O’LEARY, HAZEL R.

O’LEARY, HAZEL R. O’LEARY, HAZEL R.

O’LEARY, HAZEL R.(17 May 1937–), U.S. secretary of energy, was born Hazel Reid in Newport News, Virginia, the youngest of two daughters of Dr. Russell E. Reid, and a mother about whom little is known, except that she was also a physician. Hazel and her sister, Edna, were raised in Newport News by their father and stepmother, Hazel Palleman Reid, in a loving and supportive environment that encouraged a solid education, independence, and compassion for others. Hazel’s grandmother, founder of Newport News’s only black public library, kept a box of clean and neatly packed clothes on her back porch for neighbors to take as needed.

Hazel’s life lessons began in the Reid household and continued with her elementary and middle school teachers at the segregated public schools in Newport News, where she was a star pupil. Although the Reid sisters led sheltered childhoods, their parents also encouraged their independence and intellect. Hazel was an exceedingly bright and competitive child with an abundance of self-confidence. Visionary when it came to their children’s futures, the Reids sacrificed both emotionally and financially to send their daughters “up north” to complete their education. From eighth grade through high school, Hazel and Edna lived under the care of an aunt, who resided in Essex County, New Jersey. Hazel studied voice and alto horn at the Arts High School for artistically talented youth and graduated with honors from that high school in 1956. She moved to Nashville, Tennessee, that year to attend Fisk University and received a BA degree cum laude from Fisk in 1959.

In 1960, just a year after graduating from Fisk, Hazel Reid married Dr. Carl Rollins. During her early years of marriage, she put her education on hold while she perfected her role as housewife. After the birth of a child, Carl G. Rollins, in 1963, however, she resumed her education, enrolling in Rutgers University School of Law. She graduated in 1966 with a JD degree. Over the next twenty-five years, Hazel Reid Rollins’s intellect, ambition, and self-confidence would serve her well, propelling her into increasingly prominent roles in state and federal government. In 1967 she was appointed assistant prosecutor in Essex County, New Jersey, and was subsequently appointed assistant attorney general in that state. Carl and Hazel Rollins’s marriage dissolved shortly before her next career move—to Washington, D.C. Upon moving there with her son, she joined the prominent accounting firm of Coopers and Lybrand as one of the first African American partners and one of a few female partners at that time.

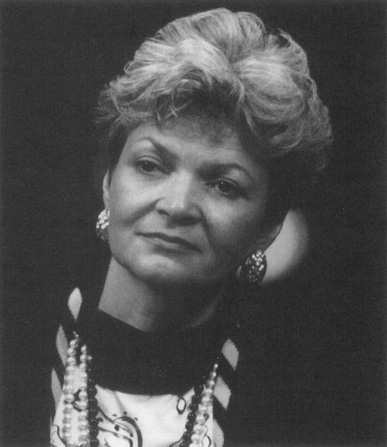

Hazel O’Leary, U. S. secretary of energy, was one of four African American cabinet members appointed by President Clinton in 1992. Corbis

In 1974 Hazel Rollins left the accounting firm and resumed her career in public service. Over the next twenty-five years she served under three presidents, Gerald Ford, Jimmy Carter, and Bill Clinton. In all three administrations her keen understanding of energy and energy conservation policy would be tapped. In 1974, during Ford’s tenure, Rollins joined the Federal Energy Administration (FEA) as director of the Office of Consumer Affairs/Special Impact—managing a number of the antipoverty programs initiated during the Great Society years of the 1960s. Despite Rollins’s appearance of privilege, she was known in some Washington circles as an advocate for the poor. In the Carter administration she served, from 1976 to 1977, as general counsel for the Community Services Administration; as assistant administrator for conservation and environment with the FEA; and, in 1978, as chief of the Department of Energy’s (DOE) Economic Regulatory Administration.

Rollins has been described as a lightning rod—attracting controversy wherever she happened to work and garnering either hot or cold reactions from friends and foes. As a regulator and an administrator, she has received both praise and criticism over the years. Described as a fair administrator, however, she gained respect even from environmentalists and energy executives, who lauded her conservation initiatives—including underwriting the cost of insulating homes for low-income families.

During her tenure with the Carter administration, Rollins met and worked with John F. O’Leary, deputy secretary for the DOE. Their friendship probably was ignited by a shared interest in and passion for the world of energy and conservation. In 1980 they married and, shortly thereafter, founded an international energy, economics, and strategic planning firm. Hazel O’Leary resigned her post at DOE to run the firm. John O’Leary passed away in 1987, leaving the responsibility of running O’Leary and Associates to his wife. In 1989 O’Leary closed the doors of the firm and, over the next three years, reestablished working relationships with other energy entities. These companies included Applied Energy Services, an independent power producer; NRG Energy, the major unregulated subsidiary of Northern States Power Company; and, later, its parent company, Minneapolis-based Northern States Power Company—an energy supplier to five contiguous states in the northern Midwest.

In November 1992 president-elect Bill Clinton made history when he appointed four African Americans to his cabinet. Hazel Rollins O’Leary was one of the earliest selections. Despite her past controversy among environmentalists, she was confirmed unanimously as secretary of energy just one day after Bill Clinton’s inauguration, and she was sworn into office in a White House ceremony one day later. O’Leary, only the seventh secretary of energy, was the first racial minority and first the woman to control one of the most unwieldy departments in the federal government. Early in her tenure O’Leary was dubbed one of the bright stars of the Clinton cabinet, bringing what one reporter described as a savvy respect for the consumer market, grassroots politics, and environmental concerns. Over time, however, it was these very attributes that would be used against her.

O’Leary viewed her mission at the department as that of shepherding the organization into the twenty-first century—and, to a large extent, she accomplished that mission. She boldly undertook initiatives that greatly influenced the lives of the American people and opened public debate within the DOE, the national laboratory system, and the national security community on nuclear weapons and their associated cleanup program and on nuclear testing. She is also credited with influencing President Clinton’s decision to end nuclear testing in the United States and with spearheading a more accessible DOE.

