LACY, SAM

LACY, SAM LACY, SAM

LACY, SAM(23 Oct. 1903?–8 May 2003), sports columnist and editor, was born Samuel Harold Lacy, one of five children of Rose and Samuel Erskine Lacy. Many publications (including his own autobiography) state that Lacy was born in Mystic, Connecticut, but recent research suggests that he may have been born in 1905 in Washington, D.C. His mother, a Shinnecock Indian, was a hairdresser and the family disciplinarian; his father was a notary and legal researcher as well as an avid baseball fan. Lacy was raised in Washington, D.C., moving often within the city during his youth. Although the Lacys were not members of Washington’s professionally accomplished African American middle class, they strove to improve their social standing through hard work and education.

To that end, Lacy began working when he was about eight years old, shining shoes, selling newspapers, and setting pins at a bowling alley. Later, he shagged fly balls during batting practice for the Washington Nationals (later known as the Senators) baseball team. Popular with many of the ballplayers, Lacy often ran errands for them and eventually worked as a vendor at Griffith Stadium, where he saw major league stars like Ty Cobb and Babe Ruth play, as well as such Negro league stars as Oscar Charleston and John Henry Lloyd. Like the rest of America, baseball was rigidly segregated. “I was in a position to make some comparisons,” Lacy reminisced in 1990, “and it seemed to me that those black players were good enough to play in the big leagues. There was, of course, no talk then of that ever happening. When I was growing up, there was no real opportunity for blacks in any sport” (Fimrite, 90).

At Armstrong Technical High School, the small, lithe Lacy played baseball, basketball, and football. After graduating in 1924, Lacy played semipro baseball, coached and promoted basketball, briefly attended Howard University, and worked as a part-time journalist and radio announcer. In October 1926 he joined the Washington Tribune full time, soon thereafter becoming its sports editor. In 1927 Lacy married Alberta Robinson—they had one son, Samuel Howe. They were divorced in 1952 and a year later he married Barbara Robinson, a government worker.

During the summer of 1929 Lacy left the Tribune to play baseball in Connecticut but returned to the newspaper in 1930, regaining his position as sports editor in July 1933. “By the mid-1930s, married for several years and with the dream of a baseball career no longer a realistic option, I finally was ready to make the move into full-time journalism with the Washington Tribune, where I worked from 1934 to 1938” (Lacy, 27).

It was in the mid-1930s that Lacy began agitating for social change, joining contemporaries like the labor leader A. PHILIP RANDOLPH, the law dean CHARLES HAMILTON HOUSTON, and his fellow sportswriter Wendell Smith. Indeed, for the rest of his life, having found his voice as a “race man,” Lacy criticized a wide variety of racial injustices in the sports world. The list is long, but one of his first big stories came in October 1937, when he reported that Syracuse University’s star player, Wilmeth Sidat-Singh, was not in fact a “Hindu,” as was widely reported, but was an American-born black man. Lacy printed the truth, and Syracuse bowed to the University of Maryland’s refusal to compete if the player stayed in the lineup. It was a story that elicited criticism, even among African Americans. Lacy stood behind his story, arguing that racial progress demanded honesty. Years later Lacy wrote, “Call ’em as you see ’em and accept the comebacks. Take it in stride, the same as other distractions. That’s the way it was. Push forward or get pushed aside” (Lacy, 7).

Baseball, the national pastime and an important cultural institution, was at the forefront of Lacy’s agenda. The injustice of the game’s racial bigotry and exclusion motivated him. Perhaps encouraged by the response to the Sidat-Singh incident, Lacy met with the Senators owner, Clark Griffith, in December 1937 to discuss the hiring of black ballplayers. Lacy suggested that Griffith sign the Negro league greats JOSH GIBSON and Buck Leonard of the Homestead Grays. Griffith objected, saying that integration would devastate the Negro leagues “and put about 400 colored guys out of work.” Lacy reportedly responded: “When Abraham Lincoln signed the Emancipation Proclamation, he put 400,000 black people out of jobs” (Klingaman, 6A).

A traditionalist, Griffith was not persuaded, partly owing to the profitability of renting his stadium to Negro league teams. Nevertheless, the historian Brad Snyder observes that the meeting with Griffith “marked the beginning of Lacy’s campaign to integrate baseball in Washington,” and Lacy began to publish a column in the weekly Washington Tribune titled “Pro and Con on the Negro in Organized Baseball” (Snyder, 77). Lacy also argued, sometimes didactically, that black ballplayers and those who ran the Negro leagues needed to be more professional if they were to compete in the major leagues.

In 1940, after a series of disputes with the management of the Washington Afro-American, which had bought and absorbed the Tribune, Lacy left his wife and young son in Washington and moved to Chicago, where he soon became assistant national editor for the Chicago Defender, one of the nation’s largest and most influential black papers. While he did not cover sports for the Defender, Lacy continued to fight for the integration of professional baseball by intensifying “an already aggressive and voluminous letter campaign directed at major league owners and particularly Commissioner [Kenesaw Mountain] Landis” (Dictionary of Literary Biography, vol. 171, 1996, 176). Late in 1943 Landis relented and allowed Lacy to bring a small delegation to speak to the owners at their annual winter meeting. Unfortunately, Lacy was upstaged by the publisher of the Chicago Defender and by the famous actor-singer PAUL ROBESON and never got to make his case.

Shortly thereafter, a disappointed Lacy became columnist and sports editor for the weekly Baltimore Afro-American, a position he held for almost sixty years. Indefatigable, Lacy continued to crusade for the integration of professional baseball in his column and behind the scenes. In March 1945, after Landis died, Lacy wrote to every major league owner suggesting the creation of a committee to reconsider the integration of baseball. Lacy presented his proposal, and the executives agreed to his plan. The Major League Committee on Baseball Integration was established, including Lacy, Branch Rickey of the Brooklyn Dodgers, and Larry MacPhail of the New York Yankees. The committee never met, however, largely because of MacPhail’s foot-dragging. Nonetheless, Rickey and JACKIE ROBINSON made history in August 1945, when the latter signed with the Dodgers.

After Robinson made the majors in 1947, Lacy was his close companion for three years. Lacy “chronicled Robinson’s first day in the majors, naming those who sat beside him on the Dodgers bench—and how close they sat. He cataloged the insults and debris hurled Robinson’s way. He counted brushback pitches. He timed applause. He reported every pulled muscle, broken nail and silver hair on Robinson’s prematurely gray head” (Klinga-man, 6A). Traveling all over the country with Robinson and other black sportswriters, Lacy suffered numerous racist indignities, yet kept them to himself.

In addition to crusading for the integration of baseball, Lacy wrote about auto and horse racing, boxing, college and professional basketball and football, golf, the Olympics, tennis, and track and field, amounting to roughly three thousand columns in all. A man with an acute sense of fairness, he wrote about racism in accommodations and employment practices, the exploitation of African American student athletes, and numerous other examples of discrimination and injustice.

More than a reporter, Lacy used his sports column to reflect on and to improve the world in which he lived and tried to do something about improving it. He was “a drum major for change—the broad, sweeping sort of social change that helps legitimize this nation’s claim to greatness long before the best-recognized civil-rights activists came on the scene. Given baseball’s popularity in the ’40s, the opening [Lacy helped forge] shattered the myth of white superiority and made it possible for other race-based barriers to crumble” (Wickham, 13A). Lacy won many awards and accolades, including the prestigious 1997 J. G. Taylor Spink Award for meritorious contributions to baseball writing, which earned him a place in the writers’ wing of the Baseball Hall of Fame in 1998. Lacy was only the second African American so honored. At a gathering in his honor in 2002, Lacy was lauded by Baltimore’s mayor, Martin O’Malley, “for challenging the American conscience and demanding that we live up to our promise as a people” (Kane 3B).

Though some said he became something of a curmudgeon in his later years, Lacy was a soft-spoken, humble man. “In the case of baseball integration, I just happened to be in the right place at the right time,” Lacy observed. “I think that anyone else situated as I was and possessing a bit of curiosity and concern about progress would have done the same thing” (Lacy, 209). Be that as it may, the sports columnist Michael Wilbon convincingly argues, “You can’t write the history of sports and race in America without devoting a chapter to Sam Lacy” (“Lacy’s Towering Legacy,” Washington Post, 11 May 2003).

Lacy, Sam, with Moses J. Newson. Fighting for Fairness: The Life Story of Hall of Fame Sportswriter Sam Lacy (1998).

