MABLEY, MOMS

MABLEY, MOMS MABLEY, MOMS

MABLEY, MOMS(19 Mar. 1894?–23 May 1975), comedian, was born Loretta Mary Aiken in Brevard, North Carolina, the daughter of Jim Aiken, a businessman and grocer. Her mother’s name is not known. Details of her early life are sketchy at best, but she maintained in interviews she had black, Irish, and Cherokee ancestry. Her birth date is often given as sometime in 1897. Her grandmother, a former slave, advised her at age thirteen “to leave home if I wanted to make something of myself.” However, she may have been unhappy over an arranged marriage with an older man. Mabley stated in a 4 October 1974 Washington Post interview, “I did get engaged two or three times, but they always wanted a free sample.” Her formative years were spent in the Anacostia section of Washington, D.C., and in Cleveland, Ohio, where she later maintained a home. She had a child out of wedlock when she was sixteen. In an interview she explained she came from a religious family and had the baby because “I didn’t believe in destroying children.” Mabley recalled that the idea to go on the stage came to her when she prayed and had a vision. But in a 1974 interview she said she went into show business “because I was very pretty and didn’t want to become a prostitute.” Another time she explained, “I didn’t know I was a comic till I got on the stage.”

In 1908 she joined a Pittsburgh-based minstrel show by claiming to be sixteen; she earned $12.50 a week and sometimes performed in blackface. By 1910 she was working in black theatrical revues, such as Look Who’s Here (1920), which briefly played on Broadway. She became engaged to a Canadian named Jack Mabley. Though they never married, she explained she took his name because “he took a lot off me and that was the least I could do.”

Moms Mabley, “The Funniest Woman in the World,” shown here in character on a television appearance. © Bettmann/CORBIS

In 1921 Mabley was working the “chitlin circuit,” as black entertainers referred to black-owned and -managed clubs and theaters in the segregated South. There, she recalled, she introduced a version of the persona that made her famous, the weary older woman on the make for a younger man. The dance duo Butterbeans and Suzie (Jody and Susan Edwards) caught her act and hired her, polishing her routines and introducing her to the Theater Owners Booking Association, or TOBA—black artists said the initials stood for Tough on Blacks. She shared bills with Pigmeat Markham, Tim “Kingfish” Moore, and BILL “BOJAN-GLES” ROBINSON.

In the late 1920s when Mabley struggled to find work in New York, black comedian Bonnie Bell Drew (Mabley named her daughter in her honor) became mentor to Mabley, teaching her comedy monologues. Soon Mabley was working Harlem clubs such as the Savoy Ballroom and the Cotton Club and Atlantic City’s Club Harlem. She appeared on shows with BESSIE SMITH and CAB CALLOWAY (with whom she had an affair), LOUIS ARMSTRONG, and the COUNT BASIE, DUKE ELLINGTON, and Benny Goodman orchestras. During the Depression, when many clubs closed, she worked church socials and urban movie houses, such as Washington’s Howard and Chicago’s Monogram and Regal Theatres, where she later returned as a headliner.

Mabley had bit parts in early talkies made in the late 1920s in New York. She played a madam in The Emperor Jones (1931), based on the Eugene O’Neill play and starring PAUL ROBESON. In 1931 Mabley collaborated on and appeared in the short-lived Broadway production Fast and Furious: A Colored Revue in 37 Scenes with flamboyant Harlem Renaissance writer ZORA NEALE HURSTON. In the late 1920s she appeared in a featured role on Broadway in Blackbirds. She played Quince in Swinging the Dream (also featuring Butterfly McQueen) in 1939, a jazz adaptation of A Midsummer Night’s Dream. Other films include Killer Diller (1947), opposite NAT KING COLE and Butterfly McQueen; Boardinghouse Blues (1948), in which she played a role much like her stage character; and Amazing Grace (1974), in which McQueen and STEPIN FETCHIT had cameos. It was drubbed by critics but did well at the box office.

The most popular Mabley character was the cantankerous but lovable toothless woman with bulging eyes and raspy voice who wore a garish smock or rumpled clothes, argyle socks, and slippers. Though she maintained, “I do the double entendre . . . and never did anything you haven’t heard on the streets,” the nature of her material, more often than not off-color, was such that, in spite of the brilliance of her comic timing and gift of ad-libbing, she was denied the route comics such as Flip Wilson, DICK GREGORY, and BILL COSBY took into fine supper clubs and Las Vegas. A younger brother, Eddie Parton, wrote comedy situations for her, but most of her material was absorbed from listening to her world. Offstage Mabley was an avid reader and an attractive woman who wore furs, chic clothes, and owned a Rolls-Royce, albeit an inveterate smoker, a card shark, and a whiz at checkers.

In 1940 she broke the gender barrier and became the first female comic to appear at Harlem’s Apollo Theatre, where her act, which included song and dance, played fifteen sold-out weeks. Mabley was mentor to young PEARL BAILEY and befriended by LANGSTON HUGHES, who wrote a friend that he occasionally helped Mabley financially. Legend has her acquiring the nickname “Moms” because of her mothering instincts toward performers.

Her first album, Moms Mabley, the Funniest Woman in the World (1960), sold in excess of a million copies. In 1966 she was signed by Mercury Records. She made over twenty-five comedy records, many capturing her live performances; others, called “party records,” had laugh tracks. She said black and white comics stole her material, then forgot her when they became famous.

Television was late to discover Mabley. Thanks to fan HARRY BELAFONTE, she made her TV debut in a breakthrough comedy he produced with an integrated cast, A Time for Laughter (1967), as the maid to a pretentious black suburban couple. Merv Griffin invited her on his show, and appearances followed with Mike Douglas and variety programs starring Flip Wilson, Bill Cosby, and the Smothers Brothers. Mabley had been known mainly to black audiences. Of this late acceptance, she mused, “It’s too bad it took so long. Now that I’ve got some money, I have to use it all for doctor bills.” Mabley was not always career savvy. She passed up an appearance on CBS’s top-rated Ed Sullivan Show, saying, “Mr. Sullivan didn’t want to give me but four minutes. Honey, it takes Moms four minutes just to get on the stage.”

Because of her influence with African Americans, Mabley was seriously courted by politicians such as ADAM CLAYTON POWELL JR., whom she called “my minister.” She did not aggressively support the 1960s civil rights movement, and she expressed outrage at the riots in Harlem. She was invited to the White House by Presidents John F. Kennedy and Lyndon Johnson. Of the latter event, she told a (fictional) joke about admonishing Johnson to “get something colored up in the air quick” (a black astronaut). She said, “I happen to spy him [and] said, ‘Hey, Lyndon! Lyndon, son! Lyndon. Come here, boy!’” She brought the house down merely by the gall in her delivery. Mabley maintained she corresponded with and met Eleanor Roosevelt to “talk about young men.”

Various articles, which say nothing of a first husband—if there was one—note that Mabley had been separated from her second husband, Ernest Scherer, for twenty years when he died in 1974. The comedian had three daughters and adopted a son, who became a psychiatrist.

Late in her career, Mabley played Carnegie Hall on a bill with singer Nancy Wilson and jazz great Cannonball Adderley, the famed Copacabana, and even Washington’s Kennedy Center (Aug. 1972).

During the filming of her last movie, Mabley suffered a heart attack, and production was delayed for her to undergo surgery for a pacemaker. Her condition weakened on tours to publicize the film, and for six months she was confined to her home in Hartsdale, in New York’s Westchester County. She died at White Plains Hospital. Her funeral at Harlem’s Abyssinian Baptist Church drew thousands of fans.

The Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture of the New York Public Library and the New York Public Library for the Performing Arts maintain research files.

Bogle, Donald. Brown Sugar: Eighty Years of America’s Black Female Superstars (1980).

Sochen, June. Women’s Comic Visions (1991).

Watkins, Mel. On the Real Side, Laughing, Lying, and Signifying: The Underground Tradition of African American Humor That Transformed American Culture, from Slavery to Richard Pryor (1994).

Williams, Elsie A. The Humor of Jackie “Moms” Mabley: An African American Comedie Tradition (1995).

Obituary: New York Times, 25 May 1975.