Yet it was her “outside the box” approach to government and her non-traditional leadership style that can be credited with her rocky tenure in the Clinton administration. Her last year was fraught with public and legal crises, including congressional criticism and investigations into her trade missions to foreign countries and her trip expense reports. In an exit interview with the New York Times in January 1997, an obviously weary O’Leary described her four years in office as “exhausting” and despaired that probably no secretary of energy taking office after her would undertake the important trade missions she had, given the scrutiny she had undergone.

DOE Secretary O’Leary submitted her resignation to President Clinton in December 1996. Upon leaving the Clinton administration in January 1997, she gravitated again to the private sector. She signed on as CEO for Blaylock & Partners LP, a New York-based full-service investment firm whose major client focus is on energy, transportation, telecommunications and technology, and consumer products. O’Leary’s role includes support of the firm’s expanding mergers and acquisitions interests, particularly in energy-related businesses.

Hazel O’Leary’s uncharacteristic courage and sense of fair play in a bureaucratic environment is part of her legacy. At the DOE she was a leader who took bold steps to reform an out-of-control bureaucracy and make government a place that worked for all people. In doing so, she raised the bar for those coming after her. As a business leader and world-renowned public figure, O’Leary remains a role model for young people, women, and minorities, who understand the difficulties of success against the odds. As she travels the world, this strikingly attractive and warm woman remains a sterling example of her parents’ teachings: reverence, honor, and a good education transcend any obstacle.

Healey, Jan. “Hazel R. O’Leary: A Profile.” Congressional Quarterly 177 (23 Jan. 1993).

Lippman, Thomas W. “An Energetic Net-worker to Take Over Energy,” Washington Post, 19 Jan. 1993.

Thompson, Garland L. “Four Black Cabinet Secretaries—Will It Make the Difference?,” Washington Times, 4 Feb. 1993.

Wald, Matthew. “Interview with Secretary Hazel O’Leary,” New York Times, 20 Jan. 1997.

—JANIS F. KEARNEY

OLIVER, KING

OLIVER, KING(11 May 1885–8 Apr. 1938), cornetist and bandleader, was born Joseph Oliver in or near New Orleans, Louisiana, the son of Jessie Jones, a cook; his father’s identity is unknown. After completing elementary school, Oliver probably had a variety of menial jobs, and he worked as a yardman for a well-to-do clothing merchant. He appears to have begun playing cornet relatively late, perhaps around 1905. For the next ten years he played in a variety of brass bands and large and small dance bands, coming to prominence about 1915. Between 1916 and 1918 Oliver was the cornetist of trombonist Edward “Kid” Ory’s orchestra, which was one of the most highly regarded African American dance orchestras in New Orleans. Early in 1919 Oliver moved to Chicago and soon became one of the most sought-after bandleaders in the cabarets of the South Side black entertainment district.

King Oliver (standing in center with cornet) led his Dixie Syncopators at the Plantation Café on Chicago’s South Side from 1925 to 1927. © Bettmann/CORBIS

In early 1921 Oliver accepted an engagement in a taxi-dance hall on Market Street in San Francisco, and he also played in Oakland with his old friend Ory and perhaps in local vaudeville as well. After a stop in Los Angeles, he returned to Chicago in June 1922, beginning a two-year engagement at the Lincoln Gardens. After a few weeks, Oliver sent to New Orleans for his young protégé LOUIS ARMSTRONG, who had been Oliver’s regular substitute in the Ory band some five years earlier. With two cornets (Oliver and Armstrong), trombonist Honore Dutrey, clarinetist Johnny Dodds, string bassist William Manuel Johnson, drummer Warren “Baby” Dodds, and pianist Lillian Hardin (LIL ARMSTRONG), King Oliver’s Creole Jazz Band made a series of recordings for the Gennett, OKeh, Columbia, and Paramount labels (some thirty-seven issued titles), which are regarded as supreme achievements of early recorded jazz. (Other musicians substitute for the regulars on a few of these recordings.) There is ample evidence that a great many musicians, black and white, made special and repeated efforts to hear the band perform live.

By early 1925 Oliver was leading a larger and more up-to-date orchestra with entirely new personnel. This group was the house band at the flashy Plantation Cafe (also on the South Side) and as the Dixie Syncopators made a series of successful recordings for the Vocalion label. Oliver took his band to the East Coast in May 1927, but after little more than a month, it dispersed. For the next four years Oliver lived in New York City, touring occasionally and making records for the Victor Company at the head of a variety of ad hoc orchestras; these are widely considered inferior to his earlier work.

His popularity waning and his playing suffering because of his chronic gum disease, Oliver spent an unpros-perous six years between 1931 and 1937 incessantly touring the Midwest and the Upper South. Savannah, Georgia, became his headquarters for the last year of his life; he stopped playing in September 1937 and supported himself subsequently by a variety of odd jobs. He died in Savannah of a cerebral hemorrhage; he was buried in Woodlawn Cemetery in New York City. The Reverend ADAM CLAYTON POWELL officiated, and Louis Armstrong performed at the funeral service. He was survived by his wife, Stella (maiden name unknown), and two daughters.

Oliver is the most widely and favorably recorded of the earliest generation of New Orleans ragtime/jazz cornetists, most influential perhaps in his use of straight and plunger mutes; aspects of Louis Armstrong’s style clearly derive from Oliver. Oliver’s best-known contributions as a soloist are his three choruses on “Dipper Mouth Blues,” copied hundreds of times by a wide variety of instrumentalists on recordings made during the next twenty years. His major achievement, however, remains the highly expressive and rhythmically driving style of his band as recorded in 1923–1924. While the band owed its distinctiveness and energy, like all early New Orleans jazz, to the idiosyncratic musical talents of the individual musicians, its greatness was undoubtedly the result of Oliver’s painstaking rehearsals and tonal concept.

Gushee, Lawrence. “Oliver, ‘King’” in New Grove Dictionary of Jazz, ed. Barry Kern-feld (1988).

Wright, Laurie. “King” Oliver (1987).

Obituary: Chicago Defender, 16 Apr. 1938.

