LOGUEN, JERMAIN WESLEY

LOGUEN, JERMAIN WESLEY LOGUEN, JERMAIN WESLEY

LOGUEN, JERMAIN WESLEY(c. 1813–30 Sept. 1872), bishop of the African Methodist Episcopal Zion Church and abolitionist, was born Jarm Logue in Davidson County, Tennessee, the son of a slave mother, Cherry, and white slaveholder, David Logue. After David Logue sold his sister and mother to a brutal master, Jarm escaped through Kentucky and southern Indiana, aided by Quakers, and reached Hamilton, Upper Canada, about 1835. He tried his hand at farming, learned to read at the age of twenty-three, and worked as a hotel porter and lumberjack. It was in Canada that he added an n to the spelling of his name to distinguish it from that of his slave master. When creditors seized his farm in 1837, Loguen moved to Rochester, New York, and found employment as a hotel porter.

The black clergyman Elymas P. Rogers urged him to attend Beriah Green’s abolitionist school, Oneida Institute, at Whitesboro, New York. Loguen enrolled there in 1839, despite his lack of formal education. He started a school in nearby Utica for African American children and made a public profession of faith. He settled in Syracuse in 1841, opened another school, and married Caroline Storum of Busti, New York. They would have five children. One daughter, Amelia, married Lewis E. Douglass, the son of FREDERICK DOUGLASS; Gerrit Smith Loguen became an accomplished artist; and Sarah Marinda Loguen graduated from the medical school of Syracuse University in 1876.

After being ordained by the AMEZ Church in 1842, Loguen served congregations in Syracuse, Bath, Ithaca, and Troy. He gave his first speech against slavery at Plattsburgh, New York, in 1844 and was enlisted as an itinerant lecturer promoting the Liberty Party. Loguen’s sacred vocation now focused on abolitionism, and he devoted less and less time to the local ministry. Working in cooperation with Frederick Douglass of Rochester, Unitarian minister Samuel May of Syracuse, and abolitionist and reformer Gerrit Smith of Peterboro in Madison County, Loguen actively aided fugitive slaves passing through upstate New York on their way to Canada. His home became the center of Underground Railroad activity in Syracuse, and in his autobiography, A Stop on the Underground Railroad (1859), he claimed to have assisted more than 1,500 runaway slaves.

Loguen was presiding elder of the AMEZ’s Troy district when the Fugitive Slave Law of 1850 was passed. Loguen returned to Syracuse, where he publicly defied the law and vowed resistance. “I don’t respect this law,” he said, “I don’t fear it, I won’t obey it! It outlaws me, and I outlaw it, and the men who attempt to enforce it on me. I place the governmental officials on the ground that they place me. I will not live a slave, and if force is employed to re-enslave me, I shall make preparations to meet the crisis as becomes a man.” With other members of the Fugitive Aid Society, Loguen participated in the famous rescue of William “Jerry” McHenry at Syracuse in October 1851; fearing arrest for his actions, he fled to St. Catharines, Canada West, where he conducted missionary work and spoke on behalf of the temperance cause among other fugitives. Despite the failure of his appeal of 2 December 1851 for safe passage to Governor Washington Hunt of New York, Loguen returned to Syracuse in late 1852 and renewed his labors on behalf of the Underground Railroad and the local Fugitive Aid Society. Loguen was indicted by a grand jury at Buffalo, New York, but was never tried.

By the 1840s Loguen had moved away from the moral suasion philosophy of William Lloyd Garrison and into the circle of central New York abolitionists who endorsed political means. After the demise of the Liberty Party, Loguen supported a remnant known as the Liberty League. By 1854 Loguen had abandoned the nonviolent philosophy of many of his abolitionist colleagues and joined the Radical Abolition Society. After 1857 he devoted all of his time to the Fugitive Aid Society. He returned to Canada West to attend a convention led by John Brown (1800–1859) prior to the 1859 raid at Harpers Ferry but apparently did not know the details of Brown’s plan.

In the early 1860s Loguen served as pastor of Zion Church in Binghamton, New York. He also recruited black troops for the Union army. After the Civil War, Loguen was active in establishing AMEZ congregations among the southern freedmen. He had a special interest in Tennessee, where he believed his mother and sister lived. (Earlier he had refused to purchase the freedom of his mother because her master, Manasseth Logue, his father’s brother, demanded that Loguen also purchase his own freedom.) Loguen became bishop of the Fifth District of the AMEZ Church in 1868, with responsibilities for the Allegheny and Kentucky conferences. He supported the work of the Freedmen’s Bureau and the American Missionary Association in the South. On the eve of leaving for a new post as organizer of AMEZ missions on the Pacific coast, he died in Saratoga Springs, New York.

Loguen’s letters are held in the Gerrit Smith Papers, George Arents Research Library, Syracuse University, and are available on microfilm in the Black Abolitionist Papers, C. Peter Ripley, ed.

Loguen, J. W. A Stop on the Underground Railroad: Rev. J. W. Loguen & Syracuse (1859, 2001).

Hunter, Carol M. To Set the Captives Free: Reverend Jermain Wesley Loguen and the Struggle for Freedom in Central New York, 1835–1872 (1993).

