fame in his time, and modern studies have confirmed that his figures compared favorably with those of other contemporary men of science who calculated ephemerides for almanacs. Long thought lost, the sites of Banneker’s house and outbuilding have been the subjects of an archaeological excavation from which various artifacts have been recovered. Banneker has been memorialized in the naming of several institutes and secondary schools. Without the limitation of opportunity because of his regional location and the state of science in his time, Banneker would undoubtedly have emerged as a far more important figure in early American science than merely as the first black man of science.

Most of Banneker’s personal papers, correspondence, and manuscripts are privately owned.

Bedini, Silvio A. The Life of Benjamin Banneker (1972).

Tyson, Martha Ellicott. Banneker, the Afric-American Astronomer: From the Posthumous Papers of Martha E. Tyson (1884).

—SILVIO A. BEDINI

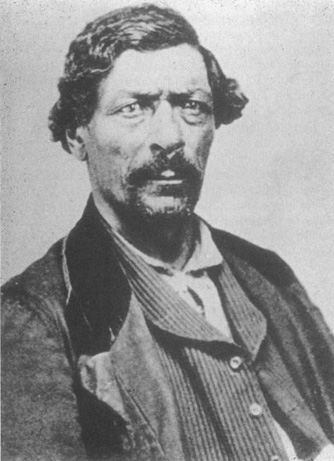

BANNISTER, EDWARD MITCHELL

BANNISTER, EDWARD MITCHELL(c. 1826–9 Jan. 1901), painter, was born in St. Andrews, New Brunswick, Canada, the son of Hannah Alexander, a native of New Brunswick, and Edward Bannister, from Barbados. While his birth date has generally been given as 1828, recent research has suggested that he was born several years earlier. After the death of his father in 1832, Edward was raised by his mother, whom he later credited with encouraging his artistic aspirations: “The love of art in some form came to me from my mother. . . . She it was who encouraged and fostered my childhood propensities for drawing and coloring” (Holland, Edward Mitchell Bannister, 17). His mother died in 1844, and Edward and his younger brother, William, were sent to work for a wealthy local family, where he was exposed to classical literature, music, and painting. Edward’s interest in art continued, and an early biography of the artist reported that “the results of his pen might be seen on the fences and barn doors or wherever else he could charcoal or crayon out rude likenesses of men or things about him” (Hartigan, 71).

In the early 1850s Bannister settled in Boston, where he supported himself by working as a hairdresser. By 1853 he was employed by Madame Christiana Carteaux, a successful black entrepreneur who operated several beauty salons and sold her own line of hair products and who would later become his wife. Unable to persuade any of the local established artists to take a black man on as a pupil, Bannister studied art independently during this period. Despite these obstacles, he achieved some local recognition as a landscapist and portrait painter. In 1854 Dr. John V. DeGrasse, the first black doctor admitted to the Massachusetts Medical Society, gave Bannister his first commission, a harbor scene entitled The Ship Outward Bound (location unknown).

One of the first African American painters to receive national recognition, Edward M. Bannister was known not only for landscapes and seascapes but also for portraits and genre works, such as The Newspaper Boy of 1869. Art Resource/Smithsonian American Art Museum, Gift of Jack Hafif and Frederick Weingeroff

On 10 June 1857 Bannister and Carteaux were married, and by the following year Bannister had established himself as a full-time artist. His wife’s financial and emotional support was critical to his success. As he recalled in later years, “I would have made out very poorly had it not been for her, and my greatest successes have come through her, either through her criticisms of my pictures, or the advice she would give me in the matter of placing them in public” (Holland, Edward Mitchell Bannister, 8). The couple was active in Boston’s African American arts community and in the abolitionist movement. Bannister served as an officer of the Union Progressive Society and the Colored Citizens of Boston and was a delegate to the New England Colored Citizens Convention in 1859 and 1865.

In the 1860s Bannister began his professional artistic career in earnest. A listing in the Boston city directory identifies him as a portrait painter, and in 1862 he traveled to New York to study photography in order to enter into the lucrative daguerreotype business. Bannister advertised his services as a daguerreotypist in 1863 and 1864, but none of his photographs has been identified. During these years he also undertook his only formal art training, taking life-drawing classes at the Lowell Institute between 1863 and 1865 with the sculptor and anatomist Dr. William Rimmer. Few works survive from this period of Bannister’s career, but his portraits of Prudence Nelson Bell (1864, private collection) and of Robert Gould Shaw (c. 1864, location unknown), the latter raffled to raise money for the families of black soldiers killed in the Civil War, are evidence both of his success as a portraitist and his ties to Boston’s abolitionist and activist communities.

