JONES, ADDISON.

JONES, ADDISON.At that October diocesan convention Jones was received as a candidate for holy orders in the Episcopal Church and was licensed as a lay reader. On 21 October 1794 he formally accepted the position of pastor of St. Thomas Church. At the diocesan convention on 2 June 1795, it was stipulated that St. Thomas Church was not entitled to send a clergyman or any lay deputies to the convention, nor was it “to interfere with the general government of the Episcopal Church.” Jones was ordained a deacon on 23 August 1795 and then priest on September 1804, the first black to become a deacon or a priest in the Episcopal Church. From 1795 until his death, Jones baptized 268 black adults and 927 black infants. His ministry among blacks was so significant that he was called the “Black Bishop of the Episcopal Church.” Jones died in Philadelphia.

The few extant Jones papers are in the Archives of the Episcopal Church, Austin, Texas.

Bragg, George F. The Story of the First of the Blacks, the Pathfinder, Absalom Jones, 1746–1818 (1929).

Lammers, Ann C. “The Rev. Absalom Jones and the Episcopal Church: Christian Theology and Black Consciousness in a New Alliance.” Historical Magazine of the Protestant Episcopal Church (1982): 159–84.

Lewis, Harold T. Yet with a Steady Beat: The African American Struggle for Recognition in the Episcopal Church (1996).

—DONALD S. ARMENTROUT

JONES, ADDISON.

JONES, ADDISON.See Nigger Add.

JONES, BILL T.

JONES, BILL T.(15 Feb. 1952–), dancer and choreographer, was born William Tass Jones in Bunnell, Florida, the tenth of the twelve children of Ella and Augustus Jones, migrant farm workers who traveled throughout the Southeast. The family became “stagnants” in 1959, when they settled in the predominantly white community of Wayland in the Finger Lakes region of upstate New York. There they harvested fruits and vegetables and also operated a restaurant and juke joint.

In childhood Jones navigated between the rural, southern black cultural values of his home life and the predominantly white middle-class world of his peers at school. Black English was spoken at home, white English in the classroom. That experience was not without its complications and, sometimes, pain, but Jones believed that it served him well as a performer by teaching him that the “world was a place of struggle that had to be negotiated” (Washington, 190). He did well at school, won awards for public speaking, directed a production of Arthur Miller’s The Crucible, and starred on the track team. But Jones also cultivated an independent streak that one of his teachers, Mary Lee Shappee, encouraged. An outspoken atheist in a largely devout community, Shappee advised him, “There’s something more than this” (Washington, 191).

Determined to find that “something,” Jones entered the State University of New York at Binghamton in 1970 to study drama and prepare for a career on Broadway. He found himself increasingly isolated from fellow black students, however, believing that they viewed him as an “unauthentic, white dependent Negro” (Jones, 81). Although he had been in relationships with women in high school, he was also sexually attracted to men and was intrigued by a student group poster with the invitation “Gay?? Come Out and Meet Your Brothers and Sisters!!” At the consciousness-raising meeting, Jones confessed that coming out was especially difficult for him, because he was convinced that African Americans felt that being gay was the “ultimate emasculation of the black man” (Jones, 82).

During his second semester Jones met Arnie Zane, a Jewish Italian American photographer and drama student from Queens, New York. In 1971 Zane became Jones’s first male lover, and the couple began a personal and professional partnership that would last for seventeen years. Jones had begun dance lessons shortly before meeting Zane, but it was Zane who inspired his passion for dance. Jones enrolled in Afro-Caribbean and West African dance classes at Binghamton with the Trinidadian choreographer Percival Borde, participated in workshops on contact improvisation, and became grounded in the Cecchetti method of classical ballet. Martha Graham, who codified the language of modern dance, and Jerome Robbins, who choreographed West Side Story, were also influential in his development as a dancer.

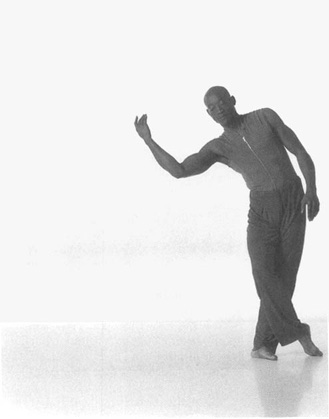

Dancer and choreographer Bill T. Jones has infused the world of international contemporary dance not only with his own personal dance vocabulary but also with social concerns, such as HIV/AIDS, interracial relationships, and tolerance. © Lois Greenfield, 2003

During the early 1970s Jones and Zane lived a peripatetic, bohemian existence, first in Amsterdam and then in San Francisco, before returning to Binghamton in 1974. There the couple helped a fellow dancer, Lois Welk, revive her American Dance Asylum, supplementing their income with part-time jobs—Zane as a go-go dancer and Jones as a laundry worker. By 1976 Jones was beginning to achieve recognition in the dance world, receiving a Creative Artist Public Service Award for Everybody Works / All Beasts Count, a performance in which he spun around half naked in Central Park while shouting, “I love you” to the heavens in memory of two of his favorite aunts.

Determined to establish their own distinctive style, Jones and Zane rejected both the refined, regimented modernism that they believed characterized ALVIN AILEY’s Dance Theater of Harlem and the cultural nationalist aesthetic of the Black Arts Movement. Instead, they developed an avant-garde approach influenced by Yvonne Rainier, a postmodernist choreographer and filmmaker known for her experiments with fragmented movements and for placing characters and narrative in radical juxtapositions. From the beginning of Jones and Zane’s collaboration, reviewers noted that the bodies, movements, and personalities of the two dancers provided the most dramatic juxtaposition of all. As one early review noted: “Mr. Jones is black, with a long, lithe body, a fine speaking voice and a look of leashed hostility. Mr. Zane is white, short and chunky, with a buoyant, strutting walk and the very funny look of an officious floorwalker in a second-rate department store.” (New York Times, 5 Apr. 1981). The couple also experimented with innovative locations for their performances—including the Battery Park Landfill in lower Manhattan—and often employed dancers who had little in the way of professional dance training. Looking back at their work in the late 1970s and early 1980s, Jones recalled that he and Zane “used to turn up our nose at refined technique. We thought it made for dead art. Instead, we’d look for the beauty in falling, running or in watching a large person jump” (People, 31 July 1989).

Jones and Zane left the American Dance Asylum in 1980, and the following year Jones appeared in Social Intercourse: Pilgrim’s Progress, which was one of five pieces by promising newcomers selected for performance at the prestigious American Dance Festival in Durham, North Carolina. In that piece Jones improvised a solo with a monologue in which he paired seemingly paradoxical outbursts: I love white people / I hate white people; Why didn’t you leave us in Africa? / I’m so thankful for the opportunity to be here; and I love women / I hate women. Jones’s provocative style also ensured plenty of detractors, notably the New Yorker’s Arlene Croce, who described his work as narcissistic.

In 1982 Jones and Zane founded Bill T. Jones/Arnie Zane and Company, with Zane focusing mainly on directing and managing and Jones starring as the primary dancer. The company debuted the following year at the Brooklyn Academy of Music with Intuitive Momentum, a performance that drew on the martial arts, vaudeville, and social dance and which received positive reviews for the dancers’ frenzied, acrobatic movements. The company won its first New York Dance and Performance Award (known as “Bessies”) for their 1986 season at New York’s Joyce Theater, and soon emerged as among the most popular and challenging troupes in the world of modern dance. In March 1988, however, with Jones at his bedside, Zane died of AIDS-related lymphoma. Jones, too, was diagnosed as HIV positive in the 1980s but remains asymptomatic. The couple’s last collaboration, Body against Body (1989), includes Zane’s photos, Jones’s poetry and prose, performance scripts, and commentaries by dancers, critics, composers, and others.

Jones’s career continued to flourish after his partner’s death, and the company—which retained Zane’s name—remained true to its founders’ vision of an inclusive troupe that embraced different races, sexual orientations, and body shapes. Jones received a second Bessie in 1989 for D-Man in the Waters, and the following year, along with his sister Rhodessa Jones, he won an Isadora Duncan Dance Award (Izzy) for Perfect Courage.

Despite his growing fame, Jones continued to infuriate some reviewers, notably for Last Supper at Uncle Tom’s Cabin / The Promised Land (1990), a multimedia work that ended with audience members joining the dancers on stage in taking off all of their clothes. Jones responded to those critics by noting that the nudity was the entire point of the piece. “In this polarized, sexually very confused city,” he told the New York Times, “can we stand up as a group and not be ashamed of our nakedness?” (4 Nov. 1990). Even more controversial was Still/Here (1994), a work that addressed the subject of death and dying. The performance incorporated videotaped testimonies of a diverse range of people with terminal illnesses that Jones had collected at “Survival Workshops” that he had organized in several American cities. The New Yorker’s Arlene Croce dismissed the work as “victim art” and refused to attend the performance, provoking a firestorm of debate among Jones’s many admirers and detractors.

