DADDY GRACE.

DADDY GRACE. DADDY GRACE.

DADDY GRACE.See Grace, Charles Emmanuel.

DANDRIDGE, DOROTHY

DANDRIDGE, DOROTHY(9 Nov. 1922–8 Sept. 1965), movie actress and singer, was born Dorothy Jean Dandridge in Cleveland, Ohio, the daughter of Cyril Dandridge, a Baptist minister, and Ruby Jean Butler, a movie and radio comedian. Dorothy, a child entertainer, was in and out of school while her mother directed and choreographed her two children in a sister vaudeville act. The “Wonder Kids” performed in Cleveland’s black Baptist churches and toured throughout the South for five years.

In the early 1930s Ruby, whose husband had left her just before Dorothy’s birth, moved her family to the Watts section of Los Angeles, California, to further their careers in show business. The Wonder Kids recruited another girl, Etta Jones, and formed a singing group called the Dandridge Sisters. In 1937 the act was sold to Warner Bros, for a movie called A Day at the Races. The Dandridge Sisters also made appearances at the Cotton Club in Harlem, New York, and toured with DUKE ELLINGTON, CAB CALLOWAY, and Jimmie Lunceford.

The outbreak of World War II interrupted the Dandridge Sisters’ international tour and initiated their demise. Around this time Dorothy Dandridge met Harold Nicholas, who was one of the famous dancing Nicholas Brothers, and in 1942 they were married. In 1945 Dandridge’s only child was born, and Harold immediately deserted his family because their child was severely brain damaged. In later years Dandridge teamed up with both Rose Kennedy and Jacqueline Kennedy Onassis in an effort to help the mentally challenged under the auspices of the Joseph P. Kennedy Jr. Foundation.

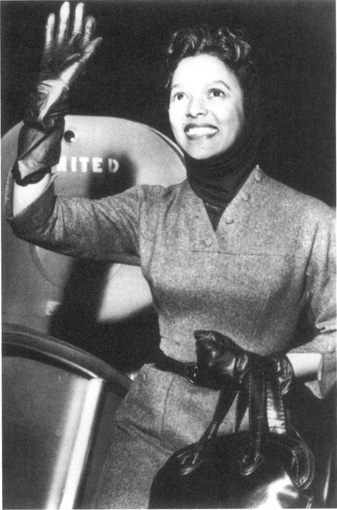

Dorothy Dandridge, the first black actor nominated for an Academy Award in a starring role, in 1955. Library of Congress

Dandridge’s first important film role was Queen of the Jungle in Columbia Pictures’ Tarzan’s Peril (1951). Dore Schary of MGM then hired Dandridge to play a compassionate black schoolteacher in Bright Road, costarring HARRY BELAFONTE. During this time, Dandridge began her nightclub and concert engagements. In 1951 bandleader Desi Arnaz agreed to temporarily employ Dandridge in his act at the Hollywood Mocombo. This appearance compelled Maurice Winnick, a British theatrical impresario, to offer Dandridge an engagement at the Cafe de Paris in London. The next year the Chase Hotel in St. Louis, Missouri, which had never employed a black performer to entertain in its dining room, booked her for an engagement. Dandridge informed the management that she would not perform unless blacks were allowed to obtain reservations and be permitted to use the main entrance. These conditions were agreed upon by the hotel management, and a table was reserved for black members of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People on opening night.

The most memorable and award-winning screen performance for Dandridge was in the title role of Carmen Jones (1954) produced by Otto Preminger in association with Twentieth Century-Fox. Carmen Jones costarred PEARL BAILEY and Belafonte. In 1955 Dandridge became the first black actor to be nominated for an Oscar in a starring role and the first black woman to take part in the Academy Awards show, presenting the Oscar for film editing. Dandridge also won a Golden Globe Award of Merit for Outstanding Achievement for the best performance by an actress in 1959. Dandridge’s international acclaim led Twentieth Century-Fox to offer her a three-year contract that was the first and most ambitious offer given to a black performer by that studio. During the same year, Dandridge became the first black headliner to appear at the Waldorf-Astoria Hotel in New York City.

During the 1950s Dandridge starred in several films for Twentieth Century-Fox, Columbia Pictures, and foreign film companies. Island in the Sun (1957), with James Mason, Joan Fontaine, and Belafonte, was Hollywood’s first major interracial film and was a box office success. In Tamango (1959), Dandridge portrayed an African slave in love with a white ship captain, played by Austrian actor Curt Jurgens. She costarred with SIDNEY POITIER in Porgy and Bess (1959). In addition to her film credits, Dandridge appeared on several television shows during the 1950s including “The Mike Douglas Show,” “The Steve Allen Show,” and “The Ed Sullivan Show.” In November 1954 she also appeared on the cover of Life magazine, making history as the first black to do so.

In 1959 Dandridge married Jack Dennison (or Denison), a white restaurateur and nightclub owner; the marriage ended in divorce in 1962. In 1961 Dandridge costarred in a film with Trevor Howard, titled Malaga. Dandridge’s last concert appearances included engagements in Puerto Rico and Tokyo. Her death was reported as the result of acute drug intoxication, an ingestion of the antidepressant Tofranil, at her apartment in West Hollywood, California.

A retrospective article in the Los Angeles Herald Examiner lamented that Dandridge’s passing meant “the ceasing of exquisite music. . . she walked in beauty. . . regal as a queen.” In her lifetime Dandridge was named by a committee of photographers as one of the five most beautiful women in the world. She was an international celebrity who believed in breaking down barriers to achieve racial equality. Dandridge realized that a black male could become a big star without romantic roles, but a sexy black actress like her was limited because the American public was not ready for interracial romance on the screen. On 20 February 1977 Dandridge, the first black leading lady, was posthumously inducted into the Black Filmmakers Hall of Fame at the annual Oscar Micheaux Awards presentation in Oakland, California. Vivian Dandridge, her sister, accepted the award. In December 1983 Belafonte, Poitier, and others petitioned to secure a star on the Hollywood Walk of Fame for Dandridge, a trailblazer for blacks in the American film industry.

There is a clippings file in the Billy Rose Theatre Collection, New York Public Library for the Performing Arts, Lincoln Center.

Dandridge, Dorothy, with Earl Conrad. Everything and Nothing: The Dorothy Dandridge Tragedy (1970).

Agan, Patrick. The Decline and Fall of the Love Goddesses (1979).

Bogle, Donald. Dorothy Dandridge: A Biography (1999).

Mills, Earl. Dorothy Dandridge (1999).

Obituary: New York Times, 8 Sept. 1965.

—SAMUEL CHRISTIAN

DAVIS, ANGELA YVONNE

DAVIS, ANGELA YVONNE(26 Jan. 1944–), radical activist, scholar, and prison abolitionist, was born in Birmingham, Alabama, to Frank and Sally Davis. Her father, a former teacher, owned a service station, and her mother was a schoolteacher. Both had ties to the NAACP and friends in numerous radical groups, including the Communist Party. When Angela was four years old, her family moved from a housing project to a white neighborhood across town. The experience of being the only African Americans surrounded by hostile whites taught Davis at a young age the ravages of racism. Indeed, during the mid- to late 1940s, as more black families began moving into the area, white residents responded with violence, and the neighborhood took on the unenviable nickname “Dynamite Hill.” Davis’s racial consciousness was further sharpened by attending the city’s vastly inferior segregated public schools.

As a junior at Birmingham’s Parker High School, at the age of fourteen, Davis applied to two programs that could get her out of Alabama: early entrance to Fisk University, where she wanted to pursue a degree in medicine, and a program sponsored by the American Friends Service Committee to attend an integrated high school in the North. After much deliberation and with the encouragement of her parents, she opted for the latter, and in 1959 she moved to New York City. Davis lived with a leftist Episcopalian priest and his wife in Brooklyn and each day went to the Elisabeth Irwin High School on the edge of Greenwich Village. Stimulated intellectually and politically, she read the Communist Manifesto for the first time and later recalled that it hit her “like a bolt of lightning” (Davis, 109). During this time Davis also began going to meetings of an organization called Advance, a Marxist-Leninist student group affiliated with the Communist Party, as well as attending the lectures of the historian Herbert Aptheker at the American Institute for Marxist Studies.

Although her interest in radical theory did not wane during her college years at Brandeis University in Waltham, Massachusetts, it was tempered by what she viewed as the complacency of the student body there. One of only three African Americans in her freshman class in the fall of 1961, Davis often felt alienated and alone, but she eventually befriended a handful of international students. In the midst of white middle-and upper-class political apathy, she forged ahead in her own pursuit of knowledge and experience outside the confines of Brandeis. During the summer of 1962 she traveled to Helsinki, Finland, to participate in the Eighth World Festival for Youth and Students. She spent 1963–1964, her junior year, in France and, upon her return, began an intense intellectual relationship with the German-born Marxist philosopher Herbert Marcuse.

