NABRIT, SAMUEL MILTON

NABRIT, SAMUEL MILTON NABRIT, SAMUEL MILTON

NABRIT, SAMUEL MILTON(21 Feb. 1905–), biologist, university administrator, and public-policy maker, was born in Macon, Georgia, the son of James Madison Nabrit, a Baptist minister and educator, and Augusta Gertrude West. The elder Nabrit, who taught at Central City College and later at Walker Baptist Institute, encouraged his son to prepare for a career in higher education by studying Latin, Greek, and physics. Samuel rounded out his education by playing football and baseball, and honed his managerial and journalistic skills working on his high school (and later college) student newspaper. He entered Morehouse College in Atlanta in 1921, and after receiving a traditional liberal arts education, was awarded a BS in 1925. Samuel’s brother, James Madison Nabrit Jr., was an important aide in the NAACP’s legal team during the 1950s. Working closely with THURGOOD MARSHALL in his unsuccessful attempts to begin the desegregation of graduate and professional schools in Texas and Oklahoma, James later served as president of Howard University.

The precocious Nabrit’s college career was so successful that he gained the attention of Morehouse president JOHN HOPE, who recruited Nabrit to teach zoology. Beginning in 1925 Nabrit taught biology while he also worked on and earned an MS at the University of Chicago. He then pursued a doctorate at Brown University in Rhode Island under the tutelage of the distinguished zoologist J. W. Wilson, and during the summers between 1927 and 1932 he conducted research on the regeneration of fish embryos at the famed Marine Biological Laboratory at Woods Hole, Massachusetts. Despite his academic achievements, Nabrit was snubbed by the renowned African American zoologist ERNEST EVERETT JUST at Woods Hole, who believed that African Americans in the sciences had to prove themselves superior to their white peers in order to deserve recognition.

Nabrit was awarded his doctorate from Brown in 1932, making him the first African American to receive a PhD from that prestigious Ivy League institution. Furthermore, his research on regeneration was published in the renowned Biological Bulletin, and citations of his work appeared in such important scientific publications as the Anatomical Record, the Journal of Experimental Zoology, and the Journal of Parasitology. Indicative of the significance of his research, his groundbreaking contributions were still being cited as late as 1980.

After receiving his doctorate, Nabrit served in two administrative posts at Atlanta University for the next twenty-three years, first as chair of the department of biology, and then after 1947 as dean of the graduate school of arts and sciences. Nabrit’s most significant administrative contribution during his years as dean was his nurturing of the National Institute of Science, an organization founded in 1943 for the purpose of resolving research and teaching problems peculiar to African American scientists, most of whom were teaching at historically black colleges and universities. Nabrit also wrote articles and book reviews for journals, including Phylon, Science Education, and the Negro History Bulletin, in order to broaden the perspectives, opportunities, and expectations of African American scientists and mathematicians.

The capstone of Nabrit’s administrative career came in 1955, when he was appointed president of the fledgling, all-black Texas Southern University in Houston. Serving for more than a decade, Nabrit was also appointed to key national educational association committees. Moreover, his services were welcomed by federal officials in the U.S. Department of State and the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. Nabrit was appointed to the National Science Board by President Dwight D. Eisenhower in 1956. A decade later, President Lyndon B. Johnson appointed Nabrit to the highly controversial Atomic Energy Commission. Nabrit’s long and illustrious career ended in 1981, after a fifteen-year tenure as the director of the Southern Fellowship Fund.

Despite his numerous achievements, Nabrit experienced some disappointing moments. When Allan Shivers, the arch-segregationist governor of Texas, spoke at Texas Southern University in 1956, the integrationist NAACP protested during the ceremony. As the president of a state-supported all-black college dependent on people like Shivers for funding, Nabrit was inhibited from challenging the system of segregation or offering support to such demonstrations. Although Nabrit had supported Texas Southern students in their protest against the kidnapping and torture of Felton Turner in March 1960, he created a stir among African American activists when he warned Eldrewey Stearns, a prominent Houston reformer, about the use of college students as picketers at the Loew’s Theater in downtown Houston in 1961.

Nabrit, with his gradualist style of reform (an orientation similar to that of JAMES E. SHEPARD, president of the North Carolina College for Negroes), will be remembered for his concrete efforts to bring African Americans into the mainstream of American scientific and technical education.

Cole, Thomas R. No Color Is My Kind: The Life of Eldrewey Stearns and the Integration of Houston (1997).

Manning, Kenneth R. Black Apollo of Science: The Life of Ernest Everett Just (1983).

—VERNON J. WILLIAMS JR.

NELL, WILLIAM COOPER

NELL, WILLIAM COOPER(20 Dec. 1816–25 May 1874), abolitionist and historian, was born in Boston, Massachusetts, the son of William Guion Nell, a tailor, and Louisa (maiden name unknown). His father, a prominent figure in the small but influential African American community in Boston’s West End during the 1820s, was a next-door neighbor and close associate of the controversial black abolitionist DAVID WALKER. Nell studied at the all-black Smith School, which met in the basement of Boston’s African Meeting House. Although he was an excellent student, in 1829 he was denied honors given to outstanding pupils by the local school board because of his race. This and similar humiliations prompted him to dedicate his life to eliminating racial barriers. To better accomplish that task, Nell read law in the office of local abolitionist William I. Bowditch in the early 1830s. Although he never practiced, his legal skills and knowledge proved valuable in the antislavery and civil rights struggles of his era.

Nell naturally gravitated toward the emerging abolitionist crusade. In 1831 he became an errand boy for the Liberator, the leading antislavery journal, beginning a long and close relationship with its editor, William Lloyd Garrison. His talents were quickly recognized, and he was soon made a printer’s apprentice, then a clerk in the paper’s operations. In the latter position, which he assumed in 1840, he wrote articles, supervised the paper’s Negro Employment Office, arranged meetings, corresponded with other abolitionists, and represented Garrison at various antislavery functions. The pay was low, so he was forced to supplement his income by advertising his services as a bookkeeper and copyist. But he remained one of Garrison’s most ardent supporters, even as the Boston abolitionist grew increasingly controversial because of his singular devotion to moral rather than political means and his embrace of a wide variety of reforms.

After the antislavery movement divided into two hostile camps in 1840 over questions of appropriate tactics and women’s role, Nell vehemently criticized those black abolitionists who parted company with Garrison. He moved to Rochester, New York, in 1848 and helped FREDERICK DOUGLASS publish the North Star. But when growing conflict between Garrison and Douglass forced him to choose sides, he returned to Boston and the Liberator. In 1856 Nell traveled through lower Canada West (now Ontario) and the Midwest, visiting black communities, attending anti-slavery meetings, and submitting regular reports to the Liberator. His accounts of this journey are a useful record of African American life in those areas at the time.

Nell was perhaps the most outspoken and consistent advocate of racial integration in the antebellum United States. He worked closely with white reformers and regularly pressed other blacks to abandon “all separate action, and becom[e] part and parcel of the general community” (Smith, 184). Nell participated in a statewide campaign to end segregated “Jim Crow” cars on Massachusetts railroads in the early 1840s. He used the antislavery press as a vehicle to attack black exclusion from or segregation in churches, schools and colleges, restaurants, hotels, militia units, theaters, and other places of entertainment.

