CAESAR, JOHN

CAESAR, JOHN CAESAR, JOHN

CAESAR, JOHN(?–17 Jan. 1837), African Seminole (Black Seminole) leader, warrior, and interpreter, was born in the mid-eighteenth century and joined the Seminole nation in Florida, one of the many groups of African Seminole Indians who fought to maintain an autonomous and independent nation. There are few written records to reveal the early life histories of the many escaped Africans and American Indians in the maroon communities across the Americas, and Caesar’s life proves no exception. By the time his exploits were recorded in U.S. military records, Caesar was well acculturated to Seminole life and politics, and thus he had likely been a longtime member of the Seminole nation. His work as an interpreter between Native Seminoles and the U.S. military, however, reveals his early upbringing among English-speaking Americans. He grew up in a time of intense conflict between the Seminoles and European colonists, and had become a seasoned war veteran by the time of the Second Seminole War (1835–1842). Like many African Seminole women and men, Caesar had a spouse living on one of the local plantations, alongside the St. Johns River.

During the First Seminole War (1817), Caesar was a prominent leader who conducted raids on neighboring plantations and sought out runaway slaves and free African Americans to join the Seminole nation. He was closely associated with Seminole leader King Philip (Emathla), and together the two men battled the soldiers of the U.S. government during two wars. Acknowledged by U.S. military leaders and local plantation owners as a brilliant and powerful foe, Caesar followed a strategy of developing ties with enslaved African Americans on plantations in the St. Johns River area, using these relationships to acquire supplies and recruit slaves to join the African Seminole resistance.

African Seminoles like Caesar had a complex political and social relationship with Native Seminoles. The escape of slaves from plantations was encouraged by the early Spanish colonists who were in competition with English colonies over Florida territory. Although some Native Seminoles held African Seminoles as slaves, especially in the nineteenth century, African Seminoles had significant autonomy and political influence, particularly as the maroon nation grew in size and strength. There was significant intermarriage and cultural exchange among the various local communities which included African Seminoles, Native Seminoles, free and enslaved African Americans, and members of various Native American nations who joined forces with the Seminoles. Although some African Seminole slaves faced a form of slavery comparable to that practiced by European American plantation owners, others were adopted into Seminole clans, enslaved for a limited period of cultural adaptation to the new nation, and could marry and have children who would be free citizens of the nation. Caesar, like most African Seminoles, adopted the language and many of the cultural traditions of his Native Seminole counterparts, and African Seminoles brought their own African cultural traditions as well, which had a significant influence on the development of Seminole culture. Because African Seminoles were faced with the threat of enslavement on southern plantations, many served as fearless leaders in the Seminole wars against the United States in order to prevent the defeat of the Seminole nation. Many Native Seminoles also had their lives inextricably linked with those of African Seminoles due to intermarriage, and were unwilling to abandon their African Seminole family and friends to slave traders and plantation owners.

There were many other influential African Seminoles, including John Horse and Abraham, the latter serving as the chief associate, adviser, and interpreter to Seminole chief Micanopy. Like his counterpart Abraham, Caesar was the head adviser and interpreter to a Seminole chief, King Philip, father of Wild Cat and leader of the St. Johns River Seminoles. Caesar and Abraham worked together to sow the seeds of discontent among plantation slaves in Florida, and to develop relationships with free blacks and slaves who would assist in re-supplying the war effort. Caesar was successful in convincing numerous African slaves to join the Seminoles in their struggle for freedom.

In December 1835, with the beginning of the Second Seminole War, Caesar and King Philip attacked and destroyed numerous St. John’s sugar plantations. Slaves joined the Seminoles in further attacks, which continued into 1836. The Second Seminole War lasted for nearly seven years, and was characterized by the perspective of General Thomas Jesup, who declared: “This, you may be assured is a negro and not a Indian war” (Thomas S. Jesup Papers, The University of Michigan, Box 14). African Seminoles, Native Seminoles, and escaped African slaves fought together in battles that cost the U.S. military dearly.

The incident for which Caesar is perhaps best known occurred in early March 1836. General Gaines and his troops were suffering the effects of a lengthy siege by the Seminole warriors, when Caesar unexpectedly arrived at Gaines’s campsite to announce that the Seminoles wished to discuss a ceasefire agreement. Gaines agreed, and the parties met the next day in a series of discussions, with Caesar and Abraham serving as interpreters. Caesar’s role in initiating the negotiations remains a matter of debate; in any case, the talks ended abruptly with the arrival of General Clinch, whose advance forces fired on the Seminole participants. Although Gaines claimed a victory after his troops’ withdrawal, the Seminoles gained strategic advantages with the cease-fire holding long enough for the Seminoles to regroup and reinforce their position.

With the arrival of General Thomas S. Jesup in late 1836, the war took on a new and disturbing dimension, with Osceola’s fighters pushed back into King Philip and John Caesar’s St. Johns River territory. Caesar organized runaway slaves and a number of Native Seminoles into small bands of warriors, and attacked the plantations just outside St. Augustine. Caesar’s attacks were effective, and to strengthen his position he went on raiding parties to acquire horses. On 17 January 1837, he and his men were discovered attempting to steal horses from the Hanson plantation, and that evening, as they sat around their campfire, they were attacked by Captain Hanson’s men, who killed three warriors, including Caesar.

Caesar’s untimely death did not diminish the importance and influence of his life. His effectiveness at recruiting slaves from the plantations forced the U.S. military to negotiate over the issue of African Seminoles, and this resulted in the removal of African Seminoles alongside Native Seminoles, rather than their immediate re-enslavement on southeastern plantations. He was a major leader in a powerful maroon nation, which offered a unique opportunity for autonomy and freedom for Africans and American Indians who dared to escape plantations and European American colonial oppression. Caesar served as a potent symbol of an alternative vision for both African Americans and American Indians, that of merging cultures and political alliances. The two communities combined forces, and this new alliance proved a powerful and convincing tool in the hands of John Caesar, an African Seminole visionary, warrior, and political strategist.

Mulroy, Kevin. Freedom on the Border (1993).

Porter, Kenneth. The Black Seminoles (1996).

—JONATHAN BRENNAN

CAILLOUX, ANDRÉ

CAILLOUX, ANDRÉ(25 Aug. 1825–27 May 1863), first black soldier to die in the Civil War, was born in Plaquemine Parish, Louisiana, the son of André Cailloux, a slave skilled in masonry and carpentry, and Josephine Duvernay, a slave of Joseph Duvernay. On 15 July 1827 young André was baptized in St. Louis Cathedral in New Orleans.

After the death of Joseph Duvernay in 1828, Joseph’s sister, Aimée Duvernay Bailey, acquired André Cailloux and his parents and brought them all to New Orleans. There André likely learned the cigar-maker’s trade from his half-brothers, Molière and Antoine Duvernay, the freed sons of his mother, Josephine, and her master Joseph Duvernay. After he was manumitted by his mistress in 1846, Cailloux married another recently freed slave, Félicie Coulon, on 22 June 1847. Cailloux adopted Félicie’s son, Jean Louis, and the couple had four more children, three of whom survived into adulthood.

Cailloux and his wife moved into the ranks of the closely-knit New Orleans community of approximately eleven thousand free people of color (gens de couleur libre, Creoles of color, or Afro-Creoles). African or Afro-French/Spanish in ancestry, French in culture and language, and Catholic in religion, free people of color occupied an intermediate legal and social status between whites and slaves within Louisiana’s tripartite racial caste system. Denied political rights, free people of color nevertheless could own property, make contracts, and testify in court. They constituted the most prosperous and literate group of people of African descent in the United States, with a majority earning modest livings as artisans, skilled laborers, and shopkeepers, while a few enjoyed greater wealth. Some free people of color owned slaves, either for economic reasons or as a way of bringing together family members. Although most free people of color were of mixed race, they ran the gamut of phenotypes. Cailloux, for example, bragged of being the blackest man in New Orleans.

By the mid-1850s Cailloux, who had learned to read and write, had become a respectable, independent cigar maker. He resided in a Creole cottage worth about four hundred dollars, and purchased his slave mother, reuniting his family. Cailloux had his children baptized in the Catholic church, and sent his two sons to L’Institution Catholique des Orphelins dans l’Indigence (Institute Catholique), a school run by Afro-Creole intellectuals influenced by the inclusive and egalitarian ethos of the 1848 French Revolution. Cailloux’s peers elected him an officer of Les Amis de l’Ordre (the Friends of Order), one of the numerous mutual aid and benefit societies established by free people of color during the decade. These provided forums in which people of color could exercise leadership and engage in the democratic process.

