BENGA, OTA. See Otabenga.

BENGA, OTA. See Otabenga.The decade of the 1870s brought further changes and challenges. Once the federal government passed the Fifteenth Amendment, blacks in California could vote, but Bell realized that they also needed to become politically involved. Although he supported the Republican Party of Lincoln, Bell urged his readers to vote not for a party’s candidate, but for the most qualified individual. In the late 1870s he warned African Americans to be wary of Denis Kearney’s Workingmen’s Party and its anti-Chinese platform, not because he was sympathetic to the Chinese, but because he feared repercussions for African Americans. In 1878 Bell supported the National Labor Party, and at its state convention in San Francisco, he held the position of sergeant-at-arms. Bell realized that the problems of workers—white, black, and Asian—overshadowed group identity; he simply wanted all workers to benefit from the land, and from economic, social, and political reforms through effective political leadership.

Philip Bell had other talents besides political activism. With his stuttering under control, he appeared as an actor in the Colored Amateur Company productions of Ion and Pizarro. As a literary critic, he wrote reviews of both white and black community productions of Shakespeare’s Richard III, As You Like It, and The Merchant of Venice. In a review of the latter, Bell commented, “I have always sympathized with Shylock, have considered him ‘more sinned against than sinning.’”

The late 1870s and early 1880s saw a still vigorous Bell continuing his efforts towards achieving equal rights and “elevating the character of our race.” In the mid-1880s, however, his health began to decline, forcing him to retire. During his newspaper career Bell had made very little money, and since he never married or had children, he had to depend for his support on the charity of local women. Bell never fully regained his health, and he died in San Francisco in 1889. Judge Mifflin W. Gibbs described Bell as “proud in his humanity and intellectually great as a journalist,” but perhaps the best summation of Bell’s life comes in his own words, “Action is necessary. Prompt and immediate. Agitate! Agitate! Agitate!”

The best sources of information on the life and activities of Bell are the files of the New York Colored American and Anglo-African and the San Francisco Pacific Appeal and the Elevator newspapers.

Montesano, Philip M. Some Aspects of the Free Negro Question in San Francisco, 1849–1870 (1973).

Penn, I. Garland. The Afro-American Press and its Editors (1891).

Obituary: San Francisco Bulletin, 26 and 27 Apr. 1889.

—PHILIP M. MONTESANO

BENGA, OTA. See Otabenga.

BENGA, OTA. See Otabenga. BERRY, CHUCK

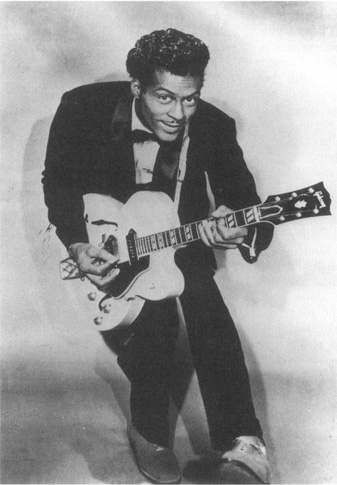

BERRY, CHUCK(18 Oct. 1926–), singer, songwriter, and guitarist, was born Charles Edward Anderson Berry in St. Louis, Missouri, the fourth of six children of Henry William Berry, a carpenter and handyman, and Martha Bell Banks. The industrious Henry Berry instilled in his son a hunger for material success and a prodigious capacity for hard work, traits which were not entirely apparent in Berry as a youth. Martha Berry, a skilled pianist and accomplished singer, passed on to her son her love for music. By the time he was a teenager, however, Berry preferred jazz, blues, and the “beautiful harmony of country music” to his mother’s Baptist hymns (Berry, 14).

Chuck Berry, who helped shape rock and roll and moved the guitar to center stage, 1956. Frank Driggs Collection

In 1944 Berry and two friends hatched an ill-considered plan to drive across the country to California. They soon ran out of money and committed a series of armed robberies in an attempt to return home. All three were arrested, convicted, and given ten-year sentences. In prison, Berry began to take music seriously, cofounding a gospel quartet and a rhythm and blues band popular with both black and white inmates. The quartet sang during services in the prison chapel and met with such success that prison officials allowed the group to sing for African American church congregations in Kansas City and St. Louis.

Berry was released on parole in 1947, and returned to St. Louis. In 1948 he married Themetta Suggs, with whom he had four children. While working menial day jobs, he studied guitar with Ira Harris, who laid the foundation of his guitar-playing style. The recordings of guitarists Charlie Christian, T-Bone Walker, and Carl Hogan, who played in Louis Jordan’s band further shaped his sound. NAT KING COLE, MUDDY WATERS, and Joe Turner were among the singers whose diverse styles he sometimes emulated. Berry’s taste, although eclectic, was firmly rooted in both the urban blues and rhythm and blues of the era.

By 1952 Berry was playing regularly in local St. Louis clubs and had developed a reputation as a capable sideman, whose flamboyant stage presence and willingness to indulge in “little gimmicks,” such as singing country and western songs, delighted audiences. Among those who noticed the rising bluesman was pianist Johnny Johnson, leader of a popular trio whose repertoire included blues, rhythm and blues, and popular songs. When one of Johnson’s sideman was indisposed, Johnson asked Berry to sit in with the band at the Cosmopolitan Club in East St. Louis.

Audiences at the Cosmopolitan Club responded enthusiastically to Berry and the club’s owner immediately asked Johnson to hire him permanently. Johnson readily agreed, explaining that Berry’s showmanship “brought something to the group that was missin”’ (Pegg, 25). Berry’s performance with Johnson’s trio on New Year’s Eve 1952 marked the beginning of a remarkable musical collaboration that produced “Roll Over Beethoven” (1956), “School Day” (1957), and “Rock and Roll Music” (1957), which, more than any other songs, defined the new musical genre of rock and roll. Although Johnson helped to shape the melodies, and his powerful left hand supplied much of the songs’ rhythmic drive, the men were not equal partners. The lyrics were Berry’s alone, and he was the sole author of songs such as “Maybellene” (1955), his first hit, and “Johnny B. Goode” (1958), one of the most honored songs in rock and roll history.

Within a few years, Berry’s role in the trio overshadowed Johnson’s, and he began to look beyond St. Louis’s African American nightclubs toward a wider audience. In 1955 he visited Chicago, hoping to build on his local success by signing a recording contract. The blues musician MUDDY WATERS, whom Berry met after a concert, directed him to Leonard Chess, who ran a small independent record company. Like many of the era’s independent labels, Chess Records produced the African American music that major labels tended to ignore. Chess agreed to record “Maybellene,” a song similar to the country and western novelties that Berry often sang, and “Wee Wee Hours,” a standard blues tune.

“Maybellene” fired Leonard Chess’s imagination. He knew that young white consumers, bored with the music that major labels produced, were searching for something new. Many had gravitated towards rhythm and blues, which, beyond its musical excellence, possessed the lure of the forbidden.

Independent labels courted this emerging market; and disk jockeys, such as Alan Freed, who began calling the music “rock and roll,” expanded it. Chess believed that “Maybellene,” with its fusion of country and western and rhythm and blues, was the perfect song for the times. It proved to be a dazzling success.

Like most of Berry’s songs, “Maybellene” sold well to both whites and blacks. Like all of his songs, it was an exercise in “signifyin’,” drawing on African American vernacular forms to speak, simultaneously, in more than one voice. While whites heard something both familiar and unexpected—a frenetic homage to country and western—African Americans heard an affectionate parody. The song reached number two on Billboard magazine’s pop chart (the “white” chart) and number one on the rhythm and blues chart (the “black” chart). “Maybellene” amalgamated black and white musical styles, exalted cars, girls, and—implicitly—sex, and moved the electric guitar to center stage, creating a musical template that generations of rock and roll musicians would follow.

Determined to repeat the success of “Maybellene,” Berry began the process of transforming himself from a competent bluesman into a brilliant rock and roller. With one eye on the cash register and the other on his growing legions of young white fans, he wrote songs that were, above all, marketable. Although producing great art was the least of his concerns, many of the songs that Berry wrote between 1955 and the early 1960s were nothing less than miniature masterpieces. His lyrics blended irony, parody, and literal-minded observation into a coherent whole. His music, while grounded in rhythm and blues, continued to draw on country and western and other popular forms.