The clearest answer to Jones’s critics has been the steady flow of awards that he and his company continue to receive. These honors include a MacArthur Foundation award in 1994, a Laurence Olivier Award for Outstanding Achievement in Dance and Best New Dance Production for We Set Out Early . . . Visibility Was Poor (1999), a second Izzy for Fantasy in C-Major (2001), and a third Bessie for The Table Project and The Breathing Show (2001). In addition to choreographing more than fifty works for his own company, Jones has also received commissions for works for, among others, the Boston Ballet, the Berlin Opera Ballet, the Houston Grand Opera, and the Glyndebourne Festival in England. In 1995 Jones teamed up with the legendary jazz drummer Max Roach and the Nobel Prize-winning author TONI MORRISON to produce Degga, a collaboration of dance, percussion, and spoken word at the Lincoln Center’s Serious Fun Festival. Perhaps the most significant and fitting of Jones’s awards came in 2002, however, when the Dance Heritage Coalition of America named him an “Irreplaceable Dance Treasure.”

Jones, Bill T., and Peggy Gillespie. Last Night on Earth (1995).

Gates, Henry Louis. Thirteen Ways of Looking at a Black Man (1997).

Washington, Eric K. “Sculpture in Flight.” Transition 62 (1993).

—ELSHADAY GEBREYES

—STEVEN J. NIVEN

JONES, EUGENE KINCKLE

JONES, EUGENE KINCKLE(30 July 1885–11 Jan. 1954), social welfare reformer, was the son of Joseph Endom Jones and Rosa Daniel Kinckle, a fairly comfortable and prominent middle-class black couple in Richmond, Virginia. Both his parents were college educated. Jones grew to maturity at a period in American history when the federal government turned its back on providing full citizenship rights to African Americans. Although the Civil War had ended slavery and the Fourteenth and Fifteenth Amendments to the U.S. Constitution had guaranteed blacks equal rights, state governments in the South began to erode those rights following the end of Reconstruction in 1877.

Jones grew up in Richmond at a time of racial polarization, and he watched as African American men and women struggled to hold on to the gains that some had acquired during Reconstruction. Like others in W. E. B. Du BoiS’s “talented tenth,” he saw education as the best means of improving his own life and of helping others, and he graduated from Richmond’s Virginia Union University in 1905. He then moved to Ithaca, New York, to attend Cornell University, where, in 1906, he was a founding member of the nation’s first black Greek lettered fraternity, Alpha Phi Alpha. He later helped found two other chapters at Howard University and at his alma mater, Virginia Union. He graduated from Cornell with a master’s degree in 1908 and taught high school in Louisville, Kentucky, until 1911. In 1909 he married Blanche Ruby Watson, with whom he went on to have two children.

In 1911 Jones began working as the first field secretary for the National Urban League (NUL), a social service agency for blacks that had been founded in New York City in 1910. By the 1920s he had superimposed the philosophy and organization of Alpha Phi Alpha upon the league, which was by that time dealing with the problems of poverty, poor housing, ill health, and crime that emerged during the first great black migration from the rural South to the urban North. He worked diligently to establish as many local branches as possible, believing that the concept of local branches would further the NUL’s national agenda. Jones also placed key individuals in the directorships of local branches, which enabled him to be informed at all times of the conditions in black urban areas. In addition, he established fellowship programs to ensure that a larger pool of African American social workers would be available to tackle the problems that rural migrants faced in the burgeoning inner cities of the North. In 1923, along with the NUL’s research director, the sociologist CHARLES S. JOHNSON, Jones helped launch Opportunity, a journal that addressed the problems faced by urban blacks but which also provided an outlet for a new generation of African American writers and artists, including AARON DOUGLAS and LANGSTON HUGHES.

In 1915 Jones and a group of other black social reformers founded the Social Work Club to address the concerns of African American social workers. This organization was short-lived, for by 1921 black social workers had become actively involved with the American Association of Social Workers. In 1925 the National Conference of Social Work elected Jones treasurer, making him the first African American on its executive board. Jones went on to serve the organization until 1933, by which time he had risen to the position of vice president of the National Conference of Social Work (NCSW). This post put him in a position of importance within the national structure of the social work profession. During Jones’s tenure as an executive officer of the NCSW, he worked with other black social workers to make white reformers aware—often for the first time—of the urban problems particular to African Americans.

In 1933 Jones became one of the leading black figures in Washington, D.C., when he took a position with the Department of Commerce as an adviser on Negro Affairs. Perhaps no single person matched Jones’s efforts in delivering to African American communities the opportunities that became available to them through the federal government’s newly initiated relief programs. While in Washington, he also served as the voice of the black community through the NUL and its local branches. In so doing, Jones came to personify the NUL in the 1930s, while he served along with MARY MCLEOD BETHUNE, ROBERT WEAVER, and WILLIAM HENRY HASTIE as part of President Franklin Roosevelt’s so-called Black Cabinet.

By the time of Jones’s retirement in 1940, the NUL had become a relatively conservative organization. A younger generation was rising to prominence, and many African Americans were no longer willing to wait as patiently for justice and their full citizenship rights as Jones and his contemporaries had been willing to do. However, Jones’s handpicked successor, Lester B. Granger, continued in the more conservative style of leadership embraced by Jones. The NUL therefore did not engage in the direct methods of the modern civil rights movement until 1960, when WHITNEY YOUNG was appointed executive secretary. Jones died in New York after a short illness in January 1954.

Like other middle-class blacks, Jones felt a strong sense of responsibility for uplifting less fortunate members of his race. In that regard, his social views conformed with other turn-of-the-century African American social reformers, such as Du Bois, CARTER G. WOODSON, JAMES WELDON JOHNSON, IDA B. WELLS-BARNETT, and MARY CHURCH TERRELL. The accomplishments of these progressive era reformers have historically been ignored compared with those of their white counterparts, such as the settlement house leader Jane Addams. Scholars have recently begun to acknowledge, however, that African American middle-class activists like Jones led the early-twentieth-century social reform movement in black America, even though the middle-class ethos of these reformers did not exactly mirror that of the larger white society. Above all, Jones’s tenure as executive secretary of the NUL showcases the achievements of early black social reformers. He also helped make the league an African American, and an American, institution.

Information on Jones can be found in the National Urban League Archives in the Manuscript Division of the Library of Congress, Washington, D.C.

Carlton-LaNey, Iris B., ed. African American Leadership: An Empowerment Tradition in Social Welfare History (2001).

Weiss, Nancy J. The National Urban League, 1910–1940 (1974).

Wesley, Charles H. The History of Alpha Phi Alpha: A Development in Negro College Life (1929).

—FELIX L. ARMFIELD

JONES, JAMES EARL

JONES, JAMES EARL(17 Jan. 1931—), actor, was born in Arkabutla, Mississippi, the only child of Robert Earl Jones, a prizefighter and actor, and Ruth Williams Connoly, a seamstress. James’s parents parted ways in search of work before their son was born, and he was raised by his mother’s parents, John and Maggie Connoly. He grew up on their farm, alongside seven children and two other grandchildren. From an early age James was put to work beside his aunts, uncles, and cousins, tending the livestock, hunting, and helping with harvests. At night Maggie Connoly would regale the family with lurid bedtime stories—tales of lynchings, hurricanes, and rapes. The Connolys knew that Mississippi schools offered their children little, and in 1936 they planned a move to Dublin, Michigan. Before the family left, John Connoly took James to his paternal grandmother’s house in Memphis, but James refused to leave the car. He followed the family north later that year.

Soon after the move to Michigan, James began to stutter; he spoke only to his family, to the farm animals, and to himself. In grammar school he managed to get by on written work, and it was not until high school that someone sought to help him. An English teacher, Donald Crouch, pushed James to join the debate team. With practice, James proved a captivating orator and, by the end of high school, managed to overcome his stuttering in conversation, too. As he regained his powers of speech, he took to the classics Crouch taught and spent many an afternoon reading Shakespeare aloud in the fields.

At this time James’s father was living in New York City and trying his hand at theater. When James announced to his uncle Randy that he, too, would be an actor, John Connoly pounced on his grandson and struck him in the back of the head. In 1949 James entered the University of Michigan on a Regents Scholarship and enrolled in premed classes, but the pull of the theater proved too strong; he began taking roles in school plays and spending his holidays in summer-stock productions.

