KECKLY, ELIZABETH HOBBS

KECKLY, ELIZABETH HOBBS KECKLY, ELIZABETH HOBBS

KECKLY, ELIZABETH HOBBS(Feb. 1818–26 May 1907), slave, dressmaker, abolitionist, and White House memoirist, was born Elizabeth Hobbs in Dinwiddie County, Virginia, the daughter of Armistead Burwell, a white slaveholder, and his slave Agnes Hobbs. Agnes was the family nurse and seamstress. Her husband, George Pleasant Hobbs, the slave of another man, treated “Lizzy” as his own daughter, and it was not until some years later, after George had been forced to move west with his master, that Agnes told Lizzy the identity of her biological father. While her mother taught her sewing, the skill that would make her name and fortune, it was George Hobbs who first instilled in Lizzy a profound respect for learning. Ironically, it was Armistead Burwell, who repeatedly told Lizzy she would never be “worth her salt,” who probably sparked her ambition to succeed and prove him wrong.

As a young girl, Lizzy lived in the master’s house, where her earliest tasks were to mind the Burwell’s infant daughter, sweep the yard, pull up weeds, and collect eggs. Lizzy benefited from the better diet and clothing and the possibilities for self-improvement that were often afforded to house slaves. Most important, she was taught to read and write. These advantages, added to the relatively stable presence of her extended slave family, contributed to Lizzy’s proud bearing and strong sense of self. Nevertheless, living in the master’s house was also dangerous. When she was five years old, her mistress, enraged because she had accidentally tilted the baby out of its crib, had her beaten so severely that she never forgot it.

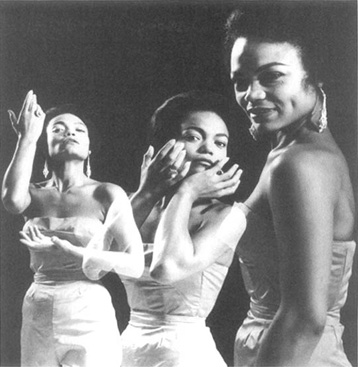

Elizabeth Keckly. University of North Carolina

At age fourteen, Lizzy was loaned to Armistead’s eldest son, Robert, and his new bride, Margaret Anna Robertson. The young Burwells took Lizzy to Hillsborough, North Carolina, where Robert was the minister of the Presbyterian Church and Anna opened a school for girls. Years later Lizzy would speak of her years in Hillsborough as the darkest period of her early life. When she was eighteen, Anna goaded a neighbor and her husband to “break” her with repeated beatings. At twenty Lizzy became the sexual prey of Alexander Kirkland, the married son of one of the town’s wealthiest slaveholders. For four years she endured a forced sexual relationship, until she gave birth to a son, George, and was sent back to the family in Virginia.

By this time Armistead Burwell had died, and Lizzy and her son rejoined her mother, becoming a slave in the household of Armistead’s daughter, Anne, and her husband, Hugh A. Garland. In 1847 Garland moved his household to St. Louis, where he opened a law office. (One of Garland’s clients was Irene Emerson, whose slaves, Harriet and DRED SCOTT, sued her for their freedom.) However, Garland could not make ends meet, and he decided to hire Lizzy out as a seamstress. It was a pivotal moment in Lizzy’s life. Being hired out enabled her to hone her skills as a dressmaker, and she soon earned the title of mantua maker for her ability to sew the complicated mantua, whose tight bodice was fitted with a series of tiny, vertical pleats in the back. But above all, sewing for hire gave her opportunities for autonomy that she could not have had working in the master’s house. Indeed, during this period Lizzy developed the network of white female clients who, in 1855, lent her money to allow her to pay the twelve-hundred-dollar purchase price for her freedom and that of her son. By this time Lizzy had married James Keckly, whom she had known as a free black Virginian; the marriage quickly soured once she discovered that he was not, in fact, free and that he drank. (Though the conventional spelling of her married name is Keckley, she herself spelled it Keckly.)

Lizzy Keckly remained in St. Louis until 1860, when she moved east alone, leaving James in St. Louis and enrolling George in Wilberforce University in Ohio. (Her mother had died in 1854.) She arrived in Washington, D.C., in the spring and quickly found work as a seamstress. Within months she had built an impressive list of clients, consisting of the wives of congressmen and army officers. During the secession winter of 1860–1861, Varina Davis, wife of the Mississippi senator Jefferson Davis asked her to move south with her, though Keckly refused.

On the day after President Abraham Lincoln’s first inauguration, in 1861, Elizabeth Keckly presented herself at the White House for an interview with Mary Todd Lincoln. One of her clients had recommended her to the new “Mrs. President” in return for a last-minute gown. Over the next few months Keckly made Mary Lincoln fifteen or sixteen new dresses, an enormous task and one that threw the women together for hours at a time for the elaborate fittings that were required. This collaboration was the beginning of a relationship that would deepen over time through the personal and public crises that beset the women. The first crisis they shared occurred in August 1861 when Keckly’s son, who had enlisted in the Union army as a white man, was killed in the Battle of Wilson’s Creek in Missouri.

A dignified, proud woman, Keckly also established herself as a notable figure in the middle-class black community in Washington. As one of the “colored” White House staff, Keckly was a member of an elite black society, along with the city’s leading caterers, barbers, restaurateurs, and government messengers. She boarded with the family of Walker Lewis, a respected messenger and later steward, who had also bought his way out of slavery. She also joined the black Union Bethel Church, second only in stature to the exclusive Fifteenth Street Presbyterian Church (which she joined in 1865). Meanwhile, her dressmaking business grew steadily; at its peak it employed twenty seamstresses.

By 1862 Keckly had become an intimate member of the Lincoln family, looking after the Lincolns’ two young sons, combing the president’s hair, and advising Mary Lincoln on matters of decorum as well as fashion. After the Lincolns’ twelve-year-old son, Willie, died of typhoid fever in February, the grief-stricken Mary Lincoln came to rely more heavily on the steadying presence of Lizzy Keckly.

During this period, Keckly was coming into her own not only as an entrepreneur but also as an activist. In April, after Congress emancipated slaves in the district, she was featured in a syndicated newspaper article about the success stories of recently freed slaves. That summer, she organized church members into the Contraband Relief Association to aid the “contrabands,” newly freed slaves who were pouring into Washington by the thousands. In the fall she made her first trip to the North, ostensibly as companion to Mary Lincoln and her youngest son, Tad, traveling to New York and Boston. But she spent much of her time raising funds with black abolitionists, including the Reverend HENRY HIGHLAND GARNET, the Reverend J. Sella Martin, and FREDERICK DOUGLASS, who raised money for her organization in England. She even solicited a donation from the president and Mrs. Lincoln.

Over the course of the four years she was an insider in the White House, Keckly became more comfortable wielding her influence. In 1864 she helped arrange for SOJOURNER TRUTH to meet with Abraham Lincoln in the White House. The Lincolns even visited the contraband camps, where Keckly worked. She was one of the Lincolns’ party when they entered Richmond after the Civil War ended.

In 1865, after Lincoln’s assassination, Keckly accompanied Mary Lincoln to Chicago and then returned to her business in Washington. In 1867, at Lincoln’s request, the two women met in New York City, where Keckly helped Lincoln arrange for a brokerage firm to auction off her old clothes to pay off her debts. Lincoln, who returned to Chicago while Keckly stayed in New York to manage Lincoln’s affairs, promised to pay her out of the proceeds of the sale. But the scheme was a disaster; the women lost money on the venture. During this period, with the help of the antislavery journalist James Red-path, Keckly wrote a memoir, devoting the last section to what the newspapers dubbed the “Old Clothes Scandal.” The 1868 publication of Keckly’s book, Behind the Scenes; or, Thirty Years a Slave, and Four Years in the White House, caused Mary Lincoln to break off their friendship.

Behind the Scenes is an invaluable source of information about the Lincolns’ private life in the White House. Whatever her motives for writing it, the memoir is unquestionably the expression of Keckly’s desire to leave her mark, yet after its publication her business gradually declined, and she turned primarily to teaching sewing. In 1890 she sold her Lincoln mementoes to a collector. For several years she headed Wilberforce University’s Department of Sewing and Domestic Science Arts, until she suffered a mild stroke. She died in Washington, D.C., in the National Home for Destitute Colored Women and Children, an institution founded during the war and partly funded by Keckly’s contraband association.