In late 1959 and early 1960, Berry’s string of successes ended when he was arraigned on two counts of having violated the White Slave Traffic Act (Mann Act), a federal statute. The federal prosecutor in St. Louis alleged that Berry had, on two separate occasions during concert tours, transported Joan Mathis Bates, a white woman in her late teens, and Janice Norine Escalanti, a fourteen-year-old Native American girl, across state lines for immoral purposes. When the case involving Bates went to trial, both she and Berry admitted to having had a consensual sexual relationship, and Bates added that she was in love with him. The jury acquitted Berry, noting that the charges involved a voluntary relationship between two adults.

The Escalanti case, however, ended in a conviction. The jury accepted Escalanti’s testimony that she and Berry had engaged in consensual sexual relations on several occasions. The fact that the relationship was consensual had no impact on the charges; prosecutors were only required to prove that, after transporting Escalanti across state lines, Barry’s behavior had been “immoral.” While Berry denied that he had had a sexual relationship with Escalanti, he proved a nervous and unconvincing witness. The behavior of trial judge George Moore, who repeatedly interjected remarks of a racial nature into the proceedings, compounded Berry’s difficulties. Berry appealed his conviction, arguing that Moore’s hostile and prejudicial conduct had deprived him of a fair trial. A federal appellate court agreed, and sent the case back to the district court. However, in 1961 Berry was convicted a second time, and entered federal prison in 1962.

By the time Berry was released in 1963, his music had begun to sound old-fashioned. Even though songs that he wrote in prison, such as “Promised Land” (1964), rank among his best, his career as a recording artist was waning. Berry enjoyed a brief revival in 1972, when he scored his first number one hit on the pop chart with the trifling, double-entendre-filled “My Ding-A-Ling.” Although he rarely recorded after this point, Berry continued to tour, often with great success, well into his seventies.

In 2000 Johnny Johnson sued Berry, claiming that he had never received credit for cowriting many of the songs that Berry recorded in the 1950s and that he had thereby been defrauded of millions of dollars in royalties. Parts of the case were dismissed in 2001, with the court ruling that it would be impossible for Johnson to prove that he had cowritten the songs. The court also noted that because so much time has passed, many potential witnesses had died and that the memories of others had faded. In addition, Johnson had admitted in the St. Louis Post-Dispatch that he spent much of the 1950s in an alcoholic fog, rendering his testimony suspect. Although the precise nature of the relationship between the two men is likely to remain disputed, Johnson’s role was almost certainly that of an arranger of Berry’s musical ideas.

In his later years, Berry accrued honors that acknowledged his central role in reshaping popular music. He is a member of the Blues Foundation Hall of Fame, the National Academy of Popular Music Songwriter’s Hall of Fame, and, in 1986 he was among the first artists inducted into the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame.

Berry, Chuck. Chuck Berry: The Autobiography (1987).

Collis, John. Chuck Berry: The Biography (2002).

Pegg, Bruce. Brown Eyed Handsome Man: The Life and Hard Times of Chuck Berry, an Unauthorized Biography (2002).

Discography

Rothwell, Fred. Long Distance Information: Chuck Berry’s Recorded Legacy (2001).

—JOHN EDWIN MASON

BERRY, HALLE MARIA

BERRY, HALLE MARIA(14 Aug. 1966–), film actress and model, was born in Cleveland, Ohio, the daughter of Jerome Berry, a hospital attendant, and Judith Hawkins, a psychiatric nurse. Her father, an alcoholic, abandoned the family when she was four, leaving her mother to raise Halle and her sister Heidi, first in predominantly black innercity Cleveland and later in that city’s white suburbs. Berry’s childhood was troubled, in part because of the economic hardship of growing up in a single-parent household. But as the light-skinned child of an interracial couple—her mother was white, her father African American—she also endured racial taunts from both blacks and whites. Fellow students called her “zebra” and on one occasion left an Oreo cookie in her school locker. Berry never had any doubts about her own identity, however, and states on her Web site that her “race” is African American and English.

An extremely shy teenager, Berry craved acceptance from her peers and worked energetically to be the most active and popular young woman at her high school. As a cheerleader, editor of the school newspaper, an honor student, and class president, she appeared to have succeeded, but when fellow students accused her of stuffing the ballot box in the voting for prom queen, she was forced to share the title with a white student. Although this reversal suggested to Berry that whites would not accept a standard of beauty that included people of color, her success in beauty pageants suggested otherwise. By the mid-1980s an African American woman as flawlessly beautiful as Halle Berry could win Miss Teen Ohio and Miss Ohio. As a runner-up in the 1986 Miss U.S.A. pageant, Berry, then a student at Cleveland’s Cuyahoga Community College traveled to London to represent the United States in Miss World, the leading international beauty contest. Although Miss Trinidad & Tobago won the title, Berry placed sixth and created a sensation by appearing in the “national costume” segment of the pageant wearing a skimpy bikini with strands of beads and shooting stars. The outfit was purported to express “America’s advancement in space,” but it drew the ire of other contestants such as Miss Holland, who wore the traditionally bulky and much less revealing Dutch costume with clogs.

Berry found participation in beauty pageants an ideal preparation for a career in Hollywood, since it taught her how to lose and not be devastated. Considered too short at five feet six inches to be a runway model, she won bit parts in the television sitcoms Amen and A Different World, but she was rejected at her first audition for a major television role in Charlie’s Angels ’88. She did win a regular spot as a teenage model in 1989’s shortlived sitcom on ABC, Living Dolls, but increasingly found that her stunning looks and beauty pageant past kept her from landing the serious acting roles she desired. A minor but critically praised role as a crack addict in SPIKE LEE’s Jungle Fever (1991) signaled a change in her fortunes. That performance marked Berry’s first, but by no means last, effort to overcome critics, including Lee himself initially, who could not envision her as anything less than glamorous. In preparation for the role, she interviewed drug addicts and refused to bathe for ten days before shooting. Her next role, as a radio producer on the prime-time soap opera Knots Landing, was much less gritty, but it did ensure greater exposure and led to a series of prominent appearances in the film comedies Strictly Business and Boomerang (1992) and the television miniseries of ALEX HALEY’s Queen (1993).

In the 1990s Berry became one of the most bankable actors in Hollywood, appearing in popular, though not critically acclaimed movies such as Fatherhood (1993), The Flintstones (1994), and Executive Decision (1996). She received favorable reviews for these parts, but the praise—film critic Roger Ebert described her as “so warm and charming you want to cuddle her”—may have reinforced the view in Hollywood that she was best suited to light roles. At the same time, Berry’s beauty and poise earned her an MTV award in 1993 for “most desirable female,” an assessment shared by People magazine, which since 1992 has consistently listed her among the most beautiful and best dressed women in the world, and by the manufacturers of Revlon makeup, who named her their main spokesmodel in 1996. In an age of celebrity, when fashion has come to mean as much to the corporate world and consumers as films and television, such accolades have greatly enhanced Berry’s fame, fortune, and clout. Indeed, in 2002 the Wall Street Journal reported that the financially ailing Revlon Company was relying on a line of Halle Berry cosmetics as the primary means of halting its plummeting profits and share price.

Berry’s growing fame and celebrity came at the price of endless media scrutiny. Her 1993 marriage to David Justice, a pitcher for the Atlanta Braves, delighted the tabloids, who printed scores of articles on the glamorous newlyweds, but the couple’s troubled relationship and acrimonious divorce three years later was like manna from heaven for the National Enquirer and the Star. Though she continued to play an increasing variety of film roles, including a drug-addicted mother forced to give up her child to adoption by white parents in Losing Isaiah (1995), Berry’s personal life provided greater publicity than her movies. In February 2000 a judge placed her on three years probation and ordered her to pay $13,500 in fines and perform 200 hours community service for leaving the scene of a traffic accident. Berry enjoyed better press in 2001, when she married singer Eric Benet and became stepmother to his daughter, India.

Her first leading role, as DOROTHY DANDRIDGE in the television drama Introducing Dorothy Dandridge (1999), gave Berry the critical success she had long craved and won her an Emmy Award for outstanding lead actress. As a longtime admirer of Dandridge, Berry co-produced the biopic and lobbied hard to publicize this HBO film about an African American actress renowned for her poise and beauty who suffered from depression and several unhappy and tempestuous relationships. Although Berry never faced the full force of Jim Crow segregation, she strongly identified with Dandridge’s determination to broaden the diversity of roles open to women of color.