From 1840 to 1855 Nell led a successful petition campaign to integrate the public schools of Boston, which ended when the Massachusetts legislature outlawed racially separate education in the state. He even opposed the existence of voluntary separatism among African Americans. In 1843 he represented Boston at the National Convention of Colored Citizens in Buffalo and used that forum as a vehicle to speak out against exclusive black gatherings and activism. An outspoken critic of the black churches, he often attended the predominantly white Memorial Meeting House in West Roxbury.

But Nell supported separate black organizations when they met needs not performed by integrated ones. For example, in 1842 he helped establish the Freedom Association, a local black group founded to aid and protect fugitive slaves. He remained active in this group for four years until the interracial Boston Vigilance Committee was founded for the same purpose. Although he established numerous cultural and literary societies—most notably the Adelphic Union and the Boston Young Men’s Literary Society—among Boston blacks after 1830, these were always open to individuals of every race and class.

Nell tempered his opposition to politics and exclusive black activism in the early 1850s. He was nominated by the Free-Soil party for the Massachusetts legislature in 1850. After the Fugitive Slave Act of 1850 was passed, he stepped up his role in local Underground Railroad activities until illness forced his temporary retirement from the antislavery stage.

About this time Nell began extensive research on the African American experience in the United States. He perceived that black history and memory would help shape the identity of his race and advance the struggle against slavery and racial prejudice. His research resulted in the publication of Services of Colored Americans in the Wars of 1776 and 1812 (1851), Colored Patriots of the American Revolution (1855), and dozens of articles and pamphlets. The careful scholarship and innovative use of oral sources in Nell’s works, which were far broader than their titles suggest, made them the most useful and important histories of African Americans written in the Civil War era.

Nell’s historical activism also took a more popular turn. In 1858 he organized the first of seven annual CRISPUS ATTUCKS Day celebrations in Boston to honor African American heroes of the American Revolution. Held the fifth day of every March in Faneuil Hall, the festivities consisted of speeches, martial music, displays of revolutionary war relics, and the recollections of aged black veterans. These gatherings symbolically rejected the decision of the U.S. Supreme Court in Dred Scott v. Sand-ford (1857), which unequivocally denied black claims to American citizenship. Nell also petitioned the Massachusetts state legislature on numerous occasions for an Attucks monument in Boston.

When the Civil War came, Nell embraced the Union cause, anticipating the end of slavery and racial inequality in American life. His hopes were buoyed in 1861, when he was employed as a postal clerk in the Boston post office. This made him the first African American appointed to a position in the U.S. government, and he held the job until his death. He was further encouraged by the Emancipation Proclamation and the decision to enlist black troops in the Union army.

The end of the war brought a series of personal changes for Nell. When the Liberator ceased operations in December 1865, it marked the denouement of Nell’s lengthy career in reform journalism. But it did not mean the abandonment of activism; during the late 1860s he waged a successful campaign to end racial discrimination in theaters and other public places in Boston. Nell married Frances A. Amers of New Hampshire in 1869; they had two sons. He spent the remainder of his life completing a study of African American troops in the Civil War. It was apparently unfinished when he died in Boston of “paralysis of the brain.”

Nell’s published letters and editorials are available in the microfilm edition of The Black Abolitionist Papers, C. Peter Ripley, ed.

Horton, James O. “Generations of Protest: Black Families and Social Reform in Ante-Bellum Boston.” New England Quarterly 94 (1976): 242–256.

Horton, James O., and Lois E. Horton. Black Bostonians: Family Life and Community Struggle in the Antebellum North (1979).

Smith, Robert P. “William Cooper Nell: Crusading Black Abolitionist.” Journal of Negro History 55 (1970): 182–199.

Wesley, Dorothy Porter. “Integration versus Separatism: William Cooper Nell’s Role in the Struggle for Equality” in Courage and Conscience: Black and White Abolitionists in Boston, ed. Donald M. Jacobs (1993).

Obituary: Pacific Appeal (San Francisco), 18 July 1874.

—ROY E. FINKENBINE

NEWTON, HUEY P.

NEWTON, HUEY P.(17 Feb. 1942–22 Aug. 1989), leader of the Black Panther Party, was born Huey Percy Newton in Monroe, Louisiana, the son of Amelia Johnson Newton and Walter Newton, a sharecropper and Baptist preacher. Walter Newton so admired Louisiana’s populist governor Huey P. Long that he named his seventh and youngest son after him. A proud, powerful man, Newton defied the regional convention that forced most black women into domestic service and never allowed his wife to work outside the home. He always juggled several jobs to support his large family. Like thousands of black southerners drawn to employment in the war industries, the Newtons migrated to California during the 1940s. Settling in Oakland, the close-knit family struggled to shelter young Huey but could not stop the mores of the ghetto from shaping his life. Years later, those same ghetto neighborhoods became the springboard of the Black Panther Party that thrust Newton into national prominence.

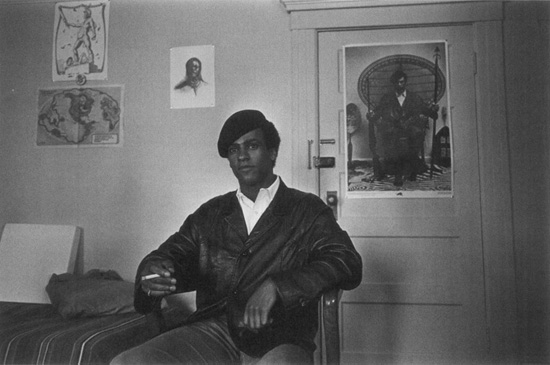

Huey Newton, shown here in 1967 at the headquarters of the Black Panther Party, which he founded with BOBBY SEALE in 1966. © Ted Streshinsky/CORBIS

While attending Oakland’s Merritt College, Newton met BOBBY SEALE, a married student recently discharged from the army, when they became involved in developing a black studies curriculum. Discovering that they both felt impatient with student activism in the face of blatant discrimination and police violence, the two formed a new organization in October 1966. Adopting the symbol of the all-black political party in Lowndes County, Alabama, that Black Power spokesman STOKELY CARMICHAEL had helped organize, they named their organization the Black Panther Party for Self-Defense.

Seale and Newton wrote out a ten-point platform and program for the group, demanding as its first point “power to determine the destiny of our black community.” The program outlined aspirations for better housing, education, and employment opportunities and called for an end to police brutality. It insisted that blacks be tried by juries of their peers, that all black prisoners be released because none had received fair trials, and that blacks be exempted from military service. It concluded with a quotation from the Declaration of Independence asserting the right to revolution.

Initiating patrols to prevent abusive behavior by local police, the disciplined, uniformly dressed young Panthers immediately attracted attention. Wearing black leather jackets and black berets, the men and women openly carried weapons on their patrols. These acts were legal under the gun laws then in force, but the California legislature swiftly acted to prohibit the patrols in July 1967.

The Black Panthers were buoyed along by the current of dissent and protest surging through black communities. As in other urban areas, Oakland’s black families felt a deep sense of injustice at the treatment meted out by the police, and the Black Panther Party continued to attract members. In October 1967 Newton was wounded following a late-night traffic stop in which Oakland police officer John Frey was killed. Upon his arrest, the startling news that the minister of defense of the Black Panther Party was accused of killing a white policeman was broadcast nationally. Police killings of black youths had triggered numerous riots and urban uprisings, but in all the previous incidents no policemen had been killed. Newton’s indictment for murdering Frey threw a spotlight over Oakland’s Black Panther Party. Soon, Charles R. Garry, a prominent San Francisco trial attorney, took up Newton’s legal defense, and the Black Panther’s minister of information, ELDRIDGE CLEAVER, initiated the “Free Huey” movement that made Newton internationally famous.