—ELLIS NASSOUR

MALCOLM X

MALCOLM X(19 May 1925–21 Feb. 1965), Islamic minister and political leader, also known as el-Hajj Malik el-Shabazz, was born Malcolm Little in Omaha, Nebraska, the fourth of five children of Earl Little and Louise (also Louisa) Norton, both activists in the Universal Negro Improvement Association established by MARCUS GARVEY. Earl Little, a Georgia-born itinerant Baptist preacher, encountered considerable racial harassment because of his black nationalist views. He moved his family several times before settling in Michigan, purchasing a home in 1929 on the outskirts of East Lansing, where Malcolm spent his childhood. Their previous home had been destroyed in a mysterious fire. In 1931 Earl Little’s body was discovered on a train track. Although police concluded that the death was accidental, the victim’s friends and relatives suspected that he had been murdered by a local white supremacist group. Earl’s death left the family in poverty and undoubtedly contributed to Louise Little’s mental deterioration. In January 1939 she was declared legally insane and committed to a Michigan mental asylum, where she remained until 1963.

Malcolm X, national spokesman for the Nation of Islam, delivers a fiery address in Harlem, 1963. Corbis

Although Malcolm Little excelled academically in grammar school and was popular among classmates at these predominantly white schools, he also became embittered toward white authority figures. In his autobiography he recalls quitting school in the eighth grade after a teacher warned that his desire to become a lawyer was not a “realistic goal for a nigger.” As his mother’s mental health deteriorated and he became increasingly incorrigible, welfare officials intervened, placing him in several reform schools and foster homes. In 1941 he left Michigan to live in Boston with his half sister, Ella Collins.

In Boston and New York during the early 1940s, Malcolm held a variety of railroad jobs while also becoming increasingly involved in criminal activities, such as peddling illegal drugs and numbers running. At this time he was often called Detroit Red because of his reddish hair. First arrested in 1944 for larceny and given a three-month suspended sentence and a year’s probation, Malcolm was arrested again in 1946 for larceny as well as breaking and entering. When the judge learned that Malcolm was involved in a romantic relationship with a white woman, he imposed a particularly severe sentence of from eight to ten years in prison. While in Concord Reformatory in Massachusetts, Malcolm responded to the urgings of his brother Reginald and became a follower of ELIJAH MUHAMMAD (formerly Robert Poole), leader of the Temple of Islam (later Nation of Islam—often called the Black Muslims), a small black nationalist Islamic sect. Attracted to the religious group’s racial doctrines, which categorized whites as “devils,” he began reading extensively about world history and politics, particularly concerning African slavery and the oppression of black people in America. After he was paroled from prison in August 1952, he became Malcolm X, using the surname assigned to him in place of the African name that had been taken from his slave ancestors.

By 1953 Malcolm X had become Elijah Muhammad’s most effective minister, bringing large numbers of new recruits into the group during the 1950s and early 1960s. By 1954 he had become minister of New York Temple No. 7, and he later helped establish Islamic temples in other cities. In 1957 he became the Nation of Islam’s national representative, a position of influence second only to that of Elijah Muhammad. In January 1958 he married Betty X (Sanders), who later became known as Betty Shabazz; together they had six daughters.

Malcolm’s cogent and electrifying oratory attracted considerable publicity and a large personal following among discontented African Americans. In his speeches he urged black people to separate from whites and win their freedom “by any means necessary.” In 1957, after New York police beat and jailed Nation of Islam member Hinton Johnson, Malcolm X mobilized supporters to confront police officials and secure medical treatment. A 1959 television documentary on the Nation of Islam, called The Hate That Hate Produced, further increased Malcolm’s notoriety among whites. In 1959 he traveled to Europe and the Middle East on behalf of Elijah Muhammad, and in 1961 he served as Muhammad’s emissary at a secret Atlanta meeting seeking an accommodation with the Ku Klux Klan. The following year he participated in protest meetings prompted by the killing of a Black Muslim during a police raid on a Los Angeles mosque. By 1963 he had become a frequent guest on radio and television programs and was the most well known figure in the Nation of Islam.

Malcolm X was particularly harsh in his criticisms of the nonviolent strategy to achieve civil rights reforms advocated by MARTIN LUTHER KING JR. His letters seeking King’s participation in public forums were generally ignored by King. During a November 1963 address at the Northern Negro Grass Roots Leadership Conference in Detroit, Michigan, Malcolm derided the notion that African Americans could achieve freedom non-violently. “The only revolution in which the goal is loving your enemy is the Negro revolution,” he announced. “Revolution is bloody, revolution is hostile, revolution knows no compromise, revolution overturns and destroys everything that gets in its way.” Malcolm also charged that King and other leaders of the recently held March on Washington had taken over the event, with the help of white liberals, in order to subvert its militancy. “And as they took it over, it lost its militancy. It ceased to be angry, it ceased to be hot, it ceased to be uncompromising,” he insisted. Despite his caustic criticisms of King, Malcolm nevertheless identified himself with the grass-roots leaders of the southern civil rights protest movement. His desire to move from rhetorical to political militancy led him to become increasingly dissatisfied with Elijah Muhammad’s apolitical stance. As he later explained in his autobiography, “It could be heard increasingly in the Negro communities: ‘Those Muslims talk tough, but they never do anything, unless somebody bothers Muslims.’”

Malcolm’s disillusionment with Elijah Muhammad resulted not only from political differences but also from his personal dismay when he discovered that the religious leader had fathered illegitimate children. Other members of the Nation of Islam began to resent Malcolm’s growing prominence and to suspect that he intended to lay claim to leadership of the group. When Malcolm X remarked that President John Kennedy’s assassination in November 1963 was a case of the “chickens coming home to roost,” Elijah Muhammad used the opportunity to ban his increasingly popular minister from speaking in public.

Despite this effort to silence him, Malcolm X continued to attract public attention during 1964. He counseled the boxer Cassius Clay, who publicly announced, shortly after winning the heavyweight boxing title, that he had become a member of the Nation of Islam and adopted the name MUHAMMAD ALI. In March 1964 Malcolm announced that he was breaking with the Nation of Islam to form his own group, Muslim Mosque, Inc. The theological and ideological gulf between Malcolm and Elijah Muhammad widened during a month-long trip to Africa and the Middle East. During a pilgrimage to Mecca on 20 April 1964 Malcolm reported that seeing Muslims of all colors worshiping together caused him to reject the view that all whites were devils. Repudiating the racial theology of the Nation of Islam, he moved toward orthodox Islam as practiced outside the group. He also traveled to Egypt, Lebanon, Nigeria, Ghana, Senegal, and Morocco, meeting with political activists and national leaders, including the Ghanaian president Kwame Nkrumah. After returning to the United States on 21 May, Malcolm announced that he had adopted a Muslim name, el-Hajj Malik el-Shabazz, and that he was forming a new political group, the Organization of Afro-American Unity (OAAU), to bring together all elements of the African American freedom struggle.

Determined to unify African Americans, Malcolm sought to strengthen his ties with the more militant factions of the civil rights movement. Although he continued to reject King’s nonviolent, integrationist approach, he had a brief, cordial encounter with King on 26 March 1964 as the latter left a press conference at the U.S. Capitol. The following month, at a symposium in Cleveland, Ohio, sponsored by the Congress of Racial Equality, Malcolm X delivered one of his most notable speeches, “The Ballot or the Bullet,” in which he urged black people to submerge their differences “and realize that it is best for us to first see that we have the same problem, a common problem—a problem that will make you catch hell whether you’re a Baptist, or a Methodist, or a Muslim, or a nationalist.”

When he traveled again to Africa during the summer of 1964 to attend the Organization of African Unity Summit Conference, he was able to discuss his unity plans at an impromptu meeting in Nairobi with leaders of the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee. After returning to the United States in November, he invited FANNIE LOU HAMER and other members of the Mississippi Freedom Democratic Party to be guests of honor at an OAAU meeting held the following month in Harlem, New York. Early in February 1965 he traveled to Alabama to address gatherings of young activists involved in a voting rights campaign. He tried to meet with King during this trip, but the civil rights leader was in jail; instead, Malcolm met with CORETTA SCOTT KING, telling her that he did not intend to make life more difficult for her husband. “If white people realize what the alternative is, perhaps they will be more willing to hear Dr. King,” he explained.

Malcolm’s political enemies multiplied within the U.S. government as he attempted to strengthen his ties with civil rights activists and deepen his relationship with ADAM CLAYTON POWELL JR., JAMES BALDWIN, Dick Gregory, and black leaders around the world. The Federal Bureau of Investigation saw Malcolm as a subversive and initiated efforts to undermine his influence. In addition, some of his former Nation of Islam colleagues, including Louis X (later LOUIS FARRAKHAN), condemned him as a traitor for publicly criticizing Elijah Muhammad. The Nation of Islam attempted to evict Malcolm from the home he occupied in Queens, New York. On 14 February 1965 Malcolm’s home was firebombed; although he and his family escaped unharmed, the perpetrators were never apprehended.