The parallel with Dandridge continues with Berry’s performance in Monster’s Ball (2001), when she became the first black woman to win the Academy Award for best actress; in 1955, nearly half a century earlier, Dandridge had been the first African American nominated in that category. Some critics ridiculed the speech in which Berry accepted her award in the name of “every nameless, faceless woman of color that now has a chance because this door tonight has been opened.” They noted that actresses like HATTIE MCDANIEL and Dandridge, let alone thousands of unsung women in the civil rights movement, had already given that door an almighty push. Yet Berry was hardly the first Oscar-winning actress—or actor, for that matter—to be overcome by gushing hyperbole in receiving their profession’s highest award. Others, including the members of the Academy, praised her portrayal of a poor southern black woman struggling to raise a son after the execution of her husband, and her complex relationship with one of his white executioners. In the Nation Michael Eric Dyson, a prominent black academic, lauded Berry’s bravery in using her speech to speak up for “ordinary brothers and sisters.”

Berry’s breakthrough in winning an Academy Award and the sharp criticisms of her acceptance speech capture nicely the ambiguities facing prominent African Americans at the beginning of the twenty-first century. Black American talents and achievements are recognized and rewarded by America’s dominant culture as never before, yet that same culture continues to debate those successes in highly racialized ways.

Dyson, Michael Eric. “Oscar Opens the Door.” The Nation, 15 Apr. 2002.

Farley, Christopher J. Introducing Halle Berry (2002).

Norment, Lynn. “Halle’s Big Year.” Ebony, Nov. 2002.

—STEVEN J. NIVEN

BERRY, LEONIDAS HARRIS

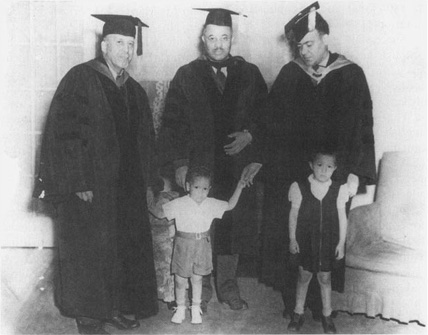

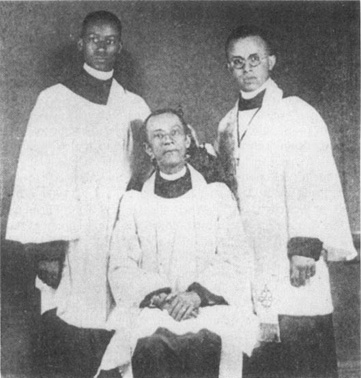

BERRY, LEONIDAS HARRIS(20 July 1902–4 Dec. 1995), physician and public service and church activist, was born on a tobacco farm in Woodsdale, North Carolina, the son of the Reverend Llewellyn Longfellow Berry, general secretary of the Department of Home and Foreign Missions of the African Methodist Episcopal (AME) Church, and Beulah Harris Berry. Leonidas acquired the desire to become a doctor at the age of five, when a distinguished-looking local doctor treated a small wound on his foot. The young boy was impressed by this “miraculous” event. His aspiration to go to medical school intensified while he was attending Booker T. Washington High School in Norfolk, Virginia. In 1924 Berry graduated from Wilberforce University and went on to obtain the SB in 1925 from the University of Chicago. In 1930 he also received his medical degree from the University of Chicago’s Rush Medical College. Berry continued his medical training, earning an MS in Pathology at the University of Illinois Medical School in 1933. He completed his internship at Freedmen’s Hospital (1929–1930), one of the nation’s first black hospitals, and then his residency at Cook County Hospital in Chicago (1931–1935).

For most of his career, Berry resided in Chicago, becoming a nationally and internationally recognized clinician. His practice and research were centered at Chicago’s Provident, Michael Reese, and Cook County Hospitals. From 1935 until 1970 Berry was a mainstay of the physician staff at Provident. This institution, which had been founded by DANIEL HALE WILLIAMS, was one of the nation’s leading black hospitals. In 1946 Berry became the first black physician admitted to the staff at Michael Reese. At Cook County he was the first black internist, rising from assistant to senior attending physician during his long affiliation with this institution (1946–1976). He also served as clinical professor in medicine at the University of Illinois from 1960 until 1975.

Beginning in the 1930s Berry developed into a leader in the emerging specialty of gastroenterology. This branch of medicine focuses on the physiology and pathology of the stomach and intestines as well as their interconnected organs, such as the liver, esophagus, gallbladder, and pancreas. Berry’s clinical accomplishments were at the forefront of his specialty. He became an international authority on digestive diseases and the technique of endoscopy. Berry helped revolutionize his field when he became the first American doctor to employ the fiberoptic gastro-camera to examine the inside of the digestive tract. The use of this instrument became increasingly refined, enabling physicians to diagnose at much earlier stages various diseases, especially cancers, of the gastrointestinal organs. He invented the Eder-Berry gastrobiopsy scope, a device that made it possible to retrieve tissue samples from the stomach for microscopic study. This instrument has been exhibited at the Smithsonian Institution in Washington, D.C.

In addition to his extraordinary clinical achievements, Berry was a superb medical academician. During the course of his career, he authored or co-authored twelve books and eighty-four medical research articles and presented more than 180 medical lectures, exhibitions, and academic papers nationally and internationally. In 1941 Berry presented a research paper before the gastroenterology and proctology section at the American Medical Association’s (AMA) annual convention in Cleveland, Ohio, the first time a black physician made a national presentation before this prestigious group.

The church activities and travels of Berry’s father and mother deeply impressed him throughout his early life—so much so that Berry’s autobiography, I Wouldn’t Take Nothin’ for My Journey (1981), was written primarily as a memoir dedicated to his parents and their lives. Even while achieving his clinical and academic successes, Berry, raised in the swirl of his parents’ church work and community service, never lost touch with the traditional ideals of the black American community—ideals that emphasize charitable work and resistance to racial discrimination. He realized these ideals by expanding his duties and resources at the hospitals and medical schools where he worked, as well as by taking on leadership positions in AME Church and community organizations. From the early 1950s Berry served as president of the mostly black Cook County Physicians Association. He led a citywide movement to set up medical services for young drug addicts and to prevent the spread of drug addiction. His plan involved organizing medical counseling clinics and follow-up services for drug addicts—a plan that became a program that he administered for eight years with finances provided by the Illinois state legislature and the Illinois Department of Public Health.

In 1965 Berry served as president of the National Medical Association (NMA), the nation’s premier organization established for black physicians. The highlight of his tenure was spearheading the NMA’s activities to integrate the AMA. At this time the AMA still maintained segregated local chapters throughout the nation. In addresses to his NMA constituents, Berry described his disdain for this discriminatory barrier faced by black doctors. He called this practice “a senseless social embargo . . . against licensed and practicing physicians based upon a criterion of race in some [AMA] societies and tokenism in others” (Morais, 220). In order to place the NMA on higher ground regarding the integration of physician associations, at the August 1965 annual convention, the association passed Berry’s proposal that the NMA recruit white physicians. At the convention’s press conference, Berry stated his rationale clearly: “We cannot remain a segregated [medical] society when we are pressing for integration ourselves” (Morais, 196).

Under Berry’s leadership the NMA next held a series of formal meetings with AMA officials and trustees. These meetings, which took place between September 1965 and August 1966, resulted in the adoption of several cooperative measures. First, the two organizations agreed to increase recruitment efforts to attract more black Americans into medical careers. Second, the AMA resolved to appoint more black members of the two organizations to high-standing councils and committees of the AMA. Finally, the AMA appointed a special committee of the AMA board of trustees to serve as a watchdog body to work against segregation in local chapters and physician practices. The committee contacted segregated local chapters to persuade them to comply voluntarily with the AMA’s national resolutions prohibiting racial discrimination in local societies, hospitals, and medical care.

Berry also was a deeply committed “churchman” for the AME Church. He strove to use his church ties to work with other denominations on projects for community betterment. For example, for many years Berry served as the medical director of the Health Commission of the AME Church. In this capacity, in the mid-1960s he developed means to support the integration drive in Cairo, Illinois. In response to Ku Klux Klan activities and entrenched neighborhood poverty, local community activists in Cairo launched an antiracism campaign known as the Black United Front. Berry organized a “flying health service to Cairo” called the Flying Black Doctors to assist the Cairo activists. Berry’s group of thirty-two physicians, nurses, and technicians flew down to Cairo and gave medical exams to some three hundred persons. The Cairo activities of the Flying Black Doctors attracted the attention of the national news media, including NBC’s famed television news show, the Huntley Brinkle Report, with Chet Huntley and David Brinkley.