By the late 1850s, however, the legal, social, and economic position of free people of color had deteriorated, and in 1861, Cailloux sold his cottage at auction. After the Civil War began, free people of color answered the governor’s request that they raise a militia regiment by forming the Defenders of the Native Land, otherwise known as the Louisiana Native Guards Regiment. They did so out of fear of possible reprisals if they failed to respond positively, and in the hope of improving their circumstances. Mutual aid and benefit societies formed themselves into companies for service in the regiment. Cailloux, for instance, assumed the rank of first lieutenant in Order Company. Louisiana officials, however, intended the regiment more for show than for combat.

When Confederate forces abandoned the city of New Orleans to Federal forces in late April 1862, the Louisiana Native Guards disbanded. In August 1862, however, U.S. General Benjamin F. Butler, suffering from a shortage of troops and fearing a Confederate attack on the city, authorized the recruitment of three regiments of free people of color, the first units of people of African descent formally mustered into the Union Army. While the field grade officers were white, the company officers were free people of color.

Cailloux received a commission as captain in the First Regiment. He quickly raised a company of troops, the majority of whom were Catholic free men of color drawn from the city’s Third District, where he worked and attended meetings of Les Amis de l’Ordre. But despite a formal directive that restricted enlistments to free men, Cailloux also welcomed runaway slaves, both French and English speaking. He no doubt shared the hope expressed by Afro-Creole activists in the pages of their newspaper L’Union, that military service would give blacks a claim to citizenship. Gentlemanly, athletic, charismatic, and confident, the thirty-eight-year-old Cailloux cut a dashing figure, belying the stereotype of black servility and inferiority.

Cailloux and the men of the Native Guards, however, faced daunting challenges. They suffered discrimination and abuse at the hands of white civilians, soldiers, and their own national government. In the field, they found themselves consigned primarily to guard duty or to backbreaking manual labor. To make matters worse, General Nathaniel P. Banks, Butler’s successor, determined to purge the Native Guard Regiments of their black officers.

Yearning to prove themselves in combat, Cailloux and two regiments of the Native Guards received their chance on 27 May 1863 at Port Hudson, Louisiana, one of two remaining Confederate strongholds on the Mississippi River. There Cailloux’s company spearheaded an assault by the First and Third Regiments against a nearly impregnable Confederate position. As the Native Guards approached to within about two hundred yards of the entrenched Confederate force, they encountered withering musket and artillery fire and the attacking lines broke. Cailloux and other officers attempted to rally their men several times. Finally, in the midst of the chaos, Cailloux, holding his sword aloft in his right hand while his broken left arm dangled at his side, exhorted his troops to follow him. Advancing well in front, he led a charge. As he reached a backwater obstacle, he was struck and killed by a shell. The remaining Native Guards retreated, as did Union forces all along the battle line that day. Cailloux’s body lay rotting in the broiling sun for forty days until the surrender of Port Hudson on 8 July 1863.

Cailloux’s heroics encouraged those supporting the cause of using black troops in combat. L’Union declared that Cailloux’s patriotism and valor had vindicated blacks of the charge that they lacked manliness. To memorialize Cailloux, Afro-Creole activists orchestrated a public funeral in New Orleans presided over by the Reverend Claude Paschal Maistre, a French priest recently suspended by the archbishop of New Orleans for advocating emancipation and the Union cause. Emboldened by Cailloux’s heroism, blacks, both slave and free, asserted their growing political consciousness. They packed the city’s main streets in unprecedented numbers as the military cortege bearing Cailloux’s casket made its way to St. Louis Cemetery Number 2. Maistre eulogized Cailloux as a martyr to the cause of Union and freedom; northern newspapers gave extensive coverage to his death and funeral; George H. Boker, a popular poet, memorialized Cailloux in his ode, The Black Captain; and Afro-Creole activists in New Orleans elevated him to almost mythic status, invoking his name in their campaign against slavery and on behalf of voting rights.

In October 1864 delegates to the National Negro Convention literally wrapped themselves in Cailloux’s banner. With the First Regiment’s bloodstained flag hanging in a place of honor, numerous speakers invoked Cailloux’s indomitable spirit and heroism and launched a nationwide campaign for black suffrage through the creation of the National Equal Rights League. Both in life and in death, André Cailloux, whose surname means “rocks” or “stones” in French, served to unite and inspire people of color in their struggle for unity, freedom, and equality.

Edmonds, David C. The Guns of Port Hudson: The Investment, Siege, and Reduction, 2 vols. (1984).

Ochs, Stephen J. A Black Patriot and a White Priest: André Cailloux and Claude Paschal Maistre in Civil War New Orleans (2000).

_______ “American Spartacus.” American Legacy, Fall 2001, 31–36.

Wilson, Joseph T. The Black Phalanx (1890).

Obituary: New York Times, 8 Aug. 1863.

—STEPHEN J. OCHS

CALIVER, AMBROSE

CALIVER, AMBROSE(25 Feb. 1894–29 Jan. 1962), educator, college administrator, and civil servant, was born in Saltville, Virginia, the youngest child of Ambrose Caliver Sr. Little is known about his parents, but very early in his life he and his two siblings moved to Knoxville, Tennessee, where they were raised by an aunt, Louisa Bolden. Bolden, a widowed cook who took in boarders to make ends meet, allowed Caliver to accept a job at a very young age. According to one account, the young Caliver was working in a coal mine by the time of his eighth birthday. Early employment, however, did not prevent him from attending school regularly. After receiving an education from Knoxville’s public school system, he enrolled at Knoxville College, where he obtained his BA in 1915. He eventually earned an MA from the University of Wisconsin (1920) and a PhD from Columbia University (1930).

After graduating from Knoxville, Caliver immediately sought employment as an educator. In 1915 he married his childhood sweetheart, Rosalie Rucker, and they both took various teaching jobs, first in Knoxville and then in El Paso, Texas. By 1917 they had returned to Tennessee, where they received faculty positions at Fisk University in Nashville. Caliver’s acceptance of the position at Fisk was significant, because he became one of the few black faculty members hired on campus. Caliver began working at Fisk during one of the most tumultuous points in the university’s history. Under the leadership of Fayette A. McKenzie, Fisk gained the unwarranted reputation of being out of touch with the African American population. Caliver assisted in changing this perception. An ardent believer in the industrial and manual arts, he encouraged Fisk’s students to take woodshop and other courses that would teach them how to work with their hands. Caliver believed that these skills would not only benefit the students financially but also make them assets to the local black community. According to one observer, one of Caliver’s more memorable moments at Fisk was when he drove a bright red wagon that his students had made in his workshop across the platform during a university assembly.

Fisk administrators soon recognized the talent of their young faculty member and quickly gave him other responsibilities. In a continuing effort to strengthen the school’s ties to the local black community, Caliver organized the Tennessee Colored Anti-Tuberculosis Society. Serving four years as the organization’s director and chair of its executive committee, Caliver sought to increase awareness and prevent the spread of the disease among Tennessee’s African American population. His other major administrative appointments at Fisk included a spell as university publicity director in 1925, and as dean of the Scholastic Department the following year. In 1927 Caliver was appointed Fisk’s first African American dean of the university (1927).

Fisk only briefly enjoyed Caliver’s services as dean. Two years after his appointment, he took a one-year leave from his duties to complete the requirements for his doctorate at Columbia University. Caliver never returned to his position at Fisk. Shortly before his graduation, he received two job offers—one for a faculty position at Howard University and, shortly afterward, another for a position at the U.S. Office of Education. In 1930 he accepted the latter job and became the Office of Education’s Specialist in Negro Education. It was in this post that Caliver made what is arguably his most lasting contribution to African American education.

During his tenure in the U.S. Office of Education, Caliver participated in numerous studies and published several articles and monographs dealing with the status of African American education. These works included the pamphlets Bibliography on the Education of the Negro (1931), Background Study of Negro College Students (1933), and Rural Elementary Education among Negro Jeanes Supervisors (1933). Some of his monographs during this period were The Education of Negro Teachers in the United States (1933), Secondary Education for Negroes (1933), and the Availability of Education to Negroes in Rural Communities (1935). Caliver was also instrumental in creating the National Advisory Committee of the Education of Negroes. This group, consisting of many leading educators from across the United States, sought to discuss the problems and develop programs to enhance black education. Hoping to benefit the greatest number of African Americans, the organization tended to focus on issues in secondary schools, such as poor facilities and inadequate materials, rather than on inadequacies in African American institutions of higher learning.

