PENNINGTON, JAMES WILLIAM CHARLES

PENNINGTON, JAMES WILLIAM CHARLES PENNINGTON, JAMES WILLIAM CHARLES

PENNINGTON, JAMES WILLIAM CHARLES(15 Jan. 1809–20 Oct. 1870), escaped slave, minister, and abolitionist, was born James Pembroke in Hagerstown, Maryland, to Bazil, a handyman and shepherd, and a woman named Nelly. Both his parents were slaves. James Tighlman, their owner, gave James’s mother and an older brother to his son, Frisbie Tighlman. The family was reunited when Frisbie Tighlman purchased Bazil, though they were relocated to an area some two hundred miles from Maryland’s Eastern Shore.

Even though the family had been reunited, as slaves James’s parents were still unable to provide the nurturing attention he required. On one occasion Tighlman beat Bazil in James’s presence, and his remarks to Bazil had a lasting impact on the young boy: “I will make you know that I am master of your tongue as well as of your time” (Pennington, 7). While he did not immediately escape, James was committed to striking for freedom; in his mind he was never a “slave” after this incident. Although he, too, would experience the “tyranny and abuse of the overseers” (3), he managed to equip himself with skills requisite for life as a free man. At age eleven, he became a trained stonemason, and he worked as a certified blacksmith for more than nine years. But the expert blacksmith yearned for freedom and would become a fugitive. “The hour was come,” and he determined that he had to act “or remain a slave for ever” (7).

One afternoon in November 1827, he struck for freedom and, several days later, arrived in Pennsylvania, where the first person he met was a Quaker woman. He lived and worked for a while with a Quaker couple, Phebe and William Wright, who taught him to read. To protect himself, he adopted the name James William Charles Pennington. (Pennington was a common name among Pennsylvania Quakers.) After living with and working for Quaker families, he settled in Newtown, Long Island, New York. He became a Christian, and this intensified his concern for his parents and eleven siblings, as well as others in slavery.

Pennington decided to fight against the institution of slavery from northern soil. With the guidance of the Presbyterian family with whom he resided in Newtown, Pennington began formal preparation for the ministry in 1835. He moved to New Haven, Connecticut, where he taught in a black school, and assisted the pastor of Temple Street Congregational Church. Although Pennington could not formally register at Yale Divinity School, he was allowed to sit in the hallway and listen to lectures. Three years later he returned to Newtown, was ordained as a Presbyterian minister, and served as pastor of the black Presbyterian Church from 1838 to 1840. During the next thirty-two years Pennington served seven churches in three denominations (Presbyterian, Congregational, and African Methodist Episcopal Zion) and five states.

On 16 July 1840 Pennington was called to serve at the Talcott Street (Fifth) Congregational Church in Hartford, Connecticut, and he came to play a role in the celebrated Amistad case, examining whether captured Africans who had rebelled and taken over the ship (the Amistad) they were being transported in were legally slaves. Most of the captives were from the Mende region of West Africa, in present-day Nigeria, and in April 1840 Judge Andrew T. Judson ruled that their leader CINQUÉ and the others be freed, delivered to the president of the United States, and returned to Africa.

In July 1840 Pennington helped raise money for the captives, whose case had been appealed to the U.S. Supreme Court, where former President John Quincy Adams argued the captives’ case. While the U.S. Supreme Court reaffirmed that they be freed, it did not require that the president return them to Africa. Along with his wealthy friend, the New York merchant Lewis Tappan, Pennington raised enough funds for the return of the Amistad victims. In September 1841 Pennington organized and was elected president of the Union Missionary Society. Hosted by Pennington’s church, the society sent the first two missionaries from an African American mission society to the interior of Africa.

Pennington’s role in helping the Amistad captives and in sending African American missionaries to Africa enhanced his popularity in Connecticut. In 1843 he was selected to represent the Connecticut Anti-Slavery Society at the World Anti-Slavery Society Convention in London. He also represented the American Peace Society and his own Union Missionary Society at the World Peace Convention meeting in London that year. He then returned to Hartford, where he was twice elected president of the Hartford Central Association of Congregational ministers.

Still legally a fugitive slave, Pennington tried to secure his freedom. As of 1844 he had not even told his wife, Harriet, that he had escaped from slavery. (It is not known when Pennington married Harriet—who died in 1846—and there is no record that the couple had children.) He did not reveal his status to his congregation until 1846, when he traveled to Jamaica, in part to raise funds to purchase his freedom. After his return later that year, Pennington played a major role in the creation of the American Missionary Association, which absorbed his Union Missionary Society. Pennington was appointed to the executive committee of the new organization.

Following the death of Theodore S. Wright, in 1847, Pennington was invited to become the new pastor of Shiloh Presbyterian Church in New York City, the most influential African American Presbyterian congregation in the nation. After concluding a promised return to Talcott and becoming vice president of the National Negro Convention Movement, a northern association of blacks committed to improving the condition of freemen and working for the abolition of slavery in the South, Pennington began his duties as pastor at Shiloh. While settling in as the pastor of his new congregation, Pennington married Almira Way at the home of a Mr. Goodwin, the former editor of the Hartford Courant newspaper. It is not known whether the couple had children.

In 1849 Pennington made a second European tour to promote the cause of peace and abolitionism. On this visit the University of Heidelberg in Germany awarded him the doctor of divinity degree. He was the first African American to receive this honor. Conferred on 19 December 1849, it acknowledged Pennington foremost as a leader of his people as well as one who had published distinguished literary works while still legally a slave. Passage of the Fugitive Slave Law in 1850 prompted Pennington to more assiduously pursue the legal purchase of his freedom. From Scotland, where he was lecturing as a guest of the Glasgow Female Anti-Slavery Society, Pennington inquired whether he should return. His friend John Hooker of Farm-ington, Connecticut, advised Pennington to stay abroad while Hooker negotiated his purchase. On 3 June 1851 Hooker paid the Tighlman estate $150, making Pennington the property of Hooker. After contemplating the irony of “owning” a man with a doctor of divinity degree, Hooker executed the documents making Pennington a free man. James Pembroke had been transformed into James Pennington.

Now free, Pennington later purchased the freedom of his brother Stephen. Both of his parents had died in slavery, as had a sister. Several of his other siblings tasted freedom, though some were sold south. Legally free and armed with a doctorate in divinity, Pennington became even bolder. In June 1855 he defied the New York City law that prohibited African Americans from riding on the inside of a horse-drawn car. He was arrested and charged with violent resistance, but the New York Supreme Court, on appeal, ruled in Pennington’s favor; segregation was subsequently made illegal on public transportation in New York City, one hundred years before ROSA PARKS initiated the Montgomery bus boycott in Alabama.

In addition to his activism, Pennington also contributed to African American scholarship, publishing twenty-four articles and sermons, including An Address Delivered at Newark, New Jersey, at the First Anniversary of West Indian Emancipation, August 1, 1839, and “The Self-Redeeming Power of the Colored Races of the World” in the Anglo-African Magazine (1859). He also published two books: his autobiography, The Fugitive Blacksmith (1850), and A Textbook History of the Origin and History of the Colored People (1841), which was one of the earliest works of African American historical scholarship.

Yet despite his many achievements, Pennington appears to have succumbed to alcohol addiction in the 1850s, perhaps brought on by the pressures of service. After 1865 he was no longer the spiritual leader of Shiloh. While he recovered from alcoholism, Pennington wrote several significant articles on the future of the black race, though he would never recapture the fame he had once known. He served as an ordained AME African Methodist Episcopal minister in Natchez, Mississippi, in 1865 and was pastor of a Congregational church in Portland, Maine, in 1868 before going to a Presbyterian church in Jacksonville, Florida, where he died in October 1870.

Nineteen unpublished letters, written by James W. C. Pennington between 1840 and 1870, are held at the American Missionary Association Archives, Amistad Research Center, Tulane University, New Orleans, Louisiana.

Pennington, James W. C. The Fugitive Blacksmith; or, Events in the History of James W. C. Pennington, Pastor of a Presbyterian Church, New York, Formerly a Slave in the State of Maryland, United States (1849), reprinted in Five Slave Narratives, ed. William L. Katz (1969).

Thomas, Herman E. James W. C. Pennington: African American Churchman and Abolitionist (1995).

Washington, Joseph R. The First Fugitive and Foreign and Domestic Doctor of Divinity (1990).

—HERMAN E. THOMAS

PERRY, LINCOLN.

PERRY, LINCOLN.See Fetchit, Stepin.

