DOUGLASS, SARAH MAPPS

DOUGLASS, SARAH MAPPSMartin, Waldo E., Jr. The Mind of Frederick Douglass (1984).

McFeely, William S. Frederick Douglass (1991).

Preston, Dickson J. Young Frederick Douglass: The Maryland Years (1980).

QUARLES, BENJAMIN. Frederick Douglass (1948).

Voss, Frederick S. Majestic in His Wrath: A Pictorial Life of Frederick Douglass (1995).

Walker, Peter F. Moral Choices: Memory, Desire, and Imagination in Nineteenth-century American Abolition (1978).

—ROY E. FINKENBINE

DOUGLASS, SARAH MAPPS

DOUGLASS, SARAH MAPPS(9 Sept. 1806–8 Sept. 1882), abolitionist and educator, was born in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, the daughter of Robert Douglass Sr., a prosperous hairdresser from the island of St. Kitts, and Grace Bustill, a milliner. Her mother was the daughter of Cyrus Bustill, a prominent member of Philadelphia’s African American community. Raised as a Quaker by her mother, Douglass was alienated by the blatant racial prejudice of many white Quakers. Although she adopted Quaker dress and enjoyed the friendship of Quaker antislavery advocates like Lucretia Mott, she was highly critical of the sect.

In 1819 Grace Douglass and philanthropist JAMES FORTEN SR. established a school for black children, where “their children might be better taught than . . . in any of the schools . . . open to [their] people.” Sarah Douglass was educated there, taught for a while in New York City, and then returned to take over the school.

In 1833 Douglass joined an interracial group of female abolitionists in establishing the Philadelphia Female Anti-Slavery Society. For almost four decades, she served the organization in many capacities. Also active in the antislavery movement at the national level, she attended the 1837 Anti-Slavery Convention of American Women in New York City. The following year, when the convention met at Philadelphia’s ill-fated Pennsylvania Hall, which in 1838 was burned by an anti-abolitionist mob, she was elected treasurer. She was also a delegate at the third and final women’s antislavery convention in 1839.

Douglass repeatedly stressed the need for African American women to educate themselves. In 1831 she helped organize the Female Literary Association of Philadelphia, a society whose members met regularly for “mental feasts,” and on the eve of the Civil War she founded the Sarah M. Douglass Literary Circle.

Throughout the 1830s Douglass wrote poetry and prose under the pseudonyms “Sophanisba” and “Ella.” Her writings—on the blessings of religion, the prospect of divine retribution for the sin of slavery, the evils of prejudice, and the plight of the slave—were published in various antislavery journals, including the Liberator, the Colored American, the Genius of Universal Emancipation, and the National Enquirer and Constitutional Advocate of Universal Liberty.

During the 1830s and 1840s Douglass was beset by financial problems. Her school never operated at a profit, and in 1838, deciding she could no longer accept the financial backing of her parents, she asked the Female Anti-Slavery Society to take over the school. The experiment proved unsatisfactory, however, and in 1840 she resumed direct control of the school, giving up a guaranteed salary for assistance in paying the rent. In 1852, now reconciled with the Quakers, she closed her school and accepted an appointment to supervise the Girls’ Preparatory Department of the Quaker-sponsored Institute for Colored Youth. From 1853 to 1877 she served as principal of the department.

For more than forty years Douglass enjoyed a close friendship with abolitionists Sarah Grimké and ANGELINA WELD GRIMKÉ. After an uneasy start, the relationship between the daughters of a slaveholding family and the African American teacher deepened into one of great mutual respect. Sarah Grimké, fourteen years Douglass’s senior, eventually became her confidante. After her mother’s death in 1842 left Douglass as unpaid housekeeper to her father and brothers, Grimké sympathized with her: “Worn in body & spirit with the duties of thy school, labor awaits thee at home & when it is done there is none to throw around thee the arms of love.”

In 1854 Douglass received an offer of marriage from the Reverend William Douglass, a widower with nine children and the minister of Philadelphia’s prestigious St. Thomas’s African Episcopal Church. Grimké considered him eminently worthy of her friend. He was a man of education, and his remarks about her age and spinster status were only proof of his lively sense of humor. As for Douglass’s apprehensions about the physical aspects of married life, the unmarried Grimké assured her, “Time will familiarize you with the idea.” The couple was married in 1855. The marriage proved an unhappy one. On her husband’s death in 1861, Douglass wrote of her years “in that School of bitter discipline, the old Parsonage of St. Thomas,” but she acknowledged that William Douglass had not been without his merits.

In one respect, marriage gave Douglass a new freedom. A cause she had long championed was the education of women on health issues. Before her marriage, she had taken courses at the Female Medical College of Pennsylvania. In 1855 she enrolled in the Pennsylvania Medical University and in 1858 embarked on a career as a lecturer, confronting topics that would have been considered unseemly for an unmarried woman to address. Her illustrated lectures to female audiences in New York City and Philadelphia drew praise for being both informative and “chaste.”

Through the 1860s and 1870s Douglass continued her work of reform, lecturing, raising money for the southern freedmen and -women, helping to establish a home for elderly and indigent black Philadelphians, and teaching at the Institute for Colored Youth. She died in Philadelphia.

As a teacher, a lecturer, an abolitionist, a reformer, and a tireless advocate of women’s education, Sarah Mapps Douglass made her influence felt in many ways. Her emphasis on education and self-improvement helped shape the lives of the many hundreds of black children she taught in a career in the classroom that lasted more than a half-century, while her pointed and persistent criticism of northern racism reminded her white colleagues in the abolitionist movement that their agenda must include more than the emancipation of the slaves.

A number of letters to and from Douglass are in the Weld-Grimké Papers at the University of Michigan and the Antislavery Manuscripts at the Boston Public Library. Douglass’s role in the antislavery movement is documented in the records of the Philadelphia Female Anti-Slavery Society at the Historical Society of Pennsylvania and in the published proceedings of the three national women’s antislavery conventions held between 1837 and 1839.

Barnes, Gilbert H., and Dwight L. Dumond, eds. Letters of Theodore Dwight Weld, Angelina Grimké, and Sarah Grimké, 1822–1844 (2 vols., 1934).

Sterling, Dorothy, ed. We Are Your Sisters: Black Women in the Nineteenth Century (1984).

Winch, Julie. Philadelphia’s Black Elite: Activism, Accommodation, and the Struggle for Autonomy, 1787–1848 (1988).

—JULIE WINCH

DOVE, RITA FRANCES

DOVE, RITA FRANCES(28 Aug. 1952–), writer, was born in Akron, Ohio, the second of four children of Ray A. Dove, the first black scientist in the tire industry, and Elvira Elizabeth Hord. Rita, who attended public school, read voraciously and began writing plays and stories while in elementary school. Selected as one of the most outstanding high school graduates in the nation, she visited the White House as a Presidential Scholar in 1970, after which she enrolled at Miami University in Oxford, Ohio, graduating summa cum laude with a BA in English in 1973.

She spent the next year as a Fulbright Scholar at the University of Tübingen in West Germany. Although Dove’s presence drew attention from the locals—“Most Germans don’t consider it impolite to stare, so they simply gawked at me or even pointed” (Taleb-Khyar, 350)—the German language had a lasting impact on her work. “German,” Dove explained, “has influenced the way I write: I have tried to re-create in poems the feeling I had when I first began to speak the language—that wonderful sensation of being held hostage by a sentence until the verb comes along at the end” (Steffen, 168).

Upon her return to the United States, Dove began graduate study at the prestigious Writers’ Workshop at the University of Iowa, earning an MFA in 1977. While in Iowa, Rita met the German writer Fred Viebahn. The couple married in 1979 and have one daughter. In 1981 Dove began teaching creative writing at Arizona State University in Tempe, where she remained until 1989, when she became Professor of English at the University of Virginia in Charlottesville. Almost immediately, Dove began to win grants and fellowships, including a National Endowment for the Humanities (NEH) award that allowed her to serve as a writer in residence at the Tuskegee Institute in 1982.

In the late 1970s Dove’s poems appeared in a number of magazines and anthologies, and she published several chapbooks, including Ten Poems (1977) and The Only Dark Spot in the Sky (1980). Dove’s first book of poetry, Yellow House on the Corner (1980), treats both private, everyday events—a first kiss, family dinners—and the historical events of slavery. Referring to her second collection of poems, Museum (1983), Dove revealed, “One of my goals with that book was to reveal the underside of history, and to represent this underside in discrete moments” (Taleb-Khyar, 356).