Jones had joined the Reserve Officer Training Corps to help fund his education, and he abandoned school in 1953, just before graduation, convinced that he would shortly be killed in the Korean War. But the conflict cooled off that summer, and Jones spent his two years of service at the Cold Weather Training Command in Colorado. He enjoyed the strenuous work and the solitude of the Rockies, but when he told his commanding officer that he wanted to be an actor, he was urged to pursue theater before committing to military life. Jones finished his BA through an extension program and moved in with his father in New York. He enrolled in acting workshops at the American Theatre Wing, paying his way with funds from the GI Bill.

After twenty-four years of separation, Jones and his father did not get along well, and during one argument they nearly came to blows. But if the two did not bond as father and son, they came together over their shared passion. late into the night, they would recite scenes from Othello. After six months Jones moved to the Lower East Side and continued his austere routine of workshops, auditions, and menial jobs. In 1957 he landed his first Broadway role as an understudy to Lloyd Richards in The Egghead. That same year he found more substantial work in Ted Pollock’s play Wedding in Japan.

In the early 1960s off-Broadway theater offered a heady cocktail of new talent, edgy scripts, and rundown venues. Jones entered the fray as Deodatus Village in the 1961 production of Jean Genet’s The Blacks, a savage and absurdist allegory of race relations written for an all-black cast. Critics at the Village Voice and the New Yorker swooned, and both singled Jones out for praise from a cast that included Cicely Tyson, Roscoe Lee Browne, Lou Gossett, and MAYA ANGELOU. Given the charged political climate and the play’s violent language, performances were hard on audiences and performers alike, and Jones left the cast, to recover, some six times during the play’s two-year run. In 1962 Jones earned several awards for his performances in Moon on a Rainbow Shawl and won an Obie as Best Actor in Off Broadway Theater for his work in Clandestine on the Morning Line. Throughout the 1960s Jones built a name for himself at the New York Shakespeare Festival and his 1964 title role in Othello won a Drama Desk Award for Best Performance. The following year, he received two Obies for his work in Othello and in Bertolt Brecht’s Baal.

No role propelled his career, however, like his 1967 portrayal of Jack Jefferson, a character based on JACK JOHNSON, the first black heavyweight boxing champion, in Howard Sackler’s play The Great White Hope. To prepare for the audition he began a brutal exercise regimen. Six feet, two inches tall, slimmed down to two hundred pounds, his head shaved and shiny, Jones landed the part, which earned him his first Tony Award and another Drama Desk Award. The play, which challenged and titillated audiences with its interracial love story, moved from the Arena Stage in Washington, D.C., to Broadway in 1968. Jones reprised the role two years later in Martin Ritt’s film adaptation of the play, which costarred Jane Alexander and earned Jones an Oscar nomination.

SIDNEY POITIER urged Jones to avoid the stock parts film and television typically offered black actors. For several years Jones heeded the advice, but in 1964 he took a small part as a pilot in Stanley Kubrick’s film Dr. Strangelove. Jones also began to make inroads into the small screen. A 1965 stint on As the World Turns made him the first African American with a continuing role in a daytime soap opera. In 1967 Jones married Julienne Marie Hendricks, who had played Desdemona to his Othello in 1964. But Jones’s growing success brought a new measure of instability to his life, and the marriage did not last.

On stage in 1970 Jones appeared in LORRAINE HANSBERRY’s play Les Blancs and costarred with RUBY DEE in Athol Fugard’s Boesman and Lena. He continued working in film and television throughout the early and mid 1970s. Highlights included playing the title role in King Lear on television in 1974 and appearing as the big screen’s first African American president of the United States in The Man in 1972. In 1977 Jones was cast as PAUL ROBESON in the one-man show based on the life of the actor, singer, and activist who had once been feted for his magnetic stage presence, but wound up blacklisted as a result of his politics. Robeson died in 1976, and the play was meant to honor his career, but it, too, fell victim to censorship. Rallied by the actor’s son, Paul Robeson Jr., the Ad Hoc Committee to End the Crimes against Paul Robeson charged that the play distorted Robeson’s life. Theater after theater was picketed. After one of the last performances, Jones delivered a blistering indictment of the committee’s antics. In 1979 Jones starred in the play’s film adaptation directed by Lloyd Richards.

Jones, who continued his stage work in such plays as Fugard’s Master Harold and the Boys and Of Mice and Men, has been known to stop mid-performance to shush members of the crew and the audience or to ask them in his round, resonant basso to “stop popping that fucking bubble gum!” (Jones, 334). His relationships with directors and writers have also been strained at times. In 1981 while preparing for a new production of Othello, Jones accused the director Peter Coe of turning Shakespeare’s tragedy into a farce. In 1987’s Fences, a father-son play about a poor black family, Jones butted heads with the playwright AUGUST WILSON. In spite of these clashes—or perhaps because of them—both plays won critical acclaim. Othello received a Tony for Best Revival, while Fences won Jones both a Tony and a Drama Desk for his performance.

In early 1982 Jones married Cecilia Hart. That December their son, Flynn Earl Jones, was born. To support his new family, Jones chose to spend more time in the unglamorous world of made-for-TV movies, bit parts, and voice-overs. The last came in droves after Jones lent his voice to the role of the archvillain Darth Vader in George Lucas’s Star Wars films released in 1977, 1980, and 1983. Asked why he had agreed to provide the film’s most evil character with a black voice, Jones replied that the work took two hours and paid seven thousand dollars.

Following Fences, Jones decided that he no longer had the energy for leading roles on the stage, which may account for his increased presence on the screen. In addition to his many featured roles on television, Jones appeared in a variety of films, including John Sayles’s Matewan (1987), about coal miners struggling to form a union in Mingo County, West Virginia, in 1920. Jones worked in comedy as well, in such films as Soul Man (1986) and the Eddie Murphy vehicle Coming to America (1988). In 1989 he appeared as the reclusive, misanthropic writer in Field of Dreams, one the year’s most popular films. Throughout the 1990s Jones appeared in films and on television at an astounding rate. He played Admiral Greer in the highly popular films The Hunt for Red October, Patriot Games, and Clear and Present Danger, based on the novels by Tom Clancy. Notable leading roles included the title role in the television series Gabriel’s Fire, in which he starred for two seasons, and a priest accused of murder in the 1995 film version of Alan Paton’s novel about South Africa, Cry the Beloved Country.

More and more, however, Jones is in demand simply as himself, as a host, presenter, and narrator. He voiced the animated characters King Mufasa in Disney’s The Lion King (1994) and the long-silent Maggie on The Simpsons. A popular commercial pitchman, Jones and his distinctive voice have become part of American daily life, telling television viewers that they are watching CNN or thanking callers for using a Verizon pay phone. Instead of asking for autographs, fans beg Jones to record their answering machine messages. Over the last half century Jones has appeared in over two hundred films and television shows. For his work as an actor, Jones has won four Emmy awards, two Tony awards, two Obie awards, five Drama Desk awards, a Golden Globe award and a Grammy. A presidential appointee to the National Council on the Arts from 1970 to 1976, Jones has received five honorary doctorates and the NAACP Hall of Fame Image Award. In 1992 he was awarded the National Medal of Arts by President George Bush. While Jones’s career displays a boundless range, depth, and energy, most of his fans see his legacy in more grandiose terms; he is, quite simply, the voice of America.

Jones, James Earl, and Penelope Niven. James Earl Jones: Voices and Silences (1993, 2002).

Bryer, Jackson R., and Richard A. Davison, eds. The Actor’s Art: Conversations with Contemporary American Stage Performers (2001).

Gill, Glenda E. No Surrender! No Retreat!: African American Pioneer Performers of Twentieth-Century American Theater (2000).

—CHRIS BEBENEK

JONES, LEROI.

JONES, LEROI.See Baraka, Amiri.

JONES, LOÏS MAILOU

JONES, LOÏS MAILOU(3 Nov. 1905–9 June 1998), artist and teacher, was born in Boston, Massachusetts, the second of two children of Carolyn Dorinda Adams, a beautician, and Thomas Vreeland Jones, a building superintendent. Loïs’s father became a lawyer at age forty, and she credited him with inspiring her by example: “Much of my drive surely comes from my father—wanting to be someone, to have an ambition” (Benjamin, 4). While majoring in art at the High School of Practical Arts, Lois spent afternoons in a drawing program at Boston’s Museum of Fine Arts. On weekends she apprenticed with Grace Ripley, a prominent designer of theatrical masks and costumes. From 1923 to 1927 she studied design at the School of the Museum of Fine Arts and became one of the school’s first African American graduates. Upon graduation, Lois, who had earned a teaching certificate from the Boston Normal Art School, received a one-year scholarship to the Designers Art School of Boston, where she studied with the internationally known textile designer Ludwig Frank. The following summer, while attending Harvard University, she designed textiles for companies in Boston and New York. She soon learned, however, that designers toiled in anonymity, and so, seeking recognition for her creations, she decided to pursue a career as a fine artist.