PETRY, ANN

PETRY, ANN(12 Oct. 1908–30 Apr. 1997), author and pharmacist, was born Ann Lane in Old Saybrook, Connecticut. The youngest daughter of Peter C. Lane, a pharmacist and proprietor of two drugstores, and Bertha James, a licensed podiatrist, Ann Lane grew up in a financially secure and intellectually stimulating family environment. After graduating from Old Saybrook High School, she studied at the Connecticut College of Pharmacy (now the University of Connecticut School of Pharmacy) and earned her Graduate in Pharmacy degree in 1931. For the next seven years Lane worked as a pharmacist in the family business. Her family’s long history of personal and professional success served as the foundation for her own professional accomplishments. She cherished the family’s stories of triumph over racism and credited them with having “a message that would help a young black child survive, help convince a young black child that black is truly beautiful” (Petry, 257). These family narratives and their message of empowerment enabled her to persevere in the sometimes-hostile racial environment of New England.

After Lane’s marriage on 22 February 1938 to George D. Petry, of New Iberia, Louisiana, she and her husband relocated to Harlem, New York City. Harlem provided her with the environment in which to expand her creative talents and source material for her future fiction. From 1938 to 1944 Petry explored a variety of creative outlets: performing as Tillie Petunia in Abram Hill’s play On Striver’s Row at the American Negro Theater, taking painting and drawing classes at the Harlem Art Center, and studying creative writing at Columbia University. She also served as an editor and reporter for People’s Voice from 1941 to 1944. Equally important for her creative work, however, was the time Petry spent organizing the women in her community for Negro Women Inc., a consumer advocacy group, and running an after-school program at a grade school in Harlem. These experiences gave Petry insight into the harsh realities facing working-class black Americans and offered her a distinct contrast to the financially comfortable world in which she was raised. Witnessing the struggles of impoverished black families in Harlem and observing the social codes of more affluent communities, such as Old Saybrook, enriched Petry’s fiction, which explores the ways in which social expectations, along with the forces of racism and sexism, can constrain individual lives.

Ann Petry’s novel The Street, about a single mother in Harlem and her efforts to protect her child from the street’s dangers, sold 1.5 million copies in 1946. Schomburg Center

Petry published her first short story shortly after moving to Harlem. “Marie of the Cabin Club” (1939) appeared in an issue of Afro-American, a Baltimore newspaper, under the pseudonym Arnold Petri. In 1943, under her own name, Petry published “On Saturday the Siren Sounds at Noon” in the Crisis. An important turning point in her career came when this publication caught the attention of an editor who suggested that she apply for the Houghton-Mifflin Literary Fellowship Award. She submitted the first chapters and an outline of what would become her most famous novel, The Street, and won the fellowship in 1945. Funded by a $2,400 stipend, Petry finished the novel in 1946.

The Street garnered immediate critical and popular acclaim. Twenty thousand copies sold in advance of its release, and the novel’s sales surpassed 1.5 million copies, making it the first novel by a black woman to sell over a million copies. The story of Lutie Johnson, an ambitious black woman trying to work toward financial security, The Street uses the bleak landscape of an impoverished Harlem street to personify the relentlessness of racism. In its use of some elements of urban realism, The Street evokes comparison to RICHARD WRIGHT’S Native Son, in which Bigger Thomas’s social position—poor, black, and uneducated—inevitably leads to violence and tragedy. But Petry’s novel offers what some critics consider a more nuanced examination of the way in which racism shapes black experience. Lutie Johnson not only contends with racism but also confronts sexism from white and black communities alike on an almost daily basis. Furthermore, unlike Bigger Thomas, she is a reasonably well-educated and ambitious woman, driven by the mythology of the American Dream and convinced that her hard work will ultimately be rewarded. Lutie’s tragic failure to achieve her goals indicts not only the racism of American society but also the deceptive mythologies that encourage people like Lutie to believe that they have an equal chance at success.

The Street’s enthusiastic reception made Petry a public figure. Seeking privacy, she and her husband returned in 1947 to Old Saybrook, where they lived for the rest of Petry’s life. In the same year, Petry published Country Place, a novel that also explores the role of environment and community on individuals, though it does not deal explicitly with black characters or experiences. In 1949 Petry gave birth to the couple’s only child, Elisabeth Ann Petry, and published the first of what would be several books for children and young adults, The Drugstore Cat.

While it is not as well known as The Street, The Narrows, published in 1953, further complicates the issues Petry raises in her first novel. Set in a fictional New England city, The Narrows explores the repercussions of a love affair between a black man and a white woman. The nearly inevitable downfall of Link Williams in The Narrows revisits Lutie Johnson’s situation in The Street. Both characters are ambitious and intelligent, yet constrained by the mechanisms of racism, which prevent them from ever really succeeding. The Narrows offers a pointed commentary on social behavior, not only interracial romance but also excessive class consciousness. Within this frame, Petry suggests that social codes and behavioral expectations are damaging to black and white communities alike.

Petry’s themes of community relationships and the complexity of black experience in the United States continued in her later publications, including the nonfiction children’s books Harriet Tubman, Conductor on the Underground Railroad (1955), Tituba of Salem Village (1964), and Legends of the Saints (1970). In 1971 Petry published Miss Muriel and Other Stories. A compilation of stories from the 1940s through 1971, the collection draws on Petry’s experiences in Harlem as well as in small-town America. In addition to writing, Petry undertook several visiting lectureships, earned a National Endowment of the Arts creative writing grant in 1978, and was awarded several honorary degrees, including an honorary DLitt from Suffolk University in 1983 and honorary degrees from the University of Connecticut in 1988 and Mount Holyoke College in 1989. Petry died in Old Saybrook on 30 April 1997.

As the first best-selling African American woman writer, Ann Petry holds a firm place in American literary history as both a groundbreaker and a literary predecessor to some of the twentieth century’s most significant black women novelists. The works of Gloria Naylor, ALICE WALKER, and TONI MORRISON continue to explore the complicated interplay of race, gender, and socioeconomic status that Petry illuminated so well in her fiction.

First editions of Petry’s work, correspondence, and critical reviews are housed in the Ann Petry Collection at the African American Research Center, Shaw University, Raleigh, North Carolina. Additional manuscript materials may be found at the Mugar Memorial Library at Boston University; the Beinecke Rare Book and Manuscript Library at Yale University, New Haven, Connecticut; the Woodruff Library at Atlanta University; and the Moorland-Springarn Research Center at Howard University, Washington, D.C.

Petry, Ann. “Ann Petry.” Contemporary Authors Autobiography Series (1988).

Ervin, Hazel Arnett. Ann Petry: A Bio-Bibliography (1993).

Holladay, Hilary. Ann Petry (1996).

Obituary: New York Times, 30 Apr. 1997.

—CYNTHIA A. CALLAHAN

PICKENS, WILLIAM

PICKENS, WILLIAM(15 Jan. 1881–6 Apr. 1954), was born in Anderson County, South Carolina, the sixth of ten children of Jacob and Fannie Pickens, both of whom were former slaves. The family of sharecroppers moved frequently—some twenty times by Pickens’s estimate—and relocated to Arkansas in 1887. William was raised in a household in which learning was revered, and he became valedictorian of his graduating class at Union High School in Litde Rock in 1899. Following a summer working with his father in railroad construction in Arkansas, Pickens entered Talledega College, a missionary institution in Alabama, where he majored in foreign languages, and earned a BA in 1902. Pickens earned a second bachelor’s degree, in linguistics, from Yale University, in New Haven, Connecticut, where he received the Phi Beta Kappa key in 1904. He later earned an MA degree from Fisk University, in Nashville, Tennessee; a doctorate in Literature from Selma University (Alabama); and an LLD from Wiley University (now Wiley College) in Marshall, Texas.

In 1905 Pickens married Minnie Cooper McAlpine, a graduate of Touga-loo College, with whom he had three children: William, Harriet, and Ruby. Pickens possessed diverse talents and authored two autobiographies, Heir of Slaves (1911) and Bursting Bonds (1923), as well as a short-story collection, Vengeance of the Gods (1922), and a collection of essays, The New Negro (1916). Between 1904 and 1914 Pickens taught foreign languages at his alma mater, Talladega, before moving to Wiley University to head their Greek and sociology departments. The following year he accepted a position as dean of Morgan College (now Morgan State University) in Baltimore, Maryland. Although he initially supported BOOKER T. WASHINGTON’s more pragmatic approach to race relations, Pickens evolved into a civil rights militant fairly early in his intellectual career. He supported W. E. B. DU BOIS’s radical Niagara Movement and was a charter member of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP) and the American Civil Liberties Union. He was also ecumenical in his organization affiliations, working to some degree with the League for Industrial Democracy, the YMCA, and the Council for Pan-American Democracy. Given his broad education and training, Pickens was something of a maverick. He proposed to the businesswoman MADAME C. J. WALKER that he accompany her on a trip around the world and write a book about her travels, and in the early 1920s he flirted briefly with MARCUS GARVEY’s United Negro Improvement Association (UNIA) while he was still an NAACP employee. Pickens was later a fierce critic of the UNIA, however, and even demanded that Garvey be imprisoned.