Fimrite, Ron. “Sam Lacy: Black Crusader,” Sports Illustrated, 29 Oct. 1990.

Kane, Gregory. “A Group of Sports Legends Gathers to Honor the Greatest of Them All,” Baltimore Sun, 6 Oct. 2002.

Klingaman, Mike. “Hall of Fame Opens Door for Writer,” Baltimore Sun, 26 July 1998.

Snyder, Brad. Beyond the Shadows of the Senators: The Untold Story of the Homestead Grays and the Integration of Baseball (2003).

Wickham, DeWayne. “Journalist’s Induction into Hall Long Overdue.” USA Today, 30 July 1998, 13A.

Obituaries: Baltimore Afro-American, 17–23, May 2003; Baltimore Sun and Washington Post, 10 May 2003; New York Times, 12 May 2003; Sports Illustrated, 19 May 2003.

—DANIEL A. NATHAN

LAMPKIN, DAISY

LAMPKIN, DAISY(1880s–Mar. 10 1965), civil rights and women’s suffrage advocate and NAACP leader, was born Daisy Elizabeth Adams, the only child of George S. Adams and Rosa Ann Proctor. Sources differ as to the exact date and place of her birth. Lampkin’s obituary in the New York Times states that she was 83 years of age at the time of her death in 1965, which places her birth in either 1881 or 1882. Other sources claim that Daisy was born on 9 August 1888. It is also uncertain whether she was born in Washington, D.C., or Reading, Pennsylvania, but she completed high school in the latter city before moving to Pittsburgh in 1909. In 1912 she helped organize a gathering for the woman’s suffrage movement and joined the Lucy Stone League, an organization connected with the suffrage movement. She became president of the league in 1925 and headed the organization for the next forty years.

In 1912 Daisy Adams married William Lampkin, originally from Rome, Georgia, who ran a restaurant in one of Pittsburgh’s wealthy suburbs. During the first years of her marriage, Lampkin worked with her husband in the restaurant business and expanded her activities as a community activist. She made street-corner speeches to mobilize African American women into political clubs, organized black housewives around consumer issues, and was a leading participant in a Liberty Bond drive during World War I, when, as the scholar Edna Chappell McKenzie notes, the black community of Allegheny County, where Pittsburgh is located, raised more than two million dollars. She also served on the staff of the Pittsburgh Urban League.

Impressed with Lampkin’s talents as a fund-raiser, Robert L. Vann, editor and publisher of the Pittsburgh Courier, solicited Lampkin’s help when he was trying to raise money during the early days of the Courier. She continued to work for the newspaper in the 1920s and was made vice president in 1929, a position she held for thirty-six years, until her death in 1965.

During and after World War I, Lampkin’s activism among black women shaped the black freedom struggle at both local and national levels. She was chair of the Allegheny County Negro Women’s Republican League and vice-chair of the Negro Voters League. At the national level, she was elected president of the Negro Women’s Equal Franchise Federation, founded in 1911; she served as a national organizer and chair of the executive board of the National Association of Colored Women (NACW) and helped organize, with MARY MCLEOD BETHUNE, the National Council of Negro Women.

By the early 1920s, Lampkin was a prominent figure in black politics and served as president of the National Colored Republican Conference. In 1924 she was the only woman selected by NAACP national secretary JAMES WELDON JOHNSON to attend a meeting of black leaders with President Calvin Coolidge at the White House; the meeting was to protest the injustice meted out to African American soldiers allegedly involved in the 1917 Houston riot. She was also elected an alternate delegate at large to the national Republican Party convention in 1926, a remarkable achievement for any black person or any woman at that time, as historian Edna McKenzie notes.

When Lampkin joined the staff of the NAACP in 1927, she linked her championing of black women with that of the NAACP’s agenda, focusing on breaking down barriers to full participation in American society. She served as regional field secretary in the early 1930s; became known as an unflappable, intrepid fund-raiser for the association; and was appointed national field secretary by the NAACP’s board of directors in 1935. Using her skills as an organizer and superb speaker, Lampkin worked with black workers during the economic hard times of the 1930s, increasing the NAACP’s membership in key cities, such as Chicago and Detroit. She not only revitalized the organization’s sagging enrollment but also used her national position and prestige to push the NAACP toward a new approach for attaining civil rights in America.

Lampkin increased NAACP membership at a moment when the association faced perhaps its most severe challenges from both within and without. Within the organization, dissent centered on the fact that the NAACP was not reaching the mass of African Americans. As the Depression deepened in the early 1930s, thousands of African Americans organized themselves through unemployed councils, participated in rent strikes, and joined the CIO’s rank-and-file industrial unions that were encouraged by President Franklin Roosevelt’s New Deal. Some of their actions were encouraged and led by Communist Party organizers, others by groups such as A. PHILIP RANDOLPH’s Brotherhood of Sleeping Car Porters. Missing from efforts to mobilize the grass roots was the NAACP, which committed its resources to making appeals in courts on a case-by-case basis and agitated by compiling facts and deluging government officials with information.

Since its founding in 1909, the NAACP had pursued a gradual, legalistic approach to securing African Americans their full citizenship rights. The NAACP’s leadership expressed little interest in mass organization of black workers. In 1931, the American Communist Party (CPUSA) challenged the NAACP’s narrow agenda by taking on the legal defense of the SCOTTSBORO BOYS, nine working-class African American males who were charged in Scottsboro, Alabama, with the alleged rape of two white women. Because the NAACP had initially refused to take on the Scottsboro Boys case, the Communists convinced at least some African Americans that their Party was more in touch with the mood and interests of working-class blacks than the NAACP. Although the CPUSA did not win massive numbers of black converts, their militant approach forced black organizations, and the NAACP, in particular, to rethink their strategy in challenging racial inequality. The competition between the Communists and the NAACP, historian Mark Naison has argued, was not just for control over the Scottsboro case but also for the “hearts and minds of the black public” (Communists in Harlem during the Depression [1985], 62).

As funding from white philanthropists dried up, the NAACP needed to increase its membership within the black community. Daisy Lampkin understood well the threat that Scottsboro posed for the NAACP, and she also had a solution. “The NAACP is being openly criticized by its own members,” Lampkin wrote to WALTER WHITE, executive secretary of the NAACP, in 1933. “Some frankly say,” she continued, “that the NAACP is less militant” than it used to be. Moreover, Lampkin told White, friends of the NAACP asked her whether she thought the NAACP had outlived its usefulness and whether the time had come for it to give way to another organization with a more “militant program.” She advised both Walter White and his assistant, ROY WILKINS, to initiate a more aggressive program in order to meet the “onslaught of the Communists” (Letter from Roy Wilkins to Daisy E. Lampkin, 23 Mar. 1935, I-C-80, NAACP Papers, Library of Congress).

Lampkin demonstrated her independence as a leader within the NAACP on another occasion in 1933. A planned boycott of discriminatory practices by the Sears Roebuck shoe department by “prominent women” in the Chicago branch of the NAACP was aborted by from the national office. Walter White was concerned lest the proposed boycott sully the reputation of the NAACP in the eyes of William Rosenwald, chairman of the board of Sears, whose stock funded the Rosenwald Fund, a major contributor to projects benefiting black Americans. Such concerns did not faze the NACW. When the association met in Chicago in July 1933 for its annual convention, it condemned Sears for its discriminatory policies. Lampkin, running for vice president of the NACW at the time, strongly endorsed the resolution against Sears, which also urged “widespread publicity on the matter” (letter from A. C. MacNeal to Walter White, 29 July 29 1933, I-G-51, NAACP Papers, Library of Congress).

Perhaps to underscore her concern with the passive approach of the NAACP on this matter, Lampkin, regional field secretary at the time, did not visit the Chicago branch while attending the NACW convention, a slight that led the branch president to complain to White. As Lampkin reminded White in a letter of 22 October 1936, it was because of her influence in the “largest organization of colored women in America” that she was important to the staff of the NAACP. The public was well aware, she said, of her “many other interests,” which “account to a very large degree for the success I have in getting people to work with me in campaigns for the NAACP” (NAACP papers, Library of Congress, I-C-68).

By the end of the 1930s, the NAACP had expanded its program to reach the masses of the people, following advice that Lampkin had offered to Walter White and Roy Wilkins, in the early 1930s. Lampkin continued to work tirelessly for the NAACP until October 1964, when she collapsed from exhaustion after making yet another strenuous fund-raising appeal for the NAACP. She died a few months later, in March 1965, and was survived by her husband.

