HALEY, ALEX

HALEY, ALEX HALEY, ALEX

HALEY, ALEX(11 Aug. 1921–10 Feb. 1992), writer, was born Alexander Palmer Haley in Ithaca, New York, the son of Simon Alexander Haley, a graduate student in agriculture at Cornell University, and Bertha George Palmer, a music student at the Ithaca Conservatory of Music. Young Alex Haley grew up in the family home in Henning, Tennessee, where his grandfather Will Palmer owned a lumber business. When the business was sold in 1929, Simon Haley moved his family to southern black college communities, including Alabama Agricultural and Mechanical College in Normal (near Huntsville), Alabama, where he had his longest tenure teaching agriculture. The three sons of Bertha and Simon Haley, Alex, George, and Julius, spent their summers in Henning, where, in the mid-1930s, grandmother Cynthia Murray Palmer recounted for her grandsons the stories of their family’s history.

After graduating from high school in Normal, Alex Haley studied to become a teacher at Elizabeth City State Teachers College in North Carolina from 1937 to 1939. In 1939 he enlisted in the U.S. Coast Guard. Two years later Haley married Nannie Branch. They had two children. Haley spent twenty years in the coast guard, advancing from mess boy to ship’s cook on a munitions ship, the USS Murzin, in the South Pacific during World War II. To relieve his boredom, he began writing, love letters for fellow shipmates at first, then romance fiction, which brought many rejection letters from periodicals such as True Confessions and Modern Romances. Finally, Haley sold three stories on the history of the coast guard to Coronet. In 1949 the coast guard created the position of chief journalist for him. Haley did public relations, wrote speeches, and worked with the press on rescue stories for the coast guard until he retired in 1959.

Failing to find other work and sustained by his military pension, Haley moved to Greenwich Village to work as a freelance writer in 1959. Casting about for his subject and voice, his early articles included a feature on Phyllis Diller for the Saturday Evening Post. Two articles for Reader’s Digest were better indicators of Haley’s future work. One was a feature on Nation of Islam leader ELIJAH MUHAMMAD; the other was an article about his brother George, who was the first African American student at the University of Arkansas law school in 1949 and would be elected to the Kansas state legislature in the 1960s. In 1962 Playboy hired Haley to produce a series of interviews with prominent African Americans: MILES DAVIS, Cassius Clay (MUHAMMAD ALI), JIM BROWN, SAMMY DAVIS JR., QUINCY JONES, LEONTYNE PRICE, and MALCOLM X. The last interview was the genesis of Haley’s first important book, The Autobiography of Malcolm X (1965). Based on extensive interviews with the religious leader, the book was Haley’s artistic creation and has won an important place in American biography. (Haley’s manuscript of The Autobiography of Malcolm X is in private hands, but the publisher’s copy is in the Grove Press Archive at Syracuse University.) His marriage to his first wife ended in 1964; that same year Haley married Juliette Collins. They had one child before their divorce in 1972.

Haley’s second important book was even more his own story than The Autobiography. Recalling stories recounted to him by his grandmother twenty-five years earlier, Haley had begun research on his family’s history as early as 1961. Backed by a contract from Doubleday, Haley began serious work on a book that was initially to be called Before This Anger. His research trips across the South took him to Gambia, West Africa, where a griot identified an ancestor as Kunte Kinte. In 1972 Haley founded and became the president of the Kinte Foundation of Washington, D.C., which sought to encourage research in African American history and genealogy. Roots: The Saga of an American Family (1976) finally appeared in the bicentennial year to great fanfare. A historical novel that invited acceptance as a work of history, it told the story of the family’s origins in West Africa, its experience in slavery, and its subsequent history. A best-selling book that won a Pulitzer Prize, Roots had even greater impact when it was made into a gripping television miniseries. Broadcast by ABC in January and February 1977, it was seen, in whole or in part, by 130 million people. It stimulated interest and pride in the African American experience and had a much greater immediate impact than did The Autobiography.

In 1977, however, Margaret Walker brought suit against Haley for plagiarism from her novel Jubilee. Her case was dismissed. Subsequently, however, Haley reached an out-of-court settlement for $650,000 with novelist Harold Courlander, who alleged that passages in Roots were taken from his The Slave. Haley acknowledged that Roots was a combination of fact and fiction. By 1981 professional historians were challenging the genealogical and historical reliability of the book. A third lawsuit for plagiarism was filed in 1989 by Emma Lee Davis Paul. The symbolic significance of the linkage in Roots of the African American experience to its African origins for a mass audience continues to be important. Yet, by the time of Haley’s death, renewed interest in Malcolm X and questions about the originality and reliability of Roots seemed to have reversed early judgments about the relative importance of the two books.

In 1988 Haley published A Different Kind of Christmas, a historical novella about the Underground Railroad. When he died in Seattle, Washington, Haley was separated from his third wife, Myra Lewis, and there were legal claims of more than $1.5 million against his estate. The primary claimants were First Tennessee Bank, his first and third wives, and many creditors, including a longtime researcher, George Sims. The bank held a mortgage of almost one million dollars on Haley’s 127-acre farm near Norris, Tennessee. His first wife claimed that their 1964 divorce was not valid, and his third wife claimed entitlement to one-third of the estate. The executor of Haley’s estate was his brother George, who had been chief counsel to the U.S. Information Agency and chaired the U.S. Postal Rate Commission. George Haley concluded that the estate must be sold. In a dramatic sale on 1–3 October 1992, Alex Haley’s estate, including his manuscripts, was auctioned to the highest bidder.

His novel Queen: The Story of an American Family, based on the life of his paternal grandmother, was published posthumously in 1993 and was the basis of a television miniseries that aired in February 1994. A second novel, Henning, which was named for the small community in West Tennessee where Haley lived as a child and is buried, remains unpublished.

Haley’s early interviews for Playboy, research files on Malcolm X, and forty-nine volumes of Roots in various languages are at the Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture of the New York Public Library. Manuscript and research material for Roots are at the University of Tennessee, Knoxville.

Haley, Alex. “Roots: A Black American’s Search for His Ancestral African.” Ebony, Aug. 1976, 100–102, 104, 106–107.

Bain Robert, ed. Southern Writers: A Biographical Dictionary (1979).

Nobile, Philip. “Uncovering Roots.” Village Voice, 23 Feb. 1993, 31–38.

Taylor, Helen. ‘“The Griot from Tennessee’: The Saga of Alex Haley’s Roots.” Critical Quarterly 37 (Summer 1995): 46–62.

Wolper, David L. The Inside Story of TV’s “Roots” (1978).

Obituary: New York Times, 11 Feb. 1992.

—RALPH E. LUKER

HALL, PRINCE

HALL, PRINCE(1735–4 Dec. 1807), Masonic organizer and abolitionist, was born in Bridgetown, Barbados, the son of a “white English leather worker” and a “free woman of African and French descent”; his birth date is variously given as 12 Sept. 1748 (Horton). He was the slave of William Hall, a leather dresser. At age seventeen, Hall found passage to Boston, Massachusetts, by working on a ship and became employed there as a leather worker. In 1762 he joined the Congregational Church on School Street. He received his manumission in 1770. Official records indicate that Hall was married three times. In 1763 he married Sarah Ritchie, a slave. In 1770, after her death, he married Flora Gibbs of Gloucester, Massachusetts; they had one son, Prince Africanus. In 1798 Hall married Sylvia Ward. The reason for the dissolution of the second marriage is unclear.

In March 1775 Hall was one of fifteen African Americans initiated into a British army lodge of Freemasons stationed in Boston. After the evacuation of the British, the black Masons were allowed to meet as a lodge and to participate fully in Masonic ceremonies, but full recognition was withheld. After a series of appeals, African Lodge No. 459 was granted full recognition in 1784 by the London Grand Lodge. Hall became the lodge’s “worshipful master,” charged with ensuring that it followed all the rules of the “Book of Constitution.” He served in that position until his death.

During the revolutionary war, Hall worked as a skilled craftsman and sold leather drumheads to the Continental army. Military records indicate that he most likely fought in the war. During the war, Hall also agitated on behalf of abolition. In 1777 he and seven other African Americans, including three black Masons, petitioned the General Court to abolish slavery in Massachusetts so that “the Inhabitanc of these Stats” could no longer be “chargeable with the inconsistency of acting themselves the part which they condem and oppose in others.” The petition was referred to the Congress of Confederation, but slavery was not abolished in Massachusetts until 1783.