After receiving a BA in French Literature in 1965, Davis entered the University of Frankfurt in West Germany to pursue a PhD in Philosophy. During her two years there, she followed a pattern that marked her entire career, combining intensive study with political activism. In Frankfurt, Davis joined numerous socialist student groups and regularly participated in protests and demonstrations. But as she watched, from across the Atlantic, the civil rights movement in the United States take a dramatic turn away from nonviolence and toward black power and black nationalism, she yearned to be involved in what she referred to in her autobiography as the Black Liberation Movement. Davis left West Germany for the University of California, San Diego, where Marcuse was teaching. There she worked with the Black Panther Political Party (which was not affiliated with the Black Panther Party for Self-Defense, led by ELDRIDGE CLEAVER, BOBBY SEALE, and HUEY NEWTON) and a fledgling Los Angeles branch of the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC). In 1969, however, she left both groups after being frustrated by their ideological infighting, sexism, and anticommunism and officially joined the Communist Party. She became a member of a cell in Los Angeles known as the Che-Lumumba Club (named after Che Guevara, the Latin American revolutionary, and Patrice Lumumba, the radical Congolese independence leader).

Davis’s activism made her well known among southern Californian leftists, but she did not achieve national or international attention until the late 1960s, when two events catapulted her into the spotlight. Indeed, they would secure for Davis the near mythic status, depending on one’s political perspective, of an iconic hero or the country’s most dangerous subversive. The first episode occurred in 1969, when the Board of Regents of the University of California, supported by Governor Ronald Reagan, fired Davis from her teaching position at University of California at Los Angeles, where she had received a non-tenure-track appointment in the philosophy department while completing her PhD. They cited a 1949 law prohibiting the hiring of Communists in the state university system. After months of legal wrangling, the board finally voted in June 1970 not to extend her appointment to a second year. Davis filed an appeal, but the controversy was soon overshadowed by the defining moment in her life as a political activist, the Soledad Brothers case.

In February 1970 George Jackson, John Clutchette, and Fleeta Drumgo, three African American inmates at the Soledad prison in north-central California, had been indicted for the murder of a white prison guard. The lack of evidence or witnesses to the crime, which had occurred during a melee inside prison walls, led many to believe that this was yet another example of the entrenched racism within the justice system, a perversion of the very system that was designed to protect American citizens, and a frame-up. Angela Davis quickly became a leader in the Soledad Brothers Defense Committee and soon developed a close relationship with Jackson, the most visible of the three, whose letters from prison would be published in 1971. On 7 August 1970, Jackson’s younger brother Jonathan entered a courtroom in Marin County, pulled out a machine gun, and allegedly demanded the release of the Soledad Brothers. With the help of three San Quentin inmates who were present in the courtroom, Jackson took the judge and four other people hostage. Before they could get away, guards opened fire; in the ensuing gun battle Jonathan Jackson, two prisoners, and the judge were killed.

Less than ten days later a Marin County judge issued a warrant for the arrest of Angela Davis on one count of murder and five counts of kidnapping. According to the warrant, two of the guns used in the escape attempt were registered to Davis, which made her an accomplice. Thus began a high-profile manhunt, which included Davis’s appearance on the FBI’s Ten Most Wanted list and a cavalcade of press coverage, in which she was nearly universally described as a “black militant,” “black radical,” or “militant black Communist.” She was finally caught in a Manhattan Howard Johnson’s on 13 October 1970 and imprisoned in a Greenwich Village jail for women. Davis was soon extradited to California, where her trial began in January 1971. Eighteen months later, during which time an international movement to “Free Angela Davis” flourished, she was acquitted on all charges.

Although Angela Davis would never again reach this level of notoriety, she was instantly enshrined in the pantheon of legendary African American freedom fighters, and she continued to wage a political and intellectual battle against all forms of inequality for decades after her imprisonment. In the classroom, as a professor at San Francisco State and, beginning in 1991, the University of California, Santa Cruz; on the campaign trail, as a candidate for vice president on the Communist Party ticket in 1980 and 1984; and on the lecture circuit, as an outspoken critic of the U.S. prison system and its basis and role in the institutional perpetuation of racial and economic inequality, Davis remained a vibrant and vital voice on the political left during a period of ascendancy of conservatism in the United States.

Davis published numerous books and articles, including her own autobiography in 1974 and a study of the interconnectedness of gender, racial, and economic oppression, Women, Race, & Class, in 1981. During the 1990s she appeared at rallies and demonstrations across the country, on issues ranging from the Million Man March, to the campaign to free Mumia Abu-Jamal from prison, to the ballot initiative against affirmative action in California. By the early years of the twenty-first century Angela Davis was leading the fight against what she termed the “prison industrial complex,” calling for the abolition, rather than merely the reform, of prisons in the United States. Ever a lightning rod for controversy and a voice of true radicalism, this struggle was no less compelling for its unpopularity—something to which Davis had long been accustomed.

Davis, Angela. Angela Davis: An Autobiography (1974).

Aptheker, Bettina. Morning Breaks: The Trial of Angela Davis (1975).

Gates, Henry Louis, ed. Bearing Witness: Selections from African American Autobiography in the Twentieth Century (1991).

—STACY BRAUKMAN

DAVIS, BENJAMIN JEFFERSON

DAVIS, BENJAMIN JEFFERSON(8 Sept. 1903–22 Aug. 1964), Communist Party leader, was born in Dawson, Georgia, the son of Benjamin Davis Sr., a publisher and businessman, and Willa Porter. Davis was educated as a secondaryschool student at Morehouse in Atlanta. He entered Amherst College in 1922 and graduated in 1925. At Amherst he starred on the football team and pursued lifelong interests in tennis and the violin. He then attended Harvard Law School, from which he graduated in 1928. He was a rarity—an African American from an affluent family in the Deep South; however, his wealth did not spare him the indignities of racial segregation. While still a student at Amherst, he was arrested in Atlanta for sitting in the white section of a trolley car. Only the intervention of his influential father prevented his being jailed. As he noted subsequently, it was the horror of Jim Crow—the complex of racial segregation, lynchings, and police brutality—that pushed him toward the political left.

After graduating from Harvard, Davis was well on his way to becoming a member of the black bourgeoisie. He worked for a period at a black-owned newspaper, the Baltimore Afro-American, and in Chicago with W. B. Ziff, who arranged advertising for the black press. He then returned to Georgia, where he passed the bar examination and opened a law practice.

At this point an incident occurred that led to Davis’s joining the Communist Party (CP). ANGELO HERNDON, a young Communist in Georgia, was arrested under a slave insurrection statute after leading a militant demonstration demanding relief for the poor. William Patterson, a black lawyer and Communist who led the International Labor Defense, recruited Davis to handle Herndon’s case. Through discussions with his client, Davis decided to join the party in 1933.

As Davis was joining the CP, those African Americans who could vote were in the process of making a transition from voting for Republicans to voting for the Democratic party of Franklin D. Roosevelt. The GOP—particularly in the South, where Davis’s father was a Republican leader—was pursuing a “lily-white” strategy that involved distancing itself from African Americans, who had been one of its staunchest bases of support; simultaneously, Roosevelt’s “New Deal” promised relief from the ravages of the Great Depression.

Davis did not favor the Democrats, because in the South they continued to lift the banner of Jim Crow. His joining the CP was not unusual, given the times: many prominent African American intellectuals of that era—LANGSTON HUGHES and PAUL ROBESON, for example—worked closely with the Communists, not least because theirs was one of the few political parties that stood firmly in favor of racial equality. Moreover, the Soviet Union and the Communist International, which it sponsored—unlike the United States and its European allies—stood firmly in favor of the decolonization of Africa. Davis felt that capitalism was inextricably tied to the slave trade, slavery, and racism itself, and that socialism was the true path to equality.

Davis handled the trial of Herndon, and after the case went to the U.S. Supreme Court, with another lawyer dealing with the appeal, his client was freed. Davis went on to serve as a lawyer in the case of the SCOTTSBORO BOYS, African American youths charged falsely with the rape of two white women. They too were eventually freed because of decisions by the high court—after many years and many appeals—but Alabama then retried and convicted them.

Threats on Davis’s life and the CP’s desire to provide a more prominent role for him led to his moving to New York City in the mid-1930s. There he worked as journalist and editor with a succession of Communist journals, including the Harlem Liberator, the Negro Liberator, and the Daily Worker. At that last paper, he worked closely with the budding novelist RICHARD WRIGHT, with whom he shared a party cell; in this Communist organizational unit, Davis had the opportunity to comment on and shape some of Wright’s earliest writings.