The life of Daisy Lampkin exemplifies the important role black women played in twentieth century campaigns for civil rights. Although Lampkin was best known nationally for her role as a prominent NAACP leader, her contribution to the larger freedom struggles for racial and gender equality extended far beyond that organization. Whatever the venue, the impulse that drove Lampkin’s life was to remove barriers that kept African Americans from the full enjoyment of their citizenship rights.

Bates, Beth Tompkins. “A New Crowd Challenges the Agenda of the Old Guard in the NAACP, 1933–1941,” American Historical Review 102.2 (Apr. 1997).

_______ Pullman Porters and the Rise of Protest Politics in Black America, 1925–1945 (2001).

McKenzie, Edna B. “Daisy Lampkin: A Life of Love and Service.” Pennsylvania Heritage (Summer 1983).

Trotter, Joe William, Jr. River Jordan: African American Urban Life in the Ohio Valley (1988).

Obituary: New York Times, Mar. 12, 1965: 33.

—BETH TOMPKINS BATES

LANE, WILLIAM HENRY

LANE, WILLIAM HENRY(1825?–1852), dancer, also known as “Master Juba,” is believed to have been born a free man, although neither his place of birth nor the names of his parents are known. He grew up in lower Manhattan in New York City, where he learned to dance from “Uncle” Jim Lowe, an African American jig-and-reel dancer of exceptional skill.

By the age of fifteen, Lane was performing in notorious “dance houses” and dance establishments in the Five-Points district of lower Manhattan. Located at the intersection of Cross, Anthony, Little Water, Orange, and Mulberry streets, its thoroughfare was lined with brothels and saloons occupied largely by free blacks and indigent Irish immigrants. Lane lived and worked in the Five-Points district in the early 1840s. In such surroundings, the blending of African American vernacular dance with the Irish jig was inevitable. Marshall Stearns in Jazz Dance (1968) confirms that “Lane was a dancer of ‘jigs’ at a time when the word was adding to its original meaning, an Irish folk dance, and being used to describe the general style of Negro dancing.” Charles Dickens, in his American Notes (1842), describes a visit to the Five-Points district in which he witnessed a performance by a dancer who was probably Lane: “Single shuffle, double shuffle, cut and cross cut; snapping his fingers, rolling his eyes, turning in his knees, presenting the backs of his legs in front, spinning about on his toes and heels like nothing but the man’s fingers on the tambourine; dancing with two left legs, two right legs, two wooden legs, two wire legs, two spring legs.”

In 1844, after beating the reigning white minstrel dancer, John Diamond, in a series of challenge dances, Lane was hailed as the “King of All Dancers” and named “Master Juba,” after the African juba or gioube, a step-dance resembling a jig with elaborate variations. The name was often given to slaves who were dancers and musicians. Lane was thereafter adopted by an entire corps of white minstrel players who unreservedly acknowledged his talents. On a tour in New England with the Georgia Champion Minstrels, Lane was billed as “The Wonder of the World Juba, Acknowledged to be the Greatest Dancer in the World!” He was praised for his execution of steps, unsurpassed in grace and endurance, and popular for his skillful imitations of well-known minstrel dancers and their specialty steps. He also performed his own specialty steps, which no one could copy, and he was a first-rate singer and a tambourine virtuoso. In 1845 Lane had the unprecedented distinction of touring with the four-member, all-white Ethiopian Minstrels, with whom he received top billing. At the same time, he prospered as a solo variety performer and from 1846 to 1848 was a regular attraction at White’s Melodeon in New York.

Lane traveled to London with Pell’s Ethiopian Serenaders in 1848, enthralling the English, who were discerning judges of traditional jigs and clogs, with “the manner in which he beat time with his feet, and the extraordinary command he possessed over them.” London’s Theatrical Times wrote that Master Juba was “far above the common [performers] who give imitations of American and Negro character; there is an ideality in what he does that makes his efforts at once grotesque and poetical, without losing sight of the reality of representation.” Working day and night and living on a poor diet and no rest, Lane died of exhaustion in London.

In England, Lane popularized American minstrel dancing, influencing English clowns who added jumps, splits, and cabrioles to their entrées and began using blackface makeup. Between 1860 and 1865, the Juba character was taken to France by touring British circuses and later became a fixture in French and Belgian cirques et carrousels. The image of the blackface clown that persisted in European circuses and fairs continued to be represented in turn-of-the-century popular entertainments as well as on concert stages during the 1920s, in ballets such as Léonide Massine’s Crescendo, Bronislawa Nijinska’s Jazz, and George Balanchine’s “Snowball” in The Triumph of Neptune (1926).

In the United States, Lane is considered by scholars of dance and historians of the minstrel as the most influential single performer in nineteenth-century American dance. He kept the minstrel show in touch with its African American source material at a time when the stage was dominated by white performers offering theatrical derivatives and grotesque exaggerations of the African American performer. He established a performing style and developed a technique of tap dancing that would be widely imitated. For example, the white dancer Richard M. Carroll was noted for dancing in the style of Lane and earned a reputation for being a great all-around performer; other dancers, like Ralph Keeler, who starred in a riverboat company before the Civil War, learned to dance by practicing the complicated shuffle of Juba. Toward the end of the twentieth century, Lane’s legacy continued to be present in elements of the tap dance repertory. Lane’s grafting of African rhythms and loose body styling onto the exacting techniques of British jig and clog dancing created a new rhythmic blend of percussive dance that was the earliest form of American tap dance.

Stearns, Marshall, and Jean Stearns. Jazz Dance: The Story of American Vernacular Dance (1968).

Winter, Marian Hannah. “Juba and American Minstrelsy” in Chronicles of the American Dance, ed. Paul Magriel (1948).

—CONSTANCE VALIS HILL

LANEY, LUCY CRAFT

LANEY, LUCY CRAFT(13 Apr. 1854–23 Oct. 1933), educator, was born in Macon, Georgia, the daughter of David Laney and Louisa (maiden name unknown). Both parents were slaves: they belonged to different masters, but following their marriage they were permitted to live together in a home of their own. David Laney was a carpenter and often hired out by his owner, Mr. Cobbs. Louisa, purchased from a group of nomadic Indians while a small child, was a maid in the Campbell household. One of Lucy Laney’s most cherished memories was “how her father would, after a week of hard slave work, walk for over twenty miles… to be at home with his wife and children on the Sabbath” (Crisis, June 1934). After the Civil War and emancipation, David Laney, who had served as a slave lay preacher, was ordained as a Presbyterian minister and became pastor of the Washington Avenue Church in Macon, Georgia. Louisa remained in the Campbell’s house as a wage earner. The Laneys’ newfound income provided the family some comforts that they shared with numerous cousins, orphaned children, and others in need of shelter.

When missionary teachers opened a school in Macon in 1865 Lucy Laney, together with her mother and her siblings, was among the first to enroll. She graduated from the Lewis High School in 1869 and entered Atlanta University where she received a certificate of graduation from the Higher Normal Department in 1873. In keeping with her strong conviction that “becoming educated [was] a perpetual motion affair” (Abbott’s Monthly, June 1931), over the course of her career she enrolled in summer programs at the University of Chicago, Hampton Institute, Columbia University, and Tuskegee Institute.

Laney was keenly aware of all the advantages life had afforded her, and she believed that of those to whom much is given much is expected. Emancipation had ushered in new opportunities and responsibilities, and early in life she dedicated herself to her race’s advancement. Based on her study of American history, she concluded that the four major components of a realistic program for the “uplift” of blacks were political power, Christian training, “cash,” and education. She viewed education as the key to achieving the first three objectives. Her decision to become a teacher was also dictated by the limited employment opportunities available to black women. Following graduation from Atlanta University she accepted a teaching position in Milledgeville, Georgia, and between 1873 and 1883 also taught at schools in Macon, Augusta, and Savannah.

While a student Laney had serious misgivings about the pedagogical practices at the various schools she attended. She had advised her teachers then that “some day I will have a school of my own.” Her experience as a teacher in the public school system intensified her desire to establish a school. She had little patience with “dull teachers . . . [who] failed to know their pupils—to find out their real needs—and hence had no cause to study methods of better and best development of the boys and girls under their care.” She deplored instructors who underestimated “the capabilities and possibilities” of black students and who did not know and/or teach African American history (“The Burden of the Educated Colored Woman,” 1899). Moreover, she was convinced that black children needed a thorough Christian education and was disturbed by the public school’s failure to address moral and religious concerns.