Sernett, Milton C. “A Citizen of ‘No Mean City’: Jermain W. Loguen and the Antislavery Reputation of Syracuse,” Syracuse University Library Associates Courier 22 (Fall 1987): 33–55.

Obituary: Syracuse Journal, 1 Oct. 1872.

—MILTON C. SERNETT

LORDE, AUDRE

LORDE, AUDRE(18 Feb. 1934–17 Nov. 1992), poet, writer, and activist, was born Audrey Geraldine Lorde in Harlem, New York City, the youngest of three daughters of Frederic Byron Lorde, a laborer and real estate broker from Barbados, and Linda Bellmar, from Grenada, who sometimes found work as a maid. Lorde’s parents came to the United States from the Caribbean with hopes of earning enough money to return to the West Indies and start a small business. During the Depression the realization that the family was going to remain exiled in America slowly set in. Growing up in this atmosphere of disappointment had a profound impact on Lorde’s development, as questions of identity, nationality, and community membership occupied her mind.

Ironically, this woman whose living and reputation derived from her skillful use of words had to struggle as a child to acquire speech and literacy. She was so nearsighted that she was considered legally blind. Moreover, her mother feared that she might be retarded, and her first memories of school were of being disparaged for being mentally slow. Either out of fear of her mother, a severe disciplinarian, or because of an undiagnosed speech impediment, Lorde did not begin to talk until she was four years old and was uncommunicative for many years thereafter.

Lorde received her early education at two Catholic institutions in Harlem, St. Mark’s and St. Catherine’s. In her fictionalized biomythography, Zami: A New Spelling of My Name (1982), she recalls the patronizing racism of low expectations, the overt racism of bigotry, and the oppressive learning environment that stifled her creativity. The West Indian dialect and the unusual idioms that she heard at home taught her that words could be used in different and creative ways. Freedom to construct words and sentences as she chose, however, was a right that she would have to fight for. Alternate spellings of her name and the adoption of new names were merely the most visible symbols of her struggle for self-definition. If Lorde was to be a rebel and a contrarian, words would become her weapons of choice.

Lorde began writing poetry in the seventh or eighth grade. At Hunter College High School she met another aspiring poet, Diane de Prima, and they worked together on the school literary journal, Scribimus. However, when the school refused to print a love sonnet Lorde had written about her affection for a boy, she sent the poem to Seventeen magazine, where it was published. After graduating from high school in 1951, Lord worked and studied intermittently until 1959, when she received a BA degree from Hunter College. During much of the 1950s Lorde supported herself as a factory worker and an X-ray technician and in a number of other unsatisfying positions.

A pivotal experience occurred in 1954, when Lorde spent a year at the National University of Mexico. Although she had had a brief lesbian encounter while working at a factory in Connecticut, it was in Mexico that she began to free herself of the feelings of deviance that had inhibited her sexuality. When she returned to New York the next year, she immersed herself in the “gay girl” culture of Greenwich Village, and she continued to develop her craft as a member of the Harlem Writers Guild, which brought her into contact with such poets as LANGSTON HUGHES. It was also during this period that she became involved with the Beat poets Allen Ginsberg, Jack Kerouac, and LeRoi Jones (AMIRI BARAKA).

In 1961 Lorde received an MLS degree from Columbia University’s School of Library Service, and in March 1962 she married Edward Ashley Rollins, a white attorney from Brooklyn. They were married for eight years and had two children, Elizabeth and Jonathan, before divorcing in 1970. She held a number of posts at different libraries before becoming the head librarian at Town School Library in New York City, where she served from 1966 to 1968.

Lorde’s life took a dramatic turn in 1968 when she received a National Endowment for the Arts grant, resigned her position as a librarian, and accepted a post at Tougaloo College in Mississippi as poet in residence. While she was working at this historically black college, Lorde’s first book of poetry, The First Cities (1968), received critical acclaim for its effective understatement and subtlety. It was at Tougaloo College that Lorde met Frances Clayton, who would become her companion for nineteen years. Lorde’s second book, Cables to Rage (1970), captures the anger of the emerging Black Power movement and contains the poem “Martha,” in which Lorde first confirms her homosexuality in print. From this point on, Lorde observed that different groups (blacks, feminists, lesbians, and others) wanted to claim aspects of her life to aid their cause while rejecting those elements that challenged their prejudices. Of this tendency, Lorde said in an interview, “There’s always someone asking you to underline one piece of yourself—whether it’s Black, woman, mother, dyke, teacher, etc.—because that’s the piece that they need to key in to. They want to dismiss everything else. But once you do that, then you’ve lost” (Hammond, Carla M. Denver Quarterly 16, no. 1 [1981], 10–27).

During the 1970s Lorde returned to New York, where she entered a productive period of writing, teaching, and giving readings. Her third book, From a Land Where Other People Live (1973), was nominated for the National Book Award for poetry. It was followed in rapid succession by New York Head Shop and Museum (1974), Coal (1976), Between Ourselves (1976), and The Black Unicorn (1978). In these works, Lorde develops her central themes: bearing witness to the truth, transforming pain into freedom, and seizing the power to define love and beauty for oneself. Never does her work trade in clichés, employ hackneyed metaphors, or evoke saccharine sentiment. Lorde found a new voice in poetry that struck like a hammer but sounded like a bell on issues of race, gender, sexuality, and humanity.