At its zenith during the 1930s, the Communist Party in New York State had about twenty-seven thousand members, of whom about two thousand were African Americans. Davis played a key role in the founding of the National Negro Congress, which had been initiated by the Communists; for a while the NNC included leading members of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP), the labor leader A. PHILIP RANDOLPH, and the Reverend ADAM CLAYTON POWELL JR.

Davis developed a close political relationship with Powell, a New York City councilman. When Powell moved on to represent Harlem in the U.S. House of Representatives, he anointed Davis as his successor. Davis was duly elected in 1943 and received a broad range of support, particularly from noted black artists and athletes such as BILLIE HOLIDAY, LENA HORNE, JOE LOUIS, Teddy Wilson, and COUNT BASIE. He received such support for a number of reasons. There were his qualifications—lawyer, journalist, powerful orator, and organizer. There was also the fact that at this time both the Democrats—who were influenced heavily by white Southerners hostile to desegregation—and the Republicans were not attractive alternatives for African Americans. Moreover, in 1943 the United States was allied with the Soviet Union, which had led to a decline in anticommunism, a tendency that in any event was never strong among African Americans.

On the city council Davis fought for rent control, keeping transit fares low, and raising pay for teachers, among other measures. He received substantial support not only from African Americans but also from many Jewish Americans, who appreciated his support for the formation of the state of Israel and for trade unions. In 1945 he was reelected by an even larger margin of victory. By the time he ran for reelection in 1949, however, the political climate had changed dramatically. The wartime alliance with the USSR had ended, and in its place there was a cold war internationally and a “Red Scare” domestically. Supporting a Communist now carried a heavy political price; simultaneously, many of Davis’s African American supporters were now being wooed by the Democratic administration of President Harry Truman.

During his race for the presidency in 1948, Truman was challenged from the left by Henry Wallace, nominated by the Progressive Party. Because Wallace received the support of such African American luminaries as Paul Robeson and W. E. B. DU BOIS, there was fear among some Democrats that Truman’s support from black voters would be eroded; in a close race this could mean victory for Republican candidate Thomas Dewey. Furthermore, Truman found it difficult to portray his nation as a paragon of human rights in its cold war struggle with the Soviet Union when blacks were treated like third-class citizens. Those pressures led Truman to put forward a civil rights platform in 1948 that outstripped the efforts of his predecessors in the White House. The Democrats succeeded in helping to undermine electoral support for Wallace and for Davis. Not only was Davis defeated in his race for reelection to the city council in 1949; he was also tried and convicted, along with ten other Communist leaders, of violating the Smith Act, which made the teaching or propagation of Marxism-Leninism a crime. After the U.S. Supreme Court in 1951 upheld these convictions in Dennis v. United States, Davis was jailed in federal prison in Terre Haute, Indiana, from 1951 to 1955. While there, he filed suit against prison segregation; Davis v. Brownell, coming in the wake of the 1954 High Court decision invalidating racial segregation in schools (Brown v. Board of Education), led directly to the curbing of segregation in federal prisons. After his release from prison, Davis married Nina Stamler, who also had ties to the organized left; they had one child, a daughter.

Davis’s final years with the CP were filled with tumult. In 1956, in the wake of the Soviet intervention in Hungary, the revelations about Stalin’s brutal rule aired at the Twentieth Congress of the Soviet Communist Party, and the Suez War, turmoil erupted in the U.S. party. Davis was a leader of the “hardline” faction that resisted moves toward radical change spearheaded by “reformers.” Some among the latter faction wanted the Communists to merge with other leftist parties and entities and become a “social democratic” organization, akin to the Socialist Party of France; others did not want the Party to be identified so closely with Moscow. There were those who disagreed with Davis’s opposition to the actions of Israel, Britain, and France during the Suez War. Some felt that Davis’s acceptance of the indictment of Stalin was not sufficiently enthusiastic; still others thought that Davis and his ideological allies should not have backed the Soviet intervention in Hungary. These internal party squabbles were exacerbated by the counterintelligence program of the Federal Bureau of Investigation that was designed, in part, to disrupt the party and ensure that it would play no role in the nascent civil rights movement.

When MARTIN LUTHER KING JR., the Atlanta minister and civil rights activist, was stabbed by a crazed assailant in New York City in 1958, Davis rushed to the hospital and provided blood for him. The Davis-King tie led J. Edgar Hoover to increase the FBI’s surveillance of the civil rights movement. But as the civil rights movement was blooming, the Communist Party was weakening. Nevertheless, during the last years of his life Davis became a significant and frequent presence on college campuses, as students resisted bans on Communist speakers by inviting him to lecture. The struggle to invite Communists to speak on campus was a significant factor in generating the student activism of the 1960s, from the City College of New York to the University of California at Berkeley.

By the time Davis died in New York City, the Party was a shadow of its former self. His life showed, however, that African Americans denied equality ineluctably would opt for more radical solutions, and this in turn helped to spur civil rights reforms. African slaves had been an early form of capital and a factor in the evolution of capitalism; that a descendant of African slaves became such a staunch opponent of capitalism was, in that sense, the closing of a historical circle.

Davis’s papers, including the unexpurgated version of his memoir, are at the Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture of the New York Public Library.

Davis, Benjamin Jefferson. Communist Councilman from Harlem: Autobiographical Notes Written in a Federal Penitentiary (1969).

Foster, William Z. History of the Communist Party of the United States (1968).

Herndon, Angelo. Let Me Live (1937).

Horne, Gerald. Black Liberation/Red Scare: Ben Davis and the Communist Party (1994).

Obituaries: New York Times, 24 Aug. 1967; Worker, 1 Sept. 1967.

—GERALD HORNE

DAVIS, BENJAMIN O., JR.

DAVIS, BENJAMIN O., JR.(18 Dec. 1912–4 July 2002), was born in Washington, D.C., the son of the U.S. army’s first black general, BENJAMIN O. DAVIS SR., and his wife, Elnora Dickinson. Davis spent most of his childhood living on different military bases. By the time he entered high school, his family had settled in Cleveland, Ohio, where he attended a predominantly white school. At his high school, he began to prove his leadership ability, winning elections for class president. After high school, he enrolled in Cleveland’s Case Western Reserve University and later the University of Chicago, before he was accepted in 1932, through the influence of the congressman OSCAR DEPRIEST, into the United States Military Academy at West Point.

At West Point, which discouraged black cadets from applying at the time, Davis faced a hostile environment and routine exclusion by his peers. His classmates shunned him and only talked to him when it was absolutely necessary. No one roomed with him, and he ate all of his meals in silence. Although he faced less humiliation, perhaps, than the black West Point cadets before him, such as the academy’s first black graduate, HENRY O. FLIPPER, Davis remembered his four difficult years at West Point as a time of solitude and loneliness that, in spite of its struggle, prepared him for life in and outside of the military. The anonymously written statement about Davis in the 1936 Howitzer, the West Point yearbook, alludes obliquely and evocatively to his experience and presages his later success, “The courage, tenacity, and intelligence with which he conquered a problem incomparably more difficult than Plebe year won for him the sincere admiration of his classmates, and his singleminded determination to continue in his chosen career cannot fail to inspire respect wherever fortune may lead him.” His endurance and subsequent success in the military permanently opened the doors of the prestigious military academy to African Americans.

Benjamin O. Davis Jr., shown here in training as one of the renowned Tuskegee Airmen, led the first regiment of African American pilots. Library of Congress

Davis graduated in the top 15 percent of his class, becoming one of the two African American line officers in the U.S. Army. The other was his father. Shortly after his graduation from West Point, Davis married Agatha Scott. Davis was commissioned as a second lieutenant upon graduation and, because of his high class standing, should have been able to choose which branch of the military he wanted to join. But when he applied to be an officer in the Army Air Corps, he was denied. The military was not ready to send a black officer to lead an all-white squadron. Instead, he was assigned to the all-black Twenty-fourth Infantry Regiment at the segregated Fort Benning Army Base and charged with a variety of inconsequential duties. He was even barred from the officers club at Fort Benning, an insult he later described as one of the worst he suffered during his service in the military.