Throughout the 1780s, Hall served as the grandmaster of the Masonic Lodge and owned and operated a leather workshop called the Golden Fleece. During that period he also emerged as a leading spokesman for black Bostonians. When Shays’s Rebellion broke out in western Massachusetts in 1786, Hall and the African lodge offered to raise a militia of seven hundred black soldiers to assist the government in putting down the rebellion. “We, by the Providence of God, are members of a fraternity that not only enjoins upon us to be peaceable subjects to the civil powers where we reside,” Hall wrote, “but it also forbids our having concern in any plot of conspiracies against the state where we dwell.” The offer was turned down by the governor.

In 1787 Hall and seventy-two other African Americans, perhaps resentful of the state government’s dismissive attitude toward them, signed a petition asking the state legislature to finance black emigration to Africa. “We, or our ancestors have been taken from all our dear connections, and brought from Africa and put into a state of slavery in this country,” the petition stated, in marked contrast to the patriotic language of the petition on Shays’s Rebellion. “We find ourselves, in many respects, in very disagreeable and disadvantageous circumstances; most of which must attend us, so long as we and our children live in America.” This was the first public statement in favor of African colonization made in the United States. The legislature accepted the petition but never acted on it.

Shortly after the emigration petition, Hall drafted another petition to the Massachusetts legislature, this one protesting the denial of free schools for African Americans who paid taxes and therefore had “the right to enjoy the privileges of free men.” In 1788 Hall drafted a petition, signed by twenty-two members of his lodge, expressing outrage at the abduction by slave traders of three free blacks in Boston. After a group of Quakers and other Boston clergy joined the call, in March 1788 the General Court passed an act that banned the slave trade and granted “relief of the families of such unhappy persons as may be kidnapped or decoyed away from this Commonwealth.” Diplomatic actions obtained the release of the three captured freemen from the French island of St. Bartholomew. Hall and the African lodge organized a celebration for their return to Boston.

In 1792 Hall delivered a lecture on the injustice of black taxpayers’ being denied free schools for their children. The lecture was published as A Charge Delivered to the Brethren of the African Lodge on the 25th of June, 1792 (1792). After failing to convince the state government to provide education for black children, Hall in 1796 established a school for black children in his own house. He recruited two students from Harvard College to serve as teachers. In 1806 the school’s increased enrollment prompted Hall to move it to a larger space at the African Society House on Belknap Street.

Hall died in Boston. The Prince Hall Masons, still the largest and most prestigious fraternal order of African Americans, was established one year after his death.

Hall was one of the most prominent and influential African Americans in the era of the American Revolution. As a leading spokesperson, organizer, and educator, Hall served as a principal agitator for abolition and for civil rights for black Americans in the period. He was also a pioneer in the establishment of fraternal organizations of African Americans at a time when such activities were deemed solely the province of whites.

Horton, James Oliver. “Generations of Protest: Black Families and Social Reform in Ante-Bellum Boston.” New England Quarterly 49, no. 2 (June 1976).

Kaplan, Sidney. The Black Presence in the Era of the American Revolution, 1770–1800 (1973).

Wesley, Charles H. Prince Hall, Life and Legacy (1977).

—THADDEUS RUSSELL

HAMER, FANNIE LOU TOWNSEND

HAMER, FANNIE LOU TOWNSEND(6 Oct. 1917–14 Mar. 1977), civil rights activist, was born in Montgomery County, Mississippi, the twentieth child of Lou Ella (maiden name unknown) and Jim Townsend, sharecroppers. When Fannie Lou was two, the family moved to Sunflower County, where they lived in abject poverty. Even when they were able to rent land and buy stock, a jealous white neighbor poisoned the animals, forcing the family back into share-cropping. Fannie Lou began picking cotton when she was six; she eventually was able to pick three to four hundred pounds a day, earning a penny a pound. Because of poverty she was forced to leave school at age twelve, barely able to read and write. She married Perry (“Pap”) Hamer in 1944. The couple adopted two daughters. For the next eighteen years Fannie Lou Hamer worked first as a sharecropper and then as a timekeeper on the plantation of B. D. Marlowe.

Hamer appeared destined for a routine life of poverty, but two events in the early 1960s led her to become a political activist. When she was hospitalized for the removal of a uterine tumor in 1961, the surgeons performed a hysterectomy without her consent. In August 1962, still angry and bitter over the surgery, she went to a meeting in her hometown of Ruleville to hear JAMES FORMAN of the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC) and James Bevel of the Southern Christian Leadership Conference (SCLC). After hearing their speeches on the importance of voting, she and seventeen others went to the courthouse in Indianola to try to register. They were told they could only enter the courthouse two at a time to be given the literacy test, which they all failed. On the trip back to Ruleville the group was stopped by the police and fined one hundred dollars for driving a bus that was the wrong color. Hamer subsequently became the group’s leader. B. D. Marlowe called on her that evening and told her she had to withdraw her application to register. Hamer refused and was ordered to leave the plantation. (Because Marlowe threatened to confiscate their belongings, Pap was compelled to work on the plantation until the harvest season was finished.) For a time, Hamer stayed with various friends and relatives, and segregationist night riders shot into some of the homes where she was staying. Nevertheless, she remained active in the civil rights movement, serving as a field secretary for SNCC, working for voter registration, advocating welfare programs, and teaching citizenship classes.

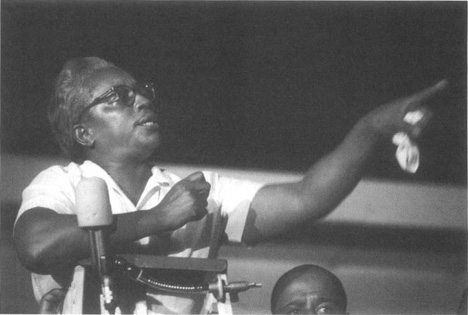

Fannie Lou Hamer speaking at a rally during the March Against Fear, 1966. © Flip Schulke/CORBIS

Hamer gained national attention when she appeared before the credentials committee of the 1964 Democratic National Convention in Atlantic City, New Jersey, on behalf of the Mississippi Freedom Democratic Party (MFDP), an organization attempting to unseat the state’s regular, all-white delegation. Speaking as a delegate and co-chair of the MFDP, she described atrocities inflicted on blacks seeking the right to vote and other civil rights, including the abuse she had suffered at the Montgomery County Jail, where white Mississippi law enforcement officers forced black inmates to beat her so badly that she had no feeling in her arms. (Hamer and several others had been arrested for attempting to integrate the “white only” section of the bus station in Winona, Mississippi, during the return trip from a voter registration training session in South Carolina.) After giving her dramatic testimony, she wept before the committee. Although her emotional appeal generated sympathy for the plight of blacks in Mississippi among the millions watching on television, the committee rejected the MFDP’s challenge.

That same year Hamer traveled to Ghana, Guinea, Nigeria, and several other African nations at the request and expense of those governments. Still, her primary interest was in helping the people of the Mississippi Delta. She lectured across the country, raising money and organizing. In 1965 she ran as an MFDP candidate for Congress, saying she was “sick and tired of being sick and tired.” While many civil rights leaders abandoned grassroots efforts, she remained committed to organizing what she called “everyday” people in her community, frequently saying she preferred to face problems at home rather than run from them. In 1969 she launched the Freedom Farm Cooperative to provide homes and food for deprived families, white as well as black, in Sunflower County. The cooperative eventually acquired 680 acres. She remained active, however, at the national level. In 1971 she was elected to the steering committee of the National Women’s political caucus, and the following year she supported the nomination of Sissy Farenthold as vice president in an address to the Democratic National Convention.

After a long battle with breast cancer, Hamer died at the all-black Mound Bayou Hospital, thirty miles from Ruleville. Civil rights leaders ANDREW YOUNG, JULIAN BOND, and ELEANOR HOLMES NORTON attended her funeral.

Hamer’s papers are in the Amistad Research Center at Tulane University, the Mississippi Department of Archives and History, and the Wisconsin State Historical Society. Other papers and speeches are in the Moses Moon Collection at the National Museum of American History of the Smithsonian Institution and the Civil Rights Documentation Project at the Moorland-Spingarn Research Center at Howard University.

Dittmer, John. Local People: The Struggle for Civil Rights in Mississippi (1995).

Lee, Chana Kai. For Freedom’s Sake: The Life of Fannie Lou Hamer (1999).

Mills, Kay. This Little Light of Mine: The Life of Fannie Lou Hamer (1993).

Payne, Charles M. I’ve Got the Light of Freedom: The Organizing Tradition and the Mississippi Freedom Struggle (1995).

Obituary: Washington Post, 17 and 19 Mar. 1977.