The Jones family spent summers on Martha’s Vineyard, the beauty of which inspired Lois to paint as a child and where her first solo exhibitions, at age seventeen and twenty-three, were held. A retreat for generations of African American intellectuals, Martha’s Vineyard exposed the young artist to career encouragement from the sculptor META WARRICK FULLER, the composer HARRY BURLEIGH, and Jonas Lie, president of the National Academy of Design. When she applied for a teaching job at the Museum of Fine Arts, administrators patronizingly told her to “go South and help your people.” Jones did go to the South in 1928, but at the behest of CHARLOTTE HAWKINS BROWN, who offered her a position developing an art department at the Palmer Memorial Institute, an African American school in North Carolina. Two years later Jones was recruited by Howard University and remained on the faculty until her retirement in 1977.

For forty-seven years she taught design and watercolor (which was considered more appropriate to her gender than oil painting) to generations of students, including ELIZABETH CATLETT. “I loved my students,” Jones told the Washington Post when she was asked about teaching. “Also it gave me a certain prestige, a certain dignity. And it saved me from being trampled upon by the outside” (1 Mar. 1978). Jones emphasized craftsmanship and encouraged each student’s choice of medium and mode of expression. As a former student, Akili Ron Anderson, recalled, “Loïs Jones would punish you like a parent . . . but when you met her standards, when you progressed, she loved you like your mother” (Washington Post, 26 Dec. 1995).

Jones remained committed to her own work and education, and she received a BA in Art Education magna cum laude from Howard University in 1945. In the 1930s she was a regular exhibitor at the Harmon Foundation, and from 1936 to 1965 she illustrated books and periodicals, including African Heroes and Heroines (1938) and the Journal of Negro History, for her friend CARTER G. WOODSON. After receiving a scholarship to study in Paris in 1937, Jones took a studio overlooking the Eiffel Tower, enrolled at the Académie Julien, and switched her focus from design and illustration to painting. France also precipitated a shift in her attitude. Feeling self-confident and liberated for the first time, she adopted the plein air method of painting, taking her large canvases outdoors onto the streets of Paris and the hills of the French countryside. With the African American expatriate artist Albert Smith and the French painter Emile Bernard as mentors, she produced more than forty paintings in just nine months. Jones’s streetscapes, still lifes, portraits, and landscapes, typified by Rue St. Michel (1938) and Les Pommes Vertes (1938), illustrate a sophisticated interpretation of impressionist and post-impressionist style and sensibility.

African art and culture were all the rage during Jones’s visit to Paris. Sketching African masks on display in Parisian galleries prepared her for what would become her best-known work, Les Fétiches (1938), a cubist-inspired painting of African masks that foreshadowed Jones’s embrace of African themes and styles in her later work. In 1990, when the National Museum of American Art in Washington, D.C., acquired Les Fétiches, Jones responded: “I am very pleased but it is long overdue . . . . I can’t help but think this is an honor that is 45 years late” (Washington Post, 7 Oct. 1994).

Even while the Robert Vose Gallery in Boston exhibited her Parisian paintings shortly after her return to the United States, Jones longed for the racial tolerance she had experienced in France. When she met Alain Locke upon her return to Howard, he challenged her to concentrate on African American subjects. And so began what Jones later called her Locke period. Throughout the 1940s and early 1950s she continued to paint in a semi-impressionist style but increasingly depicted African American subjects, as in the character studies Jennie (1943), a portrait of a black girl cleaning fish; Mob Victim (1944), a study of a man about to be lynched; and The Pink Tablecloth (1944).

Jones began exhibiting more extensively, primarily in African American venues such as the Chicago Negro Exposition of 1940 and the black-owned Barnett Aden Gallery, although traditionally white venues also included her work. On occasion, Jones masked her race by entering competitions by mail or by sending her white friend Celine Tabary to deliver her work. Such was the case in 1941 when her painting Indian Shops, Gay Head (1940) won the Corcoran Gallery’s Robert Wood Bliss Award. It was several years before the Corcoran knew that the painting was the product of a black artist.

In 1953 Jones married Louis Vergniaud Pierre-Noël, a Haitian artist she had met at Columbia University summer school in 1934. The couple, who had no children, maintained homes in Washington, Martha’s Vineyard, and Port-au-Prince, Haiti, until Pierre-Noël’s death in 1982. Shortly after their wedding Jones taught briefly at Haiti’s Centre d’Art and the Foyer des Arts Plastiques. Haiti proved to be the next great influence on Jones’s work. “Going to Haiti changed my art, changed my feelings, changed me” (Callaloo, Spring 1989). Character studies and renderings of the picturesque elements of island life soon gave way to more expressive works that fused abstraction and decorative elements with naturalism. Drawing on the palette and the diverse religious life and culture of Haiti, Jones incorporated voodoo gods, abstract decorative patterns, bright colors, and African elements into her paintings. Throughout the 1950s and 1960s she used strong color and flat, abstract shapes in a diverse range of works, including Bazar du Quai (1961), VeVe Voodou III (1963), and Paris Rooftops (1965).

In 1970–1971 Jones took a sabbatical from Howard and traveled through eleven countries in Africa, interviewing artists, photographing their work, and lecturing on African American artists. Jones, who had spent the previous summer interviewing contemporary Haitian artists, used these materials to complete her documentary project “The Black Visual Arts.” The bold, graphic beauty of African textiles, leatherwork, and masks resonated with her early fabric designs and provided a new vocabulary for her work, which now included collage as well as painting and watercolor. Once again, Jones visited museums and sketched African masks and fetishes, items increasingly significant in pieces like Moon Masque (1971) and Guli Mask (1972).

Throughout the 1970s and 1980s, inspired by Haiti and Africa and by the Black Arts Movement in the United States, Jones’s work centered on African themes and styles.

Jones, who finally returned to Boston’s Museum of Fine Arts in 1973 for a retrospective exhibition, had more than fifty solo shows. She received numerous awards and honorary degrees, including citations from the Haitian government in 1955 and from U.S. President Jimmy Carter in 1980. In 1988 Jones’s artistic life came full circle when she opened the Lois Mailou Jones Studio Gallery in Edgartown, Massachusetts, on Martha’s Vineyard. At age eighty-four Jones assessed the key influences on her work: “So now . . . in the sixtieth year of my career, I can look back on my work and be inspired by France, Haiti, Africa, the Black experience, and Martha’s Vineyard (where it all began) and admit: There is no end to creative expression” (Callaloo, Spring 1989). Lois Mailou Jones died at age ninety-two at her home in Washington, D.C.

Jones, Lois Mailou. Lois Mailou Jones: Peintures 1937–1951 (1952).

Benjamin, Tritobia Hayes. The Life and Art of Lois Mailou Jones (1994).

Howard University Gallery of Art. Lois Mailou Jones: Retrospective Exhibition Forty Years of Painting, 1932–72 (1972).

National Center of Afro-American Artists and Museum of Fine Arts, Boston. Reflective Moments: Lois Mailou Jones Retrospective 1930–1972 (1973).

Obituaries: Journal of Blacks in Higher Education, Summer 1998; Washington Post, 12 June 1998.

—LISA E. RIVO

JONES, MADAME SISSIERETTA JOYNER

JONES, MADAME SISSIERETTA JOYNER(5 Jan. 1869–24 June 1933), classical prima donna and musical comedy performer, was born Matilda Sissieretta Joyner in Portsmouth, Virginia, less than four years after the abolition of slavery. Jones was the only surviving child of Jeremiah Malachi Joyner, an ex-slave and pastor of the Afro-Methodist Church in Portsmouth, and Henrietta B. Joyner, a singer in the church choir. Thus, she was exposed to music during her formative years. When she was six years old her family moved to Rhode Island where Sissieretta began singing in the church choir, which her father directed. Her school classmates were mesmerized by her sweet, melodic, soprano voice and nicknamed her “Sissy.”

She began studying voice as a teenager at the prestigious Providence Academy of Music with Ada, Baroness Lacombe, an Italian prima donna. Not long afterwards, in 1883, when she was only fourteen, Sissieretta met and married David Richard Jones, a newspaperman who also served as her manager during her early years on stage. She also received more vocal training at both the New England Conservatory and the Boston Conservatory. After her first concert performance with the Academy of Music on 8 May 1888, the New York Age reported that Jones’s “voice is sweet, sympathetic and clear, and her enunciation a positive charm. She was recalled after each number” (The Black Perspective in Music, 192). In an attempt to make her more palatable to white audiences, David Jones, who was himself of a mixed race background, took his wife to Europe to have her skin lightened and to have some of her features altered.