Dove explored these themes further in her next poetry collection, Thomas and Beulah (1986), based on the lives of her maternal grandparents. Consisting of two parts—the first written from Thomas’s point of view, the second from Beulah’s—the poems cleverly undercut the idea of a single historical narrative by offering alternative versions of the same events. In preparing the book, Dove interviewed her mother, read transcripts of Works Progress Administration interviews, studied the history of black migration, and listened to blues recordings. “What fascinates me,” Dove explained, “is the individual caught in the web of history” (Taleb-Khyar, 356). Critics agreed, and Thomas and Beulah earned a Pulitzer Prize in 1987.

Rita Dove, who served as the U.S. Poet Laureate from 1993 to 1995. © Christopher Felver/CORBIS

Dove’s other publications include the poetry collections Grace Notes (1989), Selected Poems (1993), Mother Love (1995), Evening Primrose (1998), and On the Bus with Rosa Parks (1999); a collection of short stories, Fifth Sunday (1985); a novel, Through the Ivory Gate (1992); and a play, The Darker Face of the Earth (1994), which employs elements of Greek tragedy in a story set on an antebellum slave plantation in South Carolina.

In 1993 Dove became the youngest person and the third African American appointed Poet Laureate Consultant in Poetry at the Library of Congress, a position she held through 1995. As Poet Laureate, Dove organized lectures and conferences, poetry and jazz evenings, and brought local Washington, D.C., students and Crow Indian children to the Library of Congress to read their poetry and be recorded for the National Archives. She presided over high-profile cultural events, including the 1994 commemoration of the two-hundredth anniversary of the U.S. Capitol, and the unprecedented gathering of Nobel laureates for the Cultural Olympiad in Atlanta, Georgia, in 1995. “I’m hoping that by the end,” Dove told reporters, “people will think of a poet laureate as someone who’s out there with her sleeves rolled up, not sitting in an ivory tower.”

Ever since Dove began singing and playing cello in elementary school, music has been the companion of and inspiration for her poetry. As she explained,

My youth was filled with musical language: the acid drawl of an uncle spinning out a joke; the call-and-response of the AME church; jump rope ditties and BESSIE SMITH on the phonograph; the clear ecstasy of Bach and the sweet sadness of BILLIE HOLIDAY. Buoyed by this living cushion of sound, I began to write.

(Essence, 1995)

In the 1990s Dove produced several major musical collaborations, beginning with Umoja—Each One of Us Counts, commissioned by the 1996 Atlanta Olympic Summer Games. Her other large-scale productions include Singin’ Sepia (1996), Grace Notes (1997), and The Pleasure’s in Walking Through (1998), a collaboration with John Williams.

Writers, like musicians, Dove reminds her students, must study and practice. Dove revises incessantly, putting her poems through as a many as fifty or sixty drafts. In the years before she had family and public obligations, she wrote for up to eight hours each day. For Dove, writing is a combination of serendipity and puzzle solving, and her working methods encourage detours and tangents. “When I’m working on poems, I’m reading all the time,” she revealed, “I just go to the bookshelf almost like a sleepwalker” (Taleb-Khyar, 363). She also relies on notebooks she has filled over the years with fragments of language: snippets of conversations, words, ideas, images, even grocery and “to do” lists.

While she is interested in character and plot, Dove is generally more interested in the way stories are told than in the stories themselves. As a child, Dove challenged herself to write novels composed of words from school spelling lists; later, she found the same thrill in crossword puzzles. “I think my puzzle fetish has something to do with the way poems are constructed. Words start to reverberate by virtue of their proximity to one another. That’s a spatial thing as well as a temporal one” (Steffen, 169). When it comes time to put a draft away, Dove uses an intuitive filing system that eschews organization by subject, date, or title. Instead, she files by color, by how a poem “feels” to her.

Coming of age after the peak of the Black Arts Movement, Dove subscribes to a less polarized, more inclusive, approach to writing and to race than poets one or two decades her senior, such as AMIRI BARAKA, JUNE JORDAN, AUDRE LORDE, and NIKKI GIOVANNI.

When I was growing up, I did not think in terms of black art or white art or any kind of art; I just wanted to be a writer. On the other hand, when I became culturally aware . . . it was exciting to recognize heretofore secret aspects of my experience—the syncopation of jazz, the verbal one-upsmanship of signifying or the dozens—not only to acknowledge their legitimacy, but to see them transformed into art.

(Steffen, 169)

Dove found herself less beholden to the collective, and more interested in the individual, her intimate relationships, and daily life. “I could do nothing else but describe the world I knew—a world where there was both jazz and opera; gray suits and blue jeans, iambic pentameter and the dozens, Shakespeare and [JAMES] BALDWIN” (Essence, 1995).

In addition to more than a dozen honorary doctorates, Dove has been honored with many awards, including the Duke Ellington Lifetime Achievement Award, the Charles Frankel Prize awarded by the NEH, the Heinz Award in the Arts, the Academy of American Poets’ Lavan Younger Poet Award, and fellowships from the Mellon and Rockefeller Foundations. She has served on the advisory or editorial boards of the Associated Writing Programs, the MacDowell Colony, the Thomas Jefferson Center for Freedom of Expression, Callaloo, and Ploughshares, and her media appearances include interviews on all major television networks, collaborations with public television, and a visit to Sesame Street. She is also a sought-after speaker and panel member and has served on juries for the Walt Whitman Award of the Academy of American Poets, the National Book Award, the Ruth Lilly Prize, and the Pulitzer Prize.

The power of language to transform and alter perception is at the heart of Dove’s literary enterprise. “Poetry at its best . . .” she holds, “nudges the body awake. Poetry resonates and transforms by injecting us with the palpable pleasure of language: Words impress their contours on the tongue, and we breathe with the heartbeat and silences of the line tugging against the sentence as it wraps its sense around the instinctual axis” (Ploughshares, Spring 1990).

Harrington, Walt. “A Narrow World Made Wide,” Washington Post Magazine (7 May 1995).

Rubin, Stan Sanvel, and Earl G. Ingersoll. “A Conversation with Rita Dove,” Black American Literature Forum (Autumn 1986).

Steffen, Therese. Crossing Color: Transcultural Space and Place in Rita Dove’s Poetry, Fiction, and Drama (2001).

Taleb-Khyar, Mohamed B. “An Interview with Maryse Conde and Rita Dove,” Callaloo (Spring 1991).

—LISA E. RIVO

DRAKE, ST. CLAIR, JR.

DRAKE, ST. CLAIR, JR.(2 Jan. 1911–15 June 1990), anthropologist, was born John Gibbs St. Clair Drake Jr. in Suffolk, Virginia, the son of John Gibbs St. Clair Drake Sr., a Baptist pastor, and Bessie Lee Bowles. By the time Drake was four years old his father had moved the family twice, once to Harrisonburg, Virginia, and then to Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania.

The family lived in a racially mixed neighborhood in Pittsburgh, where Drake grew to feel at ease with whites. His strict Baptist upbringing gave him a deep understanding of religious organizations. His father also taught him to work with tools and to become an expert in woodworking, a skill Drake later employed in his field research.

A trip to the West Indies in 1922 with his father led to major changes in Drake’s life. Rev. Drake had tried to instill in his son a deep respect for the British Empire, but the sight of the poverty in the Caribbean led the reverend to abandon his support of racial integration and convert to MARCUS GARVEY’s ideas in favor of racial separation and a return to an African homeland for the black diaspora. He quit his pastorship and went to work as an itinerant organizer for Garvey. The young Drake was to trace his interest in anthropology to this trip with his father.

While his father worked for Garvey as an organizer and was constantly away from home on trips, Drake and his mother moved to Staunton, Virginia. In contrast to his Pittsburgh experiences, Drake encountered the caste system in full force in Virginia. These experiences led him to an appreciation of the radical African American poets of his day, particularly LANGSTON HUGHES, COUNTÉE CULLEN, and CLAUDE MCKAY. They also led him to combine action with study.