Laney was one of the first educators to recognize the special and urgent needs of black women in light of their central role in the education of their children. She was convinced that ignorance, immorality, and crime among blacks and perhaps some of the prejudice against them were their “inheritance from slavery.” In her opinion, “the basic rock of true culture” was the home, but during slavery “the home was… utterly disregarded… [the] father had neither responsibility, nor authority; mother, neither cares nor duties” (“Educated Colored Woman,” 1899). The disregard for homemaking and the home environment resulted in untidy and filthy homes that produced children of dubious character. Moreover, the absence of the sanctity of the marriage vow encouraged immorality and disrespect for black women.

While “no person [was] responsible for [their] ancestor’s… sins and shortcomings,” Laney argued that “every woman can see to it that she give to her progeny a good mother and an honorable ancestry.” Strengthening the black family and improving its home life was therefore “the place to take the proverbial stitch in time.” In addition to their role as wives and mothers, she believed that women were “by nature fitted for teaching the . . . young” and thus were best suited as teachers in the public school system. She was equally convinced that the teacher “who would mould character must herself possess it” and that those who would be mothers, teachers, and leaders needed to be capable in both “mind and character” (“Address before the Women’s Meeting,” 1897).

Laney’s conviction that educated women were a prerequisite for advancement of her race was the major impetus for the founding of the Haines Normal and Industrial Institute. She began her school with six students in the basement of Christ Presbyterian Church in Augusta, Georgia, on 6 January 1886. During the following three years the school, due to increasing enrollment, was moved to various rented buildings around the city. Haines Institute was chartered by the state of Georgia as a normal and industrial school on 5 May 1888. Although the school was sanctioned by the Presbyterian board, the general assembly provided only moral support, which Laney noted “was not much to go on.” In 1889, however, the board purchased a permanent site for the school and erected the institution’s first building. Despite numerous problems, by 1887 primary, grammar, and normal divisions had been established, and by 1889 she was able to develop a strong literary department as well as a scientifically based normal program and industrial course. By 1892 Haines Normal and Industrial Institute was recognized as one of the best schools of its type in the nation. John William Gibson and William H. Crogman said of Laney in their classic study, The Progress of a Race (1897), “There is probably no one of all the educators of the colored race who stands higher, or who has done more work in pushing forward the education of the Negro woman.”

Laney was the foremost female member of the generation born into slavery and educated during Reconstruction who rose to leadership and prominence in the 1880s and 1890s. In addition to being a national race leader, she was a pioneer in the struggles for Prohibition and women’s rights as well as in the black women’s club movement. She was instrumental in establishing the first public high school for blacks in Georgia, organizing the Augusta Colored Hospital and Nurses Training School, and founding the first kindergarten in the city of Augusta. She was also a leader in the battle to secure improved public schools, sanitation, and other municipal services in Augusta’s black community. She was a founding member of the Georgia State Teacher Association and a leader within the regional and national politics of the Young Women’s Christian Association. She chaired the Colored Section of the Interracial Commission of Augusta and served on the National Interracial Commission of the Presbyterian Church. An eloquent speaker, she was a distinguished member of the lecture circuit between 1879 and 1930. A number of articles by and about Laney and her school appeared in Presbyterian church publications such as the Home Mission Monthly, the Church Home and Abroad, Women and Mission, the Presbyterian Monthly Record, and the Presbyterian Magazine during the years 1886–1933.

Laney, who often stated that she wanted to “wear out, not rust out,” died in Augusta, Georgia, and was buried on the campus of the school that she built and to which she had devoted most of her life. The most enduring epithet for Laney, who never married or had children, was “mother of the children of the people,” and her most profound contributions were the men and women she educated. Writing in the April 1907 issue of the Home Mission Monthly she argued that “the measure of an institution is the men and women it sends into the world. The measure of a man is the service he renders his fellows.” Judging by this standard Lucy Craft Laney and the school she established were eminently successful.

Materials regarding Laney are in the Presbyterian Historical Society in Philadelphia and the William E. Harman Collection, Library of Congress.

Brawley, Benjamin. Negro Builders and Heroes (1937).

Daniel, Sadie loia. Women Builders (1931).

Griggs, A. C. “Lucy Craft Laney,” Journal of Negro History (Jan. 1934): 97–102.

Notestein, Lucy Lilian. Nobody Knows the Trouble I See (n.d.).

Ovington, Mary White. Portraits in Color (1927).

Patton, June O. “Augusta’s Black Community and the Struggle for Ware High School,” in New Perspectives on Black Educational History, Vincent P. Franklin and James D. Anderson, eds. (1978).

Obituary: Augusta (Ga.) Chronicle, 23 Oct. 1933.

—JUNE O. PATTON

LANGSTON, JOHN MERCER

LANGSTON, JOHN MERCER(14 Dec. 1829–15 Nov. 1897), political leader and intellectual, was born free in Louisa County, Virginia, the son of Ralph Quarles, a wealthy white slaveholding planter, and Lucy Jane Langston, a part Native American, part black slave emancipated by Quarles in 1806. After the deaths of both of their parents in 1834, Langston and his two brothers, well provided for by Quarles’s will but unprotected by Virginia law, moved to Ohio. There Langston lived on a farm near Chillicothe with a cultured white southern family who had been friends of his father and who treated him as a son. He was in effect orphaned again in 1839, when a court hearing, concluding that his guardian’s impending move to slave-state Missouri would imperil the boy’s freedom and inheritance, forced him to leave the family. Subsequently, he boarded in four different homes, white and black, in Chillicothe and Cincinnati, worked as a farmhand and bootblack, intermittently attended privately funded black schools since blacks were barred from public schools for whites, and in August 1841 was caught up in the violent white rioting against blacks and white abolitionists in Cincinnati.

Learning from his brothers and other black community leaders a sense of commitment, Langston also developed a self-confidence that helped him cope with his personal losses and with pervasive, legally sanctioned racism. In 1844 he entered the preparatory department at Oberlin College, where his brothers had been the first black students in 1835. Oberlin’s egalitarianism encouraged him, and its rigorous rhetorical training enhanced his speaking skills. As early as 1848 and continuing into the 1860s, Langston joined in the black civil rights movement in Ohio and across the North, working as an orator and organizer to promote black advancement and enfranchisement and to combat slavery. At one Ohio state black convention, the nineteen-year-old Langston, quoting the Roman slave Terence, declared: “‘I am a man, and there is nothing of humanity, as I think, estranged to me.’… The spirit of our people must be aroused. They must feel and act as men.” After receiving his BA degree in 1849, Langston decided to study law. Discovering that law schools were unwilling to accept a black student, however, he returned to Oberlin and in 1853 became the first black graduate of its prestigious theological program. Despite evangelist and Oberlin president Charles Grandison Finney’s public urging, Langston, skeptical of organized religion, and especially its widespread failure to oppose slavery, refused to enter the ministry.

Finding white allies in radical anti-slavery politics, Langston engaged in local politics beginning in 1852, demonstrating that an articulate black campaigner might effectively counter opposition race-baiting; in mid-decade he helped form the Republican Party on the Western Reserve. Philemon E. Bliss of nearby Elyria, soon to be a Republican congressman, became Langston’s mentor for legal study, and in 1854 he was accepted to the Ohio bar, becoming the first black lawyer in the West. That year he married Caroline Matilda Wall, a senior at Oberlin; they had five children. In the spring of 1855 voters in Brownhelm, an otherwise all-white area near Oberlin where Langston had a farm, elected him township clerk on the Free Democratic (Free Soil) ticket, gaining him recognition as the first black elected official in the nation. Langston announced his conviction that political influence was “the bridle by which we can check and guide, to our advantage, the selfishness of American demagogues.”

In 1856 the Langstons began a fifteen-year residency in Oberlin. Elected repeatedly to posts on the town council and the board of education, he solidified his reputation as a competent public executive and adroit attorney. In his best-known case, Langston successfully defended EDMONIA LEWIS, a student accused of poisoning two of her Oberlin classmates (who recovered); Lewis would become the first noted African American sculptor. In promoting militant resistance to slavery, Langston helped stoke outrage over the federal prosecution under the Fugitive Slave Law of thirty-seven of his white and black townsmen and others involved in the 1858 Oberlin-Wellington rescue of fugitive slave John Price. Immediately, Langston organized the new black Ohio State Anti-Slavery Society, which he headed, to channel black indignation over the case. While his brother Charles Henry Langston, one of the two rescuers convicted, repudiated the law in a notable courtroom plea, Langston urged defiance of it in dozens of speeches throughout the state. Langston supported the plan by John Brown (1800–1859) to foment a slave uprising, although he did not participate in the 1859 raid on Harpers Ferry. Following the outbreak of the Civil War, once recruitment of northern black troops began in early 1863, he raised hundreds of black volunteers for the Massachusetts Fifty-fourth and Fifty-fifth regiments and for Ohio’s first black regiment.