Late in 1978, at the age of forty-four, Lorde was stricken with breast cancer. She had a mastectomy but refused to wear a prosthesis to hide the effects of the surgery. Instead, she chose to face her ordeal openly and honestly by incorporating it into her writing. In many ways The Cancer Journal (1980) helped women “come out of the closet” about this disease. Confronted with her own mortality, she published the autobiographical Zami: A New Spelling of My Name (1982), which is essentially the story of her early life, and Sister Outsider (1984), a collection of speeches and essays. In Burst of Light (1988), which won the American Book Award for nonfiction, Lorde explains that “the struggle with cancer now informs all my days, but it is only another face of that continuing battle for self-determination and survival that black women fight daily, often in triumph.” Her final book of poems, The Marvelous Arithmetics of Distance, was published posthumously in 1993.

In an effort to help other women writers, Lorde cofounded Kitchen Table: Women of Color Press in 1980. She taught courses on race and literature at Lehman College and John Jay College of Criminal Justice, and she was the Thomas Hunter Professor of English at her alma mater, Hunter College, until 1988. Lorde’s highest accolade was bestowed in 1991, when she received New York’s Walt Whitman Citation of Merit, an award given to the poet laureate of New York State.

Six years after her mastectomy Lorde was diagnosed with liver cancer. She sought treatment in America, Europe, and Africa before moving to St. Croix in the Virgin Islands with her companion, Gloria I. Joseph. Shortly before her death in November 1992 Lorde underwent an African ritual in which she was renamed Gambda Adisa, which loosely translated means, “Warrior: She Who Makes Her Meaning Known.”

Lorde, Audre. Zami: A New Spelling of My Name (1983).

Anderson, Linda R. Women and Autobiography in the Twentieth Century: Remembered Futures (1997).

Keating, AnaLouise. Women Reading Women Writing: Self-Invention in Paula Gunn Allen, Gloria Anzaldúa, and Audre Lorde (1996).

Steele, Cassie Premo. We Heal from Memory: Sexton, Lorde, Anzaldúa, and the Poetry of Witness (2000).

Obituary: New York Times, 20 Nov. 1992.

—SHOLOMO B. LEVY

LOUIS, JOE

LOUIS, JOE(13 May 1914–12 Apr. 1981), world champion boxer, was born Joseph Louis Barrow, the seventh of eight children of Munroe Barrow and Lillie Reese Barrow, sharecroppers, in a shack in Chambers County, Alabama. In 1916 his father was committed to the Searcy State Hospital for the Colored Insane, where he would live for the next twenty years. Believing that her husband had died, Lillie later married Pat Brooks and moved with their children in 1926 to Detroit, Michigan, where Brooks found a job at the Ford Motor Plant.

Like many rural southerners during the Great Migration, Joe Barrow struggled in the new urban environment. Although Alabama had been no racial paradise, Michigan seemed little better. “Nobody ever called me a nigger until I got to Detroit,” he later recalled (Ashe, 11). A rural Jim Crow education did not prepare him for the northern public schools, and the decision to place the quickly growing twelve-year-old boy in the fifth grade did not help matters. Shy and with a stutter, he paid little attention to his studies, although one teacher at his vocational school predicted that the boy “some day should be able to do something with his hands” (Ashe, 11). Detroit in the Depression provided few outlets for those hands, but Joe did find work in an automobile factory and as a laborer hauling ice. After a brief flirtation with the violin in his early teens, he took up boxing, and by failing to add his surname to his application to fight as an amateur, he was given a fighting name that stuck, “Joe Louis.” Louis lost his first amateur fight but won fifty of his next fifty-four bouts, forty-three of them by knockouts. In 1934, on his twentieth birthday, he won the National Amateur Athletic Union light-heavyweight championship and turned professional.

Louis’s amateur victories hinted at his promise, but few in the summer of 1934 expected that the gangling, 175-pound boxer would win the world heavyweight championship after only three years as a professional. That he did so was partly because of his trainer, Jack Blackburn, and his managers, Julian Black and John Roxborough, respectable black businessmen by day and numbers kingpins by night. While Blackburn worked on Louis’s conditioning and balance, Black, Roxborough, and the white promoter Mike Jacobs crafted a public image for Louis that would enhance his title prospects. Before World War I the heavyweight JACK JOHNSON had so angered whites by gloating over defeated opponents and flaunting white mistresses that no African American since had been allowed to fight for the championship. Black and Roxborough therefore urged Louis never to appear in public with white women and fed the press stories of his deep religiosity and love of family and country. Combined with a remarkable record of thirty victories in thirty-one fights, that clean-living, nonthreatening image won him a crack at the title. In June 1937 the “Brown Bomber,” as the white press had dubbed him, defeated Jim Braddock in an eighth-round knockout to win the world heavyweight championship.

At twenty-three Louis had become a hero to Depression-era blacks. While thousands of northern African Americans took to the streets to celebrate his victory, the southern black response was muted, though no less joyous. President Jimmy Carter recalled that African American neighbors came to his home to listen to the Braddock fight on one of the few radios in Plains, Georgia. Quietly obeying the racial propriety required of them, they showed no emotion at the end of the fight. But on returning to their own homes, as Carter remembers it, “pandemonium broke loose . . . as our black neighbors shouted and yelled in celebration of the Louis victory” (Sammons, 113).