On 21 February 1965 members of the Nation of Islam shot and killed Malcolm as he was beginning a speech at the Audubon Ballroom in New York City. On 27 February more than fifteen hundred people attended his funeral service held in Harlem and OSSIE DAVIS gave a moving eulogy that contrasted the public’s perception of an angry Malcolm with the loving and gentle man he knew, a person who gave voice to the pain of his people and gave courage to those who were afraid to speak the truth. Although three men were convicted in 1966 and sentenced to life terms, one of those involved, Thomas Hagan, filed an affidavit in 1977 insisting that his actual accomplices were never apprehended.

After his death, Malcolm’s views reached an even larger audience than during his life. The Autobiography of Malcolm X, written with the assistance of ALEX HALEY, became a best-selling book following its publication in 1965. During subsequent years other books appeared, containing texts of many of his speeches, including Malcolm X Speaks (1965), The End of White World Supremacy: Four Speeches (1971), and February 1965: The Final Speeches (1992). In 1994 Orlando Bagwell and Judy Richardson produced a major documentary, Malcolm X: Make It Plain. His words and image also exerted a lasting influence on African American popular culture, as evidenced in the hip-hop or rap music of the late twentieth century and in the director SPIKE LEE’s film biography, Malcolm X (1992).

Malcolm X and Alex Haley. The Autobiography of Malcolm X (1999).

_______. Malcolm Speaks (1989).

Carson, Clayborne. Malcolm X: The FBI File (1991).

Dyson, Michael Eric. Making Malcolm (1996).

Myers, Walter Dean. Malcolm X: By Any Means Necessary (1994).

Perry, Bruce. Malcolm: The Life of a Man Who Changed Black America (1991).

Strickland, William. Malcolm X: Make It Plain (1995).

Obituary: New York Times, 22 Feb. 1965.

—CLAYBORNE CARSON

MALONE, ANNIE TURNBO

MALONE, ANNIE TURNBO(9 Aug. 1869–10 May 1957), entrepreneur and philanthropist, was born Annie Minerva Turnbo on a farm in Metropolis, Illinois, the tenth of eleven children of Robert Turnbo and Isabella Cook, both farmers. Robert and Isabella owned the land they farmed and were able to provide comfortably for themselves and their children. After her parents died of yellow fever in 1877, Annie went to live with an older sister in Peoria, Illinois. As a young woman, Annie grew dissatisfied with the hair-grooming methods then in use by African American women which often involved the use of goose fat, soap, and harsh chemicals for straightening purposes. Stronger products to straighten naturally curly hair generally damaged the hair follicles or scalp. One of the methods recommended by such products advised users to wash their hair and lay it out flat while using a hot flatiron to apply the solutions. Even washed and laid out, the hair of many women was not long enough to iron, and one of the most common beauty complaints among African American women was burned scalps; indeed, many black women suffered from baldness at an early age. In response, by 1900 Turnbo formulated and perfected a product line she named “Wonderful Hair Grower” which she sold through local stores near her home in Lovejoy, Illinois. Turbo also invented and patented both a pressing iron and a pressing comb, devices that, when used in conjunction with her products, aided in straightening African American hair.

In 1902, in an effort to expand her business opportunities, Turnbo relocated from Lovejoy to St. Louis, Missouri, where she and three assistants began selling her products door-to-door, offering women free, on-the-spot hair treatments. The approach was successful, and Turnbo undertook a highly profitable sales tour of the South in 1903. That same year she married a Mr. Pope but soon divorced him after her new husband attempted to exert control over her thriving door-to-door business. After the divorce, Turnbo opened her own salon, and a year later her products, which she called “Poro,” were being sold throughout the Midwest.

In 1906 Malone copyrighted the name “Poro,” a West African term that denotes an organization whose aim is to discipline and enhance the body both physically and spiritually. The company name might have another source, however: in advertisements for the company in 1908 and 1909, Annie Turnbo Pope is pictured with a woman named L. L. Roberts. Though there are no records indicating Roberts’s relationship to the company, it is possible that “Poro” is a contraction composed of Pope and Roberts.

The company’s sales growth was spurred by Malone’s understanding and use of modern business practices, including holding press conferences, advertising in African American newspapers, and using female salespeople. By the first decades of the twentieth century, Malone’s business was thriving, and by 1910 she had opened larger offices in St. Louis. In 1917 she opened Poro College, the first cosmetology school founded to train hairdressers to care for African American hair. The large, lavish facility included well-equipped classrooms, an auditorium, ice cream parlor, bakery, and theater, as well as the manufacturing facilities for Poro products. The college was soon a center of activity and influence in St. Louis’s black community, with several prominent local and national African American organizations housed on site. The college offered training courses that included etiquette classes for women interested in joining the Poro System’s agent-operator network. By the 1920s the Poro business employed 175 people in St. Louis and boasted of seventy-five thousand agents working throughout the United States and the Caribbean. In 1930 Turnbo opened new headquarters in Chicago that became known as the Poro Block. At the peak of her career, in the 1920s, Turnbo’s personal worth reached fourteen million dollars.

Turnbo’s business success has often been overshadowed by that of her contemporary, MADAME C. J. WALKER. In fact, Walker’s successful use of door-to-door sales agents was a business strategy she learned from Turnbo while employed as a Poro sales agent for several months in 1905. That same year, Walker informed friends that she had learned how to make a hair product that really worked. Perhaps in an effort to avoid direct competition with Turnbo, she moved to Denver early in 1906 to begin her own company.

In 1921 Turnbo married Aaron Malone, a decision that proved disastrous for the company. During much of the 1920s the Malones were engaged in a debilitating, behind-the-scenes power struggle that was kept hidden from all but a few Poro System executives. Before the couple’s divorce in 1927 and his subsequent termination from his position as chief manager and president, Aaron Malone sought support in a bid to take over the company. In asking the courts to award him half of the company, Malone claimed the success of his wife’s business was due to connections he had brought to the marriage. While Aaron managed to get support from key members of the black community, Annie Malone, with the help of influential black women leaders, including MARY MCLEOD BETHUNE, succeeded in keeping control of Poro after paying her ex-husband a settlement of around one hundred thousand dollars.

Malone’s largesse had certainly helped sway public opinion in her favor. She had become a generous contributor to African American organizations. She supported a pair of black students at every African American land-grant college in the country; orphanages for African American children regularly received donations of five thousand dollars; and during the 1920s alone, she gave sixty thousand dollars each to the St. Louis Colored Young Women’s Christian Association, the Tuskegee Institute, and the Howard University Medical School. Within her company Malone was equally magnanimous. Five-year employees received diamond rings, and punctuality and attendance were rewarded as well.

Soon after her divorce, Malone was back in court, when Edgar Brown filed suit against her for one hundred thousand dollars. The case was dismissed for lack of evidence. Ten years later, a former employee successfully brought suit against Malone. These legal and financial troubles exacerbated longstanding management problems at Poro. Poor oversight by Malone, bad hiring choices, rapid expansion, and the prolonged, behind the scenes power struggle with Aaron Malone had dire consequences for the company. These battles, both public and private, and her unmatched—and unchecked—generosity spelled the beginning of the end for Malone’s Poro empire. Malone was forced to sell her St. Louis property in order to pay for debts incurred, in part, by her divorce and court settlements. Due to her failure to pay excise and real estate taxes, the federal government seized control of the company in 1951. Malone died of a stroke in a Chicago hospital six years later, in 1957, at age eighty-seven. Upon her death, her estate was worth only one hundred thousand dollars.

Malone’s papers are available at the DuSable Museum of African American History in Chicago, Illinois.

Kathy Peiss, Hope in a Jar: The Making of America’s Beauty Culture (1998).

Obituary: The Chicago Defender, 10 May 1957.

—NOLIWE ROOKS

MARRANT, JOHN

MARRANT, JOHN(15 June 1755–Apr. 1791), minister and author, was born in the New York Colony to a family of free blacks. The names and occupations of his parents are not known. When he was four years old, his father died. Marrant and his mother moved to Florida and Georgia; subsequently Marrant moved to Charleston, South Carolina, to live with his sister and brother-in-law. He stayed in school until he was eleven years old, becoming an apprentice to a music master for two additional years. During this time he also learned carpentry. His careers in music and carpentry ended in late 1769 or early 1770, when he was converted to Christianity by the famous evangelical minister George Whitefield.

Over the next few years, Marrant converted many Native Americans, including members of the Cherokee, Creek, Choctaw, and Chickasaw nations. In 1772 he returned to his family for a short time. For the next three years Marrant worked as a minister in the Charleston area. There he saw a plantation owner and other white males whip thirty slaves for attending his church school.