Berry liked to refer to himself as a “multidimensional doctor.” In his autobiography he emphasizes that although he was a successful clinician, he was most pleased that he had never given in to the tendency to become too “circumscribed and perhaps obsessed with the pursuit of excellence in . . . matters purely medical” (405). Berry viewed his medical and public service achievements as much more than solo endeavors. Instead, he believed that they were the direct outgrowth of family and religious influences that stemmed from the slave communities of the pre-Civil War United States. In his autobiography Berry writes: “The success of my career [was] a high water mark in the destiny of the Berry family in its long odyssey through the generations. The strength of Afro-American culture to a great extent lies in the unique common bonds which tie together many [such] successful Black nuclear and multinuclear families in America” (Berry, 407). Berry and his extended family have left a permanent contribution at the highest levels of American and black American medical science and religious life.

The papers of Leonidas H. Berry, 1907–1982, are located in the Modern Manuscripts Collection, History of Medicine Division, National Library of Medicine, Bethesda, Maryland. There is also a body of Berry’s personal papers at the Schomburg Manuscripts and Rare Books Collection, New York Public Library, New York City, under the title Leonidas H. Berry Papers, 1932–1988.

Berry, Leonidas H. I Wouldn’t Take Nothin’ for My Journey: Two Centuries of an Afro-American Minister’s Family (1981).

Morais, H. M. The History of the Negro in Medicine (1968).

Obituary: New York Times (Late Edition), 12 December 1995.

—DAVID MCBRIDE

BETHUNE, MARY JANE McLEOD

BETHUNE, MARY JANE McLEOD(10 July 1875–18 May 1955), organizer of black women and advocate for social justice, was born in Mayesville, South Carolina, the child of the former slaves Samuel McLeod and Patsy McIntosh, farmers. After attending a school operated by the Presbyterian Board of Missions for Freedmen, she entered Scotia Seminary (now Barber-Scotia College) in Concord, North Carolina, in 1888 and graduated in May 1894. She spent the next year at Dwight Moody’s evangelical Institute for Home and Foreign Missions in Chicago, Illinois. In 1898 she married Albertus Bethune. They both taught briefly at Kindell Institute in Sumter, South Carolina. The marriage was not happy. They had one child and separated late in 1907. After teaching in a number of schools, Bethune founded the Daytona Normal and Industrial Institute for Training Negro Girls in Daytona, Florida, in 1904. Twenty years later the school merged with a boys’ school, the Cookman Institute, and was renamed Bethune-Cookman College in 1929. Explaining why she founded the training school, Bethune remarked, “Many homeless girls have been sheltered there and trained physically, mentally and spiritually. They have been helped and sent out to serve, to pass their blessings on to other needy children.”

In addition to her career as an educator, Bethune helped found some of the most significant organizations in black America. In 1920 Bethune became vice president of the National Urban League and helped create the women’s section of its Commission on Interracial Cooperation. From 1924 to 1928 she also served as the president of the National Association of Colored Women. In 1935, as founder and president of the National Council of Negro Women, Bethune forged a coalition of hundreds of black women’s organizations across the country. She served from 1936 to 1950 as president of the Association for the Study of Negro Life and History, later known as the Association for the Study of Afro-American Life and History. In 1935 the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People awarded Bethune its highest honor, the Spingarn Medal. She received honorary degrees from ten universities, the Medal of Honor and Merit from Haiti (1949), and the Star of Africa Award from Liberia (1952). In 1938 she participated along with liberal white southerners in the annual meetings of the Southern Conference for Human Welfare.

Bethune’s involvement in national government began in the 1920s during the Calvin Coolidge and Herbert Hoover presidential administrations, when she participated in child welfare conferences. In June 1936 Bethune became administrative assistant and, in January 1939, director in charge of Negro Affairs in the New Deal National Youth Administration (NYA). This made her the first black woman in U.S. history to occupy such a high-level federal position. Bethune was responsible for helping vast numbers of unemployed sixteen-to twenty-four-year-old black youths find jobs in private industry and in vocational training projects. The agency created work-relief programs that opened opportunities for thousands of black youths, which enabled countless black communities to survive the Depression. She served in this office until the NYA was closed in 1944.

During her service in the Franklin D. Roosevelt administration, Bethune organized a small but influential group of black officials who became known as the Black Cabinet. Prominent among them were WILLIAM HENRY HASTIE of the Department of the Interior and the War Department and ROBERT WEAVER, who served in the Department of the Interior and several manpower agencies. The Black Cabinet did more than advise the president; they articulated a black agenda for social change, beginning with demands for greater benefit from New Deal programs and equal employment opportunities.

In 1937 in Washington, D.C., Bethune orchestrated the National Conference on the Problems of the Negro and Negro Youth, which focused on concerns ranging from better housing and health care for African Americans to equal protection under the law. As an outspoken advocate for black civil rights, she fought for federal anti-poll tax and anti-lynching legislation. Bethune’s influence during the New Deal was further strengthened by her friendship with First Lady Eleanor Roosevelt.

During World War II, Bethune was special assistant to the secretary of war and assistant director of the Women’s Army Corps. In this post she set up the first officer candidate schools for the corps. Throughout the war she pressed President Roosevelt and other governmental and military officials to make use of the many black women eager to serve in the national defense program; she also lobbied for increased appointments of black women to federal bureaus. After the war she continued to lecture and to write newspaper and magazine columns and articles until her death in Daytona Beach, Florida.

Urged by the National Council of Negro Women, the federal government dedicated the Mary McLeod Bethune Memorial Statue at Lincoln Park in southeastern Washington, D.C., on 10 July 1974. Bethune’s life and work provide one of the major links between the social reform efforts of post-Reconstruction black women and the political protest activities of the generation emerging after World War II. The many strands of black women’s struggle for education, political rights, racial pride, sexual autonomy, and liberation are united in the writings, speeches, and organization work of Bethune.

Holt, Rackman. Mary McLeod Bethune: A Biography (1964).

Ross, B. Joyce. “Mary McLeod Bethune and the National Youth Administration: A Case Study of Power Relationships in the Black Cabinet of Franklin D. Roosevelt.” Journal of Negro History 60 (Jan. 1975): 1–28.

Smith, Elaine M. “Mary McLeod Bethune and the National Youth Administration” in Clio Was a Woman: Studies in the History of American Women (1980).

Obituary: New York Times, 19 May 1955.

—DARLENE CLARK HINE

BETHUNE, THOMAS.

BETHUNE, THOMAS.See Blind Tom.

BIBB, HENRY WALTON

BIBB, HENRY WALTON(10 May 1815–1854), author, editor, and antislavery lecturer, was born into slavery on the plantation of David White of Shelby County, Kentucky, the son of James Bibb, a slaveholding planter and state senator, and Mildred Jackson. White began hiring Bibb out as a laborer on several neighboring plantations before he had reached the age of ten. The constant change in living situations throughout his childhood, combined with the inhumane treatment he often received at the hands of strangers, set a pattern for life that he would later refer to in his autobiography as “my manner of living on the road.” Bibb was sold more than six times between 1832 and 1840 and was forced to relocate to at least seven states throughout the South; later, as a free man, his campaign for abolition took him throughout eastern Canada and the northern United States. But such early instability also made the young Bibb both self-sufficient and resourceful, two characteristics that were useful against the day-to-day assault of slavery: “The only weapon of self defense that I could use successfully,” he wrote, “was that of deception.”

In 1833 Bibb met and married Malinda, a slave on William Gatewood’s plantation in nearby Oldham County, Kentucky, and the following year she gave birth to Mary Frances, their only child to survive infancy. At about this time Gatewood purchased Bibb from the Whites in the vain hope that uniting the young family would pacify their desire for freedom. Living less than ten miles from the Ohio River, Bibb made his first escape from slavery by crossing the river into Madison, Indiana, in the winter of 1837. He boarded a steamboat bound for Cincinnati, escaping the notice of authorities because he was “so near the color of a slaveholder,” a trait deemed undesirable by prospective slave buyers and for which he endured prolonged incarcerations at various slave markets. Bibb situated this first escape historically as “the commencement of what was called the underground railroad to Canada.” Less than a year after achieving freedom, Bibb returned to Kentucky for his wife and daughter. He was captured and taken to the Louisville slave market, from which he again escaped, returning to Perrysburg, Ohio.

In July 1839 Bibb once more undertook to free his wife and child. Betrayed by another slave, Bibb was again taken to Louisville for sale; this time his wife and child accompanied him on the auction block. While awaiting sale, Bibb received the rudiments of an education from white felons in the prison, where he was forced to work at hard labor for a summer. Finally, a speculator purchased the Bibbs for resale at the lucrative markets of New Orleans. After being bought by Deacon Francis Whitfield of Claiborn Parish, Louisiana, Bibb and his family suffered unimaginable cruelty. They were physically beaten and literally overworked to the point of death, and they nearly perished for lack of food and adequate shelter. Bibb attempted two escapes from Whitfield, preferring that his family risk the perils of the surrounding Red River swamps than endure eighteen-hour days in the cotton fields.