In 1869 Bannister left Boston and settled in Providence, Rhode Island, perhaps because of his wife’s family ties to the area. He announced his professional arrival in the city by exhibiting two paintings, a portrait of the famous Boston abolitionist William Lloyd Garrison (location unknown) and Newspaper Boy (1869, National Museum of American Art [NMAA]), a sensitive portrait of one of the many young boys who sold papers on the streets of Boston. Although the racial identity of the fair-skinned child is uncertain, the painting is often discussed as one of Bannister’s few known works dealing directly with African American subjects.

Upon moving to Providence, Bannister began to paint fewer portraits and more landscapes and sea scenes, the work for which he is primarily known today. While he never traveled to Europe, his work—like the work of many American painters—was strongly influenced by European art, particularly the landscape paintings of the Barbizon school. These loosely handled scenes of peasants and farm animals working in bucolic harmony touched a chord among many American landscape painters, and in works such as Driving Home the Cows (1881, NMAA) and Hauling Rails (1891, NMAA), Bannister created similarly idyllic images of pastoral landscapes. In Haygatherers (c. 1893, private collection), Bannister extended this poetic vision of rural life to a specifically American context, depicting African American women and children loading a cart with hay. The artist also painted many scenes of Rhode Island’s coastline, which he observed from the decks of his small yacht, the Fanchon. In addition to his finished oil paintings completed in the studio, Bannister did many sensitively handled oil sketches and drawings, and these small works are among the freshest and most attractive of his works.

Like many nineteenth-century artists, Bannister viewed the depiction of the natural world as a spiritual endeavor. In a lecture delivered in 1886, he described the artist’s role as “the interpreter of the infinite, subtle qualities of the spiritual idea centreing [sic] in all created things, expounding for us the laws of beauty, and so far as finite mind and executive ability can, revealing to us glimpses of the absolute idea of perfect harmony” (Hartigan, 77).

Bannister came to national attention when his painting Under the Oaks (location unknown) was awarded a first-prize medal at the Centennial Exhibition in Philadelphia in 1876. The only other African American artist represented at the exhibition was EDMONIA LEWIS, whose life-sized sculpture, Death of Cleopatra, caused quite a sensation. Bannister had submitted his work without any biographical detail, and he later recalled the surprise of the awards committee upon learning of his racial identity: “Finally when I succeeded in reaching the desk where inquiries were made, I endeavored to gain the attention of the official in change. He was very insolent. . . . I was not an artist to them, simply an inquisitive colored man; controlling myself, I said deliberately, ‘I am interested in the report that Under the Oaks has received a prize; I painted the picture.’ An explosion could not have made a more marked impression. Without hesitation he apologized, and soon every one in the room was bowing and scraping to me” (Hartigan, 70). A Boston collector, John Duff, purchased the painting for fifteen hundred dollars, a substantial sum of money at the time.

This success led to increased demand for his work and to his visibility and prominence in the local Providence art world. Bannister served on the first board of the new Rhode Island School of Design (RISD) and was a founding member of the Providence Art Club. Officially chartered in 1880, the club served as a center for Providence’s artistic community, hosting lectures and social events and mounting regular exhibitions in the spring and fall. Bannister showed his work at the club’s exhibitions for the remainder of his career and served regularly on the executive committee. His work was purchased both by African American patrons, such as JOHN HOPE, George Downing Jr., and MADAME SISSIERETTA JONES, and by local white collectors, such as Isaac Bates and Joseph Ely.

While landscape and sea scenes remained Bannister’s specialty, he made occasional forays into religious and history painting throughout his career. An account of Bannister’s studio in the 1860s mentions a painting of Cleopatra Waiting to Receive Marc Antony (location unknown), and in the 1890s he painted several literary compositions, including a small oil sketch of Leucothea Rescuing Ulysses (1891, Newport Hospital, Rhode Island) and scenes from Edmund Spenser’s Faerie Queen. Bannister’s figure paintings are less confident in their execution than his landscapes, perhaps because of his lack of formal artistic training, but he continued to experiment artistically throughout his career. The late work Street Scene (late 1890s, Museum of Art, RISD), a brightly colored impressionist view of an urban thoroughfare, demonstrates Bannister’s continued interest in experimenting with new styles and subjects even in the final years of his career.