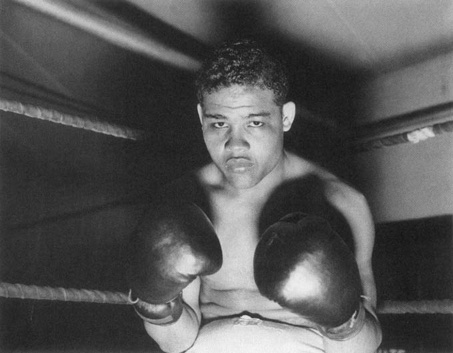

Joe Louis, in training for his 1938 match with Max Schmeling, displays the fists that earned him the nickname “Brown Bomber.” © Bettmann/CORBIS

When Louis defended his title against Max Schmeling in Yankee Stadium in June 1938, the changed international climate encouraged white Americans not only to tolerate Joe Louis but also to embrace him. The 1936 Berlin Olympics had signaled both a resurgent Germany and the willingness of white Americans to appreciate a black athlete, JESSE OWENS. In that light, the media depicted Schmeling against Louis as a battle between fascism and democracy, even though there was precious little democracy for blacks in many American states, including the boxer’s native Alabama.

Louis was goaded by racial taunts from the Schmeling camp and was particularly incensed that his only professional loss had been to the German in 1936. Asked if he was scared, he replied, “Yeah, I’m scared. I’m scared I might kill Schmeling” (Ashe, 15). Jack Blackburn often worried that Louis, for all of his finesse and strength, lacked a killer instinct, but when he knocked out Schmeling after only two minutes at Yankee Stadium, it became clear that such fears were unfounded. The Brown Bomber let loose a barrage of quick, savage left jabs and followed up with some stunning right punches to the German’s head and body, which, Louis recalled, left Schmeling squealing “like a stuck pig” (Ashe, 16). A left hook backed up by a right to the jaw knocked Schmeling to the canvas.

After that victory Louis defeated fifteen challengers between 1938 and 1941. With the exception of the quick-fisted Irish-American Billy Conn, who led on points until Louis knocked him out in the thirteenth round, most of his opponents deserved the sobriquet “bum of the month,” but no heavyweight champion had ever been so confident in his abilities as to defend his title so often. Because of the huge cut taken by his managers, however, Louis received only a fraction of the more than two million dollars that he “won” before 1942. By then he was more than $200,000 in debt to the federal government and to his promoters. The fighter’s personal life was also troubled. He had married Marva Trotter in 1935, a few hours before defeating Max Baer, and the couple would have a daughter, Jacqueline, in 1943. Louis’s frequent absences and extramarital affairs led to divorce in 1945. Although the couple remarried in 1946 and had a son, Joe Jr., in 1947, they divorced again in 1949.

In the 1940s Louis emerged as the most prominent—and, in the popular consciousness, the most significant—black figure in the American war effort. Within weeks of the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor, he contributed the entire winnings from his defeat of Buddy Baer to the Navy Relief Fund. In March 1942 he earned nationwide praise for a speech in which he urged all Americans to join the war effort because “we’re on God’s side.” Although he had misspoken—his text had read “God’s on our side”—the phrase instantly became one of the most popular slogans of the war effort. In addition to fighting (without payment) in several exhibition bouts, Sergeant Joe Louis appeared in Frank Capra’s The Negro Soldier, a morale-boosting documentary feature that proved as popular among whites as blacks. Louis was not, however, immune to racism within the American military. At an army camp in Alabama military police ordered Louis and the young boxer SUGAR RAY ROBINSON to sit in the assigned “colored” waiting area for a bus; they refused, were arrested, and were released only when Louis threatened to call contacts in the U.S. War Department. Louis also used his relative influence in Washington, D.C., to highlight the continued discrimination against blacks in the military.

Louis’s physical prowess diminished considerably after the war, and in March 1949 he retired after an unprecedented twelve years as heavyweight champion. In the decades that followed, he focused on ways to meet his massive debts, including considerable back taxes. Sadly, but inevitably, this involved a return to the ring in 1950, where he lost to the reigning champion Ezzard Charles in 1950. Knocked out by Rocky Marciano in 1951, Louis retired for good. His latter years were spent fighting the IRS, a battle won only after his fourth wife, Martha Malone Jefferson, an attorney, convinced the government that he simply did not have any money. In 1966 Louis moved to Las Vegas, where he worked variously as a greeter in a casino and, ironically, as a debt collector. In his final decade he struggled with cocaine addiction, heart disease, and depression.

On 12 April 1981, one day after attending a world heavyweight championship match, Louis died of a massive heart attack. He was survived by Jacqueline and Joe Jr., children from his first marriage, by his fourth wife, Martha Jefferson, and by four children whom he and Jefferson had adopted. Thousands attended his lying in state at Caesars Palace in Las Vegas, and President Ronald Reagan, who had starred with Louis in the 1943 movie This Is the Army, eased military protocol to make possible a burial at Arlington National Cemetery.