After graduating with honors from Hampton Institute in Hampton, Virginia, in 1931, Drake worked with the Society of Friends on their “Peace Caravans.” These caravans worked for racial harmony and civil rights. Once again Drake met with whites in a common cause as an equal. He continued to work with the Quakers while teaching at one of their boarding schools. For a time he considered becoming a member of the Society of Friends; however, the realization that there was still prejudice in such a liberal group kept him from converting to the religion.

Drake decided to study anthropology in an effort to better understand the roots of human behavior. After teaching high school at the Christianburg Institute in Cambria, Virginia, from 1932 to 1935, he became a research assistant at Dillard University in New Orleans. There he combined his field research with action, joining the Tenant Farmers Union and the Farmers Union in Adams County, Mississippi. By his own accounts in “Reflections on Anthropology and the Black Experience,” these periodic forays into activism nearly cost him his life. On one occassion, he and follow workers barely escaped a lynch mob. Drake recounts another incident where he was badly beaten and left unconscious.

After a year at Columbia University in 1936, Drake entered the University of Chicago in 1937 on a Rosenwald Fellowship. There he met the sociologist Horace Clayton and joined his research under the auspices of the Public Works Progress Administration (WPA), specializing in the African American church and the urban black population. This work became the basis for his contributions to Black Metropolis (1946), which he jointly authored with Horace B. Cayton. Drake married sociologist Elizabeth Dewy Johns in 1942; they had two children.

During World War II, Drake became actively involved in the struggle of African Americans for equality. He concentrated his efforts on the conflict in northern war industries and housing. He worked with various African American organizations for which he gathered hard data, joined in work actions, and served on various war boards concerned with presenting African American grievances to the federal government. While gathering data for Black Metropolis, Drake worked in a war plant and experienced inequality firsthand. Drake grew bitter at his fellow citizens who so enthusiastically fought fascism abroad but were unwilling to combat it in the United States. In response to these experiences Drake joined the merchant marine, in which he believed he would not encounter the same prejudice and segregation that he might have in the U.S. armed forces.

Following his discharge from the service, Drake completed his PhD in Anthropology at the University of Chicago in 1946 and accepted a position teaching at Roosevelt College that same year. Drake worked extensively in Africa, teaching in both Liberia and Ghana. In 1961 he developed a training program for Peace Corps volunteers in Africa. Over the years he was a personal adviser to many African leaders, including Kwame Nkrumah in Ghana and various high officials in Nigeria. However, as military rule steadily replaced civilian rule in the 1960s, Drake left Africa, refusing to work with dictators.

A prolific scholar, Drake focused his writing on racial concerns such as the problem of inequality, the plight of the urban poor, religion, race relations, and the relationship of African Americans to Africa. His major works include Race Relations in a Time of Rapid Social Change (1966), Our Urban Poor: Promises to Keep and Miles to Go (1967), and The Redemption of Africa and Black Religion (1970). He edited numerous journals and books and brought intellectuals together to discuss the issues of the day and propose actions to meet these problems.

In 1969 Drake moved to Stanford University, where he established the Center for Afro-American Studies, an Afro-American studies department that became a model for other universities. Drake refused to bow to the demand of radicals who wanted the department to be a center exclusively for black students, where others interested in African and Afro-American history would not be welcome. He refused to teach Afrocentric notions that saw Africans as the center of all civilizations and the inventors of all wisdom. He resisted the efforts of black militants outside and inside academia—STOKELY CARMICHAEL, James Turner at Cornell, Felix Okoye, and others—who believed that a person’s skin color accredited or discredited him or her as an expert in African and Afro-American studies. Drake insisted on establishing his center on solid academic grounds.

Throughout his life, Drake showed personal integrity in working to achieve his goals of equality and respect for African Americans and their accomplishments. He founded the American Society for African Culture and the American Negro Leadership Conference on Africa in the early 1960s. He was never afraid to risk his life in pursuit of his goals. Drake died at his home in Palo Alto, California.

Some of Drake’s manuscripts are in the collection of the Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture of the New York Public Library.

Romero, Patrick W. In Black America, 1968: The Year of Awakening (1969).

Uya, Okon Edet. Black Brotherhood: Afro-Americans and Africa (1971).

Washington, Joseph R., Jr. Jews in Black Perspective (1984).

Obituary: New York Times, 21 June 1990.

—FRANK A. SALAMONE

DREW, CHARLES RICHARD

DREW, CHARLES RICHARD(3 June 1904–1 Apr. 1950), blood plasma scientist, surgeon, and teacher, was born in Washington, D.C., the son of Richard Thomas Drew, a carpet-layer, and Nora Rosella Burrell. Drew adored his hard-working parents and was determined from an early age to emulate them. Drew’s parents surrounded their children with the many opportunities available in Washington’s growing middle-class black community: excellent segregated schools, solid church and social affiliations, and their own strong example. Drew’s father was the sole black member of his union and served as its financial secretary.

Drew graduated from Paul Laurence Dunbar High School in 1922 and received a medal for best all-around athletic performance; he also won a scholarship to Amherst College. At Amherst he was a star in football and track, earning honorable mention as an All-American halfback in the eastern division, receiving the Howard Hill Mossman Trophy for bringing the greatest athletic honor to Amherst during his four years there, and taking a national high hurdles championship. A painful brush with discrimination displayed Drew’s lifelong response to it: after Drew was denied the captaincy of the football team because he was black, he ended the controversy by quietly refusing to dispute the choice of a white player. His approach to racial prejudice, as he explained in a letter years later, was to knock down “at least one or two bricks” of the “rather high-walled prison of the ‘Negro problem’ by virtue of some worthwhile contribution” (Love, 175). Throughout his life Drew, whether as a pioneer or as a team leader, helped others scale hurdles so they too could serve society.

Dr. Charles Drew teaching at Freedmen’s (now Howard) University Hospital. Moorland-Spingarn Research Center

While recuperating from a leg injury, Drew decided to pursue a career in medicine. He worked for two years as an athletic director and biology and chemistry instructor at Morgan College (now Morgan State University), a black college in Baltimore, Maryland, to earn money for medical school. There were few openings for black medical students at this time, but Drew was finally admitted to McGill University Medical School in Montreal, Canada. Despite severe financial constraints, he graduated in 1933 with an MDCM (doctor of medicine and master of surgery) degree, second in his class of 137. He was vice president of Alpha Omega Alpha, the medical honor society, and won both the annual prize in neuroanatomy and the J. Francis Williams Prize in Medicine on the basis of a competitive examination. Drew completed a year of internship and a year of residency in internal medicine at Montreal General Hospital. He hoped to pursue training as a surgery resident at a prestigious U.S. medical institution, but almost no clinical opportunities were available to African American doctors at this time. Drew decided to return to Washington, taking a job as an instructor in pathology at Howard University Medical School during 1935–1936.

Howard’s medical school was then being transformed from a mostly white-run institution to a black-led one, through the efforts of Numa P. G. Adams, dean of the medical school, and the charismatic MORDECAI JOHNSON, Howard’s first black president. Adams nominated Drew to receive a two-year fellowship at Columbia University’s medical school.

No black resident had ever been trained at Presbyterian Hospital when Drew arrived at Columbia in the fall of 1938, but Drew so impressed Allen O. Whipple, director of the surgical residency program, that he received this training unofficially, regularly making rounds with Whipple. In the meantime, Drew pursued a doctor of science degree in medicine, doing extensive research on blood-banking, a field still in its infancy, under the guidance of John Scudder, who was engaged in studies relating to fluid balance, blood chemistry, and blood transfusion. With Scudder, Drew set up Presbyterian Hospital’s first blood bank. After two years he produced his doctoral thesis, “Banked Blood: A Study in Blood Preservation” (1940), which pulled together existing scientific research on the subject. He became the first African American to receive the doctor of science degree, in 1940. In 1939 Drew had married Minnie Lenore Robbins, a home economics professor at Spelman College. They had four children.

Drew returned to Howard in 1940 as an assistant professor in surgery. In September of that year, however, he was called back to New York City to serve as medical director of the Blood for Britain Project, a hastily organized operation to prepare and ship liquid plasma to wounded British soldiers. He confronted the challenge of separating liquid plasma from whole blood on a much larger scale than it had ever been done before and shipping it overseas in a way that would ensure its stability and sterility. His success in this led to his being chosen in early 1941 to serve as medical director of a three-month American Red Cross pilot project involving the mass production of dried plasma. Once again Drew acted swiftly and effectively, aware that the model he was helping to create would be critical to a successful national blood collection program. Red Cross historians agree that Drew’s work in this pilot program and the technical expertise he amassed were pivotal to the national blood collection program, a major life-saving factor during the war.