Bannister died of a heart attack on 9 January 1901, while attending a prayer meeting at the Elmwood Street Baptist Church in Providence. In May of that year a memorial exhibition of his work, including 101 paintings, was mounted at the Providence Art Club. In the catalog the artist John Arnold recalled, “His gentle disposition, his urbanity of manner and his generous appreciation of the work of others made him a welcome guest in all artistic circles. . . . He was par excellence a landscape painter, the best our state has ever produced. He painted with profound feeling, not for pecuniary results, but to leave upon the canvas his impression of natural scenery, and to express his delight in the wondrous beauty of land, sea, and sky” (Painters of Rhode Island, 1996, 13).

Bannister’s papers are at the Archives of American Art at the Smithsonian Institution, Washington, D.C.

Hartigan, Lynda Roscoe. Sharing Traditions: Five Black Artists in Nineteenth-Century America (1985).

Holland, Juanita. Edward Mitchell Bannister, 1828–1901 (1992).

_______. “To Be Free, Gifted and Black: African American Artist, Edward Mitchell Bannister” in International Review of African American Art 12.1 (1995).

—PAMELA M. FLETCHER

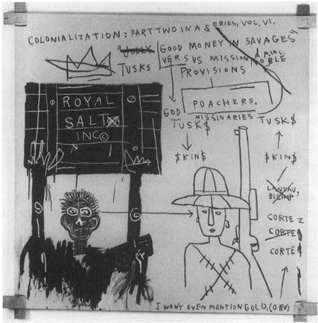

BARAKA, AMIRI

BARAKA, AMIRI(7 Oct. 1934–), poet, playwright, educator, and activist, was born Everett Leroy Jones in Newark, New Jersey, the eldest of two children to Coyette Leroy Jones, a postal supervisor, and Anna Lois Russ, a social worker. Jones’s lineage included teachers, preachers, and shop owners who elevated his family into Newark’s modest, though ambitious, black middle class. His own neighborhood was black, but the Newark of Jones’s youth was mostly white and largely Italian. He felt isolated and embattled at McKinley Junior High and Barringer High School, yet he excelled in his studies, played the trumpet, ran track, and wrote comic strips.

Graduating from high school with honors at age fifteen, Jones entered the Newark branch of Rutgers University on a science scholarship. In 1952, after his first year, he transferred to Howard University, hoping to find a sense of purpose at a black college that had eluded him at the white institution. It was at this point that a long process of reinventing himself first became evident; he changed the spelling of his name to “LeRoi” and told anyone who asked that he was going to become a doctor. Yet, he was more interested in pledging fraternities than getting good grades. In retrospect Jones blamed the college’s “petty bourgeois Negro mentality” (Autobiography, 113) for his academic failure and came to regard black colleges as places where they “teach you to pretend to be white” (Watts, 22).

With his college ambitions dashed, Jones joined the air force in 1954, where he trained as a weatherman. He graduated at the top of his class and was stationed at Ramey Air Force Base in Puerto Rico. There he became an avid reader of Proust, Hemingway, Dostoyevsky, Sartre, and Camus. He subscribed to literary journals such as the Partisan Review and began to send his poems to publishers, who promptly rejected them. Jones claimed that his possession of left-leaning reading material was responsible for his dishonorable discharge from the military in 1957. Working as a stock clerk at the Gotham Book Mart in Manhattan, he resumed a friendship with Steve Korret, an aspiring writer in New York’s Greenwich Village.

Through Korret, Jones was introduced to an avant-garde literary scene and a bohemian culture that profoundly altered his life. Allen Ginsberg, the doyen of the Beat poets of the 1950s, became a mentor after Jones wrote him a letter on toilet paper to show how hip he was. Charles Olson, a leader of the ultramodern Black Mountain poets, influenced his writing, and even LANGSTON HUGHES, who occasionally gave readings in the Village accompanied by bassist CHARLES MINGUS, encouraged him and nurtured a friendship that Jones cherished deeply. In 1958 Jones married, in a Buddhist temple, a white, Jewish woman, Hettie Cohen, the secretary of The Record Changer, a jazz magazine where Jones worked as the shipping manager. Together they had two children and published Yugen, a chic, though short-lived, literary magazine.

By the late 1950s Jones’s poetry began to appear in such periodicals as Naked Ear, Evergreen Review, and Big Table, and in 1959 he founded a publishing company, Totem Press, which issued his first collection of poems, Preface to a Twenty-Volume Suicide Note (1961). Though his poetry at this point had a distinct blues idiom, it was not yet overtly political. That transformation was prompted by a visit to Cuba in 1960, where he saw artists as revolutionaries who advanced Cuban nationalism. This experience led him to view his own situation more critically. Soon after returning he began to write polemical essays such as “Cuba Libre,” he became a street activist, and he urged his Beat peers to strive for greater political relevance in their work. Jones then demonstrated that he was a serious student of history and music with the publication of Blues People: Negro Music in White America (1963). RALPH ELLISON remarked that “the tremendous burden of sociology which Jones would place upon this body of music is enough to give even the blues the blues” (Justin Driver, New Republic, 25 Apr. 2002), but most critics regarded the book as an important contribution.