In his heyday Joe Louis enjoyed fame and assumed a symbolic significance greater than any other African American. His reign as world champion marked the end of African Americans’ exclusion from professional sports and also convinced whites that black achievements need not come at their expense. Most important, his victories in the ring served to inspire even the most powerless Americans, as the Swedish sociologist Gunnar Myrdal discovered when he visited a remote Georgia school in the 1930s. Myrdal interviewed the children and found that none of them had heard of President Franklin Roosevelt, W. E. B. DU BOIS, or WALTER WHITE. They had all heard of Joe Louis.

Louis, Joe, with Edna and Art Rust. My Life (1978).

ASHE, ARTHUR. A Hard Road to Glory: A History of the African American Athlete, 1919–1945 (1988).

Mead, Chris. Champion Joe Louis: Black Hero in White America (1985).

Sammons, Jeffrey T. Beyond the Ring: The Role of Boxing in American Society (1988).

Obituary: New York Times, 13 Apr. 1981.

—STEVEN J. NIVEN

LOVE, NAT

LOVE, NAT(June 1854–1921), cowboy and author, was born in Davidson County, Tennessee, the son of Sampson Love and a mother whose name is unknown. Both were slaves owned by Robert Love, whom Nat described as a “kind and indulgent Master.” Nat Love’s father was a foreman over other slaves; his mother, a cook. The family remained with Robert Love after the end of the Civil War.

Nat Love, the cowboy who claimed to be the original “Deadwood Dick” of dime novel fame. Library of Congress

In February 1869 Nat struck out on his own. He left because Robert Love’s plantation was in desperate economic straits after the war, and he sensed that there were few opportunities other than agricultural work for young former slaves in the defeated South. Although his father had died the year before, leaving him the head of the family, Nat nevertheless left because, as he admitted, “I wanted to see more of the world.”

After a short stay in Kansas, Love worked for three years on the ranch of Sam Duval in the Texas panhandle. For the next eighteen years (1872–1890) Love was a cowboy on the giant Gallinger Ranch in southern Arizona. He traveled all the western trails between south Texas and Montana herding cattle to market and, as his autobiography reveals, engaged in the drinking, gambling, and violence typical of western cow towns. He became an expert in identifying cattle brands and learned to speak fluent Spanish on trips to Mexico. In 1889 he married a woman named Alice (maiden name unknown), with whom he had one child.

The cowboy business was doomed by the westward movement of the railroads. Love recognized this situation and in 1890 secured employment with the Denver and Rio Grande Railroad as a Pullman car porter, one of the few occupations open to black men in the West. For fifteen years Love held this position on various western railroads. His last job, beginning in 1907, was as a bank guard with the General Securities Company in Los Angeles, where he died.

Most of what is known of Love’s life is from his 1907 autobiography, The Life and Adventures of Nat Love, Better Known in the Cattle Country as “Deadwood Dick,” by Himself. The one-hundred-page work seems to have been inspired by the popular and melodramatic dime novels of the day and likely contains more than a bit of fiction itself. Love certainly portrayed himself as a larger-than-life figure. He claimed he could outdrink any man in the West without it affecting him in any way. He depicted himself as one of the most expert cowboys, who could outrope, outshoot, and outride the best of them. He reported that he single-handedly broke up a robbery at an isolated Union Pacific railroad station. “I carry the marks of fourteen bullet wounds on different part [sic] of my body, most any one of which would be sufficient to kill an ordinary man,” he boasted,” “but I am not even crippled. . . . I have had five horses shot from under me. . . . Yet I have always managed to escape with only the mark of a bullet or knife as a reminder.” Shot and captured by Indians in 1876, he said he was nursed back to health by them and adopted into the tribe; he was offered the chiefs daughter in marriage. But Love had other plans and made his escape one night. He claimed as close acquaintances many western notables such as William F. “Buffalo Bill” Cody, Frank and Jesse James, Kit Carson, and “Billy the Kid” (William H. Bonney). Even as a railroad porter Love made himself out to be one of the best.

The legendary “Deadwood Dick” was created by the western dime novelist Edward L. Wheeler in the 1870s. Several men claimed to be the prototype for the character, including Love, whose autobiography places him in Deadwood in the Dakota Territory on the Fourth of July 1876. In a roping contest, he “roped, threw, tied, bridled, saddled and mounted my mustang in exactly nine minutes,” a championship record he said he held until his retirement as a cowboy fourteen years later and a feat, so he claimed, that instantly won him the title of “Deadwood Dick.”

The autobiography is consistently upbeat, with the author invariably winning out over those skeptical of his abilities. He mentions no incidents of racial discrimination, although they are known to have occurred in the West. While his accounts of heroic achievements and derring-do are certainly possible, he seems to have stretched the truth, not unlike other western reminiscences. And some of his claims are not verified in other sources. As one student of the West, William Loren Katz, commented, Love’s autobiography is “easy to read but hard to believe” (Katz, 323). Yet his life and work do illustrate how a black man of the late nineteenth century could rise from slavery to a satisfying life in the cowboy world, where ability and fortitude did serve to mitigate race prejudice.

Love, Nat. The Life and Adventures of Nat Love, Better Known in the Cattle Country as “Deadwood Dick,” by Himself (1907; repr. 1968).