—MAMIE E. LOCKE

HAMMON, BRITON

HAMMON, BRITON(fl. 1747–1760), slave narrative author, wrote the earliest slave account published in North America. Practically nothing is known about him other than what he stated in the account of his life’s events between 1747 and 1760. While living as a slave in New England in 1747, Hammon undertook a sea voyage that turned out to be a thirteen-year odyssey featuring numerous perils and repeated captures by American Indians and Spaniards. A Narrative, of the Uncommon Sufferings, and Surprizing Deliverance of Briton Hammon, a Negro Man,—Servant to General Winslow, of Marshfield, in New-England, Who Returned to Boston, after Having Been Absent Almost Thirteen Years, published as a fourteen-page pamphlet, was printed and sold in 1760 by Green and Russell, a Boston publishing firm that was bringing out popular Indian captivity narratives.

This remarkable story of sea adventures, treachery, and multiple captivities is believed to be the first autobiographical slave narrative on record. It is not clear whether Hammon’s work was actually written by him. More than likely, it was dictated to a writer who faithfully transcribed the slave’s spoken tale. The ungrammatical and plain style of the text and the lack of much editorializing in the main body of the account seem to indicate that Briton Hammon’s words were written down almost exactly as he delivered them. However, the beginning and ending sections of the narrative do point to the probability that a white recorder stylistically embellished Hammon’s work with traditional eighteenth-century religious statements and personal expressions of humility.

Hammon’s journey commenced on the “25th Day of December, 1747,” when, with his master’s permission, the adventurous slave left Marshfield, Massachusetts, on a sea voyage. The next day he set sail from Plymouth on a ship bound for Jamaica and the “Bay” of Florida. After a month’s journey, the ship arrived in Jamaica for a short stay and then sailed up the coast of Florida for the purpose of picking up “log wood.” The vessel left Florida at the end of May, and in the middle of June it ran aground a short distance from shore, off “Cape-Florida.” There, the captain’s refusal to unload some of the cargo of wood so as to free the ship proved fatal. In two days’ time a large group of Indians in canoes, flying the English colors as a ruse to trick the captain and his crew, attacked and murdered everyone on the ship except Hammon, who saved himself by jumping overboard. But the Indians soon took him out of the water, beat him, and told him they were going to roast him alive. However, much to Hammon’s surprise, they treated him fairly well as their prisoner.

Hammon remained with the Indians for five weeks, until he managed to get to Cuba aboard a Spanish vessel whose captain he had previously met in Jamaica. The Indians pursued their escaped captive to Havana and demanded that he be returned to them. The governor of the island refused, but paid the Indians ten dollars to purchase Hammon. After working in the governor’s castle for about a year, Hammon met up with a press gang that demanded he serve aboard a ship sailing to Spain. Upon his refusal, Hammon was put into a dungeon and held there for four years and seven months, during which time he tried without success to make the governor aware of his imprisonment.

Finally, through the efforts of friends, Hammon’s situation came to the attention of the governor, who ordered him released and returned to his service. For the next several years Hammon worked for the governor in his castle and later for the bishop of Havana. During this time the long-suffering prisoner made three attempts to escape, and on the last one he succeeded. After a bit of difficulty he managed to be taken aboard an English ship that was about to sail for Jamaica and then on to London.

Upon his arrival in England, Hammon signed up for service on a succession of British naval vessels, one of which engaged in a battle with a French warship. During this encounter he “was Wounded in the Head by a small Shot.” After serving several months at sea, Hammon was discharged on 12 May 1759 to the Royal Hospital for Seamen at Greenwich, England, after “being disabled in the Arm.” Hammon soon recovered, and over the next few months he worked as a cook on several ships. After suffering a bout of fever in London, Hammon signed aboard a vessel sailing for Boston. On the passage over the Atlantic Ocean he became delighted to learn that his “good Master” General Winslow, who had allowed Hammon to leave New England thirteen years before, was one of the passengers aboard ship. After the happy reunion, Winslow remarked that Hammon “was like one arose from the Dead, for he thought I had been Dead a great many Years, having heard nothing of me for almost Thirteen Years” (Hammon, 13).

At the ending of Hammon’s narrative, he thanks the “Divine Goodness” for being “miraculously preserved and delivered out of many Dangers,” and attests the fact that he has “not deviated from Truth” (Hammon, 14). The ending corresponds to the spiritual declaration at the beginning of his narrative, and both sections seem to be tacked on by someone else to give the story a religious framework. These, in addition to the many religious references Hammon himself inserts in his story, impart a spiritual autobiographical character to the work. The title of Hammon’s book was similar to those of other published Indian captivity accounts, and at times his text seems to echo the phraseology and religious references of those accounts.

Hammon’s work is believed to be the first of thousands of slave narratives written in America. His story follows the pattern of spiritual striving and of escape from physical captivity (in Hammon’s case, Indian and Spanish bondage but not American slavery) that is an essential element of the many slave narratives that were published in the late eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries. In the immediate decades after Hammon’s publication, there appeared several notable slave narratives including those by JAMES ALBERT UKAWSAW GRONNIOSAW (1772), OLAUDAH EQUIANO (1789), and Venture Smith (1798). All that is known about Hammon’s life after his return to New England in 1760 is that his short tale of captivity and escape became a well-known personal account in eighteenth-century America.

Hammon, Briton. A Narrative, of the Uncommon Sufferings, and Surprizing Deliverance of Briton Hammon, a Negro Man,—Servant to General Winslow, of Marshfield, in New-England, Who Returned to Boston, after Having Been Absent Almost Thirteen Years (1760).

Andrews, William L. To Tell a Free Story: The First Century of Afro-American Autobiography, 1760–1865 (1986).

Costanzo, Angelo. Surprizing Narrative: Olaudah Equiano and the Beginnings of Black Autobiography (1987).

Foster, Frances Smith. Witnessing Slavery: The Development of Ante-bellum Slave Narratives (1979).

—ANGELO COSTANZO

HAMMON, JUPITER

HAMMON, JUPITER(11 Oct. 1711–?), poet and preacher, was born on the estate of Henry Lloyd on Long Island, New York, most probably the son of Lloyd’s slaves Rose and Opium, the latter renowned for his frequent escape attempts. Few records remain from Hammon’s early life, though correspondence of the Lloyd family indicates that in 1730 he suffered from a near-fatal case of gout. He was educated by Nehemiah Bull, a Harvard graduate, and Daniel Denton, a British missionary, on the Lloyd manor. Except for a brief period during the revolutionary war, when Joseph Lloyd removed the family to Hartford, Connecticut, Hammon lived his entire life on Long Island, in the Huntington area, serving the Lloyds as clerk and bookkeeper. There is no surviving indication that Hammon either married or had children. The precise date of his death and the location of his grave remain unknown, although it is known that he was alive in 1790 and had died by 1806.

Hammon is best known for his skill as a poet and preacher. Early in the spiritual Great Awakening of the 1730s and 1740s he was converted to a Wesleyan Christianity, and his poems and sermons reflect a Calvinist theology. Within the framework of these religious doctrines Hammon crafted a body of writing that critically investigates slavery. His first published poem, “An Evening Thought,” appeared as a broadside on Christmas Day 1760. Imbedded within the religious exhortation is a subtle apocalyptic critique of slavery in which the narrator prays that Christ will free all men from imprisonment:

Now is the Day, excepted Time;

The Day of Salvation;

Increase your Faith, do not repine:

Awake ye every Nation.

The poem ends by calling on Jesus to “Salvation give” and to bring equality to all: “Let us with Angels share.” Hammon couples a protest against earthly injustice with his religious conviction that all men are enslaved by sin.

Hammon’s next publication, “An Address to Miss Phillis Wheatley,” appeared in Hartford on 4 August 1778. The language of the poem offers PHILLIS WHEATLEY, then the most prominent African in America, spiritual—and thereby literary—advice. From the position of elder statesman Hammon attempts to correct what he sees as the pagan influences in Wheatley’s verse:

Thou hast left the heathen shore;

Thro’ mercy of the Lord,

Among the heathen live no more,

Come magnify thy God.

Psalm 34:1–3.

Typical of eighteenth-century American poetry, and primarily influenced by Michael Wigglesworth, Hammon’s verse portrays America as a site for spiritual salvation since it is free of the corruption of the Old World. The poem seizes on biblical passages in order to fashion an argument that he hopes will convince Wheatley to write more religious verse. Hammon’s next piece, An Essay on the Ten Virgins, advertised for sale in Hartford in 1779, is now lost.