Keckley, Elizabeth. Behind the Scenes; or, Thirty Years a Slave, and Four Years in the White House (1868). Ed. Frances Smith Foster (2001).

Fleischner, Jennifer. Mrs. Lincoln and Mrs. Keckly: The Remarkable Story of the Friendship between a First Lady and a Former Slave (2003).

—JENNIFER FLEISCHNER

KEITH, DAMON JEROME

KEITH, DAMON JEROME(4 July 1922–), federal judge, was the youngest of six children born to Perry Keith, an automotive worker, and Annie Louise Williams. The family has its roots in Atlanta, Georgia, but Damon was born in Detroit, when his father took a job at the River Rouge Foundry of the Ford Motor Company. Keith has described his father as “the finest man in my life . . . the epitome of what a human being should be. He was my motivation and my desire to make something of myself.”

In 1943 Keith graduated from an historically black college, West Virginia State College. That same year he was drafted into the army and served during World War II in a segregated military, an experience that he later described as “absolutely demeaning.” After discharge from the military, Keith attended Howard University Law School, at a time when THURGOOD MARSHALL would practice before his Howard students the arguments he would later make in historic desegregation cases before the U.S. Supreme Court. Keith graduated from Howard Law School in 1949 and worked as a janitor while studying for the bar. Not long after he was admitted to practice in 1950, he married Rachel Boone, a physician from Liberia; they had three daughters, Gilda, Debbie, and Cecile. In 1956 Keith obtained a master of law degree from Wayne State University in Detroit.

During the early part of his career, Keith was politically active while he was in practice. Before his appointment to the bench, he was one of the named partners in the firm of Keith, Conyers, Anderson, Brown & Wallis in Detroit. He served on a number of different commissions, including the Detroit Housing Commission, the Civil Rights Commission of the Detroit Bar Association, and the Michigan Civil Rights Commission. Keith was appointed to the federal bench by President Lyndon B. Johnson in 1967 and was elevated to the Sixth Circuit Court of Appeals by President Jimmy Carter in 1977. Although he took senior status, still hearing cases but with a reduced workload, in 1995, Keith has continued to write judicial decisions that record and make history in the United States.

In United States v. Sinclair (1971), Keith addressed the abuse of power endemic in the administration of President Richard M. Nixon. Judge Keith’s ruling resulted from a criminal trial in which members of the radical leftist White Panther Party was accused of bombing the Ann Arbor, Michigan, offices of the CIA. During the trial it became clear that the federal government had tapped the phone lines of one of the White Panther defendants without obtaining a warrant beforehand. U. S. Attorney General John Mitchell justified the wiretapping on the basis of “national security,” but Judge Keith found that Mitchell had exceeded its powers. In particular, Keith rejected the Nixon administration’s argument that “a dissident domestic organization is akin to an unfriendly foreign power and must be dealt with in the same fashion.” Moreover, he added, the “Executive branch. . . cannot be given the power or the opportunity to investigate and prosecute criminal violations. . . simply because an accused espouses views which are inconsistent with our present form of Government.” Keith concluded that the powers over search and seizure claimed by the Nixon White House “was never contemplated by the framers of our Constitution and cannot be tolerated today.” The Supreme Court unanimously upheld Keith’s ruling in United States v. Sinclair, which came to be known in legal circles as “the Keith Decision.”

In 2002 Keith returned to the problem of abuses of power in the executive branch, this time by John Ashcroft, President George W. Bush’s attorney general. As in Sinclair, Keith argued in Detroit Free Press v. John Ashcroft that the executive branch had exceeded its powers. In the wake of the September 11, 2001, attacks on the United States, Attorney General Ashcroft had attempted to deport many Muslim non-citizens residing in the U.S. The Bush administration also attempted to prevent several Michigan newspapers and Congressman John Conyers from attending one of those deportation hearings, for a Muslim clergyman whose tourist visa had expired. Keith’s Sixth Circuit Court of Appeals opinion held that secret deportation hearings that are closed to family, friends, and the press are unconstitutional. Keith concluded by noting that “the Executive Branch seeks to uproot people’s lives, outside the public eye, and behind a closed door,” and warned that “Democracies die behind closed doors.”

Keith is one of a generation of black lawyers who experienced the era of de jure segregation, and used the Constitution to dismantle the systematic oppression of black people. In Davis v. School District of City of Pontiac (1970), a school desegregation case, he set for himself the task of deciding “what, if anything, now can be done to halt the furtherance of an abhorrent situation for which no one admits responsibility or wishes to accept the blame.” He concluded that the school district of Pontiac, Michigan, “deliberately, in contradiction of their announced policy of achieving a racial mixture in the schools, prevented integration,” and recommended busing as a remedy. In Davis, Keith then attacked the notion that what had occurred in Pontiac and all over the North was somehow different from legal segregation in the South. “Where a Board of Education has contributed and played a major role in the development and growth of a segregated situation, the Board is guilty of de jure segregation. The fact that it came slowly and surreptitiously rather than by legislative pronouncement makes the situation no less evil.”

This sensibility, the awareness of the pernicious effects of discrimination and the importance of giving voice to those who are harmed or injured by discrimination, is also revealed in his dissent in Rabidue v. Osceola Refining Company (1986). Keith is credited with introducing the “reasonable woman” standard in sexual discrimination cases. He has, in the words of one of his former law clerks “reached beyond the subjectivity of his own male experience” and “embraced. . . the struggle for gender equality.”

Keith has received innumerable awards and accolades from his colleagues on the bench and from the major civil rights organizations in the United States. He was given the NAACP Spingarn Medal in 1974, the Thurgood Marshall Award and the Spirit of Excellence Award from the American Bar Association, and the Edward J. Devitt Distinguished Service to Justice Award from the Detroit Urban League, among many others. Keith has been honored not just for the significance of his work as a judge. His dedication to the cause of promoting justice is not restricted to the written page and the decisions he has authored over the years. His appreciation of the importance of history is displayed in the Damon J. Keith Law Collection, an archive established at Wayne State University in 1993. This collection of photographs, documents, personal papers, memorabilia, and interviews documents the contributions of black lawyers and judges to the struggle for racial equality. Part of the collection is a traveling exhibit, Marching toward Justice.

When allegations of discrimination were leveled at a federal judiciary whose clerks were mostly white and predominantly male, Keith provided a model for the proponents of diversity. He employed more women and people of color than any other federal judge, and he chose as his clerks law graduates who practiced different religions and who came from different parts of the world. His former clerks include several law professors and the former attorney general and now governor of the state of Michigan, Jennifer Granholm. In Granholm’s words, “All of us are bound by our commitment to issues of justice and civil rights and we all feel a very sincere sense of loyalty to this man who has created a family that is so powerfully driven to change the world.”

Hale, Jeff A. “Wiretapping and National Security: Nixon, The Mitchell Doctrine, and the White Panthers,” Ph.D. diss., Lousiana State University (1995).

Littlejohn, Edward J. “Damon Jerome Keith: Lawyer-Judge-Humanitarian,” Wayne Law Review 42 (1996): 321–341.

—DEBORAH POST

KELLY, SHARON PRATT

KELLY, SHARON PRATT(30 Jan. 1944–), mayor of Washington, D.C., was born Sharon Pratt, the elder child of Carlisle Pratt, a superior court judge, and Mildred Petticord. When Sharon was four years old, her mother died of cancer. With her younger sister, Benaree, and their father, she went to live with her paternal grandmother and aunt. Some years later her father remarried, and Sharon lived with her father and stepmother. She attended Gage and Rudolph Elementary Schools and McFarland Junior High School and graduated from Roosevelt High School with honors. In 1965 she graduated from Howard University in Washington, D.C., with honors and a BA in Political Science; three years later she earned a JD from Howard’s law school. While in law school, she married her first husband, onetime D.C. council member Arrington Dixon, and they had two daughters, Aimee Arrington Dixon and Drew Arrington Dixon. The couple divorced in 1982.