Soon after being certified as a diplomate of the American Board of Surgery, Drew returned to Howard in April 1941. In October he took over as chairman of Howard’s Department of Surgery and became chief surgeon at Freedmen’s Hospital, commencing what he viewed as his real life’s work, the building of Howard’s surgical residency program and the training of a team of top-notch black surgeons.

In December 1941 the United States entered the war, and the American Red Cross expanded its national blood collection program. It announced that it would exclude black donors, and then, in response to widespread protest, it adopted a policy of segregating the blood of black donors. Drew spoke out against this policy, pointing out that there was no medical or scientific reason to segregate blood supplies by race. (The Red Cross officially ended its segregation of blood in 1950.) His stance catapulted him into the national limelight: the irony of his being a blood expert and potentially facing exclusion or segregation himself was dramatized by both the black and white press and highlighted when he received the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People’s Spingarn Medal in 1944.

A demanding yet unusually caring teacher, Drew stayed in touch with his students long after they left Howard. Between 1941 and 1950 he trained more than half the black surgeons certified by the American Board of Surgery (eight in all), and fourteen more surgeons certified after 1950 received part of their training from him. In 1942 he became the first black surgeon appointed an examiner for the American Board of Surgery. Other responsibilities and honors followed: in 1943 he was appointed a member of the American-Soviet Committee on Science, and in 1946 he was elected vice president of the American-Soviet Medical Society. From 1944 to 1946 he served as chief of staff, and from 1946 to 1948 as medical director of Freedmen’s Hospital. In 1946 he was named a fellow of the U.S. chapter of the International College of Surgeons; in 1949 he was appointed surgical consultant to the surgeon general and was sent to Europe to inspect military medical facilities.

Throughout this period Drew was struggling to open doors for his young black residents, who still were barred from practicing at most white medical institutions as well as from joining the American Medical Association (AMA) and the American College of Surgeons (ACOG). Throughout the 1940s he waged a relentless campaign through letters and political contacts to try to open up the AMA and the ACOG to black physicians; he himself joined neither.

While driving to a medical conference in Alabama, Drew died as the result of an auto accident in North Carolina. His traumatic, untimely death sparked a false rumor that grew into a historical legend during the civil rights movement era, alleging that Drew bled to death because he was turned away from a whites-only hospital. Drew’s well-publicized protest of the segregated blood policy, combined with the hospital’s refusals of many black patients during the era of segregation, undoubtedly laid the foundation for the legend that dramatized the medical deprivation Drew spent his life battling. Drew was a great American man of medicine by any measure; his extraordinary personality was best summed up by one of his oldest friends, Ben Davis: “I can never forget him: his extraordinary nobleness of character, his honesty, his integrity and fearlessness” (David Hepburn, Our World [July 1950]: 28).

The Charles R. Drew Papers are located in the Moorland-Spingarn Research Center of Howard University.

Love, Spencie. One Blood: The Death and Resurrection of Charles R. Drew (1996).

Wynes, Charles E. Charles Richard Drew: The Man and the Myth (1988).

Yancey, Asa, Sr. “U.S. Postage Stamp in Honor of Charles R. Drew, M.D., MDSc.,” Journal of the National Medical Association 74, no. 6 (1982): 561–565.

Obituaries: Journal of the National Medical Association 42, no. 4 (July 1950): 239–246; The Crisis (Oct. 1951): 501–507, 555.

—SPENCIE LOVE

DREW, TIMOTHY.

DREW, TIMOTHY.See Ali, Noble Drew.

DU BOIS, W. E. B.

DU BOIS, W. E. B.(23 Feb. 1868–27 Aug. 1963), scholar, writer, editor, and civil rights pioneer, was born William Edward Burghardt Du Bois in Great Barrington, Massachusetts, the son of Mary Silvina Burghardt, a domestic worker, and Alfred Du Bois, a barber and itinerant laborer. In later life Du Bois made a close study of his family origins, weaving them rhetorically and conceptually—if not always accurately—into almost everything he wrote. Born in Haiti and descended from mixed race Bahamian slaves, Alfred Du Bois enlisted during the Civil War as a private in a New York regiment of the Union army but appears to have deserted shortly afterward. He also deserted the family less than two years after his son’s birth, leaving him to be reared by his mother and the extended Burghardt kin. Long resident in New England, the Burghardts descended from a freedman of Dutch slave origin who had fought briefly in the American Revolution. Under the care of his mother and her relatives, young Will Du Bois spent his entire childhood in that small western Massachusetts town, where probably fewer than two-score of the four thousand inhabitants were African American. He received a classical, college preparatory education in Great Barrington’s racially integrated high school, from whence, in June 1884, he became the first African American graduate. A precocious youth, Du Bois not only excelled in his high school studies but contributed numerous articles to two regional newspapers, the Springfield Republican and the black-owned New York Globe, then edited by T. THOMAS FORTUNE.

W. E. B. Du Bois, intellectual, scholar, editor, and civil rights activist, provided a leading voice in defining the struggle for civil rights in the twentieth century. © CORBIS

In high school Du Bois came under the influence of and received mentorship from the principal, Frank Hosmer, who encouraged his extensive reading and solicited scholarship aid from local worthies that enabled Du Bois to enroll at Fisk University in September 1885, six months after his mother’s death. One of the best of the southern colleges for newly freed slaves founded after the Civil War, Fisk offered a continuation of his classical education and the strong influence of teachers who were heirs to New England and Western Reserve (Ohio) abolitionism. It also offered the northern-reared Du Bois an introduction to southern American racism and African American culture. His later writings and thought were strongly marked, for example, by his experiences teaching school in the hills of eastern Tennessee during the summers of 1886 and 1887.

In 1888 Du Bois enrolled at Harvard as a junior. He received a BA cum laude, in 1890, an MA in 1891, and a PhD in 1895. Du Bois was strongly influenced by the new historical work of German-trained Albert Bushnell Hart and the philosophical lectures of William James, both of whom became friends and professional mentors. Other intellectual influences came with his studies and travels between 1892 and 1894 in Germany, where he was enrolled at the Friedrich-Wilhelm III Universität (then commonly referred to as the University of Berlin but renamed the Humboldt University after World War II). Because of the expiration of the Slater Fund fellowship that supported his stay in Germany, Du Bois could not meet the residency requirements that would have enabled him formally to stand for the degree in economics, despite his completion of the required doctoral thesis (on the history of southern U.S. agriculture) during his tenure. Returning to the United States in the summer of 1894, Du Bois taught classics and modern languages for two years at Wilberforce University in Ohio. While there, he met Nina Gomer, a student at the college, whom he married in 1896 at her home in Cedar Rapids, Iowa. The couple had two children. By the end of his first year at Wilberforce, Du Bois had completed his Harvard doctoral thesis, “The Suppression of the African Slave Trade to the United States of America, 1638–1870,” which was published in 1896 as the inaugural volume of the Harvard Historical Studies series.

Although he had written his Berlin thesis in economic history, received his Harvard doctorate in history, and taught languages and literature at Wilberforce, Du Bois made some of his most important early intellectual contributions to the emerging field of sociology. In 1896 he was invited by the University of Pennsylvania to conduct a study of the seventh ward in Philadelphia. There, after an estimated 835 hours of door-to-door interviews in 2,500 households, Du Bois completed the monumental study, The Philadelphia Negro (1899). The Philadelphia study was both highly empirical and hortatory, a combination that prefigured much of the politically engaged scholarship that Du Bois pursued in the years that followed and that reflected the two main strands of his intellectual engagement during this formative period: the scientific study of the so-called Negro Problem and the appropriate political responses to it. While completing his fieldwork in Philadelphia, Du Bois delivered to the Academy of Political and Social Science in November 1896 an address, “The Study of the Negro Problem,” a methodological manifesto on the purposes and appropriate methods for scholarly examination of the condition of black people. In March 1897, addressing the newly founded American Negro Academy in Washington, D.C., he outlined for his black intellectual colleagues, in “The Conservation of the Races,” both a historical sociology and theory of race as a concept and a call to action in defense of African American culture and identity. During the following July and August he undertook for the U.S. Bureau of Labor the first of several studies of southern African American households, which was published as a bureau bulletin the following year under the title The Negroes of Farmville, Virginia: A Social Study. During that same summer, Atlantic Monthly published the essay “The Strivings of the Negro People,” a slightly revised version of which later opened The Souls of Black Folk (1903).