In 1919 Pickens left Morgan College—where he had risen to the vice presidency—to take a position as assistant to JAMES WELDON JOHNSON of the NAACP. As a founding member of the association, Pickens was well connected with its leadership and had also tirelessly recruited members at Talladega, Wiley, and Morgan College. In 1915 he had accompanied the NAACP chairman Joel E. Spingarn on a dangerous fact-finding mission to Oklahoma, to gather information for a test case challenging Jim Crow on the railroads. In 1920 Johnson was appointed the first black executive secretary of the NAACP, and Pickens was subsequently appointed to the post of field secretary.

During his tenure as field secretary, Pickens shepherded the NAACP through a period of fluctuating membership during the 1920s and the Depression, and he helped lay the groundwork for the association’s massive increase in resources and membership in the 1940s. His relations within the NAACP, however, were often rocky, especially with WALTER WHITE, who succeeded Johnson as executive secretary in 1930. Mary White Ovington, chair of the NAACP board, also reprimanded Pickens in 1931 for praising the Communist Party’s work in support of the SCOTTSBORO BOYS in the midst of open hostility between the Communists and the NAACP. Pickens subsequently adopted the NAACP party line and even traveled to Scottsboro, where he tried, unsuccessfully, to persuade the nine imprisoned youths to abandon their Communist backers. Pickens’s decision to accept a position with the U.S. Department of the Treasury in 1942 probably was motivated, at least in part, by his deteriorating relations with White. He was succeeded as field secretary by the radical grassroots organizer ELLA BAKER.

In 1942 Pickens was cited as a subversive by the House Un-American Activities Committee (HUAC) and its conservative chairman, Martin Dies. In a gesture that eerily presaged Senator Joseph McCarthy’s allegations in Wheeling, West Virginia, almost a decade later, Dies, a conservative Texas Democrat, presented the House of Representatives with a list of thirty-nine “subversives” who should be removed from the federal payroll. Of those people, William Pickens was the only one in federal employ at the time. As a director of the War Savings Staff, Pickens was charged with increasing the number of African Americans purchasing war bonds. In short order, a measure was introduced that held up the federal budget until such time as Pickens’s allegiances could be ascertained. Wary of provoking conservative southern Democrats who had perpetually threatened to hobble Franklin Roosevelt’s presidency, Pickens gave a politic response to the charges. “I do not know Mr. Dies,” he remarked, “but feel sure from the position he holds that he would not want to speak anything but the truth. Therefore, I conclude that somebody has misled Mr. Dies” (press release, 18 Sept. 1942, Associated Negro Press Papers, Library of Congress).

With the budget hanging in the balance, some members of the HUAC were surprised at Pickens’s appearance—not knowing that he was African American. Pickens’s appearance thus gave the arch-segregationist Dies an opportunity to link subversion and civil rights. Northern Democrats, mindful of the Great Migration and the swelling numbers of black Democratic voters, however, were less than thrilled with the prospect of questioning Pickens. William Dawson, the black freshman congressman from Chicago, devoted his maiden speech to Pickens’s defense, and Walter White sent a series of letters to members of the House of Representatives protesting the charges against Pickens. Those charges were ultimately dismissed, and Pickens remained in his position at the Treasury Department.

After World War II, Pickens attempted to return to the NAACP but was blocked by Walter White. Shut out of the organization where he had worked for twenty-three years, Pickens remained with the Treasury Department until 1951, when he retired. Pickens’s political radicalism diminished somewhat during this period, and strains of his youthful admiration for Booker T. Washington might be seen in his Treasury Department campaigns to educate blacks on economic matters, savings bonds, and thrift. Pickens traveled extensively after his retirement and died during a cruise aboard the SS Mauritania, on 6 April 1954, just one month before the U.S. Supreme Court issued its landmark school desegregation ruling in Brown v. Board of Education.

Pickens played a significant role in the development of the NAACP. Between 1920 and 1940 he recruited more members and organized more branches than any other officer in the association, and his efforts helped transform the organization from a small civil rights lobby to a mass organization with nationwide influence.

The primary archival collection of William Pickens’s papers is housed at the Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture of New York City. Substantial information regarding his public career, however, can be found in the NAACP collection at the Library of Congress.

Pickens, William. Bursting Bonds (1923, 1991).

_______. Heir of Slaves (1911).

Avery, Sheldon. Up from Washington: William Pickens and the Negro Struggle for Equality, 1900–1954 (1989).

Obituary: New York Times, 7 Apr. 1954.

—WILLIAM J. COBB

PICKETT, BILL

PICKETT, BILL(5 Dec. 1871–2 Apr. 1932), African American rodeo entertainer, was born in Jenks-Branch community in Travis County, Texas, the son of Thomas Jefferson Pickett, a former slave, and Mary “Janie” Virginia Elizabeth Gilbert. The second of thirteen children, Pickett reportedly grew to be five feet, seven inches tall and approximately 145 pounds. Little is known about his early childhood, except that he attended school through the fifth grade. Afterward he took up ranch work and soon developed the skills, such as roping and riding, that would serve him well in rodeo. On 2 December 1890 Pickett married Maggie Turner of Palestine, Texas, the daughter of a white southern plantation owner and his former slave. They had nine children. The Picketts joined the Taylor Baptist Church, where Pickett served as deacon for many years.

Sometime prior to 1900 Pickett and his brothers organized the Pickett Brothers Bronco Busters and Rough Riders Association, operating out of Taylor, Texas. Benny was president, Bill was vice-president, Jessie was treasurer, Berry was secretary, and Charles was general manager. They proudly advertised in their handbills: “We ride and break all wild horses with much care. Good treatment to all animals. Perfect satisfaction guaranteed. Catching and taming wild cattle a specialty.” The association operated for several years and boasted of an excellent reputation among the residents of Taylor.

By this time Pickett had originated the tactic of “bulldogging,” for which he would become internationally known. A skilled steer wrestling maneuver, bulldogging involved the performer’s riding alongside a steer, throwing himself on its back, gripping the horns, and twisting the animal’s neck and head upward, causing the beast to fall over. The rider and the steer would skid to a stop in a cloud of dust. Pickett would then sink his teeth into the steer’s upper lip or nose and release both his hands. It is believed that Pickett developed his technique as a result of having witnessed a cattle dog holding a “cow critter” with its teeth. According to author Col. Bailey C. Hanes, Pickett perfected the maneuver when working with cattle in the brush country of Texas, where direct interaction with the steer was required to bring the animal under control. Pickett soon began displaying his bulldogging technique before audiences, first at stockyards and later at county fairs. These audiences would watch in amazement as Pickett restrained a steer only by his vise-like teething grip on the animal’s lip or nose. This unique approach to steer wrestling immortalized Pickett, as it became the first original rodeo technique that can be traced to one individual.

In 1904 Pickett became an instant celebrity at the Cheyenne Frontier Days in Wyoming. The Wyoming Tribune reported in part,

The event par excellence of the celebration this year is the great feat of Will Pickett, a Negro who hails from Taylor, Texas . . . . Pickett is not a big man but is built like an athlete and his feat will undoubtedly be one of the great features of this year’s celebration. It is difficult to conceive how a man could throw a powerful steer with his hands unaided by rope or a contrivance of some kind and yet Pickett accomplishes this seemingly impossible task with only his teeth.

New York’s Harper’s Weekly had sent John Dicks Howe, a special reporter, to cover the event. He reported,

20,000 people watched with wonder and admiration a mere man, unarmed and without a device or appliance of any kind, attack a fiery, wild-eyed and powerful steer and throw it by his teeth. . . . The crowd was speechless with horror, many believing that the Negro had been crushed . . . Pickett arose uninjured, bowing and smiling. So great was the applause that the darkey again attacked the steer . . . and again threw it after a desperate struggle.