—LAWRENCE GUSHEE

O’NEAL, FREDERICK DOUGLASS

O’NEAL, FREDERICK DOUGLASS(27 Aug. 1905–25 Aug. 1992), actor, activist, arts leader, and union organizer, was born in Brooksville, Mississippi, to Minnie Bell Thompson, a former teacher, and Ransome James O’Neal Jr., a teacher who later joined the family business, RJ O’Neal and Son, a general store started by his father, Ransome Sr. Named after the famed abolitionist FREDERICK DOUGLASS, O’Neal was the sixth of eight children. He developed an interest in the theater at an early age and at age eight gave a recitation in grade school that proved to be a formative moment in his decision to pursue acting as a career. His father constructed a little hall next to the family store, where Frederick, at age ten and eleven, put on small shows. After his father died unexpectedly when Frederick was fourteen, his mother sold the store and moved her family to St. Louis, Missouri, in 1920. Frederick, who had attended public school in Brooksville, finished elementary school at Waring School in St. Louis. In 1922 he entered Sumner High School. Soon after, he began work as a file clerk at the Meyer Brothers Drug Company, a job that necessitated his move to night school. Frederick also worked the graveyard shift as a post office clerk, further interfering with his desire to become an actor.

During the 1920s and 1930s O’Neal grew even more determined to become an actor. He joined the St. Louis branch of the Urban League in 1920 in order to perform in their annual plays, which included the 1926 production of Shakespeare’s As You Like It, in which he starred. In 1927, with assistance from the Urban League’s director, John Clark, and the entrepreneur ANNIE TURNBO MALONE, O’Neal founded the St. Louis Aldridge Players. Named after the actor IRA ALDRIDGE (and later renamed the Negro Little Theatre of St. Louis), the troupe produced three plays per year and remained in operation until 1940. Dedicated to community service and to the encouragement of black playwrights, the Aldridge Players performed at the St. Louis YMCA, at local high schools, and at Annie Turnbo Malone’s Poro Beauty College.

In 1936, on the advice of ZORA NEALE HURSTON, O’Neal left St. Louis for New York to further his acting career. With his previous experience at Meyer Drug Store, he landed a day job working as a laboratory assistant. At night he studied voice, movement, and acting at the New Theatre School and the American Theatre Wing. He also received a scholarship for private lessons. This training provided a solid foundation for his future work in theater and film. And while he had hoped to work with the New York Negro Unit of the Federal Theatre Project before it was disbanded in 1939, he joined the Rose McClendon Players in 1938, remaining with the company until it folded a year later.

Following the dissolution of the Rose McClendon Players, O’Neal and the playwright Abram Hill founded the American Negro Theater (ANT) to provide opportunities for black theater artists, writers, and designers. O’Neal served as company manager. Modeled after its insect namesake, the “ant,” the American Negro Theatre proclaimed itself to be a communal effort eschewing the conventional star system in favor of working diligently and collectively for the good of the whole. ANT’s first production, On Strivers Row, a satire of the black middle class written by Hill, ran for five months on weekends in the basement theater of the Harlem branch of the public library. Row was followed by the folk opera Natural Man, a play by Theodore Browne that featured O’Neal in the role of the preacher. In 1944 ANT mounted its most successful production, an adaptation of Yordan’s play about a Polish working-class family in a Pennsylvania industrial town, Anna Lucasta. The play, co-starring O’Neal as Frank, garnered critical acclaim and soon moved to Broadway, where it ran for 956 performances and won O’Neal both the Clarence Der-went Award and the New York Critics Award.

While working with the ANT in 1941, O’Neal met Charlotte Talbot Hainey at a YMCA dance. The couple married on 18 April 1942; they had no children. In October, O’Neal was drafted into the army and stationed at Fort Dix, New Jersey, after which he was transferred to Fort Huachuca, Arizona, where he served until his honorable discharge in 1943. Free from the service, O’Neal returned to his wife and to his career in the theater in New York City.

From the 1940s through the 1960s O’Neal enjoyed a successful movie and stage career. His first film appearance was in the 1949 feature Pinky, the Elia Kazan drama about passing, starring Jeanne Crain, ETHEL WATERS, and Ethel Barrymore. O’Neal was cast in a number of lesser film productions, playing a variety of “jungle roles,” including King Burlam in Tarzan’s Peril (1951), a Mau-Mau leader in Something of Value (1957), and Buderga in The Sins of Rachel Cade (1961). On Broadway, O’Neal costarred as Lem Scott in the 1953 play Take a Giant Step. Six years later he recreated the role in the film version, which starred RUBY DEE and the singer Johnny Nash. O’Neal also reprieved the role of Frank in the 1958 film version of Anna Lucasta co-starring EARTHA KITT and SAMMY DAVIS JR. In 1959 he portrayed Moses in the Hall of Fame production of The Green Pastures. In the theater, he appeared in The Winner in 1954, as Houngan in House of Flowers in 1954, and as the preacher in God’s Trombone in 1960.

As O’Neal furthered his leadership and activism in the arts, he also performed on television. He was a regular on the television sitcom Car 54, Where Are You? in the 1960s. He played in Jack Smight’s Strategy of Terror (1959); Free, White and 21 (1963); and OSSIE DAVIS’s Cotton Comes to Harlem (1970).

At the same time as he found success in his own career, O’Neal fought passionately for the rights of all black actors. Recognizing the unequal treatment of black performers, O’Neal in the 1950s published articles in Crisis and Equity News, the newsletter of the professional actors’ union, Actor’s Equity Association (AEA), calling for producers to cast black actors in roles that were not racially specific. He also gave speeches on the need for “nontraditional casting” before groups such as the Catholic Interracial Council. The council, along with the NAACP, organized protests in 1953 against racial representation on network television. As a result of his activism, O’Neal found himself blacklisted by several television networks. This experience led him to become increasingly active in the struggle for the rights of actors and ultimately resulted in his being elected as the first black president of AEA in 1964.