Together these works frame Du Bois’s evolving conceptualization of, methodological approach to, and political values and commitments regarding the problem of race in America. His conceptions were historical and global, his methodology empirical and intuitive, his values and commitments involving both mobilization of an elite vanguard to address the issues of racism and the conscious cultivation of the values to be drawn from African American folk culture.

After the completion of the Philadelphia study in December 1897, Du Bois began the first of two long tenures at Atlanta University, where he taught sociology and directed empirical studies—modeled loosely on his Philadelphia and Farmville work—of the social and economic conditions and cultural and institutional lives of southern African Americans. During this first tenure at Atlanta he also wrote two more books, The Souls of Black Folk, a collection of poignant essays on race, labor, and culture, and John Brown (1909), an impassioned interpretation of the life and martyrdom of the militant abolitionist. He also edited two shortlived magazines, Moon (1905–1906) and Horizon (1907–1910), which represented his earliest efforts to establish journals of intellectual and political opinion for a black readership.

With the publication of Souls of Black Folk, Du Bois emerged as the most prominent spokesperson for the opposition to BOOKER T. WASHINGTON’s policy of political conservatism and racial accommodation. Ironically, Du Bois had kept a prudent distance from Washington’s opponents and had made few overt statements in opposition to the so-called Wizard of Tuskegee. In fact, his career had involved a number of near-misses whereby he himself might have ended up teaching at Tuskegee. Having applied to Washington for a job shortly after returning from Berlin, he had to decline Tuskegee’s superior monetary offer because he had already accepted a position at Wilberforce. On a number of other occasions Washington—sometimes prodded by Albert Bushnell Hart—sought to recruit Du Bois to join him at Tuskegee, a courtship he continued at least until the summer of 1903, when Du Bois taught summer school at Tuskegee. Early in his career, moreover, Du Bois’s views bore a superficial similarity to Washington’s. In fact, he had praised Washington’s 1895 “Atlanta Compromise” speech, which proposed to southern white elites a compromise wherein blacks would forswear political and civil rights in exchange for economic opportunities. Like many elite blacks at the time, Du Bois was not averse to some form of franchise restriction, so long as it was based on educational qualifications and applied equally to white and black. Du Bois had been charged with overseeing the African American Council’s efforts to encourage black economic enterprise and worked with Washington’s partisans in that effort. By his own account his overt rupture with Washington was sparked by the growing evidence of a conspiracy, emanating from Tuskegee, to dictate speech and opinion in all of black America and to crush any opposition to Washington’s leadership. After the collapse of efforts to compromise their differences through a series of meetings in 1904, Du Bois joined WILLIAM MONROE TROTTER and other Washington opponents to form the Niagara Movement, an organization militantly advocating full civil and political rights for African Americans.

Although it enjoyed some success in articulating an alternative vision of how black Americans should respond to the growing segregation and racial violence of the early twentieth century, the Niagara Movement was fatally hampered by lack of funds and the overt and covert opposition of Washington and his allies. Indeed, the vision and program of the movement were fully realized only with the founding of a new biracial organization, the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP). The NAACP grew out of the agitation and a 1909 conference called to protest the deteriorating status of and escalating violence against black Americans. Racial rioting in August 1908 in Springfield, Illinois, the home of Abraham Lincoln, sparked widespread protest among blacks and liberal whites appalled at the apparent spread of southern violence and lynch law into northern cities. Although its officers made some initial efforts to maintain a détente with Booker T. Washington, the NAACP represented a clear opposition to his policy of accommodation and political quietism. It launched legal suits, legislative lobbying, and propaganda campaigns that embodied uncompromising, militant attacks on lynching, Jim Crow, and disfranchisement. In 1910 Du Bois left Atlanta to join the NAACP as an officer, its only black board member, and to edit its monthly magazine, the Crisis.

As editor of the Crisis Du Bois finally established the journal of opinion that had so long eluded him, one that could serve as a platform from which to reach a larger audience among African Americans and one that united the multiple strands of his life’s work. In its monthly issues he rallied black support for NAACP policies and programs and excoriated white opposition to equal rights. But he also opened the journal to discussions of diverse subjects related to race relations and black cultural and social life, from black religion to new poetic works. The journal’s cover displayed a rich visual imagery embodying the sheer diversity and breadth of the black presence in America. Thus the journal constituted, simultaneously, a forum for multiple expressions of and the coherent representation and enactment of black intellectual and cultural life. A mirror for and to black America, it inspired a black intelligentsia and its public.

From his vantage as an officer of the NAACP, Du Bois also furthered another compelling intellectual and political interest, Pan-Africanism. He had attended the first conference on the global condition of peoples of African descent in London in 1900. Six other gatherings followed between 1911 and 1945, including the First Universal Races Congress in London in 1911, and Pan-African congresses held in Paris in 1919; London, Brussels, and Paris in 1921; London and Lisbon in 1923; New York City in 1927; and in Manchester, England, in 1945. Each conference focused in some fashion on the fate of African colonies in the postwar world, but the political agendas of the earliest meetings were often compromised by the ideological and political entanglements of the elite delegates chosen to represent the African colonies. Jamaican black nationalist MARCUS GARVEY enjoyed greater success in mobilizing a mass base for his version of Pan-Africanism and posed a substantial ideological and political challenge to Du Bois. Deeply suspicious of Garvey’s extravagance and flamboyance, Du Bois condemned his scheme to collect funds from African Americans to establish a shipping line that would aid their “return” to Africa, his militant advocacy of racial separatism, and his seeming alliance with the Ku Klux Klan. Although he played no role in the efforts to have Garvey jailed and eventually deported for mail fraud, Du Bois was not sorry to see him go. (In 1945, however, Du Bois joined Garvey’s widow, AMY JACQUES GARVEY, and George Padmore to sponsor the Manchester Pan-African conference that demanded African independence. Du Bois cochaired the opening session of the conference with Carvey’s first wife, AMY ASHWOOD GARVEY.)

The rupture in world history that was World War I and the vast social and political transformations of the decade that followed were reflected in Du Bois’s thought and program in other ways as well. During the war he had written “Close Ranks,” a controversial editorial in the Crisis (July 1918), which urged African Americans to set aside their grievances for the moment and concentrate their energies on the war effort. In fact, Du Bois and the NAACP fought for officer training and equal treatment for black troops throughout the war, led a silent protest march down Fifth Avenue in 1917 against racism, and in 1919 launched an investigation into charges of discrimination against black troops in Europe. Meanwhile, the unprecedented scope and brutality of the war itself stimulated changes in Du Bois’s evolving analyses of racial issues and phenomena. Darkwater: Voices within the Veil (1920) reflects many of these themes, including the role of African colonization and the fundamental role of the international recruitment and subjugation of labor in causing the war and in shaping its aftermath. His visit to Liberia in 1923 and the Soviet Union in 1926, his subsequent study of Marxism, his growing awareness of Freud, and the challenges posed by the Great Depression all brought him to question the NAACP’s largely legalistic and propagandistic approach to fighting racism. In the early 1930s Du Bois opened the pages of the Crisis to wide-ranging discussions of the utility of Marxian thought and of racially based economic cooperatives and other institutions in the fight against race prejudice. This led to increasing antagonism between him and his colleagues at the NAACP, especially executive director WALTER WHITE, and to his resignation in June 1934.

Du Bois accepted an appointment as chair of the sociology department at Atlanta University, where he had already been teaching as a visiting professor during the winter of 1934. There he founded and edited a new scholarly journal, Phylon, from 1940 to 1944. There, too, he published his most important historical work, Black Reconstruction in America: An Essay toward a History of the Part Which Black Folk Played in the Attempt to Reconstruct Democracy in America, 1860–1880 (1935), and Dusk of Dawn: An Essay toward an Autobiography of a Race Concept (1940), his most engaging and poignant autobiographical essay since Souls of Black Folk. During this period Du Bois continued to be an active lecturer and an interlocutor with young scholars and activists; he also deepened his studies of Marxism and traveled abroad. He sought unsuccessfully to enlist the aid of the Phelps-Stokes Fund in launching his long-dreamed-of project to prepare an encyclopedia of black peoples in Africa and the diaspora. By 1944, however, Du Bois had lost an invaluable supporter and friend with the death of JOHN HOPE, the president of Atlanta University, leaving him vulnerable to dismissal following sharp disagreements with Hope’s successor.