Newton’s case became the centerpiece of a massive mobilization campaign advocating the Black Panther Party program. Membership soared. During the murder trial in the summer of 1968, a fateful year marked by the assassinations of the Reverend MARTIN LUTHER KING JR. and U.S. senator and presidential candidate Robert Kennedy, thousands of supporters flocked to rallies outside the Oakland courthouse. The international effort in defense of Newton succeeded in blocking his conviction (and execution) for murder, but the jury found him guilty of manslaughter.

Newton openly advocated revolutionary changes in the relationship between poor blacks and the larger white society and concentrated on the untapped potential of what he called the urban “lumpen proletariat” to forge a vanguard party. The “Free Huey” movement galvanized blacks, resulting in phenomenal growth and the development of a national Black Panther Party buoyed by the rallying cry “All Power to the People!” The Panthers advocated self-determination to replace the racist, economic subjugation of blacks they viewed as “colonialism.” By the time Newton was released following a successful appeal in 1970, the Black Panther Party had offices in more than thirty cities, including New York, Philadelphia, Chicago, and Los Angeles. It had established an international section in Algeria and inspired the creation of similar organizations in Israel, the West Indies, and India.

As were numerous leaders and members of the Black Panther Party, Newton was subjected to nearly constant surveillance, police harassment, frequent arrests, and a barrage of politically inspired invasions of privacy. He faced two retrials on the manslaughter charge but was never again convicted of killing Frey (both trials ended in hung juries). In the meantime, Panther leaders in Los Angeles and Chicago were shot to death in 1969 under circumstances in which special police units worked secretly with federal intelligence agents—many of the criminal charges brought against Panthers resulted from clandestine police-FBI collaborations engineered by COINTELPRO (the U.S. government’s counterintelligence program). Between 1968 and 1973, thousands of Panthers were arrested, hundreds were tried and imprisoned, while thirty-four were killed in police raids, shoot-outs, or internal conflicts.

Newton’s symbolic appeal to young blacks was powerful, especially because of the defiant resistance to police authority he represented. Such conduct had never been so central to any previous black leader, and it shocked many who were accustomed to a more restrained demeanor. Newton, who often expressed the belief that it was crucial “to capture the peoples’ imagination” in order to build a successful revolutionary movement, was more effective as a catalyst than as a traditional leader. Newton was not an especially captivating speaker or skilled political organizer; rather his talent lay in inspiring a small group of exceptionally talented individuals, directing their energies, and eliciting a loyalty so profound that they were willing to risk their lives building the revolutionary organization he founded.

The unique way the Black Panther Party fused conflicting elements within one organization paid tribute to Newton’s vision. Free breakfasts for schoolchildren and other programs provided community service, but unlike other reformers, the Panthers also simultaneously engaged in electoral politics and challenged the imperialist domination of blacks—all with a flamboyant bravado. While the traditional civil rights organizations sought “first-class citizenship,” the Panthers viewed the legacy of slavery, segregation, and racism as a form of colonialism in which blacks were subjects, not citizens of the United States; instead of seeking integration, the Panthers identified with the struggles of other colonized Africans and Asians, and sought black liberation.

The Black Panthers were not ideologically consistent over time; the party moved from a nationalism inspired by MALCOLM X to a Marxist anti-imperialism influenced by Frantz Fanon, Che Guevara, and Mao Tse Tung and finally into a synthesis that Newton called “intercommunalism,” which he claimed was required by the collapse of the nation state within the global economy. Although the Black Panthers remained an all-black organization, it forged coalitions with other radical groups involving whites, Asians, and Latinos. The volatile mixture of external repression, internal dissension, and an escalating use of purges led to several highly publicized expulsions that divided the governing central committee.

Precipitated by Newton’s denunciation and expulsion of Eldridge Cleaver and the entire International Section in February 1971, the Black Panther Party broke into rival factions, a division the press named the “Newton-Cleaver split.” The factions were loosely defined by ideological differences. Whereas the Newton-controlled portion of the party abruptly backtracked and began to advocate moderate solutions to black oppression—and ceased to attract new members—those opposing Newton escalated their devotion to revolutionary tactics and coalesced around a network of freedom fighters who eventually formed the underground Black Liberation Army.

An increasingly paranoid Newton took bold steps to consolidate his personal supremacy over the volatile organization, and as chapters dwindled or were closed, he introduced the “survival pending revolution” program. While the Panthers publicly engaged in conventional political and economic activities, Newton, who had become heavily addicted to cocaine, led the organization into subterranean criminal activities. Following indictments brought against him for assaulting several Oakland residents, including a prostitute who later died, Newton fled to Cuba in 1974. He left behind an organization virtually in shambles, saddled with an Internal Revenue Service investigation into its finances, and dwindling numbers of supporters. Even party chairman Bobby Seale repudiated the unsavory developments and left the organization.

En route to Cuba, Newton married his secretary, Gwen Fontaine. Following his return in 1976, Newton was tried on assault and murder charges but was not convicted. He then enrolled in the History of Consciousness program on the Santa Cruz campus of the University of California. He received his PhD from that program in 1980, by which time the Black Panther Party had virtually disbanded. Although a small retinue of supporters continued to be drawn to Newton’s strong personal magnetism, he ceased to function as the leader of a revolutionary movement. By 1982 his marriage had ended in divorce and the last vestige of the Black Panther Party, its Youth Institute, had closed for lack of funds.

Newton married Frederika Slaughter of Oakland in 1984. His repeated efforts to overcome alcohol and cocaine addiction were not successful, and he briefly spent time in prison in 1987 for a probation violation. Early on the morning of 22 August 1989 Newton was shot and killed in Oakland by a twenty-five-year-old crack dealer whom he had insisted give him drugs free because of who he was. Newton’s flamboyance, vision, and passion came to symbolize an entire era, yet in the end, the same demons that ravaged the community he had sought to transform destroyed him as well.

Huey P. Newton’s papers, which include a significant amount of legal material, are housed at the Department of Special Collections, Stanford University Library.

Newton, Huey P. Revolutionary Suiàde (1973; repr. 1995).

Hilliard, David, and Don Weise, eds. The Huey P. Newton Reader (2002).

Jeffries, Judson L. Huey P. Newton: The Radical Theorist (2002)

Keating, Edward M. Free Huey (1970).

Van Peebles, Mario, with Ula Y. Taylor and J. Tarika Lewis. Panther (1995).

Obituary: New York Times, 23 Aug. 1989.

—KATHLEEN N. CLEAVER

NIGGER ADD

NIGGER ADD(1845?–24 Mar. 1926), cowboy, roper, and bronc rider, also known as Negro Add or Old Add, was born Addison Jones, reportedly in Gonzales County, Texas; his father and mother are unknown. The early life of Add is clouded in conjecture. He may have been a slave on the George W. Littlefield plantation in Panola County, Mississippi, and relocated with the Littlefields when they settled in Gonzales County, Texas, in 1850. It is also possible that he was born in Gonzales County and was purchased by the Littlefields after they arrived. There is no record of his youth and early adulthood.