With the onslaught of the revolutionary war, Marrant was impressed as a musician into the British navy in October or November of 1776. Not much is known of his exploits during this period besides the fact that he fought in the Dutch-Anglo War (1780–1784). As a result of his injuries, he was discharged in 1782.

Marrant eventually married. A listing in the New York City Inspection Roll of Negroes in 1783 cited a Mellia Marrant as “formerly the property of John Marrant near Santee Carolina”; this document also states that she “left him at the Siege of Georgetown.” Apparently, his wife had been a slave; he bought and freed her in order to marry her. The same listing claimed that Mellia was aboard the William and Mary with her children Amelia and Ben, heading for Annapolis Royal, Nova Scotia. There is no evidence to support or deny that they were Marrant’s children. The information in this record is all that is known of his marriage and offspring.

To further his opportunities, Marrant moved to London, England, living there between 1782 and 1785. In Bath on 15 May 1785, he was ordained a minister in the chapel of Selina Hastings, countess of Huntingdon and a supporter of the African American poet PHILLIS WHEATLEY. During this time, despite being literate, Marrant told his story to Methodist minister William Aldridge, who later published it as A Narrative of the Lord’s Wonderful Dealings with John Marrant, a Black (Now Going to Preach the Gospel in Nova-Scotia) Born in New-York, in North-America (1785). The narrative, in which Marrant describes his conversion and his life as a traveling minister, was so popular that it went through twenty editions by 1835. In 1785 S. Whitchurch and S. Hazard both published The Negro Convert: A Poem; Being the Substance of the Experience of Mr. John Marrant, a Negro.

In November 1785 Marrant moved to Birchtown, Nova Scotia, to minister to the black Loyalists who had immigrated there after the American Revolution. For the next two years he was persecuted and harassed by fellow ministers because he preached Calvinistic Methodism to whites, blacks, and Native Americans in Nova Scotia. Despite his persecution, he built a chapel in Birchtown, taught at the Birchtown school, preached to the congregation, and ministered in other towns. In late November 1786 Marrant gave up control of his school because of his exhaustion and decided to concentrate on being a traveling minister. He contracted smallpox in an epidemic in February 1787 and was ill for six months.

In Nova Scotia, Marrant lived a life of poverty and illness. In late January 1788 he moved to Boston, where he preached and apparently taught school. However, Marrant could not escape persecution. On 27 February 1789 he eluded a mob of forty armed men who were attempting to kill him because their girlfriends went to his Friday sermon. In March of that year he became a Freemason in the African Lodge. As a Freemason, Marrant gave a sermon at the Festival of John the Baptist; the sermon was published in 1789. On his way back to England, Marrant wrote his last journal entry on 7 March 1790. The journal was later published as A Journal of the Rev. John Marrant (1790), along with Marrant’s sermon of a funeral service in Nova Scotia. The preface of the journal gave the publication date of 29 June 1790. Marrant died somewhere in England and is buried at Islington.

In his sermons, Marrant tried to teach people to love God through a comparison of biblical allegories and everyday life. For example, in his Narrative, Marrant’s travels after his conversion are reminiscent of John the Baptist’s sojourn in the wilderness. His theme is clear: let Jesus and God be your guides. This message is stressed when faith saves him from being executed by a Native-American nation: “I fell down upon my knees, and mentioned to the Lord his delivering of the three children in the fiery furnace, and of Daniel in the Lion’s den, and had close communion with God. . . . And about the middle of my prayer, the Lord impressed a strong desire upon my mind to turn into their language, and pray in their tongue. . . which wonderfully affected the people” (Porter, 437).

In his short life, Marrant dedicated himself to helping others reach their religious potential. Through his published sermons and conversions, Marrant wanted to help humankind the best way he knew how: by giving them God’s lessons. Even though he never reaped an earthly reward in his lifetime, his works stand as a model for religious colonial life.

Andrews, William L. To Tell a Free Story: The First Century of Afro-American Autobiography, 1760–1865 (1988).

Gates, Henry Louis, Jr. The Signifying Monkey: A Theory of Afro-American Literary Criticism (1988).

Porter, Dorothy. Early Negro Writing, 1760–1837 (1971).

Potkay, Adam, and Sandra Burr, eds. Black Atlantic Writers of the Eighteenth Century: Living the New Exodus in England and the Americas (1995).

—DEVONA A. MALLORY

MARS, JAMES

MARS, JAMES(3 Mar. 1790–?), slave narrative author, was born in Canaan, Connecticut, the child of slaves. James’s father, Jupiter Mars, was born in New York State. He had a succession of owners, including General Henry Kiliaen Van Rensselaer, with whom Jupiter served in the Revolutionary War. He was subsequently owned in Salisbury, Connecticut, and later by the Reverend Mr. Thompson, a minister in North Canaan, Connecticut. James’s mother, whose name remains unknown, was born in Virginia and was owned there by the woman who became Thompson’s wife. His mother, who had one child while living in Virginia, was relocated to Connecticut when Mrs. Thompson moved to Canaan to join her husband. Reverend Thompson married Mars’s parents, and they had James and four other children, three of whom died in infancy.

Of Mrs. Thompson, James Mars told his father that “if she only had him South, where she could have at her call a half dozen men, she would have him stripped and flogged until he was cut in strings” (Mars, 5). The Thompsons eventually did move south, leaving the farm to be tended by Mars’s parents. In 1798, when James was eight years old, Thompson, who had always preached that slavery was divinely sanctioned, returned to Connecticut, intending to sell the farm and bring his slaves to the South for sale on the southern slave market. The Mars family—James’s mother, father, fourteen-year-old older brother Joseph, and younger sister—resisted by escaping to Norfolk, Connecticut. They went deeper into hiding when news arrived that Thompson had hired slave catchers to locate them and transport them to Virginia. After several days, during which the family successfully evaded recapture, Thompson decided to focus his attentions on Joseph and James, since they would bring the highest prices on the slave market.

Thompson, who originally refused to go to Virginia without the boys, eventually proposed a compromise by which Mars’s father would agree to sell his sons to owners in Connecticut in exchange for his freedom and that of his wife and daughter. Jupiter Mars was permitted to approve the men to whom his sons would be sold. On 12 September 1798, Joseph was sold to a farmer named Bingham (who had once owned Jupiter) and James was sold to a man named Munger from Norfolk. Thompson received one hundred dollars for each. Under the terms of the sale, the boys would be slaves until the age of twenty-five, the limit to which Connecticut law allowed slaves to be held. James’s parents and sister remained in Norfolk, and he was permitted to see them once every two weeks.

By the age of thirteen or fourteen, James had grown dissatisfied with his lack of education, his owner’s cruelty, and the terms of his servitude in comparison with the terms of indentured white boys, who were bound in service until they were twenty-one and who received one hundred dollars at the conclusion of their terms. On one occasion, when Mars was sixteen, Munger threatened to whip him, and Mars responded saying, “You had better not.” Munger backed down, and as Mars tells it, “From that time until I was twenty one, I do not remember that he ever gave me an unpleasant word or look” (Mars, 25). Mars was generally able to live as freely as any of the other boys who lived in the neighborhood.

For the next few years, Mars worked in relative contentment. “I was willing to work, and thought much of the family, and they thought something of me,” he later wrote (26). Munger seems not to have been aware that under Connecticut law he could hold Mars in his service after he turned twenty-one, and he made an offer to Mars on the condition that he would stay longer. Mars thought “the offer was tolerably fair. I had now become attached to the family” (27), but Munger withdrew the verbal offer after learning that he had the legal right to keep Mars as a slave until his twenty-fifth birthday, especially since no written agreement could be produced proving otherwise.

Mars was further disappointed when Munger reneged on an agreement to give him some livestock, and he threatened to leave unless Munger would put the agreement in writing. When Munger declined, Mars left the farm for his parents’ home. Munger asked Mars to return voluntarily. Instead, Mars and Munger agreed to abide by the decision of three mutually acceptable arbiters. The arbiters ruled that Mars should pay Munger ninety dollars for his freedom. After paying Munger, Mars hired himself out to another family, but after a four-year break he returned to work for the Munger family. After a trip west, he returned to find that Munger had suffered a decline in his fortunes and that his daughter was in poor health. Mars, “accustomed to take care of the sick” (31), remained with Munger’s daughter until she died peacefully soon after. “That was a scene that I love to think of. It makes me almost forget that I ever was a slave to her father; but so it was” (32). Although Mars worked where he chose for the next several years, he was frequently at the Munger home and remained in close contact with his former owner until he, like his daughter, died with Mars at his side.