Hammon exhorts his “brethren” to confess their sins and thus receive eternal salvation in his 1782 sermon Winter Piece. Its call to repentance and the proclamation of man’s inherent sinfulness is consistent with other sermons of this era. Another prose essay, An Evening’s Improvement, was printed in Hartford in 1783, and in it Hammon continues his protest against the institution of slavery. Published along with the sermon is Hammon’s greatest poem, “A Dialogue, Entitled, the Kind Master and the Dutiful Servant,” wherein he directly questions the unequal relationship between slave and master by emphasizing that before God, only sin divides Man:

Master

My Servant we must all appear,

And follow then our King;

For sure he’ll stand where sinners are,

To take true converts in.

Servant

Dear master, now if Jesus calls,

And sends his summons in;

We’ll follow saints and angels all,

And come unto our King.

The end of the poem disrupts the dialogue structure as the voice of the servant blends into that of the poet’s. In the last seven stanzas Hammon instructs all in how to attain peace and harmony:

Believe me now my Christian friends,

Believe your friend call’d Hammon:

You cannot to your God attend,

And serve the God of Mammon.

Here Hammon argues that materialism (Mammon), a code for economic slavery, prohibits salvation because it leads an individual away from religious contemplation.

Hammon’s final and most widely read piece, An Address to the Negroes in the State of New-York, was first printed in 1787 and then republished by the Pennsylvania Society for Promoting Abolition in 1806. In it Hammon speaks most directly against slavery. Within the body of his address Hammon argues that young African Americans should pursue their freedom even though he, at age seventy-six, does not want to be set free. Hammon calls for gradual emancipation: “Now I acknowledge that liberty is a great thing, and worth seeking for, if we can get it honestly; and by our good conduct prevail on our masters to set us free.”

Hammon argues that earthly freedom is subordinate to spiritual salvation and that the need to be born again in the spirit of Christ overpowers all else, for in death “there are but two places where all go . . . white and black, rich and poor; those places are Heaven and Hell.” Eternal judgment is what ultimately matters; thus Hammon urges his fellow African Americans, in their pursuit of freedom, to seek forgiveness through repentance and to place spiritual salvation above mortal concerns.

Hammon remained unknown from the early nineteenth century until 1915, when literary critic Oscar Wegelin, who rediscovered Hammon in 1904, published the first biographical information on him as well as some of his poetry. Although Hammon apparently was not the first African American writer (evidence suggests he was predated by one Lucy Terry poem), his canon makes him one of America’s first significant African American writers.

Blackshire-Belay, Carol Aisha, ed. Language and Literature in the African American Imagination (1992).

Inge, M. Thomas, et al., eds., Black American Writers, vol. 1 (1978).

O’Neale, Sondra A. Jupiter Hammon and the Biblical Beginnings of African American Literature (1993).

Ransom, Stanley Austin, Jr., ed. America’s First Negro Poet: The Complete Works of Jupiter Hammon of Long Island (1970).

Wegelin, Oscar. Jupiter Hammon: American Negro Poet (1915).

—DUNCAN F. FAHERTY

HANDY, W. C.

HANDY, W. C.(16 Nov. 1873–28 Mar. 1958), blues musician and composer, was born William Christopher Handy in Florence, Alabama, the son of Charles Bernard Handy, a minister, and Elizabeth Brewer. Handy was raised in an intellectual, middle-class atmosphere, as befitted a minister’s son. He studied music in public school, then attended the all-black Teachers’ Agricultural and Mechanical College in Huntsville. After graduation he worked as a teacher and, briefly, in an iron mill. A love of the cornet led to semiprofessional work as a musician, and by the early 1890s he was performing with a traveling minstrel troupe known as Mahara’s Minstrels; by middecade, he was promoted to bandleader of the group. Handy married Elizabeth Virginia Price in 1898. They had five children.

It was on one of the group’s tours, according to Handy, in the backwater Mississippi town of Clarksdale, that he first heard a traditional blues musician. His own training was limited to the light classics, marches, and early ragtime music of the day, but something about this performance, by guitarist CHARLEY PATTON, intrigued him. After a brief retirement from touring in 1900–1902 to return to teaching at his alma mater, Handy formed his first of many bands and went on the road once more. A second incident during an early band tour cemented Handy’s interest in blues-based music. In 1905, while playing at a local club, the Handy band was asked if they would be willing to take a break to allow a local string band to perform. This ragged group’s attempts at music making amused the more professional musicians in Handy’s band until they saw the stage flooded with change thrown spontaneously by audience members and realized that the amateurs would take home more money that night than they would. Handy began collecting folk blues and writing his own orchestrations of them.

By 1905 Handy had settled in Memphis, Tennessee. He was asked in 1907 by mayoral candidate E. H. “Boss” Crump to write a campaign song to mobilize the black electorate. The song, “Mr. Crump,” became a local hit and was published five years later under a new name, “The Memphis Blues.” It was followed two years later by his biggest hit, “The St. Louis Blues.” Both songs were actually ragtime-influenced vocal numbers with a number of sections and related to the traditional folk blues only in their use of “blue” notes (flatted thirds and sevenths) and the themes of their lyrics. Many of his verses were borrowed directly from the traditional “floating” verses long associated with folk blues, such as the opening words of “St. Louis Blues”: “I hate to see that evening sun go down.” In the mid-1920s early jazz vocalist BESSIE SMITH recorded “St. Louis Blues,” making it a national hit.

In 1917 Handy moved to New York, where he formed a new band, his own music-publishing operation, and a shortlived record label. He was an important popularizer of traditional blues songs, publishing the influential Blues: An Anthology in 1926 (which was reprinted and revised in 1949 and again after Handy’s death in 1972) and Collection of Negro Spirituals in 1939. Besides his work promoting the blues, he also was a champion of “Negro” composers and musicians, writing several books arguing that their musical skills equaled that of their white counterparts. In 1941 he published his autobiography, Father of the Blues, a not altogether reliable story of his early years as a musician.

By the late 1940s Handy’s eyesight and health were failing. In the 1950s he made one recording performing his blues songs, showing himself to be a rather limited vocalist by this time of his life, and one narrative recording with his daughter performing his songs. His first wife had died in 1937; he was married again in 1954, to Irma Louise Logan. He died in New York City. His autobiography was reissued after his death. In 1979 the W. C. Handy Blues Awards were established, to recognize excellence in blues recordings.

Handy may not have “fathered” the blues, as he claimed, nor did he write true “blues” songs of the type that were performed by country blues musicians. But he did write one of the most popular songs of the twentieth century, which introduced blues tonalities and themes to popular music. His influence on stage music and jazz was profound; “St. Louis Blues” remains one of the most frequently recorded of all jazz pieces.

Handy, W. C. Father of the Blues: An Autobiography (1941; repr. 1991).

Dickerson, James. Goin’ Back to Memphis: A Century of Blues, Rock ‘n’ Roll, and Glorious Soul (1996).

Southern, Eileen. The Music of Black Americans: A History (1971; repr. 1983).

—RICHARD CARLIN

HANSBERRY, LORRAINE VIVIAN

HANSBERRY, LORRAINE VIVIAN(19 May 1930–12 Jan. 1965), playwright, was born in Chicago, Illinois, the daughter of Carl Augustus Hansberry, a real estate agent, and Nannie Perry, a schoolteacher. Throughout her childhood, Lorraine Hansberry’s home was visited by many distinguished blacks, including PAUL ROBESON, DUKE ELLINGTON, and her uncle, the Africanist William Leo Hansberry, who helped inspire her enthusiasm for African history. In 1938, to challenge real-estate covenants against blacks, Hansberry’s father moved the family into a white neighborhood where a mob gathered and threw bricks, one of which nearly hit Lorraine. Two years later, after he won his case on the matter of covenants before the Supreme Court, they continued in practice. Embittered by U.S. racism, Carl Hansberry planned to relocate his family in Mexico in 1946 but died before the move.

After studying drama and stage design at the University of Wisconsin from 1948 to 1950, Hansberry went to New York and began writing for Robeson’s newspaper Freedom. She also marched on picket lines, made speeches on street corners, and helped move furniture back into evicted tenants’ apartments. In 1953 she married Robert Nemiroff, an aspiring writer and graduate student in English and history whom she had met on a picket line at New York University. Soon afterward, she quit full-time work at Freedom to concentrate on her writing, though she had to do part-time work at various jobs until the success of Nemiroff and Burt D’Lugoff’s song “Cindy, Oh Cindy” in 1956 freed her financially to write full-time. She also studied African history under W. E. B. DU BOIS at the Jefferson School for Social Science.