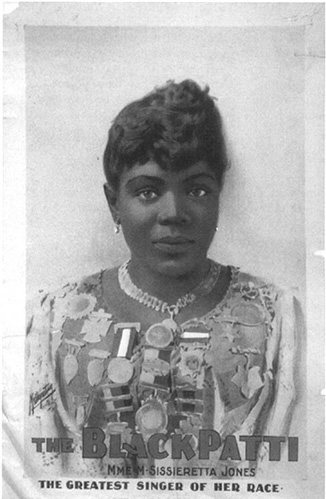

Lauded in Europe and America, but barred from singing at the Metropolitan Opera in New York because of her race, Madame Sissieretta Jones became the star of her own musical comedy troupe. Library of Congress

Jones made her New York City debut in a private concert at the Wallack Theatre on 1 August 1888. She was already being compared to the Italian prima donna Adelina Patti, who was adored by audiences throughout the world. As a result, Jones was dubbed “Black Patti.” She wanted her own identity but was forced to accept the nickname, which remained with her throughout her more than thirty-year career (Daughtry, 133).

In the early 1890s discussions ensued about possible appearances by Jones at the New York City Metropolitan Opera. She wanted very much to sing in a full-length opera at the Met. In the meantime, in 1891, she set out on a tour of the West Indies, where she was honored with numerous medals for her dynamic voice. After she returned to the United States, Jones appeared at Madison Square Garden in New York City in what was billed as an African Jubilee Spectacle and Cakewalk. Thousands listened to Jones, who was fluent in both Italian and French, sing selections from grand operas like Meyerbeer’s Robert le Diable as well as her popular signature piece, “Swanee River.” By 1892 she had already appeared at the White House three times as well as before European royalty. After performances at the Pittsburgh Exposition in 1893 and 1894, Jones became the highest paid black performer of her day.

Jones emerged as a celebrity and wanted to control her career. However, when she made this groundbreaking attempt in 1892, her manager, Major Pond, took her to court. There the judge ruled that she was ungrateful because she failed to appreciate how Pond was largely responsible for her accomplishments on the concert stage.

In New York City, Jones joined famed Czech composer Antonin Dvorak and his students from the National Conservatory of Music for a benefit concert in 1894. A New York Herald reporter said of the January concert, “Mme. Jones was an enormous success with the audience. To those who heard her for the first time she came in the light of a revelation, singing high C’s with as little apparent effort as her namesake, the white Patti” (The Black Perspective in Music, 199). Both the white and the black press continued to laud her as the “greatest singer of her race.” Nevertheless, the opportunity to sing at the Metropolitan Opera was still denied to Jones because of her ethnicity. These racist restrictions inspired her to leave the concert stage behind.

At the turn of the century, black musical comedies, which were first called coon shows, drew huge crowds into the theaters. Black female performers entered musical theater around 1885. During the height of popularity for musical comedies, managers were in control and dictated what performers would do. Managers Rudolph Voelckel and John J. Nolan, who are often credited along with David Jones for luring “Black Patti” to musical theater, planned to make the former concert stage prima donna the star of her own musical black touring company.

On 26 September 1896 Black Patti’s Troubadours made their debut in a mini-musical called “At Jolly Coon-ey Island: A Merry Musical Farce,” cowritten by Bob Cole and William Johnson. “At Jolly Coon-ey Island” contained almost no plot. Rather, it was a revue that included classical music, vaudeville, burlesque, and skits performed by an enormous group of fifty dancers, singers, tumblers, and comedians. Black Patti’s Troubadours were unique. Unlike other black companies, the Troubadours omitted the cakewalk, a popular, high-stepping dance, from their finale. Instead, an operatic kaleidoscope featuring Black Patti concluded the show. The Troubadours placed the spotlight on Black Patti, who stylishly appeared in tiaras, long satin gowns, and white gloves to perform selections from the operatic composers Balfe, Verdi, Wagner, and Gounod.

Black Patti’s Troubadours, billed as the “greatest colored show on earth,” was based in New York City but toured throughout the United States and abroad. Advertisements claimed the group traveled thousands of miles in the United States in a train car called “Black Patti, America’s Finest Show Car.” Jones was the central attraction in productions like A Ragtime Frolic at Rasbury Park (1899–1900) and A Darktown Frolic at the Rialto (1900–1901). Although it is unclear how much of Jones’s actual earnings went to Voelckel and Nolan, two years after the establishment of Black Patti’s Troubadours, The Colored American reported that Jones commanded a salary of five hundred dollars per week. However, her husband was allegedly a gambler. His gambling, drinking, and misuse of their money led to the couple’s divorce in 1899.

By 1900 Black Patti’s Troubadours was solidly recognized as one of the most popular companies on the American stage. It helped to launch the careers of women like Ida Forsyne, Aida Overton Walker, and Stella Wiley. Many black performers, who began their careers with Black Patti, went on to experience success on their own. One might argue that their association with Jones, a highly respected, even revered performer, contributed to their later success.

As America’s tastes began to change, the Troubadours adopted the name Black Patti Musical Comedy Company. Blacks began to view black musical comedies as negative depictions of their race, while whites began to turn their attention to other forms of entertainment. Some of the troupe’s later productions were set in an African jungle. Jones played the queen in a 1907 production called Trip to Africa. She was included in the action of the comedy in a skit called “In the Jungles” for the first time in 1911. From 1914 to 1915 the operatic kaleidoscope no longer appeared in the Troubadours’ program.

Jones made her final performance at New York City’s Lafayette Theater in 1915. As the mother of two adopted sons, she moved back to Providence, Rhode Island, where she also cared for her ailing mother. When Jones became ill and fell into obscurity, she was forced to rely on assistance from the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP). Sissieretta Jones died on 24 June 1933 at Rhode Island Hospital. She remains one of the most celebrated black performers of the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries.

A press scrapbook on Jones is housed in the Moorland-Spingarn Collection, Howard University, Washington, D.C.

The Black Perspective in Music 4, no. 2 (July 1976).

Daughtry, Willia Estelle. “Sissieretta Jones: A Study of the Negro’s Contribution to Nineteenth Century American Concert and Theatrical Life.” PhD diss., Syracuse University, 1968.

Henricksen, Henry. “Madame Sissieretta Jones.” Record Research, no. 165–166 (Aug. 1979).

Woll, Allen. Black Musical Theatre: From Coontown to Dreamgirls (1989).

—MARTA J. EFFINGER-CRICHLOW

JONES, QUINCY

JONES, QUINCY(14 Mar. 1933–), jazz musician, composer, and record, television, and film producer, was born Quincy Delight Jones Jr. on the South Side of Chicago, Illinois, the son of Sarah (maiden name unknown) and Quincy Jones Sr., a carpenter who worked for a black gangster ring that ran the Chicago ghetto. When Quincy Sr.’s mentally ill wife was institutionalized, he sent their sons, Quincy Jr. and Lloyd, to live in the South with their grandmother. In his autobiography Jones writes of growing up so poor that his grandmother served them fried rats to eat. By the age of ten he was living with Lloyd and their father in Seattle, Washington. “My stepbrother, my brother, and myself, and my cousin . . . we burned down stores, we stole, whatever you had to do,” Jones said (CNN Online, “Q and A: A Talk with Quincy Jones,” 11 Dec. 2001).

Modern jazz was Jones’s way out. Inspired by the now legendary jazzmen who passed through Seattle in the 1940s, Jones began studying trumpet in junior high school. When COUNT BASIE brought a group to Seattle in 1950, Jones, then a teenager, approached one band member, Clark Terry, an acclaimed trumpeter, for lessons. “He’s the type of cat, anything he wanted to do, he could’ve done,” Terry said later in his autobiography.

Jones showed enough musical promise to win a scholarship to Schillinger House in Boston (now the Berklee School of Music), but he dropped out after a year to accept a place in the trumpet section of Lionel Hampton’s band. In 1951, Hampton made a record of Jones’s “Kingfish” and gave the teenager his first recorded composition. Thereafter, Jones settled in New York City, where he found work as an arranger for some of the biggest stars in jazz, including Count Basie, Cannonball Adderley, and Dinah Washington. In 1956 he hired an array of top musicians for his first album, This Is How I Feel about Jazz. “His writing is not exploratory,” writes jazz critic Leonard Feather. He wrote in his New Encyclopedia of Jazz about Jones’s musical compositions, “Unlike many of the younger writers who have experimented with atonality and extended forms, he has remained within the classic jazz framework; his reputation rests mainly on brief compositions that combine the swinging big band feel of the better orchestras of the ’30s with the harmonic developments of the ’40s.”