The final escape attempt resulted in Bibb’s permanent separation from his family in December 1840. First staked down and beaten nearly to death after his capture, Bibb was then sold to two professional gamblers. These men took him through Texas and Arkansas and into “Indian Territory,” where they sold him to a Cherokee slave owner on the frontier of white settlement in what is probably present-day Oklahoma or southeastern Kansas. There Bibb received what he considered his only humane treatment in slavery. Because he was allotted a modicum of independence and respect, and because he was reluctant to desert his master, who was then terminally ill, Bibb delayed his final escape from slavery by a year, departing the night of his master’s death. He traveled through wilderness, occasionally stumbling onto Indian encampments, before crossing into Missouri, where his route took him east along the Osage River into Jefferson City. From there he traveled by steamboat through St. Louis to Cincinnati and on to freedom in 1841.

In Detroit in the winter of 1842, Bibb briefly attended the school of the Reverend William C. Monroe, receiving his only formal education. Bibb’s work as what he called an “advocate of liberty” began in earnest soon after his final escape from slavery; for the next decade he epitomized the black abolitionist, making his voice heard through lectures, a slave narrative, and the independent press. Like his contemporaries FREDERICK DOUGLASS, WILLIAM WELLS BROWN, and WILLIAM and ELLEN CRAFT, Bibb was among a first generation of African American fugitives from the South who used their firsthand experience in slavery as a compelling testimony against the atrocities of the southern institution.

Although his highly regarded Narrative of the Life and Adventures of Henry Bibb, An American Slave was not published until the spring of 1849, Bibb began telling the story of his life before antislavery crowds in Adrian, Michigan, in May 1844. His story proved so poignant in its depiction of human suffering and endurance, so heroic in its accounts of ingenious escapes, and so romantic in its adventures in the territories of the West that the Detroit Liberty Association undertook a full-scale investigation to allay public incredulity, an unprecedented response to a nineteenth-century slave narrative. Through correspondence with Bibb’s former associates, “slave owners, slave dealers, fugitives from slavery, political friends and political foes,” the committee found the facts of Bibb’s account “corroborated beyond all question.”

Lecturing for the Michigan Liberty Party, Bibb was sent to Ohio to speak along the north side of the Mason-Dixon Line, a region notorious for its proslavery sympathies. Bibb returned to the South one final time in the winter of 1845 in search of his wife and daughter. While visiting his mother in Kentucky, Bibb learned that his wife and daughter’s escape from certain death on Whitfield’s plantation came at the expense of their marriage; Malinda had been forced to become the mistress of a white southerner. In 1848, on a sabbatical from lecturing, Bibb met and married Mary E. Miles, an African American abolitionist from Boston. It is not known whether they had children. With the passage of the 1850 Fugitive Slave Law, the Bibbs fled to Sandwich, western Canada, where, in January 1851, Henry and Mary established the Voice of the Fugitive. This publication was a biweekly antislavery journal that reported on the condition of fugitives and advocated the abolition of slavery, black colonization to Canada, temperance, black education, and the development of black commercial enterprises.

With the aid of the black abolitionists JAMES T. HOLLY and J. T. Fisher, Bibb organized the North American League, an organization evolving out of the North American Convention of Colored People, held in Toronto and over which Bibb presided in September 1851. The league was meant to promote colonization to Canada and to serve as the central authority for blacks in the Americas. Although the league survived but a few short months, Bibb continued to work toward colonization, encouraging Michigan philanthropists a year later to help form the Refugee Home Society—a joint-stock company for the purpose of acquiring and selling Canadian farmland to black emigrants—to which Bibb attached his journal as its official organ. Tension among prominent black Canadians, however, brought about the society’s demise. Bibb died in Windsor, Ontario, Canada, without realizing his vision for an African American colony.

Andrews, William L. To Tell a Free Story: The First Century of Afro-American Autobiography, 1760–1865 (1988).

Hite, Roger W. “Voice of a Fugitive: Henry Bibb and Ante-bellum Black Separatism.” Journal of Black Studies 4 (Mar. 1974): 269–284.

QUARLES, BENJAMIN. Black Abolitionists (1969).

Ripley, C. Peter, ed. The Black Abolitionist Papers, vols. 3–4 (1985, 1991).

Silverman, Jason H. Unwelcome Guests: Canada West’s Response to American Fugitive Slaves, 1800–1865 (1985).

—GREGORY S. JACKSON

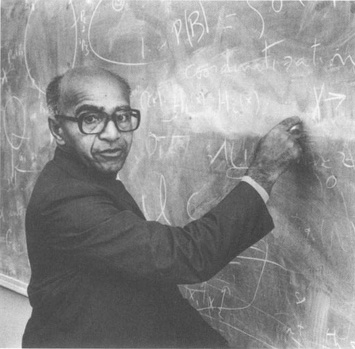

BLACKWELL, DAVID

BLACKWELL, DAVID(24 Apr. 1919–), mathematician and professor, was born David Harold Blackwell in Centralia, Illinois, the oldest of four children, to Grover Blackwell, a locomotive mechanic for the Illinois Central Railroad, and Mabel Johnson. Although much of Blackwell’s hometown was segregated, he attended an integrated elementary school. He first became interested in mathematics in high school where, although not particularly interested in algebra or trigonometry, he immediately took an interest in geometry—the scientific study of the properties and relations of lines, surfaces, and solids in space. Later in his life Blackwell credited his high school geometry instructor for showing him the beauty and the usefulness of mathematics. He joined his high school’s mathematics club where his instructor pushed students to submit solutions to the School Science and Mathematics Journal, which published one of Blackwell’s solutions. It was with geometry that Blackwell first began to apply mathematical methods and formulas to games such as “crosses” in order to determine the probability of winning for the first player.

When Blackwell entered college at the age of sixteen, he intended at first to become an elementary school teacher. In 1938 he earned an AB degree from the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign and went on to receive an AM in 1939 and a PhD in 1941. Here, his interest in probability and statistics emerged and flourished. His dissertation, written under the direction of Joseph L. Doob, was entitled “Some Properties of Markoff Chains.” When he completed the PhD, Blackwell was only twenty-two years old and was only the seventh African American to receive a PhD in Mathematics.

David Blackwell, an innovator in statistical analysis, game theory, and mathematical decision-making. Schomburg Center

After completing the PhD, Blackwell accepted a Rosenwald Postdoctoral Fellowship at the Institute for Advanced Study in Princeton, prompting outrage from some in the university community who vehemently opposed the appointment of an African American to this position at Princeton, which had not yet even enrolled African American students. The University’s president, Harold D. Dodds, admonished the institute for making such an appointment against the wishes of the university community and sought unsuccessfully to block Blackwell’s appointment.

Perhaps because of his experience in the Ivy League, Blackwell seemed to be aware of the limited opportunities for African American scholars in higher academia, and with the exception of an application and interview at the University of California at Berkeley, he applied for faculty positions at only historically black colleges and universities. After one year at Princeton he took short-term professorships at Southern University in Baton Rouge, Louisiana, and Clark Atlanta University.

In 1944 Blackwell joined the faculty of Howard University as an assistant professor at a time when the Washington, D.C., institution was a mecca for black scholars, including the historian RAYFORD W. LOGAN, the philosopher ALAIN LOCKE, and the sociologist E. FRANKLIN FRAZIER. Shortly after arriving at Howard, Blackwell married Ann Madison, and in just three years he had risen to the rank of full professor and chairman of the mathematics department.

At Howard, Blackwell also launched his career as a widely recognized and honored researcher in mathematics. Hearing a lecture and attending a subsequent meeting with the well-known statistician Abe Girshick stimulated Blackwell’s interest in statistics and sequential analysis. Even while teaching and chairing the Department of Mathematics at Howard, Blackwell published over twenty research papers in mathematical statistics. Between 1948 and 1950 his interest in the theory of games—the method of applying logic to determine which of several available strategies is likely to maximize one’s gain or minimize one’s loss in a game or military solution—was revived by three summers of work at the Rand Corporation. Blackwell became particularly interested in the art of dueling with pistols and in determining the most statistically advantageous moment for a dueler to shoot. In the midst of the cold war, such statistical analyses of games became useful and pertinent for the federal government in thinking about U.S. military strategy, and Blackwell’s work and Blackwell himself became a leader in the field of statistical analysis and game theory. In 1950–1951 Blackwell spent one year as a visiting professor of statistics at Stanford University.