In 1957 Hansberry read a draft of A Raisin in the Sun to Philip Rose, a music publisher friend, who decided to produce it. Opening on Broadway in 1959, it earned the New York Drama Critic’s Circle Award for Best Play, making Hansberry the youngest American, first woman, and first black to win the award. This play about the Youngers, a black family with differing personalities and dreams who are united in racial pride and their fight against mutual poverty, has become a classic.

Although Hansberry enjoyed her new celebrity status, she used her many interviews to speak out about the oppression of African Americans and the social changes that she deemed essential. Her private life, however, remained painful and complex. Shortly after her marriage, her lesbianism emerged, leading to conflicts with her husband and within herself, difficulties exacerbated by the widespread homophobia that infected even the otherwise progressive social movements she supported. At some point amid her public triumph, she and Nemiroff separated, though their mutual interests and mutual respect later reunited them.

Lorraine Hansberry, whose play A Raisin in the Sun has become a classic of American drama. Library of Congress

In 1960 she wrote two screenplays of A Raisin in the Sun that would have creatively used the cinematic medium, but Columbia Pictures preferred a less controversial version that was closer to the original. Accepting a commission from NBC for a slavery drama to commemorate the Civil War centennial, Hansberry wrote The Drinking Gourd, but this too was rejected as controversial. During this busy year she began research for an opera titled Toussaint and a play about Mary Wollstonecraft; started writing her African play, Les Blancs; and began the play that evolved into The Sign in Sidney Brustein’s Window. In 1961 the film A Raisin in the Sun won a special award at the Cannes Film Festival.

In 1962 Hansberry wrote her postatomicwar play, What Use Are Flowers?, while publicly denouncing the House Un-American Activities Committee and the Cuban “missile crisis” and mobilizing support for the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC). The following year, she began suffering from cancer but continued her support for SNCC and, at JAMES BALDWIN’S invitation, participated in a discussion about the country’s racial crisis with Attorney General Robert Kennedy.

During 1964 she and Nemiroff divorced, but because of her illness they only told their closest friends and saw each other daily, continuing their creative collaboration until her death. She named Nemiroff her literary executor in her will. From April to October 1964 she was in and out of the hospital for therapy but managed to deliver her “To Be Young, Gifted and Black” speech to winners of the United Negro College Fund writing contest and to participate in the Town Hall debate on “The Black Revolution and the White Backlash.” In October she moved to a hotel near the site of rehearsals of The Sign in Sidney Brustein’s Window and attended its opening night. Despite its mixed reviews, actors and supporters from various backgrounds united to keep the play running until Hansberry’s death in New York City.

The Hansberry Archives, which include unpublished plays, screenplays, essays, letters, diaries, and two drafts of an uncompleted novel, are held at the Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture of the New York Public Library.

Carter, Steven R. Hansberry’s Drama: Commitment amid Complexity (1991).

Cheney, Anne. Lorraine Hansberry (1984).

Nemiroff, Robert. To Be Young, Gifted and Black: Lorraine Hansberry in Her Own Words (1969).

—STEVEN R. CARTER

HARPER, FRANCES ELLEN WATKINS

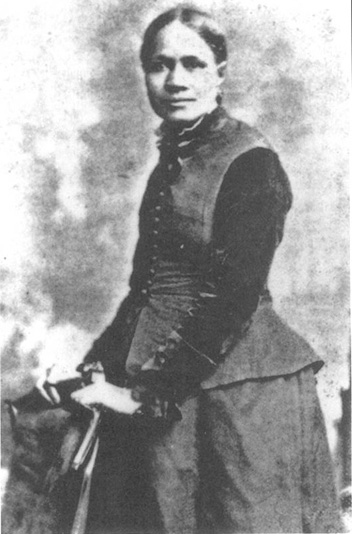

HARPER, FRANCES ELLEN WATKINS(24 Sept. 1825–20 Feb. 1911) poet, novelist, activist, and orator, was born Frances Ellen Watkins to free parents in Baltimore, Maryland. Her parents’ names remain unknown. Orphaned by the age of three, Watkins is believed to have been raised by her uncle, the Reverend William Watkins, a leader in the African Methodist Episcopal Church and a contributor to such abolitionist newspapers as Freedom’s Journal and the Liberator. Most important for Watkins, her uncle was also the founder of the William Watkins Academy for Negro Youth, where she studied. A well-known and highly regarded school, the academy’s curriculum included elocution, composition, Bible study, mathematics, and history. The school also emphasized social responsibility and political leadership. Although Watkins withdrew from formal schooling at the age of thirteen to begin work as a domestic servant, her studies at the academy no doubt shaped her political activism, oratorical skills, and creative writing.

After leaving school, Watkins worked as a seamstress and as a child caretaker for a family who owned a bookstore. While in their employ, she continued her studies independently, reading liberally from her employers’ book stock. Watkins’s first poetry appeared in local newspapers while she was still a teenager. In 1846, at the age of twenty-one, she published her first book, a collection of prose and poetry entitled Forest Leaves. No known copy of Forest Leaves has survived, though the scholar Frances Smith Foster has speculated that the volume probably contained poems and prose on subjects as varied as “religious values, women’s rights, social reform, biblical history and current events” (Foster, 8).

Frances Ellen Watkins Harper, poet and novelist, campaigned for equal rights throughout much of the nineteenth century. Schomburg Center

Although Watkins had the advantage of a better education than that of many of her peers, she was not immune to the racial hostilities of the antebellum years. The Compromise of 1850 complicated the lives of Watkins and her family. Among the many components of this federal legislation was the Fugitive Slave Act, which required that all citizens participate in the recovery of slaves and imposed severe penalties on those who refused. The family lived in the precarious position of being free blacks in Maryland, a slave state, at a time when federal legislation increasingly challenged black freedom. This undoubtedly shaped Watkins’s feelings that all blacks—slave and free, wealthy or poor—had a duty to the welfare of their fellow African Americans, a theme that emerges frequently in her literature.

In 1850 Watkins’s family was forced by local officials to disband their elite school for blacks and sell their home. Watkins moved to Ohio and began working as a teacher at the Union Seminary near Columbus. Why she chose to go to Ohio while some of her family members remained in Baltimore and others relocated to Canada is unknown. But in 1853 the state of Maryland forbade free blacks to enter the state. The penalty was enslavement. During this period in which Watkins was unable to return to her home state, a free black man was arrested and enslaved for entering Maryland. The man died soon after the ordeal. In a letter to WILLIAM STILL, Watkins cast this man’s death as the beginning of her own commitment to abolitionism: “Upon that grave I pledged myself to the Anti-Slavery cause” (Still, 786).

Soon after this incident in Maryland, Watkins moved to Philadelphia, where she lived in a home that functioned as an Underground Railroad station, one of a series of homes used to assist fugitive slaves in their escape. While there, she published several poems in response to Harriet Beecher Stowe’s Uncle Tom’s Cabin: “Eliza Harris,” “To Harriet Beecher Stowe,” and “Eva’s Farewell.” The poems appear to have been widely circulated. “Eliza Harris” appeared in at least three national papers. Building on the pathos of Stowe’s representation of the escape of the nearly white slave Eliza, Watkins makes the national implications of Eliza’s condition explicit:

Oh shall I speak of my proud

country’s shame?

Of the stains on her glory, how give them their name?

How say that her banner in mockery waves—

Her “star spangled banner”—o’er millions

of slaves?

(Foster, 61)

In 1854 Watkins initiated her career as a public speaker in New Bedford, Massachusetts, delivering a lecture entitled “The Education and the Elevation of the Colored Race.” Soon after, she was enlisted as a traveling lecturer for the Maine Antislavery Society and became an admired and much sought after lecturer. In a letter that same year, Watkins reports lecturing every night of the week, sometimes more than once in a day, to audiences as large as six hundred people. In a period of six weeks in the fall of 1854 she gave thirty-three lectures in twenty-one cities and towns. Contemporary newspaper accounts describe her as an eloquent and moving speaker. The Portland Advertiser, for example, characterized her lectures by saying that “the deep fervor of feeling and pathos that she manifests, together with the choice selection of language which she uses arm her elocution with almost superhuman force and power over her spellbound audience” (Boyd, 43). Also in 1854 Watkins published Poems on Miscellaneous Subjects, which included poems on antislavery and equal rights. It appears that the publisher was confident that the book would be well received. Y. B. Yerrington and Sons of Boston published the book in Philadelphia and Boston. Both editions were reprinted in 1855, and by 1857 the publisher claimed that they had sold ten thousand copies of the book.