O’Neal’s service as president of AEA marked a continuation of his institutional agitation for the equal treatment of black actors. In 1944, as chair of AEA’s Hotel Accommodations Committee, he had worked to change the discriminatory housing practices faced by black traveling performers. In 1961, at time when he also functioned as first vice president of the AEA, O’Neal had served as president of the Negro Actors Guild, a branch of AEA dedicated to advocating for the rights of black performers. As AEA president from 1964 through 1973, O’Neal forthrightly advanced the concerns of minority actors. He also lobbied for the establishment of the National Foundation for the Arts and Humanities, which was signed into law by President Lyndon B. Johnson in September 1965. One of the final acts of O’Neal’s terms as president was the establishment of the AEA Paul Robeson Citation Award. PAUL ROBESON himself was the first recipient in 1974. That same year, O’Neal assumed the presidency of Associate Actors and Artists of America, the international governing union of actors, and he held this post for eighteen years.

Later in life O’Neal received many accolades. He won the Negro Trade Union Leadership Council Humanitarian Award in 1974, the Frederick Douglass Award in 1975, and the NAACP Man of the Year Award in 1979. The AEA presented him with the 1985 Paul Robeson Citation Award, the award he had helped found. In 1990 he received the Black Filmmakers Hall of Fame Award and was also named an American Theatre Fellow by the John F. Kennedy Center. After a prolonged battle with cancer, he died in his Manhattan home, only four months after he and his wife had celebrated their fiftieth wedding anniversary and two days before his eighty-sixth birthday. On 15 September 1992 friends and family gathered at the Schubert Theater in New York City for a final tribute to Fredrick Douglass O’Neal, a pioneer and leader in the American theater.

“Actors’ New Boss: Frederick O’Neal Heads Actors’ Equity Assn,” Ebony 19 (June 1964).

Simmons, Renee. Frederick Douglass O’Neal: Pioneer of the Actor’s Equity Association (1996).

Obituary: Jet, 14 Sept. 1992.

—HARRY ELAM

O’NEAL, STANLEY

O’NEAL, STANLEY(7 Oct. 1951–), corporate executive, was born Earnest Stanley O’Neal in Roanoke, Alabama, the oldest of four children of Earnest O’Neal, a farmer, and Ann Scales, a domestic. The family lived in a small farming town called Wedowee, but because its hospital would not admit African Americans, he was born in the neighboring town of Roanoke. The grandson of a former slave, O’Neal lived with his family in poverty. Although his house had no indoor plumbing, it was inhabited by a loving extended family of aunts, uncles, and cousins. With a population less than eight hundred, Wedowee offered scarce resources. O’Neal was educated in a one-room schoolhouse heated with a wooden stove and with one teacher to instruct all the grades. Outside the classroom, he and his siblings spent hours picking cotton on their grandfather’s fields. Very early on, O’Neal’s father told him that he was not the farming type and advised him to explore other options for his future.

These options increased when the family moved to Atlanta, Georgia, in the 1960s. When they arrived, the O’Neals moved into a federal housing project, which Stanley welcomed because “it was ‘ten stories higher’ than anything he had ever known” (Fortune, 28 Apr. 1997). O’Neal attended West Fulton High School, where he was one of the first black students. In addition to his schoolwork, he took on various odd jobs to help his family. His father got a job on the General Motors (GM) assembly line in Doraville, Georgia, just as the factory was being integrated. After high school graduation, O’Neal reached a turning point in his life when GM offered him the chance to study at the General Motors Institute (now Kettering University). He studied in six-week stints, alternating between work in a factory and his education in the classroom. He graduated with a BS in Industrial Administration in 1974, the first in his family to graduate from college. He was ranked in the top 20 percent of his class and accepted an offer to become a supervisor at the very factory where his father worked. After some time working there, GM gave him a scholarship to study at Harvard Business School. He graduated in 1978 and set off for New York City to work in one of the most dynamic business environments in the world.

Awaiting him in New York City was a job as an analyst for GM. O’Neal moved up the corporate ladder quickly, his rise fueled by his strong command of numbers and a work ethic that had him sitting in his office till 10:00 PM on a regular basis. After two years he became a director, and in 1982 he moved to Spain to become treasurer of the company’s Spanish division. In 1984 he returned to New York as GM’s assistant treasurer. In the treasury office he worked with his future wife, Nancy Garvey, an economist. The two married in 1983 and had twins, a son and a daughter.

Another turning point in O’Neal’s life came in 1986, when he decided that he was ready for new challenges and a new industry. Having clearly demonstrated that he understood the language of numbers at GM, he decided to go to Wall Street to join the financial services firm Merrill Lynch. O’Neal first made a name for himself in the company’s corporate finance division, a lucrative area that he understood, because he had had to deal with many investment bankers at GM. Within five years he was chosen to head Merrill Lynch’s high-yield department.

O’Neal came to this position at a time when high-yield bonds, more commonly known as “junk bonds,” were distrusted because of a scandal involving Drexel Burnham Lambert, another Wall Street firm. Despite the tough market, Merrill Lynch rose to the top of this field, acting as lead manager of deals worth $3.9 billion dollars. For the rest of O’Neal’s tenure as head of the group, the firm remained at or near the top of the industry, resulting in O’Neal’s selection as head of Merrill’s entire capital markets division in 1996. After he left, the high-yield department dropped to eighth place in industry rankings.

In 1998 O’Neal moved to the top management level at Merrill Lynch when he was named chief financial officer, his first administrative job. This signaled to Wall Street insiders that he was in the running to be the firm’s chief executive officer. It provided another chance for O’Neal to prove his leadership qualities, because in the fall of that year a Russian financial crisis and the collapse of a powerful hedge fund named Long Term Capital Management sent the bond markets into a free fall. Merrill Lynch found itself stuck with bonds dropping in value, and O’Neal took charge of navigating the firm through the tough time.

From there, O’Neal’s ascent was meteoric. In February 2000 he was named the head of the firm’s private client group, a significant position, because Merrill Lynch has the largest brokerage on Wall Street. He was the first person to run the fifteen thousand brokers who himself had never been a broker. In the summer of 2001 O’Neal was named president and chief operating officer, and in December 2002 he took over as chief executive officer. He was the first African American to head a major firm on Wall Street.