The study of secondary schools undoubtedly contributed to what Caliver saw as the greatest problem facing black education: adult illiteracy. According to some estimates, approximately one quarter of the 12.6 million African Americans were illiterate. Caliver was determined to place this issue in the national spotlight. To accomplish this, he reached out to prominent African American organizations and leaders and encouraged them to take a more active role. Caliver also called for the preparation of instructional materials, the creation of teacher-training workshops, and the development of adult-education programs at historically black colleges and universities. He oversaw the creation of several readers to increase literacy. These readers, “A Day with the Brown Family,” “Making a Good Living,” and “The Browns Go to School.” not only increased literacy skills but also emphasized family living, thrift, and leisure activities.

In addition to his contributions to adult education, Caliver also succeeded in utilizing radio as a tool for education and instilling racial pride. In 1941, with funding from such philanthropic groups as the Julius Rosenwald Fund, he created Freedom’s People, a nine-part series examining African American life, history, and culture. From September 1941 through April 1942, the National Broadcasting Company broadcast the program, one of the first of its kind devoted exclusively to African Americans. Freedom’s People taught its listeners not only about famous black historical figures but also about the contributions of blacks in the areas of science, music, and industry. The program featured guest appearances by some of the most prominent African Americans of the day including JOE LOUIS, A. PHILIP RANDOLPH, and PAUL ROBESON.

For the next two decades Caliver’s efforts in adult education and literacy increased. From 1946 to 1950, he directed the Office of Education’s Literacy Education Project, and in 1950 he became the assistant to the commissioner of education. By 1955 Caliver was the chief of the Office of Education’s Adult Education Section. This new appointment, along with his election as the president of the Adult Education Association of the United States six years later, contributed to his reputation as one of the most ardent crusaders against illiteracy in the federal government. Ambrose Caliver died in January 1962, still working as diligently as he had in his youth. At the time of his death he was moving forward with plans to expand and increase the services of the Adult Education Association of the United States.

Daniel, Walter G., and John B. Holden. Ambrose Caliver: Adult Educator and Civil Servant (1966).

Wilkins, Theresa B. “Ambrose Caliver: Distinguished Civil Servant.” Journal of Negro Education 31 (Spring 1962): 212–214.

Obituary: Washington Post, 2 Feb. 1942.

—LEE WILLIAMS JR.

CALLOWAY, CAB

CALLOWAY, CAB(25 Dec. 1907–18 Nov. 1994), popular singer and bandleader, was born Cabell Calloway III in Rochester, New York, the third of six children of Cabell Calloway Jr., a lawyer, and Martha Eulalia Reed, a public school teacher. In 1920, two years after the family moved to the Calloways’ hometown of Baltimore, Maryland, Cab’s father died. Eulalia later remarried and had two children with John Nelson Fortune, an insurance salesman who became known to the Calloway children as “Papa Jack.”

Although he later enjoyed a warm relationship with his stepfather, the teenaged Cab had a rebellious streak that tried the patience of parents attempting to maintain their status as respectable Baltimoreans. He often skipped school to go to the nearby Pimlico racetrack, where he both earned money selling newspapers and shining shoes and began a lifelong passion for horse racing. After his mother caught him playing dice on the steps of the Presbyterian church, however, he was sent in 1921 to Downingtown Industrial and Agricultural School, a reform school run by his mother’s uncle in Pennsylvania. When he returned to Baltimore the following year, Calloway recalls that he resumed hustling but also worked as a caterer, and that he studied harder than he had before and excelled at both baseball and basketball at the city’s Frederick Douglass High School. Most significantly, he resumed the voice lessons he had begun before reform school, and he began to sing both in the church choir and at several speakeasies, where he performed with Johnny Jones’s Arabian Tent Orchestra, a New Orleans-style Dixieland band. In his senior year in high school, Calloway played for the Baltimore Athenians professional basketball team, and in January 1927 he and Zelma Proctor, a fellow student, had a daughter, whom they named Camay.

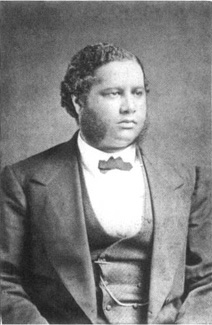

Cab Calloway, propelled to stardom with his exuberant “Minnie the Moocher,” was photographed by Carl Van Vechten, 1933. Library of Congress

In the summer after graduating from high school, Calloway joined his sister Blanche, a star in the popular Plantation Days revue, on her company’s mid-western tour, and, by his own account, “went as wild as a March hare,” chasing “all the broads in the show” (Calloway, 54). When the tour ended in Chicago, Illinois, he stayed and attended Crane College (now Malcolm X University). While at Crane he turned down an offer to play for the Harlem Globetrotters, not, as his mother had hoped, to pursue a law career, but instead to become a professional singer. He worked nights and weekends at the Dreamland Café and then won a spot as a drummer and house singer at the Sunset Club, the most popular jazz venue on Chicago’s predominantly African American South Side. There he befriended LOUIS ARMSTRONG, then playing with the Carroll Dickerson Orchestra, who greatly influenced Calloway’s use of “scat,” an improvisational singing style that uses nonsense syllables rather than words.

When the Dickerson Orchestra ended its engagement at the Sunset in 1928, Calloway served as the club’s master of ceremonies and, one year later, as the leader of the new house band, the Alabamians. His position as the self-described “dashing, handsome, popular, talented M.C. at one of the hippest clubs on the South Side” (Calloway, 61) did little to help his already fitful attendance at Crane, but it introduced him to many beautiful, glamorous, and rich women. He married one of the wealthiest of them, Wenonah “Betty” Conacher, in July 1928. Although he later described the marriage as a mistake, at the time he greatly enjoyed the “damned comfortable life” that came with his fame, her money, and the small house that they shared with a South Side madam.

In the fall of 1929 Calloway and the Alabamians embarked on a tour that brought them to the mecca for jazz bands of that era, Harlem in New York City. In November, however, a few weeks after the stock market crash downtown on Wall Street, the Alabamians also crashed uptown in their one chance for a breakout success, a battle of the bands at the famous Savoy Ballroom. The hard-to-please Savoy regulars found the Alabamians’ old-time Dixieland passé and voted overwhelmingly for the stomping, more danceable music of their rivals, the Missourians. The Savoy audience did, however, vote for Calloway as the better bandleader, a tribute to his charismatic stage presence and the dapper style in which he outfitted the Alabamians.

Four months later, following a spell on Broadway and on tour with the pianist FATS WALLER in the successful Connie’s Hot Chocolate revue, he returned to the Savoy as the new leader of the Missourians, renamed Cab Calloway and His Orchestra. In 1931 the band began alternating with DUKE ELLINGTON’s orchestra as the house band at Harlem’s Cotton Club, owned by the gangster Owney Madden and infamous for its white-audiences-only policy. Calloway also began a recording career. Several of his first efforts for Brunswick Records, notably “Reefer Man” and “Kicking the Gong Around,” the latter about characters in an opium den, helped fuel his reputation as a jive-talking hipster who knew his way around the less salubrious parts of Manhattan. Although he denied firsthand experience of illicit drugs, Calloway did admit to certain vices—fast cars, expensive clothes, “gambling, drinking, partying [and] balling all through the night, all over the country” (Calloway, 184).

It was 1931’s “Minnie the Moocher,” with its scat-driven, call-and-response chorus, that became Calloway’s signature tune and propelled him to stardom. The most prosaic version of the chorus had Cab calling out, “Hi-de-hi-de-hi-di-hi, Ho-de-ho-de-ho-de-ho” or, when the mood took him, “Oodlee-odlyee-odlyee-oodle-doo” or “Dwaa-de-dwaa-de-dwaa-de-doo,” while his orchestra—and later the audience—responded with the same phrase. Calloway recalled in his autobiography that the song came first and the chorus was later improvised when he forgot the lyrics during a radio broadcast. The song’s appeal was broadened in 1932 by its appearance in the movie The Big Broadcast and in a Betty Boop cartoon short, Minnie the Moocher. Radio broadcasts from the Cotton Club and appearances on radio with Bing Crosby made Calloway one of the wealthiest entertainers during the Depression era. The Calloway Orchestra embarked on several highly successful national tours and in 1935 became one of the first major black jazz bands to tour Europe.

