EARLEY, CHARITY ADAMS

EARLEY, CHARITY ADAMS EARLEY, CHARITY ADAMS

EARLEY, CHARITY ADAMS(5 Dec. 1917–13 Jan. 2002), commander of the only African American unit of the Women’s Army Corps stationed in Europe during World War II, was born Charity Edna Adams, the eldest of four children. She was raised in Columbia, South Carolina, where her father was a minister in the African Episcopal Methodist Church. Her mother was a former teacher.

Adams graduated from Booker T. Washington High School in Columbia as valedictorian of her senior class and then from Wilberforce University in Ohio, one of the top three black colleges in the nation in the 1930s. She majored in Math and Physics and graduated in 1938. After returning to Columbia, where she taught junior high school mathematics for four years, Adams enrolled in the MA program for vocational psychology at Ohio State University, pursuing her degree during the summers.

As a member of the military’s Advisory Council to the Women’s Interests Section (ACWIS), MARY MCLEOD BETHUNE, president of the National Council of Negro Women, had fought for the inclusion of black women in the newly formed Women’s Army Auxiliary Corps (WAAC) in 1942. The dean of women at Wilberforce identified Adams as a potential candidate with both the education and the character to become a fine female officer. Intrigued by the possibilities of military service, Adams applied in June 1942 and in July 1942 she became the first of four thousand African American women to join what became the Women’s Army Corp (WAC). She was one of thirty-nine black women enrolled in the first officer candidate class at the First WAAC Training Center at Fort Des Moines in Iowa, where she was stationed for two and a half years, achieving the rank of major.

The armed forces were segregated in World War II, and Adams suffered indignities from those racist policies, but she handled them with great fortitude and tenacity. One of these incidents happened at Fort Des Moines when a white colonel upbraided her for visiting the all-white officers’ club with a major who had invited her there. She was forced to stand at attention for forty-five minutes while the colonel scolded her for “race mixing” and told her that black people needed to respect separation of the races even if they were officers. Indignant, Adams never entered the officers’ club again. Adams also encountered American segregation policies in England, where she commanded the only African American WAC unit to serve overseas, a postal unit stationed in Birmingham and then in France. The American Red Cross, working with the U.S. Army, pressured Adams to move her unit from integrated accommodations to a designated London hotel and sent her equipment to be used at a segregated recreational area. Adams refused the move and the equipment, insisting that her unit continue using its integrated facility, and she persuaded her troops not to change their lodgings.

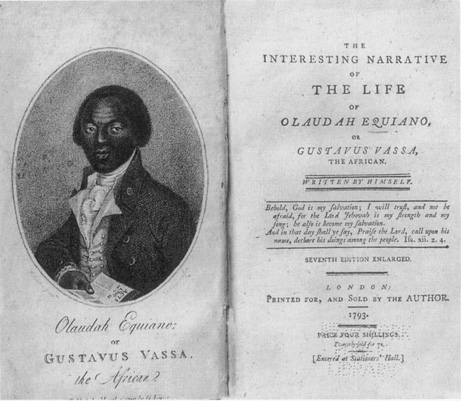

Major Charity E. Adams (later Charity Adams Earley) inspects the first African American contingent of the Women’s Army Corps assigned overseas, 1945. National Archives and Records Administration

Adams also battled occupational segregation within the army. African Americans were routinely assigned menial service jobs and denied access to office work or skilled jobs. Army labor requisitions for WAC personnel often were for administrative jobs, but these were regularly reserved for white women. In an effort to break down these barriers, Adams was sent to the Pentagon in 1943 along with the African American Major Harriet West, assistant to the WAC leader Oveta Culp Hobby, to increase quotas of black women in motor transport and other jobs. They received nominal support from the Pentagon, but racial discrimination in job assignments remained a problem throughout the war for both male and female African American soldiers.

As a black woman in uniform during the 1940s, Adams was subjected to the tensions confronting all black soldiers on the home front as well. On her first visit home to Columbia in December 1942, she accompanied her father to a meeting of the Columbia chapter of the NAACP, which he headed, to discuss the mistreatment of black soldiers by white military police at nearby Fort Jackson. Upon returning home, they discovered that the Ku Klux Klan had parked a line of cars in front of their house. Adams’s father gave the family his shotgun to protect themselves while he went to the home of the NAACP state head, only to find that home similarly surrounded and the family was out of town. In her autobiography Adams recounts the tense night that followed, as she kept watch over the hooded Klan members until dawn, when they left.

Adams also describes an incident in 1944 at an Atlanta train station, when she was asked by two white military police to produce identification. Several whites in the segregated waiting room had cast doubt on her status as an army officer. Even though she was with her parents, this was a dangerous encounter for Adams. The previous year a black army nurse in Alabama had been beaten by police and jailed for boarding a bus ahead of white passengers, and three African American WACs stationed at Fort Knox, Kentucky, had been similarly beaten for failing to move from the white area of a Greyhound bus station. Despite the risk, Adams took charge by interrogating the MPs herself and demanding the name of their commanding officer so that she could file a report on them if they did not respect her rank. The MPs saluted and disappeared.

After the war Adams returned to Ohio State and completed her MA in 1946, after which she served as a registration officer for the Veteran’s Administration in Cleveland, as manager of a music school at the Miller Academy of Fine Arts, and as dean of student personnel services at Tennessee Agricultural and Industrial State College and then at Georgia State College. On 24 August 1949, she married a physician, Stanley Earley Jr. Accompanying him to the University of Zurich, where he was a medical student, she learned German and took courses at the university and at the Jungian Institute of Analytical Psychology. Earley returned to the United States with her husband after he completed his training, and they had two children, a son and a daughter. The family settled in Dayton, Ohio, where she was actively involved in community affairs, serving on boards for social services, education, civic affairs, and corporations.

In 1989 Earley published a memoir of her wartime service, One Woman’s Army. The courage and leadership Earley displayed in her pioneering role in the U.S. Army earned her an award for distinguished service in 1946 from the National Council of Negro Women and, decades later, a place on the Smithsonian Institution’s listing of the most historically important African American women. In 1996 the Smithsonian’s National Postal Museum also honored Adams’s wartime service. She died in Dayton at the age of eighty-three, having established a permanent place in history for her trail-blazing accomplishments in World War II.

Earley, Charity Adams. One Woman’s Army: A Black Officer Remembers the WAC (1989).

Jones, Jacqueline. Labor of Love, Labor of Sorrow: Black Women, Work, and the Family from Slavery to the Present (1985).

Meyer, Leisa D. Creating G.I. Jane: Sexuality and Power in the Women’s Army Corps during World War II (1996).

Putney, Martha. When the Nation Was in Need: Blacks in the Women’s Army Corps during World War II (1992).

Obituary: New York Times, 22 Jan. 2002.

—MAUREEN HONEY

EDELMAN, MARIAN WRIGHT

EDELMAN, MARIAN WRIGHT(6 June 1939–), civil rights attorney and founder of the Children’s Defense Fund, was born Marian Wright in Bennettsville, South Carolina, to Arthur Jerome Wright, a Baptist minister, and Maggie Leola Bowen, an active churchwoman. Both parents were community activists who took in relatives and others who could no longer care for themselves, eventually founding a home for the aged that continues to be run by family members. The Wrights also built a playground for black children denied access to white recreational facilities, and nurtured in their own children a sense of responsibility and community service. As soon as Marian and her siblings were old enough to drive, they continued the family tradition of delivering food and coal to the poor, elderly, and sick. Arthur Wright also encouraged his children to read about and to revere influential African Americans like MARY MCLEOD BETHUNE and MARIAN ANDERSON (for whom Marian Wright was named).

Marian Wright experienced racial injustice from an early age, despite the efforts of her parents and other elders to protect their children from the harshest excesses of segregation. Maggie Wright was choir director, organist, and coordinator of church and community youth activities and could not always be with her children; thus neighbors and parishioners often looked after the Wright children. Such communal parenting provided Edelman with a series of strong black female role models. These women, she later wrote, became “lanterns” for her childhood and adult life.