On 10 August 1905 Pickett was honored with national attention in Leslie’s Illustrated Weekly tabloid as “a man who outdoes the fiercest dog in utter brutality.” Capitalizing on his popularity, he signed a contract in 1907 with the Miller Brothers, owner of the famous 101 Ranch Wild West Show based along Oklahoma’s Cherokee Strip. Becoming the show’s headline performer, Pickett made appearances across the United States as well as in Canada, Mexico, Argentina, and England. Colonel Zack T. Miller described Pickett as “the greatest sweat and dirt cowhand that ever lived—bar none.” His style of bulldogging gave him many nicknames, including the “Dusky Demon,” “The Modern Ursus,” and the “Wonderful Colored Cowboy.” The wiry performer was also acclaimed for his bronco riding and steer and calf roping talents. Around 1914 he starred in a silent film called The Bull-Dogger, produced by the Norman Film Manufacturing Company. The film advertised the techniques of his steer-wrestling artistry, but no copies of the film have ever been located.

Pickett retired as a rodeo performer in 1916 and worked on the 101 Ranch until 1920, before settling on a 160-acre homestead near Chandler, Oklahoma. After Maggie’s death in 1929, he returned to the 101 Ranch as a ranch hand to overcome personal financial difficulties brought on by the Great Depression. While attempting to cut horses out of a herd, Pickett was roping a chestnut stallion on foot when the horse suddenly turned on him and fractured his skull. Never regaining consciousness, Pickett died eleven days later at a hospital in Ponca City, Oklahoma. The Cherokee Strip Cowpunchers Association erected a marker in honor of him, with a hand inscription of “Bill Pickett, C.S.C.P.A.,” on the 101 Ranch that he made famous, near the monument to Ponca Indian Chief White Eagle.

Hanes, Colonel Bailey C. Bill Pickett, Bulldogger (1977).

Katz, William Loren. Black Indians: A Hidden Heritage (1986).

—LARRY LESTER

PINCHBACK, P. B. S.

PINCHBACK, P. B. S.(10 May 1837-21 Dec. 1921), politician, editor, and entrepreneur, was born Pinckney Benton Stewart Pinchback in Macon, Georgia, the son of William Pinchback, a Mississippi plantation owner, and Eliza Stewart, a former slave of mixed ancestry. Because William Pinchback had taken Eliza to Philadelphia to obtain her emancipation, Pinckney was free upon birth.

In 1847 young Pinckney and his older brother Napoleon Pinchback were sent to Cincinnati to be educated. When his father died the following year, Eliza and the rest of the children fled Georgia to escape the possibility of re-enslavement and joined Pinckney and Napoleon in Cincinnati. Because the family was denied any share of William Pinchback’s estate, they soon found themselves in financial straits. To help support his family, Pinckney worked as a cabin boy on canal boats in Ohio and later as a steward on several Mississippi riverboats. In 1860 he married Nina Emily Hawthorne. Four of their six children survived infancy.

When the Civil War started, Pinchback made his way back to the South. In May 1862 he jumped ship at Yazoo City, Mississippi, and managed to reach New Orleans, already in Union hands. There he enlisted in a white Union regiment as a private, but within a few months he was assigned to recruit black soldiers. He rose in rank to captain in the Second Louisiana Native Guards, later renamed the Seventy-fourth U.S. Colored Infantry. In September 1863 Pinchback resigned from the army, citing discriminatory treatment by white officers and voicing opposition to the army’s practice of better compensating white soldiers. He reentered the army as a recruiter when General Nathaniel P. Banks, commander of the New Orleans Union forces, decided to expand the participation of African American troops in the defense of New Orleans. When Banks refused Pinchback a commission as captain, he resigned again.

Pinchback’s advocacy of African American rights started during the Civil War. As early as November 1863 he spoke in New Orleans at a rally for political rights, asserting that if black Americans were not allowed to vote, they should not be drafted into the Union army. He then spent two years in Alabama speaking out publicly in support of African American education. On his return to Louisiana in 1867, he became involved in state politics. He was elected to the constitutional convention of 1868, where he worked to create a state-supported public school system and wrote the provision guaranteeing racial equality in public transportation and licensed businesses.

In 1868 Pinchback was elected to the Louisiana State Senate and, as a delegate, attended the Republican National Convention in Chicago. In 1871 he became president pro tempore of the senate and, because of this position, advanced to lieutenant governor upon the death of the incumbent Oscar J. Dunn late that year. Pinchback clashed politically with Governor Henry C. Warmoth, a carpetbagger who had previously vetoed a civil rights bill that Pinchback sponsored. When Warmoth was impeached in 1872, Pinchback served briefly as acting governor, from 9 December 1872 to 13 January 1873. He was the only African American to hold a governorship during Reconstruction.

Although Pinchback, a Republican, was an important figure in state politics, he was unable to hold any other major political office. Earlier in 1872 radicals in the state’s Republican Party had sought to nominate him for governor, but he declined the nomination in the interest of preserving party unity. As a reward for his withdrawal, he was nominated for the position of U.S. congressman at large, and he apparently won the election. While the outcome was being contested by the Democrats, during Pinchback’s tenure as acting governor, he was also elected by the state legislature to the U.S. Senate, again drawing protests from the Democrats. Eventually their allegations that Pinchback was guilty of bribery and election irregularities led to his being denied both the seat in the U.S. House of Representatives and the one in the Senate. This was not Pinchback’s first brush with corruption. In 1870, when he was serving as a state senator, he acted on inside information to purchase a tract of land that he quickly sold to the city of New Orleans for a tidy profit.

In 1877 Pinchback left the Republican Party to support the newly elected Democratic governor, F. T. Nicholls. In return, Governor Nicholls appointed him to the state board of education. In 1879 Pinchback served as a delegate to the state constitutional convention, where he drafted a plan to create Southern University. He was a trustee of that school in the 1880s.

Pinchback was active in the New Orleans business community while he was engaged in politics. He was a co-owner of the city’s Louisianian newspaper, which not only gave Pinchback a forum to articulate his political views but also helped shape the political and social opinions of the local African American community. In addition, he operated a brokerage and commission house and from 1882 to 1886 was surveyor of customs for the port of New Orleans.

In 1887 Pinchback entered Straight University Law School and passed the state bar exam. After working as a U.S. marshal in New York City in the early to mid-1890s, he practiced law in Washington, D.C., and became part of the city’s black elite, entertaining often. He continued to profit from worthwhile business ventures as part owner of a cotton mill and sole owner of the Mississippi River Packet Company. His political activities shifted to support of BOOKER T. WASHINGTON, after whose death, however, Pinchback’s clout was sapped. Pinchback died in Washington, D.C.

Collections of Pinchback’s papers are in the Moorland-Spingarn Research Center at Howard University and the Howard-Tilton Memorial Library at Tulane University. Also worth consulting is the correspondence between Pinchback and Booker T. Washington in the Booker T. Washington Papers at the Library of Congress.

Haskins, James. Pinckney Benton Stewart Pinchback (1973).

Ingham, John N., and Lynne B. Feldman. African American Business Leaders (1994).

Simmon, W. J. Men of Mark: Eminent, Progressive and Rising (1887).

Obituaries: Baltimore Afro-American, 30 Dec. 1921; New Orleans Times Picayune and Washington Post, 22 Dec. 1921.

—ERIC R. JACKSON

PIPPIN, HORACE

PIPPIN, HORACE(22 Feb. 1888–6 July 1946), painter, was born in West Chester, Pennsylvania, the son of Horace Pippin. On a biographical questionnaire Pippin listed his mother as Harriet Johnson Pippin, but Harriet may actually have been his grandmother; she was the mother of Christine, a domestic servant, who may have been Pippin’s birth mother. When Pippin was quite young the family moved to Goshen, New York, so that his mother could find work, and it was there that Pippin attended a one-room school through the eighth grade. He showed an ability for and love of drawing while in school, but because he had to help support his family, he began a series of menial jobs at the age of fourteen. In 1905 he took a job as a porter in a hotel, and he worked there until his mother’s death in 1911. He then moved to New Jersey, where he worked at a number of manual labor jobs in industry until April 1917, when the United States declared war on Germany. Pippin enlisted in the army in July 1917 and was trained at Camp Dix, New Jersey, achieving the rank of corporal before leaving basic training.

Pippin continued to sketch, but soon he was sent abroad to France, where he became a part of the famous 369th Infantry, an all-volunteer black regiment (except for the white officers) whose bravery was so extraordinary that the entire regiment was awarded the Croix de Guerre by the French government. In the fall of 1918 Pippin was shot in the right shoulder, and the bullet destroyed muscle, nerves, and bone. His arm hung uselessly from his side, and after five months in army hospitals he was discharged, returning emotionally and physically exhausted to his mother’s relatives in West Chester.