After the war, Langston’s pursuit of a Reconstruction based on “impartial justice” and a redistribution of political and economic power elevated him to national prominence. In contrast to FREDERICK DOUGLASS, the quintessential self-made man, to whom his leadership was most often compared, Langston represented the importance of education and professionalism, joined to activism, for a people emerging from slavery. In 1864 the black national convention in Syracuse, New York, elected him the first president of the National Equal Rights League, a position he held until 1868. Despite rivalries within the league, Langston shaped it into the first viable national black organization. In 1865 and 1866 he lectured in the Upper South, the Midwest, and the Northeast and fought for full enfranchisement not only of the freed people, but also of African Americans denied suffrage in the North. In January 1867, on the eve of congressional Reconstruction, he presided over a league-sponsored convention of more than a hundred black delegates from seventeen states to Washington, D.C., to dramatize African American demands for full freedom and citizenship. That spring Langston assumed a signal role in the South as a Republican party organizer of black voters and the educational inspector-general for the Freedmen’s Bureau, traveling from Maryland to Texas. In Virginia, Mississippi, and North Carolina, he helped set up Republican Union Leagues, which instructed freed people on registration and voting; in Georgia and Louisiana he advised blacks elected to state constitutional conventions on strategy. In almost every southern state, Langston defended Reconstruction policy in addresses before audiences of both races. Insistent on guaranteeing the citizenship and human rights of freed people, he appealed to black self-reliance, self-respect, and self-assertion and to white enlightened self-interest, predicting that interracial cooperation would lead to an “unexampled prosperity and a superior civilization.” His charisma, refined rhetorical style, and ability to articulate radical principles in a reasonable tone drew plaudits across ideological and racial lines. Twice, in 1868 and 1872, fellow Republicans, one of whom was white, proposed that Langston run for vice president on the Republican ticket.

In the fall of 1869 Langston founded the Law Department at Howard University and took up his duties as law professor and first law dean. From December 1873 to July 1875 he was vice president and acting president of the university. He characteristically gained a warm following among students, who were particularly attracted by his manner, which was neither obsequious nor condescending. Despite Langston’s accomplishments at Howard, however, the trustees rejected his bid to assume the presidency for reasons that they refused to disclose but that clearly involved his race, his egalitarian and biracial vision, and the fact that he was not a member of an evangelical church. Embittered, he resigned.

Meanwhile Langston continued to function as one of the Republican Party’s top black spokesmen. In return, President Ulysses S. Grant appointed him to the Board of Health of the District of Columbia in 1871, and he moved his home from Oberlin to Washington, D.C. He served as the board’s legal officer for nearly seven years, during which time he helped devise a model sanitation code for the capital. On another front, at the behest of Massachusetts senator Charles Sumner, he contributed to the drafting of the Supplementary Civil Rights Act of 1875, which was invalidated by the U.S. Supreme Court in 1883. As radical Reconstruction crumbled, practicality and personal ambition led Langston in 1877 to endorse President Rutherford B. Hayes’s conciliatory policy toward the white South. Two years later, however, he condemned the condition of the freedpeople in the South as “practical enslavement” and called for black migration, the “Exodus” movement, to the North and the West. Langston served with typical efficiency as U.S. minister and consul general to Haiti from 1877 to 1885, winning settlement of claims against the Haitian government, especially by Americans injured during civil unrest, and some improvement in trade relations between the two countries. During his final sixteen months of duty, he was concurrently chargé d’affaires to Santo Domingo.

In 1885 Langston returned to Petersburg, Virginia, to head the state college for African Americans, the Virginia Normal and Collegiate Institute. After his forced resignation less than two years later under heavy pressure from the Democrats who then controlled the state, he announced his intention to run for the U.S. House of Representatives in the mostly black Fourth District, of which Petersburg was the urban center. Running against a white Democrat and a white Republican, Langston waged a ten-month campaign “to establish the manhood, honor, and fidelity of the Negro race.” Although the Democratic candidate was initially declared the victor, Langston challenged the election results as fraudulent, and Congress voted in September 1890 to seat him. Within days he was back in Virginia campaigning for reelection to a second term. Again the official count went to the Democrat, a result Langston accepted because he could expect no redress from the new Democratic Congress. The first African American elected to Congress from Virginia, Langston used his three months in the House to put his ideas on education and fair elections into the national record. His most controversial proposal, one intended to head off black disfranchisement, was a constitutional amendment imposing a literacy requirement on all voters in federal elections and a corresponding adjustment in the size of state congressional delegations.

During the remainder of his life, Langston practiced law in the District of Columbia and continued to be active in politics, education, and promoting black rights. He published his autobiography, From the Virginia Plantation to the National Capitol (1894), and carried on an active speaking schedule in both the North and the South. He remained hopeful despite legal disfranchisement, segregation, and his own failure to obtain a federal judgeship. In 1896, while raising money to support the filing of civil rights cases, he predicted: “It is in the courts, by the law, that we shall, finally, settle all questions connected with the recognition of the rights, the equality, the full citizenship of colored Americans.” He died in Washington, D.C.

Langston’s papers, together with those of his wife, Caroline W. Langston, and son-in-law James Carroll Napier, are in the Fisk University Library. Valuable scrapbooks of newsclippings are in the Moorland-Spingarn Research Center at Howard University.

Langston, John Mercer. Freedom and Citizenship (1883; repr. 1969).

_______ From the Virginia Plantation to the National Capitol (1894).

Cheek, William, and Aimee Lee Cheek. John Mercer Langston and the Fight for Black Freedom, 1829–65 (1989).

_______ “John Mercer Langston: Principle and Politics,” in Black Leaders of the Nineteenth Century, eds. Leon Litwack and August Meier (1988).

—WILLIAM CHEEK

—AIMEE LEE CHEEK

LARSEN, NELLA

LARSEN, NELLA(13 Apr. 1891–30 Mar. 1964), novelist, was born Nellie Walker in Chicago, Illinois, the daughter of Peter Walker, a cook, and Mary Hanson. She was born to a Danish immigrant mother and a “colored” father, according to her birth certificate. On 14 July 1890 Peter Walker and Mary Hanson applied for a marriage license in Chicago, but there is no record that the marriage ever took place. Larsen told her publisher, Alfred A. Knopf, that her father was “a Negro from the Virgin Islands, formerly the Danish West Indies” and that he died when she was two, but none of this has been proven conclusively.

Larsen was prone to invent and embellish her past. Mary Hanson Walker married a Danish man, Peter Larson, on 7 February 1894, after the couple had had a daughter. Peter Larson eventually moved the family from the multiracial world of State Street to a white Chicago suburb, changed the spelling of his name to Larsen, and sent Nellie away to the South. In the 1910 census Mary Larsen denied the existence of Nellie, stating that she had given birth to only one child. The family rejection and the resulting cultural dualism over her racial heritage that Larsen experienced in her youth were to be reflected in her later fiction.

Nellie Larson entered the Coleman School in Chicago at age nine, then the Wendell Phillips Junior High School in 1905, where her name was recorded as Nellye Larson. In 1907 she was sent by Peter Larsen to complete high school at the Normal School of Fisk University in Nashville, Tennessee, where she took the spelling “Larsen” and began to use “Nella” as her given name. Larsen claimed to have spent the years 1909 to 1912 in Denmark with her mother’s relatives and to have audited courses at the University of Copenhagen, but there is no record of her ever having done so. Her biographer, Thadious M. Davis, says, “The next four years (1908–1912) are a mystery…, and no conclusive traces of her for these years have surfaced” (67).

In 1912 Larsen enrolled in a three-year nurse’s training course at New York City’s Lincoln Hospital, one of few nursing programs for African Americans in the country. After graduating in 1915, she worked a year at the John A. Andrew Hospital and Nurse Training School in Tuskegee, Alabama. Unhappy at Tuskegee, Larsen returned to New York and worked briefly as a staff member of the city Department of Health. In May 1919 she married Dr. ELMER IMES, a prominent black physicist; the marriage ended in divorce in 1933.