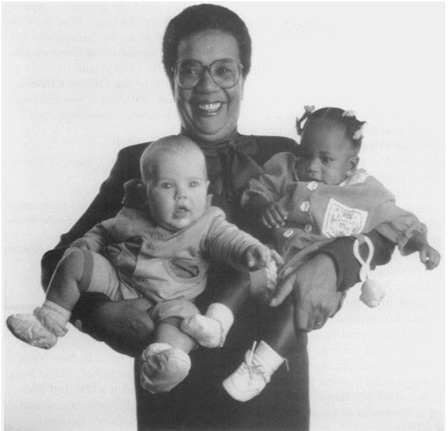

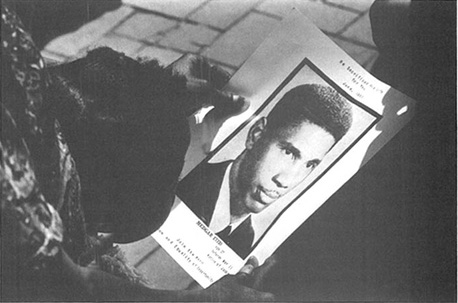

Marian Wright Edelman, president of the Children’s Defense Fund, whose mission since 1973 has been to “Leave No Child Behind.” Corbis

In 1956, two years after her father’s death, Wright entered Spelman College in Atlanta, Georgia. There she met several people who became influential mentors, including the historian Howard Zinn, the educator and civil rights advocate BENJAMIN MAYS, and MARTIN LUTHER KING JR. At Spelman, she continued the deep religious commitment of her childhood. Her diaries from that time record her prayers, asking God to “help me do the right thing and to be sincere and honest,” to “teach us to seek after truth relentlessly, and to yearn for the betterment of mankind by endless sacrifice” (Edelman, 61, 64). This centrality of faith to her daily life persisted throughout Wright’s career. She later identified her life’s work as a desire to emulate her mentors in “seeking to serve God and a cause bigger than ourselves” (Edelman, 53).

During her junior year she received a Charles Merrill scholarship that provided a year of European study and travel to Paris, Geneva, and several Eastern Bloc nations. That experience, she wrote in her diary, changed her life. “I could never return home to the segregated South and constraining Spelman College in the same way” (Edelman, 43). Marian Wright was not alone. Inspired by the February 1960 sit-in protests at segregated North Carolina lunch counters, thousands of young black southerners began to actively resist Jim Crow. That spring Wright was arrested with other Atlanta students during a sit-in, and she helped develop a student document, “An Appeal for Human Rights,” that was published in both the white-owned Atlanta Constitution and the Atlanta Daily World, a publication produced by, and primarily read by, African Americans. At Easter, she joined several hundred students, primarily from the South, at a gathering in Raleigh, North Carolina, initiated by ELLA BAKER of the Southern Christian Leadership Conference. That meeting resulted in Wright’s participation in the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC).

In May 1960 Wright graduated from Spelman as class valedictorian and entered Yale University Law School that fall. Having abandoned her earlier plans of studying Russian literature or preparing for the foreign service, she now determined that mastering the law would best prepare her for assisting the black freedom struggle. While at Yale, Wright continued her civil rights commitment through the Northern Students’ Movement, a support group for SNCC, and by visiting civil rights workers in Mississippi. During the summer of 1962, she traveled to the Ivory Coast under the Crossroads Africa student cultural exchange program founded by JAMES H. ROBINSON. After graduating from Yale in 1963, Wright spent one year preparing to become a civil rights attorney by working for the NAACP Legal Defense and Educational Fund in New York.

In 1964 Wright moved south to direct the LDF’s activities in Jackson, Mississippi. She arrived during “freedom summer,” a major voter-registration campaign that helped her forge relationships with ROBERT P. MOSES, FANNIE LOU HAMER, Mae Bertha Carter, UNITA BLACKWELL, and other civil rights leaders. Wright remained in Jackson for four years and became the first black woman admitted to the Mississippi bar. She also successfully supported continued federal funding for the Child Development Group of Mississippi (CDGM), one of the nation’s largest Head Start programs. CDGM, founded as part of President Lyndon Johnson’s War on Poverty, was strongly opposed by conservatives in Mississippi and the state’s all-white Congressional delegation, who viewed the organization as too radical. To the extent that CDGM wanted to end poverty and inequality for all Mississippians, it was radical, indeed, revolutionary. Wright also filed and won a school integration lawsuit that began the process of fully desegregating Mississippi schools.

As a result of her civil rights practice and work for the poor in Mississippi, Wright testified before the U.S. Senate in 1967 about hunger and poverty in the state. Prompted by Wright’s compelling testimony, Senator Robert Kennedy visited Mississippi to examine her assertions of extreme economic deprivation. Wright guided Kennedy on this fact-finding trip, which resulted in immediate federal commodity and, later on, in expansions of the federal food stamp program. Wright also encouraged Martin Luther King Jr. to launch the Poor People’s Campaign, to dramatize the problems of poverty in America, and later served as an attorney for that effort following King’s assassination in April 1968. That July, Wright married Peter Edelman, a prominent aide to Senator Kennedy. The couple had three sons, Joshua, Jonah, and Ezra.

Edelman moved to Washington in 1968 and continued her civil rights and antipoverty work through a Field Foundation grant that enabled her to found the Washington Research Project (WRP), a public-interest law firm that lobbied for child and family well-being, and for expanding Head Start and other anti-poverty programs. Three years later she moved with her husband to Boston, where she directed the Harvard Center for Law and Education from 1971 to 1973. In 1973 the WRP became the parent organization for the Children’s Defense Fund (CDF), whose mission has been to “Leave No Child Behind.” Under Edelman’s presidency, the CDF has promoted a “healthy start,” a “head start,” a “fair start,” a “safe start,” and a “moral start” for all children. By tackling children’s welfare, health care, and employment issues, as well as teenage pregnancy and adoption, the CDF became the nation’s largest and most successful child advocacy organization. It has several local and state affiliates in many states. At its retreat center on a farm once owned by the Roots author ALEX HALEY in Clinton, Tennessee, the CDF focuses on Edelman’s vision of transforming America by building a movement for children. CDF programs draw on the methods and lessons of the civil rights movement, for example, in the freedom school trainers program, which exposes young people to civil rights veterans and history. Those selected by the CDF to teach young adults are called Ella Baker Trainers, in honor of her role as a mentor for thousands of young activists like Marian Wright, Bob Moses, and STOKELY CARMICHAEL. The CDF’s annual Samuel DeWitt Proctor Institute also reflects Edelman’s roots in the black church through its workshops, worship, singing, and inspirational preaching and teaching.

Edelman’s tenacious defense of children’s rights has earned her respect, opportunity, and honors. From 1976 to 1987 she chaired the Spelman College trustee board, becoming the first woman to hold that post. From 1971 to 1977 she served as a member of the Yale University Corporation, the first woman elected by alumni to this position. She has received numerous awards and honors, including the nation’s highest civilian award, the Presidential Medal of Freedom, in 2000, a MacArthur Foundation Fellowship in 1985, the AFL-CIO Humanitarian Award in 1989, and honorary degrees from more than thirty colleges and universities. She has also been praised for several books on child advocacy and child rearing, including Families in Peril: An Agenda for Social Change (1987), Stand for Children (1998), and Hold My Hand: Prayers for Building a Movement to Leave No Child Behind (2001).

Edelman actively continues her CDF work, which remains as necessary today as when she founded the organization three decades ago. Her close friendship with her fellow Yale Law School graduate and CDF activist, Hillary Rodham Clinton, led to speculation that the CDF might wield considerable influence in the White House, when Clinton’s husband, Bill Clinton, was elected president in 1992. However, in 1996 Edelman opposed President Clinton for supporting welfare reform legislation that she believed would worsen child poverty. Edelman has also criticized Clinton’s successor, George W. Bush, who appropriated the CDF’s “leave no child behind” motto as a campaign slogan but has shown little interest in backing up such rhetoric with meaningful legislation. Responding to President Bush’s State of the Union address in 2002, Edelman stated:

The President’s economic plan so far has favored the wealthiest one percent of Americans. This nation should not give another tax break to the wealthy or corporate America or make permanent existing tax breaks for the wealthiest individuals and companies until there are no more hungry, homeless, poor children. For the annual cost of what the President has already approved in tax cuts to the top one percent of taxpayers, we could pay for child care, Head Start, and health care for all of the children who still need it—as proposed in the comprehensive Act to Leave No Child Behind.

(“Statement by the Children’s Defense Fund,” 30 Jan. 2002, http://www.childrens-defense.org/statement-stateofunion.php.)

Edelman, Marian Wright. Lanterns: A Memoir of Mentors (1999).

Greenberg, Jack. Crusaders in the Courts: How a Dedicated Band of Lawyers Fought for the Civil Rights Revolution (1994).