In 1940, as the U.S. prepared for World War II, there was growing public support for increased African American participation in the war. In an effort to address those concerns and simultaneously reach out to African American citizens as he prepared for the upcoming election, President Roosevelt promoted Benjamin O. Davis Sr. to brigadier general, the highest post ever held by any African American in the U.S. Army. He also established a training program for black pilots at Tuskegee Institute (now Tuskegee University) in Alabama that prepared African Americans to join the Air Corps on an experimental basis. Davis entered this program with eleven other officers, a group that later attracted national attention and became known in history as the Tuskegee Airmen. During the program, Davis became the first black officer to fly solo in an army aircraft, and he received his wings in March 1942. About a year later, with the rank of lieutenant colonel, Davis was charged with leading the first African American regiment of pilots, the 99th Pursuit Squadron. Although he and the unit he commanded felt prepared to advance to the frontlines of battle, some senior military officers discouraged the idea of blacks fighting in the war, believing their tactical and judgmental abilities were inferior, and the 99th was assigned routine non-combat missions in North Africa. In Washington hearings, Davis fiercely defended his men before both Pentagon and War Department authorities.

Near the end of 1943, Davis was promoted to colonel and assigned to a larger black unit, the 332nd Fighter Group, commonly called the Red Tails. With the 332nd, Davis arrived in Ramitelli, Italy, in January 1944, where his unit set out to disprove the widely accepted notion that blacks were inferior soldiers and airmen. Upgraded from the P-40 War Hawk aircraft the unit had flown in North Africa to the highly sophisticated P-47 Thunderbolt and P-41 Mustang fighter planes, on 9 June 1944, the unit accomplished its most noted military mission. Escorting B-24 bombers to targets in Munich, Germany, Davis led thirty-nine Thunderbolts in a battle with one hundred German Luftwaffe planes that resulted in the downing of six German planes. Following this action, Davis was awarded the Distinguished Flying Cross for leadership and bravery.

Under the command of Colonel Davis, his squadron carried out more than 15,000 missions, shot down 111 enemy aircraft, and destroyed another 150 on the ground, losing only 66 aircraft of their own. More remarkably, Davis’s unit carried out 200 successful escort missions without a single casualty. In a highly classified report issued shortly after the war, U.S. General George Marshall declared that black soldiers were just as capable of fighting, and equally entitled to serve their country, as white soldiers.

After the war, President Truman, impressed and influenced by the shining performance of Davis and his unit, issued Executive Order 9981 requiring the integration of the armed forces. Davis was appointed to posts at the Pentagon and served again as Chief of Staff in the Korean War, when he led an integrated unit. In 1954 he was promoted to brigadier general and in 1965 earned the three stars of lieutenant general. Davis was the first African American in any branch of the military to climb to that rank. He later served in the Philippines as commander of the Thirteenth Air Force, followed by a position as commander of the United States Strike Command in Florida. He retired in 1970 after leading the Thirteenth Air Force unit in Vietnam. Other military decorations include the Silver Star, Legion of Merit with two oak leaf clusters, the Air Medal with four oak leaf clusters, the Air Force Commendation Medal with two oak leaf clusters, and the Philippine Legion of Honor.

After his retirement from the military, Davis became director of public safety in Cleveland under that city’s first black mayor, Carl Stokes, though Davis soon quit because he could not abide the deal-making that occurred in municipal government and his by-the-book military style clashed with Stokes’s tolerance for civil disobedience exhibited by some black extremist groups. He later accepted a position with the Department of Transportation as Assistant Secretary of Transportation for Environment and Safety, where he directed the bureau’s anti-hijacking and anti-theft initiatives. He was instrumental in passing the 55 miles per hour speed limit set to save lives and gas. In 1998 President Clinton promoted Davis to full general.

Benjamin O. Davis Jr.’s rise to prominence followed in the remarkable path of his father’s career accomplishments. But his clear sense of purpose, evidenced by a record of professional advances in spite of blatant racism and legalized segregation, tell the story of a soldier not only inspired by his father’s career, but also determined to triumph on his own over all the odds stacked against him. Davis became one of the earliest notably honored African American military officers, breaking down racial barriers with honor, discipline, and an unflinching will.

Davis, Benjamin O., Jr. Benjamin O. Davis, Jr. American: An Autobiography (2000).

Marvis, B., and Nathan I. Huggins, eds., Benjamin Davis, Sr. and Benjamin Davis, Jr.: Military Leaders. (1996).

Obituary: New York Times, 7 July 2002.

—TANU T. HENRY

DAVIS, BENJAMIN OLIVER, SR.

DAVIS, BENJAMIN OLIVER, SR.(28 May 1880–26 Nov. 1970), U.S. Army officer, was born in Washington, D.C., the youngest of three children of Louis Patrick Henry Davis, a messenger for the U.S. Department of the Interior, and Henrietta Stewart, a nurse. Benjamin attended the Lucretia Mott School, one of Washington’s few integrated schools, and then the segregated M Street High School. Impressed in his interactions with Civil War veterans and black cavalrymen, Benjamin joined the M Street Cadet Corps, earning a commission in the all-black unit of the National Guard for his senior year.

General Benjamin O. Davis Sr. surveys operations in France, 1944. © CORBIS

Although he had taken courses at Howard University during his senior year of high school, and despite his parent’s objections, Davis chose a military career over college. He enlisted during the Spanish-American War in 1898 and joined the all-black Eighth U.S. Volunteer Infantry in Chickamauga, Georgia. A year later Davis reenlisted in the regular army. He served with the all-black Ninth Cavalry in Fort Duchesne, Utah, and quickly advanced to sergeant major, the highest rank for an enlisted soldier. In 1901 he underwent two weeks of officers’ exams, becoming, along with John E. Green, one of two black candidates to earn a commission at a time when Charles Young (West Point class of 1889) was the only African American officer in the U.S. armed forces. Other than Young, West Point’s only other black graduates, HENRY O. FLIPPER (class of 1877) and John Alexander (class of 1887), were, respectively, dishonorably discharged and dead. The next African American to graduate from West Point was Davis’s son, in 1936.

Davis’s first service as a commissioned officer was with the Ninth Cavalry in the Philippines, after which he was transferred to the Tenth Cavalry in Fort Washakie, Wyoming. He returned to Washington in 1902 to marry his childhood friend Elnora Dickerson. In 1905, following the birth of the couple’s first child, Olive, and his promotion to first lieutenant, Davis was made professor of military science and tactics at Wilberforce College in Ohio. After serving as military attaché to Liberia from 1909 to 1911, Davis was reassigned to the Ninth Cavalry at Fort D. A. Russell, Wyoming. Davis’s next detail, patrolling the United States-Mexican border in Arizona, necessitated sending his family to Washington within a year of the birth of his son, BENJAMIN O. DAVIS JR., in 1912. Following his promotion to captain in 1915, Davis returned to Wilberforce and to family life. The reunion, however, was short-lived; Elnora died in 1916 several days after the birth of their third child, Elnora.

When Davis was assigned the command of a supply troop in the Philippines in 1917, he sent his children to live with his parents in Washington. Two years later he married Sadie Overton, a Wilberforce teacher. After World War I, Davis, now a lieutenant colonel, taught at Tuskegee Institute in Alabama from 1920 to 1924. His next assignment was as instructor of the 372nd Infantry of the Ohio National Guard, a newly reorganized all-black unit. After four years, he was again transferred to Wilberforce for a year.

Davis became increasingly frustrated with teaching posts that undervalued his expertise and with assignments incommensurate with his rank. While the army routinely promoted Davis, he was assigned to noncombat positions, where he would not be in command of white personnel. He had spent World War I far away from the action and was repeatedly denied opportunities for more active duty. “I am getting to the point where I am beginning to believe that I’ve been kept as far in the background as possible,” Davis wrote to Sadie in 1920 (Fletcher, 54). Adding to his dissatisfaction was the social ostracism the Davises encountered from other military families. Davis was certainly aware that, in 1920 alone, more than seventy black World War I veterans had been lynched.

In 1930 Davis was promoted to colonel, becoming not only the highest ranking African American soldier in U.S. history, but—because John Green had retired in 1929—the only black officer in the U.S. Army. Despite repeated efforts to land a leadership position, Davis was reassigned to the Tuskegee classroom from 1930 to 1937. Davis’s first high-profile appointment as colonel—escorting mothers and widows of slain World War I soldiers to European cemeteries in the summers of 1930 through 1933—was the result of self-promotion. “Let a colored officer,” he successfully lobbied, “look after colored gold star mothers. . . . As you know I have traveled over the battlefields. I have a speaking knowledge of French” (Fletcher, 71). After another brief transfer to Wilberforce, Davis was finally put in charge of troops in 1938, when he was appointed regimental commander and instructor of the all-black 369th National Guard Infantry in New York City. Davis spearheaded the conversion of this service unit to an antiaircraft regiment, a move received by the black community as an indication that blacks could and should serve in all branches of the military.