There are many stories about Add in cowboy memoirs and biographies, but the only name given is Nigger Add or Old Negro Add. It apparently seemed of little consequence in cowboy country that Add had a last name. (Addison Jones’s full name was revealed in print for the first time by Connie Brooks in 1993.) Contemporaries who spoke or wrote about Add agreed, however, that he was an outstanding cowboy and bronc buster. Vivian H. Whitlock, who cowboyed with Add for several years on the LFD ranch in Texas and eastern New Mexico, called him “the most famous Negro cowpuncher of the Old West.” J. Evetts Haley, biographer of George W. Littlefield, called him “the most noted Negro cowboy that ever ‘topped off a horse.”

Add’s reputation with horses was due to his ability, as he used to say, “to look a horse square in the eye and almost tell what it was thinking” and to ride every horse he saddled, with one exception. Add is reported to have been thrown only by a bronc named Whistling Bullet. In typical cowboy fashion Add tried Whistling Bullet again, and according to Pat Boone, a district judge in Littlefield, Texas, he was the only man to ride him.

While the work of “taking the first pitch out of a bronc” often fell to black cowboys, Add performed this task with a special skill, daring, and raw nerve. Several cowboys commented that they saw Add perform this feat on various occasions. According to Haley,

He would tie a rope hard and fast around his hips, hem a horse up in the corner of a corral or in the open pasture, rope him around the neck as he went past at full speed, and where another man would have been dragged to death, Add would, by sheer skill and power on the end of a rope, invariably flatten the horse out on the ground.

(184)

Cowboys from neighboring ranches often worked round-ups together, and Add, who was known and respected by ranchers and cowboys of eastern New Mexico and West Texas, was a familiar sight. N. Howard “Jack” Thorp, noted cowboy song collector and songwriter, spoke of camping with Add and a group of black cowhands from South Texas in March 1889 at the beginning of his first song-hunting trek. Later Thorp helped to ensure Add’s place in history by writing a cowboy song titled “Whose Old Cow?” that in a humorous fashion recognized Add’s ability to identify earmarks and brands.

As cowboys gained experience in the cattle business, they rose from the rank of tenderfoot to top hand or even range boss or foreman. Thorp, in fact, referred to Add as the LFD outfit’s range boss. West Texas black cowboys, however, had little chance to pass cowboy status, as was suggested by Whitlock: “He [Add] was a good cowhand, but because of the custom in those days, never became what was known as a ‘top’ hand.” There also was a certain unwritten yet generally understood deference black cowboys were expected to extend to their white counterparts. This situation was the legacy of slavery, which crossed the frontier with the settlers, ranchers, and cowboys. A black cowboy who challenged those traditions did so at his peril.

Add at various times came up to that line and sometimes crossed it. One white cowboy, Mat Jones, said that Add was “a privileged character” (Fiddle-footed [1966]). This may have referred to the fact that he was well liked or even protected by LFD officials. Jones told a story that became legend on the LFD about Cliff Robertson, a white cowboy who came from a neighboring ranch as a “rep,” or representative. Ranches often sent reps who were seasoned cowboys to other ranches during round-ups to make sure that their stock was identified, properly branded, and returned to their home ranch. Add rode up to change his horse and said to Robertson, “What horse do you want, lint?” The term “lint” was a derisive one that referred to a young, inexperienced cowboy from East Texas with cotton lint still in his hair. Robertson tried to catch his own horse and threw a lasso and missed. Add then threw his rope and caught the horse and began to drag it out. Robertson, feeling insulted and embarrassed, came after Add with his rope doubled, or, as some cowboys said, with a knife to cut the rope. At this point Bud Wilkerson, the LFD’s range wagon boss, rode between them and said to Add, “Drag the horse out, and I will tend to the lint.” Robertson was so angered by the experience that he cut out his horses and went back to his home ranch.

Add, like many cowboys, traveled to other ranches where he could not depend on the protection and goodwill of the LFD. Jones related another story when Add was the LFD rep at the Hat ranch and breached the proper etiquette for a black cowboy. Add went to drink from a water bucket and, finding it empty, followed a standard cowboy procedure that he apparently used on the LFD without thought. He began to siphon water through a hose attached to a large water tank. To get the water started, Add used a method referred to as “sucking the gut.” As Add was in the process of starting the water, a white cowboy named Tom Ogles picked up a neck yoke and hit him on the back of the neck, knocking him out. When he regained consciousness, Add, who was reported to have knocked out a black man from a neighboring town with one punch and was described by everyone as stocky, short, and very powerfully built, did nothing. He waited for the remuda to arrive, got his horse, and rode home. This incident provided ample evidence that Add recognized the limitations that society had placed on him.

Add’s reputation as a roper also gained him respect and renown. He was able, according to some of his fellow cowboys, to go into a corral and rope any horse with uncanny accuracy. One roping story told by Whitlock attests to Add’s roping talents as well as his sense of cowboy humor. One day Add was sitting on his horse in front of the Grand Central Hotel in Roswell, New Mexico, when a runaway team of horses pulling a milk wagon came racing down the street. He made a big loop in his lariat, rode alongside the team, threw it around the horses’ heads, and allowed the slack to drape over the wagon. He then turned his horse off in a steer-roping style and caused the wagon, horses, and milk bottles to crash and scatter all over the street. After Add retrieved his rope, he was reported to have said, “Them hosses sure would’ve torn things up if I hadn’t caught them.”

Addison Jones was more fortunate than many black cowboys west of the Pecos in that he found someone locally to marry. It was not uncommon for black men in West Texas either to travel back to East Texas to find a wife or to remain single. In 1899 Add and Rosa Haskins were married by Rev. George W. Read. Add gave his age as fifty-four, while his bride was listed as thirty-six. Haskins, who was a cook and domestic for a number of prominent Roswell families, came to New Mexico from Texas sixteen years before she married Add. There is very little to indicate whether the couple enjoyed marital bliss, but according to Thorp, the announcement of the wedding to a few friends prompted ranchers throughout the Pecos valley to send wedding gifts to Old Add. The lack of a wedding registry and communications may have been the reason that Add and Rosa found nineteen cookstoves at the freight office in Roswell when they came to pick up their wedding presents.

Add’s life was lived and ended, according to former Texas and New Mexico sheriff Bob Beverly, the way an old cowboy’s life should be:

Add . . . realized his work was over. He had ridden the most dangerous trails and had conquered the wildest horses. He had always been thoroughly loyal to the Littlefields and the Whites. He was at the end of his road and he laid down and died knowing full well that his efforts had been recognized and appreciated by the really great cowmen of Texas and New Mexico.

(Bonney, 141)

Addison Jones died in Roswell and, according to Elvis Fleming, suffered a final double indignity of having his name misspelled and the improper birth data carved into his tombstone. The name on Add’s grave is Allison Jones, with a birth date of 24 March 1856, rather than 1845. Old Add lived an ordinary yet extraordinary life as a black cowboy in West Texas and New Mexico. He succeeded in living a life worth remembering, which was something few cowboys, black or white, were able to achieve.

Bonney, Cecil. Looking over My Shoulder: Seventy-five Years in the Pecos Valley (1971).

Brooks, Connie. The Last Cowboys: Closing the Open Range in Southeastern New Mexico, 1890s–1920s (1993).

Fleming, Elvis E. “Addison Jones, Famous Black Cowboy of the Old West” in Treasures of History III, Historical Society for Southeast New Mexico (1995): 34–46.