Kelly began her legal career in 1970 as house counsel for the Joint Center for Political Studies in Washington, D.C., before entering private law practice with the legal firm of Pratt and Queen in 1971. From 1972 to 1976 she taught business law at the Antioch School of Law in Washington, D.C., reaching the rank of full professor. After leaving Antioch School of Law, she served as a member of the general counsel’s office at Potomac Electric Power Company (PEPCO) from 1976 to 1979, when the company appointed her director of consumer affairs. In 1986 PEPCO appointed her as its vice president for public policy. In that capacity she worked to develop programs to assist low- and fixed-income residents of the District of Columbia. Her early work in public service also included serving as vice chairman of the District of Columbia’s Law Revision Commission.

While representing Washington, D.C., on the Democratic National Committee from 1977 to 1990, Kelly was elected treasurer of the committee, serving from 1985 to 1989. Her close ties to the national Democratic Party furthered her local ambitions, and she launched her mayoral campaign with a lavish, well-attended party during the 1988 Democratic National Convention in Atlanta, Georgia. Defying the odds, on 6 November 1990, Kelly became the first woman elected mayor of Washington, D.C., with a landside 86 percent of the vote. She was also the first African American woman to serve as the chief executive of a major American city.

Commentators credited Kelly’s mayoral victory to her demonstrated commitment to the D.C. community over more than twenty years. With her positive campaign slogan of “Yes, We Will,” Kelly promised residents an “honest deal” that would restore the city to greatness by improving the quality of life for all of its people. She stunned observers when she promised to fire two thousand midlevel managers immediately, but many citizens were impressed with her eloquence and by the fact that she was an “outsider” with no apparent entanglements in local politics. Most important, she was not an ally of her predecessor as mayor, Marion S. Barry Jr.

In 1978 Barry had inherited a government that was already oversized and undermanaged. After nearly twelve years in office, having failed to tackle those problems and having been convicted of federal charges of cocaine possession, he chose not to run for reelection in 1990. Barry’s downfall produced an upsurge of support for reforming the district’s government, and Kelly, with her promise to “clean house” and her endorsement by the respected Washington Post, rode that political mood to easy victories in both the September Democratic primary and the November general election.

Solving the District of Columbia’s myriad problems would not be so easy. The bureaucracy was regarded by many as indifferent to the citizens it was supposed to serve. Like other urban areas, the District of Columbia had a multitude of problems, such as underfinanced, weak public schools; urban economic decay; high unemployment; drug trafficking; and homelessness. Even more disturbing was a financial crisis that had resulted in the city’s $300 million deficit at the end of the 1990 fiscal year. The U.S. Congress, as the city’s managers, appropriated $100 million in congressional emergency funding for the following fiscal year. Kelly argued that a comprehensive overhaul of city government was also needed.

At first Kelly seemed determined to downsize government and inaugurated programs aimed at restructuring the bureaucracy by automation and retraining. Every category of crime in the District of Columbia declined during her term as mayor. She developed public-private partnerships to facilitate many of her reforms. Area businesses were encouraged to use their ingenuity to help develop programs to serve all of the city’s citizens. These partnerships fostered more jobs and encouraged international trade ventures.

By all accounts, however, Kelly’s first year was traumatic. Her grandmother died, and a trusted friend and adviser tragically died when a city ambulance went to the wrong address. At the same time, James Kelly, a businessman from New York City whom she had married at the end of her first year, never seemed comfortable in the public spotlight or in playing the supporting role of First Spouse. Sharon Kelly was also never able to gain full control of a city still loyal to Barry and during Kelly’s second year in office, Barry backed an initiative to recall her from office. While the recall was unsuccessful, it forced Kelly to retreat from the tough reforms she had promised during her campaign. Kelly blamed Congress for Washington’s continuing financial problems and then further alienated Congress by providing it with inaccurate and false information about the city’s finances.

Kelly’s criticism of Congress for the city’s financial woes and her support for D.C. statehood alienated potential Democratic allies who controlled Congress. By 1993 she had also built a palatial office for herself outside the District Building, the usual location of district offices and agencies, and had put a makeup artist on the city payroll. Political observers increasingly saw such extravagance and her lack of political experience as a major problem, prompting some disillusioned voters to encourage Marion Barry’s comeback. After Barry had served six months in prison for his cocaine conviction in 1992, he was elected to the city council. In 1994 he defeated Kelly in that year’s mayoral election.

Kelly has received an NAACP Presidential Award, the THURGOOD MARSHALL Award of Excellence, and the MARY MCLEOD BETHUNE-W. E. B. Du BOIS Award from the Congressional Black Caucus. She has been honored for distinguished leadership by the United Negro College Fund and was the recipient of an award for distinguished service from the Federation of Women’s Clubs, whose mission is to improve communities through volunteer service. Although her time in office was not as stellar as she had hoped or predicted it would be, Sharon Kelly will be remembered as the first native of Washington, D.C., and the first African American woman to be elected mayor of a major American city.

Borger, Gloria. “People to Watch: Sharon Pratt Dixon,” U.S. News and World Report, 31 Dec. 1990.

French, Mary Ann. “Who Is Sharon Pratt Dixon?,” Essence (Apr. 1991).

McCraw, Vincent. “Anxious Dixon on Mission to Cure D.C.’s Ills,” Washington Times, 17 Apr. 1990.

—DEBORAH F. ATWATER

KING, B.B.

KING, B.B.(16 Sept. 1925–), blues singer and guitarist, was born Riley B. King near Itta Bena, Mississippi, to Albert King and Nora Ella Pully, sharecroppers who worked farms near Indianola. Riley was named after a white planter, O’Reilly, who helped his family when his mother was in labor. The “O” was dropped, his father said, “’cause you don’t look Irish” (King, 7). Later, King wanted to be called the Beale Street Blues Boy, but the world came to know him simply as B. B. King.

In 1930 Nora left Albert and the delta region of Mississippi, taking her five-year-old son to live near Kilmichael in the hill country. There she introduced him to the soulful spirituals of the Elkhorn Baptist Church and the moving testimonials of the Church of God in Christ, a Sanctified congregation where his uncle played the guitar as he preached. Uncle Archie Fair taught his nephew to play a few chords, but it was during visits to his Aunt Mima that King first heard the sounds of his greatest musical influences, BLIND LEMON JEFFERSON and Lonnie Johnson, wailing from a windup Victrola. He was only ten when his mother died, and he lived alone in their cabin until the plantation owner for whom he worked, Mr. Flake Cartledge, lent him fifteen dollars to buy a guitar and instruction manual from the Sears Roebuck catalog. From then on, King was never really alone again; music became his family and his life.

King lived briefly with his father’s new family in Lexington, but he soon ran away to Indianola, where he worked in the fields and sang with a group called the Famous St. John Gospel Singers. He was torn between two related musical traditions that had very different career paths. On the one hand, he dreamed his group could emulate the success of the gospel-singing Dixie Hummingbirds, and he thought of becoming a minister, despite the stuttering problem he then had. On the other hand, he found that he could make more money on weekends playing the blues for pedestrians than he made all week driving a tractor. When King heard the electric blues guitar of T-Bone Walker, his fate was sealed. He dropped out of school in the tenth grade—one of his biggest regrets—and studied the styles of the bluesmen (and blueswomen, such as BESSIE SMITH and MA RAINEY) who performed at local juke joints.

In 1944 King married Martha Denton shortly before being drafted into the army during World War II. However, after completing basic training, he was designated as a vital farmworker and released from service. On the train back to the plantation, he and other African Americans were forced to sit behind white German prisoners of war. Of white society at that time he wrote, “You can look at enemy soldiers who were ready to cut your throat, but you can’t look at the black American soldiers willing to die for you. . . . We were seen as beasts of burden, dumb animals, a level below the Germans” (King, 91).

In May 1946 Riley fled to Memphis, Tennessee, after accidentally damaging the tractor he drove. There he found his cousin, the guitarist Bukka White, who introduced him to the harsh realities of life as a bluesman. After ten months of drudgery, he was dissuaded and went back to his wife and the plantation. Nevertheless, he returned to Memphis in 1948, determined to make it as a bluesman at any cost. His big break came later that year when Sonny Boy Williams allowed him to sing on his radio program on KWEM. The enthusiastic response led to offers for local performances, and soon King found himself promoting a tonic called Pepticon; his first jingle was “Pepticon sure is good. . . and you can get it anywhere in your neighborhood.” This led to his own radio show on WDIA, called the “Sepia Swing Club.” The name he chose as a disc jockey for this program, B. B. King, stayed with him for the rest of his career.