Mars married after Munger’s death and fathered eight children. He lived in Norfolk and Hartford, Connecticut, and Pittsfield, Massachusetts. In the appendix to his narrative, Mars notes that his children followed a variety of vocations: one son enlisted in the U.S. Navy, another went to sea and fell out of touch with the family, a third enlisted in the navy at the beginning of the Civil War, and a fourth son enlisted as an artillery man and was most likely killed in the Civil War. One of Mars’s daughters went to Africa and became a teacher, and another moved to Massachusetts with her family.

What we know about James Mars comes entirely from his narrative Life of fames Mars, a Slave Born and Sold in Connecticut. Written by Himself, published in 1864. Mars indicates in his introduction that publication was not his intention when he began writing at his sister’s request during the Civil War. His sister, who had lived in Africa for more than thirty years, had been born in freedom and knew little of her parents and siblings’ experiences under slavery. Unlike the narratives published by escaped slaves who wrote, often with abolitionist sponsorship, with the intention of educating readers about the atrocities of the slave system and in the hopes of bringing about its end, Mars’s original intentions were entirely personal: “When I had got it written, as it made more writing than I was willing to undertake to give each of them [the members of his family] one, I thought I would have it printed, and perhaps I might sell enough to pay the expenses, as many of the people now on the stage of life do not know that slavery ever existed in Connecticut” (3). In addition to revealing the facts of his own life, Mars’s narrative contributes to our understanding of the lives of slaves in the North as well as the peculiarities of slavery in the North. It provides a rare illustration of the economic and social disparities and the grave distinction between the freedom promised by the North and the actual social and economic limitations imposed upon blacks in northern states.

Mars reports that at the age of seventy-nine, he was living on meager savings and unable to work because of a fall he experienced in 1866. He intended his narrative as a testament to the experiences of other slaves who labored in Connecticut, a place that many readers were unaware ever countenanced slavery. Despite the restrictions imposed by the state of Connecticut, Mars tells his readers, he had voted in five presidential elections and twice voted for Abraham Lincoln. Mars concludes his narrative with a condemnation of his home state: “If my life is spared I intend to be where I can show that I have the principles of a man, and act like a man, and vote like a man, but not in my native State; I cannot do it there, I must remove to the old Bay State for the right to be a man. Connecticut, I love thy name, but not thy restrictions” (38). How long Mars lived after his memoir was reprinted in 1868 and the circumstances of his death remain unknown.

Mars, James. Life of James Mars, a Slave Born and Sold in Connecticut. Written by Himself (1864, reprinted in 1868); also published in African American Slave Narratives: An Anthology, ed. Sterling Lecater Bland Jr., vol. 3 (2001).

—STERLING LECATER BLAND JR.

MARSALIS, WYNTON

MARSALIS, WYNTON(18 Oct. 1961–), trumpeter, was born in Kenner, Louisiana, the second of six sons of Ellis Marsalis, a jazz pianist and teacher, and Dolores Ferdinand. He was named after the jazz pianist Wynton Kelly. Wynton Marsalis was raised in a musical family with his brothers, Branford (tenor and soprano saxophones), Delfeayo (trombone), and Jason (drums).

Marsalis began playing the trumpet at the age of six, starting on an instrument given to him by the bandleader and trumpeter Al Hirt, with whom his father was then playing. At age eight, he was playing in a children’s marching band and performing at the New Orleans Jazz and Heritage Festival. A prodigiously talented instrumentalist, Marsalis studied both jazz and classical music from an early age and at age twelve began classical training on the trumpet. His early musical experience was diverse and included playing in local marching bands, jazz groups, and classical youth orchestras. At high school he played first trumpet with the New Orleans Civic Orchestra. He made his professional debut at age fourteen in a performance of Haydn’s Trumpet Concerto with the New Orleans Philharmonic Orchestra.

In 1977 Marsalis’s performance at the Eastern Music Festival in North Carolina led to him being awarded the festival’s Most Outstanding Musician Award. In 1978, at age seventeen, he performed Bach’s Brandenburg Concerto no. 2 (on piccolo trumpet) with the New Orleans Symphony Orchestra. In the same year, Gunther Schuller admitted him to the summer-school program at the Berkshire Music Center at Tanglewood, in Lenox, Massachusetts, after he had auditioned with the same Bach concerto. Schuller recounted how Marsalis “soared right through it and didn’t miss a note” (Giddins, 158), afterward receiving the school’s Harry Shapiro Award for Outstanding Brass Player. In 1979 Marsalis was awarded a scholarship to the Juilliard School of Music in New York City. At that time he also performed with the Brooklyn Philharmonic and the Mexico City Symphony orchestras as well as playing in the pit band for Stephen Sondheim’s Broadway musical Sweeney Todd.

In 1980, with a leave of absence from Juilliard, Marsalis joined ART BLAKEY’s Jazz Messengers. He then toured in a quartet led by Herbie Hancock, performing at the Newport Jazz Festival and on the album Herbie Hancock Quartet (1981). In 1983 Marsalis appeared again with Hancock in a quintet that included his brother Branford. By 1982 Marsalis was touring extensively with his own quintet and appearing at such venues as the Kool Jazz Festival at Newport and with the Young Lions of Jazz in New York. In London at the end of the year he appeared at Ronnie Scott’s club and made his first classical recordings: trumpet concertos by Haydn, Hummel, and Leopold Mozart, with Raymond Leppard and the National Philharmonic Orchestra. Also in 1982 he recorded his debut album as leader, Wynton Marsalis. In the same year, he won the Jazz Musician of the Year Award in Down Beat’s readers’ poll. In 1984 Marsalis undertook a classical tour, playing with orchestras across the United States and Canada. Also in 1984 he became the first (and only) musician to win Grammy Awards in both jazz and classical categories, taking Best Soloist for his jazz album Think of One, and Best Soloist with Orchestra for the concerto set with Leppard. He won both awards again the following year.

Trumpeter Wynton Marsalis, himself a jazz traditionalist, has spurred debate on “what jazz is—and isn’t.” Corbis

By the middle of the decade Marsalis was recording prolifically and accumulating significant awards and prizes. This period saw the release of Hot House Flowers (1984), Black Codes (from the Underground) (1985), and J Mood (1986). Subsequent recordings included the first volume of the Standard Time series (1987), Live at Blue Alley (1988), The Majesty of the Blues (1989), the three-volume Soul Gestures in Southern Blue (1991), and Blue Interlude (1992). In 1992 Marsalis became artistic director of jazz at New York’s Lincoln Center and leader of its Jazz Orchestra (LCJO).

In 1997 he was awarded the Pulitzer Prize for Music for his “oratorio,” Blood on the Fields, which was commissioned by Lincoln Center and premiered there with the LCJO in 1994. Jazz musicians had hitherto been ineligible for the award—it was denied to DUKE ELLINGTON in 1965—and it was a measure of Marsalis’s distinction, and the enhanced prestige of jazz, that he should be the first to receive the award. The oratorio, about American slavery, was self-consciously Ellingtonian in style, theme, and scope, recalling Ellington’s 1943 suite, Black, Brown and Beige.

In addition to his jazz albums, Marsalis has made several classical recordings: Baroque Music for Trumpets (1988), a collection of orchestral works by Vivaldi, Telemann, and Biber, with Raymond Leppard and the English Chamber Orchestra (ECO); On the Twentieth Century . . . (1993), with Judith Lynn Stillman (piano), including works by Ravel, Honegger, Bernstein, and Hindemith; and In Gabriel’s Garden (1996), with Anthony Newman and the ECO, featuring orchestral works by Mouret, Torelli, Charpentier, and Jeremiah Clarke. Marsalis also composed for dance: in collaboration with Garth Fagan for Citi Movement (1993); with Peter Martins and Twyla Tharp for the ballet works on Jump, Start and Jazz (1997); and with JUDITH JAMISON of the ALVIN AILEY American Dance Theater (Sweet Release), and the Zhong Mei Dance Company (Ghost Story), issued together as Sweet Release & Ghost Story (1999). His first composition for string quartet, At the Octoroon Balls (1999), was performed by the Orion String Quartet conducted by Marsalis.