As O’Neal stepped into his new historic position, he also inherited a number of challenges. One problem came from the moribund economic climate that had emerged after the boom years of the 1990s. Fewer companies were going public, stock prices had declined dramatically, and the drop in activity had shrunk profits on Wall Street. In addition to these inauspicious market conditions, Merrill Lynch was trying to escape scandal. Months before O’Neal took over as CEO, the firm agreed to a $100-million-dollar fine to settle a probe issued by the New York State’s attorney general’s office that charged Merrill research analysts with issuing false praise of corporations to win investment-banking business.

Now that O’Neal has taken the helm, it is his primary responsibility to steer the firm out of the haze of these problems. So far, he has attacked these problems by drastically cutting costs and putting a greater emphasis on the most profitable areas of Merrill’s business. His vision is to “build a ‘new kind of financial-services firm’ that redefines Wall Street by offering a far greater range of services” (Business Week, 5 May 2003). O’Neal may well be the right person to do it. He is often described as cool and calm, and his track record has shown an ability to help get his team out of complicated financial situations.

O’Neal has a unique background among major Wall Street executives. His rapid rise drew such great attention that in 2002 Fortune named him the “Most Powerful Black Executive in America.” Although he is quick to emphasize his work and talents, O’Neal also knows that he is a symbol. He once said, “Somebody has to be first, so it may as well be me. One of the things that has become clear to me as I have got more publicity is, like it or not, I am a role model. That’s an aspect of who I am and I embrace it” (Financial Times, 25 July 2001).

Bell, Gregory S. In the Black: A History of African Americans on Wall Street (2001).

Clarke, Robin D. “Running with the Bulls,” Black Enterprise, Sept. 2000.

Thornton, Emily. “The New Merrill Lynch,” Business Week, 5 May 2003.

—GREGORY S. BELL

ONESIMUS

ONESIMUS(fl. 1706–1717), slave and medical pioneer, was born in the late seventeenth century, probably in Africa, although the precise date and place of his birth are unknown. He first appears in the historical record in the diary of Cotton Mather, a prominent New England theologian and minister of Boston’s Old North Church. Reverend Mather notes in a diary entry for 13 December 1706 that members of his congregation purchased for him “a very likely Slave; a young Man who is a Negro of a promising aspect of temper” (Mather, vol. 1, 579). Mather named him Onesimus, after a biblical slave who escaped from his master, an early Christian named Philemon.

This Onesimus fled from his home in Colossae (in present-day Turkey) to the apostle Paul, who was imprisoned in nearby Ephesus. Paul converted Onesimus to Christianity and sent him back to Philemon with a letter, which appears in the New Testament as Paul’s Epistle to Philemon. In that letter Paul asks Philemon to accept Onesimus “not now as a servant, but above a servant, a brother beloved” (Philemon 1.16 [AV]). Mather similarly hoped to make his new slave “a Servant of Christ,” and in a tract, The Negro Christianized (1706), encouraged other slaveowners to do likewise, believing that Christianity “wonderfully Dulcifies, and Mollifies, and moderates the Circumstances” of bondage (Silverman, 264).

Onesimus was one of about a thousand persons of African descent living in the Massachusetts colony in the early 1700s, one-third of them in Boston. Many were indentured servants with rights comparable to those of white servants, though an increasing number of blacks—and blacks only—were classified as chattel and bound as slaves for life. Moreover, after 1700, white fears of burglary and insurrection by blacks and Indians prompted the Massachusetts assembly to impose tighter restrictions on the movements of people of color, whether slave, servant, or free. Cotton Mather was similarly concerned in 1711 about keeping a “strict Eye” on Onesimus, “especially with regard unto his Company,” and he also hoped that his slave would repent for “some Actions of a thievish aspect” (Mather, vol. 2, 139). Mather believed, moreover, that he could improve Onesimus’s behavior by employing the “Principles of Reason, agreeably offered unto him” and by teaching him to read, write, and learn the Christian catechism (Mather, vol. 2, 222).

What Onesimus thought of Mather’s opinions the historical record does not say, nor do we know much about his family life other than that he was married and had a son, Onesimulus, who died in 1714. Two years later Onesimus gave the clearest indication of his attitude toward his bondage by attempting to purchase his release from Mather. To do so, he gave his master money toward the purchase of another black youth, Obadiah, to serve in his place. Mather probably welcomed the suggestion, since he reports in his diary for 31 August 1716 that Onesimus “proves wicked, and grows useless, Froward [ungovernable] and Immorigerous [rebellious].” Around that time Mather signed a document releasing Onesimus from his service “that he may Enjoy and Employ his whole Time for his own purposes and as he pleases” (Mather, vol. 2, 363). However, the document makes clear that Onesimus’s freedom was conditional on performing chores for the Mather family when needed, including shoveling snow, piling firewood, fetching water, and carrying corn to the mill. This contingent freedom was also dependent upon his returning a sum of five pounds allegedly stolen from Mather.

Little is known of Onesimus after he purchased his freedom, but in 1721 Cotton Mather used information he had learned five years earlier from his former slave to combat a devastating smallpox epidemic that was then sweeping Boston. In a 1716 letter to the Royal Society of London, Mather proposed “ye Method of Inoculation” as the best means of curing smallpox and noted that he had learned of this process from “my Negro-Man Onesimus, who is a pretty Intelligent Fellow” (Winslow, 33). Onesimus explained that he had

undergone an Operation, which had given him something of ye Small-Pox, and would forever preserve him from it, adding, That it was often used among [Africans] and whoever had ye Courage to use it, was forever free from the Fear of ye Contagion. He described ye Operation to me, and showed me in his Arm ye Scar.

(Winslow, 33)

Reports of similar practices in Turkey further persuaded Mather to mount a public inoculation campaign. Most white doctors rejected this process of deliberately infecting a person with smallpox—now called variolation—in part because of their misgivings about African medical knowledge. Public and medical opinion in Boston was strongly against both Mather and Dr. Zabdiel Boylston, the only doctor in town willing to perform inoculations; one opponent even threw a grenade into Mather’s home. A survey of the nearly six thousand people who contracted smallpox between 1721 and 1723 found, however, that Onesimus, Mather, and Boylston had been right. Only 2 percent of the six hundred Bostonians inoculated against smallpox died, while 14 percent of those who caught the disease but were not inoculated succumbed to the illness.