In 1963 Jones tried his hand at playwriting and discovered that here, too, he had the Midas touch. Dutchman, a play about a “black boy with a phony English accent” who has a fatal encounter with an attractive white woman on a New York City subway, won an Obie in 1964, and became a sensation in many circles; it continues to be performed, and established Jones’s new persona as an American firebrand. The following year, while at a book party surrounded by his cohorts from the Village, Jones received word that MALCOLM X had been assassinated up in Harlem. He later remembered this moment as an epiphany in which he realized that he was in the wrong crowd: “I felt that I had been dominated by white ideas, even down to my choice of wife” (Village Voice, 12 Dec. 1980). He left his wife and moved to Harlem, where he established the Black Arts Repertory Theater-School and soon became a leading black nationalist.

Jones’s only novel, The System of Dante’s Hell, was published in 1965, and much of the poetry he wrote during this period was a repudiation of his earlier life and career. In “Black Dada Nihilismus” he wrote, “Rape the white girls. Rape / their fathers. . . choke my friends,” and in “The Liar” he reasoned, “What I thought was love / in me, I find a thousand instances / as fear.” In “Black Art” he lays out his criteria for black poetry in lines such as “Poems are bullshit unless they are / teeth. . . . We want poems / like fists beating niggers out of Jocks / or dagger poems in the slimy bellies / of the owner-jews,” and he speaks of his verses as a “poem cracking steel knuckles in a jew-lady’s mouth.” Later, in an essay entitled “Confessions of a Former Anti-Semite,” he acknowledged that during his “personal trek through the wasteland of anti-Semitism,” his need to make an intellectual and political break with American liberals was unfortunately expressed as a venomous attack on Jews—who had earlier been his greatest liberal influences—and was often motivated by an unresolved anger towards his ex-wife. “Anti-Semitism,” he wrote, “is as ugly an idea and as deadly as white racism” (Village Voice, 12 Dec. 1980).

The treatment of gays and homosexuality in Jones’s work is highly problematic, as it is both complex and contradictory. Two of his early plays, The Baptism, set in a church, and The Toilet, set in a men’s room, feature gay characters who can be interpreted sympathetically. According to Werner Sollors, “Homosexuality is viewed positively by Baraka both as an outsider-situation analogous to, though now also in conflict with, that of Blackness, and as a possibility for the realization of ‘love’ and ‘beauty’ against the racial gang code of a hostile society” (Sollors, 108). Ron Simmons argues that the gay tension is present in his work because Jones “never reconciled his homosexual past,” a past that Jones alludes to in The System of Dante’s Hell and ruminates about in “Tone Poem:” “Blood spoiled in the air, caked and anonymous. Arms opening, opened last night, we sat up howling and kissing. Men who loved each other. Will that be understood? That we could, and still move under cold nights with clenched-fists” (Simmons, 318). Jones concludes that race-conscious men could not safely sleep with men and be credible black nationalists. Yet, unlike ELDRIDGE CLEAVER, Jones did not see a contradiction in JAMES BALDWIN, who was explicit and unapologetic about his homosexuality. In “Jimmy!,” a stirring eulogy to Baldwin he read at Baldwin’s funeral in 1987, he credits Baldwin with starting the Black Arts Movement and pleads, “Let us one day be able to celebrate him like he must be celebrated if we are ever to be truly self determining. For Jimmy was God’s black revolutionary mouth.”

In 1966 Jones married Sylvia Robinson, a fellow poet. The following year he adopted the Swahili Muslim name Imamu Amiri Baraka (which means “spiritual leader, prince, blessed”), and she became Amina (“faithful”) Baraka. Together they had five children. Baraka never fully embraced Islam as a religion and later dropped Imamu from his name. Rather he practiced “Kawaida,” a form of cultural black nationalism that is an eclectic blend of Islamic, Egyptian, West African, and other traditions synthesized by Maulana Karenga, Baraka’s mentor from about 1967 until Baraka became a Marxist in 1974. With the publication of Home (1966), especially the seminal essay “The Myth of ‘Negro Literature,’” Baraka profoundly influenced a new generation of writers, including AUGUST WILSON, Haki Madhubuti, and Sonia Sanchez. As a political organizer in 1970, Baraka helped Kenneth Gibson to become the first black mayor of Newark, New Jersey, where Baraka had returned to live, and he was a principal organizer of the National Black Political Convention in Gary, Indiana, in 1972.