Although the Calloway Orchestra was arguably the most popular jazz band of the 1930s and 1940s, most jazz critics view the bands of Duke Ellington, Louis Armstrong, and COUNT BASIE as more musically sophisticated. ALBERT L. MURRAY’s influential Stomping the Blues (1976) does not even mention Calloway, although it does list several members of his orchestra, including the tenor saxophonist Chu Berry and the trumpeter DIZZY GILLESPIE, who joined the band in 1939 and left two years later, after he stabbed Calloway in the backside during a fight. With the drummer Cozy Cole and the vibraphonist Tyree Glenn, the Calloway Orchestra showcased its rhythmic virtuosity in several instrumentals, including the sprightly “Bye Bye Blues” and the sensual “A Ghost of a Chance,” both recorded in 1940.

It was, however, Calloway’s exuberant personality, his cutting-edge dress style—he was a pioneer of the zoot suit—and his great rapport with his audiences that packed concert halls for nearly two decades. In the 1940s he was ubiquitous, appearing on recordings, radio broadcasts of his concerts, and in movies such as Stormy Weather (1943), in which he starred with LENA HORNE, BILL “BOJANGLES” ROBINSON, KATHERINE DUNHAM, and FATS WALLER. In 1942, he hosted a satirical network radio quiz show, “The Cab Calloway Quizzicale.” Calloway even changed the way Americans speak, with the publication of Professor Cab Calloway’s Swingformation Bureau and The New Cab Calloway’s Hepsters Dictionary: Language of Jive (1944), which became the official jive language reference book of the New York Public Library. The Oxford English Dictionary credits Calloway’s song “Jitter Bug” as the first published use of that term.

The end of World War II marked dramatic changes in Calloway’s professional and personal lives. In 1948 the public preference for small combos and the bebop style of jazz, pioneered by Gillespie, among others, forced Calloway to break up his swing-style big band. One year later Calloway divorced Betty Conacher, with whom he had adopted a daughter, Constance, in the late 1930s, and married Zulme “Nuffie” McNeill, with whom he would have three daughters, Chris, Lael, and Cabella. His career revived, however, in 1950, when he landed the role of Sportin’ Life in the revival of George Gershwin’s Porgy and Bess on Broadway and in London and Paris. The casting was inspired, since Gershwin had modeled the character of Sportin’ Life on Calloway in his “Hi-de-hi” heyday. From 1967 to 1970 he starred with PEARL BAILEY in an all-black Broadway production of Hello Dollyl, and in 1980 he endeared himself to a new generation of fans, with his performance of “Minnie the Moocher,” in the film The Blues Brothers, with John Belushi and Dan Aykroyd. That role led to appearances on the television shows The Love Boat and Sesame Street and on Janet Jackson’s music video “Alright,” which won the 1990 Soul Train award for best rhythm and blues/urban contemporary music video.

In June 1994 Calloway suffered a stroke at his home in White Plains, New York, and died five months later at a nursing home in Hockessin, Delaware. President Bill Clinton, who had awarded Calloway the National Medal of the Arts a year earlier, paid tribute to him as a “true legend among the musicians of this century, delighting generations of audiences with his boundless energy and talent” (New York Times, 30 Nov. 1994). Calloway, however, probably put it best when he described himself in his autobiography as, “the hardest jack with the greatest jive in the joint.”

Calloway’s papers are held at Boston University.

Calloway, Cab, and Bryant Rollins. Of Minnie the Moocher and Me (1976).

Schuller, Gunther. The Swing Era: The Development of Jazz, 1930–1945 (1989).

Obituary: New York Times, 20 Nov. 1994.

—STEVEN J. NIVEN

CALLOWAY, ERNEST

CALLOWAY, ERNEST(1 Jan. 1909–31 Dec. 1989), labor activist, journalist, and educator, was born in Heberton, West Virginia, the son of Ernest Calloway Sr.; his mother’s name is unknown. The family moved to the coalfields of Letcher County, Kentucky, in 1913, where Calloway’s father, “Big Ernest,” helped organize the county’s first local chapter of the United Mine Workers of America. The Calloways were one of the first black families in the coal-mining communities of eastern Kentucky, and Ernest was, by his own description, “one of those unique persons . . . a black hillbilly.” Calloway attended high school in Lynchburg, Virginia, but ran away to New York in 1925 and arrived in the middle of the Harlem Renaissance. He worked as a dishwasher in Harlem until his mother fell ill, when he returned to Kentucky at age seventeen and worked in the mines of the Consolidated Coal Company until 1930. During the early 1930s he traveled as a drifter around the United States and Mexico.

Calloway came to the end of his resources at a tent colony near the small town of Ensenada in the Baja Mountains of Mexico in 1933. There he had a frightening hallucinatory experience that changed his life. “Damnedest experience that whole night,” he later recounted to an interviewer. “I think this was the first time that, the morning after getting out of those mountains and that frightening experience, the first time that I really began thinking about myself and about people and what makes the world tick.” He returned to the coal mines of Kentucky determined to move beyond a drifter’s existence.

Inspired by his strange experience in the mountains, Calloway submitted an article on marijuana use to Opportunity, the magazine of the National Urban League, in 1933. Opportunity rejected it, and, sadly, a copy of it did not survive. The magazine did ask him to write another article, however, on the working conditions of blacks in the Kentucky coalfields. He submitted the second article, “The Negro in the Kentucky Coal Fields,” which appeared in March 1934. This article resulted in a scholarship for Calloway to Brookwood Labor College in New York, a training facility for labor organizers founded by the pacifists Helen and Henry Fink and headed by A. J. Muste. Moreover, the article began Calloway’s long involvement with labor issues.

From 1935 to 1936 Calloway worked in Virginia and helped organize the Virginia Workers’ Alliance, a union of unemployed Works Progress Administration workers. He helped organize a conference in 1936 to ally the labor movement with the unemployed—groups organized by socialists, communists, Trotskyists, and unemployment councils. After turning down an offer to recruit African Americans into a front group for the U.S. State Department and its intelligence services, Calloway moved to Chicago in 1937. There he helped organize the Red Caps, as railway station porters were known, and other railroad employees into the United Transport Employees Union. He also helped write the resolution creating the 1942 Committee against Discrimination in the Congress of Industrial Organizations (CIO). When the first peacetime draft law came into effect in 1939, Calloway was among the first African Americans to refuse military service as a protest against race discrimination. Although the case received national publicity, it was never officially settled, and Calloway never served in the Jim Crow U.S. Army.

Calloway’s career in news journalism began when he joined the National CIO News editorial staff in 1944. Two years later he married DeVerne Lee, a teacher who had led a protest against racial segregation in the Red Cross in India during World War II. DeVerne Calloway later served as the first black woman elected to the state legislature in Missouri. She did much to increase state aid to public education, improve welfare grants, and reform the prison system in the state.

In 1947 Calloway received a scholarship from the British Trade Union Congress to attend Ruskin College in Oxford, England, where he spent a year. He then returned to the United States and began working with Operation Dixie, the CIO’s southern organizing drive in North Carolina. Because of a dispute over organizing tactics in an attempt to unionize workers at R. J. Reynolds Tobacco Company, Calloway left the CIO in 1950 and returned to Chicago. Harold Gibbons of the St. Louis Teamsters union enlisted him to establish a research department for Teamsters Local 688 in St. Louis, which was at that time one of the most racially progressive union locals in the nation.

In the 1950s Calloway played a pivotal role in civil rights and labor activism in St. Louis. In 1951, three years prior to the U.S. Supreme Court’s school desegregation decision in Brown v. Board of Education, Calloway advised Local 688 on a plan to integrate the St. Louis public schools; the St. Louis Board of Education rejected the Teamsters proposals. The St. Louis branch of the NAACP elected Calloway president in 1955. Within the first two years of his presidency, membership grew from two thousand to eight thousand members. He led successful efforts to gain substantial increases in the number of blacks employed by St. Louis taxi services, department stores, the Coca-Cola Company, and Southwestern Bell. Under his leadership, the group helped defeat a proposed city charter in 1957 that did not include support for civil rights.

Calloway’s political involvement included serving in 1959 as campaign director for the Reverend John J. Hicks, who became the first black elected to the St. Louis Board of Education. Calloway also directed Theodore McNeal’s 1960 senatorial campaign. McNeal won by a large margin, becoming the first black elected to the Missouri Senate. In 1961 Calloway worked as the technical adviser for James Hurt Jr. in his successful campaign as the second black to be elected to the St. Louis school board. He also helped his wife, DeVerne, win her historic spot in the Missouri legislature in her first bid for public office.