Far from acceding to a peaceful retirement, however, in 1944 Du Bois (now seventy-six years old) accepted an invitation to return to the NAACP to serve in the newly created post of director of special research. Although the organization was still under the staff direction of Du Bois’s former antagonist, WALTER WHITE, the 1930s Depression and World War II had induced some modifications in the programs and tactics of the NAACP, perhaps in response to challenges raised by Du Bois and other younger critics. It had begun to address the problems of labor as well as legal discrimination, and even the court strategy was becoming much more aggressive and economically targeted. In hiring Du Bois, the board appears to have anticipated that other shifts in its approach would be necessary in the coming postwar era. Clearly it was Du Bois’s understanding that his return portended continued study of and agitation around the implications of the coming postwar settlement as it might affect black peoples in Africa and the diaspora, and that claims for the representation of African and African American interests in that settlement were to be pressed. He represented the NAACP in 1945 as a consultant to the U.S. delegation at the founding conference of the United Nations in San Francisco. In 1947 he prepared and presented to that organization An Appeal to the World, a ninety-four-page, militant protest against American racism as an international violation of human rights. During this period and in support of these activities he wrote two more books, Color and Democracy: Colonies and Peace (1945) and The World and Africa: An Inquiry into the Part Which Africa Has Played in World History (1947), each of which addressed some aspect of European and American responsibilities for justice in the colonial world.

As ever, Du Bois learned from and was responsive to the events and developments of his time. Conflicts with the U.S. delegation to the United Nations (which included Eleanor Roosevelt, who was also a member of the NAACP board) and disillusionment with the evolving role of America as a postwar world power reinforced his growing radicalism and refusal to be confined to a safe domestic agenda. He became a supporter of the leftist Southern Negro Youth Congress at a time of rising hysteria about Communism and the onset of the cold war. In 1948 he was an active supporter of the Progressive Party and Henry Wallace’s presidential bid. All of this put him at odds with Walter White and the NAACP board, who were drawn increasingly into collusion with the Harry S. Truman administration and into fierce opposition to any leftist associations. In 1948, after an inconclusive argument over assigning responsibility for a leak to the New York Times of a Du Bois memorandum critical of the organization and its policies, he was forced out of the NAACP for a second time.

After leaving the NAACP, Du Bois joined the Council on African Affairs, where he chaired the Africa Aid Committee and was active in supporting the early struggle of the African National Congress of South Africa against apartheid. The council had been organized in London in the late 1930s by Max Yergan and PAUL ROBESON to push decolonization and to educate the general public about that issue. In the postwar period it, too, became tainted by charges of Communist domination and lost many former supporters (including Yergan and RALPH BUNCHE); it dissolved altogether in 1955. Having linked the causes of decolonialization and antiracism to the fate of peace in a nuclear-armed world, Du Bois helped organize the Cultural and Scientific Conference for World Peace in March 1949, was active in organizing its meetings in Paris and Mexico City later that year, and attended its Moscow conference that August. Subsequently this group founded the Peace Information Center in 1950, and Du Bois was chosen to chair its Advisory Council. The center endorsed and promoted the Stockholm Peace Appeal, which called for banning atomic weapons, declaring their use a crime against humanity and demanding international controls. During this year Du Bois, who actively opposed the Korean War and Truman’s foreign policy more generally, accepted the nomination of New York’s Progressive Party to run for the U.S. Senate on the platform “Peace and Civil Rights.” Although he lost, his vote total ran considerably ahead of the other candidates on the Progressive ticket.

During the campaign, on 25 August 1950, the officers of the Peace Information Center were directed to register as “agents of a foreign principal” under terms of the Foreign Agents Registration Act of 1938. Their distribution of the Stockholm Appeal, alleged to be a Soviet-inspired manifesto, was the grounds for these charges, although the so-called foreign principal was never specifically identified in the subsequent indictment. Although the center disbanded on 12 October 1950, indictments against its officers, including Du Bois, were handed down on 9 February 1951. Du Bois’s lawyers won a crucial postponement of the trial until the following 18 November 1951, by which time national and international opposition to the trial had been mobilized. Given the good fortune of a weak case and a fair judge, Du Bois and his colleagues were acquitted. Meanwhile, following the death of his wife, Nina, in July 1950, Du Bois married Shirley Graham, the daughter of an old friend, in 1951. Although the union bore no children, David, Shirley’s son from an earlier marriage, took Du Bois’s surname.

After the trial, Du Bois continued to be active in the American Peace Crusade and received the International Peace Prize from the World Council of Peace in 1953. With Shirley, a militant leftist activist in her own right, he was drawn more deeply into leftist and Communist Party intellectual and social circles during the 1950s. He was an unrepentant supporter of and apologist for Joseph Stalin, arguing that though Stalin’s methods might have been cruel, they were necessitated by unprincipled and implacable opposition from the West and by U.S. efforts to undermine the regime. He was also convinced that American news reports about Stalin and the Soviet bloc were unreliable at best and sheer propaganda or falsehoods at worst. His views do not appear to have been altered by the Soviets’ own exposure and condemnation of Stalin after 1956.

From February 1952 to 1958 both W. E. B. and Shirley were denied passports to travel abroad. Thus he could not accept the many invitations to speak abroad or participate in international affairs, including most notably the 1957 independence celebrations of Ghana, the first of the newly independent African nations. When these restrictions were lifted in 1958, the couple traveled to the Soviet Union, Eastern Europe, and China. While in Moscow, Du Bois was warmly received by Nikita Khrushchev, whom he strongly urged to promote the study of African civilization in Russia, a proposal that eventually led to the establishment in 1962 of the Institute for the Study of Africa. While there, he also received the Lenin Peace Prize.

But continued cold war tensions and their potential impact on his ability to travel and remain active in the future led Du Bois to look favorably on an invitation in May 1961 from Kwame Nkrumah and the Ghana Academy of Sciences to move to Ghana and undertake direction of the preparation of an “Encyclopedia Africana,” a project much like one he had long contemplated. Indeed, his passport had been rescinded again after his return from China (travel to that country was barred at the time), and it was only restored after intense lobbying by the Ghanaian government. Before leaving the United States for Ghana on 7 October 1961, Du Bois officially joined the American Communist Party, declaring in his 1 October 1961 letter of application that it and socialism were the only viable hope for black liberation and world peace. His desire to travel and work freely also prompted his decision two years later to become a citizen of Ghana.

In some sense these actions brought full circle some of the key issues that had animated Du Bois’s life. Having organized his life’s work around the comprehensive, empirically grounded study of what had once been called the Negro Problem, he ended his years laboring on an interdisciplinary and global publication that might have been the culmination and symbol of that ambition: to document the experience and historical contributions of African peoples in the world. Having witnessed the formal détente among European powers by which the African continent was colonized in the late nineteenth century, he lived to taste the fruits of the struggle to decolonize it in the late twentieth century and to become a citizen of the first new African nation. Having posed at the end of the nineteenth century the problem of black identity in the diaspora, he appeared to resolve the question in his own life by returning to Africa. Undoubtedly the most important modern African American intellectual, Du Bois virtually invented modern African American letters and gave form to the consciousness animating the work of practically all other modern African American intellectuals to follow. He authored seventeen books, including five novels; founded and edited four different journals; and pursued two full-time careers: scholar and political organizer. But more than that, he reshaped how the experience of America and African America could be understood; he made us know both the complexity of who black Americans have been and are, and why it matters; and he left Americans—black and white—a legacy of intellectual tools, a language with which they might analyze their present and imagine a future.

From late 1961 to 1963 Du Bois lived a full life in Accra, the Ghanaian capital, working on the encyclopedia, taking long drives in the afternoon, and entertaining its political elite and the small colony of African Americans during the evenings at the comfortable home the government had provided him. Du Bois died the day before his American compatriots assembled for the March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom. It was a conjunction more than rich with historical symbolism. It was the beginning of the end of the era of segregation that had shaped so much of Du Bois’s life, but it was also the beginning of a new era when “the Negro Problem” could not be confined to separable terrains of the political, economic, domestic, or international, or to simple solutions such as integration or separatism, rights or consciousness. The life and work of Du Bois had anticipated this necessary synthesis of diverse terrains and solutions. On 29 August 1963 Du Bois was interred in a state funeral outside Castle Osu, formerly a holding pen for the slave cargoes bound for America.