In May 1956 Jones joined the DIZZY GILLESPIE orchestra on a State Department-sponsored tour of the Middle East and South America. A year later he moved to Paris, where he studied with Nadia Boulanger, a conductor and composition teacher known for her illustrious expatriate pupils, including Aaron Copland and Virgil Thomson. Modern jazz was blossoming in Paris, and Jones became a producer-arranger for Disques Barclay, France’s premier jazz label. In the fall of 1959 he became musical director of Free and Easy, a touring blues opera by Harold Arlen. Jones had assembled a big band for the show, and in September 1959 he took it on a European tour. The enterprise proved much too costly, and in 1960 it fell apart, leaving Jones deeply in debt.

Returning to New York, Jones was hired in May 1961 as an A&R (“Artist and Repertory”) man at Mercury Records. After producing a number-one hit—Lesley Gore’s teenage pop lament “It’s My Party”—and other artistic and creative successes, he became vice president of the company in November 1964. It was reportedly the first time a black man had held such a high position in the U.S. record business. In addition to arranging and conducting for Frank Sinatra, Basie, SARAH VAUGHAN, and Peggy Lee, Jones was writing and recording his own albums.

Beginning with Sidney Lumet’s Pawnbroker in 1964, Jones began composing film music, collaborating with many of the decade’s seminal filmmakers, including Lumet, Sidney Pollack, Norman Jewison, Richard Brooks, and Paul Mazursky. He also teamed with the actor SIDNEY POITIER for six films during the 1960s and early 1970s. Jones’s scores for such films as The Pawnbroker, In Cold Blood (1967), In the Heat of the Night (1967), Cactus Flower (1969), and Bob & Carol & Ted & Alice (1969) introduced jazz, soul, and, later, funk into films, contributing to the increased sophistication and interrelatedness of music to popular film. Jones also played a part in bringing a new sound to TV with his scores for Ironside (1967–1975); The Bill Cosby Show (1969); Sanford and Son (1972–1977), starring REDD FOXX; and the miniseries Roots (1977), based on the book by ALEX HALEY and for which Jones won an Emmy.

Jones’s affairs with a string of women, including Dinah Washington and Peggy Lee, had put a severe strain on his marriage to Jeri Caldwell, his white high-school sweetheart and the mother of his first child, Jolie. Married in 1957, the couple divorced nine years later. Jones quickly entered into a brief marriage with Ulla Andersson, a blonde model. In 1974 he married Peggy Lipton, star of TV’s Mod Squad. The couple had two children and divorced in 1989.

In 1969 Jones moved to A&M, by which time he had made a nearly full-time shift toward commercial pop. The trumpeter MILES DAVIS had plunged into fusion, a new style of electric jazz-rock and Jones did the same in Walking in Space (1974), his first of several hit records that combined jazz, fusion, and funk. Jones continued his work as orchestrator, arranging the strings for Paul Simon’s foray into pop-gospel and rhythm and blues, There Goes Rhymin’ Simon (1973). But Jones remained loyal to the jazz musicians he loved and filled his orchestras with them. In 1973 he began a career in TV production with a gala special on the CBS network called DUKE ELLINGTON . . . WE LOVE YOU MADLY, featuring a cast that included Vaughan, Lee, Joe Williams, and Jones’s boyhood friend RAY CHARLES, along with newer stars like Roberta Flack and ARETHA FRANKLIN.

Jones, who had worked on behalf of MARTIN LUTHER KING JR.’s Operation Breadbasket, helped organize Chicago’s Black EXPO, an offshoot of Operation PUSH, with JESSE JACKSON in 1972. He later served on the board of PUSH and, much later, produced a talk show with Jackson, The Jesse Jackson Show (1990). Jones, who had begun seriously educating himself about black and African music, became increasingly committed to the historical preservation of African American music. He helped establish the annual Black Arts Festival in Chicago and the Institute for Black American Music, which donated funds toward the establishment of a national library of African American art and music.

Jones’s workaholic tendencies caught up with him in August 1974 when he suffered a near fatal brain aneurysm and underwent two major neurological surgeries. Once recovered, he returned to his career with the same fervor. In 1979 he produced MICHAEL JACKSON’s solo album Off the Wall, which yielded four top-ten hits. In 1981 Jones left A&M and established the Qwest label at Warner Bros. Although he made his initial mark as a jazz arranger, producer, and bandleader, Jones became a household name by producing Jackson’s next album, 1982’s Thriller, which sold fifty million albums and became the biggest-selling album of all time. Jackson and Jones remained a team for years, working on Bad (1987) and other projects.

Apart from his work with Michael Jackson, Jones’s greatest commercial triumph came in 1985, with the slick all-star album USA for Africa, which featured the song “We Are the World.” Written by Jackson and Lionel Ritchie and performed by forty-six music stars, including Bruce Springsteen and DIANA Ross, the single sold seven and a half million copies, raised fifty million dollars for famine relief in Africa, and won Grammy Awards for Song of the Year and Record of the Year.

Jones showed his ingenuity for mixing pop with traditional genres with The Dude (1980), a pop-soul extravaganza with Jackson, STEVIE WONDER, Herbie Hancock, the jazz harmonica and guitar player Toots Thielemans, and two of Jones’s protégés, the singers Patti Austin and James Ingram. He continued this pattern in 1989 with Back on the Block, an album that mingled Miles Davis, Dizzy Gillespie, ELLA FITZGERALD, and Sarah Vaughan with the rappers Kool Moe Dee and Big Daddy Kane. “I’ll Be Good to You,” a top-twenty single from that album, paired Ray Charles with the pop-soul belter Chaka Khan.

After his successful turn in 1985 as coproducer of the Steven Spielberg film adaptation of ALICE WALKER’s The Color Purple, Jones expanded his empire into film and television production. Through Quincy Jones Entertainment, Inc. (QJE), a joint enterprise with Time Warner formed in 1990, Jones created The Fresh Prince of Bel Air (1990–1996), the TV series that launched actor Will Smith, and the long-running comedy show Mad TV. Jones’s other producing projects include the multipart History of Rock and Roll (1995) and the 2002 documentary TUPAC SHAKUR: Thug Angel. The founder of Quincy Jones Music Publishing, Jones also owns Qwest Broadcasting, which, with the Tribune Company, owns television stations in Atlanta and New Orleans. In 1990 Jones established a magazine, Vibe, which focused on black pop music. The next year he persuaded the ailing Miles Davis to revisit classic work of the 1950s in a concert at the Montreux Jazz Festival in Switzerland. Davis hated looking back; only Jones could persuade him to do so. Davis died two months later.

The recipient of countless awards, Jones has earned seventy-seven Grammy nominations and won twenty-six times. He is a six-time Oscar nominee, and at the 1995 Academy Awards he won the Jean Hersholt Humanitarian Award. In 1990 Warner Bros, released a documentary based on his life, Listen Up: The Lives of Quincy Jones. Eleven years later he received a Kennedy Center Honor for lifetime achievement. As awards showered down on him in the 1980s and 1990s, some critics thought Jones outrageously overhyped. There is little disagreement, however, about his abilities in combining talent in the studio to dazzling effect. Throughout his career he showed a shrewd business sense, earning millions of dollars, riding almost every new musical trend, including fusion and rap. While he will not be remembered as an exceptional trumpeter, Jones remains one of the most celebrated and charismatic figures in the pop music business. He has also allied himself with the biggest names in jazz, pop, and film to a point where he has been absorbed into their ranks.

Jones, Quincy. Q: The Autobiography of Quincy Jones (2001).

Ross, Courtney, and Nelson George. Listen Up: The Lives of Quincy Jones (1990).

—JAMES GAVIN

JONES, SCIPIO AFRICANUS

JONES, SCIPIO AFRICANUS(1863–28 Mar. 1943), lawyer, was born in Dallas County, Arkansas, the son of a white father, whose identity remains uncertain, and Jemmima, a slave who belonged to Dr. Sanford Reamey, a physician and landowner. After emancipation, Jemmima and her freedman husband, Horace, became farmers and adopted the surname of Jones, in memory of Dr. Adolphus Jones, a previous owner. Scipio Jones attended rural black schools in Tulip, Arkansas, and moved to Little Rock in 1881 to pursue a college preparatory course at Bethel University. He then entered Shorter College, from which he graduated in 1885 with a bachelor’s degree in Education. When the University of Arkansas Law School denied him admission because of his race, he read law with several white attorneys in Little Rock and was admitted to the bar in 1889. His marriage to Carrie Edwards in 1896 ended in his wife’s early death and left him with a daughter to raise. In 1917 he married Lillie M. Jackson of Pine Bluff, Arkansas.