King recorded his first song, “Take a Swing with Me,” at WDIA for Bullet Records in 1949. The company went bankrupt soon after releasing it, and King signed a contract with Modern Records, recording under their Crown and RPM labels for the next decade. He was usually paid about one hundred dollars per song and received no royalties or songwriting credits for these early productions. In 1951 he recorded a version of Lowell Fulson’s “Three O’clock Blues” that spent three months at the top of Billboard’s rhythm-and-blues chart. With this success, King engaged the promoters Robert Henry and then Maurice Merrit, who arranged bookings on the “Chitlin Circuit,” an informal network of clubs and theaters that hired black performers. By 1952 King was spending so much time on the road that his marriage, which had suffered from distance and infidelity, ended in divorce. In 1958 he married Sue Carol Hall, though in 1966 that marriage also ended in divorce. King acknowledges having fifteen children, none with either of his wives.

King’s most enduring and perhaps most passionate relationship was with Lucille, the name he gave to his trademark guitars. He once had to rescue his guitar from a nightclub that had been accidentally set ablaze by two men fighting over a woman named Lucille. King decided that from then on every guitar he owned would be his Lucille. She was personified in song and became the medium through which he could express a range of emotion, from deep pathos to liberating triumph. Drawing on the traditional twelve-bar blues style in which the singer and his guitar converse in a call-and-response counterpoint, King and Lucille became a duet recognized and loved by fans.

King worked throughout his career to overcome the perception of many scholars, critics, and casual listeners that the blues is a simple, unsophisticated art form—one that was even embarrassing to black folks of a certain age and class. He recalled appearing on a bill with some great jazz musicians, and, when his turn to perform came, the announcer told the audience, “Okay, folks, time to pull out your chitlins and collard greens, your pig feet and your watermelons, ‘cause here’s B. B. King.” King’s response to this common attitude is characteristically witty: “Being a blues singer is like being black twice” (King, 216–217).

Rock and roll came and went without King, who did not cross over, as did Bo DIDDLEY and CHUCK BERRY . Soul music became popular with the Motown sound, but though he often tried new things, King remained a true bluesman. He produced dozens of moderately selling songs like “Sweet Sixteen,” and he averaged more than three hundred engagements a year; thus, despite his gambling and problems with the 1RS, he was, by the late 1960s, successful. Yet, rather than winding down, King’s career was about to take off. In 1961 he signed with ABC Paramount. Following his second divorce in 1966, King recorded “Paying the Cost to Be the Boss” and a cathartic rendition of “The Thrill Is Gone” that connected with his widest audience ever. The song reached fifteen on the pop charts and won him the first of thirteen Grammy Awards between 1970 and 2002.

His new manager, Sidney Seidenberg, began to book King at what seemed like unlikely venues, but to King’s surprise, young white audiences loved him; so did fans in Europe, Asia, and Africa. He welcomed the fame but admitted that he was “disappointed that my people don’t appreciate me like the whites” (Current Biography, 1970). He became a frequent guest on the Tonight Show; had cameos on Sanford & Son, The Cosby Show, Sesame Street, and General Hospital; and appeared in numerous commercials. He was inducted into the Blues Foundation Hall of Fame in 1984 and into the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame in 1987. Although he was diagnosed with diabetes in 1990, King did not cut back on his full calendar of club dates. When asked at the age of seventy-seven why he continued to work so hard he said, “If I don’t keep doing it, keep going, they’ll forget” (Bernard Weinraub, New York Times, 12 March 2003, 1). King exemplifies the best of a long blues tradition that has many admirers but few authentic disciples.

King, B. B. Blues All around Me: The Autobiography of B. B. King (1996).

Current Biography (1970).

Sawyer, Charles. The Arrival of B. B. King (1980).

“Spinning Blues into Gold, the Rough Way.” New York Times, 12 Mar. 2003.

—SHOLOMO B. LEVY

KING, BOSTON

KING, BOSTON(1760?–1802), slave, Loyalist during the American Revolution, carpenter, Methodist preacher, and memoirist, was born on a plantation near Charleston, South Carolina, the son of a literate African slave who worked as a driver and a mill cutter and an enslaved mother who made clothes and tended the sick, using herbal knowledge she gained from American Indians. At the age of six Boston King began waiting on his master, Richard Waring, in the plantation house. From age nine to sixteen, he was assigned to tend the cattle and horses, and he traveled with his master’s racehorses to many places in America.

At sixteen King was apprenticed to a master carpenter. Two years later he was placed in charge of the master’s tools; on two occasions when valuable items were stolen, the master beat and tortured King so severely that he was unable to work for weeks. After the second incident, King’s owner threatened to take him away from the carpenter if the abuse was repeated. Over the next two years, King received better treatment and was able to acquire significant knowledge of carpentry. One day during the Revolutionary War, shortly after the British occupied Charleston, King obtained leave to visit his parents, who lived twelve miles away. When a servant absconded with the horse that King had borrowed for the journey, King decided to escape from what would have undoubtedly been cruel punishment by seeking refuge with the British.

Since 1775 the British had promised to free all able-bodied indentured servants and Negroes who joined the Loyalist forces. In 1779 Sir Henry Clinton, the British commander in chief, attempted to further deplete the rebel army’s resources by issuing the Philipsburg Proclamation, which promised freedom of employment to any slave who deserted from a rebel master and worked within British lines. King felt well received by the British, but after a short taste of freedom he contracted smallpox. Attempting to control the epidemic, the British segregated infected black people from the rest of the camp and left them to languish without food or drink, sometimes for a day at a time. A kindly New York volunteer came to King’s rescue and helped nurse him back to health, a favor that King returned a few weeks later when this man was wounded in battle. King nursed him for six weeks until he recovered. King stayed with the British in areas surrounding Charleston for several months, performing a range of personal and military services.

In December 1782 the British left Charleston, taking with them 5,327 African Americans, who relocated to various sites within the British Empire. King sailed to New York, the British military headquarters. He wanted to work as a carpenter, but lack of tools forced him to accept employment in domestic service, where “the wages were so low that I was not able to keep myself in clothes, so that I was under the necessity of leaving my master and going to another. I stayed with him four months, but he never paid me” (King, 355). In these desperate economic straits King met and married a woman named Violet who had been enslaved in Wilmington, North Carolina. A year later he went to work on a pilot boat that was captured by an American whaler; he was transported to New Brunswick, New Jersey, and once again enslaved. Although he was well fed and pleased to find that many local slaves were allowed to go to school at night, he yearned for liberty and grabbed the first chance to escape across the river and find his way back to New York.

Reunited with Violet, King remained in New York until the end of the war. Although he was glad to see the horrors of war come to an end, King and the other former slaves were terrified that they would be sent back to their old masters, as the Americans demanded. However, the British commander in chief, Sir Guy Carleton, insisted that those blacks who had been with the British before the provisional treaty was signed by both sides in Paris on 30 November 1782 would remain free, while those who had sought refuge with the British after that date were to be returned to their American masters. The British compiled a “Book of Negroes,” listing the black people whom they were taking with them out of New York. Boston King, a “Stout fellow” aged twenty-three, and Violet King, a “Stout wench” aged thirty-five, “were among the 409 passengers who sailed on 31 July 1783 from New York to Shelburne” in Nova Scotia (King, 367). They settled in a black community called Birchtown, which was built on one side of the Port Roseway Harbour while Shelburne, a white Loyalist town, was built on the opposite side. The British promised land and provisions to the loyalist settlers, but while “the Whites received farm lands. . . averaging 74 acres by November 1786, of the 649 Black men at Birchtown only 184 received farms averaging 34 acres by the year 1788” (Blakeley, 277). Nonetheless, as a skilled carpenter at a time when every family needed to build a house, King appears to have found work plentiful for a time.

During the cold Canadian winter, a religious revival spread throughout Birchtown. Violet King experienced an “awakening” when listening to the preaching of Moses Wilkinson, a blind and lame former slave from Virginia. Boston King soon followed her lead. Taught by Methodist missionaries, such as Freeborn Garretson of Baltimore, “who had manumitted his own slaves immediately upon his conversion in 1775” (Carretta, 368), King in 1785 began to preach to both black and white people. Meanwhile, the black people in Birchtown were in desperate straits. The little land that they were given was so barren that they were forced to work for white farmers, when they could find work at all. A terrible famine set in, and the Kings scrambled to survive. In 1791 King moved to Preston, near Halifax, where he continued preaching and supported himself in domestic service.