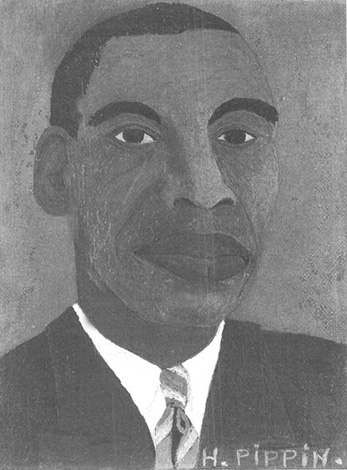

This self-portrait of artist Horace Pippin painted in 1944 is oil on canvas adhered to cardboard. Metropolitan Museum of Art

Pippin was unable to make a living through physical labor and attempted to survive simply on his small soldier’s pension. He met Jennie Ora Featherstone, a widow with a young son, and they were married in 1920. She took in laundry to help support him, but Pippin was psychologically devastated by his disability, and his memories of the war lingered. He found some relief in local American Legion meetings, and ultimately he began to make art again. He began with some decorated cigar boxes and then turned to burning his drawings into wooden panels. He strengthened his arm enough to draw and paint, and he began to create powerful images based on his memories of the war. Making art helped to heal him and gave him a sense of purpose. He soon expanded to oil paints, but because of his injury he rarely painted anything larger than 25 × 30 inches.

Pippin was an unschooled artist, called a “primitive” in the 1930s. However, he had a tremendous ability to relay a narrative using simple, flat forms that moved rhythmically and dramatically across the composition. His works are quite sophisticated in their constructions, even though Pippin stated quite emphatically that he simply painted what he saw. In spite of his talent, viewers of that time often connected his purity of vision with a certain naiveté and believed him to be only an instinctual artist, even linking that quality to the primitivism of Africa.

One of the most powerful images among his early works is The End of the War: Starting Home (1931), which depicts the grim reality of trench warfare. During this time painting was still an extremely slow process for Pippin, and his production was limited. As time went on he became more prolific, moving to images based on calendar art and then to portraits. He also turned to religious themes, images of African American life, interiors, and still life paintings.

In 1937 Pippin began to sell his paintings in local shops, and it was quite possibly in this way that the famous American illustrator N. C. Wyeth and the art critic Christian Brinton saw one of his important works, Cabin in the Cotton I (1935). Pippin’s paintings may also have come to Brinton’s attention through friends of the artist who alerted this connoisseur of new talent. Cabin in the Cotton I was the first of a series of paintings based on what the artist imagined was the African American’s life in the South, and it was the first work to deal with the life of his people, a subject that would soon make up a large part of Pippin’s oeuvre.

Brinton soon championed his new discovery and decided to hang two works by Pippin in the Chester County Art Association’s Sixth Annual Exhibition, which attracted 2,550 people. Pippin’s Cabin in the Cotton I captivated the public, encouraging Brinton to give his full support to his new “discovery,” thus helping connect Pippin to several important figures in the New York art scene, including Holger Cahill, then acting director of the Museum of Modern Art and a tremendous supporter of American folk art. Cahill included Pippin’s work in an important exhibition, Masters of Popular Painting—Artists of the People, at the Museum of Modern Art; Pippin was the only black artist to be included.

During this period ten of Pippin’s paintings and seven burnt-wood panels were also exhibited at the West Chester Community Center, a focus of black cultural activity. Pippin’s work also came to the attention of a Philadelphia dealer, Robert Carlen, and it was while the work was at Carlen’s gallery that Dr. Albert C. Barnes saw it. Barnes, an important collector, was very early interested in art by African Americans, and he immediately purchased several works, as did his assistant, Violet de Mazia. Barnes wrote a new essay for Pippin’s show with Carlen in which he commented on the artist’s ability to tell a story simply and directly with his own language. Both Brinton and Barnes tried on several occasions to “educate” Pippin about modern art and painting, but, fortunately, Pippin ignored them both and continued on his own individual path. However, Carlen and Pippin formed an enduring business relationship. Pippin later exhibited with the New York gallery of Edith Halpert, while still exhibiting with Carlen in Philadelphia.

Pippin’s African American heritage continued to offer subjects for the artist, ranging from images of Abraham Lincoln to portraits of the famous soprano MARIAN ANDERSON to scenes of everyday life. He created a series on the abolitionist John Brown, in addition to painting a number of images with religious themes, which reflected both his own devout nature and the importance of the church in black American life. Pippin was opposed to war and depicted the “peaceable kingdom” in a number of works titled Holy Mountain. He loved nature and continued to paint floral images as well as interiors remembered from his childhood. His originality attracted a wide audience, and his work became increasingly sophisticated over time, drawing admiration from a number of critics of modern art.

Unfortunately his last years, while financially secure, were personally unhappy. His stepson left to join the armed forces, and his wife was institutionalized because she suffered from emotional problems. Having grown more and more lonely, Pippin died in West Chester from a stroke in his sleep; his wife, who was confined to a state mental hospital, died two weeks later, never learning of her husband’s death.

BEARDEN, ROMARE, and Harry Henderson. A History of African American Artists (1993).

Stein, Judith E. I Tell My Heart: The Art of Horace Pippin (1993).

—J. SUSAN ISAACS

PLEASANT, MARY ELLEN

PLEASANT, MARY ELLEN(1812?–1904), legendary woman of influence and political power in Gold Rush and Gilded Age San Francisco, was born, according to some sources, a slave in Georgia; other sources claim that her mother was a Louisiana slave and her father Asian or Native American. Many sources agree that she lived in Boston, as a free woman, the wife of James W. Smith, a Cuban abolitionist. When he died in 1844 he left her his estate, valued at approximately forty-five thousand dollars.

Mary Ellen next married a man whose last name was Pleasant or Pleasants and made her way to California, arriving in San Francisco in 1849. Her husband’s whereabouts after this time have never been made clear. She started life in San Francisco as a cook for wealthy clients, then opened her own boardinghouse. Her guests were said to be men of influence, and it was rumored that her places were also houses of prostitution.

Many sources state that Pleasant was a very active abolitionist, helping escaped slaves find jobs around the city. When she heard of John Brown’s desire to incite slave rebellions, she supposedly met with him in Canada in 1858, handing him thirty thousand dollars of her own money to further his cause. When Brown’s attempt to seize the arsenal at Harpers Ferry failed, authorities began searching for her, though she was able to disguise herself and find her way back to San Francisco under the name of Mrs. Ellen Smith. When Brown was captured, he supposedly had a note in his pocket that said, “The ax is laid at the root of the tree. When the first blow is struck, there will be more money to help.” It was signed with the initials W. E. P., though some conjecture that Pleasant signed the note and deliberately made her “M” look like a “W.”

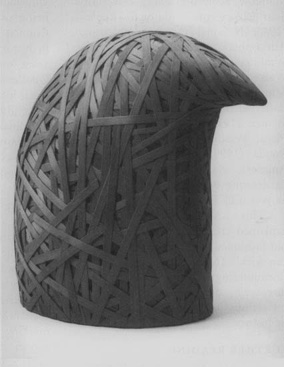

Mary Ellen Pleasant. William Loren Katz Collection

Back in San Francisco, Pleasant fought racism by suing a streetcar company for not allowing her to ride. She sued twice, once in 1866 and again in 1868. She finally received damages in the latter suit, but she had to have a white man witness the streetcar conductor refusing her a seat in order to win her case. During the 1860s she supposedly found wives for wealthy men as well as homes for their illegitimate children. She placed former slaves as servants in homes all over the city, creating a communication network for the receipt of gossip and information, in the much the same way that her contemporary, the voodoo priestess MARIE LAVEAUX, built a power base in New Orleans.

Pleasant is best known for being the housekeeper of banker Thomas Bell, who married Teresa Percy, one of Pleasant’s protégés. By this time Pleasant was known to white San Franciscans as “Mammy,” and was said to have some sort of power over the Bells. It was even rumored that voodoo rituals were held in the Bell home on Octavia Street, and the mansion soon became known as the “House of Mystery.” Pleasant was considered a woman of mystery herself, and was described in newspaper articles and in the memoirs of native San Franciscans as “strange” “mesmeric” and “picturesque.”