In October 1940 Davis was promoted to brigadier general, becoming the first African American general. The timing of Davis’s appointment, by President Franklin D. Roosevelt, just days before the 1940 presidential election, reflects pressure from African American leaders. When Davis’s name did not appear on the list of proposed promotions circulated in September, the African American press responded—“Pres. Appoints 84 Generals, Ignores Col Davis” headlined the New York Age.

Roosevelt had signed the Selective Training and Service Act (1940), establishing the first peacetime draft in U.S. history, and although it included an antidiscrimination clause and the potential for expanded roles for African American soldiers, the legislation maintained segregation. Agitation by African American leaders, especially A. PHILIP RANDOLPH, helped secure Davis’s promotion and other changes, including the establishment of a flight training program at Tuskegee (launched in January 1941), the appointment of Judge WILLIAM HENRY HASTIE as civilian aide to the Secretary of War, and the inclusion of an African American on the Selective Service board.

Davis retired in June 1941 but was immediately recalled to active duty and assigned to the Office of the Inspector General in Washington, D.C., as an adviser on racial matters. As was often the case, racial discrimination began close to home. Davis arrived at his new office to find two colonels refusing to make room for his desk. Because there were no facilities for blacks at the state department, Davis ate lunch at his desk while he worked to support the promotion and improve the morale of black soldiers. Davis investigated complaints of racial discrimination, including the assignment of inferior officers to black units, the banning of black soldiers from army base facilities, and incidents of racial violence. Although appointed a member of the War Department’s Advisory Committee on Negro Troop Policies in 1942, Davis’s recommendations—which included assigning African American officers to command black troops, discontinuing the policy of segregating blood and plasma, gradually removing black soldiers from southern posts, better supervision and racial integration of military police, desegregating base entertainment facilities, and instituting a mandatory course on racial relations and black history—were routinely omitted from final committee reports.

At the end of 1944, in response to a severe shortage of combat soldiers, Davis, then adviser to General Dwight D. Eisenhower, drafted a plan using black soldiers as replacements in all-white units. Although Eisenhower refused Davis’s suggestion of assigning soldiers based on “need not color,” he allowed black soldiers to be grouped into replacement platoons for white companies. Davis’s job included the production of public relations and educational materials related to issues of race, the most significant of which, The Negro Soldier (1944), was produced by the U.S. Army film unit run by Frank Capra. This film, which includes references to the history of African American soldiers and prominent blacks, was shown to all incoming soldiers. Davis was instrumental in arranging for the film to be released to the general public and for the production of a sequel, Teamwork (1946).

The longer he lived abroad, the more vocal became Davis’s opposition to the army’s segregationist policies. In a memo dated 9 November 1943, he lamented the difficulties facing the black soldier “in a community that offers him nothing but humiliation and mistreatment. . . . The Army, by its directives and by actions of commanding officers, has introduced the attitudes of the ‘Governors of the six Southern states’ in many of the 42 states” (Redstone Arsenal Historical Information papers). Davis was clear in his testimony before a 1945 congressional committee: “Segregation fosters intolerance, suspicion, and friction” (Fletcher, 147). Davis’s unprecedented visibility—there was even a story about both Benjamin Sr. and Jr. in True Comics in 1945—drew fire from those who criticized what they considered Davis’s accommodationist approach to combating disrimination within the army.

In 1945 Davis was awarded the Distinguished Service Medal for his work “on matters pertaining to Negro troops.” A year later he was reassigned to the Office of Inspector General and focused on the army’s postwar policy regarding black soldiers. The results of integrating the replacement program were encouraging; of the 250 white soldiers queried, 77 percent answered “Yes, have become more favorable towards colored soldiers since having served in the same unit with them” (U.S. Army report, 3 July 1945).

At a ceremony presided over by President Harry S. Truman in the White House Rose Garden, Davis retired on 14 July 1948 after fifty years of service. Twelve days later, President Truman issued Executive Order 9981, which established “equality of treatment and opportunity for all persons in the armed services without regard to race, color, religion or national origin.” The last racially segregated unit was abolished in 1954. Davis, who died of leukemia, is buried in Arlington National Cemetery. In 1997 a commemorative U.S. postage stamp was issued in his honor.

The papers of Benjamin Oliver Davis Sr. are held by Mrs. James McLendon of Chicago.

Fletcher, Marvin E. America’s First Black General (1989).

—LISA E. RIVO

DAVIS, MILES

DAVIS, MILES(26 May 1926–28 Sept. 1991), trumpeter, band leader, and composer, was born Miles Dewey Davis III in Alton, Illinois, the son of Miles Davis II, a dentist, and Cleota H. Henry, both from Arkansas. When Miles was one year old, his family moved to a multiracial neighborhood in East St. Louis, Illinois, where his father prospered, buying a farm in nearby Millstadt. Young Miles first studied trumpet with Elwood C. Buchanan and Joseph Gustat, the principal trumpeter with the St. Louis Symphony Orchestra, and he soon found work in local dance bands.

Caught up in the new music called bebop, Davis left for New York City after graduation and enrolled in the Juilliard School of Music, where he was exposed to the music of such composers as Hindemith and Stravinsky, and where he studied trumpet with William Vacchiano, principal trumpeter with the New York Philharmonic. Davis’s nights were spent in the clubs on Fifty-second Street, where he first saw his heroes, CHARLIE PARKER, BILLIE HOLIDAY, Eddie Davis, and Coleman Hawkins, and soon began to perform with them. At a time when other trumpet players were emulating DIZZY GILLESPIE’S bravura runs into the upper register and highspeed improvising, Davis cultivated an elegant soft tone and a deliberative approach. His solos were filled with space—pauses and phrasing that let the rhythm section be heard—and he abandoned the fast vibrato that most trumpet players favored. Such a spare approach led some to hear what he was attempting as amateurish, the efforts of a second-rate musician, but many of his contemporaries appreciated his individuality.

In 1945 Irene Cawthorn, Davis’s high school sweetheart, was pregnant with their first child, and she joined him in New York during his second semester at Juilliard. He left school the next fall to join Charlie Parker’s quintet, and played and recorded with them off and on for the next few years. When Parker and Dizzy Gillespie left for the West Coast in 1946, Davis followed them and joined the Benny Carter Orchestra, then went back East with the Billy Eckstine Orchestra, a large bebop band filled with the music’s finest players. It was while in the Eckstine Orchestra that Davis first began to use cocaine and heroin.

Now recognized as an innovator in bebop, Davis began to explore other ways of playing, and he made musical change his defining feature. In 1948, with the help of arranger and composer Gil Evans, he withdrew from the heat of bebop to develop the chamberlike music of a nine-piece group. Later dubbed the “Birth of the Cool” band, the group was, paradoxically, modeled on the somber, understated Claude Thornhill Orchestra, a white dance band. Almost immediately afterward, Davis formed a quintet that abandoned the aesthetics of cool and formulated what some call “hard bop,” a music that intensified elements of bebop. Almost single-handedly, Davis had set into motion two warring styles that have been the subject of critical debate ever since.

After a trip to Paris in 1949, where he met writers and avant-gardists Boris Vian and Jean Paul Sartre, and fell in love with Juliette Greco, doyenne of the French bohemian world, Davis began making a number of important records in the 1950s with younger innovators such as Sonny Rollins and ART BLAKEY. In 1955 Davis put together a quintet with the innovative saxophonist JOHN COLTRANE, drummer Philly Joe Jones, bassist Paul Chambers, and pianist Red Garland. This popular group produced a series of recordings for Prestige Records, including Relaxin’ (1956) and Steamin’ (1956). The quintet’s stylish mix of bebop lines and show tunes came to define jazz in the 1950s and in years to come. In a move that paid off handsomely, Davis recorded with this band for Columbia Records while still on contract at Prestige. Columbia released ’Round About Midnight (1956) as soon as his contract with Prestige had expired.

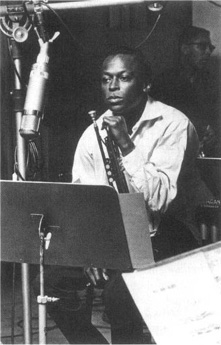

Miles Davis in a pensive moment during a recording session at Fontana Records, c. 1973. © Hulton-Deutsch Collection/CORBIS

Columbia had big plans for Davis and promoted him as both a bebopper who had played with Charlie Parker and as a romantic figure who could play for a larger audience. After a few experimental recordings that blended classical and jazz music, released as The Birth of the Third Stream (1956), Davis followed with a series of albums that caught the public’s fancy. Miles Ahead (1957) paired him again with arranger Gil Evans, and extended the Birth of the Cool idea into a larger instrumental setting. Porgy and Bess (1958) was next, with Evans’s lush settings providing Davis the popular platform he had been seeking. For Sketches of Spain (1959–1960), Evans turned to compositions by Joaquim Rodrigo, Manuel de Falla, and Spanish folk melodies, allowing Davis to display the dramatic elements of his playing, and producing a jazz record that simultaneously gestured towards classical, world, and mood music. When the French film director Louis Malle asked Davis to improvise the score for his film Ascenseur pour l’échafaud in 1957, the results were so successful that Davis undertook additional film music work, scoring music for Siesta (1987), The Hot Spot (1990), and most notably A Tribute to JACK JOHNSON (1970).