By the turn of the century Jones had become the leading black practitioner in Little Rock. His clients, who were drawn exclusively from the African American community, included several large, fraternal organizations, such as the Mosaic Templars of America. He also played an active role in Republican politics, supporting the efforts of the “Black and Tan” faction to wrest control of the state party from the “Lily Whites.” In 1902 he promoted a slate of black Republicans to challenge the party regulars and the Democrats in a local election, and in 1920 he made an unsuccessful bid for the post of Republican national committeeman. The struggle to secure equal treatment for African Americans within the party lasted from the late 1880s to the 1930s and resulted in a compromise that guaranteed black representation on the Republican state central committee. As a sign of changing times, Jones was elected as a delegate to the Republican National Conventions of 1928 and 1940. Despite the existence of poll taxes that disfranchised most black voters, he also won election as a special judge of the Little Rock municipal court in 1915, at a time when few African Americans held judicial office anywhere in the country.

Jones’s lifelong commitment to protecting the civil rights of blacks led to his involvement in the greatest legal battle of his career: the defense of twelve tenant farmers who were sentenced to death for alleged murders committed during the bloody Elaine, Arkansas, race riot of October 1919. The violence grew out of black efforts to establish a farmers’ union and white fears that a dangerous conspiracy was being plotted at their secret meetings. When two white men were reportedly shot near a black church, the white community engaged in murderous reprisals that left more than two hundred blacks and five whites dead. An all-white grand jury quickly indicted 122 blacks, and because most of the defendants were indigent, the court appointed defense counsel for them. These white lawyers did not interview their clients, request a change of venue, or object to all-white trial juries. The trials themselves lasted less than an hour, and it took juries only five or six minutes to return guilty verdicts. Several defendants and witnesses later claimed that they had been tortured, and an angry white mob surrounded the courthouse during the trials. Besides the twelve men who were sentenced to death, sixty-seven others received long prison terms.

The National Association for the Advancement of Colored People retained Jones and George W. Murphy, a white Little Rock attorney, to appeal the convictions. Jones became the senior defense counsel after Murphy died in October 1920, and he tirelessly pursued every avenue of relief under state law, risking his life on several occasions by his courtroom appearances in the hostile community of Helena. Jones’s arguments impressed the Arkansas Supreme Court, which twice ordered new trials for six defendants. In the first instance Jones pointed to technical defects in the form of the verdicts. On the second appeal he contended that the trial judge’s rejection of evidence pointing to racial discrimination in the selection of jurors had deprived his clients of their equal protection rights under the Fourteenth Amendment. To prevent the impending executions of the remaining six defendants, Jones turned to the federal courts. Arguing that the prisoners had been deprived of their constitutional right to a fair trial, he sought their release through a habeas corpus proceeding. Eventually the case reached the U.S. Supreme Court, where it resulted in a landmark decision, Moore v. Dempsey (1923). By looking behind the formal state record for the first time, the Court overturned the convictions and held that the defendants had been denied due process, since their original trial had been little more than a legalized lynching bee. Although Jones did not participate in the final argument of the case, his strategy had guided the litigation process from the beginning. In the aftermath of Moore v. Dempsey, he secured an order from the Arkansas Supreme Court for the discharge of six prisoners in June 1923. He then negotiated with state authorities to secure commutation of sentences and parole for all of the remaining Elaine “rioters” by January 1925.

In his later years Jones continued to attack racially discriminatory laws and practices in Arkansas. He was instrumental in obtaining legislation that granted out-of-state tuition payments to black students who could not enter the state’s all-white professional schools. He died in Little Rock. To commemorate his community leadership, the all-white school board of North Little Rock named the black high school in his memory.

Letters from Jones are in the NAACP Papers in the Library of Congress and in the Republican Party State Central Committee Records in the University of Arkansas Library.

Cortner, Richard C. A Mob Intent on Death (1988).

Dillard, Tom. “Scipio A. Jones.” Arkansas Historical Quarterly 31 (Autumn 1972): 201–219.

Ovington, Mary White. Portraits in Color (1927).

Waskow, Arthur I. From Race Riot to Sit-In, 1919 and the 1960s (1966).

—MAXWELL BLOOMFIELD

JOPLIN, SCOTT

JOPLIN, SCOTT(24 Nov. 1868?–1 Apr. 1917), ragtime composer and pianist, was born in or near Texarkana, Texas, one of six children of Giles Joplin, reportedly a former slave from North Carolina, and Florence Givens, a free woman from Kentucky. Many aspects of Joplin’s early life are shrouded in mystery. At a crucial time in his youth, Scott’s father left the family, and Florence was forced to raise him as a single parent. She made arrangements for her son to receive piano lessons in exchange for her domestic services, and he was allowed to practice piano where she worked. A precocious child whose talent was noticed by the time he was seven years old, Scott had undoubtedly inherited talent from his parents, as Giles had played violin and Florence sang and played the banjo. His own experimentations at the piano and his basic music training with local teachers contributed to his advancement. Scott attended Orr Elementary School in Texarkana and then traveled to Sedalia, Missouri, perhaps residing with relatives while studying at Lincoln High School.

Joplin built an early reputation as a pianist and gained fame as a composer of piano ragtime during the Gay Nineties, plying his trade concurrently with composers such as WILL MARION COOK and HARRY BURLEIGH. Joplin was essential in the articulation of a distinctly American style of music. Minstrelsy was still in vogue when Joplin was a teenager performing in vaudeville shows with the Texas Medley Quartette, a group he founded with his brothers. Joplin reportedly arrived in St. Louis by 1885, landing a job as a pianist at John Turpin’s Silver Dollar Saloon. In 1894 he was hired at Tom Turpin’s Rosebud Cafe. As musicians flocked to the Chicago Columbian Exposition in 1893, Joplin was among them, playing at nightspots close to the fair. Afterward, he returned to Sedalia, the “Cradle of Ragtime,” accompanied by the pianist Otis Saunders.

Scott Joplin, “The King of Ragtime,” c. 1911. Schomburg Center

Although he was playing piano in various cities, Joplin still found time to blow the cornet in Sedalia’s Queen City Band. In 1895 he continued playing with the Quartette and toured as far as Syracuse, New York, where some businessmen were sufficiently impressed with his talents to publish his first vocal songs. Additionally, Joplin was hired as a pianist at Sedalia’s famous Maple Leaf Club. He also taught piano, banjo, and mandolin, claiming among his students the pianists Arthur Marshall, Scott Hayden, and Sanford B. Campbell. By 1896 Joplin had settled in Sedalia and matriculated at the George Smith College for Negroes. With the confidence and ambition fostered by this formal training, he approached the Fuller-Smith and Carl Hoffman Companies, which published some of his piano rags. It was also in Sedalia that he met John Stark, who became his friend and the publisher of Joplin’s celebrated “Maple Leaf Rag” (1899).

In 1900 Joplin began a three year relationship with Belle Hayden, which produced a child who soon died. He then married Freddie Alexander in 1904, but her death that same year sent him wandering about for at least a year, returning at times to Sedalia and St. Louis. In 1905 he went to Chicago, and by 1907 he had followed John Stark to New York and married Lottie Stokes, who remained with him until his death. In the years after the turn of the century, the piano replaced the violin in popularity. Playing ragtime on the parlor piano became “all the rage” in both the United States and Europe. Although there were ragtime bands and ragtime songs, classic rag soon became defined as an instrumental form, especially for the piano. Many Joplin rags consist of a left-hand part that jumps registers in eighth-note rhythms set against tricky syncopated sixteenths in the right hand. Joplin was both prolific and successful in writing rags for the piano, and he came to be billed as “the King of Ragtime.”

Ragtime or Rag—from “ragged time”—is a genre that blends elements from marches, jigs, quadrilles, and bamboulas with blues, spirituals, minstrel ballads, and “coon songs.” (“Coon songs” were highly stereotyped comic songs, popular from the 1880s to the 1920s, written in a pseudo-dialect purporting to record African-American vernacular speech.) Ragtime is an infectious and stimulating music, usually in 2/4 meter, with a marchlike sway and a proud, sharp, in-your-face joviality. Its defining rhythm, based on the African bamboula dance pattern, renamed “cakewalk” in America, is a three-note figuration of sixteenth-eighth-sixteenth notes, which is also heard in earlier spirituals, such as “I Got a Home in-a That Kingdom” and “Ain-a That Good News!”