Haley, J. Evetts. George W. Littlefield, Texan (1943).

Whitlock, Vivian H. Cowboy Life on the Llano Estacado (1970).

—MICHAEL N. SEARLES

NIXON, EDGAR DANIEL

NIXON, EDGAR DANIEL(12 July 1899–25 Feb. 1987), Alabama civil rights leader, was born in Robinson Springs, Alabama, near Montgomery, the son of Wesley Nixon, a tenant farmer and, in later years, a Primitive Baptist preacher, and Susan Chappell. Nixon’s mother died when he was nine, and thereafter he was reared in Montgomery by a paternal aunt, Winnie Bates, a laundress. Nixon attained only an elementary education, and at thirteen began full-time work, first in a meat-packing plant, then on construction crews, and in 1918 as a baggage handler at the Montgomery railway station. As a result of friendships that he made in this last job, he managed in 1923 to become a Pullman car porter, a position he would hold until his retirement in 1964. In 1927 he was married to Alleas Curry, a schoolteacher. The couple soon separated, but they had Nixon’s only child. In 1934 he married Arlet Campbell.

Exposed by his railroad travels to the world beyond Montgomery, Nixon grew increasingly to hate racial segregation. He became a devoted follower of A. PHILIP RANDOLPH, who was attempting in the late 1920s and early 1930s to unionize the all-black Pullman porters. In 1938 Nixon was chosen as president of the new union’s Montgomery local. In 1943 he organized the Alabama Voters League to support a campaign to obtain voter registration for Montgomery’s blacks. The effort produced a vigorous white counterattack, but Nixon himself was registered in 1945.

Montgomery’s blacks were sharply divided between a middle-class professional community centered around the campus of Alabama State College for Negroes and the working-class blacks who lived on the city’s west side. The Montgomery branch of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP) was dominated by college-area professionals and failed to support Nixon’s voter registration drive actively. Nixon therefore began organizing the poorer blacks of west Montgomery, where he resided, to attempt a takeover of the branch. He was defeated for branch president in 1944 but was elected in 1945 and reelected in 1946 in bitterly contentious races. In 1947 he was elected president of the Alabama Conference of NAACP Branches, ousting the incumbent, Birmingham newspaper editor Emory O. Jackson. But national NAACP officials, who were hostile to his lack of education, quietly arranged for Nixon’s defeat for reelection to the state post in 1949. And in 1950 he also lost the presidency of the Montgomery branch to the same man he had beaten in 1945. Nevertheless, in 1952 he won election as president of the Montgomery chapter of the Progressive Democratic Association, an organization of Alabama’s black Democrats. And in 1954 he created consternation among Montgomery’s whites by becoming a candidate to represent his precinct on the county Democratic Executive Committee. Though he was unsuccessful, he thus became the first black to seek public office in the city in the twentieth century.

During his years with the NAACP, Nixon had become a friend of ROSA PARKS, the branch secretary during much of this period. When Parks was arrested on the afternoon of 1 December 1955 for violating Montgomery’s ordinance requiring racially segregated seating on buses, she called Nixon for help. After he bailed her out of jail, he began telephoning other black leaders to suggest a boycott of the buses on the day of Parks’s trial, 5 December, to demonstrate support for her. The proposal was one that black leaders had frequently discussed in the past, and it was greeted enthusiastically by many of them. The black Women’s Political Council circulated leaflets urging the action, and a meeting of black ministers gave it their approval. The boycott on 5 December was so complete that black leaders decided to continue it until the city and the bus company agreed to adopt the plan of seating segregation in use in Mobile, under which passengers already seated could not be unseated. The Montgomery Improvement Association was formed to run this extended boycott, and Nixon became its treasurer.

Nixon, however, became increasingly antagonistic toward the association’s president, the Reverend MARTIN LUTHER KING JR. Nixon viewed King as an ally of the Alabama State College professionals, and he believed that King’s growing fame was depriving him, and the poorer blacks whom he represented, of due credit for the boycott’s success. After King moved to Atlanta in 1960, Nixon engaged in a protracted struggle for leadership of Montgomery’s blacks with funeral director Rufus A. Lewis, the most prominent figure among his rivals in the middle-class Alabama State community. The contest culminated in the 1968 presidential election, when Nixon and Lewis served on alternative slates of electors, each of which was pledged to Hubert H. Humphrey. The Lewis slate defeated the Nixon slate handily in Montgomery. Nixon thereafter slipped into a deeply embittered obscurity. He accepted a job organizing recreational activities for young people in one of Montgomery’s poorest public housing projects, a position he held until just before his death in Montgomery.

The Library of Alabama State University, Montgomery, holds several scrapbooks of clippings and other material related to Nixon. Transcripts of oral history interviews with Nixon are held at Alabama State University; the Martin Luther King Center, Atlanta; and Howard University, Washington, D.C. See also the Montgomery NAACP Branch Correspondence, NAACP Papers, Library of Congress.

Baldwin, Lewis V., and Aprille V. Woodson. Freedom Is Never Free: A Biographical Portrait of Edgar Daniel Nixon, Sr. (1992).

Garrow, David J. Bearing the Cross: Martin Luther King Jr. and the Southern Christian Leadership Conference (1986).

Mills Thornton, J., III. Dividing Lines: Municipal Politics and the Struggle for Civil Rights in Montgomery, Birmingham, and Selma (2002).

Obituary: New York Times, 27 Feb. 1987.

—J. MILLS THORNTON

NORMAN, JESSYE

NORMAN, JESSYE(15 Sept. 1945–), opera singer, was born in Augusta, Georgia, to Silas Norman, an insurance salesman who also sang in the church choir, and Janie King, a secretary and accomplished amateur pianist. The Normans made certain that their five children studied piano and they encouraged Jessye to sing in church and community programs at a very early age. A 78 rpm recording of Brahms’s Alto Rhapsody, sung by MARIAN ANDERSON, was one of Norman’s most powerful inspirations. At age ten, she recounts, “I heard her voice and I listened. . . . And I wept, not knowing anything about what it meant” (Gurewitsch, 96).

After graduating with honors from Augusta’s Lucy Craft Laney High School in 1963, Norman went on to study voice with Carolyn Grant at Howard University in Washington, D.C. During the summer after her graduation in 1967, she attended the Peabody Conservatory in Baltimore, Maryland, after which she studied voice with Pierre Bernac and Elizabeth Mannion at the University of Michigan, receiving a Master of Music degree in 1968.

Norman’s professional career began overseas in 1968 after she won first prize in an International Music Competition sponsored by Bavarian Radio in Munich, Germany. The following year she signed a three-year contract with Deutsche Oper Berlin, and made her triumphant operatic debut on 12 December 1969 as Elisabeth in Richard Wagner’s Tannhauser—a demanding role for a twenty-four-year-old. In 1972 she made her professional American debut in Verdi’s Aida at the Hollywood Bowl in Los Angeles, with James Levine conducting. Throughout the 1970s Norman’s opulent voice and extraordinary intelligence continued to draw rave reviews and she was booked in concerts and festivals worldwide.