In 1883 and 1884 Pleasant’s name was again in local newspapers because of her involvement in the court case of Sarah Althea Hill v. William Sharon. Sharon, a millionaire, former Nevada senator, and owner of the opulent Palace Hotel, was being sued by Hill for support under the terms of a secret marriage contract. The contract later proved to be a forgery and supposedly had been arranged by Pleasant. Pleasant’s access to and seeming power over the rich men of San Francisco made this a believable story to most of the city’s citizens. During the trial, Hill claimed to be “controlled” by Pleasant, and Pleasant’s appearance in court always caused a stir, as recorded on 6 May 1884 in the San Francisco Call: “Mammy Pleasant, as the plaintiff calls her colored companion, shows herself in court only as a bird of passage, so to say. She bustles in, converses pleasantly with the young men attached to the defendant’s counsel . . . and like a wind from the south astray in northern climes departs and leaves but chill behind.”

One of the few established facts in the life of Mary Ellen Pleasant is that Thomas Bell died in 1892, after a fall from the second story landing of the House of Mystery. Many thought Pleasant had murdered him; if so, and if the murder was for gain, it was fruitless, for when his wife inherited Bell’s money, she eventually forced Pleasant out of the house and into a small flat in the city’s African American district. Living in poverty, Pleasant was taken in by the Sherwood family, to whom she had rendered assistance at one time. When Pleasant died in San Francisco, she was placed in the Sherwood family plot in the Tucolay Cemetery in Napa, California. At her request, her gravestone contained the words: “She Was a Friend of John Brown.” After her death the San Francisco Call (12 Jan. 1904) reported a mysterious matter that pertained to her association with John Brown: “Among her effects are letters and documents bearing upon the historical event in which she played an important part. The Brown family raided her flat when Mrs. Sherwood took her home. After her death, the Sherwoods found Mrs. Pleasant’s trunks in her Webster Street flat to be all but empty.”

Pleasant seems to have wielded power over influential people, yet because she was African American and female, her activities did not reflect her racial and social status, which possibly led to the rumors that she engaged in voodoo and even murder. She moved freely through the highest levels of society, yet she dressed always like a servant. She left nothing in writing, and surviving diaries and newspaper articles paint her as a mysterious and sinister figure. At the same time, some recalled Pleasant as “generous,” claiming that she used her own money to aid African American railroad strikers and assisted with other black causes. A few San Franciscans who were children during Pleasant’s lifetime remembered her as a churchgoing “lovely old lady” and said that they never believed the voodoo stories.

Historians have rediscovered Mary Ellen Pleasant, and perhaps new materials will come to light to reveal more about this woman whose presence haunts the annals of nineteenth-century San Francisco.

Few primary materials on Mary Ellen Pleasant have survived or been discovered. A photograph, generally agreed to be that of Pleasant, is in the Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture of the New York Public Library. Pleasant’s biographer, Helen Holdredge, has placed notes and transcripts of interviews in the San Francisco Public Library.

Holdredge, Helen. Mammy Pleasant (1953).

Hudson, Lynn. The Making of “Mammy” Pleasant: A Black Entrepreneur in Nineteenth Century San Francisco (2003).

Wheeler, B. Gordon. Black California: The History of African Americans in the Golden State (1993).

—LYNN DOWNEY

PLESSY, HOMER ADOLPH

PLESSY, HOMER ADOLPH(1858?–1925), plaintiff in the 1896 landmark U.S. Supreme Court case Plessy v. Ferguson, was born probably in New Orleans. Beyond the case, very little is known about Plessy. He was said to be thirty-four years old at the time of his arrest in 1892, which places his birth around 1858; yet his tombstone lists his age as sixty-three years old when he died in 1925, which places his birth around 1862. Described as a “Creole of Color,” Plessy was white in appearance but known to have had a black great-grandmother. He worked as a carpenter.

On 7 June 1892, on a sixty-mile train trip from New Orleans to Covington, Louisiana, Plessy, defined as black by Louisiana law because of his mixed-race heritage, sat in the coach designated for white passengers. Railroad officials were aware that he had boarded the train in order to test the 1890 Louisiana statute requiring all railroad companies to provide and enforce separate-but-equal accommodations for black and white passengers. Thus, although Plessy had no discernible black features, he was asked to move to the car reserved for black passengers. When Plessy refused, he was arrested.

Through his attorneys, Albion Tourgée and S. F. Phillips, and with the aid of the Citizens Committee to Test the Constitutionality of the Separate Car Law (Comité des Citoyens), an organization of blacks in New Orleans, Plessy filed a suit questioning the constitutionality of the state statute. After the suit was overruled by the lower court, Plessy petitioned the Louisiana Supreme Court for writs of prohibition and certiorari against the lower court judge, John Ferguson, prohibiting him from holding Plessy’s trial. The request was denied, but the court allowed his case to go before the U.S. Supreme Court on a writ of error.

The argument in Plessy v. Ferguson revolved around the constitutionality of the Louisiana statute and whether it violated the Fourteenth Amendment’s equal protection clause. The question of equal accommodation was not discussed. As for race, Plessy did not admit to any court that he had African blood. Tourgée argued that because Plessy had no distinguishable black features he was entitled to all the privileges and immunities of white people. And, further, that the Louisiana law gave railroad officials the power to determine racial identity arbitrarily and assign coaches accordingly.

The Supreme Court rejected Tourgée’s arguments. With Justice Henry Billings Brown delivering the majority opinion, the Court ruled against Plessy. A compelling aspect of the decision was the opinion of Justice John Marshall Harlan, the lone dissenter. Whereas Brown, employing nineteenth-century Darwinian reasoning, argued that blacks perceived “a badge of inferiority” because of the law enforcing segregation, Harlan argued that “our constitution is color blind, and neither knows nor tolerates classes among citizens. In respect to civil rights, all citizens are equal before the law.” However, the Court established the doctrine of separate but equal, which would not be revisited until well into the twentieth century when it was unanimously overturned in another landmark case, Brown v. Board of Education (1954).

Homer Plessy’s trial was held on 11 January 1897, four and a half years after his arrest. He pleaded guilty and paid a twenty-five-dollar fine. Plessy died in New Orleans.

HIGGINBOTHAM, A. LEON. Shades of Freedom (1996), Chapter 9.

Lofgren, Charles A. The Plessy Case: A Legal-Historical Interpretation (1987).

Thomas, Brook, ed. Plessy v. Ferguson: A Brief History with Documents (1998).

Woodward, C. Vann. “The Case of the Louisiana Traveler” in Quarrels That Have Shaped the Constitution, ed. John A. Garraty (1964).

—MAMIE E. LOCKE

POINDEXTER, HILDRUS AUGUSTUS

POINDEXTER, HILDRUS AUGUSTUS(10 May 1901–20 Apr. 1987), physician, microbiologist, and public health specialist, was born on a farm near Memphis, Tennessee, the son of Fred Poindexter and Luvenia Gilberta Clarke, tenant farmers. After attending the normal (teacher training) department of Swift Memorial College, a Presbyterian school for blacks in Rogersville, Tennessee (1916–1920), he entered Lincoln University (Pa.) and graduated with an AB cum laude in 1924. Also in 1924 he married Ruth Viola Grier, with whom he would have one child, a daughter. He attended Dartmouth Medical School for two years before earning an MD at Harvard University in 1929, an AM in Bacteriology at Columbia University in 1930, a PhD in Bacteriology and Parasitology at Columbia in 1932, and an MPH from Columbia in 1937.

Poindexter had hoped to proceed directly into public health fieldwork in 1929, following his graduation from Harvard, but his application for a laboratory post in a U.S. government laboratory in Manila was declined because of his race. Instead, he served an internship at the John A. Andrew Hospital at Tuskegee Institute in Alabama, one of the few facilities open to African Americans seeking postgraduate training. In addition to his regular duties at the hospital, he began an epidemiological survey and implemented a health education program in Union Springs, Bullock County, a poor, predominantly black settlement. He left after ten weeks to accept a two-year fellowship offered by the General Education Board. This Rockefeller-funded fellowship, for graduate study at Columbia University, was part of a larger plan of the administration at Howard University to provide advanced training for several promising young black medical scientists, who, after earning their PhDs, would assume faculty positions at the medical school and help to upgrade the curriculum and research program.