In 1961 the couple began publishing Citizen Crusader, later named New Citizen, a newspaper covering black politics and civil rights in St. Louis. It provided Calloway with a larger platform for his writing than anything had previously. During this period he developed a passion for explaining in numbers and tables the arithmetic of African American political power in St. Louis. The newspaper lasted until November 1963, but even after it stopped publishing, the Calloways continued to produce newspapers, including one entitled Truth, in support of their political allies. As a testament to the effectiveness of these papers, in 1964 supporters of Barry Goldwater published their own version of Truth, complete with an identical masthead, solely to take a stand against a local Democratic Party candidate endorsed by the Calloways’ Truth.

Calloway worked with the Committee on Fair Representation in 1967 to develop a new plan for congressional district reapportionment. Supported by black representatives in the Missouri legislature and a coalition of white Republicans and Democrats, the plan created a First Congressional District more compatible with black interests. In 1968 Calloway filed as a candidate for U.S. Congress in the new district but was defeated in the Democratic primary by William Clay, who became the first black elected to the U.S. Congress from Missouri.

In 1969 Calloway lectured part-time for St. Louis University’s Center for Urban Programs. He became an assistant professor when he retired as research director for the Teamsters in June 1973 and, later, Professor Emeritus of Urban Studies at St. Louis University. From his modest roots, Calloway pursued a multifaceted life, all the while creating a record of thoughtful reflections on public events and history over a lifetime of change. He suffered a disabling stroke in 1982 and died after a series of additional strokes. His name is still spoken with reverence in his hometown and among people familiar with his work.

Ernest Calloway’s papers, as well as those of DeVerne Calloway, are in the Western Historical Manuscript Collection-St. Louis at the University of Missouri-St. Louis.

Burnside, Gordon. “Calloway at 74.” St. Louis Magazine, March 1983.

Bussel, Robert. “A Trade Union Oriented War on the Slums: Harold Gibbons, Ernest Calloway, and the St. Louis Teamsters in the 1960s.” Labor History 44, no. 1 (2003): 49–67.

Cawthra, Benjamin. “Ernest Calloway: Labor, Civil Rights, and Black Leadership in St. Louis.” Gateway Heritage, Winter 2000–2001, 5–15.

—KENNETH F. THOMAS

CANNON, GEORGE DOWS

CANNON, GEORGE DOWS(16 Oct. 1902–31 Aug. 1986), physician and political activist, was born in Jersey City, New Jersey, the son of George E. Cannon and Genevieve Wilkinson. His father was a prominent and politically connected physician who graduated from Lincoln University in Pennsylvania and the New York Homeopathic Medical College. His mother, a teacher, was descended from a leading Washington, D.C., family that was free before the Civil War. Cannon and his sister, Gladys, grew up in an eighteen-room red brick house on a main Jersey City thoroughfare where their parents regularly received a retinue of prestigious visitors, including BOOKER T. WASHINGTON, numerous doctors from the all-black National Medical Association, and several Republican Party officeholders. Cannon greatly admired his father and emulated his professional and political involvements.

At his father’s alma mater, Lincoln University, a Presbyterian institution, Cannon performed acceptably but without academic distinction. He scored well enough in his premedical courses, however, to be eligible for medical school upon graduation from Lincoln in 1924. Cannon gained admission to Columbia University’s College of Physicians and Surgeons through the intervention of his father, who knew the president of the university. Despite enduring racially prejudiced professors, Cannon completed his freshman year with passing grades on all of his exams. His father’s accidental death in April 1925 kept him from classes for a short time. Although Cannon fulfilled all of his class and laboratory assignments, his brief absence became a pretext for the dean to fail him in all of his courses. Cannon believed that racial prejudice and the manner of his admission had stirred a dislike for him. Because the Howard and Meharry medical schools would not admit him during the following fall, he entered Howard’s graduate school to study for a master’s degree in Zoology with the famed ERNEST EVERETT JUST. Impressed with Cannon’s proficiency and saddened by his sorrowful experience at Columbia, Just recommended him to Rush Medical College in Chicago. Though the staff at Rush was less racist than that at Columbia, Cannon and the other black student, LEONIDAS BERRY, were told that each had been admitted so that the other one would not be lonely. Nonetheless, Cannon excelled in his work and made up for the lost time resulting from his ouster at Columbia. He was diagnosed with tuberculosis, however, during the final month before graduation. Treatment at a sanatorium in Chicago for nearly two years preceded his reentry to Rush. He earned the MD degree on 18 December 1934 after an internship at Chicago’s all-black Provident Hospital. Continued health problems put Cannon into the Waverly Hills Hospital, a Louisville, Kentucky, sanatorium from 1934 through 1936, where he received treatment and pursued a medical residency. In the meantime, he had married his college sweetheart, Lillian Mosely, on 25 December 1931. The uncertainties surrounding his health compelled the couple to forgo parenthood, and they never had children.

Despite Cannon’s fragile health, he vigorously developed as a leading New York City physician. He did not want to be bound to Harlem Hospital for staff privileges, so he tried throughout the late 1930s and 1940s for admittance to other hospitals. He was accepted on the staff of the Hospital for Joint Diseases in 1944. At the Triboro Tuberculosis Hospital, a racist physician, who opposed his appointment, eventually died and thus cleared the way for Cannon’s appointment in 1947. He also gained privileges to treat and admit patients at the hospital for the Daughters of Israel. Cannon still encountered racist roadblocks at other facilities. He targeted hospitals with religious affiliations to admit black physicians to their staffs. Catholic, Episcopal, and Presbyterian hospitals rebuffed him. In the latter case, his membership at St. James Presbyterian Church in Harlem did not matter. At Lutheran Hospital a sympathetic white colleague made Cannon his substitute in the x-ray department, but hospital authorities overruled him. Jewish hospitals were more receptive. Mt. Sinai Hospital initially brought in Cannon as an assistant adjunct radiologist. Over time his radiology training at Triboro and his success at Mt. Sinai earned Cannon the respect he deserved among his black and white peers.

Cannon engaged in other struggles for black professionals and patients. He belonged to the integrated Physicians Forum, an alternative organization to the racially restrictive county medical societies and their parent group, the American Medical Association (AMA). Forum doctors focused on health care for the disadvantaged and fought racism in medical institutions. In Harlem he joined the Upper Manhattan Medical Group, a branch of the Health Insurance Plan of the City of New York, which rendered services through a prepaid health delivery system. Through the Physicians Forum, Cannon challenged the fee-for-service payment practice that most AMA doctors preferred. The improvement of conditions at Harlem Hospital also drew Cannon’s attention. As president of the all-black Manhattan Central Medical Society and chairman of its Subcommittee on Health and Hospitals, Cannon exerted pressure upon city officials, who then corrected the lack of x-ray equipment, the absence of psychiatric services, and the inadequate number of surgeons to perform tonsillectomies. They also pressed city officials to open to blacks all municipal nursing schools beyond the two at Harlem and Lincoln hospitals.

Though a maverick Democrat, Cannon did not hesitate to form coalitions with radicals, including communists. As chair of the Non-Partisan Citizens’ Committee in 1943 and 1945, he backed the successful candidacy of BENJAMIN JEFFERSON DAVIS JR., a Communist, as Harlem’s representative to City Council. Cannon himself was asked to run for city council and the state senate, both positions that he could have easily won. Whenever his party seemed too passive on civil rights matters, he supported candidates from other political groups. In 1948, for example, Henry A. Wallace, the Progressive Party presidential candidate, in Cannon’s opinion, was a stronger advocate for civil rights than either Governor Thomas E. Dewey, the Republican, or President Harry Truman, the Democrat. Hence, Cannon became the Chairman of the Harlem Wallace-for-President Committee. Cannon held that it was possible to work with communists and Progressives on matters of race. Though he eschewed radical ideologies, Cannon’s involvement with the Physicians Forum and its efforts for government-guaranteed health care and his political cooperation with radicals suggested to zealous anticommunists that Cannon’s political sympathies were suspect. He was an enemy of Russia, he often said. Nonetheless, anyone who wished to work with him on black advancement was always a welcome ally.