Meanwhile, Lieutenant John Clarkson, the brother of the prominent British abolitionist Thomas Clark-son, arrived in Halifax as the agent for the Sierra Leone Company, which intended to resettle former slaves in Africa and to promote trade with Africa. The company promised free passage, thirty acres of land for every married man, and sufficient provisions to sustain the settlers until they were established in Sierra Leone. Although King’s preaching in Preston was proceeding to his “great satisfaction, and the Society increased both in number and love” (King, 363), he had long desired to preach to Africans. On 15 January 1792 Boston and Violet King joined 1,188 other blacks who set sail from Halifax in a fleet of fifteen ships. The journey was troubled by terrible storms and disease, and when they arrived in Sierra Leone they found that once again the British had broken their promises. An outbreak of malaria killed people so fast that it was hard to bury them. Violet King died from malaria in April 1792. Boston King grew ill but recovered and found work as a carpenter and preacher.

On 3 August 1793 Governor Richard Dawes appointed King a missionary and schoolteacher at sixty pounds a year and promised to send him to England to obtain the education that he greatly desired (Blakeley, 286). After remarrying, King embarked for England in March 1794 and spent two years at the Kingswood School, a Methodist secondary school near Bristol, where he wrote his memoirs in 1796. A few months later he returned to Sierra Leone, where he worked as a teacher and preacher until his death.

King, Boston. “Memoirs of the Life of Boston King, a Black Preacher. Written by Himself, during His Residence at Kingswood-School.” Arminian [or Methodist] Magazine 21 (March, April, May, and June 1798). Reprinted in Unchained Voices: An Anthology of Black Authors in the English-Speaking World of the Eighteenth-Century, ed. Vincent Carretta (1996).

Blakeley, Phyllis R. “Boston King: A Black Loyalist” in Eleven Exiles: Accounts of Loyalists of the American Revolution, eds. Phyllis R. Blakely and John N. Grant (1982).

—KARI J. WINTER

KING, CORETTA SCOTT

KING, CORETTA SCOTT(27 Apr. 1927–), was born in Heiberger, near Marion, Alabama, the second of three children of Obadiah Scott and Bernice McMurry, who farmed their own land. Although Coretta and her siblings worked in the garden and fields, hoeing and picking cotton, the Scotts were relatively well off. Her father was the first African American in the community to own a truck, which he used to transport pulpwood, and he also purchased his own sawmill, which was mysteriously burned to the ground a few days later. The family blamed the fire on whites jealous of their success.

Wanting a better life for their children, the Scotts sent all three to college. The eldest, Edythe, graduated at the top of her class at Marion’s Lincoln High School in 1943 and earned a scholarship to Antioch College in Yellow Springs, Ohio; her brother, Obie, attended Central State University in nearby Wilberforce, Ohio. Coretta, who also graduated at the top of her high school class in 1945, won a scholarship to study elementary education and music at Antioch. She matriculated in 1945 and was one of only three African Americans in her class; the future jurist A. LEON HIGGINBOTHAM was one of the others. Scott was active in extracurricular activities, especially in projects designed to improve race relations. She joined the college chapter of the NAACP and performed onstage at Antioch with PAUL ROBESON, the actor, singer, and activist, who encouraged her to pursue a musical career.

Although Antioch enjoyed a liberal reputation, Coretta found that it was not immune to racial discrimination. When she applied to practice as a student teacher, the music department required that she do so at an all-black school system near the campus. The school district in which all other Antioch students did their practice work had no black teachers, and the college administration did not wish to upset the racial status quo in conservative southern Ohio by sending an African American student to teach there. Coretta Scott protested this Jim Crow policy to the office of the college president, but the president refused to support her request. She subsequently agreed to do her internship at the demonstration school on campus.

Scott studied piano and the violin, but focused on singing. She gave her first solo concert in 1948 and graduated with a BA from Antioch in Music Education three years later, in 1951. That year she enrolled at the New England Conservatory of Music in Boston, Massachusetts, on a full-tuition fellowship. With assistance from the Urban League, she found part-time work as a clerical assistant and also received out-of-state aid from Alabama, since her home state provided no opportunities for graduate study in music.

Coretta Scott King shaking hands with A. PHILIP RANDOLPH about 1969 as (left to right) BAYARD RUSTIN, George Meany, Nelson Rockefeller, and others look on. Library of Congress

Moving to Boston changed the course of Coretta Scott’s life in more ways than one, for in 1952 a friend there introduced her to MARTIN LUTHER KING JR., an ordained Baptist minister who was attending Boston University’s School of Theology. Although she has said that she never wanted to be the wife of a pastor, Scott warmed to the theology student’s sincere passion for social justice and also fell for his distinctive line of flattery. She later recalled that King “was a typical man. Smoothness. Jive. Some of it I had never heard of in my life. It was what I call intellectual jive” (Garrow, 45). King, for his part, admired Scott for standing up to his father, who wanted him to marry into one of Atlanta’s leading black families. Scott bluntly told the imposing Daddy King that she, too, was from one of the finest families. Soon thereafter King Sr. accepted his son’s choice and performed the couple’s wedding ceremony in June 1953. Coretta asserted her independence, however, by excluding a promise to obey her husband in her wedding vows. In 1954, the year Coretta Scott King graduated from the New England Conservatory of Music, her husband accepted the pastorate of Dexter Avenue Baptist Church in Montgomery, Alabama.

The young couple could not have known that the direction of their lives again would be dramatically altered the following year. On 1 December 1955, ROSA PARKS, a local NAACP official, was arrested for refusing to give up her seat on a city bus in Montgomery. Her arrest changed the course of southern history, for it united and mobilized Montgomery’s black community under Martin Luther King’s leadership in a mass boycott of the city’s segregated bus system. The subsequent national and international press coverage made the young minister and his wife household names, but the limelight brought with it new dangers. During the bus boycott, angry whites made abusive and life-threatening telephone calls at all hours and shot at and bombed the King family home. In 1958 a mentally disturbed black woman attempted to assassinate Martin by stabbing him in a New York department store.

Like any other couple’s, the Kings’ married life was not untroubled. Money was a constant source of friction, since Martin paid little heed to financial matters and left his wife to deal with the day-to-day problems of looking after four children. Rumors of her husband’s infidelities were also widespread during his lifetime, often encouraged by FBI mischief making. Coretta has always claimed, however, that she and Martin “never had one single serious discussion about either of us being involved with another person” (Garrow, 374).

Under such trying circumstances Coretta King developed an iron will and a steely resolve to support her husband’s commitment to civil rights. She also supported him by handling mail, telephone calls, and other administrative work, sometimes speaking at engagements that he was unable to attend and participating in musical programs to raise funds for the Southern Christian Leadership Conference (SCLC). Coretta’s primary focus in the early years of the civil rights movement, however, was her family. She gave birth to four children: Yolande in 1955, Martin III in 1957, Dexter in 1961, and Bernice in 1963. There were occasions, however, when she resented her husband’s full immersion in the civil rights movement. In 1963 she told a reporter that she regretted being absent from many of the era’s most important civil rights demonstrations. “I’m usually at home,” she remarked, “because my husband says, ‘You have to take care of the children’” (Garrow, 308). Other women in the civil rights movement, notably ELLA BAKER, often remarked on the traditionalist—indeed, sexist—view of gender roles held by Martin Luther King and other prominent clergymen.

Coretta King was less content to take a back seat when it came to matters of war and peace, as she had been a committed pacifist since her time at Antioch, where visiting speakers like BAYARD RUSTIN had encouraged her nonviolent philosophy. Coretta strongly influenced her husband’s evolving opposition to the Vietnam War. In 1961 she attended a disarmament conference in Geneva, Switzerland, as a member of the group Women Strike for Peace. While her husband refrained from publicly challenging the Kennedy and Johnson administrations’ foreign policy in the early 1960s, Coretta King attended several peace rallies and picketed the White House in 1965.