Outside these side projects and recordings with large groups, Davis continued to work nightly with his quintet. In 1958 he added alto saxophonist Julian “Cannonball” Adderley and pianist Bill Evans to the group, and in 1959 they recorded Kind of Blue, a largely improvised album of pieces based on modes rather than chord progressions. This turned out to be Davis’s most popular record, and possibly the best-selling jazz record of all time.

Just as Davis had disregarded the conventional wisdom on what jazz should sound like, he also rejected nostalgia, adulation, and the cultivation of fans. Dressed in designer suits, Davis left his Playboy-inspired house on New York’s Upper West Side and drove to gigs in his Ferrari. Once on the bandstand, he refused to announce songs or introduce musicians, ignored applause, and when not playing, either turned away from the audience or left the stage. By refusing even a smile, Davis gained a certain magisterial distance, an air of nobility that reversed a century of performance haunted by the obsequiousness of minstrelsy. He would soon insist that the white female models who routinely adorned jazz album covers in the 1950s be replaced by black models, and more often than not it was his own face staring emotionless into the camera.

All this was part of what drew crowds to Davis’s performances. He gained a sympathetic following among beats and hipsters. His persona and his onstage naturalism made him an exemplar for Method actors like James Dean, Dennis Hopper, and Marlon Brando. The Davis enigma was compounded by his silence about his work, both to the public and to his musicians, whom he seldom rehearsed or instructed about playing. On the rare occasions when Davis did speak, contradictions abounded. He might declare his allegiance to African American culture, and denounce white music, and then hire white musicians or proudly declare that he had learned to phrase on trumpet from listening to Frank Sinatra and Orson Welles. He would praise popular black performers like Sly and the Family Stone and JIMI HENDRIX, but just as quickly announce that he was studying the works of the Polish classical composer Krzysztof Penderecki and planning to record an instrumental version of Puccini’s Tosca. His political views were complex and contradictory. Too much the hipster to espouse causes in depth, Davis nonetheless sometimes played for leftist political rallies, and often spoke forcefully on the subject of white control of the entertainment business.

Davis’s stylish dress and modish lifestyle gave him a visibility that other jazz musicians never achieved, and made him popular in the world of show-business. He traveled widely, made a great deal of money, and married or lived with a number of women, most of whom were in show business, including dancer Frances Taylor and actress Cicely Tyson. In addition to music, Davis had a number of interests that endlessly fascinated his audience. A friend of the welterweight champion Johnny Bratton, Davis trained as a boxer, and he raised horses, which he entered into competitions. He appeared on screen in the television series Miami Vice (1984) and in such films as Dingo (1991), and late in life he took up painting, working collaboratively with another painter, in effect improvising collectively.

There were times when the facts of Davis’s social life threatened to overwhelm his music. Although he overcame heroin, other addictions plagued him for most of his life and contributed to his ongoing illnesses and physical ailments, including recurring nodes on the larynx (that led to his distinctive growl), diabetes, sickle-cell anemia, heart attacks and strokes, a degenerative hip, gallstones and ulcers, and what was rumored to be AIDS. In 1959 Davis’s picture—his head bandaged, blood streaming down his tailored khaki jacket, a policeman leading him by handcuffs—appeared in newspapers. After refusing a policeman’s order to move along from in front of New York City’s Birdland club, Davis had been beaten over the head with a nightstick. Charges against Davis were ultimately dropped, but the message of the event was clear to many—the beatings received by civil rights demonstrators in the deep South were also a danger in the North, even for the most famous of black Americans.

In the 1960s Davis tried various new combinations of musicians, eventually putting together an exceptional quintet composed of Wayne Shorter on saxophone, Herbie Hancock on piano, Ron Carter on bass, and Tony Williams on drums. This group was abstract and earthy, traditional and free at the same time, and intensely rhythmic and full of melodic invention. Records such as E.S.P. (1965), Miles Smiles (1966), and Nefertiti (1967) redefined what jazz was capable of becoming.

Davis had always forced his audience to catch up with him, but now he went even further, adding electric piano and hinting at rock rhythms and tone color on Filles de Kilimanjaro (1968). He followed with In a Silent Way (1969), another shift in thinking. In a Silent Way was a surprisingly long, soft, and dreamlike work, closer to Ravel than to post-bop or rock, a purely textual piece, more sonic than improvisational. Davis now counted on the editing of producer Teo Macero to shape his work, and the two next recorded Bitches Brew (1969–1970), an album whose sound, production methods, cover art, and two-LP length signaled that Miles Davis—and jazz—were in motion again. Most critics and fans heard this music as Davis’s foray into a new hybrid jazz-rock, although he saw it as a new way of thinking about improvisation and the role of the studio. Recordings Davis made in the mid-1970s, including On the Corner (1972) and Dark Magus (1974), were so richly textured with electronics and underpinned by funk rhythms that they became even harder to categorize—Psychedelic jazz? Free rock?

Davis’s illnesses and addictions led to a breakdown in 1975, and he withdrew into the darkness of his house for the next four years. With the help of friends and lovers, he began to recover and play again, and in 1979 he formed a series of rock-inflected groups that made a series of uneven records, such as Star People (1982–1983) and You’re Under Arrest (1984–1985). Breaking with Evans and Macero in 1986, Davis began to record the synthesizer-driven albums, like Tutu (1986–1987) and Amandla (1988–1989), that made him an international superstar. Although these studio recordings show Davis as restrained and often being led through the paces by producers, his live recordings from this period, such as Live Around the World (1988–91), were spirited reinventions. His final recordings, including Miles and Quincy Live at Montreux (1991), which he recorded with QUINCY JONES, were a return to his old style. An effort at hip hop (Doo-Bop) was not completed before his death in Santa Monica, California, in 1991.

Davis, Miles, with Quincy Troupe. Miles: The Autobiography (1989).

Carr, Ian. Miles Davis: The Definitive Biography (1998).

Chambers, Jack. Milestones: The Music and Times of Miles Davis (1998).

Szwed, John. So What: The Life of Miles Davis (2002).

Tingen, Paul. Miles Beyond: The Electric Explorations of Miles Davis, 1967–1991 (2001).

Obituary: New York Times, 6 Oct. 1991.

Discography

Lohmann, Jan. The Sound of Miles Davis: The Discography (1992).

—JOHN SZWED

DAVIS, OSSIE

DAVIS, OSSIE(18 Dec. 1917–), writer, actor, and director, was born in Cogdell, Georgia, the oldest of four children of Kince Charles Davis, an herb doctor and Bible scholar, and Laura Cooper. Ossie’s mother intended to name him “R.C.,” after his paternal grandfather, Raiford Chatman Davis, but when the clerk at Clinch County courthouse thought she said “Ossie,” Laura did not argue with him, because he was white.

Ossie was attacked and humiliated while in high school by two white policemen, who took him to their precinct and doused him with cane syrup. Laughing, they gave the teenager several hunks of peanut brittle and released him. He never reported the incident but its memory contributed to his sensibilities and politics. In 1934 Ossie graduated from Center High School in Waycross, Georgia, and even though he received scholarships to attend Savannah State College and Tuskegee Institute he did not have the minimal financial resources to take advantage of them. Instead, he spent a year clerking at his father’s pharmacy in Valdosta, Georgia, before hitchhiking to Howard University, in Washington, D.C. Ossie spent the next four years at Howard, but he did not receive a degree, as he had taken only the classes that appealed to him. However, at Howard, Ossie met the poet and scholar STERLING BROWN, who introduced him to the work of LANGSTON HUGHES and COUNTÉE CULLEN. Brown, Ossie later wrote, showed him that the “interest of my people was at stake, and I could only be a hero by serving their urgent cause. The Struggle opened a new chapter in my imagination” (Davis and Dee, 74–75). ALAIN LOCKE, his Howard theater teacher, began by introducing him to the world of black drama and ended up, according to Ossie, “giving me my life.”