—ROSETTA E. Ross

EDWARDS, HARRY THOMAS

EDWARDS, HARRY THOMAS(3 Nov. 1940–), federal judge, was born in New York City. Raised by his mother, Arline Ross, a psychiatric social worker, and his father, George F. Edwards, an accountant and state legislator, Edwards enjoyed a very close relationship with his maternal grandfather, a tax attorney, and two uncles who also were lawyers. His decision to attend law school after graduating with a BS degree from Cornell University in 1964 was due to his admiration of his grandfather and encouragement from his two uncles.

In 1962 Edwards entered the University of Michigan Law School, where he achieved a stellar academic record. He served as an editor of the Michigan Law Review, was selected for membership in the Order of the Coif, a legal honor society reserved for the top 5 percent of students, and received American Jurisprudence Awards for outstanding performance in labor law and administrative law. As a result of this record, Edwards earned a JD degree with distinction in 1965.

Edwards began his professional career as an associate attorney with the Chicago firm of Seyfarth, Shaw, Fairweather, and Geraldson, where he practiced law in the labor department from 1965 to 1970. Leaving the firm in 1970 to begin a teaching career at the University of Michigan Law School, he served as an associate professor of law from 1970 to 1973, and later as professor of law from 1973 to 1975. From January to June 1974 he was a visiting professor at the Free University of Brussels, participating in the Program for International Legal Cooperation. In 1975 Edwards began teaching at Harvard, where in 1976 he became only the third African American awarded tenure at Harvard Law School. While at Harvard, Edwards taught labor law, collective bargaining and labor arbitration, and negotiation and labor-relations law in the public sector. In 1977 Edwards rejoined the law faculty at the University of Michigan Law School. During his time at the university, Edwards also served as a member and then chair of the board of directors of AMTRAK, the largest passenger railroad company in the United States.

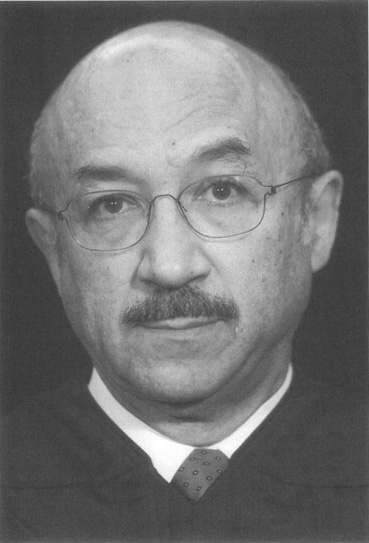

Harry T. Edwards, chief judge of the District of Columbia Circuit. © Reuters NewMedia Inc./CORBIS

In 1980 President Jimmy Carter appointed Edwards to the U.S. Court of Appeals for the District of Columbia, the most influential federal appeals court in the nation. Since joining the bench, Edwards has written hundreds of notable opinions, including decisions involving issues such as labor and employment, antitrust, administrative, tax, constitutional, civil rights, and criminal law. In his twenty-two years on the bench, Edwards developed a reputation for meticulous and thorough preparation for oral argument, as well as superbly crafted, tightly organized, and carefully annotated opinions.

In December 1982 Edwards was recognized by the American Lawyer as an Outstanding Performer in the legal profession for his judicial opinions in the area of labor law, and he continued to write important opinions in labor law in the 1990s. One such opinion was Association of Flight Attendants, AFL CIO v. USAir, Inc. (1994) where the court was faced with the question of whether flight attendants employed by an airline that had been purchased by USAir were subject to the airline’s collective-bargaining agreement with its own flight attendants. In his opinion, Edwards held that USAir’s collective bargaining agreement did not apply to the new flight attendants because a “mere change in union representative had no effect on the status quo applicable to shuttle flight attendants.” Thus the newly acquired flight attendants were able to adhere to the terms of their premerger collective bargaining agreement.

Edwards has been recognized for a series of articles regarding legal teaching and scholarship. In “The Growing Disjunction between Legal Education and the Legal Profession,” in Michigan Law Review Vol. 91 (1) (1992), he argues that law schools are failing to educate students adequately by overemphasizing abstract theory at the expense of practical scholarship and pedagogy and that law firms are failing to ensure that lawyers practice law in an ethical manner. The article sparked a national debate among legal scholars and practitioners on the proper method of legal teaching and reform in law schools and law firms. Another of his articles, “The Effects of Collegiality on Judicial Decision Making,” in Pennsylvania Law Review Vol. 151 (2003), explains how appellate judges decide cases. Edwards specifically refutes the common claim that the personal ideologies and political leanings of the judges on the District of Columbia Circuit are deciding factors in the ultimate holdings of the court. Despite his judicial duties, Edwards has also continued to influence students by teaching on a part-time basis at a number of law schools, including Harvard, Michigan, Pennsylvania, Georgetown, Duke, and New York University. Over the course of his teaching and judicial career, Edwards has found time to coauthor four critically acclaimed books: Labor Relations Law in the Public Sector (3rd edition 1985), The Lawyer as a Negotiator (1977), Collective Bargaining and Labor Arbitration (1979), and Higher Education and the Law (1979, annual supplements 1980–1983). He has also published numerous articles and pamphlets concerning issues in labor law, equal-employment opportunity, labor arbitration, higher education, alternative-dispute resolution, federalism, judicial process and administration, and comparative law.

Edwards became chief judge of the District of Columbia Circuit in 1994. During his seven-year stint as chief judge, he directed numerous automation initiatives at the court of appeals, oversaw a complete reorganization of the clerk’s office and legal division, implemented case management programs that helped to reduce the court’s case backlog and disposition times, and successfully pursued congressional support for the construction of an annex to the courthouse building. He also established programs to enhance communications with the lawyers who practice before the court, and received high praise from members of the bench, bar, and press for fostering collegial relations among the members of the ideologically divided court. In 2000–2001 Edwards presided over the court’s hearings in United States v. Microsoft, the largest antitrust case in U.S. history. In this case, the court reviewed the legal conclusions regarding three alleged antitrust violations and the resulting remedial order imposed on Microsoft by the United States District Court for the District of Columbia. Edwards participated in the court’s per curiam opinion that affirmed in part and reversed in part the district court’s judgment that Microsoft violated section 2 of the Sherman Act.

In July 1996 the American Lawyer and the Washington Legal Times published personal profiles of Edwards, applauding his efforts in managing the District of Columbia Circuit as chief judge and in helping to bring collegiality to the court. Edwards stepped down from his position as chief judge in July 2001.

Edwards has served on numerous boards, including the board of directors of the National Institute for Dispute Resolution, the executive committee of the Order of the Coif, the executive committee of the Association of American Law Schools, and the National Academy of Arbitrators (as vice president). His numerous awards include the Society of American Law Teachers Award, recognizing distinguished contributions to teaching and public service; the Whitney North Seymour Medal, presented by the American Arbitration Association for outstanding contributions; the 2001 Judicial Honoree Award presented by the Bar Association of the District of Columbia, recognizing significant contributions in the field of law; and eleven honorary JD degrees. He is a member of the American Law Institute, the American Judicature Society, and the American Bar Foundation. Edwards serves as a teacher/mentor at the Unique Learning Center in Washington, D.C., a volunteer program established to assist disadvantaged innercity youth.

Married to Pamela Carrington-Edwards in 2000, Edwards has two children from a previous marriage to Ila Hayes Edwards.

Edwards begins his seminal article in the Michigan Law Review on legal education with a quotation from Felix Frankfurter, the former associate judge on the U.S. Supreme Court: “In the last analysis, the law is what the lawyers are,” but this could also aptly apply to Edwards’s professional career, for in the last analysis, the laws made by Edwards are what he is and what his life represents—a shining example of professionalism.

Edwards’s papers have not been archived. Personal profiles of Edwards can be found in the July 1996 editions of the American Lawyer and The Washington Legal Times.

—F. MICHAEL HIGGINBOTHAM

EIKERENKOETTER, FREDERICK J.

EIKERENKOETTER, FREDERICK J.See Reverend Ike.

ELAW, ZILPHA

ELAW, ZILPHA(c. 1790-?), evangelist and writer, was born near Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, to parents whose names remain unknown. In 1802, when Zilpha was twelve, her mother died during the birth of her twenty-second child, leaving Zilpha’s father to raise the three children who had survived infancy. Unable to support the family, her father sent her older brother to their grandparents’ farm far from Philadelphia and consigned Zilpha to a local Quaker couple, Pierson and Rebecca Mitchel. Within eighteen months Zilpha’s father died. Zilpha felt fortunate to stay with the Mitchels for the next six years, until she reached the age of eighteen.