Tragically, Coretta Scott King would take center stage in the civil rights movement only after her husband’s assassination in Memphis, Tennessee, on 4 April 1968. Four days later she led a memorial march in Memphis, estimated at fifty thousand people. The international media spotlight continued to focus on the slain civil rights leader’s family during King’s funeral in Atlanta, which was attended by thousands of mourners and watched by millions on television. Coretta Scott King supported several SCLC projects in the wake of her husband’s death. In the summer of 1968 she was one of the speakers at the Poor People’s Campaign in Washington, D.C., and received national media attention when she, along with others in SCLC, led a protest march by striking hospital workers in Charleston, South Carolina, in 1969.

In the 1970s Coretta King established and chaired the Martin L. King Jr. Memorial Center for Nonviolent Social Change in Atlanta. This project took her around the world in search of financial support, lecturing to audiences numbering in the hundreds. The King Center, which was dedicated on Auburn Avenue in Atlanta in 1981, contains more than one million documents related to the King family’s civil rights activities. Several thousand scholars have used its library resources since it was established, but in the 1990s Coretta King and her family came under fire for the way she tightly controlled her husband’s legacy, including his image and papers. She was also involved in a feud with the National Park Service over their handling of the King property on Auburn Avenue.

Coretta King’s most enduring contribution to American culture has been as chair of the Martin L. King Jr. Federal Holiday Commission. In the late 1970s the King Center collected six million signatures on a petition urging the creation of a Martin Luther King Jr. memorial holiday, and in November 1983 President Ronald Reagan signed the bill designating the national holiday. The center also sponsors an annual celebratory memorial program on his birth date. King’s involvement in the civil rights cause continued in the 1980s and 1990s. She was prominent in demonstrations against South Africa’s apartheid system and has appeared at anniversary celebrations of her husband’s most memorable speech at the 1963 March on Washington. In 1997 she supported a move granting a new trial for her husband’s convicted assassin, James Earl Ray, but Ray died before a new trial was scheduled. Her most recent cause has been a project to build a memorial for her husband on the National Mall in Washington, D.C. The Alpha Phi Alpha fraternity, of which he was a member, is also associated with this project.

Throughout her lifetime, Coretta Scott King has supported many progressive measures and received many awards and numerous honorary degrees. Perhaps the most prestigious and enduring was not given to her but rather is awarded in her name. The American Library Association’s Coretta Scott King Award, established in the early 1970s, is given to highly distinguished African American writers and illustrators of children’s literature.

King, Coretta Scott. My Life with Martin Luther King, Jr. (1969; rev. 1993).

Baldwin, Lewis V. There Is a Balm in Gilead: The Cultural Roots of Martin Luther King, Jr. (1991).

Branch, Taylor. Parting the Waters: America in the King Years, 1954–1963 (1988).

Garrow, David. Bearing the Cross: Martin Luther King, Jr., and the Southern Christian Leadership Conference (1988).

Vivian, Octavia. Coretta: The Story of Mrs. Martin Luther King, Jr. (1970).

—BARBARA WOODS

KING, MARTIN LUTHER, JR.

KING, MARTIN LUTHER, JR.(15 Jan. 1929–4 Apr. 1968), Baptist minister and civil rights leader, was born Michael King Jr., in Atlanta, Georgia, the son of the Reverend Michael King and Alberta Williams. Born to a family with deep roots in the African American Baptist church and in the Atlanta black community, the younger King spent his first twelve years in the home on Auburn Avenue that his parents shared with his maternal grandparents. A block away, also on Auburn, was Ebenezer Baptist Church, where his grandfather, the Reverend Adam Daniel Williams, had served as pastor since 1894. Under Williams’s leadership, Ebenezer had grown from a small congregation without a building to become one of Atlanta’s prominent African American churches. After Williams’s death in 1931, his son-in-law became Ebenezer’s new pastor and gradually established himself as a major figure in state and national Baptist groups. In 1934 the elder King, following the request of his own dying father, changed his name and that of his son to Martin Luther King.

King’s formative experiences not only immersed him in the affairs of Ebenezer but also introduced him to the African American social gospel tradition exemplified by his father and grandfather, both of whom were leaders of the Atlanta branch of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People. Depression-era breadlines heightened his awareness of economic inequities, and his father’s leadership of campaigns against racial discrimination in voting and teachers’ salaries provided a model for the younger King’s own politically engaged ministry. He resisted religious emotionalism and as a teenager questioned some facets of Baptist doctrine, such as the bodily resurrection of Jesus.

During his undergraduate years at Atlanta’s Morehouse College from 1944 to 1948, King gradually overcame his initial reluctance to accept his inherited calling. Morehouse president BENJAMIN MAYS influenced King’s spiritual development, encouraging him to view Christianity as a potential force for progressive social change. Religion professor George Kelsey exposed him to biblical criticism and, according to King’s autobiographical sketch, taught him “that behind the legends and myths of the Book were many profound truths which one could not escape.” King admired both educators as deeply religious yet also learned men. By the end of his junior year, such academic role models and the example of his father led King to enter the ministry. He described his decision as a response to an “inner urge” calling him to “serve God and humanity.” He was ordained during his final semester at Morehouse. By this time King had also taken his first steps toward political activism. He had responded to the postwar wave of antiblack violence by proclaiming in a letter to the editor of the Atlanta Constitution that African Americans were “entitled to the basic rights and opportunities of American citizens.” During his senior year King joined the Intercollegiate Council, an interracial student discussion group that met monthly at Atlanta’s Emory University.

Martin Luther King addresses a gathering after postponing the Selma-to-Montgomery March. Library of Congress

After leaving Morehouse, King increased his understanding of liberal Christian thought while attending Crozer Theological Seminary in Pennsylvania from 1948 to 1951. Initially uncritical of liberal theology, he gradually moved toward Reinhold Niebuhr’s neoorthodoxy, which emphasized the intractability of social evil. He reacted skeptically to a presentation on pacifism by Fellowship of Reconciliation leader A. J. Muste. Moreover, by the end of his seminary studies King had become increasingly dissatisfied with the abstract conceptions of God held by some modern theologians and identified himself instead with theologians who affirmed the personality of God. Even as he continued to question and modify his own religious beliefs, he compiled an outstanding academic record and graduated at the top of his class.

In 1951 King began doctoral studies in systematic theology at Boston University’s School of Theology, which was dominated by personalist theologians. The papers (including his dissertation) that King wrote during his years at Boston displayed little originality, and some contained extensive plagiarism, but his readings enabled him to formulate an eclectic yet coherent theological perspective. By the time he completed his doctoral studies in 1955, King had refined his exceptional ability to draw upon a wide range of theological and philosophical texts to express his views with force and precision. His ability to infuse his oratory with borrowed theological insights became evident in his expanding preaching activities in Boston-area churches and at Ebenezer, where he assisted his father during school vacations.

During his stay at Boston, King also met and courted Coretta Scott (CORETTA SCOTT KING), an Alabama-born Antioch College graduate who was then a student at the New England Conservatory of Music. On 18 June 1953 the two students were married in Marion, Alabama, where Scott’s family lived. During the following academic year King began work on his dissertation, which he completed during the spring of 1955.

Although he considered pursuing an academic career, King decided in 1954 to accept an offer to become the pastor of Dexter Avenue Baptist Church in Montgomery, Alabama. In December 1955, when Montgomery black leaders formed the Montgomery Improvement Association to protest the arrest of NAACP official ROSA PARKS for refusing to give up her bus seat to a white man, they selected King to head the new group. With King as the primary spokesman and with grassroots organizers such as DAISY BATES, the association led a yearlong bus boycott. King utilized the leadership abilities he had gained from his religious background and academic training and gradually forged a distinctive protest strategy that involved the mobilization of black churches and skillful appeals for white support. As King encountered increasingly fierce white opposition, he continued his movement away from theological abstractions toward more reassuring conceptions, rooted in African American religious culture, of God as a constant source of support. He later wrote in his book of sermons, Strength to Love (1963), that the travails of movement leadership caused him to abandon the notion of God as a “theological and philosophically satisfying metaphysical category” and caused him to view God as “a living reality that has been validated in the experiences of everyday life.” With the encouragement of BAYARD RUSTIN and other veteran pacifists, King also became a firm advocate of Mohandas Gandhi’s precepts of nonviolence, which he combined with Christian principles.