Cannon’s affiliations with the NAACP and the NAACP Legal Defense Fund (LDF) complemented his political activism. He served as the chairman of the life membership campaign for the New York state NAACP, and between 1956 and 1966 he held the same position for the national organization. At a dinner that he attended with Vice President Richard M. Nixon, Cannon planned to challenge the future president to buy an NAACP life membership. Before Cannon could successfully press his point, a black Nixon supporter said that the vice president should not pursue this symbolic action. Cannon, however, never forgot Nixon’s affront to the NAACP. In 1962 Cannon became the secretary of the LDF, a position he held until 1984. Hence, during the height of the civil rights movement, he sided with the integrationist thrust of the NAACP and the LDF. The Black Power movement never drew support from Cannon.

His social and political activism extended to higher education. In 1947 Cannon became an alumni trustee of Lincoln University in Pennsylvania and later chairman of the board of trustees. His Lincoln classmate HORACE MANN BOND had become in 1946 the first black president of the university, and each believed that Lincoln could become a model for racially integrated higher education. Though Cannon did not share Bond’s intense zeal for African studies and forging stronger connections with emerging African nations, both understood that training leaders in various professions for both sides of the Atlantic was a crucial mission for their institution. Cannon developed positions on the role of faculty, continuation of the theological seminary, the need for greater alumni support, and the necessity of confronting the hostility of whites in neighboring Oxford, Pennsylvania. Cannon’s frequent and detailed correspondence with Bond and his several successors showed a deep involvement in the affairs of Lincoln University that lasted through the 1980s. When Lincoln became the principal trustee of the Barnes Foundation, a repository of priceless modern art in suburban Philadelphia, Cannon delved into another area of educational and cultural affairs that further distinguished his alma mater.

When Cannon died in 1986, his Rush classmate Leonidas H. Berry eulogized Cannon and observed that his fragile health gave him a special empathy for his patients and motivated his extensive efforts for the uplift of African Americans. He lived to be an octogenarian despite diagnoses that belied the possibility for such a long and consequential career.

The George D. Cannon Papers are held at the Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture of the New York Public Library. See also the George D. Cannon Files, Horace Mann Bond Papers, Lincoln University, Pennsylvania.

James, Daniel. “Cannon the Progressive.” New Republic, 18 Oct. 1948.

—DENNIS C. DICKERSON

CARDOZO, FRANCIS LOUIS

CARDOZO, FRANCIS LOUIS(1 Feb. 1837–22 July 1903), minister, educator, and politician, was born in Charleston, South Carolina, the son of a free black woman (name unknown) and a Jewish father. It is uncertain whether Cardozo’s father was Jacob N. Cardozo, the prominent economist and editor of an anti-nullification newspaper in Charleston during the 1830s, or his lesser-known brother, Isaac Cardozo, a weigher in the city’s customhouse. Born free at a time when slavery dominated southern life, Cardozo enjoyed a childhood of relative privilege among Charleston’s antebellum free black community. Between the ages of five and twelve he attended a school for free blacks, then he spent five years as a carpenter’s apprentice and four more as a journeyman. In 1858 Cardozo used his savings to travel to Scotland, where he studied at the University of Glasgow, graduating with distinction in 1861. As the Civil War erupted at home, he remained in Europe to study at the London School of Theology and at a Presbyterian seminary in Edinburgh.

In 1864 Cardozo returned to the United States to become pastor of the Temple Street Congregational Church in New Haven, Connecticut. That year he married Catherine Rowena Howell; they had six children, one of whom died in infancy. During his brief stay in the North, Cardozo became active in politics. In October 1864 he was among 145 black leaders who attended a national black convention in Syracuse, New York, that reflected the contagion of rising expectations inspired by the Civil War and emancipation.

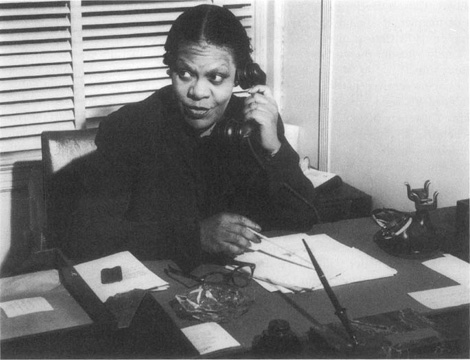

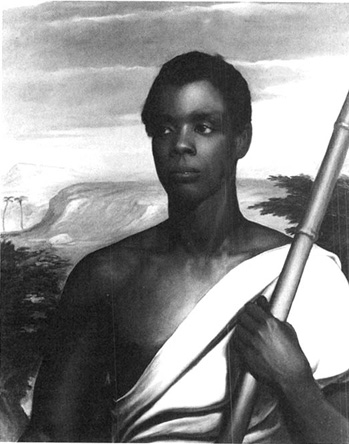

Francis L. Cardozo became the first black state official in South Carolina during Reconstruction. Library of Congress

In June 1865 Cardozo became an agent of the American Missionary Association (AMA) and almost immediately returned to his native South Carolina. His brother Thomas Cardozo, the AMA’s education director, was accused of having an affair with a student in New York, and Francis Cardozo replaced him while also assuming the directorship of the Saxton School in Charleston. Within months the school was flourishing under his leadership, with more than one thousand black students and twenty-one teachers. In 1866 Cardozo helped to found the Avery Normal Institute and became its first superintendent.

Unlike many South Carolinians of mixed race, Cardozo made no distinction between educating blacks who were born free and former slaves, nor did he draw conclusions, then common, about intellectual capacity based on skin color gradations. Instead, he was committed to universal education regardless of “race, color or previous condition,” a devotion he considered “the object for which I left all the superior advantages and privileges of the North and came South, it is the object for which I have labored during the past year, and for which I am willing to remain here and make this place my home.”

Despite the fact that he claimed to possess “no desire for the turbulent political scene,” Cardozo soon found himself in the middle of Reconstruction politics. In 1865 he attended the state black convention in Charleston, where he helped draft a petition to the state legislature demanding stronger civil rights provisions. In 1868, following the passage of the Reconstruction Acts by Congress, he was elected as a delegate to the South Carolina constitutional convention. From the onset he was frank about his intentions, “As colored men we have been cheated out of our rights for two centuries and now that we have the opportunity I want to fix them in the Constitution in such a way that no lawyer, however cunning, can possibly misinterpret the meaning.”

Cardozo wielded considerable influence at the convention. As chair of the Education Committee, he was instrumental in drafting a plan, which was later ratified, to establish a tax-supported system of compulsory, integrated public education, the first of its kind in the South. Despite his support for integration, however, he also understood the logic articulated by black teachers of maintaining support for separate schools for blacks who wanted to avoid the hostility and violence that often accompanied integration. Consistently egalitarian, he opposed poll taxes, literacy tests, and other forms of what he called “class legislation.” Moreover, he fought proposals to suspend the collection of wartime debts, which he thought would only halt the destruction of “the infernal plantation system,” a process he deemed central to Reconstruction’s success. In fact, Cardozo argued, “We will never have true freedom until we abolish the system of agriculture which existed in the Southern States. It is useless to have any schools while we maintain the stronghold of slavery as the agricultural system of the country.” Thus, he called for a tripartite approach to enfranchisement: universal access to political participation and power, comprehensive public education, and reform initiatives that guaranteed equal opportunity for land ownership and economic independence.

After the convention, Cardozo’s career accelerated. A “handsome man, almost white in color . . . with . . . tall, portly, well-groomed figure and elaborately urbane manners” (Simkins and Woody), Cardozo played a central role in the real efforts to reconstruct American society along more democratic lines. In 1868 he declined the Republican nomination for lieutenant governor in the wake of white claims of Reconstruction “black supremacy.” Later that year he was elected secretary of state, making him the first black state official in South Carolina history, and he retained that position until 1872. In 1869 Cardozo was a delegate to the South Carolina labor convention and then briefly served as secretary of the advisory board of the state land commission, an agency created to redistribute confiscated land to freedmen and poor whites. In this capacity, he helped to reorganize its operations after a period of severe mismanagement and corruption. As secretary of state, he was given full responsibility for overseeing the land commission. In 1872 he successfully advocated for the immediate redistribution of land to settlers and produced the first comprehensive report on the agency’s financial activities. By the fall of 1872, owing in large part to Cardozo’s efforts, over 5,000 families—3,000 more than in 1871—had settled on tracts of land provided by the commission, one of the more radical achievements of the Reconstruction era.

In 1870, the same year that the federal census estimated his net worth at an impressive eight thousand dollars, Cardozo was elected president of the Grand Council of Union Leagues, an organization that worked to ensure Republican victories throughout the state. His civic activities included serving as president of the Greenville and Columbia Railroad, a charter member of the Columbia Street Railway Company, and a member of the Board of Trustees of the University of South Carolina. Some sources report that he enrolled in the university’s law school in October 1874; however, no evidence exists that he ever received a degree.