It is unclear when or how Onesimus died, but his legacy is unambiguous. His knowledge of variolation gives the lie to one justification for enslaving Africans, namely, white Europeans’ alleged superiority in medicine, science, and technology. This bias made the smallpox epidemic of 1721 more deadly than it need have been. Bostonians and other Americans nonetheless adopted the African practice of inoculation in future smallpox outbreaks, and variolation remained the most effective means of treating the disease until the development of vaccination by Edward Jenner in 1796.

Herbert, Eugenia W. “Smallpox Inoculation in Africa.” Journal of African History 16 (1975).

Mather, Cotton. Diary (1912).

Silverman, Kenneth. The Life and Times of Cotton Mather (1984).

Winslow, Ola. A Destroying Angel: The Conquest of Smallpox in Colonial Boston (1974).

—STEVEN J. NIVEN

OTABENGA

OTABENGA(1883?-20 Mar. 1916), elephant hunter, Bronx Zoo exhibit, and tobacco worker, was born in the rain forest near the Kasai River in what is now the Democratic Republic of Congo. The historical record is mute on the precise name of his tribe, but they were a band of forest-dwelling pygmies—averaging less than fifty-nine inches in height—who had a reciprocal relationship with villagers of the Congolese Luba tribe. Otabenga and his fellow pygmies hunted elephants by playing a long horn known as a molimo to replicate the sound of an elephant bleat. Once they had roused the animal from the forest, they killed it with poisoned spears and traded the elephant hide and flesh to the Luba villagers in exchange for fruits, vegetables, and grains. Very little is known about Otabenga’s family life, other than that he was married with two children by the age of twenty.

Around that time, while Otabenga was on an elephant hunt, his wife, children, and fellow members of his band were killed by Congolese agents of the Belgian colonial Force Publique, who had raided their community in search of ivory. When he returned, the Force Publique whipped him and forced him to march for several days, leaving him as a slave in a village inhabited by the warlike Baschilele. It was there, in March 1904, that the Reverend Samuel Phillips Verner, a white South Carolinian missionary, anthropologist, and pursuer of get-rich-quick schemes, secured Otabenga’s release from the Baschilele for the sum of a pound of salt and a bolt of cloth.

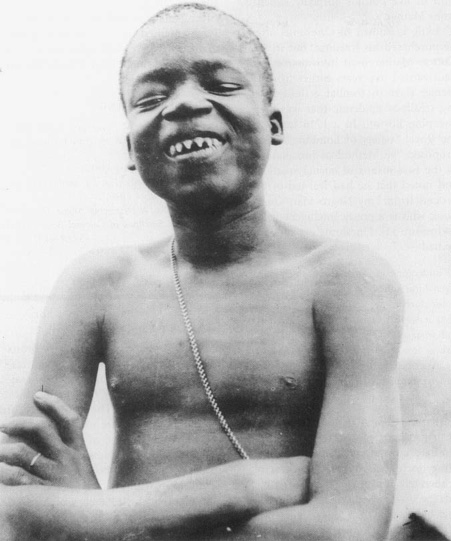

Otabenga displayed his filed teeth for nickels and dimes at the 1904 St. Louis World’s Fair. American Museum of Natural History

Verner had first traveled to the Congo in the 1890s, and his stay with the missionary WILLIAM H. SHEPPARD enabled him to learn the topography and many languages of the Congo. In 1904 he returned to find pygmies for an exhibit of native peoples to be held at the St. Louis World’s Fair. In doing so, Verner and the fair organizers were guided by the scientific racism that pervaded American and European thought at that time. Eminent scholars at Harvard and other leading colleges believed that a racial hierarchy existed among the different peoples of the world and that northern European humans represented the highest stage of evolutionary development. Display and rigorous scientific study of allegedly “primitive” groups like the Congolese pygmies and North American Apaches, the fair’s organizers believed, would educate the eighteen million visitors to St. Louis about the evolutionary process.

Few of the fair’s visitors were interested in such science—or pseudoscience. Most gawked at Otabenga and the Batwa pygmies whom Verner had also found in the Congo. Others took intrusive photographs and, on occasion, poked and prodded them. One newspaper described him as a “dwarfy black specimen of sad-eyed humanity” (Bradford and Blume, 256). The inhumanity of his hosts, on the other hand, was little commented upon. Press reports did, however, note the public’s fascination with Otabenga’s teeth, which he had filed into sharp triangles, a practice erroneously cited as evidence of his cannibalism. Displaying a keener understanding of his hosts’ values and culture than those hosts showed for his own, Otabenga charged fairgoers a fee of a nickel or a dime before he would display his two rows of sharpened incisors.

When the fair ended in December 1905, Verner returned with the pygmies to Africa. There Otabenga married his second wife, a Batwa woman who died from a snakebite soon afterward. The Batwa blamed Otabenga for her death and shunned him. That decision appears to have strengthened his relationship with Verner, also an outsider, who had remained in the Congo to collect artifacts and native animals for sale to American museums and zoos. To that end, the two traveled throughout the Congo for several months, and, according to a biography of Otabenga drawn chiefly from Verner’s reminiscences, their relationship evolved into one of great mutual regard. In August 1906 they returned to America, where Verner left Otabenga in the care of the Museum of Natural History in New York City and then in the hands of William Hornaday, president of the Bronx Zoological Gardens.