Poindexter served at Howard University as assistant professor of bacteriology, preventive medicine, and public health (1931–1934), associate professor (1934–1936), and professor and department head (1936–1943). He also held posts at Freedmen’s Hospital as bacteriologist, immunologist, and assistant director of the allergy clinic. Despite the pressure of administrative, teaching, and clinical duties, he resumed the research he had begun as an intern in Alabama. For three years (1934–1937), he returned periodically to the South and worked, with Rockefeller support, as an epidemiologist for the states of Alabama and Mississippi. The information he had gathered earlier, along with new data, provided him with an opportunity to draw some general conclusions about the state of African American health in the rural South. Poindexter identified malnutrition, syphilis, insect-borne diseases such as malaria, and hookworm infestation as the four most important health problems confronting rural southern blacks. He distributed blame for these conditions almost equally among blacks and whites. Blacks, he felt, were overly swayed by an “illiterate religious leadership” and a “mania for cotton and corn crops,” while he believed whites tolerated an “apathetic county health service” and an “inequitable system of education.” His solution called for joint “practical education” efforts by state boards of health, black churches, and the schools.

In 1943 Poindexter was appointed a tropical medicine specialist in the U.S. Army, serving in the racially segregated hospital at Fort Huachuca, Arizona, and later as a malariologist, parasitologist, and epidemiologist (with rank of major) at Guadalcanal and elsewhere in the Pacific. In recognition of his military service, he was awarded the Bronze Star and four combat stars. He retired from the army (with the rank of lieutenant-colonel) effective 26 March 1947.

Poindexter’s role during World War II laid the groundwork for nearly two decades of federal public health service. On 13 January 1947 he received a commission as senior surgeon with the United States Public Health Service (USPHS). His first post was with the USPHS Mission in Liberia (MIL) as chief of laboratory and medical research in West Africa. This post he held until his appointment a year later as medical director and chief of mission for MIL and as medical and health attaché to the American embassy in Monrovia. In 1953 he was transferred to Indochina and served (1955–1956) as chief of health and sanitation, U.S. Operation Missions (OM) in Vietnam, Cambodia, and Laos. Other OM appointments followed in Surinam (1956–1958), Iraq (1958–1959), Libya (1959–1961), and Sierra Leone (1962–1964). While in Iraq he also served as professor of preventive medicine at the Royal Baghdad Medical College. Poindexter was a consulting malariologist in Jamaica (1961–1962) and undertook several assignments under USPHS’s international section during the early 1960s. He retired from USPHS in 1965.

Poindexter’s work in Liberia included the training of indigenous health care personnel, conducting epidemiological surveys and other research projects, antibiotics assay and evaluation, implementing preventive programs, initiating immunization and epidemic control, improving nutrition, and orchestrating demonstration projects in health education. MIL was one of the programs that had emerged from a 1943 agreement between the U.S. and Liberian presidents for increased U.S. assistance in health, economics, agriculture, and other fields. Poindexter’s predecessor, John B. West, had begun the program in 1946. While their work focused on technical assistance, the doctors were interested in larger cultural factors as well. Poindexter, for example, wrote about the need not just to correct “social and economic handicaps” but also to develop—for the mutual benefit of Africans and non-Africans alike—“a clearer picture of the people as they live and breathe.” His approach to subsequent assignments in Indochina, South America, the Caribbean, and elsewhere in Africa was similar.

Poindexter was a certified specialist of both the American Board of Preventive Medicine and Public Health and the American Board of Microbiology. In 1949 he became the first black member of the American Society of Tropical Medicine and subsequently served as a vice president of the Washington, D.C., chapter and as a trustee of the national body. He had been denied admission to the society in 1934 because of his race.

Following his retirement from USPHS, Poindexter returned briefly to Howard University as professor of community health practice. He remained active in teaching and research for the next fifteen years. He trained Peace Corps workers; served as a special consultant to the U.S. Department of State and the Agency for International Development, including a six-month tour of duty in 1965 with the relief and rehabilitation unit in Nigeria; and published several articles on public health issues, notably on malaria, sexually transmitted diseases, and medical problems of the elderly. He died at his home in Clinton, Maryland.

Correspondence, manuscripts, and other papers of Hildrus Augustus Poindexter are preserved in the Moorland-Spingarn Research Center, Howard University.

Poindexter, Hildrus Augustus. My World of Reality (1973).

Cobb, W. Montague. “Hildrus Augustus Poindexter, M.D., M.P.H., Ph.D., D.Sc., 1901–.” Journal of the National Medical Association 65 (May 1973): 243–47.

Miller, Carroll L. “Hildrus Augustus Poindexter (1901—). “Howard University Profiles, Feb. 1980: 1–15.

Obituary: Washington Post, 25 Apr. 1987.

—KENNETH R. MANNING

POITIER, SIDNEY

POITIER, SIDNEY(20 Feb. 1927–), actor, director, and producer, was born the son of Reginald Poitier, a tomato farmer, and Evelyn in Miami, Florida, where his parents were visiting. The family of ten lived on Cat Island in the Bahamas, but when the tomato business no longer proved lucrative, they moved to Nassau, where Sidney attended Western Senior High School and Governor’s High School. But even in the more prosperous urban center of Nassau, the Poitier family remained impoverished, and Sidney was forced to leave school during the Depression in order to help his father.

Despite their financial difficulties, Reginald instilled a sense of pride in his family, and Sidney learned never to indulge in self-pity but rather to make the best out of every situation. With the urban landscape arrived the difficulties of adolescence and the influence of wayward youth, and when Sidney fell into some trouble his parents sent him to Miami to live with relatives. Working as a delivery boy, Sidney encountered racism in the form of police hostility and the Ku Klux Klan. Such experiences were jarring for a young teenager accustomed to the all-black environment of his native Bahamas, and, stifled by the oppressive racism, Sidney headed for New York. He quickly found a job as a dishwasher and struggled to make a reasonable living. In 1943 he joined the army, and after serving two years in a medical unit during World War II, he returned to Harlem in 1945.

While scouring local newspapers in search of a job, Poitier stumbled upon an advertisement for “actors wanted” and decided to audition at the American Negro Theater. But his first audition would end rather dismally; he was interrupted and told to stop wasting the director’s time. That director, FREDERICK DOUGLASS O’NEAL, was not impressed with Poitier’s halting, accented English as he struggled through the dialogue. Poitier was undaunted and left the theater even more determined to act. During the next six months he used the radio to help him learn American English, and by imitating the voices he heard, he managed to strip himself of his Bahamian accent. In addition, he devoured any available written text, knowing that reading extensively would help him accomplish his goal. Initially driven simply by a desire to show O’Neal that he could indeed act, Poitier soon began to take the theater seriously. His efforts paid off, and at his next audition O’Neal agreed to give him acting lessons in exchange for janitorial work.

Poitier was given his first break when he was designated to replace a then little known actor named HARRY BELAFONTE for a major run-through at which an important casting director would be present. The director was impressed by his performance and offered him a role in the Broadway production of Lysistrata. Unfortunately, what should have been a promising debut performance was tarnished by an attack of nervousness that caused Poitier to flub most of his lines. But the critics were gentle, noting particularly Poitier’s gift for comedy. Following this production, Poitier appeared in Anna Lucasta (1947) and in You Can’t Take It with You and On Striver’s Row. In 1959 he originated the role of Walter Lee Younger in Lloyd Richards’s production of LORRAINE HANSBERRY’S A Raisin in the Sun. Upon auditioning for an upcoming film, No Way Out (1949), he was cast in the leading role as a doctor struggling to do his job well during the tense racial climate after World War II. This “racial problem” film—in which the star struggles to negotiate his black identity under difficult circumstances caused by racism—was the first of many during his career. Also in 1950 Poitier married the dancer Juanita Hardy, with whom he would have four children before the couple’s divorce in 1965.

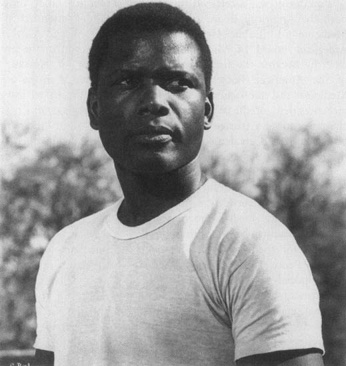

In 1964 Sidney Poitier became the first African American to win an Academy Award for best actor for his performance in Lilies of the Field. Corbis

The success of No Way Out led to roles in Cry, the Beloved Country (1952) and The Blackboard Jungle (1955). With these films under his belt, Poitier gained access to more of what Hollywood had to offer, and he worked consistently during the 1950s and 1960s, appearing in Edge of the City (1957), Something of Value (1957), The Defiant Ones (1958), and Porgy and Bess (1959). In each case he portrayed polite, well-spoken African Americans, defying the stereotype of the singing, dancing, and joking black man that had prevailed in American film. With his performance in The Defiant Ones he became the first African American to be nominated for an Academy Award as Best Actor.