From 1871 to 1872 Cardozo was professor of Latin in Washington, D.C., at Howard University, where he was considered for the presidency in 1877. In 1872 and 1874 he was elected state treasurer, vowing to restore South Carolina’s credit. During his first term as treasurer he oversaw the allocation of more money than had been spent “for the education of the common people by the government of South Carolina from the Declaration of Independence to 1868, a period of ninety-two years” (Cardozo, The Finances of the State of South Carolina [1873], 11–12). In the words of one conservative newspaper editor, Cardozo was the “most respectable and honest of all the state officials.” Despite his longstanding reputation for scrupulous financial management, he was accused in 1875 of “misconduct and irregularity in office” for allegedly mishandling state bonds. Though he claimed reelection as treasurer in 1876, he officially resigned from the office on 11 April 1877. Subsequently tried and convicted for fraud by the Court of General Sessions for Richland County in November 1877, Cardozo was eventually pardoned by Democratic governor Wade Hampton before his sentence, two years in prison and a fine of four thousand dollars, was commuted.

Following the ascendancy of the new Democratic government and the final abandonment of Radical Reconstruction in 1877, Cardozo moved in 1878 to Washington, D.C., and secured a clerkship in the Treasury Department, which he held from 1878 to 1884. Returning to education in the last decades of his life, he served as principal of the Colored Preparatory High School from 1884 to 1891 and from 1891 to 1896 as principal of the M Street High School, where he instituted a comprehensive business curriculum. A prominent member of Washington’s elite black community until his death there, Cardozo was so revered by his peers, black and white, that a business high school opened in 1928 was named in his honor.

The Francis L. Cardozo Family Papers are held at the Library of Congress. Proceedings of the 1868 Constitutional Convention of South Carolina (Charleston, 1868) help to locate Cardozo’s ideas within the context of Reconstruction debates. The Twentieth Annual Report on the Educational Condition in Charleston, American Missionary Association (1866) contains Cardozo’s assessment of black education in the aftermath of the Civil War.

Foner, Eric. Reconstruction: America’s Unfinished Revolution, 1863–1877 (1988).

Holt, Thomas. Black over White: Negro Political Leadership in South Carolina during Reconstruction (1979).

Richardson, Joe M. “Francis L. Cardozo: Black Educator during Reconstruction.” Journal of Negro Education 48 (1979): 73–83.

Simkins, Francis, and Robert H. Woody. South Carolina during Reconstruction (1932).

Sweat, Edward F. “Francis L. Cardozo—Profile of Integrity in Reconstruction Politics.” Journal of Negro History 44 (1961): 217–232.

—TIMOTHY P. MCCARTHY

CARMICHAEL, STOKELY

CARMICHAEL, STOKELY(29 June 1941–15 Nov. 1998), civil rights leader, later known as Kwame Ture, was born Stokely Standiford Churchill Carmichael in Port-of-Spain, Trinidad, British West Indies, the son of Adolphus Carmichael, a carpenter, and Mabel (also listed as May) Charles Carmichael, a steamship line stewardess and domestic worker. When he was two, his parents immigrated to the United States with two of their daughters. He was raised by two aunts and a grandmother and attended British schools in Trinidad, where he was exposed to a colonial view of race that he was later to recall with anger. He followed his parents to Harlem at the age of eleven and the next year moved with them to a relatively prosperous neighborhood in the Bronx, where he became the only African American member of the Morris Park Dukes, a neighborhood gang. But although he participated in the street life of the gang, he had more serious interests. “They were reading funnies,” he recalled in an interview in 1967, “while I was trying to dig Darwin and Marx” (quoted in Parks, 80). A good student, he was accepted in the prestigious Bronx High School of Science. When he graduated in 1960 he was offered scholarships to several white universities, but a growing awareness of racial injustice led him to enroll in predominantly black Howard University in Washington, D.C. Impressed by the television coverage of the protesters at segregated lunch counters in the South, he had already begun to picket in New York City with members of the Congress of Racial Equality (CORE) before he entered college in the fall of 1960.

Carmichael became an activist while still in his first year at Howard, where he majored in philosophy. He answered an ad in the newsletter of the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC), a student desegregation and civil rights group, and joined the first of the interracial bus trips known as Freedom Rides organized in 1961 by CORE to challenge segregated public transportation in the South. He was arrested for the first time when the bus reached Mississippi. He was jailed frequently in subsequent Freedom Rides, once serving a forty-nine-day term in Mississippi’s Parchman Penitentiary.

After graduating in 1964, Carmichael joined SNCC full time and began organizing middle-class volunteers of both races to travel into the South to teach rural blacks and help them register to vote. From his headquarters in Lowndes County, Mississippi, he was credited with increasing the number of black voters of that county from 70 to 2,600. Lacking the support of either the Republican or the Democratic Party, he created the all-black Lowndes County Freedom Organization, which took as its logo a fierce black panther. Growing impatient with the willingness of black leaders to compromise, he led his organization to shift its goal from integration to black liberation. In May 1966 he was named chairman of SNCC.

In June of that year, after JAMES MEREDITH’s “March Against Fear” from Memphis to Jackson had been stopped when Meredith was shot, Carmichael was among those who continued the march. On his first day, he announced his militant stand: “The Negro is going to take what he deserves from the white man” (Sitkoff, 213). Carmichael was arrested for trespass when they set up camp in Greenwood, Mississippi, and after posting bond on 16 June he rejoined the protesters and made the speech that established him as one of the nation’s most articulate spokesmen for black militancy. Employing working-class Harlem speech (he was equally fluent in formal academic English), he shouted from the back of a truck, “This is the 27th time I’ve been arrested, and I ain’t going to jail no more. The only way we gonna stop them white men from whuppin’ us is to take over. We been saying freedom for six years and we ain’t got nothing. What we gonna start sayin’ now is Black Power!” (Oates, 400). The crowd took up the refrain, chanting the slogan over and over.

The term “Black Power” was not new with Carmichael—RICHARD WRIGHT had used it in reference to the anticolonialist movement in Africa, and ADAM CLAYTON POWELL JR. had used it in Harlem—but it created a sensation that day in Mississippi, and Carmichael instructed his staff that it was to be SNCC’s war cry for the rest of the march. The national press reported it widely as a threat of race war and an expression of separatism and “reverse racism.” ROY WILKINS, leader of the NAACP, condemned it as divisive, and MARTIN LUTHER KING JR. pleaded with Carmichael to abandon the slogan. But although King persuaded SNCC to drop the use of “Black Power” for the remainder of the march, the phrase swept the country. Carmichael always denied that the call for black power was a call to arms. “The goal of black self-determination and black self-identity—Black Power—is full participation in the decision-making processes affecting the lives of black people and the recognition of the virtues in themselves as black people,” he wrote in his 1967 book, written with Charles V. Hamilton, Black Power: The Politics of Liberation (47).

In August 1967 Carmichael left SNCC and accepted the post of prime minister of a black militant group formed by HUEY P. NEWTON and BOBBY SEALE in 1966, the Black Panther Party, which took its name from the symbol Carmichael had used in Mississippi. As its spokesman he called for the Southern Christian Leadership Conference (SCLC), the NAACP, and the Nation of Islam to work together for black equality. That year he traveled to Hanoi to address the North Vietnamese National Assembly and assure them of the solidarity of American blacks with the Vietnamese against American imperialism. In 1968 he married the famous South African singer Miriam Makeba; the couple had one child.

Carmichael remained with the Black Panthers for little more than a year, resigning because of the organization’s refusal to disavow the participation of white radicals, and in 1969 left America for Africa, where he made his home in Conakry, capital of the People’s Revolutionary Republic of Guinea. By then completely devoted to the cause of socialist world revolution emanating from a unified Africa, he became affiliated with the All-African People’s Revolutionary Party, a Marxist political party founded by Kwame Nkrumah, the exiled leader of Ghana then living in Guinea as a guest of its president Sekou Touré. Carmichael changed his name, in honor of his two heroes, to Kwame Ture, and toured U.S. colleges for several weeks each year speaking on behalf of the party and its mission of unifying the nations of Africa. Divorced in 1978, he married Guinean physician Marlyatou Barry; the couple had one son. His second marriage also ended in divorce.