Larsen left nursing in 1921 to become a librarian, beginning work with the New York Public Library in January 1922. Because of her husband’s social position, Larsen was able to move in the heights of the Harlem social circle, and it is there she met WALTER WHITE, the NAACP leader and novelist, and Carl Van Vechten, the photographer and author of Nigger Heaven (1926). White and Van Vechten encouraged her to write, and in January 1926 Larsen quit her job in order to write full-time. She had already begun working on her first novel, Quicksand, perhaps during a period of convalescence, and it was published in 1928. Earlier in the 1920s she had published two children’s stories in The Brownies’ Book as Nella Larsen Imes and then two pulp-fiction stories for Young’s Magazine under the pseudonym Allen Semi. Quicksand won the Harmon Foundation’s Bronze Medal for literature and established Larsen as one of the prominent writers of the Harlem Renaissance. After her second novel, Passing, was published in 1929, she applied for and became the first black woman to receive a Guggenheim Foundation Fellowship. Larsen used the award to travel to Spain in 1930 and to work on her third book, which was never published. After a year and a half in Spain and France, Larsen returned to New York.

Nella Larsen, whose novels address the complexity of being of mixed race in America. Library of Congress

Two shocks appear to have ended Larsen’s literary career. In 1930 she was accused of plagiarizing her short story “Sanctuary,” published that year in Forum, when a reader pointed out its likeness to Sheila Kaye-Smith’s “Mrs. Adis,” a story that had appeared in Century magazine in 1922. The editors of Forum pursued the charge and exonerated Larsen, but biographers and scholars have concluded that Larsen never recovered from the attack, however unfounded. The second shock was Larsen’s discovery of her husband’s infidelity early in 1930, although she refrained from seeking a divorce until 1933. Imes supported Larsen with alimony payments until his death in 1941, at which time Larsen returned to her first career, nursing, in New York City. She was a supervisor at Gouverneur Hospital from 1944 to 1961, and then worked at Metropolitan Hospital from 1961 to 1964 to avoid retirement. Since her death in New York City, Larsen’s novels, considered “lost” until the 1970s, have been reprinted and reexamined. While she had always been included in the few histories of black American literature, her reputation was eclipsed in the era of naturalism and protest-writing (1930–1970), to be recovered along with the reputations of ZORA NEALE HURSTON and other African American women writers during the rise of the feminist movement in the 1970s.

Larsen’s literary reputation rests on the achievement of her two novels of the late 1920s. In Quicksand she created an autobiographical protagonist, Helga Crane, the illegitimate daughter of a Danish immigrant mother and a black father who was a gambler and deserted the mother. Crane hates white society, from which she feels excluded by her black skin; she also despises the black bourgeoisie, partly because she is not from one of its families and partly for its racial hypocrisy about the color line and its puritanical moral and aesthetic code. After two years of living in Denmark, Helga returns to America to fall into “quicksand” by marrying an uneducated, animalistic black preacher who takes her to a rural southern town and keeps her pregnant until she is on the edge of death from exhaustion.

In Passing Larsen wrote a complicated psychological version of a favorite theme in African American literature. Clare Kendry has hidden her black blood from the white racist she has married. The novel ends with Clare’s sudden death as she either plunges or is pushed out of a window by Irene, her best friend, just at the husband’s surprise entrance. “What happened next, Irene Redfield never afterwards allowed herself to remember. Never clearly. One moment Clare had been there, a vital glowing thing, like a flame of red and gold. The next she was gone” (271).

Larsen’s stature as a novelist continues to grow. She portrays black women convincingly and without the simplification of stereotype. Larsen fully realized the complexity of being of mixed race in America and was able to render her cultural dualism artistically.

Larsen’s personal papers and books vanished from her apartment at her death, so neither a manuscript archive nor a collection of her private papers exists.

Carby, Hazel. Reconstructing Womanhood: The Emergence of the Afro-American Woman Novelist (1987).

Davis, M. Thadious. Nella Larsen, Novelist of the Harlem Renaissance: A Woman’s Life Unveiled (1994).

Larson, Charles. Invisible Darkness: Jean Toomer and Nella Larsen (1993).

Tucker, Adia C. Tragic Mulattoes, Tragic Myths (2001).

—ANN RAYSON

LATIMER, LEWIS HOWARD

LATIMER, LEWIS HOWARD(4 Sept. 1848–11 Dec. 1928), engineer and inventor, was born in Chelsea, Massachusetts, the son of George W. Latimer, a barber, and Rebecca Smith, both former slaves who escaped from Norfolk, Virginia, on 4 October 1842. When not attending Phillips Grammar School in Boston, Lewis spent much of his youth working in his father’s barber shop, as a paper-hanger, and selling the abolitionist newspaper The Liberator. Lewis’s life changed drastically when his father mysteriously disappeared in 1858. His family, placed in dire financial straits, bound out Lewis and his brothers George and William as apprentices through the Farm School, a state institution in which children worked as unpaid laborers. Upon escaping from the exploitation of the Farm School system, Lewis and his brothers returned to Boston to reunite the family. During the next few years, Latimer was able to help support his family through various odd jobs and by working as an office boy for a Boston attorney, Isaac Wright.

Late in the Civil War, Latimer enlisted in the U.S. Navy. He was assigned to the Ohio as a landsman (low level seaman) on 13 September 1864. He served until 3 July 1865, at which time he was honorably discharged from the Massasoit.

After returning from sea, Latimer began his technical career in Boston as an office boy for Crosby and Gould, patent solicitors. Through his assiduous efforts to teach himself the art of drafting, he rose to assistant draftsman and eventually to the position of chief draftsman in the mid-1870s. During this time, he met Mary Wilson Lewis, a young woman from Fall River, Massachusetts. They were married in 1873 and had two children.

During his tenure at Crosby and Gould, Latimer began to invent. His first creation, a water closet for railway cars, co-invented with W. C. Brown, was granted Letters Patent No. 147,363 on 10 February 1874. However, drafting remained his primary vocation. One of the most noteworthy projects he undertook was drafting the diagrams for Alexander Graham Bell’s telephone patent application, which was approved on 14 February 1876. In 1879 after managerial changes at Crosby and Gould, Latimer left their employment and Boston.

Latimer relocated to Bridgeport, Connecticut, initially working as a paperhanger. He eventually found part-time work making mechanical drawings at the Follandsbee Machine Shop. While drafting at the shop, he met Hiram Stevens Maxim, the chief engineer of the U.S. Electric Lighting Company. In February 1880, shortly after their first meeting, Maxim hired Latimer as his draftsman and private secretary. Latimer quickly moved up within the enterprise, and when the U.S. Electric Lighting Company moved to New York City, it placed him in charge of the production of carbon lamp filaments. Latimer was an integral member of the team that installed the company’s first commercial incandescent lighting system, in the Equitable Building in New York City in the fall of 1880. He was on hand at most of the lighting installations that were undertaken by the company, and in 1881 he began to supervise many of their incandescent and arc lighting installations.

Latimer also invented products that were fundamental to the development of the company while directing new installations for the U.S. Electric Lighting Company. In October 1880 Maxim was granted a patent for a filament that was treated with hydrocarbon vapor to equalize and standardize its resistance, a process that allowed it to burn longer than the Edison lamp filament. Latimer began working on a process to manufacture this new carbon filament, and on 17 January 1882 he was granted a patent for a new process of manufacturing carbons. This invention produced a highly resistant filament and diminished the occurrence of broken and distorted filaments that had been commonplace with prior procedures. The filament was shaped into an M, which became a noted characteristic of the Maxim lamp. Latimer patented other inventions, including two for an electric lamp and a globe support for electric lamps. These further enhanced the Maxim lamp during 1881 and 1882.

In 1881 Latimer was dispatched to London and successfully established an incandescent lamp factory for the newly founded Maxim-Weston Electric Light Company. In 1882 Latimer left this company and began working for the Olmstead Electric Lighting Company of Brooklyn as superintendent of lamp construction; at this time he created the Latimer Lamp. He later continued his work at the Acme Electric Company of New York.

In 1883 Latimer began working at the Edison Electric Light Company. He became affiliated with the engineering department in 1885, and when the legal department was formed in 1889, Latimer’s record of expert legal advice made him a requisite member of the new division. According to Latimer’s biographical sketch of himself for the Edison Pioneers, he was transferred to the department “as [a] draughtsman inspector and expert witness as to facts in the early stages of the electric lighting business. . . . [He] traveled extensively, securing witnesses’ affidavits, and early apparatus, and also testifying in a number of the basic patent cases to the advantage of his employers.” His complete knowledge of electrical technology was exemplified in his work Incandescent Electric Lighting, a Practical Description of the Edison System (1890).