Zilpha had enjoyed a close relationship with her father and was deeply grieved by his passing. The emotional turmoil associated with his death led her to a deeper contemplation of the state of her soul, though she felt that she had no religious instruction or direction to guide her through this period. Zilpha felt spiritually adrift between the public religious expressions she had witnessed as a young girl and the Quaker tradition where religious devotion was “performed in the secret silence of the mind” (Elaw, 54). Concerned about what she felt to be her increasingly impious behavior among the Mitchel children, Zilpha began to experience dreams and visions in which God or the archangel Gabriel warned her of her sinful ways and pressed her to repent before a promised cataclysmic end, when repentance would no longer be possible. When she was still a teenager, these dreams of damnation and her concerns about her feelings of guilt and sin led her to seek affiliation with the Methodists.

Conversion among the Methodists was a gradual process that Zilpha later compared to the dawning of the morning. That she marks her process in this way distinguishes her autobiography, Memoirs of the Life, Religious Experience, Ministerial Travels, and Labours of Mrs. Elaw, An American Female of Colour (1846), from many others in the spiritual autobiography genre, such as SOJOURNER TRUTH and JARENA LEE, in which the authors emphasize a single event or a miraculous series of distinctive incidents that worked an immediate and permanent change in the writer. Elaw, conversely, provides a model of slow but sure development over her adolescence and early adulthood.

In another vision Jesus appeared to Elaw as she wrote in her dairy and assured her that her sins had been forgiven. In 1808, at eighteen years of age, she “united [herself] in the fellowship of the saints with the militant church of Jesus on earth” (Elaw, 57), joining a local Methodist society. Conversion, study, church membership, baptism, and the new right to participate in Holy Communion transformed Zilpha’s life. She gained a new self-confidence that she had not possessed before her revelation. The society became her family, God became her father, and Jesus became her brother and friend.

The spiritual reverie she enjoyed changed when she married Joseph Elaw in 1810. Joseph was not a born-again Christian. Zilpha’s experience in this incompatible union served as the subject for one of the more powerful expositions in her narrative. She warns Christian women against marrying unbelieving men, suggesting that they would be more content to be drowned by a millstone hung about their necks for disobeying God’s law. Pride, arrogance, and the independence of young women drove them to make marital choices without parental regulation, guardianship, and government, she argued. In her view, women ought to be subordinate to fathers and, upon marriage, to husbands. The “carnal courtship” was not marriage but fornication, and it promised to deceive and destroy the woman’s spirit.

Elaw supported her opinion with scripture but, more convincingly, underpinned her discussion by describing the discord she suffered within her marriage. Joseph objected to Zilpha’s zealous and public religious practice and pressed her to take in amusements that he enjoyed, like music and dancing in nearby Philadelphia. Although the temptation to lose herself in these amusements was great, she held fast to her convictions.

In 1811 the Elaws relocated to Burlington, New Jersey, where their daughter was born and where Joseph could ply his trade as a fuller until embargos during the War of 1812 prevented shipping exports. Elaw also attended her first camp meeting in New Jersey. Camp meetings, referred to in the subtitle of her narrative, were open-air religious revivals, often attended by hundreds of worshipers who traveled great distances to participate. These events were popular among the Methodists and provided extraordinary opportunities for women and African Americans to engage in preaching and religious leadership outside the monitored and regulated site of the church.

As Elaw described the meetings, the campgrounds often had segregated living spaces but integrated worship spaces. Consequently, after experiencing another sanctifying vision, Elaw involuntarily began to pray and preach publicly and gained a reputation for her evangelical power. At one camp meeting, she developed the desire to engage in a household ministry among families in her community, and she was endorsed in this enterprise by local Burlington clergy. Elaw maintained this “special calling” despite a chilly reception by some local black Methodist parishioners and the vigorous protests of her husband, who feared that she would be ridiculed.

Throughout her period of household ministry, Elaw struggled with a call to preach to a broader audience, with her divine mission at odds with her sense of feminine propriety. She continued to have dreams about a greater call, but she found little support for this vision as well. All thought of preaching ended for a time when her husband died on 27 January 1823. To support herself and her daughter, Elaw established a school, but closed it two years later, yielding to the call to preach. She placed her daughter with relatives and began to preach, for a while joining with Jarena Lee. Elaw’s itinerant ministry took her through the mid-Atlantic and northeastern United States and even below the Mason-Dixon line in 1828 to Maryland and Virginia, preaching to blacks and whites, men and women, believers and nonbelievers. She remarked that she became a “prodigy” to those who heard and saw her. The confluence of her race, gender, and spiritual enthusiasm presented a singular spectacle to many whose fascination with her rendered them susceptible to her persuasive style and rhetoric.

In 1840 Elaw sailed to London, England, to preach and evangelize. She met with success there, but she continued to battle those who were not receptive to women preachers. Her narrative suggests that she intended to return to America in 1845, but no record of her return or activity in the United States exists after the publication of her narrative in 1846.

A notable feature of Elaw’s narrative is the regularity with which she attributes her success to the combination of her race, gender, and salvation. Her narrative is modeled after Saint Paul’s struggles and salvation, as detailed in his letters to the Christian churches in the New Testament. Taken as a whole, Elaw’s narrative characterizes her race and gender as socially constructed “thorns” or burdens that, like Paul, she must endure. These “burdens” were the elements that rendered her a prodigy, or phenomenon to those who heard her preach. The confluence of her race, gender, and spiritual power were, in her understanding, elements of grace with which she had been blessed to do God’s work.

Like many women active in preaching activities in the nineteenth century, Elaw traveled, spoke in an impassioned and inspired manner on the Bible, and wrote a narrative of her religious development as a guide to others, especially women, who might follow her path. She did not carry any official designation as a minister or preacher, but was recognized for her powerful and effective evangelism as an itinerant religious leader. As one of the earliest black women to claim the right to preach publicly, Elaw was a key figure in establishing the tradition of African American women religious leaders. This tradition continued throughout the nineteenth century in the work of such notable evangelists as JULIA FOOTE and AMANDA SMITH, and it laid the groundwork for the acceptance of such women as PAULI MURRAY and Bishop BARBARA HARRIS in ministerial roles in the late twentieth century.

Elaw, Zilpha. Memoirs of the Life, Religious Experience, Ministerial Travels, and Labours of Mrs. Elaw, An American Female of Colour; Together with Some Account of the Great Religious Revivals in America (1846).

Andrews, William L., ed. Sisters of the Spirit: Three Black Women’s Autobiographies of the Nineteenth Century (1986).

—MARTHA L. WHARTON

ELDERS, M. JOYCELYN

ELDERS, M. JOYCELYN(13 Aug. 1933–), physician, scientist, professor, public health official, and first African American surgeon general of the United States, was born Minnie Lee Jones in the small town of Schaal, Arkansas, the oldest of eight children of Curtis Jones, a sharecropper, and Haller Reed Jones. As a child, Jones performed the hard labor demanded of Arkansas farmers and their families, and she often led her younger siblings in their work on the small cotton farm. The family home was an unpainted three-room shack with no indoor plumbing or electricity, and there was no hospital or physician for miles around. Jones watched her mother give birth seven times without medical assistance; the only memory she has of a visit to a physician was when her father took a gravely ill younger brother twelve miles by mule to the nearest doctor.

Haller Jones was determined that her children would have more prosperous futures and instilled the importance of education in all of her children, sending them to school during the winter and constantly drilling them on reading skills during the summer months. Minnie Jones excelled at the small segregated Howard County Training School in Schaal, graduating as valedictorian at the age of fifteen. At the graduation ceremony a representative from the Philander Smith Methodist College in Little Rock awarded her a full scholarship. She almost was unable to accept, as transportation to Little Rock was too expensive and she was too valuable as a work leader in the fields. But the family managed with help from extended family and neighbors, and Jones began her college career in the fall of 1948.

At Philander Smith, Jones decided to pursue a career in science, hoping to work in a laboratory after college. Then, at an event arranged by her sorority, Delta Sigma Theta, she met Dr. Edith Irby Jones, the first African American medical student at the University of Arkansas. After hearing Edith Jones speak about her experiences there, she felt focused and inspired; Minnie Jones determined that she, too, would go to medical school and become a doctor. At about the same time, perhaps to demonstrate her newfound independence, she began to go by the name of Joycelyn, the middle name she had adopted during childhood.