Another early influence on Ossie was Eldon Stuart Medas, leader of a West Indian student bull-session group at Howard, who showed Ossie how to love English poets and playwrights and how to use them to win political arguments. As Ossie was preparing to leave Howard in 1939, he attended the 16 April concert given by MARIAN ANDERSON on the steps of the Lincoln Memorial. This event, he later reflected, “married in my mind forever the performing arts as a weapon in the struggle for freedom. . . . It reminded me that whatever I said and whatever I did as an artist was an integral part of my people’s struggle to be free” (Davis and Dee, 86–87).

Davis moved to Harlem at the suggestion of Locke, who recommended that the budding playwright apprentice himself to Dick Campbell, founder and artistic director of the ROSE MCCLENDON Players (RMP). At the RMP, Davis learned the fundamentals of acting and stagecraft and appeared in four plays between 1939 and 1941, including BOOKER T. WASHINGTON, a play by William Ashley starring Dooley Wilson. Davis later said of the RMP that “it cultivated and serviced the Harlem Community with high-grade entertainment that gave Negroes a chance to see their own lives. . . [and gave] Negro actors, stage managers, set designers, and assorted technicians, a chance to learn and practice their craft under the best instruction” (Davis, “The Flight from Broadway,” 15).

In 1942 Davis’s career was interrupted when he was drafted during World War II; he served as a medic in Liberia until 1945, after which he returned to New York, where the director Herman Shumlin cast him as the lead in Robert Ardrey’s play Jeb. The drama, the story of a returning African American veteran who faces down the Ku Klux Klan to marry his girlfriend, costarred RUBY DEE. Davis and Dee appeared together again later that year in the national tour of Anna Lucasta and in 1948 at the Lyceum Theater in The Smile of the World. The couple married in 1948 and had three children: Nora, Guy, and Hasna.

Although Davis performed in fifteen plays between 1948 and 1957—including Marc Connelly’s Green Pastures (1951) and Jamaica (1958) opposite LENA HORNE on Broadway, for which he received a Tony Award nomination—he thought of himself principally as a playwright. Since 1939, however, he had been struggling to complete “Leonidas Is Fallen,” the story of a slave hero—modeled after the slave revolt leaders GABRIEL, DENMARK VESEY, and NAT TURNER—who dies fighting for his freedom. Davis hoped to create a “new kind of drama,” different from contemporary black musical comedies and adaptations. During this period, Davis attended meetings of the Young Communist League in Harlem, paying close attention to the political speakers but also to the writers, from whom he hoped to find literary, as well as political, solutions. Davis never became a Communist, but he eventually became a playwright, with help from a playwriting class at Columbia University in 1947.

When Davis replaced SIDNEY POITIER opposite Dee in A Raisin in the Sun, it encouraged him to finish his play, Purlie Victorious (1961), which Davis described as the “adventures of Negro manhood in search of itself in a world for white folks only,” that revealed “a world that emasculated me, as it does all Negro men. . . and taught me to gleefully accept that emasculation as the highest honor America could bestow” (Davis, “Purlie Told Me!” 155–156). In 1963 Davis adapted the play into a film, Gone Are the Days, in which he and Dee starred. In 1970 he retooled the play as a musical for Broadway, Purlie, which was nominated for a Tony Award for Best Musical.

Davis’s film and television work began in 1950 with the film No Way Out, in which he starred with Dee. Over the next fifty years, working with many of America’s best filmmakers and performers, he appeared in more than one hundred film and television projects, including The JOE LOUIS Story (1953); The Cardinal (1963), directed by Otto Preminger; The Hill (1965), directed by Sidney Lumet; A Man Called Adam (1966), featuring SAMMY DAVIS JR., Cicely Tyson, and Louis ARMSTRONG; The Scalphunters (1968), directed by Sidney Pollock; Let’s Do It Again (1975), directed by Sidney Poitier and starring Poitier and BILL COSBY; Harry and Son (1984), directed by Paul Newman; and I’m Not Rappaport (1996), costarring Walter Matthau. Davis has maintained a particularly rich creative relationship with the filmmaker SPIKE LEE, appearing in School Daze (1988), Do the Right Thing (1989), Jungle Fever (1991), Malcolm X (1992), and Get on the Bus (1996).

In addition to his many television guest appearances, Davis has had recurring roles in a number of television series, including the detective drama The Outsider (1967); B. L. Stryker (1989–1990), opposite Burt Reynolds; Evening Shade (1990–1994); and The Promised Land (1996). He has starred in numerous television dramas and miniseries, including many African American-themed works, such as Roots (1979), which also featured Dee; Don’t Look Back: The Story of Leroy “SATCHEL” PAIGE (1981); and King (1978), in which he played Martin Luther King Sr. Davis’s writing credits include For Us the Living: The MEDGAR EVERS Story (1983), which he cowrote with MYRLIE EVERS-WILLIAMS for American Playhouse, and three children’s books: Just like Martin (1992) about MARTIN LUTHUR KING JR.; Escape to Freedom: A Play about Young FREDERICK DOUGLASS (1978), winner of the Jane Addams Children’s Book Award and the American Library Association’s CORETTA SCOTT KING Award; and Langston, a Play (1982).

In 1970 Davis directed his first film, Cotton Comes to Harlem (1970), an adaptation of CHESTER HIMES’S detective novel about an armed robbery at a Back-to-Africa rally in Harlem. The commercial success of Cotton, for which Davis also wrote the screenplay and several songs, paved the way for what became known as the “blaxploitation” films of the 1970s. Although he was wary of many of the blaxploitation films, Davis agreed with the critic Clayton Riley that they constituted “part of a stage of development for a number of people” (Riley, “On the Film Critic,” Black Creation, 1972, 15), and he agreed to direct the film adaptation of J. E. Franklin’s play Black Girl in 1972. Davis chose the project—about a high school dropout who dreams of becoming a ballet dancer but settles for dancing in a bar—in order to demonstrate to Hollywood and to black filmmakers, in particular, that black film could be both entertaining and reflective of the lives of real African Americans. In the early 1970s Davis directed Kongi’s Harvest (1971), Gordon’s War (1973), and Countdown at Kusini (1976), which he also wrote, and he established the Third World Cinema Corporation, a New York-based production company that trained African Americans and Latinos for film and television production jobs.

In 1980 Davis and Dee founded their own production company, Emmalyn II Productions Company. Together they produced and hosted three seasons of the critically acclaimed PBS television series With Ossie and Ruby and three years of the Ossie Davis and Ruby Dee Story Hour, a radio broadcast for the National Black Network. The couple has participated, separately and together, in the creation of numerous documentary and nonfiction projects, including Martin Luther King: The Dream and the Drum; Mississippi, America; and A Walk through the 20th Century with Bill Moyers for PBS. In 1998 they cowrote an autobiography, With Ossie and Ruby: In This Life Together. In 2002 Davis completed a new play, A Last Dance for Sybil, which ran in New York starring Dee.

Davis and Dee’s commitment to civil rights and humanitarian causes has been central to their life and work. They have labored to introduce staged productions and readings into schools, unions, community centers, and, especially, black churches, because they were repositories “of all we thought precious and worthy to be passed on to our children” (Davis and Dee, 253). In the 1950s they risked their careers by stridently resisting Senator Joseph McCarthy’s blacklisting activities. Highly active and visible during the civil rights movement, they served as masters of ceremonies for the 1963 March on Washington, and in 1964 they helped establish Artists for Freedom, which donated money to civil rights organizations in the name of the four little girls killed in Birmingham, Alabama. Davis’s stirring eulogy at the 1965 funeral of MALCOLM X flawlessly articulated black America’s loss: “Malcolm had stopped being a ‘Negro’ years ago. It had become too small, too puny, too weak a word for him. Malcolm was bigger than that. Malcolm had become an Afro-American and he wanted—so desperately—that we, that all his people, would become Afro-Americans too. . . . Malcolm was our manhood, our living, black manhood! This was his meaning to his people. And, in honoring him, we honor the best in ourselves.” Davis and Dee’s political work continued unabated over the next decades.

In addition to their many individual honors, Davis and Dee have jointly received the Actors’ Equity Association PAUL ROBESON Award (1975), the Academy of Television Arts and Sciences Silver Circle Award (1994), and induction into the NAACP Image Awards Hall of Fame (1989). In 1995 they were awarded the National Medal of Arts by President Bill Clinton, and in 2000 they received the Screen Actors Guild’s highest honor, the Life Achievement Award.

Davis, Ossie. “Purlie Told Me!,” Freedomways (Spring 1962).

_______. “The Flight from Broadway,” Negro Digest (April 1966).

Davis, Ossie, and Ruby Dee. With Ossie and Ruby: In This Life Together (1998).

—SAMUEL A. HAY

DAVIS, SAMMY, JR.