In 1860 Watkins married Fenton Harper, and together they purchased a farm outside Columbus, Ohio. The couple had a daughter, Mary. Although little is known about the marriage, Foster has described this period as a “semiretirement” from Watkins’s public life (18). Soon after her husband’s death in 1864, Harper returned to New England and resumed her lectures. After the Civil War, she began lecturing in the South. She was particularly concerned with the future of the newly freed people. This trip would greatly influence Harper’s literature. Three of her books, in particular, are concerned with Reconstruction efforts: a serialized novel, Minnie’s Sacrifice (1869); a book of poetry, Sketches of Southern Life (1871); and her most famous novel, Iola Leroy (1896).

Significantly, the vision of a new nation that emerges in Harper’s literature is not only one of racial equality but also one in which gender equality is represented as crucial to the fulfillment of the American creed of liberty. Harper participated in many women’s organizations, including the American Women’s Suffrage Association, the National Council of Women, the Women’s Christian Temperance Union, and the First Congress of Colored Women in the United States. Her status as both a woman and an African American, however, placed her in a complicated position, particularly as early white feminists, such as Susan B. Anthony and Lucretia Mott, used racist propaganda to assert the importance of women’s suffrage over black male suffrage.

Harper, along with FREDERICK DOUGLASS, participated in the 1869 American Equal Rights Association meeting to debate the proposed Fifteenth Amendment, which would grant suffrage to black men. Harper supported the vote for black men: “When I was at Boston there were sixty women who left work because one colored woman went to gain a livelihood in their midst. If the nation could handle one question I would not have the black woman put a single straw in the way if only the men of the race could obtain what they wanted.” (Boyd, 128). Harper continued her activism on behalf of African American and women’s rights well into the 1890s, becoming the vice president of the National Council of Negro Women, which she had helped found in 1896.

Little is known about Harper between 1901 and her death in Philadelphia in 1911. Indeed, though she was a well-known public figure throughout much of the nineteenth century, many of the details of her life and work remain unknown. The rediscovery in the early 1990s of three of her novels—Minnie’s Sacrifice (1869), Sowing and Reaping (1876–1877), and Trial and Triumph (1888–1889)—all published in the African Methodist Episcopal Church periodical the Christian Recorder, suggests that there is probably much more to know about the life and career of one of the most prolific and popular black writer of the nineteenth century.

Frances E. W. Harper’s papers are housed at the Moorland-Spingarn Research Center of Howard University and at the Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture of the New York Public Library.

Boyd, Melba Joyce. Discarded Legacy: Politics and Poetics in the Life of Frances E. W. Harper 1825–1911 (1994).

Foster, Frances Smith. “Introduction” in A Brighter Coming Day: A Frances Ellen Watkins Harper Reader (1990).

Still, William. The Underground Rail Road (1872).

—CASSANDRA JACKSON

HARRINGTON, OLIVER W.

HARRINGTON, OLIVER W.(14 Feb. 1912–2 Nov. 1995), cartoonist, was born Oliver Wendell Harrington in New York City, the son of Herbert Harrington, a porter, and Euzenie Turat. His father came to New York from North Carolina in the early 1900s when many African Americans were seeking greater opportunities in the North. His mother had immigrated to America, arriving from Austria-Hungary in 1907, to join her half sister. Ollie Harrington grew up in a multiethnic neighborhood in the south Bronx and attended public schools. He recalled a home life burdened by the stresses of his parents’ interracial marriage and the financial struggles of raising five children. From an early age, he drew cartoons to ease those tensions.

In 1927 Harrington enrolled at Textile High School in Manhattan. He was voted best artist in his class and started a club whose members studied popular newspaper cartoonists. Exposure to the work of Art Young, Denys Wortman, and Daniel Fitzpatrick later influenced his style and technique. About that time, toward the end of the Harlem Renaissance, he began to spend considerable time in Harlem and became active in social groups there. Following his graduation from Textile in 1931, he attended the National Academy of Design school. There he met such renowned artists and teachers as Charles L. Hinton, Leon Kroll, and Gifford Beal. During his years at the Academy, Harrington supported himself by drawing cartoons and working as a set designer, actor, and puppeteer.

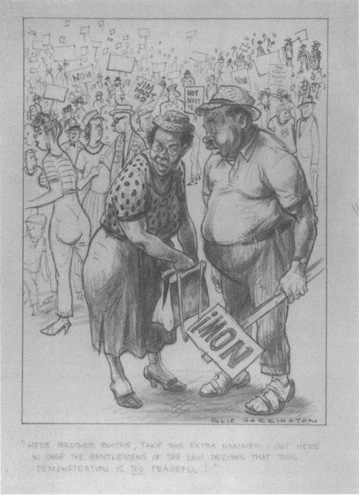

In 1932 he published political cartoons and Razzberry Salad, a comic panel satirizing Harlem society. They appeared in the National News, a newspaper established by the Democratic party organization in Harlem, which folded after only four months. He then joined the Harlem Newspaper Club and was introduced to reporters such as Ted Poston, Henry Lee Moon, and Roi Ottley of the Amsterdam News, as well as Bessye Bearden of the Chicago Defender and her son ROMARE BEARDEN. In 1933, Harrington submitted cartoons to the Amsterdam News on a freelance basis. During the next two years, he also attended art classes at New York University with his friend Romare Bearden. In May 1935, he joined the staff of the News and created Dark Laughter, soon renamed Bootsie after its main character, a comic panel that he would draw for more than thirty-five years. Harrington remarked that “I simply recorded the almost unbelievable but hilarious chaos around me and came up with a character” (Freedomways 3, 519).

Cartoonist, journalist, and expatriate Oliver W. Harrington was best known for Bootsie, a cartoon character in an urban black community, and an African American aviator named Jive Gray. The Walter O. Evans collection

When the Newspaper Guild struck the News in October 1935, Harrington, while not a guild member, supported the strike and would not publish his cartoons until it was settled. During the strike, he became friends with journalists BENJAMIN JEFFERSON DAVIS JR. (later a New York City councilman) and Marvel Cooke, who were members of the Communist Party. While probably not a party member, he maintained active ties to the left from that time. Harrington soon returned to freelance work and taught art in a WPA program. Edward Morrow, a Harlem reporter and graduate of Yale University, and Bessye Bearden encouraged him to apply to the School of the Fine Arts at Yale, which accepted him in 1936. Supporting himself with his Bootsie cartoons (which he transferred to the larger circulation Pittsburgh Courier in 1938), scholarship assistance, and waiting on tables at fraternities, Harrington received a Bachelor of Fine Arts degree in 1940. He won several prizes for his paintings, although not a prestigious traveling fellowship at graduation, which he believed was denied him because of his race.

In 1942, after working for the National Youth Administration for a year, Harrington became art editor for a new Harlem newspaper, the People’s Voice, edited by ADAM CLAYTON POWELL JR. He also created a new comic strip, Live Gray. In 1943 and 1944 he took a leave from the Voice to serve as a war correspondent for the Pittsburgh Courier. While covering African American troops, including the Tuskegee Airmen, in Italy and France, he witnessed racism in the military to a degree he had not experienced before. In Italy he met WALTER WHITE, executive secretary of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP).

In 1946 White, who was attempting to strengthen the NAACP’s public relations department following racial violence against returning veterans, hired Harrington as director of public relations. But by late 1947 the two had become estranged and Harrington resigned to become more active politically. With the Bootsie cartoons and book illustration work again his principal source of income, and after ending a brief wartime marriage, he joined a number of political committees in support of the American Labor Party and Communists arrested in violation of the Smith Act. In 1950 he became art editor of Freedom, a monthly newspaper founded by Louis Burnham and PAUL ROBESON. He also taught art at the Jefferson School for Social Sciences, a school that appeared on the Attorney General’s list of subversive organizations. Informed of his ties to the school, the FBI opened a file on Harrington.

By early 1952, with some of his friends under indictment and others facing revocation of their passports, Harrington left the United States for France. Whether he had knowledge of the FBI investigation is unclear, but by the time he reached Paris, the Passport Office there had been instructed to seize his passport if the opportunity arose. Meanwhile, Harrington settled into a life centered around the Café Tournon with a group of expatriate artists and writers that included RICHARD WRIGHT and CHESTER HIMES. Himes called Harrington the “best raconteur I’d ever known.” His Bootsie cartoons and illustration work continued to provide income and he traveled throughout Europe. For a short time, following a brief second marriage in 1955, he settled in England, but he returned to Paris in 1956 as the Algerian War was worsening. The war divided the African American community, and Harrington became embroiled in a series of disputes with other expatriates. His visit to the Soviet Union in 1959 as a guest of the humor magazine Krokodil again attracted intelligence officials.