All of Blackwell’s work in game theory (including the art of dueling and the statistical analysis of bluffing as a strategy in poker) culminated in 1954 when he and Abe Girshick jointly wrote Theory of Games and Statistical Decisions. This book served as a mathematical textbook for students in statistical decision functions. Building upon the prior works of John von Neumann and A. Wald in the statistical and conceptual aspects of decision theory and theory of games, Blackwell and Girshick developed new and innovative concepts of mathematical decision making that were later used in military tactics, the business world, and engineering.

By the time of the book’s publication in 1954, Blackwell’s career was rising rapidly. Shortly after he gave an address on concepts of probability at the International Congress of Mathematicians in Amsterdam, he was offered and accepted a position as professor of statistics at the University of California at Berkeley. Serving as chair of the Berkeley statistics department from 1957 to 1961, Blackwell continued to be a prolific academic writer, publishing over fifty articles in the field of statistical analysis. Prominent appointments and accolades soon followed. In 1955 he was elected president of the Institute of Mathematical Statistics, and later served as president for the International Association for Statistics in Physical Sciences and the Bernoulli Society, and vice-president of the International Statistical Institute, the American Statistical Association, and the American Mathematical Society.

In 1965 Blackwell became the first African American named to the National Academy of Sciences (NAS), a body used by the federal government and other agencies to investigate, experiment, and report on scientific matters. (Remarkably, nearly three decades later in 1996, The Journal of Blacks in Higher Education found that Blackwell had been joined by only two further black inductees at the NAS, the chemist PERCY LAVON JULIAN and the sociologist WILLIAM JULIUS WILSON). In 1979 Blackwell received the prestigious von Neumann Theory Prize from the Operations Research Society of America for his work in dynamic programming, and in 1986 Blackwell received the R.A. Fisher Award from the Committee of Presidents of Statistical Societies. All of these awards and prizes acknowledged the continued relevance of his research in statistical analysis and game theory. In addition to being known as one of the world’s best mathematicians, his scholarly work and professional activities have brought Blackwell honorary degrees from Howard, Harvard, Yale, the University of Illinois, Carnegie-Mellon, the University of Southern California, Michigan State, Syracuse, Southern Illinois University, the University of Warwick in England, and the National University of Lesotho. Blackwell retired from Berkeley in 1989, although he remains on the faculty as professor emeritus and continues to publish in mathematical journals. Blackwell has also advised over fifty graduate students. Blackwell’s legacy in teaching and researching, and the path-breaking trail he made for African Americans in the mathematics field, makes him one of this century’s most notable figures in this highly specialized area.

Blackwell, David, et al. Theory of Games and Statistical Decisions (1954).

DeGroot, Morris H. “A Conversation with David Blackwell.” Statistical Science, Feb. 1986: 40–53.

Guillen, Michael. “Normal, against the Odds.” New York Times, 30 June 1985.

Martin, Donald A. “The Determinacy of Blackwell Games.” Journal of Symbolic Logic, Dec. 1998: 1565–1581.

“The Mathematics of Poker Strategy.” New York Times, 25 Dec. 1949.

“National Academy of Sciences: Nearly as White as a Posh Country Club in Alabama.” Journal of Blacks in Higher Education (Summer 1996): 18–19.

—KEITH WAILOO

—RICHARD MIZELLE

BLACKWELL, UNITA Z.

BLACKWELL, UNITA Z.(18 Mar. 1933–), civil rights activist and mayor, was born in Lula, Mississippi, the daughter of sharecroppers in Coahoma County, Mississippi. Her father had to leave Mississippi when he refused to obey his plantation owner’s order to send his young daughter Unita to the fields to pick cotton. He found work in an icehouse in a neighboring state. Her mother was illiterate and determined that her children would learn to read and write. In the Mississippi Delta, everyone was required to pick and chop cotton, and the schools closed down to allow for this work except for two or three months a year. Consequently, Unita Blackwell and her sister took the ferry across the Mississippi River to West Helena, Arkansas. She lived with her aunt for eight months of the year and attended Westside Junior High School, where she completed the eighth grade. Later, she received her high school equivalency diploma. Blackwell spent her younger years picking cotton—as much as three hundred bales a day. After she married, she and her husband went to Florida to pick tomatoes and work in a canning plant. She moved to Mayersville, Mississippi, in 1962 and picked cotton, while her husband worked for U.S. industries.

In 1964 she became a field worker for the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee under the supervision of STOKELY CARMICHAEL. She was in charge of voter registration in the Second Congressional District in Mississippi, and, along with seven other people, she registered to vote in Issaquena County. She became a close friend of FANNIE LOU HAMER, and they both became founding members of the Mississippi Freedom Democratic Party (MFDP), formed in 1964 to challenge the white supremacist Democratic Party in Mississippi. Along with Hamer, Blackwell was an MFDP delegate to the 1964 Democratic national convention in Atlantic City. Members of the MFDP challenged the seating of the all-white delegates from Mississippi, and Blackwell, Hamer, and others testified before the credentials committee. When Hamer presented her famous testimony before the committee, President Lyndon Johnson called a press conference to prevent television coverage of the powerful and inspirational speaker from Mississippi. After much political wrangling, the MFDP was awarded only two delegate seats, which the members refused.

In the summer of 1965 the MFDP marched on the state legislature in Jackson to support Governor Paul Johnson’s request that the legislators repeal Mississippi’s discriminatory voting laws. Over half of the five hundred demonstrators were in their teens. Police arrested more than two hundred of the marchers, including Blackwell, placing them in the stockyards of the state fairgrounds, where many of the women were tortured. Blackwell herself was imprisoned for eleven days (USM oral history interview, 35–36).

Blackwell continued to press for change in the Delta. In 1965 she demanded that the school board provide decent facilities, teachers, and books for her son’s school. The board refused to hear the demands, and Blackwell sued for desegregation of the schools in Sharkey and Issaquena County Consolidated Line v. Blackwell. The black principal followed the orders of the school board and refused to cooperate and, in Blackwell’s view, left them with no alternative but to sue. “Desegregation of school was not one [of] our favorites” she recalled. “Our thing was to have good schools, didn’t care what color they were. . . . We was asking for books; we was asking for fixing of the schools, that they would be just as nice” (University of Southern Mississippi oral history interview, 44). She won her case.

Undaunted by intimidation, Blackwell continued her struggle for justice. In the winter of 1965 and 1966 poor people in the Delta were hungry and cold. Indeed, two people froze to death. Conditions were made worse when planters evicted sharecroppers for registering to vote and participating in civil rights activities; the planters then saw to it that officials denied the evicted sharecroppers access to the federal food commodity program. With no food to eat and no place to live, sharecroppers formed the Mississippi Freedom Labor Union in January of 1965. The union launched a strike, and domestic workers, tractor drivers, and field hands walked off of their jobs all over the Delta.

As evictions and starvation continued, the union members Blackwell, Ida Mae Lawrence, and Isaac Foster, in the face of the federal government’s refusal to answer their plea for help, decided to set up their own community and government. They led over seventy men, women, and children onto the empty Greenville Air Base, consisting of two thousand acres and three hundred buildings. There Blackwell eloquently expressed the goals of the group: “I feel that the federal government have proven that it don’t care about poor people. Everything that we have asked for through these years has been handed down on paper. It’s never been a reality. We the poor people of Mississippi is tired,” she continued. “We’re going to build for ourselves, because we don’t have a government that represents us” (Grant, 501). A group of Air Police removed the squatters after thirty hours, but Blackwell and others had forced national attention on the dire poverty that many lived in and the limits of federal programs to address poor peoples’ concerns.

Blackwell continued her efforts on behalf of poor people, becoming a national spokesperson on the issues of community economic development and low-income housing. In 1967, along with Hamer, Annie Devine, and Amzie Moore, she helped organize the Mississippi Action for Community Education Inc. (MACE) “to build and strengthen local human capacities and indigenous community development efforts” in the Mississippi Delta. MACE has trained local community organizers and leaders; conducts literacy, job training, career development, and arts education programs; and sponsors the Mississippi Delta Blues and Heritage Festival. In the late 1960s and early 1970s Blackwell worked with the National Council of Negro Women as a community-development specialist, establishing cooperative ventures in ownership of low-income housing. In 1983 she received a master’s degree in Regional Planning from the University of Massachusetts at Amherst.