Durham, Philip, and Everett L. Jones. The Negro Cowboys (1965).

Felton, Harold W. Nat Love: Negro Cowboy (1969).

Katz, William Loren. The Black West (1971).

—WILLIAM F. MUGLESTON

LYNCH, JOHN ROY

LYNCH, JOHN ROY(10 Sept. 1847–2 Nov. 1939), U.S. congressman, historian, and attorney, was born on “Tacony” plantation near Vidalia, Louisiana, the son of Patrick Lynch, the manager of the plantation, and Catherine White, a slave. Patrick Lynch, an Irish immigrant, purchased his wife and two children, but in order to free them, existing state law required they leave Louisiana. Before Patrick Lynch died, he transferred the titles to his wife and children to a friend, William Deal, who promised to treat them as free persons. However, when Patrick Lynch died, Deal sold the family to a planter, Alfred W. Davis, in Natchez, Mississippi. When Davis learned of the conditions of the transfer to Deal, he agreed to allow Catherine Lynch to hire her own time while he honeymooned with his new wife in Europe. Under this arrangement, Catherine Lynch lived in Natchez, worked for various employers, and paid $3.50 a week to an agent of Davis, keeping whatever else she earned.

On Davis’s return, he and Catherine Lynch reached an agreement that her elder son would work as a dining-room servant and the younger, John Roy, would be Davis’s valet. Catherine accepted these conditions, recognizing that she had no alternative. Under this arrangement, John Roy Lynch studied for confirmation and baptism in the Episcopal Church, but the Civil War intervened. Lynch attended black Baptist and Methodist churches during and after the war. Because of a falling out with Davis’s wife, Lynch briefly worked on a plantation until he became ill.

When Union forces reached Natchez in 1863, they freed Lynch, who was sixteen years old. He was visiting relatives at Tacony when Confederate troops overran the plantation and began seizing the ex-slaves as captives. Lynch convinced the troops that the workers had smallpox, which was a ruse, and the military released them.

Lynch worked at several jobs from 1865 to 1866, including dining-room waiter at a boardinghouse, cook with the Forty-ninth Illinois Volunteers Regiment, and pantryman aboard a troop transport ship moored at Natchez. Eventually he became a messenger in a photography shop, where he learned the photographic developing process as a “printer.” He continued that line of work with another shop, and in 1866 he took over the full management of a photography shop in Natchez. Briefly attending a grammar school operated by northern teachers, he learned to read by studying newspapers, reading books, and listening to classes given in a white school near his shop. One of the books he studied was on parliamentary law, which fascinated him.

In 1868 Lynch gave a number of speeches in Natchez before the local Republican club in support of the new Mississippi state constitution. The constitution legitimized all slave marriages, including that of his mother and father. In his autobiography Lynch noted that the later constitution, passed by Democrats in 1890, did away with the feature that had legitimized marriages between whites and African Americans but not retroactively.

In 1869 the Natchez Republican club sent Lynch to discuss local political appointments with the state’s military governor, Adelbert Ames. Impressed with Lynch’s presentation, Ames appointed him justice of the peace, a position Lynch had not sought. Later that year Lynch was elected to the Mississippi House of Representatives, where he served through 1873. In his first term he sat on the Judiciary Committee and the Committee on Elections and Education. In his last term he served as Speaker of the house and earned recognition and praise from Republican and Democratic legislators and the local press. During this period he formed an alliance with Governor James L. Alcorn, a white Republican who urged his party to make common cause with black voters. Lynch worked closely with other African Americans in the Mississippi Republican Party, especially BLANCHE K. BRUCE and James Hill. Later he fell into disagreement with Hill, who opposed Lynch’s influence in the party.

Lynch was elected to Congress in 1872 and was reelected in 1874. In Congress, he impressed his colleagues with his knowledge of parliamentary procedure, unusual among the small contingent of southern African American Republican members of Congress. Arguing forcefully for the Civil Rights Act of 1875, he called it “an act of simple justice” that “will be instrumental in placing the colored people in a more independent position.” He anticipated that, given more civil rights, blacks would vote in both parties and not depend entirely on the Republican Party.

Defeated in the 1876 congressional election, Lynch charged his opponent with fraud. In the election in 1880, through a series of dishonest practices, including lost ballot boxes, miscounts, and stuffed boxes, at least five thousand votes for Lynch were wrongfully thrown out. General James R. Chalmers, a Democrat, claimed victory, but Lynch contested the election. Finally seated late in the term, Lynch served in 1882–1883. Although he was defeated for reelection in 1882 by Henry S. Van Eaton, Lynch was regarded as a political hero by the Republican Party. He was the keynote speaker and temporary chairman of the 1884 national convention. Lynch was the last black keynote speaker at a national political convention until 1968.

In 1884 Lynch married Ella W. Somerville. They had one child before divorcing in 1900. From 1869 through 1905 he was successful in buying and selling real estate, including plantations, in the Natchez region. In 1889 President Benjamin Harrison appointed Lynch fourth auditor of the Treasury for the Navy Department, and he served to 1893.

In 1890 Lynch protested strongly against the “George” scheme, which, under the new Mississippi state constitution, required a literacy test for voting. An “understanding” clause also allowed registrars to pass whites and deny registration to African Americans who could not satisfactorily demonstrate an understanding of the state constitution.