After the Supreme Court outlawed Alabama bus segregation laws in late 1956, King sought to expand the nonviolent civil rights movement throughout the South. In 1957 he became the founding president of the Southern Christian Leadership Conference (SCLC), formed to coordinate civil rights activities throughout the region. Publication of Stride toward Freedom: The Montgomery Story (1958) further contributed to King’s rapid emergence as a national civil rights leader. Even as he expanded his influence, however, King acted cautiously. Rather than immediately seeking to stimulate mass desegregation protests in the South, King stressed the goal of achieving black voting rights when he addressed an audience at the 1957 Prayer Pilgrimage for Freedom. During 1959 he increased his understanding of Gandhian ideas during a month-long visit to India as the guest of Prime Minister Jawaharlal Nehru. Early the following year he moved his family, which now included two children, to Atlanta in order to be nearer SCLC headquarters in that city and to become co-pastor, with his father, of Ebenezer Baptist Church. (The Kings’ third child was born in 1961; their fourth was born in 1963.)

Soon after King’s arrival in Atlanta, the southern civil rights movement gained new impetus from the student-led lunch counter sit-in movement that spread throughout the region during 1960. King dispatched ELLA BAKER to North Carolina to organize students who had staged a protest there. The sit-ins brought into existence a new protest group, the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC). Its early leaders, such as JOHN LEWIS, worked closely with King, but by the late 1960s STOKELY CARMICHAEL and H. RAP BROWN attempted to push King toward greater militancy. In October 1960 King’s arrest during a student-initiated protest in Atlanta became an issue in the national presidential campaign when Democratic candidate John F. Kennedy called Coretta King to express his concern. The successful efforts of Kennedy supporters to secure King’s release contributed to the Democratic candidate’s narrow victory.

As the southern protest movement expanded during the early 1960s, King was often torn between the increasingly militant student activists and more cautious national civil rights leaders. During 1961 and 1962 his tactical differences with SNCC activists surfaced during a sustained protest movement in Albany, Georgia. King was arrested twice during demonstrations organized by the Albany Movement, but when he left jail and ultimately left Albany without achieving a victory, some movement activists began to question his militancy and his dominant role within the southern protest movement.

During 1963, however, King reasserted his preeminence within the African American freedom struggle through his leadership of the Birmingham campaign. Initiated by SCLC in January, the Birmingham demonstrations were the most massive civil rights protest that had yet occurred. With the assistance of Fred Shuttlesworth and other local black leaders and with little competition from SNCC and other civil rights groups, SCLC officials were able to orchestrate the Birmingham protests to achieve maximum national impact. King’s decision to intentionally allow himself to be arrested for leading a demonstration on 12 April prodded the Kennedy administration to intervene in the escalating protests. A widely quoted letter that King wrote while jailed displayed his distinctive ability to influence public opinion by appropriating ideas from the Bible, the Constitution, and other canonical texts. During May, televised pictures of police using dogs and fire hoses against demonstrators generated a national outcry against white segregationist officials in Birmingham. The brutality of Birmingham officials and the refusal of Alabama governor George C. Wallace to allow the admission of black students at the University of Alabama prompted President Kennedy to introduce major civil rights legislation.

King’s speech at the 28 August 1963 March on Washington, attended by more than 200,000 people, was the culmination of a wave of civil rights protest activity that extended even to northern cities. In King’s prepared remarks he announced that African Americans wished to cash the “promissory note” signified in the egalitarian rhetoric of the Constitution and the Declaration of Independence. Closing his address with extemporaneous remarks, he insisted that he had not lost hope: “So I say to you, my friends, that even though we must face the difficulties of today and tomorrow, I still have a dream. It is a dream deeply rooted in the American dream that one day this nation will rise up and live out the true meaning of its creed—we hold these truths to be self-evident, that all men are created equal.” He appropriated the familiar words of “My Country ’Tis of Thee” before concluding, “And when we allow freedom to ring, when we let it ring from every village and hamlet, from every state and city, we will be able to speed up that day when all of God’s children—black men and white men, Jews and Gentiles, Catholics and Protestants—will be able to join hands and to sing in the words of the old Negro spiritual, ‘Free at last, free at last, thank God Almighty, we are free at last.’”

King’s ability to focus national attention on orchestrated confrontations with racist authorities, combined with his oration at the 1963 March on Washington, made him the most influential African American spokesperson of the first half of the 1960s. Named Time magazine’s man of the year at the end of 1963, he was awarded the Nobel Peace Prize in December 1964. The acclaim King received strengthened his stature among civil rights leaders but also prompted Federal Bureau of Investigation director J. Edgar Hoover to step up his effort to damage King’s reputation. Hoover, with the approval of President Kennedy and Attorney General Robert Kennedy, established phone taps and bugs. Hoover and many other observers of the southern struggle saw King as controlling events, but he was actually a moderating force within an increasingly diverse black militancy of the mid-1960s. As the African American struggle expanded from desegregation protests to mass movements seeking economic and political gains in the North as well as the South, King’s active involvement was limited to a few highly publicized civil rights campaigns, particularly the major series of voting rights protests that began in Selma, Alabama, early in 1965, which secured popular support for the passage of national civil rights legislation, particularly the Civil Rights Act of 1964.

The Alabama protests reached a turning point on 7 March when state police attacked a group of SCLC demonstrators led by Hosea Williams at the start of a march from Selma to the state capitol in Montgomery. Carrying out Governor Wallace’s orders, the police used tear gas and clubs to turn back the marchers soon after they crossed the Edmund Pettus Bridge on the outskirts of Selma. Unprepared for the violent confrontation, King was in Atlanta to deliver a sermon when the incident occurred but returned to Selma to mobilize nationwide support for the voting rights campaign. King alienated some activists when he decided to postpone the continuation of the Selma-to-Montgomery march until he had received court approval, but the march, which finally secured federal court approval, attracted several thousand civil rights sympathizers, black and white, from all regions of the nation. On 25 March, King addressed the arriving marchers from the steps of the capitol in Montgomery. The march and the subsequent killing of a white participant, Viola Liuzzo, dramatized the denial of black voting rights and spurred passage during the following summer of the Voting Rights Act of 1965.

After the successful voting rights march in Alabama, King was unable to garner similar support for his effort to confront the problems of northern urban blacks. Early in 1966 he launched a major campaign against poverty and other urban problems, moving into an apartment in the black ghetto of Chicago. As King shifted the focus of his activities to the North, however, he discovered that the tactics used in the South were not as effective elsewhere. He encountered formidable opposition from Mayor Richard Daley and was unable to mobilize Chicago’s economically and ideologically diverse black community. King was stoned by angry whites in the Chicago suburb of Cicero when he led a march against racial discrimination in housing. Despite numerous mass protests, the Chicago campaign resulted in no significant gains and undermined King’s reputation as an effective civil rights leader.

King’s influence was further undermined by the increasingly caustic tone of black militancy of the period after 1965. Black militants increasingly turned away from the Gandhian precepts of King toward the black nationalism of MALCOLM X, whose posthumously published autobiography and speeches reached large audiences after his assassination in February 1965. Unable to influence the black insurgencies that occurred in many urban areas, King refused to abandon his firmly rooted beliefs about racial integration and nonviolence. He was nevertheless unpersuaded by black nationalist calls for racial uplift and institutional development in black communities. In his last book, Where Do We Go from Here: Chaos or Community? (1967), King dismissed the claim of Black Power advocates “to be the most revolutionary wing of the social revolution taking place in the United States,” but he acknowledged that they responded to a psychological need among African Americans he had not previously addressed. “Psychological freedom, a firm sense of self-esteem, is the most powerful weapon against the long night of physical slavery,” King wrote. “The Negro will only be truly free when he reaches down to the inner depths of his own being and signs with the pen and ink of assertive selfhood his own emancipation proclamation.”

Indeed, even as his popularity declined, King spoke out strongly against American involvement in the Vietnam War, making his position public in an address on 4 April 1967 at New York’s Riverside Church. King’s involvement in the antiwar movement reduced his ability to influence national racial policies and made him a target of further FBI investigations. Nevertheless, he became ever more insistent that his version of Gandhian nonviolence and social gospel Christianity was the most appropriate response to the problems of black Americans.