During the 1980s Ture’s message of Pan-Africanism inspired little interest in the United States, and the attendance at his public appearances fell off. As Washington Post reporter Paula Span noted shortly before his death, “Back in the United States, there were those who felt Ture had marginalized himself, left the battlefield. His influence waned with his diminished visibility, and with the cultural and political changes in the country he’d left behind.” He also came under criticism for anti-Semitism because of his persistent attacks on Zionism. A collection of fourteen of his speeches and essays published in 1971, Stokely Speaks: Black Power Back to Pan-Africanism, included such inflammatory assertions as “The only good Zionist is a dead Zionist,” and was attacked in the press. The bulletin of the Anti-Defamation League of B’nai B’rith criticized his campus addresses, calling him “a disturbing, polarizing figure” who caused hostility between blacks and Jews.

In 1986, two years after the death of his patron Sekou Touré, Ture was arrested by the new military government on charges of subversive activity, but he was released three days later. Despite the continued fragmentation of Africa and the diminished influence of Marxism, he never lost his faith in the ultimate victory of the socialist revolution and the fall of American capitalism. To the last he always answered his telephone “Ready for the revolution,” a greeting he had used since the 1960s. In 1996 he was diagnosed with prostate cancer, with which he believed he had been deliberately infected by the FBI. Despite radiation treatment in Cuba and at New York’s Columbia-Presbyterian Medical Center during his last year, he died of that disease in Conakry.

Kwame Ture left a mixed legacy. His provocative rhetoric was widely opposed by black leadership: Martin Luther King Jr. decried his famous slogan as “an unfortunate choice of words,” and Roy Wilkins condemned his militant position as “the raging of race against race.” But Ture’s childhood friend Darcus Howe wrote of him in a column in The New Statesman (27 Nov. 1998), “He will be remembered by many as the figure who brought hundreds of thousands of us out of ignorance and illiteracy into the light of morning.”

Carmichael, Stokely, with Ekwueme Michael Thelwell. Ready for Revolution. The Life and Struggles of Stokely Carmichael (Kwame Ture) (2003).

Carson, Clayborne. In Struggle: SNCC and the Black Awakening of the 1960s (1981).

King, Martin Luther, Jr. Where Do We Go from Here: Chaos or Community? (1967).

Oates, Stephen B. Let the Trumpet Sound: The Life of Martin Luther King, Jr. (1982).

Parks, Gordon. “Whip of Black Power.” Life, 19 May 1967, 76–82.

Sitkoff, Harvard. The Struggle for Black Equality, 1954–1980 (1981).

Span, Paula. “The Undying Revolutionary.” Washington Post, 8 Apr. 1998.

Van Deburg, William L. Modern Black Nationalism: From Marcus Garvey to Louis Farrakhan (1997).

Obituary: New York Times, 16 Nov. 1998.

—DENNIS WEPMAN

CARSON, BEN

CARSON, BEN(18 Sept. 1951–), pediatric neurosurgeon, was born Benjamin Solomon Carson in Detroit, Michigan, the son of Robert Carson, a minister of a small Seventh-Day Adventist church, and Sonya Carson. His mother had attended school only up to the third grade and married at the age of thirteen; she was fifteen years younger than her husband. After his father deserted the family, eight-year-old Ben and his brother, Curtis, were left with their mother, who had no marketable skills. Sonya worked as a domestic when such jobs were available, and she struggled with bouts of depression, for which, at one point, she had herself admitted to a psychiatric hospital. Despite her disabilities, she became the biggest factor in determining Ben’s later success, which she and Ben attribute to divine intervention.

Except for two years in Boston, Ben grew up in a dangerous and impoverished neighborhood in Detroit. Initially, he did so poorly in school that by the fifth grade even he classified himself as “the class dummy.” In part, his difficulties resulted from a failure to detect his need for eyeglasses. Nevertheless, when Sonya noticed the poor academic performance of her two sons, she instituted insightful strategies, curtailing their play activities and television viewing and demanding that the boys read two books each week and write reports on them for her to review—despite the fact that she could barely read herself. (Later she, too, went on to college.) Her stern intervention was also accompanied by positive reinforcement. When she learned of Ben’s nascent interest in medicine, she said reassuringly, “Then, Bennie, you will be a doctor” (Carson, Gifted Hands, 27). Her parenting techniques catapulted Ben from the bottom of the fifth grade to the top of his seventh grade class.

Ben then became a normal teenager, desiring both stylish clothes and acceptance from his peers. As a result of this shift in his priorities, his grades plummeted from As to Cs, and he even confronted his mother angrily because she would not buy the fashionable clothes that he craved. She devised a scheme for him to manage the household expenses with her salary, saying that the remaining money could be used to buy the things he wanted. When Ben began this exercise, he was astounded and wondered how she made ends meet, because the money was gone before he had paid all the bills. Ben learned an invaluable lesson; he appreciated his mother’s tenacity, curtailed his sartorial demands, and focused once again on his studies.

As a teenager Ben had a volatile temper, and at fourteen he attempted to stab a friend with a pocketknife simply because the boy would not change the radio station. Ben believes that it was through divine providence that his knife struck only his friend’s belt buckle. This experience initiated another transformation in his life. He began to pray for help controlling his anger, he avoided trouble outside school, and he ended up graduating third in his class.

During Carson’s freshman year at Yale University, he writes, “I discovered I wasn’t that bright” (Gifted Hands, 73), and he wondered if he had what it would take to succeed in the highly competitive premed program. Aubrey Tompkins, the choir director of the Mt. Zion Seventh-Day Adventist Church, encouraged him and helped him regain his confidence. In retrospect, Carson wrote that “the church provided the stabilizing force I needed” (Think Big, 65). After receiving his BA in 1973, Carson entered the University of Michigan School of Medicine, where he studied with Dr. James Taren, a neurosurgeon and dean, who advised his students, when confronted with the choice of whether or not to operate, to “look at the alternatives if we do nothing” (Think Big, 65). This statement has resonated throughout Carson’s professional career as a neurosurgeon. Another of his teachers, Dr. George Udvarhelyi, impressed upon him the importance of understanding the patient as much as the patient’s diagnosis. Through this advice, Carson developed the gentle bedside manner of a good country doctor. In 1975 Carson married Lacena “Candy” Rustin; they subsequently had three sons.

Carson received his MD in 1977 and fulfilled his residency at Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine, where he was often mistaken for an orderly—despite the fact that he wore the white lab coat that should have identified him as a doctor. Carson was not only undaunted by such prejudice, he actually thrived on debunking racial stereotypes. From 1982 to 1983 he served as chief resident in neurosurgery at Sir Charles Gairdner Hospital in Australia before Dr. Donlin Long recommended and engineered his appointment as chief of pediatric neurosurgery at Johns Hopkins. At the time of his appointment, Carson was only thirty-three years old and already considered a rising star in his field.

Carson gained international renown and made medical history in 1987, when he led a surgical team of seventy people in a twenty-two-hour operation that successfully separated the seven-month-old Binder twins, who were joined at the skull. In 1994 he performed a similar operation on conjoined South African girls, one of whom died during the operation and the other two days later; three years later he successfully separated six-month-old Zambian boys. Performing approximately four hundred operations per year in his pediatric unit, Carson is often called upon to assist surgeons all over the world.

In July of 2003 Carson was an assisting surgeon in a widely publicized attempt to separate twenty-nine-year-old Iranian sisters, joined at the backs of their heads, who themselves decided that a fifty-fifty chance that one or neither would survive the operation was better than continuing to live in a conjoined state, where they could not pursue their individual and distinct interests. Following the failure of this operation and the deaths of both sisters, Carson determined not to perform any more such operations on adults.

In August 2002, Carson successfully underwent surgery himself for prostate cancer, which had not metastasized. Throughout this ordeal, just as in surgery with his patients, Ben Carson relied on his faith and the will of God to carry him through.

In addition to his practice, Carson has written numerous articles for medical journals; an autobiography, Gifted Hands: The Ben Carson Story (1990); and two motivational books, The Big Picture (1999) and Think Big (1992). He has been an outspoken champion of such issues as racial diversity, affirmative action, and health care reform. In 1994 Carson and his wife founded the Carson Scholars Fund, which offers scholarships to encourage children to take an interest in science, math, and technology and to balance the attention given to sports and entertainment with an appreciation of academic achievement.

Carson, Ben. The Big Picture: Getting Perspective on What’s Really Important in Life (1999).

_______. Gifted Hands: The Ben Carson Story (1990).

_______. Think Big: Unleashing Your Potential for Excellence (1992).

—THOMAS O. EDWARDS

CARTER, EUNICE HUNTON