While serving a forty-eight week sentence in a Harlem halfway house in 1979, following a domestic dispute and a conviction for resisting arrest, Baraka began writing his autobiography, in which he characterizes some of the earlier sexist, racist, and specious ideological reasoning of the Black Power movement as little more than “nuttiness disguised as revolution” (Autobiography, 387). After becoming a Third World Marxist, the pace of both his writing and his activism slowed over the next two decades, during which he taught at several colleges, including Yale University, Rutgers University (where he was denied tenure), and at Stony Brook University, where he retired as Professor Emeritus in 1999. He received the American Book Awards’ Lifetime Achievement Award in 1989, and in 2002 he was named Poet Laureate of New Jersey. Yet controversy continued to dog him as the governor and state legislature introduced legislation to remove Baraka as laureate in reaction to his poem “Somebody Blew Up America,” which alleges that Israel and President George W. Bush had foreknowledge of the September 11, 2001, terrorist attack against the World Trade Center in New York City.

Baraka, Amiri. The Autobiography of Leroi Jones (1984, rpt. 1997).

_______. The LeRoi Jones/Amiri Baraka Reader (1999).

Simmons, Ron. “Baraka’s Dilemma: To Be or Not to Be?” in Black Men on Race, Gender, and Sexuality, ed. Devon Carbado (1999).

Sollors, Werner. Amiri Baraka/LeRoi Jones: The Quest for a “Populist Modernism” (1978).

Watts, Jerry Gafio. Amiri Baraka: The Politics and Art of a Black Intellectual (2001).

—SHOLOMO B. LEVY

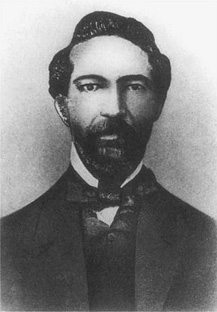

BARNETT, CLAUDE ALBERT

BARNETT, CLAUDE ALBERT(16 Sept. 1889–2 Aug. 1967), entrepreneur, journalist, and government adviser, was born in Sanford, Florida, the son of William Barnett, a hotel worker, and Celena Anderson. His father worked part of the year in Chicago and the rest of the time in Florida. Barnett’s parents separated when he was young, and he lived with his mother’s family in Oak Park, Illinois, where he attended school. His maternal ancestors were free blacks who migrated from Wake County, North Carolina, to the black settlement of Lost Creek, near Terre Haute, Indiana, during the 1830s. They then moved to Mattoon, Illinois, where Barnett’s maternal grandfather was a teacher and later a barbershop owner, and finally to Oak Park. While attending high school in Oak Park, Barnett worked as a houseboy for Richard W. Sears, cofounder of Sears, Roebuck and Company. Sears offered him a job with the company after he graduated from high school, but Barnett’s mother insisted that he receive a college education. He graduated from Tuskegee Institute with a degree in Engineering in 1906. His maternal grandfather and BOOKER T. WASHINGTON, founder and head of Tuskegee Institute, were the major influences on Barnett’s life and values. He cherished the principles of hard work, self-help, thrift, economic development, and service to his race.

Following graduation from Tuskegee, Barnett worked as a postal clerk in Chicago. While still employed by the post office, in 1913 he started his own advertising agency, the Douglas Specialty Company, through which he sold mail-order portraits of famous black men and women. He left the post office in 1915 and in 1918, with several other entrepreneurs, founded the Kashmir Chemical Company, which manufactured Nile Queen hair-care products and cosmetics. Barnett became Kashmir’s advertising manager and he toured the country to market its products and his portraits. He helped to develop a national market for Kashmir and also pioneered the use of positive advertisements. Traditional advertisements featured an unattractive black woman with a message that others should use the company’s products to avoid looking like her. In contrast, Barnett used good-looking black models and celebrities with positive messages about the beauty of black women. He visited local black newspapers to negotiate advertising space and discovered that they were desperate for national news but did not have the resources to subscribe to the established newswire services. Barnett recommended that the Chicago Defender, founded by ROBERT ABBOTT in 1905 and the most widely circulated black newspaper during the early twentieth century, establish a black news service. The newspaper rejected his proposal since it had enough sources for its own publication and feared harming its circulation by providing competitors with material.