Saddened by the death of his close friend Richard Wright, and his income dwindling due to financial difficulties at the Courier, in 1961 Harrington traveled to East Berlin for a book illustration project and soon settled there for the remainder of his life. He submitted cartoons to Das Magasin and Eulenspiegl and in 1968 became an editorial cartoonist for the Daily Worker, later People’s Weekly World. His press credentials enabled him to travel to the West, and many of his old friends, including Paul Robeson and LANGSTON HUGHES, visited him in East Germany. In 1972 Harrington returned for a brief visit to the United States; in the 1990s he visited more regularly. In 1994, after the publication of two books of his cartoons and articles raised interest in his work, he was appointed journalist-in-residence for a semester at Michigan State University. He died in East Berlin. He was survived by his third wife, Helma Richter, and four children: a daughter from his second marriage, a son from his third, and two daughters from relationships with women to whom he was not married. Harrington’s complex personal life, as well as his politics, was sometimes a motive for his travels.

Harrington was often referred to as a “self-exile,” but he never described himself that way. “I’m fairly well convinced that one is an exile only when one is not allowed to live in reasonable peace and dignity as a human being among other human beings” (Why I Left America, 66). Remembered as the premier cartoonist of the African American press for three decades and a central figure in the expatriate community in Paris in the 1950s, he battled racism through his art, his writings, and an alter ego named Bootsie.

Inge, M. Thomas, ed. Dark Laughter: The Satiric Art of Oliver W. Harrington (1993).

_______. Why I Left America and Other Essays (1993).

Stovall, Tyler. Paris Noir: African Americans in the City of Light (1996).

Obituary: New York Times, 7 Nov. 1995.

—CHRISTINE G. MCKAY

HARRIS, BARBARA

HARRIS, BARBARA(12 June 1930–), Episcopal bishop, was born Barbara Clementine Harris in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, the middle child of Walter Harris, a steelworker, and Beatrice Price, who worked as a program officer for the Boys and Girls Club of Philadelphia and later for the Bureau of Vital Statistics for the Commonwealth of Pennsylvania. Barbara was born the day after St. Barnabas Day, and her family attended St. Barnabas Church; hence they named her Barbara.

Barbara graduated from the Philadelphia High School for Girls in 1948 and then attended the Charles Morris Price School of Advertising and Journalism. Upon completion of the program, she began a twenty-year career as a public relations consultant for Joseph V. Baker Associates, a black-owned national public relations firm headquartered in Philadelphia, eventually becoming president of the company. While in this office, she entered into a brief marriage, which ended in divorce. In 1968 Sun Oil recruited her as a community relations consultant. She stayed with Sun Oil for twelve years, rising to the position of manager of their public relations department. Her career was groundbreaking, and she worked hard to dismantle barriers for both women and African Americans in a predominately white male profession.

Harris, however, found her life’s work not in the corporate world, but in the church. Always active in her church, she taught Sunday school and sang in the choir. She brought her friends to church with her no matter how late they had stayed out on Saturday night. She encouraged the parish of St. Barnabas to start a youth group and later initiated and took charge of a group for young adults. For fifteen years she volunteered with the St. Dismas Society, visiting prisons to conduct services on weekends and to counsel and befriend prisoners. During the summer of 1964 she helped register black voters in Mississippi, and the following year she took part in the march led by MARTIN LUTHER KING JR. from Selma to Montgomery, Alabama.

Even in the church Harris witnessed and experienced discrimination, and she came to recognize the need for change. In 1968 the General Convention of the Episcopal Church called a special convention in South Bend, Indiana, to address the concerns of African Americans in the church. As a direct result of the efforts of that convention, which Harris attended, the church began a long—and still unfinished—journey toward eliminating discrimination in the church.

In 1968 Harris transferred her membership to the more activist Episcopal Church of the Advocate in North Philadelphia. The rector, the Reverend Paul Washington, was a staunch fighter for justice who believed that the church should be the vehicle for transformation in the community. In the 1960s he hosted several controversial meetings, including an August 1968 Black Power convention that included such leading activists as STOKELY CARMICHAEL and H. RAP BROWN and that drew both thousands of people and the attention of the FBI.

On 29 July 1974 Harris led the procession into the Church of the Advocate for the controversial ordination into the priesthood of eleven women, “the Philadelphia Eleven.” Two years later, after intense debate, the ordination of women as priests was sanctioned by the General Convention of the Episcopal Church. Harris soon began to hear the call to ordination herself. Because she could not just leave her career to attend seminary on a full-time basis, the Diocese of Pennsylvania made arrangements for her to attend classes at Villanova University from 1977 to 1979, and to study with clergy in the area. After several years she took the General Ordination Examinations required of all seminary graduates and passed with flying colors. She was ordained a deacon in 1979 and a priest in 1980.

After her ordination Harris served at the Church of the Advocate and then spent four years as priest in charge at the Church of St. Augustine of Hippo, in the Philadelphia suburb of Norristown, breathing new life into a congregation that had been moribund and on the verge of closing. During this period she also served as a chaplain to the Philadelphia County Prison, continuing her ministry to prisoners, giving particular attention to the “lifers,” the long-term prisoners who seldom had visitors and were largely forgotten. In 1984 Harris became the executive director of the Episcopal Church Publishing Company. The primary publication of the company was The Witness, a liberal magazine with a history of speaking out on current issues. Harris proved to be a catalyst for the magazine’s emphasis on issues of racism, sexism, classism, and heterosexism, both in the church and in society. Harris regularly contributed a hard-hitting, outspoken column entitled “A Luta Continua” (“The Struggle Continues”), which brought her to the attention of a national and international audience.

In the spring of 1987 the Diocese of Massachusetts held a conference on women in the episcopate, with many ordained women in attendance. Harris was one of the speakers and made a great impact on all those who were present. The following spring the diocese began the process of identifying those clergy who would stand for election later that year as suffragan bishop, an assistant to the diocesan bishop, and there was talk of adding women to the list of candidates. The Episcopal Church met in convention and tried to pass a resolution to appease those opposed to the election of a woman bishop, but when the Diocese of Massachusetts released the names of the candidates, Barbara Harris was one of two women on the list. That summer the Archbishop of Canterbury hosted the Lambeth Conference, a gathering of Anglican bishops held every ten years. There was much concern and debate over the Massachusetts election, for fear that electing a woman might cause a division in the Anglican Communion and endanger ecumenical relations with the Roman Catholic Church.

Harris went to the Lambeth Conference as a member of the press corps in her role with the Episcopal Church Publishing Company and was continually bombarded by participants and the other press members. To some she became a symbol of all that was wrong with the Episcopal Church, or at least with its “liberal” element. Objections to Harris’s election were raised on a number of fronts—her nontraditional education and theological training, her status as divorced (an objection not raised in regard to males also being considered), her liberal social activism—but certainly the greatest impediment in the minds of many was simply the fact that she was a woman. The conference, however, ultimately allowed for the consecration of women by ruling that national churches had the right to choose their own bishops.

The Massachusetts election took place on Saturday, 25 September 1988, and Harris was stunned and surprised to be elected on the fifth ballot. Her strength and her faith were now going to be tested. The next step was for a majority of Episcopal dioceses to consent to the election. Although this was nominally a vote on whether the election was in accord with the church constitution, it was in reality based on the person and not the process. Harris’s credentials, her qualifications, and her writings were again questioned. However, consent was obtained, and she subsequently got the necessary number of votes in the House of Bishops.

Harris was consecrated bishop on 11 February 1989. The day was glorious; Boston’s Hynes Auditorium was packed with over eight thousand clergy and laypeople, representing the diversity and breadth of the Episcopal Church. As was expected, there were formal protests during the service. After the protests, Harris’s mother walked over to her and said, “Don’t worry, baby, everything will be all right. God and I are on your side.” The Right Reverend Barbara Clementine Harris served as suffragan bishop in Massachusetts for over thirteen years, consistently carrying out her ministry of compassion, healing, and reconciliation and always speaking out for justice on behalf of the marginalized in our society. Harris has received sixteen honorary doctorate degrees from a broad range of colleges, universities, and seminaries and has traveled around the world sharing the good news. After retiring in November 2002, she agreed to serve part-time in the Diocese of Washington as an assisting bishop.