Although Marsalis has enjoyed phenomenal success as a practicing musician, it is his concomitant “ambassadorial” role that has made him such a crucially significant figure in jazz. An indefatigable writer, broadcaster, educator, and administrator, he has assumed a position of unprecedented authority in shaping the meaning and value of jazz, particularly through his influential position at Lincoln Center. No one has done more than Marsalis to validate the artistic status of jazz and popularize its cultural standing. An unstinting proselytizer for jazz, he has embraced a pedagogical role through school programs, lectures, workshops, and master classes in addition to the Lincoln Center’s education and performance programs and through his involvement with television and radio series, such as PBS’s Marsalis on Music (1995), NPR’s Making the Music (1995), and Ken Burns’s PBS series Jazz (2001). In these endeavors, he found a firm ally and mentor in ALBERT MURRAY, the critic and author, who is also on the board of Jazz at Lincoln Center.

Marsalis’s ascendancy as jazz’s quasi-official spokesperson occurred during a period in which the condition of jazz appeared in disarray; his star was rising when jazz criticism was increasingly concerned with the compromised integrity of contemporary jazz. Critics complained that jazz had fragmented into hybridized, bastardized subcategories (like fusion), forms corrupted by ersatz electronic instrumentation and produced by MILES DAVIS and other musicians, who were seen to have “sold out” their jazz credentials. Marsalis sought to “reclaim” jazz from what he saw as the depredations of a commercialized popular culture (pop, rap, hip-hop) that had led to its marginalization. Hence, he has advocated a “neoclassical” agenda and subsequently has been both praised and criticized for playing the predominant role in what was often described as a “jazz renaissance” (Sancton, 66). Impeccably attired in retro-tailoring, he is, in himself, reminiscent of swing-era iconography.

Drawing on critical perspectives from his mentor and champion, Stanley Crouch, Marsalis’s polemical writing has insistently repudiated the white romantic conception of jazz’s “down” status as the imputed cultural expression of black lowlife. Marsalis also rejects the spurious stereotype of black musicians’ intuitive primitivism, which he calls “the noble savage cliché” (Marsalis, 21, 24). For Marsalis, jazz is—was—a cultural form of the highest order, and he has worked assiduously to safeguard its “purism” through his emphasis on the centrality of a highly selective canonical jazz tradition. With an emphasis on jazz purism, rather than its pluralism, Wynton Marsalis has marked out the parameters of “what jazz is—and isn’t.”

Marsalis, Wynton. “What Jazz Is—and Isn’t.” New York Times (31 July 1988): 21, 24.

_______, and Frank Stewart. Sweet Swing Blues on the Road (1994).

_______, and Carl Vigeland. Jazz in the Bittersweet Blues of Life (2000).

Giddins, Gary. “Wynton Marsalis and Other Neoclassical Lions.” Rhythm-a-ning: Jazz Tradition and Innovation (2000), 156–161.

Gourse, Leslie. Wynton Marsalis: Skain’s Domain: A Biography (1999).

Sancton, Thomas. “Horns of Plenty.” Time (22 Oct. 1990): 64–71.

Seidel, Mitchell. “Profile: Wynton Marsalis.” Down Beat 49, no. 1 (Jan. 1982): 52–53.

Discography

Wynton Marsalis (1982, Columbia 37574).

Black Codes (From the Underground) (1985, Columbia 40009).

Blood on the Fields (1977, Columbia 57694).

—IAN BROOKES

MARSHALL, KERRY JAMES

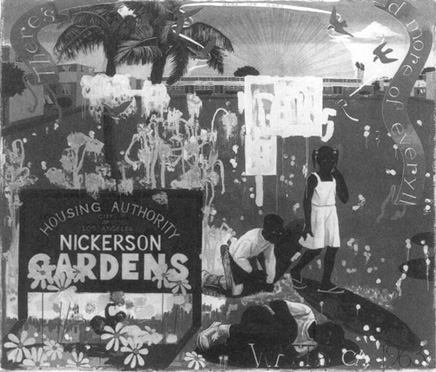

MARSHALL, KERRY JAMES(17 Oct. 1955–), painter, photographer, printmaker, and installation artist, was born in Birmingham, Alabama, the second son of James Marshall, a Postal Service worker, and Ora Dee Prentice Marshall, a songwriter and entrepreneur, both of Birmingham. Marshall’s family moved to Los Angeles in 1963, living in the Nickerson Gardens public housing project in Watts before settling in South Central Los Angeles.

Winner of a MacArthur Foundation Award, Kerry James Marshall created Watts 1963 as part of his 1995 Garden Series. Watts comments on the hopes associated with the “gardens” of housing projects built after the Korean War and the disappointment brought on by their decay. St. Louis Art Museum

Marshall’s artistic inclinations were kindled by a kindergarten teacher at Birmingham’s Holy Family Catholic School, who kept a picture-filled scrap-book for her young charges. This image compendium fed Marshall’s obsession with making art. Impressed by his creativity and drive, his elementary, junior high, and high school teachers encouraged him with special opportunities. Marshall learned his first painting techniques from his third grade teacher. Later, an art instructor at George Washington Carver Junior High introduced Marshall to the Los Angeles County Museum of Art and a special summer drawing class taught by George De Groat at Otis Art Institute. There Marshall saw the book Images of Dignity: The Drawings of Charles White. White’s drawings depicting realistic African American subjects with aesthetic richness and highly charged emotion inspired Marshall to reflect his own experiences in art. De Groat took his class to visit White’s studio, where Marshall had his first encounter with a living artist. After meeting White, who was on the faculty at Otis, Marshall determined to attend college there.

Marshall embarked on a self-tutorial to develop his figure-drawing skills. Drawings made when he was about fifteen years old show his emerging technical proficiency. He created his own workspace in the family garage, complete with easel and still-life set-ups. In this “studio” he experimented with egg tempera and made his own charcoal and ink. In the summer of 1972, just before his final year of high school, Marshall enrolled in a Saturday adult painting class at Otis. His instructor, the painter and animator Sam Clayberger, showed Marshall how to analyze pictorial structure. During his final year in high school, Marshall also attended Charles White’s life-drawing class at Otis. These artists remained a significant mentoring influence on Marshall, who spent two years after high school graduation in 1973 working as a dishwasher and then for a flooring company. In his spare time he painted in his garage studio and audited White’s and Clayberger’s classes.

College was not a foregone conclusion in Marshall’s family; on reaching majority children were expected to earn a living. In fact, with the exception of his Otis experiences, Marshall was not immediately aware of higher education opportunities. Laid off from the flooring company in 1975, he approached Otis about enrollment and discovered that he needed two years of liberal arts education to enroll. He registered at Los Angeles City College, planning to transfer to Otis as a third-year student, which he did in 1977. Clayberger had given Marshall a glimpse of the kind of education he dreamed of—one based on inquiry, skills, knowledge, and standards. While attending Otis, though, Marshall began to realize that traditional practices and techniques had been subsumed by conceptual and theoretical approaches—notions that were in conflict with Marshall’s ideals about formal art education. His discontent with Otis was instrumental in his subsequent formulation of a pedagogical approach emphasizing definition and clarification of skills through the acquisition of knowledge, standards, judgments, and values.

The painter and draftsman Arnold Mesches was Marshall’s most challenging influence at Otis, urging Marshall to expand his artistic horizons. His entire senior year was occupied with creating a collage series loosely based on the work of ROMARE BEARDEN. The first, entitled Thirty Pieces of Silver, symbolically portrayed the artist as Judas with a wide grin. This grin quickly became a signature element in his paintings. After graduation in 1978, Marshall applied to the government-sponsored Comprehensive Employment Training Act program for cultural employment and training opportunities through Brockman Art Gallery and was assigned to Mesches as a paid studio assistant.

In 1980 Marshall created Portrait of the Artist as a Shadow of His Former Self, a painting he feels was his first to unify completely process and meaning. Portrait signals the beginning of his signature style of the highly stylized, streamlined iconic black persona, rendered in pure black paint, with barely discernible features, except for gleaming white eyes and teeth. A series of paintings featuring stylized black figures followed. These works were exhibited at the art gallery at Los Angeles Southwest College, and on the strength of this show Marshall secured a part-time teaching job there. Additional works from this series were featured in his first commercial gallery exhibition, at James Turcotte Gallery in Los Angeles; the show was reviewed positively by the L.A. Times critic William Wilson. Marshall’s professional career developed quickly: in 1985 he had his first solo exhibition, at Koplin Gallery in Los Angeles; that same year he was awarded a resident fellowship at the Studio Museum in Harlem. Packing his possessions in a Volkswagen van, he set off with the intention of moving to New York permanently. However, in New York he met his future wife, the Chicago native and actress Cheryl Lynn Bruce. After completing the residency and working for a few months at the print publishers Chalk & Vermillion, he followed Bruce to Chicago in 1987. They married in April 1989.