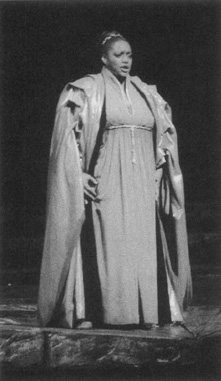

Jessye Norman, in dress rehearsal for her debut at the New York Metropolitan Opera in the role of Cassandra in Berlioz’s Les Troyens, 1983. © Bettmann/CORBIS

Norman’s debut with the Metropolitan Opera in New York City in September 1983 propelled her to new heights of popularity, especially with American audiences. The Met featured Norman as the tormented prophetess Cassandra, in Berlioz’s epic Les Troyens, a role she had sung in 1972 at Covent Garden in London. At subsequent performances, Norman changed roles from the dark-hued mezzo-soprano of Cassandra to the rich, searing soprano of Dido. Because of her gifts in character portrayal, she was able to interpret and delineate each role with authority and a profound sense of tragedy.

Norman’s other performances with the Met include twenty-two performances as the Prima Donna/Ariadne in Richard Strauss’s Ariadne auf Naxos and the Wagner roles of Elisabeth in Tannhäuser, Kundry in Parsifal, and Sieglinde in Die Walküre. Norman has lent her hypnotic, expressive, and robust voice to modern work as well. Critics called her richly dramatic interpretation of Schoenberg’s Erwartung a tour de force, and praised her performances in Bartok’s Bluebeard’s Castle, Poulenc’s Dialogues of the Carmelites, and Stravinsky’s Oedipus Rex.

Primary among Norman’s unique talents is her wide vocal range. She can move with grace and sensitivity from a sparkling high C-sharp to a voluptuous middle range to a rich low G. Her ability to draw expressive power and color from her roles has encouraged diversity within her repertoire as well. She maintains, “I don’t allow myself to be cast in a particular repertoire—or only in a particular repertoire—because I like to sing what I’m able to sing” (Gurewitsch, 99). Her curiosity has also drawn her to the less standard works, such as those of Monteverdi, Rameau, Purcell, Stravinsky, Schoenberg, and Philip Glass, which challenge her passions as well as her intellect. She opened Lyric Opera of Chicago’s 1990–1991 season in Robert Wilson’s innovative production of Gluck’s Alceste. To understand the intense emotions of Phèdre in Rameau’s opera, Hipployte et Aride, she read Racine. Norman strives to know her characters completely, visualizing the minutest details of every scene.

Performing under such distinguished conductors as Claudio Abbado, Riccardo Muti, Colin Davis, Daniel Barenboim, and Seiji Ozawa in orchestras around the world, Norman has honed a signature style and repertoire, which includes Isolde’s impassioned “Liebestod” from Wagner’s Tristan und Isolde, which she sang with the New York Philharmonic in 1989. Norman is also famous for her stunning interpretations of Mahler’s Das Lied von der Erde and Richard Strauss’s Four Last Songs, about which music critic Robert C. Marsh wrote, “If we must die, let us go with Jessye Norman singing” (Chicago Sun-Times, 21 Oct. 1986). In August 2002 she sang Alban Berg’s romantic Seven Early Songs with the Metropolitan Opera Orchestra in Baden Baden, Germany.

Recitals with piano, which allow her to explore the art song repertoire, as well as spirituals and popular music, have especially appealed to the singer. In any language she always knows the meaning behind every word, each of which is lovingly caressed through her singing. “Time and again she found just the right inflection or color to illuminate the text,” explains Derrick Henry (Atlanta Journal-Constitution, 11 Mar. 1989).

In 2000 Norman premiered Judith Wier’s song cycle, woman.life.song. Based on texts by TONI MORRISON, MAYA ANGELOU, and Clarissa Pinkola Estes, the work was commissioned for Norman by Carnegie Hall. Norman’s collaborations with other African American artists include performing the sacred music of DUKE ELLINGTON, and theatrical partnerships with the ALVIN AILEY Repertory Dance Ensemble, and the choreographer BILL T. JONES.

Jessye Norman’s brilliant career is reflected in the numerous awards and honors she has received. A prolific recording artist, Norman has recorded more than seventy albums her recordings—from Purcell and Beethoven to Cole Porter and jazz—number more than seventy, among them her 2003 recording of Mahler’s Kindertotenlieder commemorating the 150th anniversary of the Vienna Philharmonic. She is the recipient of four Grammy Awards, a Grand Prix National du Disque, a Gramophone Award, and an Edison Prize. A special favorite in France, she received the title Commandeur de l’Ordre des Arts et des Lettres in 1984 and the Legion d’Honneur from President Francois Mitterrand in 1989. She holds over thirty honorary doctoral degrees from universities, including Brandeis, Harvard, the University of Michigan, and Howard. In 1997 she became the youngest recipient of a Kennedy Center Honors award, and in 1999 President Clinton invited her to sing at the White House for the fiftieth anniversary celebration of the North Atlantic Treaty Organization.

In 1990 Jessye Norman was appointed an honorary U.N. ambassador. She has also served on the board of directors of numerous organizations, including the Lupus Foundation, the New York Public Library, the New York Botanical Garden, the Dance Theatre of Harlem, the National Music Foundation, and the Elton John AIDS foundation. The Amphitheater and Plaza overlooking the Savannah River in Norman’s hometown of Augusta have been named for her.

With all her glories, however, Norman has managed to retain her unpretentious demeanor. She has a quick wit and a smile that “hits the eyes like the sudden opening of Venetian blinds on a sunny day” (Current Biography Yearbook [1976], 295). A tall woman (five feet, ten inches) with a large, imposing frame, she had a ready answer to a friend who asked how she managed to get up after falling in Dido’s suicide scene. With a wink, she said, “I choreographed every muscle beforehand.” Norman is active in community affairs, especially in helping to promote historically black educational institutions. A dignified artist with elegance, poise, and grace, Jessye Norman has brought joy and wisdom to both her art and her audiences.

The Metropolitan Opera Archives, New York, contains press clippings, reviews, cast lists, and other production information relating to Norman’s career.

Gurewitsch, Matthew. “The Norman Conquests.” Connoisseur, Jan. 1987, 96–101.

Mayer, Martin. “Double Header.” Opera News, 18 Feb. 1984, 9–11.

Story, Rosalyn M. And So I Sing: African-American Divas of Opera and Concert (1990).

—ELISE K. KIRK

NORTHUP, SOLOMON

NORTHUP, SOLOMON(July 1808–1863?), author, was born in Minerva, New York, the son of Mintus Northup, a former slave from Rhode Island who had moved to New York with his master early in the 1800s and subsequently been manumitted. Though Solomon lived with both his parents and wrote fondly of both, he does not mention his mother’s name or provide any details regarding her background, except to comment that she was a quadroon. She died during Solomon’s captivity (1841–1853), whereas Mintus died on 22 November 1829, just as Solomon reached manhood. Mintus was manumitted upon the death of his master, and shortly thereafter he moved from Minerva to Granville in Washington County. There he and his wife raised Solomon and his brother Joseph, and for the rest of his life Mintus remained in that vicinity, working as an agricultural laborer in Sandy Hill and other villages. He acquired sufficient property to be registered as a voter—a notable accomplishment in those days for a former slave.

As a youth Solomon did farm labor alongside his father. Only a month after the death of Mintus, Solomon was married to Anne Hampton, and he soon began to do other kinds of work as well. He worked on repairing the Champlain Canal and was employed for several years as a raftsman on the waterways of upstate New York. During these years, 1830–1834, Anne and Solomon lived in Fort Edward and Kingsbury. In addition to his previous labors, Solomon began farming, and he also developed a substantial reputation as a fiddler, much in demand for dances. Anne, meanwhile, became well known as a cook in local taverns. They moved to Saratoga Springs in 1834, continuing in the same professions. They maintained their household there, which soon included three children, until 1841, when what had been a quite normal life took a dramatic turn for the worse.