Latimer continued in the legal department when the Edison General Electric Company merged with the Thomson-Houston Company to form General Electric Company in 1892. His knowledge of the electric industry became invaluable when the General Electric Company and the Westinghouse Electric Company formed the Board of Patent Control in 1896. This board was responsible for managing the cross-licensing of patents between the two companies and prosecuting infringers. Latimer was appointed to the position of chief draftsman, however his duties went far beyond drafting. He assisted inventors and others in developing their ideas. He used the vast body of knowledge he had acquired over the years in their efforts to eliminate outside competition. He remained at this position until the board was dissolved in 1911, after which Latimer put his talents to use for the law firm of Hammer and Schwartz as a patent consultant.

In 1918, when the Edison Pioneers, an organization founded to bring together for social and intellectual interaction men associated with Thomas Edison prior to 1885, was formed, Latimer was one of the twenty-nine original members. A stroke in 1924 forced him to retire from his formal position, and he spent much of his last four years engaged in two other activities that were most important in his life, art and poetry. He died at his home in Flushing, New York, which in 1995 was made a New York City landmark. Latimer was one of very few African Americans who contributed significantly to the development of American electrical technology.

Latimer’s papers are in the Lewis Howard Latimer Collection at the Queens Borough Public Library in Queens, N.Y. Copies of many of his papers are located at the Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture of the New York Public Library.

Norman, Winifred Latimer, and Lily Patterson. Lewis Latimer. Scientist (1994).

Schneider, Janet M., and Bayla Singer, eds. Blueprint for Change: The Life and Times of Lewis H. Latimer (1995).

Turner, Glennette Tilley. Lewis Howard Latimer (1991).

Obituary: Electrical World, 22 Dec. 1928.

—RAYVON DAVID FOUCHÉ

LAVEAUX, MARIE

LAVEAUX, MARIE(10 Sept. 1801–16 June 1881), voodoo queen, was born in New Orleans, Louisiana, the daughter of Charles Laveaux, a free man of color who owned a grocery store in that city, and Marguerite D’Arcantel, a free woman of color about whom very little is known, although it is rumored that she was a spiritualist or root doctor. Certain sources erroneously claim that Charles Laveaux was a prominent white planter and politician. He was not, but he was probably the illegitimate son of Don Carlos (or Charles) Trudeau, a high-ranking official in Spanish-controlled Louisiana and the first president of the New Orleans city council when the United States purchased Louisiana in 1803. The historical record, which in Marie Laveaux’s case is exceptionally imprecise, provides several spellings of her surname, often leaving out the “x,” but most archival records suggest that Charles Laveaux used that version of his name and that this spelling was also used in records related to his illiterate daughter.

There is considerable doubt, too, about Laveaux’s date of birth. Her 1881 death certificate claims that she died at the age of ninety-eight, suggesting that she was born in 1783, although most accounts give her birth date as 1794. In the late 1990s, however, a researcher found birth and baptismal records of a “mulatto girl child” named Marie Laveaux dated September 1801. This date coincides with information on her marriage certificate, which states that Laveaux was a minor, a month shy of eighteen, when she wed Jacques Paris, a Haitian-born carpenter, in August 1819.

Laveaux’s marriage to Paris was short-lived. After her husband’s death in the early 1820s, she became known as “the widow Paris” and began a thirty-year relationship with Captain Jean Louis Christophe Duminy de Glapion, a veteran of the War of 1812 usually referred to as a “quadroon” from Santo Domingo. It has often been claimed that the couple had fifteen children, but New Orleans church records suggest that they had only two sons, François and Archange, who died in childhood, and three daughters, Marie Héloïse, Marie Louise, and Marie Phélomise. In addition, Marie Laveaux had a half-sister, also named Marie Laveaux, born to Charles Laveaux and his wife, a wealthy member of Louisiana’s free colored Creole elite. Many of the legends about the power, wealth, and infamy of Marie Laveaux have arisen because of confusion in oral and literary sources about the women who shared her name, particularly her daughter Marie Héloïse, who was also a voodoo priestess.

In the 1830s Marie Laveaux emerged as a prominent spiritualist and healer at her home; at African American ritual dances on Sundays in New Orleans’ Congo Square; and at major religious festivals, such as the midsummer St. John’s Eve celebrations on the banks of Lake Pontchartrain, which attracted people of all colors. Laveaux presided over ceremonies that blended elements of Roman Catholicism, such as the invocation of saints and the use of incense and holy water, and traditional African religious dances and rituals involving drumming, chanting, animal sacrifices, and worship of Damballa or Zombi, a snake god. The scanty record of these rituals suggests that Laveaux would blow alcohol on the faces of participants as a blessing and would also wrap a snake around their (usually naked) bodies as a symbol of her control over them. Later accounts of these ceremonies, both in oral tradition and in Robert Tallant’s Voodoo in New Orleans (1946), highlight the sexual abandon of the participants.

Laveaux’s legendary power came less from these infrequent ceremonies, however, than from her skills as an everyday spiritualist who used her charms to bewitch a highly superstitious public. Not unlike J. Edgar Hoover a century later, Laveaux understood that knowledge, particularly knowledge of private indiscretions, equals power. As a hairdresser to prominent women in New Orleans, she had access to gossip about the cit’s wealthiest and most powerful citizens. She also gained information about the New Orleans elite from African American servants and slaves who, in return for Mamzelle Marie’s spiritual protection, brought Laveaux news about their masters’ and mistresses’ financial, political, and sexual affairs. Laveaux used that intelligence to make herself indispensable to women seeking information on their husbands’ philandering, to politicians keen to learn of their opponents’ foibles, and to businessmen who relied on her charms and amulets when the hidden hand of the market failed to work its own particular gris-gris. Such information—and the spells and potions to rid her clients of what ailed them—provided Laveaux with a steady income, though not the great riches that many of her followers and detractors claimed. It also ensured friends for her in the highest places in Louisiana society, which may explain why, unlike other voodooiennes, she was never arrested. Her seeming influence over whites strengthened her influence over black Louisianans and entrenched her position in African American folklore as one of the most powerful women of her time.

Depending on the source, white accounts of Laveaux’s mid-nineteenth century heyday depict her as either saint or whore. After her death in 1881, white Catholics in New Orleans eulogized her saintly role in helping victims of yellow fever and cholera in the 1850s and her tireless work to give comfort to the city’s death-row convicts. White Catholics downplayed any African elements in Laveaux’s religion and also praised her alleged devotion to the Confederate cause. On the other hand, an obituary in the white Protestant-controlled New Orleans Democrat dismissed these claims for Laveaux’s piety, describing her as “the prime mover and soul of the indecent orgies of the ignoble Voudous” (Fandrich, 267). Other newspaper accounts and later folklore suggested that Laveaux had used her Lake Pontchartrain home, the Maison Blanche, as a brothel that served wealthy white men seeking glamorous “high yellow” prostitutes, although it is possible that these accounts confused the elder Marie with her daughter, Marie Héloïse, who reputedly kept a bawdy house.

In death Laveaux remained almost as influential as in life, at least to the thousands who seek out her tomb every year in New Orleans, which, some claim, is the second most visited grave in the United States after Elvis Presley’s. Like Presley’s followers, Laveaux’s pilgrims leave candles, money, and other objects in hope that her spirit will grant their wishes. After the September 11, 2001, terrorist attacks on New York City and Washington, D.C., and in Pennsylvania, some disciples even left notes asking that Laveaux administer punishment to the alleged perpetrator, Osama Bin Laden.

Fandrich, Ina. “The Mysterious Voodoo Queen Marie Laveaux: A Study of Power and Female Leadership in Nineteenth-Century New Orleans.” Ph.D. diss., Temple University (1994).

Raboteau, Albert. Slave Religion (1978).

Tallant, Robert. Voodoo in New Orleans (1946).

Obituary: New Orleans Daily Picayune, 17 June 1881.

—STEVEN J. NIVEN

LAWRENCE, JACOB ARMSTEAD

LAWRENCE, JACOB ARMSTEAD(7 Sept. 1917–9 June 2000), artist and teacher, was born in Atlantic City, New Jersey, to migrant parents. His father, Jacob Lawrence, a railroad cook, was from South Carolina and his mother, Rose Lee Armstead, hailed from Virginia. In 1919 the family moved to Pennsylvania, where Jacob’s sister, Geraldine, was born. Five years later, Jacob’s brother, William, was born, and his parents separated.