Du Bois’s papers are at the University of Massachusetts, Amherst, and are also available on microfilm.

Du Bois, W. E. B. The Complete Published Works of W. E. B. Du Bois, comp. and ed. Herbert Aptheker (1982).

Home, Gerald. Black and Red: W. E. B. Du Bois and the Afro-American Response to the Cold War, 1944–1963 (1986).

Lewis, David Levering. W. E. B. Du Bois: Biography of a Race, 1868–1919 (1993).

_______. W. E. B. Du Bois: The Fight for Equality and the American Century, 1919–1963 (2000).

Marable, Manning. W. E. B. Du Bois: Black Radical Democrat (1986).

Rampersad, Arnold. The Art and Imagination of W. E. B. Du Bois (1976).

Obituary: New York Times, 28 Aug. 1963.

—THOMAS C. HOLT

DUNBAR, PAUL LAURENCE

DUNBAR, PAUL LAURENCE(27 June 1872–9 Feb. 1906), author, was born in Dayton, Ohio, the son of Joshua Dunbar, a plasterer, and Matilda Burton Murphy, a laundry worker. His literary career began at age twelve, when he wrote an Easter poem and recited it in church. He served as editor in chief of his high school’s student newspaper and presided over its debating society. While still in school, he contributed poems and sketches to the Dayton Herald and the West Side News, a local paper published by Orville Wright of Kitty Hawk fame, and briefly edited the Tattler, a newspaper for blacks that Wright published and printed. He graduated from high school in 1891 with the hope of becoming a lawyer, but, lacking the funds to pursue a college education, he went instead to work as an elevator operator.

Dunbar wrote and submitted poetry and short stories in his spare time. His first break came in 1892, when the Western Association of Writers held its annual meeting in Dayton. One of Dunbar’s former teachers arranged to have him deliver the welcoming address, and his rhyming greeting pleased the conventioneers so much that they voted him into the association. One of the attendees, poet James Newton Matthews, wrote an article about Dayton’s young black poet that received wide publication in the Midwest, and soon Dunbar was receiving invitations from newspaper editors to submit his poems for publication. Encouraged by this success, he published Oak and Ivy (1893), a slender volume of fifty-six poems that sold well, particularly after Dunbar, an excellent public speaker, read selections from the book before evening club and church meetings throughout Ohio and Indiana.

In 1893 Dunbar traveled to Chicago, Illinois, to write an article for the Herald about the World’s Columbian Exposition. He decided to stay in the Windy City and found employment as a latrine attendant. He eventually obtained a position as clerk to FREDERICK DOUGLASS, who was overseeing the Haitian Pavilion, as well as a temporary assignment from the Chicago Record to cover the exposition. After a rousing Douglass speech, the highlight of the exposition’s Negro American Day, Dunbar read one of his poems, “The Colored Soldiers,” to an appreciative audience of thousands. Sadly, when the exposition closed, Chicago offered Dunbar no better opportunity for full-time employment than his old job as elevator boy, and so he reluctantly returned to Dayton. However, he did so with Douglass’s praise ringing in his ears: “One of the sweetest songsters his race has produced and a man of whom I hope great things.”

Dunbar’s determination to become a great writer was almost derailed by a chance to pursue his old dream of becoming a lawyer. In 1894 a Dayton attorney hired him as a law clerk with the understanding that Dunbar would have the opportunity to study law on the side. However, Dunbar discovered that law no longer enthralled him as it once had; moreover, he found that working and studying left him no time to write, and so he returned to the elevator and his poetry. He soon had enough new poems for a second volume, Majors and Minors (1895), which was published privately with the financial backing of H. A. Tobey of Toledo, Ohio. This work contains poems in both standard English (“majors”) and black dialect (“minors”), many of which are regarded as among his best. In 1896 William Dean Howells, at the time America’s most prominent literary critic, wrote a lengthy and enthusiastic review of Majors and Minors’s dialect poems for Harper’s Weekly, a highly regarded literary magazine with a wide circulation. The review gave Dunbar’s career as a poet a tremendous boost. Sales of Majors and Minors skyrocketed, and Dunbar, now under the management of Major James Burton Pond’s lecture bureau, embarked on a national reading tour. Pond also arranged for Dodd, Mead and Company to publish Lyrics of Lowly Life (1896), a republication of ninety-seven poems from Dunbar’s first two volumes and eight new poems. Howells, in the introduction to this volume, described Dunbar as “the only man of pure African blood and of American civilization to feel the negro life aesthetically and express it lyrically.” The combination of Howells’s endorsement and Dunbar’s skill soon led the latter to become one of America’s most popular writers.

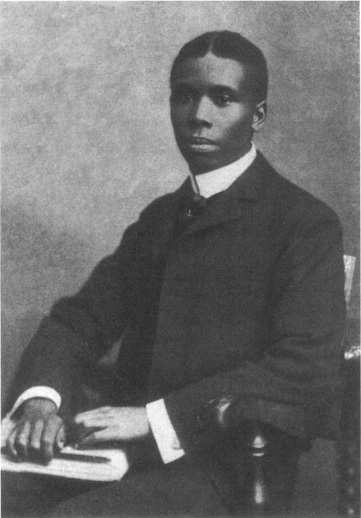

Paul Laurence Dunbar, as shown in the frontispiece to his Lyrics of Sunshine and Shadow, 1905. Library of Congress

After the publication of Lyrics of Lowly Life, Dunbar went on a reading tour of England. When he returned to the United States in 1897, he accepted a position as a library assistant at the Library of Congress in Washington, D.C. Meanwhile, several national literary magazines were vying for anything he wrote, and in 1898 Dunbar seemed to have developed the golden touch. Lippincott’s Monthly Magazine published his first novel, The Uncalled, which appeared in book form later that year; Folks from Dixie, a collection of twelve short stories that had been published individually in various magazines, also came out in book form; and he collaborated with WILL MARION COOK to write a hit Broadway musical, Clorindy. At this time he developed a nagging cough, perhaps the result of an abundance of heavy lifting in the dusty, drafty library combined with skimping on sleep while pursuing deadlines. Partly because of his success and partly because of ill health, he resigned from the library at the end of 1898 to devote himself full time to his writing.

In 1899 Dunbar published two collections of poems, Lyrics of the Hearthside and Poems of Cabin and Field, and embarked on a third reading tour. However, his health deteriorated so rapidly that the tour was cut short. The official diagnosis was pneumonia, but his doctor suspected that Dunbar was in the early stages of tuberculosis. To help ease the pain in his lungs, he turned to strong drink, which did little more than make him a near-alcoholic. He gave up his much-beloved speaking tours but continued to write at the same breakneck pace. While convalescing in Denver, Colorado, he wrote a western novel, The Love of Landry (1900), and published The Strength of Gideon and Other Stories (1900), another collection of short stories. He also wrote two plays, neither of which was ever published, as well as some lyrics and sketches. In the last five years of his life, he published two novels, The Fanatics (1901) and The Sport of the Gods (1901, in Lippincott’s; 1902, in book form); two short story collections, In Old Plantation Days (1903) and The Heart of Happy Hollow (1904); eight collections of poetry, Candle-Lightin’ Time (1901), Lyrics of Love and Laughter (1903), When Malindy Sings (1903), Li’l Gal (1904), Chris’mus Is A-comin’ and Other Poems (1905), Howdy, Honey, Howdy (1905), Lyrics of Sunshine and Shadow (1905), and Joggin’ Erlong (1906); and collaborated with Cook on another musical, In Dahomey (1902).

Dunbar had married writer Alice Ruth Moore (ALICE DUNBAR-NELSON) in 1898; they had no children. In 1902 the couple separated, largely because of Dunbar’s drinking, and never reconciled. After the breakup Dunbar lived in Chicago for a while, then in 1903 returned to live with his mother in Dayton, where he died of tuberculosis in 1906.