In March of that year Solomon Northup met a pair of strangers in Saratoga who called themselves Merrill Brown and Abram Hamilton. Claiming to be members of a circus company, they persuaded him to accompany them for a series of performances until they rejoined their circus. As their terms seemed lucrative and Northup needed money, he agreed to join them as a fiddler. These con men, to secure Northup’s trust, told him that he should obtain free papers before leaving New York, since they would be entering the slave territories of Maryland and Washington, D.C. They further lulled him by paying him a large sum of money. In Washington, however, Northup was drugged, chained, robbed, and sold to a notorious slave trader named James H. Burch.

Thus began Northup’s twelve years as a slave. His narrative, Twelve Years a Slave: Narrative of Solomon Northup, far more than just a personal memoir, provides a detailed and fascinating portrait of the people, circumstances, and social practices he encountered. His account of the slave market, his fellow captives, and how they were all treated is especially vivid. Burch’s confederate, Theophilus Freeman, transported Northup and the others by ship to New Orleans, where they were sold in a slave market. Northup was purchased by William Ford, a planter in the Red River region, and though Ford was only his first of several masters, Northup spent his entire period of captivity in this section of Louisiana.

Despite the heinous injustice of Northup’s kidnapping and enslavement, he speaks quite favorably of the man who becomes his master: “In my opinion, there never was a more kind, noble, candid, Christian man than William Ford. The influences and associations that had always surrounded him, blinded him to the inherent wrong at the bottom of the system of Slavery” (Puttin’ on Old Massa, ed. Osofsky, 270). This passage, distinguishing between Ford’s personal character and environmental influences, reflects Northup’s extraordinary fair-mindedness, a trait that makes his text especially compelling and persuasive. Nonetheless, Northup’s respect for Ford did not reconcile him to accept his plight as a slave. Northup, called “Platt” while enslaved, made attempts as opportunities arose to escape and to notify his friends and family in New York of his situation. As his narrative shows, however, the constant surveillance and severe punishments of the slave system stifled such efforts. Even to obtain a few sheets of writing paper required waiting nine years. He feared to reveal his identity as a free man, lest he suffer extreme reprisals.

Northup’s skills as a rafter brought him distinction along the Red River, but financial difficulties forced Ford to sell him in the winter of 1842 to John M. Tibeats, a crude, brutal, and violent neighbor. The choleric Tibeats compulsively worked, whipped, and abused his slaves. Eventually he attacked Northup with an ax, and in self-defense Northup drubbed him mercilessly, then fled to the swamps. Luckily, by a legal technicality, Ford retained partial ownership of Northup, and when the fugitive arrived back on Ford’s plantation after several days of struggling through the swamps, Ford was able to shield him from Tibeats’s wrath. New arrangements were made, which contracted Northup out to work for Edwin Epps, an alcoholic plantation owner in Bayou Boef, who remained Northup’s master for the next decade. Northup’s skills as a carpenter, a sugarcane cutter, and especially as a fiddler kept his services in demand, making him perhaps the most famous slave in the region—but, ironically, known by the false name Platt.

Northup’s fortunes took a turn for the better in 1852 when a Canadian carpenter named Bass came to work on Epps’s new house. A genial but passionate man, Bass was regarded as an eccentric in the community because of his outspoken antislavery views. Hearing him debate Epps on the topic, Northup decided that Bass was a white man worth trusting. The two became friends, and Bass promised to mail a letter for Northup. At Northup’s direction, Bass composed a letter to William Perry and Cephas Parker of Saratoga, New York, informing them of Northup’s situation. When these men received the letter, they consulted Henry B. Northup, the son of Mintus Northup’s former master. He, in turn, initiated a complicated series of arrangements that led to his being appointed by the governor of New York as a special agent charged to secure the rescue of Solomon Northup from slavery in Louisiana. Fortunately New York had enacted in 1840 a law designed to address cases like Solomon’s, where New York citizens were kidnapped into slavery. The process, however, required obtaining proofs of citizenship and residence and various affidavits. Consequently it was the end of November before Henry Northup was empowered to act on behalf of the governor. Solomon, meanwhile, grew deeply depressed, having no way of knowing whether the letter had been delivered.

Nevertheless, Henry Northup acted with dispatch and arrived in Marksville on 1 January 1853 to seek out and liberate Solomon Northup. Unfortunately, though the local officials cooperated with his mission, no one knew a slave named Solomon Northup. A lucky inference by the local judge produced an encounter between Henry Northup and Bass, who revealed his authorship, the slave name, and the location of Solomon. Henry and the sheriff journeyed to the Epps plantation and laid claim to Solomon before the furious Epps could avoid a large financial loss by sending him away. After a brief formal proceeding, Solomon regained his freedom and returned northward with Henry.

They decided to stop in Washington and bring kidnapping charges against James Burch, which they filed on 17 January 1853. Due to various technicalities, Burch evaded conviction, but the case did serve the important purpose of bringing many facts into the public record, thereby confirming Solomon’s own account. He arrived in Sandy Hill, New York, on 20 January and proceeded to Glens Falls, where he was reunited with his wife and children, who had grown to adulthood in his absence. The narrative ends at this point, and little is known of Northup’s subsequent life, except that he contracted with David Wilson, a local lawyer and legislator, to write this memoir, which was published later in 1853. It sold quite well and resulted in the identification and arrest of Northup’s kidnappers, whose real names were Alexander Merrill and Joseph Russell. Their trial opened 4 October 1854 and dragged on for nearly two years, snarled by technicalities over jurisdiction, which finally received a ruling by the state supreme court that returned the case to the lower courts, who in turn simply dropped it. Northup never received legal recompense for the crimes committed against him. The sale of his book earned him three thousand dollars, which he used to purchase some property, and he returned to work as a carpenter. Nothing is known of his ensuing years. He apparently died in 1863, but scholars have not been able to confirm this. His narrative remains, however, one of the most detailed and realistic portraits of slave life.

Northup, Solomon. Twelve Years a Slave, Sue L. Eakins and Joseph Logsdon, eds. (1853; repr. 1968).

Blassingame, John. The Slave Community (1972).

Phillips, Ulrich Bonnell. American Negro Slavery (1918, 1966).

Stampp, Kenneth. The Peculiar Institution (1956).

—DAVID LIONEL SMITH

NORTON, ELEANOR HOLMES

NORTON, ELEANOR HOLMES(13 June 1937–), women’s and civil rights activist and congresswoman, was born Eleanor Katherine Holmes, the oldest of three daughters of Coleman Sterling Holmes, a public health and housing inspector, and Vela Lynch Holmes, a teacher, in segregated Washington, D.C. Oral history dates the family’s residence in Washington to the early 1850s, when her paternal great-grandfather walked off a Virginia plantation to freedom in the District of Columbia. Holmes’s father attended Syracuse University in upstate New York and worked his way through law school, though he never took the bar exam and never practiced law. Holmes’s mother, born on a family farm in North Carolina, completed normal school in New York, where she earned a teaching certificate. After she married and moved to Washington, she earned a bachelor’s degree from Howard University and passed the district’s teacher certification exam, becoming the financial stronghold of her family.