Joycelyn Jones married a fellow student, Cornelius Reynolds, after graduation, and the couple moved to Milwaukee, Wisconsin, where Reynolds had secured employment. In Milwaukee, she worked as a nurse’s aide at the veterans’ hospital, where she learned of the Women’s Medical Specialist Corps. The WMSC was a program in which the army trained college graduates as physical therapists and made them commissioned officers eligible for the GI Bill. Jones and Reynolds parted amicably in May of 1953, and Jones remained in the army for three years. She left when she had served enough time to pay for medical school at what is now the University of Arkansas for Medical Sciences, where she was the second black woman student to attend, after Edith Irby Jones.

In 1960, the same year she graduated from medical school, Jones met and married Oliver Elders, a high school basketball coach. She then completed an internship in pediatrics at the University of Minnesota and returned to the University of Arkansas for a residency in pediatrics with an emphasis on pediatric surgery. Elders came through at the top of her class and was named chief resident in her third year. Along the way, she had two children: Eric in 1963 and Kevin in 1965. After her year as chief resident, Elders decided on a career in academic medicine, serving simultaneously as a junior faculty member and completing a master’s degree in Biochemistry. Elders ascended the professional ladder, achieving a full professorship and board certification in pediatric endocrinology in 1976. In all, Elders worked as a professor and practitioner of pediatric endocrinology for nearly twenty-five years and became especially renowned for authoring more than one hundred published papers and for her expert and compassionate treatment of young patients with diabetes, growth problems, and sexual disorders.

In 1987 Elders was appointed by then Arkansas Governor Bill Clinton to the position of director of the Arkansas Department of Health. She initially accepted with some misgivings about leaving her academic post, but she quickly became passionate about her new position. While in office, Elders and her team helped effect an impressive increase in the state health budget. They introduced a program to provide breast cancer screenings and provisions for funding around-the-clock in-home care for elderly and terminally ill patients, and they instituted programs to expand access to HIV testing and counseling services. Her policy initiatives for children resulted in a nearly 25 percent rise in immunizations and a tenfold increase in the number of early childhood screenings in the state. As director, Elders served on several presidential commissions on public health under President George H. W. Bush, and she was elected president of the Association of State and Territorial Health officers.

Elders was especially committed to lowering the teen pregnancy rate in Arkansas, at the time the second highest in the nation. In order to reduce the catastrophic public health consequences of such a high teen pregnancy rate, Elders and her team worked toward implementing a comprehensive health curriculum in the public schools, in which sex education would be a central topic. This would prove to be one of the most controversial acts of her administration, but Elders never backed down under pressure from her critics; she often commented that she felt she was in a unique position to help those in poor rural communities, having been raised in one, and that she would therefore not abandon the course she believed was right.

As director of the health department, Elders also worked toward establishing comprehensive health clinics in public schools. Because so many poor and rural communities in Arkansas lacked adequate health-care facilities, Elders and her staff reasoned that this would be the best way to expand access to preventive care measures, such as dental screenings and vaccinations. At the discretion of the local school board, these clinics could also be authorized to provide reproductive health counseling services and distribute condoms. Although the service was explicitly available only to students who had obtained their parents’ permission, it touched off a heated national debate over the relative merits and dangers of distributing condoms in public schools, and Elders’s policies became a regular target of critics nationwide.

In July 1993 Bill Clinton, by then president of the United States, appointed Elders to the position of surgeon general of the Public Health Services, and the U.S. Senate confirmed the appointment in September of the same year. Elders was the first African American and second woman appointed to this post, and, during her tenure, she served on a number of influential health policy committees and spoke widely on matters of public health. After only fifteen months as surgeon general, however, Elders was forced to resign over a public remark she had made at a United Nations World AIDS Day event. Following her presentation on school health clinics, a reporter asked her if she believed there should be any discussion of masturbation in high school health curricula. Elders responded, “I think it is part of human sexuality, and perhaps it should be taught.”

Two weeks later, amidst a barrage of press coverage, Elders tendered her resignation and moved back to Little Rock. She returned to her academic post at the University of Arkansas Children’s Hospital and a full schedule of public-speaking engagements, writing, and community and church involvement. Elders retired from her academic position in 1998, accepting an emeritus appointment. Since then she has lectured and published on those issues to which she has always been passionately dedicated: adequate health care for the poor, the importance of preventative health care, and the need for sex education in public schools.

Dr. M. Joycelyn Elders’s personal papers are held privately in a storage facility in Little Rock, Arkansas.

Elders, Joycelyn, and David Chanoff. Joycelyn Elders, M.D.: From Sharecropper’s Daughter to Surgeon General of the United States of America (1996).

—DEBORAH I. LEVINE

ELLINGTON, DUKE

ELLINGTON, DUKE(29 Apr. 1899–24 May 1974), jazz musician and composer, was born Edward Kennedy Ellington in Washington, D.C., the son of James Edward Ellington, a butler, waiter, and later printmaker, and Daisy Kennedy. The Ellingtons were middle-class people who struggled at times to make ends meet. Ellington’s mother was particularly attached to him; in her eyes he could do no wrong. They belonged to Washington’s black elite, who put much stock in racial pride. Ellington developed a strong sense of his own worth and a belief in his destiny, which at times shaded over into egocentricity. Because of this attitude, and his almost royal bearing, his schoolmates early named him “Duke.”

Ellington’s interest in music was slow to develop. He was given piano lessons as a boy but soon dropped them. He was finally awakened to music at about fourteen when he heard a pianist named Harvey Brooks, who was not much older than he. Brooks, he later said, “was swinging, and he had a tremendous left hand, and when I got home I had a real yearning to play.”

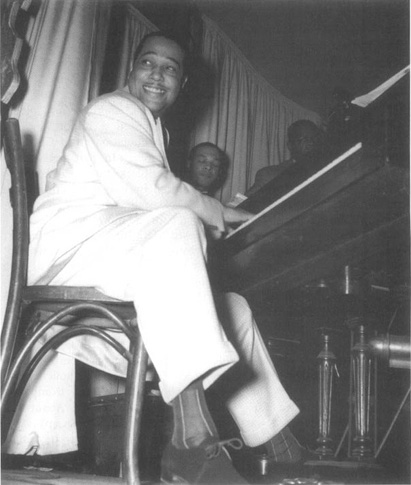

Duke Ellington photographed by GORDON PARKS SR. at the Hurricane Club in New York, 1943. Library of Congress

He did not take formal piano lessons, however, but picked the brains of local pianists, some of whom were excellent. He was always looking for shortcuts, ways of getting effects without much arduous practicing. As a consequence, it was a long time before he became proficient at the stride style basic to popular piano playing of the time.

As he improved, Ellington discovered that playing for his friends at parties was a route to popularity. He began to rehearse with some other youngsters, among them saxophonist Otto “Toby” Hardwick and trumpeter Arthur Whetsol. Eventually a New Jersey drummer, Sonny Greer, joined the group. By age sixteen or seventeen Ellington was playing occasional professional jobs with these and other young musicians. The music they played was not jazz, which still was not widely known, but rags and ordinary popular songs.

He was not yet committed to music. He was also studying commercial art, for which he showed an aptitude. However, he never graduated from high school, and in 1918 he married Edna Thompson; the following spring their son, Mercer, was born. Although later Ellington lived with several different women, he never divorced his wife.

He now had a family to support and was perforce drawn into the music business, one of the few areas in which blacks could earn good incomes and achieve a species of fame. Increasingly he was working with a group composed of Whetsol, Greer, and Hardwick under the nominal leadership of Baltimore banjoist Elmer Snowden. This was the nucleus of later Ellington bands. In 1923 the group ventured to New York and landed a job at a well-known Harlem cabaret, Barron’s Exclusive Club. The club had a clientele of intellectuals and the social elite, some of them white, and the band was not playing jazz, but “under conversation music.” Ellington was handsome and already a commanding figure, and the others were polite, middle-class youths. They were well liked, and in 1923 they were asked to open at the Hollywood, a new club in the Broadway theater district, soon renamed the Kentucky Club.

As blacks, they were expected to play the new hot music, now growing in popularity. Like many other young musicians, they were struggling to catch its elusive rhythms, and they reached out for a jazz specialist, trumpeter James “Bubber” Miley, who had developed a style based on the plunger mute work of a New Orleanian, “KING” OLIVER. Miley not only used the plunger for wahwah effects but also employed throat tones to produce a growl. He was a hot, driving player and set the style for the band. Somewhat later, SIDNEY BECHET, perhaps the finest improviser in jazz at the time, had a brief but influential stay with the band.