Dunbar’s goal was “to interpret my own people through song and story, and to prove to the many that after all we are more human than African.” In so doing, he portrayed the lives of blacks as being filled with joy and humor as well as misery and difficulty. Dunbar is best known for his dialect poems that, intended for a predominantly white audience, often depict slaves as dancing, singing, carefree residents of “Happy Hollow.” On the other hand, a great deal of his lesser-known prose work speaks out forcefully against racial injustice, both before and after emancipation, as in “The Lynching of Jube Benson,” a powerful short story about the guilt that haunts a white man who once participated in the hanging of an innocent black. Perhaps his two most eloquent expressions of the reality of the black experience in America are “We Wear the Mask,” in which he declares, “We wear the mask that grins and lies, . . . /We smile, but, O great Christ, our cries /To thee from tortured souls arise,” and “Sympathy,” wherein he states that “I know why the caged bird sings, . . . /It is not a carol of joy or glee, /But a prayer . . . that upward to Heaven he flings.”

Dunbar was the first black American author to be able to support himself solely as a result of his writing. His success inspired the next generation of black writers, including JAMES WELDON JOHNSON, LANGSTON HUGHES, and CLAUDE MCKAY, to dream of and achieve literary success. Dunbar was celebrated and scrutinized by the national media as a representative of his race. His charm and wit, his grace under pressure, and his ability as a speaker and author did much to give the lie to turn-of-the-century misconceptions about the racial inferiority of blacks.

Dunbar’s papers are in the archives of the Ohio Historical Society.

Gentry, Tony. Paul Laurence Dunbar (1989).

Martin, Jay, and Gossie H. Hudson, eds. The Paul Laurence Dunbar Reader (1975).

Williams, Kenny J. They Also Spoke: An Essay on Negro Literature in America, 1787–1930 (1970).

Obituary: New York Times, 10 Feb. 1906.

—CHARLES W. CAREY JR.

DUNBAR-NELSON, ALICE

DUNBAR-NELSON, ALICE(19 July 1875–18 Sept. 1935), writer, educator, and activist, was born Alice Ruth Moore in New Orleans to Joseph Moore, a seaman, and Patricia Wright, a former slave and seamstress. Moore completed a teachers’ training program at Straight College (now Dillard University) and taught in New Orleans from 1892 to 1896, then in Brooklyn, New York City, from 1897 to 1898. Demonstrating a commitment to the education of African American girls and women that would continue throughout her life, Moore helped found the White Rose Home for Girls in Harlem in 1898.

Moore’s primary ambition, however, was literary, and she published her first book at the age of twenty, Violets and Other Tales (1895), a collection of poetry in a classical lyric style, essays, and finely observed short stories. The publication of Moore’s poetry and photograph in a Boston magazine inspired the famed poet PAUL LAURENCE DUNBAR to begin a correspondence with her that led to their marriage in 1898. Her second book, The Goodness of St. Rocque and Other Stories (1899), a collection of short stories rooted in New Orleans Creole culture, was published as a companion volume to Dunbar’s Poems of Cabin and Field, and their marriage was celebrated as a literary union comparable to that of Robert and Elizabeth Barrett Browning. The couple separated, however, in 1902, after less than four tumultuous and sometimes violent years, due in part to Paul’s alcoholism. Paul Laurence Dunbar died of tuberculosis four years later. Although the couple never reconciled, Alice Dunbar expressed regret and outrage that his family did not inform her of his last illness, or even his death, which she learned of from a newspaper article.

In the fall of 1902 Alice Dunbar resumed her teaching career at Howard High School in Wilmington, Delaware. As an English and drawing instructor, then head of the English department, Dunbar also served as an administrator and directed several of her own plays at the school. Dunbar also pursued scholarly work at various institutions, including Columbia University and the University of Pennsylvania, ultimately completing an MA degree at Cornell University. A portion of her master’s thesis on the influence of Milton on Wordsworth was published in the prestigious Modern Language Notes in 1909. In 1910 Dunbar secretly married a fellow Howard High School teacher, Henry Arthur Callis, although they soon divorced.

During this busy period of teaching, administration, and study, Dunbar also participated in the burgeoning black women’s club movement, through which she delivered lectures on a variety of subjects, most commonly race, women’s rights, and education. However, she achieved the most renown when speaking as the widow of Paul Laurence Dunbar. Like her late husband, she struggled with the preference among white audiences for Paul’s “dialect” poetry, although she ably performed these works, along with his “pure English poems,” which she preferred. Building on her work as a public speaker, Dunbar edited and published Masterpieces of Negro Eloquence (1914), a collection of Negro oratory from the pre-and post-Civil War era, designed to celebrate the fiftieth anniversary of the Emancipation Proclamation.

In 1916 Dunbar married Robert J. Nelson, a widower with two children, but maintained her association with her first husband by hyphenating her name. In The Dunbar Speaker and Entertainer: The Poet and His Song (1920), Dunbar-Nelson assembled a wider range of Negro oratory than in the political speeches of Masterpieces of Negro Eloquence, and included a large number of her husband’s and her own poetry deemed suitable for performance, along with poetry, fiction, and speeches by JAMES WELDON JOHNSON, CHARLES W. CHESNUTT, and others. Dunbar-Nelson seems to have found her lifelong connection to her first husband both an asset, in furthering her writing and speaking career, and a burden, evidenced by several unsuccessful attempts to publish under a pseudonym.

Dunbar-Nelson’s third marriage was satisfying both personally and professionally; as a journalist Nelson was supportive of Dunbar-Nelson’s writing and political activities. Dunbar-Nelson combined her literary and political interests through the production and publication of Mine Eyes Have Seen the Glory (1918), a play promoting African American involvement in World War I. She also toured the South for the Women’s Committee for National Defense on behalf of the war effort and was active in the campaign for women’s suffrage. She continued her political activism despite protests from her employers at Howard High, and in 1920 lost her job following an unsanctioned trip to a Social Justice conference in Ohio.

Relieved of her teaching duties, Dunbar-Nelson devoted herself more fully to political activism, and from 1920 to 1922 enjoyed a close collaboration with her husband through their publication of the liberal black newspaper, the Wilmington Advocate. She joined a delegation of black activists to meet with President Warren G. Harding in 1921, worked for passage of the Dyer Anti-Lynching Bill in 1922, and organized black women voters for the Democratic Party in 1924. As a member of the Federation of Colored Women, she cofounded the Industrial School for Colored Girls in Marshalltown, Delaware, and worked as a teacher and parole officer for the school from 1924 to 1928.

Dunbar-Nelson’s journalistic and historical writings date from 1902, when she wrote several articles for the Chicago Daily News. In 1916 her lengthy historical work “People of Color in Louisiana” was published in The Journal of Negro History, and from 1926 to 1930 she was a newspaper columnist for the Pittsburgh Courier and the Washington Eagle. Many of her columns were syndicated by the Associated Negro Press, and her subjects ranged beyond the usual material considered suitable for women journalists, taking on political and social issues of the day, which she dealt with in a witty and incisive style. By contrast, many of Dunbar-Nelson’s literary efforts, including four novels, went unpublished in her lifetime, although the best of them are now collected in a three-volume set, The Works of Alice Dunbar-Nelson (1988). Included are previously published and unpublished works of poetry, fiction, essays, and drama, which give evidence of Dunbar-Nelson’s wide range of interests, both thematically and formally.

Dunbar-Nelson’s exquisitely crafted fiction secures her position as a pioneer of the African American short story. Interestingly, her fiction and poetry, which she considered the most “pure” from a literary point of view, deal only tangentially with the racial issues that so occupied her political and journalistic activities. In these works she focuses instead on issues of gender oppression and psychology, and evidences a frustration in her diary at the lack of interest from mainstream white publishers. The African American press was more receptive to her literary work, and between 1917 and 1928 Dunbar-Nelson published poems in Crisis, Opportunity, Ebony and Topaz, and other African American journals, enjoying a small heyday as a poet with the advent of the Harlem Renaissance.

In addition to recording her often frustrated literary ambitions, Dunbar-Nelson’s diary, begun in 1921, offers a glimpse of her romantic relationships with both men and women, her lifelong worries about finances, and her struggle with traditional women’s roles. Even in her mostly amicable relationship with Robert Nelson, Dunbar-Nelson objects to his insistence on her managing both household and professional duties, and she chafes at the regulation of her dress and makeup by male employers. The extant portions of the diary include the years 1921 and 1926–1931, and were published as Give Us Each Day: The Diary of Alice Dunbar-Nelson (1984).