Jacob Lawrence moved with his mother, sister, and brother to a Manhattan apartment on West 143rd Street in 1930. Upon his arrival in Harlem, the teenage Lawrence began taking neighborhood art classes. His favorite teacher was the painter Charles Alston, who taught at the Harlem Art Workshop. This workshop, sponsored by the Works Progress Administration, was first housed in the Central Harlem branch of the New York Public Library before relocating to Alston’s studio at 306 West 141st Street. Many community cultural workers had studios in this spacious building. Affectionately called “306,” Alston’s studio in particular was a vital gathering place for creative people. Lawrence met ALAIN LOCKE, AARON DOUGLAS, LANGSTON HUGHES, CLAUDE MCKAY, RICHARD WRIGHT, and RALPH ELLISON at his mentor’s lively studio.

In 1935, at age eighteen, Lawrence started painting scenes of Harlem using poster paint and brown paper. Initially chosen for their accessibility and low cost, these humble materials would remain central to the artist’s work. The next year Lawrence began what would become his ritual of doing background research for his art projects at the 135th Street branch of the New York Public Library (now the Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture). Inspired after seeing W. E. B. DU BOIS’s play Haiti at Harlem’s Lafayette Theatre in 1936, he began researching the Haitian Revolution (1791–1804). This eye-opening research culminated in a powerful series of forty-one paintings titled The Life of Toussaint L’Ouverture. Completed in 1938, this series dramatically visualized the life of the formerly enslaved man who led the Haitian struggle for independence from France and the creation of the world’s first black republic. These paintings also signaled paths the artist would continue to explore in his work, namely, figurative expressionism, history painting, sequential narration, and prose captions. Moreover, the ambitious cycle revealed Lawrence’s deep interest in heroism and struggles for freedom.

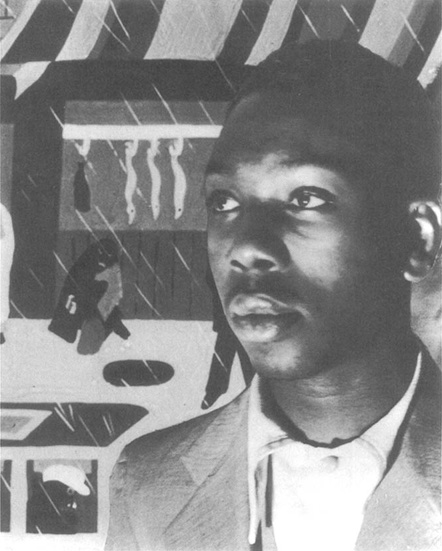

Jacob Lawrence against the backdrop of one of his paintings, at the Harlem Arts Center, 1938, in a WPA photograph. Schomburg Center

In September 1938 AUGUSTA SAVAGE, the sculptor and influential director of the Harlem Community Art Center, helped Lawrence gain work as an easel painter on the Works Progress Administration’s Federal Art Project. During his eighteen months as a government-employed artist, Lawrence probably produced about thirty-six paintings. In addition, he worked on two more dramatic biographies of freedom fighters. In 1939 he completed The Life of FREDERICK DOUGLASS series. Based on the famous abolitionist’s autobiography, the thirty-two painted panels—each accompanied by text—-chart the heroic transformation of an escaped slave into a fiery orator and an uncompromising activist. The following year Lawrence completed The Life of HARRIET TUBMAN series. Composed of thirty-one panels, this epic visual and textual narrative features the courageous female conductor of the Underground Railroad. Both series were exhibited at the Library of Congress in 1940 in commemoration of the seventy-fifth anniversary of the Thirteenth Amendment to the U.S. Constitution.

In 1941, at age twenty-four, Lawrence completed his signature narrative series, The Migration of the Negro, a group of sixty tempera paintings illustrating the mass movement of African Americans from the rural South to the urban North. This historical cycle was done in a modern visual style with its emphasis on strong lines, simplified forms, geometric shapes, flat planes, bold colors, and recurrent motifs. Gwendolyn Knight, a Barbados-born and Harlem-based artist, helped Lawrence complete the project by assisting with the preparation of the sixty hardboard panels and the accompanying prose captions. The creative couple married in New York on 24 July 1941, shortly after completing this pivotal work. Lawrence’s Migration series brought him wide public recognition and critical acclaim. Twenty-six of the panels were reproduced in Fortune magazine in November 1941. Simultaneously, New York’s prestigious Downtown Gallery exhibited the cycle, and, soon after the show opened, Edith Halpert, the gallery’s owner, asked Lawrence to join her roster of prominent American artists, which included Ben Shahn, Stuart Davis, and Charles Sheeler. Lawrence accepted Halpert’s offer, making him the first artist of African descent to be represented by a downtown gallery. A few months later the Museum of Modern Art (MOMA) purchased half the Migration series and the Phillips Collection in Washington, D.C., bought the other half, marking the first acquisition of works by an African American artist at either institution. In October 1942 MOMA organized a two-year, fifteen-venue national tour of the acclaimed series.

During World War II, Lawrence served in the U.S. Coast Guard, where he continued to paint. In 1944 a group of his paintings based on life at sea was exhibited at MOMA. The following year, while he was still on active duty, Lawrence successfully applied for a Guggenheim Fellowship to begin work on a series devoted to the crisis of war. The fourteen somber panels that make up his War series were first shown at the New Jersey State Museum in 1947, and Time magazine touted the series as “by far his best work yet” (Time 50 [22 Dec. 1947], 61).

Lawrence began his distinguished career as a teacher in 1946 when the former Bauhaus artist Josef Albers invited him to teach summer session at Black Mountain College in North Carolina. Until his retirement in 1983 Lawrence was a highly sought-after teacher. He taught at numerous schools, including the Skowhegan School of Painting and Sculpture in Maine, Brandeis University in Massachusetts, Pratt Institute, the Art Students League, and the New School for Social Research in New York City. From 1970 to 1983 Lawrence was a full professor of art at the University of Washington in Seattle.

Lawrence’s first retrospective began in 1960. Organized by the Brooklyn Museum of Art, the show traveled to sixteen sites across the country. The artist had two other traveling career retrospectives during his lifetime: one organized by the Whitney Museum of American Art in 1974, and another organized by the Seattle Art Museum in 1986.

During the civil rights movement, Lawrence visually captured the challenges of the freedom struggle of blacks in works such as Two Rebels (1963). His first venture into limited-edition printmaking, Two Rebels dramatized the struggle between black protestors and white policemen through lithography. Over the next three decades the artist would also experiment with other print-making techniques, such as drypoint, etching, and silkscreen.

In 1962, Lawrence traveled to Nigeria, where he lectured on the influence of traditional West African sculpture on modernist art and exhibited his work in Lagos and Ibadan. Two years later the artist and his wife returned to Nigeria for eight months, to experience life in West Africa and to create work based on their stay.

After working primarily as a painter and a printmaker, Lawrence expanded his range in the late 1970s by also making murals. He received his first mural commission in 1979 when he was hired to create a work for Seattle’s Kingdome Stadium. He created a ten-panel work titled Games. Made of porcelain enamel on steel, the 9½ × 7½ foot mural features powerful athletes surrounded by adoring fans. This mural, which was relocated to the Washington State Convention Center in 2000, was followed by others at Howard University (1980, 1984), the University of Washington (1984), the Orlando International Airport (1988), the Joseph Addabbo Federal Building in Queens (1988), and the Harold Washington Library Center in Chicago (1991). The artist’s final mural, a 72-foot-long mosaic commissioned by New York City’s Metropolitan Transit Authority, was posthumously unveiled in the Times Square subway station in 2001.

When Jacob Lawrence died at home in Seattle at age eighty-two, he was exploring a theme that had captured his imagination at the beginning of his sixty-five-year artistic career. Lawrence was still painting pictures of laborers, their movements and constructions, and their tools. A collection of hand tools—hammers, chisels, planes, rulers, brushes, and a Pullman porter’s bed wrench—graced his studio and inspired his work. Concerning his prized collection, the artist explained: “For me, tools became extensions of hands, and movement. Tools are like sculptures. You look at old paintings and you see in them the same tools we use today. Tools are eternal. And I also enjoy the illusion when I paint them: you know, making something that is about making something” (Kimmelman, 210–211).