A predecessor of jazz, ragtime was correlated with the “African jig” because of its foot stamps, shuffles, and shouts, “where hands clap out intricate and varying rhythmic patterns. . . and the foot is not marking straight time, but what Negroes call ‘stop time,’ or what the books call ‘syncopation’” (JAMES WELDON JOHNSON, The Book of American Spirituals [1925], 31). Joplin alludes to these influences in his “Stoptime Rag,” where the word “stamp” is marked on every quarter beat. Joplin admonished pianists to play ragtime slowly, even though his tempo for “Stoptime” is marked “Fast or slow.” Campbell most revealingly wrote that rag was played variously in “march time, fast ragtime, slow, and the ragtime blues style” (Fisk University, Special Collections).

Vera Brodsky Lawrence’s Complete Works of Scott Joplin lists forty-five rags, waltzes, marches, and other piano pieces that Joplin composed himself. In addition, he collaborated on a number of rags, including “Swipesy” with Arthur Marshall, “Sunflower Slow Drag,” “Something Doing,” “Felicity Rag,” “Kismet Rag” with Scott Hayden, and “Heliotrope Bouquet” with Louis Chauvin. There are also various unpublished pieces and some that were stolen, lost, sold, or destroyed.

The most popular of Joplin’s works, and one that brought continuous acclaim, is undoubtedly the “Maple Leaf Rag.” No matter the studied care of “Gladiolus Rag” or the majesty of “Magnetic Rag,” with its blue-note features, and no matter the catchiness of “The Entertainer,” “Maple Leaf’ beckons more. Over and above its engaging melodies and syncopations, the technical challenges alone are more than enough to induce an ambitious pianist to tackle “Maple Leaf.” Whatever its ingredients, “Maple Leaf Rag” garnered a respect for ragtime that has lasted for decades. Numerous musicians have recorded it, and it has been arranged for instruments from guitar to oboe and for band and orchestra.

Joplin also composed small and large vocal forms, both original and arranged. A few of his nonsyncopated songs are related to the Tin Pan Alley types of the day, and at least two are influenced by “coon songs.” He choreographed dance steps and wrote words for the “Ragtime Dance Song,” and in a few cases he either wrote lyrics or arranged music for others. Joplin composed two operas, the first of which is lost. The second, Treemonisha, whose libretto Joplin also wrote, is an ambitious work containing twenty-seven numbers, and requiring three sopranos, three tenors, one high baritone, four basses, and a chorus. Set “on a plantation somewhere in the State of Arkansas, Northeast of the Town of Texarkana and three or four miles from the Red River,” the opera presents education as the key to success.

Throughout Joplin’s preface to Treemonisha, one cannot help but note the parallelism of dates and geographic locations in the opera to those of his own past. The preface tells the tale of a young baby who was found under a tree, adopted, and named “Treemonisha” by Ned and Monisha. At age seven, she is educated by a white family in return for Monisha’s domestic services. The opera opens with eighteen-year-old Treemonisha touting the value of education and campaigning against two conjurers who earn their livelihoods promoting superstition. After various episodes with kidnappers, wasps, bears, and cotton pickers, who sing the brilliant “Aunt Dinah Has Blowed de Horn,” Treemonisha is successful and joins the finale, singing “Marching Onward” to the tune of the “Real Slow Drag.”

Compositionally, syncopated music is used in Treemonisha only when the plot calls for it, with the musical themes and harmonies employing “crossover” alternations between classical and popular styles. However, Joplin’s intentions seem to have leaned more toward the classical. The basic harmonies are decorated with his favored diminished seventh chords and secondary dominants. Altered chords, chromatics, modulations, themes with mode changes, special effects to depict confusion, and even an example of seven key changes in “The Bag of Luck” all point toward Joplin’s training and musical aspirations.

Joplin accompanied the first performance of Treemonisha on the piano. When he sought sponsors, and when he asked Stark to publish the opera, he was refused. Tackling these jobs himself proved to be his undoing. As a result of stress and illness, Joplin lost his mental balance in early 1917 and was admitted to the New York State Hospital. A diagnosis signed by Dr. Philip Smith states that Joplin succumbed to “dementia paralytica—cerebral form about 9:10 o’clock p.m.,” that the duration of the mental illness was one year and six months, and that the “contributory causes were Syphilis [of an] unknown duration” (Bureau of Records, New York City).

Campbell wrote that Joplin’s funeral carriage bore names of his rag hits. Sadly, only the New York Age and a notice by John Stark carried his obituary. High society from New York to Paris had strutted the cakewalk accompanied by his rags since the late 1890s, but now he was forgotten. Perhaps World War I diverted people’s attention away from the exuberance of raggedy rags and thus from Joplin. He received accolades for his piano rags, but his most difficult vocal music was not appreciated in his lifetime. Sixty years after his death he began to receive numerous honors, including the National Music Award, a Pulitzer Prize in 1976, and a U.S. postage stamp in 1983.

Several articles in the Washington Post and the New York Times inspired a revival of Joplin’s music in the 1970s. Various films, especially The Sting (1973), and television productions have highlighted his work, and concerts and recordings by the finest of musicians have taken the music to new heights. Additionally, there have been several productions of Treemonisha. To be sure, rags were written before Joplin’s Original Rags was published in 1899, but he must be credited with defining the classic concept and construction of ragtime and with rendering dignity and respectability to the style.

Selected repositories of music and other materials are at the New York Public Library, the Library of Congress, Washington, D.C.; the Fisk University Library, Nashville, Tennessee; the Center for Black Music Research, Chicago, Illinois; Indiana University Library, Terre Haute; and the Scott Joplin International Ragtime Foundation, Sedalia, Missouri.

Berlin, Edward A. King of Ragtime: Scott Joplin and His Era (1994).

Jasen, David, and Trebor J. Tichenor. Rags and Ragtime: A Musical History (1989).

Lawrence, Vera Brodsky. The Complete Works of Scott Joplin (1981).

Preston, Katherine. Scott Joplin: Composer (1988).

Obituary: New York Age, 5 Apr. 1917.

Joplin, Scott. Classic Ragtime from Rare Piano Rolls (1989).

Rifkin, Joshua. Scott Joplin: Piano Rags (1987).

Zimmerman, Richard. Complete Works of Scott Joplin (1993).

—HILDRED ROACH

JORDAN, BARBARA

JORDAN, BARBARA(21 Feb. 1936–17 Jan. 1996), lawyer, politician, and professor, was born Barbara Charline Jordan in Houston, Texas, the daughter of Benjamin M. Jordan and Arlyne Patten Jordan. Her father, a graduate of the Tuskegee Institute, was a warehouse employee until 1949 when he became a minister at Houston’s Good Hope Missionary Baptist Church, in which his father’s family had long been active. Arlyne Jordan also became a frequent speaker at the church. The Jordans were always poor, and for many years Barbara and her two older sisters shared a bed, but their lives improved somewhat after their father became a minister. Barbara attended local segregated public schools and received good grades with little effort. She gave scant thought to her future, beyond forming a vague desire to become a pharmacist, until her senior year at Phillis Wheatley High School, when a black female lawyer spoke at the school’s career day assembly. Already a proficient orator who had won several competitions, she decided to put that skill to use as an attorney.

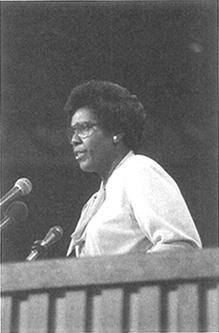

Representative Barbara Jordan addressing the Democratic National Convention, 1976. Library of Congress

Restricted in her choice of colleges by her poverty as well as segregation, Jordan entered Texas Southern University, an all-black institution in Houston, on a small scholarship in the fall of 1952. Majoring in political science and history, she also became a champion debater, leading the college team to several championships. She graduated magna cum laude in 1956 and went on to Boston University Law School, where she managed to excel despite rampant gender discrimination. Upon graduation she took the Massachusetts bar exam, intending to practice law in Boston, but ultimately decided to return to her parents’ home in Houston. She used the dining room as her office for several years before setting up a downtown office, and she also worked as an administrative assistant to a county judge until 1966.

Jordan’s first wholesale encounter with politics came during the 1960 national election campaign, when she became a volunteer for Democratic presidential candidate John F. Kennedy and his running mate, Texas senator Lyndon B. Johnson. She began at the Houston party headquarters by performing menial jobs but soon emerged as the head of a voting drive covering Houston’s predominantly black precincts. The Democratic victory that fall changed Jordan’s life in several ways: not only did it persuade her to enter politics; it also overturned her long-held sense that segregation was a way of life that had to be endured, and it convinced her that the lives of black people might be improved by political action.