Also in 1987 Marshall began working with the cinematographer Arthur Jaffa and his wife, the director Julie Dash, as production designer for Dash’s film Daughters in the Dust (1989). Marshall collaborated with Dash and Jaffa on several additional film projects (Hen-drix Project and Praise House, both from 1991); he also worked with Haile Gerima on Sankofa (1990). Meanwhile, his work as a visual artist progressed. From his first Chicago residence, a 6 x 9 foot room at the Chicago YMCA, he moved with Bruce into an apartment in Hyde Park. Marshall’s larger space allowed him to increase the scale of his work dramatically. Large-scale narrative paintings were the focus of a second show at Koplin (1991) and the basis for his successful National Endowment for the Arts (NEA) Visual Art Fellowship grant application. Receiving NEA support was a major career milestone, allowing him to establish his first professional studio outside his home.

The painting The Lost Boys (1993) epitomized his next period of artistic growth. Marshall believes that it was in this artwork that he achieved the surface beauty and compositional sophistication he had been striving for. With this work, he began to think in terms of larger narrative series, or installations, rather than individual pictures. The year 1993 marked his first participation in museum exhibitions (Corcoran Gallery of Art in Washington, D.C., and the Museum of Modern Art in New York). He also had his first New York gallery show, at the Jack Shainman Gallery, and received the prestigious Louis Comfort Tiffany Foundation award in painting. He began teaching at the School of Art and Design at the University of Illinois at Chicago, gaining full professorship and tenure in 1998. His first solo museum show, organized by the Cleveland Center for Contemporary Art in 1994, included a catalogue and a four-city tour.

For Marshall, 1997 was a banner year. He received the Alpert Award in the Arts and was given the prestigious MacArthur Foundation’s Fellows Program grant. He also was included in Documenta 10, that year’s edition of the important international art exhibition held every five years in Kassel, Germany. Marshall’s idea for a multifaceted project came to fruition in 1998 with Mementos, organized by the Renaissance Society, University of Chicago. His subject was broad: the tumultuous 1960s, loss, remembrance, and commemoration. Four mural-sized paintings entitled Souvenir formed the installation’s core. Additional components, including paintings portraying MARTIN LUTHER KING JR., John F. Kennedy, and Robert F. Kennedy; a video installation; free-standing sculptures in the shape of giant rubber stamps; and relief prints of popular slogans from the 1960s, such as “Black Is Beautiful” and “We Shall Overcome,” conveyed an overall sense of gravity and reverence.

Marshall explored social and political issues further in the show Carnegie International 1999/2000, at the Carnegie Museum of Art in Pittsburgh. His work Rythm Mastr consisted of hand-drawn and commercially printed comic-book-style narratives that were displayed in a site-specific installation incorporating exhibition cases normally used to show fragile artifacts. These cartoons were later published as a supplement to the Sunday Pittsburgh Post-Gazette. As a professional artist, Marshall has always sought to create works that commingle the aesthetics and sociology of African American popular culture. With Rythm Mastr he deftly conjoined the worlds of popular culture and fine art. In 1999, twenty-one years after he entered the program, Otis conferred an honorary doctorate on Marshall in recognition of his creativity, dedication, and career achievements.

Marshall’s work is indicative of a significant development in twenty-first-century artistic discourse being practiced by a new generation of art makers: a concern with modern and postmodern art idioms combined with social and political content and a profound dedication to classical art traditions. His work is deeply rooted in the great tradition of representation and historical narrative painting, yet is imbued with personal expression and social awareness. Like other artists of his generation, such as Lorna Simpson, Glen Ligon, and Carrie Mae Weems, he has charted a new course based on the solid foundations of the past.

Holg, Garrett. “Stuff Your Eyes with Wonder.” ARTnews (March 1998).

Marshall, Kerry James, Terrie Sultan, and Arthur Jaffa. Kerry James Marshall (2000).

Reid, Calvin. “Kerry James Marshall.” Bomb (Winter 1998). Sultan, Terrie. Kerry James Marshall: Telling Stories (1994).

—TERRIE SULTAN

MARSHALL, PAULE

MARSHALL, PAULE(9 Apr. 1929–), writer, was born Valenza Pauline Burke in Brooklyn, New York, the second of three children of Barbadian immigrants Samuel Burke, a factory worker, and Ada (maiden name unknown), a domestic. As a child Marshall read the great British novelists Charles Dickens, William Makepeace Thackeray, and Henry Fielding. Their influence is especially apparent in her sense of setting and characterization.

Later, she discovered African American writers such as RICHARD WRIGHT and PAUL LAURENCE DUNBAR. The latter’s use of dialect helped to legitimate her use of the cadences and grammatical structures of the vernacular used by the Bajan women of her community. Marshall writes beautifully about these women and their language in her New York Review of Books essay “The Making of a Writer: From the Poets in the Kitchen” (1983).

As a young adult Marshall was greatly influenced by RALPH ELLISON’s Shadow and Act, which she has called her “literary bible,” and by GWENDOLYN BROOKS’S lone novel, Maud Martha. In addition, she claims JAMES BALDWIN as crucial to her formation as a writer and thinker. These three writers emerged as significant literary figures who received mainstream acclaim in the early 1950s. By the end of that decade, Marshall joined them as the newest and one of the most original voices of the time.

In 1948 Marshall entered Hunter College in New York City, but illness forced her to take time off from her studies. During her recuperation she began writing short stories. Marshall married her first husband, Kenneth Marshall, in 1950; nine years later she gave birth to her only child, a son, Evan Keith. Before long her artistic aspirations began to challenge her domestic life. In 1953 she graduated cum laude with a degree in English from Brooklyn College and was inducted into Phi Beta Kappa. Following graduation Marshall worked as a librarian at the New York Public Library while seeking work in journalism. As is the case with her fictional character Reena, in the novella of the same name, Marshall found that the sophisticated world of Manhattan magazine publishing was still closed to black writers unless they were already well known. Eventually, she joined the staff of Our World magazine, a black publication, as its only female correspondent. At Our World she encountered sexism in both her superiors and her colleagues, who voiced expectations that she would fail. Nonetheless, while at Our World, Marshall traveled extensively throughout the Caribbean and South America.

In 1954 Marshall published her first short story, “The Valley Between,” the story of a young white wife and mother who, in defiance of her husband, wants to continue her education and eventually pursue a career. The story chronicles the character’s ambition as well as her guilt. Marshall later said that she might have made her characters white in order to avoid having to confront the similarities between herself and her protagonist. Against her own husband’s wishes, Marshall enlisted the services of a babysitter so that she would have time to work on her writing. In 1959 she published her first and best-known novel, Brown Girl, Brownstones. In 1963 her marriage ended in divorce.

In Brown Girl, Brownstones Marshall renders the speech of a Brooklyn community of Bajan immigrants, as well as African American migrants from the South, with extraordinary beauty and poetry. Along with Gwendolyn Brooks’s Annie Allen and Maud Martha, Brown Girl, Brownstones—a portrait of Selina Boyce, a young, strong-willed girl—is one of the first books in American literature to concern itself with the interior life of a young black girl. In addition, Brown Girl, Brownstones is also the earliest novel to explore the intricacy of black mother-daughter relationships and one of the first to give such a complex portrait of a community of Caribbean immigrants.

In 1960 Marshall received a Guggenheim Fellowship, which she used to write a collection of four novellas titled Soul Clap Hands and Sing (1961). Each novella—“Barbados,” “Brooklyn,” “British Guiana,” and “Brazil”—presents an elderly man who has to come to terms with his meaningless life. The settings range from sites in the United States to Central America, the Caribbean, and South America. Marshall received an American Academy Arts and Letters Award for Soul Clap Hands and Sing.

Her next work, the exquisite, complex novel The Chosen Place, the Timeless People, is one of Marshall’s greatest accomplishments. Set in a fictional Caribbean nation, the novel explores a number of characters, black and white, male and female, North American, West Indian, and European. Through them, Marshall explores larger issues of power and dominance, colonialism, slavery, and neocolonialism. Perhaps most importantly, the novel introduces Merle Kinbona, an eccentric, educated, middle-aged, sensual, radical, intellectual black woman, and one of the most original and complex characters in contemporary fiction.

Fourteen years passed before the publication of Marshall’s next novel, Praisesong for the Widow (1983). During this creative hiatus she married Nourry Menard, a Haitian businessman. Praisesong continues Marshall’s portrayal of older women, her concern for characters who have lost their spiritual centers, and her exploration of the relationship between African American and Afro-Caribbean history. If her earlier work focused on specific locations, in Praisesong for the Widow she begins to include the Caribbean and Central and South America in her conception of the black South.