Through the next several years the band worked off and on at the Kentucky Club, recording with increasing frequency. Then, early in 1924, the group fired Snowden for withholding money, and Ellington was chosen to take over. Very quickly he began to mold the band to his tastes. He was aided by an association with Irving Mills, a song publisher and show business entrepreneur with gangland connections. Mills needed an orchestra to record his company’s songs; Ellington needed both connections and guidance through the show business maze. His contract with Mills gave Ellington control of the orchestra.

As a composer, Ellington showed a penchant for breaking rules: if he were told that a major seventh must rise to the tonic, he would devise a piece in which it descended. His still-developing method of composition was to bring to rehearsal—or even to the recording studio—scraps and pieces of musical ideas, which he would try in various ways until he got an effect he liked. Members of the band would offer suggestions, add counterlines, and work out harmonies among themselves. It was very much a cooperative effort, and frequently the music was never written down. Although in time Ellington worked more with pencil and paper, this improvisational system remained basic to his composing.

Beginning with a group of records made in November 1926, the group found its voice: the music from this session has the distinctive Ellington sound. The first important record was “East St. Louis Toodle-Oo” (1926), a smoky piece featuring Bubber Miley growling over a minor theme. Most important of all was “Black and Tan Fantasy” (1927), another slow piece featuring Miley in a minor key. It ends with a quotation from Chopin’s “Funeral March.” In part because of this touch, “Black and Tan Fantasy” was admired by influential critics such as R. D. Darrell, who saw it as a harbinger of a more sophisticated, composed jazz. Increasingly thereafter, Ellington was seen by critics writing in intellectual and music journals as a major American composer.

Then, in December 1927 the group was hired as the house band at the Cotton Club, rapidly becoming the country’s best-known cabaret. It was decided, for commercial purposes, to feature a “jungle sound,” built around the growling of Miley and trombonist Joe “Tricky Sam” Nanton. About this time Ellington added musicians who would fundamentally shape the band’s sound: clarinetist Barney Bigard, a well-trained New Orleanian with a liquid tone; saxophonist Johnny Hodges, who possessed a flowing, honeyed sound and quickly became the premier altoist in jazz; and Cootie Williams, who replaced the wayward Miley and soon became a master of the plunger mute. These and other instrumentalists each had a distinctive sound and gave Ellington a rich “tonal palette,” which he worked with increasing mastery.

Through the 1920s and 1930s Ellington created a group of masterpieces characterized by short, sparkling melodies, relentless contrasts of color and mood, and much more dissonant harmony than was usual in popular music. Among the best known of these are “Mood Indigo” (1930) and “Creole Love Call” (1927), two simple but very effective mood pieces; “Rockin’ in Rhythm” (1930), a driving up-tempo piece made up of sharply contrasting melodies; and “Daybreak Express” (1933), an uncanny imitation of train sounds. These pieces alone won Ellington a major position in jazz history, but they are only examples of scores of brilliant works.

By now he had come into his own as a songwriter. During the 1930s he created many standards, like “Prelude to a Kiss” (1938), “Sophisticated Lady” (1932), and “Solitude” (1934). This songwriting was critically important, for, leaving aside musical considerations, Ellington’s ASCAP royalties were in later years crucial in his keeping the band going.

It must be admitted, however, that Ellington borrowed extensively in producing these tunes. “Creole Love Call” and “Mood Indigo,” although credited to Ellington, were written by others. Various of his musicians contributed to “Sophisticated Lady,” “Black and Tan Fantasy,” and many more. Though it is not always easy to know how much others contributed to a given work, it was Ellington’s arranging and orchestrating of the melodies that lifted pieces like “Creole Love Call” above the mundane.

By 1931, through broadcasts from the Cotton Club and his recordings, Ellington had become a major figure in popular music. In that year the band left the club and for the remainder of its existence played the usual mix of one-nighters, theater dates, and longer stays in nightclubs and hotel ballrooms. Singer Ivie Anderson, who would work with the organization for more than a decade and remains the vocalist most closely associated with Ellington, joined him at this time.

In 1933 the band made a brief visit to London and the Continent. British critics convinced Ellington that he was more than just a dance-band leader. He had already written one longer, more “symphonic” piece, “Creole Rhapsody” (1931). He now set about writing more. The most important of these was “Black, Brown, and Beige,” which was given its premiere at Carnegie Hall in 1943. The opening was a significant event in American music: a black composer writing “serious” music using themes taken from black culture.

Classical critics did not much like the piece. The problem, as always with Ellington’s extended work, was that, lacking training, he was unable to unify the smaller themes and musical ideas he produced. Ellington, although temporarily discouraged, continued to write extended pieces, which combined jazz elements with devices meant to reflect classical music.

Additionally, beginning in 1936, Ellington recorded with small groups drawn from the band. These recordings, such as Johnny Hodges’s “Jeep’s Blues” (1938) and Rex Stewart’s “Subtle Slough,” contain a great deal of his finest work. Yet most critics would say that his finest work of the time was a series of concertos featuring various instrumentalists, including “Echoes of Harlem” (1935) for Cootie Williams and “Clarinet Lament” (1936) for Barney Bigard.

In 1939 the character of the band began to change when bassist Jimmy Blanton, who was enormously influential during a career cut short by death, and tenor saxophonist Ben Webster were added. Ellington had never had a major tenor soloist at his disposal, and Webster’s rich, guttural utterances were a new voice for him to work with. Also arriving in 1939 was Billy Strayhorn, a young composer who had more formal training than Ellington. Until Strayhorn’s death in 1967, a substantial part of the Ellington oeuvre was actually written in collaboration with Strayhorn, although it is difficult to tease apart their individual contributions. In 1940 Ellington switched from Columbia to Victor. The so-called Victor band of 1940 to 1942, when a union dispute temporarily ended recording in the United States, is considered by many jazz critics to be one of the great moments in jazz. “Take the ‘A’ Train,” written by Strayhorn, is a simple, indeed basic, piece, which gets its effect from contrapuntal lines and the interplay of the band’s voices. “Cotton Tail” (1940) is a reworking of “I’ve Got Rhythm” that outshines the original melody and is famous for a powerful Webster solo and a sinuous, winding chorus for the saxophones. “Harlem Air Shaft” (1940) is a classic Ellington program piece meant to suggest the life in a Harlem apartment building and is filled with shifts and contrasts that produce a sense of rich disorder. “Main Stem” (1942) is another hard-driving piece, offering incredible musical variety within a tiny space. Perhaps the most highly regarded recording from this period is “Ko-Ko” (1940). Originally written as part of an extended work, it is based on a blues in E-flat minor and is built up of the layering of increasingly dissonant and contrasting lines.

By the late 1940s, it was felt by many jazz writers that the band had deteriorated. The swing band movement, which had swept up the Ellington group in the mid-1930s, had collapsed, and musical tastes were changing. A number of the old hands left, taking with them much of Ellington’s tonal palette, and while excellent newcomers replaced them, few equaled the originals. Through the late 1940s and into the 1950s there were constant changes of personnel, shifts from one record company to the next, and a dwindling demand for the orchestra. Henceforth Ellington would need his song royalties to support what was now a very expensive organization. In 1956 Ellington was asked to play the closing Saturday night concert at the recently established Newport Jazz Festival. At one point in the evening he brought tenor saxophonist Paul Gonsalves forward to play twenty-seven choruses of the blues over a rhythm section. The crowd was wildly enthusiastic; the event got much media attention, and Ellington’s star began to rise again.

Through the late 1950s and 1960s Ellington continued to create memorable pieces, many of them contributed by Strayhorn, particularly the haunting “Blood Count” (1967). Also of value were a series of collaborations with Ellington by major jazz soloists from outside the band, including LOUIS ARMSTRONG, Coleman Hawkins, and JOHN COLTRANE. Other fine works were Strayhorn’s “UMMG,” featuring DIZZY GILLESPIE; “Paris Blues” (1960), a variation on the blues done for a movie by that name; and an album tribute to Strayhorn issued as “. . . And His Mother Called Him Bill” (1967).

But by this time Ellington’s main concerns were his extended works, which eventually totaled some three dozen. Many of these were dashed off to meet deadlines, or even pulled together in rehearsal, and are of slight value. Almost all suffer from the besetting flaw in Ellington’s longer works, his inability to make unified wholes of what are often brilliant smaller pieces.

Although some critics today insist that much of this work is of value, it was not well reviewed outside the jazz press when it appeared. Among the most successful are “The Deep South Suite” (1946), “Harlem (A Tone Parallel to Harlem),” first recorded in 1951, and “The Far East Suite” in collaboration with Strayhorn and recorded in 1966.