With his reputation established as an African American force to be reckoned with, Poitier delivered moving performances in All the Young Men (1960) and again as Younger in the film version of A Raisin in the Sun (1961). These two roles led up to his part in Lilies of the Field (1963), the story of a construction worker who comes to the aid of a group of German-speaking nuns. With this performance Poitier became the first African American to win the Academy Award for Best Actor in 1964. Thereafter Poiter was even more sought after as an actor, and in 1967 alone he appeared in three films for which he earned enormous success. He starred in To Sir with Love (1967) and In the Heat of the Night (1967), and then, in the role that he may be best known for, he was cast as a successful young doctor who is engaged to a young white woman and who meets her parents for the first time in Guess Who’s Coming to Dinner? (1967).

With each role, Poitier was highly conscious of representing his family and his race, and he accepted only those roles that he believed portrayed African Americans in a positive light. For all of his efforts, he still received ample criticism from other black actors who believed Poitier was doing a disservice to his race by embodying the “good Negro” stereotype—the noble and magnanimous black man who never steps out of the mainstream perception of what a “proper” black man ought to be and do.

During the 1970s, however, Poitier starred in They Call Me Mr. Tibbs (1970) and Buck and the Preacher (1972), both roles that symbolized a departure from the distinguished characters he had previously portrayed. The latter was also his directorial debut. Two years later he collaborated with BILL COSBY in Uptown Saturday Night (1974). In 1974 he also married the actress Joanna Shimkus; they have two children. He also worked with Paul Newman and Barbra Streisand, among others, to form First Artists, an independent production company. He subsequently filmed two sequels to Uptown Saturday Night: Let’s Do It Again (1975) and A Piece of the Action (1977).

In 1980 Poitier published an autobiography, This Life, and gave up acting in favor of directing such movies as Stir Crazy (1980), Hanky Panky (1982), and Fast Forward (1985). He collaborated with Bill Cosby once again in 1990 and directed Ghost Dad. When Poitier returned to acting, it was to make a few television films, such as Separate but Equal (1991), Children of the Dust (1995), To Sir with Love II (1996), and Mandela and de Klerk (1997); he ended the decade in the title role of the television film The Simple Life of Noah Dearborn (1999).

Poitier began the twenty-first century with the publication of a second autobiography, The Measure of a Man: A Spiritual Autobiography (2000). He also served briefly as the Bahamian ambassador to Japan. Poitier lives in Beverly Hills, California, with his family. He has received numerous honors and awards, including the Lifetime Achievement Award from the American Film Institute and a knighthood from England’s Queen Elizabeth. At the seventy-fourth Academy Awards in 2001, Poitier was presented with a prestigious Honorary Oscar. During the presentation the academy president Frank Pierson declared, “When the academy honors Sidney Poitier, it honors itself even more,” thus indicating Poitier’s place as a Hollywood icon.

Poitier, Sidney. The Measure of a Man: A Spiritual Autobiography (2000).

_______. This Life (1980).

Ewers, Carolyn H. Sidney Poitier: The Long Journey, a Biography (1969).

Keyser, Lester J., and André H. Ruszkowski. The Cinema of Sidney Poitier: The Black Man’s Changing Role on the American Screen (1980).

—RÉGINE MICHELLE JEAN-CHARLES

POOLE, ROBERT.

POOLE, ROBERT.see Muhammad, Elijah.

PORTER, JAMES AMOS

PORTER, JAMES AMOS(22 Dec. 1905–28 Feb. 1970), painter, art historian, and writer, was born in Baltimore, Maryland, the son of John Porter, a Methodist minister, and Lydia Peck, a schoolteacher. The youngest of seven siblings, he attended the public schools in Baltimore and Washington, D.C., and graduated cum laude from Howard University in 1927 with a bachelor of science in Art. That same year Howard appointed him instructor in art in the School of Applied Sciences. In December 1929 he married Dorothy Louise Burnett of Montclair, New Jersey; they had one daughter.

In 1929 Porter studied at the Art Students League of New York under Dimitri Romanovsky and George Bridgeman. In August 1935 he received the certificat de présence from the Institut d’Art et Archéologie, University of Paris, and in 1937 he received a master of arts in Art History from New York University, Fine Arts Graduate Center.

Porter first exhibited with the Harmon Foundation in 1928 and in 1933 was awarded the ARTHUR SCHOMBURG Portrait Prize during the Harmon Foundation Exhibition of Negro Artists for his painting Woman Holding a Jug (Fisk University, Carl Van Vechten Collection). Other early exhibitions in which he participated include the Thirty-second Annual Exhibition of the Washington Water Color Club (Gallery Room, National Gallery of Art, Smithsonian Institution, Washington, D.C., 1928), Exhibition of Paintings and Sculpture of American Negro Artists at the National Gallery of Art (Smithsonian Institution, 1929), Exhibition of Paintings and Drawings by James A. Porter and Block Prints by James Lesesne Wells (Young Women’s Christian Association, Montclair, N.J., 1930), and Exhibition of Paintings by American Negro Artists at the United States National Museum (Smithsonian Institution, 1930); his first one-man show was Exhibition of Paintings and Drawings by James A. Porter (Howard University Gallery of Art, 1930).

Porter began writing about art in the late 1920s. One of his earliest articles, “Versatile Interests of the Early Negro Artist,” appeared in Art in America in 1931. One of his most important and still-discussed articles, “Four Problems in the History of Negro Art,” published in the Journal of Negro History in 1942, mentions numerous artists and analyzes the following four problems: documenting and locating the earliest art by blacks—or the reality of handicrafts and fine arts by Negroes before 1820; discovering when racial subject matter takes vital hold on the black artist—or the Negro artist’s relation to the mainstream of American society; investigating the decline of productivity among black artists between 1870 and 1890 (a process that coincided with the end of an era, especially of neoclassicism and portraiture), concentrating on the period of Reconstruction; and determining the role of visual artists in the New Negro Movement of 1900–1920, the period of self-expression for the Negro.

Porter’s classic book, Modern Negro Art (1943), has proved to be one of the most informative sources on the productivity of the African American artist in the United States since the eighteenth century. Its placement of African American artists in the context of modern art history

was both novel and profound. For some, Modern Negro Art was considered presumptuous and certainly premature. But Porter’s bold and perceptive scholarship helped those who subsequently focused their attention on African American expression in the visual arts to see the wealth of work that had been produced in the United States for over two centuries” (James A. Porter Inaugural Colloquium on African American Art, brochure, 31 Mar. 1990, Howard Univ.).

First reprinted in 1963 for use as a standard reference work on black art in America, it was reprinted again in 1992 and is considered by many to be the fundamental book on black art history. As Lowery S. Sims of the Metropolitan Museum of Art has noted in the 1992 edition, Modern Negro Art “is still an indispensable reference work fifty years after its initial publication”; and, in the view of art historian Richard J. Powell, it “continues to provide today’s scholars with early source information, core bibliographic material, and other essential research tools for African American art history” (Modern Negro Art [1992]).

Porter also wrote about many artists, including HENRY OSSAWA TANNER, ROBERT S. DUNCANSON, Malvin Gray Johnson, and Laura Wheeler Waring. His other writings include monographs, book reviews, introductions to books, including Charles White’s Dignity of Images and LOÏS MAILOU JONES’S Peintures, 1937–1951, introductions and forewords to exhibition catalogs, and newspaper and periodical articles.

In 1953 Porter was appointed head of the Department of Art and director of the Gallery of Art at Howard University. This dual position enabled him to organize exhibitions featuring artists of many races from many countries who previously had not been recognized. He is credited with enlarging the permanent art collection of Howard University and strengthening the art department’s collection of works by black artists as well as its art curriculum. Porter’s leadership led the Kress Foundation to include Howard among the roughly two dozen American universities selected in 1961 to receive the Kress Study Collection of Renaissance paintings and sculpture as a stimulus to the study of art history.

In 1955 Porter received the Achievement in Art Award from the Pyramid Club of Philadelphia and also was appointed a fellow of the Belgium-American Art Seminar studying Flemish and Dutch art of the sixteenth to eighteenth centuries. In 1961 he was a delegate at the UNESCO Conference on Africa, held in Boston, and he served as a member of the Arts Council of Washington, D.C. (1961–1963), and as a member of the conference Symposium on Art and Public Education (1962). In August 1962 he was a delegate-member of the International Congress on African Art and Culture, sponsored by the Rhodes National Gallery, in Salisbury, Southern Rhodesia.