In November 1967 King announced the formation of the Poor People’s Campaign, designed to prod the federal government to strengthen its antipoverty efforts. King, ANDREW YOUNG, JESSE JACKSON, and other SCLC workers began to recruit poor people and antipoverty activists to come to Washington, D.C., to lobby on behalf of improved antipoverty programs. This effort was in its early stages when King became involved in a sanitation workers’ strike in Memphis, Tennessee. On 28 March 1968, as King led thousands of sanitation workers and sympathizers on a march through downtown Memphis, black youngsters began throwing rocks and looting stores. This outbreak of violence led to extensive press criticisms of King’s entire antipoverty strategy. King returned to Memphis for the last time in early April. Addressing an audience at Bishop Charles J. Mason Temple on 3 April, King affirmed his optimism despite the “difficult days” that lay ahead. “But it doesn’t matter with me now,” he declared, “because I’ve been to the mountaintop [and] I’ve seen the promised land.” He continued, “I may not get there with you. But I want you to know tonight, that we, as a people, will get to the promised land.” The following evening King was assassinated as he stood on a balcony of the Lorraine Motel in Memphis. A white segregationist, James Earl Ray, was later convicted of the crime. The Poor People’s Campaign continued for a few months after his death but did not achieve its objectives.

Until his death King remained steadfast in his commitment to the radical transformation of American society through nonviolent activism. In his posthumously published essay, “A Testament of Hope” (1986), he urged African Americans to refrain from violence but also warned, “White America must recognize that justice for black people cannot be achieved without radical changes in the structure of our society.” The “black revolution” was more than a civil rights movement, he insisted. “It is forcing America to face all its interrelated flaws—racism, poverty, militarism and materialism.”

After king’s death, RALPH ABERNATHY assumed leadership of SCLC, and Coretta Scott King established the Atlanta-based Martin Luther King Jr. Center for Nonviolent Social Change to promote Gandhian-Kingian concepts of nonviolent struggle. She led the successful effort to honor King with a federal holiday on the anniversary of his birthday, which was first celebrated in 1986.

Collections of King’s papers are at the Martin Luther King Jr. Center for Nonviolent Social Change in Atlanta and the Mugar Memorial Library at Boston University.

Branch, Taylor. Parting the Waters: America in the King Years, 1954–63 (1988).

_______ Pillar of Fire: America in the King Years, 1963–65 (1998).

Garrow, David J. Bearing the Cross: Martin Luther King Jr. and the Southern Christian Leadership Conference, 1955–1968 (1986).

Lewis, David Levering. King: A Biography, 2d ed. (1978).

Oates, Stephen B. Let the Trumpet Sound: The Life of Martin Luther King Jr. (1982).

Washington, James Melvin, ed. A Testament of Hope: The Essential Writings of Martin Luther King Jr. (1986).

Obituary: New York Times, 5 Apr. 1968.

—CLAYBORNE CARSON

KIRK, GABRIELLE.

KIRK, GABRIELLE.See McDonald, Gabrielle Kirk.

KITT, EARTHA MAE

KITT, EARTHA MAE(26 Jan. 1928–) singer and actor, was born to William Kitt and Anna Mae Riley, sharecroppers, in North, South Carolina. As young children, Eartha and her younger half-sister, Anna Pearl, were abandoned by their father and later by their mother. The sisters lived on a farm with a foster family until 1936, when they moved to New York City to live with their aunt, Mamie Lue Riley, a domestic. As an adolescent, Eartha attended Metropolitan High School (later called the High School of Performing Arts). She relished her unusual voice and facility with language, sang, danced, played baseball, and became a pole-vaulting champion. Eartha left school at age fourteen, and two years later she met KATHERINE DUNHAM, who offered her a dance scholarship and then a spot as a singer and dancer with her troupe. Kitt toured Mexico, South America, and Europe with Dunham and quickly emerged as a soloist. When the tour ended, she remained in Paris, launching a career as a nightclub entertainer. Her provocative and sensual dancing style and her throaty singing voice enthralled audiences from France to Egypt and from Los Angeles to Stockholm.

In 1951 Orson Welles gave Kitt her first role in the legitimate theater when he cast her as Helen of Troy in his stage production Faust. Kitt won critical reviews for her performance and toured with the play through Germany and Turkey, after which she returned to New York and audiences at the Village Vanguard and La Vie en Rose. When the producer Leonard Stillman saw her in Faust, he was inspired to revive his New Faces Broadway revue, and Kitt’s debut in New Faces of 1952 was an instant sensation. Brook Atkinson of the New York Times encapsulated audience reaction to her breakout performance in his stage review: “Eartha Kitt panics the customers with some very combustible singing and performing.… Now we know why the city is so strict about its fire laws in the theater.” Stillman’s hit show was followed by a 1954 film version, in which Kitt starred, and a best-selling Broadway album featuring Kitt’s fiery version of “Monotonous,” which began her record career. Her first solo album, a self-titled record released in 1953, includes a range of songs from “African Lullaby” to “C’est Si Bon” and “I Wanna Be Evil.”

Eartha Kitt, a sophisticated performer whose public persona ranged from sex kitten to Catwoman to Cinderella’s fairy godmother. © Arthur Rothstein/CORBIS

Throughout the 1950s and 1960s Kitt flourished in a succession of entertainment media. Smitten by her combination of husky sexiness, talent, and elegant titillation, journalists published a swell of articles and interviews. She performed for sold-out crowds in cabarets and nightclubs throughout the United States and abroad, and she regularly released studio and live albums. Her starring role in the 1955 Broadway play Mrs. Patterson, which ran for one hundred and one performances, earned her a Tony nomination. She continued working on Broadway in the musicals Shinbone Alley (1957) and Jolly’s Progress (1959). Hollywood took notice of Kitt’s popularity and dynamic presence, casting her in The Accused (1957); the W. C. HANDY biographical film St. Louis Blues (1958); and the title role, opposite SAMMY DAVIS JR. and NAT KING COLE, in an all-black version of Anna Lucasta (1959), for which she earned an Oscar nomination. Kitt’s versatility and playful style were perfect for the developing medium of television, and her increasing visibility was due in part to frequent appearances on 1950s variety shows like The Ed Sullivan Show, Your Show of Shows, Colgate Comedy Hour, and Toast of the Town. A favorite guest of television show hosts, she was equally hospitable to television audiences, even touring her Riverside Drive penthouse for Edward R. Murrow’s viewers on Person to Person. She made guest appearances on many of the 1960s hit shows, including I Spy, What’s My Line?, and Mission Impossible.

During this period, Kitt enjoyed a glamorous and opulent lifestyle. Although she was romantically linked with the Continental playboy Porfirio Rubirosa, the movie theater chain heir Arthur Loew Jr., the cosmetics mogul Charles Revson, and Sammy Davis Jr., Kitt married William McDonald in 1960. The couple had one daughter, Kitt, and divorced in 1965.

In 1968 Kitt was invited to the White House for the “Women Doers’ Luncheon,” hosted by Lady Bird Johnson and publicized as a discussion on juvenile delinquency. When Kitt’s speech linked America’s racial and social problems to the war in Vietnam, goodwill toward the star evaporated. Beginning with news reports that claimed her comments had made the First Lady cry, Kitt was excoriated in the press. While MARTIN LUTHER KING JR. and other antiwar activists lauded her remarks (some even wore “Eartha Kitt for President” buttons), general attitudes toward the star were critical. Contrary to conventional wisdom, Kitt did continue to work after the incident, primarily overseas, although she was forced to contend with invasive FBI and CIA investigations, press ridicule, loss of popularity, and limited career options. She drew criticism again in 1972, this time from African Americans, when she performed in South Africa after receiving temporary “white status.”

In the 1970s and 1980s Kitt worked primarily as a cabaret entertainer and occasionally as an actor. She resumed recording in the 1980s, releasing more than a dozen albums in less than a decade, and returned to Broadway in 1978 in an all-black version of Geoffrey Holder’s Kismet, Timbukto, for which she earned her second Tony nomination. I Love Men, Kitt’s 1984 album, found an audience with the gay disco crowd and enhanced her reputation as a gay icon. In the 1990s Kitt performed her one-woman show in London and New York, released a five-CD retrospective, Eartha Quake, and appeared in cameo roles in several Hollywood films.