To Ellington, the most important of these works were the three “Sacred Concerts,” created in the last years of his life. They consist of collections of vocal and instrumental pieces of various sorts, usually tied loosely together by a religious theme. Although these works contain fine moments and have their admirers, they do not, on the whole, succeed. Duke Ellington’s legacy is the short jazz works, most of them written between 1926 and 1942: the jungle pieces, like “Black and Tan Fantasy”; the concertos, like “Echoes of Harlem”; the mood pieces, such as “Mood Indigo”; the harmonically complex works, like “Ko-Ko”; and the hard swingers, such as “Cotton Tail.” This work has a rich tonal palette. It uses carefully chosen sounds by his soloists; endless contrast not only of sound but of mood, mode, key; the use of forms unusual in popular music, like the four-plus-ten bar segment in “Echoes of Harlem”; and deftly handled dissonance, often built around very close internal harmonies. Although Ellington was not a jazz improviser in a class with Armstrong or CHARLIE PARKER, his body of work is far larger than theirs, more varied and richer, and is second to none in jazz. Ellington died in New York City.

Many Ellington papers and artifacts are housed in the Duke Ellington Collection, National Museum of American History, Smithsonian Institution. Additional materials are lodged in the Duke Ellington Oral History Project at Yale, the Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture of the New York Public Library, and the Institute for Jazz Studies at Rutgers University.

Ellington, Edward Kennedy. Music Is My Mistress (1973).

Collier, James Lincoln. Duke Ellington (1987). Dance, Stanley. The World of Duke Ellington (1970).

Ellington, Mercer, with Stanley Dance. Duke Ellington in Person (1978).

Jewell, Derek. Duke: A Portrait of Duke Ellington (1977).

Ulanov, Barry. Duke Ellington (1946).

Aasland, Benny. The “Wax Works” of Duke Ellington (1979–).

Bakker, Dick M. Duke Ellington on Microgroove (1972–).

Massagli, Luciano, Liborio Pusateri, and Giovanni M. Volonté, Duke Ellington’s Story on Records (1967–).

—JAMES LINCOLN COLLIER

ELLIOTT, ROBERT BROWN

ELLIOTT, ROBERT BROWN(11 Aug. 1842–9 Aug. 1884), Reconstruction politician and U.S. Congressman, was born probably in Liverpool, England, of West Indian parents whose names are unknown. Elliott’s early life is shrouded in mystery, largely because of his own false claims, but apparently he did attend a private school in England (but not Eton as he claimed) and was trained as a typesetter. It is likely also that in 1866 or 1867, while on duty with the Royal Navy, he decided to seek his fortune in America and jumped ship in Boston Harbor, without, however, taking out citizenship papers. All that is known for certain is that by March 1867 Elliott was associate editor of the South Carolina Leader, a black-owned Republican newspaper in Charleston. Shortly thereafter he married Grace Lee Rollin, a member of a prominent South Carolina free Negro family. The couple had no children.

During Reconstruction South Carolina’s population was 60 percent black, and the state had many highly capable black leaders. Between 1867 and 1877, when state rule was formally restored, Elliott, a politically adept orator, developed into the major black spokesman and politician in South Carolina. He was one of the at least seventy-one black delegates to the 1868 Constitutional Convention, which drafted the most democratic constitution in South Carolina history. At the 1868 state Republican convention he was nominated for lieutenant governor but dropped out of contention after finishing third on the first ballot. That same year, while serving as the only black member of the five-man board of commissioners in Barnwell County, Elliott was elected to the South Carolina House of Representatives, where he became a very powerful player in state government. Almost elected as Speaker (placing second in the balloting), he was made chair of the committee on railroads and was appointed to the committee on privileges and elections, both very influential assignments. As assistant adjutant general of South Carolina, he even was placed in charge of organizing a militia. In 1870 Elliott was elected to the United States House of Representatives, defeating a white opponent in a district with only a slight black majority, and he was reelected by a wide margin two years later. Near the end of his second term he resigned in order to run again for the state house, winning easily. This time he did serve as Speaker from 1874 to 1876, when he was elected state attorney general. The next year, however, he was one of five Republicans removed from office following the Democratic takeover of Congress.

Elliott was even more influential within Republican Party ranks. A delegate to three national conventions (twice leading the delegation), he served as party chair in South Carolina for much of the 1870s and was permanent chair of most state nominating conventions.

In all of his political positions Elliott aligned himself with the Radical Republicans. At the state constitutional convention he led the successful opposition to both a literacy test for voters and a poll tax, as he well understood that they could later be used to keep blacks from voting. Also at the convention, he fought successfully to have invalidated all debts related to the sale of slaves. As a state representative, Elliott lobbied successfully for a bill to ban discrimination in public facilities and on public transportation. As a U.S. congressman, he gained some notoriety for a speech favoring federal suppression of the Ku Klux Klan and for his debate with former Confederate vice president Alexander Stephens over proposed legislation that subsequently became the Civil Rights Act of 1875. Also while in Congress he voted against the bill granting political amnesty to former Confederates. Elliott was nationally known by 1874, when black Bostonians asked him to give the oration at a memorial service for Radical senator Charles Sumner.

Despite Elliott’s well-deserved reputation as a racial militant, his record is not that simple. For example, as a delegate to the 1868 constitutional convention he supported the creation of a public school system and compulsory school attendance but opposed integration. Elliott never seriously interested himself in the plight of rural or urban black workers, and as president of a state labor convention in 1869 he favored a permanent halt to the confiscation of planter land. Even a few of his Democratic critics acknowledged that Elliott’s view of the role of the militia was more moderate than that of white governor Robert Scott, who saw it as an offensive and not a defensive force. In his speeches to black audiences, Elliott often expressed a belief in self-help as the means to political and economic empowerment.

Despite his moderate tendencies, Democrats insisted on seeing Elliott as an irresponsible hater of whites and as a troublemaker. White Carolinians, including some Republican enemies, categorized him as one of the state’s major “corruptionists,” a common and often unsubstantiated charge leveled against both black and white Radicals during Reconstruction. Although Elliott seems to have resisted small bribes and other minor enticements that some black and white politicians routinely accepted, his political career was not devoid of scandal. At least one financially lucrative deal made while he was on the state’s powerful railroad committee was suspect; as assistant adjutant general he charged excessive fees; in addition to Republican Party funds he took state monies for his various lobbying efforts; and he distributed large sums of public as well as private money during election campaigns. Thus, even though a succession of law partnerships failed, Elliott maintained a high lifestyle and owned numerous city lots as well as an elegant three-story house in Columbia. Comparatively, however, the corruption of white governors Franklin Moses Jr., Daniel Chamberlain, and Robert Scott and U.S. Senator John Patterson was far more blatant, and Elliott, unlike several of his black and white contemporaries, was never indicted for any crime.

Elliott’s reputation as a racial militant derived primarily from his successful efforts to increase black political participation, especially in terms of nominations to higher offices. In 1870, for example, as chair of the Republican nominating convention, Elliott made sure that black candidates were selected for three of the four congressional seats, that the candidate for lieutenant governor was black, and that overall blacks had greater influence in the party. These tactics angered white Republicans and Democrats alike, as did Elliott’s shifting of allegiances so that his political support became the determining factor in important elections—especially gubernatorial elections. Elliott was not politically invincible, however, nor was he always successful in achieving his own political goals. Perhaps his most devastating defeat occurred in the bitter, three-way fight for the Republican nomination for the U.S. Senate in 1872.

As state chair, Elliott was in charge of the 1876 campaign and, despite the Democrats’ widespread use of violence and intimidation, courageously spoke throughout the state. He hoped that his election as attorney general would prove to be a stepping-stone to the governorship, but the ouster of all Republican executive branch officeholders by the re-emergent Democrats in 1877 eliminated that possibility. Believing that the lack of Republican opposition would lead to dissension among Democrats, just as the absence of Democratic challengers had earlier produced divisions among Republicans, in both 1878 and 1880 Elliott, as chair, convinced party leaders not to run a statewide campaign. By 1880, however, Elliott had become greatly discouraged, and in 1881 he led a delegation of black protesters who met with President-elect James Garfield. Asserting that black southerners were “citizens in name and not in fact” and that their rights were being “illegally and wantonly subverted,” he appealed for federal help, which was not forthcoming.