As a child, Holmes grew up admiring the educator and social activist MARY CHURCH TERRELL and was influenced deeply by her paternal grandmother, Nellie Holmes, who taught her “the assertiveness she was expected to show in public” (Steinham, 33). Her father reinforced the prospect of command and responsibility especially expected of the eldest daughter. Throughout her childhood her father taught Holmes to strive for the best and to insist on respect. At home and at school she consistently received messages advocating equality among the races. Holmes’s leadership began early in school and community activities. Quite popular among her age group, she was junior high school class president, leader of a community service club for teens, a debater, and a debutante during her senior year. She also excelled in her work from elementary through secondary school. In 1955, a year after the U.S. Supreme Court’s Brown v. Board of Education school desegregation decision, Holmes graduated as one of the top students from Washington’s prestigious Paul Laurence Dunbar High School in its last segregated class.

During the fall of 1955, as the civil rights movement was gathering momentum, Holmes entered Antioch College, in Ohio. Although she selected Antioch in large measure because of the work-study plan that would enable her to earn money for tuition, the very liberal atmosphere at the college shaped her emerging progressive political views. At Antioch, Holmes’s concern for racial justice matured and expanded to include broader questions of equality and social action. Ever a leader among her peers, Holmes eventually chaired both the campus Socialist Discussion Club and the campus NAACP chapter, the latter of which sent a “sizeable contribution” (Steinham, 65) to support the Montgomery bus boycott. In early 1960, during her last semester, when a wave of student-led sit-ins against segregated facilities spread across the South, Holmes organized similar protests in towns near the Antioch campus. She graduated from Antioch in June 1960, ranked twentieth among 165 graduates.

That fall, in a class with few women of any race and not many African Americans, she entered Yale Law School, along with MARIAN WRIGHT EDELMAN. In New Haven, Holmes continued her civil rights activism. She helped found and coordinate a chapter of the Congress on Racial Equality (CORE), and during the summer of 1963 she worked with the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC) in Mississippi. Her presence in Mississippi proved to be pivotal, since she was able to initiate crucial outside contact with FANNIE LOU HAMER, Lawrence Guyot, and several others who had been arrested and beaten and were being held in Winona, Mississippi. Guyot, also a SNCC worker, had received the same treatment as Hamer and others when he went to investigate their disappearance. Later that summer Holmes represented U.S. students on a European tour and worked at the New York headquarters of the March on Washington. In the fall she returned for her final year at Yale. She completed a four-year dual program in the spring, taking degrees in Law and American Studies and earning honors in the latter subject.

Having anticipated a career in civil rights law, Holmes headed for work with SNCC in Mississippi in 1964, immediately upon completion of her degree at Yale. That was the summer of the historic Mississippi Freedom Democratic Party (MFDP) challenge at the Democratic Party’s Atlantic City convention. Holmes was assigned to her hometown delegation, Washington, D.C., where she joined the civil rights and labor attorney Joseph L. Rauh Jr. in writing a brief arguing the MFDP’s case to the Democratic Party credentials committee. In Atlantic City, Holmes directed MFDP lobbying, including activities as varied as preparing and placing MFDP representatives to speak with credentials committee members and coordinating demonstrations outside the convention center. Yet despite the efforts of Rauh, Norton, BOB MOSES, and Fannie Lou Hamer, the MFDP failed to achieve its goal of supplanting the regular, whites only, Mississipi delegation at the convention with an integrated slate of delegates.

Continuing her preparation for civil rights work, she took a post in the fall as clerk for the newly appointed U.S. District Court judge, A. LEON HIGGINBOTHAM (a fellow graduate of Antioch), in Philadelphia. A year later, on 9 October 1965, Eleanor Holmes married Edward Norton, whom she had met four months earlier at the home of a longtime friend. The couple moved to Manhattan, where Edward Norton was finishing law school at Columbia University, and where Eleanor Holmes Norton took a position with the American Civil Liberties Union (ACLU). The Nortons, who separated after twenty-five years of marriage, had two children, Katherine and John.

At the ACLU, Norton’s reputation as a First Amendment expert emerged through the notoriety of her amicus curiae brief supporting JULIAN BOND’s efforts to be seated in the Georgia State legislature, and her successful defense of George Wallace, the segregationist governor of Alabama, and of the National States Rights Party, a white supremacy group. Norton also filed and won what was likely the first class action suit involving gender when she challenged Newsweek magazine’s practice of barring women from jobs as reporters. In 1970 Norton was named head of New York City’s Human Rights Commission, where she implemented new civil rights laws and pioneered antidiscrimination policies and programs. Her significant accomplishments at this time included diversifying the city’s definition of civil rights constituencies and conducting a complete review and reordering of the city’s public school staffing that made way for a more diverse workforce in school classrooms and administration. Within a year the Human Rights Commission post expanded to include a role as the mayor’s executive assistant. During this time Norton taught a course in women and the law at New York University Law School and coauthored the groundbreaking book Sex Discrimination and the Law: Causes and Remedies (1975). Norton continued to work as New York’s human rights commissioner for seven years until, in 1977, President Jimmy Carter appointed her the first woman to chair the Federal Equal Employment Opportunity Commission (EEOC).

When Norton took over as EEOC director, the agency had a massive backlog of complaints and a slow-moving bureaucracy. She engineered the agency’s reorganization, which resulted in streamlined and speedy claims processing and near complete handling of back-logged cases. She also led the EEOC’s broad-scale approach to employment discrimination by going after corporate and industrial “patterns and practices” instead of focusing solely on single cases. This resulted in closing prominent agreements with major corporations, including AT&T and the Ford Motor Company. Norton also initiated new EEOC procedures on fair employment and established pioneering guidelines to deal with the problem of sexual harassment in the workplace. Both of these initiatives continue to influence fair employment and sexual harassment policy today. In January 1981 Norton resigned the post as the administration of Ronald Reagan took office. One of Norton’s predecessors at the EEOC was CLARENCE THOMAS.

After a brief time recuperating from the grueling schedule of the EEOC, Norton took a post as professor at the Georgetown University Law Center. She taught constitutional law and cofounded the Women’s Law and Policy Fellowship Program. She also kept a busy speaking schedule, continuing to advocate civil rights improvements despite the country’s turn away from advances of the era. While a professor at Georgetown, Norton joined RANDALL ROBINSON, Walter Fauntroy, and Mary Frances Berry in a 1984 protest at the South African Embassy in Washington, D.C., that highlighted growing American opposition to the South Africa’s apartheid regime. In 1990 she was elected to the 102nd Congress, succeeding Walter Fauntroy as the district’s nonvoting representative. Taking office at a difficult time in D.C.’s history, Norton was successful in helping to restore credibility and resources to the beleaguered District of Columbia. She also attempted to make the issue of voting representation in Congress for District of Columbia residents a national civil rights issue.

Known as tenacious, sharp, and focused in all her work, Norton’s career of public service reflects her ongoing evolution as an advocate of equal rights for all Americans. Norton has received numerous honorary degrees and in 1982 was elected to the Yale University Corporation. She later was selected to serve on boards of several Fortune 500 corporations, including Pitney Bowes, Metropolitan Life Insurance, and Stanley Works.

Lester, Joan Steinau. Fire in My Soul (2003).

—ROSETTA E. ROSS