The debate over the role of women in the church grows quiet at times, but it has not gone away. The role of women was again called into question at the 1998 Lambeth Conference, which also saw heated discussions on homosexuality. The specter of schism in the Episcopal Church in the United States was again raised at the General Convention in 2003 in the debate over the confirmation of the openly gay canon Gene Robinson as bishop of New Hampshire. At the convention, Harris reminded those present of the similar fears felt in 1989 and pointed out that the Anglican Communion remains intact. Delivering a sermon in her home parish the day after her own election as bishop in 1988, Harris expressed in metaphor the significance of that event, a metaphor that, applied more broadly, captures the difficulty of bringing about change in the face of long-standing beliefs and attitudes: “A fresh wind is indeed blowing. We have seen in this year alone some things thought to be impossible just a short time ago. To some, the changes are refreshing breezes. For others, they are as fearsome as a hurricane.”

Bozzuti-Jones, Mark Francisco. The Mitre Fits Just Fine: A Story about the Rt. Rev. Barbara Clementine Harris, Suffragan Bishop, Diocese of Massachusetts (2003).

—NAN PEETE

HARRISON, HUBERT HENRY

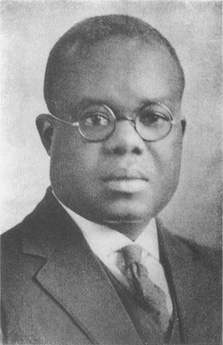

HARRISON, HUBERT HENRY(27 Apr. 1883–17 Dec. 1927), radical political activist and journalist, was born in Concordia, St. Croix, Danish West Indies (now U.S. Virgin Islands), the son of William Adolphus Harrison and Cecilia Elizabeth Haines. Little is known of his father. His mother had at least three other children and, in 1889, married a laborer. Harrison received a primary education in St. Croix. In September 1900, after his mother died, he immigrated to New York City, where he worked low-paying jobs, attended evening high school, did some writing, editing, and lecturing, and read voraciously. In 1907 he obtained postal employment and moved to Harlem. The following year he taught at the White Rose Home, where he was deeply influenced by social worker Frances Reynolds Keyser, a future founder of the NAACP. In 1909 he married Irene Louise Horton, with whom he had five children.

Between 1901 and 1908 Harrison broke “from orthodox and institutional Christianity” and became an “Agnostic.” His new worldview placed humanity at the center and emphasized rationalism and modern science. He also participated in black intellectual circles, particularly church lyceums, where forthright criticism and debate were the norm and where his racial awareness was stimulated by scholars such as bibliophile ARTHUR SCHOMBURG and journalist John E. Bruce. History, free thought, and social and literary criticism appealed to him, as did the protest philosophy of W. E. B. DU BOIS over the more “subservient” one of BOOKER T. WASHINGTON. Readings in economics and single taxism and a favorable view of the Socialist Party’s position on women drew him toward socialism. Then in 1911, after writing letters critical of Washington in the New York Sun, he lost his postal job through the efforts of Washington’s associates and turned to Socialist Party work.

From 1911 to 1914 Harrison was the leading black in the Socialist Party of New York, where he insisted on the centrality of the race question to U.S. socialism; served as a prominent party lecturer, writer, campaigner, organizer, instructor, and theoretician; briefly edited the socialist monthly the Masses; and was elected as a delegate to one state and two city conventions. His series on “The Negro and Socialism” (New York Call, 1911) and on “Socialism and the Negro” (International Socialist Review, 1912) advocated that socialists champion the cause of the Negro as a revolutionary doctrine, develop a special appeal to Negroes, and affirm their duty to oppose race prejudice. He also initiated the Colored Socialist Club (CSC), a pioneering effort by U.S. socialists at organizing blacks. After the party withdrew support for the CSC, and after racist pronouncements by some Socialist Party leaders during debate on Asian immigration, he concluded that socialist leaders put the white “Race First and class after.”

Harrison believed “the crucial test of Socialism’s sincerity” was “the Negro,” and he was attracted to the egalitarian practices and direct action principles of the Industrial Workers of the World (IWW). He defended the IWW and spoke at the 1913 Paterson Silk Strike with Elizabeth Gurley Flynn and “Big Bill” Haywood. Although he was a renowned socialist orator, and was described by author Henry Miller as without peer on a soapbox, Socialist Party leaders moved to restrict his speaking.

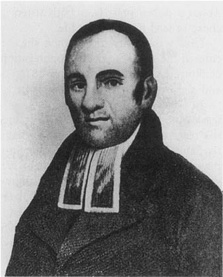

Hubert Henry Harrison, “The Father of Harlem Radicalism.” Schomburg Center

Undaunted, Harrison left the Socialist Party in 1914 and over the next few years established the tradition of street corner oratory in Harlem. He first developed his own “Radical Lecture Forum,” which included citywide indoor and outdoor talks on free thought, evolution, literature, religion, birth control, and the racial aspects of World War I. Then, after teaching at the Modern School, writing theater reviews, and selling books, he started the “Harlem People’s Forum,” at which he urged blacks to emphasize “Race First.”

In 1917, as war raged abroad, along with race riots, lynchings, and discrimination at home, Harrison founded the Liberty League and The Voice, the first organization and newspaper of the militant “New Negro” movement. He explained that the league was called into being by “the need for a more radical policy than that of the NAACP” (Voice, 7 Nov. 1917) and that the “New Negro” movement represented “a breaking away of the Negro masses from the grip of the old-time leaders” (Voice, 4 July 1917). Harrison stressed that the new black leadership would emerge from the masses and would not be chosen by whites (as in the era of Washington’s leadership), nor be based in the “Talented Tenth of the Negro race” (as advocated by Du Bois). The league’s program was directed to the “common people” and emphasized internationalism, political independence, and class and race consciousness. The Voice called for a “race first” approach, full equality, federal antilynching legislation, labor organizing, support of socialist and anti-imperialist causes, and armed self-defense in the face of racist attacks.

Harrison was a major influence on a generation of class and race radicals, from socialist A. PHILIP RANDOLPH to MARCUS GARVEY. The Liberty League developed the core progressive ideas, basic program, and leaders utilized by Garvey, and Harrison claimed that, from the league, “Garvey appropriated every feature that was worthwhile in his movement.” Over the next few years Garvey would build what Harrison described as the largest mass movement of blacks “since slavery was abolished”—a movement that grew, according to Harrison, as it emphasized “racialism, race consciousness, racial solidarity—the ideas first taught by the Liberty League and The Voice.”

The Voice stopped publishing in November 1917, and Harrison next organized hotel and restaurant workers for the American Federation of Labor. He also rejoined, and then left, the Socialist Party and chaired the Colored National Liberty Congress that petitioned the U.S. Congress for federal antilynching legislation and articulated militant wartime demands for equality. In July 1918 he resurrected The Voice with influential editorials critical of Du Bois, who had urged blacks to “Close Ranks” behind the wartime program of President Woodrow Wilson. Harrison’s attempts to make The Voice a national paper and bring it into the South failed in 1919. Later that year he edited the New Negro, “an organ of the international consciousness of the darker races.”

In January 1920 Harrison became principal editor of the Negro World, the newspaper of Garvey’s Universal Negro Improvement Association (UNIA). He reshaped the entire paper and developed it into the preeminent radical, race-conscious, political, and literary publication of the era. As editor, writer, and occasional speaker, Harrison served as a major radical influence on the Garvey movement. By the August 1920 UNIA convention Harrison grew critical of Garvey, who he felt had shifted focus “from Negro Self-Help to Invasion of Africa,” evaded the lynching question, put out “false and misleading advertisements,” and “lie[d] to the people magniloquently.” Though he continued to write columns and book reviews for the Negro World into 1922, he was no longer principal editor, and he publicly criticized and worked against Garvey while attempting to build a Liberty party, to revive the Liberty League, and to challenge the growing Ku Klux Klan.

Harrison obtained U.S. citizenship in 1922 and over the next four years became a featured lecturer for the New York City Board of Education, where Yale-educated NAACP leader WILLIAM PICKENS described him as “a plain black man who can speak more easily, effectively, and interestingly on a greater variety of subjects than any other man I have ever met in the great universities.” In 1924 he founded the International Colored Unity League (ICUL), which stressed that “as long as the outer situation remains what it is,” blacks in “sheer self-defense” would have to develop “race-consciousness” so as to “furnish a background for our aspiration” and “proof of our equal human possibilities.” The ICUL called for a broad-based unity—a unity of action, not thought, and a separate state in the South for blacks. He also helped develop the Division of Negro Literature, History, and Prints of the New York Public Library, organized for the American Negro Labor Congress, did publicity work for the Urban League, taught on “Problems of Race” at the Workers School, was involved in the Lafayette Theatre strike, and lectured and wrote widely. His 1927 effort to develop the Voice of the Negro as the newspaper of the ICUL lasted several months. Harrison died in New York City after an appendicitis attack. His wife and five young children were left virtually penniless.