In 1896 Lynch and Hill led competing delegations to the Republican National Convention. Both factions were committed to William McKinley, and through a compromise, delegates from both groups were seated at the convention. One of Hill’s delegates bolted the McKinley slate, reducing the influence of the Hill “machine.” After the election, McKinley gave Lynch partial control over the distribution of political patronage in the state.

Lynch began to study law in the 1890s and was admitted to the Mississippi bar in 1896. He subsequently obtained a license to practice law in Washington, D.C., where he opened an office with Robert H. Terrell, who had worked with him in the Treasury Department. He continued with this practice into 1898.

With the outbreak of the Spanish-American War, McKinley selected Lynch as an additional paymaster of volunteers with the rank of major in the army. In 1900 Lynch was again a delegate to the Republican National Convention, serving on the Committee on Platform and Resolutions and as chair of the subcommittee that drafted the national platform.

After the war Lynch remained with the army and received a regular commission in 1901. For three years he was assigned to Cuba, where he learned Spanish, then he was stationed for three and a half years in Omaha, Nebraska, and for sixteen months in San Francisco. In 1907 he sailed for Hawaii and the Philippines. In the Philippines a medical examiner claimed that Lynch had a serious heart condition and was therefore unfit for service with only a few months to live. Suspecting racial discrimination, Lynch protested directly to Washington and was reassigned to California.

Lynch retired from the army in 1911 and moved to Chicago. In 1912 he married Cora Williamson, who was twenty-seven years younger than he. They had no children. Admitted to the Chicago bar by reciprocity in 1915, he practiced law for over twenty-five years. During these years he began writing about the Reconstruction period. An early revisionist, he anticipated the later writings of W. E. B. DU BOIS and the post-World War II historians, who looked at the achievements of African American politicians in the 1860s and 1870s with more objectivity than prior historians. Lynch published several well-documented works, beginning with The Facts of Reconstruction (1914). Initially rejected by several presses, his critique of James Ford Rhodes’s history was published in 1917 and 1918 as two articles in the Journal of Negro History and was republished in 1922 entitled Some Historical Errors of James Ford Rhodes. He also criticized as full of errors Claude G. Bowers’s work The Tragic Era (1920). He later incorporated a large section of his 1913 history of Reconstruction in his autobiography, Reminiscences of an Active Life, completed shortly before his death in Chicago but not published until 1970, edited by JOHN HOPE FRANKLIN.

An accomplished African American author and politician, Lynch was representative of a small group who worked with some success within the existing political and patronage structure to create opportunities for themselves and to fight for civil rights. Considering his childhood as a slave and his lack of formal education, his achievements as a politician, statesman, and historian are notable.

Some Lynch correspondence is in the papers of CARTER G. WOODSON in the Manuscripts Division of the Library of Congress.

Bell, Frank C. “The Life and Times of James R. Lynch: A Case Study 1847–1939,” Journal of Mississippi History 38 (Feb. 1976): 53–67.

Mann, Kenneth E. “John Roy Lynch, U.S. Congressman from Mississippi,” Negro History Bulletin 37 (Apr. 1974): 239–241.

Obituary: New York Times, 3 Nov. 1939.

—RODNEY P. CARLISLE

LYNK, MILES VANDAHURST

LYNK, MILES VANDAHURST(3 June 1871–29 Dec. 1956), physician, educator, and advocate for African American physicians, was born near Brownsville, Tennessee, the son of John Henry Lynk, a farmer, and Mary Louise Yancy, both former slaves. Miles’s parents, members of the Colored (now Christian) Methodist Episcopal (CME) church, founded in nearby Jackson, Tennessee, named their son after the CME’s first two bishops, William Henry Miles and Richard H. Vanderhorst. Miles received basic education from his mother, a country school near Brownsville, a tutor he hired with money he had earned, and a course of self-teaching, which he called attending “Pine Knot College.” At age seventeen Miles taught at a Negro summer school in a neighboring county and used the money to apprentice himself to Jacob C. Hairston, a local physician and graduate of Meharry Medical College in Nashville. Robert Fulton Boyd, a Meharry professor, was sufficiently impressed with Lynk’s entrance examination to admit him to Meharry Medical College in 1889. Lynk finished in two years while the normal course was three years, and, by his own account, graduated second in a class of thirteen.

His own man throughout his life, Lynk ignored the advice of friends, and opened a practice in Jackson, Tennessee, the site of recent racial unrest. In the racially tense and increasingly segregated late-nineteenth-century South, Lynk personally introduced himself to local white physicians and druggists as a way of defusing their concerns. To forestall adverse reaction to a black physician’s presence in Jackson’s previously all-white medical profession, Lynk used the tactic other African American physicians of the time employed and, according to his autobiography, “gave each [physician and druggist] my card with the statement that I shall endeavor to practice scientific and ethical medicine” (Lynk, 27–28).