Marshall’s next novels turn to the children of diaspora. Daughters (1991), which received the Columbus Foundation American Book Award, is the story of Ursa MacKenzie, the buppie daughter of a West Indian politician father and a middle-class black woman from the United States. While these are her biological parents, her father’s mistress, a childless businesswoman, and his own nursemaid also mother her. But most significantly she is the daughter of Afro-diasporic history; in documenting that history, she gives birth to herself.

Marshall’s most recent novel, The Fisher King (2000), centers on a little boy, Sonny, who is a true child of the African Diaspora. His mother was raised in Paris and his father is a Senegalese street vendor in Paris. His maternal grandparents are two American expatriates, Sonny Rhett-Payne and a character modeled after LENA HORNE. One of his great-grandmothers is an aristocratic African American woman with roots in the deep South, and another is a stern West Indian woman; both of them live in brownstones on the same Brooklyn block. Thus, Sonny has roots throughout the African Diaspora, and as he is brought to live with his great-grandmothers in Brooklyn it is tempting to see that Marshall’s work has come full circle.

Since 1995 Marshall has divided her time between Richmond, Virginia, and New York City. She teaches creative writing at New York University, where she also introduced the Paule Marshall and the New Generation Reading Series. The series has featured a number of young writers before they achieved public acclaim. Among these are Edwidge Danticat, Colson Whitehead, Denzy Senna, and A. J. Verdelle. In 1993 she was awarded a MacArthur Foundation Fellowship.

Marshall is a cosmopolitan intellectual whose work traces the complex connections and conflicts among black people throughout the Americas. Long before academics turned their attention to the African diaspora or the “Black Atlantic,” Marshall mapped this terrain in novels, novellas, and short stories. Her experience as the child of immigrants, her childhood in a Brooklyn populated by blacks from the Caribbean and the American South, and her travels as an adult throughout the Americas all inform her artistic vision. Her literature underscores the relationship between slavery, colonialism, racism, and neocolonialism and the formation of the modern black subject.

Marshall, Paule. “From the Poets of the Kitchen,” New York Times Book Review (9 Jan. 1983), 3, 34–35.

DeLamotte, Eugenia C. Places of Silence, Journeys of Freedom (1998).

Denniston, Dorothy Hamer. The Fiction of Paule Marshall: Reconstructions of History, Culture, and Gender (1995).

Hathaway, Heather. Caribbean Waves: Relocating Claude McKay and Paule Marshall (1999).

Pettis, Joyce. Toward Wholeness in Paule Marshall’s Fiction (1995).

—FARAH JASMINE GRIFFIN

MARSHALL, THURGOOD

MARSHALL, THURGOOD(2 July 1908–24 Jan. 1993), civil rights lawyer and U.S. Supreme Court justice, was born Thoroughgood Marshall in Baltimore, Maryland, the son of William Canfield Marshall, a dining-car waiter and club steward, and Norma Arica Williams, an elementary school teacher. Growing up in a solid middle-class environment, Marshall was an outgoing and sometimes rebellious student who first encountered the Constitution when he was required to read it as punishment for classroom misbehavior. Marshall’s parents wanted him to become a dentist, as his brother did, but Marshall was not interested in the science courses he took at Lincoln University in Pennsylvania, from which he was graduated with honors in 1930. He married Vivian “Buster” Burey in 1929; they had no children.

Unable to attend the segregated University of Maryland Law School, Marshall enrolled in and commuted to Howard University Law School, where he became a protégé of the dean, CHARLES HAMILTON HOUSTON, who inspired a cadre of law students to see the law as a form of social engineering to be used to advance the interests of African Americans. After graduating first in his class from Howard in 1933, Marshall remained in Baltimore, where he opened a private law practice and struggled to make a living during the Depression. Marshall was active in the Baltimore branch of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP), and in 1936 Houston persuaded both the NAACP board and Marshall that Marshall ought to join him in New York as a staff lawyer for the NAACP. After Houston returned to Washington in 1938, Marshall remained and became the chief staff lawyer, a position he held until 1961.

Early in his Baltimore practice Marshall had decided to attack the policies that had barred him from attending the state-supported law school. Acting under Houston’s direction, Marshall sued the University of Maryland on behalf of Donald Murray. The Maryland state court’s 1936 decision ordering the school to admit Murray because the state did not maintain a “separate but equal” law school for African Americans was the first step in a two-decade effort to undermine the constitutional basis of racial segregation. Over the next fourteen years, Marshall pursued his challenge to segregated higher education through two main areas. In Missouri ex rel Gaines v. Canada (1938), a case Houston developed and argued, the U.S. Supreme Court directed the University of Missouri to either admit Lloyd Gaines to its law school or open one for African Americans. The attack culminated in Marshall’s case of Sweatt v. Painter (1950), in which the Supreme Court held that the law school Texas had opened for African Americans was / not “equal” to the well-established law school for whites.

The cases that the Supreme Court decided under the name Brown v. Board of Education constituted Marshall’s main efforts from 1950 to 1955. Assembling a team of lawyers to develop legal and historical theories against segregation, Marshall had his greatest triumph as a lawyer in Brown (1954), in which the Supreme Court held that segregation of public schools by race was unconstitutional. In the 1896 case of Plessy v. Ferguson, the Supreme Court had upheld segregation, saying that segregation was a reasonable way for states to regulate race relations and that it did not “stamp the colored race with a badge of inferiority.” Examining the background of the Fourteenth Amendment, Marshall’s team concluded that the amendment’s framers did not intend either to authorize or to outlaw segregation. From this research Marshall came to the conclusion that under modern conditions, given the place of education in twentieth-century life, segregated public education was no longer reasonable. Marshall also relied, though less heavily, on arguments based on the psychological research of KENNETH B. CLARK showing that, Plessy notwithstanding, segregation did in fact damage the self-images of African American school children. During oral arguments Marshall occasionally stumbled over technical and historical details, but his straightforward appeal to common sense captured the essence of the constitutional challenge: “In the South where I spend most of my time,” he said, “you will see white and colored kids going down the road together to school. They separate and go to different schools, and they come out and they play together. I do not see why there would necessarily be any trouble if they went to school together.”

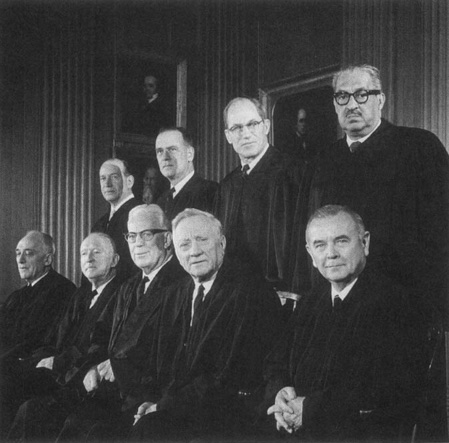

The Supreme Court Justices of 1967. Left to right, seated: Associate Justices John M. Harlan and Hugo L. Black, Chief Justice Earl Warren, William O. Douglas, and William J. Brennan Jr. Standing: Abe Fortas, Potter Stewart, Byron R. White, and Thurgood Marshall. Corbis

There was trouble, however, as officials in the deep South engaged in massive resistance to desegregation. Marshall argued the case of Cooper v. Aaron (1958), which arose after Arkansas governor Orval Faubus sought to circumvent desegregation by closing four Little Rock schools on the first day of class. Marshall pointed out that Faubus’s attempts to thwart the Supreme Court directive in Brown threatened fundamental American ideas about the rule of law, and he asked the Court to assert its constitutional authority by directing Little Rock officials to reopen and racially integrate the schools. Marshall told the justices that a ruling in favor of Faubus would be tantamount to telling the nine black boys and girls who had endured harassment and intimidation at Little Rock’s Central High School throughout the 1957–1958 school year, “You fought for what you considered democracy and you lost . . . . go back to the segregated school from which you came.” Again the Supreme Court agreed with Marshall, and in August 1959 the schools reopened in line with federal desegregation orders.

A gregarious person who was always ready to use an apt, humorous story to make a point, Marshall traveled throughout the segregated South to speak to teachers and NAACP members, and in the 1940s and 1950s he became a major civil rights leader. By the mid-1950s his role as a civil rights leader had superseded his work as an attorney and he had become a widely sought-after speaker and fund-raiser. He also was active in the Episcopal Church and the Prince Hall Masons. His wife died of lung cancer in February 1955, and the following December he married Cecilia Suyatt, a secretary in the NAACP’s national office; they would have two children, both boys.