DAVIS, SAMMY, JR.(8 Dec. 1925–16 May 1990), singer, dancer, and actor, was born in Harlem, New York, the first of two children of Sammy Davis Sr., an African American vaudeville entertainer, and Elvera Sanchez, a Puerto Rican chorus dancer. Sammy’s paternal grandmother, “Mama Rosa,” raised him until he was three years old, when his father, who had separated from Elvera, took his son with him on the road. Within a few years, the child’s role grew from that of a silent prop to that of a show-stealing singer and dancer, the youngest member of the Will Mastin Trio, featuring Sammy Davis Jr.

Fellow performers were the only family Sammy knew, and the world of the theater was the only school he ever attended. He was billed as “Silent Sam, the Dancing Midget” to hide him from truant officers and child labor investigators. After a period during which the group could not find work or shelter, Davis’s father thought about returning the boy to his grandmother, only to discover that the young ham had already become addicted to the stage, the spotlight, and the adulation of approving audiences. In retrospect, Davis said he had “no chance to be bricklayer or dentist, dockworker or preacher” (Early, 4). By age seven he had made his film debut in the comedy Rufus Jones for President (1933), in which he played the title role of a little boy who falls asleep in the lap of his mother, played by ETHEL WATERS, and dreams that he is elected president of the United States.

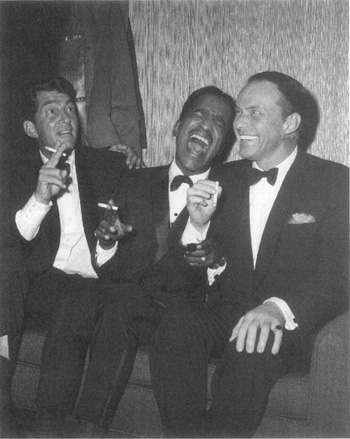

Sammy Davis Jr. with fellow “Rat Pack” members Dean Martin and Frank Sinatra following a Carnegie Hall benefit for MARTIN LUTHER KING JR. in 1961. © Bettmann/CORBIS

During the Depression, Davis traveled on the “Chitlin’ Circuit,” a network of clubs that hired black acts to fill the time between performances by white headliners. Black entertainers had only a few minutes on stage and were prohibited from speaking directly to the audience; therefore, they often used a rapid variety of singing, dancing, and joking to hold the audience’s attention. This eclectic quality came to define Davis’s career. He believed it made him a superior entertainer; some critics believe he might have done better to focus on singing or dancing. Thus while Davis mastered several vocal and dance styles, nailed a number of impersonations, and played the drums, trumpet, vibes, and other instruments, he never developed his own style. BILL “BOJANGLES” ROBINSON, STEPIN FETCHIT, MOMS MABLEY, and REDD FOXX were among Davis’s early influences, but he made the transition from vaudeville to Vegas, from burlesque to Broadway more easily than any of his predecessors and became one of the first “crossover” African American celebrities in the United States.

Groucho Marx saw Davis perform at the Hillcrest Country Club and said, “This kid’s the greatest entertainer,” and then turned to Al Jolson, who was seated at his table, and remarked “and this goes for you, too” (Levy, 49). Davis’s big break, however, occurred in 1941, when the Will Mastín Trio was performing in Detroit as an opening act for Frank Sinatra. Sinatra was so impressed by the fifteen-year-old entertainer that he used his growing fame to help Davis get some of the recognition and respect he deserved. Later Sinatra, too, would say that Davis was the greatest performer he had ever seen, because he could “do anything except cook spaghetti” (Boston Globe, 17 May 1990).

Davis’s promising career was briefly interrupted when he was drafted into the U.S. Army, serving from 1943 to 1945. Although his unit at Fort Warren, Wyoming, was integrated, Davis suffered racial discrimination and beatings. After basic training, Davis was placed in Special Services, where he entertained enlisted men along with George M. Cohan. Throughout his life, Davis was determined to use his talent to make audiences love him even if they hated him. For him, performance was not only a way of transcending racial barriers, it was a means of gaining acceptance and distinguishing himself. As he wrote, “If God ever took away my talent I would be a nigger again” (Early, 20–21). Yet he realized that his success was Pyrrhic, that “being a star has made it possible for me to get insulted in places where the average Negro could never hope to go and get insulted” (Curt Schleir, “The Public Acclaim and Private Pain of Sammy Davis Jr.,” Biography, 4.2 [Feb. 2000], 88).

After leaving the army, Davis made his first recording with Capitol Records and was named Most Outstanding New Personality of 1946 by Metronome magazine. The Will Mastin Trio regrouped and began opening for Mickey Rooney in Las Vegas in 1947 and the following year for Frank Sinatra in New York. These engagements led to television appearances on Eddie Cantor’s Colgate Comedy Hour and the Ed Sullivan Show. By the early 1950s Davis had enough clout to force the integration of many of the hotels at which he performed. In 1954 his career could have ended when his car smashed into another vehicle while driving from Las Vegas to California. Davis lost his left eye in the accident, but within ten months he was back on stage performing with an eye patch—and, because of the publicity, he was bigger than ever.

In 1956 Davis played the lead in the Broadway musical Mr. Wonderful, in 1958 he appeared opposite EARTHA KITT in the film Anna Lucasta, and in 1959 he played Sporting Life in the film version of George Gershwin’s Porgy and Bess. Beginning with Ocean’s Eleven (1960), Davis made six films as part of a group of jet-setting actors dubbed the “Rat Pack,” including Frank Sinatra, Tony Curtis, Dean Martin, Peter Lawford, and Joey Bishop. During this period, Davis’s flashy jewelry, ostentatious dress, and characteristic jive talk made him the epitome of “hip” and, along with MILES DAVIS, the king of the “Cool Cats.”

Controversy was an inseparable part of Davis’s popularity. In an effort to quell rumors about his relationships with white women, Davis rushed into a marriage with Loray White, an African American dancer, in 1958. The marriage lasted only a few months. His highly publicized conversion to Judaism, which began sincerely with Rabbi Max Nussbaum after his accident and was based on an affinity he felt with the Jewish people, was suspected by some of being an indication of his desire to escape his blackness by assimilating into another culture. His relationship with the black community became more problematic after his 1960 marriage to the Swedish actress May Britt, with whom he had one child, Tracey, and adopted two, Mark and Jeff. Despite the fact that Davis was a strong supporter of the civil rights movement and a generous contributor to black charities—qualities that helped him earn the NAACP’s Spingarn Award in 1969—his lifestyle was an easy target for the militants of the 1960s, and his embrace of Republican President Richard M. Nixon in 1972 brought his loyalties into question. Drinking, drug use, and his associations with people in the adult film industry and in satanic cults gave Davis a reputation that he both flaunted and regretted.

Davis was a top draw as a nightclub performer, earning fifteen thousand dollars for a single performance and as much as three million dollars a year, yet he always spent more than he earned. When his accountant expressed concern about his profligate spending, Davis bought him a gold watch with the inscription, “Thanks for the advice.” Although he had become a solo act by the 1960s, he continued to share his salary with his father and Will Mastin for many years thereafter. In 1965 he was nominated for a Tony Award for his performance in Golden Boy, and in 1966 he briefly hosted his own television program, the Sammy Davis Jr. Show. He also appeared as a guest star on such popular shows as Lawman (1961), Batman (1966), I Dream of Jeannie (1967), and The Mod Squad (1969–1970). His appearance on All in the Family (1972) set a Nielsen ratings record, and on several occasions he was a substitute host on The Tonight Show.

In 1970, two years after his divorce from May Britt, Davis married the African American dancer Altovise Gore and adopted another son, Manny. His recording “Candyman” hit the top of the chart in 1972, and other hits, such as “Mr. Bojangles,” “That Old Black Magic,” and “Birth of the Blues,” kept him in constant demand. His activities slowed during the 1980s as Davis struggled with various kidney and liver ailments and a hip replacement. President Ronald Reagan presented him the Gold Medal for Lifetime Achievement from the Kennedy Center for the Performing Arts in 1987.

Davis played his final role, as an aging dancer, in the movie Tap (1989), with his protégé Gregory Hines. He died the following year of throat cancer. He left three autobiographies, twenty-three films, and two dozen recordings to entertain future generations.

Davis, Sammy, Jr. Hollywood in a Suitcase (1980).

_______. Why Me? (1989).

_______. Yes I Can (1965).

Early, Gerald. The Sammy Davis, Jr., Reader (2001).

Haygood, Wil. In Black and White: The Life of Sammy Davis, Jr. (2003).

Levy, Shawn. Rat Pack Confidential (1998).

Obituaries: New York Times, 17 May 1990; Rolling Stone, 28 June 1990; Ebony, July 1990.

—SHOLOMO B. LEVY

DAY, WILLIAM HOWARD