Otabenga initially had free rein to wander the zoo, occasionally assisting the keepers and observing both animals and New Yorkers at close quarters. Hornaday then encouraged Otabenga to sleep in the monkey house and placed a sign on his cage informing spectators that it contained “The African Pygmy” and listing his name, age, height, and weight. Otabenga’s biographers write that, inspired by a combination of “Bar-numism, Darwinism, and racism,” Hornaday scattered bones around the cage to highlight the pygmy’s alleged savagery and introduced into his enclosure an orangutan. Otabenga would play with the orangutan to the fascination of the thousands of spectators who flocked to the zoo. The spectacle prompted a flurry of articles in the New York Times, but only a few criticized the pygmy’s treatment. The Reverend James Gordon, the head of an African American orphanage, did, however, protest Hornaday’s presumption that Africans provided an evolutionary “missing link” to apes. Gordon did this mainly out of respect for Otabenga’s humanity but also because he opposed Darwinism. Hornaday ignored such protests, but he did respond when Otabenga brandished a knife at a zookeeper who had provoked and forcibly restrained him. With Verner’s permission, and with Otabenga’s own seeming approval, the African was then placed in Reverend Gordon’s care.

Thereafter the press and the public showed little interest in Otabenga, though his later years serve in some ways as a rebuke to those who had placed him in a cage and doubted his humanity. He learned to read and write at the orphanage and later studied for a semester at a Baptist school in Lynchburg, Virginia, where he converted to Christianity. After working for several years as a farm laborer on property owned by the Reverend Gordon on Long Island, New York, Otabenga returned to Lynchburg. He found the climate of the Blue Ridge foothills more amenable than New York’s and also better for hunting, although wild turkey had replaced elephants as his game. Much to his delight, he discovered marijuana plants in the woods near Lynchburg, enabling him to smoke the seeds that he had known as bangi in his homeland. Although he was able, like most immigrants, to replicate some aspects of his native culture, Otabenga also adapted to American ways. He changed his name to Otto Bingo, wore overalls like those of his fellow tobacco factory workers during the week, and at week’s end put on his Sunday best, in the manner of his fellow Baptists. He even capped his sharpened teeth. As a friend of the noted Lynchburg poet Anne Spencer, Otabenga also met African American leaders, including W. E. B. DU BOIS and BOOKER T. WASHINGTON.

Such a life of relative normality may have failed to compensate for the personal tragedies Otabenga endured: the death of two wives and two children, the slaughter of his band of pygmies, his capture and near execution by the Force Publique, his exile in the United States, and his humiliations in St. Louis and the Bronx. Such explanations offer clues, but, of course, they can never fully explain the reasons for his suicide on 20 March 1916.

Otabenga lived in the era described by the historian RAYFORD W. LOGAN as the nadir of American race relations. During the thirty or so years of Otabenga’s life, four thousand Americans were lynched, the vast majority of them black southerners. Hundreds of black Americans also died in white-instigated race riots in those years—in Wilmington, North Carolina, in 1898; in New Orleans in 1900; and in Atlanta, Georgia, and Bronzeville, Texas, both in 1906. In addition to this wave of physical violence, southern Democrats led white supremacy campaigns in those same decades that systematically disfranchised black voters and institutionalized the concept of separate and unequal facilities. The federal government either ignored or, as in the case of Plessy v. Ferguson (1896), endorsed these efforts to erode the Constitution’s promise of equal protection under the law. That historical context suggests, tragically, that Otabenga’s life story is much less extraordinary, and perhaps much more representative, than at first appears.

Bradford, Phillips Verner, and Harvey Blume. Ota Benga: The Pygmy in the Zoo (1992).

Kennedy, Pagan. Black Livingstone: A True Tale of Adventure in the Nineteenth-Century Congo (2002).

TurnbuII, Colin. The Forest People (1961).

—STEVEN J. NIVEN

OWENS, JESSE

OWENS, JESSE(12 Sept. 1913–31 Mar. 1980), Olympic track champion, was born James Cleveland Owens in Oakville, Alabama, the son of Henry Owens and Mary Emma Fitzgerald, sharecroppers. Around 1920 the family moved to Cleveland, Ohio, where the nickname “Jesse” originated when a schoolteacher mispronounced his drawled “J. C.” A junior high school teacher of physical education, Charles Riley, trained Owens in manners as well as athletics, preparing him to set several interscholastic track records in high school. In 1932 the eighteen-year-old Owens narrowly missed winning a place on the U.S. Olympic team. Enrolling in 1933 at Ohio State University, Owens soared to national prominence under the tutelage of coach Larry Snyder. As a sophomore at the Big Ten championships, held on the Ann Arbor campus of the University of Michigan, on 25 May 1935 he broke world records in the 220-yard sprint, the 220-yard hurdles, and the long jump, and equaled the world record in the 100-yard dash.

Scarcely did the success come easily. As one of a handful of black college students at white institutions in the 1930s, Owens suffered slurs on campus, in the town of Columbus, and on the athletic circuit. Personal problems also intruded. Just over a month after his astounding athletic success at Ann Arbor, Owens was pressured to marry his high school sweetheart, Minnie Ruth Solomon, with whom he had fathered a child three years earlier. Academic difficulties added to his ordeal. Coming from a home and high school bare of intellectual aspirations, Owens found it impossible to perform well academically while striving for athletic stardom. For two years at Ohio State he stayed on academic probation; low grades made him ineligible for the indoor track season during the winter quarter of 1936.

Allowed again to compete during the spring quarter outdoor track season, Owens set his sights on winning a place on the 1936 Olympic team. His great obstacle was a less-heralded but strong Temple University athlete, Eulace Peacock. A varsity football running back, Peacock had already beaten Owens in five of their previous six head-to-head sprints and long jumps. At the Penn Relays in late April, however, the heavily muscled Peacock snapped a hamstring that kept him limping through the Olympic trials.

Eighteen African American athletes represented the United States in the 1936 Olympics in Berlin, dominating the popular track and field events and winning fourteen medals, nearly one-fourth of the fifty-six medals awarded the U.S. team in all events. Owens tied the world record in the 100-meter sprint and broke world records in the 200-meter sprint, the long jump, and the 4-by-100-meter relay to win four gold medals. On the streets, in the Olympic village, and at the stadium, his humble demeanor and ready smile mesmerized foes and friends alike. As part of its concerted propaganda efforts, the Nazi regime commissioned German filmmaker Leni Riefenstahl to make a film of the games. The resulting film, Olympia, released in 1938, featured Owens prominently. German chancellor Adolf Hitler ceremoniously attended the games to cheer for German athletes. In the most enduring of all sports myths, Hitler supposedly “snubbed” Owens, refusing to shake his hand after his victories; Hitler allegedly stormed out of the stadium enraged that Owens’s athleticism refuted the Nazi dogma of Aryan superiority. This morally satisfying, endearingly simple yarn has no basis in fact. Spread by the Baltimore Afro-American (8 Aug. 1936) and other American newspapers, the story quickly became enshrined as one of the great moral minidramas of our time.