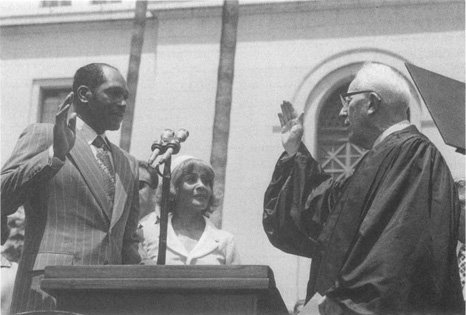

Blackwell has remained politically active on both a local and a national level. In 1976 she was elected mayor of Mayersville, becoming the first African American to hold mayoral office in Mississippi. In 1979 she attended President Jimmy Carter’s Energy Summit at Camp David, and in 1984 she addressed the National Democratic Convention in San Francisco. In 1989 she chaired the National Mayor’s Conference and, in 1991, the Black Women’s Mayor’s Conference. From 1976 to 1983 she was president of the U.S.-China Peoples’ Friendship Association and traveled to China on numerous occasions. She has traveled extensively throughout Asia, Central America, and Europe.

In recognition of her achievements, in 1992 Blackwell was awarded the prized MacArthur Fellowship, also called the “genius” award, and the University of Massachusetts invited her to become the Eleanor Bateman Alumni Scholar. Her fighting spirit and faith in humanity persists. In 2000 she observed: “It seems like the whole century has been about overcoming. Fighting and then overcoming. You had women’s suffrage, and apartheid and segregation. And we blacks lived in that lock-in, and somehow survived. How, I do not know. Nothing but a God I say. The whole era was full of hate, but we’re trying to overcome it, and we’re headed for something new, I just feel it. Maybe we are the group of people, the blacks in America, that brought everyone to their worst, and then to their best. Including ourselves” (UMASS Online Magazine).

The most extensive source of information on Mrs. Blackwell is her interview, located in the Civil Rights in Mississippi Digital Archive, McCain Library and Archives, University of Southern Mississippi. See also the Mississippi Action for Community Education Inc. web site, and UMASS Online Magazine (Winter 2000).

“My Whole World Was My Kinfolks.” UMASS Online Magazine, Winter 2000.

“Mississippi Freedom Labor Union, 1965 Origins,” and “We Have No Government,” in Jo Ann Grant, ed. Black Protest: History, Documents, and Analyses, 1619 to the Present, 498–505.

Dittmer, John. Local People: The Struggle for Civil Rights in Mississippi (1994).

Mills, Kay. This Little Light of Mine: The Life of Fannie Lou Homer (1993).

Payne, Charles. I’ve Got the Light of Freedom: The Organizing Tradition and the Mississippi Freedom Struggle (1995).

—NAN ELIZABETH WOODRUFF

BLAKE, EUBIE

BLAKE, EUBIE(7 Feb. 1883–12 Feb. 1983), composer and pianist, was born James Hubert Blake in Baltimore, Maryland, the son of John Sumner Blake, a stevedore, and Emily Johnston, a launderer. His father was a Civil War veteran, and both parents were former slaves. While the young Blake was a mediocre student during several years of public schooling, he showed early signs of musical interest and talent, picking out tunes on an organ in a department store at about age six. As a result, his parents rented an organ for twenty-five cents a week, and he soon began basic keyboard lessons with Margaret Marshall, a neighbor and church organist. At about age twelve he learned cornet and buck dancing and was earning pocket change singing with friends on the street. When he was thirteen, he received encouragement from the ragtime pianist Jesse Pickett, whom he had watched through the window of a bawdy house in order to learn his fingering. By 1898 he had steady work as a piano player in Aggie Shelton’s sporting house, a job that necessitated the lad’s sneaking out of his home at night, after his parents went to bed. The objections of his deeply religious mother when she learned of his new career were overcome only by the pragmatism of his sporadically employed father, once he discovered how much his son was making in tips.

In 1899 (the year SCOTT JOPLIN’s famous “Maple Leaf Rag” appeared), Blake wrote his first rag, “Charleston Rag” (although he would not be able to notate it until some years later). In 1902 he performed as a buck dancer in the traveling minstrel show In Old Kentucky, playing briefly in New York City. In 1907, after playing in several clubs in Baltimore, he became a pianist at the Goldfield Hotel, built by his friend and the new world lightweight boxing champion Joe Gans. The elegant Goldfield was one of the first establishments in Baltimore where blacks and whites mixed, and there Blake acquired a personal grace and polish that would impress his admirers for the rest of his life. Already an excellent player, he learned from watching the conservatory-trained “One-Leg Willie” Joseph, whom he often cited as the best piano player he had ever heard. While at the Goldfield, Blake studied composition with the Baltimore musician Llewellyn Wilson, and at about the same time he began playing summers in Atlantic City, where he met such keyboard luminaries as Willie “the Lion” Smith, Luckey Roberts, and James P. Johnson. In July 1910 he married Avis Lee, the daughter of a black society family in Baltimore and a classically trained pianist.

In 1915 Blake met the singer and lyricist NOBLE SISSLE, and they quickly began a songwriting collaboration that would last for decades. One of their songs of that year, “It’s All Your Fault,” achieved success when it was introduced by Sophie Tucker. Sissle and Blake also performed in New York with JAMES REESE EUROPE’s Society Orchestra. While Sissle and Europe were in the service during World War I, Blake performed in vaudeville with Henry “Broadway” Jones. After the war Sissle and Blake formed a vaudeville act called the Dixie Duo, which became quite successful. In an era when blacks were expected to shuffle and speak in dialect, they dressed elegantly in tuxedos, and they were one of the first black acts to perform before white audiences without burnt cork. By 1917 Blake also had begun recording on both discs and piano rolls.

In 1920 Sissle and Blake met the successful comedy and dance team of Flournoy Miller and Aubrey Lyles, who suggested combining forces to produce a show. The result was the all-black Shuffle Along, which opened on Broadway in 1921 and for which Blake was composer and conductor. The score included what would become one of his best-known songs, “I’m Just Wild about Harry.” Mounted on a shoestring budget, the musical met with critical acclaim and popular success, running for 504 performances in New York, followed by an extensive three-company tour of the United States. The show had a tremendous effect on musical theater, stirring interest in jazz dance, fostering faster paced shows with more syncopated rhythms, and paving the way in general for more black musicals and black performers. Shuffle Along was a springboard for the careers of several of its cast members, including JOSEPHINE BAKER, Adelaide Hall, FLORENCE MILLS, and PAUL ROBESON.

Sissle and Blake worked for ten years as songwriters for the prestigious Witmark publishing firm. In 1922, through Julius Witmark, they were able to join ASCAP (American Society of Composers, Authors, and Publishers), which did not at that time include many blacks. They also appeared in an early sound film in 1923, Sissle and Blake’s Snappy Songs, produced by the electronics pioneer Lee De Forest. In 1924 they created an ambitious new show, The Chocolate Dandies. Unable to match the success of Shuffle Along, the lavish production lost money, but Blake was proud of its score and considered it his best.

The team returned to vaudeville, ending their long collaboration with a successful eight-month tour of Great Britain in 1925–1926. The two broke up when Sissle, attracted by opportunities in Europe, returned to work there; Blake, delighted to be back home in New York, refused to accompany him. Over the next few years Blake collaborated with Harry Creamer to produce a few songs and shows; reunited with “Broadway” Jones to perform the shortened “tab show” Shuffle Along Jr. in vaudeville (1928–1929); and teamed with the lyricist Andy Razaf to write songs for Lew Leslie’s Blackbirds of 1930, including “Memories of You,” later popularized by Benny Goodman. After Lyles’s death in 1932, Sissle and Blake reunited with Miller to create Shuffle Along of 1933, but the show failed, in part because of the Depression. The remainder of the decade saw Blake collaborating with the lyricist Milton Reddie on a series of shows, including the Works Progress Administration-produced Swing It in 1937, and with Razaf on several floor shows and “industrials” (promotional shows). Blake’s wife died of tuberculosis in 1939, but despite his grief he managed to complete, with Razaf, the show Tan Manhattan.

During World War II, Blake toured with United Service Organizations shows and worked with other collaborators. In 1945 he married Marion Gant Tyler, a business executive and former showgirl in several black musicals. She took over management of his financial affairs and saw to the raising of his ASCAP rating to an appropriate level, enhancing their financial security considerably.

After the war, at the age of sixty-three, Blake took the opportunity to attend New York University, where he studied the Schillinger system of composition. He graduated with a degree in music in 1950. Meanwhile, the presidential race of 1948 stirred renewed interest in “I’m Just Wild about Harry” when Harry Truman adopted it as a campaign song. This resulted in a reuniting of Sissle and Blake and in a revival in 1952 of Shuffle Along. Unfortunately, the producers’ attempts to completely rewrite the show had the effect of eviscerating it, and the restaging closed after only four performances.