Personal problems exacerbated Elliott’s dire political outlook. Financial losses forced him to close his law office in 1879. His monthly salary as special inspector of customs in Charleston (a patronage position) was not enough to keep him from having to sell his house in order to pay off his debts. Continuing bouts with malaria and his wife’s medical problems made his life even more difficult. A delegate to the Republican National Convention in 1880, Elliott was frustrated further by the defeat of his presidential choice, Secretary of the Treasury John Sherman. After eleven months in New Orleans as special agent of the Treasury, Elliott was fired for criticizing his boss and for supporting a losing political faction. A final law firm failed, and his health worsened. He died penniless in New Orleans of malarial fever.

Elliott was a charismatic and effective political leader who provoked outrage among whites and enthusiasm among blacks. What most outraged his opponents was Elliott’s racial pride and his insistence on demanding, not asking, for his rights and the rights of black Americans. Persistently calling for the unprecedented expansion of national power in order to guarantee the fruits of Reconstruction while also urging blacks to be more worthy of the freedom they had won, Elliott was a precursor of many twentieth-century black leaders. Yet despite his reputation for political militancy, Elliott was always an ardent party man who believed that a strong Republican Party and Union constituted the best hope for racial equality.

Elliott’s most important letters can be found in the South Carolina Governors Papers of Franklin Moses Jr., Robert Scott, and Daniel Chamberlain, South Carolina Department of Archives, and in the John Sherman Papers, Library of Congress.

Hine, William C. “Black Politicians in Reconstruction Charleston, South Carolina: A Collective Study,” Journal of Southern History 49 (1983), 555–84.

Holt, Thomas C. Black over White: Negro Political Leadership in South Carolina during Reconstruction (1977).

Lamson, Peggy. The Glorious Failure: Black Congressman Robert Brown Elliott and Reconstruction in South Carolina (1973).

Rabinowitz, Howard N. Race, Ethnicity, and Urbanization: Selected Essays (1994).

—HOWARD N. RABINOWITZ

ELLISON, RALPH WALDO

ELLISON, RALPH WALDO(1 Mar. 1913?–16 Apr. 1994), novelist and essayist, was born in Oklahoma City, Oklahoma, the oldest of two sons of Lewis Ellison, a former soldier who sold coal and ice to homes and businesses, and Ida Milsaps Ellison. (Starting around 1940 Ellison gave his year of birth as 1914; however, the evidence is strong that he was born in 1913.) His life changed for the worse with his father’s untimely death in 1916, an event that left the family poor. In fact, young Ralph would live in two worlds. He experienced poverty at home with his brother, Herbert (who had been just six weeks old when Lewis died), and his mother, who worked mainly as a maid. At the same time, he had an intimate association with the powerful, wealthy black family in one of whose houses he had been born.

At the Frederick Douglass School in Oklahoma City he was a fair student, but he shone as a musician after he learned to play the trumpet. Graduating from Frederick Douglass High School in 1932, he worked as a janitor before entering Tuskegee Institute in Alabama in 1933. There his core academic interest was music, and his major ambition was to be a classical composer—although he was also fond of jazz and the blues. In Oklahoma City, which was second only to Kansas City as a hotbed of jazz west of Chicago, he had heard several fine musicians, including Lester Young, Oran “Hot Lips” Page, COUNT BASIE, and Louis ARMSTRONG. The revolutionary jazz guitarist Charlie Christian and the famed blues singer Jimmy Rushing both grew up in Ellison’s Oklahoma City. However, classical music was emphasized at school. At Tuskegee, studying under William Levi Dawson and other skilled musicians, Ellison became student leader of the school orchestra. Nevertheless, he found himself attracted increasingly to literature, especially after reading modern British novels and, even more influentially, T. S. Eliot’s landmark modernist poem, The Waste Land.

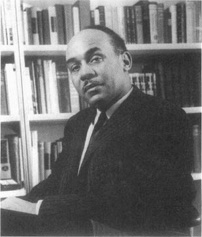

Ralph Ellison published Invisible Man in 1952 and won the prestigious National Book Award the next year. Archival Research International/Double Delta Industries Inc.

In 1936, after his junior year, Ellison traveled to New York City hoping to earn enough money as a waiter to pay for his senior year. Ellison never returned to Tuskegee as a student. Settling in Manhattan, he dropped his plan to become a composer and briefly studied sculpture. Working as an office receptionist and then in a paint factory, he also found himself inspired, in the midst of the Great Depression, by radical socialist politics and communism itself. He became a friend of LANGSTON HUGHES, who later introduced him to RICHARD WRIGHT, then relatively unknown. Encouraged by Wright, whose modernist poetry he admired, Ellison continued to read intensively in modern literature, literary and cultural theory, philosophy, and art. His favorite writers were Herman Melville and Fyodor Dostoyevsky from the nineteenth century and, in his own time, Eliot, Ernest Hemingway, and André Malraux (the French radical author of the novels Man’s Fate and Man’s Hope). These men, joined by the philosopher and writer Kenneth Burke as well as Mark Twain and William Faulkner, became Ellison’s literary pantheon. (Ellison never expressed deep admiration for any black writer except—for a while—Wright. He liked and was indebted to Langston Hughes personally but soon dismissed his work as shallow.)

In 1937, as editor of the radical magazine New Challenge, Wright surprised Ellison with a request for a book review. The result was Ellison’s first published essay. Next, Wright asked Ellison to try his hand at a short story. The story, “Hymie’s Bull,” was not published in Ellison’s lifetime, but he was on his way as an author. A trying fall and winter (1937–1938) in Dayton, Ohio, following the death of his mother in nearby Cincinnati, only toughened Ellison’s determination to write. In 1938 he secured a coveted place (through Wright) on the Federal Writers’ Project in New York, where he conducted research into and wrote about black New York history over the next four years. That year he married the black actress and singer (and communist) Rose Poindexter.

Slowly Ellison became known in radical literary circles with reviews and essays in magazines such as New Masses, the main leftist literary outlet. When he became managing editor (1942–1943) of a new radical magazine, Negro Quarterly, the lofty intellectual and yet radical tone he helped to set brought him more favorable attention. About this time Ellison came to a fateful decision. He later identified 1942 as the year he turned away from an aesthetic based on radical socialism and the need for political propaganda to one committed to individualism, the tradition of Western literature, and the absolute freedom of the artist to interpret and represent reality.

Facing induction during World War II into the segregated armed forces, Ellison enlisted instead in the Merchant Marine. This led to wartime visits to Swansea in Wales, to London, and to Rouen, France. During the war he also published several short stories. His most ambitious, “Flying Home” (1944), skillfully combines realism, surrealism, folklore, and implicit political protest. Clearly Ellison was now ready to create fiction on a larger scale. By this time his marriage had fallen apart. He and Rose Poindexter were divorced in 1945. The next year he married Fanny McConnell, a black graduate in drama of the University of Iowa who was then an employee of the National Urban League in Manhattan.

With a Rosenwald Foundation Fellowship (1945–1946) Ellison began work on the novel that would become Invisible Man. (One day, on vacation in Vermont, he found himself thinking: “I am an invisible man.” Ellison thus had the first line, and the core conceit, of his novel.) In 1947 he published the first chapter—to great praise—in the British magazine Horizon. In the following five years Ellison published little more. Instead, he labored to perfect his novel, whose anonymous hero, living bizarrely in an abandoned basement on the edge of Harlem, relates the amazing adventure of his life from his youthful innocence in the South to disillusionment in the North (although his epilogue suggests a growing optimism).

In April 1952 Random House published Invisible Man. Many critics hailed it as a remarkable literary debut. However, black communist reviewers excoriated Ellison, mainly because Ellison had obviously modeled the ruthless, totalitarian, and ultimately racist “Brotherhood” of his novel on the Communist Party of the United States. Less angrily, some black reviewers also stressed the caustic depiction of black culture in several places in Invisible Man. Selling well for a first novel, the book made the lower rungs of the best-seller list for a few weeks. Then, in January 1953, Invisible Man won for Ellison the prestigious National Book Award in fiction. This award transformed Ellison’s life and career. Suddenly black colleges and universities, and even a few liberal white institutions, began to invite him to speak and teach. That year he lectured at Harvard and, the following year, taught for a month in Austria at the elite Salzburg Seminar in American Studies.

In 1955 he won the Prix de Rome fellowship to the American Academy in Rome. There he and his wife lived for two years (1955–1957) in a community of classicists, archeologists, architects, painters, musicians, sculptors, and other writers. While in Rome, Ellison worked hard on an ambitious new novel about a light-skinned black boy who eventually passes for white and becomes a notoriously racist U.S. senator, and the black minister who had reared the boy as his beloved son. He worked on this novel for the rest of his life.