Jesse Owens bursts into action at the 1936 Olympics in Berlin, Germany, where he tied one and set three new world records. Bettmann/Corbis

After the Berlin Games, Owens incurred the wrath of Olympic and Amateur Athletic Union (AAU) officials when he returned home to capitalize on various commercial offers rather than complete an exhibition tour of several European cities; the tour had been arranged to help pay the expenses of the U.S. team. He left the tour in London, provoking the AAU to ban him from future amateur athletic competition. Supported in his decision by Snyder, Owens returned to the United States to cash in on numerous endorsement offers. Most of the offers proved bogus, however, but from Republican presidential candidate Alf Landon he received a goodly sum to campaign for black votes. Shortly after Landon’s defeat, Owens was selected as the Associated Press Athlete of the Year, and on Christmas Day 1936 he won a well-paid, highly publicized race against a horse in Havana, Cuba. Various other fees for appearances and endorsements brought his earnings during the four months following the Berlin Olympics to about twenty thousand dollars.

For the next two years he barnstormed with several athletic groups, supervised playground activities in Cleveland, and ran exhibition races at baseball games. In 1938 he opened a dry-cleaning business in Cleveland, but within the year it went bankrupt. Now with three daughters and a wife to support, he nevertheless returned to Ohio State hoping to finish his baccalaureate degree. He gave up that dream just a few days after Pearl Harbor, and during World War II he held several short-term government assignments before landing a job supervising black workers in the Ford Motor Company in Detroit.

With the onset of the cold war, in the late 1940s Owens enjoyed a rebirth of fame. In 1950 he was honored by the Associated Press as the greatest track athlete of the past half century. Moving to Chicago, he served briefly as director of the South Side Boys’ Club, the Illinois State Athletic Commission, and the Illinois Youth Commission, and emerged as an effective public speaker extolling patriotism and athleticism to youth groups, churches, and civic clubs. In 1955 the U.S. State Department tapped him for a junket to India, Malaya, and the Philippines to conduct athletic clinics and make speeches in praise of the American way of life. At government expense, in 1956 he went as a goodwill ambassador to the Melbourne Olympics, then served for a time in President Dwight D. Eisenhower’s People-to-People Program. Republican to the marrow, Owens largely ignored the civil rights movement.

Deprived of White House patronage when the Democrats returned to power in 1960, he linked his name to a new public relations firm, Owens-West & Associates, in Chicago. While his partner managed the business, Owens stayed constantly on the road addressing business and athletic groups. For several years he carelessly neglected to report his extra income and in 1965 was indicted for tax evasion. He pleaded no contest and was found guilty as charged by a Chicago federal judge. At the sentencing, however, the judge lauded Owens for supporting the American flag and “our way of life” while others were “aiding and abetting the enemy openly” by protesting the Vietnam War. To his great relief, Owens was required merely to pay his back taxes and a nominal fine.

At the Mexico City Olympics in 1968, the politically conservative Owens reacted in horror to the demonstrative Black Power salutes of track medalists TOMMIE SMITH and John Carlos. He demanded of them an apology; they dismissed him as an Uncle Tom. Two years later, in a book ghostwritten by Paul Neimark, Blackthink: My Life as Black Man and White Man (1970), Owens savagely attacked Smith, Carlos, and others of their ilk as bigots in reverse. Laziness, not racial prejudice, condemned American blacks to failure, Owens insisted. “If the Negro doesn’t succeed in today’s America, it is because he has chosen to fail” (84). In response to hostile reactions from black readers and reviewers, Owens again collaborated with Neimark to rephrase his principles in more moderate terms published in I Have Changed (1972). Two more Neimark-Owens potboilers, The Jesse Owens Story (1970) and Jesse: A Spiritual Autobiography (1978), blended reminiscences with prescriptions of the work ethic, patriotism, and religious piety as means to success.

Owens’s own success in the 1970s came largely from contracts with major corporations. Atlantic Richfield Company (ARCO) owned his name for exclusive commercial use and sponsored annual ARCO Jesse Owens games for boys and girls. At business conventions and in advertisements, Owens also regularly represented Sears, United Fruit, United States Rubber, Johnson & Johnson, Schieffelin, Ford Motor Company, and American Express. His name was made all the more useful by a bevy of public awards. In 1972 he finally received a degree from Ohio State, an honorary doctorate of athletic arts. In 1974 he was enshrined in the Track and Field Hall of Fame and honored with a Theodore Roosevelt Award from the National Collegiate Athletic Association for distinguished achievement since retirement from athletic competition.

To his black critics, the aging Owens was an embarrassment, a throwback to the servile posture of BOOKER T. WASHINGTON; to his admirers, his youthful athleticism and enduring fame made him an inspiration. On balance, his inspirational achievements transcended race and even politics. In 1976 he received the Medal of Freedom from Republican president Gerald Ford for serving as “a source of inspiration” for all Americans; in 1979 Democratic president Jimmy Carter presented Owens a Living Legends award for inspiring others “to reach for greatness.” Within the next year, Owens died in Tucson, Arizona.

Barbara Moro’s transcript of interviews with Jesse Owens and Ruth Owens in 1961 is in the Illinois State Historical Library, Springfield.

Bachrach, Susan D. The Nazi Olympics: Berlin 1936 (2000).

Baker, William J. Jesse Owens: An American Life (1986).

Hart-Davis, Duff. Hitler’s Games: The 1936 Olympics (1986).

Johnson, William O., Jr. All That Glitters Is Not Gold: The Olympic Game (1972).

Mandell, Richard D. The Nazi Olympics (1971).

Obituary: New York Times, 1 Apr. 1980.

—WILLIAM J. BAKER