Following a few years of relative retirement, during which Blake wrote out some of his earlier pieces, a resurgence of popular interest in ragtime in the 1950s and again in the 1970s thrust him back into the spotlight for the last decades of his life. Several commemorative recordings appeared, most notably, The Eighty-six Years of Eubie Blake, a two-record retrospective with Noble Sissle for Columbia in 1969. In 1972 he started Eubie Blake Music, a record company featuring his own music. He was much in demand as a speaker and performer, impressing audiences with his still considerable pianistic technique as well as his energy, audience rapport, and charm as a raconteur. Appearances included the St. Louis Ragfest, the Newport Jazz Festival, the Tonight Show, a solo concert at Town Hall in New York City, and a concert in his honor by Arthur Fiedler and the Boston Pops in 1973, with Blake as soloist. In 1974 Jean-Cristophe Averty produced a four-hour documentary film on Blake’s life and music for French television. The musical revue Eubie!, featuring twenty-three of his numbers, opened on Broadway in 1978 and ran for a year. Blake was awarded the Presidential Medal of Freedom at the White House in 1981.

Blake’s wife, Marion, died in June 1982; he left no children by either of his marriages. A few months after his wife’s death, his hundredth birthday was feted with performances of his music, but he was ill with pneumonia and unable to attend. He died five days later in New York City.

Over a long career as pianist, composer, and conductor, Blake left a legacy of more than two thousand compositions in various styles. His earliest pieces were piano rags, often of such extreme difficulty that they were simplified for publication. As a ragtime composer and player, he, along with such figures as Luckey Roberts and James P. Johnson, was a key influence on the Harlem stridepiano school of the 1930s. In the field of show music, Blake moved beyond the confines of ragtime, producing songs that combined rhythmic energy with an appealing lyricism. Particularly notable was his involvement with the successful Shuffle Along, which put blacks back on the Broadway stage after an absence of more than ten years. Over his lifetime he displayed a marked openness to musical growth, learning from “all music, particularly the music of Mozart, Chopin, Tchaikovsky, Victor Herbert, Gershwin, Debussy, and Strauss,” and, indeed, some of his less well known pieces show these influences. Finally, his role in later years as an energetic “elder statesman of ragtime” provided a historical link to a time long gone as well as inspiration to many younger fans.

Blake’s papers are at the Maryland Historical Society in Baltimore.

Jasen, David A., and Trebor Jay Tichenor. Rags and Ragtime: A Musical History (1978).

Kimball, Robert, and William Bolcom. Reminiscing with Sissle and Blake (1973).

Rose, Al. Eubie Blake (1979).

Southern, Eileen. The Music of Black Americans: A History (1971; 2nd ed., 1983).

—WILLIAM G. ELLIOTT

BLAKEY, ART

BLAKEY, ART(11 Oct. 1919–16 Oct. 1990), jazz drummer and bandleader, was born Art William Blakey in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, the son of Burtrum Blakey, a barber, and Marie Roddericker. His father left home shortly after Blakey was born, and his mother died the next year. Consequently, he was raised by a cousin, Sarah Oliver Parran, who worked at the Jones and Laughlin Steel Mill in Pittsburgh. He moved out of the home at age thirteen to work in the steel mills and in 1938 married Clarice Stuart, the first of three wives. His other wives were Diana Bates and Ann Arnold. Blakey had at least ten children (the exact number is unknown), the last of whom was born in 1986.

As a teenager Blakey taught himself to play the piano and performed in local dance bands, but he later switched to drums. Like many of his contemporaries, Blakey initially adapted the stylistic drumming techniques of well-known swing era drummers, including Chick Webb, Sid Catlett, and Ray Bauduc, to whom he frequently paid tribute. As a result, his earliest playing experiences away from Pittsburgh centered around ensembles fronted by well-known, big-band leaders.

Although some sources indicate Blakey first worked with the Fletcher Henderson Orchestra in 1939, it seems unlikely. Drummer Pete Suggs joined the Henderson band in June 1937 and remained with him until the group disbanded two years later, when Henderson became an arranger and pianist for the Benny Goodman band. However, Blakey did join a newly formed Henderson band in the spring of 1943 after playing with Mary Lou Williams’s twelve-piece band and briefly leading his own group at a small Boston nightclub in 1942.

During the early 1940s Blakey was assimilating the innovative bop drumming styles of Kenny Clarke and Max Roach, as evidenced by his selection as drummer for the Billy Eckstine big band organized in 1944. This group (with trumpeter DIZZY GILLESPIE as musical director) started at the Club Plantation in St. Louis and was among the first big bands to play bebop-influenced arrangements. Although somewhat unsuccessful as a commercial venture, the band rehearsed and recorded from 1944 to 1947. Blakey’s playing with this ensemble indicates that regardless of the bebop bent of the repertoire, he played mainly late, swing-style drums. But it was during his tenure with Eckstine that Blakey came in contact with several major bop luminaries, including Gillespie, CHARLIE PARKER, MILES DAVIS, Dexter Gordon, and Kenny Dorham. His association with these musicians placed him firmly in the bop camp, where he remained throughout his career. After the dissolution of Eckstine’s band, Blakey joined THELONIOUS MONK for the pianist’s first Blue Note recordings in 1947; theirs was a complementary collaboration that continued off and on for the next decade. That same year Blakey organized a rehearsal band, the Seventeen Messengers, and in December made several recordings for Blue Note with his octet, Art Blakey’s Jazz Messengers, which included Dorham on trumpet. This group was the first to bear the name through which Blakey would later become famous.

In 1948 Blakey made a brief, nonmusical trip to Africa, at which time he converted to the Islamic religion, changing his name to Abdullah Ibn Buhaina. By mid-1948 he had returned to the United States, recording once again with Monk that July and with saxophonist James Moody in October. The next year he joined Lucky Millinder’s R&B–based band and recorded with him in February. Although Blakey never recorded under his Muslim name, several of his children share this name with him, and later he was known to his musical friends as “Bu.”

During the early 1950s Blakey solidified his bop drumming style by playing with well-known bop musicians such as Parker, Davis, Buddy DeFranco, Clifford Brown, Percy Heath, and Horace Silver. In the mid-1950s Blakey and Silver formed the first of the acclaimed Jazz Messengers ensembles that initially included Dorham, Hank Mobley, and Doug Watkins. When Silver left in 1956, Blakey retained leadership of the group that with constantly changing personnel became an important conduit through which many young, talented jazz musicians would pass. For the next twenty-odd years the Jazz Messengers’s alumni comprised a list of virtual “who’s who” in modern jazz, including Donald Byrd, Bill Hardman, Jackie McLean, Junior Mance, Lee Morgan, Benny Golson, Bobby Timmons, Mobley, Wayne Shorter, Curtis Fuller, Freddie Hubbard, Cedar Walton, Reggie Workman, Keith Jarrett, Chuck Mangione, McCoy Tyner, Woody Shaw, Joanne Brackeen, Steve Turré, WYNTON MARSALIS, and Branford Marsalis.

Despite impaired hearing, which ultimately left him deaf, Blakey continued to perform with the Jazz Messengers until shortly before his death in New York City. Throughout his dynamic and influential career he worked with nearly every major bop figure of the last half of the twentieth century, and his Jazz Messengers ensembles provided a training ground for dozens more. He was inducted into the Down Beat Jazz Hall of Fame in 1981, and the Jazz Messengers received a Grammy Award for Best Jazz Instrumental Group Performance in 1984. The group recorded several film soundtracks (mainly overseas) from 1959 to 1972, and a documentary film, Art Blakey: The Jazz Messenger (Rhapsody Films), containing interviews with Blakey and other musicians as well as performances by the Jazz Messengers, was released in 1988. Blakey also appears in a jazz video series produced by Sony called Art Blakey and the Jazz Messengers: Jazz at the Smithsonian (1982).

Blakey’s recorded legacy spans forty years and documents his prodigious and prolific career as drummer and leader. His earliest big-band recordings with Eckstine (De Luxe 2001, 1944) demonstrate an advanced swing style comparable to the best of the late swing era drummers. Although his early Monk recordings (The Complete Blue Note Recordings of Thelonious Monk, Mosaic MR4–101) are clearly bop-oriented, he retains some of his earlier swing characteristics. By the beginning of the 1950s, however, several of Blakey’s well-defined playing characteristics emerge, including his heavy and constant high-hat rhythm and effective use of both bass drum and high-hat as additional independent rhythmic resources, which identify him as a progressive and influential bop drummer.