Medicine was becoming a crowded profession, and black physicians were not always given a warm reception by white doctors worried about losing paying patients, black or white. Black physicians often charged lower fees because their predominantly African American clientele usually had low incomes. They thus attracted some white patients more interested in low cost than in their physician’s race. In addition to gaining fellow physicians’ acceptance, Lynk had to win over the African American population as well. Many African Americans—as a result of biases learned from whites since slavery times, bad experiences with African American healers, or superstitious belief—were reluctant to use black physicians. To overcome such prejudice, Lynk worked diligently in his practice, took the time to educate people about good hygiene and sanitation, gave lectures about health and disease to black teachers and church groups, and generally followed his motto “Do all the good you can to all the people you can in all the ways you can.” These approaches seemed to work and Lynk reported in the Jackson Daily Sun that he “soon overcame their [African Americans’] scruples and built up a large and lucrative practice” (12 Dec. 1900). A brief notice in the 26 September 1891 issue of the Christian Index, a CME newspaper published in Jackson, attests to his success:

Dr. M.V. Lynk, our Colored physician in this city, has built up such a large practice that it became very necessary that he have a horse and buggy to meet his calls. He now has a splendid outfit and is doing well. Our prediction last winter that a colored doctor would do well here has proven to be true. We are quite glad to see our people giving him their patronage. This is nothing more than right.

From the start of his career Lynk worked not only for his own success but also for the betterment of African Americans, both locally and nationally. At age twenty-one, he established a monthly medical journal for African American physicians, which one black physician from Texas proudly called “a journal of our own” (Lynk, 38). Medical journals of the time ignored the publications and activities of black physicians, medical schools, medical societies, and hospitals. To give African American physicians a voice, Lynk began publishing the Medical and Surgical Observer (MSO) in December 1892. In addition to publishing medical articles and reports on black physicians’ experiences, it provided Lynk the opportunity to promote his own ideas while bringing a sense of community to often isolated African American physicians around the country. The MSO survived for only fourteen issues, until January 1894. Lynk gave no official reason for ceasing publication, though he hinted in editorials at low subscription numbers, lack of article submissions by black physicians, and decreased advertising.

One idea Lynk promoted in the MSO that came to fruition was the formation of a national association of black medical professionals. Such an association was needed, Lynk had explained in an editorial in the first issue of the MSO, because black physicians were excluded from the national American Medical Association as well as from southern (and many northern) local and regional medical societies. Black health professionals in Texas and North Carolina, he reported, had established their own societies and were trying to link up with other physicians elsewhere. On 18 November 1895 at the Cotton States and International Exposition in Atlanta where BOOKER T. WASHINGTON delivered his famous Atlanta Compromise speech, Lynk, along with a few other black physicians, and his Meharry professor Robert F. Boyd, held an organizational meeting of what became the National Medical Association.

In 1900, unable to obtain law training in Jackson, Lynk arranged with Lane College, a local CME-sponsored school, for H. R. Sadler, an African American lawyer in Memphis, to offer a law course. Lynk recruited the students, purchased a law library, and allowed his medical office to be used as a classroom. In February 1901, after earning his law degree and passing the Tennessee bar, Lynk founded the University of West Tennessee (UWT), a “college for the professional training of ambitious Negroes.” One of the last of fourteen predominantly black medical schools established between Reconstruction and the start of the twentieth century (only Howard and Meharry medical schools survive today), UWT opened in a newly renovated and appropriately equipped house, with newly hired teachers, and offered its African American students medical, dental, pharmaceutical, nursing, and law training. Lynk established his school despite the rising cost of medical education due to the rapid growth of scientific medicine, and found UWT’s facilities and faculty quickly outdated. The school eventually lost its accreditation—despite a move to Memphis in 1907—and was forced to close in 1923, having graduated one hundred and fifty-five physicians and a number of lawyers, nurses, dentists, and pharmacists.

During the 1890s Lynk wrote books and edited a magazine for African Americans. Lynk Publishing House, which he established to print and sell his work, provided employment to about a dozen African American workers. By 1900 he had published The Afro-American School Speaker and Gems of Literature, for School Commencements, Literary Circles, Debating Clubs, and Rhetoricals Generally (1896), a collection of black literature, and The Black Troopers; or, The Daring Heroism of the Negro Soldiers in the Spanish-American War (1899), which sold more than fifteen thousand copies. He also edited and published several issues of an illustrated monthly literary magazine Lynk’s Magazine (1898–1899), which was followed some twenty years later by another magazine The Negro Outlook (1919).

Lynk, who was married twice, in 1893 to chemist Beebe Steven, and in 1949 to Ola Herin Moore, remained active in medicine throughout his life. He combated racism and segregation by his own medical, law, and publishing work and by helping establish black institutions parallel to those in the white medical world (a journal, medical school, and medical society). The National Medical Association, which he helped found in 1895, awarded him its Distinguished Service Medal in 1952. Lynk died in Memphis.

Lynk, Miles V. Sixty Years of Mediane; or, The Life and Times of Dr. Miles V. Lynk: An Autobiography (1951).

Savitt, Todd L. “‘A Journal of Our Own’: The Medical and Surgical Observer at the Beginnings of an African American Medical Profession in Late Nineteenth-Century America,” Journal of the National Medical Association (88, 1996).

_______. Savitt, Todd L. “Four African-American Proprietary Medical Colleges: 1888–1923,” Journal of the History of Mediane & Allied Sciences (55, 2000).

—TODD L. SAVITT